Abstract

Background

The number of people requiring end-of-life care provision in care homes has grown significantly. There is a need for a systematic examination of individual studies to provide more comprehensive information about contemporary care provision.

Aim

The aim of this study was to systematically review studies that describe end-of-life care in UK care homes.

Method

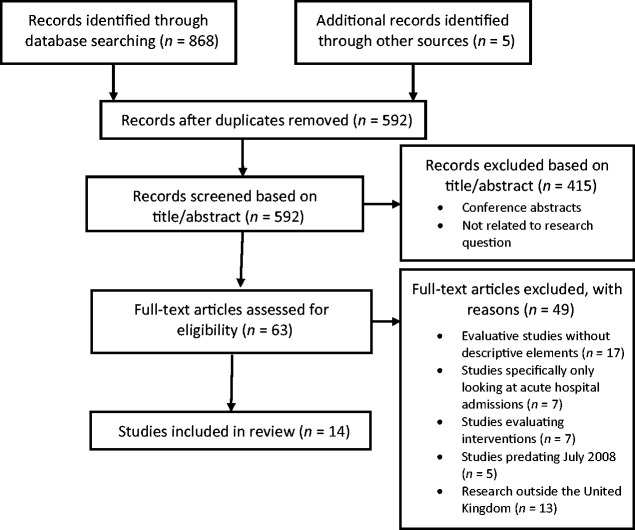

A systematic PRISMA review of the literature published between 2008 and April 2017 was carried out. A total of 14 studies were included in the review.

Results

A number of areas of concern were identified in the literature in relation to the phases of dying during end-of-life care: end-of-life pre-planning processes; understandings of end-of-life care; and interprofessional end-of-life care provision.

Conclusions

Given that the problems identified in the literature concerning end-of-life care of residents in care homes are similar to those encountered in other healthcare environments, there is logic in considering how generalised solutions that have been proposed could be applied to the specifics of care homes. Further research is necessary to explore how barriers to good end-of-life care can be mitigated, and facilitators strengthened.

Keywords: advance care planning, end-of-life care, interprofessional practice, nursing homes, palliative care, residential homes

Introduction

Due to an increasing ageing population in the UK, the number of older people who are cared for and dying in care homes is increasing significantly (Gomes and Higginson, 2008; Office for National Statistics, 2017). Therefore, the number of people requiring end-of-life (EoL) care provision in institutions that cater largely for the older person has grown significantly. It is also important to understand that most people would prefer to die at home, and for permanent care home residents the care home is their home, making it for most their preferred place of death (National End of Life Care Intelligence Network, 2012).

EoL care for older adults aims to support and comfort individuals with a progressive chronic illness from which they are dying in the last stages of their life. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality standard for EoL care for adults mandates that

high-quality care … should contribute to improving the effectiveness, safety and experience of care for adults approaching the end of life and the experience of their families and carers. This will be done in the following ways, regardless of condition or setting:

Enhancing quality of life for people with long-term conditions.

Ensuring that people have a positive experience of (health) care. (NICE, 2011)

The care provided should acknowledge spiritual, cultural and personal beliefs and support both family and friends during and after the period of bereavement (Fisher et al., 2000).

Ensuring dignity and care quality at the end of life are key priorities of EoL care strategies and policies across the UK (Department of Health, 2008; Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, 2010; Scottish Government, 2015; Welsh Government, 2017). These key documents have helped improve EoL care delivery across the board while also highlighting areas that still require development. For example, there are persisting levels of inappropriate admissions from care homes to hospitals for residents at the end of their lives (Mason et al., 2016), and less than optimal levels of integrated working between care homes and external services (Davies et al., 2011). However, given the absence of an overall view of current practice in UK care homes, there is a need for a systematic examination of individual studies to provide more comprehensive information about contemporary EoL care provision. The following review aims to achieve this by synthesising the descriptive elements of the literature in the field to uncover how EoL care is being delivered in UK care homes.

Methods

Preliminary searches were conducted using the EBSCO database. This provided insight into key terminology and relevant databases. Following on from the preliminary search, four main databases were systematically searched: ScienceDirect, MEDLINE, PSYCINFO and CINAHL. These databases were included because they had been identified in the preliminary search as containing the journals relevant to the research topic. Boolean techniques (see Table 1) were used to ensure no relevant literature was missed in the search strategy (Boland et al., 2014; Gerrish and Lathlean, 2015). Using this search strategy, the key components were entered into the database with their alternative subject headings.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| Element | Alternatives |

|---|---|

| 1. ‘End-of-life care’ | Pallia* ‘Terminal care’ |

| 2. ‘Care home*’ | ‘Nursing home*’ ‘Residential home*’ ‘Long term care facili*’ |

| 3. ‘United Kingdom’ | ‘United Kingdom’ UK England ‘Great Britain’ GB Wales Scotland ‘Northern Ireland’ |

| Boolean operators | 1. ‘End of life care’ OR Pallia* OR ‘Terminal care’ |

| 2. ‘Care home*’ OR ‘Nursing home*’ OR ‘Residential home*’ OR ‘Long term care facili*’ | |

| 3. ‘United Kingdom’ OR UK OR England OR ‘Great Britain’ OR GB OR Wales OR Scotland OR ‘Northern Ireland’ |

(Asterisk) represents any string of characters used in truncation.

The search was conducted on 25 April 2017, with the exclusion and inclusion criteria applied (see Table 2). The search also included manual searching of the reference lists of papers and hand searching the grey literature. The search was limited to papers published after the date of the EoL care strategy (Department of Health, 2008), which has heavily influenced the contemporary focus of policy and practice (NHS England, 2014). A range of study types, including both qualitative and quantitative evidence, was sought to explore how EoL care is currently being delivered in care homes in the UK. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (2014) frameworks were applied but no studies were excluded on this basis; CASP scores can be found in Table 3.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Studies must include a descriptive element regarding the nature of EoL care in care homes | To ascertain how EoL care is currently being delivered in care homes in the UK |

| Must be UK based | EoL care policy and guidelines are national-specific, and this study is specific to UK care homes |

|

| |

| Exclusion criteria |

Rationale |

| Pre-dates 2008 | July 2008 was the date of a seminal policy publication which significantly changed the focus of EoL care delivery and research in the UK |

| Includes an EoL intervention | Studies exploring interventions which describe EoL care in the context of the intervention thus may not be representative of practice |

| Studies specifically only exploring the acute hospital setting | This review is focused on exploring the nature of EoL care in care homes, not acute services |

EoL: end-of-life.

