Abstract

Background

Communication with patients has always been a major concern in nursing care. Invasive mechanically ventilated (IMV) patients suffer from a communication barrier due to the presence of the endotracheal tube (ETT), which makes them unable to communicate through speech.

Aim

The purpose of this review is to examine available evidence regarding existing knowledge, skills, perceptions and barriers to IMV patient communication in order to guide the development of strategies that enhance effective communication with these patients.

Methods

A review of the published literature was conducted between January 2010 and December 2016.

Results

The literature support clear and concise communication in all areas of care, especially when patients suddenly become speechless. Invasive mechanically ventilated patients want to be heard, have control over their treatment and contribute to decisions concerning their health.

Conclusion

There is a need for the establishment of an effective nurse -patient communication strategy, which may include determining the mode of communication used by the patient, waiting and giving time to allow a patient to participate in the communication, confirming the message that was communicated with a patient himself/ herself, and the use of assistive and augmented communication to support comprehension when needed.

Keywords: communication, communication strategies, critical care, intensive care unit, invasive mechanical ventilation

Introduction

Invasive mechanically ventilated (IMV) patients suffer from a communication barrier due to the presence of the endotracheal tube (ETT), which makes them unable to communicate through speech. Therefore, they may attempt to use different communication methods such as head nods, spoken words, gestures and writing (Happ, et al., 2011). When healthcare providers use communication strategies such as eye blinking to communicate with IMV patients, getting the message through can be extremely frustrating because patients could be directed by some staff members to blink once for ‘yes’ and twice for ‘no’, while directed to do otherwise by other staff personnel. As a result, an inaccurate, inefficient and profoundly improper message exchange could occur (Grossbach et al., 2011a).

Most IMV patients have experienced moderate to high levels of frustration when attempting to communicate their needs (Karlsson et al., 2012b). Thus a communication barrier is the most distressing problem reported in studies tackling IMV patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting (Happ et al., 2011). Furthermore, using invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) can compromise verbal ability because of sedation, neurological problems, or delirium associated with mechanical ventilator use. IMV patients’ communication abilities could be enhanced through the use of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) that could increase the efficiency and speed of communication. Even though there are numerous alternative methods of communication available, caregivers currently make little to no use of these devices for patients in the ICU (Happ et al., 2011; Khalaila et al., 2011).

AAC has been used since 1975 to help IMV patients communicate (McNaughton and Light, 2015). However, few studies have addressed its effects on patient hospitalisation outcomes (Hoorn et al., 2016). There is a wide range of communication aids from basic to high technology, but the selection of the most effective, efficient and safe method is based on the patient’s clinical condition. The purpose of this review is to examine available evidence regarding existing knowledge, skills, perceptions and barriers to IMV patient communication in order to guide the development of strategies that enhance effective communication with these patients.

Methods

A review of the published literature was conducted. Relevant literature published between January 2010 and December 2016 was identified by using various databases, including Medline, Ovid, CINAHL, Sage and PsycINFO. According to Polit and Beck (2012), a literature review enables the researcher to learn from previous theory on the subject in order to highlight gaps in previous research. The search terms included ‘communication’, ‘communication challenges’, ‘communication barrier’, ‘communication strategies’, ‘ICU’, ‘mechanical ventilator experience’, ‘patient experience’, ‘nurse experience’, ‘assistive communication device’ and ‘critical care’. These terms were combined during the literature search in order to ensure the extensive inclusion of clinically relevant research studies that match the purpose of the review.

The search was limited to only PDF articles involving adult patients, which were published in English and within the period between January 2010 and December 2016. Both qualitative and quantitative approaches were considered in order to enhance the generalisability and validity of review results.

