Key Points

Question

Are incentives for alcohol abstinence an effective intervention for reducing alcohol use among American Indian and Alaska Native adults diagnosed with alcohol dependence?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 158 American Indian and Alaska Native adults with alcohol dependence, participants who received incentives for biologically confirmed alcohol abstinence were significantly more likely to submit alcohol-abstinent urine samples during the intervention period compared with participants who did not receive incentives for abstinence.

Meaning

The study’s results indicated that the provision of tangible incentives for alcohol abstinence, also known as contingency management, may be an effective strategy to help American Indian and Alaska Native adults diagnosed with alcohol dependence attain abstinence.

Abstract

Importance

Many American Indian and Alaska Native communities are disproportionately affected by problems with alcohol use and seek culturally appropriate and effective interventions for individuals with alcohol use disorders.

Objective

To determine whether a culturally tailored contingency management intervention, in which incentives were offered for biologically verified alcohol abstinence, resulted in increased abstinence among American Indian and Alaska Native adults. This study hypothesized that adults assigned to receive a contingency management intervention would have higher levels of alcohol abstinence than those assigned to the control condition.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multisite randomized clinical trial, the Helping Our Native Ongoing Recovery (HONOR) study, included a 1-month observation period before randomization and a 3-month intervention period. The study was conducted at 3 American Indian and Alaska Native health care organizations located in Alaska, the Pacific Northwest, and the Northern Plains from October 10, 2014, to September 2, 2019. Recruitment occurred between October 10, 2014, and February 20, 2019. Eligible participants were American Indian or Alaska Native adults who had 1 or more days of high alcohol-use episodes within the last 30 days and a current diagnosis of alcohol dependence. Data were analyzed from February 1 to April 29, 2020.

Interventions

Participants received treatment as usual and were randomized to either the contingency management group, in which individuals received 12 weeks of incentives for submitting a urine sample indicating alcohol abstinence, or the control group, in which individuals received 12 weeks of incentives for submitting a urine sample without the requirement of alcohol abstinence. Regression models fit with generalized estimating equations were used to assess differences in abstinence during the intervention period.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Alcohol-negative ethyl glucuronide (EtG) urine test result (defined as EtG<150 ng/mL).

Results

Among 1003 adults screened for eligibility, 400 individuals met the initial criteria. Of those, 158 individuals (39.5%; mean [SD] age, 42.1 [11.4] years; 83 men [52.5%]) met the criteria for randomization, which required submission of 4 or more urine samples and 1 alcohol-positive urine test result during the observation period before randomization. A total of 75 participants (47.5%) were randomized to the contingency management group, and 83 participants (52.5%) were randomized to the control group. At 16 weeks, the number who submitted an alcohol-negative urine sample was 19 (59.4%) in the intervention group vs 18 (38.3%) in the control group. Participants randomized to the contingency management group had a higher likelihood of submitting an alcohol-negative urine sample (averaged over time) compared with those randomized to the control group (odds ratio, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.05-2.76; P = .03).

Conclusions and Relevance

The study’s findings indicate that contingency management may be an effective strategy for increasing alcohol abstinence and a tool that can be used by American Indian and Alaska Native communities for the treatment of individuals with alcohol use disorders.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02174315

This randomized clinical trial examines whether a culturally tailored contingency management intervention, in which incentives are offered for laboratory-confirmed alcohol abstinence, results in increased alcohol abstinence among adults in 3 American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

Introduction

American Indian and Alaska Native people comprise 574 federally recognized tribes with substantial cultural, historical, and geographic diversity.1,2 American Indian and Alaska Native adults are more likely than non-Hispanic White adults to abstain from alcohol use3,4; however, American Indian and Alaska Native people who use alcohol are more likely to be diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder and have higher rates of alcohol-associated mortality relative to non-Hispanic White individuals.5,6,7Although American Indian and Alaska Native adults seek treatment for alcohol use at higher rates than adults who are not American Indian and Alaska Native,8,9,10,11,12 those who receive treatment are more likely to discontinue treatment early.10,13

In American Indian and Alaska Native communities, treatment for alcohol use disorder differs from Western approaches (such as group and individual counseling) to include traditional healing strategies (such as sweat lodges and other ceremonies) or combinations of Western and traditional healing approaches.14,15 Little empirical research has focused on the effectiveness of these interventions among American Indian and Alaska Native people. Published randomized clinical trials have observed intervention-associated reductions in alcohol use; however, most of these studies did not specifically focus on American Indian and Alaska Native people, had small samples, or were conducted in a single geographic location, limiting their generalizability to other American Indian and Alaska Native communities.16,17,18 Therefore, tribal health care professionals and policy makers lack information to make decisions regarding the best strategies to support community members with alcohol use disorders.

