Abstract

The Gemini imidazoline surfactants were synthesized from a series of saturated fatty acids. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), polarization curve, and quantum chemistry methods were used to study the corrosion inhibition behavior of Gemini imidazoline surfactants for X70 carbon steel in NaCl solution. Results reveal that such kind of surfactants has an outstanding inhibition effect on carbon steel X70 in NaCl solution and that the restrained efficiency of Gemini imidazoline in an alkaline solution is better than that in a neutral solution. The shorter the carbon chain length, the higher the suppressive efficiency. The higher the concentration of Gemini imidazoline surfactant, the better the inhibition effect.

1. Introduction

Metal corrosion has brought huge economic loss and environmental impact to various fields, such as chemical industries, oilfield resources, water treatment plants, etc. The problem is widespread in the world, and the harm has seriously affected some infrastructure construction.1,2 Carbon steel is widely used in pipelines in oil and natural gas industries,3 but the interaction between carbon steel and surrounding media can lead to metal damage or deterioration. Corrosion is a prominent problem in oilfield development.4,5 Among various corrosion inhibition methods, corrosion inhibitors are widely used because of their economy, high efficiency, and strong adaptability.6 Generally, these inhibitors contain heteroatoms (such as nitrogen, sulfur, oxygen, phosphorus), unsaturated bonds, or aromatic inhibitors with planar conjugated structures.7−10 Corrosion inhibitors can be adsorbed to the metal surface by the so-called physical adsorption or chemical adsorption and form a protective layer to prevent metal corrosion in a corrosive environment.11,12 The former involves electrostatic attraction between a charged metal surface and an oppositely charged inhibitor, while the latter requires charge sharing or charge transfer of lone pairs or π electrons from the conjugated part of the inhibitor molecule to the vacant d orbital on the metal surface. In addition, for aromatic systems, π* orbitals can also accept electrons from d-orbitals of iron to form feedback bonds, thus producing multiple chemisorption centers. A surfactant is a kind of typical and efficient corrosion inhibitor. Because of its amphiphilic structure, it can be easily adsorbed at the metal/solution interface, change the charge distribution and interface properties of the metal, replace water molecules, form a protective layer, and block the active parts exposed to corrosion media, thereby reducing the corrosion of carbon steel.13−16

Imidazoline inhibitor has become one of the most studied inhibitors in recent years due to its excellent performance. It has the advantages of low toxicity, no irritating smell, and good thermal stability. Besides, nitrogen positive ions and the metal surface generate covalent adsorption so that the corrosion inhibitor molecules are firmly adsorbed on the metal surface and form a dense hydrophobic film, which effectively blocks the contact between corrosion media and the metal surface. It has excellent corrosion inhibition performance.17−19 Imidazoline surfactant has been applied to metal materials for corrosion protection. The study shows that it has a good corrosion inhibition effect. Gemini imidazoline surfactants have higher surface tension and lower critical micelle concentration (CMC) than the corresponding monomers due to their two hydrophilic end groups and two hydrophobic long chains in their structure. Bunton,20 Zana,21 Menger,22 Rosen,23 Zhao,24 Wang,25 and Feng26 have reported many original studies. The application of Gemini surfactant in corrosion inhibition has attracted much attention from researchers.27−30 Yin31 group studied the inhibition effect of cationic Gemini surfactants with different chain lengths on carbon steel in 1 M HCl solution by means of a weight loss method, potentiodynamic polarization method, and electrochemical impedance method. It is found that the carbon chain length of Gemini surfactant has little effect on the inhibition at low concentrations. Cheng et al.32 studied the corrosion inhibition performance of two new Gemini corrosion inhibitors that contain multifunctional groups on X-65 pipeline steel produced water in a CO2-saturated oilfield. The results show that the corrosion inhibition effect of the applied corrosion inhibitor is more effective than that of the newly prepared steel electrode. Migahed33 studied the effect of three new ionic liquid-based Gemini imidazoline indicator compounds (I, II, and III) on the corrosion inhibition of X-65 Carbon Steel Tubing in a harsh environment. It was shown that the concentration and the length of the spacer of the inhibitor have an influence on the inhibition efficiency. Zhou34 and his research group studied the corrosion inhibition behavior of Gemini imidazoline surfactants for A3 carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solution with approaches of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), polarization curve, weight loss measurement, and quantum chemistry study. The results indicate that Gemini imidazoline surfactant has better corrosion inhibition performance than its monomer under the same conditions.

