Abstract

Aim and Methods

The aim was to evaluate the implementation of a structured physical activity (PA) programme for individuals living with a dementia in care homes. More specifically, the study aimed to test the effects on the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory and Algase Wandering Scale. The study was undertaken over 16 weeks using a quasi-experimental design. Registered nurses, physiotherapists, assistants in nursing and physiotherapy aids from one aged care organisation in NSW, Australia, undertook the study with academics.

Results

A total of 72 individuals living with a dementia from four care homes participated. Implementation of the structured PA programme generated statistically significant findings with reductions in agitation (p < 0.001) and eloping (p = 0.001) achieved for individuals living with a dementia in care homes.

Conclusions

Physiotherapists and exercise physiologists can complement nursing-focused care teams and contribute to a holistic model of care for individuals living with dementia in care homes. The study demonstrated how a structured PA programme positively affected the levels of agitation and wandering experienced by individuals living with a dementia. Individuals living with a dementia in care homes who participated in a structured PA experienced positive outcomes from the programme. The findings demonstrated that they benefited from the programme and PA should be promoted for this group just as it is for other population groups, including general populations of older people.

Keywords: dementia, exercise, interdisciplinary health team, nursing homes, psychosocial factors

Introduction

Dementia poses a serious global public health challenge, with an estimated 35.6 million individuals estimated to be living with a dementia in 2010, and numbers expected to double every 20 years (Prince et al., 2013). The incidence and prevalence of dementia in Australia is similar to that experienced in other Western countries. In 2011, 9% of Australians over 65 (one in every 11) were estimated to be living with a form of dementia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2012; Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre, 2016). Approximately 63% of individuals living with a dementia in Australia are living in care homes, with this trend expected to increase (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2012).

Aims

The aims of the study were to: (1) pilot a structured physical activity (PA) programme using ‘in house’ resources, consisting of the physiotherapists, physiotherapy aides and diversional therapists already employed by the host care home, to deliver the structured PA programme to individuals living with a dementia; and (2) evaluate the effects of the structured PA programme on agitation, wandering, quality of life and mobility of individuals living with a dementia in the care homes. In this paper, the outcomes on agitation and wandering are reported.

Literature review

Regular PA is increasingly recognised as beneficial for managing and preventing, or slowing the progression of symptoms and complications of chronic health conditions, including dementia. Systematic reviews investigating the use of structured PA programmes for individuals living with dementia showed positive associations with improvements in cognition (Brett et al., 2015) and performance of activities of daily living (Forbes et al., 2015). However, there is little evidence specifically about how exercise reduces the expression of unmet needs, such as agitation, anxiety, depression, and wandering by individuals living with dementia (Brett et al., 2015; Forbes et al., 2015).

The expression of unmet needs in dementia care, sometimes referred to as behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), are common among individuals living with a dementia in care homes (Brodaty et al., 2001). Expressions of unmet needs are also associated with poor quality of life in the individuals living with a dementia (Beerens et al., 2013), family carer burden (Pinquart and Sorenson, 2003) and staff stress (Brodaty et al., 2003). Interventions aimed at reducing these distressing experiences in care homes can contribute towards improving the health and well-being of individuals living with a dementia, family carers and staff. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the implementation of a structured PA programme could reduce expressions of unmet need among individuals living with dementia in care homes.

This study built on audits of PA levels in which it was demonstrated that wholly unsatisfactory levels of PA are experienced by older people in care homes, with 79% of their time spent sedentary (Barber et al., 2015). For individuals living with a dementia it is worse, they experience an average of only 1–2 PA events per day, for example, walking to the dining room or to an outside area of the care home where they live (DeVries and Traynor, 2012). When the evidence is indubitable about the benefits of PA for all population groups, this lack of PA for individuals living with dementia in care homes is unacceptable. Also, we can assume from these findings that individuals living with a dementia in care homes never or rarely participate in a structured PA programme. For these interventions to be sustainable, it is important that they are practical and can be delivered within current constraints and resources of care home systems. Successful interventions become sustainable if they are feasible without additional staff or resources (Yost et al., 2015). This study contributed to these goals by implementing and evaluating an intervention using the usual staff and outcome measures already accepted as clinical assessment tools in the participating care homes. An intervention study was designed to address this issue and evaluate the effects of providing individuals living with a dementia in care homes participating in a structured PA programme.

