Abstract

Intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration and associated back pain place a significant burden on the population. IVD degeneration is a progressive cascade of cellular, compositional, and structural changes, which results in a loss of disc height, disorganization of extracellular matrix architecture, tears in the annulus fibrosus which may involve herniation of the nucleus pulposus, and remodeling of the bony and cartilaginous endplates (CEP). These changes to the IVD often occur concomitantly, across the entire motion segment from the disc subcomponents to the CEP and vertebral bone, making it difficult to determine the causal initiating factor of degeneration. Furthermore, assessments of the subcomponents of the IVD have been largely qualitative, with most studies focusing on a single attribute, rather than multiple adjacent IVD substructures. The objective of this study was to perform a multiscale and multimodal analysis of human lumbar motion segments across various length scales and degrees of degeneration. We performed multiple assays on every sample and identified several correlations between structural and functional measurements of disc subcomponents. Our results demonstrate that with increasing Pfirrmann grade there is a reduction in disc height and nucleus pulposus T2 relaxation time, in addition to alterations in motion segment macromechanical function, disc matrix composition and cellular morphology. At the cartilage endplate‐vertebral bone interface, substantial remodeling was observed coinciding with alterations in micromechanical properties. Finally, we report significant relationships between vertebral bone and nucleus pulposus metrics, as well as between micromechanical properties of the endplate and whole motion segment biomechanical parameters, indicating the importance of studying IVD degeneration as a whole organ.

Keywords: atomic force microscopy, histology, intervertebral disc degeneration, magnetic resonance imaging, microcomputed tomography, Pfirrmann grade

Intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration and associated back pain place a significant burden on the population. IVD degeneration is a progressive cascade of cellular, compositional and structural changes, which results in a loss of disc height, disorganization of extracellular matrix architecture, tears in the annulus fibrosus which may involve herniation of the nucleus pulposus, and remodeling of the bony and cartilaginous endplates (CEP). These changes to the IVD often occur concomitantly, across the entire motion segment from the disc subcomponents to the CEP and vertebral bone, making it difficult to determine the causal initiating factor of degeneration. Our results demonstrate that with increasing Pfirrmann grade there is a reduction in disc height and nucleus pulposus T2 relaxation time, in addition to alterations in motion segment macromechanical function, disc matrix composition and cellular morphology. At the cartilage endplate‐vertebral bone interface, substantial remodeling was observed coinciding with alterations in micromechanical properties. Finally, we report significant relationships between vertebral bone and nucleus pulposus metrics, as well as between micromechanical properties of the endplate and whole motion segment biomechanical parameters, indicating the importance of studying IVD degeneration as a whole organ.

1. INTRODUCTION

The intervertebral disc (IVD) is comprised of multiple structurally distinct anatomical regions (Huang et al., 2014). The inner nucleus pulposus (NP) is a hydrated material, rich in proteoglycans, mainly aggrecan, and type II collagen (Cassidy et al., 1989; Walker & Anderson, 2004). The NP is encapsulated by the annulus fibrosus (AF), which is composed of type I and type II collagen, oriented at alternating angles of ±30° along the longitudinal axis of the spine, arranged to form an angle‐ply structure (Inoue, 1976). The NP and AF act synergistically to transfer load and facilitate mobility, such that when the disc is compressed, hydrostatic pressure is generated within the NP which expands radially to engage the AF, where tensile circumferential stresses further resist expansion (Hukins, 1992; Humzah & Soames, 1988).

The AF and NP are constrained superiorly and inferiorly by the vertebral endplates. The endplates serve as an anchor point for both the AF and NP, and act as semipermeable membranes to enable nutrient and fluid exchange between the avascular IVD and the vascularized vertebral bodies (Fields et al., 2018). The endplate is composed of two regions: a thin plate of hyaline‐like cartilage (termed the cartilaginous endplate, CEP, ~1 mm thickness) and the thin cortical shell of bone at the vertebral body (bony endplate, BEP) (Rodriguez et al., 2012). The CEP contains proteoglycans and collagen fibrils (primarily types II, IX and XI) that are oriented parallel to the vertebral body (Roberts et al., 1989).

Structural failure of the IVD, mediated by aberrant cellular and mechanical responses during degeneration, is a leading cause of back pain (de Schepper et al., 2010). IVD degeneration is the most frequently reported musculoskeletal problem in the aging population, with a lifetime prevalence of 90% in the United States (CDC MMWR, 2009). Despite the significant clinical burden of IVD degeneration, the underlying mechanisms leading to end stage disease in humans is poorly understood. Degeneration is marked by a progressive cascade of cellular, compositional and structural changes across the whole vertebral body‐IVD‐vertebral body motion segment (Haefeli et al., 2006; Walker & Anderson, 2004). Early degenerative changes are usually observed in the NP, where decreased aggrecan content leads to reduced hydration (Buckwalter, 1995) and impaired mechanical function (Urban & Roberts, 2003). A less hydrated, more fibrotic NP (Iatridis et al., 1996) compromises the ability of the NP to swell and engage the surrounding AF to transfer forces between adjacent vertebral bodies, which can ultimately contribute to AF disruption and disorganization (Iatridis et al., 1999). Mechanically, the AF and NP stiffen with increasing degenerative grade when tested as isolated tissues; However, when evaluated as a composite, the modulus of the whole motion segment is reduced with degeneration (Campana et al., 2011; Cortes et al., 2014; Pollintine et al., 2010; Stefanakis et al., 2014).

With advanced IVD degeneration, collapse of disc height and endplate damage are often noted (Moore, 2000). At this stage, endplate lesions can be identified by both histology and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; Hilton et al., 1976; Mok et al., 2010; Samartzis et al., 2016), and data suggest that structural disturbances at this interface are associated with back pain (Berg‐Johansen et al., 2017a) and local inflammation (Dudli et al., 2017; Schroeder et al., 2017). Further, changes to the endplate during aging, such as sclerosis and hyper‐mineralization, may contribute to IVD degeneration by hindering nutrient diffusion and waste product removal from the avascular disc space (Ashinsky et al., 2020; Kandel et al., 2008). Rutges et al. (2011) were the first to quantify subchondral BEP changes; they reported increases in bone volume and the thickness (diameter) of individual trabeculae adjacent to more degenerative discs. Although a thickened endplate increases diffusion distances by which nutrients can enter the disc, there are only a few studies of human discs in the literature that have linked subchondral sclerosis to disc nutrition. Occlusion of marrow channels within the endplates (Benneker et al., 2005a) and decreased endplate permeability (Nachemson et al., 1970) positively correlated with disc degeneration. Other studies provide conflicting findings on the role of sclerosis in disc degeneration. In contrast to these earlier works, more recent studies have shown that BEP sclerosis decreased, while porosity and permeability increased with age and degeneration, suggesting that perhaps changes to the CEP may be more significant in contributing to degeneration (Rodriguez et al., 2011, 2012; Zehra et al., 2015).

Although these prior studies provided important information on the degenerative changes to each region of the disc and endplates in isolation, degeneration at the whole motion segment level across multiple anatomic regions and length scales has been relatively understudied. Therefore, in this study we performed a quantitative multiscale and multimodal evaluation of degeneration in 30 spinal motion segments from seven human donors, ranging in degeneration status from mild to severe. Micro‐ and macroscale compositional and mechanical alterations to the NP, AF, CEP, BEP were assessed in each sample, across anatomic regions and length scales, and correlations between these values were determined as a function of degenerative state.

