Abstract

Background

The challenge of COVID-19 is very high globally due to a lack of proven treatment and the complexity of its transmission. The prevalence of in-hospital mortality among patients with COVID-19 was very high which ranged from 1 to 52% of hospital admission. The prevalence of mortality among intensive care patients with COVID-19 was very high which ranged from 6% to 86% of admitted patients.

Methods

A three-stage search strategy was conducted on PubMed/Medline; Science direct Cochrane Library. The Heterogeneity among the included studies was checked with forest plot, χ2 test, I2 test, and the p-values. Publication bias was checked with a funnel plot and the objective diagnostic test was conducted with Egger's correlation, Begg's regression tests.

Result

The Meta-Analysis revealed that the pooled prevalence of in-hospital mortality in patients with coronavirus disease was 15% (95% CI: 13 to 17). Prevalence of in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 was strongly related to different factors. Patients with Acute respiratory distress syndrome were eight times more likely to die as compared to those who didn't have, RR = 7.99(95% CI: 4.9 to 13).

Conclusion

The review revealed that more than fifteen percent of patients admitted to the hospital with coronavirus died. This presages the health care stakeholders to manage morbidity and mortality among patients with coronavirus through the mobilization of adequate resources and skilled health care providers.

Registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis was registered in research registry with UIN of reviewregistry1093.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Severe acute respiratory syndrome, Mortality

Highlights

-

•

The review revealed that more than fifteen percent of patients admitted to the hospital with coronavirus died.

-

•

The rate mortality among COVID-19 patients in the Intensive Care Unit was Twenty-nine percent.

-

•

The Meta-Analysis revealed that sepsis was the most prevalent complication.

-

•

Rate of mortality among COVID-19 was eight times more likely in patients with ARDS.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that cause Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mainly affects the respiratory, gastrointestinal, liver, and central nervous system of humans, livestock, Bats, mice, and other wild animal [[1], [2], [4], [3]]. The infection mainly affects the respiratory system and present with fever, dry cough, and difficulty of breathing, and lately, the patient may die due to pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]].

The SARS-CoV-2 novel coronavirus was identified in Wuhan, Hubei province of China in December 2019 by the Chinese Center for Disease and Prevention from the throat swab of a patient and the virus is named severe acute respiratory distress CoV-2 by WHO which causes Coronaviruses disease 2019 (COVID-19) [13,14]. The clinical manifestation of the current coronavirus infection is similar to the one that occurred in China in 2002 by the name severe acute respiratory distress syndrome [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]].

Approximately, 5 million confirmed cases and more than 300 thousand deaths were reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) as of May 22, 2020 [20]. The American region accounted for the highest number of cases and deaths which was 2.2 million and 132 thousand respectively. The European region accounted for the second-highest confirmed cases and death which was approximately 2 million confirmed cases and 170 thousand deaths. The total number of confirmed cases and death in the Eastern Mediterranean region accounted for approximately 400 thousand and 11 thousand respectively [20].

Though the COVID-19 pandemic has emerged in the Western Pacific region, China, Wuhan city, the number of infected cases, and deaths was the lowest as compared to the American and European regions. The number of laboratory-confirmed cases and deaths in the African region was the lowest for the last couple of months but the rate of spreading in this region is increasing at an alarming rate and is expected to be very high in the next couple of months if it continues as this rate [[20], [21], [22]].

The COVID-19 report in Ethiopia was very small which is 2500 confirmed cases and 27 deaths but there were many cases in short periods which is more than 150 cases per day. It is estimated that the number even may be very high because the diagnosis is limited only in the capital [23,24].

The challenge of COVID-19 is very high globally due to a lack of proven treatment and the complexity of its transmission [13,[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]]. However, it will be more catastrophic for low and middle-income countries because of very poor health care system, high illiteracy and low awareness of the disease and its prevention, lack of skilled health personnel, scarce Intensive Care Unit, a limited number of mechanical ventilators, and prevalence of co-morbidities/infection along with malnutrition.

The severity of the disease is depending on several factors. Studies showed that patients with co-morbidities including (Asthma, COPD, Tuberculosis, Pneumonia, Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, renal disease, hepatic disease, and cardiac disease), history of smoking, and history of substance use, male gender and age greater than 60 years were more likely to die or develop undesirable outcomes [6,28,[31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]].

The outcomes of patients with coronavirus infection are very variable. Studies revealed that in-hospital mortality of patients with COVID-19 was very high which varied from 1% to 52% of hospitalized patients [25,[27], [28], [29],36,[38], [39], [40], [41]]. Studies also showed that the rate of ICU admission among coronavirus infected patients was higher which ranged from 3% to 100% of confirmed cases [16,27,29,31,[42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. Studies also showed that the prevalence of mortality among intensive care patients with coronavirus infection was very high which ranged from 6% to 86% of admitted patients [16,27,29,31,[42], [43], [44], [45], [46]].

The global prevalence of mortality among hospitalized patients, number of cases requiring ICU care, number of cases need a mechanical ventilator, the prevalence of death in ICU, length of stay and independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality are very important variables to be determined to reduce patient mortality and morbidity through varies strategies including but not limited to increasing number of ICU beds, mechanical ventilator, skilled professionals, integrated monitors and reducing possible risk factors. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to provide global evidence on the prevalence and risk factors including age, gender, comorbidity, and substance use on hospital mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and registration

The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) protocols [47]. This systematic review and meta-analysis was registered in research registry with UIN of reviewregistry1093 and available at: https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#registryofsystematicreviewsmeta-analyses/

2.2. Eligibility criteria

2.2.1. Types of studies

All observational (case series, cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control) studies reporting the prevalence of mortality and its determinants among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) will be incorporated.

2.2.2. Types of participants

All participants with confirmed Coronaviruses admitted to the hospital for any kind of care will be included.

2.2.3. Outcomes of interest

The primary outcomes of interest were the global prevalence of mortality, morbidity, and complications among patients with Coronaviruses worldwide. Prevalence of ICU mortality Lengths of hospital stay and the number of days on a mechanical ventilator were secondary outcomes.

2.2.4. Context

This systematic review incorporated studies conducted worldwide to assess the prevalence of mortality and associated risk factors among hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

2.2.5. Inclusion criteria

The review included all cross-sectional studies and a single cohort conducted among adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 to assess mortality in patients with coronavirus infection.

