Abstract

Diarylureas are widely used in self-assembly and supramolecular chemistry owing to their outstanding characteristics as both H-bond donors and acceptors. Unfortunately, this bonding property is rarely applied in the development of urea-containing drugs. Herein, seven related dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) complexes were screened from 12 substrates involving sorafenib and regorafenib, mainly considering the substitution effect following a robust procedure. All complexes were structurally confirmed by spectroscopic means and thermal analysis. Specially, five cocrystals with three deuterated, named sorafenib·DMSO, donafenib·DMSO, deuregorafenib·DMSO, 6·DMSO, and 7·DMSO were obtained. The crystal structures revealed that all host molecules consistently bonded with DMSO in intermolecular interaction in a 1:1 stoichiometry. However, further comparison with documented DMSO complexes and parent motifs presented some arrangement diversities especially for 6·DMSO which offered a counter-example to previous rules. Major changes in the orientation of meta-substituents and the packing stability for sorafenib·DMSO and deuregorafenib·DMSO were rationalized by theory analysis and computational energy calculation. Cumulative data implied that the planarization of two aryl planes in diarylureas may play a crucial role in cocrystallization. Also, a polymorph study bridged the transformation between these ureas and their DMSO complexes.

Introduction

Diarylureas are frequently used in self-assembly, anion recognition, and cocrystallization as they can act as both H-bond donors through their double NH units and acceptors by the urea C=O group.1−4 Etter has summarized complexing rules for diphenylureas taking 1,3-bis(m-nitrophenyl)urea as the model substrate in the early 1990s.5,6 The major conclusion is that diarylureas with strong meta-substituted electron-withdrawing substituents have the property to bond with strong acceptor solvents or reagents such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) in a 1:1 stoichiometry.6−8 Later studies found that diarylureas could also recognize various anions including acid radicals, halides, and metal ions.9−14 Yamasaki et al. recently reported the formation of a diphenylurea cocrystal between different diphenylureas.15 In addition, the introduction of heteroaromatic substitutions (e.g., pyridine)16,17 and more H-bond donors or acceptors (e.g., NO2, pyrrole, I, F)18−21 in aromatic units would afford more diverse packing patterns. At the same time, Nanjia, Swift, and co-workers made great efforts to predict the cocrystallization and possible assembly styles from substitution environment, electronic effects, and with the help of computational energy calculation.8,15−17,22,23

Urea is also a popular building block in the field of new drug discovery due to its stable H-bonding with a variety of target proteins or receptors.24,25 In the past 2 decades, several urea-containing drugs have been approved, for example, sorafenib, regorafenib, ritonavir, and lenvatinib, and more candidates are in clinical or preclinical studies. The solvation of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) could offer benefits on physicochemical properties, so it has gradually become an attractive strategy in drug design and polymorph screening.26,27 So far, several drugs as solvates covering ethanolate, acetone, and DMSO complexes have been approved.28−30 Cumulative research on the complexation of diarylureas with strong acceptors suggest that the solvation of urea-containing drugs is a feasible direction. DMSO is an ideal solvent since it has at least three advantages: (a) high safety, (b) a strong proton acceptor, and (c) excellent solubility beneficial for overcoming the poor solubility for most urea derivatives.31 Jagdev Singh et al. reported getting a sorafenib DMSO solvate in a 1:1 stoichiometry according to powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) in a WO patent.32 Another patent described the connection between regorafenib and DMSO without a complexing ratio.33 Because of the lack of single crystals and more supporting data, the conclusion in both studies is inadequate. Unfortunately, except for these few general polymorph screening studies, research on the cooperation of diarylurea drugs with DMSO and related crystal structure is seldom reported. As the two best-selling drugs for cancer diseases for over 10 years, it is still unclear whether sorafenib and regorafenib could cocrystallize with DMSO. The possible bonding configuration, packing diversities before or after binding, and the influence of variant aromatic substituents on the crystal structure of corresponding DMSO cocrystals remain to be elucidated.

Donafenib (Figure 1) is a new generation of diphenylurea target kinase inhibitor deuterated from sorafenib proved to significantly improve overall survival (OS) with favorable safety and tolerability versus sorafenib.34 We focus on this API together with the deuterated derivative of regorafenib named deuregorafenib. In view of the deuterated effect, four diarylurea molecules including sorafenib, donafenib, regorafenib, and deuregorafenib were included in our study at first. As the steric, substitution, and electronic effects all influence connection,7,35−37 donafenib was disassembled and five related arylurea process impurities (6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) were added to the scope. Then, as a supplement to reach a conclusion, other three commercial arylureas (11, 12 and 13) were also included. A general complexing procedure was developed, and it was applied to the above 12 designed substrates (Figure 1) for binding screening. Following attention focused on the single-crystal preparation for those successfully bonded cases, luckily five cocrystals were obtained from sorafenib, donafenib, deuregorafenib, 6, and 7. Crystal structures were carefully compared with reported parent motifs including sorafenib and regorafenib.38−41 Several other disclosed simpler diarylureas and their DMSO solvates were also compared.42,43 The molecular packing and stability were assessed from substitution effect and steric hindrance together with the relative lattice energy (ΔElatt) calculation to rationalize observed similarities and diversities.

Figure 1.

Diarylurea drugs and derivatives designed in this paper. Compounds 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 are process impurities disassembled from donafenib while 11, 12, and 13 are commercially available.

An element analysis (EA) issue on donafenib had been found by us a couple of years ago: the content of C and N for an earlier batch of donafenib separated from a binary solution of DMSO and water was lower than the theoretical value even after longer dryness. Later, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) investigation found the presence of a little DMSO, and we speculated that the formation of a small part of donafenib solvate may be the root cause. In this paper, a study on the polymorph transformation between these complexes and their parent polymorph was also performed through a water-test which was helpful to explain this EA issue.

Experiment Section

Materials

Methan-d3-amine hydrochloride (CD3NH2·HCl) was supplied by Suzhou Zelgen Biopharmaceuticals Ltd. Co. and it was charged as the deuterium source to give donafenib and deuregorafenib, following a patented procedure44 (Scheme 1). Five process impurities of donafenib (compounds 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) were prepared in Scheme 2. Sorafenib, regorafenib, 11, 12, 13, and other commercial reagents or solvents were purchased and used directly.

Scheme 1. Route to Prepare Donafenib and Deuregorafenib from CD3NH2·HCl.

Scheme 2. Routes to Prepare 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10.

Synthesis of Diarylureas and Corresponding DMSO Complexes

Diarylureas

The synthesis route for donafenib is outlined in Scheme 1: methyl 4-chloropicolinate (1) is converted to 4-chloro-N-(methyl-d3)picolinamide (2) by amination with CD3NH2·HCl, following substitution reaction with 4-aminophenol (2-1) affords 4-(4-aminophenoxy)-N-(methyl-d3)picolinamide (3). Donafenib forms after a final addition reaction with 1-chloro-4-isocyanato-2-(trifluoromethyl)benzene (3-1). Deuregorafenib could be achieved by a similar strategy by charging 4-amino-3-fluorophenol (2-2) instead of 2-1 in the substitution step. The self-condensation of 3 using N,N′-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) gives compound 6, and 4-chloro-3-(trifluoromethyl)aniline (5) reacts with its corresponding isocyanate (3-1) to achieve 7. The hydrolysis of donafenib in strong base provides 8, and the coupling reaction between 3 or 5 with ammonia with the help of CDI affords 9 or 10 (Scheme 2). The detailed synthesis procedure for major diarylureas and intermediates is summarized in the Supporting Information; NMR spectra for three deuterated diarylureas are also included (Figures S1–S6).

Diarylurea DMSO Complexes

Take donafenib as an example; the scheme for preparing the corresponding DMSO complex is shown in Scheme 3. A general procedure was developed as follows: aryl–urea sample dissolves in DMSO with gentle heating; the resulting clear solution was then kept stirring with gradual cooling to room temperature, filtration under nitrogen until little filtrate dropped, and the resulting cake was subsequently dried in high vacuum at 50 °C to give the target complex.

