Abstract

Objective:

This study examined whether cigarette smoking mediated the association of racial discrimination with depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women.

Design:

Cross-sectional.

Sample:

Two hundred Black women at 8–29 weeks gestation.

Measurements:

Women completed questionnaires including the Experiences of Discrimination and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scales, as well as questions about sociodemographic characteristics and cigarette smoking.

Results:

The mean age of the sample was 26.9±5.7 years and the mean gestational age at data collection was 15.6±5.7 weeks. Approximately 17% of women reported prenatal cigarette smoking; 27% had prenatal CES-D scores ≥ 23, which have been correlated with depression diagnoses; and 59% reported ever (lifetime) experiencing discrimination in at least one situation (e.g., at work). Path analysis results indicated that the standardized indirect effect of experiences of racial discrimination on CES-D scores through prenatal smoking was statistically significant (standardized indirect effect = 0.03; 95% CI: 0.001, 0.094; p = 0.042).

Conclusion:

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy partially mediated the association between lifetime experiences of racial discrimination and prenatal depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women. Smoking cessation programs should focus on identifying and treating depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women.

Keywords: Racial discrimination, Cigarette smoking, Depressive symptoms, Pregnant women

INTRODUCTION

Pregnant Black women, as expected, are more likely to be exposed to racial discrimination, defined as being hassled or made to feel inferior due to one’s race, ethnicity, or color(Krieger et al., 2010) compared with pregnant non-Hispanic White women (Dominguez, Dunkel-Schetter, Glynn, Hobel, & Sandman, 2008). Among 96 pregnant Black women from Chicago, 53% reported any lifetime racial discrimination (Giurgescu et al., 2016). The most frequently reported situations of racial discrimination were related to service in a store or restaurant (34%); getting hired or getting a job (20%); and interactions on the street or in a public setting (20%) (Giurgescu et al., 2016). A study of 778 pregnant and postpartum Black women from Baltimore assessed racial discrimination using four items: (1) overall, during your lifetime, how much have you personally experienced racism, racial prejudice, or racial discrimination; (2) during the past year, how much have you personally experienced racism, racial prejudice, or racial discrimination; (3) how much racism had affected the life experiences of people close to them; and (4) how much had they thought racism affected the lives of others belonging to their racial/ethnic group (Slaughter-Acey, Talley, Stevenson, & Misra, 2019). These researchers found that >90% of women reported racial discrimination (for 1 item: 16.3%; 2 items: 26.4%; 3 items: 21.7%; 4 items: 29.4%)(Slaughter-Acey et al., 2019). These results suggest that Black women experience racial discrimination in many situations.

Racial discrimination is related to depressive symptoms among Blacks. A recent meta-analysis of studies with non-pregnant multiethnic samples published between 1983 and 2013 and conducted predominantly in the U.S. reported that racial discrimination was related to poorer mental health outcomes; depressive symptoms were the most commonly reported mental health outcome (Paradies et al., 2015). Pregnant Black women are more likely to experience depressive symptoms compared with pregnant White women (Mukherjee, Trepka, Pierre-Victor, Bahelah, & Avent, 2016). Research suggests that racial discrimination may be related to the higher rates of depressive symptoms seen in this population. Pregnant Black women who reported lifetime exposure to racial discrimination were more likely to also report depressive symptoms (Giurgescu et al., 2016). Similarly, depressive symptoms moderated the impact of racial discrimination on risk of preterm birth among 1,400 Black women with data collected immediately during the postpartum period (Slaughter-Acey et al., 2016). In unpublished results from this cohort of Black women as well as a cohort of Black women delivering in Baltimore [n=872, see (Misra, Strobino, & Trabert, 2010) for study details], depressive symptoms scored on a continuum or above a threshold were significantly, strongly, and positively associated with measures of racism. These results suggest that racial discrimination may relate to U.S. Black-White disparities in depressive symptoms. However, data on the potential pathways linking racial discrimination and depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women are limited.

Cigarette smoking has been related to both racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in a number of studies outside of pregnancy. Lifetime experiences of racial discrimination were positively related to smoking among Black non-pregnant adults (Brondolo et al., 2015). Using data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study (n1=1169 African-Americans; n2=1322 Whites), Borrell et al. found that experiences of discrimination due to race or color, gender, and socioeconomic position or social class were positively related to cigarette smoking (Borrell, Kiefe, Diez-Roux, Williams, & Gordon-Larsen, 2013). Among a multi-ethnic sample of women (1806 non-Hispanic White, 874 Hispanic, 149 African American), those who experienced racial-ethnic discrimination had a 1.6 [95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.1, 2.2] greater odds of cigarette smoking compared with women who did not experience racial-ethnic discrimination after adjustment for age, marital status, race-ethnicity, education, income, and survey language (Plascak, Hohl, Barrington, & Beresford, 2018). A recent systematic review also reported a positive association between cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms among non-pregnant adults (Fluharty, Taylor, Grabski, & Munafò, 2017). In a study with Black adults ages 55 or older who lived in economically impoverished urban areas, participants who smoked cigarettes reported more depressive symptoms compared with participants who did not smoke cigarettes (Bazargan, Cobb, Castro Sandoval, & Assari, 2020). In another study with a sample with women who smoked (83 European American and 175 African American), smoking was significantly correlated with depressive symptoms among African American women only (Ludman et al., 2002). These results suggest that cigarette smoking is related to racial discrimination and depressive symptoms among non-pregnant Black adults.