2.2.6. Exclusion criteria

Studies that didn't report the prevalence of mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19, articles that didn't report full information for data extraction, articles with different outcomes of interest, studies with a methodological score less than fifty percent, studies with randomized controlled trials, case reports, and reviews were excluded.

2.3. Search strategy

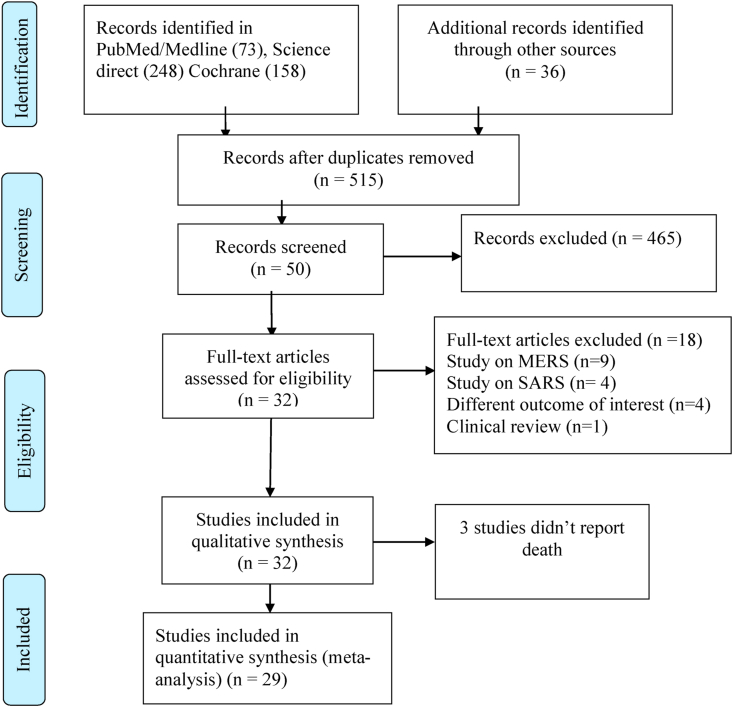

The search strategy was intended to explore all available published and unpublished studies among COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital from December 2019 to May 2020 without language restrictions. A three steps search strategy was employed in this review. An initial search on PubMed/Medline, Science Direct, and Cochrane Library was carried out followed by an analysis of the text words contained in Title/Abstract and indexed terms. A second search was undertaken by combining free text words and indexed terms with Boolean operators. The third search was conducted with the reference lists of all identified reports and articles for additional studies. Finally, an additional and grey literature search was conducted on Google scholars up to ten pages. The PubMed was searched with the following search terms using PICO strategy as: (coronavirus) or (coronavirus disease 2019)) or (SARS-CoV-2)) or (COVID-19)) and (mortality)) or (fatality)) or (morbidity)) or (comorbidity)) or (complications)) and (risk factors)) or (determinants)) and (prevalence)) and (global). The final search results were shown with the Prisma flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow chart.

2.4. Data extraction

The data from each study were extracted with two independent authors with a customized format excel sheet. The disagreements between the two independent authors were resolved by the other two authors. The extracted data included: Author names, country, date of publication, sample size, events mortality, need of mechanical ventilator, the number of days on a mechanical ventilator, presence of co-morbidities, and complication. Finally, the data were then imported for analysis in R software version 3.6.1 and STATA 14.

2.5. Assessment of methodological quality

Articles identified for retrieval were assessed by two independent Authors for methodological quality before inclusion in the review using a standardized critical appraisal Tool adapted from the Joanna Briggs Institute [48] (Supplemental Table 1) and a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions(AMSTAR2) [49]. The disagreements between the Authors appraising the articles were resolved through discussion with the other two Authors. Articles with average scores greater than fifty percent were included for data extraction.

2.6. Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out in R statistical software version 3.6.1 and STATA 14. The pooled global prevalence of mortality, comorbidity, and complication among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was determined with a random effect model as there was substantial heterogeneity. The Heterogeneity among the included studies was checked with forest plot, χ2 test, I2 test, and the p-values. Substantial heterogeneity among the included studies was investigated with subgroup analysis.

Publication bias was checked with a funnel plot and the objective diagnostic test was conducted with Egger's correlation, Begg's regression tests, and Trim and fill method. Furthermore, moderator analysis was carried out to identify the independent predictors of mortality among corona cases. The results were presented based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [47].

3. Results

3.1. Selection of studies

A total of 515 articles were identified from different databases and 50 articles were selected for evaluation after the successive screening. Thirty-two Articles with 23082 participants were included and the rest were excluded with reasons (Fig. 1).

3.2. Description of included studies

Thirty-two Articles with 23082 participants were included in the review while twenty-nine studies were included in the Meta-Analysis for the prevalence of mortality. Studies with the prevalence of mortality and/or prevalence of comorbidity and prevalence of complications among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 were included and the characteristics of each included studies were described in (Table 1) and the rest were excluded with reasons [15,17,19,27,42,[50], [51], [52], [54], [55], [56], [57]].

Table 1.

Description of included studies.

| Author | Year | Study period | Sample | Country | Follow up(days) | Prevalence of mortality(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young et al. [83] | 2020 | Jan 23 to Feb 3, 2020 | 18 | Singapore | 10 | – |

| Arentz et al. [44] | 2020 | Feb 20 to March 5, 2020 | 21 | USA | 15 | 52[30,74] |

| Bhatraju et al. [77] | 2020 | March 23, 2020 | 24 | USA | 1 | 50[29,71] |

| Huang et al. [62] | 2020 | Dec 16, 2019, to Jan 2, 2020 | 41 | China | 17 | 32[18,48] |

| Yang et al. [31] | 2020 | Dec 24, 2019 to Jan 26, 2020 | 52 | China | 31 | 62[47,75] |

| Xu et al.(12) | 2020 | Jan 10 to 26, 2020 | 62 | China | 16 | – |

| Tang et al. [67] | 2020 | Dec 24, 2019 to Feb 7, 2020 | 73 | China | 41 | 36[25,48] |