Research design

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of implementing a structured PA programme on agitation, wandering, quality of life and physical outcomes for individuals living with a dementia. A quasi-experimental pre-test and post-test design was used to objectively measure quantifiable changes. In this paper, the focus is on evaluating the effects of the structured PA programme on the expression of unmet needs, specifically whether agitation and wandering changes after participating in a structured PA programme for individuals living with a dementia living in care homes. No control group was allocated because the potential sample size was too small and the study had limited resources to expand the research sites. Ethical approval to undertake this study was provided by University of Wollongong and Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District Ethics Committee: 2012/456.

Setting and sample

The study was undertaken in four care homes run by one not-for-profit aged care organisation in four suburbs in regional NSW, Australia. All individuals living with a dementia able to participate in a standing or seated structured PA programme were invited to participate in this study. All potential participants were identified by staff working at the care homes. These individuals, along with their family carers, were invited by staff to attend open information sessions about the study. Specifically, explanation of the proposed structured PA programme and the proposed outcomes measures used to evaluate the effects of the structured PA programme on individuals living with a dementia in a care home was provided.

Written consent was sought from individuals able to read the participant information sheet and provide written consent. Verbal consent was recorded using the process consent method when an individual was unable to read the participant information sheet and provide written consent (Dewing, 2007). This process assesses the willingness of individuals to participate in research by monitoring assent through ongoing observation of verbal and non-verbal cues. In addition, a courtesy letter and information sheet was posted to all family carers of those individuals who provided written consent, verbal and non-verbal consent to participate in the study. During implementation of the PA programme by the physiotherapists, physiotherapy aides and diversional therapists, they continually used process consent to monitor verbal and non-verbal cues about the willingness of individuals to participate. Individuals who demonstrated they had withdrawn their consent to participate, by appearing agitated or distressed, during the PA session were sensitively assisted to leave the PA session.

Intervention

Development of the intervention started with a literature review of effective PA programmes for individuals living with a dementia in care homes to ensure it reflected evidence based practice (Blankevoort et al., 2010; Brett et al., 2015). Importantly, an investigator in this study (SG) was a physiotherapist and the manager of the physiotherapist services within the organisation where the study was undertaken. Input from SG ensured the intervention implemented could be sustained in the future within existing staffing profiles and resources. It was crucial to the success of this study that staff were involved in developing the PA programme. The physiotherapist manager and the host university investigators undertook an extensive consultation activity with registered nurses, assistants in nursing, physiotherapists, physiotherapy aids and diversional therapy staff across the participating care homes. Workshops were held to generate suggestions about which activities to include within the structured PA programme and also ways to create opportunities for increasing incidental PA for individuals living with a dementia living in the care homes where they worked. During the consultation activity, the physiotherapist manager sensitively managed discussions to ensure only suggestions which could be implemented within existing staffing profiles and resources were included in the design of the intervention.

The structured PA programme was implemented by physiotherapists, physiotherapy aides and diversional therapy staff. The structured PA programme was tailored for each care home and the physiotherapist manager integrated training of staff to deliver the PA programme into their usual work activities. The physiotherapist manager introduced the intervention in the same way that other new initiatives were introduced within the host organisation. The physiotherapist manager also monitored the implementation of the intervention in the same way as new initiatives were usually monitored, namely regular phone calls and face-to-face visits to the care homes where the physiotherapists, physio aids and diversional therapy staff worked and reviewing the electronic records used by the staff to record the progress of individuals living with a dementia participating in PA programme.

