Abstract

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) has been described in myeloproliferative disorders; monoclonal plasma cell disorder such as polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin changes syndrome; and plasma cell dyscrasias such as multiple myeloma and amyloidosis. We describe 4 cases of PH likely due to pulmonary vascular involvement and myocardial deposition from light chain deposition disease, amyloidosis, and multiple myeloma. On the basis of our clinical experience and literature review, we propose screening for plasma cell dyscrasia in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, unexplained PH, and hematological abnormalities. We also recommend inclusion of cardiopulmonary screening in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AL, amyloid light chain; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; BMB, bone marrow biopsy; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CT, computed tomography; FLC, free light chain; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ILD, interstitial lung disease; LCDD, light chain deposition disease; LC-MGUS, light chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; LV, left ventricular; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM, multiple myeloma; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PH, pulmonary hypertension; RA, right atrial; RHC, right heart catheterization; RV, right ventricle/ventricular; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; WHO, World Health Organization

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is associated with myeloproliferative disorders, polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin changes syndrome, multiple myeloma (MM), plasma cell leukemia, and amyloidosis.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 The pathophysiology of PH in plasma cell dyscrasias could be due to pulmonary vascular deposition of amyloid fibrils or light chains, pulmonary parenchymal involvement (World Health Organization [WHO] group III), or due to left-sided heart disease from infiltrative cardiomyopathy (WHO group II).7 Reports of the reversibility of PH with the treatment of MM and polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin changes syndrome have been reported.1,8

We report 4 cases of PH associated with amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis and MM. The study was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board, and a waiver of informed consent was obtained. The aim of this case series is 2-fold. First, we propose the incorporation of cardiopulmonary screening in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). Conversely, patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction or unexplained PH should be screened for plasma cell dyscrasia. Second, we propose the term “monoclonal gammopathy of cardiac or pulmonary significance” be coined to describe the cardiac and pulmonary manifestations for early initiation of treatment before end-organ function ensues. The term “monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance” was coined by the International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group to describe renal dysfunction due to the deposition of monoclonal proteins in the kidneys. Despite the lack of criteria for the diagnosis of MM in patients with MGUS, recommendations are to treat the plasma cell disorder with monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance.

