Abstract

Background

A national clinical academic training programme has been developed in England for nurses, midwives and allied health professionals but is insufficient to build a critical mass to have a significant impact on improved patient care.

Aim

We describe a partnership model led by the University of Southampton and its neighbouring National Health Service partners that has the potential to address this capacity gap. In combination with the Health Education England/National Institute of Health Research Integrated Clinical Academic programme, we are currently supporting nurses, midwives and allied health professionals at Master’s (n = 28), Doctoral (n = 36), Clinical Lecturer (n = 5) and Senior Clinical Lecturer (n = 2) levels working across seven National Health Service organisations, and three nurses hold jointly funded Clinical Professor posts.

Results

Key to the success of our partnership model is the strength of the strategic relationship developed at all levels across and within the clinical organisations involved, from board to ward. We are supporting nurses, midwives and allied health professionals to climb, in parallel, both clinical and academic career ladders. We are creating clinical academic leaders who are driving their disciplines forward, impacting on improved health outcomes and patient benefit.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that our partnership model is sustainable and could enable doctoral capacity to be built at scale.

Keywords: allied health professionals, clinical academic, midwifery, NHS, nursing, partnership, leadership

Background

Individuals and healthcare organisations engaged in research have the capacity to deliver higher quality care and improved outcomes (Hanney et al., 2013). Research is vital to provide the transformative and sustainable health and care services needed to meet the challenge of a population that is living longer, often with complex needs (NHS England, 2014). Patients and service users expect to receive the highest quality care informed by robust evidence. A clinical academic workforce can respond to this challenge, but there is an urgent need to build capacity and capability in order to generate the new leaders required to deliver this agenda.

Clinical academics are clinically active health researchers. They work in health and social care as clinicians to improve, maintain, or recover health while in parallel researching new ways of delivering better outcomes for the patients they treat and care for. Clinical academics also work in Higher Education Institutions while providing clinical expertise to health and social care. Because they remain clinically active, their research is grounded in the day-to-day issues of their patients and service. This dual role also allows the clinical academic to combine their clinical and research career rather than having to choose between the two. (National Institute of Health Research, 2016)

They teach, question, investigate, research, innovate and build cultures of evidence-based practice to accelerate improvements in clinical care. They work in multidisciplinary and inter-professional teams, using research skills and analytical thinking to understand clinical problems, develop evidence-based solutions and implement change impacting on cost savings by the reduction in inefficiencies, doing the right thing the first time (Westwood et al., 2013). This is the workforce required to lead and move the nursing, midwifery and allied health disciplines forward, developing interventions to improve health outcomes for patient benefit (Macleod Clark, 2014).

Our medical and dental colleagues have a long established tradition of nurturing and sustaining a clinical academic workforce, but the Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professions (NMAHP) workforce has no such tradition. Doctors and dentists are subject to continuous development during their early, mid and senior career phases, and can access a career pathway characterised by a combination of clinical and research components. Their traditional starting point and launch pad for a clinical academic career is research training through a Doctoral training programme. The Association of UK University Hospitals (AUKUH) has declared a goal that 1% of the NMAHP workforce will be in clinical academic roles by 2030 (currently 0.1%; AUKUH, 2010), and this compares with 5% of the current UK medical consultant workforce (Medical Schools Council, 2016).

Clinical academic pathways for nurses, midwives and allied health professionals (AHPs) have been under development in the UK since 2005. NHS Wales (2005) has developed the Research Capacity Building Collaboration, and in Scotland a Clinical Academic Research Career Framework and accompanying Principles (2011) was developed with the aim to provide a sustainable and consistent structure to guide clinical research collaborations and role development. In England a commitment was made to develop a cadre of NMAHPs with the capability to lead research and embed evidence into front-line care delivery to improve clinical outcomes (Department of Health, 2012). Health Education England (HEE), following the Willis Report Shape of Caring (2015) (HEE, 2015), has been obligated to support and advance the quality and standards of education from Care Certificate level to PhD and beyond, including clinical academic careers.

