Abstract

Background:

The effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections for knee osteoarthritis and the effects of leukocyte-poor PRP (LP-PRP) versus leukocyte-rich PRP (LR-PRP) are still controversial.

Purpose:

To assess the effectiveness of different PRP injections through a direct and indirect meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Study Design:

Systematic review; Level of evidence, 1.

Methods:

A systematic literature search of electronic databases (PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE) was performed to locate randomized controlled trials published through March 2019 that compared PRP with control treatment. A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted to synthesize the evidence, and meta-regression analyses were conducted to determine the influence of trial characteristics. An indirect comparison was performed to assess the effects of LP-PRP and LR-PRP compared with hyaluronic acid (HA).

Results:

A total of 21 trials were included. A clinically important benefit for pain relief was seen for intra-articular PRP compared with intra-articular saline (standardized mean difference [SMD] = –1.38 [95% CI, –2.07 to –0.70]; P < .0001; I 2 = 37%) and corticosteroid solution injection (SMD = –2.47 [95% CI, –3.34 to –1.61]; P < .00001; I 2 = 47%). As a result of heterogeneity (I 2 = 89%), there was no conclusive effect compared with HA, even though the pooling effect provided clinically relevant pain relief (SMD = –0.59 [95% CI, –0.97 to –0.21]; P = .003). Indirect meta-analysis showed that there was no significant difference between LR-PRP and LP-PRP.

Conclusion:

PRP injections are beneficial for pain relief and functional improvement in knee osteoarthritis. Larger, randomized high-quality studies are needed to compare the effects of LP-PRP and LR-PRP.

Keywords: knee osteoarthritis, platelet-rich plasma, meta-analysis, randomized controlled clinical trials, treatment

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most prevalent chronic joint diseases, a leading cause of chronic pain and disability30 that affects an estimated 25% of adults aged 55 years or older.33 Despite numerous treatment approaches, treatments to modify the course of the disease have not reached a threshold of efficacy to gain regulatory approval. Furthermore, hyaluronic acid (HA), the most commonly used drug in the treatment of OA, was not recommended in the 2013 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) guidelines because of a lack of significant beneficial evidence.18 Clinical interest is increasing in the testing of new biological products to improve the efficacy of intra-articular injection treatment.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is an autologous whole-blood extract containing high concentrations of platelets and growth factor, using injections of a patient’s own platelets to promote and accelerate the recovery of injured ligaments, muscles, tendons, and joints.15 Because PRP uses a patient’s own immune system to improve OA, this treatment has few adverse effects and requires only a short hospital stay. Because of the potential of PRP to reduce inflammation and facilitate tissue repair, PRP and various PRP-derived products are increasingly described as regenerative.2 Although many clinical trials have been conducted, conclusions about the efficacy of these products are inconsistent. One reason for this inconsistency might be the use of leukocyte-poor PRP (LP-PRP) versus leukocyte-rich PRP (LR-PRP), which have different functions according to the concentration of white cells.9 Among the 13 meta-analyses that have been performed to date regarding the efficacy of PRP in OA,§ 11 studies drew positive conclusions,∥ but 2 recent studies contradicted the evidence of efficacy.46,50 Meanwhile, this field is gaining widespread attention, and several more comparative studies have been published recently.¶ Furthermore, most previous meta-analyses did not compare the therapeutic effects of LP-PRP versus LR-PRP.

The purpose of our study was to provide an updated meta-analysis evaluating the different preparations of PRP for the treatment of OA. In addition, we performed an indirect meta-analysis to assess the effectiveness of each PRP category in the treatment of knee OA. We hypothesized that intra-articular PRP would provide better results compared with other intra-articular options and that a significant difference in efficacy would be found when comparing LR-PRP versus LP-PRP for the treatment of OA.

Methods

This meta-analysis was performed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and is presented based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.16,29 The protocol for this meta-analysis is available in PROSPERO (CRD42019122002).

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We performed an online systematic search for eligible trials using the electronic databases of PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE for studies published though March 2019. The detailed search strategy for each database is presented in Appendix Table A1. After the electronic search, we manually extracted relevant articles from the reference lists of included studies or previous systematic reviews.

Eligibility Criteria

To be included in the study, the trials had to fulfill the following 3 criteria: (1) randomized controlled trials comparing various preparations of intra-articular PRP (ie, autologous blood concentration, autologous conditioned plasma, or plasma rich in growth factors) with HA, corticosteroid, or saline in patients with knee OA; (2) minimum follow-up of 6 months; and (3) studies written in English. Studies were excluded if they included duplicate data.

Outcomes and Data Extraction

Data were extracted by 2 reviewers (L.-y.N. and K.Z.), and disagreements were resolved through discussion before the analyses were performed. Extracted data included characteristics of the study design to assess risk of bias, baseline demographic characteristics, PRP preparation method, control group intervention, and follow-up time point. The primary outcome was mean change from baseline to the endpoint in knee pain and physical function. When a study reported more than 1 pain-outcome measure, we gave preference to the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Pain subscale.27 The secondary outcome was adverse events or complications.