2. METHODS

Seven intact human lumbar spines, spanning from levels L1‐S1, yielding a total of 28 motion segments for analysis, were purchased fresh‐frozen from the National Disease Research Interchange and Science Care. Five of the seven spines were from male donors (60‐ to 90‐years old) and the remaining two were female donors (60‐ to 66‐years old). Spines were stored at −20°C for up to 4 weeks prior to analysis. Deidentified patient demographics are listed in Table 1 and sample allocation for experimental outcomes are outlined in Figure 1. Following procurement, each lumbar spine underwent MRI at 3 T (Siemens Magnetom TrioTim) to obtain sagittal T2‐weighted images and a series of images for T2 mapping (MTX = 0.5 × 0.5 × 5 mm, TE = 13 × i, i = 1, 2 … 6). A midsagittal slice of the T2‐weighted images was utilized for Pfirrmann grading (Pfirrmann et al., 2001), which was performed by two independent observers. Disc heights were also quantified using a custom Matlab code from the midsagittal T2‐weighted images (Martin et al., 2014). Following Pfirrmann grading, T2 parametric maps were generated in ImageJ; NP and AF T2 (ms) were calculated as previously described (Martin et al., 2015). T2‐weighted MRI is a clinical imaging modality that assesses IVD structure and tissue hydration; generally, a higher signal intensity correlates with greater water content and tissue hydration (Gold et al., 2004). While T2‐weighted imaging provides a qualitative assessment of disc structure, T2 mapping allows the quantification of T2 relaxation times within the disc, which correlate with disc water and proteoglycan content (Gold et al., 2004; Gullbrand et al., 2016).

TABLE 1.

Donor demographics

| Donor | Sex | Age | Lumbar levels | Pfirrmann grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 65 | L1/2 | 3 |

| L2/3 | 4 | |||

| L3/4 | 5 | |||

| L4/5 | 4 | |||

| L5/S1 | 5 | |||

| 2 | M | 60 | L1/2 | 2 |

| L2/3 | 2 | |||

| L3/4 | 2 | |||

| L4/5 | 2 | |||

| L5/S1 | 5 | |||

| 3 | M | 67 | L3/4 | 2 |

| L4/5 | 3 | |||

| 4 | M | 90 | L1/2–L4/5 | 4 |

| 5 | F | 66 | L1/2, L2/3, L5/S1 | 5 |

| 6 | M | 69 | L1/2 | 2 |

| L2/3 | 4 | |||

| L3/4 | 3 | |||

| L4/5 | 3 | |||

| L5/S1 | 3 | |||

| 7 | F | 60 | L2/3 | 3 |

| L3/4 | 3 | |||

| L4/5 | 3 | |||

| L5/S1 | 2 |

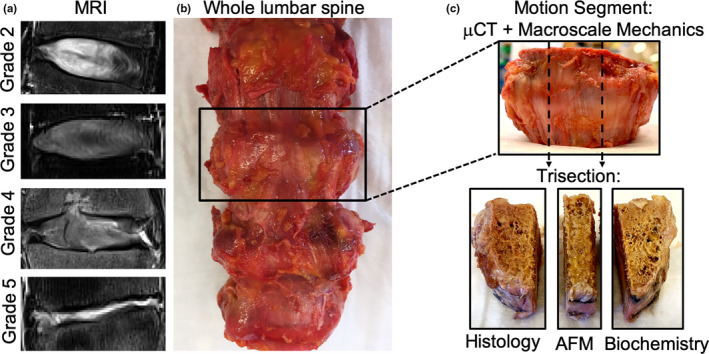

FIGURE 1.

(a) Representative T2‐weighted MRIs for each Pfirrmann grade, (b) Gross anatomic photograph of an intact lumbar spine, (c) representative motion segment designated for µCT and macroscale mechanics, which was trisected in the sagittal plane for histology, atomic force microscopy (AFM), or biochemistry

Following MRI, each lumbar spine was dissected into bone‐disc‐bone motion segments and the posterior and lateral bony elements were removed with a hand saw (Figure 1). Each motion segment was imaged through µCT at 20.5 µm resolution (Scanco VivaCT80) to investigate alterations to the vertebral endplate with degeneration. Bone morphometric parameters were computed across a volume of interest within the central 1000 slices, spanning the entire lateral width endplate regions and to a depth of 5 mm into the vertebral body. Bone morphometric parameters were quantified for the superior and inferior endplate of each disc sample, yielding two data points per disc sample for each parameter.

After µCT imaging, motion segments were frozen at −20°C for up to 1 week until biomechanical testing. Prior to testing, motion segments were thawed and potted in custom fixtures using low‐melting temperature indium casting alloy (McMaster‐Carr). Each sample was subjected to a mechanical testing protocol consisting of 20 cycles of compression (0 to −750 N, ~1 body weight) at 0.5 Hz followed by 1 h of creep loading at −750 N (Instron 5948) (O’Connell et al., 2011). All testing was performed at room temperature in a bath of phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) with protease inhibitors (SIGMAFAST Protease Inhibitor Tablets; Sigma‐Aldrich). Fiducial markers were painted on the superior and inferior aspects of the disc and optical tracking was performed using a high‐resolution digital camera (Figure S1) (A3800; Basler) and a custom MATLAB texture tracking program (Gullbrand et al., 2016; Martin et al., 2013) to track displacement. Mechanical properties (toe and linear region modulus, transition and maximum strain) were calculated from the optically tracked force‐displacement curves obtained from the 20th cycle of compression and normalized to disc area and height measured from T2 MRI maps. Disc geometry was calculated using a custom MATLAB code, available for download in the supplemental material in Martin et al. (2015). Briefly, disc cross‐sectional area was defined as the number of pixels within a manually segmented whole disc region from a mid‐axial slice, multiplied by the in‐plane scan resolution. To calculate disc height, discs were manually segmented from a mid‐sagittal slice, and the area of the disc in the midsagittal plane divided by the width of the disc in the anterior‐posterior direction.

Following mechanical testing, motion segments were equilibrated for 1 h in PBS with protease inhibitors before being trisected in the sagittal plane (Figure 1). In every sample, a middle, ~10 mm thick sagittal section was designated for histology. The two lateral portions of each motion segment were randomly designated for atomic force microscopy (AFM) or biochemical testing. The presence of NP and CEP tissue in the lateral thirds was confirmed visually. Samples designated for AFM were embedded in optimal cutting temperature media and cryosectioned in the sagittal plane to 50 µm thick using Kawamoto's film method (Kawamoto & Kawamoto, 2014). After thawing in PBS with protease inhibitors, AFM‐nanoindentation was performed on these sections using microspherical colloidal tips (R ≈ 5 μm, nominal k ≈ 2.0 N/m, Q:NSC36/Tipless/Cr‐Au, cantilever C; NanoAndMore) using a Dimension Icon AFM (BrukerNano). Indentation was applied at a z‐piezo displacement rate of 10 μm/s to a maximum load of ≈120 nN at the middle and outer AF, AF‐BEP interface, and CEP. Nanoindentation was repeated three times at the same location, and averaged, to ensure repeatability. The indentation modulus, E ind (MPa), at each location was calculated by fitting the entire loading portion of each force‐displacement curve to the finite thickness‐corrected Hertz model (Dimitriadis et al., 2002), via least squares linear regression in MATLAB, as previously described (Li et al., 2017). AFM nanoindentation was not performed on Pfirrmann grade 5 discs due to the inability to accurately distinguish disc substructures.