Whilst it acknowledged that evidence-based practice (EBP) is now integrated into health professional undergraduate training, academics must stay clinically current and therefore lead by example (Malik et al., 2016). The perpetuation of EBP in practice is reliant on clinical leaders championing EBP. The Willis Report also recommended greater development of postgraduate clinical doctoral centres to drive up clinical research in practice and increase the number of academics in practice. This vision will provide a career and education structure with the capacity to unleash the transformational potential of NMAHP clinical academics. Of the 10 commitments in the English framework for nursing, midwifery and care staff ‘Leading Change, Adding Value’ (NHS England, 2016) two reference the impact research will have on the delivery of evidence-based care: 1) nurses, midwives and care staff will lead and drive research, and 2) clinical academic careers will be developed for nurses and midwives.

The National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) vision is to improve the health and wealth of the nation through research, and aims to achieve this through several strategic goals, one of which is to establish the National Health Service (NHS) as an internationally recognised centre of research excellence, to help attract, develop and retain the best research professionals to conduct people-based research (NIHR, 2017). Many NHS organisations have defined strategies concerned with achieving these aims, including 1) embedding research (by integrating research into organisational culture, policies and practice so every professional ‘thinks research’), 2) maximising patient participation in high quality, funded, NHS-focused research and 3) developing an expert workforce and clinical research infrastructure to improve capability and capacity. In response to the UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC) Report (2007), HEE in partnership with the NIHR has developed the Integrated Clinical Academic (ICA) Programme. This provides fully funded personal training awards for healthcare professionals (excluding doctors and dentists) from pre-Master’s to Clinical Professor level and will enable the NMAHP workforce to develop as clinical academic leaders (NIHR, 2012).

Whilst HEE/NIHR and the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) in England have a remit to develop and sustain non-medical clinical academic capacity, these awards are insufficient to create a critical mass (Cooke et al., 2016) to deliver the 1% AUKUH aspiration. In order to achieve this, higher education instituties (HEIs) in partnership with healthcare providers need to begin to invest in, and develop, clinical academic training pathways, and a number of locally funded training schemes have been developed in different parts of the UK (AUKUH, 2016). Tensions between HEIs and NHS organisations encountered whilst engaged in efforts to develop this workforce have been documented (Springett et al., 2014). This paper identifies that whilst the NHS and HEIs agreed on the importance of EBP, staff development, education of students and staff at all levels and person-centred care, there were differences and potential tensions between the NHS and HEIs. These included efficiency of services (important to the NHS), grants and publications (important to HEIs) and diversifying income (important to HEIs). NHS respondents identified the lack of time for research and the frequent lack of connection between senior management strategy and how these roles work in practice. A resource to aid NHS organisational leads to develop and embed clinical academic roles for NMAHPs has recently been published (AUKUH, 2016), but no literature exists on how healthcare providers and HEIs actually build collaborative relationships to prepare and develop this workforce.

In this paper we describe a Clinical Academic Partnership Model, formed through a strategic relationship between the University of Southampton and several NHS organisations. We have integrated the priorities of both sectors and together found ways to work with, and around, the challenges identified by Springett et al. (2014). In particular we have worked directly with Directors of Nursing and clinical managers to embed these roles into the organisations and clinical practice.

The Clinical Academic Partnership Model

Setting

An HEI – the University of Southampton Faculty of Health Sciences – and its neighbouring NHS organisations (seven acute, three community, an integrated acute, a community and ambulance NHS organisation and an ambulance service) in the South of England. These NHS organisations provide healthcare to approximately 2.8 million people.

Partnership development

In 2008 the university partnered with three NHS organisations and the then Workforce Development Directorate of the Strategic Health Authority (SHA) to develop the forerunner to the current Clinical Academic Partnership model. The first award holders (50% clinical and 50% academic) were appointed: four Doctoral, two post-Doctoral and a Clinical Professor. Posts were jointly funded by the NHS organisations and the SHA (Latter et al., 2009). In 2012 a Clinical Academic Co-ordinator was appointed – a joint NHS and university appointment – to further develop the scheme and identify and establish additional NHS partners. This post acted as a conduit to manage joint investment, recruitment and support for clinical academic fellows. Governance is ensured through a Clinical Academic Strategy Group; its membership includes NHS, Faculty and Clinical Academic members.