| Zhao et al. [73] | 2020 | Jan 21 to Feb 8, 2020 | 77 | China | 17 | 6[2,15] |

| Liu et al. [65] | 2020 | Dec 30, 2019 to Jan 15, 2020 | 78 | China | 16 | – |

| Wu et al. [70] | 2020 | Jan 22 to Feb 14, 2020 | 80 | China | 22 | 43[33,55] |

| Chen et al.(13) | 2020 | Jan 1 to Jan 20, 2020 | 99 | China | 19 | 11[6,19] |

| Cao et al. [58] | 2020 | Jan 3 to Feb 1, 2020 | 102 | China | 29 | 17[10,25] |

| Wu et al. [69] | 2020 | Dec 25, 2019 to Jan 26, 2020 | 201 | China | 32 | 3[0,9] |

| Bialek et al. [78] | 2020 | March 18, 2020 | 121 | USA | 1 | 45[36,55] |

| Simonnet et al. [82] | 2020 | Feb 27 to April 5, 2020 | 124 | France | 7 | 15[9,22] |

| Wang et al. [68] | 2020 | Jan 1 to 28, 2020 | 138 | China | 27 | 4[2,9] |

| McMichael et al. [79] | 2020 | Feb 28 to March 18, 2020 | 167 | USA | 30 | 21[15,28] |

| Guo et al. [75] | 2020 | Jan 23 to Feb 23, 2020 | 187 | China | 30 | 23[17,30] |

| Zhou et al. [74] | 2020 | January 2020 | 191 | China | 1 | 28[22,35] |

| Guan et al. [61] | 2020 | January 2019 | 1099 | China | 1 | 3[2,4] |

| Pan et al. [66] | 2020 | Jan 18 to Feb 28, 2020 | 204 | China | 15 | 18[13,24] |

| Chen et al.(16) | 2020 | Jan 20 to Feb 25, 2020 | 249 | China | 35 | 1[0,3] |

| Zhang et al. [72] | 2020 | Jan29 -Feb 12, 2020 | 258 | China | 13 | 6[3,9] |

| Zeng et al. [71] | 2020 | Jan 11 to Feb 29, 2020 | 338 | China | 49 | 1[0,3] |

| Li et al. [64] | 2020 | Feb 3 to March 3, 2020 | 548 | China | 30 | 16[13,20] |

| Cheng et al. [59] | 2020 | Feb 20, 2020 | 701 | China | 1 | 16[13,19] |

| Cheng et al. [59] | 2020 | Jan 28 to February 2020 | 710 | china | 3 | 13[10,15] |

| Jin et al. [63] | 2020 | Jan29 -Febr15,2020 | 1019 | China | 18 | 4[3,5] |

| Guan et al. [60] | 2020 | Dec 11, 2019 to Jan 31, 2020 | 1590 | China | 51 | 1[1,2] |

| Petrilli et al. [80] | 2020 | March 1 to April 7, 2020 | 1999 | USA | 34 | 15[13,16] |

| Richardson et al. [81] | 2020 | March 1 to April 4, 2020 | 3700 | USA | 31 | 15[13,17] |

| Mehra et al. [76] | 2020 | Dec 2019 to March 28, 2020 | 8910 | Multi- Country | – | 6[5,6] |

The included studies were published from December 16, 2019, to April 7, 2020, with sample sizes, ranged from 18 to 8910. The mean (SD) ages of the included studies varied from 38 to 59.7 years. The majority of the included studies, Twenty-three from thirty-two were conducted in China [12,13,16,31,37,[58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75]]. One study was conducted among 169 hospitals of Asia, Europe, and North America [76] while six studies were conducted in America [44,[77], [78], [79], [80], [81]] and the remaining two were conducted in Singapore and France [82,83].

Twenty-nine of the included studies reported the prevalence of mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 while three of the included studies didn't report the prevalence of mortality among COVID-19 patients in the hospital. The prevalence of mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 from the included studies varied from 1% to 52%.

Twenty-six studies with 22216 participants reported the prevalence of comorbidity including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, COPD, obesity as the major comorbidity among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 while sixteen studies with 8280 participants reporting the prevalence of complications including ARDS, acute kidney injury, liver dysfunction, sepsis and arrhythmia as the major complications. The prevalence of mortality among hospitalized patients with the newly emerging coronavirus was very high which varied from 3 to 100% of the intensive care unit admissions.

4. Meta-analysis

4.1. Global prevalence of mortality

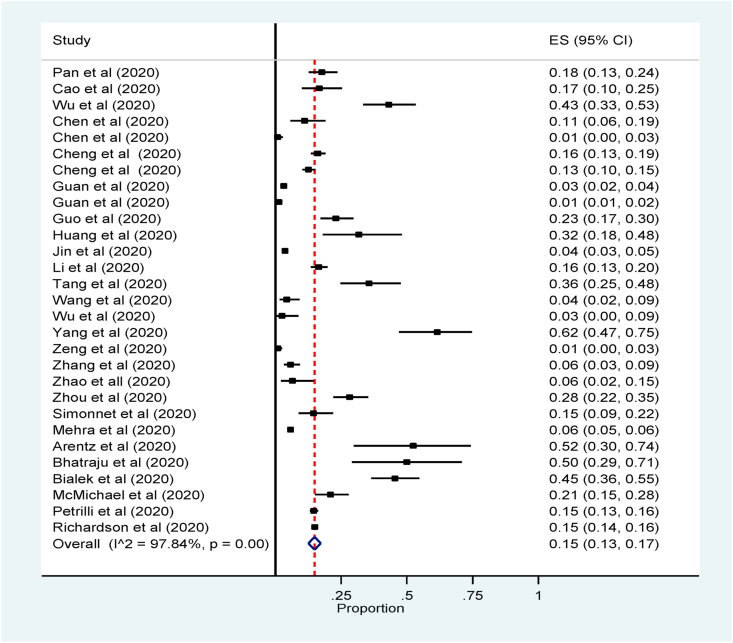

Twenty-nine studies reported prevalence and associated risk factors of mortality among hospitalized patients with coronavirus. The pooled prevalence of mortality was 15% (95% CI: 13 to 17, 29 studies, and 22924 participants) (Fig. 2). The subgroup analysis by country revealed that the mortality of patients with COVID-19 admitted in the hospital was the highest in USA followed by France 25% (95% CI: 19 to 30, 6 studies, 6032 participants) and 15% (95% CI: 9 to 22, one study, 124 participants) respectively (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for the prevalence of mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID: The midpoint of each line illustrates the prevalence; the horizontal line indicates the confidence interval, and the diamond shows the pooled prevalence.