In the present work, the most suitable pH of the environment for Gemini imidazoline surfactants (GISs) to exert the inhibition effect has been explored. At the same time, the influence of structure and concentration of GIS on its suppressive effect has also been investigated. A series of imidazoline quaternary ammonium cationic Gemini surfactants are synthesized from perspectives of fatty acids, diethylenetriamine (DETA), and modifier 1,3-dibromopropane, and their potential polarization curves and electrochemical impedance have been measured. The inhibition effect of GIS is evaluated by an experimental study, and its possible inhibition mechanism will be explained by quantum chemical calculations.

2. Experimental Method

2.1. Materials and Main Instruments

2.1.1. Materials

Saturated fatty acids with different carbon chain lengths (stearic acid, palmitic acid, myristic acid, lauric acid, and oleic acid), NaCl, diethylenetriamine (DETA), xylene, zinc power, dimethyl-carbonate, 1,3-dibromopropane, and acetone were purchased from Adamas. All of these reagents are of analytical reagent (AR) grade.

2.1.2. Main Instruments

An ALPHA Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrometer, a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer, an electrochemical workstation (CHI600E), a motor agitator, and a digital display constant-temperature oil bath pot were used.

2.2. Synthetic Methodology

The synthesis of GIS was carried out with various fatty acids of different carbon chain lengths. The synthesis route of GIS is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Synthesis route of GIS.

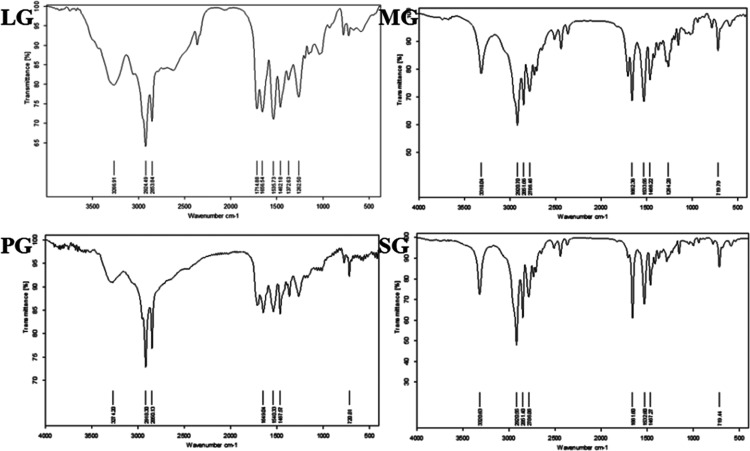

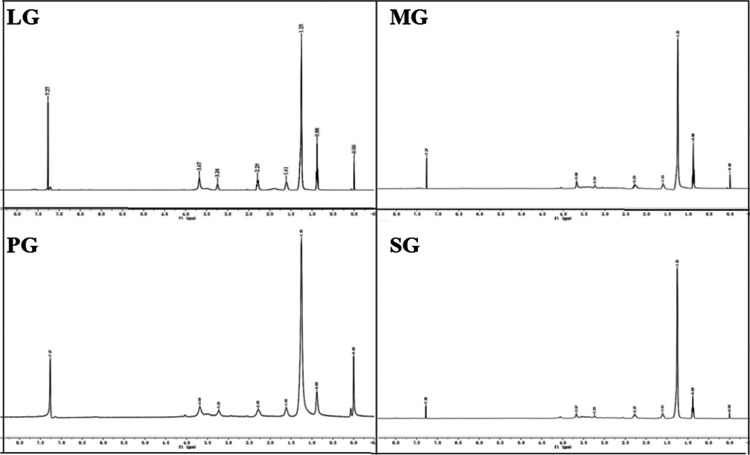

The product is khaki solid, which is a Gemini imidazolinium surfactant. The synthetic GISs are measured by ALPHA FT-IR and NMR spectrometers. FT-IR and 1H NMR spectra of GIS are given in Figures 2 and 3. (LG, MG, PG, and SG are the GISs based on lauric acid, myristic acid, palmitic acid, and stearic acid, respectively.35)

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of the GIS.

Figure 3.

1H NMR spectra of the GIS.