The structured PA programme was offered to participants three times per week for a combined time of 30 minutes (in one or more sessions per week) over 16 weeks. The structured PA programme delivered was determined during each session by the physical and cognitive abilities of the participants. The type and amount of PA undertaken by the participants was recorded over 16 weeks during the delivery of the intervention. The structured PA programme included walking, range of movement exercises, weights/strength exercises, and balloons/ ball games. Data were recorded at baseline immediately prior to commencement of the intervention at pre-intervention (T0) and 16 weeks after commencement of the intervention at post-intervention (T1).

Measures

Agitation is one of the hallmark symptoms of dementia and is characterised by inappropriate verbal, vocal, or motor activity not judged by an outside observer to result directly from perceptible needs or confusion of an individual experiencing agitation (Cohen-Mansfield and Billig, 1986). Agitation was measured using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) (Cohen-Mansfield, 1991; Werner et al, 1994). Wandering is a syndrome characterised by dementia-related locomotion behaviour of a frequent, repetitive, temporally disordered and/or spatially-disoriented nature. The individual who wanders experiences lapping, random and/ or pacing patterns, some of which are associated with eloping, eloping attempts or getting lost unless accompanied (Algase et al., 2007). Wandering was measured using the Algase Wandering Scale (AWS) (Algase et al., 2004; Supporting Health care workers in understanding New approaches in Evidence based Training (SHINE) in Dementia, 2017).

Statistical analysis

Measurement of agitation and wandering, using the CMAI and AWS respectively, were completed by staff (registered nurses and assistants in nursing) after training from a researcher in the use of the measurement tools to increase the reliability of recording of the data. Intention to treat principle was applied, with pre-intervention outcome measures carried forward for missing data (Polit and Gillespie, 2009). Contingency table and chi-square analyses were conducted for categorical data to establish whether there were significant relationships between gender, care homes, and CMAI and AWS. Non-parametric analyses using Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to analyse pre-intervention and post-intervention scores for CMAI and AWS, as data were not normally distributed.

Results

Participants

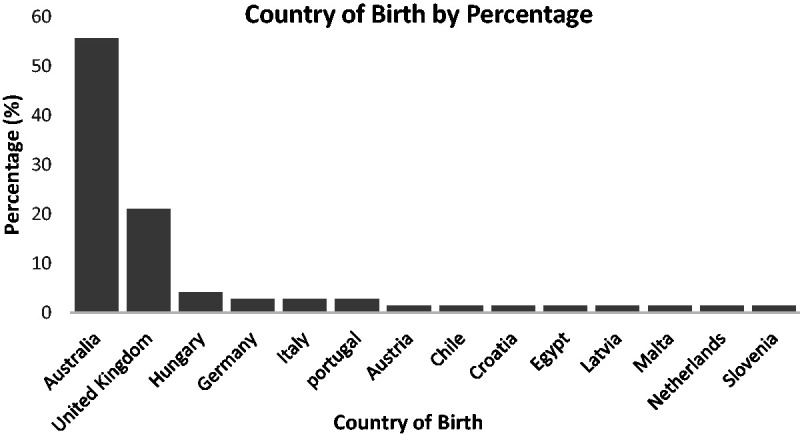

There was a 60% participation rate from individuals living with a dementia across the participating care homes (n = 72). There was a comparable gender distribution among the participants, with only a slightly higher rate of women (51%) than men (49%), an unusual distribution for this population where the overall majority are women. The mean age was 84 ± 18.5, ranging from 66 to 103 years. Just over half of the participants were born in Australia and just under one quarter spoke a language other than English as their first language (Figure 1). As is common in care homes across the globe, all participants were receiving what is classified in Australia as ‘high care’ care home services. All participants were able to undertake some form of PA but all would be described as frail older persons receiving high levels of care to maintain their independence in their living environment. Just under 10% of participants used a wheelchair to mobilise around the care home with just over 90% were independently mobile with or without a walking aid sometimes or most of the time.