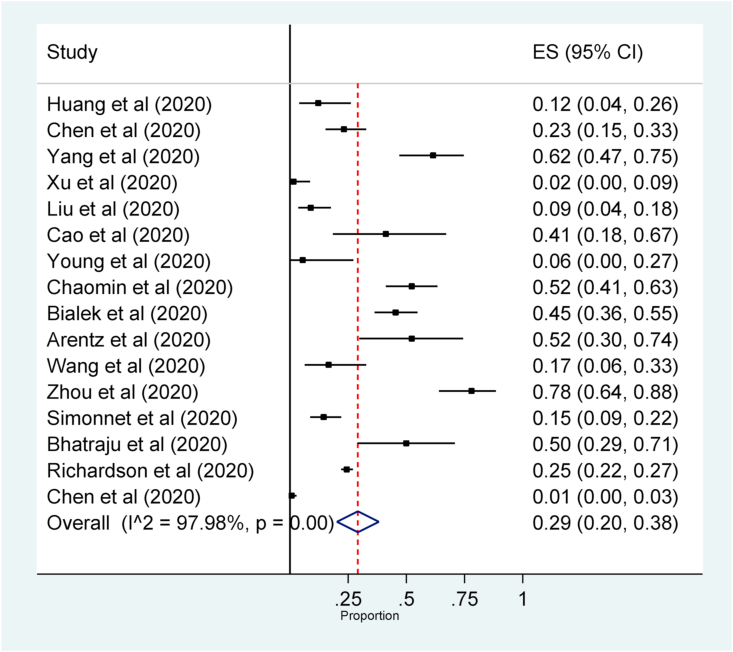

4.2. Prevalence of ICU mortality

The prevalence of mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in the Intensive Care Unit was 29% (95% CI: 20 to 38, 16 studies, 2227 participants) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for the prevalence of mortality among patients with Coronaviruses admitted in Intensive Care Unit: The midpoint of each line illustrates the prevalence; the horizontal line indicates the confidence interval, and the diamond shows the pooled prevalence.

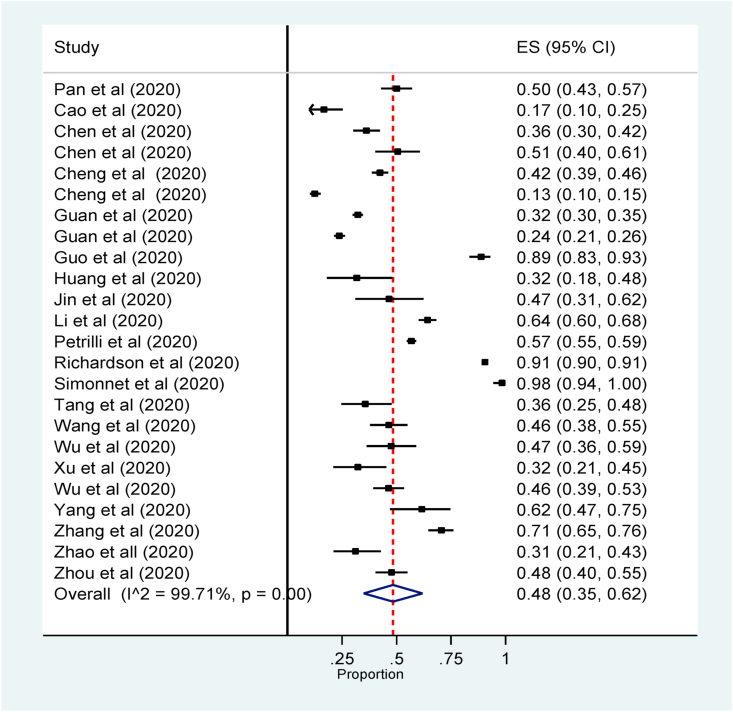

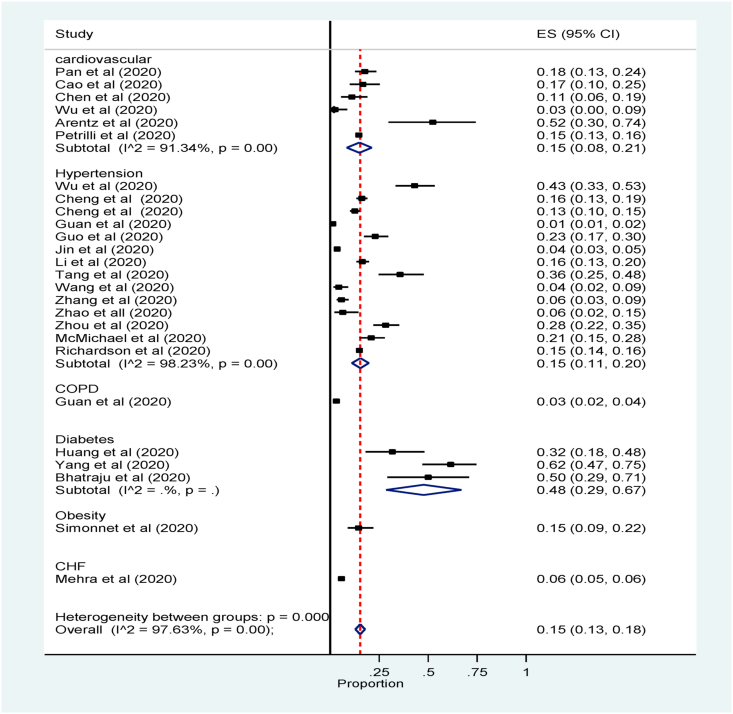

4.3. Prevalence of comorbidity

The Meta-Analysis revealed that the prevalence of comorbidity among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was 48% (95% confidence interval (CI):35 to 62, 26 studies, 22528 participants) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for the prevalence of comorbidity among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: The midpoint of each line illustrates the prevalence; the horizontal line indicates the confidence interval, and the diamond shows the pooled prevalence.