In one of the few published studies on the association of cigarette smoking with racism and depressive symptoms in pregnant Black women, higher levels of perceived racism [Odds Ratio (OR)=1.15; 95%CI: 1.01, 1.31; p<.05] and depression (OR=1.48; 95%CI: 1.19, 1.83; p<.001) were each associated with higher odds of being a smoker than a non-smoker among pregnant Black women (Maxson, Edwards, Ingram, & Miranda, 2012). No published studies have examined the potential mediating effect of cigarette smoking during pregnancy on the association between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women. Cigarette smoking may be a maladaptive coping strategy for pregnant Black women in order to deal with experiences of racial discrimination; may be linked to higher levels of depressive symptoms; and it is a modifiable factor that can be intervened on. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine whether cigarette smoking mediated the association of racial discrimination with depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women. We hypothesized that cigarette smoking during pregnancy mediates the association between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms among these women.

METHODS

Design and Sample

The data reported here were collected as part of the Biosocial Impact on Black Births (BIBB) study. BIBB is a prospective study that examines the role of maternal factors on birth outcomes among Black women across pregnancy. This subsample of 203 pregnant Black women was recruited from prenatal care clinics in two metropolitan areas in the Midwest United States between January 04, 2018 and December 31, 2018. Women were enrolled in the study if they self-identified as Black or African American, were ages 18–45 years old, had singleton pregnancies, were less than 30 weeks gestation, and were able to read and write English.

Variables and Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics.

Women responded to questions about socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., age, level of education, household income).

Cigarette smoking.

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy was assessed by the question “Did you smoke cigarettes during this pregnancy?” (Yes=1 vs. No=0). Cigarette smoking prior to pregnancy was assessed by the question “Did you smoke cigarettes before this pregnancy?” (Yes=1 vs. No=0). If a participant answered that she smoked both prior to pregnancy and during pregnancy, she was identified as continued smoking during pregnancy; otherwise, she was identified a stopped smoking during pregnancy.

Racial discrimination.

The Experiences of Discrimination (EOD) measures self-reported lifetime experiences of discrimination due to race, ethnicity or color in nine situations (e.g., at school; at work; getting service from store or restaurant; getting medical care; see Table 2 for complete list) (Krieger, 1990; Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman, & Barbeau, 2005). For each situation, respondents may reply yes = 1 or no = 0. The sum of all nine situations equals the total score (range 0–9). The EOD has established construct validity in a sample of Black adults (Krieger et al., 2005). In the current study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.83.

Table 2.

Percentage Distribution of Situations of Racial Discrimination by Cigarette Smoking Status during Pregnancy (N=200)

| Situations of racial discrimination | Cigarette smoking during pregnancy | |

|---|---|---|

| No n1=167 (83.5%) | Yes n2=33 (16.5%) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| At school | ||

| No | 134 (85.9) | 22 (14.1) |

| Yes | 32 (74.4) | 11 (25.6) |

| Getting hired or getting a job | ||

| No | 134 (88.7) | 17 (11.3)*** |

| Yes | 32 (66.7) | 16 (33.3) |

| At work | ||

| No | 122 (87.1) | 18 (12.9) |

| Yes | 42 (76.4) | 13 (23.6) |

| Getting housing | ||

| No | 144 (86.7) | 22 (13.3)** |

| Yes | 22 (66.7) | 11 (33.3) |

| Getting medical care | ||

| No | 149 (82.8) | 31 (17.2) |

| Yes | 17 (89.5) | 2 (10.5) |

| Getting service in a store or restaurant | ||

| No | 106 (89.1) | 13 (10.9)** |

| Yes | 60 (75.0) | 20 (25.0) |

| Getting credit, bank loans, or a mortgage | ||

| No | 146 (84.9) | 26 (15.1) |

| Yes | 18 (72.0) | 7 (28.0) |

| On the street or in a public setting | ||

| No | 116 (88.5) | 15 (11.5)** |

| Yes | 50 (73.5) | 18 (26.5) |

| From police or in the courts | ||

| No | 122 (85.3) | 21 (14.7) |

| Yes | 43 (78.2) | 12 (21.8) |

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Depressive symptoms.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) assesses the presence of salient symptoms of depression within the past seven days (Radloff, 1977). CES-D items are assessed on a 4-point scale (0=rarely to 3=most of the time) and then summed with a potential range of 0–60. Higher scores represent more depressive symptoms. The CES-D does not provide a diagnosis of clinical depression, but a score of ≥23 has been related to depression diagnosis (Orr, Blazer, James, & Reiter, 2007). In the current study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.89.