Cryosections from Pfirrmann grades 2, 3, and 4 discs were also stained using a von Kossa staining kit (Abcam) to examine calcium deposition in the CEP. Grade 5 discs were not stained with von Kossa due to the near complete resorption of the CEP in these specimens. Samples designated for histology were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Sigma‐Aldrich), decalcified (Formical 2000; StatLab), processed into paraffin, and sectioned to 10 µm thick in the sagittal plane. Mid‐sagittal sections were stained with Alcian blue and picrosirius red (disc structure & proteoglycan/collagen content), or hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; cell morphology), or Mallory‐Heidenhain trichrome (CEP structure). Sections stained with Alcian blue/picrosirius red were utilized for CEP thickness measurements, where three locations (anterior, middle, posterior) were measured on both the superior and inferior endplates of each disc (Aperio ImageScope; Leica). The thickness at these three locations was averaged, yielding values for both the superior and inferior endplate for each disc sample. These same sections were imaged at 20× using brightfield microscopy (Aperio CS2 Scanner; Leica) and second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging. SHG imaging for collagen localization and organization was performed using a Nikon A1 multiphoton microscope with 880 nm excitation, as previously described (Gullbrand et al., 2018, supplemental material). For each sample, z‐stacks of slides stained with Alcian blue/picrosirius red were obtained over a 10 μm thickness. Z‐stacks were imported into ImageJ and projected into an average intensity projection.

For samples designated for biochemical analysis of extracellular matrix composition, disc segments were manually separated into AF and NP portions. AF and NP tissues were distinguished visually by anatomic region and the lamellar structure of the AF. The AF and NP were individually digested overnight in proteinase K at 60°C. Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content of each region was determined using the dimethyl methylene blue dye binding assay (Farndale et al., 1982), and collagen content was quantified via the p‐diaminobenzaldehyde/chloramine‐T assay for ortho‐hydroxyproline (Reddy & Enwemeka, 1996). GAG and collagen content were normalized to sample wet weight.

Statistical analyses of results were performed in Prism (Graph Pad Software Inc.), with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation. The Shapiro–Wilk test for normality was first performed on all quantitative data. As data were not normally distributed, the a Kruskal–Wallis non‐parametric test was used to determine significant differences in NP and AF T2 values, bone morphometric parameters (BV/TV, Tb.N, Tb.Th, Tb.Sp.), GAG and collagen content, and micro‐ and macro‐ mechanical properties, for all motion segments in each Pfirrmann grade. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for all combinations of measured variables using Prism software.

3. RESULTS

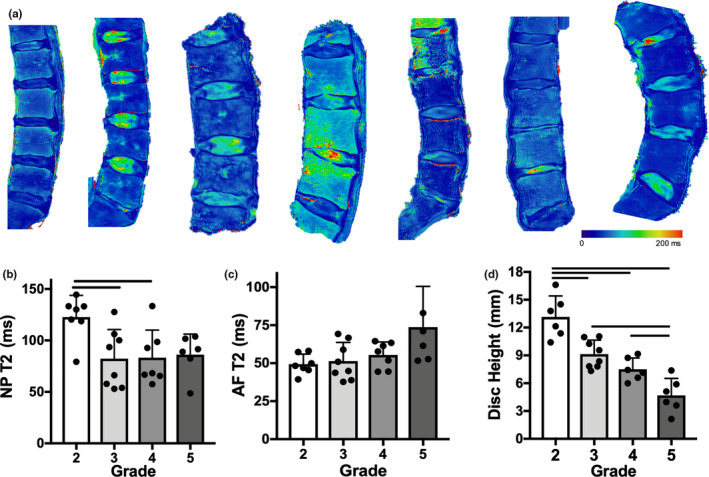

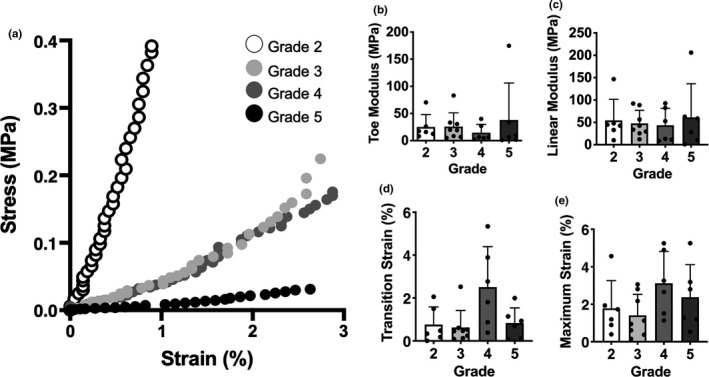

With increasing disc Pfirrmann grade, T2 relaxation times in the NP decreased, with significant differences observed between grade 2 discs and grades 3 and 4 discs. In contrast, AF T2 relaxation times increased with increasing Pfirrmann grade, with no significant differences detected between any of the groups (Figure 2a–c). Disc height progressively and significantly decreased with increasing degenerative grade (Figure 2d). Consistent with previous literature, macroscale mechanical testing of motion segments showed that stiffness decreased with increasing degeneration grade, as illustrated by the representative compressive stress‐strain curves (Figure 3a). However, there were no statistical differences identified in toe and linear moduli or transition and maximum strain across degenerative grades. (Figure 3b–e).

FIGURE 2.

(a) Lumbar spine T2 MRI maps of each donor, (b) nucleus pulposus (NP) T2 and (c) annulus fibrosus (AF) T2 relaxation times for each Pfirrmann grade, (d) disc height measurements for each disc. Bars denote statistical significance (p < 0.05)

FIGURE 3.

(a) Representative stress‐strain curve from whole motion segment biomechanical testing for each Pfirrmann grade, and corresponding (b) toe modulus, (c) linear modulus, (d) transition strain and (e) maximum strain calculations

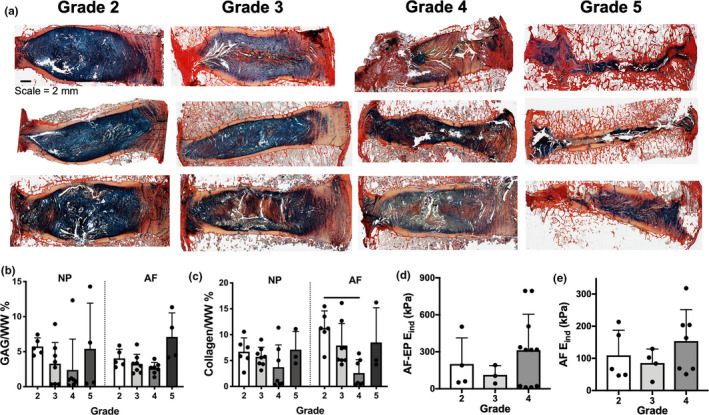

Marked structural changes to the motion segment were observed with increasing degenerative grade, as evidenced by Alcian blue and picrosirius red staining (Figure 4a). Increasing degenerative grade was frequently associated with disorganization and infolding of the lamellar structure of the AF, the presence of fissures and void spaces in the NP and AF, disruptions of the BEP, and a loss of disc height, particularly in grade 5 discs. With respect to ECM composition, there was less robust Alcian blue staining for proteoglycan staining in the NP with increasing degenerative grade, and a collagen‐rich band within the central NP was frequently observed in grades 3 and 4 discs. Alcian blue staining in the central region of the most severely degenerative grade 5 discs was evident, although this tissue was more morphologically similar to cartilage than NP. Picrosirius red staining for collagen in the AF decreased in intensity with increasing Pfirrmann grade, while proteoglycan staining increased in this region. These histological observations were confirmed quantitatively via biochemical assays, where NP and AF GAG content decreased from grades 2–4 and then subsequently increased in grade 5 discs, however, these changes were not statistically significant due to substantial variability by donor (Figure 4b). Collagen content showed similar trends, with a significant decrease in the AF region between grades 2 and 4 discs (Figure 4c). Despite these compositional changes, no statistically significant differences in the indentation modulus of the AF or its interface with the EP were observed with increasing degenerative grade (Figure 4d–e).

