Abstract

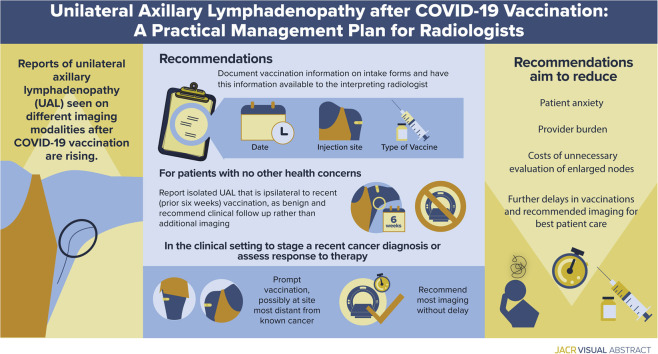

Reports are rising of patients with unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy, visible on diverse imaging examinations, after recent coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination. With less than 10% of the US population fully vaccinated, we can prepare now for informed care of patients imaged after recent vaccination. The authors recommend documenting vaccination information (date[s] of vaccination[s], injection site [left or right, arm or thigh], type of vaccine) on intake forms and having this information available to the radiologist at the time of examination interpretation. These recommendations are based on three key factors: the timing and location of the vaccine injection, clinical context, and imaging findings. The authors report isolated unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy (i.e., no imaging findings outside of visible lymphadenopathy), which is ipsilateral to recent (prior 6 weeks) vaccination, as benign with no further imaging indicated. Clinical management is recommended, with ultrasound if clinical concern persists 6 weeks after the final vaccination dose. In the clinical setting to stage a recent cancer diagnosis or assess response to therapy, the authors encourage prompt recommended imaging and vaccination (possibly in the thigh or contralateral arm according to the location of the known cancer). Management in this clinical context of a current cancer diagnosis is tailored to the specific case, ideally with consultation between the oncology treatment team and the radiologist. The aim of these recommendations is to (1) reduce patient anxiety, provider burden, and costs of unnecessary evaluation of enlarged nodes in the setting of recent vaccination and (2) avoid further delays in vaccinations and recommended imaging for best patient care during the pandemic.

Key Words: Lymphadenopathy, COVID-19, vaccination, primary health care, oncology

Visual Abstract

Background of COVID-19 Vaccination

The first coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination dose was administered on December 14, 2020, under emergency use authorization from the US Food and Drug Administration, and as of March 5, 2021, more than 82 million doses have been administered in the United States, and 8.4% of the US population has been fully vaccinated [1]. Reactions to the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccinations are common, with more than 85% of patients reporting local reactions at the injection site and more than 75% reporting systemic reactions. The most common unsolicited adverse event reported is unilateral “axillary swelling or tenderness” by 10.2% of patients after the first Moderna vaccine and 14.2% of patients after the second Moderna injection. Patients receiving the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccination have also reported increased rates of palpable unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy (UAL) compared with those receiving a placebo [2, 3, 4, 5].

Postvaccination Lymphadenopathy on Imaging

The percentages of the self-reported symptomatic UAL just discussed likely represent a subset of the percentage of patients actually experiencing this effect and no doubt an even smaller percentage of patients whose imaging after COVID-19 vaccination will reveal UAL.

Post–COVID-19 vaccination subclinical UAL was first reported on imaging in January 2021, identified incidentally in two women during screening breast ultrasound and in one woman on short-interval follow-up ultrasound of bilateral breast masses [6]. Three cases were subsequently reported in patients undergoing screening breast MRI [7,8] and two in patients undergoing chest CT [8]. At this time, several subsequent cases of benign UAL after COVID-19 vaccination have been published [9, 10, 11, 12, 13].

Rare cases of UAL identified on imaging after recent ipsilateral upper extremity vaccination have been documented after other vaccinations, including seasonal influenza, bacillus Calmette-Guérin, human papillomavirus, and H1N1 [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21]. In these prior settings, vaccine-induced lymphadenopathy resulted in false-positive results on PET and CT examinations. Lymphadenopathy was visible on imaging as early as 1 day after vaccination [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21] and in some cases persisted more than 1 month after vaccination [10,18].

As the COVID-19 vaccines provoke a highly immunogenic clinical response in patients, it is reasonable to predict increased frequency of UAL on imaging after COVID-19 vaccination than that reported after other vaccinations, and it is likely that the UAL on imaging may persist beyond 1 month after the final dose.

Management Recommendations: Overview

In this early phase of COVID-19 vaccinations, management plans for UAL in the clinical setting of recent vaccination vary widely across practices and include assessment as “benign” or “normal” with or without clinical follow-up, immediate additional imaging, short-interval follow-up imaging (until resolution is documented), and biopsy [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13,22, 23, 24].

