Abstract

Background

Lake Tanganyika belongs to the East African Great Lakes and is well known for harbouring a high proportion of endemic and morphologically distinct genera, in cichlids but also in paludomid gastropods. With about 50 species these snails form a flock of high interest because of its diversity, the question of its origin and the evolutionary processes that might have resulted in its elevated amount of taxa. While earlier debates centred on these paludomids to be a result of an intralacustrine adaptive radiation, there are strong indications for the existence of several lineages before the lake formation. To evaluate hypotheses on the evolution and radiation the detection of actual adaptations is however crucial. Since the Tanganyikan gastropods show distinct radular tooth morphologies hypotheses about potential trophic specializations are at hand.

Results

Here, based on a phylogenetic tree of the paludomid species from Lake Tanganyika and adjacent river systems, the mechanical properties of their teeth were evaluated by nanoindentation, a method measuring the hardness and elasticity of a structure, and related with the gastropods’ specific feeding substrate (soft, solid, mixed). Results identify mechanical adaptations in the tooth cusps to the substrate and, with reference to the tooth morphology, assign distinct functions (scratching or gathering) to tooth types. Analysing pure tooth morphology does not consistently reflect ecological specializations, but the mechanical properties allow the determination of eco-morphotypes.

Conclusion

In almost every lineage we discovered adaptations to different substrates, leading to the hypothesis that one main engine of the flock’s evolution is trophic specialization, establishing distinct ecological niches and allowing the coexistence of taxa.

Keywords: Functional morphology, Nanoindentation, Mechanical properties, Gastropoda, Trophic specialisation, Adaptive radiation

Background

Hypotheses on how biodiversity relates with the temporal and spatial “filling” of available habitats and annidation itself, i.e. the actual formation of ecological niches as a combined process of internal and external factors, is paramount for understanding how species evolve under geographical and ecological conditions [1–3]. Addressing this topic has seen various approaches based on vertebrates, such as the studies on Darwin finches [4–9], the cichlid fishes in the East African lakes [10–13] and Nicaragua [14–16] or Anolis lizards [17–19]. These species flocks [cf. 20] are usually regarded as examples of adaptive radiations, the evolution of ecological and phenotypic diversity within a rapidly multiplying lineage, thus linking speciation and ecology [21–26].

However, even though the majority of all known animals are invertebrates [27, 28], fewer model systems were on focus (with exceptions, e.g. [29, 30] on crickets). There are however spectacular examples of invertebrate species flocks exhibiting a great diversity, especially among molluscs [see also 31, 32], the lacustrine and riverine freshwater gastropods on Sulawesi [33–38], Madagascar [39], in the Thai rivers [40, 41], or “ancient” Lake Tanganyika [42–44]. The latter is well known for its unique assemblage of endemic species and has been a natural laboratory for research on the drivers of evolution for decades. It harbours paludomid gastropods (Fig. 1) which triggered many expeditions and subsequently malacological descriptions [e.g. 45–60] and a long-lasting controversy about the origin and evolution of the lake and its fauna. Due to their marine-like appearance (termed “thalassoid” by [45] and “halolimnic” by [61]) many earlier authors addressed the possibility of a marine origin of the Lake Tanganyika fauna and discussed the causes of the thalassoid appearance of its endemic molluscs. However, this eventually led to the refutation of Moore’s controversial hypothesis [61–63] of the lake being once directly connected to the ocean [see e.g. in 64–68].

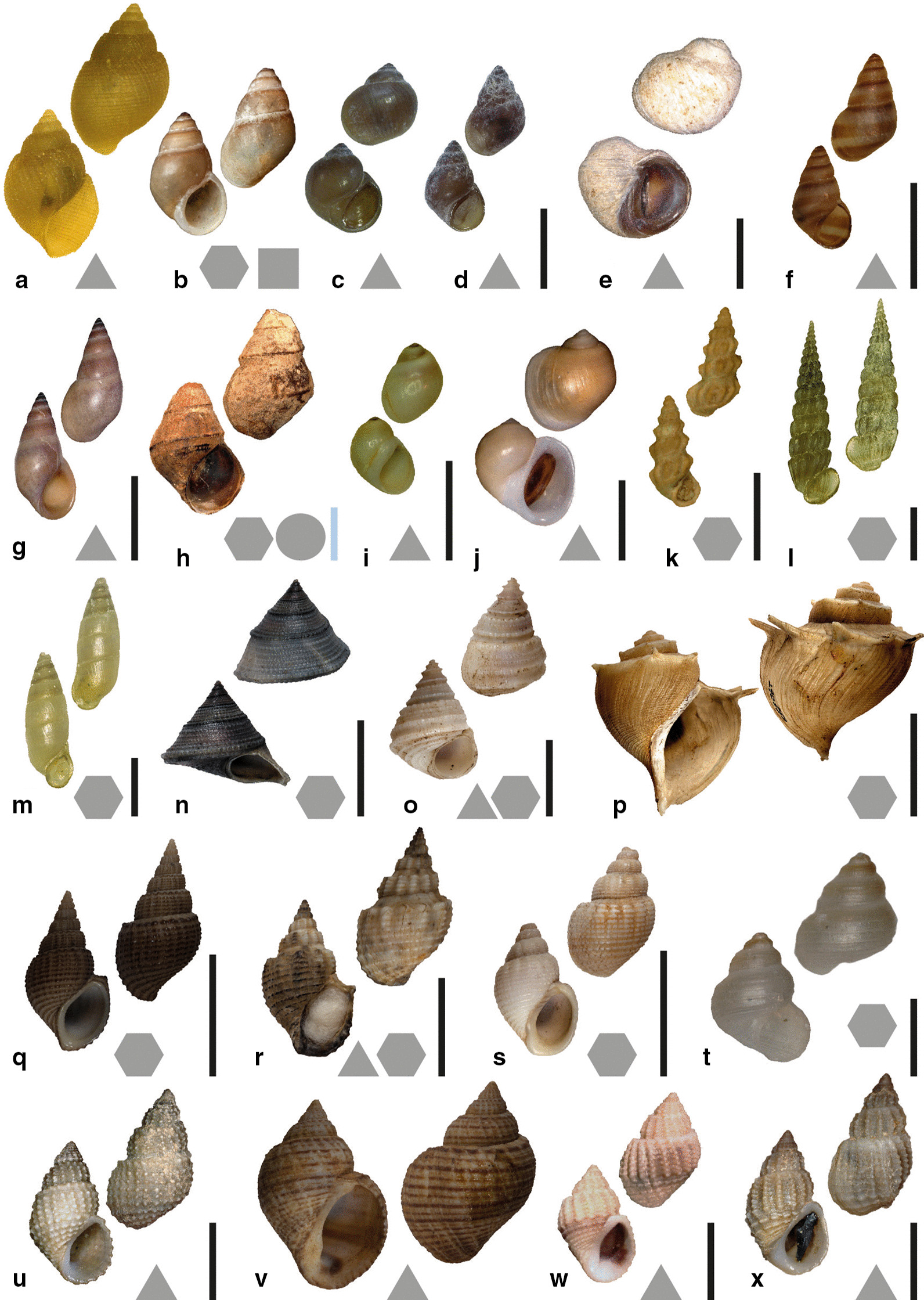

Fig. 1.

Shells of examined species. Black scale bars: from Lake Tanganyika. Blue scale bar: from adjacent river systems. Forms next to the letters a–x indicate preferred feeding substrate (circle = mud, hexagon = sand, square = plants, triangle = rock). a Bridouxia ponsonbyi ZMB 220.137-1, b B. grandidieriana BMNH 1889.6.23.57-61, c B. rotundata ZMB 220.063-3, d B. praeclara DBL 19-4, e Spekia zonata ZMB 220.007-2, f Leloupiella minima ZMB 220.008-3, g Reymondia horei ZMB 220.007-1, h Cleopatra johnstoni ZMB 220.102, i Stanleya neritinoides ZMB 102.624-1, j Tanganycia rufofilosa ZMB 102.621-1, k Martelia tanganyicensis ZMB 220.134-1, l Anceya giraudi ZMB 220.000-1, m Syrnolopsis lacustris ZMB 220.046-1, n Chytra kirki SMF 290543-1, o Limnotrochus thomsoni SMF 290542-1, p Tiphobia horei SMF 290550-1, q Paramelania iridescens SMF 290,538, r P. damoni SMF 290531-2, s P. crassigranulata SMF 290528-1, t Mysorelloides multisulcata DBL without number, u Lavigeria spinulosa ZMB 220114, v L. grandis SMF 292827-1, w L. nassa ZMB 220.172-1, x L. livingstoniana ZMB 220116; Scale bars: a–d, f, k, l, m = 2.5 mm; e = 5 mm; g, i, j, n, o, v, w = 10 mm; h = 5 mm; p–s = 20 mm, t = 0.75 mm; u, x = 6 mm

For a long time the idea that this largest and deepest of the African lakes has supplied its gastropod diversity with a stable inland environment and offered unique opportunities for within-lake diversification (“ancient endemic radiation” see [65, 69]) resulting in a truly “adaptive” radiation [cf. 70, 71] was common [e.g. 72–86]. However, strong evidence for an ancient origin of disparity and diversity in this flock has been presented, indicating the existence of major gastropod lineages before the formation of the lake itself or its proto-lakes. The oldest formation estimates are 9–12 Mya [87–89], while more recent studies date the pre-rift formation to 4–11 Mya and the earliest onset of a true rifting activity to 5.5 Mya [90–93]. With a molecular clock approach in support [42], this alternative hypothesis of the former existence of several originally riverine paludomid lineages later inhabiting the lake and bringing possible adaptations to former river environments with them was suggested by [43, 44].

To allocate hypotheses about paludomid evolution and radiations—especially in the context of adaptive radiations—the identification of actual adaptation is crucial. Morphological structures associated with feeding, such as e.g. bills or skulls in birds, vomer bones in cichlid fishes or teeth in mammals, can exhibit adaptations and indicate trophic specialization. They serve as an interface between the organism and its ingesta (food, minerals) and, as they provided insights into functional adaptations and hence evolution, are of high research interest in various groups [e.g. 94–97 on Darwin’s finches, 98 on oviraptorosaurian dinosaurs, 99 on cichlid fish].

The gastropods radula, one important synapomorphy of the Mollusca, acts as such an interface, mechanically processing ingesta and directly linking the organism with its food. Various muscles control the motion of this feeding organ, pulling the chitinous radular membrane with rows of small embedded radular teeth [100] across an odontophoral cartilage (Fig. 2a). As teeth are in direct contact with the ingesta, their morphology can often be directly linked with the animal’s ecology and can reflect various transitions from zoovorous to herbivorous traits [101–106]. Form together with the tooth’s position and chemical composition are widely considered adaptive to food and are hence closely associated with feeding strategies, competitor avoidance and thus trophic specialization [107–118].

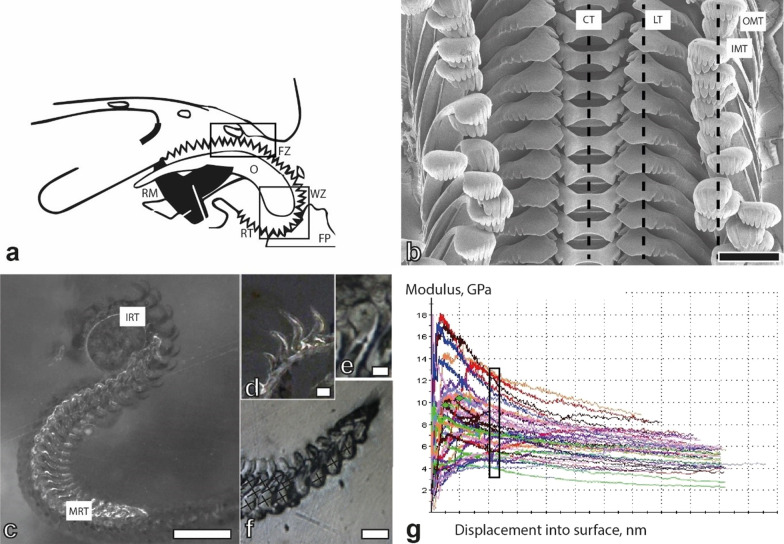

Fig. 2.

a Schematic drawing of the radula when feeding, b Taenioglossan radula of Spekia zonata (ZMH 150008/999-2), black line = area of nanoindentation for central, lateral, and marginal teeth, c Radula (ZMB220.143-2) embedded in epoxy resin and polished for nanoindentation (longitudinal section along the radula) with (d–f) magnification of some tested areas (e with nanoindentation mark; f crosses indicate points of indentation), g Representative results as nanoindentation measurement curves for basis, stylus, and cusps of central teeth (Young’s modulus, GPa, versus displacement into tooth material). The values for the cusps within the indentation depth of 480–520 nm were used for further calculation. Scale bars: b = 100 µm; c = 250 µm; d, e = 30 µm; f = 60 µm. CT central tooth, FP food particle, FZ formation zone, IMT inner marginal tooth, IRT immature radular teeth, LT lateral tooth, MRT mature radular teeth, O odontophore, OMT outer marginal tooth, RM radular muscles, RT radular teeth, WZ working zone

Strong indications for trophic specialization in the context of gastropod adaptive radiations have been described for the radular tooth morphologies of lacustrine Tylomelania from Sulawesi [33, 35, 38], the riverine gastropods from Kaek River [40], and marine Dendronotus [119]. For the Lake Tanganyikan paludomids hypotheses on the potential influence of trophic specialization on the evolution of this flock are consequential, since these species show an extraordinarily high interspecific diversity in tooth morphologies [e.g. 44, 120]. These shapes can often be related with the gastropods’ specific feeding substrates (soft, mixed or solid) since teeth as highly functionate interfaces do not only interact with the food but also with the substrate the food is attached to [121, 122]. In addition, recent studies on the paludomid tooth anchorages in the radular membrane, which are also diverse between taxa, relate this connecting area with the gastropod’s specific feeding substrate [123].

