Abstract

The Coronaviridae family comprises large enveloped single-stranded RNA viruses. The known human-infecting coronaviruses; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), novel SARS-CoV-2, human coronavirus (HCoV)-NL63, HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43 and HKU1 cause mild to severe respiratory infections. The viral diseases induced by mammalian and avian viruses from Coronaviridae family pose significant economic and public health burdens. Due to increasing reports of viral resistance, co-infections and the emergence of viral epidemics such as COVID-19, available antiviral drugs show low or no efficacy, and the production of new treatments or vaccines are also challenging. Therefore, demand for the development of novel antivirals has considerably increased. In recent years, antiviral peptides have generated increasing interest as they are from natural and computational sources, are highly specific and effective, and possess the broad-spectrum activity with minimum side effects. Here, we have made an effort to compile and review the antiviral peptides with activity against Coronaviridae family viruses. They were divided into different categories according to their action mechanisms, including binding/attachment inhibitors, fusion and entry inhibitors, viral enzyme inhibitors, replication inhibitors and the peptides with direct and indirect effects on the viruses. Reported studies suggest optimism with regard to the design and production of therapeutically promising antiviral drugs. This review aims to summarize data relating to antiviral peptides particularly with respect to their applicability for development as novel treatments.

Keywords: Antiviral peptide, Inhibitory mechanisms, Coronaviridae family

1. Introduction

The Coronaviridae family comprises large enveloped single-stranded RNA viruses with genomes ranging from 25 to 32 kb. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) divided this family into Orthocoronavirinae and Letovirinae sub-families and according to phylogenetic relationships Orthocoronavirinae consists of four genera including Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus [1,2]. The alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses infect mammals and usually cause respiratory disease in humans and gastroenteritis in animals. The gammacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses infect avian species; however, some of them have also been found in mammalian hosts [3,4].

The known human-infecting coronaviruses, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and novel SARS-CoV-2 responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that cause severe lower respiratory tract infections with extra-pulmonary involvements are from betacoronavirus. The other human coronaviruses (HCoV-NL63, HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43 and HKU1) which induce mild to severe respiratory tract illness belong to the alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus genera [2,4].

Furthermore, the viral diseases caused by other members of Coronaviridae family pose significant economic and public health burdens. These viruses include porcine enteric diarrhea virus (PEDV), porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus (PHEV), infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), Mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) and the recently emerged swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS- CoV) [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9]].

Several potential drugs and vaccines against coronavirus infections have been reported in the literature [2,5,10]. However, these approaches are not effective against a broad range of viral infections. Moreover, due to increasing reports of viral resistances, co-infections, and the emergence of viral epidemics such as COVID-19, available antiviral drugs show low or no efficacy against several coronavirus infections and the production of new vaccines is also challenging and time consuming [11]. Therefore, demand for the development of novel antivirals has considerably increased that may serve as supplementary or alternative to the currently used drugs. Employing antimicrobial peptides is an alternative option to circumvent the issues mentioned earlier. The features that suggest them as potent candidates for pharmacological applications are their remarkable structural and functional diversity. The wide range of biological activities of antimicrobial peptides proposes that they could be incorporated in the treatment strategies against bacterial, viral, and fungal infections [[12], [13], [14], [15]]. Antiviral peptides have generated an increasing interest as a promising therapeutic in recent years. They have been obtained from natural, biological, and computational sources and are highly specific and effective in low concentrations and possess broad-spectrum activities with minimum side effects and host toxicity [16,17].

Here, we have made an effort to compile and review the antiviral peptides with activity against the viruses of Coronaviridae family and their mechanisms of action, which may help the researchers to design and produce novel antiviral drugs.

2. Characteristics and mechanisms of action of antiviral peptides

Antiviral peptides affect viruses by inhibiting the essential stages of their life cycle or components such as inhibition of attachment, fusion, host cell entry, intracellular viral replication and transcription, maturation, and viral enzymes. Direct interaction with virus particles and its effect on viral pathogenesis has also been reported by some antiviral peptides [[17], [18], [19]].

2.1. Antiviral peptides against human-infecting coronaviruses

2.1.1. Binding/attachment inhibitor peptides

The interaction of attachment proteins expressed on the virion surface with the host cell receptors is a vital initial step in the viral infections [20]. The viral genome of coronaviruses encodes spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) structural proteins. The S protein has extracellular, transmembrane and intracellular domains, and also, the extracellular domain is divided into two subunits: S1 and S2. The S1 subunit includes the receptor-binding domain (RBD). The RBD comprises the N-terminal domain (NTD) and the C-terminal domain (CTD). SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 bind to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (abundant on the lung and small intestine cells surfaces), and MERS-CoV binds to proteinaceous dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) (expressed on the lung and kidney cells surfaces) by CTD [21,22]. The S protein is an attractive target for the development of antiviral agents against CoVs.

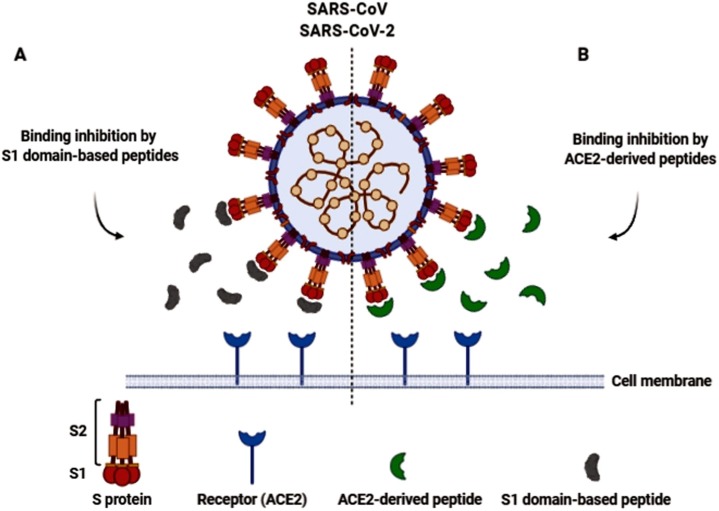

In a study conducted by Zheng et al., anti-SARS-CoV activity of two peptides (P2 and P6) was demonstrated using a cytopathic effect (CPE)-based assay. These peptides were designed and synthesized based on the variations of the S1 domain. They effectively protected cells from the CPEs and reduced viral titer compared to the untreated controls. Significant synergistic antiviral effects were also detected in the combination of two peptides. They suggested that P2 was not a competitive peptide for the ACE2 receptor binding but may hamper conformation changes of the binding site, and P6 binds to the S protein and interferes with the virus-cell interactions [23] (Fig. 1 A). In the other research, ACE2-derived peptides (peptides representing critical regions of ACE2) could block ACE2-S protein interaction and inhibit virus binding to the host cell. The evaluated peptides (P4, P5 and P6) exhibited a notable antiviral activity with the relative low 50 % inhibitory concentrations (IC50) [24]. The attachment blocker small peptides (SP-4, SP-8 and SP-10) were also synthesized in a previous study based on S protein's receptor-binding regions (Molecular weight ∼ 1.3–1.4 KDa). Their efficient inhibitory activity against S protein binding to the ACE2 was detected using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method in Vero E6 cells [25].

Fig. 1.

Model of SARS-CoV/ SARS-CoV-2 binding inhibition by S1 domain-based inhibitor peptides (A) and ACE2-derived inhibitor peptides (B).

Moreover, Chang et al. indicated that two synthetic peptides, GA91 and GA101 (corresponding to SARS-CoV Spike protein) block the binding of the SARS-CoV S protein to the host cells, using Vero E6 cells in adhesion assay [26]. In a different study, a hexapeptide, which was derived from RBD of the S protein, showed antiviral activity against SARS-CoV and HCoV-NL63. This peptide blocks the binding sites essential for the initial viral attachment to the respective receptor (Fig. 1A) and effectually inhibits CoVs replication in cell culture [27].