Quality and Risk-of-Bias Assessments

The quality of the included studies was independently evaluated by the same 2 reviewers using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias,16 which consists of 7 areas: randomization sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. Each item was graded as low, high, or unclear risk. The included trials were graded as low, high, or moderate quality based on the criteria as described by Zhao et al.49 Disagreements were discussed and resolved through consensus.

Data and Statistical Analysis

Continuous outcomes were used for statistical efficacy analysis using the Hedge standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs. Meta-analyses used the random-effects model as the variation of the study characteristics. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistic. Meta-regression analyses were performed to assess the influence of trial characteristics (PRP category, spinning approach, activator, number of injections, randomization confirmed, allocation concealment confirmed, sufficient blinding, control group, outcome measure instrument, and follow-up duration) on the treatment effects.

We conducted sensitivity analyses by restricting the analyses to high-quality randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs), and we also evaluated whether the pooled effects met the threshold for minimal clinically important differences, which have been estimated to be SMDs of 0.39 for WOMAC Pain and 0.37 for WOMAC Function.27 We also performed a formal, indirect comparison using results from trials that compared LP-PRP or LR-PRP with HA intervention.

The significance of the pooled effects was evaluated by a Z test, and P < .05 was considered significant. Possible publication bias was sought by a funnel plot with Egger test. All direct statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager Version 5.3 (Nordic Cochrane Centre) or Stata Version 15.1 (StataCorp), and indirect comparisons were performed using ITC software (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health).

Results

Characteristics of the Included Studies

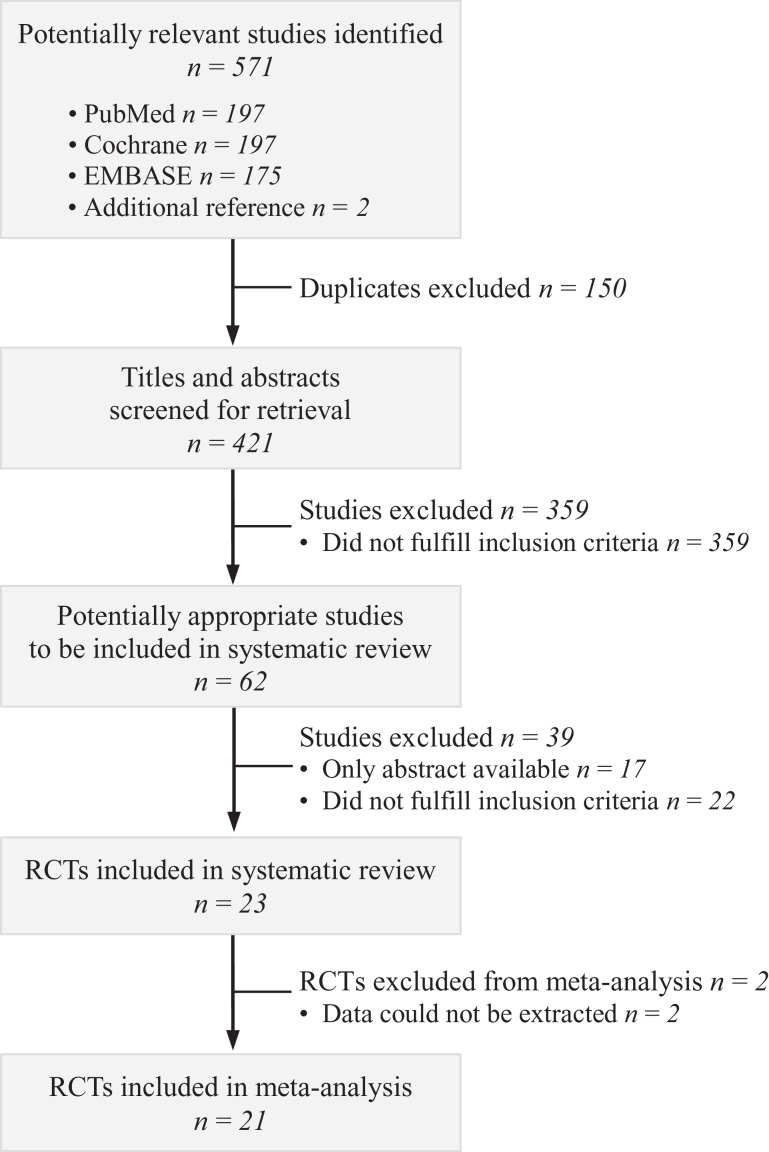

A total of 571 records were retrieved (569 records from database searches and 2 records from previously published meta-analyses38,44), and titles and abstracts of these records were screened for inclusion. The full texts of 62 records were read, of which 23 RCTs met eligibility criteria. Ultimately, 21 studies# were included in this meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study-selection process for the meta-analysis. RCT, randomized controlled trial.