Case Reports

Case 1

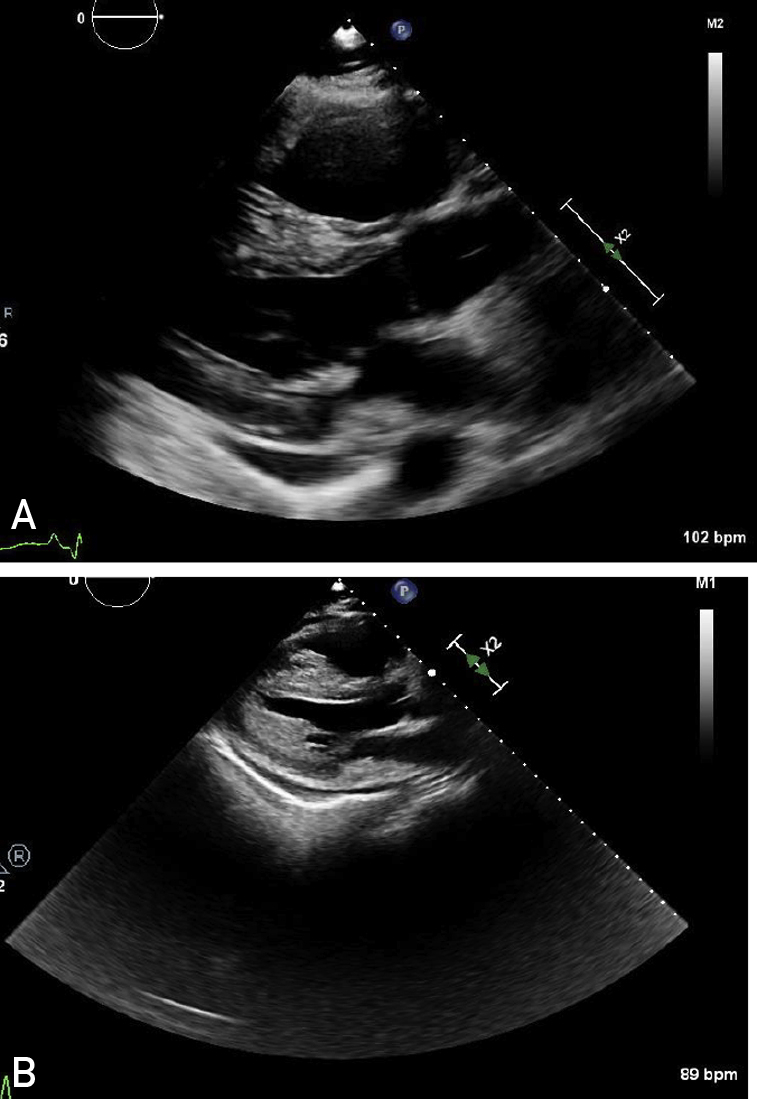

A 43-year-old Black man with no medical history was referred for the management of severe PH. He developed exertional dyspnea 3 months before presentation. Right heart catheterization (RHC) details are summarized in Table 1, indicating severely elevated mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) and elevated right atrial (RA) pressures but normal cardiac index. Laboratory testing revealed normal renal function, elevated total bilirubin level, and elevated brain natriuretic peptide level. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed dilated right ventricle (RV) with severely depressed RV systolic function, normal left ventricular (LV) systolic function, normal LV wall thickness, and moderate-sized pericardial effusion (Figure 1A). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest did not reveal interstitial lung disease (ILD) or pulmonary embolism. Connective tissue disease work-up was unrevealing. Infectious serologies for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis were negative. Genetic testing did not reveal pathogenic sequence variation. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed during the initial diagnosis of PH did not find evidence of infiltrative disease. Treatment with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor and endothelin receptor antagonist for idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension was initiated with improvement in functional capacity and hemodynamics. One year after diagnosis, there was evidence of worsening PAPs and RV systolic dysfunction by invasive testing even though the patient denied worsening functional capacity. Inhaled treprostinil was initiated. Repeat TTE revealed a mild increase in LV wall thickness, preserved LV systolic function, indeterminate LV diastolic function, severely depressed RV systolic function, and moderate-sized pericardial effusion (Figure 1B). Because of suspicion of infiltrative disease, serum free light chain (FLC) testing was ordered that found an elevated kappa FLC (κ FLC) of 184.6 mg/L and a normal lambda FLC (λ FLC) of 23.8, with an abnormal FLC ratio of 7.76 (normal range, 0.26-1.65). Serum monoclonal-spike was 1.81 g/dL. A bone marrow biopsy (BMB) revealed monoclonal plasma cells more than 20%. Congo red staining of BMB specimens was negative. The patient developed worsening renal dysfunction and nephrotic range proteinuria (Table 1, case 1). There was no laboratory evidence of anemia, hypercalcemia, or osteolytic lesions. A renal biopsy revealed global and segmental glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy, with immunofluorescence staining positive for kappa light chain and Congo red staining negative for amyloid. Diagnosis of light chain (IgG κ) MM with light chain deposition disease (LCDD) involving kidneys, lungs, and heart was made. Treatment was initiated with bortezomib. He developed end-stage renal disease and began receiving hemodialysis. The patient transferred his care to another facility for the management of MM.

Table 1.