In the recent in-silico studies, the inhibitor peptides targeting the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and ACE2 were designed using computational approaches [28,29]. Baig and colleagues have presented an ACE2-based peptide (18 aa peptide) that could block the viral attachment [28]. Furthermore, the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 was targeted by an inhibitor protein (ΔABP-D25Y) in Jaiswal et al., study. This protein includes two α-helical peptides which homologues to the ACE2 and also, its attachment to S protein is competitive [29] (Fig. 1B). Recent investigations showed that there are several potential heparin-binding sites located within the S1 domain of SARS-CoV-2. Heparin-binding peptides (HBPs) are capable of stopping SARS-CoV-2 infection. The interaction between HBPs and the S1 protein of SARS-CoV-2 was also described [30]. Another antimicrobial peptide with anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity is human defensin 5 (HD5). This alpha-defensin is secreted by intestinal Paneth cells and by neutrophils. It has high affinity to ACE2 and dramatically protects host cells from the adherence of the virus. HD5 is also capable of attaching SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein and affects its efficiency [31,32].

The characteristics of the antiviral peptides with binding inhibitory activity against human-infecting coronaviruses are expressed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

The characteristics of the peptides with binding inhibitory activity against human-infecting coronaviruses.

| Peptide name | Sequence | Peptide source | Target virus | Inhibitory concentration | Cell line | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2 | PTTFMLKYDENGTITDAVDC | S1 subunit of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 112.5 ± 26.3 μg/mL (IC50) | Fetal rhesus kidney (FRhK-4) cells | [23] |

| P6 | YQDVNCTDVSTAIHADQLTP | S1 subunit of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 113.0 ± 27.6 μg/mL (IC50) | Fetal rhesus kidney (FRhK-4) cells | [23] |

| P4 | EEQAKTFLDKFNHEAEDLFYQSS | ACE2 | SARS-CoV | 50 μM (IC50) | HeLa cells | [24] |

| P5 | EEQAKTFLDKFNHEAEDLFYQSSLASWNYNTNITEE | ACE2 | SARS-CoV | 6 μM (IC50) | HeLa cells | [24] |

| P6 | EEQAKTFLDKFNHEAEDLFYQSSGLGKGDFR | ACE2 | SARS-CoV | 0.1 μM (IC50) | HeLa cells | [24] |

| SP-4 | GFLYVYKGYQPI | S protein of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 4.3 ± 2.18 nmol (IC50) | – | [25] |

| SP-8 | FYTTTGIGYQPY | S protein of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 6.99 ± 0.71 nmol (IC50) | – | [25] |

| SP-10 | STSQKSIVAYTM | S protein of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 1.88 ± 0.52 nmol (IC50) | Vero E6 cells | [25] |

| GA91 | – | S protein of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | – | Vero E6 cells | [26] |

| GA101 | – | S protein of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | – | Vero E6 cells | [26] |

| BD-11b | YKYRYL | S protein of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 14 mM (IC90) | Vero E6 cells | [27] |

| BD-11b | YKYRYL | S protein | HCoV- NL63 | 7 mM (IC90) | CaCo2 cells | [27] |

| 18 aa peptide | FLDKFNHEAEDLFYQSSL | ACE2 | SARS-CoV-2 | – | – | [28] |

| ΔABP-D25Y | GSHMGDAQDKLKYLVKQLERALRELKKSLDELERSLEELEKNPSEDALVENNRLNVENNKIIVEVLRIILELAKASAKLA | ACE2 | SARS-CoV-2 | – | – | [29] |

| P5 + 14 | GGGYSKAQKAQAKQAKQAQKAQKAQAKQAKQAQKAQKAQAKQAKQ | S1 subunit of SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 | – | – | [30] |

| Human Defensin-5 | – | Intestinal Paneth cells and neutrophils | SARS-CoV-2 | 10 μg/mL | Caco-2 cells | [31] |

2.1.2. Fusion and entry inhibitor peptides

As mentioned above, the extracellular domain of S protein contains two subunits; S1 and S2. The S2 mediates the membrane fusion. It contains various motifs: fusion peptide (FP), heptad repeat 1 (HR1) and HR2 regions, transmembrane (TM) domain and the cytoplasmic tail. FP is the functional fusogenic component and triggers the fusion event through insertion into the cell membrane. The HR1 and HR2 form a six-helix bundle or fusion core, and this conformational rearrangement is essential for the viral fusion and entry. There are two viral entry pathways for CoVs: plasma membrane (early) pathway and endosomal (late) pathway. The protease availability determines the route of entry. In the presence of exogenous or host membrane-bound proteases, most notably the transmembrane protease/serine sub-family member 2 (TMPRSS2), the virus can fuse via the plasma membrane pathway. TMPRSS2, cleaves the S protein at the S2’ position which is located in upstream of the FP and activates plasma membrane fusion. Otherwise, the virus can fuse via an endosomal membrane pathway (clathrin- and non-clathrin-mediated endocytosis). Following endocytosis, the activated cysteine protease cathepsin L can cleave the S2’ site in acidic conditions and trigger the subsequent fusion steps and CoVs genome releasing [21,22].

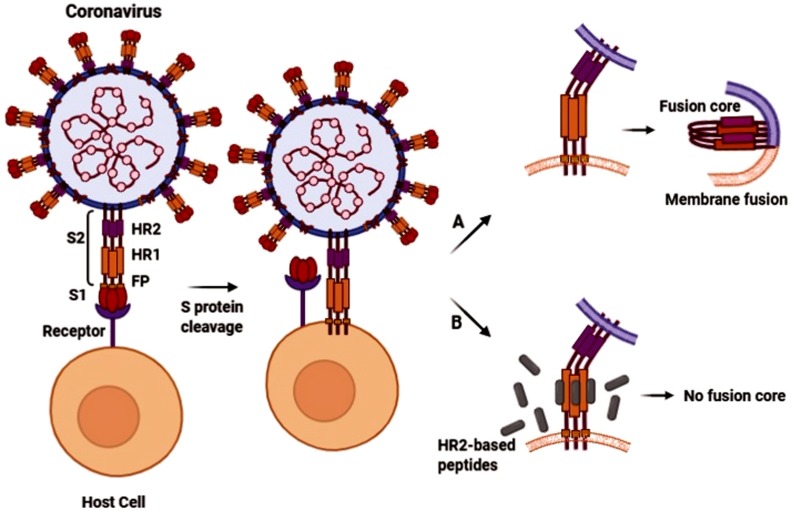

In a study conducted by Liu et al., the anti-SARS-CoV activity of the synthesized peptides based on HR1 and HR2 regions of S protein was investigated. One peptide derived from HR2 (CP-1) had inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV by binding to the HR1 and interfering with the conformational rearrangement (six-helix bundle formation) viral fusion. A HR1- derived peptide (NP-1) showed a marginal antiviral activity [33]. The inhibitory activity against membrane fusion and viral entry has also been described by a peptide derived from the SARS-CoV S2 protein HR segments in another research [34]. Moreover, Zheng and colleagues synthesized the peptides based on the sequence of SARS-CoV S2 domain. Significant antiviral effects were observed for two peptides (P8 and P10) through binding to the S2 protein and preventing virion–cell membrane fusion. They significantly protected cells from CPEs and reduced viral titer in the culture media. The peptide P8 had the highest antiviral potency and no virus was detected after P8 treatment. Furthermore, peptide combinations significantly improved their antiviral effects [23]. In the Sainz Jr et al., study, the peptides' ability analogous to the S2 subunit to inhibit SARS-CoV plaque formation has also been described [35]. Anti-SARS-CoV properties of HR-based antiviral peptides have been reported in more researches [[36], [37], [38]]. Fig. 2 shows the anti-fusion activity of the HR2-based peptides model against coronaviruses.

Fig. 2.

Schematic presentation of anti-fusion activity of HR2-based peptides against coronaviruses. A) Fusion core (six-helix bundle) formation through HR1 and HR2 rearrangement and thus membrane fusion. B) Blocking fusion core formation and membrane fusion by HR2-based peptides.

Although, activities of various S2 domain-based peptides against SARS-CoV were mentioned from several studies, the antiviral peptides with different origin have been characterized in the literature. The Griffithsin (GRFT) as an antiviral protein was originally obtained from a red alga. It can bind to the SARS-CoV spike glycoprotein specifically and inhibits viral entry. It prevents SARS-CoV infection both in vitro and in vivo. GRFT’s activity against other human-infecting coronaviruses was also demonstrated [39].