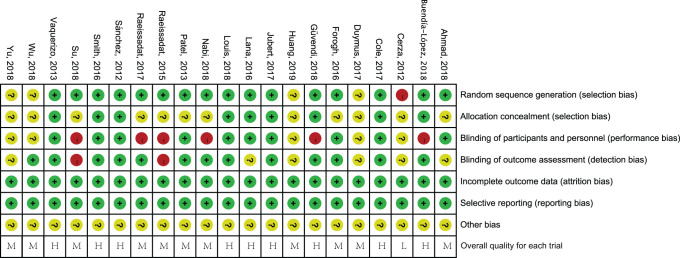

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. The RCT by Huang et al17 included 3 treatment groups, but this did not influence the outcome analysis. Appendix Figure A1 shows the assessment of the risk of bias. Due to ethical issues, 2 studies4,43 did not implement sufficient blinding; however, we believed that they should be regarded as high-quality research. Overall, the quality of the reported trials was acceptable, with 8 high-quality RCTs.4,20,24,26,38,40,43,44

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studiesa

| Sample Size | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Author (Year) | PRP | Control | PRP Type | Spinning Approach | Activator | No. of Injections | Control Group | Outcome Measure | Follow-up, mo |

| Cerza (2012)5 | 60 | 60 | LP | Single | NR | 4 | HA | WOMAC Pain subscale | 6 |

| Sánchez (2012)38 | 89 | 87 | LP | Single | CaCl2 | 3 | HA | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales, adverse events | 6 |

| Patel (2013)32 | 27 | 23 | LP | Single | CaCl2 | 1 | Saline | VAS | 6 |

| Vaquerizo (2013)44 | 48 | 48 | LP | Single | CaCl2 | 3 | HA | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales, adverse events | 6, 12 |

| Raeissadat (2015)34 | 77 | 62 | LR | Double | No | 3 | HA | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales | 12 |

| Forogh (2016)14 | 24 | 24 | LR | Double | CaCl2 | 1 | CS | VAS | 6 |

| Lana (2016)24 | 36 | 36 | LR | Double | Thrombin | 3 | HA | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales, VAS, adverse events | 6, 12 |

| Smith (2016)40 | 15 | 15 | LP | Single | NR | 3 | Saline | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales, adverse events | 6, 12 |

| Cole (2017)7 | 49 | 50 | LP | Single | NR | 3 | HA | WOMAC Pain subscale | 6,12 |

| Duymus (2017)11 | 33 | 34 | LR | Single | No | 2 | HA | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales, VAS | 6, 12 |

| Joshi Jubert (2017)20 | 35 | 30 | LP | Double | No | 1 | CS | VAS, adverse events | 6 |

| Raeissadat (2017)35 | 36 | 33 | LR | Double | CaCl2 | 2 | HA | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales, VAS | 6 |

| Ahmad (2018)1 | 45 | 44 | LR | Single | NR | 3 | HA | VAS, adverse events | 6 |

| Buendía-López (2018)4 | 33 | 32 | LP | Double | CaCl2 | 1 | HA | WOMAC Pain and Physical Function subscales, VAS, adverse events | 6, 12 |

| Uslu Guvendi (2018)43 | 19 | 17 | LR | Single | NR | 3 | CS | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales | 6 |

| Louis (2018)26 | 24 | 24 | LR | Double | CaCl2 | 1 | HA | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales, VAS, adverse events | 6 |

| Nabi (2018)31 | 33 | 34 | LR | Double | NR | 3 | CS | VAS, adverse events | 6 |

| Su (2018)42 | 25 | 30 | LR | Double | CaCl2 | 2 | HA | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales, VAS, adverse events | 6, 12, 18 |

| Wu (2018)45 | 20 | 20 | LR | Single | NR | 1 | Saline | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales, adverse events | 6 |

| Yu (2018)48 | 104 | 88 | LR | NR | NR | 1 | HA | WOMAC Pain and Function subscales, adverse events | 12 |

| Huang (2019)17 | 40 | 40 (HA); 40 (CS) | LP | Single | No | 3 | HA; CS | VAS, adverse events | 12 |

aCS, corticosteroid; HA, hyaluronic acid; LP, leukocyte poor; LR, leucocyte rich; NR, not reported; PRP, platelet-rich plasma; VAS, visual analog scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Efficacy of PRP