In addition to morphology, the structural composition also influences functionality. For reconstructing the evolutionary history of the African Paludomidae and to develop hypotheses on the role of trophic specialisation in their evolution, we here identified the hardness and elasticity of taenioglossan radular teeth from 24 species belonging to this flock utilising nanoindentation, a technique previously employed to identify local mechanical properties of various biological materials [e.g. 124–130]. Results, with reference to morphology, allow the assignment of distinct functions to certain tooth types. The identification of mechanical adaptations in their cusps to the preferred feeding substrate allowed the establishment of eco-morphotypes. Our results strongly indicate that one main engine of the flock’s evolution is trophic specialization, allowing the coexistence of species.

Results

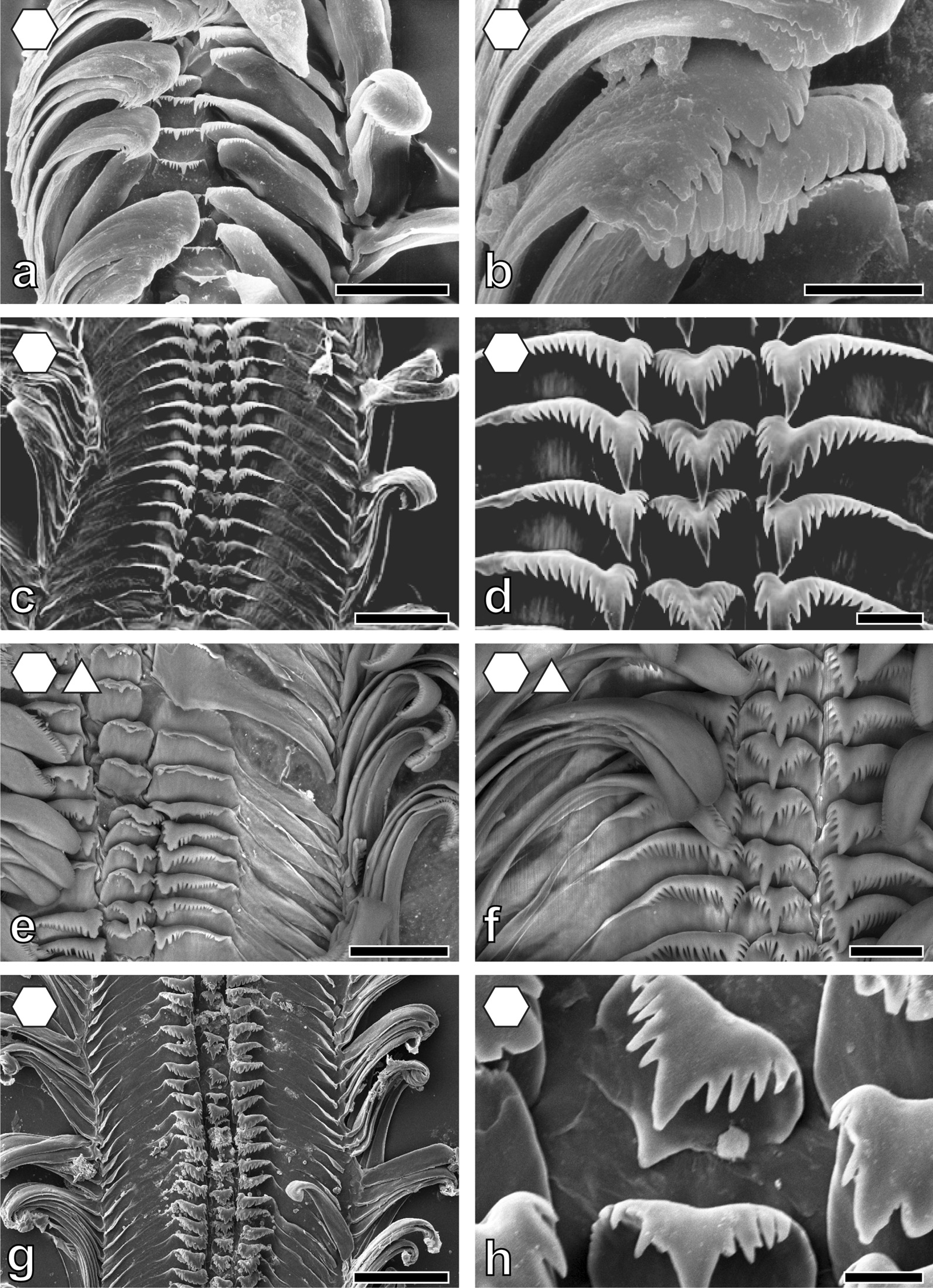

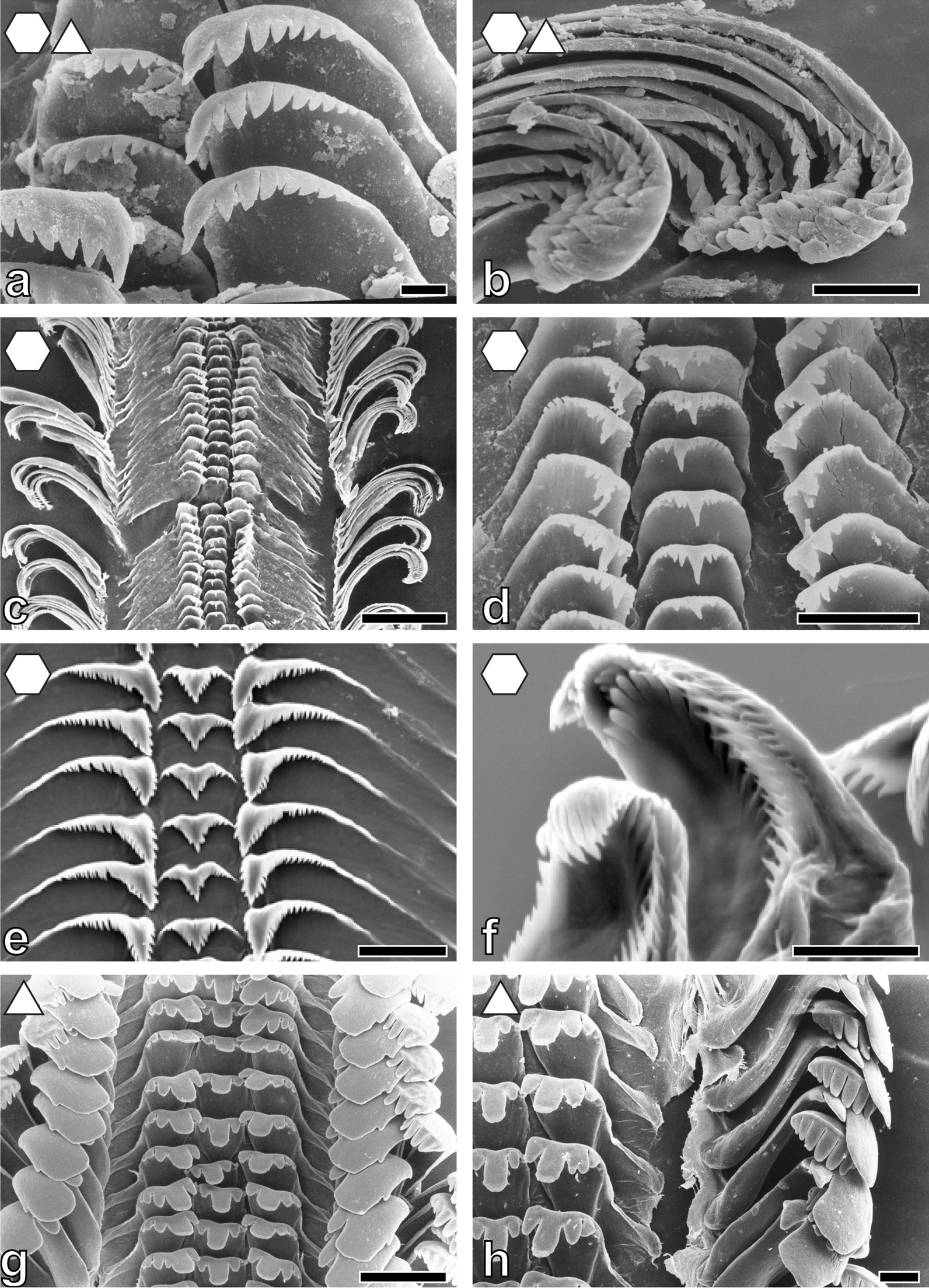

Tooth’s morphologies (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) can be correlated with the substrate-preference. Grazing on stones usually correlates with certain morphologies of the central tooth, either involving a spatulate, prominent central denticle (Nassopsini and Reymondia; Figs. 4, 8), or few or no denticles (Bridouxia ponsonbyi, B. rotundata, B. praeclara, Spekia, and Leloupiella; Figs. 3, 4), and with laterals bearing a prominent denticle (Nassopsini, Reymondia, Bridouxia; Figs. 3, 4, 8). Few solid-substrate feeders (Stanleya and Tanganyicia; Fig. 5) display central and lateral teeth with long denticles of the same size. Here, teeth are rather similar in their morphology to teeth of gastropods foraging on sand, possessing central, lateral, and marginal teeth with small or finger-like denticles at each cusp (Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8). All mixed substrate feeders, Paramelania damoni, Limnotrochus thomsoni, and Bridouxia grandidieriana, display small, finger-like denticles as well (Figs. 3, 6, 7).

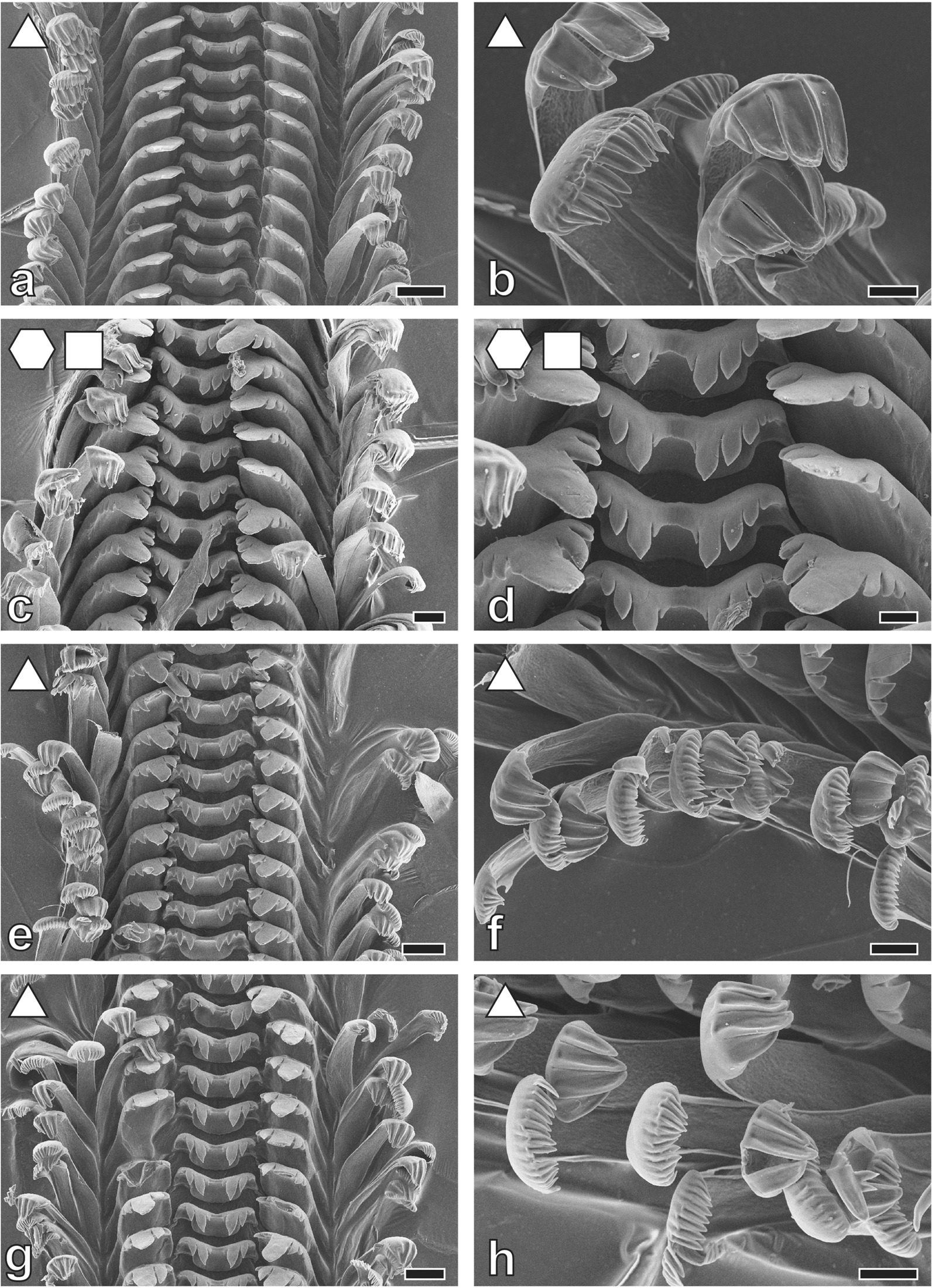

Fig. 3.