Furthermore, a membrane fusion blocker peptide with basic amino acids in its composition was introduced by Zhao et al., in 2016. This mouse β-defensin-4 derived peptide (P9) efficiently attached to the SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV glycoproteins and entered the host cells with the viruses through endocytosis. P9 prevents endosomal acidification and thus, inhibits the subsequent fusion steps [40]. The inhibitory model of such peptides against coronaviruses is shown in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

Model of anti-fusion activity of alkaline peptides (peptides with basic amino acids) such as P9 and P9R against coronaviruses. This model depicts: A) Binding the virus with its receptor and endocytosis induction (1); Endocytosis (2); Endosome acidification, cathepsin L activation, fusion and viral genome release (3). B) Receptor binding and endocytosis induction in the presence of alkaline peptides (1); Endocytosis with attached alkaline peptides (2); Inhibition of endosome acidification, no cathepsin L activation and no fusion (3).

Several researches have also been performed regarding antiviral activity of HR regions-based peptides against MERS-CoV. In the Lu et al., study, a MESR-CoV HR2 analogous peptide (HR2P) was synthesized and its antiviral activity was investigated against this virus. The peptide could inhibit MERS-CoV fusion through interaction with the viral HR1 domain and heterologous six-helix bundle formation [41]. A similar result was presented in the study by Channappanavar et al. [42]. A fusion inhibitor named MERS-five-helix bundle (MERS-5HB) was synthetized by Sun et al. MERS-5HB was derived from the MERS six-helix bundle and consisted of three copies of HR1 and two copies of HR2. Lack of one HR2 in 5HB led to its interaction with a native HR2 of the MERS-CoV and the fusion step interruption [43]. As mentioned above, six-helix bundle (hexameric structure) formation by HR1 and HR2 is necessary for viral fusion and entry. Wang et al., have designed the hydrocarbon-stapled peptide and lipopeptide with a hydrocarbon tail in the two separate studies that could effectively block MERS-CoV formation hexameric structure [44,45]. The MERS-CoV fusion inhibitory peptides derived from HR2 domain of HKU4 (bat coronavirus) have also been reported. The HKU4-HR2Ps binds to HR1 of MERS-CoV with high stability and blocks the fusion process [46] (Fig. 2). Recently, a gold nanorod-based HR1 peptide (PIH-AuNRs) was proposed as MERS-CoV fusion inhibitor. The HR1 peptide inhibitor (PIH) derived from viral HR2 region was conjugated by potential biocompatible and site-specific carriers (AuNRs). This complex could completely inhibit MERS-CoV fusion [47].

In an in-silico study conducted by Ling et al., an antiviral peptide targeting SARS-CoV-2 fusion was described. They predicted the HR1 and HR2 regions in S protein of SARS-CoV-2 using sequence alignment and simulated forming of the fusion core. Then, they designed HR2-baseed peptide that can competitively bind with HR1 to inhibit viral fusion core forming [48]. Furthermore, Xia and colleagues utilized a lipopeptide (EK1C4) derived from a pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor, EK1 (targeting the HR1 domain), against SARS-CoV-2. This lipopeptide displayed potent inhibitory activity against the virus [49]. More lipopeptides with anti-fusion activity against SARS-CoV-2 were reported in the recent studies. A SARS-CoV-2 HR2 sequence-based lipopeptide (IPB02) was highly potent fusion inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV [50] (Fig. 2). In another study, similar peptide activity corresponding to the C-terminal HR domain of SARS-CoV-2 conjugated by tetra-ethylene glycol-cholesterol was demonstrated against SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV. The spread of SARS-CoV-2 in human airway epithelial (HAE) cultures was also blocked using this lipopeptide [51]. One derivative of aforementioned lipopeptide ([SARSHRC-PEG4]2-chol) was able to block entry of SARS-CoV-2 in the host cells and the cells over-expressing the TMPRSS2 protease. Moreover, [SARSHRC-PEG4]2-chol intranasal administration to ferrets, completely protected the animals from SARS-CoV-2 infection [52].

Zhao et al., studied the alkaline peptide P9R (a defensin-like peptide) as an antiviral activity against pH-dependent viruses such as SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV that require endosomal acidification for their infection development. P9R is the modified form of P9 (weakly positively charged amino acids substitution), which was mentioned above, and its antiviral mechanism was similar to P9 [53] (Fig. 3). Anti-SARS-CoV-2 fusion activity of the peptides derived from food proteins such as lactoferrin, have also been proposed recently through inhibition of cathepsin L [54].

The HR-based antiviral peptides against other human-infecting coronaviruses were suggested in the previous studies. The fusion inhibitor peptides targeting HCoV-229E via interaction with its six-helix bundle were characterized in a research. The peptides could efficiently inhibit CPEs of HCoV-229E infection in the host cells [55]. Meanwhile, the mentioned above pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor (EK1) which was derived from HR2 domain of HCoV-OC43, possessed broad fusion inhibitory property against multiple human coronaviruses. This peptide and cholesterol-attached form exhibited effective inhibitory activities against HCoV-OC43, MERS-CoV, HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 [49,56] (Fig. 2). The characteristics of antiviral peptides with fusion or entry inhibitory activity against human-infecting coronaviruses are illustrated in Table 2 .

Table 2.

The characteristics of the peptides with fusion or entry inhibitory activity against human-infecting coronaviruses.

| Peptide name | Sequence | Peptide source | Target virus | Effective / inhibitory concentration | Cell line / animal model | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP-1 | GINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQELGKYE | HR2 region of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 19 μmol/L (IC50) | Vero E6 cells | [33] |

| NP-1 | GVTQNVLYENQKQIANQFNKAISQIQESLTTTSTALGKLQ | HR1 region of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 50 μmol/L (IC50) | Vero E6 cells | [33] |

| – | SGINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQEL | HR segment of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | – | – | [34] |

| P8 | QYGSFCTQLNRALSGIAAEQ | S2 subunit of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 24.9 ± 6.2 μg/mL (IC90) | Fetal rhesus kidney (FRhK-4) cells | [23] |

| P10 | IQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLI | HR2 region of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 73.5 ± 15.7 μg/mL (IC90) | Fetal rhesus kidney (FRhK-4) cells | [23] |

| SARSWW-III | GYHLMSFPQAAPHGVVFLHVTW | S2 subunit of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | ∼ 2 μM (IC50) | Vero E6 cells | [35] |

| SARSWW-IV | GVFVFNGTSWFITQRNFFS | S2 subunit of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | ∼ 2 μM (IC50) | Vero E6 cells | [35] |

| HR1-1 | NGIGVTQNVLYENQKQIANQFNKAISQIQESLTTTSTA | HR1 region of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 3.68 μM (EC50) | Vero E6 cells | [36] |

| HR2-18 | IQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQELGK | HR2 region of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 5.22 μM (EC50) | Vero E6 cells | [36] |

| HR1-a | YENQKQIANQFNKAISQIQESLTTTSTA | S2 subunit of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 1.61 μM (EC50) | Vero E6 cells | [37] |

| GST-removed-HR2 | DVDLGDISGINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQEL | S2 subunit of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 2.18 μM (EC50) | Vero E6 cells | [37] |

| HR2 | ISGINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQEL | S2 subunit of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 0.34 μM (EC50) | Vero E6 cells | [37] |

| SR9 | ISGINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQEL | HR2 region of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | <100 nM (EC50) | Vero E6 cells | [38] |

| GRFT | SLTHRKFGGSGGSPFSGLSSIAVRSGSYLDAIIDGVHHGGSGGNLSPTFTFGSGEYISNMTIRSGDYIDNISFETNMGRRFGPYGGSGGSANTLSNVKVIQINGSAGDYLDSLDIYYEQY | Griffithsia sp. | SARS-CoV | >100 μg/mL (IC50) | Vero 76 cells / BALB/c mice | [39] |

| P9 | NGAICWGPCPTAFRQIGNCGHFKVRCCKIR | mouse β-defensin-4 | SARS and MERS-CoVs | ∼ 5 μg/mL (IC50) | FRhK-4 and Vero-E6 cells / BALB/c mice | [40] |

| 25 μg/mL (IC90) | ||||||

| HR2P | SLTQINTTLLDLTYEMLSLQQVVKALNESYIDLKEL | HR2 region of MERS-CoV | MERS-CoV | 0.6 μM (IC50) | Calu-3 and Vero cells | [41] |

| HR2P-M2 | SLTQINTTLLDLEYEMKKLEEVVKKLEESYIDLKEL | HR2 region of MERS-CoV | MERS-CoV | 0.55 μmol/L (IC50) | Vero 81 cells | [42] |

| 5HB | HR1-SGGRGG-HR2-GGSGGSGG-HR1-SGGRGG-HR2-GGSGGSGG-HR1 | S2 subunit of MERS-CoV | MERS-CoV | 1 μM (IC50) | Huh-7 cells | [43] |