Table 3.

Selected studies.

| Study | Aim | Study type | Methods and participants | Results | Quality scorea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barclay et al. (2014) | Aim: To describe care home residents’ trajectories to death and care provision in their final weeks of life | Mixed method design | Case note reviews and interviews with residents, care home staff and healthcare professionals. Location: six residential care homes in three English localities | For some care home residents there was an identifiable period when they were approaching EoL and planned care was put in place. For others, death came unexpectedly or during a period of considerable uncertainty, with care largely unplanned and reactive to events | 15/20 16/22 |

| Froggatt et al. (2009) | Aim: To describe current advanced care planning practice in care homes for older people | Mixed method design | The study used questionnaire surveys (n = 213) with care home staff, and 15 qualitative interviews with care home managers | Advanced care planning helped inform care home staff’s EoL care decisions. However, the number of advanced care plans completed by residents varied | 15/20 18/22 |

| Goddard et al. (2013) | Aim: To explore the views of care home staff and community nurses on providing EoL care in care homes | Qualitative | Qualitative interviews conducted with 80 care home staff and 10 community nurses. Care homes providing care for older people (65 years or older) in two London boroughs took part in the study | Care home staff acknowledged that improvements in their skills and the resources available to them were needed to manage EoL care effectively | 17/20 |

| Handley et al. (2014) | Aim: To describe the expectations and experiences of EoL care of older people in care homes | Mixed method design | 121 residents from six care homes in the east of England were tracked: 63 residents, 30 care home staff with assorted roles and 19 NHS staff from different disciplines were interviewed and the case notes of residents were analysed | An ongoing lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities in providing EoL care, and doubts from care home and primary healthcare staff about their capacity to work together was uncovered | 16/20 14/22 |

| Kinley et al. (2014) | Aim: To identify the care currently provided to residents dying in UK nursing care homes | Mixed method design | Review of case notes took place for study participants who were residents who had died in 38 nursing care homes in southeast England over a 3-year period | Nursing care homes have established links with some external healthcare providers. These links included the GP, palliative care nurses and physiotherapy. However, with 56% of residents dying within a year of admission these links need to be expanded | 16/20 17/22 |

| Kupeli et al. (2016b) | Aim: To explore the context, mechanisms and outcomes for providing good palliative care to people with advanced dementia residing in UK care homes from the perspective of health and social care providers | Qualitative | Qualitative interviews with 14 health and social care professionals including care home managers, commissioners for older adults’ services and nursing staff | Changes to the care home environment are necessary to promote consistent, sustainable high quality EoL dementia care. For example, how care staff understand and use advanced care plans | 16/20 |

| Kupeli et al. (2016a) | Aim: To improve our understanding of healthcare professionals’ attitudes and knowledge of the barriers to integrated care for people with advanced dementia | Qualitative | Qualitative interviews were carried out with 14 healthcare professionals including care home managers, care assistants and nurses | Barriers to effective EoL care included poor relationships between care homes and external services, care home often felt undervalued by external healthcare professionals | 16/20 |

| Lawrence et al. (2011) | Aim: To define and describe good EoL care for people with dementia and identify how it can be delivered across care settings in the UK | Qualitative | Qualitative interviews were conducted with 27 bereaved family carers and 23 care professionals recruited from the community, care homes and general hospitals | The data reveal key elements of good EoL care and that staff education, supervision and specialist input can enable its provision | 14/20 |

| Livingston et al. (2012) | Aim: To examine barriers and facilitators to providing effective EoL care for people with dementia in care homes | Qualitative | Qualitative interviews of 58 staff in a 120-bed nursing home where the staff and the residents’ religion differed were carried out | Care staff, nurses and doctors did not see themselves as a team and communicated poorly with relatives about approaching death. The staff used opaque euphemisms and worried about being blamed | 16/20 |

| Mathie et al. (2012) | Aim: To explore the views, experiences and expectations of EoL care among care home residents to understand key events or living in a care home | Qualitative | The paper draws on the qualitative interviews of 63 care home residents who were interviewed up to three times over a year | The study highlighted the importance of ongoing discussions with care home residents and their relatives | 15/20 |

| Mitchell and McGreevy (2016) | Aim: To determine and describe care home managers’ knowledge of palliative care | Quantitative | 56 care home managers (all nurses) completed a validated questionnaire that is used to assess a nurse’s knowledge of palliative care | The average score was 12.89 correct answers out of a possible 20 (64.45%). This study uncovered a need to develop care home managers’ knowledge of palliative care | 13/22 |

| Ong et al. (2011) | Aim: To understand better and gain deeper insight into the reasons/rationales that leads to a decision to admit a care home resident to hospital | Quantitative | Questionnaires were used to explore current practice in care homes; eight care homes were included | Lack of advance care plans, and poor access to GPs was uncovered as being the most common reason leading to admission | 16/22 |

| Stone et al. (2013) | Aim: To explore and describe the experiences of stakeholders initiating and completing EoL care discussions in care homes | Qualitative | A qualitative descriptive study was carried out in three nursing care homes. Qualitative interviews were conducted with the resident, a family member, and the staff member | Staff understanding of advanced care planning varied, affecting the depth of their discussions. Education was identified as being important, and role modeling advance care planning enabled a member of staff to develop their skills and confidence | 14/20 |

| Wye et al. (2014) | Aim: To discuss and evaluate EoL services in care homes in English counties | Mixed method design | Data collection included documentation (e.g. referral databases), 15 observations of services and interviews with 43 family carers and 105 professionals | Results showed that time restrictions and poor staffing levels forced care home staff to rush and miss out or avoid vital aspects of EoL, such as discussions with residents and family | 16/20 17/22 |

Qualitative studies were scored out of 20 because one screening question was not relevant to the study design. Quantitative studies were scored out of 22, and mixed method studies were scored on both their qualitative and quantitative elements, so they have two scores.

EoL: end-of-life.