Maternal medical history.

Using an instrument developed for this study, women were asked to indicate whether they had ever experienced any of the following conditions prior to the pregnancy and to describe the condition: asthma or other lung problems; heart problems; hypertension or elevated blood pressure; kidney problems that were more severe than a bladder infection or UTI; diabetes or elevated blood sugar levels; and thyroid problems. There was also an opportunity to specify the other conditions impacting pregnancy.

Procedures

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at the two sites. The principal investigator obtained a HIPAA waiver to access medical records of women receiving prenatal care at the participating sites in order to identify potential participants. Research staff approached eligible women and invited them to participate. After obtaining informed consent, participants completed a questionnaire on an iPad. A sample of 203 women completed the questionnaires. Three women had incomplete data for cigarette smoking; therefore, a sample of 200 women was used for data analysis. Women were reimbursed a $30 store gift card for their participation.

Data Management

Data were entered into Qualtrics Research Suite, a web-based platform for creating online surveys. Password-protected, customer-controlled survey data were captured in real-time and stored on Qualtrics’ secure and Transport Layer Security (TLS) encrypted servers. Variables used in the path analysis had a low percentage of missing data (e.g., 0.5%−3.4%). We assumed that our data were missing completely at random (MCAR) and the missing data were replaced using the multiple imputation (MI) method (IBM Corporation) and one of the five imputed datasets being used in the path analysis. If a woman answered that she smoked, it coded as “1”; otherwise, it coded as “0”.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to describe sociodemographic characteristics, maternal medical history, smoking history, racial discrimination, and depressive symptoms. The independent samples t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables were used to examine differences among these factors between women who smoked and did not smoke cigarettes during pregnancy. Bivariate linear regression was used to examine the associations among racial discrimination, cigarette smoking, and depressive symptoms. Bivariate and multiple logistic regression (cigarette smoking as the dependent variable) and linear regression (depressive symptoms as the dependent variable) were employed to examine associations among racial discrimination, cigarette smoking, and depressive symptoms after controlling for maternal age, level of education, and gestational age at data collection. A path analysis model was created to test the mediating role of cigarette smoking on the association between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms. Maternal age, level of education, and gestational age at data collection were included as the covariates in the path analysis model. We estimated (a) the direct effect from racial discrimination to cigarette smoking; (b) the direct effect from cigarette smoking to depressive symptoms; and (c) the standardized indirect effect from racial discrimination to depressive symptoms through cigarette smoking. Maximum likelihood (ML) method was performed for the estimates. The bootstrapping estimates were calculated. The 95% confidence intervals for standardized indirect effect and bias-corrected percentile p-value for the indirect effect were estimated. Model Fit Statistics used in this study as follow. The Chi-square value (p value > 0.05), Chi-square to degrees-of-freedom ratio (χ2/df < 3), goodness-of-fit index (GFI > 0.95), normed fit index (NFI > 0.95), comparative fit index (CFI > 0.95), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08) were included to evaluate the overall fit of the hypothesized model to data (Schreiber, 2017). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 and Amos version 26.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Women had a mean age of 26.9±5.6 years (range 18–42), and a mean gestational age at data collection of 15.6±5.7 weeks (range 8–29). About 16.5% (33/200) of women reported cigarette smoking during pregnancy; 27.0% (54/200) reported CES-D scores ≥23; and 59.0% (118/200) reported experiencing racial discrimination in at least one situation. Women who smoked cigarettes during pregnancy were more likely to have lower levels of education (e.g., less than high school education 37% and 13%, respectively), report more experiences of racial discrimination (3.33 and 1.90, respectively) and have higher CES-D mean scores (20.2 and 15.6, respectively) compared with women who did not smoke during pregnancy (see Table 1). Of the 33 women who reported smoking during the pregnancy, seven women (21.2%) reported smoking 1–2 cigarettes/ day; 16 women (48.5%) reported smoking 3–6 cigarettes/ day; five women (15.2%) reported smoking 8–10 cigarettes/ day; two women (6.1%) reported smoking > 10 cigarettes/ day; and three (9.1%) women did not report the number of cigarettes smoked per day (data not shown).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Cigarette Smoking Status during Pregnancy (N=200)

| Covariates | Cigarette smoking during pregnancy (N=200) | Cigarette smoking prior to pregnancy (N=200) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No n1=167 (83.5%) |