Radular teeth of: a, b Bridouxia ponsonbyi ZMB 220.137-1, a overview, b marginals; c, d B. grandidieriana ZMB 220.139-4, c overview, d centrals and laterals; e, f B. rotundata ZMB 220063-1, e overview, f marginals; g, h B. praeclara ZMB 220.063-2, g overview, h marginals. Scale bars: a = 40 μm; b, d, f, h = 10 μm; c, e, g = 20 μm. Forms indicate preferred feeding substrate (circle = mud, hexagon = sand, square = plants, triangle = rock)

Fig. 4.

Radular teeth of: a, b Spekia zonata ZMH 150008/999-2, a overview, b marginals; c, d Leloupiella minima ZMB 220.135, c overview, d marginals; e, f Reymondia horei ZMB 220.147-1, e centrals and laterals, f marginals; g, h Cleopatra johnstoni ZMB 220.102-1, g overview, h marginals. Scale bars: a = 100 μm; b = 50 μm; c, d = 10 μm; e, f = 30 μm; g = 40 μm; h = 20 μm. Forms indicate preferred feeding substrate (circle = mud, hexagon = sand, square = plants, triangle = rock)

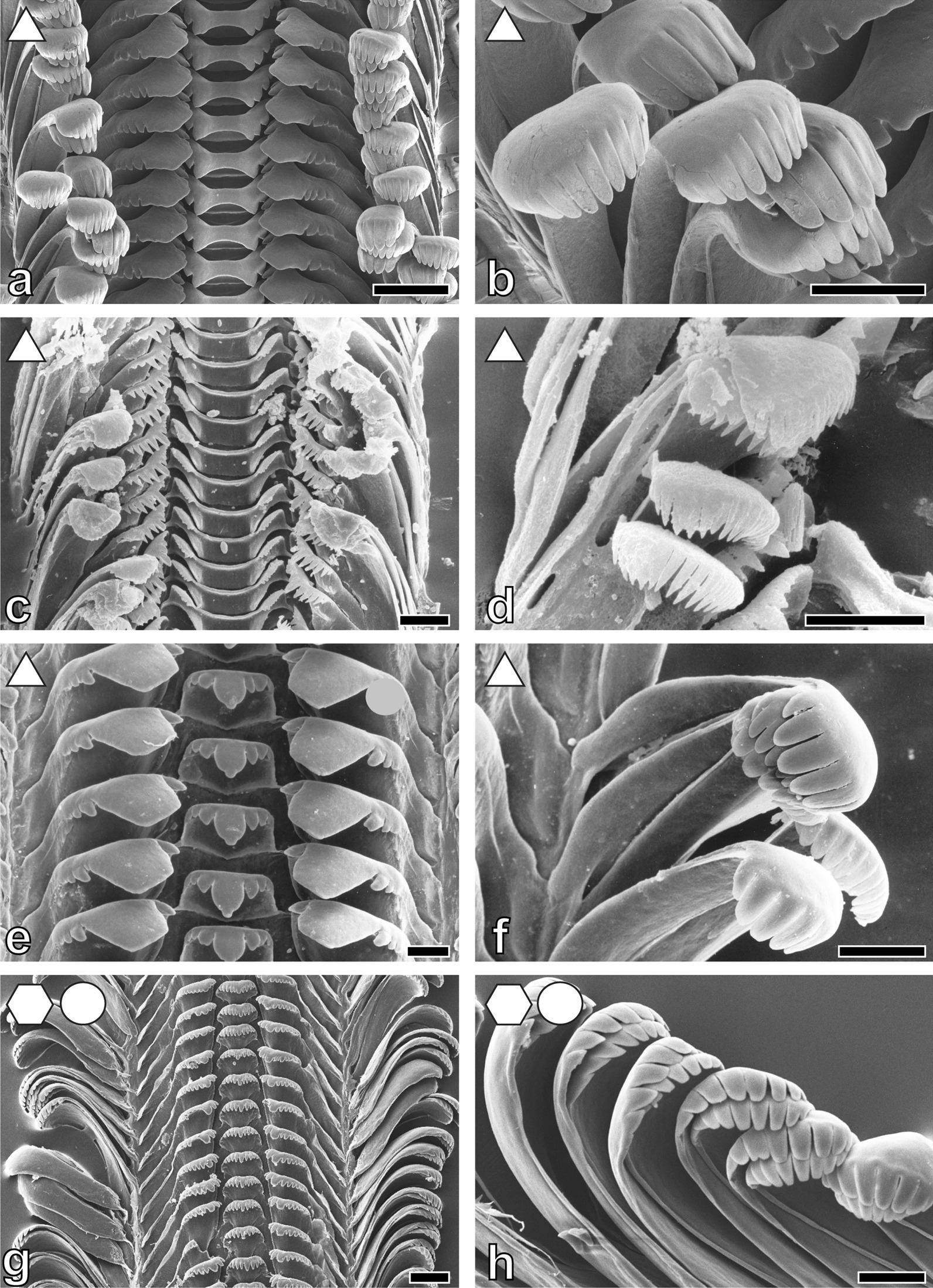

Fig. 5.

Radular teeth of: a, b Stanleya neritinoides MRAC without number, a centrals and laterals, b marginals; c, d Tanganycia rufofilosa, c centrals and laterals, d marginals; e, f Martelia tanganyicensis ZMB 220.133-1, e overview, f laterals and marginals; g, h. Anceya giraudi ZMB 220.132, g overview, h centrals and laterals. Scale bars: a–c, e, f, h = 10 μm; d, g = 30 μm. Forms indicate preferred feeding substrate (circle = mud, hexagon = sand, square = plants, triangle = rock)

Fig. 6.

Radular teeth of: a, b Syrnolopsis lacustris ZMB 220.131, a overview, b marginals; c, d Chytra kirki IRSNB no. 63, c overview, d centrals and laterals; e, f Limnotrochus thomsoni ZMB 107.102, e overview, f centrals and laterals; g, h Paramelania iridescens ZMB 220.053, g overview, h centrals. Scale bars: a = 30 μm; b, h = 10 μm; c = 100 μm; d, f = 20 μm; e = 50 μm; g = 120 μm. Forms indicate preferred feeding substrate (circle = mud, hexagon = sand, square = plants, triangle = rock)

Fig. 7.

Radular teeth of: a, b Paramelania damoni ZMH without number, a centrals and laterals, b marginals; c, d P. crassigranulata ZMB 220.037-1, c overview, d centrals and laterals; e, f Mysorelloides multisulcata IRSNB no. 126, e centrals and laterals, f marginals; g, h Lavigeria spinulosa ZMB 220.051, g overview, h marginals. Scale bars: a, f = 10 μm; b, d, h = 30 μm; c, g = 100 μm; e = 20 μm. Forms indicate preferred feeding substrate (circle = mud, hexagon = sand, square = plants, triangle = rock)

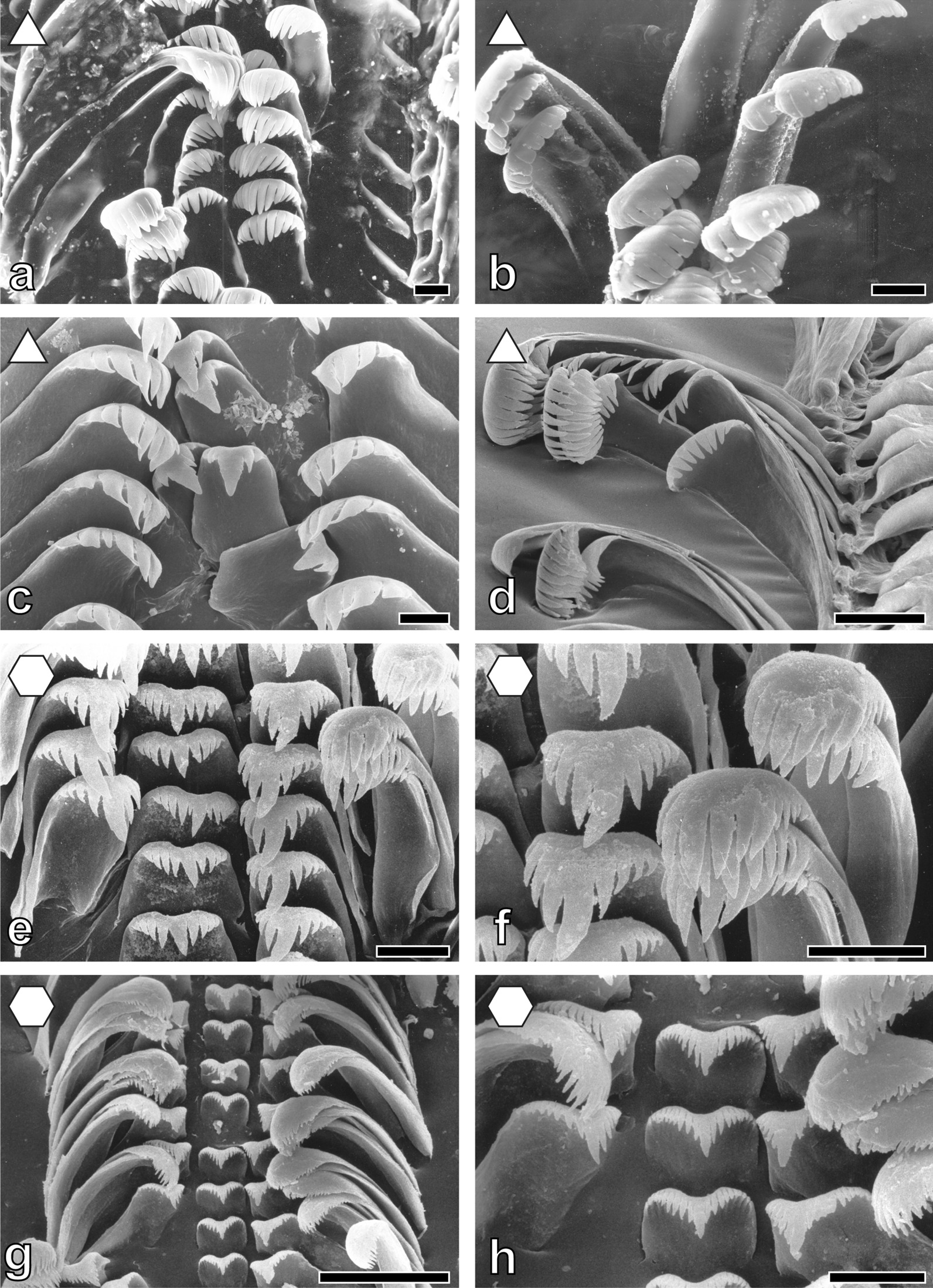

Fig. 8.