In Figure 2, FT-IR peaks at 1650–1665 cm–1 confirm the preparation of the imidazoline ring. The peaks at 2920–2700 cm–1 are saturated −CH bonds. The presence of peaks at 730–760 cm–1 confirms the quaternization of the ring, and peaks at 3320–3275 cm–1 correspond to NH str- of an amide linkage.

In Figure 3, 1H NMR peaks at 7.27 ppm correspond to the proton peak of solvent deuterium chloroform. The proton peak of −CH3 at 0.88 ppm, the proton peak of −CH2 in the middle of the alkyl chain at 1.25 ppm, the proton peak of −CH2– in the imidazoline ring at 1.61 ppm, and the proton peak of −CH2– in the imidazoline ring at 2.29 ppm. The proton peak of N+–CH2 is at 3.67 ppm. The proton peak of −CH2– in the branched chain is at 3.24 ppm.

2.3. Electrochemical Test

The main test system is an electrochemical workstation. Three electrode devices are adopted through an electrochemical workstation. A platinum electrode is used as an auxiliary electrode (CE), a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as a reference electrode (RE), and a pure carbon steel X70 electrode (d = 2.0 mm, Puratronic, Alfa Aesar, 99.999%) as a working electrode (WE). Sandpapers of 200 mesh, 600 mesh, and 2000 mesh were used to polish the electrode surface. The effective area of the working electrode is 0.0314 cm2. During the test, the working electrode is put into the corrosion media that add different concentrations of corrosion inhibitor or nothing. The polarization scanning rate is 1 mV s–1, and the scanning voltage range is −1 to 1 V. All potentials reported in this paper are referred to as SCE. The concentration of NaCl is 3.5% M (the main component of simulated seawater solution).

Equipment related to oil and gas storage and transportation is often used in seawater environments. Therefore, our research group select 3.5% M NaCl solution and commonly used carbon steel X70 as the research objects and study the corrosion effect of NaCl solution on X70 carbon steel from multiple angles.

The chemical composition of X70 carbon steel is 0.16% C, 0.45% Si, 1.70% Mn, 0.02% P, 0.01% S, 0.06% V, 0.06% Nb, 0.06% Ti, and 0.35% Mo, and the other main component is iron.

The corrosion inhibition efficiency (%) can be calculated by the following equation.27,28

In this equation, icorr0 and icorr are respectively the current density corresponding to the blank copper electrode and the copper electrode covered with the imidazoline film. The inhibition efficiency also can be calculated using the polarization resistance from the following equation27,28

where RP and RP0 are the polarization resistance values with and without n-Bpys, respectively.

2.4. Quantum Chemical Calculations

The quantum chemical calculations are carried out using the Gaussian 09 program.34 Geometry optimization, the highest occupied molecular energy (EHOMO), and the lowest unoccupied molecular energy (ELUMO) are characterized at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) basis18,19 without any symmetry constraint.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of pH and Carbon Chain Length

Figure 4 shows that the Tafel and EIS plots for the X70 carbon steel electrodes with and without GIS are obtained in 3.5% M NaCl solution (pH = 5, 7, and 9). The electrochemical parameters obtained by fitting polarization curves and impedance curves with the extrapolation method are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 4.

Polarization and impedance curves of GIS with different carbon chain lengths for pH = 5, 7, 9.

Table 1. Electrochemical Parameters and Inhibition Efficiencies Obtained by Polarization Curves of the X70 Electrode in NaCl Solutions with pH = 5, 7, and 9.

| pH | inhibitors | –Ecorr (mV) | ba (mV dec–1) | –bc (mV dec–1) | Icorr (μA cm–2) | η (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | blank | 0.85 | 10 | 13 | 19.22 | |

| LG | 0.67 | 24 | 18 | 8.15 | 57.60 | |

| MG | 0.70 | 27 | 27 | 9.42 | 50.99 | |

| PG | 0.71 | 26 | 23 | 10.03 | 47.82 | |

| SG | 0.77 | 14 | 20 | 12.30 | 35.99 | |

| 7 | blank | 0.76 | 21 | 16 | 7.09 | |

| LG | 0.65 | 19 | 15 | 2.88 | 59.34 | |

| MG | 0.67 | 18 | 10 | 3.31 | 53.32 | |

| PG | 0.69 | 16 | 17 | 3.54 | 49.98 | |

| SG | 0.75 | 15 | 12 | 4.46 | 37.03 | |

| 9 | blank | 0.75 | 12 | 14 | 13.97 | |

| LG | 0.60 | 24 | 10 | 3.83 | 72.59 | |

| MG | 0.64 | 20 | 16 | 5.54 | 60.33 | |

| PG | 0.65 | 16 | 15 | 6.17 | 55.84 | |

| SG | 0.67 | 20 | 16 | 7.31 | 47.65 |

Table 2. Electrochemical Parameters and Inhibition Efficiencies Obtained by Impedance Curves of the X70 Electrode in NaCl Solutions with pH = 5, 7, and 9.