Initial meta-regression analyses for pain revealed that a significant cause of heterogeneity (P < .05) was the difference in the treatment of control groups (Appendix Table A2). For this reason, we performed subgroup analysis of 3 trials32,40,45 that reported reduction of pain for the treatment group (n = 87) relative to a saline control group (n = 81), with acceptable statistical heterogeneity (I 2 = 55%; P = .11). Pooling the data, we observed a significant effect of PRP treatment on pain (SMD = –1.63 [95% CI, –2.20 to –1.07]; P < .0001) (Figure 2A). When we omitted the data by Patel et al,32 who used a visual analog scale (VAS) score, the pooling effect provided clinically relevant improvements for WOMAC score with low heterogeneity (SMD = –1.38 [95% CI, –2.07 to –0.70]; P < .0001; I 2 = 37%) (Figure 2B). Subgroup analysis showed that PRP had a beneficial effect compared with HA or corticosteroid. However, the unexplainable statistical heterogeneity was excessive, and we were unable to identify a particular trial causing this excess variability (Figure 2A). Pooling data with such a high degree of heterogeneity of unknown cause is not advisable. When we omitted 5 trials that used a VAS score,1,7,17,20,31 the pooling effect demonstrated clinically relevant improvements for WOMAC score in the corticosteroid group, with acceptable heterogeneity (SMD = –2.47 [95% CI, –3.34 to –1.61]; P < .00001; I 2 = 47%). As a result of heterogeneity (I 2 = 89%) , there was no conclusive effect compared with HA, even though the pooling effect provided clinically relevant pain relief (SMD = –0.59 [95% CI, –0.97 to –0.21]; P = .003) (Figure 2B).

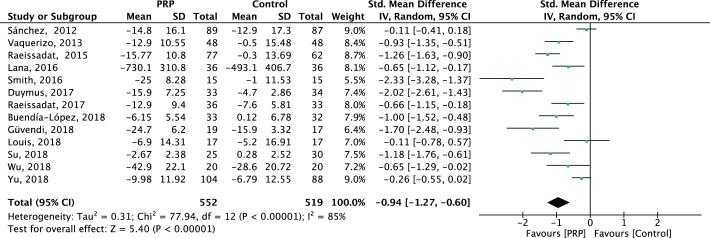

Figure 2.

Forest plots for effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) compared with different control groups for pain relief. (A) Overall effect. (B) Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain overall effect.

We could not identify initial meta-regression analyses for functional improvement that caused the observed significant heterogeneity (P < .05) (Appendix Table A2). When we combined all the trials,** the overall pooling effect provided clinically relevant functional improvements (SMD = –0.94 [95% CI, –1.27 to –0.60]; P < .00001) (Appendix Figure A2).

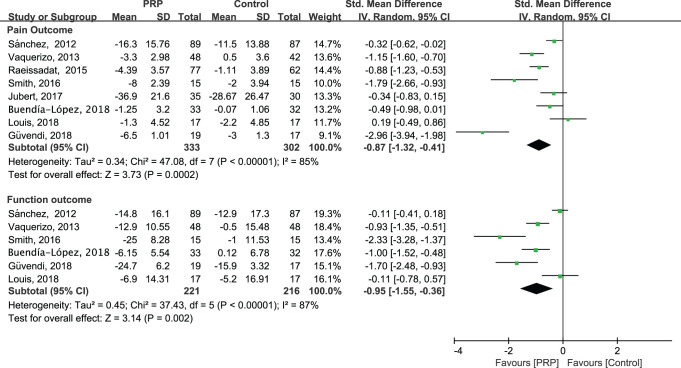

Sensitivity Analysis

Performing a sensitivity analysis that was restricted to high-quality RCTs, we were unable to identify a particular cause of the observed excess variability and heterogeneity in the statistical data (Figure 3). When the high-quality trials were pooled with all controls, we found a significant effect of PRP treatment for pain relief (SMD = –0.87 [95% CI, –1.32 to –0.41]; P = .0002; I 2 = 85%) and a clinically relevant functional improvement (SMD = –0.95 [95% CI, –1.55 to –0.36]; P = .002; I 2 = 87%). This did not meaningfully change the magnitude or direction of the overall effect.

Figure 3.

Results of sensitivity analysis for (A) pain relief and (B) functional improvement.

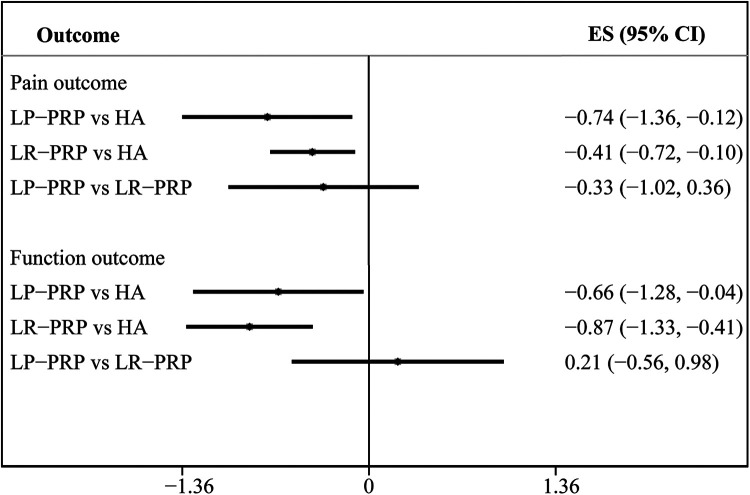

Indirect Comparison of the Effect of LP-PRP and LR-PRP

We chose the HA group for an indirect comparison analysis. For each outcome variable, a forest plot representing every possible treatment comparison was created. These results are summarized in Figure 4, showing no significant effect on pain relief (SMD = –0.33 [95% CI, –1.02 to 0.36]) and functional improvement (SMD = 0.21 [95% CI, –0.56 to 0.98]).

