Abstract

Qualitative content analysis consists of conventional, directed and summative approaches for data analysis. They are used for provision of descriptive knowledge and understandings of the phenomenon under study. However, the method underpinning directed qualitative content analysis is insufficiently delineated in international literature. This paper aims to describe and integrate the process of data analysis in directed qualitative content analysis. Various international databases were used to retrieve articles related to directed qualitative content analysis. A review of literature led to the integration and elaboration of a stepwise method of data analysis for directed qualitative content analysis. The proposed 16-step method of data analysis in this paper is a detailed description of analytical steps to be taken in directed qualitative content analysis that covers the current gap of knowledge in international literature regarding the practical process of qualitative data analysis. An example of “the resuscitation team members' motivation for cardiopulmonary resuscitation” based on Victor Vroom's expectancy theory is also presented. The directed qualitative content analysis method proposed in this paper is a reliable, transparent, and comprehensive method for qualitative researchers. It can increase the rigour of qualitative data analysis, make the comparison of the findings of different studies possible and yield practical results.

Keywords: deductive content analysis, directed content analysis, qualitative content analysis, qualitative research

Introduction

Qualitative content analysis (QCA) is a research approach for the description and interpretation of textual data using the systematic process of coding. The final product of data analysis is the identification of categories, themes and patterns (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Hsieh and Shannon, 2005; Zhang and Wildemuth, 2009). Researchers in the field of healthcare commonly use QCA for data analysis (Berelson, 1952). QCA has been described and used in the first half of the 20th century (Schreier, 2014). The focus of QCA is the development of knowledge and understanding of the study phenomenon. QCA, as the application of language and contextual clues for making meanings in the communication process, requires a close review of the content gleaned from conducting interviews or observations (Downe-Wamboldt, 1992; Hsieh and Shannon, 2005).

QCA is classified into conventional (inductive), directed (deductive) and summative methods (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005; Mayring, 2000, 2014). Inductive QCA, as the most popular approach in data analysis, helps with the development of theories, schematic models or conceptual frameworks (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Graneheim and Lundman, 2004; Vaismoradi et al., 2013, 2016), which should be refined, tested or further developed by using directed QCA (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). Directed QCA is a common method of data analysis in healthcare research (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008), but insufficient knowledege is available about how this method is applied (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). This may hamper the use of directed QCA by novice qualitative researchers and account for a low application of this method compared with the inductive method (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Mayring, 2000). Therefore, this paper aims to describe and integrate methods applied in directed QCA.

Methods

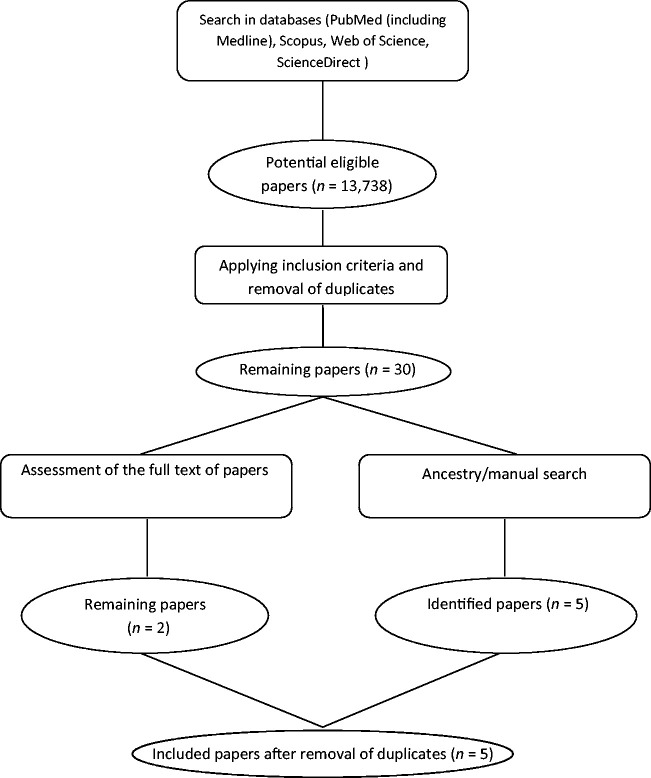

International databases such as PubMed (including Medline), Scopus, Web of Science and ScienceDirect were searched for retrieval of papers related to QCA and directed QCA. Use of keywords such as ‘directed content analysis’, ‘deductive content analysis’ and ‘qualitative content analysis’ led to 13,738 potentially eligible papers. Applying inclusion criteria such as ‘focused on directed qualitative content analysis’ and ‘published in peer-reviewed journals’; and removal of duplicates resulted in 30 papers. However, only two of these papers dealt with the description of directed QCA in terms of the methodological process. Ancestry and manual searches within these 30 papers revealed the pioneers of the description of this method in international literature. A further search for papers published by the method's pioneers led to four more papers and one monograph dealing with directed QCA (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The search strategy for the identification of papers.