| P21S10 | LDLTYEMLSLQQVV KLNEY | S2 subunit of MERS-CoV | MERS-CoV | 0.97–1.58 μM (EC50) | Huh-7 and Calu-3 cells | [44] |

| IIQ | IEEIQKKIEEIQKKIEEIQKKIEEIQKKIEEIQKK-β-alanine-K | – | MERS-CoV | 0.13 μM (EC50) | Huh-7 cells | [45] |

| HKU4-HR2P2 | EISKINTTLLDLSDEMAMLQQEVVKQLNDSYIDLKEL | HR2 domain of bat coronavirus HKU4 | MERS-CoV | 0.34 μM (IC50) | Huh-7 cells | [46] |

| HKU4-HR2P3 | LDLSDEMAMLQQEVVKQLNDSYIDLKELGNYTYYNKW | HR2 domain of bat coronavirus HKU4 | MERS-CoV | 0.48 μM (IC50) | Huh-7 cells | [46] |

| PIH-AuNR | CGGGGGSLTEINTELLDLEYEMKKLEEVVKKLEESYIDLKEL-AuNR | HR2 domain of MERS-CoV | MERS-CoV | 0.117 μM (IC90) | Huh-7 cells | [47] |

| HR2-anti-P | DISGINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQEL | HR2 domain of SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 | – | – | [48] |

| EK1C4 | SLDQINVTFLDLEYEMKKLEEAIKKLEESYIDLKEL-PEG4-Chol | HR2 domain of HCoV-OC43 | SARS-CoV-2 | 36.5 nM (IC50) | Vero E6 cells | [49] |

| IPB02 | ISGINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQELK-Chol | HR2 domain of SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV | 0.08 and 0.251 μM (IC50) | 293 T cells | [50] |

| – | DISGINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQEL-GSGSGC-TEG-Chol | C-terminal HR domain of SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV | ∼ 6 and ∼3 nM (IC50) | Vero E6 and human derived tracheo/bronchial epithelial cells | [51] |

| [SARSHRC-PEG4]2-Chol | [DISGINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQEL-PEG4]2-Chol | C-terminal HR domain of SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 | ∼ 300 and ∼ 5 nM (IC50) | Vero E6 and Vero E6 cells overexpressing the protease TMPRSS2 / Ferrets | [52] |

| P9R | NGAICWGPCPTAFRQIGNCGRFRVRCCRIR | Mouse β-defensin-4 like peptide | SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV | 0.9, 2.2 and 4.2 μg/mL (IC50) | Vero E6 cells | [53] |

| GRFT | SLTHRKFGGSGGSPFSGLSSIAVRSGSYLDAIIDGVHHGGSGGNLSPTFTFGSGEYISNMTIRSGDYIDNISFETNMGRRFGPYGGSGGSANTLSNVKVIQINGSAGDYLDSLDIYYEQY | Griffithsia sp. | HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 | 52, >10 and 10 μg/mL (IC50) | HCT-8, MRC-5, LLC-MK2 cells | [39] |

| 229E-HR1P | AASFNKAMTNIVDAFTGVNDAITQTSQALQTVATALNKIQDVVNQQGNSLNHLTSQ | S2 subunit of HCoV-229E | HCoV-229E | 13.2 μM (IC50) | Huh-7 and A549 cells | [55] |

| 229E-HR2P | VVEQYNQTILNLTSEISTLENKSAELNYTVQKLQTLIDNINSTLVDLKWL | S2 subunit of HCoV-229E | HCoV-229E | 1.96 μM (IC50) | Huh-7 and A549 cells / Balb/c mice | [55] |

| EK1 | SLDQINVTFLDLEYEMKKLEEAIKKLEESYIDLKEL | HR2 domain of HCoV-OC43 | HCoV-OC43, MERS-CoV, HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 | 0.62, 0.11, 0.69 and 0.48 μM (IC50) | HCT-8, Calu-3, A549 and LLC-MK2 cells / Balb/c mice | [56] |

| EK1C4 | SLDQINVTFLDLEYEMKKLEEAIKKLEESYIDLKEL-PEG4-Chol | HR2 domain of HCoV-OC43 | MERS-CoV, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 | 4.2, 24.8, 101.5 and 187.6 nM (IC50) | RD, Huh-7 and LLC-MK2 cells / Mice | [49] |

PEG, poly-ethylene glycol; Chol, cholesterol; TEG, tetra-ethylene glycol.

2.1.3. Viral enzymes inhibitor peptides

The coronavirus enzymes' pivotal roles, including proteases, helicases, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), and methyltransferase, have been well characterized in the viral life cycle. Coronaviruses genome contains at least 6 open reading frames (ORFs). The ORF1ab encodes the overlapping polyproteins which are cleaved into non-structural proteins (nsps) by the main protease (Mpro or 3CLpro) and the papain-like protease (PLpro) [57]. Due to these cysteine proteases' critical role in viral gene expression and replication, they are favorable targets for the antiviral drug design.

In the study conducted by Gan et al., the designed octapeptide inhibited the SARS-CoV Mpro and blocked replication of the virus [58]. Similarly, the synthetized dipeptides (6a and EP128533) and tetrapeptide inhibited several CoVs by inhibiting their Mpro [[59], [60], [61]]. In the previous studies, SARS-CoV Mpro inhibitory activities of the peptide-based compounds (tetrapeptide, pentapeptides and octapeptides) were also proposed without biological experiments [[62], [63], [64]]. A recent study indicated that, in-silico hydrolysis of marine fish proteins, gastrointestinal enzymes generated active peptides. Some of them were identified as high-affinity oligopeptides binder to the Mpro of SARS-CoV-2. According to their results, the identified oligopeptides could be used as potential SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor drugs [65].

In addition, blocking other enzyme of SARS-CoV (Methyltransferase) was demonstrated previously by the synthesized peptides. The nsp16 acts as a methyltransferase and plays an essential role in the life cycle of coronaviruses. The designed peptides could markedly inhibit the activity of methyltransferase and thus viral replication [66]. Table 3 shows the characteristics of antiviral peptides with potential inhibitory activity against coronaviruses enzymes.

Table 3.

The characteristics of the peptides with potential inhibitory activity against coronaviruses enzymes.

| Peptide name | Sequence | Peptide source | Target virus | Effective / inhibitory concentration | Cell line | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octapeptide | AVLQSGFR | Structure of SARS-CoV Mpro | SARS-CoV | 0.027 μg/mL (EC50) | Vero cells | [58] |

| 6a | LQQ-fmk | Cleavage site of SARS-CoV Mpro | SARS-CoV | 2.5 μM (EC50) | Vero cells | [59] |

| EP128533 | – | – | SARS-CoV | 0.56−1.4 μg/mL (EC50) | Vero-76 cells | [60] |

| Protected tetrapeptide | Cbz-AVLQ | Cleavage site of the main proteases | SARS-CoV, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1 and IBV | 1.3–4.6 μM (IC50) | – | [61] |

| Pentapeptide aldehydes | ESTLQ, NSFSQ, DSFDQ and NSTSQ | Analyses of the SARS-CoV Mpro | SARS-CoV | – | – | [63] |

| Tetrapeptide aldehyde | TVFH | Analyses of the SARS-CoV 3CL protease | SARS-CoV | 98 nM (IC50) | – | [64] |

| Oligopeptides | ITTIM, TVPIY, ICIY, PASQF, IITAM, TIIF, AIPAW, IVPIL, PVIDL, TVPIY, ICIY, PISQF, EQIVY, VISAW and PESW | Marine fish proteins | SARS-CoV-2 | – | – | [65] |

| K 12 | GGASCCLYCRCH | Sequence of nsp 10 of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 160 μM (IC50) | – | [66] |

| K 29 | FGGASCCLYCRCHIDHPNPKGFCDLKGKY | Sequence of nsp 10 of SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV | 160 μM (IC50) | – | [66] |

Fmk, fluoromethyl ketones; Cbz, carboxybenzyl.

2.1.4. Viral replication inhibitor peptides

In the study performed by Lo et al., a synthesized peptide could inhibit replication of HCoV-229E in the host cells, significantly through the interference of the oligomerization of the viral nucleocapsid protein [67]. The application of such a strategy may assist the design and development of antiviral drugs against other human-infecting coronaviruses. Table 4 shows the characteristics of the viral replication inhibitor peptides.