Due to the methodological diversity of research conducted in this area, this systematic review adopted a mixed-method synthesis. Mixed research synthesis aims to integrate the results from both qualitative and quantitative studies in a shared sphere of empirical research (Sandelowski et al., 2006). Moreover, mixed-method synthesis has the potential to enhance both the significance and utility for practice by bringing together qualitative and quantitative studies to get ‘more’ of a picture of a phenomenon by looking at it from a number of different perspectives (Pope et al., 2007; Sandelowski et al., 2006). Analysis was carried out by means of thematic synthesis, a method that is recommended when the findings have relevance to practice and policy (Booth et al., 2016).

Summary of included literature

A total of 14 studies were included: seven qualitative, five mixed-method designs and two quantitative studies. Participants for the qualitative and quantitative studies included healthcare professionals, general practitioners (GPs), carers, care home managers, bereaved relatives, and residents in care homes. The care homes included both residential and nursing homes, and all of the studies were conducted in the United Kingdom. All of the included studies had descriptive elements that described the nature of EoL care in UK care homes. Most of the selected literature explored EoL care from the healthcare professionals’ perspective. See Figure 1 for a summary of the selection stages.

Figure 1.

Selection flow chart.

The seven included qualitative studies used the data collection method of in-depth semi-structured interviews (Goddard et al., 2013; Kupeli et al., 2016a, 2016b; Lawrence et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2012; Mathie et al., 2012; Stone et al., 2013). Four of the five included mixed-method studies also utilised one-to-one individual interviews (Barclay et al., 2014; Froggatt et al., 2009; Handley et al., 2014; Wye et al., 2014). Wye et al. (2014) used observations and analysed documentation (referral databases), and Froggatt et al. (2009) used surveys alongside interviews. Kinley et al. (2014) analysed the case notes and daily records of all residents who died in the participating eight care homes from 2008 to 2011. Handley et al. (2014) and Barclay et al. (2014) both used a mixed-method approach to analyse care home notes as well as qualitative interviews.

Both quantitative papers included the use of questionnaires. Mitchell and McGreevy (2016) and Ong et al. (2011) both used questionnaires to explore aspects of EoL care practice in care homes.

Results

A total of 868 records were retrieved through initial database searches, and a further five records were uncovered by hand searching and were screened for relevance (Figure 1). A total of 276 records were excluded at stage 1 through duplication, and a further 415 records were excluded based on title/abstract screening as they did not focus on the nature of EoL care in UK care homes. The remaining 63 full text papers were then assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2), resulting in a further 49 papers being excluded. Finally, a total of 14 papers were selected for review (Figure 1). Following the data extraction procedure described above, two researchers (AS and SP) used thematic analysis (Sandelowski et al., 2006) to synthesise the final selection of papers. Thematic synthesis of identified findings revealed four key themes. These key themes are the phases of dying during EoL care, EoL pre-planning processes, understandings of EoL care, and interprofessional EoL care provision.

The phases of dying during EoL care

While not described in every study, the phases of dying during EoL care were frequently acknowledged as impacting on the provision and delivery of EoL care (Barclay et al., 2014; Handley et al., 2014; Kinley et al., 2014). The phases of dying during EoL care were described as the different stages or trajectories that residents went through when nearing death. In particular, the literature described how care home staff sometimes found it difficult to discriminate between residents who were near death and residents who were not. This impacted on EoL care provision by preventing care home staff from planning and ‘readying’ themselves for the end stages of residents’ lives (Barclay et al., 2014; Handley et al., 2014; Kinley et al., 2014). This was particularly prevalent for residents on unclear or complex death trajectories (Barclay et al., 2014; Handley et al., 2014; Kinley et al., 2014).

Handley et al. (2014), Barclay et al. (2014) and Kinley et al. (2014) each used similar research methods to examine the phases of dying; however, the scale of each study varied considerably. Barclay et al. (2014) conducted a mixed-method study. Residents, care home staff and healthcare professionals were interviewed and residents’ case notes were reviewed. The study described trajectories to death, specifically how different illness types and death trajectories could influence healthcare staff’s ability to carry out appropriate EoL care. It was observed that certain illnesses could lead to hospital admissions more commonly than others with more clear trajectories. However, these findings are limited because, despite consent being obtained from 121 residents, the study focused mainly on only 23 participants who died during the 12 months of data collection. In addition, the study stated that care home staff and healthcare professionals were interviewed, but does not detail how many.

Despite their study being small in scale, the results from Barclay et al. (2014) supported similar findings by Handley et al. (2014) and Kinley et al. (2014). Handley et al. (2014) reported how different death trajectories, particularly when unclear or unexpected, could impact on care home staff’s decisions, particularly regarding admissions to hospital at the EoL stage of care. The methodology of the study by Handley et al. (2014) was similar to that used by Barclay et al. (2014). Handley et al. (2014) used a mixed-method design utilising interviews and case note reviews. A total of 63 residents, 30 care home staff and 19 NHS healthcare staff from different disciplines were interviewed. Handley et al. (2014), who only included care homes without on-site nursing provision, suggested that registered and non-registered care home staff may react differently when making decisions at the EoL stages. However, Kinley et al. (2014) and Barclay et al. (2014) found similar results in care homes with and without on-site nursing.

Kinley et al. (2014) also reported similar findings, describing stages of death that ranged from ‘dwelling’, which represents slow expected death, to ‘sudden’, which represents unexpected death. They also noted that these different death trajectories could influence staff’s decision-making ability. The study by Kinley et al. (2014) examined the case notes of residents who had died within 38 care homes over a 3-year period, which equated to 2444 residents, a considerably larger sample than either Barclay et al. (2014) or Handley et al. (2014). They used the case notes to extract specific data, including demographics, diagnoses, use of acute services, place and type of death and use of EoL care tools (e.g. advance care plans (ACPs) and EoL documentation).

Each of the three studies had a slightly different way of describing the phases of EoL care. Handley et al. (2014) referred to them as death trajectories ranging from ‘clear’ to ‘unclear’. Barclay et al. (2014) used terms ranging from ‘anticipated’ to ‘unpredictable’, while Kinley et al. (2014) described the stages of death ranging from ‘dwelling’ to ‘sudden’. Despite the different terminology, the overarching concept is consistent throughout, which is that the phases of dying experienced during EoL care seem to follow similar patterns ranging from steady decline to a complex and unpredictable trajectory.