Figure 4.

Indirect comparison of the effect of LP-PRP versus LR-PRP. ES, effect size; HA, hyaluronic acid; LP, leukocyte-poor; LR, leukocyte-rich; PRP, platelet-rich plasma.

Adverse Events

We identified 13 RCTs that reported the incidence of adverse events.†† Of these, 6 studies observed zero adverse events in PRP groups.4,20,24,31,40,45 Although the other RCTs mentioned a few occurrences of adverse events, no significant difference was found between the PRP and control groups (Appendix Table A3).

Publication Bias

An Egger test12 was used to determine whether the effect sizes had been inflated by publication bias. The P values of the Egger test were .100 for WOMAC Pain and .016 for WOMAC Function (Appendix Table A4), indicating some inflation of effect sizes due to selective publication.

Discussion

Current evidence, which includes that from well-designed, double-blind trials, suggests that PRP may be an effective treatment for patients with OA of the knee. However, drawing general conclusions is complicated because of unexplained statistical heterogeneity. Statistically relevant clinical improvement was observed in trials that directly compared PRP with placebo or corticosteroid, with satisfactory evidence synthesis (acceptable heterogeneity). As such, it could be inferred that PRP was superior to saline and corticosteroid in relieving pain and improving self-reported function. LP-PRP and LR-PRP have similar effect profiles, although both induce more transient reactions than does HA.

Our results are not in accordance with the conclusions of 2 recent meta-analyses.46,50 When integrating all available high-quality randomized data on the effectiveness of PRP to treat knee OA, 1 meta-analysis46 inferred that PRP was not superior to HA (SMD = –0.09 [95% CI, –0.30 to 0.11]; I 2 = 0%). However, the authors of that meta-analysis excluded trials that were not blinded and thus considered only 2 trials to be scientifically high-quality studies.13,38 Another meta-analysis50 found that PRP injections reduced pain more effectively than HA injections at 6 and 12 months of follow-up when evaluated by the WOMAC Pain score, but pain reduction was not significant when evaluated by the VAS score. Because WOMAC is the most widely used and thoroughly validated instrument,27 the conclusion that the intra-articular injection of PRP was not significantly superior to HA in knee OA needs to be re-evaluated. Most meta-analyses did not take into account the statistical heterogeneity and concluded that PRP tends to be more effective than HA administration,6,8,21,22,25,37,39 but a systematic review regarding the efficacy of PRP treatment remained inconclusive.23 In our analysis, we also found that PRP was more effective than HA when considering the collective effect size of all the trials and even when restricted to high-quality RCTs, but with the existing high heterogeneity, more RCTs are needed to confirm this conclusion. Because intra-articular injections of corticosteroid are more efficacious in improving the symptoms of knee OA,3 the clinical importance of PRP is self-evident. Relevant policies and regulations should rapidly promote the clinical application of PRP and ensure standardization among PRP protocols.19

We performed an indirect comparison using ITC software to merge the pooled effect sizes of all trials comparing PRP with HA in terms of pain relief and functional improvement. The conclusion was in accordance with that of Riboh et al.36 LP-PRP and LR-PRP displayed similar profiles, although both induce more transient reactions than does HA. Which preparation, LP-PRP or LR-PRP, to use for treatment is an interesting point of debate. Two laboratory comparative studies directly investigated the effects of LP-PRP and LR-PRP, finding that LR-PRP caused a significantly greater acute inflammatory response and that LP-PRP could improve tendon healing, which is a preferable option for the clinical treatment of tendinopathy.10,47 Thus, future research should be focused on the direct comparison of LP-PRP and LR-PRP in the treatment of knee OA.

The AAOS guideline mentions, “We are unable to recommend for or against growth factor injections and/or platelet-rich plasma for patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee”18 as evidence from a single low-quality study or conflicting findings. Our meta-analysis found that PRP was superior in relieving pain and improving self-reported function when compared with saline and corticosteroid, with low heterogeneity. Our evidence may provide some decision support for the development of future guidelines.

The strength of this meta-analysis lies in its compliance with the PRISMA statement and registration of the protocol with PROSPERO, and we conducted an in-depth analysis to investigate the effect of PRP on treatment of OA. One potential limitation of our review is the unexplained heterogeneity in comparisons with HA (which may come from the heterogeneity of OA patients or varied PRP preparation protocols). Even though we used meta-regression to explore the source of heterogeneity, the results are limited. To some extent, this affected the accuracy of our results.