Table 4.

The characteristics of the viral replication inhibitor peptides.

| Peptide name | Sequence | Peptide source | Target virus | Effective / inhibitory concentration | Cell line / animal model | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-terminal tail peptide | – | Nucleocapsid protein of HCoV-229E | HCoV-229E | 300 μM | A549 cells | [67] |

| APB-13 | ILPWKWPWWPWRR-NH2 | Cattle | TGEV | 62.5 μg/mL | ST cells / Piglets | [88] |

| viperin | – | Porcine antiviral protein | PEDV | – | IPEC-J2 cells | [89] |

2.1.5. Direct interaction of antiviral peptides with virus particles

The virucidal activity of a confirmed antimicrobial peptide against SARS-CoV was reported in the Li et al., study. The infectivity of virus decreased significantly via direct interaction of the peptide (mucroporin-M1) with the virus envelope [68]. The characteristics of mucroporin-M1 are shown in Table 5 .

Table 5.

The characteristics of the peptides with direct effect on virus particles.

2.1.6. Effects of human antimicrobial peptides against coronaviruses pathogenesis

Indirect effects of human beta-defensin 2 (HBD 2) (an antimicrobial peptide produced by epithelial cells) against MERS-CoV were reported in the previous studies. HBD 2 enhanced primary antiviral innate immunity and effective adaptive immune responses [69,70]. Human cathelicidin (LL-37) also reduces the pathology of COVID-19 by affecting regulatory T cells. The probable role of LL-37 in the down-regulation of interleukin-17, which is involved in thrombosis and acute respiratory distress syndrome, was reported recently [71].

2.2. Antiviral peptides against mammalian and avian viral strains

2.2.1. Binding/attachment inhibitor peptides

The antiviral peptides with binding inhibitory activities against mammalian and avian viral strains have also been reported. The TGEV is a porcine coronavirus and the causative agent of transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE). TGE is a highly contagious enteric disease of swine with up to 100 % mortality in suckling piglets and causes economic losses. The S protein of the virus interacts with its cellular receptor, porcine aminopeptidase N (pAPN). Also, APN is a cellular receptor for HCoV-229E and FIPV [72]. Phages displaying peptide sequences with protective effects against TGEV infection, have been described in the literature. The findings of Ren et al., study showed three chemically synthesized peptides (F, H and S) that had sequence homologies (same motifs identified in the S protein of TGEV) were able to inhibit TGEV infection through competition with binding the pAPN [72]. Similarly, an antiviral peptide's potential inhibitory effect was observed using a phage bearing the peptide with affinity to pAPN [73]. Furthermore, the inhibitory activity of a membrane (M) protein-derived peptide was demonstrated in the other study. Peptide TGEV-M7 was able to significantly reduce the virus's ability to infect host cells [74].

Cao et al., indicated the antiviral activity of two peptides (L and W) against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV). The PEDV is another swine pathogen that causes severe diarrhea and dehydration. These peptides share a consensus motif with S1 protein of PEDV and inhibit the binding of the virus to the host cells [75].

FIPV is a type of feline coronavirus (FCoV) and belongs to the alphacoronaviruses. It can cause lethal disease in cats due to multiple organs involvement. The S1 domain of FIPV S protein also contains the RBD. Doki et al., synthesized peptides based on the S1 domain sequence and investigated their inhibitory effects. Two peptides (I-S1-9 and I-S1-16) inhibited the binding and infectivity of FIPV significantly. Moreover, significant reduction of viral adsorption to cells was observed using peptide I-S1-9 [76].

IBV that belongs to gammacoronavirus, is the etiologic agent of complex and highly contagious respiratory disease in chickens which remains an economic problem. Bo et al., showed that a phage-displayed peptide blocks binding the IBV S protein and inhibits virus infectivity and CPE occurrence in HeLa cells [77]. The other studies indicated that swine intestine antimicrobial peptide (SIAMP) inhibits IBV replication and decreases tissue injury caused by the virus. Interaction of SIAMP with IBV and blocking the virus binding to the embryos' epithelial cells were reported as the probable inhibitory mechanisms of the peptide [78]. Table 6 shows the characteristics of the peptides inhibiting the mammalian and avian coronaviruses binding.

Table 6.

The characteristics of binding inhibitor peptides of the mammalian and avian viruses.

| Peptide name | Sequence | Peptide source | Target virus | Effective concentration | Cell line | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | FKPSSPPSITLW | S protein of TGEV | TGEV | 20 μg/mL | Swine testis (ST) cells | [72] |

| H | HVTTTFAPPPPR | S protein of TGEV | TGEV | 20 μg/mL | ST cells | [72] |

| S | SVVPSKATWGFA | S protein of TGEV | TGEV | 20 μg/mL | ST cells | [72] |

| – | HDAISWTHYHPW | pAPN | TGEV | – | ST cells | [73] |

| TGEV-M7 | HALTPIKYIPPG | M protein of TGEV | TGEV | 62.5 μg/mL | ST cells | [74] |

| L | LMQINPTYYQIM | S1 protein of PEDV | PEDV | 50 μg/mL | VeroE6 cells | [75] |

| W | WSFNPSTYTIAG | S1 protein of PEDV | PEDV | 50 μg/mL | VeroE6 cells | [75] |

| I-S1-9 | YGFWTIAYTNYTDVMVDVNG | S1 protein of FIPV | FIPV | 100 μM | Felis catus whole fetus-4 (fcwf-4) cells | [76] |

| I-S1-16 | YHWMNVTLHVVLNDTEKKYD | S1 protein of FIPV | FIPV | 100 μM | fcwf-4 cells | [76] |

| Peptide 1 | GSHHRHVHSPFV | – | IBV | 8.3 μg/mL | Hela cells | [77] |

| SIAMP | – | Swine intestine | IBV | 100 μg/mL | Chick embryos | [78] |

2.2.2. Fusion and entry inhibitor peptides

The fusion or entry blocker peptides against other viruses from Coronaviridae family have been investigated in the literature. Wang et al., indicated that surfactin can effectively inhibit TGEV from entering the host cells [79]. Surfactin is a cyclic lipopeptide secreted by Bacillus subtilis, affects both the viruses and the cells as a membrane fusion inhibitor [79,80]. Likewise, it could inhibit the fusion between the TGEV envelope and the host cell membrane in another study. Surfactin inhibited the replication of TGEV and PEDV completely, and its oral administration also protected piglets from PEDV infection [80]. In another study, anti-PEDV properties of synthetic surfactin analogues were investigated. The SLP5 as a linear lipopeptide had lower cytotoxicity and similar antiviral activity, compared to the surfactin [81]. The PEDV entry was also blocked by a phage-displayed peptide through binding to the S protein, in Meng et al., study [82]. Anti-fusion and entry activities of S2 domain-based peptides against PEDV, FIPV, MHV and IBV have been described in the previous researches [35,[83], [84], [85], [86]]. Moreover, the IBV infection in the host cells was inhibited by an antiviral peptide (As1) obtained from a medicinal plant. As1 binds to fusion and S protein of the virus and interferes with their function during IBV entry [87]. The characteristics of antiviral peptides with fusion or entry inhibitory activity against mammalian and avian viral strains are shown in Table 7 .

Table 7.