Figure 1.

Country of birth for participants.

Participation in the structured PA programme

Twenty-eight participants (39%) completed the structured PA programme three times a week for at least one continuous 6-week period and 47 (65%) completed the structured PA programme at least once per week for a continuous 6-week period. Inadequate documentation for attendance at the structured PA programme resulted in missing data about the level of involvement for participants in the structured PA programme. One care home provided meticulous data on participation in the structured PA programme and thus full participation over a 6-week period (×3 weekly) was related to the care home where the participant lived (χ2 = 25.32, p < 0.001).

Agitation

Agitation was measured by the CMAI (Tables 1 and 2). Overall, there was a statistically significant decrease in agitated behaviours following the structured PA programme, z = −3.88 (corrected for ties), p < 0.001. In particular, there were statistically significant decreases in the aggressive behaviours, z = −2.52 (corrected for ties), p = 0.012 and physically non-aggressive behaviours, z = −2.68 (corrected for ties), p = 0.007. A trend for decreased verbal agitation following the structured PA programme was also observed, z = −1.89(corrected for ties), p = 0.059.

Table 1.

Frequencies of CMAI scores pre- and post-intervention.

| Pre-intervention (n = 71) |

Post-intervention (n = 71) |

|

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Aggressive behaviour | 23 (32.4) | 12 (16.9) |

| Not aggressive behaviour | 48 (67.6) | 59 (83.1) |

| Physically aggressive | 27 (38.0) | 15 (21.1) |

| Not physically aggressive | 44 (62.0) | 56 (78.9) |

| Verbally agitated | 31 (43.7) | 21 (29.6) |

| Not verbally agitated | 40 (56.3) | 50 (70.4) |

Note. Data was missing for one participant on all measures of the CMAI.

Table 2.

Comparison of pre- and post-intervention CMAI scores.

| Pre-intervention (n = 71) |

Post-intervention |

Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) | M(SD) | |||

| Physically aggressive behaviours (15) | 5.3(2.4) | 4.8(2.0) | −2.52 | 0.01 |

| Physically non-aggressive behaviours (20) | 8.3(3.5) | 6.6(3.1) | −2.68 | 0.01 |

| Verbal agitation (20) | 9.1(3.0) | 7.8(3.1) | −1.89 | 0.059 |

| Overall (55) | 22.7(7.1) | 19.2(6.5) | −3.88 | <0.001 |

Note: Total scores are listed in parentheses. Higher scores represent higher frequency of behaviours. Data was missing for one participant on all measures of the CMAI.

Wandering

Wandering was measured by the AWS (Table 3). Following the intervention, a statistically significant reduction in eloping behaviours was found, z = −3.261 (corrected for ties), p = 0.001, as well as a trend for reduced persistent walking, z = −1.83, (corrected for ties), p = 0.067. Regarding spatial disorientation, no statistically significant changes were found following the intervention.

Table 3.

Comparison of pre- and post-intervention AWS scores.

| Pre-intervention | Post- intervention | Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent walking (36) | 19.8(7.4) | 18.7(7.6) | −1.83 | 0.067 |

| Eloping (16) | 6.8(3.4) | 5.6(2.4) | −3.16 | 0.002 |

| Spatial disorientation (24) | 12.9(4.6) | 13.1(4.9) | −0.17 | 0.86 |

Note: Total scores are listed in parentheses. Higher scores represent higher frequency of behaviours.

Relationship between behavioural changes and number of PA sessions completed

The changes in agitation and eloping behaviour scores (CMAI and AWS, respectively) were analysed against the amount of PA sessions recorded using a scatter plots and non-parametric testing (Mann–Whitney U-tests, Kruskal–Wallis tests). No association was found between the number of PA sessions completed and changes in agitation or eloping behaviours.