Yes n2=33 (16.5%) |

Yes 66 (33.0%) |

Nob 134 (67.0%) |

||

| Stopped smoking during pregnancy n3=35 (53.0%) | Continued smoking during pregnancy n4=31 (47.0%) | ||||

| M (SD)a | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 26.71 (5.74) | 27.18 (5.23) | 27.57 (5.03) | 27.42 (5.23) | 26.44 (5.89) |

| Gestational age at data collection (weeks) | 15.62 (5.74) | 16.00 (5.70) | 16.31 (5.90) | 16.03 (5.77) |

15.43 (5.69) |

| EOD scores | 1.90 (2.30) | 3.33 (2.73)** | 1.91 (2.49) | 3.35 (2.71)* | 1.92 (2.77) |

| CES-D scores | 15.61 (10.11) | 20.24 (10.81)* | 15.8 (9.04) | 20.94 (10.79) | 15.47 (10.36) |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age category (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 68 (87.2) | 10 (12.8) | 9 (50.0) | 9 (50.0) | 60 (76.9) |

| 25–29 | 49 (81.7) | 11 (18.3) | 13 (56.5) | 10 (43.5) | 37 (61.7) |

| 30–34 | 32 (80.0) | 8 (20.0) | 10 (55.6) | 8 (44.4) | 22 (55.0) |

| ≥35 | 18 (81.8) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 15 (68.2) |

| Gestational age at data collection category (weeks) | |||||

| 8–12 weeks | 66 (84.6) | 12 (15.4) | 14 (56.0) | 11 (44.0) | 53 (67.9) |

| 13–29 weeks | 101 (82.8) | 21 (17.2) | 21 (51.2) | 20 (48.8) | 81 (66.4) |

| Household income | |||||

| < $10,000 | 61 (77.2) | 18 (22.8) | 15 (46.9) | 17 (53.1) | 47 (59.5) |

| $10,000 –$19,999 | 31 (91.2) | 3 (8.8) | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | 25 (73.5) |

| $20,000 – $29,999 | 32 (84.2) | 6 (15.8) | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 26 (68.4) |

| $30,000 – $39,999 | 18 (85.7) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 14 (66.7) |

| ≥$40,000 | 19 (90.5) | 2 (9.5) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 16 (76.2) |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 17 (63.0) | 10 (37.0) * | 7 (43.8) | 9 (56.3) | 11 (40.7)* |

| Graduated high school/GED | 82 (84.5) | 15 (15.5) | 13 (46.4) | 15 (53.6) | 69 (71.1) |

| Technical/vocational training | 15 (83.3) | 3 (16.7) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 10 (55.6) |

| Some college/above | 49 (90.7) | 5 (9.3) | 10 (71.4) | 4 (28.6) | 40 (74.1) |

| Employment | |||||

| Not working | 76 (86.4) | 12 (13.6) | 18 (62.1) | 11 (37.9) | 59 (67.0) |

| Working | 89 (80.9) | 21 (19.1) | 17 (45.9) | 20 (54.1) | 73 (66.4) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Ever married | 73 (85.9) | 12 (14.1) | 20 (62.5) | 12 (37.5) | 53 (62.4) |

| Never married | 91 (82.0) | 20 (18.0) | 14 (43.8) | 18 (56.3) | 79 (71.2) |

| Living with father of the baby (FOB) | |||||

| Not living with FOB | 105 (81.4) | 24 (18.6) | 18 (45.0) | 22 (55.0) | 89 (69.0) |

| Living with FOB | 59 (88.1) | 8 (11.9) | 16 (66.7) | 8 (33.3) | 43 (64.2) |

| Health insurance | |||||

| Privately insured | 9 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | − | − | 9 (100.0) |

| Publicly insured | 142 (82.1) | 31 (17.9) | 32 (52.5) | 29 (47.5) | 112 (64.7) |

| Don’t know/Unsure | 16 (88.9) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 13 (72.2) |

| Chronic conditions | |||||

| Asthma (yes%) | 39 (83.0) | 8 (17.0) | 11 (57.9) | 8 (42.1) | 28 (59.6) |

| Hypertension (yes%) | 14 (87.5) | 2 (12.5) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 10 (62.5) |

| Thyroid (yes%) | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 5 (50.0) |

| Diabetes (yes%) | 10 (76.9) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 8 (61.5) |

| Heart disease (yes%) | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| Kidney disease (yes%) | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | − | − | 3 (100.0) |

| EOD scores ≥1 | |||||

| No | 73 (89.0) | 9 (11.0) | 18 (69.2) | 8 (30.8)* | 56 (68.3) |

| Yes | 94 (79.7) | 24 (20.3) | 17 (42.5) | 23 (57.5) | 78 (66.1) |

| CES-D scores ≥23 | |||||

| No | 125 (86.2) | 20 (13.8) | 25 (58.1) | 18 (41.9) | 102 (70.3) |

| Yes | 41 (75.9) | 3 (24.1) | 10 (43.5) | 13 (56.5) | 31 (57.4) |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

Note: SD = standard deviation; EOD=Experiences of Discrimination; CES-D=Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression.

percentage in this column was calculated with the denominator of 200.