|

Cdl |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | inhibitors | Rp (Ω cm2) | Y0 (Ω–1 cm–2 Sn) | n | η (%) |

| 5 | blank | 3.01 × 103 | 1.71 × 10–4 | 0.282 | |

| LG | 2.30 × 104 | 6.87 × 10–1 | 0.710 | 86.91 | |

| MG | 2.27 × 104 | 2.43 × 10–4 | 0.648 | 86.74 | |

| PG | 2.01 × 104 | 2.42 × 10–4 | 0.547 | 85.02 | |

| SG | 1.19 × 104 | 5.94 × 10–5 | 0.515 | 74.71 | |

| 7 | blank | 3.88 × 103 | 4.95 × 10–5 | 0.624 | |

| LG | 2.98 × 104 | 3.98 × 10–5 | 0.741 | 86.97 | |

| MG | 2.46 × 104 | 7.19 × 10–5 | 0.673 | 84.23 | |

| PG | 1.99 × 104 | 7.83 × 10–5 | 0.641 | 80.50 | |

| SG | 1.82 × 104 | 2.52 × 10–4 | 0.599 | 78.68 | |

| 9 | blank | 8.05 × 103 | 4.95 × 10–5 | 0.715 | |

| LG | 8.91 × 104 | 1.83 × 10–4 | 0.674 | 90.95 | |

| MG | 7.16 × 104 | 6.84 × 10–5 | 0.686 | 88.75 | |

| PG | 4.23 × 104 | 1.81 × 10–4 | 0.598 | 80.96 | |

| SG | 3.79 × 104 | 1.37 × 10–4 | 0.576 | 78.75 | |

It can be clearly seen from Figure 4 that when four kinds of Gemini imidazoline surfactants with the same concentration are tested in NaCl solution with the same pH value, the shorter the carbon chain length, the more positive the Tafel curve; the higher the capacitance arc of the EIS curve, the better the corrosion inhibition effect. When the concentration of the inhibitor and the length of the carbon chain remain unchanged, the solution with pH 9 has higher inhibition efficiency and better inhibition effect.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is used to study X70 carbon steel in NaCl solution without adding imidazoline surfactant and with adding imidazoline surfactant with different carbon chain lengths. In the frequency range of measurement, the Nyquist impedance consists of two parts: a high-frequency concave semicircle with the center below the real axis and a straight line at the low frequency. Generally, since the solubilizer of reactants or products diffuses to the surface of carbon steel, the straight line at low frequency is considered as the Waugh impedance,36 and the high-frequency semicircle is referred to charge-transfer resistance (Rct) and double-layer capacitance (Cdl).37 Larger-capacitance circuits mean higher charge-transfer resistance, indicating that carbon steel is more resistant to corrosion.37 With a decrease of the elastic chain length of imidazoline surfactant, the diameter of the high-frequency capacitance circuit increases in turn, which indicates that the corrosion reaction is inhibited and the carbon steel electrode cannot be eroded by the corrosive agent easily. Generally, the inhibition of corrosion inhibitors is achieved by adsorption of inhibitors on the surface of carbon steel, and a nonconductive layer is formed on the surface of carbon steel.17 Imidazoline surfactants containing imidazoline rings interact with unsaturated d-orbitals of iron atoms on the surface of the carbon steel electrode through coordination bonds. The adsorption of imidazoline surfactant on the electrode surface can effectively protect the electrode from corrosive ions, thus slowing down the corrosion rate.