Discussion

The expression of unmet needs by individuals living with a dementia in care homes, including agitation and wandering, are distressing for the individual experiencing them as well as their co-residents, family carers and staff (Brodaty et al., 2003). The consequences for individuals living with a dementia are that staff manage expressions of unmet needs using pharmacological treatments. This approach continues despite health care guidelines clearly presenting evidence that non-pharmacologic avenues be the first line treatment for those expressing unmet needs. Evidence based non-pharmacological alternatives include behavioural management plans, aromatherapy, multisensory stimulation, music or dance therapy, animal therapy and massage (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2007). This study demonstrated that implementing a structured PA programme is another effective strategy to reduce the expression of unmet needs, specifically agitation and wandering for individuals living with a dementia in care homes. If structured PA programmes were incorporated consistently in care home services, another non-pharmacological treatment could be used to reduce the expression of unmet needs, specifically agitation and wandering, experienced by individuals living with a dementia. The distress experienced by their co-residents, family carers and staff who witness the effects of them expressing their unmet needs could also be reduced.

It is important to note that, in this study, no relationship was found between the amount of documented PA completed and the changes in levels of agitation or eloping behaviours recorded for individuals living with a dementia who participated in this study. This finding might be due to the large variance in recording of PA completed by individuals. In one care home the physiotherapist aid who implemented the intervention was very motivated and had a nearly 100% completion record for all individuals living with a dementia who participated in the intervention at the care home where she worked. At another care home, the research team had to review the electronic care records of individuals and retrospectively record the PA completion rates because the physiotherapist aid had not consistently used the data recording sheets provided by the research team. It is not possible to know how much influence this inconsistency in data recording had on the findings of the study. Suffice it to say, the strength of the effect of completion rates of the structured PA programme on agitation experienced by individuals living with a dementia in care homes was diluted by a lack of data.

Another reason why completion rates were not significant could be because by the end of the study there was an overall change in care home environment regarding PA levels and it could have been this overall change which reduced agitation among individuals. The study began with an extensive consultation activity in which workshops were held in each of the four participating care homes. The workshops were used by the researchers to consult with the care home staff to develop the content for structured PA programme. An unplanned outcome during these workshops was the spontaneous development by staff of action plans for ways to increase incidental PA. The action plans developed during the workshops were recorded by the research team and presented to the care home staff who implemented their action plan during the 16-week delivery of the intervention. The university research team members worked with the Directors of Nursing (DoNs) to provide support and guidance on implementation of PA action plans and the DoNs worked with their staff to implement the goals recorded in their action plans.

The university research team members met with the DoNs at each of the participating care homes at least twice to provide further support and guidance to increase the likelihood that the action plans were being implemented by staff during the intervention. The development and implementation of these PA action plans was not an original objective of this study. This outcome was generated from the motivation among the staff who participated in the consultation workshops. It was clear during the workshops that staff were motivated to identify and implement strategies to improve the levels of PA among individuals living with a dementia who lived in the care home where they worked. The staff spontaneously developed the action plans and demonstrated a commitment to implement their PA action plans during the study. This additional outcome from the study demonstrated the commitment of the staff to improving PA levels among individuals living with a dementia in care homes.

Prior to this intervention study an audit of PA levels across the care homes run by the aged care organisation was undertaken by the university research team (DeVries and Traynor, 2012). The audit found unacceptably low levels of PA among individuals living with a dementia in care homes. The host aged care organisation made a commitment to improve PA levels among individuals living with a dementia and it became one of their strategic goals. This meant that PA levels was a corporate priority and with careful negotiation with the university research team resulted in forward planning to ensure PA was core business for a prolonged period. Employing a team of physiotherapists, including a physiotherapist manager (SG) is an unusual model of care in Australia where it is more common for aged care organisations to ‘out-source’ physiotherapy services and pay private companies to deliver physiotherapy services to individuals living in care homes. Workload was allocated by the DoNs and the physiotherapist manager to nursing, physiotherapy and diversional therapy staff to focus on implementing the structured PA programmes across all participating care homes in the organisation. This was crucial in making the study a success for the individuals living with a dementia who participated. It was the organisational support for this study, at the highest levels, which ensured the intervention was consistently implemented during the study and staff worked to increase incidental PA for individuals living with a dementia in various ways as they implemented their PA action plans in each participating care home.