All three of the studies also described how lack of awareness of the phases of dying during EoL care can often result in care home staff making ‘reactive’ or ‘in the moment’ decisions (Barclay et al., 2014; Handley et al., 2014; Kinley et al., 2014). For example, Barclay et al. (2014) described how, particularly with ‘uncertain’ or ‘unclear’ dying trajectories, staff tended to panic when the resident unexpectedly deteriorated and admitted the resident to hospital, where they died inappropriately. However, Barclay et al. (2014) also reported how interprofessional team working can help provide support in these moments. This interprofessional team work will be discussed in a later theme.

Summary of main findings

Different phases/trajectories of death during EoL care were acknowledged in the literature.

The phases/trajectories of death were recognised as impacting on EoL care.

Healthcare staff’s understanding and knowledge of these phases was shown to influence decision-making when providing EoL care.

Sudden and unexpected death trajectories often caused healthcare staff to panic and admit the resident to hospital.

EoL pre-planning processes

Pre-planning processes were identified as playing a key role in the provision of EoL care, particularly in aiding staff to adhere to residents’ wishes. For example, ACPs were often used by a range of healthcare staff to communicate residents’ preferences, notably preference for place of death, to other healthcare staff and external services such as GPs and other out-of-hours services (Froggatt et al., 2009; Goddard et al., 2013; Kupeli et al., 2016a; Livingston et al., 2012; Mathie et al., 2012; Ong et al., 2011; Stone et al., 2013).

Pre-planning tools such as ACPs also appeared to focus on outcomes and prepare care home staff for the different phases of dying during EoL care by providing information necessary for appropriate, personalised and planned EoL care. However, it was equally conveyed throughout the literature that engaging in EoL pre-planning care discussions with residents and relatives was commonly avoided by care home staff (Froggatt et al., 2009; Handley et al., 2014; Ong et al., 2011; Wye et al., 2014).

Froggatt et al. (2009) found that the use of ACPs can further help reduce reactive decisions during EoL care. Froggatt et al. (2009) conducted a mixed-method study which specifically described and explored the use of ACPs. Froggatt et al. (2009) used questionnaires (n = 213) and interviews (n = 15) to collect data from care home managers. Thematic analysis of this paper uncovered how ACPs can help staff focus on structured pre-planned processes or instructions to help inform their EoL care decisions.

The findings of Froggatt et al. (2009) were supported by those of Ong et al. (2011), who conducted a study of eight care homes to explore reasons for admitting residents to hospital at the end of their lives. The study found that out of 340 patients admitted to hospital from care homes, 40% died within 24 hours, suggesting a high level of less appropriate admissions. The study suggested that poor communication between care home staff and patients and relatives led to a lack of pre-planning documentation, which contributed to decisions on admissions at the end of life.

The consequences of not having ACPs in place was further supported by Kupeli et al. (2016b), who explored the provision of EoL care in care homes for residents who have dementia. The study interviewed a range of care home staff (n = 8) and healthcare staff working within the National Health Service (NHS) (n = 6). The results indicated that study participants viewed ACPs as a method to reduce inappropriate hospital admissions from the care home and reduce unnecessary treatments (Kupeli et al., 2016b). However, Kupeli et al. (2016b) reported that these positive views and understandings of ACPs may not be representative of the views of care home staff throughout the whole care home sector across the country. Furthermore, these findings may not represent the routine practice for the wider care home demographic as the study only explored the care of patients with dementia.

Livingston et al. (2012) exemplified the statement of Kupeli et al. (2016b) that positive practices may not be applied throughout the whole care home sector. Livingston et al. (2012) conducted a qualitative study that interviewed 58 care home staff in a 120-bed care home which provided both residential and nursing care. The interviews continued until data saturation was reached. The study aimed to examine the barriers to and facilitators of good EoL care for residents with dementia. The results found that care staff, nurses and doctors did not see themselves as a team, but rather focused on their separate responsibilities. As a result they communicated poorly with each other, residents and their families about approaching death. The study also reported that staff members were unaware of the benefits that ACPs could provide at the end of life for residents and their families. It was also reported that staff were worried about being blamed for the residents’ potential death, and therefore tended to ignore pre-planning information and send the patient for admission to hospital based on fear of the consequences of not doing so.

Similar findings were evidenced by Stone et al. (2013), who carried out a qualitative descriptive study, interviewing 28 participants. The participants ranged from residents, family members and staff members from three nursing homes. The study described how care home staff would commonly avoid discussions about death and pre-planning, despite residents themselves often being willing to engage in such discussions. They contended that it was staff’s lack of understanding of ACP and pre-planning documentation that led to their lack of engagement, alongside their perceptions that residents did not want to discuss ACP. The findings of Stone et al. (2013) are backed up by larger research projects such as Froggatt et al. (2009), Mitchell and McGreevy (2016) and Handley et al. (2014). Froggatt et al. (2009) suggested that illness type and trajectory may be part of the reason why EoL care discussions did not take place. They discussed how residents with communication and cognition problems often found it hard to engage in EoL care discussions, and how care home staff themselves found it difficult to engage with residents in this category.

Handley et al. (2014) also explored how care home staff engaged in EoL discussions with residents. They found that all staff who were interviewed recognised the importance of initiating pre-planning discussions, particularly regarding the preferred place of death. However, despite this understanding of the overall benefit of pre-planning discussions, they reported that care home staff in two homes expressed hesitancy and uncertainty about how to start discussions with residents about death. In particular, they were unsure when the right time to start discussions was, and how to involve family members in these discussions.

This lack of EoL care discussions was also acknowledged by Wye et al. (2014), who conducted a qualitative realist evaluation which aimed to evaluate EoL services in English care homes. Methods of data collection included 15 observations of services, interviews with family carers (n = 43) and healthcare professionals (n = 105) and analysis of documentation. The authors’ results supported findings that suggest that EoL care discussions are often neglected in practice. Wye et al. (2014) noted how time restrictions and poor staffing levels forced care home staff to rush and miss out or avoid vital aspects of EoL care, such as discussions with residents and family regarding pre-planning and death.

Despite the infrequency of EoL care discussions, Goddard et al. (2013) found that care home staff and community nurses did recognise the importance of establishing EoL care preferences and encouraging advance care planning discussions. However, the study acknowledged it was small in scale and only explored practice in two care homes, which limited the generalisability of its findings.