The University of Southampton and its NHS partners jointly agreed the clinical academic strategy and vision: to be a world leading centre of excellence, generating exceptional clinical academic health professionals who use critical thinking and creativity to advance practice, transform healthcare and improve the health and well-being of the population of Wessex with national and international influence.

The partnership co-created the strategy and hence cross-organisational commitment to build clinical academic capacity and capability. Together the partnership aimed to:

attract, recruit and retain high quality and high potential health professionals;

develop and maintain a high quality infrastructure and environment to support the pathway;

establish and sustain a diverse portfolio of clinical academic funding streams and evidence the impact our clinical academics have on health, care and research.

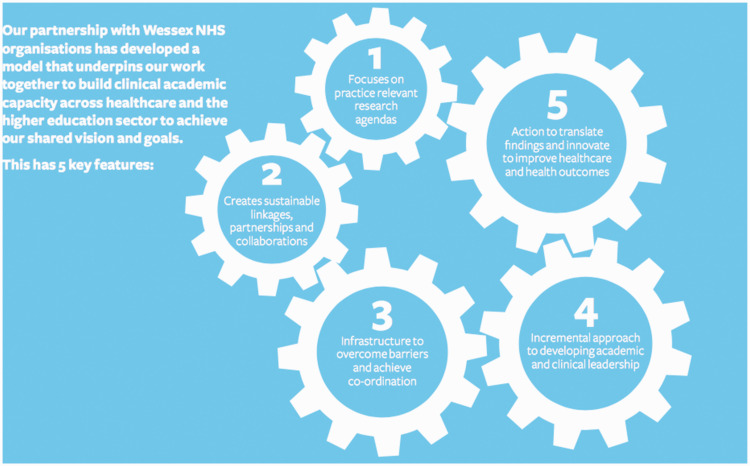

The Clinical Academic Partnership Model was therefore developed with reference to five key features (Figure 1 and Table 1):

practice-relevant research aligned to NHS priorities;

powerful and sustainable NHS–HEI collaborations;

investment commitment;

incremental approach to developing academic and clinical leadership;

translation of findings into practice.

Figure 1.

Clinical academic partnership training pathway: five key features.

NHS: National Health Service

Table 1.

Clinical academic partnership training pathway: five key features and actions.

| Feature | What is involved |

|---|---|

| 1. Focuses on practice-relevant research agendas for patient benefit that is close to practice | Including clinicians, managers and researchers in mutually agreeing topics in priority areas; planning to generate knowledge relevant to patients and healthcare organisations; co-ordinating research programmes between NHS organisations and the HEI |

| 2. Creates powerful and sustainable partnerships and collaborations | A named Clinical Academic Co-ordinator responsible for developing partnerships between HEI and NHS organisations Creating linkages between clinical and research teams, and novice and experienced researchers Creating mechanisms by which research skills and practice knowledge are exchanged, developed and enhanced in pursuit of service improvement Establishing joint appointments Enabling new collaborations among clinicians, teams, networks and organisations |

| 3. Makes investments in infrastructure to develop strategy, co-ordinate activities and overcome barriers | Establishing strategic Steering Group and operational delivery group with representation from Health Education Wessex, NHS organisations and the University of Southampton Developing and implementing key strategic and operational elements of programme on behalf of organisations Securing engagement from named senior individuals from HEI and NHS organisations to input to strategic and operational developments Making provision for space dedicated to housing clinical academic staff |

| 4. Incremental approach to developing research and clinical leadership across the pathway | Agreeing a career pathway and capability framework that describes progressive skill and knowledge development Providing training schemes, mentorship and supervision opportunities; providing clinical, leadership and quality improvement skills development |

| 5. Translates findings and innovates and educates to improve healthcare and health outcomes | Supporting the development of critical thinking, which can be applied to practice decision making Developing leadership skills to work with clinical teams, services and departments in order to generate improvements to care pathways and local services Working to achieve innovation, knowledge translation (implementing products, technologies and services) and knowledge mobilisation (use of research evidence) Contributing to training future generations of health professionals |