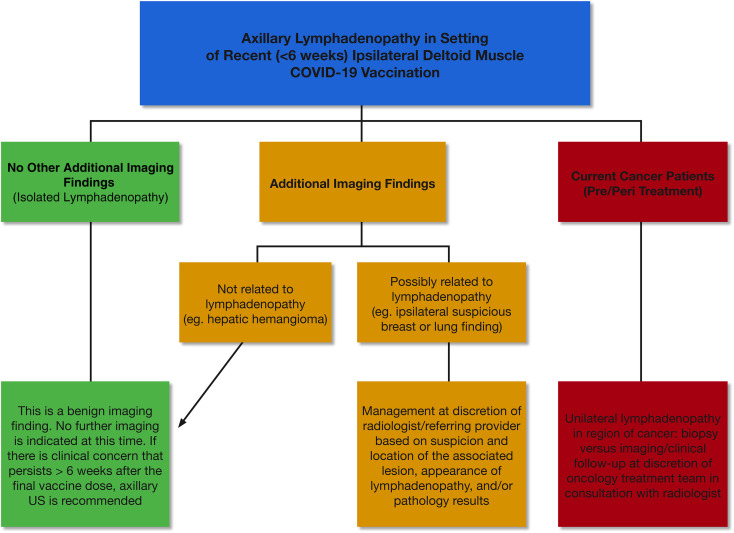

Although most cases reported to date have involved patients undergoing breast imaging, we have observed increased incidence of patients with UAL on other imaging examinations, particularly in oncologic imaging. To guide management across multiple subspecialties in radiology, we first categorize the UAL as presenting in one of three scenarios: (1) as an isolated finding on imaging, (2) in conjunction with another finding on imaging, and (3) in a patient undergoing cancer staging and/or treatment (Fig. 1 ).

Fig 1.

Algorithm for axillary lymphadenopathy in the setting of recent (within 6 weeks) ipsilateral deltoid muscle coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination across specialties.

Exclusions

Patients with remote vaccination history, bilateral lymphadenopathy, and palpable lymphadenopathy are excluded from this management plan. Patients vaccinated more than 6 weeks in the past are managed according to standard “non-COVID-19 vaccination” protocols across subspecialties, as are patients with bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy. We distinguish clinically suspicious, palpable lymphadenopathy presenting for diagnostic imaging from lymphadenopathy noted on imaging as an incidental finding. In the former case, we advocate clinical management, and if clinical concerns persist 6 weeks after final vaccination dose, we recommend ultrasound for further evaluation and possible biopsy.

Breast Imaging

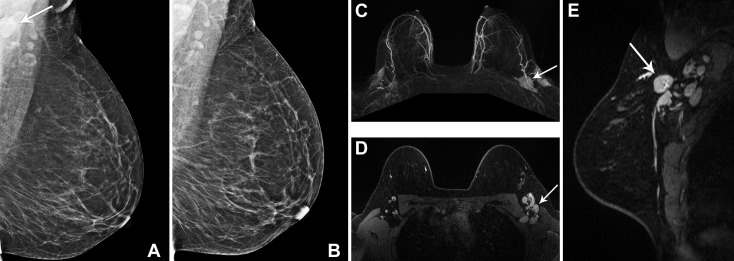

The first reports of subclinical UAL after COVID-19 vaccinations were made by breast imagers and identified in women undergoing screening MRI, ultrasound, and mammography [6, 7, 8]. The Society of Breast Imaging responded rapidly with guidelines and educational materials for radiologists, referring providers, and patients. Suggestions included collecting vaccination history on intake forms and educating patients that axillary swelling is a normal response to vaccinations. For subclinical UAL on screening, the Society of Breast Imaging supports BI-RADS® category 0 assessment to bring screening patients back for further assessment of the ipsilateral breast and documentation of medical and vaccination history. BI-RADS category 3 is then recommended with follow-up at 4 to 12 weeks after the second dose and consideration of BI-RADS category 4 (biopsy) if the lymphadenopathy persists on short-interval follow-up [24]. Other centers, including ours, recommend consideration of a benign assessment (BI-RADS category 2) with clinical follow-up for subclinical isolated UAL in the setting of a known recent COVID-19 vaccination in the ipsilateral arm, and we believe that this is consistent with the ACR BI-RADS recommendations for UAL in the setting of a known inflammatory cause [22,23,25]. Our specific recommendations have been previously published; briefly, for all patients undergoing breast imaging, we collect vaccination history at the time of the examination, and we tailor our recommendations for three specific clinical settings: screening, diagnostic imaging, and patients in the pre- or peri-treatment phase of current breast cancer diagnosis [22] (Fig. 2 ).

Fig 2.