Results

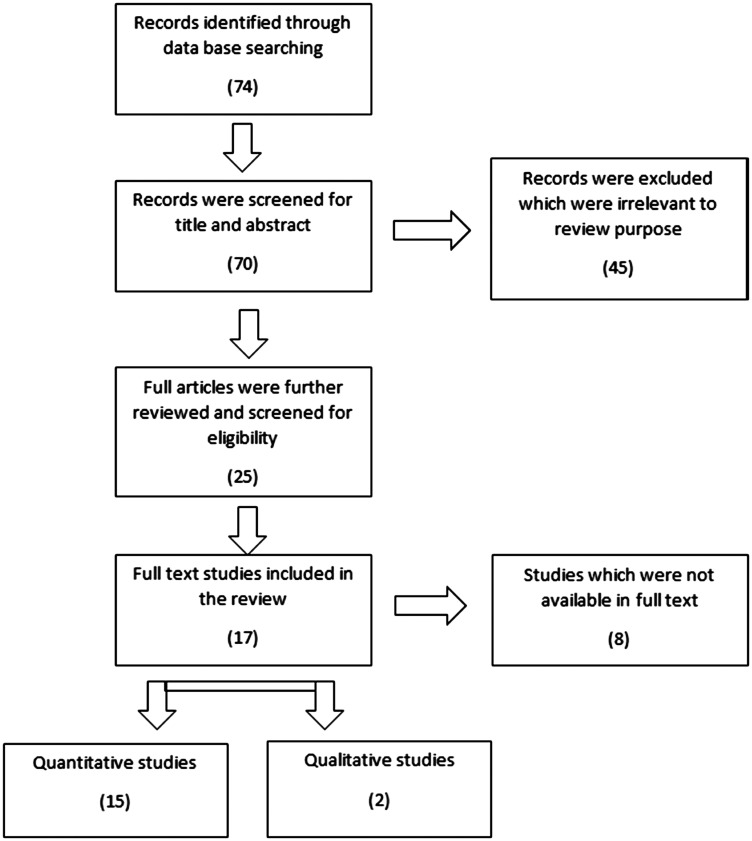

The initial search resulted in 74 articles that were screened by title and abstract. Later, screening continued in a stepwise approach as illustrated in Figure 1. The analyses of the methodological characteristics of the selected studies included countries of origin, study design, purpose, samples, major results and recommendations. Full-text articles were obtained and reviewed to match the inclusion criteria. All studies that did not match the inclusion criteria were excluded. The final review database consisted of a total of 17 full-text articles.

Figure 1.

Integrative review scheme.

The process that was used involved reading and re-reading texts and noting ideas. This was followed by generations of new themes that were included in the review. The studies included 15 quantitative and 2 qualitative research papers. Most selected studies were published in journals related to critical care and intensive care nursing. Communication with IMV patients was investigated in different ways and in various designs. Three of the reviewed studies were descriptive and a number of others were correlational, while none were truly experimental. Five studies were quasi-experimental and six others were reviews of previous literature. All studies aimed at investigating several issues related to the importance of communication with IMV patients, as well as examining the association between communication characteristics and psycho-emotional distress among IMV patients. In addition, the studies addressed the communication challenges that exist between nurses and IMV patients in the ICU. Participants in the studies were nurses and IMV patients. Table 1 provides a summary of the methodological characteristics of the reviewed studies.

Table 1.

Methodological characteristics of the reviewed studies.

| Study | Author | Country | Methods | Purpose | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse–patient communication interactions in the ICU | Happ et al., 2011 | USA | Descriptive observational study | Describe communication interactions, methods and assistive approaches between nurses and non-speaking ICU patients | Convenience sample of 30 ICU adults | Nurses initiated most communication (86.2%) 40% of patients rated communication sessions with nurses as difficult with little or no use of AAC The use of assistive communication strategies with ICU patients is highly recommended |

| Communication difficulties and psycho-emotional distress in patients receiving mechanical ventilation | Khalaila et al., 2011 | Israel | Cross-sectional correlation study | Examine the association between communication characteristics and psycho-emotional distress among patients on IMV | 65 IMV adult patients | Ventilated patients experienced depression, anxiety and anger Communication rated as quite difficult to extremely difficult Inability to speak is the strongest predictor of psycho-emotional distress |