Clinical academic opportunities

This partnership model enables health professionals, who have the potential and aspiration to become leading clinical academics and independent researchers in the future, to access a clinical academic pathway, irrespective of the clinical or academic stage they have reached in their career. They are able to apply for pre-Master’s internships, Master’s in Clinical Research, Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowships, pre- or post-Doctoral transitional internships and post-Doctoral personal awards. The partnership also hosts individuals who are in receipt of an NIHR/HEE personal ICA training award; three who hold Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowships, five Clinical Lecturers and two Senior Clinical Lecturers. The emphasis throughout the pathway is on clinical and academic leadership and is underpinned by the AUKUH Clinical and Academic Careers Capability Framework (Westwood and Richardson, 2014). Funding is provided by the NHS partners, the University of Southampton Faculty of Health Sciences, the NIHR CLAHRC Wessex, Health Education England Wessex (HEW) and one industry partner.

Pre-Doctoral awards

Up to 10 HEE/NIHR-funded clinical academic pre-Master’s internships and five HEW-funded pre-Doctoral transitional internships are offered annually to NMAHPs working in NHS organisations across Wessex; applicants for both awards are selected and progress is monitored by HEW. These awards offer an introduction to clinical research, including working with professors and research teams to undertake a specific research role, for example a literature search or undertaking Master’s in Clinical Research (MRes) modules. Between 2009 and 2015 the University of Southampton has been one of 10 HEIs funded by NIHR/HEE to provide between 10 and 15 MRes personal awards annually to healthcare professionals who work clinically in the NHS.

Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship Scheme

Following the original 2008 scheme the Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship (CDRF) Scheme now includes a 40% clinical element with 60% of time spent working towards a PhD. The scheme has undergone continuous refinement for improvement. Experience of the early clinical academic schemes and feedback from a range of stakeholders provided a platform to explore and clarify aspects of these training fellowships that previously have received little attention, including management arrangements and mentorship support. Originally fellows were full-time students with a full-time stipend and worked in the NHS on an honorary contract for 4 years. Fellows experienced practical difficulties with this arrangement. Importantly, whilst the stipend increased year on year in line with NHS pay annual increments, many reported they were unable to apply for promotion as they had committed to the term of the fellowship.

An independent local evaluation of the full-time student model was commissioned by the then Wessex Clinical Academic Steering Group in 2014 (Masterson, unpublished) to understand from fellows, academic supervisors and clinical mentors the elements of the scheme that worked well, and those that should be addressed for improvement.

Nine actions were taken forward and are now embedded in the model as part of the partnership approach:

A cross-cohort CDRF buddying system is to be set up.

Attention is to be paid to the clinical development pathway and milestones expected alongside the academic development.

Annual tripartite fellowship planning meetings between academic supervisors, clinical mentor/manager and fellow are to become a mandatory requirement.

Consideration is to be given to either making completion of the preceptorship for new graduates compulsory before commencing the fellowship or extending to 4.5 years to involve 6 months’ immersion in practice at the outset of the programme.

Recruitment and selection processes are to be reviewed to include explicit consideration of personal resilience and involvement of relevant clinical staff in the selection process.

Clinical staff are to be involved in developing and selecting research topics.

Focused work is to be undertaken with NHS managers regarding the benefits and infrastructure required to best support all CDRFs.

Consideration is to be given to developing a critical mass of fellows in particular services rather than spreading them across multiple services.

All stakeholders are to undertake further collaborative work on developing a sustainable career pathway from post-Doctoral to Clinical Professor post following completion of the fellowship, and pay particular attention to building transition arrangements between schemes at different stages of the training pathway.

After discussion with NHS partners, in 2015 it was agreed the scheme would be revised to become a part-time student, part-time employment model. Since 2016 all new CDRFs have had a 40% NHS contract and in addition to this receive an annual stipend. Fellows work clinically within an agreed clinical service and are registered as part time MPhil/PhD students. All fellows are fully funded by either the NHS or university, or a combination of the NHS, university, a charity, industry or NIHR CLAHRC Wessex.