Scheme 3. Conversion between Donafenib and Donafenib·DMSO.

Donafenib·DMSO

Donafenib (5.0 g) was added to DMSO (15 mL), and the mixture was stirred below 60 °C until completely dissolving under nitrogen protection. After cooling and filtration, the resulting cake was dried in vacuum at 50 °C for 48 h to afford the title compound as an off-white solid (4.1 g), yield: 70%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.22 (s, 1H), 9.00 (s, 1H), 8.75 (s, 1H), 8.51 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.68–7.58 (m, 4H), 7.39 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.14 (m, 3H), and 2.55 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 166.43, 164.31, 152.95, 152.92, 150.85, 148.33, 139.79, 137.51, 132.47, 127.19 (q, J = 30.7 Hz), 123.60, 123.29 (q, J = 271.0 Hz), 122.85, 121.92, 121.01, 117.32 (q, J = 5.3 Hz), 114.49, 109.15, and 40.87. LCMS m/z: 468.27 [M–DMSO + H]+ (ES+) C23H19D3ClF3N4O4S (545.98), calcd C 50.60, H 4.61, N 10.26; found, C 50.73, H 4.09, N 10.40.

To get the corresponding single crystals, a milligram scale of donafenib dissolved in DMSO mixed with a little water with gentle heating, filtration, and the sealed clear solution was kept at room temperature for days; colorless massive crystals were crystallized.

Sorafenib·DMSO

Separated as off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.22 (s, 1H), 9.00 (s, 1H), 8.79–8.76 (m, 1H), 8.52 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.69–7.59 (m, 4H), 7.39 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.15 (m, 3H), 2.80 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), and 2.55 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 166.44, 164.26, 152.94, 150.84, 148.33, 139.81, 137.53, 132.47, 127.20 (q, J = 29.3 Hz), 123.60, 123.29 (q, J = 271.0 Hz), 122.82, 121.92, 121.00, 117.29 (q, J = 5.4 Hz), 114.49, 109.15, 40.92, and 26.47. LCMS m/z: 465.20 [M + H]+ (ES+) C23H22ClF3N4O4S (542.96), calcd. C 50.88, H 4.08, N 10.32; found, C 51.05, H 4.12, N 10.46.

In similar crystallization conditions as for donafenib·DMSO, colorless massive crystals were collected.

Deuregorafenib·DMSO

Separated as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.53 (s, 1H), 8.75–8.73 (m, 2H), 8.54 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.66–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.46 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (dd, J = 2.8, 11.6 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (dd, J = 2.4, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (dd, J = 1.2, 8.8 Hz, 1H), and 2.56 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 165.93, 164.22, 153.20 (d, JCF = 243.9 Hz), 153.03, 152.61, 150.91, 148.59 (d, JCF = 10.1 Hz), 139.47, 132.52, 127.30 (q, J = 30.3 Hz), 125.39 (d, JCF = 10.6 Hz), 123.39, 123.25 (q, J = 271.0 Hz), 123.09, 122.96, 117.51, 117.10 (q, J = 5.3 Hz), 114.57, 109.49 (d, JCF = 21.7 Hz), 109.44, 40.91, and 25.63 (weak, CD3). LCMS m/z: 486.25 [M + H]+ (ES+) C23H18D3ClF4N4O4S (563.97), calcd. C 48.98, H 4.29, N 9.93; found, C 48.94, H 3.78, N 10.03.

Under similar crystallization conditions as for donafenib·DMSO, colorless needle-like crystals were obtained.

Regorafenib·DMSO

Separated as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.53 (s, 1H), 8.79–8.73 (m, 2H), 8.54 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.66–7.60 (m, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (dd, J = 2.4, 11.6 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (dd, J = 2.4, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 2.84 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), and 2.58 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 165.92, 164.19, 153.13 (d, JCF = 243.8 Hz), 153.01, 152.58, 150.86, 148.54 (d, JCF = 10.2 Hz), 139.46, 132.47, 127.30 (q, J = 30.3 Hz), 125.41 (d, JCF = 10.6 Hz), 123.32, 123.23 (q, J = 271.3 Hz), 123.09, 122.84, 117.46, 117.07 (q, J = 5.3 Hz), 114.53, 109.45, 109.42 (d, JCF = 21.9 Hz), 40.88, and 26.42. LCMS m/z: 483.22 [M + H]+ (ES+) C23H21ClF4N4O4S (560.95), calcd C 49.25, H 3.77, N 9.99; found, C 49.36, H 3.76, N 10.08.

6·DMSO

Separated as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.92 (s, 2H), 8.78 (s, 2H), 8.55 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H), 7.44 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 2H), 7.23–7.18 (m, 6H), and 2.59 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 166.50, 164.32, 153.09, 152.92, 150.84, 147.98, 137.99, 121.94, 120.55, 114.44, 109.15, 40.89, and 25.58 (weak, CD3). LCMS m/z: 519.39 [M + H]+ (ES+) C29H24D6N6O6S (596.69), calcd C 58.38, H 6.08, N 14.08; found, C 58.43, H 5.11, N 14.12.

Under similar crystallization conditions as for donafenib·DMSO, colorless plate crystals were obtained.

7·DMSO

Separated as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.33 (s, 2H), 8.09 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 7.70–7.67 (m, 2H), 7.64–7.61 (m, 2H), and 2.55 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 152.74, 139.35, 132.36, 127.21 (q, J = 30.4 Hz), 123.22 (q, J = 271.4 Hz), 123.81, 123.28, 117.58 (q, J = 5.4 Hz), and 40.84. LCMS m/z: 417.07 [M + H]+ (ES+) C17H14Cl2F6N2O2S (495.26), calcd C 41.23, H 2.85, N 5.66; found, C 41.37, H 2.87, N 5.87.

Under similar crystallization conditions as for donafenib·DMSO, colorless needle-like crystals were obtained.

8·DMSO

Separated as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 12.89 (s, 1H), 9.28 (s, 1H), 9.06 (s, 1H), 8.58 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.69–7.61 (m, 4H), 7.44 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.19 (m, 3H), and 2.56 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 166.03, 165.37, 152.46, 150.59, 150.44, 147.67, 139.33, 137.19, 131.92, 126.71 (q, J = 30.4 Hz), 123.03, 122.79 (q, J = 271.0 Hz), 122.32, 121.36, 120.49, 116.80 (q, J = 5.7 Hz), 114.60, 111.80, and 40.39. LCMS m/z: 452.18 [M + H]+ (ES+) C22H19ClF3N3O5S (529.92), calcd C 49.86, H 3,61, N 7.93; found, C 49.97, H 3,68, N 8.12.

Solid obtained when 9, 10, 11, or 12 was tried while following the above procedure contained little DMSO as shown in NMR. As for 13, its solubility in DMSO is too high to form any precipitate. MS spectra for the above five cocrystals are reported in the Supporting Information (Figures S21–S25) in positive mode.

NMR Analysis Experiment

Whether a substrate could complex with DMSO or not can be quickly discriminated by NMR. DMSO-d6 is used as a checking NMR solvent with a satisfactory resolution to DMSO. On the other hand, the great dissolving capacity of DMSO-d6 is fit for these ureas. 1H NMR and 13C NMR are recorded on a Bruker AV400 MHz equipment. NMR also plays a crucial role in the polymorph transformation study.

IR Analysis Experiment

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) can also check the conversion between the parent urea and its DMSO complexes. All samples were run on a PerkinElmer spectrum two FT-IR spectrometer in the 400–4000 cm–1 region using a potassium bromide disk.

DSC and TGA Experiments

All differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were collected on a TA Instruments Q2000 DSC equipment at a heating rate of 10 °C/min from 30 to 300 °C. TGA was run on a Q500 TGA at a heating rate of 10 °C/min from 30 to 350 °C.