The findings from this study suggested that even minor increases in PA positively affected expressions of unmet needs for individuals living with a dementia living in care homes, specifically reductions in agitation and wandering. What cannot be ignored was the additional effects on the outcomes of increased awareness among staff about the benefits of increased PA and how to increase incidental PA. This increased awareness was achieved from staff participating in workshops at the commencement of the study and being exposed to a larger number of individuals living with a dementia being ‘treated’ by physiotherapists, physiotherapy aids and diversional therapy staff when they delivered structured PA programmes. Altogether, a more PA friendly active environment was created during the study. This improved awareness about the positive effects of PA is likely to have improved the stimulation for all individuals living with a dementia in the participating care homes. While this study only documented scheduled PA sessions, it is possible that establishing a more PA friendly environment encouraged all staff to promote, and thus increase, PA among individuals, for example, encouraging individuals to mobilise independently and undertake more unprompted incidental PA. To capture these changes, other systems such as accelerometers or systematic environmental scanning of the care home environment is needed to be included in future study designs evaluating PA (Jansen et al., 2015).

Some limitations to the arguments presented in this paper need to be acknowledged. The study did not implement a control group because it was a pilot intervention with limited resources. Cultural influences were not considered as a potential confounder in the study, which may have influenced the results. Specifically, the sample of participants included in the study was multicultural, with just under one quarter of the participants originating from non-English speaking backgrounds and just under one half of the participants were born overseas. The participating aged care provider has a diverse cultural background among the older people receiving their services and among the staff providing care. Language barriers were not raised as a challenge by staff in the participating care homes and the data collection tools relied on observations rather than verbal responses, which mitigated against any potential problems with language. It would be useful to explore this issue further in future studies undertaken in such culturally diverse populations with individuals living with a dementia to expand work undertaken in the UK on this topic (Botsford et al., 2011). Our study would have also benefited from a cost-benefit analysis similar to that undertaken by a dementia care educational intervention (Chenoweth et al., 2009) so the financial benefits of implementing the structured PA programme on agitation and wandering could be measured. In addition, this study did not compare different parameters of exercise however proceeding studies by our research team addressed this gap and measured different exercise regimes (Brett et al., 2017).

The study aimed to examine the efficacy of a programme conducted in the ‘real world’ of busy care homes with limited resources. This study generated positive outcomes without any additional staff or resources to deliver the structured PA programme. In each participating care home there was a nominated physiotherapist, physiotherapy aide and/or diversional therapist to be a study champion for implementing the PA intervention. This role was fulfilled very successfully with enthusiasm by highly motivated staff which ensured a high attendance rate and low attrition rate among participants for the PA intervention. Registered nurses and assistants in nursing collected the CMAI and AWS data and this was completed rigorously and thoroughly. Incorporation of the outcome measures into care home e-documentation systems would reduce the time needed to complete outcome measures for future quality initiatives by care homes and for research studies completed by external collaborators. What was lacking, and resulted in missing data, was the recording of participation in the PA programme in the documentation used to record the progress of individuals living in the care homes. The use of graduated start times of the intervention within each of the care homes would enable pre- and post-test measures to be performed over a longer time period, thereby reducing time pressures on staff to achieve more consistent longitudinal data collection.