FIGURE 4.

(a) Representative alcian blue/picrosirius red stained histology sections from varying donors per Pfirrmann grade. (b) nucleus pulposus (NP) and annulus fibrosus (AF) glycosaminoglycan (GAG) and (c) collagen content, (d) indentation modulus (E ind) of the AF‐EP interface and (e) AF for Pfirrmann grades 2–4 discs. Bars denote statistical significance (p < 0.05)

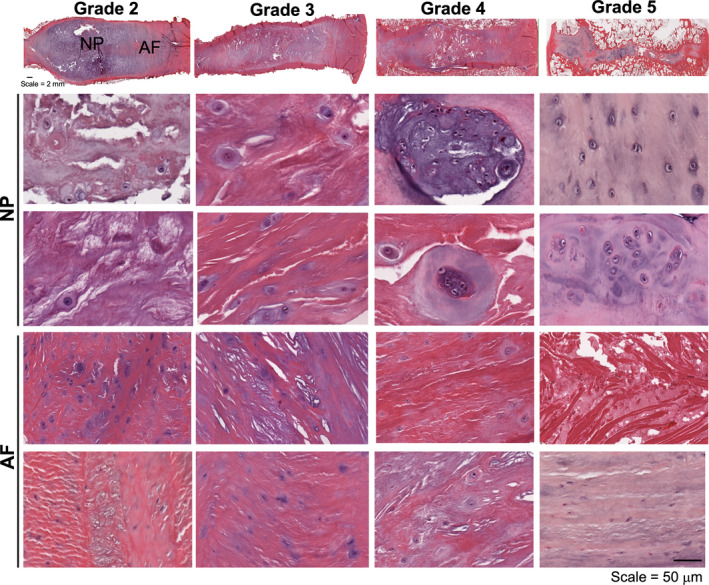

With respect to cellular morphology, H&E staining revealed that the cells within both the NP and AF underwent changes in aspect ratio with increasing degeneration (Figure 5). The cells within the NP of grade 2 discs were rounded and encased by a gelatinous matrix, whereas the cells within the AF were more elongated and densely packed. While the morphology of the NP cells in grade 3 discs appeared similar to grade 2 discs, there appeared to be an increase in cell density and early fibrotic remodeling of the matrix. AF cells in grade 3 discs were less elongated, and more rounded than in grade 2 AF, and the lamellae began to lose their structural integrity, with early signs of interlamellar delamination. In grade 4 discs, cells within the NP began to form clusters, and cells within the AF had largely shifted from an elongated phenotype to a rounded morphology. There was additional cluster formation in grade 5 discs, and the NP cells appeared similar in morphology to chondrocytes undergoing endochondral ossification. The native AF architecture in grade 5 discs was entirely disrupted with fibrotic remodeling of the matrix and reductions in cellularity.

FIGURE 5.

Representative macroscopic whole disc and nucleus pulposus (NP) and annulus fibrosus (AF) hematoxylin and eosin histology sections for each Pfirrmann grade

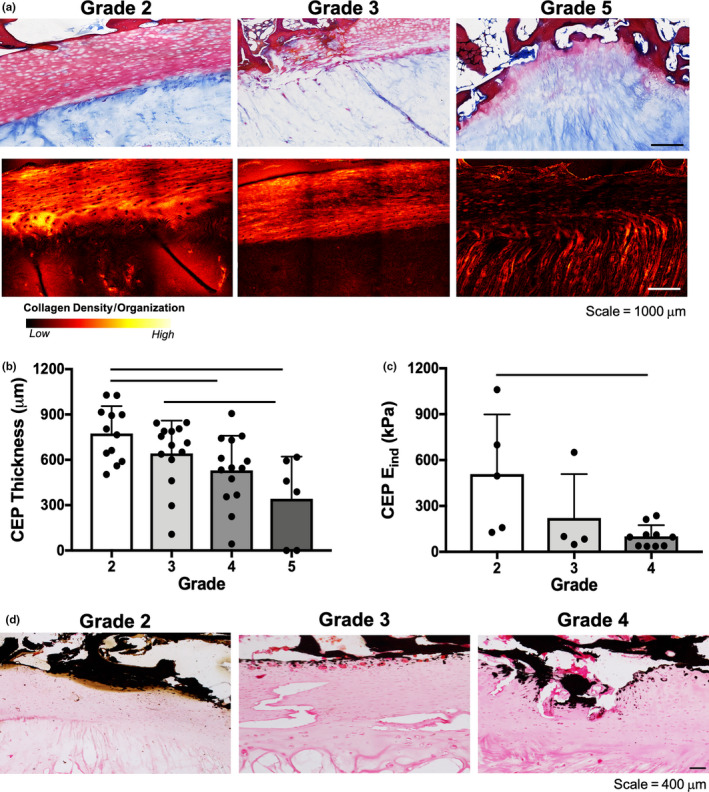

Marked structural and compositional changes were also observed within the CEP with increasing severity of disc degeneration. Sections stained with Mallory‐Heidenhain trichrome showed progressive resorption of the CEP and invasion of the CEP with trabecular bone with increasing degenerative grade (Figure 6a). CEP remodeling was further evidenced through SHG imaging which demonstrated a reduction in SHG signal intensity, suggesting reductions in collagen density and/or organization with increasing degenerative grade (Figure 6a). CEP thickness was significantly reduced between grades 2 and 4‐5 and grades 3 and 5 (Figure 6b), and the nanoscale stiffness of this region showed that the E ind of the CEP significantly decreased from grades 2–4 (Figure 6c).

FIGURE 6.