The subgroup analysis by the commonest comorbidities showed that diabetes mellitus was 48% (95% confidence interval (CI): 29 to 67, 3 studies, 117 participants) followed by hypertension and cardiovascular diseases 15% (95% confidence interval (CI):11 to 20, 14 studies, 8970 participants and 15% (95% confidence interval (CI): 8 to 21, 6 studies, 2505 participants) respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot for subgroup analysis of the prevalence of comorbidity among patients in hospital by major comorbidities. The midpoint of each line illustrates the prevalence; the horizontal line indicates the confidence interval, and the diamond shows the pooled prevalence.

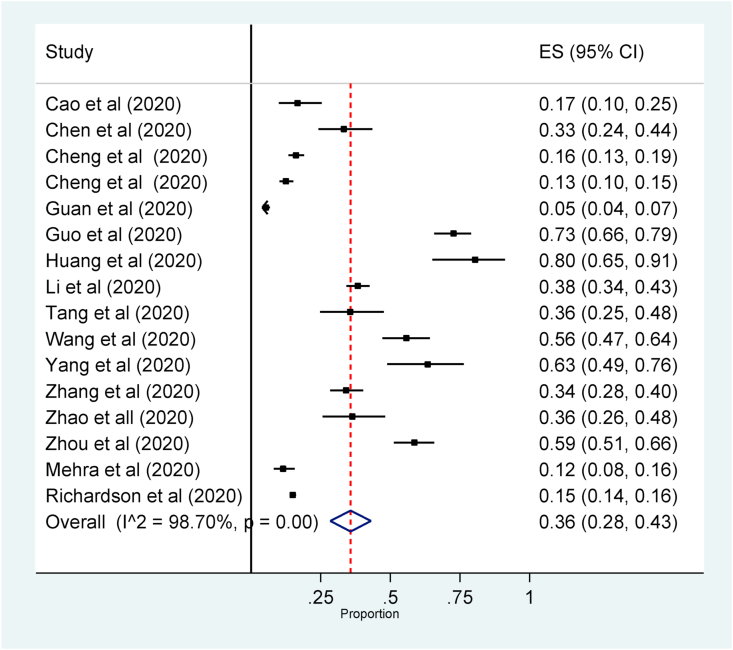

4.4. Prevalence of complications

Plenty of complications were mentioned in included studies including Acute Respiratory distress syndrome, acute kidney injury, sepsis, liver dysfunction, arrhythmia was the amongst reported as the common complications. The overall pooled prevalence of complications among hospitalized with COVID-19 was 36% (95% confidence interval (CI): 28 to 43, 16 studies, 8280 participants (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot for the prevalence of complication among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: The midpoint of each line illustrates the prevalence; the horizontal line indicates the confidence interval, and the diamond shows the pooled prevalence.

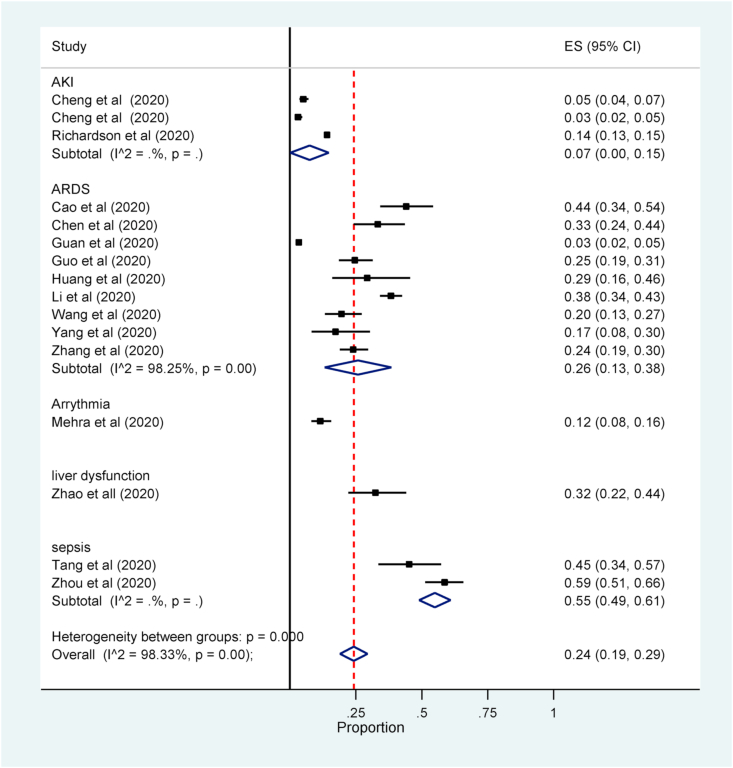

The Meta-Analysis revealed that sepsis was the most prevalent complication, 55% (95% confidence interval (CI):49 to 61, 2 studies, 246 participants) followed by Liver dysfunction and ARDS, 32% (95% confidence interval (CI): 23 to 44, one study, 77 participants and 26% (95% confidence interval (CI): 9 studies, 2524 participants) respectively (Fig. 7) (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Forest plot for subgroup analysis of the prevalence of complication among patients in hospital by major complication.: The midpoint of each line illustrates the prevalence; the horizontal line indicates the confidence interval, and the diamond shows the pooled prevalence.

Fig. 8.

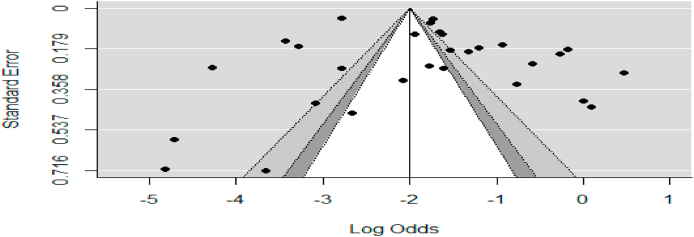

Funnel plot to assess publication bias. The vertical line indicates the effect size whereas the diagonal line indicates precision of individual studies with 95% confidence interval.

4.5. Determinants of mortality

The prevalence of mortality of patients with COVID-19 is greatly affected by several factors including but not limited to the presence of co-morbidities, history of smoking, male gender, older age groups, ICU admission, nosocomial infection, and others. Moderator analysis was conducted to identify the independent predictor of mortality among Coronavirus patients.

Mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was two times more likely in patients with any co-morbidity as compared to those who didn't have co-morbidities, RR = 2.20(95% CI:1.75 to 2.77). Acute respiratory distress syndrome was the most likely independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19. Those Patients with Acute respiratory distress syndrome were eight times more likely to die as compared to patients with no acute respiratory distress syndrome, RR = 7.99(95% CI: 4.9 to 13). Mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was two times more likely in a patient with a history of smoking as compared to nonsmokers, RR = 2.19(95% CI: 1.48 to 3.22). Mortality of patients among males with COVID-19 increased the risk by thirty-seven percent when compared to the female counterparts, RR = 1.63(95% CI: 1.33 to 1.99(Supplemental Fig. 2).

4.6. Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify the most influential study on the pooled summary effect and we didn't find a significant influencing summary effect. The funnel plot didn't show significant publication bias. Besides, egger's regression and Begg's correlation rank correlation failed to show significant difference (p < 0.05).

5. Discussion

The total laboratory confirmed infected cases and the death of patients with SARS-CoV-2 virus is unpredictably high as compared to the previous two outbreaks [15,17,18,27,29,54,56,84].

This Meta-Analysis revealed that the pooled global prevalence of mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was very high, 15% (95% CI: 13 to 17). This finding is in line with individual studies conducted among Coronavirus confirmed cases during the first outbreak in 2002, China [15,17,18,27,29,54,56,84]. The possible explanation for a high number of deaths among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 may be explained in terms of disease severity, presence of co-morbidities, inadequate laboratory investigation, complications, and some others. However, the finding of this review is higher than other systematic reviews conducted among patients with COVID-19 and this discrepancy might be due to the inclusion of plenty of studies [37,[85], [86], [87]].

The subgroup analysis showed that the prevalence of in-hospital mortality among COVID-19 patients was higher in the USA followed by France and China. This higher prevalence of in-hospital mortality in the USA compared to China might be due to the inclusion of a small number of studies from America as compared to china.

The Meta-Analysis revealed that the overall prevalence of comorbidities among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 was very high as compared to other systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis conducted to investigate the prevalence of comorbidity among COVID-19 patients [37,[86], [87], [88]]. This dissimilarity might be due to the inclusion of plenty of studies in this systematic review. The Meta-analysis also revealed that the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory disease which is comparable to other Meta-Analysis [37,[86], [87], [88]].

The systematic review showed that the prevalence of mortality among ICU admitted cases with Coronavirus was very high which is in line with systematic reviews conducted among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 [37,[85], [86], [87]].

The overall pooled prevalence of complications among hospitalized with COVID-19 was 36% (95% confidence interval (CI): 28 to 43, 16 studies. The subgroup analysis showed that sepsis was the highest prevalent followed by liver dysfunction and ARDS, unlike other systematic reviews where ARDS was the most prevalent complication. This discrepancy might be due to the number of included studies and sample size contribution.

The prevalence of mortality among patients with co-morbidities, history of smoking, gender, advanced age, and others was very high. Acute respiratory distress syndrome was the most likely independent predictor of in-hospital mortality.

5.1. Quality of evidence

The systematic review and meta-analysis included plenty of studies with adequate sample size. The methodological quality of included studies was moderate to high quality as depicted with Joanna Briggs Institute assessment tool for meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. However, substantial heterogeneity associated with dissimilarities of included studies in sample size, study setting, study design may limit generalization of this finding to the global community.

5.2. Limitation of the review

The review incorporated plenty of studies with a large number of participants but some of the included studies in this review didn't report risk factors, comorbidities, and complications for factor analysis. The included studies were conducted in a different setting with different sample sizes, population, and study design which caused substantial heterogeneity. Besides, there were a limited number of studies in some countries and it would be difficult to provide conclusive evidence with results pooled from fewer studies.

5.3. Implication for practice

The current COVID-19 pandemic is spreading swiftly around the world due to uncertain mode of transmission, lack of proven treatment and vaccination, incompliance of people with preventive measures. Body of evidence revealed that the global prevalence of mortality, morbidity, and complications among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was very high. The magnitude of this problem will be worse than this particularly in low and middle-income countries with weak health care systems and lack of well-equipped hospitals, ICU, skilled health care providers, quarantine centers, and laboratory centers. Therefore, global unity is highly required than ever to combat this deadly pandemic from the globe.

5.4. The implication for further research

The Meta-analysis revealed that the global prevalence of mortality, morbidity, and complications among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was very high and the major independent predictors were identified. However, the included studies were too heterogeneous, and cross-sectional studies also don't show temporal relationship outcomes and their determinants. Therefore, further observational and randomized controlled trials are in demand for specific comorbidity by stratifying the possible independent predictors.

6. Conclusion

The systematic review and Meta-Analysis revealed that the prevalence of mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was very high. The systematic review also showed that approximately fifty percent of patients hospitalized COVID-19 had one or more comorbidities and among which hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity were the most prevalent comorbidities. The prevalence of complications during hospitalization in patients with COVID-19 was as high as thirty-six percent. Sepsis, Acute liver failure, and ARDS were the most prevalent complications during hospitalization. Therefore, the body of evidence warns the health care stakeholders to give attention to hospitalized patients with COVID-19 through accessing mechanical ventilators, integrated patient monitors, skilled ICU staffs, creation of awareness about infection prevention and more others.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from Dilla University.

Sources of funding

The authors didn't receive any sources of funding for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Author contribution

Semagn Mekonnen Abate and Yigrem Ali Chekol conceived the idea and design of the project. Semagn Mekonnen Abate, Yigrem Ali Chekol, Bivash Basu, and Bahiru Mantefardo involved in searching strategy, data extraction, quality assessment, analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors approve the final manuscript.

Registration of research studies

1. Name of the registry: Prospero's international prospective register of systematic reviews.

2. Unique Identifying number or registration ID: CRD42020187721.

3. Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#recordDetails.

Guarantor

Semagn Mekonnen Abate, Corresponding Author.

Assistant professor of Anesthesiology.

Department of Anesthesiology.