PXRD Experiment

PXRD was performed at room temperature on a Bruker D2 Phaser X-ray diffractometer. Data were collected and integrated over a 2θ = 3–45° with a step size of 0.02° using Bruker software.

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction Experiment

Single-crystal X-ray structures were collected on either a Bruker D8 Venture or Bruker SMART II CCD diffractometer using Mo Kα or Cu Kα radiation at a set temperature between 150 and 296 K. All nonhydrogen atoms were solved using direct methods and refined by full matrix least-squares refinement on F2 with anisotropic displacement parameters by SHELXL-97 followed by Mercury software for generation of the graphics for structural illustrations. All hydrogen atoms were placed by geometric calculation and difference Fourier map method. The overlap view for different structures was handled by Olex-2 software.

Polymorph Transformation Study by Water-Test

Five volumes of purified water were added to each complex with vigorous stirring at room temperature for hours, filtration, and adequate water-wash. The wet cake was dried in a high vacuum below 60 °C to afford the target solid which would be checked by NMR, infrared (IR), PXRD, or thermal analysis if necessary.

Results and Discussion

NMR

Apparent DMSO methyl group peak occurred from both 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra in cocrystallization test for donafenib, sorafenib, regorafenib, deuregorafenib, 6, 7, and 8. The guest peak takes satisfactory resolution to that of DMSO-d6 (δDMSO vs δDMSO-d6: 2.55 ppm (singlet) versus 2.50 ppm (quintet) for 1H NMR, 40.87 ppm (singlet) versus 39.52 ppm (septet) for 13C NMR).45 Calculated stoichiometric ratio of each host to DMSO is close to 1:1 from 1H NMR. Trace DMSO is observed in the case of 9, 10, 11, and 12. For the polymorph transformation study, 1H NMR of the solid from the water-test experiment shows little DMSO. The absence of DMSO confirms the smooth conversion between free diarylurea and its DMSO complexes. Taking donafenib as an example, Figure 2 presents the NMR comparison for donafenib, donafenib·DMSO, and the water-test sample from the complex. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectrums for all seven DMSO complexes are summarized in the Supporting Information (Figures S7–S20).

Figure 2.

NMR comparison for donafenib and donafenib·DMSO in DMSO-d6. (a) 1H NMR comparison: donafenib from Scheme 1 (up), donafenib·DMSO (middle), and donafenib from donafenib·DMSO by water-test (down), δDMSO = 2.55 ppm. (b) 13C NMR comparison: donafenib (up) and donafenib·DMSO (down), δDMSO = 40.87 ppm.

Infrared Spectroscopy

Each DMSO complex more or less takes partly the difference from its parent phase from the FT-IR spectrum. Figure 3 illustrates the IR contrast images of sorafenib, sorafenib·DMSO, and the corresponding water-test sample; the major difference is around 3505, 3315, 1658, and 1026 cm–1. The overlap view of IR for deuregorafenib and deuregorafenib·DMSO is presented in the Supporting Information (Figure S28).

Figure 3.

FT-IR spectrum comparison for sorafenib (black), sorafenib obtained from water-test (red), and sorafenib·DMSO (blue).

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction

The cocrystallization possibility of designed arylureas with DMSO could be checked by NMR or IR preliminary, while the packing motif of the resulting cocrystals is clarified by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD). Crystallographic data for donafenib·DMSO, sorafenib·DMSO, deuregorafenib·DMSO, 6·DMSO, and 7·DMSO is illustrated in Table 1. H-bonding parameters for five cocrystals are outlined in Table 2. Selected bond lengths, bond angles, and torsion angles [for C(O)–N–C–Cmeta] are summarized in the Supporting Information (Tables S1–S3).

Table 1. Crystallographic Data for Five DMSO Cocrystals.

| items | sorafenib·DMSO | donafenib·DMSO | deuregorafenib·DMSO | 6·DMSO | 7·DMSO |

| emp formula | C21H16F3ClN4O3·C2H6OSa | C21H16F3ClN4O3·C2H6OSa | C21H16F4ClN4O3·C2H6OSa | C27H24N6O5·C2H6OS | C15H8Cl2F6N2O·C2H6OS |

| formula weight | 542.96 | 542.96 | 560.95 | 590.65 | 495.26 |

| morph | colorless prism | colorless prism | colorless column | colorless plate | colorless prism |

| crystal system | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic | orthorhombic |

| radiation type | Cu Kα | Cu Kα | Cu Kα | Cu Kα | Mo Kα |

| space group | C2/c | C2/c | P21/n | P21/n | Pbcn |

| T (K) | 293(2) | 296(2) | 296(2) | 296(2) | 153(2) |

| a (Å) | 26.892(5) | 26.8958(4) | 4.7798(10) | 8.4185(2) | 24.667(5) |

| b (Å) | 9.1505(18) | 9.14870(10) | 25.2776(4) | 27.7289(7) | 13.077(3) |

| c (Å) | 21.600(4) | 21.6102(3) | 20.8555(3) | 12.6639(4) | 25.283(5) |

| α (deg) | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β (deg) | 105.64(3) | 105.6180(10) | 90.610(10) | 94.0510(10) | 90.00 |

| γ (deg) | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| vol (Å3) | 5118.5(18) | 5121.11(12) | 2519.66(8) | 2948.82(14) | 8156(3) |

| Z | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| calculated density | 1.409 mg/m3 | 1.408 mg/m3 | 1.479 mg/m3 | 1.330 mg/m3 | 1.613 mg/m3 |

| crystal size | 0.13 × 0.11 × 0.08 mm | 0.24 × 0.12 × 0.11 mm | 0.32 × 0.12 × 0.04 mm | 0.40 × 0.12 × 0.06 mm | 0.18 × 0.14 × 0.12 mm |

| R(int) | 0.0983 | 0.0347 | 0.0334 | 0.0245 | 0.0929 |

| Rw | 0.3079 | 0.1444 | 0.1494 | 0.1052 | 0.1503 |

| absorption coefficient | 2.609 mm–1 | 2.608 mm–1 | 2.729 mm–1 | 1.419 mm–1 | 0.492 mm–1 |

| independent reflections | 4602 | 4571 | 4324 | 5205 | 8341 |

| measured reflections | 24037 | 14855 | 12442 | 19872 | 55874 |

| CCDC deposition no. | 2041748 | 2041747 | 2041750 | 2041749 | 2041751 |

SC-XRD could not discriminate D and H, the “emp formula” and “formula weight” for the listed three deuterated cocrystals (donafenib·DMSO, deuregorafenib·DMSO, and 6·DMSO) are recorded as nondeuterated styles. The corresponding presence of a deuterium atom is confirmed by NMR.