Summary of Clinical and Laboratory Data for the Described Clinical Casesa

| Characteristic | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 46 | 75 | 71 | 54 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Female |

| Race | Black | White | White | Black |

| Onset of symptoms before the diagnosis of plasma cell dyscrasia | 2 y (Dyspnea) Pulmonary artery hypertension |

2 y (Dyspnea) Pulmonary artery hypertension |

1 y (Dyspnea) Pulmonary artery hypertension |

4 mo (Dyspnea, lower extremity edema) Restrictive cardiomyopathy Pulmonary artery hypertension |

| Diagnosis of MGUS | No | No | Yes | No |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| BNP level (<100 pg/mL) | 1433 | 979 | 1125 | 805 |

| Troponin I level (<0.02 ng/mL) | 0.05 | <0.02 | 0.085 | 0.074 |

| NT-proBNP level (<300 pg/mL) | NA | NA | 23,899 | NA |

| Troponin T level (<0.01 ng/mL) | <0.01 | NA | 0.08 | NA |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dL) | 13 | 11.7 | 13.3 | 10.6 |

| Calcium level (mg/dL) | 9.7 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 9.6 |

| Serum creatinine level (mg/dL) | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 0.8 |

| Serum monoclonal-spike | Present (1.81 g/dL) | Present (4.1 g/dL) | Absent | Present (2 g/dL) |

| Kappa light chain (mg/L) | 184 | 2266 | 19.7 | 1.5 |

| Lambda light chain (mg/L) | 23.8 | 3.1 | 948 | 519 |

| Serum free light chain ratio | 7.76 | 731.23 | 0.02 | 0.002 |

| Urine monoclonal-spike | Present | Present | Present | Present |

| Urine protein level (24 h) | 10 g | 937 mg | 248 mg | NA |

| Immunoglobulins | ||||

| IgA (66-436) | 150 | 22 | 129 | 24 |

| IgG (694-1618) | 2693 | 5326 | 647 | 3067 |

| IgM (45-281) | 72 | <10 | 29 | <25 |

| CRAB criteria | Absent | Present Renal insufficiency |

Present Renal insufficiency (eGFR <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2) |

Present Anemia |

| Electrocardiography | Normal sinus rhythm RVH |

Atrial fibrillation Right bundle branch block |

Normal sinus rhythm (82 beats/min) Low QRS voltage Right axis deviation Poor R-wave progression |

Normal sinus rhythm Poor R-wave progression |

| 2D echocardiography | Normal LV systolic function Moderate concentric LVH RV dilated and severely depressed function |

Normal LV systolic function and wall thickness RV dilated and function severely depressed |

Moderate concentric LVH LVEF 35%-40% Small pericardial effusion |

Mild concentric LVH LVEF >55% RVSP 72 mm Hg Normal RV systolic function |

| Right heart catheterization | ||||

| RA pressure (mm Hg) | 19 | 21 | 20 | 11 |

| PA pressure (systolic/diastolic/mean) | 87/30/50 | 88/41/57 | 79/34/50 | 61/25/40 |

| PCWP (mm Hg) | 10 | 16 | 26 | 18 |

| Fick cardiac index (L/min per m2) | 2.46 | 1.43 | 1.8 | 2.16 |

| PVR (WU) | 7.6 Precapillary |

14 Combined pre- and postcapillary |

5.7 Combined pre- and postcapillary |

6 Combined pre- and postcapillary |

| Bone marrow biopsy | ||||

| Plasma cells | 20% monoclonal plasma cells | 30% monoclonal plasma cells | 10%-15% monoclonal plasma cells | 90% plasma cells |

| Congo red stain | Negative | Negative | Negative | Not performed |

| Endomyocardial biopsy | Not done | Not done | Congo red–positive deposits Mass spectrometry: AL (lambda) type |

Not performed |

| Renal biopsy | Global and segmental glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy Immunofluorescence staining positive for kappa LC; Congo red staining negative for amyloid | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment | Bortezomib | Bortezomib | Bortezomib | Induction chemotherapy (RVD) Autologous bone marrow transplant |

2D = 2-dimensional; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; CRAB = criteria hypercalcemia (>11.5 mg/dL), renal insufficiency (serum creatinine level > 2 mg/dL or eGFR < 40 mL/min per 1.73 m2, anemia (hemoglobin level < 10 g/dL), bony lesion >1 site osteolytic lesions on skeletal survey; D = diastolic; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; LC = light chain; LV = left ventricular; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy; M = mean; MGUS = monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; NA = not available; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro–hormone brain natriuretic peptide; PA = pulmonary artery; PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; RA = right atrium; RV = right ventricular; RVD = Revlimid + Velcade + dexamethasone; RVH = right ventricular hypertrophy; RVSP = right ventricular systolic pressure; S = systolic; WU = wood unit.