Mathie et al. (2012) carried out a qualitative study which interviewed 63 care home residents recruited from six UK care homes. The study highlighted the importance of ongoing discussions with care home residents and their relatives, revealing that these discussions can produce opportunities to talk about dying and pre-planning. Furthermore, the study revealed that facilitating these discussions earlier rather than later may be important, particularly for residents with dementia (Mathie et al., 2012).

Summary of main findings

Evidence suggests that good practice is not always applied throughout the care home sector in the UK.

It is important to facilitate ongoing discussions with care home residents and their families throughout their time in the care home.

Engaging in EoL care discussions with residents and family members to gather information for pre-planning processes was acknowledged as lacking in care homes.

The most commonly used pre-planning tool appeared to be ACPs.

ACPs were an effective tool in disseminating vital preferences of residents among interprofessional healthcare staff and external services.

ACPs improved decision-making by helping staff prepare and plan for unexpected or sudden death trajectories experienced during EoL care.

Understandings of EoL care

Varying understandings of and perspectives about EoL care among staff were evidenced, which seemed to be determined by profession and care setting and context (Goddard et al., 2013; Handley et al., 2014; Lawrence et al., 2011; Mitchell and McGreevy, 2016). However, some studies found evidence of a general ethos towards EoL care among care home staff that differed from that of professionals working in other settings. That ethos involved a more holistic approach to care than was found elsewhere.

Lawrence et al. (2011) conducted a qualitative study using interviews to explore how EoL care was experienced from the perspectives of bereaved family carers (n = 27) and care professionals (n = 23). Participants were recruited from care homes, general hospitals and the community. The wide range of participants uncovered how understandings of EoL care varied among these different professional groups in different care settings. For example, it was found that in care home settings staff understood EoL care as holistic care that involved forming bonds with residents, and they emphasised communication with both the dying resident and their families. However, this understanding was largely absent among general hospital staff, who had a much more detached, task-focused understanding of EoL care provision. In addition, the study revealed that bereaved relatives particularly valued this ‘close relationship’ with care home staff and they tended to see it as a key determinant of good quality EoL care.

Differences in attitude were also found between care home and community staff. Goddard et al. (2013) conducted a qualitative study which used interviews to explore the views of care home staff (n = 80) and community nurses (n = 10) on providing EoL care in care homes. The study described how care home staff and community nurses had both similar and differing views of EoL care. For example, both participant groups understood that a caring approach is required and that emotional support should be provided to relatives both before and after the bereavement. However, differences in the understanding of EoL care were also apparent. For example, care home staff believed that EoL care should start early on and also tended to favour the use of ACPs early on. In contrast, community nurses believed that EoL care should only start when the resident is notably diagnosed as being at the end of life or the terminal phase.

Appreciation of participants’ understandings of EoL care was complicated by the fact that many studies did not distinguish between palliative care and EoL care (Barclay et al., 2014; Lawrence et al., 2011; Mitchell and McGreevy, 2016). Palliative care is a non-curative intervention designed to provide patients with comfort and support, irrespective of their time left to live (NICE, 2011; World Health Organization, 2011). EoL care is a subset of palliative care and is confined to the last days/weeks of life (Fisher et al., 2000; National Council for Palliative Care, 2006). However, the commencement of the EoL care stage within the process of palliative care is unclear, and thus is left open to individual interpretation (Goddard et al., 2013; Lawrence et al., 2011; Mitchell and McGreevy, 2016).

Mitchell and McGreevy (2016), using questionnaires completed by 56 care home managers, found that their overall knowledge of palliative care was variable. It was good in some areas such as therapeutic pain-relieving strategies, but poor in others such as understanding the underlying philosophy of palliative care. However, the study only explored understandings of palliative care and thus did not explore how staff discriminate EoL care from palliative care. Nonetheless, as stated above, EoL care is a subset of palliative care, therefore staff’s wider understandings of palliative care can provide useful insights into the delivery of EoL care. Moreover, the exclusion of other care staff in this study meant that variations in understanding between professional groups could not be explored.

Handley et al. (2014) support the findings of Lawrence et al. (2011) and Mitchell and McGreevy (2016) with regard to varying levels of understanding of palliative and EoL care. Moreover, understandings of EoL care have been shown to vary depending on the different death trajectories discussed earlier. It was reported that towards the end stages of life, care home staff often presented differing understandings and responses. For example, when a resident’s death trajectory was sudden or unexpected, care home staff tended to want to prolong life and admit the resident to hospital (Barclay et al., 2014; Handley et al., 2014). These variations in understanding seemed to be particularly prevalent in care homes without on-site nursing provision (Handley et al., 2014).

Summary of main findings

Understanding of EoL care can influence how healthcare staff provide care.

Understanding of EoL care seems to vary in care homes according to profession, care setting and context.

A lack of discrimination between EoL and palliative care may influence healthcare staff’s understanding of when to start EoL care.

Interprofessional EoL care provision

Interprofessional EoL care provision manifested itself as a range of professional groups working together to provide EoL care to residents and their families in care homes. In particular, it was frequently conveyed that GPs and district nurses (DNs) worked together with care home staff, residents and families to share and discuss decisions about the management and planning of EoL care. For example, GPs often needed input from DNs, family, care home staff and residents to ascertain key information, for example preference for place of death (Barclay et al., 2014; Froggatt et al., 2009; Handley et al., 2014; Kinley et al., 2014; Kupeli et al., 2016a; Livingston et al., 2012; Wye et al., 2014). Despite this interprofessional approach, uncertainty was expressed by healthcare staff in relation to who should be involved in EoL care provision and at what stages (Handley et al., 2014; Kupeli et al., 2016a).

The large study by Kinley et al. (2014) found that interprofessional working played an important role in EoL care provision. For example, the authors note that GPs and DNs often relied on each other for information and support. However, the exclusive reliance of this study on case note examination meant that it was unable to capture the in-depth experiences of interprofessional care provision. That said, the findings of Kinley et al. (2014) were supported by both Barclay et al. (2014) and Handley et al. (2014), who used interviews alongside the examination of case notes.