Table 2. H-Bonds Information for Five Cocrystals.

| cocrystals | D–H···A | d (D–H)/Å | d (H···A)/Å | d (D···A)/Å | angel (D–H···A)/° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| donafenib·DMSO | N1–H1A···O4 | 0.86 | 2.18 | 2.918(3) | 143.3 |

| N2–H2A···O4 | 0.86 | 2.09 | 2.842(3) | 145.8 | |

| N4–H4A···O3 | 0.91 | 2.14 | 2.949(2) | 147.4 | |

| C3–H3B···O1 (urea) | 0.93 | 2.32 | 2.843(3) | 114.8 | |

| C9–H9A···O1 (urea) | 0.93 | 2.34 | 2.880(3) | 116.7 | |

| N4–H4A···N3 (pyridine) | 0.91 | 2.32 | 2.694(3) | 103.9 | |

| sorafenib·DMSO | N1–H1A···O4 | 0.86 | 2.16 | 2.897(6) | 143.6 |

| N2–H2A···O4 | 0.86 | 2.08 | 2.832(6) | 146.3 | |

| N4–H4A···O3 | 0.86 | 2.21 | 2.951(6) | 144.8 | |

| C3–H3B···O1 (urea) | 0.93 | 2.32 | 2.833(7) | 114.4 | |

| C13–H13A···O1 (urea) | 0.93 | 2.36 | 2.896(7) | 116.1 | |

| N4–H4A···N3 (pyridine) | 0.86 | 2.31 | 2.695(7) | 107.2 | |

| deuregorafenib·DMSO | N1–H1A···O4 | 0.86 | 2.07 | 2.883(3) | 156.1 |

| N2–H2A···O4 | 0.86 | 2.07 | 2.874(3) | 156.1 | |

| N4–H4A···O1 | 0.86 | 2.36 | 3.025(3) | 135.0 | |

| C5–H5A···O1 (urea) | 0.93 | 2.30 | 2.855(3) | 118.1 | |

| C13–H13A···O1 (urea) | 0.93 | 2.26 | 2.847(3) | 120.8 | |

| 6·DMSO | N3–H3···O1′ | 0.86 | 2.09 | 2.904(18) | 157.1 |

| N4–H4···O1′ | 0.86 | 2.14 | 2.953(2) | 156.6 | |

| N1–H1···O5 | 0.86 | 2.42 | 3.058(18) | 131.8 | |

| C2′–H2′A···O3 | 0.96 | 2.50 | 3.400(3) | 155.6 | |

| C7–H7···O4 | 0.93 | 2.61 | 3.184(2) | 120.6 | |

| C10–H10···O3 | 0.93 | 2.23 | 2.832(19) | 121.9 | |

| C16–H16···O3 | 0.93 | 2.23 | 2.830(2) | 121.9 | |

| C17–H17···O3 | 0.93 | 2.61 | 3.532(2) | 170.0 | |

| C22–H22···N2 | 0.93 | 2.63 | 3.501(19) | 156.3 | |

| 7·DMSO | N1–H1A···O2 | 0.88 | 2.00 | 2.839(4) | 160.0 |

| N2–H2A···O2 | 0.88 | 2.10 | 2.920(4) | 155.3 | |

| N3–H3A···O4 | 0.88 | 2.01 | 2.848(4) | 158.1 | |

| N4–H4A···O4 | 0.88 | 2.02 | 2.856(4) | 157.3 | |

| C10–H10A···O1 | 0.95 | 2.21 | 2.837(4) | 122.5 | |

| C3–H3B···O1 | 0.95 | 2.23 | 2.855(4) | 122.7 | |

| C20–H20A···O3 | 0.95 | 2.26 | 2.875(4) | 121.9 | |

| C27–H27A···O3 | 0.95 | 2.23 | 2.853(4) | 122.4 |

Sorafenib·DMSO

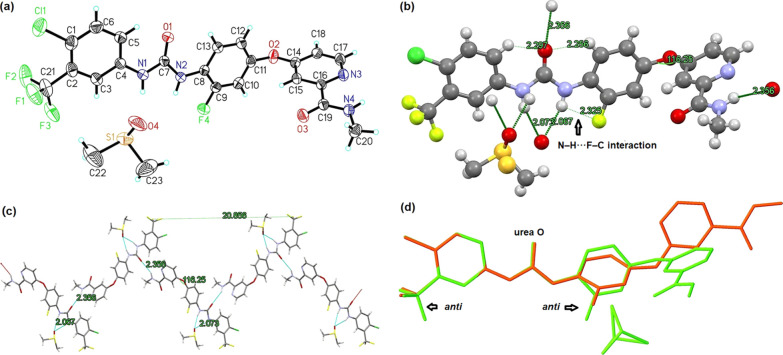

The ORTEP, ball-and-stick, and capped sticks views for sorafenib·DMSO are shown in Figure 4a–c. This colorless massive complex crystallizes in monoclinic space group C2/c with eight molecules in the unit cell. The crystal structure shows that one sorafenib molecule combines with one DMSO (partly in disorder) in bifurcated intermolecular H-bonding interaction, while the oxygen atom (O4) of DMSO accepts two urea NH (N1–H1A, N2–H2A) directly (2.16, 2.08 Å; 143.6, 146.3°) as a six-membered cyclic pattern. At the same time, another strong intermolecular H-bond forms between the host molecules, while Oamide (O3) directs to the NHamide (N4–H4A) (2.21 Å, 144.8°) of a neighboring sorafenib molecule. In addition, intramolecular interactions including N–H···Npyridine (2.31 Å, 107.2°) and Ourea···H–C (o-phenyl) (2.32, 2.36 Å; 114.3, 116.3°) together with short contact between Ourea with adjacent C–HDMSO (2.27 Å, 161.2°) both contribute to the stability of this cocrystal. The integrated interactions lead to a zigzag (9.15 Å) packing pattern for sorafenib·DMSO (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

(a) ORTEP view for the asymmetric unit of sorafenib·DMSO. (b) Ball-and-stick view for sorafenib·DMSO: DMSO is in disorder and CF3 is orientated syn to Ourea, H-bonds are shown as dashed lines. (c) Capped sticks view for sorafenib·DMSO as a zigzag pattern. (d) Overlap view for sorafenib·DMSO (red) and sorafenib (green, CCDC no.: 813502): CF3 is orientated anti to Ourea in sorafenib.

Interestingly, when compared to the well-documented crystalline structure of sorafenib,38 the CF3 group in sorafenib·DMSO twists to a syn-conformation to urea C=O from anti (Figure 4d). This change can be attributed to the fact that this strong electron-withdrawing group can increase the acidity of the donor ortho C–H, strengthening the intramolecular C–H···Ourea interaction.6,16,46 On the other hand, the syn-orientated CF3 surrounds less steric hindrance which is beneficial for the inclusion of DMSO. Relative lattice energy (ΔElatt) at zero Kelvin calculation is carried out by VASP software to assess the stability and rationality of possible computational simulated structures for sorafenib and related DMSO solvate (Table 3).47 The ΔElatt of sorafenib while CF3 is in syn-conformation is 18.56 kJ/mol versus the anti-conformation case revealing that CF3 in anti-conformation is more thermodynamically stable at 0 Kelvin which is just the reported crystalline structure. As for sorafenib·DMSO, the disordered DMSO (0.474:0.526) leads to two disordered types (type A and B, Figure 5a) resulting in four possible motifs, both cases while CF3 is orientated to syn-position giving lower ΔElatt (syn vs anti, type A: 0 vs 80.24 kJ/mol; type B: 8.30 vs 23.26 kJ/mol). In the anti-conformation case, the proximity of CF3 groups in adjacent host molecules leads to obvious steric hindrance (Figure 5b). Hence, the packing motif in disordered type A with CF3 locating in syn orientation is the most thermodynamically stable arrangement for sorafenib·DMSO.

Table 3. Relative Lattice Energy (ΔElatt) for Simulated Structures of Sorafenib and Sorafenib·DMSO.

Compared to sorafenib-1.

Compared to sorafenib·DMSO-A1.

Figure 5.

(a) Two disordered types in the crystalline motif of sorafenib·DMSO: type A and B (0.474:0.526). (b) Simulated structures for sorafenib·DMSO-A1 and sorafenib·DMSO-B1: (up) little steric hindrance; for sorafenib·DMSO-A2 and (down) sorafenib·DMSO-B2, obvious steric effects observed from neighboring CF3.

Donafenib·DMSO

The ball-and-stick view for donafenib·DMSO is shown in Figure 6a. Few assembling diversities were observed in contrast to sorafenib·DMSO from the overlap view by Olex 2 software (Figure 6b). In detail, one donafenib molecule recognizes one DMSO (also in disorder) in bifurcated strong intermolecular interaction (2.09, 2.18 Å; 145.8, 143.3°) providing a similar six-membered ring. The Oamide accepts the NHamide of an adjacent host (2.14 Å, 131.7°) leading to a similar zigzag pattern with CF3 in syn-conformation to Ourea. The above two major intermolecular interactions direct the stability of this deuterated complex which is further strengthened by weaker intramolecular N–H···Npyridine (2.32 Å, 103.8°). Weak H-bonds between Ourea and CH (o-aryl), NHamide and pyridine also exist. The great assembling consistent between donafenib·DMSO and sorafenib·DMSO suggests that D–H exchange would hardly disrupt the bonding interaction or packing motif for related DMSO complexes.