Figure 1.

A, A 2-dimensional echocardiogram revealing right ventricular dilation and pericardial effusion. B, A year later, a 2-dimensional echocardiogram revealing severe left ventricular hypertrophy suggestive of infiltrative disease.

Case 2

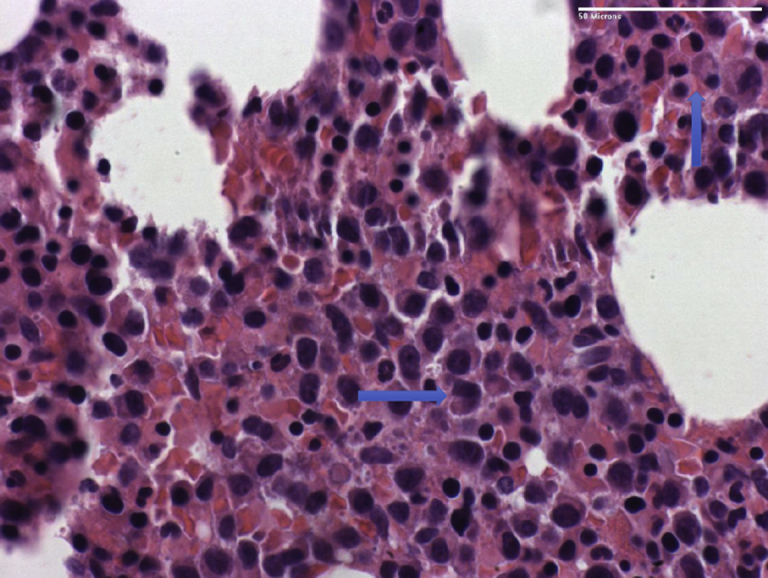

A 75-year-old White man with a medical history of hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage IV, and atrial fibrillation was referred to our PH clinic. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed normal LV wall thickness and systolic function, an elevated estimated RV systolic pressure of 90 mm Hg, severely dilated RV with depressed systolic function, and a small pericardial effusion. Right heart catheterization revealed severely elevated mean PAP, RA pressure, and low Fick cardiac index. because of pancytopenia and CKD, serum FLC testing was ordered. Serum FLC testing found an elevated κ FLC of 2266 mg/L and an λ FLC of 3.1 mg/L, with an elevated FLC ratio of 731. Serum monoclonal-spike was 4.10 g/dL (Table 1, case 2). Twenty-four–hour urine protein testing revealed approximately 1 g of protein. A bone marrow biopsy revealed monoclonal plasma cells with kappa light chain restriction more than 39% (Figure 2). Congo red staining was negative for amyloid. A CT scan of the chest did not find evidence of ILD. Connective tissue disease work-up and infectious serologies for HIV and hepatitis were negative. A ventilation/perfusion scan was not performed to rule out chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease. Treatment with bortezomib was initiated for IgG κ light chain MM with LCDD involving kidneys and pulmonary vasculature. The patient also received dexamethasone because of suspicion of renal myeloma involvement. The patient developed acute on chronic renal failure, but because of family and patient’s wishes, hemodialysis was not initiated. Supportive care measures were instituted, and the patient died in hospice.

Figure 2.

Sections reveal a hypercellular marrow containing a large number of plasma cells (arrows).

Case 3

A 71-year-old White woman presented to our PH clinic for a second opinion on progressive exertional dyspnea over the last year. Family history was significant for MM in her mother. Her medical history included MGUS, hypertension, CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate, 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2), obstructive sleep apnea adhering to nightly continuous positive airway pressure, Hashimoto disease, and celiac disease.