(A,B) A 52-year-old woman with a history of right breast invasive ductal malignancy, status post lumpectomy and radiation, presented for routine yearly screening mammogram, 22 days after her second dose of the Moderna coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in the left deltoid muscle. (A) Left mediolateral oblique mammographic view demonstrated a single prominent lymph node in the left axilla (arrow), which was more prominent compared with (B) screening mammography performed 1 year previously. (C-E) A 33-year-old woman with a family history of breast cancer presented for baseline high-risk screening breast MRI, 1 day after her second dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine in the left deltoid muscle. Multiple enlarged left axillary level 1 and 2 lymph nodes (arrows) were noted on the (C) 3-D axial maximum-intensity projection, (D) T1-weighted fat-saturated postcontrast axial, and (E) sagittal images. In both patients, the left axillary lymphadenopathy was an isolated finding with no abnormality in the bilateral breasts. Given recent COVID-19 vaccination, the cases were interpreted as BI-RADS category 2 (benign). The report impression stated, “Enlarged lymph nodes in the left axilla are benign. In the specific setting of the patient’s documented recent (within 6 weeks) COVID-19 vaccination in the ipsilateral arm, axillary adenopathy is a benign imaging finding. No further imaging is indicated at this time. If there is clinical concern that persists more than 6 weeks after the patient’s final vaccine dose, axillary ultrasound is recommended.”

Lung Cancer Screening

Annual lung cancer screening with low-dose chest CT has been shown to reduce lung cancer–specific and all-cause mortality in select high-risk populations, and more than 620,000 studies were performed in 2019 in the United States alone [26, 27, 28]. One of the earlier reports of UAL after COVID-19 vaccination was identified on chest CT and appropriately suggested that this may have implications to those undergoing lung cancer screening [8].

Indeterminate extrapulmonary lesions are a common incidental finding on lung cancer screening. Most of these indeterminate lesions are ultimately determined to be benign, but a small subset, including cases of axillary lymphadenopathy, are found to be malignant [29]. No specific guidelines address management of incidental UAL on lung cancer screening. An ACR white paper addressing the management of incidental mediastinal findings on chest CT, however, recommended further workup (i.e., clinical consultation, PET/CT, or follow-up CT) only in those with mediastinal lymph nodes greater than 15 mm in the short axis without explainable disease [30].

We believe that a similar conservative approach can be safely applied to UAL identified during lung cancer screening after recent COVID-19 vaccination. In such cases, UAL can be reported as a potentially significant finding using the “S” modifier of the Lung-RADS™ reporting system, with clear communication that the UAL is likely reactive and that no further imaging is necessary unless clinical concerns persist 6 weeks after the final dose of COVID-19 vaccine (Fig. 3 ).

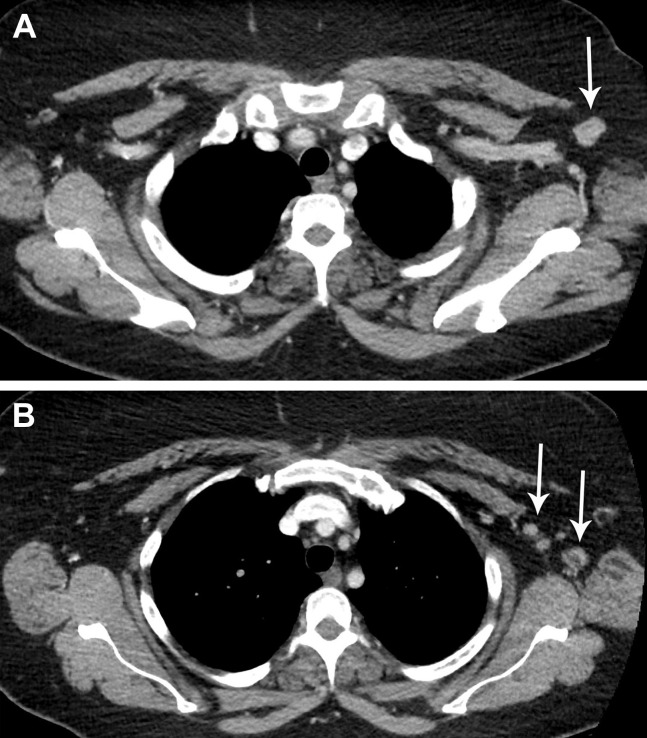

Fig 3.

A 64-year-old man, with a 30-pack-year smoking history, presented for lung cancer screening chest CT, 10 days after receiving his first dose of the Moderna coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine in the left deltoid muscle. Low-dose non-contrast-enhanced CT coronal imaging showed asymmetric mild enlargement of several left axillary lymph nodes (arrows). The findings were otherwise negative for suspicious pulmonary nodules. Given recent COVID-19 vaccination, the case was interpreted as Lung-RADS category 2. The axillary lymphadenopathy was reported as a “potentially significant finding” using the Lung-RADS “S” modifier. The recommendation was to return to routine annual lung cancer screening. No additional imaging evaluation for the isolated axillary lymphadenopathy was recommended, unless it increases or persists for more than 6 weeks, at which point ultrasound may be considered.

Surveillance of Patients With Cancer for Recurrence After Treatment

Although no national-level data exist, at our institution surveillance imaging examinations for patients after cancer treatment constitute the second largest population of cancer-related CT examinations, after those with active disease and above screening, including a combination of CT and PET/CT. And with more than 75 million CT scans performed per year in the United States, cancer-related surveillance imaging likely contributes many millions of CT scans per year [31]. Consensus guidelines for post-treatment surveillance vary by cancer type and stage at presentation and may be adjusted by institution-specific policies. Generally, however, when cross-sectional surveillance is appropriate, including CT surveillance for prostate, melanoma, colon, and lung cancer, intervals typically range from every 6 months to every 2 years in patients without evidence of disease, some cases tapering after consecutive years of no evidence of disease [32,33].