(a) Representative Mallory‐Heidenhain histology and second harmonic generation images of the cartilaginous endplate (CEP) for Pfirrmann grades 2, 3 and 5 discs. (b) CEP thickness measurements (superior and inferior endplate thickness are shown as separate data points for each disc sample) and (c) CEP indentation modulus (E ind), (d) von Kossa stained histology sections of the CEP for Pfirrmann grades 2, 3, 4 discs. Bars denote statistical significance (p < 0.05)

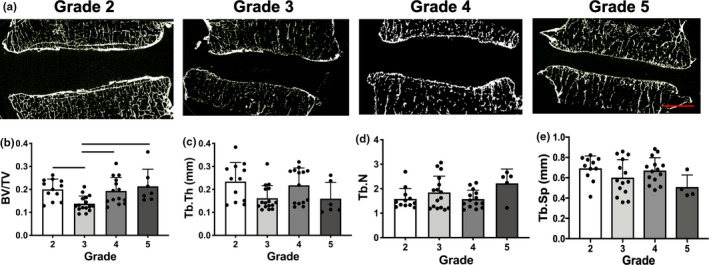

To further evaluate the CEP and adjacent bony remodeling, sections were stained with von Kossa for calcium. There was an increase in von Kossa staining in the CEP with increasing degenerative grade, particularly at the interface immediately adjacent to the vertebral bone (Figure 6d). Quantitative µCT analysis of the endplates and adjacent trabecular bone revealed a significant decrease in bone volume fraction between grades 2 and 3 discs, and significant increases between grade 3 and grades 4 and 5 discs (Figure 7a–c). However, no significant differences were identified between any of the groups for trabecular thickness, number or spacing (Figure 7c–e).

FIGURE 7.

(a) Representative sagittal µCT images for all Pfirrmann grades, scale = 5 mm. µCT quantification of (b) bone volume fraction (BV/TV), (c) trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), (d) trabecular number (Tb.N), and (e) trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp). Bars denote statistical significance (p < 0.05). Values obtained from the superior and inferior endplates of each disc sample are shown as separate data points

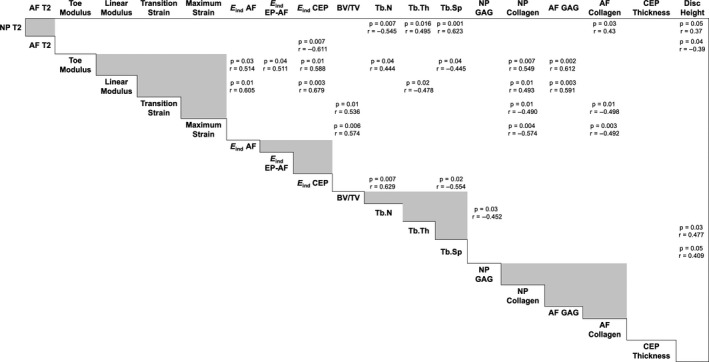

Finally, to assess correlations across length scales and anatomical regions of the motion segment with degeneration, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for all combinations of measured variables. The r‐ and p‐values for each statistically significant pair are shown in Figure 8. For simplicity, significant correlations between measures of the same modality (micro‐ and macro‐mechanical properties, µCT, biochemistry) are not shown, although many of these were strongly correlated with one another (Table S1). The complete correlation matrix for all combinations of quantitative variables is included in Table S1. The strongest positive correlations (r ≥ 0.6) were between microscale mechanical properties (E ind AF, EP‐AF, CEP) and macroscale mechanical properties (toe and linear modulus). Additionally, NP T2, a noninvasive marker of disc hydration status and matrix integrity (Gullbrand et al., 2016), was significantly positively correlated with the bone morphometric parameters trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) and trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp), and was negatively correlated with trabecular number (Tb.N). NP T2 was positively correlated, and AF T2 negatively correlated with disc height. Trabecular number and spacing were also strongly correlated with E ind of the CEP (r = 0.629 and r = −0.554). Disc height was significantly positively correlated with Tb.Th and Tb.Sp., however, these correlations were only moderate (r < 0.5).

FIGURE 8.

Matrix of the significant (p < 0.05) univariate correlations for all quantitative variables. Pearson correlation coefficients, r, are listed in each cell with significant correlations. Grey boxes indicate interdependent measurements

4. DISCUSSION

Intervertebral disc degeneration is a multifactorial process involving a complex interplay between environmental and genetic factors. Although there are multiple causative factors related to the initiation of the degeneration cascade, previous work suggests that degenerative changes occur across the entire motion segment from the disc subcomponents to the cartilage endplate and vertebral bone. While considerable evidence exists for each of these individual elements changing with degeneration, most studies focus on a single attribute, rather than multiple adjacent IVD substructures at the same time. Here, we sought to advance our understanding of whole motion segment IVD degeneration by performing a quantitative multiscale and multimodal analysis of human spinal motion segments across length scales and with varying degrees of degeneration.

Our findings show that the NP becomes compromised through a loss of GAG and thus, hydration, evidenced by reductions in T2 relaxation times in the NP with increasing degeneration, consistent with previous studies (Yoon et al., 2016). These biochemical changes were associated with whole motion segment softening, and disc height collapse, also consistent with previous literature (Cortes et al., 2014; Pollintine et al., 2010; Wilke et al., 2006). In the most severely degenerative discs, GAG staining and GAG and collagen content increased, which may indicate a shift in NP cell phenotype towards a more chondrocyte‐like phenotype as the motion segment begins to fuse through endochondral ossification. The AF region of the disc also underwent substantial remodeling with degeneration, characterized by disorganization of the lamellar architecture, transition to a more rounded cell phenotype, and the presence of fissures and tears in the tissue.

Damage to the CEP has also been postulated to negatively impact disc health. Structural damage can weaken the CEP, allowing for the IVD to bulge into the vertebral body, leading to NP and AF mechanical perturbations and aberrant disc cell metabolism (Adams et al., 2000; Brinckmann & Horst, 1985; Dolan et al., 2013; Ishihara et al., 1996; Ranu, 1993; Walsh & Lotz, 2004). Our data show that the CEP thins with increasing degeneration, loses its organized collagen matrix, and is replaced by bony calcifications. These findings are significant as they complement the in vitro work performed by Grant et al. (2016), who found that calcium inhibited collagen and proteoglycan synthesis in cultured CEP tissues. Further, increased calcification and loss of proteoglycan matrix can adversely impact tissue hydration, which may limit solute diffusion across the CEP and IVD (Sampson et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2019). Additionally, we observed fissures within several of the degenerative CEPs on histology, and future work will investigate their association with nerve and blood vessel ingrowth (Fields et al., 2014).

Although we observed obvious resorption and thinning of the CEP, the adjacent BEP and vertebral body underwent more complex changes with degeneration. Bone volume fraction decreased between grades 2 and 3, which may indicate thinning of the bone at these mild‐moderate degenerative grades. These changes were followed by an apparent thickening of the bone, demonstrated by an increase in bone volume fraction between grades 3 and 4. The literature relating vertebral bone composition and IVD degeneration is somewhat conflicting (Fields et al., 2014). Our data are consistent with this literature, suggesting dynamic changes in bone density with degeneration. Additional donors are required to overcome issues with donor‐to‐donor variations, particularly with respect to age and sex, that likely confound this bone morphology data (Kaiser et al., 2018).

The multiscale alterations to the human IVD, endplates and motion segment observed in the present study indicate the importance of studying IVD degeneration as a whole organ. Performing multiple assays on every sample is of additional importance, as human degeneration is highly heterogenous. In doing so, we were able to identify correlations between measured variables. Although a linear trend in bone remodeling with increasing Pfirrmann grade was not evident, these µCT parameters were significantly correlated with NP T2 and disc height. This is interesting, as bony changes, specifically those occurring above the CEP, can have negative impacts on disc nutrition (Ashinsky et al., 2020), particularly in the NP. Additionally, (Benneker et al., 2005b) report a link between morphologic disc degeneration and bony metrics, where Thompson grade significantly correlated with Modic changes, osteophytes and rim calcification. However, studies have also suggested that other factors, such as reduced disc stresses or cartilage endplate degeneration, correlate with disc degeneration to a greater extent than alterations in BEP porosity and permeability (Rodriguez et al., 2011; Zehra et al., 2015). Additional studies are needed to corroborate correlations between NP structure and BEP changes to confirm potential cross‐talk between these two tissues during degeneration.