Finally, the authors of this paper integrated and elaborated a comprehensive and stepwise method of directed QCA based on the commonalities of methods discussed in the included papers. Also, the experiences of the current authors in the field of qualitative research were incorporated into the suggested stepwise method of data analysis for directed QCA (Table 1).

Table 1.

The suggested steps for directed content analysis.

| Steps | References |

|---|---|

| Preparation phase | |

| 1. Acquiring the necessary general skills | Elo et al. (2014), Thomas and Magilvy (2011) |

| 2. Selecting the appropriate sampling strategy | Inferred by the authors of the present paper from Elo et al. (2014) |

| 3. Deciding on the analysis of manifest and/or latent content | Elo and Kyngäs (2008) |

| 4. Developing an interview guide | Inferred by the authors of the present paper from Hsieh and Shannon (2005) |

| 5. Conducting and transcribing interviews | Elo and Kyngäs (2008), Graneheim and Lundman (2004) |

| 6. Specifying the unit of analysis | Graneheim and Lundman (2004) |

| 7. Being immersed in data | Elo and Kyngäs (2008) |

| Organisation phase | |

| 8. Developing a formative categorisation matrix | Inferred by the authors of the present paper from Elo and Kyngäs (2008) |

| 9. Theoretically defining the main categories and subcategories | Mayring (2000, 2014) |

| 10. Determining coding rules for main categories | Mayring (2014) |

| 11. Pre-testing the categorisation matrix | Inferred by the authors of the present paper from Elo et al. (2014) |

| 12. Choosing and specifying the anchor samples for each main category | Mayring (2014) |

| 13. Performing the main data analysis | Graneheim and Lundman (2004), Mayring (2000, 2014) |

| 14. Inductive abstraction of main categories from preliminary codes | Elo and Kyngäs (2008) |

| 15. Establishment of links between generic categories and main categories | Suggested by the authors of the present paper |

| Reporting phase | |

| 16. Reporting all steps of directed content analysis and findings | Elo and Kyngäs (2008), Elo et al. (2014) |

Findings

While the included papers about directed QCA were the most cited ones in international literature, none of them provided sufficient detail with regard to how to conduct the data analysis process. This might hamper the use of this method by novice qualitative researchers and hinder its application by nurse researchers compared with inductive QCA. As it can be seen in Figure 1, the search resulted in 5 articles that explain DCA method. The following is description of the articles, along with their strengths and weaknesses. Authors used the strengths in their suggested method as mentioned in Table 1.

The methods suggested for directed QCA in the international literature

The method suggested by Hsieh and Shannon (2005)

Hsieh and Shannon (2005) developed two strategies for conducting directed QCA. The first strategy consists of reading textual data and highlighting those parts of the text that, on first impression, appeared to be related to the predetermined codes dictated by a theory or prior research findings. Next, the highlighted texts would be coded using the predetermined codes.

As for the second strategy, the only difference lay in starting the coding process without primarily highlighting the text. In both analysis strategies, the qualitative researcher should return to the text and perform reanalysis after the initial coding process (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). However, the current authors believe that this second strategy provides an opportunity for recognising missing texts related to the predetermined codes and also newly emerged ones. It also enhances the trustworthiness of findings.

As an important part of the method suggested by Hsieh and Shannon (2005), the term ‘code’ was used for the different levels of abstraction, but a more precise definition of this term seems to be crucial. For instance, they stated that ‘data that cannot be coded are identified and analyzed later to determine if they represent a new category or a subcategory of an existing code’ (2005: 1282).

It seems that the first ‘code’ in the above sentence indicates the lowest level of abstraction that could be achieved instantly from raw data. However, the ‘code’ at the end of the sentence refers to a higher level of abstraction, because it denotes to a category or subcategory.