Radular teeth of: a, b Lavigeria grandis ZMH 154657/999, a overview, b laterals and marginals; c, d L. nassa ZMB 220.074, c overview, d laterals and marginals; e, f L. livingstoniana ZMB 220.117-1, e overview, f marginals and laterals. Scale bars: a = 100 μm; b = 50 μm; c, d, f = 30 μm; e = 100 μm. Forms indicate preferred feeding substrate (circle = mud, hexagon = sand, square = plants, triangle = rock)

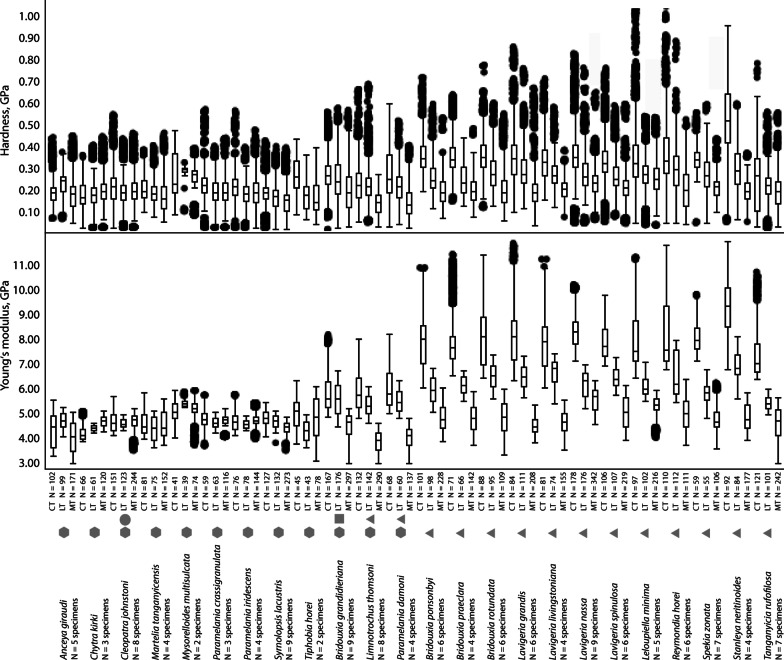

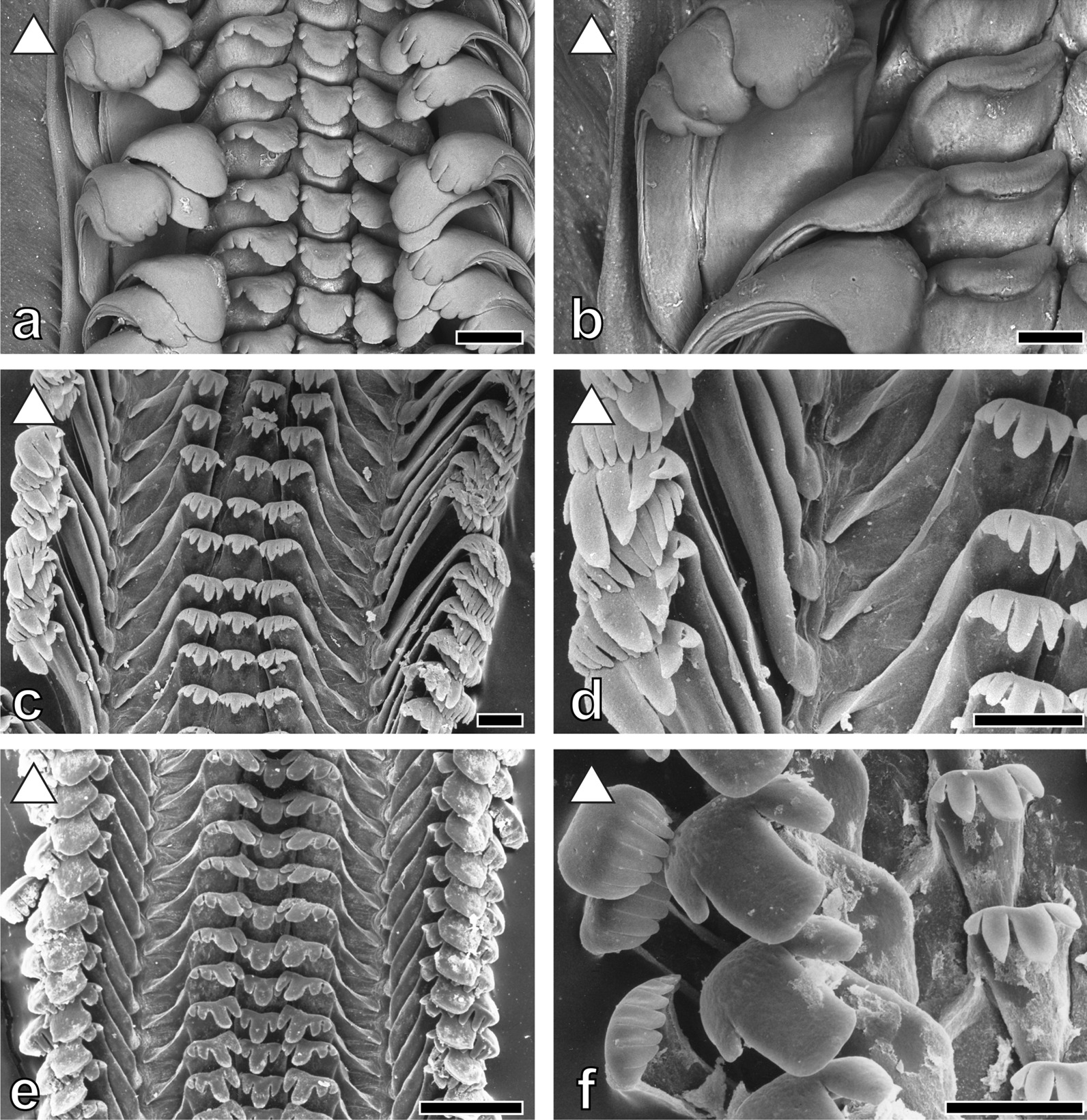

Nanoindentation experiments provided the Young's modulus (E) as a measure of the stiffness of a solid material, describing the relationship between mechanical stress and indentation depth, and the hardness (H), the measure of the resistance to local plastic deformation. Statistical analysis of these parameters revealed normal distribution for both. Significant differences between all tooth cusps (Fig. 9) of the separate substrate feeder groups (solid, soft, and mixed) regarding both E and H were detected (p < 0.0001, F-ratio: 2, df: 59,578.92 for E, df: 20,833.04 for H). Paludomids feeding on sand have comparatively soft and flexible tooth cusps (mean ± std. deviation; E = 4.57 ± 0.45 GPa, H = 0.18 ± 0.07 GPa), species foraging on stone have the stiffest and hardest tooth cusps (E = 6.08 ± 1.52 GPa, H = 0.26 ± 0.11 GPa), and mixed substrate feeders are intermediate (E = 4.94 ± 0.99 GPa, H = 0.20 ± 0.09 GPa).

Fig. 9.

Results of nanoindentation, hardness (GPa) and Young’s modulus (GPa). (left) Comparing all tooth cusps of species feeding on mixed, soft, and solid substrate; (right) comparing all central to all lateral and all marginal tooth cups. Letters are connecting letters from Tukey–Kramer test. N = quantity of tested tooth cusps

Significant differences were found between all central, lateral, and marginal tooth cusps (Fig. 9) (p < 0.0001, F-ratio: 2, df: 70,177.01 for E, df: 24,978.35 for H). Marginal teeth are comparable soft and flexible (E = 4.68 ± 0.63 GPa, H = 0.19 ± 0.08 GPa), the central teeth are comparatively hard and stiff (E = 6.48 ± 1.84 GPa, H = 0.28 ± 0.13 GPa), and the lateral ones are intermediate (E = 5.54 ± 0.92 GPa, H = 0.24 ± 0.09 GPa).

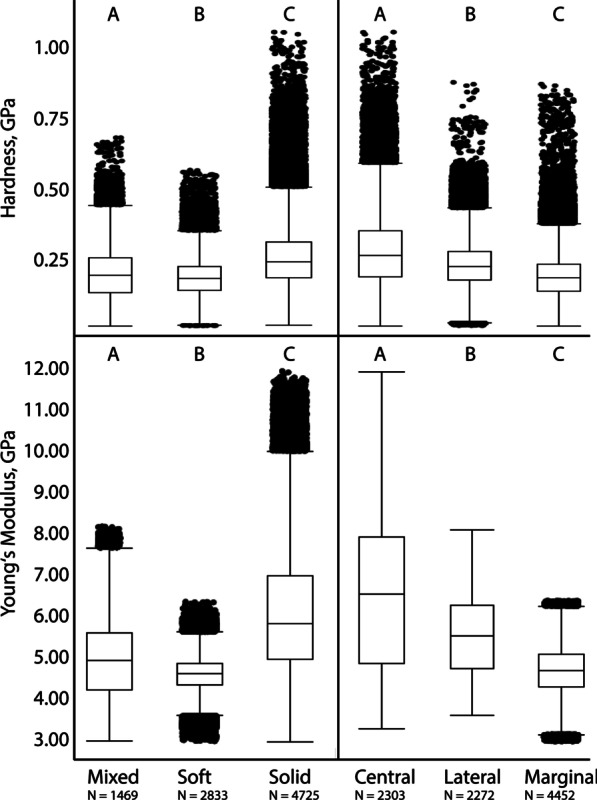

Comparing the mechanical properties within each species we consistently detect significant differences (p < 0.0001, F-ratio: 2) between central, lateral, and marginal tooth cusps (see Table 1 for all E and H values, df, and connecting letters from Tukey–Kramer test). All species feeding on solid substrate clearly display gradients in their radular properties, the stiffest and hardest parts are always the central tooth cusps, followed by the lateral ones; the softest and most flexible parts are the marginal cusps (see additionally Figs. 10, 11). In the mixed substrate feeders there’s a similar situation, central cusps are hard and stiff, lateral ones intermediate, and marginals soft and flexible; but central and lateral tooth cusps are not as distinct as in the solid substrate feeders. Species foraging on sand have quite similar mechanical properties in their tooth cusps and are more homogenous (Table 1, Figs. 10, 11).

Table 1.

Preferred feeding substrate, Mean ± Std. Dev. for Young's modulus E (GPa) and hardness H (GPa) for each species and tooth type

| Species and structure | Modulus, GPa Mean ± Std. Dev |

Hardness, GPa Mean ± Std. Dev |

(A) Connecting letters for comparison of E within species | (A) Connecting letters for comparison of H within species | (B) Connecting letters for comparison of E between all species and tooth types p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 71 df: 20,217.82 |

(B) Connecting letters for comparison of H between all species and tooth types p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 71 df: 2734.555 |

Feeding substrate | Species and structure | Modulus, GPa Mean ± Std. Dev |

Hardness, GPa Mean ± Std. Dev |

(A) Connecting letters for comparison of E within species | (A) Connecting letters for comparison of H within species | (B) Connecting letters for comparison of E between all species and tooth types p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 71 df: 20,217.82 |

(B) Connecting letters for comparison of H between all species and tooth types p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 71 df: 2734.555 |

Feeding substrate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bridouxia grandidieriana N = 9 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 9409.887 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 1623.203 |

Mixed |

Bridouxia ponsonbyi N = 6 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 24,848.35 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 6166.873 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 167 |

5.81 ± 0.81 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | A | A | S | JK |

CT Cusp N = 101 |

7.81 ± 0.99 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | A | A | G | CDE | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 176 |

5.55 ± 0.66 | 0.25 ± 0.10 | B | B | T | QR |

LT Cusp N = 98 |

5.93 ± 0.52 | 0.26 ± 0.08 | B | B | Q | NOP | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 297 |

4.47 ± 0.51 | 0.19 ± 0.08 | C | C | M1 | D1E1 |

MT Cusp N = 228 |

4.81 ± 0.56 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | C | C | A1B1C1 | B1C1D1 | ||||

|

Limnotrochus thomsoni N = 8 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 25,875.14 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 3296.830 |

Mixed |

Bridouxia praeclara N = 4 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 20,873.79 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 4929.307 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 132 |

5.87 ± 0.80 | 0.23 ± 0.09 | A | A | R | T |

CT Cusp N = 71 |

7.92 ± 1.03 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | A | A | F | CDEF | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 142 |

5.31 ± 0.42 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | B | B | X | VWX |

LT Cusp N = 66 |

6.11 ± 0.35 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | B | B | O | RS | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 290 |

3.83 ± 0.42 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | C | C | T1 | M1 |

MT Cusp N = 142 |

4.77 ± 0.55 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | C | C | C1D1E1 | ZA1B1C1 | ||||

|

Paramelania damoni N = 4 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 11,870.71 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 1684.680 |

Mixed |

Bridouxia rotundata N = 6 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 20,354.73 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 4417.627 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 68 |

6.00 ± 0.81 | 0.26 ± 0.12 | A | A | P | MN |

CT Cusp N = 88 |

8.04 ± 1.14 | 0.36 ± 0.09 | A | A | DE | BC | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 60 |

5.48 ± 0.45 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | B | B | UV | VWX |

LT Cusp N = 95 |

6.50 ± 0.52 | 0.28 ± 0.09 | B | B | L | J | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 137 |

4.03 ± 0.42 | 0.14 ± 0.07 | C | C | S1 | M1 |

MT Cusp N = 109 |

4.78 ± 0.70 | 0.20 ± 0.08 | C | C | A1B1C1D1 | A1B1C1 | ||||

|

Anceya giraudi N = 5 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 1598.901 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 560.1817 |

Soft |

Lavigeria grandis N = 6 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 38,217.95 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 3899.479 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 102 |

4.30 ± 0.69 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | A | A | P1Q1 | E1F1 |

CT Cusp N = 84 |

8.07 ± 1.11 | 0.34 ± 0.13 | A | A | D | EF | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 99 |

4.67 ± 0.32 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | B | B | F1 | TU |

LT Cusp N = 111 |

6.45 ± 0.46 | 0.29 ± 0.09 | B | B | LM | I | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 171 |

4.03 ± 0.59 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | C | C | S1 | G1H1I1 |

MT Cusp N = 208 |

4.50 ± 0.36 | 0.19 ± 0.08 | C | C | L1M1 | D1E1F1 | ||||

|

Chytra kirki N = 3 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 8124.837 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 157.4867 |

Soft |

Lavigeria livingstoniana N = 4 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 20,914.61 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 3411.923 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 66 |

4.17 ± 0.26 | 0.17 ± 0.06 | C | C | R1 | J1K1 |

CT Cusp N = 81 |

7.74 ± 0.97 | 0.33 ± 0.09 | A | A | H | H | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 61 |

4.38 ± 0.12 | 0.17 ± 0.06 | B | B | N1O1 | I1J1 |

LT Cusp N = 74 |

6.69 ± 0.45 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | B | B | K | JK | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 120 |

4.66 ± 0.21 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | A | A | F1G1 | E1F1 |

MT Cusp N = 155 |

4.62 ± 0.48 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | C | C | G1H1 | ZA1B1 | ||||

|

Cleopatra johnstoni N = 8 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 252.9942 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 205.9801 |