Diagnosis of lambda light chain MGUS (LC-MGUS) was first made in 2010; at that time, BMB was unremarkable and a fat pad biopsy was negative for amyloid. Serum electropheresis was performed every 6 months with stable kappa/lambda light chain ratio (0.02-0.03). The skeletal survey found no lytic lesions, and renal function was normal.

Her initial work-up for exertional dyspnea included chest CT angiography, which revealed a small pulmonary embolism for which she began receiving anticoagulation therapy. Despite periodic diuresis for volume overload and participation in cardiac rehabilitation, her functional capacity declined. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed an estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 71 mm Hg, and she empirically began receiving riociguat by the referring physician.

Our assessment included an electrocardiogram that revealed sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement, and low voltage. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed thickened myocardium with infiltrative appearance, dilated RV, preserved LV ejection fraction, and grade III diastolic dysfunction.

She was admitted to our hospital for expedited evaluation after outpatient RHC that exhibited elevated RA pressures and PAPs with low cardiac output (Table 1, case 3). Cardiac MRI found biventricular systolic dysfunction with diffuse mid-wall late gadolinium enhancement involving nearly all the LV myocardium and biatrial enlargement. Serum FLC testing found a normal κ FLC of 20 mg/L and an elevated λ FLC of 948 mg/L, with a ratio of 0.02. Repeat BMB revealed plasma cell dyscrasia and mildly hypocellular marrow, and Congo red staining was negative for amyloid.