Furthermore, the interchangeable and inconsistent use of the words ‘predetermined code’ and ‘category’ could be confusing to novice qualitative researchers. Moreover, Hsieh and Shannon (2005) did not specify exactly which parts of the text, whether highlighted, coded or the whole text, should be considered during the reanalysis of the text after initial coding process. Such a lack of specification runs the risk of missing the content during the initial coding process, especially if the second review of the text is restricted to highlighted sections. One final important omission in this method is the lack of an explicit description of the process through which new codes emerge during the reanalysis of the text. Such a clarification is crucial, because the detection of subtle links between newly emerging codes and the predetermined ones is not straightforward.

The method suggested by Elo and Kyngäs (2008)

Elo and Kyngäs (2008) suggested ‘structured’ and ‘unconstrained’ methods or paths for directed QCA. Accordingly, after determining the ‘categorisation matrix’ as the framework for data collection and analysis during the study process, the whole content would be reviewed and coded. The use of the unconstrained matrix allows the development of some categories inductively by using the steps of ‘grouping’, ‘categorisation’ and ‘abstraction’. The use of a structured method requires a structured matrix upon which data are strictly coded. Hypotheses suggested by previous studies often are tested using this method (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008).

The current authors believe that the label of ‘data gathering by the content’ (p. 110) in the unconstrained matrix path can be misleading. It refers to the data coding step rather than data collection. Also, in the description of the structured path there is an obvious discrepancy with regard to the selection of the portions of the content that fit or do not fit the matrix: ‘… if the matrix is structured, only aspects that fit the matrix of analysis are chosen from the data …’; ‘… when using a structured matrix of analysis, it is possible to choose either only the aspects from the data that fit the categorization frame or, alternatively, to choose those that do not’ (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008: 111–112).

Figure 1 in Elo and Kyngäs's paper (2008: 110) clearly distinguished between the structured and unconstrained paths. On the other hand, the first sentence in the above quotation clearly explained the use of the structured matrix, but it was not clear whether the second sentence referred to the use of the structured or unconstrained matrix.

The method suggested by Zhang and Wildemuth (2009)

Considering the method suggested by Hsieh and Shannon (2005), Zhang and Wildemuth (2009) suggested an eight-step method as follows: (1) preparation of data, (2) definition of the unit of analysis, (3) development of categories and the coding scheme, (4) testing the coding scheme in a text sample, (5) coding the whole text, (6) assessment of the coding's consistency, (7) drawing conclusions from the coded data, and (8) reporting the methods and findings (Zhang and Wildemuth, 2009). Only in the third step of this method, the description of the process of category development, did Zhang and Wildemuth (2009) briefly make a distinction between the inductive versus deductive content analysis methods. On first impression, the only difference between the two approaches seems to be the origin from which categories are developed. In addition, the process of connecting the preliminary codes extracted from raw data with predetermined categories is described. Furthermore, it is not clear whether this linking should be established from categories to primary codes, or vice versa.

The method suggested by Mayring (2000, 2014)

Mayring (2000, 2014) suggested a seven-step method for directed QCA that distinctively differentiated between inductive and deductive methods as follows: (1) determination of the research question and theoretical background, (2) definition of the category system such as main categories and subcategories based on the previous theory and research, (3) establishing a guideline for coding, considering definitions, anchor examples and coding rules, (5) reading the whole text, determining preliminary codes, adding anchor examples and coding rules, (5) revision of the category and coding guideline after working through 10–50% of the data, (6) reworking data if needed, or listing the final category, and (7) analysing and interpreting based on the category frequencies and contingencies.

Mayring suggested that coding rules should be defined to distinctly assign the parts of the text to a particular category. Furthermore, indicating which concrete part of the text serves as typical examples, also known as ‘anchor samples’, and belongs to a particular category was recommended for describing each category (Mayring, 2000, 2014). The current authors believe that these suggestions help clarify directed QCA and enhance its trustworthiness.

But when the term ‘preliminary coding’ was used, Mayring (2000, 2014) did not clearly clarify whether these codes are inductively or deductively created. In addition, Mayring was inclined to apply the quantitative approach implicitly in steps 5 and 7, which is incongruent with the qualitative paradigm. Furthermore, nothing was stated about the possibility of the development of new categories from the textual material: ‘… theoretical considerations can lead to a further categories or rephrasing of categories from previous studies, but the categories are not developed out of the text material like in inductive category formation …’ (Mayring, 2014: 97).