Figure 6.

(a) Ball-and-stick view for donafenib·DMSO: DMSO is in disorder, H-bonds are shown as dashed lines. (b) Perfect overlap between Sonafenib·DMSO (green) and donafenib·DMSO (red) by Olex 2 software, both CF3 are orientated syn to Ourea.

6·DMSO

The ORTEP, ball-and-stick, and capped sticks views for 6·DMSO are presented in Figure 7a–c. As a deuterated symmetric donafenib process impurity, 6 cocrystallizes with DMSO as a colorless plate in a monoclinic crystal system with four molecules in the unit cell, and the space group is P21/n. To our astonishment, the ODMSO (O1′) still receives the two urea NH (N4–H4, N3–H3) in a similar 6-membered cyclic intermolecular H-bonding interaction (2.09, 2.14 Å; 157.1, 156.6°), although no electron-withdrawing group substituted as donafenib or sorafenib, and the stoichiometry is maintained at 1:1 without any disorder. 6·DMSO offers a counter-example to the cocrystallization rule of Etter.6 This maybe associate with the two coplanar symmetrical aryl planes which could reduce the steric hindrance for the inclusion of DMSO. On the other hand, the symmetrical amides act as new H-bond donors (N1–H1) and acceptors (O5) to adjacent substrates (2.42 Å, 131.8°). Intermolecular interactions lead to a helical pattern (pitch: 27.7 Å) with anchored DMSO (Figure 7d). Owing to steric effects, C=O and N–H in the same amide unit cannot participate in H-bonding at the same time as donafenib. Moreover, the perfect coplanar [torsion angle (C(O)–N–C–Cortho): −9.3(2)°, 171.30(15)°, 171.30(15)° and −7.2(3)°, see Table S3] promotes the weak intramolecular Ourea···H–C (o-aryl) in nearly the same length (2.23 Å). Integrating more diverse intermolecular and intramolecular H-bonding interactions contribute to the stability of this novel helical packing motif.

Figure 7.

Diverse views for the asymmetric unit of 6·DMSO. (a) ORTEP view, (b) ball-and-stick view with intermolecular (N–Hurea···ODMSO, N–Hamide···Oamide) and intramolecular H–bonds (Ourea···H–Co-aryl, N–Hamide···Npyridine), (c) capped sticks view, and (d) spacefill view as a helix pattern: helical pitch = 27.7 Å. H-bonds are shown as dashed lines.

7·DMSO

7 is another symmetric diarylurea process impurity of donafenib with two meta-substituted CF3 groups. The ball-and-stick (Figure 8a) and capped sticks (Figure 8b) views for 7·DMSO are illustrated. Greatly diverse from the other four complexes or reported solvates, 7·DMSO crystallizes as a bis-molecular motif in orthorhombic space group Pbcn with 16 molecules in the unit cell. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first diarylurea DMSO complex with Z = 16. Owing to the strong electron-withdrawing effect of CF3, 7 smoothly accepts DMSO in similar six-membered H-bonding interaction (2.00, 2.10 Å/2.01, 2.02 Å; 160.0, 155.3°/158.1, 157.3°). Without pyridine or amide unit, the bonding interaction in 7·DMSO is much simpler, and host molecules are bridged predominantly by van der Waals force. However, a significant off-set face-to-face π–π stacking interaction between adjacent phenyl rings (3.674 and 3.698 Å, Figure 8b) forms. Aryl rings are cross-arranged, which is beneficial for the packing stability from steric hindrance. In addition, weak intramolecular C–H···Ourea (C10–H10···O1, C3–H3···O1/C20–20···O3, C27–H27···O3; 2.21, 2.23 Å/2.26, 2.23 Å; 122.5, 122.7°/121.9, 122.4°) generates due to the electron-withdrawing effect from CF3. Swift has noted that the relative stable orientation of meta-substituents for both mono- and bis meta-substitution is on the opposite side of Ourea.7,8,23,37 However, both CF3 in this case are orientated to the syn-conformation. This change could be rationalized by less steric and electronic effects superiority to strengthen the intramolecular C–H···Ourea by reducing the acidity of ortho-aryl C–H.

Figure 8.

(a) Ball-and-stick view for 7·DMSO as a bismolecule with two disordered DMSO, the orientation of both m-CF3 is syn to Ourea; intermolecular (N–Hurea···ODMSO) and intramolecular H-bonds (Ourea···H–Co-phenyl) are shown as dashed lines. (b) Capped sticks view for 7·DMSO as a paralleled pattern with obvious π–π stacking interaction (3.674 and 3.698 Å).

Deuregorafenib·DMSO

An ortho F atom added to donafenib on the middle phenyl unit gives deuregorafenib. The ORTEP, ball-and-stick, and capped sticks views for deuregorafenib·DMSO are shown in Figure 9a–c. The crystal structure shows that F–H exchange will not disturb the arrangement of the above six-membered H-bonding pattern (2.07, 2.07 Å; 156.1, 156.1°) between deuregorafenib and DMSO (partly in disorder) in a stoichiometry of 1:1. By contrast, previous intermolecular N–Hamide···Ourea within adjacent host molecules in sorafenib·DMSO, donafenib·DMSO, and 6·DMSO are absent. Instead, Ourea (O1) of one deuregorafenib accepts the NHamide (N4–H4) of a neighboring host generating a new kind of H-bond (2.36 Å, 135.0°). This dramatic change is possible because of the bond angle of the aromatic ether structure (Figure 9b and Table S2) in deuregorafenib·DMSO [C14–O2–C11, 116.25 (18)°], smaller than that of sorafenib·DMSO [119.4 (5)°], donafenib·DMSO [120.16 (18)°], and 6·DMSO [119.46 (12), 119.75 (12)°]. The decreased angle increases the steric hindrance for the previous direct amide H-bonding between host molecules. However, this change promotes the new formed H-bond. Directed by the two crucial intermolecular interactions, deuregorafenib·DMSO crystallizes as colorless needles in a monoclinic crystal system with four molecules in the unit cell, and the space group is P21/n.

Figure 9.

(a) ORTEP view for deuregorafenib·DMSO. Both orientations of m-CF3 and o-F are anti to Ourea. (b) Ball-and-stick view for deuregorafenib·DMSO, DMSO partly in disorder. Intermolecular (N–Hurea···ODMSO, N–Hamide···Ourea) and intramolecular H-bonds (Ourea···H–Co-aryl, N–Hamide···Npyridine) presented as dashed blue lines. (c) Capped sticks view, crystallized as a zigzag pattern. (d) Overlap view between doregorafenib·DMSO (green) and regorafenib (red) by Olex 2, F and CF3 in both crystals in anti-orientation to Ourea, obvious twist for the pyridine unit.