Post-Doctoral awards

HEW continues to offer and administer post-Doctoral awards, available to those with clinical experience to further develop academic skills or those with academic experience to develop skills in clinical practice. Each year up to five post-doctoral awards are offered and administered by HEW to NMAHPs across Wessex. The transition internships, described earlier, are available to individuals at either pre- or post-Doctoral level. The partnership supports individuals on HEE/NIHR ICA Clinical Lecturer and Senior Clinical Lecturer and HEW awards by providing commitment to both clinical and academic opportunities.

The story to date

Since 2008, 74 professionals have completed awards at Master’s, five at Doctoral and eight at post-Doctoral level. Through our local CDRF scheme we currently support 36 Clinical Doctoral Research Nurse, Midwife, Podiatrist, Dietician, Occupational Therapist, Speech Therapist and Physiotherapist Fellows working across seven Wessex NHS organisations whilst undertaking a PhD. Another 10 are planned to start in the academic year 2017–2018, and two additional NHS organisations (one outside of Wessex) have now joined the partnership. In addition, the partnership is supporting three HEE/NIHR CDRFs, five NIHR/HEE Clinical Lecturers and two Senior Clinical Lecturers. All clinical academics are undertaking research in the following broad research themes: complex healthcare processes (44%), fundamental care and safety (36%), active living and rehabilitation (14%) and health work and systems (6%). A Clinical Professor was initially supported with SHA funding and subsequent recurrent funding was secured by the university and the host NHS organisation. In addition to this post there are a further two jointly (NHS and HEI) funded Clinical Professors.

Discussion

The medical profession has a good track record of nurturing those who wish to develop as clinical academics, supported by robust, organisationally embedded career pathways and funding streams. In implementing our clinical academic NMAHP strategy we have started to replicate and extend this. We have developed a clinical academic partnership model that complements the national (NIHR) personal awards programmes. Our partnership is built on developing relationships, infrastructure and mechanisms to ensure sustainability and growth. The five key features of the partnership are crucial to its success: practice-relevant research; powerful and sustainable collaborations; investment commitment; incremental approach to academic and clinical leadership; and the translation of findings into practice. NHS Directors of NMAHP are critical to decision-making as new NHS partnerships are developed. They, alongside clinicians, managers and academic supervisors, mutually agree on research topics, recruit and interview individuals for awards, and monitor progress and impact. We have connected NHS Trust Boards and senior management to our strategy to support integration within the clinical areas, a critical factor in our success, and a potential tension noted by Springett et al. (2014).

This partnership has developed clinical academic capacity and capability; in particular we have created a critical mass of Clinical Doctoral Research Fellows. We have, in effect, developed a Doctoral Training Centre for health professionals to support and nurture this sector of the workforce. Working with our NHS partner organisations we can support predictable numbers of fellows year on year. We believe our partnership model could be replicated across other organisations, but would need to take into account the resources needed to drive success. In particular, for the development and success of the CDRF Scheme, the Clinical Academic Co-ordinator post was key to:

developing strategic-level discussions with Directors of Nursing and clinical service managers to influence commitment to funding;

engaging both the university and NHS organisations’ human resources and legal services to develop joint contracts;

linking academic supervisors to the practice-relevant research projects;

liaising with academic and clinical managers to ensure objective-setting and progress review for individual award holders.

Together we have not been constrained by uncertainty; our learning has been incremental. We have listened to our fellows and partners and sought to continuously improve our training pathway to ensure that clinical and academic requirements are met. We have been flexible to ensure that the research priorities of our partners are accommodated. Towards the end of individuals’ personal clinical academic training awards, we work together to develop appropriate joint roles to retain our skilled clinical researchers and enable them to continue on their clinical academic career pathway.