The characteristics of the peptides with fusion or entry inhibitory activity against mammalian and avian viral strains.

| Peptide name | Sequence | Peptide source | Target virus | Effective / inhibitory concentration | Cell line / animal model | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surfactin | – | Bacillus subtilis | TGEV | 0.002 mg/mL | Intestinal porcine epithelial cells (IPEC-J2) | [79] |

| Surfactin | – | Bacillus subtilis | TGEV and PEDV | 15−50 μg/mL | ST cells/ Piglet | [80] |

| SLP 5 | Palmityl-EVLDL | Surfactin | PEDV | 16.5 ± 0.6 μg/mL (EC50) | Vero cells | [81] |

| HR2M, HR2L and HR2P | – | HR2 domain of PEDV | PEDV | 4.97, 2.96 and 1.11 μM (IC50) | Huh-7 cells | [83] |

| H | HVTTTFAPPPPR | – | PEDV | 1 μg/mL (EC50) | Vero cells | [82] |

| FP4 | FNATYLNLTGEIDDLEFRSEKLHNTTVELAILIDNINNTLVNL | HR2 domain of FIPV | FIPV | 1.8 μM (IC50) | Fcwf-4 cells | [84] |

| FP5 | FNATYLNLTGEIDDLEFRSEKLHNTTVELAILIDNINNTLVNL EWLNRIE | HR2 domain of FIPV | FIPV | 1.33 μM (IC50) | Fcwf-4 cells | [84] |

| MHVWW-IV | GYFVQDDGEWKFTGSSYYY | S2 subunit of MHV | MHV | 5 μM (IC50) | L2 cells | [35] |

| HR2 | SLSLDFEKLNVTLLDLTYEMNRIQDAIKKLNESYINLKE | HR2 region of MHV | MHV | 50 μM (IC90) | LR7 cells | [86] |

| NOVEL-1 | NASDMEIKKVNKKIEEYIKKIEEVEKKLEEVNKK | HR2 domain of NDV and IBV | IBV | ∼5 μM (IC90) | Chicken embryo fibroblast (CEFs) cells | [85] |

| NOVEL-2 | VNKKIEEIDKKIEELNKKLEELEKKLEEVNKK | HR2 domain of NDV and IBV | IBV | ∼5 μM (IC90) | CEFs cells | [35] |

| Alstotide As1 | CRPYGYRCDGVINQCCDPYHCTPPLIGICL | Alstonia scholaris plant | IBV | ∼100 μM | Vero cells | [87] |

2.2.3. Viral replication inhibitor peptides

In a recent study by Liang et al., indicated in vivo and in vitro anti-TGEV activities of Bovine antimicrobial peptide-13 (APB-13). The peptide had notable inhibitory effect on the expression of nucleocapsid protein of TGEV. Furthermore, viral shedding of animal rectum reduced significantly after treatment by APB-13 [88].

Wu et al., reported that the PEDV proliferation was regulated using an antiviral protein (viperin). The interaction of viperin with the N protein of PEDV led to interfering with viral replication or assembly [89]. Table 4 shows the characteristics of the viral replication inhibitor peptides.

2.2.4. Direct interaction of antiviral peptides with virus particles

The multiplication of PEDV was inhibited significantly by a cationic amphibian antimicrobial peptide in the host cells. The ability of Caerin1.1 to disrupt the integrity of the virus particles was mentioned as its inhibitory mechanism [90]. The characteristics of Caerin1.1 are shown in Table 5.

3. Conclusion

The emergence or re-emergence of Coronaviridae family viruses and enhanced cross-species dissemination due to potential viral mutations are still real threats to the worldwide population. Currently, there is no specific treatment for the majority of infections that caused by such viruses. This study was the first review regarding antiviral peptides with activity against all studied viruses from Coronaviridae family. However, several peptides were found with different antiviral mechanisms. This review mainly aimed to summarize data regarding the peptides that can be applicable and provide relevant information to develop novel treatments. Our study suggests that antiviral peptides are effective therapeutic options for these pathogens. The studies regarding fusion/entry inhibitors (notably HR-based) were more than the others and the HR2-based peptides possessed the most promising activity against investigated coronaviruses. The SR9 and PIH-AuNR were the most effective antiviral peptides against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, respectively. As mentioned in the text, the permeability and effectiveness of the peptides conjugated by the fatty acids (lipopeptides) were more than the pure peptides. For SARS-CoV-2, a lipopeptide (EK1C4) derived from a pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor (EK1) displayed significant inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 in Vero E6 cells. EK1C4 also inhibited other coronaviruses including MERS-CoV, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 in cell culture and mice. The spread of SARS-CoV-2 in human airway epithelial (HAE) cultures was also blocked using the peptide corresponding to C-terminal HR domain of SARS-CoV-2 conjugated by tetra-ethylene glycol-cholesterol. A derivative of this lipopeptide ([SARSHRC-PEG4]2-chol) was able to block the entry of SARS-CoV-2 in the Vero E6 cells. Its intranasal administration to ferrets completely protected the animals from SARS-CoV-2 infection. The antiviral activity and potency of antiviral peptides could be improved by combination with other peptides having different mechanisms of action, or with conventional antiviral drugs. Although, clinical trials and animal models testing have not yet been performed for the majority of the evaluated antiviral peptides, the obtained results from in vivo studies show the optimistic future to prepare the novel anti-CoVs drugs.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