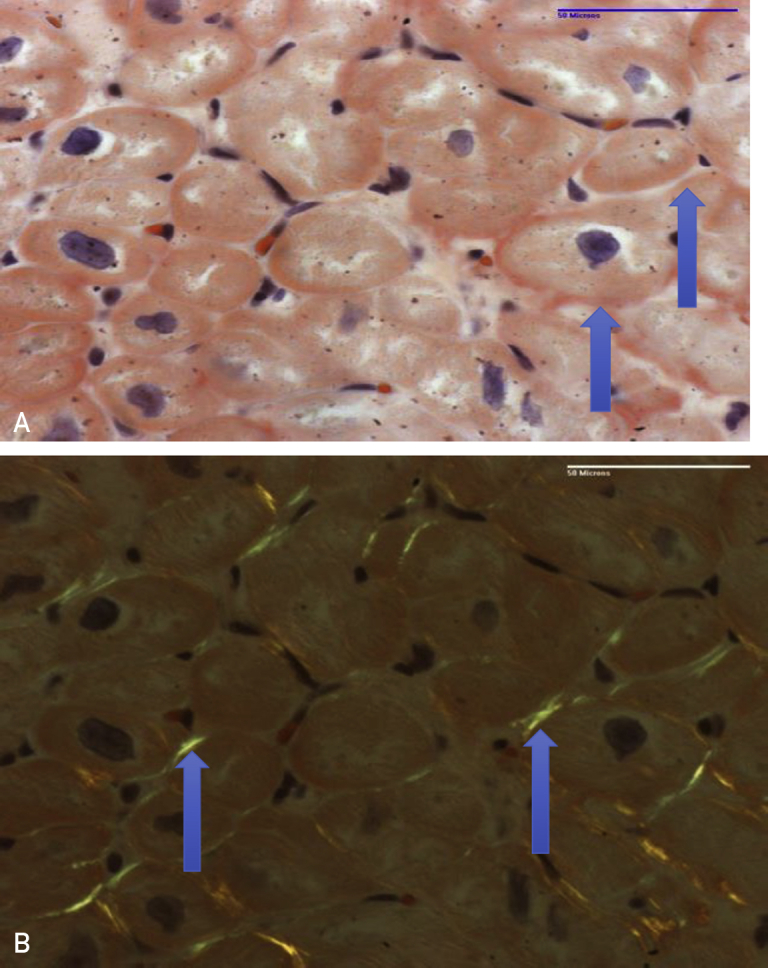

With a high suspicion of plasma cell dyscrasia leading to an infiltrative cardiomyopathy, she then underwent endomyocardial biopsy. Histopathological evaluation revealed mild interstitial widening, no significant fibrosis, and Congo red staining suggestive of amyloid (Figure 3). Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry confirmed AL (lambda)–type amyloid deposition. She was offered bortezomib, which, over the next few weeks, led to a 50% reduction in λ FLC. Unfortunately, despite this, her clinical condition deteriorated, and she was readmitted multiple times for heart failure and volume overload. She was ultimately discharged home with hospice 2 months after her initial diagnosis and died.

Figure 3.

A, Congo red–stained section reveals amorphous material consistent with amyloid in the myocardial interstitium (arrows). B, Under polarized light, apple green birefringence is seen (arrows).

Case 4

A 54-year-old Black woman with a history of hyperthyroidism received a diagnosis of IgG λ MM after routine blood work revealed elevated serum protein. The ventilation/perfusion scan revealed low probability for pulmonary embolism. There was no evidence of ILD on the CT scan of the chest. She underwent induction chemotherapy with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone. She had to begin receiving diuretics after the initiation of chemotherapy because of lower extremity edema. Transthoracic echocardiography performed before autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) revealed mild concentric LV hypertrophy with preserved ejection fraction, grade III diastolic dysfunction, an elevated estimated PAP of greater than 70 mm Hg, and normal RV systolic function (Table 1, case 4). Cardiac MRI did not find any evidence of infiltrative disease. She underwent ASCT 5 months after diagnosis. She had episodes of volume overload that were treated with an increased dose of diuretics. The patient began receiving phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor a few months after ASCT because of persistent PH on the basis of RHC (Table 1, case 4). Six years after ASCT, the patient still has good function capacity without any admissions for volume overload. Repeat TTE 5 years after ASCT still revealed persistent PH on the basis of the estimated RV systolic pressure of approximately 70 mm Hg without RV dysfunction.

Discussion

The 4 cases described here highlight the cardiopulmonary manifestations of plasma cell dyscrasia. Patients described in cases 1 and 2 received a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension before a clinical diagnosis of MM. The patient in case 3 had a history of MGUS for 10 years and PH diagnosis for a year preceding the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis. The fourth patient had received a diagnosis of PH after MM diagnosis. Work-up for secondary causes of PH, such as connective tissue disease, infectious diseases such as HIV and chronic hepatitis C, and ILD, was negative in all 4 patients. Three patients had cardiac, pulmonary, and renal involvement, but the clinical presentation was consistent with PH and RV failure.

The pulmonary manifestations of AL amyloidosis or LCDD include diffuse alveolar septal or localized nodular involvement. Pulmonary hypertension due to AL amyloidosis results from restrictive cardiomyopathy, pulmonary parenchymal involvement, or deposition of amyloid fibrils in the pulmonary vasculature. Pulmonary amyloidosis is seen predominantly owing to AL type, and the diagnosis was made postmortem in more than 90% of cases in an autopsy series. Pulmonary vascular involvement was seen in 97% of cases followed by alveolar septal deposition (78%).9 Deposition of amyloid fibrils in the media of small arteries, arterioles, and veins in multiple organs has been described.10 However, the pathogenicity of deposition of amyloid fibrils in the pulmonary vasculature is unclear. There have been reported cases of PH due to AL amyloidosis or MM and is a rare clinical presentation.3,4,7 Our case series add to the existing scarce literature on the pulmonary vascular involvement in plasma cell dyscrasias. The revised WHO classification of PH does not include monoclonal gammopathy, AL amyloidosis, or LCDD as a possible etiology for PH.2