College of Health Sciences and Medicine.

Dilla University.

Tel:+251913864605.

Consent

Consent was not applicable as we had collected data from previously published articles.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dilla University for technical support and encouragement to carry out the project.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102204.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- CI

confidence interval

- COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- COVID-19

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- RR

Relative Risk

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe Acute Respiratory Distress 2

- WHO

World Health Organization

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Wang L.-F., Shi Z., Zhang S., Field H., Daszak P., Eaton B.T. Review of bats and SARS. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12(12):1834. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss S.R., Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005;69(4):635–664. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.635-664.2005. Epub 2005/12/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong J., Goh Q.Y., Tan Z., Lie S.A., Tay Y.C., Ng S.Y. Preparing for a COVID-19 pandemic: a review of operating room outbreak response measures in a large tertiary hospital in Singapore. Can. J. Anaesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01620-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss S.R., Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005;69(4):635–664. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.635-664.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lau S.K., Chan J.F. Coronaviruses: emerging and re-emerging pathogens in humans and animals. BioMed Central. 2015;12:209. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0432-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu W., Tao Z.-W., Lei W., Ming-Li Y., Kui L., Ling Z. Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Chinese Med J. 2020;133(9):1032–1038. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Z., Hu Z. A review of studies on animal reservoirs of the SARS coronavirus. Virus Res. 2008;133(1):74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu D., Wu T., Liu Q., Yang Z. The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: what we know. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu J., Liu J., Zhao X., Liu C., Wang W., Wang D. Clinical characteristics of imported cases of COVID-19 in Jiangsu province: a multicenter descriptive study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(15):706–712. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J., Zhao S., Teng T., Abdalla A.E., Zhu W., Xie L. Systematic comparison of two animal-to-human transmitted human Coronaviruses: SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Viruses. 2020;12(2) doi: 10.3390/v12020244. Epub 2020/02/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu X.-W., Wu X.-X., Jiang X.-G., Xu K.-J., Ying L.-J., Ma C.-L. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020:368. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Organization W.H. vol. 72. 2020. (Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan J., Ng C., Chan Y., Mok T., Lee S., Chu S. Short term outcome and risk factors for adverse clinical outcomes in adults with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Thorax. 2003;58(8):686–689. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.8.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C.-Y., Lee C.-H., Liu C.-Y., Wang J.-H., Wang L.-M., Perng R.-P. Clinical features and outcomes of severe acute respiratory syndrome and predictive factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2005;68(1):4–10. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi K.W., Chau T.N., Tsang O., Tso E., Chiu M.C., Tong W.L. Outcomes and prognostic factors in 267 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003;139(9):715–723. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joynt G.M., Yap H. SARS in the intensive care unit. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2004;6(3):228. doi: 10.1007/s11908-004-0013-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lew T.W., Kwek T.-K., Tai D., Earnest A., Loo S., Singh K. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Jama. 2003;290(3):374–380. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Situation Report–123. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19):Situation Report –96. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19):Situation Report –39. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muscedere J., Waters B., Varambally A., Bagshaw S.M., Boyd J.G., Maslove D. The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(8):1105–1122. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4867-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carson S.S., Cox C.E., Holmes G.M., Howard A., Carey T.S. The changing epidemiology of mechanical ventilation: a population-based study. J. Intensive Care Med. 2006;21(3):173–182. doi: 10.1177/0885066605282784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Dorzi H.M., Aldawood A.S., Khan R., Baharoon S., Alchin J.D., Matroud A.A. The critical care response to a hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection: an observational study. Ann. Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0203-z. Epub 2016/10/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Dorzi H.M., Alsolamy S., Arabi Y.M. Critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Crit. Care. 2016;20(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arabi Y.M., Arifi A.A., Balkhy H.H., Najm H., Aldawood A.S., Ghabashi A. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;160(6):389–397. doi: 10.7326/M13-2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arentz M., Yim E., Klaff L., Lokhandwala S., Riedo F.X., Chong M. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. Jama. 2020;323(16):1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halim A.A., Alsayed B., Embarak S., Yaseen T., Dabbous S. Clinical characteristics and outcome of ICU admitted MERS corona virus infected patients. Egypt. J. Chest Dis. Tuberc. 2016;65(1):81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcdt.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai C.C., Shih T.P., Ko W.C., Tang H.J., Hsueh P.R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55(3):105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. Epub 2020/02/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Liu H., Wu Y. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8(5):475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M., Price C.S., Al Rabeeah A.A., Cummings D.A. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369(5):407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. Epub 2013/06/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu R., Ming X., Zhu H., Song L., Gao Z., Gao L. medRxiv; 2020. Association of Cardiovascular Manifestations with In-Hospital Outcomes in Patients with COVID-19: A Hospital Staff Data. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasmussen S.A., Smulian J.C., Lednicky J.A., Wen T.S., Jamieson D.J. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;222(5):415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saad M., Omrani A.S., Baig K., Bahloul A., Elzein F., Matin M.A. Clinical aspects and outcomes of 70 patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a single-center experience in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;29:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.09.003. Epub 2014/10/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. Epub 2020/02/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X., Pu K., Chen Z., Guo Q. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al Ghamdi M., Alghamdi K.M., Ghandoora Y., Alzahrani A., Salah F., Alsulami A. Treatment outcomes for patients with middle eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV) infection at a coronavirus referral center in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016;16:174. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1492-4. Epub 2016/04/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Hameed F., Wahla A.S., Siddiqui S., Ghabashi A., Al-Shomrani M., Al-Thaqafi A. Characteristics and outcomes of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus patients admitted to an intensive care unit in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Intensive Care Med. 2016;31(5):344–348. doi: 10.1177/0885066615579858. Epub 2015/04/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almekhlafi G.A., Albarrak M.M., Mandourah Y., Hassan S., Alwan A., Abudayah A. Presentation and outcome of Middle East respiratory syndrome in Saudi intensive care unit patients. Crit. Care. 2016;20(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1303-8. Epub 2016/05/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Dorzi H.M., Aldawood A.S., Khan R., Baharoon S., Alchin J.D., Matroud A.A. The critical care response to a hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection: an observational study. Ann. Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0203-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arabi Y.M., Murthy S., Webb S. COVID-19: a novel coronavirus and a novel challenge for critical care. Intensive Care Med. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05955-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arentz M., Yim E., Klaff L., Lokhandwala S., Riedo F.X., Chong M. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. Jama. 2020;323(16):1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., Yan W., Yang D., Chen G. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020:368. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Cardona-Ospina J.A., Gutiérrez-Ocampo E., Villamizar-Peña R., Holguin-Rivera Y., Escalera-Antezana J.P. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020:101623. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moola S. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E., Munn Z., editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shea B.J., Reeves B.C., Wells G., Thuku M., Hamel C., Moran J. Amstar 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Hameed F., Wahla A.S., Siddiqui S., Ghabashi A., Al-Shomrani M., Al-Thaqafi A. Characteristics and outcomes of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus patients admitted to an intensive care unit in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Intensive Care Med. 2016;31(5):344–348. doi: 10.1177/0885066615579858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Almekhlafi G.A., Albarrak M.M., Mandourah Y., Hassan S., Alwan A., Abudayah A. Presentation and outcome of Middle East respiratory syndrome in Saudi intensive care unit patients. Crit. Care. 2016;20(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1303-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M., Price C.S., Al Rabeeah A.A., Cummings D.A. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369(5):407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saad M., Omrani A.S., Baig K., Bahloul A., Elzein F., Matin M.A. Clinical aspects and outcomes of 70 patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a single-center experience in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;29:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chua S.E., Cheung V., Cheung C., McAlonan G.M., Wong J.W., Cheung E.P. Psychological effects of the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong on high-risk health care workers. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2004;49(6):391–393. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manocha S., Walley K.R., Russell J.A. Severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (SARS): a critical care perspective. Crit. Care Med. 2003;31(11):2684–2692. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000091929.51288.5F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garbati M.A., Fagbo S.F., Fang V.J., Skakni L., Joseph M., Wani T.A. A comparative study of clinical presentation and risk factors for adverse outcome in patients hospitalised with acute respiratory disease due to MERS coronavirus or other causes. PloS One. 2016;11(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cao J., Hu X., Cheng W., Yu L., Tu W.-J., Liu Q. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 18 patients with corona virus disease 2019 in intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05987-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheng Y., Luo R., Wang K., Zhang M., Wang Z., Dong L. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97(5):829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guan W-j, Liang W-h, Zhao Y., Liang H-r, Chen Z-s, Li Y-m. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with covid-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;55(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y., Liang W-h, Ou C-q, He J-x. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin J.-M., Bai P., He W., Liu S., Wu F., Liu X.-F. 2020. Higher Severity and Mortality in Male Patients with COVID-19 Independent of Age and Susceptibility. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li B., Yang J., Zhao F., Zhi L., Wang X., Liu L. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu W., Tao Z.-W., Wang L., Yuan M.-L., Liu K., Zhou L. Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Chin. Med. J. 2020;133(9):1032–1038. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pan A., Liu L., Wang C., Guo H., Hao X., Wang Q. Association of public health interventions with the epidemiology of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323(19):1915–1923. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tang X., Du R., Wang R., Cao T., Guan L., Yang C. Comparison of hospitalized patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by covid-19 and H1N1. Chest. 2020;158(1):195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Zhou X., Xu S., Huang H. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Int. Med. 2020;180(7):934–943. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu J., Liu J., Zhao X., Liu C., Wang W., Wang D. Clinical characteristics of imported cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Jiangsu province: a multicenter descriptive study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(5):706–712. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeng L., Li J., Liao M., Hua R., Huang P., Zhang M. 2020. Risk Assessment of Progression to Severe Conditions for Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia: a Single-Center Retrospective Study. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Y., Cui Y., Shen M., Zhang J., Liu B., Dai M. 2020. Comorbid Diabetes Mellitus Was Associated with Poorer Prognosis in Patients with COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao W., Yu S., Zha X., Wang N., Pang Q., Li T. Clinical characteristics and durations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Beijing: a retrospective cohort study. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.13.20035436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guo T., Fan Y., Chen M., Wu X., Zhang L., He T. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):811–818. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.10178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mehra M.R., Desai S.S., Kuy S., Henry T.D., Patel A.N. Cardiovascular disease, drug therapy, and mortality in Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2021225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 77.Bhatraju P.K., Ghassemieh B.J., Nichols M., Kim R., Jerome K.R., Nalla A.K. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region—case series. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2012–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Covid C., Team R. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69(12):343–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McMichael T.M., Currie D.W., Clark S., Pogosjans S., Kay M., Schwartz N.G. Epidemiology of covid-19 in a long-term care facility in king county, Washington. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2005–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Petrilli C.M., Jones S.A., Yang J., Rajagopalan H., O'Donnell L.F., Chernyak Y. 2020. Factors Associated with Hospitalization and Critical Illness Among 4,103 Patients with COVID-19 Disease in New York City. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Richardson S., Hirsch J.S., Narasimhan M., Crawford J.M., McGinn T., Davidson K.W. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. Jama. 2020;323(20):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Simonnet A., Chetboun M., Poissy J., Raverdy V., Noulette J., Duhamel A. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity. 2020;28(7):1195–1199. doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Young B.E., Ong S.W.X., Kalimuddin S., Low J.G., Tan S.Y., Loh J. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. Jama. 2020;323(15):1488–1494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee N., Chan K.A., Hui D.S., Ng E.K., Wu A., Chiu R.W. Effects of early corticosteroid treatment on plasma SARS-associated Coronavirus RNA concentrations in adult patients. J. Clin. Virol. 2004;31(4):304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alqahtani J.S., Oyelade T., Aldhahir A.M., Alghamdi S.M., Almehmadi M., Alqahtani A.S. Prevalence, severity and mortality associated with COPD and smoking in patients with COVID-19: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2020;15(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jain V., Yuan J.-M. 2020. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Predictive Symptoms and Comorbidities for Severe COVID-19 Infection. medRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zheng Z., Peng F., Xu B., Zhao J., Liu H., Peng J. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020;81(2):e16–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Emami A., Javanmardi F., Pirbonyeh N., Akbari A. Prevalence of underlying diseases in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of academic emergency medicine. 2020;8(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.