It can be seen from Figure 4 that the diameter of the capacitance ring of LG is significantly larger than those of Mg, PG, and SG, indicating that the corrosion inhibition performance of LG with a shorter carbon chain length is better. The reason is that the inhibition performance of an organic corrosion inhibitor is closely related to its water solubility. The good water solubility of the corrosion inhibitor is the premise of its adsorption at the metal–water solution interface. When the concentration of the corrosion inhibitor is the same, the shorter the carbon chain length, the better the water solubility, and the greater the adsorption capacity of the inhibitor on the metal surface, the better the corrosion inhibition performance.20 At the same time, the molecular structure is also an important factor affecting the corrosion inhibition performance. Due to the synergistic effect of short carbon chain molecules at the same concentration, a stable low-energy conformation can be formed and adsorbed to the metal surface to inhibit the corrosion reaction.21 However, a long carbon chain inhibitor is more difficult to be adsorbed to the surface of the X70 carbon steel electrode due to the competition among carbon chains, high energy, unstable adsorption, and difficult coordination in molecular direction.

3.2. Influence of Concentration of Inhibitors

The inhibition effect of lauric Gemini (LG) imidazoline surfactant with different concentrations (100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 mg L–1) on X70 carbon steel is studied in NaCl solution when pH is 9 and other conditions are unchanged. As shown in Figure 5, with an increase of LG concentration in solution from 100 to 500 mg L–1, there is an increase in both the corrosion current density and the corrosion inhibition efficiency, and polarization curves move forward. Since LG is a good surfactant and there may be a critical micelle concentration in NaCl solution, when the concentration reaches 500 mg L–1, the inhibition efficiency decreases slightly. The electrochemical parameters are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Figure 5.

Polarization and impedance curves for LG systems.

Table 3. Electrochemical Parameters and Inhibition Efficiencies Obtained from Polarization Curves for Carbon Steel with Different Concentrations of LG in NaCl Solution at pH 9.

| inhibitors | C (mg L–1) | –Ecorr (mV) | ba (mV dec–1) | –bc (mV dec–1) | Icorr (μA cm–2) | η (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG | 100 | 0.74 | 13 | 10 | 9.97 | 28.62 |

| 200 | 0.68 | 19 | 15 | 6.79 | 51.35 | |

| 300 | 0.65 | 18 | 14 | 5.24 | 62.45 | |

| 400 | 0.60 | 24 | 10 | 3.83 | 72.59 | |

| 500 | 0.62 | 25 | 55 | 4.36 | 68.77 |

Table 4. Electrochemical Parameters and Inhibition Efficiencies Obtained from Impedance Curves for Carbon Steel with Different Concentrations of LG in NaCl Solution at pH 9.

|

Cdl |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inhibitors | C (mg L–1) | Rp (Ω cm2) | Y0 (Ω–1 cm–2 Sn) | n | η (%) |

| LG | 100 | 1.82 × 104 | 7.52 × 10–5 | 0.684 | 55.76 |

| 200 | 2.26 × 104 | 1.41 × 10–4 | 0.721 | 64.38 | |

| 300 | 2.46 × 104 | 1.84 × 10–4 | 0.741 | 67.27 | |

| 400 | 8.91 × 104 | 1.83 × 10–4 | 0.674 | 90.95 | |

| 500 | 3.28 × 104 | 2.24 × 10–4 | 0.711 | 75.45 | |

Compared with the polarization curves, the corrosion current density, corresponding to the cathodic reaction and anodic reaction, is reduced by adding LG with low concentration, indicating that the corrosion inhibition effect is relatively high. Due to the nonconductive and hydrophobic properties of surfactants, the surfactants adsorbed on the metal surface change the corrosion resistance of metals. The former prevents electrons from passing through the interface, while the latter forms a protective adsorption layer to protect the surface of carbon steel from the influence of corrosive solution.25 The inhibition performance of LG depends on the interaction between the positive charge of the imidazoline ring in LG and the negative charge of X70 carbon steel, and the surface of carbon steel is covered by LG to form an adsorption layer.

Moreover, the charge transfer from the LG imidazoline ring to X70 carbon steel enhances the electron density at the anode on the surface of carbon steel, while the reverse electron transport of metal to LG reduces the electron density at the cathode on the surface of X70 carbon steel, which greatly improves the corrosion inhibition performance.