Light chain MGUS accounts for 20% of cases of MM and 65% of AL amyloidosis.11 The prevalence of LC-MGUS is 0.8% in Whites 50 years or older, which is much lower than that of MGUS with heavy chain expression.12 Although the prevalence of MGUS in Blacks is 3 times that in Whites, the exact prevalence of LC-MGUS in Blacks is unknown.13 The progression of LC-MGUS to MM is only 0.3% per year. The evolution of LC-MGUS to MM, AL amyloidosis, or LCDD may depend on the genetics of plasma cell clone, amyloidogenesis, and tissue microenvironment.14 The plasma cell clone secreting light chains may have low malignant potential but can be of clinical significance, with damage to kidneys, bone, skin, and peripheral nervous system.15 The most common organs involved in AL amyloidosis is the heart (71%), kidney (58%), and peripheral nervous system (23%).16 Cardiac involvement portends a poor prognosis with a median survival of 6 months but often diagnosis is delayed.17 Ten to fifteen percent of patients with MM and 9% of patients with MGUS develop AL amyloidosis.18 Patients with LCDD may have coexistent MM (10%-30%) and AL amyloidosis (17%).19 Light chain deposition disease with cardiac involvement (33%) has overall poor survival and is related to increased transplant-related mortality. Only 18% of patients had LV ejection fraction less than 50%, and most frequent manifestations are atrial arrhythmias, sinus bradycardia, and diastolic dysfunction. Light chain deposition disease with coexisting amyloid is commonly associated with increased production of lambda light chains (40%), whereas LCDD is predominantly kappa restricted.

The transformation of LC-MGUS to AL amyloidosis or LCDD may occur over a period during which time occult damage to kidneys, heart, lung, and peripheral nervous system may occur. Proposed high-risk criteria for progression include involved/uninvolved FLC ratio less than 0.125 or greater than 8.0 with progression rates of more than 8% per year.20 The risk of progression is 3 times higher with an abnormal FLC ratio irrespective of the type and size of serum monoclonal M protein. Presence of combined abnormal serum FLC ratio, non-IgG MGUS, and elevated M protein level (>15 g/L) predicts the highest risk of progression (58% at 20 years).21

We propose that LC-MGUS screening should include cardiopulmonary testing. We recommend screening for cardiac involvement with routine biomarkers such as N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, brain natriuretic peptide, cardiac troponin I or T, and electrocardiography followed by TTE if serum biomarkers are abnormal. Detailed TTE evaluation of LV morphology, LV systolic and diastolic function, RV systolic function, and estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure should be performed. Diagnosis of pulmonary involvement can be challenging because of the nonspecific radiological findings. A transbronchial or open lung biopsy may be required for confirmation of pulmonary amyloidosis. Thoracentesis with pleural fluid FLC assay can be performed for patients with recurrent pleural effusions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Diagnostic Criteria for LC-MGUS

| Serum free light chain ratio (<0.26 or >1.65) |

| Elevated monoclonal kappa or lambda light chains |

| Monoclonal bone marrow plasma cells <10% |

| Urinary monoclonal protein level < 500 mg/24 h |

| Absence of immunoglobulin heavy chain expression on immunofixation |

| No evidence of end-organ damage (hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, and bone lesions) |

| Proposed organ inclusion for screening with noninvasive testing: |

| Heart (restrictive cardiomyopathy, HFpEF, and conduction system abnormalities)—ECG; cardiac biomarkers—NT-proBNP or BNP and cardiac troponin T or I, 2D echocardiography with speckle tracking |

| Pulmonary (vascular—PH) (parenchymal—nodular, diffuse alveolar septal, intrathoracic lymphadenopathy, laryngeal, and tracheobronchial) |

| Chest radiography. CT scan of the chest if indicated or suspicion high (dyspnea, cough, or abnormal chest radiography). Bronchoscopy with biopsy. Thoracentesis and pleural fluid free light chain assay |

2D = 2-dimensional; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; CT = omputed tomography; ECG = electrocardiogram; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; LC-MGUS = light chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; PH = pulmonary hypertension.