Conclusion

We found that the benefit of intra-articular PRP in the treatment of knee OA was clinically important when compared with intra-articular saline or corticosteroid solution injections. In addition, we found that LP-PRP and LR-PRP had similar effect profiles. Larger randomized studies of good quality are needed to test whether PRP injections should be a routine treatment for patients with knee OA and to compare the curative effects of LP-PRP and LR-PRP.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Lana Jose Fabio Santos Duarte for providing the original data for analysis.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Search Strategy for Each Databasea

| Search Strategy | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ||

| 1 | “Osteoarthritis”[Mesh] | 57,671 |

| 2 | osteoarthr*[Title/Abstract] OR “degenerative arthritis”[Title/Abstract] OR arthrosis[Title/Abstract] | 70,876 |

| 3 | #1 OR #2 | 88,094 |

| 4 | Platelet-Rich Plasma[MeSH] OR Blood Platelets[MeSH] OR Platelet-Derived Growth Factor[MeSH] OR Platelet Activation[MeSH] | 115,144 |

| 5 | “platelet rich plasma”[Title/Abstract] OR “platelet rich therapy”[Title/Abstract] OR “platelet rich therapies”[Title/Abstract] OR “platelet rich fibrin”[Title/Abstract] OR “platelet-derived growth factor”[Title/Abstract] OR “platelet plasma” [Title/Abstract] OR “platelet gel” [Title/Abstract] OR “platelet concentrate” [Title/Abstract] OR “buffy layer” [Title/Abstract] OR PRP[Title/Abstract] OR PRF[Title/Abstract] OR PDGF[Title/Abstract] | 46,433 |

| 6 | #4 OR #5 | 142,358 |

| 7 | (“Randomized Controlled Trial” [Publication Type] OR “Controlled Clinical Trial” [Publication Type] OR “Clinical Trials as Topic”[Mesh: NoExp] OR randomized[Title/Abstract] OR placebo [Title/Abstract] OR randomly[Title/Abstract] OR trial[Title]) NOT (“Animals”[Mesh] NOT (“Humans”[Mesh]) AND “Animals”[Mesh])) | 1,500,389 |

| 8 | #3 AND #6 AND #7 | 197 |

| Cochrane Library | ||

| 1 | MeSH descriptor: [Osteoarthritis] explode all trees | 6131 |

| 2 | (osteoarthr*): ti, ab, kw OR (“degenerative arthritis”): ti, ab, kw OR (arthrosis): ti, ab, kw | 12,178 |

| 3 | #1 OR #2 | 12,178 |

| 4 | MeSH descriptor: [Platelet-Rich Plasma] explode all trees | 346 |

| 5 | MeSH descriptor: [Blood Platelets] explode all trees | 1911 |

| 6 | MeSH descriptor: [Platelet-Derived Growth Factor] explode all trees | 139 |

| 7 | MeSH descriptor: [Platelet Activation] explode all trees | 2159 |

| 8 | (“platelet-rich plasma”): ti, ab, kw OR (“platelet rich therapy”): ti, ab, kw OR (“platelet rich therapies”): ti, ab, kw OR (“platelet rich fibrin”): ti, ab, kw OR (“platelet-derived growth factor”): ti, ab, kw OR (“platelet plasma”): ti, ab, kw OR (“platelet gel”): ti, ab, kw OR (“platelet concentrate”): ti, ab, kw OR (“buffy layer”): ti, ab, kw OR (PRP): ti, ab, kw OR (PRF): ti, ab, kw OR (PDGF): ti, ab, kw | 2786 |

| 9 | #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 | 5981 |

| 10 | #3 AND #9 | 197 |

| EMBASE | ||

| 1 | ‘osteoarthritis’/exp | 119,965 |

| 2 | ‘osteoarthr*’: ab, ti OR ‘degenerative arthritis’: ab, ti OR ‘arthrosis’: ab, ti | 97,646 |

| 3 | #1 OR #2 | 142,236 |

| 4 | ‘thrombocyte rich plasma’/exp OR ‘thrombocyte’/exp OR ‘platelet derived growth factor’/exp OR ‘thrombocyte activation’/exp | 156,755 |

| 5 | ‘platelet-rich plasma’: ab, ti OR ‘platelet rich therapy’: ab, ti OR ‘platelet rich therapies’: ab, ti OR ‘platelet rich fibrin’: ab, ti OR ‘platelet-derived growth factor’: ab, ti OR ‘platelet plasma’: ab, ti OR ‘platelet gel’: ab, ti OR ‘platelet concentrate’: ab, ti OR ‘buffy layer’: ab, ti OR ‘prp’: ab, ti OR ‘prf’: ab, ti OR ‘pdgf’: ab, ti | 59,927 |

| 6 | #4 OR #5 | 190,498 |

| 7 | ‘crossover procedure’: de OR ‘double-blind procedure’: de OR ‘randomized controlled trial’: de OR ‘single-blind procedure’: de OR random*: de, ab, ti OR factorial*: de, ab, ti OR crossover*: de, ab, ti OR ((cross NEXT/1 over*): de, ab, ti) OR placebo*: de, ab, ti OR ((doubl* NEAR/1 blind*): de, ab, ti) OR ((singl* NEAR/1 blind*): de, ab, ti) OR assign*: de, ab, ti OR allocat*: de, ab, ti OR volunteer*: de, ab, ti | 2,358,887 |

| 8 | #3 AND #6 AND #7 | 373 |

| 9 | #8 AND [embase]/lim NOT ([embase]/lim AND [medline]/lim) | 175 |

aSearch performed on March 13, 2019.