| Nurses’ perceptions of communication training in the ICU | Radtke et al., 2012 | USA | Qualitative focus group | Describe the experiences and perceptions of nurses regarding a communication intervention for use with non-speaking, critically ill patients | 6 critical care nurses | Communication skills training programme could be valuable in reinforcing basic communication strategies, assisting in the acquisition of new skills and ensuring the availability of communication supply |

| Patients’ statements and experiences concerning receiving mechanical ventilation: a prospective video-recorded study | Karlsson et al., 2012b | Sweden | Qualitative content analysis using hermeneutics philosophy | Describe patients’ statements, communication and facial expressions during a video-recorded interview while undergoing mechanical ventilation | 16 patients | Nodding or shaking the head are the most common strategies of communication that IMV patients used Nursing care for IMV patients who are conscious is challenging Caring relationship, making patients feel safe and helping them to communicate are important aspects for alleviating discomfort for IMV patients |

| The changing face of AAC: past, present, and future challenges | Light and McNaughton, 2012 | USA | Literature review | Consider the enormous changes that have taken place in the field of AAC over the past four decades and to reflect on the future challenges | – | There are two main challenges: (a) improving AAC interventions to maximise communication outcomes for individuals with complex communication needs; and (b) ensuring the effective translation of these evidence-based AAC interventions to the everyday lives of individuals with complex communication needs |

| Putting people first: re-thinking the role of technology in AAC intervention | Light and McNaughton, 2013 | USA | Literature review | Answer the question: has our excitement with the new technologies caused us to lose focus on the essence of the field, the people who require AAC? | – | Those who are involved in AAC research and development projects must ensure that the design of AAC technologies is driven by an understanding of cognitive, sensory, motor and linguistic processes, in order to minimise learning demands and maximise communication power for individuals with complex communication needs |

| Gaze-controlled, computer-assisted communication in ICU: ‘speaking through the eyes’ | Maringelli et al., 2013 | Italy | Quasi-experimental | Test the hypothesis that a gaze-controlled communication system (eye tracker) can improve communication processes between completely dysarthric ICU patients and the hospital staff | 15 fully conscious medical and surgical patients, 8 physicians and 15 nurses were included in the study | Patients pre-questionnaires showed remarkable communication deficits Post-intervention questionnaires showed in all groups statistically significant improvement in different communication domains, as well as a remarkable decrease in anxiety Physicians and nurses also reported improvement in their ability to understand patients’ clinical conditions |

| Communication with the person undergoing IMV; what are the strategies? | Cavaco et al., 2013 | – | Systematic review of studies from January 2001 to December 2011 | Outline communication strategies with the person who is undergoing IMV | – | The communication strategies with IMV patients are yes/no signs, voice output communication aids, gestures, nods, lip reading, hand squeezing, facial expression, pen and paper writing, words and picture charts |

| Determining the effectiveness of illustrated communication material for communication with intubated patients in an ICU | Otuzoglu and Karahan, 2014 | Turkey | Semi-experimental design | Develop illustrated communication material that contributes to communication between intubated patients and staff in the ICU | 90 patients who are undergoing open heart surgery | The illustrated communication material was stated to be helpful by 77.8% of patients Control group had more difficulties communicating with healthcare staff |

| Communicative competence for individuals who require AAC: a new definition for a new era of communication? | Light and McNaughton, 2014 | USA | Literature review | Review the preliminary definition of communicative competence, consider the changes in the field, and then determine whether it is still relevant and valid for the new era of communication | – | Communication competence is essential to enhance the quality of life of individuals with complex communication needs; it is fundamental for the fulfilment of basic human needs Communication competence is considered a basic human right |