Soft |

Lavigeria nassa N = 9 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 44,599.76 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 4134.603 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 151 |

4.65 ± 0.42 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | B | A | F1G1H1 | VWXY |

CT Cusp N = 178 |

8.40 ± 0.85 | 0.36 ± 0.11 | A | A | B | B | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 123 |

4.56 ± 0.18 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | C | C | I1K1 | F1G1H1 |

LT Cusp N = 176 |

6.19 ± 0.53 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | B | B | N | KL | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 244 |

4.68 ± 0.31 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | A | B | F1 | D1E1F1 |

MT Cusp N = 342 |

5.53 ± 0.50 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | C | C | TU | S | ||||

|

Martelia tanganyicensis N = 4 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 116.8776 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 244.2914 |

Soft |

Lavigeria spinulosa N = 6 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 29,162.21 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 3134.948 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 81 |

4.55 ± 0.49 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | A | A | I1J1K1L1 | XYZA1 |

CT Cusp N = 106 |

7.88 ± 0.68 | 0.33 ± 0.10 | A | A | F | GH | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 75 |

4.35 ± 0.48 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | B | B | O1P1 | E1F1G1H1 |

LT Cusp N = 107 |

6.42 ± 0.40 | 0.26 ± 0.08 | B | B | M | MN | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 152 |

4.52 ± 0.53 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | A | C | K1L1 | J1K1 |

MT Cusp N = 219 |

5.01 ± 0.63 | 0.21 ± 0.07 | C | C | Z | WXY | ||||

| Mysorelloides multisulcata N = 2 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 337.2236 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 109.8094 |

Soft |

Leloupiella minima N = 5 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 15,762.00 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 739.7396 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 41 |

5.06 ± 0.43 | 0.26 ± 0.10 | C | B | YZ | LMNO |

CT Cusp N = 92 |

7.99 ± 1.22 | 0.34 ± 0.16 | A | A | E | F | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 39 |

5.39 ± 0.13 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | A | A | VW | IJ |

LT Cusp N = 84 |

6.06 ± 0.39 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | B | B | OP | KLM | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 74 |

5.12 ± 0.35 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | B | C | Y | PQR |

MT Cusp N = 177 |

5.30 ± 0.37 | 0.25 ± 0.09 | C | C | X | OPQ | ||||

|

Paramelania crassigranulata N = 3 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 212.7667 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 221.3736 |

Soft |

Reymondia horei N = 6 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 17,244.19 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 2694.074 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 59 |

4.76 ± 0.36 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | A | A | B1C1D1E1 | TU |

CT Cusp N = 97 |

8.21 ± 1.34 | 0.35 ± 0.15 | A | A | C | BCD | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 63 |

4.61 ± 0.21 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | C | B | F1G1 | C1D1E1F1 |

LT Cusp N = 102 |

6.48 ± 0.85 | 0.29 ± 0.11 | B | B | L | I | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 116 |

4.67 ± 0.24 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | B | B | G1H1I1J1 | D1E1F1 |

MT Cusp N = 216 |

4.99 ± 0.65 | 0.20 ± 0.09 | C | C | Z | YZ | ||||

|

Paramelania iridescence N = 4 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 401.3311 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 218.9492 |

Soft |

Spekia zonata N = 7 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 11,499.22 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 1089.918 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 76 |

4.65 ± 0.38 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | B | A | F1G1H1 | UV |

CT Cusp N = 110 |

8.09 ± 0.65 | 0.34 ± 0.07 | A | A | D | DEFG | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 78 |

4.55 ± 0.18 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | C | B | K1L1 | E1F1G1H1 |

LT Cusp N = 112 |

5.78 ± 0.42 | 0.27 ± 0.09 | B | B | S | JKLM | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 144 |

4.73 ± 0.24 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | A | B | E1 | E1F1G1 |

MT Cusp N = 111 |

4.74 ± 0.50 | 0.21 ± 0.07 | C | C | D1E1 | VW | ||||

|

Syrnolopsis lacustris N = 9 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 5510.110 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 842.0682 |

Soft |

Stanleya neritinoides N = 4 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 26,627.28 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 5043.367 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 127 |

4.82 ± 0.29 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | A | A | A1 | G1H1I1 |

CT Cusp N = 59 |

9.32 ± 1.09 | 0.51 ± 0.18 | A | A | A | A | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 132 |

4.64 ± 0.26 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | B | B | F1G1H1 | L1 |

LT Cusp N = 55 |

6.96 ± 0.55 | 0.29 ± 0.12 | B | B | J | I | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 273 |

4.41 ± 0.21 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | C | C | N1 | M1 |

MT Cusp N = 106 |

4.83 ± 0.53 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | C | C | A1B1 | D1E1F1 | ||||

|

Tiphobia horei N = 2 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 298.3816 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 695.6014 |

Soft |

Tanganyicia rufofilosa N = 7 specimens |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 24,804.23 |

p < 0.0001 F-ratio: 2 df: 420.1531 |

Solid | ||||||||||

|

CT Cusp N = 45 |

4.97 ± 0.65 | 0.26 ± 0.08 | A | A | Z | KLMN |

CT Cusp N = 121 |

7.27 ± 0.80 | 0.24 ± 0.14 | A | A | I | R | ||||

|

LT Cusp N = 43 |

4.26 ± 0.42 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | C | B | Q1 | H1I1J1K1 |

LT Cusp N = 101 |

5.40 ± 0.29 | 0.21 ± 0.07 | B | B | W | VWX | ||||

|

MT Cusp N = 78 |

4.78 ± 0.86 | 0.16 ± 0.08 | B | C | A1B1C1D1E1 | K1L1 |

MT Cusp N = 242 |

4.61 ± 0.60 | 0.19 ± 0.08 | C | C | H1J1 | D1E1 | ||||

Connecting letters from Tukey–Kramer test (which are usually plotted above the boxplots in Fig. 10) are listed under (A) and (B) identifying homogenous groups for (A) comparing the tooth types [CT, LT, and MT] within a single species and (B) comparing all species and structures

CT central tooth, LT lateral tooth, MT marginal tooth

Fig. 10.

Results of nanoindentation. Hardness (GPa) and Young’s modulus (GPa) for all cusps (central, lateral, marginal, with N = quantity of measured cusps) for each species (N = quantity of measured specimens) correlated with the preferred feeding substrate (circle = mud, hexagon = sand, square = plants, triangle = rock). Connecting letters from Tukey–Kramer test can be found in Table 1

Fig. 11.

Results of nanoindentation. Median of Young’s modulus (GPa) of the central, lateral, and marginal tooth cusps for each species correlated with the preferred feeding substrate (circle = mud, hexagon = sand, square = plants, triangle = rock) against the background of a phylogenetic tree (Bayesian). Taxa without molecular information were allocated to groups based on morphological analyses from relevant literature. Reconstructed ancestral feeding substrate of the lower taxonomic levels is plotted next to the nodes

When comparing E and H of each tooth type between all species significant differences were detected (p < 0.0001, F-ratio: 71, df: 20,217.82 for E, df: 2734.555 for H; see Figs. 10, 11; see Table 1, columns B for connecting letters from Tukey–Kramer test).

Two-way ANOVA (see Additional file 1) revealed that feeding substrate and tooth type both have same significant effect on E and H values (p < 0.0001 for each, see Additional file 1: Tables S2 and S3 for df, F-ratio, interaction terms). Least square mean plots (Additional file 1: Figure S1) reveal that E and H values of the central teeth are more influenced by the feeding substrate that the lateral teeth, and finally marginal teeth.

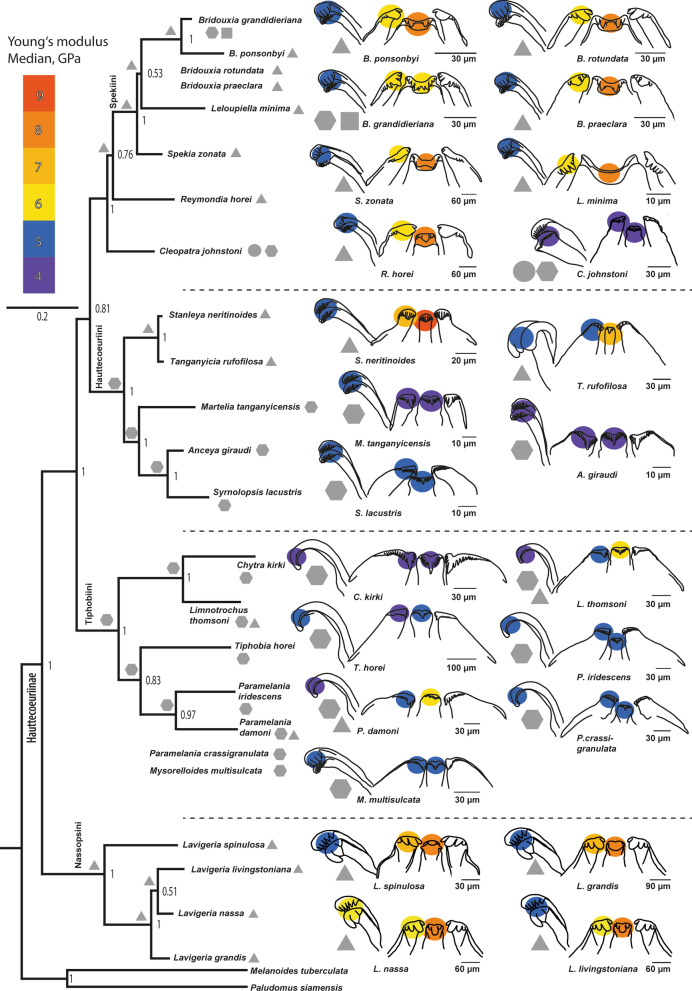

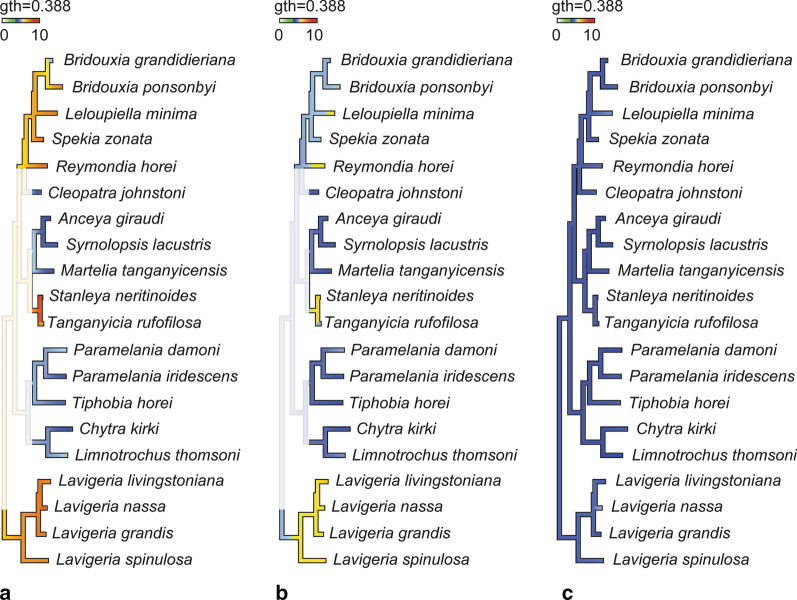

Reconstruction of the ancestral feeding substrate (Fig. 11) suggests a solid substrate for the Spekiini and Reymondia accompanied by central teeth of 7–8 GPa Young’s modulus and lateral teeth of 6 GPa, which convergently increased stiffness to 8 GPa in Leloupiella and Reymondia (Fig. 12). Within the Spekiini Bridouxia grandidieriana adapted to feeding on mixed substrate by reducing the Young’s modulus in the central teeth to 6 GPa (Fig. 12). A soft ancestral feeding substrate was computed for the Hauttecoeuriini (Fig. 11), here accompanied by a subsequent shift to solid substrate in the group containing Stanleya and Tanganyicia with an increasing Young’s modulus in both central and lateral teeth, and for the Tiphobiini, followed by a parallel adaptation to mixed feeding substrate in Paramelania damoni and Limnotrochus thomsoni in connection with an increase of the Young’s modulus from 5 to 6 GPa in the central teeth (Fig. 12). For the Nassopsini a solid feeding substrate was reconstructed (Fig. 11), here the Young’s modulus of all tooth types remains similar. For the marginal teeth no changes in the Young’s modulus were detected since all analysed species have similar mechanical properties in this tooth type (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Changes of Young’s modulus over the phylogeny (excl. outgroups) visualized using continuous character mapping (from 5 GPa [blue] to 10 GPa [red]) for a central tooth, b lateral tooth, c marginal tooth for the lower taxonomic levels

Discussion

The gastropods in Lake Tanganyika have limited options regarding their habitat, as they occur below the surf zone down to 200 m, with the deeper parts of the lake containing little oxygen and are toxic [44]. Sharing habitats might result in considerable inter- and intraspecific competition, but we found strong evidences for the avoidance or the reduction of resource competition by clear substrate-specificity in most paludomid groups [see also 44]. In Group 1, Spekiini Ancey, 1906 [58], Reymondia Bourguignat, 1885 [45] and riverine Cleopatrini Pilsbry and Bequaert, 1927 [60], Group 2, Hauttecoeuriini Bourguignat, 1885 [45], Syrnolopsini, Bourguignat, 1890 [47], and Group 3, Tiphobiini Bourguignat, 1886 [46], (groups in accordance with [42, 44]) some species feed on biofilm that covers stones (solid substrate), some select algae from sandy and muddy surfaces (soft substrate) and few (mixed) feed either on both (Paramelania damoni, Limnotrochus thomsoni) or on algae attached to plants and covering sand (Bridouxia grandidieriana). Group 4, containing Lavigeria and riverine Potadomoides, consist probably of species that exclusively feed on solid substrate. Unfortunately, reliable data on preferred substrate is not available for Potadomoides which has not been found again in the last decades. Its localities, the Malagarasi River and the Congo River drainage, are characterized by swampy areas as well as rapids with rocks. But, since its radular tooth characters are similar to Lavigeria species [43], we rather conclude that Potadomoides also feeds on algae from solid substrates.