Integration and clarification of methods for directed QCA

Directed QCA took different paths when the categorisation matrix contained concepts with higher-level versus lower-level abstractions. In matrices with low abstraction levels, linking raw data to predetermined categories was not difficult, and suggested methods in international nursing literature seem appropriate and helpful. For instance, Elo and Kyngäs (2008) introduced ‘mental well-being threats’ based on the categories of ‘dependence’, ‘worries’, ‘sadness’ and ‘guilt’. Hsieh and Shannon (2005) developed the categories of ‘denial’, ‘anger’, ‘bargaining’, ‘depression’ and ‘acceptance’ when elucidating the stages of grief. Therefore, the low-level abstractions easily could link raw data to categories. The predicament of directed QCA began when the categorisation matrix contained the concepts with high levels of abstraction. The gap regarding how to connect the highly abstracted categories to the raw data should be bridged by using a transparent and comprehensive analysis strategy. Therefore, the authors of this paper integrated the methods of directed QCA outlined in the international literature and elaborated them using the phases of ‘preparation’, ‘organization’ and ‘reporting’ proposed by Elo and Kyngäs (2008). Also, the experiences of the current authors in the field of qualitative research were incorporated into their suggested stepwise method of data analysis. The method was presented using the example of the “team members’ motivation for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)” based on Victor Vroom's expectancy theory (Assarroudi et al., 2017). In this example, interview transcriptions were considered as the unit of analysis, because interviews are the most common method of data collection in qualitative studies (Gill et al., 2008).

Suggested method of directed QCA by the authors of this paper

This method consists of 16 steps and three phases, described below: preparation phase (steps 1–7), organisation phase (steps 8–15), and reporting phase (step 16).

The preparation phase:

The acquisition of general skills. In the first step, qualitative researchers should develop skills including self-critical thinking, analytical abilities, continuous self-reflection, sensitive interpretive skills, creative thinking, scientific writing, data gathering and self-scrutiny (Elo et al., 2014). Furthermore, they should attain sufficient scientific and content-based mastery of the method chosen for directed QCA. In the proposed example, qualitative researchers can achieve this mastery through conducting investigations in original sources related to Victor Vroom's expectancy theory. Main categories pertaining to Victor Vroom's expectancy theory were ‘expectancy’, ‘instrumentality’ and ‘valence’. This theory defined ‘expectancy’ as the perceived probability that efforts could lead to good performance. ‘Instrumentality’ was the perceived probability that good performance led to desired outcomes. ‘Valence’ was the value that the individual personally placed on outcomes (Vroom, 1964, 2005).

Selection of the appropriate sampling strategy. Qualitative researchers need to select the proper sampling strategies that facilitate an access to key informants on the study phenomenon (Elo et al., 2014). Sampling methods such as purposive, snowball and convenience methods (Coyne, 1997) can be used with the consideration of maximum variations in terms of socio-demographic and phenomenal characteristics (Sandelowski, 1995). The sampling process ends when information ‘redundancy’ or ‘saturation’ is reached. In other words, it ends when all aspects of the phenomenon under study are explored in detail and no additional data are revealed in subsequent interviews (Cleary et al., 2014). In line with this example, nurses and physicians who are the members of the CPR team should be selected, given diversity in variables including age, gender, the duration of work, number of CPR procedures, CPR in different patient groups and motivation levels for CPR.

Deciding on the analysis of manifest and/or latent content. Qualitative researchers decide whether the manifest and/or latent contents should be considered for analysis based on the study's aim. The manifest content is limited to the transcribed interview text, but latent content includes both the researchers' interpretations of available text, and participants' silences, pauses, sighs, laughter, posture, etc. (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). Both types of content are recommended to be considered for data analysis, because a deep understanding of data is preferred for directed QCA (Thomas and Magilvy, 2011).

Developing an interview guide. The interview guide contains open-ended questions based on the study's aims, followed by directed questions about main categories extracted from the existing theory or previous research (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). Directed questions guide how to conduct interviews when using directed or conventional methods. The following open-ended and directed questions were used in this example: An open-ended question was ‘What is in your mind when you are called for performing CPR?’ The directed question for the main category of ‘expectancy’ could be ‘How does the expectancy of the successful CPR procedure motivate you to resuscitate patients?’