Sixty-six (33%) women smoked cigarettes prior to pregnancy. Of these women, 35 women stopped smoking cigarettes during pregnancy and 31 women continued to smoke cigarettes during pregnancy. Women who continued smoking cigarettes during pregnancy reported more experiences of racial discrimination compared with women who stopped smoking cigarettes during pregnancy (3.35 and 1.91, respectively). There were no other differences in sample characteristics between women who continued to smoke cigarettes during pregnancy and women who stopped smoking cigarettes during the pregnancy (see Table 1).

Women who smoked cigarettes during pregnancy reported more situations of discrimination when getting hired or getting a job [48% (16/33) vs. 19% (32/167), respectively], getting housing [33% (11/33) vs. 13% (22/167), respectively], getting service in a store or restaurant [61% (20/33) vs. 36% (60/167), respectively], and on the street or in a public setting [55% (18/33) vs. 30% (50/167), respectively] (see Table 2).

Associations among racial discrimination, cigarette smoking during pregnancy and depressive symptoms

Bivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that racial discrimination was significantly positively associated with cigarette smoking (OR = 1.25; 95%CI = 1.08, 1.44; p < 0.01). This association remained significant in the multiple logistic regression after controlling for maternal age, level of education, and gestational age at data collection (OR = 1.31, 95%CI = 1.12, 1.52, p < 0.01).

Bivariate linear regression analysis indicated that racial discrimination was significantly positively associated with CES-D scores (β = 0.60; 95%CI = 0.01, 1.19; p < 0.05). Cigarette smoking was significantly positively associated with CES-D scores (β = 4.63; 95%CI = 0.78, 8.47; p < 0.05). Multiple linear regression analysis results indicated that the magnitude and statistical significance of the association between racial discrimination and cigarette smoking during pregnancy and the association between cigarette smoking during pregnancy and CES-D scores remained after controlling for maternal age, level of education, and gestational age at data collection (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Bivariate and Multiple Logistic Regression and Linear Regression Analysis (N=200)

| Logistic regression | Linear regression | |

|---|---|---|

| Cigarette smoking during pregnancy | CES-Da scores | |

| OR (95% C.I.) | β (95% C.I.) | |

| Model 11 | ||

| Racial discrimination | 1.25 (1.08, 1.44)** | 0.60 (0.01, 1.19)* |

| Cigarette smoking during pregnancy | - | 4.63 (0.78, 8.47)* |

| Model 22 | ||

| Racial discrimination | 1.31 (1.12, 1.52)** | 0.63 (0.02, 1.23)* |

| Cigarette smoking during pregnancy | - | 4.10 (0.15, 8.04)* |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Note: β = Unstandardized regression coefficient; 95% C.I. = 95% Confidence Interval; OR=odds ratio; CES-D=Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression.

Separate bivariate models.

Covariates in multiple logistic regression and linear regression are maternal age, level of education, and gestational age at data collection.