| Effect of a multilevel intervention on nurse–patient communication in the ICU | Happ et al., 2011 | USA | Quasi-experimental design | Test the impact of two levels of intervention on communication frequency, ease and success between nurses and IMV patients | 89 intubated, awake and unable to speak patients and 30 ICU nurses | The study supports the feasibility and utility of a multilevel communication skills training materials, and speech language pathologist consultation for IMV patients |

| What we write about when we write about AAC: the past 30 years of research and future directions | McNaughton and Light, 2015 | USA | Literature review | The papers published in the AAC journal from 1985 to 2014 in order to identify trends in research and publication activities about AAC | – | There is a special need for reports of interventions with older individuals with complex communication needs as a result of acquired disabilities and for information on effective interventions for the communication partners of persons with complex communication needs |

| Evaluation of Speak for Myself with patients who are voiceless | Koszalinski et al., 2015 | USA | Mixed-methods, quasi-experimental design | Describe the creation and initial feasibility study of a new computer application to improve communication with people who cannot communicate by customary means during their hospital stay | 20 patients | Speak for Myself was helpful to patients who used it Speak for Myself is a new application that ensures the patient’s voice is heard |

| Patients’ experience of being in ICUs | Alasad et al., 2015 | Jordan | Descriptive, exploratory design | Describe the Jordanian patients’ experience during their stay in the ICU and to explore factors that contribute to positive and negative experiences | 98 patients | The ICU environment was found to adversely affect patients in many aspects Most patients were able to recall their ICU experience Understanding patients’ experiences in the ICU would increase nurses’ awareness of patients’ stressors |

| Exploring communication challenges between nurses and mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU | Dithole et al., 2016 | USA | Structured review January 2005 to December 2014 | Identify communication challenges that exist between nurses and IMV patients in the ICU | – | The reviewed literature supports using multifactorial communication intervention that includes: staff training, development of patient materials or devices, and collaboration with healthcare professionals, especially with speech language pathologist, to improve nurse–patient communication as well as improve patient’s outcomes |

| Communicating with conscious and mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a systematic review | Hoorn et al., 2016 | USA | Systematic review | Summarise the current evidence on communication methods with mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU | – | Although there is limited evidence about the effectiveness of using different communication devices with mechanically ventilated patients, a combination of methods is advised The study suggests an algorithm to standardise the approach to the selection of communication techniques |

| A pilot study of eye-tracking devices in intensive care | Garry et al., 2016 | USA | Quasi-experimental: patients participated in five guided sessions with the eye-tracking computer. At the end of sessions, the psychosocial impact of assistive devices scale was used to evaluate the device from the patients’ perspective | To explore the psychosocial impact and communication effects of eye-tracking devices in the ICU | A convenience sample of patients in the medical ICU, surgical ICU, and neurosciences critical care unit were enrolled prospectively | ICU patients’ psychosocial status, delirium and communication ability may be enhanced by eye-tracking devices |

AAC: augmentative and alternative communication; ICU: intensive care unit; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation.

Discussion

Nurse and patient communication in the ICU

Studies tackling ICU nurse–patient interactions reported less than 1 minute in length per typical interaction in the ICU (Happ et al., 2011). The time of nurse–patient interactions indicates the imperative need for nurses to communicate effectively with patients for optimum care and positive patient outcomes. Alasad et al. (2015) conducted a study investigating patients’ experiences in the ICU. The results indicated that 64% of patients wished they knew more about their health status and progress in the ICU, reflecting that the majority of IMV patient communications with nurses was brief and directed towards informing them about procedures rather than providing an explanation regarding their health condition.

The importance of providing communication channels for patients in the ICU is well documented (Rodriguez et al., 2016). For example, effective communication improves patient recovery through enhancing a sense of safety and security, and it might decrease the length of patient stay in the ICU (Sizemore, 2014). Effective communication is considered an essential way of conveying physiological and psychological needs, plan of care and end-of-life decisions (Grossbach et al., 2011a). Thus there is a need for standardised and accurate communication tools to reflect ICU patients’ needs, especially regarding IMV patients who are unable to communicate orally.