Another informative correlation determined from the present study was between the micromechanical AFM measurements (E ind CEP, AF, AF‐EP) and whole motion segment macro‐mechanical properties (toe and linear modulus). Other groups have previously evaluated NP (Iatridis et al., 1996), AF (Iatridis et al., 1999), endplate (Berg‐johansen et al., 2018), and motion segment (Cortes et al., 2014; Pollintine et al., 2010) mechanics in isolated studies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report a relationship between micro and macroscale mechanic perturbations in IVD tissues with degeneration. It will be of critical importance in future studies to parse out the time course of these functional changes to further our understanding of the pathophysiology of degeneration, and to aid in the early detection of disease. This may be facilitated by the use of techniques such as MR elastography for the in vivo non‐invasive assessment of regional tissues (Beauchemin et al., 2018; Cortes et al., 2014; Walter et al., 2017). Additionally, recent applications of high‐resolution imaging techniques, such as ultrashort echo time MRI (Berg‐Johansen et al., 2017b; Fields et al., 2015), have shown great promise in evaluating degenerative changes to the cartilage endplate and may also be of potential clinical interest given the changes we observed at this location.

As a final point, we found that NP collagen content was significantly correlated with all of the macroscale compressive mechanical properties. Previous studies have shown reduced type II collagen crosslinking in the NP; however, new collagen molecules are also synthesized throughout the disc in early degeneration, possibly as an adaptive remodeling response (Antoniou et al., 1996; Duance et al., 1998). These biochemical changes in the NP region specifically may result in altered internal stress and strain patterns in the disc, contributing to widespread motion segment mechanical deficiencies. Furthermore, previous work has also shown that NP GAG content is correlated with axial and dynamic motion segment mechanics in an animal model (Boxberger et al., 2008, 2009). Additionally, overall GAG loss across NP and AF tissues during human degeneration has been shown to correlate with intradiscal pressures (Zehra et al., 2019). Although we did not detect significant correlations between NP GAG content and macroscale mechanical properties, we did observe a reduction in GAG content between the mild and moderately degenerative discs, followed by an increase in GAG content in the most severely degenerative grade 5 discs. These findings support further investigations of the interplay between matrix composition and mechanics as mechanisms in the degenerative cascade.

Despite the potential impact of these findings, this study has several limitations. First, it is quite clear that human IVD degeneration is heterogeneous, varying between patients and across levels. Although the 30 motion segments analyzed in this study were treated as independent samples, there is inevitable donor bias, as the samples acquired came from seven individuals. Our sample pool was also biased with respect to age and gender, as all donors ranged from 60 to 90 years old, with five males and two females. Further, although the dataset has a wide range of degenerative grades (2 through 5), we did not have access to spines with Pfirrmann grade 1 discs, or spines from younger donors, which would have served as healthy controls for comparison. An increase in sample size and donor age range will enable future work to precisely quantify the trajectory of the multiscale alterations we observed during degeneration in this donor set. In this study, we did not quantify water content of the tissue and were therefore not able to normalize biochemical content to sample dry weight. Thus, the values obtained for collagen and GAG content may be influenced by alterations in water content. This, in addition to alterations in GAG and collagen content in the disc occurring with age, could explain the lack of robust correlations between biochemical content and other outcomes. As we have begun to appreciate IVD degeneration as a whole organ condition, future work assessing surrounding spinal structures, including the facet joints will also be of critical value to the field.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Robert L. Mauck is a co‐editor of JOR Spine.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

BGA, SEG, RLM, and HES were involved in drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published. BGA and SEG had full access to all of the data in this study, and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Study conception and design: BGA, SEG, RLM. Acquisition of data: BGA, SEG, CW, EDB. Analysis and interpretation of data: All authors.

Supporting information

Figure S1

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the NIH (F30AG060670), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the NIH (F32‐AR‐072478), the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (NIH, P30 AR069619), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (IK1 RX002445, IK2 RX001476, I01 RX001321, I01 RX002274, IK6 RX003416, IK2 RX003118).

Ashinsky B.G., Gullbrand S.E., Wang C., Bonnevie E.D., Han L., Mauck R.L., Smith H.E.. Degeneration alters structure‐function relationships at multiple length‐scales and across interfaces in human intervertebral discs. J. Anat. 2021;238:986–998. 10.1111/joa.13349