Conducting and transcribing interviews. An interview guide is used to conduct interviews for directed QCA. After each interview session, the entire interview is transcribed verbatim immediately (Poland, 1995) and with utmost care (Seidman, 2013). Two recorders should be used to ensure data backup (DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree, 2006). (For more details concerning skills required for conducting successful qualitative interviews, see Edenborough, 2002; Kramer, 2011; Schostak, 2005; Seidman, 2013).

Specifying the unit of analysis. The unit of analysis may include the person, a program, an organisation, a class, community, a state, a country, an interview, or a diary written by the researchers (Graneheim and Lundman, 2004). The transcriptions of interviews are usually considered units of analysis when data are collected using interviews. In this example, interview transcriptions and filed notes are considered as the units of analysis.

Immersion in data. The transcribed interviews are read and reviewed several times with the consideration of the following questions: ‘Who is telling?’, ‘Where is this happening?’, ‘When did it happen?’, ‘What is happening?’, and ‘Why?’ (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). These questions help researchers get immersed in data and become able to extract related meanings (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Elo et al., 2014).

The organisation phase:

Developing a formative categorisation matrix. A formative matrix of main categories and related subcategories is deductively derived from the existing theory or previous research (Mayring, 2000, 2014). The prominent feature of this formative matrix is the derivation of main categories from existing theory or previous research, along with the potential emergence of new main categories through the inductive approach (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). In the provided example, the formative matrix consists of ‘expectancy’, ‘instrumentality’, ‘valence’ and other possible main categories developed as the result of an inductive QCA study (Table 2).

Theoretical definition of the main categories and subcategories. Derived from the existing theory or previous research, the theoretical definitions of categories should be accurate and objective (Mayring, 2000, 2014). As for this example, ‘expectancy’ as a main category could be defined as the “subjective probability that the efforts by an individual led to an acceptable level of performance (effort–performance association) or to the desired outcome (effort–outcome association)” (Van Eerde and Thierry, 1996; Vroom, 1964).

- Determination of the coding rules for main categories. The coding rules as the description of the properties of main categories are developed based on theoretical definitions (Mayring, 2014). The coding rule contributes to a clearer distinction between the main categories of the matrix, thereby improving the trustworthiness of the study. For example, the following rules are extracted from the theoretical definition of ‘expectancy’ as the main category of this study example:

- – Expectancy in the CPR was a subjective probability formed in the rescuer's mind.

- – This subjective probability should be related to the association between the effort–performance or effort–outcome relationship perceived by the rescuer.

The pre-testing of the categorisation matrix. The categorisation matrix should be tested using a pilot study. This is an essential step, particularly if more than one researcher is involved in the coding process. In this step, qualitative researchers should independently and tentatively encode the text, and discuss the difficulties in the use of the categorisation matrix and differences in the interpretations of the unit of analysis. The categorisation matrix may be further modified as a result of such discussions (Elo et al., 2014). This also can increase inter-coder reliability (Vaismoradi et al., 2013) and the trustworthiness of the study.

Choosing and specifying the anchor samples for each main category. An anchor sample is an explicit and concise exemplification, or the identifier of a main category, selected from meaning units (Mayring, 2014). An anchor sample for ‘expectancy’ as the main category of this example could be as follows: ‘… the patient with advanced metastatic cancer who requires CPR … I do not envision a successful resuscitation for him.’

Performing the main data analysis. Meaning units related to the study's aims and categorisation matrix should be selected from the reviewed content. Next, they are summarised (Graneheim and Lundman, 2004) and given preliminary codes (Mayring, 2000, 2014) (Table 3).

The inductive abstraction of main categories from preliminary codes. Preliminary codes are grouped and categorised according to their meanings, similarities and differences. The products of this categorisation process are known as ‘generic categories’ (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008) (Table 3).

The establishment of links between generic categories and main categories. The constant comparison of generic categories and main categories results in the development of a conceptual and logical link between generic and main categories, nesting generic categories into the pre-existing main categories and creating new main categories. The constant comparison technique is applied to data analysis throughout the study (Zhang and Wildemuth, 2009) (Table 3).

Table 2.

The categorisation matrix of the team members' motivation for CPR.

| Motivation for CPR | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Expectancy | Instrumentality | Valence | Other inductively emerged categories |

CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Table 3.