A speech-language pathologist (SLP) is an expert in communication disorders. SPLs can conduct training for nurses on the subject of matching communication strategies and resources to meet the individual patient’s needs and preferences. Consequently, positive nurse communication behaviour can be achieved. Moreover, consultation services for SLPs could be required for patients at higher risk of communication difficulties, such as those with prolonged IMV and/or those who have a cognitive problem (Happ et al., 2011).

Communication barriers in the ICU

Caring within the ICU setting can be viewed as different from caring in other nursing environments, especially when it concerns caring for IMV patients who are awake. This is because current evidence supports using minimal sedation levels whenever feasible for IMV patients (Barr et al., 2013). Caring for awake IMV patients may increase uncertainty among ICU nurses, as it is less predictable than caring for sedated patients. Also, it is not always possible for ICU nurses to calm and reassure restless and agitated IMV patients. In addition, the physical proximity to the ICU patient can result in a personal relationship with nurses, which makes it more difficult to maintain a professional distance.

The demanding aspect of caring for awake IMV patients includes complex actions and negotiating nursing care. Awake IMV patients can express subjective and personal needs and wishes. One study examining the relationship between communication characteristics and psychomotor distress among IMV patients indicated that communication (rated by patients as ‘quite difficult’ to ‘extremely difficult’) and lack of speaking ability are the strongest predictors of psycho-emotional distress, as patients also reported moderate feelings of depression, anxiety, anger and fear (Khalaila et al., 2011). Therefore, barriers to communication among IMV patients can be related to being in the ICU and being connected to an invasive mechanical ventilator.

ICU environment

In the ICU, nurses and other health team members provide care for vulnerable patients who are facing life-threatening conditions. Being in the ICU can result in psychological problems and negative emotional outcomes for the majority of patients (Karlsson et al., 2012b). The psychological problems during recovery from critical illness are mainly anxiety, post-traumatic stress and depression (Khalaila et al., 2011). However, the relationship between physical recovery and psychological problems is complex; psychological care has lagged behind physical healthcare during critical illness (Adel et al., 2014).

Despite the fact that the ICU environment is equipped with sophisticated technology that has a valuable role in increasing the quality of care for critically ill patients, technological devices can produce alarm sounds that can disturb patients’ sleep. Thus researchers believe that technology has led to the dehumanisation of patient care (Adel et al., 2014); this is particularly evident when healthcare providers may view patients as objects connected to electronic machines. Nurses have to transform invasive technology’s outcomes in ICU settings to positive patient outcomes by using the time saved by technology as an opportunity to spend more time with patients in the ICU. Furthermore, the literature supports the notion that nurses’ communication with conscious IMV patients can mediate hope and belief in recovery, and strengthen the patient’s drive for survival (Karlsson et al., 2012a).

Previous studies concerning patients’ memories of staying in the ICU indicate both positive and negative outcomes. Negative experiences could include pain, anxiety, cognitive disturbances and lack of sleep. However, patients also recalled positive experiences such as a sense of safety and security by having nurses close to them (Alasad et al., 2015). Critical care nurses can affect ICU patients’ psychological status because they are in a position that enables them to identify the early signs of psychological distress in their patients. In addition to their constant presence as a part of the ICU environment, nurses play a role in producing a therapeutic setting that meets ICU patients’ expectations, as well as the expectations of their families (Alasad et al., 2015).