The orientation study exhibits that CF3 in this complex is in anti to Ourea. Moreover, the added F atom is also orientated to an anti-position. As we know, CF3 in sorafenib, regorafenib, or regorafenib monohydrate all present syn-conformation.38−41 To clarify, the relative lattice energy calculation simulated for regorafenib and deuregorafenib·DMSO was also performed, and corresponding contrasting data was outlined (Figure 10a,b and Table 4): both CF3 and F in anti-conformation leads to the lowest ΔElatt for four possible regorafenib motifs (0.00, 7.14, 28.89, and 42.59 kJ/mol). As for deuregorafenib·DMSO, although DMSO is partly in disorder (type A:type B = 0.787:0.213, Figure 10a), either case of CF3 and F being in anti-conformation gives the lowest ΔElatt (type A: 0.00 (deuregorafeniB·DMSO-A1 as standard, anti/anti), 34.16 (anti/syn), 43.89 (syn/anti), and 72.85 kJ/mol (syn/syn); type B: 11.1 (anti/anti), 4.83 (anti/syn), 48.87 (syn/anti) and 79.08 kJ/mol (syn/syn). Once CF3 locates in syn position, repulsive interaction occurs between CF3 and pyridine unit, and similar repulsion between F and Ourea generates if F is in syn-conformation. Repulsion interaction would decrease the packing stability. Another possible explanation for the orientation of F atom is associated with the reported weak N–H···F–C interaction (2.33 Å, Figure 9b) between neighboring NHurea and the ortho-F.28 Hence, although F–H exchange hardly affects the H-bonding pattern between the host and DMSO, it strongly influences the role of other donors or acceptors, giving a significant diverse structure to that of sorafenib or donafenib. A slight change in aromatic substituents indeed provides dramatic packing diversity for the cocrystals.41

Figure 10.

(a) Two disordered types in the crystalline motif of deuregorafenib·DMSO: type A and type B (0.787:0.213). (b) four selected simulated structures for deuregorafenib·DMSO, deuregorafenib·DMSO-A2 with obvious polarity repulsion between F atom and Ourea, and deuregorafenib·DMSO-B4 with both polarity repulsion between F and Ourea, CF3 and Npyridine.

Table 4. Relative Lattice Energy for Simulated Structures of Regorafenib and Deuregorafenib·DMSO.

Compared to regorafenib-1.

Compared to deuregorafenib·DMSO-A1.

Dihedral Angle of Two Aryl Planes

The great consistency of the crystal structure for sorafenib·DMSO and donafenib·DMSO suggests that D–H exchange could not influence the final arrangement. Based on this hypothesis, regorafenib·DMSO would present nearly the same assembling as deuregorafenib·DMSO. Packing comparison for more diarylureas and relevant DMSO complexes involving sorafenib with sorafenib·DMSO or donafenib·DMSO, regorafenib with deuregorafenib·DMSO, and other three combinations disclosed in the Cambridge Structural Database are summarized (Table 5).7,26,38,40,46 Data cumulates that the dihedral angle of two aryl planes in most cases significantly decreases after the inclusion of DMSO (Figures S29–S30). Especially, the complex of regorafenib (61.52–4.20°, Figure 11a) or 1-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)urea (88.57–9.18, 9.77°) twists to roughly coplanar from the vertical state.26,40,46 This coplanar results in more flexible self-assembly for host strengthening the intramolecular O···H–C (o-aryl). On the other hand, as a stronger H-bond acceptor with relative smaller volume, DMSO faces little steric effects to accept NHurea as an adequate cavity is exposed with the help of planarization. Looking back on the counter-example of 6·DMSO, the corresponding dihedral angle is 7.97° (Figure 11b) and the coplanar motif is fit for the inclusion of DMSO, although no electron-withdrawing groups are included.

Table 5. Comparison of the Dihedral Angle of Two Aryl Planes in Diarylureas and Corresponding DMSO Complexes.

| entry | samples | dihedral angle | CCDC no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | sorafenib38 | 39.06° | 813502 |

| 2 | sorafenib·DMSO | 28.05° | 2041749 |

| 3 | donafenib·DMSO | 28.06° | 2041747 |

| 4 | regorafenib40 | 61.52° | 1045583 |

| 5 | deuregorafenib·DMSO | 4.20° | 2041750 |

| 6 | 1,3-bis(3-cyanophenyl)urea (β conformation)7 | 52.30° | 1060065 |

| 7 | 1,3-bis(3-cyanophenyl)urea DMSO solvate7 | 22.08° | 1060063 |

| 8 | 1-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)urea26 | 88.57° | 231524 |

| 9 | 1-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)urea DMSO solvate46 | 9.18, 9.77° | 676842 |

| 10 | N-(4-methylphenyl)-4′-(4-nitrophenyl)urea46 | 86.79° | 676850 |

| 11 | N-(4-methylphenyl)-4′-(4-nitrophenyl)urea DMSO solvate46 | 18.97, 20.00° | 676844 |

Figure 11.

Dihedral angle of two aryl planes calculated by Mercury software. (a) regorafenib (61.52°), deuregorafenib·DMSO (4.20°), and regorafenib·H2O (2.78°). (b) 6·DMSO (7.97°).

Several other disclosed complexes bonded with water, TPPO, or THF also present a similar decrease in dihedral angles (Table 6, and Figure S31).6,16,23,42,43 As a result, we believe that the planarization of two aryl planes in diarylureas plays a crucial role in the final cocrystallization.

Table 6. Comparison of the Dihedral Angles of Two Aryl Planes in Diarylureas and Related Diverse Cocrystals.

| entry | samples | dihedral angle | CCDC no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | regorafenib | 61.52° | 1045583 |

| 2 | regorafenib·H2O40 | 2.78° | 1045581 |

| 3 | 1,3-bis(3-pyridyl)urea16 | 12.27° | 270965 |

| 4 | 1,3-bis(3-pyridyl)urea dihydrate16 | 1.94° | 270961 |

| 5 | 1,3-bis(m-nitrophenyl)urea42 | 87.79° | 1259385 |

| 6 | 1,3-bis(m-nitrophenyl)urea monohydrate43 | 38.49° | 291328 |

| 7 | 1,3-bis(m-nitrophenyl)urea tetrahydrofuran solvate6 | 5.48° | 1168178 |

| 8 | N,N′-bis[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]urea23 | 87.77° | 1554299 |

| 9 | N,N′-bis[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]urea oxo(triphenyl)-phosphane23 | 31.01° | 1554307 |

PXRD, DSC, and TGA Experiments

Compared to the parent polymorph, the solid form of DMSO complexes take obvious different PXRD patterns which offer extra supporting data for the screened solvates (Figure 12c,d). PXRD obtained from SC-XRD simulation shows consistency with that of the scale-up sample following Scheme 3 in donafenib, and deuregorafenib indicates that the polymorph purity of solids from our general procedure is robust (Figures 12a,b and S27). Solids obtained from the water-test in the polymorph transformation study for the four drug complexes were also checked with PXRD, and each sample is consistent with the related free substrate (Figures 13a,b and S26). This result discloses the smooth desolvation from cocrystals with the help of water. Also, the compared PXRD pattern shows that the D-H exchange has little effect on the crystalline phase. The DSC endothermic peak for donafenib·DMSO is at 122.52 °C (Figure 14a) which is much lower than that of donafenib (210.39 °C, Figure 14c), and related weight loss from TGA (13.78%, calculated from 30 to 150 °C) is fit for the speculated 1:1 composition (Figure 14b, theory loss: 14.33%), while little weight loss happens in donafenib (Figure 14d).

Figure 12.

PXRD comparison between scale-up sample and simulated pattern from the crystal structure for donafenib·DMSO and donafenib. (a) Scale-up experimental pattern for donafenib·DMSO, (b) simulated pattern for donafenib·DMSO, (c) scale-up experimental pattern for donafenib, and (d) simulated pattern for sorafenib (CCDC no: 813502).

Figure 13.

Overlay of PXRD spectra for cocrystallization and polymorph transformation studies. (a) Sorafenib·DMSO (red), sorafenib (blue), donafenib·DMSO (green), and sorafenib from the complex by water-test (black); donafenib·DMSO has a greatly similar PXRD pattern as that of sorafenib·DMSO. (b) Deuregorafenib (black), deuregorafenib·DMSO (red), regorafenib·DMSO, and deuregorafenib (green, from water-test).

Figure 14.

DSC and TGA spectra for donafenib·DMSO and donafenib. (a) DSC of donafenib·DMSO, endothermic peak: 122.52 °C. (b) TGA of donafenib·DMSO, weight loss: 13.78% (calculated from 30 to 150 °C). (c) DSC of donafenib, endothermic peak: 210.39 °C. (d) TGA of donafenib, weight loss: 0.1252% (calculated from 30 to 150 °C).