In addition, the corrosion current density decreased with an increase of LG content. It can be seen from Table 3 that the inhibition efficiency increases from 28.62 to 72.59% with an increase of LG concentration from 100 to 400 mg L–1. The impedance curve data in Table 4 also confirmed this point: with an increase of LG concentration, the inhibition efficiency increased from 55.76 to 90.95%. The inhibition efficiency of film-forming inhibitor demonstrates that with an increase of inhibitor concentration in solution, the adsorption amount of corrosion inhibitor on metal surface increases, the film-forming effect increases, and the slow-release effect becomes better. However, the inhibition efficiency starts to decrease when the LG concentration exceeds 400 mg L–1.

3.3. Quantum Chemical Calculations

As we all know, ΔE, the difference between ELUMO and EHOMO, is usually used to predict adsorption centers and corrosion inhibition efficiency of the inhibitors on metal surfaces. In the frontier orbital theory, the ability of electron transition from HOMO to the potential acceptor increases with the value of EHOMO, and the value of ELUMO shows the capability of accepting electrons for the LUMO. Thus, to research the different inhibition processes of LG, MG, PG, and SG, the frontier orbitals of them were obtained by the Gaussian 09 program at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) basis, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Frontier Orbital Energies of GIS.

| surfactants | ELUMO (eV) | EHOMO (eV) | ΔE (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LG | –0.25681 | –0.37474 | 0.11793 |

| MG | –0.25671 | –0.36159 | 0.10488 |

| PG | –0.25659 | –0.35097 | 0.09438 |

| SG | –0.25652 | –0.34280 | 0.08628 |

From Table 5, both EHOMO and ELUMO for GIS decrease when the carbon chain length shortens; for example, the values of EHOMO and ELUMO for SG are −0.25652 and −0.34280 eV, while those of LG are −0.25681 and −0.37474 eV, respectively. The GIS with a shorter carbon chain can act as the potential electron acceptor, and the GIS with a longer carbon chain can act as the electron donor. As shown in Figure 6, the HOMOs are spread over the alkyl chain, and the LUMOs are mainly distributed in the imidazoline ring. It is noted that the ΔE values of GISs with longer carbon chains is less than that of the GISs with shorter carbon chains, meaning that the GISs with shorter carbon chains own higher reaction activity, stronger interaction with X70 carbon steel, and higher protective efficiency than the GISs with longer carbon chains.

Figure 6.

Electron distribution in the HOMO and LUMO for LG.

As mentioned above, the distribution of the HOMO and LUMO can form multiadsorption centers for the adsorption of GIS on the surface of carbon steel X70 electrodes. The nitrogen atom in the imidazoline ring of imidazoline surfactants can provide electrons for iron on the surface of X70 carbon steel. The distribution of the outer electrons of Fe is 4s23d6, which is favorable for the transfer of electrons from HOMO of imidazoline surfactants to Fe 3d vacancy orbitals to form coordination bonds. The feedback bond is formed by the interaction between the electrons in the Fe occupied 3d orbitals and the LUMO orbitals of imidazoline surfactants. It is conducive to the coordination bond formed by electron transfer from imidazoline surfactant to the vacancy orbit of carbon steel, and the interaction of imidazoline surfactant on carbon steel occupied orbit and antibond orbit to form feedback bond, which improves the adsorption stability of surfactant molecules on the carbon steel surface. Therefore, imidazoline surfactant has a high corrosion inhibition effect.

4. Conclusions

The protective effects of Gemini imidazoline surfactants with different carbon chain lengths on the surface of X70 carbon steel are compared by polarization, EIS, and quantum chemical calculations. The results show that a surfactant with a shorter carbon chain length has a better corrosion inhibition effect under the same conditions. At the same time, the inhibition effect of Gemini imidazoline surfactant increases with an increase of its concentration. Increasing the concentration of the corrosion inhibitor to a certain critical value can improve the coverage rate of the corrosion inhibitor on the metal surface to protect the metal effectively. The results of quantum chemistry calculations show that imidazoline surfactants have high reactivity and reaction centers are distributed on the imidazoline ring. LG has a shorter carbon chain length, higher reaction activity, stronger interaction with carbon steel, and higher protection efficiency. The results show that LG has a good corrosion inhibition effect on carbon steel in NaCl solution. This study provides basic data for the corrosion inhibition performance of Gemini imidazoline surfactants and has certain theoretical significance for the design and development of new imidazoline inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This work has received support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21703194), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (20CX05015A), and the Special Fund for Promoting Scientific and Technological Innovation of Xuzhou (KC17080). An amount of computing time from Shandong University is also acknowledged.