The presentation after vaccination of new UAL on surveillance imaging, without other evidence of disease, can be a challenge for the radiologist and care team. Management ultimately should be tailored to the patient’s pretest probability of malignant spread versus benign reaction to recent vaccination. Considerations in the assessment of pretest probability of malignancy include local site of the primary malignancy, common drainage pathways, time since vaccination, prognosis, and overall risk profile. Management consensus is also an opportunity for informed consent and shared decision making with the patient, radiologist, and clinical care team and should be an opportunity to improve patient engagement.

In our patients undergoing surveillance imaging for UAL that is ipsilateral to the vaccine administration arm and within 6 weeks of administration, we recommend clinical follow-up with no further imaging. If the UAL is either contralateral to or beyond 6 weeks after vaccination, we recommend follow-up imaging. Specifics of follow-up imaging are based on the cancer type and may include ultrasound if the findings are localized, CT of the chest (with possible addition of the abdomen and pelvis) if there are concerns for a more systemic process, and PET/CT if there is a strong clinical concern for malignancy. In the case of persistent or worsening lymphadenopathy on the follow-up examination, tissue sampling should be considered (Fig. 4 and 5 ).

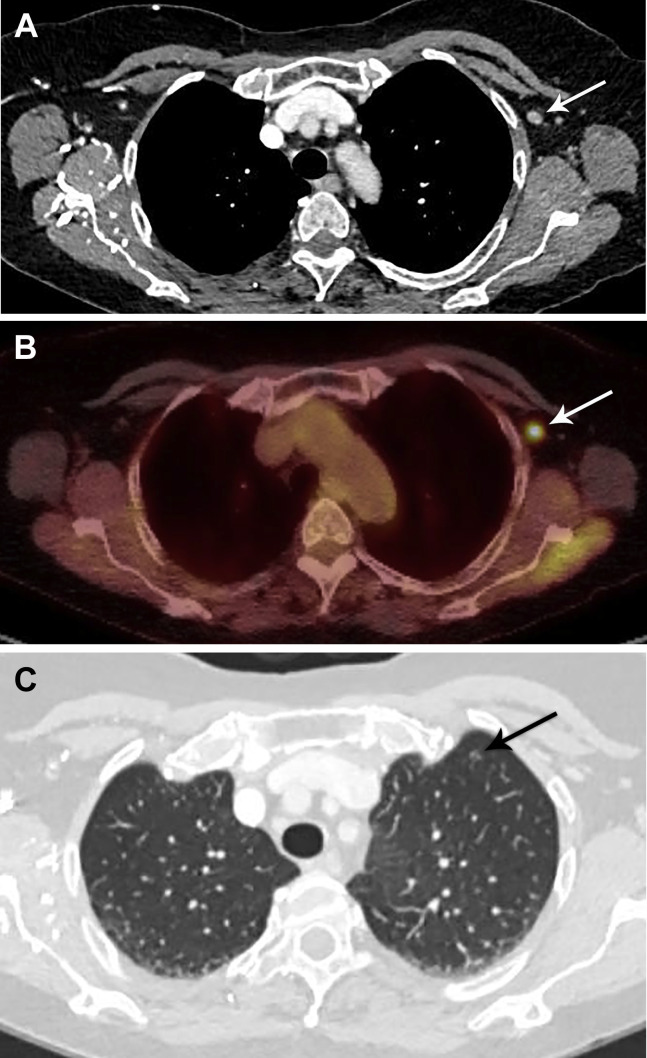

Fig 4.

A 70-year-old woman with a history of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (stage IA, groin), status post chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, presented for routine surveillance 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT. She was in a clinical trial without active disease. The patient had received the second dose of the Moderna coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in the left deltoid muscle 3 days before her scan. (A) Chest CT demonstrated slight enlargement of left axillary lymph nodes measuring up to 7 mm (short axis), (B) which showed intense FDG uptake on PET. (C) A left upper lobe subsolid nodule (arrow) and multiple additional tiny solid nodules up to 3 mm (not shown) were stable compared with prior imaging. There were no new findings in the chest, abdomen, or pelvis to suggest active disease. The patient will undergo follow-up chest CT in 3 months to reassess unrelated incidental pulmonary nodules, and the left axillary lymph nodes will be reassessed at that time.

Fig 5.

A 51-year-old woman with a history of left lower extremity cutaneous melanoma (stage IIB) presented for routine oncologic follow-up and surveillance 3 days after receiving her first dose of the Moderna coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine in the left deltoid muscle. The primary tumor was resected 2 years prior, and she was in a clinical trial for adjuvant immunotherapy (versus placebo). Surveillance imaging studies 6 months before the current examination revealed no evidence of metastatic disease. (A,B) Axial contrast-enhanced CT images of the chest showed asymmetric mild enlargement of several left axillary and subpectoral lymph nodes (arrows) measuring up to 13 mm (short axis). The remainder of the chest CT study was otherwise unremarkable, without additional sites of lymphadenopathy or evidence of metastatic disease. After deliberation, it was recommended that the patient return to routine oncologic follow-up, with plans for routine repeat surveillance imaging in 6 months.