An example of steps taken for the abstraction of the phenomenon of expectancy (main category).

| Meaning unit | Summarised meaning unit | Preliminary code | Group of codes | Subcategory | Generic category | Main category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The patient with advanced heart failure: I do not envisage a successful resuscitation for him | No expectation for the resuscitation of those with advanced heart failure | Cardiovascular conditions that decrease the chance of successful resuscitation | Estimation of the functional capacity of vital organs | Scientific estimation of life capacity | Estimation of the chances of successful CPR | Expectancy |

| Patients are rarely resuscitated, especially those who experience a cardiogenic shock following a heart attack | Low possibility of resuscitation of patients with a cardiogenic shock | |||||

| When ventricular fibrillation is likely, a chance of resuscitation still exists even after performing CPR for 30 minutes | The higher chance of resuscitation among patients with ventricular fibrillation | Cardiovascular conditions that increase the chance of successful resuscitation | ||||

| Patients with sudden cardiac arrest are more likely to be resuscitated through CPR | The higher chance of resuscitation among patients with sudden cardiac arrest | |||||

| Estimation of the severity of the patient's complications | ||||||

| Estimation of remaining life span | ||||||

| Intuitive estimation of the chances of successful resuscitation | ||||||

| Uncertainty in the estimation | ||||||

| Time considerations in resuscitation | ||||||

| Estimation of self-efficacy |

CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation

The reporting phase:

Reporting all steps of directed QCA and findings. This includes a detailed description of the data analysis process and the enumeration of findings (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). Findings should be systematically presented in such a way that the association between the raw data and the categorisation matrix is clearly shown and easily followed. Detailed descriptions of the sampling process, data collection, analysis methods and participants' characteristics should be presented. The trustworthiness criteria adopted along with the steps taken to fulfil them should also be outlined. Elo et al. (2014) developed a comprehensive and specific checklist for reporting QCA studies.

Trustworthiness

Multiple terms are used in the international literature regarding the validation of qualitative studies (Creswell, 2013). The terms ‘validity’, ‘reliability’, and ‘generalizability’ in quantitative studies are equivalent to ‘credibility’, ‘dependability’, and ‘transferability’ in qualitative studies, respectively (Polit and Beck, 2013). These terms, along with the additional concept of confirmability, were introduced by Lincoln and Guba (1985). Polit and Beck added the term ‘authenticity’ to the list. Collectively, they are the different aspects of trustworthiness in all types of qualitative studies (Polit and Beck, 2013).

To ehnance the trustworthiness of the directed QCA study, researchers should thoroughly delineate the three phases of ‘preparation’, ‘organization’, and ‘reporting’ (Elo et al., 2014). Such phases are needed to show in detail how categories are developed from data (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Graneheim and Lundman, 2004; Vaismoradi et al., 2016). To accomplish this, appendices, tables and figures may be used to depict the reduction process (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Elo et al., 2014). Furthermore, an honest account of different realities during data analysis should be provided (Polit and Beck, 2013). The authors of this paper believe that adopting this 16-step method can enhance the trustworthiness of directed QCA.

Discussion

Directed QCA is used to validate, refine and/or extend a theory or theoretical framework in a new context (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). The purpose of this paper is to provide a comprehensive, systematic, yet simple and applicable method for directed QCA to facilitate its use by novice qualitative researchers.

Despite the current misconceptions regarding the simplicity of QCA and directed QCA, knowledge development is required for conducting them (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). Directed QCA is often performed on a considerable amount of textual data (Pope et al., 2000). Nevertheless, few studies have discussed the multiple steps need to be taken to conduct it. In this paper, we have integrated and elaborated the essential steps pointed to by international qualitative researchers on directed QCA such as ‘preliminary coding’, ‘theoretical definition’ (Mayring, 2000, 2014), ‘coding rule’, ‘anchor sample’ (Mayring, 2014), ‘inductive analysis in directed qualitative content analysis’ (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008), and ‘pretesting the categorization matrix’ (Elo et al., 2014). Moreover, the authors have added a detailed discussion regarding ‘the use of inductive abstraction’ and ‘linking between generic categories and main categories’.

Conclusion

The importance of directed QCA is increased due to the development of knowledge and theories derived from QCA using the inductive approach, and the growing need to test the theories. Directed QCA proposed in this paper, is a reliable, transparent and comprehensive method that may increase the rigour of data analysis, allow the comparison of the findings of different studies, and yield practical results.