Mechanical ventilation

MV is an essential life support technology which is an integral component of critical care. There are two approaches in applying MV: negative pressure (which is outside the thorax) and positive pressure to the airway. Positive-pressure ventilation can be applied invasively with an ETT or using a tracheostomy tube, and/or non-invasively using a specific mask. The indications for MV include, but are not limited to, acute ventilator failure, apnoea and severe oxygenation deficit. The goals of MV are to provide adequate oxygenation and alveolar ventilation (Hess and MacIntyre, 2011). Although MV can save a patient’s life, it may have physical and psychological consequences. The serious physical consequences of MV are extensively discussed in previous studies; on the other hand, the psychological consequences have not been adequately addressed, especially for IMV patients who lack verbal communication due to the presence of advanced airways such as ETTs crossing their vocal cords (Khalaila et al., 2011).

Monitoring ICU machines is assumed to be a nursing care responsibility, particularly with regard to life-saving machines such as mechanical ventilators. Nurses are familiar with MV symbols; consequently, an ICU nurse is the human mediation factor between MV technology and the patient’s body (Hess and MacIntyre, 2011). This means that considering the endless alarms of MV while providing physical care for IMV patients, the psychological and social needs of the patient should be assessed. Remarkably, ICU nurses have reported that IMV patients could be at risk of being ignored, neglected and isolated due to ineffective communication (Khalaila et al., 2011).

Alternative communication

The American Speech–Language–Hearing Association (ASHA, 2013) defines AAC as the means of communication when oral speech cannot be achieved. AAC systems are classified as either aided or unaided. Aided alternative communication systems are either electronic or non-electronic and are used to transmit or receive messages (ASHA, 2013). This may include the use of low-technology aids that do not need electronic programming, such as communication books and boards. In addition, high-technology aids, which allow for the easy storage and retrieval of the electronic message, enable the activation and use of a speech-generating device, or other electronic equipment (e.g. computer tablet). Unaided AAC systems are those in which the physical functioning of the body is used as a means to communicate. Some of these include gesturing, pointing or other body language movements (ASHA, 2013). Multiple AAC systems may be used in ICUs, depending on a patient’s physical and cognitive status (Downey and Happ, 2013).

Many health conditions require the use of an AAC device, including post-stroke patients with aphasia, patients who have been diagnosed with a degenerative motor neurone disease, head injury and dementia (Light and McNaughton, 2013). Patients require the use of AAC systems when they are intubated or have a tracheostomy tube while under mechanical ventilation (Rodriguez et al., 2016). Other general medical conditions that may prevent oral speech, whether disruptions are long or short term, mandate the use of an AAC device.

Although AAC devices are useful, they still have a number of limitations. One set of barriers that may influence the implementation of AAC devices within the ICU is the negative attitude of healthcare providers (especially the nursing staff) towards AAC devices, such as high workload and the complex conditions from which patients suffer, which could limit AAC use as nurses need to fulfil numerous tasks within a limited amount of time (Radtke et al., 2012). The extent to which nurses have been exposed to and trained to use AAC devices may also affect how they will implement them in the ICU. In addition, the uncertainty about the nurses’ role in AAC system provision, lack of access to communication tools and a number of other factors may impede the implementation process (Downey and Happ, 2013). Furthermore, the quality of AAC devices, their availability and their effectiveness depend on an individualised adaptation of communication devices in the fast-paced and time-critical ICU environment (Dithole et al., 2016). Furthermore, multiple patient-related factors may hinder the use of an AAC system in the ICU. These include impaired cognitive and physical status, language impairment, deep sedation levels and the psychological state.

The effect of training and ACC use on the communication interactions among patients in the ICU

Radtke et al. (2012) conducted a clinical trial to assess the effects of communication training and AAC use on communication interactions with ICU patients; it was found that nurses have positive communication behaviour after communication training on AAC devices. The nurses initiated communication in 88.2% of exchanges. Study results highlighted specific areas for improvement in communication between nurses and non-speaking patients in the ICU, particularly about communication of pain and the use of assistive communication strategies and materials.