Author Contributions

§ W. Zhuang and X.W. contributed to the work equally and should be regarded as co-first authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Li G.; Bae Y.; Mishra A.; Giammar D. E.; et al. Effect of Aluminum on Lead Release to Drinking Water from Scales of Corrosion Products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6142. 10.1021/acs.est.0c00738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel M. L.; Necib S.; Daumas S.; Labat M.; Blanc C.; Foy E.; Linard Y. Corrosion at the carbon steel-clay borehole water interface under anoxic alkaline and fluctuating temperature conditions. Corros. Sci. 2018, 136, 70–90. 10.1016/j.corsci.2018.02.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M. C.; Yang K.; Xiao F. R.; Shan Y. Y. Continuous cooling transformation of undeformed and deformed low carbon pipeline steels. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 2003, 355, 126–136. 10.1016/S0921-5093(03)00074-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panossian Z.; Almeida N. L.; Sousa M. F. R.; Pimenta G. D. S.; Marques L. B. S. Corrosion of carbon steel pipes and tanks by concentrated sulfuric acid: A review. Corros. Sci. 2012, 58, 1–11. 10.1016/j.corsci.2012.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Usher K. M.; Kaksonen A. H.; Cole I.; et al. Microbially influenced corrosion of buried carbon steel pipes. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 93, 84–106. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2014.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finšgar M.; Jackson J. Application of corrosion inhibitors for steels in acidic media for the oil and gas industry:A review. Corros. Sci. 2014, 86, 17–41. 10.1016/j.corsci.2014.04.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. H.; He Q.; Zhang S. T.; Pei C. L.; Hou B. R. Some new triazole derivatives as inhibitors for mild steelcorrosion in acidic medium. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2008, 38, 289–295. 10.1007/s10800-007-9437-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solmaz R.; Kardas G.; Yazıcı B.; Erbil M. Adsorption and corrosion inhibitive properties of 2-amino-5-mercapto-1,3,4-thiadiazole on mild steel in hydrochloric acid media. Colloids Surf., A 2008, 312, 7–17. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2007.06.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kokalj A.; Peljhan S.; Finšgar M.; Milosev I. What determines the inhibition effectiveness of ATA, BTAH, and BTAOH corrosion inhibitors on copper. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16657–16668. 10.1021/ja107704y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukul D.; Pal A.; Saha S. K.; Satpa S.; Adhikari U.; Banerjee P. Newly synthesized quercetin derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in 1 M HCl: combined experimental and theoretical investigation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 6562–6574. 10.1039/C7CP06848D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negm N. A.; Ghuiba F. M.; Tawfik S. M. Novel isoxazolium cationic Schiff base compounds as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in hydrochloric acid. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 3566–3575. 10.1016/j.corsci.2011.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behpour M.; Ghoreishi S. M.; Soltani N.; Salavati-Niasari M.; Hamadanian M.; Gandomi A. Electrochemical and theoretical investigation on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel by thiosalicy-laldehyde derivatives in hydrochloric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 2172–2181. 10.1016/j.corsci.2008.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Migahed M. A.; Shaban M. M.; Fadda A. A.; Ali T. A.; Negm N. A. Synthesis of some quaternary ammonium gemini surfactants and evaluation of their performance as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in oil well formation water containing sulfide ions. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 104480–104492. 10.1039/C5RA15112K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menger F. M.; Keiper J. S. Gemini surfactants. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 1906–1920. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zana R. Dimeric and oligomeric surfactants. Behavior at interfaces and in aqueous solution: a review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 97, 205–253. 10.1016/S0001-8686(01)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heakal F. E.-T.; Elkholy A. E. Gemini surfactants as corrosioninhibitors for carbon steel. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 230, 395–407. 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.01.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raja P. B.; Sethuraman M. G. Natural products as corrosion inhibitor for metals in corrosive media—A review. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 113–116. 10.1016/j.matlet.2007.04.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. H.; Bierwagen G. P. Sol–gel coatings on metals for corrosion protection. Prog. Org. Coat. 2009, 64, 327–338. 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2008.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montemor M. F. Functional and smart coatings for corrosion protection: A review of recent advances. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 258, 17–27. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2014.06.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bunton C. A.; Robinson L.; Schaak J.; Stam M. F. Catalysis of nucleophilic substitutions by micelles of dicationic detergents. J. Org. Chem. 1971, 36, 2346–2350. 10.1021/jo00815a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zana R. Dimeric (Gemini) surfactants: Effect of the spacer group on the association behavior in aqueous solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 248, 203–220. 10.1006/jcis.2001.8104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menger F. M.; Keiper J. S. Gemini surfactant. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 1906–1920. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L. D.; Rosen M. J. Surface properties, micellization, and premicellar aggregation of Gemini surfactants with rigid and flexible spacers. Langmuir 1996, 12, 1149–1153. 10.1021/la950508t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pei X. M.; Zhao J. X.; Ye Y. Z.; You Y.; Wei X. L. Wormlike micelles and gels reinforced by hydrogen bonding in aqueous cationic Gemini surfactant systems. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 2953–2960. 10.1039/c0sm01071e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y. X.; Han Y. C.; Wang Y. L. Effects of molecular structures on aggregation behavior of Gemini surfactants in aqueous solutions. Acta Phys.–Chim. Sin. 2016, 32, 214–226. 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201511022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. J.; Chu Z. L. pH-Tunable wormlike micelles based on an ultra-long-chain “pseudo” Gemini surfactant. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 4614–4620. 10.1039/C5SM00677E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heakal F. E.; Elkholy A. E. Gemini surfactants as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 230, 395–407. 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.01.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal M. S. A review of Gemini surfactants: Potential application in enhanced oil recovery. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2016, 19, 223–236. 10.1007/s11743-015-1776-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hegazy M. A.; Azzam E. M. S.; Kandil N. G.; Badawi A. M.; Sami R. M. Corrosion inhibition of carbon steel pipelines by some new amphoteric and Di-cationic surfactants in acidic solution by chemical and electrochemical methods. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2016, 19, 861–871. 10.1007/s11743-016-1824-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. M.; Duan H. B.; Jiang R. J. Synergistic corrosion inhibition effect of quinoline quaternary ammonium salt and Gemini surfactant in H2S and CO2 saturated brine solution. Corros. Sci. 2015, 91, 108–119. 10.1016/j.corsci.2014.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L. W.; Yin C. X.; Zhang H. L.; Li Y. F.; Song X. H.; Chen Q. B.; Liu H. L. Cationic Gemini Surfactants with a Bipyridyl Spacer as Corrosion Inhibitors for Carbon Steel. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 18990–18999. 10.1021/acsomega.8b03043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H. W.; Cheng Y. F. Novel Inhibitors Containing Multi-Functional Groups for Pipeline Corrosion Inhibition in Oilfield Formation Water. Corrosion 2016, 72, 472–485. 10.5006/1875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Migahed M. A.; EL-Rabiei M. M.; Nady H.; Elgendy A.; Zaki E. G.; Abdou M. I.; Noamy E. S. Novel Ionic Liquid Compound Act as Sweet Corrosion Inhibitors for X-65 Carbon Tubing Steel: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. J. Bio- Tribo-Corros. 2017, 3, 31 10.1007/s40735-017-0092-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T.; Yuan J.; Chen Y. J.; Xin X.; Tan Y. B.; Xu G. Y. The comparison of imidazolium Gemini surfactant C14-4-C14imBr2 and its corresponding monomer as corrosion inhibitors for A3 carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solutions: Experimental and quantum chemical studies. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2017, 20, 529. 10.1007/s11743-017-1931-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy D. B.; Mishra A. Convenient synthesis, characterization and surface active properties of novel cationic gemini surfactants with carbonate linkage based on C12–C18 sat./unsat. fatty acids. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 2017, 24, 1–10. 10.1016/j.jart.2016.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang Y. J.; Zhang S. T.; Guo L.; Zheng X. W.; Xiang B.; Chen S. J. Experimental and theoretical studies of four allyl imidazolium-basedionic liquids as green inhibitors for copper corrosion in sulfuric acid. Corros. Sci. 2017, 119, 68–78. 10.1016/j.corsci.2017.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H. Y.; Yang C.; Chen S. H.; Jiao Y. L.; Huang S. X.; Li D. G.; Luo J. L. Electrochemical investigation of dynamic interfacial processes at 1-octadecanethiol-modified copper electrodes in halide-containing solutions. Electrochim. Acta 2003, 48, 4277–4289. 10.1016/j.electacta.2003.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]