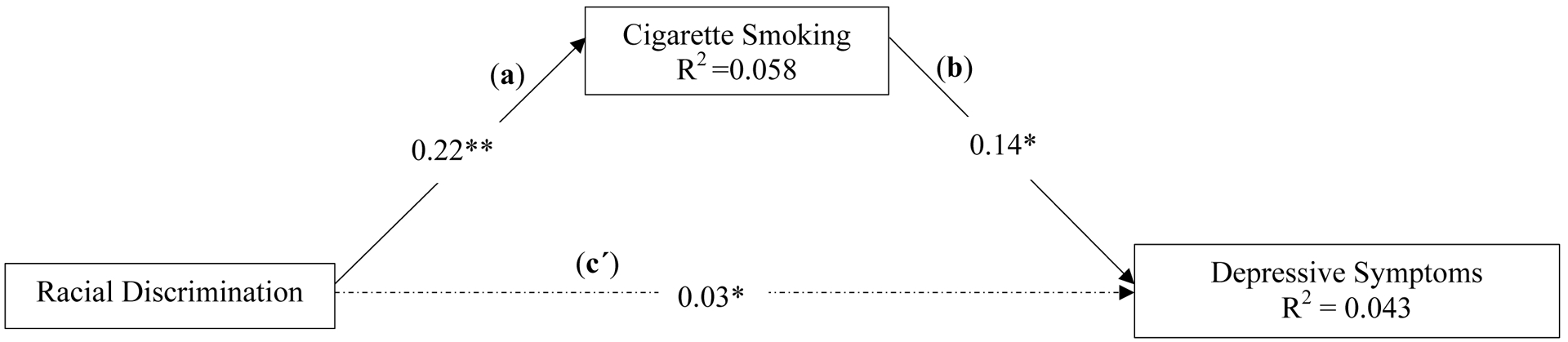

Path analysis

As hypothesized, path analysis indicated that cigarette smoking during pregnancy mediated the association between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms among these women. Path analysis model results indicated that racial discrimination was positively associated with cigarette smoking during pregnancy (the standardized direct effect = 0.22, p < 0.01), and cigarette smoking during pregnancy was positively associated with CES-D scores (the standardized direct effect = 0.14, p < 0.05) after controlling for maternal age, level of education and gestational age at data collection. The indirect effect of racial discrimination on CES-D scores through cigarette smoking during pregnancy was statistically significant (the standardized indirect effect = 0.03). The bootstrapping estimated 95% confidence intervals for indirect effect were 0.001 to 0.094, indicating the mediation effect was statistically significant (Bias-corrected percentile p-value for the indirect effect was 0.042). The overall hypothesized model yields χ2 to degree-of-freedom ratio =0.275/1 (p > 0.05); GFI = 1.000; NFI = 0.990; CFI = 1.000; RMSEA = 0.000; suggesting the hypothesized model fit adequately to the data (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Standardized Solutions of Path Analysis Model.

*p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. CES-D=Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression. Control variables included maternal age, level of education, and gestational age at data collection.

The dash line of pathway (cʹ) is the indirect pathway from racial discrimination to depressive symptoms through cigarette smoking (standardized indirect effect = 0.03). Bootstrap estimated 95% confidence intervals for standardized indirect effect were 0.001 to 0.094. Bias-corrected percentile p-value for the indirect effect was 0.042.

The overall hypothesized model yields χ2 to degree-of-freedom ratio =0.275/1 (p > 0.05); GFI = 1.000; NFI = 0.990; CFI = 1.000; RMSEA = 0.000.

DISCUSSION

Prior research has examined paired associations between racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and cigarette smoking but has not reported on the pathways among them overall or specifically within pregnant Black women. Racial discrimination has been related to depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women (Giurgescu et al., 2016). As noted in the introduction, the association of cigarette smoking with racial discrimination or depressive symptoms outside of pregnancy is well established, but correlations during pregnancy have been less examined, particularly within the subgroup of Black women. Pregnancy may be a period of increased vulnerability to depressive symptoms and, therefore, associations with lifetime racism may be different. As we hypothesized, cigarette smoking during pregnancy mediated the association between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women. We report in this paper that pregnant Black women who experienced racial discrimination in more situations were more likely to report cigarette smoking and higher levels of depressive symptoms. Cigarette smoking, while a negative health behavior, may be a coping strategy for women who experience racial discrimination.

We formally examined cigarette smoking as a potential mediator and found that it indeed partially mediated the association of racial discrimination with depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women in our sample. However, it is possible that cigarette smoking is an outcome of depressive symptoms. Orr et al., found that elevated levels of depressive symptoms were a risk factor for smoking among a sample of 811 pregnant Black women from North Carolina (Orr, Newton, Tarwater, & Weismiller, 2005). Women with CES-D scores ≥23 were 1.7 times (95% CI: 1.12, 2.62) more likely to smoke compared with women with CES-D scores ≤ 22 (Orr et al., 2005). Cigarette smoking may be a coping mechanism for the stress and depressive symptoms that pregnant Black women are experiencing. However, neither the study by Orr et al (2005) nor our study have longitudinally constructed data on these measures to examine whether the behavior or the depressive symptoms come first. More research is warranted on the association between depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking during pregnancy overall and among Black women, particularly with regard to causal order.

The association between cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms is complex. A recent systematic review of studies that examined the association between smoking and depressive symptoms among adults suggested two directions: (1) smoking was associated with depressive symptoms later in life, and (2) depressive symptoms were associated with smoking later in life (Fluharty et al., 2017). Cigarette smoking may be a coping mechanism to deal with stressful situations and may be used for stress relief; however, some research suggests that smoking may increase stress levels. During stressful situations, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) is activated and initiates an endocrine response to create homeostasis. Corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) is released from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PNV) in response to stress (Balkan & Pogun, 2018; Fosnocht & Briand, 2016). In turn, CRH induces adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion from the anterior pituitary cells; and ACTH stimulates cortisol release from the adrenal glands (Balkan & Pogun, 2018; Fosnocht & Briand, 2016). In addition to mediating the stress response, CRH also has an important role in nicotine addiction (Balkan & Pogun, 2018). Nicotinic receptors in the hypothalamus play a role in mediating the stress-induced activation of the HPA axis. Exposure to stressors may increase craving for cigarette smoking, and altered functions of the HPA due to smoking may increase the risk for depressive symptoms (Balkan & Pogun, 2018). Although smoking may be used to alleviate stress, it may result in tolerance to nicotine, hyperactivity of the stress system and increased risk for developing depressive symptoms which, in turn, increases smoking behavior (Bruijnzeel, 2012). Thus, the relationship between smoking and depressive symptoms is bi-directional.