In the analysis of a trial that tested the initial feasibility of using AAC devices for patients admitted to the ICU, the findings claimed that ventilated patients are capable of communicating effectively, they can use a new computer application named Speak for Myself, which is specific enough to reflect their needs, ensuring that the patient’s voice is heard (Koszalinski et al., 2015). This finding has been supported by another study by Otuzoglu and Karahan (2014), as the authors claimed that 77.8% of patients appreciated the healthcare staff using illustrated materials to facilitate communication.

Gaps in the literature

There are many problems associated with IMV patients’ inability to speak (Happ et al., 2011). However, previous studies lack the quantitative data regarding the pervasiveness of these problems. Studies on nurse–patient interactions have shown that nurses communicate minimally with IMV patients (Cavaco et al., 2013). Numerous previous studies have addressed the lack of AAC systems in the ICU (e.g. Hoorn et al., 2016). Furthermore, the outcomes for IMV patients post-AAC system implementation are not adequately researched. Moreover, research on examining protocols on current patients for AAC use in the ICU is still deficient (Downey and Happ, 2013).

Conclusions

Several studies have asserted that patients who are undergoing invasive MV reported a moderate to extreme level of psycho-emotional distress, as they are not able to speak or communicate their needs. Previous studies have clearly outlined that IMV patients have reported levels of anxiety, anger and fear. The vast majority of IMV patients have experienced pain and suffering, which challenges ICU nurses in responding promptly and thoughtfully. Having a nursing staff member in the ICU who is familiar with general communication strategies and is well trained on AAC systems would probably lead to an increase in the quality of patient care for various reasons. Patients may become more satisfied, comfortable and cooperative with the staff. Also, meeting patients’ needs and enhancing comfort during their stay in the ICU may improve their health outcomes in the ICU setting. Many strategies could be used to assist nurses to communicate effectively with ICU patients. The literature supports using multifactorial communication interventions, development of patient communication devices or materials, staff training in communication, and collaboration with other healthcare professionals in order to improve patient–health team members’ communication.

Future directions and recommendations

Increasing nursing awareness of IMV patients’ experiences and needs will help in the development of effective interventions to facilitate communication with these patients. According to the Joint Commission International accreditation requirements, patients have the right to, and need for, effective communication. Effective communication is necessary for patients’ safety. The first step is to identify the patient’s oral and written communication needs to determine how to facilitate the conversation with him or her during the care process. Once the patient’s communication needs are identified, the healthcare provider can determine the best way to aid two-way communication in a manner that meets the patient’s needs (Joint Commission International, 2016).

Therefore, further research is needed to assess the ease of communication among IMV patients during AAC device use. Furthermore, true experimental studies are encouraged to test the effectiveness of AAC devices. Moreover, qualitative studies are needed to explore patients’ stories and experiences while being on an invasive mechanical ventilator. Future studies could compare and contrast nurses with other healthcare workers (such as physicians, pharmacists and technicians) in order to view the matter from a wider perspective with regard to communication practices with IMV patients.

Limitations

Most studies in this review are limited to nurses. In addition, the lack of available qualitative research on the ease of communication with IMV patients limits the richness of detail in this paper.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

Invasive mechanically ventilated patients have the right and the need for effective communication.

Nurses need to adopt different communication tools to meet diverse IMV patients' needs.

Units with IMV patients need to develop local policies regarding communication and ensure they are implemented.

Further research is needed that focuses on the effectiveness of AAC devices and their effects on IMV patient outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the support of The University of Jordan.

Biography

Aziza Salem works in King Hussein Cancer Center, University of Jordan, Jordan as a Senior Education Coordinator.

Muayyad M Ahmad is the Professor of Adult Health Nursing, Clinical Nursing Department, University of Jordan, Jordan.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethics

All ethical principles were handled appropriately while conducting this review.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adel L, Mohamed M, Sobh D. (2014) Nurses’ perception regarding the use of technological devices in critical care units. Journal of Nursing and Health Science 3(5): 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Alasad J, Abu Taber N, Ahmad M. (2015) Patients’ experience of being in intensive care units. Journal of Critical Care 30(5): 857–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Speech–Language–Hearing Association (ASHA) (2013) Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Available at: http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/AAC/ (accessed 19 June 2018).