For example, Barclay et al. (2014) reported how GP support was essential in enabling interprofessional collaboration and teamwork. In particular, care home staff stated that they felt supported by the presence of a GP. This finding was echoed by Handley et al. (2014) and Kinley et al. (2014), who also found that collaborative working helped coordinate decisions and prevent reactive approaches to care by helping care home staff feel supported and part of a team.

Nonetheless, Handley et al. (2014) described how staff members involved in the provision of EoL care were often unclear about who was responsible for providing particular aspects of that care. For example, uncertainty was expressed about who should initiate and be involved in EoL discussions. Handley et al. (2014) found that this uncertainty often resulted in residents not being formally diagnosed as nearing the end of life. Uncertainty about who should be involved in EoL care and lack of formal diagnoses for residents nearing the end of life tended to be particularly impactful in a crisis, heavily influencing decisions about whether to admit residents to hospital (Handley et al., 2014).

This finding was supported by Froggatt et al. (2009), who observed that care home staff were unclear about who should engage in EoL discussions and when. They recommended that a more discriminating approach should be taken with regard to who is responsible for which elements of EoL care discussions. Barclay et al. (2014) and Kinley et al. (2014) noted that clear interprofessional working arrangements were essential in preventing unnecessary admissions to acute services.

Wye et al. (2014) also supported the idea that interprofessional teamwork is an essential part of EoL care. Despite this, they found that important members of the team, such as GPs and DNs, who were not based in care homes, were frequently not present at crucial moments, which undermined the level of support that care home staff felt they were given (Barclay et al., 2014; Handley et al., 2014; Kinley et al., 2014; Ong et al., 2011).

Similar findings were highlighted by Kupeli et al. (2016a), who explored the attitudes of a range of healthcare staff (n = 14). These professionals ranged from commissioners to home managers. The study revealed a fragmented approach to care. In particular, poor relationships between care home staff and external healthcare professionals were evidenced. Care home staff who participated in the study commonly highlighted that they felt undervalued by external healthcare professionals (Kupeli et al., 2016a). Handley et al. (2014) also reported that care home staff often felt their expertise and knowledge was undervalued.

Furthermore, interaction between care home staff and specialist palliative care services appeared to be limited. Lawrence et al. (2011) observed limited access to palliative care services and acknowledged this as a common phenomenon throughout the care home sector. However, when available, it was found that input from specialist palliative care services provided valuable instruction and support, helping to instill staff with the confidence to carry out and manage EoL care themselves. These findings were echoed by Handley et al. (2014), who added that care homes without on-site nursing provision tended to rely more heavily on external palliative care services for support in carrying out EoL care. However, Ong et al. (2011) found that access and communication between palliative care services was equally poor in both nursing and residential care homes.

Summary of main findings

Interprofessional collaboration is an essential part of providing EoL care; however, poor relationships between care home staff and external services were highlighted as impacting on interprofessional collaboration.

Support from a range of professionals, notably GPs and DNs, helped care home staff feel part of a team and better able to make decisions.

It was noted that staff expressed uncertainty as to who should be involved in EoL care and at what stages, which was found to be particularly impactful in a crisis.

A lack of interaction between specialist palliative care services and care homes was highlighted.

Discussion

A number of areas of concern were identified in the literature in relation to the phases of dying during EoL care: EoL pre-planning processes; understandings of EoL care; and interprofessional EoL care provision. However, it is important not to exaggerate either the extent of the problems currently pertaining in care homes or the exceptionality of EoL care in care homes as compared to other healthcare contexts.

In addition, many of the findings referred to variations in care, which means that excellent care is already being delivered in some locations. That is not just important for those who are currently receiving a high standard of care, but it also means that there are exemplars that can be used to support the rolling out of good practice across the sector.

Even in an area such as pre-planning for the end of life, where there is considerable evidence that staff engagement in the activity is far less than it should be, there is also evidence that staff members appreciate the benefits of pre-planning, and only avoid engaging in it because they lack the confidence and knowledge to do so. This is important because it means that the problem is not caused by staff resistance to new practice, which implies that if the appropriate support is provided, then the successful implementation and sustainability of pre-planning more widely across the sector is achievable.

It should also be noted that many of the problems identified here are not unique to care homes. Thus, for example, care home staff members are not alone in finding difficulty in caring effectively for residents who have complex EoL trajectories. The lack of prognostic clarity that is associated with chronic life-limiting diseases, such as non-malignant respiratory disease which are characterised by intermittent acute-on-chronic episodes, entails a significant challenge to EoL care for healthcare professionals, regardless of the care setting or professional background (Crawford et al., 2013; McVeigh et al., 2017).

Similarly, the failure of healthcare professionals to engage in advanced care planning is a wider problem that has also been evidenced in acute care settings. Thus, for example, Heyland et al. (2013) found that in just 30% of cases did acute hospital documentation accord with the expressed preferences of elderly patients at high risk of dying. Part of the problem is a general reluctance by healthcare professionals to engage in difficult conversations with those in their care (Millar et al., 2013).

Generalist healthcare practitioners’ lack of understanding of EoL care, and consequent gaps in their confidence and competence, is an issue that, while improving, has long plagued palliative care. This issue has been identified in relation to both medicine (Sanawani et al., 2008) and nursing (Wallace et al., 2009). Part of the confusion relates to variable understandings of what is meant by EoL care, and how it relates to palliative care (Shipman et al., 2008). Once again, the problems faced by care home practitioners are shared across the field of generalist palliative care.

Finally, there is the issue of interprofessional practice, and specifically the utilisation of specialist palliative care practitioners by healthcare teams providing EoL care. Once again, the lack of specialist support to care homes is in line with findings in relation to the care of dying older people in acute hospitals. Gardiner et al. (2011) observed that specialist palliative care services remain predominantly focused on cancer, which means that older people who are more likely to have non-malignant diseases are disadvantaged in their access to these services.

Not only are the problems experienced by care homes similar to those of other sectors, in some ways they have taken a leading role in the improvement of EoL care. Thus the Gold Standards Framework (GSF) accreditation system started with care homes in 2004, and subsequently expanded to domiciliary care, community hospitals and primary care (http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/history), with phase 1 of acute hospital accreditation only starting in 2015 (http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/accredited-acute-hospitals).