Beth G. Ashinsky and Sarah E. Gullbrand contributed equally to this work and are listed alphabetically.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- Adams, M.A. , Freeman, B.J. , Morrison, H.P. , Nelson, I.W. & Dolan, P. (2000) Mechanical initiation of intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine, 25, 1625–1636. 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, J. , Steffen, T. , Nelson, F. , Winterbottom, N. , Hollander, A.P. , Poole, R.A. et al. (1996) The human lumbar intervertebral disc: evidence for changes in the biosynthesis and denaturation of the extracellular matrix with growth, maturation, ageing, and degeneration. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 98, 996–1003. 10.1172/JCI118884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashinsky, B.G. , Bonnevie, E.D. , Mandalapu, S.A. , Pickup, S. , Wang, C. , Han, L. et al. (2020) Intervertebral disc degeneration is associated with aberrant endplate remodeling and reduced small molecule transport. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 35(8), 1572–1581. 10.1002/jbmr.4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin, P.F. , Bayly, P.V. , Garbow, J.R. , Schmidt, J.L.S. , Okamoto, R.J. , Chériet, F. et al. (2018) Frequency‐dependent shear properties of annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus by magnetic resonance elastography. NMR in Biomedicine, 31, e3918. 10.1002/nbm.3918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benneker, L.M. , Heini, P.F. , Alini, M. , Anderson, S.E. & Ito, K. (2005a) 2004 Young Investigator Award Winner: vertebral endplate marrow contact channel occlusions and intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine, 30, 167–173. 10.1097/01.brs.0000150833.93248.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benneker, L.M. , Heini, P.F. , Anderson, S.E. , Alini, M. & Ito, K. (2005b) Correlation of radiographic and MRI parameters to morphological and biochemical assessment of intervertebral disc degeneration. European Spine Journal, 14, 27–35. 10.1007/s00586-004-0759-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg‐Johansen, B. , Fields, A.J. , Liebenberg, E.C. , Li, A. & Lotz, J.C. (2017a) Structure‐function relationships at the human spinal disc‐vertebra interface. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 10, 10. 10.1002/jor.23627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg‐Johansen, B. , Han, M. , Fields, A.J. , Liebenberg, E.C. , Lim, B.J. , Larson, P.E. et al. (2017b) Cartilage endplate thickness variation measured by ultrashort echo‐time MRI is associated with adjacent disc degeneration. Spine, 43(10), E592–E600. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg‐Johansen, B. , Jain, D. , Liebenberg, E.C. , Fields, A.J. , Link, T.M. , O’Neill, C.W. et al.(2018) Tidemark avulsions are a predominant form of endplate irregularity. Spine, 43, 1095–1101. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxberger, J.I. , Auerbach, J.D. , Sen, S. & Elliott, D.M. (2008) An in vivo model of reduced nucleus pulposus glycosaminoglycan content in the rat lumbar intervertebral disc. Spine, 33, 146–154. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816054f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxberger, J.I. , Orlansky, A.S. , Sen, S. & Elliott, D.M. (2009) Reduced nucleus pulposus glycosaminoglycan content alters intervertebral disc dynamic viscoelastic mechanics. Journal of Biomechanics, 42, 1941–1946. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinckmann, P. & Horst, M. (1985) The influence of vertebral body fracture, intradiscal injection, and partial discectomy on the radial bulge and height of human lumbar discs. Spine, 10, 138–145. 10.1097/00007632-198503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter, J.A. (1995) Aging and degeneration of the human intervertebral disc. Spine, 20, 1307–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campana, S. , Charpail, E. , de Guise, J.A. , Rillardon, L. , Skalli, W. & Mitton, D. (2011) Relationships between viscoelastic properties of lumbar intervertebral disc and degeneration grade assessed by MRI. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, 4, 593–599. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, J.J. , Hiltner, A. & Baer, E. (1989) Hierarchical structure of the intervertebral disc. Connective Tissue Research, 23, 75–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC MMWR . (2009). Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults—United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 58, 421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, D.H. , Magland, J.F. , Wright, A.C. & Elliott, D.M. (2014) The shear modulus of the nucleus pulposus measured using magnetic resonance elastography: a potential biomarker for intervertebral disc degeneration. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 72, 211–219. 10.1002/mrm.24895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Schepper, E.I.T. , Damen, J. , van Meurs, J.B.J. , Ginai, A.Z. , Popham, M. , Hofman, A. et al. (2010) The association between lumbar disc degeneration and low back pain. Spine, 35, 531–536. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181aa5b33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadis, E.K. , Horkay, F. , Maresca, J. , Kachar, B. & Chadwick, R.S. (2002) Determination of elastic moduli of thin layers of soft material using the atomic force microscope. Biophysical Journal, 82, 2798–2810. 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75620-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, P. , Luo, J. , Pollintine, P. , Landham, P.R. , Stefanakis, M. & Adams, M.A. (2013) Intervertebral disc decompression following endplate damage: implications for disc degeneration depend on spinal level and age. Spine, 38, 1473–1481. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318290f3cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duance, V.C. , Crean, J.K. , Sims, T.J. , Avery, N. , Smith, S. , Menage, J. et al. (1998) Changes in collagen cross‐linking in degenerative disc disease and scoliosis. Spine, 23, 2545–2551. 10.1097/00007632-199812010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudli, S. , Sing, D.C. , Hu, S.S. , Berven, S.H. , Burch, S. , Deviren, V. et al. (2017) ISSLS PRIZE IN BASIC SCIENCE 2017: intervertebral disc/bone marrow cross‐talk with Modic changes. European Spine Journal, 26, 1362–1373. 10.1007/s00586-017-4955-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farndale, R.W. , Sayers, C.A. & Barrett, A.J. (1982) A direct spectrophotometric microassay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage cultures. Connective Tissue Research, 9, 247–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields, A.J. , Ballatori, A. , Liebenberg, E.C. & Lotz, J.C. (2018) Contribution of the endplates to disc degeneration. Current Molecular Biology Reports, 4, 151–160. 10.1007/s40610-018-0105-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields, A.J. , Han, M. , Krug, R. & Lotz, J.C. (2015) Cartilaginous end plates: Quantitative MR imaging with very short echo times‐orientation dependence and correlation with biochemical composition. Radiology, 274, 482–489. 10.1148/radiol.14141082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields, A.J. , Liebenberg, E.C. & Lotz, J.C. (2014) Innervation of pathologies in the lumbar vertebral end plate and intervertebral disc. Spine Journal, 14, 513–521. 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold, G.E. , Han, E. , Stainsby, J. , Wright, G. , Brittain, J. & Beaulieu, C. (2004) Musculoskeletal MRI at 3.0 T: relaxation times and image contrast. American Journal of Roentgenology, 183, 343–351. 10.2214/ajr.183.2.1830343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.P. , Epure, L.M. , Bokhari, R. , Roughley, P. , Antoniou, J. & Mwale, F. (2016) Human cartilaginous endplate degeneration is induced by calcium and the extracellular calcium‐sensing receptor in the intervertebral disc. European Cells and Materials, 32, 137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullbrand, S.E. , Ashinsky, B.G. , Bonnevie, E.D. , Kim, D.H. , Engiles, J.B. , Smith, L.J. et al. (2018) Long‐term mechanical function and integration of an implanted tissue‐engineered intervertebral disc. Science Translational Medicine, 10(468), eaau0670. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullbrand, S.E. , Ashinsky, B.G. , Martin, J.T. , Pickup, S. , Smith, L.J. , Mauck, R.L. et al. (2016) Correlations between quantitative T 2 and T 1 ρ MRI, mechanical properties and biochemical composition in a rabbit lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration model. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 34, 1382–1388. 10.1002/jor.23269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haefeli, M. , Kalberer, F. , Saegesser, D. , Nerlich, A.G. , Boos, N. & Paesold, G. (2006) The course of macroscopic degeneration in the human lumbar intervertebral disc. Spine, 31, 1522–1531. 10.1097/01.brs.0000222032.52336.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, R.C. , Ball, J. & Benn, R.T. (1976) Vertebral end‐plate lesions (Schmorl’s nodes) in the dorsolumbar spine. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 35, 127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.‐C. , Urban, J.P.G. & Luk, K.D.K. (2014) Intervertebral disc regeneration: do nutrients lead the way? Nature reviews. Rheumatology, 10, 561–566. 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukins, D.W. (1992) A simple model for the function of proteoglycans and collagen in the response to compression of the intervertebral disc. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 249, 281–285. 10.1098/rspb.1992.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humzah, M.D. & Soames, R.W. (1988) Human intervertebral disc: structure and function. The Anatomical Record, 220, 337–356. 