Contingency management is an intervention in which incentives (eg, motivational phrases, prizes, and/or gift cards) are provided when alcohol or drug abstinence is confirmed by urine test results.19 Contingency management has been associated with substantial reductions in illicit drug use.19,20,21 Initial evidence supports contingency management as an effective intervention for people with an alcohol use disorder.22,23,24 Contingency management may be appealing to American Indian and Alaska Native communities because it provides encouragement to individuals seeking to reduce alcohol use, it can be easily modified to improve cultural acceptability, it does not require a licensed clinician for implementation, it can be added to ongoing care, and it is inexpensive, with a typical cost of $300 to $500 per patient.19,22 Preparatory qualitative work indicated that contingency management was consistent with each community’s health priorities and values. Qualitative research suggested that contingency management should be adapted to include incentives that supported family relationships and integrated indigenous language and culture.25 In an initial study of a contingency management intervention that targeted alcohol and drug abstinence in a single Northern Plains community, contingency management was associated with reductions in alcohol and stimulant drug use.26,27

The Helping Our Native Ongoing Recovery (HONOR) study, a multisite randomized clinical trial, was designed to assess the outcomes of a culturally tailored contingency management intervention targeting alcohol abstinence among adults with alcohol dependence living in 3 geographically and culturally diverse American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

Methods

The HONOR clinical trial was conducted from October 10, 2014, to September 2, 2019. The study was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.28 The Washington State University and 2 Indian Health Service institutional review boards provided ethical oversight and approved the study protocol. Data-sharing and data-ownership agreements were signed by the investigators, 2 tribal governments, and 3 American Indian and Alaska Native organizations. Adverse events and serious adverse events were reported within 1 day to the principal investigator, who rated each event and worked with site investigators to manage each event. An independent data and safety monitoring board reviewed adverse events quarterly. Our community advisory board met annually to review study progress. The authors assume responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the data. All participants provided written informed consent. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline for randomized clinical trials.

Cultural Adaptations

Before the clinical trial began, our community advisory board, which included leadership from each study site, reviewed the study protocol (Supplement 1). The board recommended minor adaptations, such as decreasing the frequency of intervention visits from 3 to 2 times per week.

Feedback from focus groups with community members also led to the following adaptations: (1) tribal members or individuals who had experience working in American Indian and Alaska Native communities delivered the study interventions, (2) the native languages of the participating communities were included in intervention materials (ie, chips for prize drawings), and (3) practical (eg, gift cards for local businesses or fishing equipment) and cultural (eg, prizes for family activities or supplies for cultural artwork) prizes were added.25 Although the types of prizes varied by site, the monetary value of incentives was equal across sites.

Participant Selection

Participants were recruited from an urban American Indian health clinic and an urban community center in the Pacific Northwest (site 1), a tribally operated outpatient substance use treatment center located on a Northern Plains reservation (site 2), and the outpatient addiction clinic of the Southcentral Foundation, a tribally owned and operated health care organization in Anchorage, Alaska (site 3). Recruitment occurred between October 10, 2014, and February 20, 2019. Participants were recruited from October 2014 to July 2016 at site 1, from June 2015 to February 2019 at site 2, and from June 2016 to February 2019 at site 3.

Eligible participants were American Indian or Alaska Native adults (based on self-report), able to read and speak English, and able to provide written informed consent; had 1 or more days of high alcohol-use episodes (>3 drinks) within the last 30 days; and had a current diagnosis of alcohol dependence based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition)29 criteria, as assessed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview.30 Individuals were ineligible if they had more days of drug use than alcohol use within the last 90 days, experienced an alcohol detoxification-associated seizure or loss of consciousness within the last 12 months (or they or their practitioner were concerned about dangerous withdrawal effects), or had a medical or psychiatric illness that required hospitalization.