The mechanical properties (E, H) of the paludomid radular teeth correlate with the preferred substrate and reflect different eco-morphotypes (Fig. 11). All species foraging on stones, viz. Bridouxia ponsonbyi, B. rotundata, B. praeclara, Leloupiella minima, Spekia zonata, Reymondia horei, Stanleya neritinoides, Tanganyicia rufofilosa, Lavigeria spinulosa, L. livingstoniana, L. nassa, and L. grandis, show gradual and distinct differences in their stiffness and hardness between the tooth types, which can be explained by different functional loads (Figs. 10, 11). The material properties certainly influence the mechanics of structures, the Young’s modulus E is, for example, directly linked with the ability of a structure to transfer forces [e.g. 131, 132, 133, 134] and correlates with the structures mechanical behaviour while puncturing and in direct turn the resistance of structures to failure [e.g. 135, 136]. We anticipate here that the stiff central and lateral teeth are rather used for scratching across the solid feeding substrate removing food items attached to it [see also 121, 129]; this function of the CT was also documented for Dendronotus [see 119], transferring higher force from the radular muscles via the tooth cusps onto the ingesta. The softer and more flexible marginal teeth have a smaller ability to transfer forces necessary to loosen a tightly attached biofilm. But their elasticity allows the reduction of the stress concentration, for example in case of hitting the substrate asperities. Their mechanical properties enable them to catapult back to place, possibly without fractures or ruptures, after hitting an obstacle. We would hence deduce that the marginal teeth are rather functionally different from the central and lateral teeth, possibly harvesting, like a broom, food items or particles that had been loosened from the substrate by grinding action of the central and lateral teeth [see also 108, 121, 129, 137]. This type of radula is considered to be a multifunctional tool.

For all species foraging on sand or mud, viz. Cleopatra johnstoni, Martelia tanganyicensis, Anceya giraudi, Syrnolopsis lacustris, Chytra kirki, Tiphobia horei, Paramelania iridescens, P. crassigranulata, and Mysorelloides multisulcata, we found similar mechanical properties in all tooth types as well as comparably soft and flexible tooth cusps (Figs. 10, 11). Their hardness and elasticity values are comparable to the mechanical properties of the solid substrate feeders’ marginal teeth. We would hence propose that these species rather possess a monofunctional radula with each tooth serving as broom collecting algae from the surface. The mechanical properties of the mixed substrate feeders, viz. Bridouxia grandidieriana, Limnotrochus thomsoni, and Paramelania damoni, are intermediate, as they have slightly softer and more flexible central and lateral tooth cusps compared to the gastropods loosening algae from stones but stiffer and harder ones than the species selecting biofilm from sand (Figs. 10, 11). Even though the gradients between the tooth cusps are not as distinct as in the gastropods foraging on stone, the existence of the gradual differences leads to the conclusion that, despite of softer and more flexible tooth cusps, the mixed substrate feeders also possess a multifunctional radula. Central and lateral teeth are rather used for loosening food items, whereas the softer marginal tooth cusps, showing similar properties to the marginal teeth of solid feeders and to each tooth type of species selecting algae from sand, serve as brooms.

Past studies on Sacoglossa revealed that tooth morphologies between closer related taxa differ because of specialisation to distinct ingesta [113–116] whereas for Dendronotus (Nudibranchia) it was reported that morphology relates to both phylogeny and ecology [119]. For paludomids we found that tooth’s morphologies correlate with the preferred feeding substrate. In most solid substrate feeders central teeth displaying either a prominent denticle (Nassopsini and Reymondia; Figs. 4, 8), or few or no denticles (Bridouxia ponsonbyi, B. rotundata, B. praeclara, Spekia, and Leloupiella; Figs. 3, 4), as well as laterals bearing a prominent denticle (Nassopsini, Reymondia, Bridouxia; Figs. 3, 4, 8), allow a large interaction surface between tooth cusps and ingesta directly transferring force. Additionally, these teeth are rather short and broad, probably leading to the reduction of deformation when tensile and compressive stresses appear in the structure during this action. However, some solid feeders (Stanleya and Tanganyicia; Fig. 5) as well as the mixed substrate feeders (Paramelania damoni, Limnotrochus thomsoni, Bridouxia grandidieriana; Figs. 3, 6, 7) display an alternative morphology, rather similar to teeth of gastropods foraging on sand. Soft substrate feeders possessing central, lateral, and marginal teeth with small or finger-like denticles at each cusp (Figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7), which probably enables them to rake between the grains gathering the food particles. We hypothesize that radular tooth performance in Stanleya, Tanganyicia, and all mixed substrate feeders is ensured by mechanical properties rather than morphology. Thus, pure morphology does not consistently reflect adaptations, but the morphology furnished by mechanical properties allows the establishment of tooth eco-morphotypes.

Adaptations to distinct substrates, solid as well as soft and mixed, are present in most taxonomic paludomid lineages (Fig. 11). This in turn leads to the hypothesis that one main engine of their evolution is trophic specialization to feeding substrates, establishing distinct ecological niches and allowing the coexistence of taxa [see also 119 for diet-driven radiation in Dendronotus]. Only Group 4 (Nassopsini Kesteven, 1903 [138], contains Lavigeria) is exceptional because it contains exclusively solid substrate feeders (Fig. 11). Lavigeria is a paludomid group containing a plethora of named species [see e.g. 79, 139] that had been treated as result of an exclusively intralacustrine adaptive radiation. Unfortunately, a systematic revision identifying evolutionary entities is still lacking, hindering hypotheses on their evolution. However, when comparing Lavigeria adult shells their distinct sizes are apparent which are interpreted as result of annidation through different body sizes [unpublished data]. Also, Lavigeria radular teeth are of distinct tooth sizes. Lavigeria grandis displaying the largest teeth, followed by L. nassa, L. spinulosa, and finally L. livingstoniana possessing the smallest teeth (Figs. 7, 8). This could be an indication that Lavigeria species avoid competition by trophic specialization, albeit not to different feeding substrates, but rather to different algae or biofilm types growing on solid substrates. However, in order to determine whether species have distinct food preferences, it would be necessary to collect and gather feeding substrates and biofilms directly in situ. The only available collectors’ comments on Lake Tanganyikan biofilms, however, suggest that paludomids feed on soft algae, overcasting either rocks or plant structures or covering sandy or muddy substrates. This could explain the relatively soft and elastic tooth cusp of these gastropods in comparison with published hardness and elasticity measurements on teeth of hard calcified algae feeders, such as e.g. Polyplacophora and Patellogastropoda (with E ranging from 16 GPa over 90–125 GPa up to 52–140 GPa [140–144] and H ranging from 9–12 GPa [140, 142, 144]).

Molecular clock approaches [42, 122] support an ancient origin of diversity and disparity, long before the formation of Lake Tanganyika or a proto-lake. After the rifting of the African continent and the formation of the lake several independent colonialization events of already distinct riverine paludomid lineages succeeded from the surrounding river systems. We here reconstructed ancestral feeding substrates and ancestral E values for the distinct tooth types [for ancestral state reconstruction and diet preference evolution in Nudibranchia see also 145]. However, this reconstruction is only reliable for the lower taxonomic groups (at the level of Hauttecoeuriini, Tiphobiini, Nassopsini, or the Group containing the Spekiini and Reymondia), but not on the level of the Hauttecoeuriinae. Due to the fact that we have tested only 24 species of the flock by nanoindentation, which is a highly laborious experimental set-up, we lack reliable information for many species (e.g. Bathanalia, many Lavigeria species). However, by including more paludomid taxa in our molecular tree and adding feeding substrate information we found evidence that the ancestral riverine feeding substrate of the Hauttecoeuriinae is of soft nature [122] which could have been accompanied by long and slender teeth with numerous denticles of equal size (monomorphic radula) and indicative of an preadaptation sensu strictu [146] to the riverine substrate. This was possibly succeeded by the convergent shift to solid substrate in two paludomid lineages (ancestor of (i) Spekiini and Reymondia as well as (ii) Nassopsini) evolving central and lateral tooth morphologies adapted to this substrate furnished by the evolution of harder and stiffer central and lateral tooth cusps. Since we unfortunately lack biomaterial property information as well as reliable feeding substrate information for Potadomoides, the riverine sister group of the Nassopsini [43], we do not know if (a) the ancestor of the Nassopsini or (b) the ancestor of the group containing the Nassopsini and Potadomoides has adapted to solid substrate. If Potadomoides species fed also on solid substrate it would be possible that a shift from soft to solid feeding substrate has taken place in riverine rapids. Additionally, possibly after the origin and the colonialization of Lake Tanganyika, the ancestor of Stanleya and Tanganyicia has adapted to solid substrate. Nevertheless, Stanleya, and Tanganyicia display (Fig. 5), as described above, rather monomorphic radular teeth similar to the soft substrate feeders. These taxa probably still carry their ancestral riverine morphological characters. Thus, their adaptation to solid substrate involved only the change in material properties hardness and elasticity.

Bridouxia is probably a case of an exclusively intralacustrine adaptive radiation, strongly indicated by molecular clock approaches [122]. Here we were able to detect secondary adaptation to mixed feeding substrate for B. grandidieriana. This taxon became probably adapted through changes in morphology as well as material properties, evolving softer and more flexible central and lateral teeth with small denticles serving as a broom (Fig. 3). The mixed substrate feeders Paramelania damoni and Limnotrochus thomsoni retained their ancestral tooth morphologies (Figs. 6, 7), but temporary solid substrate feeding is probably enabled by the evolution of stiffer and harder central and lateral tooth cusps. All other lacustrine species (Martelia, Anceya, Syrnolopsis, Chytra, Tiphobia, P. iridescens, P. crassigranulata, Mysorelloides) are adapted to foraging on soft substrates carrying their ancestral riverine tooth morphologies [122] as well as displaying soft and flexible teeth (Figs. 10, 11).

In summary, tooth shapes and tooth mechanical properties differ more than expected in sister taxa (e.g. Bridouxia, Lavigeria [here through tooth size], or between all sister groups as e.g. Tiphobiini and Hauttecoeuriini). Additionally, parallel evolution of tooth shapes and mechanical properties can be detected (Reymondia and Nassopsini). This suggests that radular teeth in paludomids are under strong selection and that diverging from close relatives has often been favoured resulting in the micro partitioning of the environment; this is similar to ingesta-processing structures (beaks, skull bones) found in other radiations with trophic specialisation being one main driving force (e.g. Darwin finches, cichlid fish).

Conclusion

Here we present the first comparative study on the mechanical properties, hardness and elasticity, of taenioglossan radular teeth from African paludomid gastropods from Lake Tanganyika and surrounding river systems, based on a large sample size and in a phylogenetic and ecological context. The tested paludomid teeth correlate with their preferred feeding substrate and reflect different tooth eco-morphotypes accompanying morphology. Our identification of adaptations allows to put forward a new perspective on the evolution of this species flock. We postulate that trophic specialisation resulting in niche partitioning has played a major role in the evolution and radiation of this flock.

Methods

As basis we used paludomid gastropods (Fig. 1) collected in earlier studies [see 44], supplemented by additional material of taxa collected by Heinz Büscher, Basel. Specimens stored in ethanol are inventoried at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin (ZMB), the Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale, Tervuren, Belgium (MRAC), the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels, Belgium (IRSNB), and the Zoological Museum (ZMH) of the Center of Natural History (CeNak) in Hamburg (for details on sampling locality see Additional file 1: Table S1). Specimens were identified based on shell morphology in comparison with type material following essentially [44] and literature referred to therein.