10.1002/ar.1092200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iatridis, J.C. , Kumar, S. , Foster, R.J. , Weidenbaum, M. & Mow, V.C. (1999) Shear mechanical properties of human lumbar annulus fibrosus. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 17, 732–737. 10.1002/jor.1100170517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iatridis, J.C. , Weidenbaum, M. , Setton, L.A. & Mow, V.C. (1996) Is the nucleus pulposus a solid or a fluid? Mechanical behaviors of the nucleus pulposus of the human intervertebral disc. Spine, 21, 1174–1184. 10.1097/00007632-199605150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, H. (1976) Three‐dimensional architecture of lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine, 6, 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, H. , McNally, D.S. , Urban, J.P. & Hall, A.C. (1996) Effects of hydrostatic pressure on matrix synthesis in different regions of the intervertebral disk. Journal of Applied Physiology, 80, 839–846. 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.3.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, J. , Allaire, B. , Fein, P.M. , Lu, D. , Jarraya, M. , Guermazi, A. et al. (2018) Correspondence between bone mineral density and intervertebral disc degeneration across age and sex. Archives of Osteoporosis, 13, 123. 10.1007/s11657-018-0538-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel, R. , Roberts, S. & Urban, J.P.G. (2008) Tissue engineering and the intervertebral disc: the challenges. European Spine Journal, 17(Suppl 4), 480–491. 10.1007/s00586-008-0746-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto, T. & Kawamoto, K. (2014) Preparation of thin frozen sections from nonfixed and undecalcified hard tissues using Kawamot’s film method (2012). Methods in Molecular Biology, 1130, 149–164. 10.1007/978-1-62703-989-5_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. , Qu, F. , Han, B. , Wang, C. , Li, H. , Mauck, R.L. et al. (2017) Micromechanical anisotropy and heterogeneity of the meniscus extracellular matrix. Acta Biomaterialia, 54, 356–366. 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.T. , Collins, C.M. , Mauck, R.L. , Ikuta, K. , Elliott, D.M. , Zhang, Y. et al. (2015) Population average T2 MRI maps reveal quantitative regional transformations in the degenerating rabbit intervertebral disc that vary by lumbar level. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 33, 140–148. 10.1002/jor.22737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.T. , Gorth, D.J. , Beattie, E.E. , Harfe, B.D. , Smith, L.J. & Elliott, D.M. (2013) Needle puncture injury causes acute and long‐term mechanical deficiency in a mouse model of intervertebral disc degeneration. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 31, 1276–1282. 10.1002/jor.22355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.T. , Milby, A.H. , Chiaro, J.A. , Kim, D.H. , Hebela, N.M. , Smith, L.J. et al. (2014) Translation of an engineered nanofibrous disc‐like angle‐ply structure for intervertebral disc replacement in a small animal model. Acta Biomaterialia, 10, 2473–2481. 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok, F.P.S. , Samartzis, D. , Karppinen, J. , Luk, K.D.K. , Fong, D.Y.T. & Cheung, K.M.C. (2010) ISSLS prize winner: prevalence, determinants, and association of Schmorl nodes of the lumbar spine with disc degeneration: a population‐based study of 2449 individuals. Spine, 35, 1944–1952. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d534f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.J. (2000) The vertebral end‐plate: what do we know? European Spine Journal, 9, 92–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachemson, A. , Lewin, T. , Maroudas, A. & Freeman, M.A. (1970) In vitro diffusion of dye through the end‐plates and the annulus fibrosus of human lumbar inter‐vertebral discs. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica, 41, 589–607. 10.3109/17453677008991550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, G.D. , Jacobs, N.T. , Sen, S. , Vresilovic, E.J. & Elliott, D.M. (2011) Axial creep loading and unloaded recovery of the human intervertebral disc and the effect of degeneration. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, 4, 933–942. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfirrmann, C.W. , Metzdorf, A. , Zanetti, M. , Hodler, J. & Boos, N. (2001) Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine, 26, 1873–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollintine, P. , van Tunen, M.S.L.M. , Luo, J. , Brown, M.D. , Dolan, P. & Adams, M.A. (2010) Time‐dependent compressive deformation of the ageing spine: relevance to spinal stenosis. Spine, 35, 386–394. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b0ef26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranu, H.S. (1993) Multipoint determination of pressure‐volume curves in human intervertebral discs. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 52, 142–146. 10.1136/ard.52.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, G.K. & Enwemeka, C.S. (1996) A simplified method for the analysis of hydroxyproline in biological tissues. Clinical Biochemistry, 29, 225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. , Menage, J. & Urban, J.P. (1989) Biochemical and structural properties of the cartilage end‐plate and its relation to the intervertebral disc. Spine, 14, 166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, A.G. , Rodriguez‐Soto, A.E. , Burghardt, A.J. , Berven, S. , Majumdar, S. & Lotz, J.C. (2012) Morphology of the human vertebral endplate. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 30, 280–287. 10.1002/jor.21513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, A.G. , Slichter, C.K. , Acosta, F.L. , Rodriguez‐Soto, A.E. , Burghardt, A.J. , Majumdar, S. et al. (2011) Human disc nucleus properties and vertebral endplate permeability. Spine, 36, 512–520. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f72b94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutges, J.P.H.J. , van der Jagt, O.P. , Oner, F.C. , Verbout, A.J. , Castelein, R.J.M. , Kummer, J.A. et al. (2011) Micro‐CT quantification of subchondral endplate changes in intervertebral disc degeneration. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 19, 89–95. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samartzis, D. , Mok, F.P.S. , Karppinen, J. , Fong, D.Y.T. , Luk, K.D.K. & Cheung, K.M.C. (2016) Classification of Schmorl’s nodes of the lumbar spine and association with disc degeneration: a large‐scale population‐based MRI study. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 24, 1753–1760. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, S.L. , Sylvia, M. & Fields, A.J. (2019) Effects of dynamic loading on solute transport through the human cartilage endplate. Journal of Biomechanics, 83, 273–279. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, G.D. , Markova, D.Z. , Koerner, J.D. , Rihn, J.A. , Hilibrand, A.S. , Vaccaro, A.R. et al. (2017) Are modic changes associated with intervertebral disc cytokine profiles? Spine Journal, 17, 129–134. 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanakis, M. , Luo, J. , Pollintine, P. , Dolan, P. & Adams, M.A. (2014) ISSLS Prize winner: mechanical influences in progressive intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine, 39, 1365–1372. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban, J.P.G. & Roberts, S. (2003) Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 5, 120–130. 10.1186/ar629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, M.H. & Anderson, D.G. (2004) Molecular basis of intervertebral disc degeneration. The Spine Journal, 4, 158S–166S. 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, A.J.L. & Lotz, J.C. (2004) Biological response of the intervertebral disc to dynamic loading. Journal of Biomechanics, 37, 329–337. 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter, B.A. , Mageswaran, P. , Mo, X. , Boulter, D.J. , Mashaly, H. , Nguyen, X.V. et al. (2017) MR elastography‐derived stiffness: a biomarker for intervertebral disc degeneration. Radiology, 285, 167–175. 10.1148/radiol.2017162287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, H.‐J. , Rohlmann, F. , Neidlinger‐Wilke, C. , Werner, K. , Claes, L. & Kettler, A. (2006) Validity and interobserver agreement of a new radiographic grading system for intervertebral disc degeneration: Part I. Lumbar spine. European Spine Journal, 15, 720–730. 10.1007/s00586-005-1029-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J. , Sampson, S.L. , Bell‐Briones, H. , Ouyang, A. , Lazar, A.A. , Lotz, J.C. et al. (2019) Nutrient supply and nucleus pulposus cell function: effects of the transport properties of the cartilage endplate and potential implications for intradiscal biologic therapy. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 27(6), 956–964. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, M.A. , Hong, S.‐J. , Kang, C.H. , Ahn, K.‐S. & Kim, B.H. (2016) T1rho and T2 mapping of lumbar intervertebral disc: Correlation with degeneration and morphologic changes in different disc regions. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 34, 932–939. 10.1016/j.mri.2016.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehra, U. , Noel‐Barker, N. , Marshall, J. , Adams, M.A. & Dolan, P. (2019) Associations between intervertebral disc degeneration grading schemes and measures of disc function. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 37, 1946–1955. 10.1002/jor.24326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehra, U. , Robson‐Brown, K. , Adams, M.A. & Dolan, P. (2015) Porosity and thickness of the vertebral endplate depend on local mechanical loading. Spine, 40, 1173–1180. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.