Polymorph Transformation Study by Water-Test

Each solid from the water-test study by charging corresponding DMSO complex in water with stirring was checked by 1H NMR (Figure 2). Consistently, the methyl peak of DMSO peak disappeared for all samples. Thesolid collected after water-test in the case of donafenib·DMSO was also analyzed with PXRD, proving the regeneration of its parent polymorph and that similar conversion happened to sorafenib·DMSO and deuregorafenib·DMSO. It revealed that the six-membered H-bonding interaction was disrupted quickly in water, and the released DMSO was washed over during workup. The smooth transformation between free diarylureas and their DMSO solvates offers a reasonable explanation for our EA issue, and it also confirms the case that few studies on anion recognition discovered cocrystallization between ureas and DMSO as a large amount of water was charged.20,48−50

Structure Scope for Forming DMSO Solvates to Diarylurea Drug Substances

The cocrystallization rule for this kind of 1:1 complexation has been summarized by Etter.6 Several arylurea drug derivatives or analogues (8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13) were also tried to clarify the structure scope of diarylurea drug substances. However, except for the complete diphenyl–urea sample 8, free urea such as 9, 10, 11, and nonsubstituted 12 failed to recognize DMSO, and 13 dissolves too smoothly in DMSO to give any precipitate. This result indicated that free urea may form unknown stronger H-bonds in the presence of an NH2 unit. Thus, it seems that urea drugs with complete diarylurea unit are more likely to cocrystallize with DMSO.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the cocrystallization of some typical diarylurea drugs or their derivatives with the strong H-bond acceptor DMSO has been examined and analyzed. A scalable procedure for corresponding complexing with DMSO was developed with robust polymorph control. Five new obtained diffraction-quality cocrystals involving three deuterated samples present the 1:1 intermolecular six-membered cyclic H-bonding pattern between these drug-related molecules and DMSO consistently. Deuterium substitution hardly disrupts the complexing motif from sorafenib·DMSO and donafenib·DMSO, while F–H exchange leads to obvious assembling diversities in the case of deuregorafenib·DMSO. The complexing scope study showed that APIs without a complete diarylurea unit are difficult to cocrystallize. Although steric, substitution, and electronic effects indeed influence the orientation of meta- or ortho-substituents, cumulated decreased dihedral angle data of two aryl planes either from our cocrystals or previous structures together with the counter-example of 6·DMSO suggest that the planarization of two diarylurea planes may direct the inclusion of DMSO. Consistent desolvation of obtained complexes in water-test bridges the polymorph transformation between free diarylurea drugs and their DMSO complexes.

The findings on the cocrystallizing study of typical diarylurea drugs or derivatives with DMSO is helpful for new drug development and polymorph screening for urea-containing candidates,51 and we will focus on and share possible pharmaceutical benefits such as the dissolution after complexing in the future.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by Suzhou Zelgen Biopharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. We thank Jiajun Huang and Zhuocen Yang (Shenzhen Jingtai Technology Co., Ltd.) for their help in the relative lattice energy calculation and Yanqing Gong (Shanghai Institute of Pharmaceutical Industry) for her assistance with data collection and refinement.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c05908.

Preparation of major diarylureas and intermediates; spectroscopic characterization (1H NMR, 13C NMR, MS, IR, and PXRD) for complexes; and selected bond lengths, bond angles, torsion angles, and dihedral angles of two aryl planes (PDF)

Accession Codes

CCDC 2041747–2041751 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper.

Author Contributions

∥ C.L. and J.Z. are contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Fan E.; Van Arman S. A.; Kincaid S.; Hamilton A. D. Molecular recognition: hydrogen-bonding receptors that function in highly competitive solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 369–370. 10.1021/ja00054a066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez D. E.; Fabbrizzi L.; Licchelli M.; Monzani E. Urea vs. thiourea in anion recognition. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 1495–1500. 10.1039/b500123d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custelcean R. Crystal engineering with urea and thiourea hydrogen-bonding groups. Chem. Commun. 2008, 295–307. 10.1039/b708921j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilday L. C.; Robinson S. W.; Barendt T. A.; Langton M. J.; Mullaney B. R.; Beer P. D. Halogen bonding in supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7118–7195. 10.1021/cr500674c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter M. C.; Panunto T. W. 1,3-Bis(m-nitrophenyl)urea: an exceptionally good complexing agent for proton acceptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 5896–5897. 10.1021/ja00225a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Etter M. C.; Urbanczyk-Lipkowska Z.; Zia-Ebrahimi M.; Panunto T. W. Hydrogen bond-directed cocrystallization and molecular recognition properties of diarylureas. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 8415–8426. 10.1021/ja00179a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capacci-Daniel C. A.; Mohammadi C.; Urbelis J. H.; Heyrana K.; Khatri N. M.; Solomos M. A.; Swift J. A. Structural diversity in 1,3-bis(m-cyanophenyl)urea. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 2373–2379. 10.1021/acs.cgd.5b00168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomos M. A.; Mohammadi C.; Urbelis J. H.; Koch E. S.; Osborne R.; Usala C. C.; Swift J. A. Predicting Cocrystallization Based on Heterodimer Energies: The Case of N,N′-Diphenylureas and Triphenylphosphine Oxide. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 5068–5074. 10.1021/acs.cgd.5b01039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Kawasaki K.; Kularatne S.; Li Y. H.; Noll B. C.; Scheidt W. R.; Burns D. H. Synthesis of Urea Picket Porphyrins and Their Use in the Elucidation of the Role Buried Solvent Plays in the Selectivity and Stoichiometry of Anion Binding Receptors. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 9081–9087. 10.1021/jo701443c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dial B. E.; Rasberry R. D.; Bullock B. N.; Smith M. D.; Pellechia P. J.; Profeta S. Jr.; Shimizu K. D. Guest-accelerated molecular rotor. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 244–247. 10.1021/ol102659n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen D. M.; Hawes C. S.; Gunnlaugsson T. Solution-state anion recognition, and structural studies, of a series of electron-rich meta-phenylene bis(phenylurea) receptors and their self-assembled structures. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 10398–10408. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b01481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer L.; Engle K. M.; Pidgeon G. W.; Sparkes H. A.; Thompson A. L.; Brown J. M.; Gouverneur V. Hydrogen-bonded homoleptic fluoride-diarylurea complexes: structure, reactivity, and coordinating power. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13314–13325. 10.1021/jacs.6b07501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custelcean R.; Moyer B. A.; Bryantsev V. S.; Hay B. P. Anion Coordination in Metal–Organic Frameworks Functionalized with Urea Hydrogen-Bonding Groups. Cryst. Growth Des. 2006, 6, 555–563. 10.1021/cg0505057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C.; Zuo W.; Zhang D.; Yang X.-J.; Wu B. Anion recognition by oligo-(thio)urea-based receptors. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 9614–9627. 10.1039/c6cc03761e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki R.; Iida M.; Ito A.; Fukuda K.; Tanatani A.; Kagechika H.; Masu H.; Okamoto I. Crystal Engineering of N,N′-Diphenylurea Compounds Featuring Phenyl-Perfluorophenyl Interaction. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 5858–5866. 10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy L. S.; Basavoju S.; Vangala V. R.; Nangia A. Hydrogen Bonding in Crystal Structures ofN,N’-Bis(3-pyridyl)urea. Why Is the N–H···O Tape Synthon Absent in Diaryl Ureas with Electron-Withdrawing Groups?. Cryst. Growth Des. 2006, 6, 161–173. 10.1021/cg0580152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Todd A. M.; Anderson K. M.; Byrne P.; Goeta A. E.; Steed J. W. Helical or Polar Guest-DependentZ’ = 1.5 orZ’ = 2 Forms of a Sterically Hindered Bis(urea) Clathrate. Cryst. Growth Des. 2006, 6, 1750–1752. 10.1021/cg060318o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George S.; Nangia A.; Lam C.-K.; Mak T. C. W.; Nicoud J.-F. Crystal engineering of urea α-network via I···O2N synthon and design of SHG active crystal N-4-iodophenyl-N′-4′-nitrophenylurea. Chem. Commun. 2004, 52, 1202–1203. 10.1039/b402050b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad A.; Agulló C.; Cuñat A. C.; Vilanova C.; Ramírez de Arellano M. C. X-ray Structure of FluorinatedN-(2-Chloropyridin-4-yl)-N’-phenylureas. Role of F Substitution in the Crystal Packing. Cryst. Growth Des. 2006, 6, 46–57. 10.1021/cg049581k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarai A.; Baruah J. B. Conformation and visual distinction between urea and thiourea derivatives by an acetate ion and a hexafluorosilicate cocrystal of the urea derivative in the detection of water in dimethylsulfoxide. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 6991–7001. 10.1021/acsomega.7b01217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak B.; Halder S.; Das G. Terminal substituent induced differential anion coordination and self-assembly: case study of flexible linear bis-urea receptors. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 2298–2307. 10.1021/acs.cgd.8b01934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza A. J. C.; Day G. M.; Motherwell W. D. S.; Jones W. Prediction and observation of isostructurality induced by solvent incorporation in multicomponent crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 14466–14467. 10.1021/ja065845a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomos M. A.; Watts T. A.; Swift J. A. Predicting cocrystallization based on heterodimer energies: part II. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 5073–5079. 10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sikka P.; Sahu J. K.; Mishra A. K.; Hashim S. R. Role of aryl urea containing compounds in medicinal chemistry. Med. Chem. 2015, 5, 479–483. 10.4172/2161-0444.1000305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Brindisi M. Urea derivatives in modern drug discovery and medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 2751–2788. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salorinne K.; Lahtinen T.; Marjomäki V.; Häkkinen H. Polymorphic and solvate structures of ethyl ester and carboxylic acid derivatives of WIN 61893 analogue and their stability in solution. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 9001–9009. 10.1039/c4ce01152j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Näther C.; Jess I.; Seyfarth L.; Bärwinkel K.; Senker J. Trimorphism of betamethasone valerate: preparation, crystal structures, and thermodynamic relations. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 366–373. 10.1021/cg501464m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-discussion/crixivan-epar-scientific-discussion_en.pdf (accessed April 12, 2020).