For nanoindentation [detailed descripting of method in 129, 130] overall 124 radulae belonging to 24 species (Additional file 1: Table S1), accompanied by data on 7 specimens from Spekia zonata taken from [129], were manually extracted from adult specimens, freed from surrounding tissues, dried and, laying on its side, tapped with double-sided adhesive tape to a glass object slide. The tape ensured that the radulae were accurately arranged, with marginal teeth at the bottom, followed by lateral, central, lateral, and on the top marginal teeth. This procedure ensured that after polishing only one tooth type was superficial at the plain surface. Each radula was surrounded by a small metallic ring resulting an almost parallel sample after polishing necessary for an almost error-free nanoindentation. Rings were filled with epoxy resin (RECKLI®EPOXIWST, Young’s modulus of the epoxy is 1 GPa), known to not infiltrate the teeth, polymerizing at room temperature. Object slide and tape were removed, radulae were polished with gradual diamond pastes (Buehler MetaDi Ultra Paste 6 µm 3 µm, 1 µm) and smoothened with a polishing machine (Buehler MataServ 250 with Struers OP-U, 0.04 µm suspension with 250 rpm) for a plain surface displaying the longitudinal section of teeth (Fig. 2c–f). After performing nanoindentation, employing a Nanoindenter SA2 (MTS Nano Instrument, Oak Ridge, TN, USA; CSM) equipped with Berkovich indenter tip, on the superficial tooth row (marginals) samples were again smoothened until the next tooth row (laterals) was on display (Fig. 2b). Steps were repeated until all teeth were measured. The indents for this study were made at the tooth cusps with each indentation curve controlled manually for correct surface finding. In each specimen, about 25 tooth rows of the outer wear zone were tested, resulting in more than 9027 measured tooth cusps for all analysed specimens. We focussed on this specific radular locality to exclude not matured teeth from this study. For detailed quantity [N] of specimens per species, evaluable indentation data on hardness/elasticity per species and per tooth type see Table 1 and Fig. 10 (N of analysed specimens differs between species due to availability of radular material; not every nanoindentation curve and resulting data was evaluated due to artefacts, e.g. surface finding problems, local surface roughness, the angle between the embedded tooth and the epoxy surface; thus N of analysed tooth cusps differs between specimens). Reliable nanoindentation curves and resultant data tables on Young’s modulus (Elasticity modulus; E) and hardness (H) of materials were exported; values of E and H were either determined at penetration depths of 480–520 nm (for larger teeth, in Spekia, Reymondia, Lavigeria, Chytra) or at penetration depth 450–500 nm (for smaller teeth, in Bridouxia, Leloupiella, Cleopatra, Stanleya, Tanganyicia, Martelia, Anceya, Syrnolopsis, Limnotrochus, Paramelania, Mysorelloides) with about 30 values per indentation. These indentation depths were targeted, because at low depths E and H strongly fluctuated due to surface roughness both (Fig. 2g), and at higher depths the side effects of the epoxy could not be excluded. All statistical analyses were performed with JMP® Pro, Version 14 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2007), calculating mean values and standard deviations summarizing the data of all measured cusps per tooth type of all analysed specimens. This was done for each species. Shapiro–Wilk-W-test for testing of normality and one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey–Kramer test for detecting homogeneous groups with connecting letters report were carried out afterwards. Mechanical properties were compared between the preferred feeding substrates (i), all central, lateral, and marginal tooth cusps (ii), within each species (iii), between the species (iv). Additionally, a two-way ANOVA for determining the influence of the feeding substrate, the tooth type and the interaction of both parameters was carried out.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM) one radula per species (Additional file 1: Table S1) was extracted, digested with proteinase K according to the protocol of [147], cleaned for a few seconds in an ultrasonic bath, mounted on an aluminium stub, coated with carbon and visualized either with a SEM Zeiss LEO 1525 (One Zeiss Drive, Thornwood, NY) or a Tabletop SEM TM4000Plus (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) (see Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 for SEM images).

To establish a hypothesis on the evolutionary history of the African paludomids in the context of trophic specialisation based on biomechanical properties, we used all available DNA sequences of tested species, here sequences of the mitochondrial 16S rRNA (16S) and the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene from previous studies [42, 85] (see Additional file 1: Table S1); additionally, Melanoides tuberculata and Paludomus siamensis sequences were used as outgroup. Sequences were aligned with MAFFT 7 [148] employing the Q-INS-I algorithm, the 1PAM/κ = 2 option for the scoring matrix for nucleotide sequences and otherwise default settings. Bayesian inference with MrBayes 3.2.6 [149] was used to reconstruct phylogenetic relationship. PartitionFinder 2.1.1 [150] was used to select best-fitting models and a suitable partitioning strategy for the Bayesian inference based on the Bayesian information criterion. The DNA sequences were initially divided into four partitions: the first, second and third codon positions of COI and 16S. An exhaustive search with PartitionFinder was conducted allowing for separate estimation of branch lengths for each partition. The models were limited to those available in MrBayes. Metropolis coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo (MC3) searches were run with four chains in two separate runs for 50,000,000 generations with default priors, trees sampled every 1000 generations and separate estimation of parameters for individual partitions under default heating using best-fit models as suggested by PartitionFinder (first plus second codon positions of COI: GTR + I + G; third codon positions of COI: HKY + G; 16S: GTR + I + G). Diagnostic tools provided in MrBayes were used to ensure that the MC3 searches had reached stationarity and convergence. The first 5,000,000 generations of each run were discarded as burn-in.

Changes of Young’s modulus over the phylogeny (excl. outgroups) for the three different tooth types were visualized using continuous character mapping. Ancestral states [see also 145] for internal nodes were estimated using a maximum likelihood approach along with interpolating the states along the branches of the tree following an idea from [151] as implemented in phytools [152, 153]. To trace the adaptation to different feeding substrates (soft, solid, mixed) in a maximum likelihood setting, we used ape [154] assuming the one-parameter equal rates model to specify the transition probabilities between the states of the discrete character.

For some species, Bridouxia praeclara, B. rotundata, Paramelania crassigranulata, Mysorelloides multisulcata, no molecular information could be obtained from various previous approaches. These taxa were placed tentatively in the resulting phylogeny as suggested by [44, 155] who compared internal and external morphological characters and identified synapomorphies. This resulted here in a systematization [see 156 for further details of this term].

The information on the preferred feeding substrate is based on the relevant literature [44, 79, 120, 139] supplemented by notes from the collectors of individual samples in the field (Heinz Büscher, Matthias Glaubrecht).

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. List of specimens, collection numbers, localities, and preparation techniques; Fig. S1 und Tables S2, S3 Results of 2-way ANOVA for E and H.

Acknowledgements

We like to thank Peter Stutz from the Mineralogical-Petrographic Institute of the University of Hamburg for the great support in the sample preparation. Heinz Büscher (Basel) collected part of the specimens at Lake Tanganyika. Renate Walter (Zoological Institute of Universität Hamburg) helped with SEM of the radulae. Thomas M. Kaiser (CeNak) helped with the discussion of results. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Abbreviations

- 16S

Mitochondrial 16S rRNA

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- COI

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene

- E

Young's modulus

- H

Hardness

- IRSNB

Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Bruxelles, Belgium

- MRAC

Musée royal de l'Afrique centrale, Tervuren, Belgium

- N

Quantity

- SEM

Scanning Electron Microscope

- ZMB

Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Germany

- ZMH

Zoologisches Museum Hamburg (Center of Natural History CeNak), Germany

Authors’ contributions

WK wrote the manuscript, drew the figures, performed nanoindentation, summarized and analysed the data. MTN performed the molecular analyses, computed the continuous character mapping and the ancestral states reconstructions. AK supported the experiments and discussed data. SNG discussed the manuscript and the figures; his expertise was critical for understanding the results and the functional morphology. MG, in addition to writing parts of the manuscript, planed the study, and discussed the data. All authors contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Many of the here studied gastropods were collected by MG during an earlier research project funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG GL 297/5-1). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12862-021-01754-4.

References

- 1.Terborgh JW. Toward a trophic theory of species diversity. PNAS. 2015;112(37):11415–11422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501070112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pocheville A. The ecological niche: history and recent controversies. In: Heams T, Huneman P, Lecointre G, Silberstein M, editors. Handbook of evolutionary thinking in the sciences. Dordrecht: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendry AP. Eco-evolutionary dynamics. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lack D. Darwin’s Finches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant PR. Ecology and evolution of Darwin’s Finches. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant PR, Weiner J. Ecology and evolution of Darwin's Finches. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant PR, Grant BR. How and why species multiply. The radiation of Darwin’s Finches. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant PR, Grant BR. 40 years of evolution: Darwin's Finches on Daphne Major Island. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrington HL, Lawson LP, Clark CM, Petren K. The evolutionary history of Darwin's Finches: speciation, geneflow, and introgression in a fragmented landscape. Evolution. 2014;68(10):2932–2944. doi: 10.1111/evo.12484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barlow GW. The Cichlid fishes: nature’s grand experiment in evolution. Cambridge: Perseus Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seehausen O. African cichlid fish: a model system in adaptive radiation research. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2006;273(1597):1987–1998. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3539). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malinsky M, Salzburger W. Environmental context for understanding the iconic adaptive radiation of cichlid fishes in Lake Malawi. PNAS. 2016;113(42):11654–11656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614272113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ronco F, Büscher HH, Indermaur A, Salzburger W. The taxonomic diversity of the cichlid fish fauna of ancient Lake Tanganyika. East Afr J Great Lakes Res. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jglr.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmer KR, Kusche H, Lehtonen TK, Meyer A. Local variation and parallel evolution: morphological and genetic diversity across a species complex of Neotropical crater lake cichlid fishes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 2010;365:1769–1782. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elmer K, Fan S, Kusche H, et al. Parallel evolution of Nicaraguan crater lake cichlid fishes via non-parallel routes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5168. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaither MR, Greaves S, Amirthalingam P. The physiology of rapid ecological specialization: a look at the Midas cichlids. Mol Ecol. 2020;29(7):1215–1218. doi: 10.1111/mec.15408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffe AL, Campbell-Staton SC, Losos JB. Geographical variation in morphology and its environmental correlates in a widespread North American lizard, Anolis carolinensis (Squamata: Dactyloidae) Biol J Linn Soc. 2016;117(4):760–774. doi: 10.1111/bij.12711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stroud JT, Losos JB. Bridging the process-pattern divide to understand the origins and early stages of adaptive radiation: a review of approaches with insights from studies of Anolis lizards. J Hered. 2020;111(1):33–42. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esz055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velasco JA, Villalobos F, Diniz-Filho JA, Poe S, Flores-Villela O. Macroecology and macroevolution of body size in Anolis lizards. Ecography. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ecog.04583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenwood PH. The cichlid fishes of Lake Victoria, east Africa: the biology and evolution of a species flock. Bull Br Mus Nat Hist Zool. 1974;6:1–134. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schluter D. Ecological causes of adaptive radiation. Am Nat. 1996;148:40–63. doi: 10.1086/285901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schluter D. The ecology of adaptive radiation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schluter D. Ecological character displacement in adaptive radiation. Am Nat. 2000;156:4–16. doi: 10.1086/303412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schluter D. Evidence for ecological speciation and its alternative. Science. 2009;323(5915):737–741. doi: 10.1126/science.1160006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glor RE. Phylogenetic insights on adaptive radiation. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2010;41:251–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Losos JB, Mahler DL. Adaptive radiation: the interaction of ecological opportunity, adaptation, and speciation. In: Bell M, Futuyma D, Eanes W, Levinton J, editors. Evolution since Darwin: the first 150 years. Sunderland: Sinauer; 2010. pp. 381–420. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapman AD. Numbers of living species in Australia and the world. 2. Toowoomba: Australian Biodiversity Information Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mora C, Tittensor DP, Adl S, Simpson AGB, Worm B. How many species are there on earth and in the ocean? PLoS Biol. 2011;9(8):e1001127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullen SP, Mendelson TC, Schal C, Shaw KL. Rapid evolution of cuticular hydrocarbons in a species radiation of acoustically diverse Hawaiian crickets (Gryllidae: Trigonidiinae: Laupala) Evolution. 2007;61:223–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knope ML, Bellinger MR, Datlof EM, Gallaher TJ, Johnson MA. Insights into the evolutionary history of the Hawaiian Bidens (Asteraceae) adaptive radiation revealed through phylogenomics. J Hered. 2020;111(1):119–137. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esz066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glaubrecht M. On, “Darwinian Mysteries” or molluscs as models in evolutionary biology: from local speciation to global radiation. Am Malacol Bull. 2009;27:3–23. doi: 10.4003/006.027.0202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glaubrecht M. Toward solving Darwin’s “mystery”: speciation and radiation in freshwater gastropods. Am Malacol Bull. 2011;29(1/2):187–216. doi: 10.4003/006.029.0211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rintelen TV, Wilson AB, Meyer A, Glaubrecht M. Escalation and trophic specialization drive adaptive radiation of freshwater gastropods in ancient lakes on Sulawesi, Indonesia. Proc R Soc Lond. 2004;271(1557):2541–2549. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rintelen TV, Bouchet P, Glaubrecht M. Ancient lakes as hotspots of diversity: a morphological review of an endemic species flock of Tylomelania (Gastropoda: Cerithioidea: Pachychilidae) in the Malili lake system on Sulawesi, Indonesia. Hydrobiologia. 2007;592(1):11–94. doi: 10.1007/s10750-007-0765-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rintelen TV, Rintelen KV, Glaubrecht M. The species flocks of the viviparous freshwater gastropod Tylomelania (Mollusca: Cerithioidea: Pachychilidae) in the ancient lakes of Sulawesi, Indonesia: the role of geography, trophic morphology and color as driving forces in adaptive radiation. In: Glaubrecht M, editor. Evolution in action. Case studies in adaptive radiation, speciation and the origin of biodiversity. Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. pp. 485–512. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rintelen TV, Glaubrecht M. Anatomy of adaptive radiation: a unique reproductive strategy in the endemic freshwater gastropod Tylomelania (Cerithiodea: Pachychilidae) on Sulawesi, Indonesia and its biogeographical implications. Biol J Linn Soc. 2005;85(4):513–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00515.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glaubrecht M, Rintelen TV. The species flocks of lacustrine gastropods: Tylomelania on Sulawesi as models in speciation and adaptive radiation. In: Proceedings of the “Speciation in Ancient Lake IV” Symposium, Berlin. Hydrobiologia. 2008;615:181–99.

- 38.Hilgers L, Hartmann S, Pfaender J, Lentge-Maaß N, Rintelen TV, Hofreiter M. Radula diversification promotes ecomorph divergence in an adaptive radiation of freshwater snails. bioRxiv. 2020.01.17.910034. 10.1101/2020.01.17.910034.

- 39.Köhler F, Glaubrecht M. Uncovering an overlooked radiation: morphological and mitochondrial DNA differentiation in endemic freshwater snails on Madagascar (Caenogastropoda: Pachychilidae) and their biogeography. Biol J Linn Soc. 2010;99(4):867–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01390.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glaubrecht M, Köhler F. Radiating in a river: systematics, molecular genetics and morphological differentiation of viviparous freshwater gastropods endemic to the Kaek River, central Thailand. Biol J Linn Soc. 2004;82(3):275–311. doi: 10.1111/j.10958312.2004.00361.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Köhler F, Panha S, Glaubrecht M. Speciation and radiation in a river: assessing the morphological and genetic differentiation in a species flock of viviparous gastropods (Cerithioidea: Pachychilidae) In: Glaubrecht M, editor. Evolution in action. Case studies in adaptive radiation, speciation and the origin of biodiversity. Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson AB, Glaubrecht M, Meyer A. Ancient lakes as evolutionary reservoirs: evidence from the thalassoid gastropods of Lake Tanganyika. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2004;271(1538):529–536. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glaubrecht M, Strong EE. Ancestry to an endemic radiation in Lake Tanganyika? Evolution of the viviparous gastropod Potadomoides Leloup, 1953 in the Congo River system (Cerithioidea, Paludomidae) Biol J Linn Soc. 2007;92(2):367–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00867.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glaubrecht M. Adaptive radiation of thalassoid gastropods in Lake Tanganyika, East Africa: morphology and systematization of a paludomid species flock in an ancient lake. Zoosyst Evol. 2008;84:71–122. doi: 10.1002/zoos.200700016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bourguignat MJR. Notice prodromique sur les mollusques terrestres et fluviatiles. Paris: Savy; 1885. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bourguignat MJR. Nouveautés Malacologiques: Unionidæ et Iridinidæ du Lac Tanganika. Paris: Savy; 1886. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bourguignat MJR. Histoire Malacologique du Lac Tanganika (Afrique Equatoriale) Ann Sci Nat Zool Biol Anim. 1890;10:1–267. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pelseneer P. Mollusques recueillis par M. Le Capitaine Storms dans la region du Tanganyika. Bull Mus R Hist Nat Belg. 1886;4:103–115. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore JES. The molluscs of the Great African Lakes. I. Distribution. Q J Microsc Sci. 1898;41:159–180. doi: 10.5962/bhl.part.1223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moore JES. The molluscs of the Great African Lakes. II. The anatomy of the Typhobias, with a description of the new genus (Bathanalia) Q J Microsc Sci. 1898;41:181–204. doi: 10.5962/bhl.part.1223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore JES. The molluscs of the Great African Lakes. III. Tanganyikia rufofilosa, and the genus Spekia. Q J Microsc Sci. 1899;42:155–185. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore JES. The molluscs of the Great African Lakes. IV. Nassopsis and Bythoceras. Q J Microsc Sci. 1899;42:187–201. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith EA. Diagnoses of new shells from Lake Tanganyika and East Africa. Ann Mag Nat Hist. 1880;6:425–430. doi: 10.1080/00222938009458973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith EA. On the shells of Lake Tanganyika and of the neighbourhood of Ujiji, Central Africa. Proc Zool Soc Lond. 1880;1880:344–352. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith EA. Descriptions of two new species of shells from Lake Tanganyika. Proc Zool Soc Lond. 1881;49(3):558–561. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith EA. Diagnosis of new shells from Lake Tanganyika. Ann Mag Nat Hist. 1889;6:173–175. doi: 10.1080/00222938909460494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith EA. Some remarks on the Mollusca of Lake Tanganyika. Proc Malacol. 1904;6(2):77–104. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ancey C-F. Reflexions sur la fauna malacologique du Lac Tanganika et cataloque des mollusques de ce lac. Bull Biol Fr Bel. 1906;5(9):229–270. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Germain L. Mollusques du Lac Tanganyika et de ses environs. Extrait des resultats secientifiques des voyages en Afrique d’Edouard Foa. Bull Mus Natl Hist Nat. 1908;14:1–612. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pilsbry HA, Bequaert J. The aquatic mollusks of the Begian Congo. With a geographical and ecological account of Congo malacology. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist. 1927;53:69–602. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moore JES. On the zoological evidence for the connection of Lake Tanganyika with the sea. Proc R Soc. 1898;62:451–458. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moore JES. The fresh-water fauna of Lake Tanganyika. Nature. 1897;56:198–200. doi: 10.1038/056198c0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moore JES. The Tanganyika problem. London: Burst and Blackett; 1903. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hudleston WH. On the origin of the marine (halolimnic) fauna of Lake Tanganyika. Geol Mag Suppl. 1904;1:337–382. doi: 10.1017/S0016756800119831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cunnington WA. The fauna of the African Lakes: a study in comparative limnology with special reference to Tanganyika. Proc Zool Soc Lond. 1920;1920:507–622. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yonge CM. The prosobranchs of Lake Tanganyika. Nature. 1938;142:464–466. doi: 10.1038/142464a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwetz J, Dartevelle E. Sur l’origine des mollusques thalassoides du Lac Tanganika. Revue historique et analytique. Memoires de la Institut Royal Colonial Belge, Sciences Naturelles et Medicales 1948;16(7):1–58.

- 68.Hubendick B. On the evolution of the so-called thalassoid molluscs of Lake Tanganyika. Arkiv för Zoologi. 1952;3:319–323. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brooks JL. Speciation in ancient lakes. Q Rev Biol. 1950;25(30–60):131–176. doi: 10.1086/397539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mayr E. Animal, species, and evolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mayr E, Ashlock PD. Principles of systematic zoology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boss KJ. On the evolution of gastropods in ancient lakes. In: Fretter V, Peake J, editors. Pulmonates, vol. 2a. Systematics, evolution and ecology. London: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 385–428. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnston MR, Cohen AS. Morphological divergence in endemic gastropods from Lake Tanganyika: implications for models of species flock formation. Palaios. 1987;2:413–425. doi: 10.2307/3514613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brown DS, Mandahl-Barth G. Living molluscs of Lake Tanganyika: a revised and annotated list. J Conchol. 1987;32:305–327. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berthold T. Intralacustrine speciation and the evolution of shell sculpture in gastropods of ancient lakes—application of Günther’s niche concept. Abhandlungen des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins Hamburg (NF) 1990;31(32):85–118. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coulter GW. Lake Tanganyika and its life. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gorthner A. Bau, Funktion und Evolution komplexer Gastropodenschalen in Langzeit-Seen. Mit einem Beitrag zur Paläobiologie von Gyraulus “multiformis” im Steinheimer Becken. Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde Serie B. 1992;190:1–173. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Michel E, Cohen AS, West K, Johnston MR, Kat PW. Large African lakes as natural laboratories for evolution: examples from the endemic gastropod fauna of Lake Tanganyika. Mitteilungen der Internationalen Vereinigung für Limnologie. 1992;23:85–99. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brown D. Freshwater snails of Africa and their medical importance. London: Taylor and Francis; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Michel E. Why snails radiate: a review of gastropod evolution in long-lived lakes, both recent and fossil. In: Martens K, Goddeeris B, Coulter G, editors. Speciation in ancient lakes. Stuttgart: Advances in Limnology; 1994. pp. 285–317. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Michel E. Phylogeny of a gastropod species flock: exploring speciation in Lake Tanganyika in a molecular framework. In: Rossiter A, editor. Biology of ancient lakes. Advances in ecological research. London: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 275–302. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Michel E. Vinundu, a new genus of Gastropod (Cerithioidea: ‘Thiaridae) with two species from Lake Tanganyika, east Africa, and its molecular phylogenetic relationships. J Molluscan Stud. 2004;70:1–19. doi: 10.1093/mollus/70.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.West K, Cohen A. Shell microstructure of gastropods from Lake Tanganyika, Africa: adaptation, convergent evolution, and escalation. Evolution. 1996;50(2):672–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martens K. Speciation in ancient lakes. Trends Ecol Evol. 1997;12(5):177–182. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.West K, Michel E. The dynamics of endemic diversification; molecular phylogeny suggests an explosive origin of the thiarid gastropods of Lake Tanganyika. Adv Ecol Res. 2000;31:331–354. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2504(00)31018-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Van Damme D, Pickford M. The late Cenozoic Thiaridae (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Cerithioidea) of the Albertine Rift Valley (Uganda-Congo) and their bearing on the origin and evolution of the Tanganyikan thalassoid malacofauna. Hydrobiologia. 2003;498:1–83. doi: 10.1023/A:1026298512117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tiercelin JJ, Mondeguer A. The geology of the Tanganyika trough. In: Coulter GW, editor. Lake Tanganyika and its life. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 7–48. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cohen AS, Soreghan MJ, Scholz CA. Estimating the age of formation of lakes: an example from Lake Tanganyika. East Afr Rift Syst Geol. 1993;21:511–514. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(1993)021<0511:ETAOFO>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cohen AS, Talbot MR, Awramik SM, Dettman DL, Abell P. Lake level and paleoenvironmental history of Lake Tanganyika, African, as inferred from late Holocene and modern stromatolithes. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1997;109(4):444–460. doi: 10.1130/00167606(1997)109<0444:LLAPHO>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lezzar KE, Tiercelin JJ, Le Turdu C, Cohen AS, Reynolds DJ, Le Gall B, Scholz CA. Control of normal fault interaction on the distribution of major Neogene sedimentary depocenters, Lake Tanganyika. East Afr Rift AAPG Bull. 2002;86:1027–1059. doi: 10.1306/61EEDC1A-173E-11D7-8645000102C1865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Spiegel C, Kohn BP, Belton DX, Gleadow AJW. Morphotectonic evolution of the Central Kenya rift flanks: implications for late Cenozoic environmental change in East Africa. Geology. 2007;35:427–430. doi: 10.1130/G23108A.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bauer FU, Glasmacher UA, Ring U, Schumann A, Nagudi B. Thermal and exhumation history of the central Rwenzori Mountains, Western rift of the east African rift system, Uganda. Int J Earth Sci. 2010;99(7):1575–1597. doi: 10.1007/s00531-010-0549-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Roller S, Hornung J, Hinderer M, Ssemmanda I. Middle Miocene to Pleistocene sedimentary record of rift evolution in the southern Albert rift (Uganda) Int J Earth Sci. 2010;99:1643–1661. doi: 10.1007/s00531-010-0560-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Herrel A, Podos J, Huber SK, Hendry AP. Bite performance and morphology in a population of Darwin's finches: implications for the evolution of beak shape. Funct Ecol. 2005;19(1):43–48. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-8463.2005.00923.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Herrel A, Podos J, Huber SK, Hendry AP. Evolution of bite force in Darwin's finches: a key role for head width. J Evol Biol. 2005;18(3):669–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Soons J, Genbrugge A, Podos J, Adriaens D, Aerts P, Dirckx J, Herrel A. Is beak morphology in Darwin’s Finches tuned to loading demands? PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tokita M, Yano W, James HF, Abzhanov A. Cranial shape evolution in adaptive radiations of birds: comparative morphometrics of Darwin’s finches and Hawaiian honeycreepers. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2016;372(1713):20150481. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ma W, Brusatte SL, Lü J, Sakamoto M. The skull evolution of oviraptorosaurian dinosaurs: the role of niche partitioning in diversification. J Evol Biol. 2020;33(2):178–188. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pérez-Miranda F, Mejía O, González-Díaz AA, Martínez-Méndez N, Soto-Galera E, Zúñiga G, Říčan O. The role of head shape and trophic variation in the diversification of the genus Herichthys in sympatry and allopatry. J Fish Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jfb.14304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guralnick R, Smith K. Historical and biomechanical analysis of integration and dissociation in molluscan feeding, with special emphasis on the true limpets (Patellogastropoda: Gastropoda) J Morphol. 1999;241:175–195. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199908)241:2<175::AID-JMOR7>3.0.CO;2-0). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Solem A. Patterns of radular tooth structure in carnivorous land snails. Veliger. 1974;17:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Walsby JR. Feeding and the Radula in the Marine Pulmonate Limpet, Trimusculus reticulatus. Veliger. 1975;18:139–145. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Burch JB, Jeong KH. The Radula teeth of selected Planorbidae. Malacol Rev. 1984;17(1–2):67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hawkins SJ, Watson DC, Hill AS, Harding SP, Kyriakides MA, Hutchinson S, Norton TA. A comparison of feeding mechanisms in microphagous, herbivorous, intertidal, prosobranchs in relation to resource partitioning. J Molluscan Stud. 1989;55(2):151–165. doi: 10.1093/mollus/55.2.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]