Although Black women generally are less likely than White women to smoke during pregnancy (Martin, Hamilton, Osterman, Driscoll, & Drake, 2018), their higher rates of elevated depressive symptoms mean that all potential risk factors, particularly ones that may interrelate, need to be better understood. Furthermore, although national rates of prenatal smoking are low among Black women, especially compared to White women, our cohort had much higher rates of cigarette smoking in pregnancy. Among pregnant Black women in the U.S., 5.4% smoked during the first trimester and 4.5% of women smoked during the second trimester (Martin et al., 2018). We found more than 3 times that rate with 16.5% of the Black women participating in our study (8–29 weeks gestation, covering 1st and 2nd trimesters) reporting cigarette smoking during pregnancy. This is not entirely unexpected as the prevalence of smoking in Ohio and Michigan are much higher than the national average (Drake, Driscoll, & Mathews, 2018). In addition, most women enrolled in our study had a high school level of education or less, and had public insurance, both of which are factors associated with higher rates of smoking during pregnancy (Drake et al., 2018; Martin et al., 2018; Orr et al., 2005).

Racial discrimination, depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking during pregnancy have individually been related to adverse pregnancy outcomes among Black women. Cigarette smoking among Black women who experience racial discrimination and report depressive symptoms could be one of the potential pathways by which racial discrimination is related to higher rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes among these women. Cigarette smoking is an important modifiable risk factor for prevention of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Given the findings of our study, we recommend that smoking cessation programs address experiences of racial discrimination for pregnant Black women in order to increase the success of these programs.

Racism needs to be addressed on a societal level. If risks of depressive symptoms among Black women are rooted in experiences of racism, whether personally mediated, institutional, or internalized, current strategies aimed at improving their health and eliminating disparities will need to be broadened to address the influence of racism in the U.S. Pregnant Black women, church members and the community should get involved in social action to address racism, which is the root of depressive symptoms. Societal efforts to reduce racism may be more powerful in reducing smoking while simultaneously protecting pregnant Black women from stressors leading to depressive symptoms.

Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

The study has a few limitations. While prevalence of cigarette smoking during pregnancy was high, the sample was small (n=200) and thus included just 33 women (16.5%) who reported cigarette smoking during pregnancy. Women who smoked during pregnancy had a median of 4.5 cigarettes per day. Studies with a larger number of women who report smoking during pregnancy and possibly at a higher dose are needed in order to more precisely examine the associations among racial discrimination, cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women.

Our questions regarding cigarette smoking were limited. We did not ask about the types of cigarettes smoked, menthol or non-menthol, nor the behaviors associated with smoking. Being that menthol cigarettes are more addictive and specifically marketed to minority communities, this would have been an important insight. We did not ask participants why they continued to smoke during pregnancy; it could simply be an addiction behavior. Our sampled data were collected at one time during the pregnancy; therefore, trends in smoking rates across gestation could not be assessed at this time. Our non-probability sample of women was recruited from two metropolitan areas from the Midwest United States; thus, the results may not be generalizable to all pregnant Black women. Our findings were based on self-reported data which may be subject to various biases such as social desirability bias and recall bias. Moreover, cross-sectional data were used in this study; hence causal interpretations are precluded. Racial discrimination, depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking have individually been related to adverse birth outcomes. Future research is needed to fully elucidate the relationships among racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, cigarette smoking, and adverse pregnancy outcomes among Black women.

Clinical Implications

Twenty-seven percent of women in our study had CES-D scores ≥ 23, which have been correlated with depression diagnosis. These results suggest that many pregnant Black women experience depressive symptoms, and cigarette smoking is related to depressive symptoms among these women. Thus, smoking cessation programs should focus on identifying and treating depressive symptoms for pregnant women. Targeted smoking cessation programs for pregnant Black women with the highest rates of smoking and lowest utilization of smoking cessation of counseling services (e.g., lower levels of education, higher levels of depressive symptoms) are needed (Goodwin et al., 2017).

Acknowledgment:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Grant Title R01MD011575 (PI Giurgescu). We thank all the women in the study for their time and participation. There is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Balkan B, & Pogun S (2018). Nicotinic cholinergic system in the hypothalamus modulates the activity of the hypothalamic neuropeptides during the stress response. Current Neuropharmacology, 16(4), 371–387. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666170720092442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan M, Cobb S, Castro Sandoval J, & Assari S (2020). Smoking Status and Well-Being of Underserved African American Older Adults. Behav Sci (Basel), 10(4). doi: 10.3390/bs10040078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Kiefe CI, Diez-Roux AV, Williams DR, & Gordon-Larsen P (2013). Racial discrimination, racial/ethnic segregation, and health behaviors in the CARDIA study. Ethnicity and Health, 18(3), 227–243. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.713092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Monge A, Agosta J, Tobin JN, Cassells A, Stanton C, & Schwartz J (2015). Perceived ethnic discrimination and cigarette smoking: examining the moderating effects of race/ethnicity and gender in a sample of Black and Latino urban adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(4), 689–700. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9645-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel AW (2012). Tobacco addiction and the dysregulation of brain stress systems. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(5), 1418–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez TP, Dunkel-Schetter C, Glynn LM, Hobel C, & Sandman CA (2008). Racial differences in birth outcomes: The role of general, pregnancy, and racism stress. Health Psychology, 27(2), 194–203. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18377138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2868586/pdf/nihms189112.pdf.