Current Cancer Patients: Staging and Response to Therapy

The unprecedented disruption to health care caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected the management of oncology patients. This impact is not only related to higher mortality in patients with cancer and COVID-19 but also stems from adverse outcomes due to delayed diagnosis, disruption to chemotherapy or surgical therapy, and missed or interrupted imaging surveillance. The widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines has generated hope for a return to normalcy for patients with cancer, with resumption of screening and imaging surveillance. However, rising reports of lymphadenopathy in patients receiving COVID-19 vaccines are likely to create a clinical conundrum in the management of patients with newly diagnosed cancer or patients with cancer receiving systemic therapy. Incidental detection of enlarged nodes on staging or restaging scans will not only confound the accurate assessment of treatment response but also may increase patient anxiety and lead to additional investigations and needless interventions. Although interventions can cause patient complications, they also contribute to a growing health care burden. In this era of precision medicine, the rising use of novel targeted and immunotherapeutic agents has led to the emergence of unique manifestations of imaging such as pseudo-progression. Recognition of lymphadenopathy while a patient is on treatment with newer immunotherapeutic agents and receives a COVID-19 vaccine is likely to affect precise determination of treatment response and therefore create disarray in large oncology trials.

The initial reports of lymphadenopathy have been limited to axillary and cervical region, including the supraclavicular nodes. Metastases to axillary and neck nodes are typically encountered with breast cancer, lung cancer, lymphoma, and head and neck malignancies. However, cervical lymphadenopathy, particularly in the supraclavicular chain, can occur in patients with gastroesophageal cancer and pancreatic cancer and is considered a sign of metastases or stage IV disease. This has important implications in triaging patients to appropriate oncologic management of surgical resection versus systemic chemotherapy.

In our oncologic imaging practices, we support the following: (1) documentation of COVID-19 vaccine history in the oncology records to ensure its acknowledgment and consideration for timing of imaging and cancer care; (2) education and awareness of vaccine-induced lymphadenopathy for radiologists, the multidisciplinary oncology care team, and patients; and (3) focused efforts to reassure and counsel patients as they navigate cancer treatment through the pandemic. Concerns or confusion regarding vaccine-induced lymphadenopathy should not delay COVID-19 vaccination, particularly as mortality related to COVID-19 is higher among patients with cancer than the general population [34].

In patients with lymphadenopathy ipsilateral to recent vaccination, management decisions should be individualized on the basis of the type of cancer, staging, lymph node drainage pathway, and overall risk profile. We support the recent recommendations by a panel from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the MD Anderson Cancer Center, and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, which encourage multidisciplinary engagement to tailor patient management on the basis of the likelihood that the lymphadenopathy is a reactive response to vaccination versus malignancy [10]. On the basis of the overall risk profile and in consideration of the patient’s desires, the full spectrum of management options may be considered, from clinical management without further imaging (for the lowest nodal metastatic risk patients) through immediate additional imaging, short-interval follow-up imaging, to biopsy (for the highest nodal metastatic risk patients). For patients who undergo short-interval imaging follow-up, time to resolution of UAL on imaging is currently unknown and likely to vary by examination type (eg, PET/CT versus mammography) and patient characteristics (eg, age, comorbidities). Detailed decisions tailored to the individual patient are best supported in a multidisciplinary setting with proper documentation and after discussion with and input from the patient (Figs. 6 and 7 ).

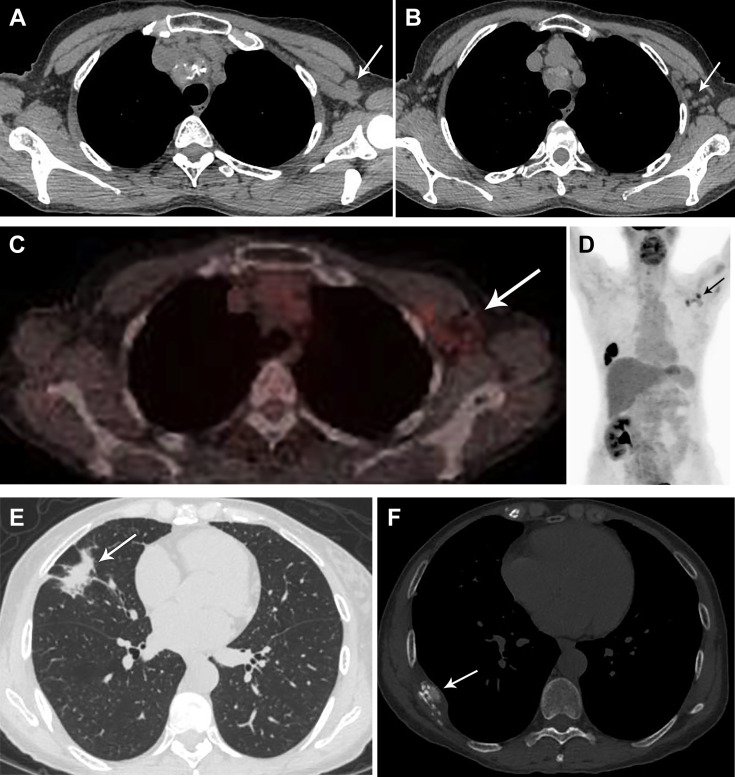

Fig 6.