FIGURE A1.

Risk of bias of included trials. According to the Cochrane Collaboration tool,16 each item was graded as low risk (+), high risk (-), or unclear risk (?). The included trials were then graded as low quality (L), high quality (H), or moderate quality (M) based on the criteria as described by Zhao et al.49

TABLE A2.

Meta-regression P Valuesa

| Characteristic | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Function | |

| PRP category | .629 | .547 |

| Spinning approach | .075 | .153 |

| Activator | .549 | .098 |

| No. of injections | .565 | .249 |

| Randomization confirmed | .642 | .795 |

| Allocation concealment confirmed | .832 | .818 |

| Sufficient blinding | .394 | .407 |

| Control group | .033; .147b | .217 |

| Outcome measure instrument | .921 | NA |

| Follow-up duration | .058 | .228 |

aNA, not applicable; PRP, platelet-rich plasma.

bP value for meta-analysis restricted to high-quality trials.

Figure A2.

Forest plot for effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) compared with controls for functional improvement. IV, inverse variance.

Table A3.

Adverse Events

| Lead Author (Year) | No. of Adverse Events | |

|---|---|---|

| PRP Group | Control | |

| Sánchez (2012)38 | 26 | 24 |

| Vaquerizo (2013)44 | 7 | 9 |

| Lana (2016)24 | 0 | 0 |

| Smith (2016)40 | 0 | 1 |

| Joshi Jubert (2017)20 | 0 | 0 |

| Ahmad (2018)1 | 7 | 2 |

| Buendía-López (2018)4 | 0 | 2 |

| Louis (2018)26 | 1 | 2 |

| Nabi (2018)31 | 0 | 0 |

| Su (2018)42 | 8 | 5 |

| Wu (2018)45 | 0 | 0 |

| Yu (2018)48 | 28 | 30 |

| Huang (2019)17 | 5 | HA 2; CS 3 |

aCS, corticosteroid; HA, hyaluronic acid; PRP, platelet-rich plasma.

Table A4.

Publication Bias P Valuesa

| Group | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Function | |

| HA | .893 | |

| Corticosteroid | — | |

| Saline | — | |

| Overall | .100 | .016 |

aDashes indicate that <10 trials were included; thus, the publication bias was not assessed. Blank cells indicate analysis was not performed in this article. HA, hyaluronic acid.

Footnotes

Final revision submitted June 4, 2020; accepted July 6, 2020.

The authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

References

- 1. Ahmad HS, Farrag SE, Okasha AE, et al. Clinical outcomes are associated with changes in ultrasonographic structural appearance after platelet-rich plasma treatment for knee osteoarthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:960–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andia I, Maffulli N. Platelet-rich plasma for managing pain and inflammation in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9:721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Corticosteroid injections for osteoarthritis of the knee: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2004;328:869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buendía-López D, Medina-Quirós M, Fernández-Villacañas Marín MÁ. Clinical and radiographic comparison of a single LP-PRP injection, a single hyaluronic acid injection and daily NSAID administration with a 52-week follow-up: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Traumatol. 2018;19:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cerza F, Carni S, Carcangiu A, et al. Comparison between hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma, intra-articular infiltration in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2822–2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang KV, Hung CY, Aliwarga F, Wang TG, Han DS, Chen WS. Comparative effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma injections for treating knee joint cartilage degenerative pathology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:562–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cole BJ, Karas V, Hussey K, Pilz K, Fortier LA. Hyaluronic acid versus platelet-rich plasma: a prospective, double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing clinical outcomes and effects on intra-articular biology for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dai WL, Zhou AG, Zhang H, Zhang J. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:659–670.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dragoo JL, Braun HJ, Durham JL, et al. Comparison of the acute inflammatory response of two commercial platelet-rich plasma systems in healthy rabbit tendons. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1274–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duymus TM, Mutlu S, Dernek B, Komur B, Aydogmus S, Kesiktas FN. Choice of intra-articular injection in treatment of knee osteoarthritis: platelet-rich plasma, hyaluronic acid or ozone options. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma intra-articular knee injections show no superiority versus viscosupplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1575–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Forogh B, Mianehsaz E, Shoaee S, Ahadi T, Raissi GR, Sajadi S. Effect of single injection of platelet-rich plasma in comparison with corticosteroid on knee osteoarthritis: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2016;56:901–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fortier LA, Barker JU, Strauss EJ, McCarrel TM, Cole BJ. The role of growth factors in cartilage repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2706–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. , eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Version 6.1. Cochrane Collaboration; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang Y, Liu X, Xu X, Liu J. Intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma, hyaluronic acid or corticosteroids for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective randomized controlled study. Orthopade. 2019;48:239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jevsevar DS. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline. 2nd ed. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones IA, Togashi R, Wilson ML, Heckmann N, Vangsness CT, Jr. Intra-articular treatment options for knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15:77–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Joshi Jubert N, Rodríguez L, Reverté-Vinaixa MM, Navarro A. Platelet-rich plasma injections for advanced knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5:2325967116689386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kanchanatawan W, Arirachakaran A, Chaijenkij K, et al. Short-term outcomes of platelet-rich plasma injection for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:1665–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khoshbin A, Leroux T, Wasserstein D, et al. The efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review with quantitative synthesis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:2037–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lai LP, Stitik TP, Foye PM, Georgy JS, Patibanda V, Chen B. Use of platelet-rich plasma in intra-articular knee injections for osteoarthritis: a systematic review. PM R. 2015;7:637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lana JF, Weglein A, Sampson SE, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing hyaluronic acid, platelet-rich plasma and the combination of both in the treatment of mild and moderate osteoarthritis of the knee. J Stem Cells Regen Med. 2016;12:69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laudy AB, Bakker EW, Rekers M, Moen MH. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:657–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Louis ML, Magalon J, Jouve E, et al. Growth factors levels determine efficacy of platelets rich plasma injection in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized double blind noninferiority trial compared with viscosupplementation. Arthroscopy. 2018;34:1530–1540.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Manheimer E, Linde K, Lao L, Bouter LM, Berman BM. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:868–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meheux CJ, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM, Varner KE, Harris JD. Efficacy of intra-articular platelet-rich plasma injections in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; the PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, Echko M, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA. 2018;319:1444–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nabi BN, Sedighinejad A, Mardani-Kivi M, Haghighi M, Roushan ZA, Biazar G. Comparing the effectiveness of intra-articular platelet-rich plasma and corticosteroid injection under ultrasound guidance on pain control of knee osteoarthritis. Adv J Emerg Med. 2018;20(3):e62157. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, Marwaha N, Jain A. Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Hassanabadi H, et al. Knee osteoarthritis injection choices: platelet-rich plasma (PRP) versus hyaluronic acid (a one-year randomized clinical trial). Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;8:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Ahangar AG, Abadi PH, Mojgani P, Ahangar OG. Efficacy of intra-articular injection of a newly developed plasma rich in growth factor (PRGF) versus hyaluronic acid on pain and function of patients with knee osteoarthritis: a single-blinded randomized clinical trial. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;10:1179544117733452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Riboh JC, Yanke AB, Cole BJ. Effect of leukocyte concentration on the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sadabad HN, Behzadifar M, Arasteh F, Behzadifar M, Dehghan HR. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid for treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Electron Physician. 2016;8:2115–2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sánchez M, Fiz N, Azofra J, Usabiaga J, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF-Endoret) versus hyaluronic acid in the short-term treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:1070–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shen L, Yuan T, Chen S, Xie X, Zhang C. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith PA. Intra-articular autologous conditioned plasma injections provide safe and efficacious treatment for knee osteoarthritis: an FDA-sanctioned, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Souzdalnitski D, Narouze SN, Lerman IR, Calodney A. Platelet-rich plasma injections for knee osteoarthritis: systematic review of duration of clinical benefit. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2015;19:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Su K, Bai Y, Wang J, Zhang H, Liu H, Ma S. Comparison of hyaluronic acid and PRP intra-articular injection with combined intra-articular and intraosseous PRP injections to treat patients with knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:1341–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Uslu Güvendi E, Aşkin A, Güvendi G, Koçyiğit H. Comparison of efficiency between corticosteroid and platelet rich plasma injection therapies in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Rheumatol. 2018;33:273–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vaquerizo V, Plasencia MA, Arribas I, et al. Comparison of intra-articular injections of plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF-Endoret) versus Durolane hyaluronic acid in the treatment of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:1635–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wu YT, Hsu KC, Li TY, Chang CK, Chen LC. Effects of platelet-rich plasma on pain and muscle strength in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;97:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xu Z, Luo J, Huang X, Wang B, Zhang J, Zhou A. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in pain and self-report function in knee osteoarthritis: a best-evidence synthesis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yan R, Gu Y, Ran J, et al. Intratendon delivery of leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma improves healing compared with leukocyte-rich platelet-rich plasma in a rabbit Achilles tendinopathy model. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:1909–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yu W, Xu P, Huang G, Liu L. Clinical therapy of hyaluronic acid combined with platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:2119–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhao JG, Zeng XT, Wang J, Liu L. Association between calcium or vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;318:2466–2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang HF, Wang CG, Li H, Huang YT, Li ZJ. Intra-articular platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:445–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]