Conclusion

There is a national clinical academic training scheme in England for the NMAHP workforce, but this is insufficient to build the leadership capacity required to support the seismic transformation needed to underpin improvements in heath and well-being, improve the care and quality of health services, and reduce the finance and efficiency gap in the health system. We are working to address the gap in clinical academic capability and capacity in the nursing, midwifery and allied health professions (NMAHP). We will continue to invest and build partnerships with our established and new NHS, third sector and industry partners to support other clinical academic training opportunities and substantive roles across the entire pathway. Our success has largely been due to the commitment demonstrated by all partners and a spirit of collaborative working focused on co-production and implementation of a strategy. This approach has provided a template for our neighbouring universities and their partner health provider organisations. In the event that future national HEE/NIHR ICA funding is reduced, we have demonstrated that our partnership model is sustainable and could enable Doctoral capacity to be built at scale. We are driving the health disciplines forward by creating clinical academic leaders who are having an impact on health outcomes and bringing significant benefits for patient care.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

Clinical academic nurses, midwives and allied health professionals are clinically active health researchers.

They teach, question, investigate, research, innovate and build cultures of evidence-based practice to accelerate improvements in clinical care.

A national clinical academic training is insufficient to build a clinical academic leadership capacity.

Higher education institutes need to build partnerships with healthcare providers to begin to invest in and develop local clinical academic training pathways that can build leadership as well as research capacity.

Acknowledgements

NHS Directors of Nursing and clinical managers who host the clinical academics at the following partner NHS organisations:

• Bournemouth & Christchurch NHS Foundation Trust

• Dorset County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

• Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

• Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust

• Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust

• Solent NHS Trust

• Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust

• University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust

• Wessex Sussex NHS Foundation Trust.

Health Education England, Wessex, NIHR CLAHRC Wessex, Academic Supervisors, Clinical Academic Fellows, Post Graduate Research Team, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southampton.

Biography

Greta Westwood now works for a major nursing and midwifery charity, the Florence Nightingale Foundation. Before this post Greta held a joint post (2012–2017) with Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust (PHT) and the University of Southampton as Deputy Director of Research for PHT, Director of Clinical Academic Practice for the university and NIHR CLAHRC Wessex. She led the university's clinical academic training programme for nurses, midwives and allied health professionals.

Alison Richardson is Clinical Professor of Cancer Nursing and End of Life Care at the University of Southampton and University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust. She is committed to the development of productive and sustainable clinical academic non-medical careers and provides leadership to a cadre of clinical academic nurses at Southampton. Alison is part of a multidisciplinary team caring for patients with cancer and approaching the end of life to improve patient care through the generation and application of research. Her research centres on understanding the experiences of people affected by cancer and other life limiting illnesses and developing nurse-led interventions that can respond to the issues and problems that people have to confront as part of their day-to-day lives.

Sue Latter is lead for the Medicines Optimisation Research Theme at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southampton. Sue is leading national and international research into prescribing and medicines optimisation, as part of supporting patient self-management of long-term conditions, end-of-life care and promoting antimicrobial stewardship. Her research and publications also include a focus on patient experience of self-management and evaluation of patient-centred interventions for self-management of long-term conditions. Sue plays a leading role in the development of clinical academic careers for nurses, midwives and allied health professionals in the UK.

Jill Macleod Clark is a Professor within the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southampton. Her research interests focus around evidence-based nursing interventions, and the promotion of health, choice and quality of life for individuals coping with enduring illness or who are at the end of life. She is campaigning at a national and local policy level for the development of embedded clinical academic career pathways for nurses, midwives and allied health professionals.

Mandy Fader is the Dean of Health Sciences and works with patients, microbiologists, engineers and designers to understand the limitations and problems of current products, analyse the needs of different users and create new ways of managing incontinence and new products that people can trust.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was not required for this work.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Association of UK University Hospitals (AUKUH) (2010) National Clinical Academic Roles Development Group for Nurses, Midwives and Allied Health Professionals. Available at: http://www.aukuh.org.uk/index.php/affiliate-groups/nmahps (accessed 1 April 2017).

- Association of UK University Hospitals (AUKUH) (2016) Transforming healthcare through clinical academic roles in nursing, midwifery and allied health professions: A practical resource for healthcare provider organisations. Available at: http://www.medschools.ac.uk/SiteCollectionDocuments/Transforming-Healthcare.pdf (accessed 1 April 2017).