- Barr J, Fraser G, Puntillo K, et al. (2013) Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. American Journal of Health System Pharmacy 70(1): 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaco V, Jose H, Lourenco I. (2013) Communicating with the person undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation: What are the strategies? A systematic review. Journal of Nursing UFPE online 7(6): 4535–4543. [Google Scholar]

- Dithole K, Sibanda S, Moleki M, et al. (2016) Exploring communication challenges between nurses and mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: A structured review. World Views on Evidence-based Nursing 13(3): 197–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey D, Happ M. (2013) The need for nurse training to promote improved patient–provider communication for patients with complex communication needs. Perspectives on Augmentative and Alternative Communication 22(2): 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Garry J, Casey K, Cole TK, et al. (2016) A pilot study of eye-tracking devices in intensive care. Surgery 159(3): 938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossbach I, Chlan L, Tracy M. (2011. a) Overview of mechanical ventilatory support and management of patient- and ventilator-related responses. Critical Care Nurse 31(3): 30–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happ M, Garrett K, Thomas D, et al. (2011) Nurse–patient communication interactions in the intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care 20(2): 28–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess D, MacIntyre N. (2011) Mechanical ventilation. In: Hess D, MacIntyre N, Mishoe S, et al.(eds) Respiratory Care Principles and Practices, Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett, pp. 462–492. [Google Scholar]

- Hoorn S, Elbers P, Tuinman P. (2016) Communicating with conscious and mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: A systematic review. Critical Care 20(333): 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission International (2016) International Patient Safety Goals. Available at: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/improve/international-patient-safety-goals/ (accessed 19 June 2018).

- Karlsson V, Bergbom I, Forsberg A. (2012. a) The lived experiences of adult intensive care patients who were conscious during mechanical ventilation: A phenomenological–hermeneutic study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 28(1): 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson V, Lindah B, Bergbom I. (2012. b) Patients’ statements and experiences concerning receiving mechanical ventilation: A prospective video-recorded study. Nursing Inquiry 19(3): 247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaila R, Zbidat W, Anwar K, et al. (2011) Communication difficulties and psychoemotional distress in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. American Journal of Critical Care 20(6): 470–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koszalinski RS, Tappen RM, Viggiano D. (2015) Evaluation of Speak for Myself with patients who are voiceless. Rehabilitation Nursing 40(4): 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J, McNaughton D. (2012) The changing face of augmentative and alternative communication: Past, present, and future challenges. Augmentative and Alternative Communication 28(4): 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J, McNaughton D. (2013) Putting people first: Re-thinking the role of technology in augmentative and alternative communication intervention. Augmentative and Alternative Communication 29(4): 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J, McNaughton D. (2014) Communicative competence for individuals who require augmentative and alternative communication: A new definition for a new era of communication? Augmentative and Alternative Communication 30(1): 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton D, Light J. (2015) What we write about when we write about AAC: The past 30 years of research and future directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication 31(4): 261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maringelli F, Brienza N, Scorrano F, et al. (2013) Gaze-controlled, computer-assisted communication in intensive care unit: “speaking through the eyes”. Minerva Anestesiologica 79(2): 165–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otuzoglu M, Karahan A. (2014) Determining the effectiveness of illustrated communication material for communication with intubated patients at an intensive care unit. International Journal of Nursing Practice 20(5): 490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, Beck CT. (2012) Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Radtke J, Tate J, Happ M. (2012) Nurses’ perceptions of communication training in the ICU. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 28(1): 16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C, Rowe M, Thomas L, et al. (2016) Enhancing the communication of suddenly speechless critical care patients. American Journal of Critical Care 25(3): 40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sizemore JT (2014) Augmentative and alternative communication in the intensive care unit. Online Theses and Dissertations Paper 219. Available at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/219.