- 1.The new scope of virus taxonomy: partitioning the virosphere into 15 hierarchical ranks. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:668–674. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0709-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen B., Tian E.K., He B., Tian L., Han R., Wang S., Xiang Q., Zhang S., El Arnaout T., Cheng W. Overview of lethal human coronaviruses. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2020;5:89. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0190-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phan M.V.T., Ngo Tri T., Hong Anh P., Baker S., Kellam P., Cotten M. Identification and characterization of Coronaviridae genomes from Vietnamese bats and rats based on conserved protein domains. Virus Evol. 2018;4 doi: 10.1093/ve/vey035. vey035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17:181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung K., Saif L.J., Wang Q. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV): an update on etiology, transmission, pathogenesis, and prevention and control. Virus Res. 2020;286:198045. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramakrishnan S., Kappala D. 2019. Avian Infectious Bronchitis Virus: Recent Advances in Animal Virology; pp. 301–319. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mora-Díaz J.C., Piñeyro P.E., Houston E., Zimmerman J., Giménez-Lirola L.G. Porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus: a review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019;6:53. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koonpaew S., Teeravechyan S., Frantz P.N., Chailangkarn T., Jongkaewwattana A. PEDV and PDCoV Pathogenesis: The interplay between host innate immune responses and porcine enteric coronaviruses. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019;6:34. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Z., Sun Y., Yan X., Tang X., Li Q., Tan Y., Lan T., Ma J. Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV) antagonizes interferon-β production via blocking IPS-1 and RIG-I. Virus Res. 2020;278:197843. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2019.197843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Q., Gerdts V. Transmissible gastroenteritis virus of pigs and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: reference Module in Life Sciences. Encyclopedia Virol. 2019 B978-0-12-809633-8.20928-X. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vilas Boas L.C.P., Campos M.L., Berlanda R.L.A., de Carvalho Neves N., Franco O.L. Antiviral peptides as promising therapeutic drugs. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019;76:3525–3542. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03138-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahlapuu M., Håkansson J., Ringstad L., Björn C. Antimicrobial peptides: an emerging category of therapeutic agents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2016;6:194. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López-Meza J.E., Ochoa-Zarzosa A., Barboza-Corona J.E., Bideshi D.K. Antimicrobial peptides: current and potential applications in biomedical therapies. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015:367243. doi: 10.1155/2015/367243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohammadi Azad Z., Moravej H., Fasihi-Ramandi M., Masjedian F., Nazari R., Mirnejad R., Moosazadeh Moghaddam M. In vitro synergistic effects of a short cationic peptide and clinically used antibiotics against drug-resistant isolates of Brucella melitensis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2017;66:919–926. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moghaddam M.M., Aghamollaei H., Kooshki H., Barjini K.A., Mirnejad R., Choopani A. The development of antimicrobial peptides as an approach to prevention of antibiotic resistance. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 2015;26:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sala A., Ardizzoni A., Ciociola T., Magliani W., Conti S., Blasi E., Cermelli C. Antiviral activity of synthetic peptides derived from physiological proteins. Intervirology. 2018;61:166–173. doi: 10.1159/000494354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal G., Gabrani R. Antiviral eptides: identification and alidation. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2020:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s10989-020-10072-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mustafa S., Balkhy H., Gabere M.N. Current treatment options and the role of peptides as potential therapeutic components for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): a review. J. Infect. Public Health. 2018;11:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moravej H., Moravej Z., Yazdanparast M., Heiat M., Mirhosseini A., Moosazadeh Moghaddam M., Mirnejad R. Antimicrobial peptides: features, action, and their resistance mechanisms in bacteria. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018;24:747–767. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maginnis M.S. Virus-receptor interactions: the key to cellular invasion. J. Mol. Biol. 2018;430:2590–2611. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang T., Bidon M., Jaimes J.A., Whittaker G.R., Daniel S. Coronavirus membrane fusion mechanism offers a potential target for antiviral development. Antiviral Res. 2020;178:104792. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X., Xia S., Wang Q., Xu W., Li W., Lu L., Jiang S. Broad-spectrum coronavirus fusion inhibitors to combat COVID-19 and other emerging coronavirus diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3843. doi: 10.3390/ijms21113843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng B.J., Guan Y., Hez M.L., Sun H., Du L., Zheng Y., Wong K.L., Chen H., Chen Y., Lu L., Tanner J.A., Watt R.M., Niccolai N., Bernini A., Spiga O., Woo P.C., Kung H.F., Yuen K.Y., Huang J.D. Synthetic peptides outside the spike protein heptad repeat regions as potent inhibitors of SARS-associated coronavirus. Antivir. Ther. 2005;10:393–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han D.P., Penn-Nicholson A., Cho M.W. Identification of critical determinants on ACE2 for SARS-CoV entry and development of a potent entry inhibitor. Virology. 2006;350:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho T.Y., Wu S.L., Chen J.C., Wei Y.C., Cheng S.E., Chang Y.H., Liu H.J., Hsiang C.Y. Design and biological activities of novel inhibitory peptides for SARS-CoV spike protein and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 interaction. Antiviral Res. 2006;69:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang H.H., Chen P.K., Lin G.L., Wang C.J., Liao C.H., Hsiao Y.C., Dong J.H., Sun D.S. Cell adhesion as a novel approach to determining the cellular binding motif on the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J. Virol. Methods. 2014;201:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Struck A.W., Axmann M., Pfefferle S., Drosten C., Meyer B. A hexapeptide of the receptor-binding domain of SARS corona virus spike protein blocks viral entry into host cells via the human receptor ACE2. Antiviral Res. 2012;94:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baig M.S., Alagumuthu M., Rajpoot S., Saqib U. Identification of a potential peptide inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 targeting its entry into the host cells. Drugs R D. 2020;20:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s40268-020-00312-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaiswal G., Kumar V. In-silico design of a potential inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 S protein. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0240004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tavassoly O., Safavi F., Tavassoly I. Heparin-binding peptides as novel therapies to stop SARS-CoV-2 cellular entry and infection. Mol. Pharmacol. 2020;98:612–619. doi: 10.1124/molpharm.120.000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C., Wang S., Li D., Wei D.Q., Zhao J., Wang J. Human intestinal defensin 5 inhibits SARS-CoV-2 invasion by cloaking ACE2. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1145–1147. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.L., Abiona O., Graham B.S., McLellan J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu S., Xiao G., Chen Y., He Y., Niu J., Escalante C.R., Xiong H., Farmar J., Debnath A.K., Tien P., Jiang S. Interaction between heptad repeat 1 and 2 regions in spike protein of SARS-associated coronavirus: implications for virus fusogenic mechanism and identification of fusion inhibitors. Lancet. 2004;363:938–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15788-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kliger Y., Levanon E.Y. Cloaked similarity between HIV-1 and SARS-CoV suggests an anti-SARS strategy. BMC Microbiol. 2003;3:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sainz B., Jr., Mossel E.C., Gallaher W.R., Wimley W.C., Peters C.J., Wilson R.B., Garry R.F. Inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infectivity by peptides analogous to the viral spike protein. Virus Res. 2006;120:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan K., Yi L., Chen J., Qu X., Qing T., Rao X., Jiang P., Hu J., Xiong Z., Nie Y., Shi X., Wang W., Ling C., Yin X., Fan K., Lai L., Ding M., Deng H. Suppression of SARS-CoV entry by peptides corresponding to heptad regions on spike glycoprotein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;319:746–752. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu L.H., Chan S.H., Tsai S.N., Wang Y., Cheng C.H., Wong K.B., Waye M.M., Ngai S.M. Fusion core structure of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV): in search of potent SARS-CoV entry inhibitors. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008;104:2335–2347. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ujike M., Nishikawa H., Otaka A., Yamamoto N., Yamamoto N., Matsuoka M., Kodama E., Fujii N., Taguchi F. Heptad repeat-derived peptides block protease-mediated direct entry from the cell surface of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus but not entry via the endosomal pathway. J. Virol. 2008;82:588–592. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01697-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Keefe B.R., Giomarelli B., Barnard D.L., Shenoy S.R., Chan P.K., McMahon J.B., Palmer K.E., Barnett B.W., Meyerholz D.K., Wohlford-Lenane C.L., McCray P.B., Jr. Broad-spectrum in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of the antiviral protein griffithsin against emerging viruses of the family Coronaviridae. J. Virol. 2010;84:2511–2521. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02322-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao H., Zhou J., Zhang K., Chu H., Liu D., Poon V.K., Chan C.C., Leung H.C., Fai N., Lin Y.P., Zhang A.J., Jin D.Y., Yuen K.Y., Zheng B.J. A novel peptide with potent and broad-spectrum antiviral activities against multiple respiratory viruses. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22008. doi: 10.1038/srep22008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu L., Liu Q., Zhu Y., Chan K.H., Qin L., Li Y., Wang Q., Chan J.F., Du L., Yu F., Ma C., Ye S., Yuen K.Y., Zhang R., Jiang S. Structure-based discovery of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion inhibitor. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3067. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Channappanavar R., Lu L., Xia S., Du L., Meyerholz D.K., Perlman S., Jiang S. Protective effect of intranasal regimens containing peptidic Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion inhibitor against MERS-CoV Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;212:1894–1903. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun Y., Zhang H., Shi J., Zhang Z., Gong R. Identification of a novel inhibitor against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Viruses. 2017;9:255. doi: 10.3390/v9090255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang C., Xia S., Zhang P., Zhang T., Wang W., Tian Y., Meng G., Jiang S., Liu K. Discovery of hydrocarbon-stapled short α-helical peptides as promising Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) fusion inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:2018–2026. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang C., Zhao L., Xia S., Zhang T., Cao R., Liang G., Li Y., Meng G., Wang W., Shi W., Zhong W., Jiang S., Liu K. De novo design of α-helical lipopeptides targeting viral fusion proteins: a promising strategy for relatively broad-spectrum antiviral drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:8734–8745. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia S., Lan Q., Pu J., Wang C., Liu Z., Xu W., Wang Q., Liu H., Jiang S., Lu L. Potent MERS-CoV fusion inhibitory peptides identified from HR2 domain in spike protein of bat coronavirus HKU4. Viruses. 