- Cooke J, Bray K and Sriram V (2016) Mapping research capacity activities in the CLAHRC community: Supporting non-medical professionals. Available at: http://www.clahrcprojects.co.uk/sites/default/files/uploads/235%20Summary%20report%20print.pdf (accessed March 2017).

- Department of Health (2012) Developing the Role of the Clinical Academic Researcher in the Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professionals, London accessed December 2017 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/developing-the-role-of-the-clinical-academic-researcher-in-the-nursing-midwifery-and-allied-health-professions.

- Hanney S, Boaz A, Jones T, et al. (2013) Engagement in research: An innovative three-stage review of the benefits for health-care performance. Health Services Delivery Research 1(8): 65–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Education England (HEE) (2015) HEE/NIHR ICA – Health Education England (HEE) and National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Clinical Academic (ICA) Programme for non-medical health care professions. Available at: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/funding-and-support/funding-for-training-and-career-development/training-programmes/nihr-hee-ica-programme/ (accessed September 2017).

- Latter S, Macleod Clark J, Geddes C, et al. (2009) Implementing a clinical academic career pathway in nursing: Criteria for success and challenges ahead. Journal of Research in Nursing 14(2): 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Macleod Clark J. (2014) Clinical academic leadership – moving the profession forward. Journal of Research in Nursing 19(2): 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Malik G, McKenna L, Griffiths D. (2016) How do nurse academics value and engage with evidence-based practice across Australia: Findings from a grounded theory study. Nurse Education Today June(41): 54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Schools Council (2016) Clinical academic survey. Available at: http://www.medschools.ac.uk/AboutUs/Projects/clinicalacademia/Pages/Promoting-Clinical-Academic-Careers.aspx (accessed April 2017).

- National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) (2016) Building a Research Career Handbook. Available at: http://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/faculty/Building-a-research-career-handbook.pdf (accessed June 2016).

- National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) (2017) Vision, mission and aims. Available at: http://www.nihr.ac.uk/about-us/our-purpose/vision-mission-and-aims/ (accessed March 2017).

- NHS England (2014) Five year forward view. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/futurenhs/ (accessed April 2017).

- NHS England (2016) Leading change, adding value. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/leadingchange/about/ (accessed August 2017).

- NHS Scotland (2011) National guidance for clinical academic research careers for nursing, midwifery and allied health professions in Scotland. Available at: http://www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/education-and-training/by-discipline/nursing-and-midwifery/resources/publications/national-guidance-for-clinical-academic-research-careers-for-nursing,-midwifery-and-allied-health-professions-in-scotland.aspx (accessed September 2017).

- NHS Wales (2005) Research Capacity Building Collaboration (RCBC) . Available at: http://www.rcbcwales.org.uk/about-1/ (accessed September 2017).

- Springett K, Norton C, Louth S, et al. (2014) Eliminate tensions to make research work on the front line. Available at: https://www.hsj.co.uk/leadership/eliminate-tensions-to-make-research-work-on-the-front-line/5075013.article?blocktitle=Resource-Centre&contentID=8630#.VDgAEfldVI5 (accessed March 2017).

- UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC) (2007) Report of the UKCRC Subcommittee for Nurses in Clinical Research (2007). Developing the best research professionals. Qualified graduate nurses: Recommendations for preparing and supporting clinical academic nurses of the future. Available at: http://www.ukcrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Nurses-report-August-07-Web.pdf (accessed April 2017).

- Westwood G and Richardson A (2014) Clinical Academic Careers Capability Framework. Available at: http://www.aukuh.org.uk/index.php/affiliate-groups/nmahps/resources-for-individuals (accessed August 2016).

- Westwood G, Fader M, Roberts L, et al. (2013) How clinical academics are transforming patient care.Health ServicesJournal 27 September. Available at: http://www.hsj.co.uk/home/innovation-and-efficiency/how-clinical-academics-are-transforming-patient-care/5062463.article (accessed September 2017).

- Willis (2015) Raising the bar. Shape of caring: A review of the future education and training of Registered Nurses and care assistants. Available at: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2348-Shape-of-caring-review-FINAL_0.pdf (accessed June 2016).