- Drake P, Driscoll AK, & Mathews MS (2018). Cigarette smoking during pregnancy: United States, 2016. Retrieved from Hyattsville, MD: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M, & Munafò MR (2017). The Association of Cigarette Smoking With Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 19(1), 3–13. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosnocht AQ, & Briand LA (2016). Substance use modulates stress reactivity: Behavioral and physiological outcomes. Physiology and Behavior, 166, 32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giurgescu C, Engeland CG, Templin TN, Zenk SN, Koenig MD, & Garfield L (2016). Racial discrimination predicts greater systemic inflammation in pregnant African American women. Applied Nursing Research, 32, 98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Cheslack-Postava K, Nelson DB, Smith PH, Wall MM, Hasin DS, Galea S (2017). Smoking during pregnancy in the United States, 2005–2014: The role of depression. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 179, 159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corporation, I. S. M. V. A, NY: IBM Corporation. ftp://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/documentation/statistics/24.0/en/client/Manuals/IBM_SPSS_Missing_Values.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N (1990). Racial and gender discrimination: Risk factors for high blood pressure? Social Science and Medicine, 30(12), 1273–1281. Retrieved from PM:2367873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Carney D, Lancaster K, Waterman PD, Kosheleva A, & Banaji M (2010). Combining explicit and implicit measures of racial discrimination in health research. American Journal of Public Health, 100(8), 1485–1492. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, & Sidney S (1996). Racial discrimination and blood pressure: The CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. American Journal of Public Health, 86(10), 1370–1378. Retrieved from PM:8876504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1380646/pdf/amjph00521-0028.pdf.

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, & Barbeau EM (2005). Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science and Medicine, 61(7), 1576–1596. Retrieved from PM:16005789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludman EJ, Curry SJ, Grothaus LC, Graham E, Stout J, & Lozano P (2002). Depressive symptoms, stress, and weight concerns among African American and European American low-income female smokers. Psychol Addict Behav, 16(1), 68–71. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.16.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, & Drake P (2018). Births: Final data for 2017. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxson PJ, Edwards SE, Ingram A, & Miranda ML (2012). Psychosocial differences between smokers and non-smokers during pregnancy. Addictive Behaviors, 37(2), 153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra DP, Strobino D, & Trabert B (2010). Effects of social and psychosocial factors on risk of preterm birth in Black women. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 24(6), 546–554. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-78349278458&partnerID=40&md5=e77e56aeb02d1f002332f270d118f2d7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Trepka MJ, Pierre-Victor D, Bahelah R, & Avent T (2016). Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Antenatal Depression in the United States: A Systematic Review. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(9), 1780–1797. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-1989-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr ST, Blazer DG, James SA, & Reiter JP (2007). Depressive symptoms and indicators of maternal health status during pregnancy. Journal of Women’s Health, 16(4), 535–542. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-34250769368&partnerID=40&md5=f79d9981007e7344c84b27eb3e1ce0fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr ST, Newton E, Tarwater PM, & Weismiller D (2005). Factors associated with prenatal smoking among Black women in Eastern North Carolina. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 9(3), 245–252. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-33644759622&partnerID=40&md5=f828d9b029af62beae2669b8dff50841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, Gee G (2015). Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 10(9). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plascak JJ, Hohl B, Barrington WE, & Beresford SA (2018). Perceived neighborhood disorder, racial-ethnic discrimination and leading risk factors for chronic disease among women: California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2013. SSM - Population Health, 5, 227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber J (2017). Update to core reporting practices in structural equation modeling. Res Soc Admin Pharm, 13(3), 634–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter-Acey J, Sealy-Jefferson S, Helmkamp L, Caldwell CH, Osypuk TL, Platt RW, Misra DP (2016). Racism in the form of micro aggressions and the risk of preterm birth among black women. Annals of Epidemiology, 26(1), 7–13.e.11. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter-Acey J, Talley LM, Stevenson HC, & Misra DP (2019). Personal Versus Group Experiences of Racism and Risk of Delivering a Small-for-Gestational Age Infant in African American Women: a Life Course Perspective. Journal of Urban Health, 96(2), 181–192. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0291-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]