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/jevtana-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed April 12, 2020).

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/mekinist-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed April 12, 2020).

- Brychczynaska M.; Davey R. J.; Pidcock E. A study of dimethylsulfoxide solvates using the Cambridge structural database (CSD). CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 1479–1484. 10.1039/C1CE05464C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jagdev Singh J.; Swargam S.; Rajesh Kumar T.; Mohan P.; Deorao Z. S.; Shankar S. A.. 4-(4-{3-[4-chloro-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]ureido}phenoxy)-N2-methylpyridine-2-carboxamide dimethyl sulphoxide solvate. WO 2011092663 A2, August 4, 2011.

- Srinivasan T. R.; Sajja E.; Gutta M.. Process for the preparation of 4-[4-({[4-chloro-3-trifluoromethyl)phenyl]carbamoyl}amino)-3-fluoxophenoxy]-N-methylpyridine-2-carboxamide and its polymorphs thereof. WO 2016051422 A2, April 7, 2016.

- Bi F.; Qin S.; Gu S.; Bai Y.; Chen Z.; Wang Z.; Ying J.; Lu Y.; Meng Z.; Pan H.; Yang P.; Zhang H.; Chen X.; Xu A.; Liu X.; Meng Q.; Wu L.; Chen F. Donafenib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: An open-label, randomized, multicenter phase II/III trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 4506. 10.1200/jco.2020.38.15_suppl.4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S. J.; Gale P. A.; Light M. E. Ortho-phenylenediamine bis-urea-carboxylate: a new reliable supramolecular synthon. CrystEngComm 2005, 7, 586–591. 10.1039/b511932d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capacci-Daniel C.; Dehghan S.; Wurster V. M.; Basile J. A.; Hiremath R.; Sarjeant A. A.; Swift J. A. Halogen/methyl exchange in a series of isostructural 1,3-bis(m-dihalophenyl)ureas. CrystEngComm 2008, 10, 1875–1880. 10.1039/b812138a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomos M. A.; Watts T. A.; Swift J. A. Ortho-substituent effects on diphenylurea packing motifs. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 5065–5072. 10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar K.; Sridhar B.; Rao A. K. S. B.; Reddy M. P. Sorafenib and its tosylate salt: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 2011, C67, 29–32. 10.1107/s0108270110047451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P.; Qin C.; Du S.; Jia L.; Qin Y.; Gong J.; Wu S. Crystal Structure, Stability and Desolvation of the Solvates of Sorafenib Tosylate. Crystals 2019, 9, 367. 10.3390/cryst9070367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M.-Y.; Wu S.-X.; Zhou X.-B.; Gu J.-M.; Hu X.-R. Comparison of the crystal structures of the potent anticancer and anti-angiogenic agent regorafenib and its monohydrate. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 2016, 72, 291–296. 10.1107/s2053229616003727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Xu C.-Q.; Yu J.; Pui Y.; Chen H.; Wang S.; Zhu A. D.; Li J.; Qian F. Impact of a single hydrogen substitution by fluorine on the molecular interaction and miscibility between sorafenib and polymers. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 318–326. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K.-S.; Britton D.; Etter M. C.; Byrn S. R. Polymorphic characterization and structural comparisons of the non-linear optically active and inactive forms of two polymorphs of 1,3-bis(m-nitrophenyl)urea. J. Mater. Chem. 1995, 5, 379–383. 10.1039/jm9950500379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rafilovich M.; Bernstein J.; Harris R. K.; Apperley D. C.; Karamertzanis P. G.; Price S. L. Groth’s Original Concomitant Polymorphs Revisited. Cryst. Growth Des. 2005, 5, 2197–2209. 10.1021/cg050151j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X. Y.; Feng W. D.; Dai X. J.. Preparation methods of methyl-d3-amine and salts thereof. WO 2011113369 A1, Sep 22, 2011.

- Fulmer G. R.; Miller A. J. M.; Sherden N. H.; Gottlieb H. E.; Nudelman A.; Stoltz B. M.; Bercaw J. E.; Goldberg K. I. NMR chemical shifts of trace impurities: common laboratory solvents, organics, and gases in deuterated solvents relevant to the organometallic chemist. Organometallics 2010, 29, 2176–2179. 10.1021/om100106e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy L. S.; Chandran S. K.; George S.; Babu N. J.; Nangia A. Crystal Structures ofN-Aryl-N′-4-Nitrophenyl Ureas: Molecular Conformation and Weak Interactions Direct the Strong Hydrogen Bond Synthon. Cryst. Growth Des. 2007, 7, 2675–2690. 10.1021/cg070155j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman J.; Day G. M. Static and lattice vibrational energy differences between polymorphs. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 5154–5165. 10.1039/c5ce00045a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S. J.; Gale P. A.; Light M. E. Anion-binding modes in a macrocyclic amidourea. Chem. Commun. 2006, 4344–4346. 10.1039/b610938a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custelcean R. Urea-functionalized crystalline capsules for recognition and separation of tetrahedral oxoanions. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2173–2182. 10.1039/c2cc38252k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendola V.; Fabbrizzi L.; Mosca L. Anion recognition by hydrogen bonding: urea-based receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3889–3915. 10.1039/b822552b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai S. K.; Gunnam A.; Mannava M. K. C.; Nangia A. K. Improving the dissolution rate of the anticancer drug dabrafenib. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 1035–1046. 10.1021/acs.cgd.9b01365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.