A 59-year-old woman with current metastatic squamous cell lung cancer (stage IV), status post chemotherapy and radiation, presented for routine surveillance 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT. The patient had received the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in the left deltoid muscle 5 days before imaging. (A,B) Chest CT demonstrated new left axillary lymphadenopathy, (C,D) with moderate to intense uptake on FDG PET. (E) In the right middle lobe, at the site of primary malignancy, nodularity was identified along the area of radiation fibrosis. (F) There was interval progression of a right eighth posterolateral rib lytic metastasis (arrow). Given recent COVID-19 vaccination, the left axillary lymph nodes were assessed as likely reactive. Attention on follow-up studies was advised.

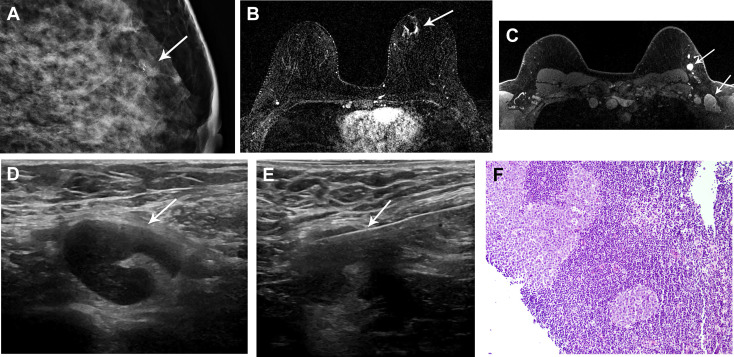

Fig 7.

A 42-year-old woman, with a family history of breast malignancy, presented with (A) left breast upper inner quadrant fine-linear calcifications (arrow) on screening mammography. The patient underwent stereotactic core-needle biopsy yielding invasive ductal carcinoma, grade 2, estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive. The patient had received the first dose of the Moderna coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine in the left deltoid muscle 12 days before preoperative MRI. (B) Axial T1-weighted fat-saturated postcontrast subtracted MR image demonstrated 9 mm of nonmass enhancement corresponding to the biopsy-proven malignancy and a small hematoma (arrow). (C) Axial T1-weighted fat-saturated postcontrast MR image demonstrated level 1 and level 2 axillary lymphadenopathy (arrows). No additional findings were detected in the left or right breast, in keeping with unifocal malignancy. (D) Targeted left axillary ultrasound demonstrated corresponding lymphadenopathy with cortical thickening up to 6 mm (arrow). In consultation with the patient’s breast surgeon, the decision was made to pursue axillary lymph node biopsy. (E) Subsequent ultrasound-guided biopsy of lymph node (arrow) demonstrated (F) fragments of reactive lymph node negative for carcinoma. Image courtesy of Drs Veerle Bossuyt and Melanie Kwan, Anatomic Pathology.

Consensus Across Recommendations

At this time, three reports have been published to provide guidance in the breast imaging and cancer center settings [10,22,24]. All support the following principles: (1) vaccinations should not be delayed; (2) vaccination history should be available to the radiologist at time of interpretation of imaging examination; (3) in the context of known recent vaccination, ipsilateral UAL can be managed clinically without further imaging on the basis of low pretest probability of malignant lymphadenopathy; and (4) patient and referring provider education is essential to avoid confusion and further delays in vaccinations or recommended usual health care.

Timing of Vaccinations and Imaging

Although there is general agreement that vaccinations should not be delayed, some recommend performing any recommended imaging before vaccination. On the basis of the local resources, patient populations, and access to timely imaging, this approach may inadvertently delay or reduce patient engagement in vaccination programs. Also, perspectives differ regarding postponing imaging until after vaccination. One panel recommended consideration of postponing imaging for screening, routine surveillance, and staging for at least 6 weeks after final vaccination dose [10], and another recommended postponing mammography screening until 4 to 6 weeks after the final vaccination dose and postponing short-interval follow-up for 4 to 12 weeks after the final vaccination dose [24].

After discussion with our primary care colleagues and in careful review of the impact of the pandemic on patient engagement in breast cancer screening, we opted to continue to screen patients without adding further complexities or unintended barriers to screening by delaying or rescheduling examinations [22]. Although adjusting scheduling of vaccinations or screening mammographic examinations for average-risk women is not advised, postponing imaging may be reasonable for smaller groups of select patients undergoing surveillance imaging with CT, PET/CT, ultrasound, or MRI. At some centers, screening and/or surveillance examinations may be offered in concert with vaccinations performed on the same day to reduce patient burden and support patient engagement in both domains.