Limitations

We recognise that the difference in contexts as a result of including studies that used nursing and residential care homes, which varied in size, structure and location, and that this may reduce the generalisability of the review. In addition, it is important to note that studies introducing an intervention were excluded because these related to specific initiatives rather than standard care.

However, existing EoL care interventions may already be implemented in the care homes used in the studies. In particular, some of the studies included care homes that were GSF accredited (Barclay et al., 2014), while others included care homes that were in the process of being accredited (Handley et al., 2014; Kinley et al., 2014; Stone et al., 2013). Nonetheless, in other studies it was unclear whether the care homes used the GSF as it was not mentioned (Goddard et al., 2013; Kupeli et al., 2016a, 2016b; Livingston et al., 2012; Mathie et al., 2012; Mitchell and McGreevy, 2016; Wye et al., 2014). It was also apparent within two of the studies that participants mentioned using the GSF; however, the authors of these studies did not state which of the care homes they included used the GSF and which did not (Froggatt et al., 2009; Lawrence et al., 2011). Despite this, we feel that this review provides an enhanced understanding of the reviewed literature by providing comprehensive information about contemporary EoL care provision.

Conclusion

Given that the problems identified in the literature concerning EoL care of residents in care homes are similar to those encountered in other healthcare environments, there is logic in considering how generalised solutions that have been proposed could be applied to the specifics of care homes.

Dealing with the uncertain trajectories of some chronic illnesses requires a dynamic approach to EoL care that focuses on the changing needs of the individual (McVeigh et al., 2017; Murtagh et al., 2004). It also requires the additional skill of being able to manage uncertainty actively to minimise the anxiety it causes (Murtagh et al., 2004). All this implies the need for care home staff to be trained in the knowledge and skills required.

Making pre-planning a more uniform and utilised aspect of care in care homes also requires educational and practical support to ensure that staff are both competent and confident in undertaking the conversations required, and that they accurately record and communicate the decisions made by residents (Seymour et al., 2010). It also requires systematic implementation and monitoring within organisations (Molloy et al., 2000).

Both of the above conclusions underline the crucial link between the level of staff members’ knowledge about EoL care and the quality of care that they give (Sullivan et al., 2003), and the subsequent imperative that they are provided with the educational resources to gain that knowledge. However, education, training and knowledge may be insufficient if staff do not feel supported and confident to have difficult discussions with residents about the end of life (Hall et al., 2011). For example, the way in which care home staff may be viewed by others (family members) can influence care. In particular, the expectations of family members can often clash with staff expectations, resulting in staff and family members disagreeing about residents’ care needs (Utley-Smith et al., 2009). Therefore a change in culture, that is, the public expectations of care home staff and how they are viewed by others, may need to change in order to facilitate improvement (Hall et al., 2011; Utley-Smith et al., 2009).

Finally, the findings indicate that there is a need for the expansion of community specialist palliative care services, and that those services should have formalised links with care homes so that their support is available when required (Candy et al., 2009).

Given the nature of the issues identified in the literature, if these strategies are adopted across the sector, excellent EoL care can become a more consistent feature of care homes than the evidence suggests is currently the case. Due to the variations revealed in this review, further research is necessary to explore the effectiveness of EoL care interventions and strategies applied across the care home sector. In addition, given the heterogeneity of UK care homes, this review advocates that contextual depth be explored, specifically focusing on stakeholders’ experiences and interpretations of EoL care interventions and strategies in different care home contexts.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

Evidence suggests that there are variations in the quality of end-of-life care in care homes.

The main areas of concern that have been identified relate to the phases of dying during end-of-life care, end-of-life pre-planning processes, understandings of end-of-life care, and interprofessional care provision.

Interventions applied in other healthcare sectors to improve end-of-life care may also be effective in the care home context.

Further research is necessary to explore the effectiveness of end-of-life care interventions in the specific social, economic and organisational contexts within which care homes operate.

Biography

Adam Spacey is a full-time PhD student at Bournemouth University. His main areas of interest are end-of-life and palliative care. Alongside his academic responsibilities, Adam works as a bank radiographer for two NHS Hospital Trusts.

Janet Scammell is an experienced nurse academic, manager and practitioner. As a practitioner she worked in medical nursing settings. Her career in health care education spans 25 years in various roles including Director of Studies for Pre-Registration Nursing, Faculty Head of Learning and Teaching, Professional lead for adult and child nursing and currently lead for nursing research.

Michele Board is a Senior Lecturer in Nursing Older People, in the Faculty of Health & Social Sciences at Bournemouth University. Michele is passionate about the quality of care patients receive, and this influences all her teaching and research. She teaches on the undergraduate nursing course with a specific focus on nursing older people and dementia.

Sam Porter is a sociologist by academic training and a nurse by profession. His wide research interests reflect this combination. His main areas of interest are palliative and end-of-life care; supportive care for cancer survivors and carers; maternal and child health; the sociology of health professionals; and the use of arts-based therapies.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Barclay S, Froggatt K, Crang C, et al. (2014) Living in uncertain times: Trajectories to death in residential care homes. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 64(626): e576–e583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland A, Cherry MG, Dickson R. (2014) Doing a Systematic Review: A Student’s Guide, London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, et al. (2016) Guidance on choosing qualitative evidence synthesis methods for use in health technology assessments of complex interventions, York: York Research Database, University of York. [Google Scholar]

- Candy B, Holman A, Davis S, et al. (2009) Hospice care delivered at home, in nursing homes and in dedicated hospice facilities: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. International Journal of Nursing Studies 48(1): 121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford GB, Brooksbank MA, Brown M, et al. (2013) Unmet needs of people with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Recommendations for change in. Australia. Internal Medicine Journal 43(2): 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (2014) CASP Checklists. Available at: www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists (accessed 4 July 2017).

- Davies S, Goodman C, Bunn F, et al. (2011) A systematic review of integrated working between care homes and health care services. BMC Health Services Research 11(1): 320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2008) End of Life Care Strategy, London: The Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (2010) Living Matters, Dying Matters: A Palliative and End of Life Care Strategy for Adults in Northern Ireland. Available at: www.health-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/dhssps/living-matters-dying-matters-strategy-2010.pdf (accessed 21 November 2017).