2019;11:56. doi: 10.3390/v11010056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang X., Li M., Xu Y., Zhang J., Meng X., An X., Sun L., Guo L., Shan X., Ge J., Chen J., Luo Y., Wu H., Zhang Y., Jiang Q., Ning X. Novel gold nanorod-based HR1 peptide inhibitor for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:19799–19807. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b04240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ling R., Dai Y., Huang B., Huang W., Yu J., Lu X., Jiang Y. In silico design of antiviral peptides targeting the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Peptides. 2020;130:170328. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2020.170328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia S., Liu M., Wang C., Xu W., Lan Q., Feng S., Qi F., Bao L., Du L., Liu S., Qin C., Sun F., Shi Z., Zhu Y., Jiang S., Lu L. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 2020;30:343–355. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0305-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu Y., Yu D., Yan H., Chong H., He Y. Design of potent membrane fusion inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2, an emerging coronavirus with high fusogenic activity. J. Virol. 2020;94:e00635–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00635-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Outlaw V.K., Bovier F.T., Mears M.C., Cajimat M.N., Zhu Y., Lin M.J., Addetia A., Lieberman N.A.P., Peddu V., Xie X., Shi P.Y., Greninger A.L., Gellman S.H., Bente D.A., Moscona A., Porotto M. Inhibition of coronavirus entry in vitro and ex vivo by a lipid-conjugated peptide derived from the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein HRC domain. mBio. 2020;11:e01935–20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01935-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Vries R.D., Schmitz K.S., Bovier F.T., Noack D., Haagmans B.L., Biswas S., Rockx B., Gellman S.H., Alabi C.A., de Swart R.L., Moscona A., Porotto M. Intranasal fusion inhibitory lipopeptide prevents direct contact SARS-CoV-2 transmission in ferrets. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abf4896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao H., To K.K.W., Sze K.H., Yung T.T., Bian M., Lam H., Yeung M.L., Li C., Chu H., Yuen K.Y. A broad-spectrum virus- and host-targeting peptide against respiratory viruses including influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4252. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17986-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Madadlou A. Food proteins are a potential resource for mining cathepsin L inhibitory drugs to combat SARS-CoV-2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020;885:173499. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia S., Xu W., Wang Q., Wang C., Hua C., Li W., Lu L., Jiang S. Peptide-based membrane fusion inhibitors targeting HCoV-229E spike protein HR1 and HR2 domains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:487. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xia S., Yan L., Xu W., Agrawal A.S., Algaissi A., Tseng C.K., Wang Q., Du L., Tan W., Wilson I.A., Jiang S., Yang B., Lu L. A pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting the HR1 domain of human coronavirus spike. Sci. Adv. 2019;5 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav4580. eaav4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ullrich S., Nitsche C. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease as drug target. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;30:127377. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gan Y.R., Huang H., Huang Y.D., Rao C.M., Zhao Y., Liu J.S., Wu L., Wei D.Q. Synthesis and activity of an octapeptide inhibitor designed for SARS coronavirus main proteinase. Peptides. 2006;27:622–625. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang H.Z., Zhang H., Kemnitzer W., Tseng B., Cinatl J., Jr., Michaelis M., Doerr H.W., Cai S.X. Design and synthesis of dipeptidyl glutaminyl fluoromethyl ketones as potent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronovirus (SARS-CoV) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:1198–1201. doi: 10.1021/jm0507678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Day C.W., Baric R., Cai S.X., Frieman M., Kumaki Y., Morrey J.D., Smee D.F., Barnard D.L. A new mouse-adapted strain of SARS-CoV as a lethal model for evaluating antiviral agents in vitro and in vivo. Virology. 2009;395:210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chuck C.P., Ke Z.H., Chen C., Wan D.C., Chow H.F., Wong K.B. Profiling of substrate-specificity and rational design of broad-spectrum peptidomimetic inhibitors for main proteases of coronaviruses. Hong Kong Med. J. 2014;20:22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Du Q.S., Sun H., Chou K.C. Inhibitor design for SARS coronavirus main protease based on “distorted key theory”. Med. Chem. 2007;3:1–6. doi: 10.2174/157340607779317616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu L., George S., Schmidt M.F., Al-Gharabli S.I., Rademann J., Hilgenfeld R. Peptide aldehyde inhibitors challenge the substrate specificity of the SARS-coronavirus main protease. Antiviral Res. 2011;92:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Akaji K., Konno H., Mitsui H., Teruya K., Shimamoto Y., Hattori Y., Ozaki T., Kusunoki M., Sanjoh A. Structure-based design, synthesis, and evaluation of peptide-mimetic SARS 3CL protease inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:7962–7973. doi: 10.1021/jm200870n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yao Y., Luo Z., Zhang X. In silico evaluation of marine fish proteins as nutritional supplements for COVID-19 patients. Food Funct. 2020;11:5565–5572. doi: 10.1039/d0fo00530d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ke M., Chen Y., Wu A., Sun Y., Su C., Wu H., Jin X., Tao J., Wang Y., Ma X., Pan J.A., Guo D. Short peptides derived from the interaction domain of SARS coronavirus nonstructural protein nsp10 can suppress the 2’-O-methyltransferase activity of nsp10/nsp16 complex. Virus Res. 2012;167:322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lo Y.S., Lin S.Y., Wang S.M., Wang C.T., Chiu Y.L., Huang T.H., Hou M.H. Oligomerization of the carboxyl terminal domain of the human coronavirus 229E nucleocapsid protein. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li Q., Zhao Z., Zhou D., Chen Y., Hong W., Cao L., Yang J., Zhang Y., Shi W., Cao Z., Wu Y., Yan H., Li W. Virucidal activity of a scorpion venom peptide variant mucroporin-M1 against measles, SARS-CoV and influenza H5N1 viruses. Peptides. 2011;32:1518–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim J., Yang Y.L., Jang Y.S. Human β-defensin 2 is involved in CCR2-mediated Nod2 signal transduction, leading to activation of the innate immune response in macrophages. Immunobiology. 2019;224:502–510. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim J., Yang Y.L., Jang S.H., Jang Y.S. Human β-defensin 2 plays a regulatory role in innate antiviral immunity and is capable of potentiating the induction of antigen-specific immunity. Virol. J. 2018;15:124. doi: 10.1186/s12985-018-1035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grant W.B., Lahore H., Rockwell M.S. The benefits of vitamin D supplementation for athletes: better performance and reduced risk of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2020;12:3741. doi: 10.3390/nu12123741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ren X., Liu B., Yin J., Zhang H., Li G. Phage displayed peptides recognizing porcine aminopeptidase N inhibit transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus infection in vitro. Virology. 2011;410:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guo D., Zhu Q., Feng L., Sun D. Screening and antiviral analysis of phages that display peptides with an affinity to subunit C of porcine aminopeptidase. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2013;32:326–329. doi: 10.1089/mab.2013.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zou H., Zarlenga D.S., Sestak K., Suo S., Ren X. Transmissible gastroenteritis virus: identification of M protein-binding peptide ligands with antiviral and diagnostic potential. Antiviral Res. 2013;99:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cao L., Ge X., Gao Y., Zarlenga D.S., Wang K., Li X., Qin Z., Yin X., Liu J., Ren X., Li G. Putative phage-display epitopes of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus S1 protein and their anti-viral activity. Virus Genes. 2015;51:217–224. doi: 10.1007/s11262-015-1234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Doki T., Takano T., Koyama Y., Hohdatsu T. Identification of the peptide derived from S1 domain that inhibits type I and type II feline infectious peritonitis virus infection. Virus Res. 2015;204:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peng B., Chen H., Tan Y., Jin M., Chen H., Guo A. Identification of one peptide which inhibited infectivity of avian infectious bronchitis virus in vitro. Sci. China C Life Sci. 2006;49:158–163. doi: 10.1007/s11427-006-0158-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sun Q., Wang K., She R., Ma W., Peng F., Jin H. Swine intestine antimicrobial peptides inhibit infectious bronchitis virus infectivity in chick embryos. Poult. Sci. 2010;89:464–469. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang X., Hu W., Zhu L., Yang Q. Bacillus subtilis and surfactin inhibit the transmissible gastroenteritis virus from entering the intestinal epithelial cells. Biosci. Rep. 2017;37 doi: 10.1042/BSR20170082. BSR20170082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yuan L., Zhang S., Wang Y., Li Y., Wang X., Yang Q. Surfactin inhibits membrane fusion during invasion of epithelial cells by enveloped Viruses. J. Virol. 2018;92:e00809–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00809-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yuan L., Zhang S., Peng J., Li Y., Yang Q. Synthetic surfactin analogues have improved anti-PEDV properties. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0215227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meng F., Suo S., Zarlenga D.S., Cong Y., Ma X., Zhao Q., Ren X. A phage-displayed peptide recognizing porcine aminopeptidase N is a potent small molecule inhibitor of PEDV entry. Virology. 2014;456:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao P., Wang B., Ji C.M., Cong X., Wang M., Huang Y.W. Identification of a peptide derived from the heptad repeat 2 region of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) spike glycoprotein that is capable of suppressing PEDV entry and inducing neutralizing antibodies. Antiviral Res. 2018;150:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu I.J., Tsai W.T., Hsieh L.E., Chueh L.L. Peptides corresponding to the predicted heptad repeat 2 domain of the feline coronavirus spike protein are potent inhibitors of viral infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang X.J., Li C.G., Chi X.J., Wang M. Characterisation and evaluation of antiviral recombinant peptides based on the heptad repeat regions of NDV and IBV fusion glycoproteins. Virology. 2011;416:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bosch B.J., van der Zee R., de Haan C.A., Rottier P.J. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J. Virol. 2003;77:8801–8811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nguyen P.Q., Ooi J.S., Nguyen N.T., Wang S., Huang M., Liu D.X., Tam J.P. Antiviral cystine knot α-amylase inhibitors from alstonia scholaris. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:31138–31150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.654855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liang X., Zhang X., Lian K., Tian X., Zhang M., Wang S., Chen C., Nie C., Pan Y., Han F., Wei Z., Zhang W. Antiviral effects of bovine antimicrobial peptide against TGEV in vivo and in vitro. J. Vet. Sci. 2020;21:e80. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2020.21.e80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wu J., Chi H., Fu Y., Cao A., Shi J., Zhu M., Zhang L., Hua D., Huang J. The antiviral protein viperin interacts with the viral N protein to inhibit proliferation of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Arch. Virol. 2020;165:2279–2289. doi: 10.1007/s00705-020-04747-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Guo N., Zhang B., Hu H., Ye S., Chen F., Li Z., Chen P., Wang C., He Q. Caerin1.1 suppresses the growth of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in vitro via direct binding to the virus. Viruses. 2018;10:507. doi: 10.3390/v10090507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]