Mitigating Unintended Impact on Our Most Vulnerable Populations

The pandemic has exacerbated health care disparities. As we consider management of UAL after COVID-19 vaccination and our messaging to the full diversity of patients we serve, care in education and communication is paramount to reduce increasing burdens on our most vulnerable patients. Rescheduling imaging or vaccinations no doubt will be easier for some populations in certain health care environments than others. Recommendations to reschedule imaging or vaccinations may discourage racial/ethnic minorities from engaging with health systems at a critical moment, because racial/ethnic minority populations are more likely to experience both COVID-19 and delayed cancer diagnoses. In the specific setting of dramatically increased barriers to routine health care and strained health care resources because of the pandemic, we continue to focus our efforts to bring patients in for recommended imaging and to use a pragmatic approach for our radiologists and health care team to manage UAL in the setting of recent vaccination.

Additional Considerations

Clear and consistent communication of pragmatic management protocols can reduce potential confusion for both patients and referring providers. Advanced planning can support our patients to feel confident and safe to receive their vaccinations as well as undergo recommended imaging in their usual care. For breast imaging centers, from which letters are sent directly to patients in lay language, there are resources for sample letters explaining COVID-19 vaccine–related UAL [17, 18, 19]. These can be tailored to support direct communication to patients undergoing other imaging examinations as well.

Recording vaccination status (date[s] of vaccination[s], injection site [left or right, arm or thigh], type of vaccine) of all patients presenting for imaging and having that information readily available to the radiologist at the time of interpretation can reduce unnecessary return visits by the patient and/or delays in final assessment. This practice can be tailored to the local environment and resources, either added to the radiology order or obtained when the patient arrives for the imaging examination. For centers that opt to schedule examinations 4 to 6 weeks after vaccination, vaccination information could be confirmed at the time of examination scheduling.

To further decrease the risk for a false-positive assessment of benign reactive UAL, patients who have current or prior cancer diagnoses can request that their injections be performed at the site most distant from the location of the cancer. For example, a patient with breast cancer could request the vaccination in the contralateral arm or in the thigh. The Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention support injection in either the deltoid muscle or the anterolateral thigh [35, 36, 37].

Summary

Knowledge of patient vaccination history and common presentation of benign reactive lymphadenopathy after COVID-19 vaccination can mitigate false-positive assessments, unnecessary additional imaging, and biopsies throughout the COVID-19 vaccination period. Our current management recommendations will continue to be updated as more data are available to guide best practice. During these times of uncertainty, radiologists certainly may use discretion in tailoring these recommendations to patient and referring provider preferences, available resources, and the specific patient’s clinical presentation and imaging findings.

Take-Home Points

-

▪

COVID-19 vaccination in the deltoid muscle is associated with clinically palpable ipsilateral axillary lymphadenopathy in at least 15% of patients after the second injection. As the vaccine becomes more available and a wider patient population is vaccinated, we anticipate that significantly more patients will demonstrate subclinical lymphadenopathy on imaging.

-

▪

In most clinical settings, ipsilateral lymphadenopathy post recent COVID-19 vaccination is a benign imaging finding, and clinical follow-up is recommended.

-

▪

With <10% of the population fully vaccinated, we can reduce future unnecessary additional imaging, workup and intervention, and anxiety and confusion among referring providers and patients when benign reactive isolated axillary lymphadenopathy is identified on imaging after recent COVID-19 vaccination.

-

▪

Clear and concise subspecialty imaging information and recommendations are necessary to help clinicians take more informed and efficacious care of their patients without delays or reductions in vaccinations or preventive screening and diagnostic imaging examinations.

Footnotes

Dr Kambadakone receives institutional research support from GE Healthcare, Philips Healthcare, and PanCAN, United States; is an advisory board member for Bayer; and is a speaker and consultant for Philips Healthcare. Dr Lehman receives institutional research support from GE Healthcare, Hologic, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the National Cancer Institute (grant U01CA225451); and is a cofounder of Clairity. Dr Succi receives patent royalties from Frequency Therapeutics and financial compensation as both equity and compensation from 2 Minute Medicine. All other authors state that they have no conflict of interest related to the material discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID data tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations Available at:

- 2.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Local reactions, systemic reactions, adverse events, and serious adverse events: Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. December 13, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/reactogenicity.html Available at:

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Local reactions, systemic reactions, adverse events, and serious adverse events: Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. December 20, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/moderna/reactogenicity.html Available at:

- 6.Mehta N., Sales R.M., Babagbemi K. Unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy in the setting of COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Imaging. 2021;75:12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edmonds CE, Zuckerman SP, Conant EF. Management of unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy detected on breast MRI in the era of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccination. AJR Am J Roentgenol. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ahn R.W., Mootz A.R., Brewington C.C., Ababa S. Axillary lymphadenopathy after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Radios Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021;3 doi: 10.1148/ryct.2021210008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Özütemiz C, Krystosek LA, Church AL et al. Lymphadenopathy in COVID-19 vaccine recipients: diagnostic dilemma in oncology patients. Radiology. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Becker AS, Perez-Johnston R, Chikarmane SA, et al. Multidisciplinary recommendations regarding post-vaccine adenopathy and radiologic imaging: radiology scientific expert panel. Radiology. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Hanneman K, Iwanochko RM, Thavendiranathan P. Evolution of lymphadenopathy at PET/MRI after COVID-19 vaccination. Radiology. In press.