Conclusion

We describe our experience of 2 cases of IgG κ MM, 1 case of IgG λ MM, and 1 case of AL amyloidosis as etiologies for PH. Early diagnosis and timely treatment of plasma cell dyscrasia will improve survival, and select patients may be candidates for solid organ transplantation. We recommend serum FLC testing in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction or unexplained PH. Incorporation of cardiopulmonary involvement to the “CRAB (Hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, Anemia and Lytic Bone lesions)” criteria may detect early disease and timely treatment to prolong survival. We propose the term “monoclonal gammopathy of cardiac or pulmonary significance” be coined to describe the cardiac and pulmonary manifestations for early initiation of treatment before end-organ function ensues.

Acknowledgments

Drs Rajapreyar and Joly contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Potential Competing Interests: The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Li J., Tian Z., Zheng H.Y. Pulmonary hypertension in POEMS syndrome. Haematologica. 2013;98(3):393–398. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.073031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simonneau G., Montani D., Celermajer D.S. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801913. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01913-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eder L., Zisman D., Wolf R., Bitterman H. Pulmonary hypertension and amyloidosis—an uncommon association: a case report and review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):416–419. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0052-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto H., Kurata A., Mizuno H. Pulmonary arterial hypertension due to pulmonary vascular amyloid deposition in a patient with multiple myeloma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(11):15391–15395. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnan U., Mark T.M., Niesvizky R., Sobol I. Pulmonary hypertension complicating multiple myeloma. Pulm Circ. 2015;5(3):590–597. doi: 10.1086/682430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamura S., Koyama A., Shiotani C. Successful bortezomib/dexamethasone induction therapy with lenalidomide in an elderly patient with primary plasma cell leukemia complicated by renal failure and pulmonary hypertension. Intern Med. 2014;53(11):1171–1175. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dingli D., Utz J.P., Gertz M.A. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with amyloidosis. Chest. 2001;120(5):1735–1738. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.5.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feyereisn W.L., Fenstad E.R., McCully R.B., Lacy M.Q. Severe reversible pulmonary hypertension in smoldering multiple myeloma: two cases and review of the literature. Pulm Circ. 2015;5(1):211–216. doi: 10.1086/679726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ussavarungsi K., Yi E.S., Maleszewski J.J. Clinical relevance of pulmonary amyloidosis: an analysis of 76 autopsy-derived cases. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(2):1602313. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02313-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahlin D.C. Primary amyloidosis, with report of six cases. Am J Pathol. 1949;25(1):105–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyle R.A., Gertz M.A., Witzig T.E. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21–33. doi: 10.4065/78.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dispenzieri A., Katzmann J.A., Kyle R.A. Prevalence and risk of progression of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1721–1728. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60482-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landgren O., Gridley G., Turesson I. Risk of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and subsequent multiple myeloma among African American and white veterans in the United States. Blood. 2006;107(3):904–906. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kastritis E., Dimopoulos M.A. Recent advances in the management of AL amyloidosis. Br J Haematol. 2016;172(2):170–186. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhodapkar M.V. MGUS to myeloma: a mysterious gammopathy of underexplored significance. Blood. 2016;128(23):2599–2606. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-692954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gertz M.A. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis diagnosis and treatment algorithm 2018. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8(5):44. doi: 10.1038/s41408-018-0080-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCausland K.L., White M.K., Guthrie S.D. Light chain (AL) amyloidosis: the journey to diagnosis. Patient. 2018;11(2):207–216. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0273-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grogan M., Dispenzieri A., Gertz M.A. Light-chain cardiac amyloidosis: strategies to promote early diagnosis and cardiac response. Heart. 2017;103(14):1065–1072. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohan M., Buros A., Mathur P. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors in multiple myeloma patients with light chain deposition disease. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(8):739–745. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dispenzieri A., Kyle R.A., Katzmann J.A. Immunoglobulin free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111(2):785–789. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajkumar S.V., Kyle R.A., Therneau T.M. Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2005;106(3):812–817. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]