Clinical Trial Procedures

The study design was documented previously31 and is summarized in Supplement 1. Eligible participants were enrolled in a 4-week observation period before randomization, during which they could receive treatment as usual. They also received incentives for submitting urine samples twice per week (weeks 1-4). Participants who submitted at least 1 alcohol-positive urine sample and attended at least 4 of 8 visits during the observation period were randomized to receive 12 weeks (weeks 5-16) of treatment as usual and were assigned to either the contingency management group, in which participants received incentives for submitting alcohol-negative urine samples, or the control group, in which participants received incentives for submitting urine samples only, with no alcohol abstinence requirement. Participants completed follow-up interviews at 1, 2, and 3 months after the 12-week intervention period.

The use of an observation period before randomization had methodological and clinical benefits.22,31,32 It allowed us to select for randomization only those who needed the intervention (ie, those who continued to use alcohol, as verified by ethyl glucuronide [EtG] levels) and were appropriate for the intervention, which required brief visits twice per week. Those who could not attend brief twice-weekly visits in exchange for incentives (with no requirement of alcohol abstinence) were unlikely to be retained for participation in the contingency management intervention, which required twice-weekly appointments and alcohol abstinence. Those individuals were more likely to benefit from other treatments, such as brief programs or pharmacotherapy. The observation period also had the methodological advantage of reducing attrition in the randomized sample.

Block randomization was performed and stratified by study site and alcohol urine test result (positive or negative) at the study enrollment appointment. The allocation table was generated by the statistician using Stata software, version 13 (StataCorp), and participants were randomized by a university-based coordinator (A.J.L., J.H., or a nonauthor coordinator) using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software (Vanderbilt University). The coordinator and all other study staff who interacted with the participant did not know the original randomization sequence developed and uploaded by the statistician, who did not interact with participants. Participants were randomized after completing their last observational visit before randomization, and they were notified of their group assignment before their first intervention visit. Randomized participants were considered to be withdrawn from the study if they did not attend 6 consecutive appointments.

During the intervention phase, participants submitted urine samples twice weekly for 12 weeks. Participants in the contingency management group only received incentives in the form of prize drawings when the test result from their submitted urine sample was consistent with alcohol abstinence.22,33,34 Each time an alcohol-abstinent sample was provided, the participant received a minimum of 5 opportunities to draw a prize. The number of prize drawings increased by 1 drawing for every 2 consecutive alcohol-abstinent urine samples. Therefore, if a participant were continuously abstinent for the entire 12 weeks of the intervention, the participant could receive up to 32 opportunities to draw a prize during the final week of contingency management, or a maximum of 16 prize drawings per visit. Alcohol-positive or missing urine test results resulted in no prize drawing at that visit, with a reset to 5 prize drawings for the next alcohol-abstinent urine sample submitted.

Participants drew prizes from a 500-token container; each token was labeled with a word or phrase and could be exchanged for the prize indicated by the label. Fifty percent of tokens were labeled “good job” (or a similar positive affirmation in either the English language or a site-specific American Indian or Alaska Native language), for which no prize was awarded; 41.8% of tokens were labeled “small,” for which a $1 prize was awarded; 8% of tokens were labeled “large,” for which a $20 prize was awarded; and 0.2% of tokens were labeled “jumbo,” for which an $80 prize was awarded. Prizes included gift cards, fishing or camping equipment, arts and crafts supplies, and practical items, such as shampoo and clothing.

Participants in the control group drew prizes for each urine sample submitted. They received prize drawings regardless of their EtG test results. The number of prize drawings the control group received was equal to the average number of prize drawings the contingency management group received during the previous week, with no fewer than 5 prize drawings per submitted urine sample. The control group was used to reduce missing data and equalize the value of incentives across the groups.

Treatment as usual included culturally adapted individual and group addiction counseling delivered in an intensive outpatient addiction treatment format (ie, group counseling 3-5 times per week plus individual counseling at sites 2 and 3) or via referral for intensive outpatient addiction treatment that was not culturally adapted to American Indian and Alaska Native communities (at site 1).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was an EtG-negative urine sample (defined as EtG<150 ng/mL) assessed twice per week during the 12-week intervention period. Urine samples were analyzed for EtG levels using an enzyme immunoassay (Diagnostic Reagents) that was assessed on a benchtop analyzer (Indiko Benchtop Analyzer; ThermoFischer Scientific) located at each of the 3 study sites.

The secondary outcome was self-reported alcohol use within the last 30 days, as assessed by a question (“In the last 30 days, how many days have you used alcohol?”) from the Addiction Severity Index–Native American Version.35 Outcome assessors (J.H., A.J.L., J.S., K.J., L.D., K.L., and K.H.) were not blinded to group assignment.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographic characteristics were summarized using means and SDs for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. The differences in alcohol abstinence, as assessed by EtG levels, were analyzed using a logistic regression model via generalized estimating equations with an AR(1) correlation structure for repeated outcomes among participants. To help satisfy missing-at-random assumptions, the model was fit using multiple imputation.22,36 The multiple imputation model included site, treatment, time, and baseline EtG result as independent variables. Self-reported number of alcohol-abstinent days (0-30 days) was examined using an analysis similar to that performed for the primary outcome, but with a gaussian distribution and identity link used in the generalized estimating equations procedure.

We tested the addition of site and site-by-treatment interaction in our primary outcome model to assess the generalizability of treatment across sites. Results were reported using odds ratios (ORs) for binary outcomes and unstandardized regression coefficients for continuous outcomes. These association estimates were presented with their 95% CIs. Probability (ie, risk) estimates were reported for the primary outcome along with risk differences and associated bootstrap 95% CIs. We used a 2-sided 2-tailed error rate of α = .05 as the threshold for statistical significance.

Our power analysis assumed a correlation between points of 0.3, with a maximum of 36 data collection points for each participant, an α value of .05, and statistical power of 90%. We expected 20% attrition during the observation period based on data from previous studies.31,32 Therefore, we planned to enroll 400 participants and randomize 320 participants. The preceding parameters would allow us to detect an effect size (Cohen d) of 0.21 for the primary outcome.31 The statistical power was reduced because we decreased the number of urine tests collected from 36 to 24, and fewer individuals (n = 158) were randomized than we expected.

All analyses were conducted using the intention-to-treat principle. Statistical analysis was performed using R software, version 3.6.2, with the geepack and geeM packages for generalized estimating equations and the mice package for multiple imputation.37,38,39 Data were analyzed from February 1 to April 29, 2020.

Results

Participant Characteristics

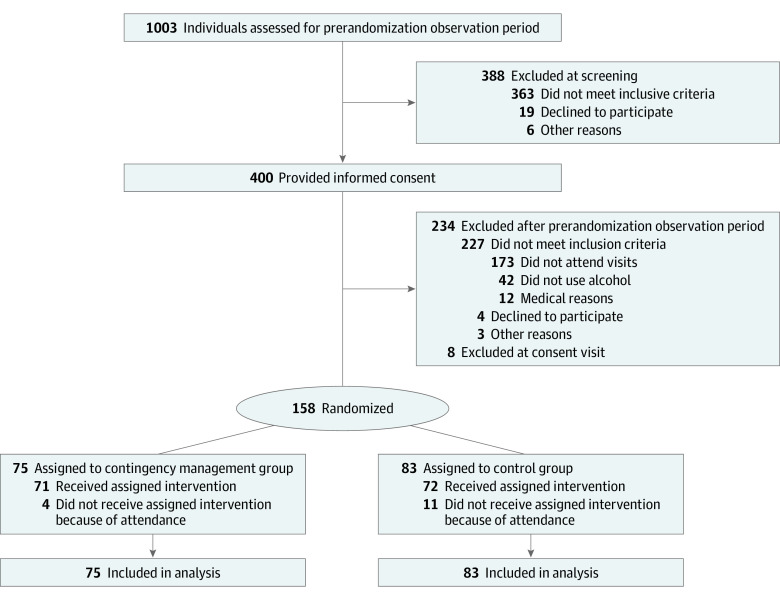

A total of 1003 individuals were screened for eligibility at the 3 study sites (Figure 1). At screening, 615 individuals (61.3%) were eligible for enrollment, and 388 individuals (38.7%) were ineligible. Of those who were ineligible, 289 individuals (74.5%) did not have 1 or more episode of high alcohol use within the last 30 days. A total of 400 participants were enrolled in the observation period before randomization. Among those enrolled, 158 participants (39.5%; mean [SD] age, 42.1 [11.4] years; 83 men [52.5%]) were randomized to either the contingency management group (75 participants [47.5%]) or the control group (83 participants [52.5%]) (Table). In total, 242 of 400 participants (60.5%) were not randomized; of those, 173 participants (71.5%) were not randomized because of nonattendance, 42 participants (17.4%) were not randomized because they did not have an alcohol-positive EtG test result, and 3 participants (1.2%) were not randomized for other reasons.

Figure 1. Participant Flowchart.

Table. Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Contingency management group | Control group | |

| Total participants, No. | 75 | 83 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 42.2 (11.1) | 41.9 (11.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 31 (41.3) | 44 (53.0) |

| Male | 44 (58.7) | 39 (47.0) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 75 (100) | 83 (100) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native only | 65 (86.7) | 70 (84.3) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native plus other race/ethnicity | 10 (13.3) | 13 (15.7) |

| ≥High school education | 65 (86.7) | 68 (81.9) |

| Married or long-term domestic partnership | 33 (44.0) | 46 (55.4) |

| Full-time or part-time employment | 54 (72.0) | 48 (57.8) |

| Stable housing | 49 (65.3) | 46 (55.4) |

| Maternal alcohol use | 58 (77.3) | 61 (73.5) |

| Current smoking | 43 (57.3) | 53 (63.9) |

| Ethyl glucuronide–negative test result (<150 ng/mL) at baseline | 31 (41.3) | 41 (49.4) |

| Site | ||

| 1 | 10 (13.3) | 11 (13.3) |

| 2 | 32 (42.7) | 37 (44.6) |

| 3 | 33 (44.0) | 35 (42.2) |

During the intervention period, 80 participants (50.6%) were withdrawn from the study; of those, 43 individuals (53.8%) were from the contingency management group, and 37 individuals (46.3%) were from the control group, which represented a nonsignificant difference. The median prize costs during the intervention period were $102 (25th-75th percentile, $33-$194) for the control group and $50 (25th-75th percentile, $2-$128) for the contingency management group. Only 19 participants (25.3%) in the contingency management group and 18 participants (21.7%) in the control group reported receiving treatment as usual for their alcohol use disorder during the intervention period.

Primary Outcome

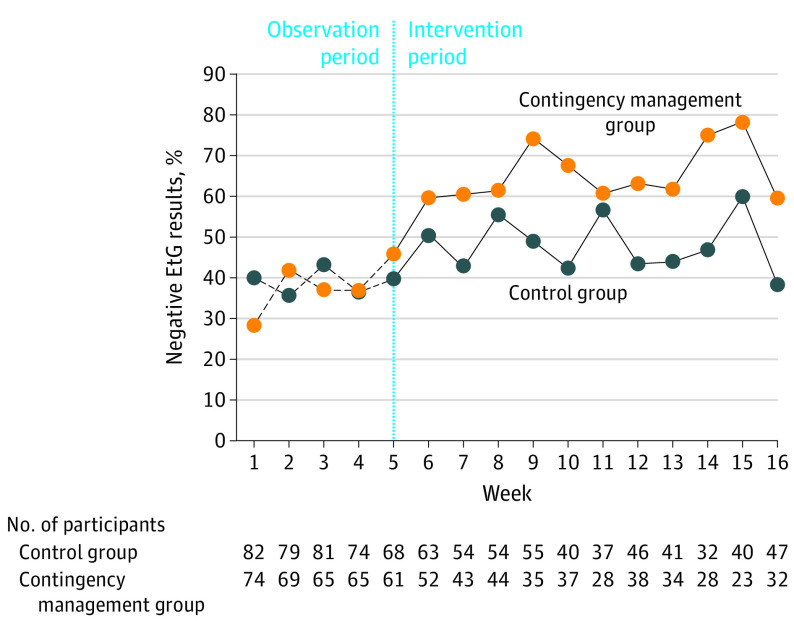

The interaction effect between site and treatment was not significant (F = 0.03; P = .97). Group differences in the percentage of alcohol-abstinent EtG test results over time among the participants with nonmissing values are shown in Figure 2. During the intervention period, 715 EtG tests were conducted in the contingency management group, and 912 EtG tests were conducted in the control group. At 16 weeks, the number who submitted an alcohol-negative urine sample was 19 (59.4%) in the intervention group vs 18 (38.3%) in the control group.

Figure 2. Percentage of Negative Ethyl Glucuronide Urine Test Results Over the Observation and Intervention Periods.

Alcohol abstinence over time represented by the percentage of negative EtG test results (EtG<150 ng/mL). The biweekly visits were combined as follows: (1) if the participant had a positive EtG test result at either of the visits, the combined result was recorded as positive; (2) if the participant had 1 positive EtG test result and 1 negative EtG test result, the combined result was recorded as positive; and (3) if both visits were missing, the combined result was recorded as missing. The combination of biweekly visits into weeks was for display purposes only. EtG indicates ethyl glucuronide.

The contingency management group had a higher likelihood of submitting an alcohol-abstinent EtG sample (averaged over time) compared with the control group (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.05-2.76; P = .03). Based on the generalized estimating equation estimates, participants in the control and contingency management groups had a 52.8% and 65.6% probability, respectively, of submitting an alcohol-abstinent EtG sample during the intervention period. The estimated risk difference between treatment groups was 12.8% (95% CI, 8.6%-17.3%).

Secondary Outcome and Adverse Events

Self-reported alcohol use within the last 30 days was lower in the contingency management group relative to the control group (mean difference, –2.1 days; 95% CI, –4.8 to 0.6 days), but this difference was not statistically significant. The mean number of days of alcohol use within the last 30 days was 8.1 (95% CI, 6.1-10.0) in the control group and 5.9 (95% CI, 3.8-8.1) in the contingency management group.

Compared with the control group, the contingency management group had fewer adverse events (85 events vs 65 events, respectively) and fewer serious adverse events (4 events vs 1 event, respectively). No events were rated as study-associated. The most common adverse event was a nonalcohol-associated emergency department visit (66 events).

Discussion

In this multisite clinical trial conducted in partnership with 3 geographically and culturally diverse American Indian and Alaska Native communities, adults who received incentives for alcohol abstinence had a 1.70-fold higher likelihood of submitting alcohol-abstinent urine samples relative to adults in the control group. These intervention effects were observed even though the median cost of incentives was only $50 per patient for 12 weeks of contingency management. Although the contingency management group reported lower levels of alcohol use than the control group, this difference was not significantly different. The lack of a significant difference could be because of the study’s insufficient statistical power, as our randomized sample was smaller than expected.

The study’s results are consistent with those of another single-site clinical trial conducted in partnership with a Northern Plains reservation–based community, in which 112 participants received a contingency management intervention that was targeted at both alcohol and drug abstinence.26,27 In that study, individuals assigned to 3 different contingency management interventions had a higher likelihood of submitting EtG-confirmed alcohol-abstinent urine samples relative to the control group. Together, these 2 clinical trials provide evidence that, when delivered by organizations that serve American Indian adults and Alaska Native adults, contingency management is associated with reduced alcohol use during the intervention period.

Findings of the present study provide additional evidence that contingency management is an effective intervention for individuals with alcohol use disorders. Previous studies have reported that contingency management is associated with reductions in alcohol use.22,23,24 However, to our knowledge, the present clinical trial is the first multisite study to investigate contingency management interventions targeting alcohol abstinence in any population using a biomarker (EtG) that can accurately detect alcohol use. In this and previous EtG-based contingency management studies, a costly urine analyzer was required to obtain EtG results. The recent availability of low-cost point-of-care EtG tests now allows for feasible monitoring of alcohol use and implementation of contingency management interventions for those with an alcohol use disorder.40,41

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the study was a multisite clinical trial, its results may not be generalizable to all American Indian and Alaska Native groups or treatment settings given the diversity of native people. Outcomes did not differ by study site, although we may not have had the statistical power to detect a treatment-by-site interaction. We had relatively high levels of missing data, and the overall level of missing data was higher in the contingency management group relative to the control group. However, groups were not significantly different in attrition, which is the primary reason for missingness. Consistent with our a priori analytic plan and published studies, we applied multiple imputation techniques to account for missing data using a set of hypothesized estimates of missingness.21,22,31,42,43 Therefore, raw percent differences are not reported owing to varying levels of observed missingness over time.

Levels of attrition in the contingency management group were lower than those reported in previous studies of American Indian and Alaska Native adults receiving alcohol treatment and were also lower than those observed by our community partners among adults receiving treatment as usual.11,13 Our partners reported that attrition from their outpatient treatment programs was approximately 74% at 12 weeks. We took extensive steps to minimize attrition, including providing transportation to participants. The use of an observation period before randomization allowed us to exclude those who could not meet the minimal attendance requirements of the contingency management intervention, with the goal of reducing attrition in the randomized sample. As a result, our findings cannot be generalized to all American Indian and Alaska Native adults with alcohol use disorders.

Conclusions

This community-engaged multisite clinical trial provides potentially valuable information for American Indian and Alaska Native tribes, urban American Indian and Alaska Native organizations, and groups such as the Indian Health Service, which are responsible for providing treatment to American Indian and Alaska Native people with alcohol use disorders. Our findings demonstrate that contingency management is a low-cost, feasible, and culturally adaptable incentive program that leads to modest improvements in alcohol abstinence during a 12-week intervention period. Policy makers and health care professionals may consider investing in contingency management as a strategy for improving the treatment of alcohol use disorder among American Indian and Alaska Native adults.

Trial Protocol

Nonauthor Collaborators. The HONOR Study Team

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Getches DH, Wilkinson CF, Williams RA, Jr. Cases and Materials on Federal Indian Law. 4th ed. West Group; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Conference of State Legislatures. Federal and state recognized tribes. Updated March 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www.ncsl.org/research/state-tribal-institute/list-of-federal-and-state-recognized-tribes.aspx

- 3.Cunningham JK, Solomon TA, Muramoto ML. Alcohol use among Native Americans compared to Whites: examining the veracity of the ‘Native American elevated alcohol consumption’ belief. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:65-75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . Alcohol Use and Alcohol Use Disorders in the United States: Main Findings From the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). National Institutes of Health; 2006. US Alcohol Epidemiologic Data Reference Manual. Vol 8. NIH publication 05-5737. Accessed May 8, 2020. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/NESARC_DRM/NESARCDRM.pdf

- 5.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality . Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2017-nsduh-detailed-tables

- 6.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landen M, Roeber J, Naimi T, Nielsen L, Sewell M. Alcohol-attributable mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1999-2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 3):S343-S349. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The NSDUH report: need for and receipt of substance use treatment among American Indians or Alaska Natives. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012. Accessed February 18, 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH120/NSDUH120/SR120-treatment-need-AIAN.htm

- 9.Emerson MA, Moore RS, Caetano R. Correlates of alcohol-related treatment among American Indians and Alaska Natives with lifetime alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43(1):115-122. doi: 10.1111/acer.13907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beals J, Novins DK, Spicer P, Whitesell NR, Mitchell CM, Manson SM; American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk, and Protective Factors Project Team . Help seeking for substance use problems in two American Indian reservation populations. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(4):512-520. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.4.512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickerson DL, Spear S, Marinelli-Casey P, Rawson R, Li L, Hser Y-I. American Indians/Alaska Natives and substance abuse treatment outcomes: positive signs and continuing challenges. J Addict Dis. 2011;30(1):63-74. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2010.531665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JL, Cameron MC. Barriers to providing effective mental health services to American Indians. Ment Health Serv Res. 2001;3(4):215-223. doi: 10.1023/A:1013129131627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans E, Spear SE, Huang Y-C, Hser Y-I. Outcomes of drug and alcohol treatment programs among American Indians in California. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):889-896. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Legha RK, Novins D. The role of culture in substance abuse treatment programs for American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(7):686-692. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koithan M, Farrell C. Indigenous Native American healing traditions. J Nurse Pract. 2010;6(6):477-478. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2010.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villanueva M, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. Response of Native American clients to three treatment methods for alcohol dependence. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2007;6(2):41-48. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foley K, Pallas D, Forcehimes AA, et al. Effect of job skills training on employment and job seeking behaviors in an American Indian substance abuse treatment sample. J Vocat Rehabil. 2010;33(3):181-192. doi: 10.3233/JVR-2010-0526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Malley SS, Robin RW, Levenson AL, et al. Naltrexone alone and with sertraline for the treatment of alcohol dependence in Alaska natives and non-natives residing in rural settings: a randomized controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(7):1271-1283. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00682.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benishek LA, Dugosh KL, Kirby KC, et al. Prize-based contingency management for the treatment of substance abusers: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2014;109(9):1426-1436. doi: 10.1111/add.12589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179-187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonell MG, Srebnik D, Angelo F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of contingency management for stimulant use in community mental health patients with serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(1):94-101. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11121831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonell MG, Leickly E, McPherson S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of ethyl glucuronide–based contingency management for outpatients with co-occurring alcohol use disorders and serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(4):370-377. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes, and they will come: contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(2):250-257. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koffarnus MN, Wong CJ, Diemer K, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a therapeutic workplace for chronically unemployed, homeless, alcohol-dependent adults. Alcohol. 2011;46(5):561-569. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirchak KA, Leickly E, Herron J, et al. ; HONOR Study Team . Focus groups to increase the cultural acceptability of a contingency management intervention for American Indian and Alaska Native communities. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;90:57-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonell MG, Skalisky J, Burduli E, et al. The rewarding recovery study: a randomized controlled trial of incentives for alcohol and drug abstinence with a rural American Indian community. Addiction. Published online November 21, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burduli E, Skalisky J, Hirchak K, et al. Contingency management intervention targeting co-addiction of alcohol and drugs among American Indian adults: design, methodology, and baseline data. Clin Trials. 2018;15(6):587-599. doi: 10.1177/1740774518796151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). a short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):224-231. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonell MG, Nepom JR, Leickly E, et al. A culturally-tailored behavioral intervention trial for alcohol use disorders in three American Indian communities: rationale, design, and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;47:93-100. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silverman K, Wong CJ, Needham M, et al. A randomized trial of employment-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in injection drug users. J Appl Behav Anal. 2007;40(3):387-410. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowe JM, McDonell MG, Leickly E, et al. Determining ethyl glucuronide cutoffs when detecting self-reported alcohol use in addiction treatment patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):905-910. doi: 10.1111/acer.12699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonell MG, Skalisky J, Leickly E, et al. Using ethyl glucuronide in urine to detect light and heavy drinking in alcohol dependent outpatients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;157:184-187. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carise D, McLellan AT. Increasing cultural sensitivity of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI): an example with Native Americans in North Dakota. Special Report. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 1999. Accessed March 19, 2020. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED449953.pdf

- 36.van Buuren S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data. 2nd ed. Chapman & Hall; 2018. doi: 10.1201/9780429492259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. MICE: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1-67. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halekoh U, Hojsgaard S, Yan J. The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. J Stat Softw. 2006;15(2):1-11. doi: 10.18637/jss.v015.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDaniel LS, Henderson NC, Rathouz PJ. Fast pure R implementation of GEE: application of the matrix package. R J. 2013;5(1):181-187. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2013-017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vinikoor MJ, Zyambo Z, Muyoyeta M, Chander G, Saag MS, Cropsey K. Point-of-care urine ethyl glucuronide testing to detect alcohol use among HIV-hepatitis B virus coinfected adults in Zambia. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(7):2334-2339. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2030-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.EtG test. Confirm Biosciences. Published 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www.confirmbiosciences.com/knowledge/terminology/etg/

- 42.McPherson S, Barbosa-Leiker C, McDonell M, Howell D, Roll J. Longitudinal missing data strategies for substance use clinical trials using generalized estimating equations: an example with a buprenorphine trial. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2013;28(5):506-515. doi: 10.1002/hup.2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McPherson S, Barbosa-Leiker C, Burns GL, Howell D, Roll J. Missing data in substance abuse treatment research: current methods and modern approaches. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20(3):243-250. doi: 10.1037/a0027146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Nonauthor Collaborators. The HONOR Study Team

Data Sharing Statement