- 12.Washington T., Bryan R., Clemow C. Adenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination. Radiology. 2021 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021210236. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mortazavi S. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccination associated axillary adenopathy: imaging findings and follow-up recommendations in 23 women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Panagiotidis E., Exarhos D., Housianakou I., Bournazos A., Datseris I. FDG uptake in axillary lymph nodes after vaccination against pandemic (H1N1) Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1251–1253. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coates E.F., Costner P.J., Nason M.C. Lymph node activation by PET/CT following vaccination with licensed vaccines for human papillomaviruses. Clin Nucl Med. 2017;42:329–334. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shirone N., Shinkai T., Yamane T. Axillary lymph node accumulation on FDG PET/CT after influenza vaccination. Ann Nucl Med. 2012;26:248–252. doi: 10.1007/s12149-011-0568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burger I.A., Husmann L., Hany T.F. Incidence and intensity of F-18 FDG uptake after vaccination with H1N1 vaccine. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:848–853. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182177322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomassen A., Lerberg Nielsen A., Gerke O. Duration of 18F-FDG avidity in lymph nodes after pandemic H1N1v and seasonal influenza vaccination. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:894–898. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1729-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J.E., Kim E.L., Lee D.H., Kim S.W., Suh C., Lee J.S. False-positive hypermetabolic lesions on post-treatment PET-CT after influenza vaccination. Korean J Intern Med. 2011;26:210–212. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2011.26.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams G., Joyce R.M., Parker J.A. False-positive axillary lymph node on FDG-PET/ CT scan resulting from immunization. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31:731–732. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000242693.69039.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayati N., Jesudason S., Berlangieri S.U., Scott A.M. Generalized lymph node activation after influenza vaccination on 18F FDG-PET/CT imaging, an important pitfall in PET interpretation. Asia Ocean J Nucl Med Biol. 2017;5:148–150. doi: 10.22038/aojnmb.2017.8702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehman CD, Lamb LR, D’Alessandro HA. Mitigating the impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccinations on patients undergoing breast imaging examinations: a pragmatic approach. AJR Am J Roentgenol. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Membership communications through SBI Connect Open Forum. Available at: Mail@ConnectedCommunity.org and https://connect.sbi-online.org. Accessed February 23, 2021.

- 24.Grimm L., Destounis, Dogan B. SBI recommendations for the management of axillary lymphadenopathy in patients with recent COVID-19 vaccination: Society of Breast Imaging Patient Care and Delivery Committee; 2021. https://www.sbi-online.org/Portals/0/Position%20Statements/2021/SBI-recommendations-for-managing-axillary-lymphadenopathy-post-COVID-vaccination.pdf Available at:

- 25.D’Orsi C.J., Sickles E.A., Mendelson E.B. American College of Radiology; Reston, Virginia: 2013. ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aberle D.R., Adams A.M., Berg C.D. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Koning H.J., van der Aalst C.M., de Jong P.A. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:503–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Radiology Data Registry 2019 lung cancer screening registry report from the American College of Radiology. https://www.acr.org/Practice-Managemen-Quality-Informatics/Registries/Lung-Cancer-Screening-Registry Available at:

- 29.Chintanapakdee W., Mendoza D.P., Zhang E.W. Detection of extrapulmonary malignancy during lung cancer screening: 5-year analysis at a tertiary hospital. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:1609–1620. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munden R.F., Carter B.W., Chiles C. Managing incidental findings on thoracic CT: Mediastinal and cardiovascular findings. A white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15:1087–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Over 75 million CT scans are performed each year and growing despite radiation concerns. iData Research. August 29, 2018. https://idataresearch.com/over-75-million-ct-scans-are-performed-each-year-and-growing-despite-radiation-concerns/ Available at:

- 32.American Cancer Society Cancer facts & figures 2021. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2021.html Available at:

- 33.NCCN imaging appropriate use criteria. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/imaging/default.aspx Available at:

- 34.Saini K.S., Tagliamento M., Lambertini M. Mortality in patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and pooled analysis of 52 studies. Eur J Cancer. 2020;139:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim clinical considerations for use of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. February 18, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/clinical-considerations.html Available at:

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Moderna COVID-19 vaccine standing orders for administering vaccine to persons 18 years of age and older. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/moderna/downloads/standing-orders.pdf Available at:

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine standing orders for administering vaccine to persons 16 years of age and older. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/downloads/standing-orders.pdf Available at: