We read with interest the study by de Lusignan et al., who found that, among 1970,314 UK primary care patients aged ≥ 45 years, being male, increasing age, chronic disease, Black ethnicity and deprivation were associated with excess mortality during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic1. These findings highlight the unequal burden of COVID-19 across society and reflect our patient and staff experience at North Middlesex University Hospital (NMUH)2. NMUH is located in a socioeconomically and ethnically diverse area of London and, early in the pandemic, was identified as the second most COVID-19 pressured NHS trust in the UK3. During the first wave, 24 out of 26 wards were converted to COVID-19 care, intensive care capacity was doubled, and many non-acute medical services were moved offsite. Many healthcare workers (HCW) were redeployed to the frontline where they faced a potent combination of occupational and sociodemographic factors influencing COVID-19 risk.

Between 4th June and 3rd July 2020, voluntary SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing was offered to the NMUH workforce. Staff were invited to complete an online questionnaire detailing co-morbidities, occupational and sociodemographic factors. Responses were anonymously linked to antibody results using occupational health numbers. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with seropositivity. Forward stepwise selection was used to determine which variables to retain in the model and checked against backward elimination. Base demographics of age, sex and ethnicity were always retained in the model. Variables tested for inclusion were underlying risk group, location of residence, Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) quintile, job banding, job role, workplace setting, patient interaction, HCW in household, and individual sites of work: emergency department (ED), endoscopy, estates, human resources and finance, intensive care, maternity, medicine, non-clinical, oncology, outpatient department, pathology, paediatrics, pharmacy, radiology, surgery, senior management, theatres, therapies. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata v.14.2. Total serology tests, positive tests and positivity rates were plotted according to postcode, alongside IMD score and ethnicity using Microsoft Excel. This evaluation was conducted for service improvement and did not require ethical approval according to the NHS Health Research Authority algorithm.

Of 3945 invited staff, 3285 were tested and completed the survey. Overall seropositivity was 35.7% (1173/3285), median age was 41 (IQR 31, 51) years and 72% (2369/3285) were female; White British/Irish HCW represented 23% (764/3285), while 70% (2293/3285) were from ethnic minority backgrounds, most commonly Black African (738/3285, 24%) and the Indian Subcontinent (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan; 484/3285, 15%). Overall, 79% (2585/3285) reported no comorbidities, two-thirds lived within the most deprived quintiles (IMD 1, 1021/3285, 31%; IMD 2, 1024/3285, 31%). In total, 31% (1029/3285) were nursing and midwifery staff, followed by administrative (577/3285, 18%) and medical (497/3285, 15%) staff. Most worked in clinical areas (2796/3285, 85%) with patient contact (2562/3285, 78%). A third were in the lowest two NHS job bands (1177/3285, 36%).

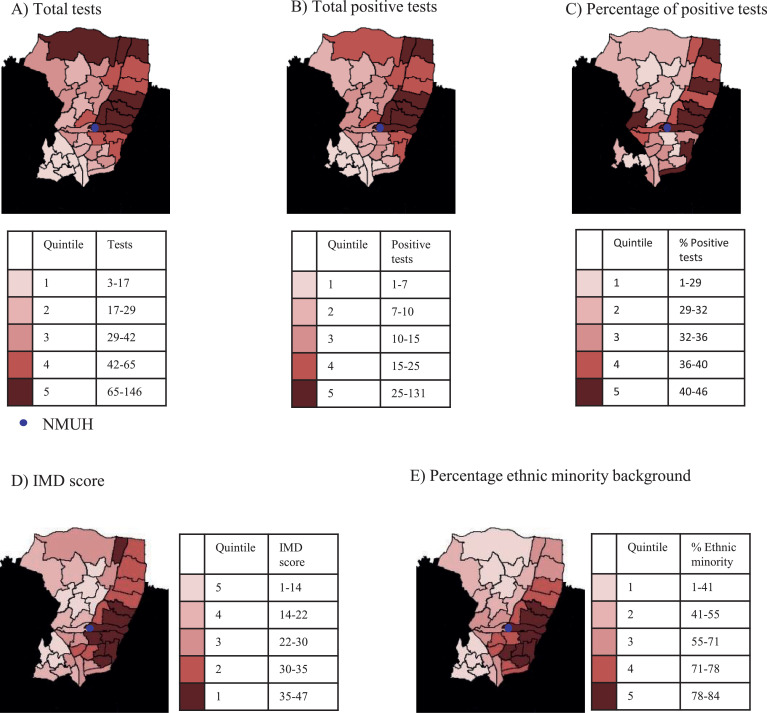

Half the staff tested (1692/3285, 52%) lived in Enfield and Haringey Boroughs, adjacent to NMUH. Staff seropositivity rates were highest to the East of Enfield and Haringey, corresponding to the most deprived wards with greatest ethnic diversity (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

(A) Total number of SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests at ward level (wards with ≥ 3 tests included to maintain anonymity). (B) Total positive SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests at ward level (wards with ≥ 3 tests included to maintain anonymity). (C) Percentage of positive SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests by ward. (D) Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score (2019) by ward. Quintile 1 (most deprived), Quintile 5 (least deprived). (E) Percentage of residents from an ethnic minority background by ward (Census data, 2011). Data from Public Health England, https://www.localhealth.org.uk/. In all figures, wards were divided into even quintiles and then coloured by quintile. The values contained within each quintile are included in the quintile legends. Maps generated using the Greater London Authority mapping template, https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/excel-mapping-template-for-london-boroughs-and-wards.

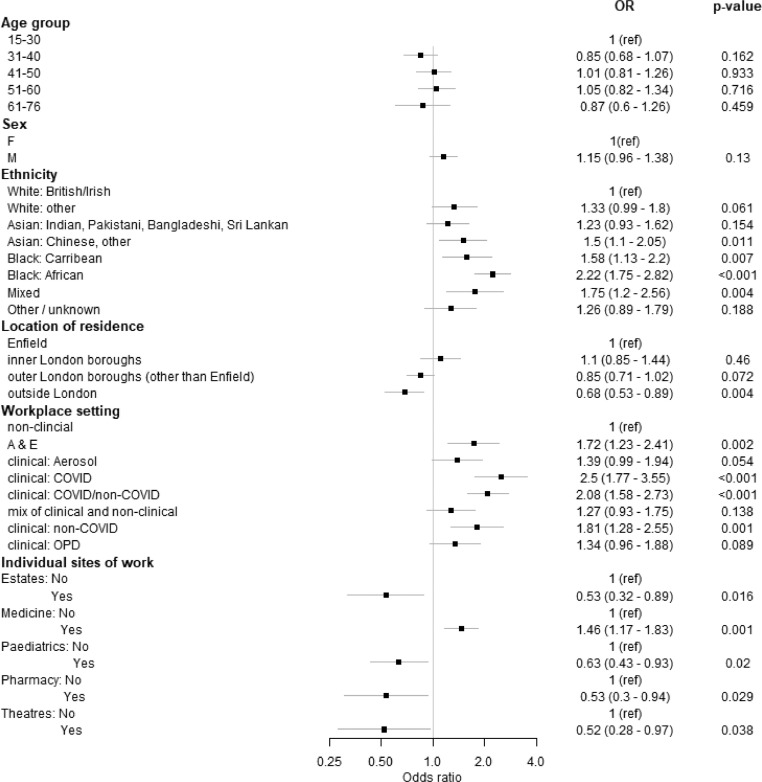

In a multivariable logistic regression model for seropositivity, ethnicity and location of residence were the sociodemographic factors reaching significance for inclusion (Fig. 2 ). All ethnicities had increased odds of seropositivity compared with White British/Irish staff. Black African staff were at greatest risk (Odds Ratio 2.22, 95% Confidence Interval 1.75–2.82, p < 0.001), followed by mixed ethnicity (OR 1.75, 95% CI 1.2–2.56, p = 0.004), Black Caribbean (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.13–2.2, p = 0.007), Asian Chinese/Other (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.05, p = 0.01). Staff who identified as White Other and from the Indian subcontinent also had increased odds of seropositivity, but this did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot: multivariable logistic regression model for antibody status according to sociodemographic and occupational factors, following variable reduction. For individual sites of work: Yes – works in that site, No- does not work in that site. Odds ratio, OR. Outpatient department, OPD. A&E – Accident and Emergency (Emergency department). Clinical: Aerosol – refers to inpatient wards where aerosol-generating procedures (AGP) are carried out. Clinical: COVID, Clinical: COVID/non-COVID (mixed COVID), Clinical: non-COVID – refer to inpatient wards with no AGP.

In the same model, workplace setting and certain individual sites of work were the only occupational factors reaching significance for inclusion (Fig. 2). All clinical staff had increased odds of seropositivity compared to non-clinical staff. The greatest risk was in COVID-19 wards not performing aerosol generating procedures (AGP) (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.77–3.55, p < 0.001), mixed-COVID-19 (OR 2.08 95% CI 1.58–2.73, p < 0.001), non-COVID-19 wards (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.28–2.55, p = 0.001) and ED (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.23–2.41, p = 0.002). Staff working in AGP areas had increased odds of seropositivity (OR 1.39, 95% CI 0.99–1.94, p = 0.054), but this was of borderline significance, while outpatient areas (OR 1.34, 95% CI 0.96–1.88, p = 0.089) was not statistically significant. Medical department staff had increased odds of seropositivity (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.17–1.83, p = 0.001) compared to other sites of work.

We found that staff at highest risk worked in non-AGP COVID-19 wards and were from minority ethnic groups, and the highest seropositivity rates mapped to the most deprived local wards. Workforce ethnic diversity and locality was striking; the majority of staff lived in adjacent boroughs and 70% were from minority ethnic backgrounds, compared to 22% in the wider NHS4. Similar occupational risk factors have been reported in other HCW seroprevalence surveys, but their influence in combination with sociodemographic factors on COVID-19 risk in HCWs has not been fully described5 , 6. One large American HCW seroprevalence study found that community and demographic factors, in particular Black ethnicity and contact with a suspected COVID-19 case, were more predictive of seropositivity than occupational factors. Similarly, we found staff seropositivity geographically mirrored COVID-19 cases among our inpatient population, mapping to local ethnically diverse and deprived areas2. The Health Service Journal reported a disproportionate number of NHS staff deaths among ethnic minorities7. Concerningly, British Medical Association surveys have found ethnic minority doctors feel less protected from COVID-19 at work than their White colleagues8. Furthermore, ethnic minorities are currently under-represented in national HCW surveillance studies9. Recent data suggest that there is significantly lower COVID-19 vaccine uptake among HCWs from minority ethnic groups and living in more deprived neighbourhoods, thus exacerbating these disparities9 , 10.

Further work is needed to understand the interplay of occupational and sociodemographic risk factors facing HCWs. Inequalities must be urgently addressed in order to better protect NHS staff during the ongoing pandemic.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.de Lusignan S., Joy M., Oke J., McGagha D., Nicholson B., Sheppard J., et al. Disparities in the excess risk of mortality in the first wave of COVID-19: cross sectional study of the English sentinel network. J Infect. 2020;81(5):785–792. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gil E., Weller S., Rokadiya S., Mirfenderesky M., Ahmed A., Schwenk A. Letter in response to 'Modelling SARS-CoV2 spread in London: approaches to lift the lockdown' local experience, national questions. How local is local enough? J Infect. 2021;82(1):e1–e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batchelor G. Revealed: The hospitals facing the most pressure to meet coronavirus demand. Available at: https://www.hsj.co.uk/quality-and-performance/revealed-the-hospitals-facing-most-pressure-to-meet-coronavirus-demand/7027354.article.

- 4.Digital N. NHS workforce. Available at: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/workforce-and-business/workforce-diversity/nhs-workforce/latest. Accessed 24 January 2021.

- 5.Grant J.J., Wilmore S.M.S., McCann N.S., Donnelly O., Lai R.W.L., Kinsella M.J., et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in healthcare workers at a London NHS Trust. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(2):212–214. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyre D.W., Lumley S.F., O'Donnell D., Campbell M., Sims E., Lawson E., et al. Differential occupational risks to healthcare workers from SARS-CoV-2 observed during a prospective observational study. Elife. 2020;9:e60675. doi: 10.7554/eLife.60675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook T., Kursumovic, E., Lennane, S. Exclusive: deaths of NHS staff from covid-19 analysed. Available at: https://www.hsj.co.uk/exclusive-deaths-of-nhs-staff-from-covid-19-analysed/7027471.article. Accessed 23 February 2021.

- 8.Mahase E. Covid-19: ethnic minority doctors feel more pressured and less protected than white colleagues, survey finds. BMJ. 2020;369:m2506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall V.J., Foulkes S., Saei A., Andrews N., Oguti B., Charlett A., et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against infection and COVID-19 vaccine coverage in healthcare workers in England, multicentre prospective cohort study (the SIREN study) Prepr Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00790-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin C.A., Marshall C., Patel P., Goss C., Jenkins D.R., Ellwood C., et al. Association of demographic and occupational factors with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine uptake in a multi-ethnic UK healthcare workforce: a rapid real-world analysis. MedRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003823. 2021.02.11.21251548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]