Biography

Abdolghader Assarroudi (PhD, MScN, BScN) is Assistant Professor in Nursing, Department of Medical‐Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran. His main areas of research interest are qualitative research, instrument development study and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Fatemeh Heshmati Nabavi (PhD, MScN, BScN) is Assistant Professor in nursing, Department of Nursing Management, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. Her main areas of research interest are medical education, nursing management and qualitative study.

Mohammad Reza Armat (MScN, BScN) graduated from the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences in 1991 with a Bachelor of Science degree in nursing. He completed his Master of Science degree in nursing at Tarbiat Modarres University in 1995. He is an instructor in North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnourd, Iran. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in nursing at the Mashhad School of Nursing and Midwifery, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Abbas Ebadi (PhD, MScN, BScN) is professor in nursing, Behavioral Sciences Research Centre, School of Nursing, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. His main areas of research interest are instrument development and qualitative study.

Mojtaba Vaismoradi (PhD, MScN, BScN) is a doctoral nurse researcher at the Faculty of Nursing and Health Sciences, Nord University, Bodø, Norway. He works in Nord’s research group ‘Healthcare Leadership’ under the supervision of Prof. Terese Bondas. For now, this team has focused on conducting meta‐synthesis studies with the collaboration of international qualitative research experts. His main areas of research interests are patient safety, elderly care and methodological issues in qualitative descriptive approaches. Mojtaba is the associate editor of BMC Nursing and journal SAGE Open in the UK.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

In this paper, essential steps pointed to by international qualitative researchers in the field of directed qualitative content analysis were described and integrated.

A detailed discussion regarding the use of inductive abstraction, and linking between generic categories and main categories, was presented.

A 16-step method of directed qualitative content analysis proposed in this paper is a reliable, transparent, comprehensive, systematic, yet simple and applicable method. It can increase the rigour of data analysis and facilitate its use by novice qualitative researchers.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Ebadi A, et al. (2017) Professional rescuers' experiences of motivation for cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A qualitative study. Nursing & Health Sciences. 19(2): 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berelson B. (1952) Content Analysis in Communication Research, Glenoce, IL: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, Horsfall J, Hayter M. (2014) Data collection and sampling in qualitative research: Does size matter? Journal of Advanced Nursing 70(3): 473–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne IT. (1997) Sampling in qualitative research.. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? Journal of Advanced Nursing 26(3): 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. (2013) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- DiCicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. (2006) The qualitative research interview. Medical Education 40(4): 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downe-Wamboldt B. (1992) Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care for Women International 13(3): 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edenborough R. (2002) Effective Interviewing: A Handbook of Skills and Techniques, 2nd edn. London: Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62(1): 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, et al. (2014) Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open 4(1): 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, et al. (2008) Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal 204(6): 291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today 24(2): 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15(9): 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer EP. (2011) 101 Successful Interviewing Strategies, Boston, MA: Course Technology, Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry, Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring P. (2000) Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 1(2): Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/2-00/02-00mayring-e.htm (accessed 10 March 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Mayring P. (2014) Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution, Klagenfurt: Monograph. Available at: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed 10 May 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Poland BD. (1995) Transcription quality as an aspect of rigor in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry 1(3): 290–310. [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, Beck CT. (2013) Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice, 7th edn. China: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. (2000) Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 320(7227): 114–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. (1995) Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health 18(2): 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schostak J. (2005) Interviewing and Representation in Qualitative Research, London: McGraw-Hill/Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier M. (2014) Qualitative content analysis. In: Flick U. (ed.) The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman I. (2013) Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences, 3rd edn. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E, Magilvy JK. (2011) Qualitative rigor or research validity in qualitative research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing 16(2): 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi M, Jones J, Turunen H, et al. (2016) Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 6(5): 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. (2013) Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences 15(3): 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eerde W, Thierry H. (1996) Vroom's expectancy models and work-related criteria: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 81(5): 575. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom VH. (1964) Work and Motivation, New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom VH. (2005) On the origins of expectancy theory. In: Smith KG, Hitt MA. (eds) Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 239–258. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wildemuth BM. (2009) Qualitative analysis of content. In: Wildemuth B. (ed.) Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science, Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, pp. 308–319. [Google Scholar]