- Fisher R, Ross M, MacLean M. (2000) A guide to end-of-life care for seniors, Ottawa: Health Canada. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froggatt K, Vaughan S, Bernard C, et al. (2009) Advance care planning in care homes for older people: An English perspective. Palliative Medicine 23(4): 332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner C, Cobb M, Gott M, et al. (2011) Barriers to providing palliative care for older people in acute hospitals. Age and Aging 2(1): 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish K, Lathlean J. (2015) The Research Process in Nursing (electronic resource), Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, Bournemouth University Library Catalogue. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard C, Stewart F, Thompson G, et al. (2013) Providing end-of-life care in care homes for older people: A qualitative study of the views of care home staff and community nurses. Journal of Applied Gerontology 32(1): 76–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes B, Higginson I. (2008) Where people die (1974–2030): Past trends, future projections and implications for care. Palliative Medicine 22: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall S, Goddard C, Stewart F, et al. (2011) Implementing a quality improvement programme in palliative care in care homes: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics 11(1): 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley M, Goodman C, Froggatt K, et al. (2014) Living and dying: Responsibility for end-of-life care in care homes without on-site nursing provision – a prospective study. Health and Social Care in the Community 22(1): 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D. (2013) Failure to engage elderly hospitalized patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Internal Medicine 173(9): 778–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinley J, Hockley J, Stone L, et al. (2014) The provision of care for residents dying in U.K. nursing care homes. Age & Ageing 43(3): 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupeli N, Leavey G, Harrington J, et al. (2016. a) What are the barriers to care integration for those at the advanced stages of dementia living in care homes in the UK? Health care professional perspective. Dementia (London) 17(2): 164–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupeli N, Leavey G, Moore K, et al. (2016. b) Context, mechanisms and outcomes in end of life care for people with advanced dementia. BMC Palliative Care 15: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence V, Samsi K, Murray J, et al. (2011) Dying well with dementia: Qualitative examination of end-of-life care. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science 199(5): 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G, Pitfield C, Morris J, et al. (2012) Care at the end of life for people with dementia living in a care home: A qualitative study of staff experience and attitudes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 27(6): 643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVeigh CM, Reid J, Larkin P, et al. (2017) The provision of generalist and specialist palliative care for patients with non-malignant respiratory disease in the North and Republic of Ireland: A qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care 17(1): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason E, Jenkins D, Williams M, et al. (2016) Unscheduled care admissions at end-of-life – what are the patient characteristics? Acute Medicine 15(2): 68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathie E, Goodman C, Crang C, et al. (2012) An uncertain future: The unchanging views of care home residents about living and dying. Palliative Medicine 26(5): 734–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar C, Reid J, Porter S. (2013) Refractory cachexia and truth-telling about terminal prognosis: A qualitative study. European Journal of Cancer Care 22(3): 326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell G, McGreevy J. (2016) Care home managers’ knowledge of palliative care: A Northern Irish study. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 22(5): 230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy DW, Guyatt GH, Russo R. (2000) Systematic implementation of an advance directive program in nursing homes. JAMA 238(11): 1437–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh F, Preston M, Higginson I. (2004) Patterns of dying: Palliative care for non-malignant disease. Clinical Medicine 4(1): 39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Palliative Care (2006) End of Life Care Strategy. The National Council for Palliative Care Submission. London. Available at: www.ncpc.org.uk/sites/default/files/NCPC_EoLC_Submission.pdf (accessed 4 July 2017).

- National End of Life Care Intelligence Network (2012) What do we know now that we didn’t know a year ago? New intelligence on end of life care in England, London: NHS. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2011) End of life care for adults: Quality standard. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs13/resources/end-of-life-care-for-adults-pdf-2098483631557 (accessed 19 June 2017).

- NHS England (2014) Actions for End of Life Care: 2014–16. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/actions-eolc.pdf (accessed 19 June 2017).

- Office for National Statistics (2017) An overview of the UK population, how it’s changed, what has caused it to change and how it is projected to change in the future. The UK population is also compared with other European countries. Available at: www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/mar2017 (accessed 3 July 2017).

- Ong A, Sabanathan K, Potter J, et al. (2011) High mortality of older patients admitted to hospital from care homes and insight into potential interventions to reduce hospital admissions from care homes: The Norfolk experience. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 53(3): 316–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C, Mays N, Popay J. (2007) Synthesizing Qualitative and Quantitative Health Evidence: A Guide to Methods, Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Sanawani H, Wenrich MD, Tonelli M, et al. (2008) Meeting physicians’ responsibilities in providing end-of-life care. Chest 133(3): 775–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Voils C, Barroso J. (2006) Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Research in the Schools 13(1): 29–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government (2015) Strategic Framework for Action on Palliative and End of Life Care 2016–2021. Available at: www.gov.scot/Resource/0049/00491388.pdf (accessed 21 November 2017).

- Seymour J, Almack K, Kennedy S. (2010) Implementing advance care planning: A qualitative study of community nurses’ views and experiences. BMC Palliative Care 9(4): 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman C, Gysels M, White P, et al. (2008) Improving generalist end of life care: National consultation with practitioners, commissioners, academics, and service users. BMJ 337: a1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone L, Kinley J, Hockley J. (2013) Advance care planning in care homes: The experience of staff, residents, and family members. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 19(11): 550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan AM, Lakoma MD, Block SD. (2003) The status of medical education in end-of-life care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 18(9): 685–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utley-Smith Q, Colón-Emeric C, Lekan-Rutledge D, et al. (2009) The nature of staff–family interactions in nursing homes: Staff perceptions. Journal of Aging Studies 23(3): 168–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace M, Grossman S, Campbell S, et al. (2009) Integration of end-of-life care content in undergraduate nursing curricula: Student knowledge and perceptions. Journal of Professional Nursing 25(1): 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh Government (2017) Palliative and End of Life Care Delivery Plan. Available at: http://gov.wales/docs/dhss/publications/170327end-of-lifeen.pdf (accessed 21 November 2017).

- World Health Organization (2011) WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available at: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed 22 July 2017).

- Wye L, Lasseter G, Percival J, et al. (2014) What works in ‘real life’ to facilitate home deaths and fewer hospital admissions for those at end of life? Results from a realist evaluation of new palliative care services in two English counties. BMC Palliative Care 13(1): 37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]