Physiotherapists and exercise physiologists working in care homes contribute a crucial role in promoting the health and well-being of individuals living with a dementia. However, currently much of their work is focused on assessment of mobility and falls risk, or specific treatment for pain or acute injury. The profession came from the medical model of care where patients were ‘treated’ for specific conditions, and still within Australia, funding instruments for care homes focus on pain management treatment by physiotherapists rather than a wellness model which aims for optimisation of physical and mental function. Physiotherapists and exercise physiologists are well placed to be the champions of structured PA programmes for individuals living with dementia, as they are able to tailor exercise or functional PA for the needs and capacity of the individual, taking into account co-morbidities, and monitoring the challenges which occur following changing cognitive and physical states. The programmes could be designed by registered regulated practitioners and delivered by physiotherapy aides or diversional therapists similar to the way nursing care is planned and delivered with teams of staff. This model would create a more realistic approach to ensuring PA becomes more commonplace for individuals living with a dementia in care homes. The benefits are clear with reduced agitation and wandering of dementia and it is most likely that these improvements had a positive effect on the overall health and well-being for the individual living with dementia, family carers and staff. It is therefore important for physiotherapists to be part of a holistic care model to try to achieve optimum well-being for individuals living with dementia within care homes. The results from this study will be made available for practitioners and researchers to build on in their practice and research.

Conclusion

This study found that amending existing ad hoc sporadic PA programmes to become structured PA programmes delivered systematically in care homes made a positive contribution to reducing agitation and wandering experienced by individuals living with dementia. Working together registered nurses and physiotherapists can promote an environment which is rich in physical activity. For registered nurses this would involve creating opportunities for more incidental activity, including amending the environment to ensure physical activity is easier to achieve for frail older people and adopting a rehabilitative model of care in all aspects of nursing care. For physiotherapists, funding models in nursing homes need to change to allow reimbursements beyond treating pain, which is their current limit, and also include programmes to promote well-being of frail older people. Our next study will be a cost-benefit analysis of a structured PA programme for individuals living with dementia in care homes.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

This study contributed to addressing a neglected area of evidence about the value of physical activity (PA) programmes for individuals living with dementia in care homes.

By working together nurses and allied healthcare practitioners can use structured exercise activities to reduce agitation and wandering experienced by individuals living with dementia in care homes.

Outcomes for PA programmes for individuals living with dementia in care homes can focus on measuring the effects on agitation and wandering rather than physical outcomes which are difficult to prove in this population group who are physically frail and are likely to experience ongoing physical decline over their time in a care home.

Future research needs to focus on developing more sensitive tools to evaluate changes in agitation and wandering to enable practitioners to know what programmes work for individuals living with dementia in care homes.

Funding models for care home care across the world need to more effectively include ways in which physiotherapists and exercise physiologists can complement nursing focused care teams.

Acknowledgements

The clients and staff who participated in this study were crucial to its success. The clients were willing to ‘have a go’ at a new exercise intervention in their care home and the commitment of staff to the project on top of their usual duties ensured the researchers were able to deliver the intervention in the timeframe required and within the allocated resources.

Biography

Victoria Traynor has 25 years of experience working on aged and dementia care. Victoria is the founding director of the Aged and Dementia Health Education and Research (ADHERe) (www.adhere.org.au) centre which leads inter-disciplinary research generating evidence in gerontological studies with a focus on transforming the lives of older people and family carers through the implementation of evidence based care. Highlights from the outputs of ADHERe are developing a Dementia and Driving Decision Aid (DDDA) for consumers and family carers and developing interactive online and face-to-face workshops on a range of person centred care topics for aged care nursing. Victoria also developed the first national Delirium Care Pathways in Australia.

Nadine Veerhuis has a public health background and brings a crucial and complementary perspective to the ADHERe team at the University of Wollongong. Nadine continually challenges stereotyping about ageing and the stigma associated with living with a dementia for consumers and family carers. Most recently, Nadine was the project manager for developing the Dementia and Driving Decision Aid (DDDA) for consumers and family carers. Nadine’s passion is for developing health education and promotion resources for older people, in particular and individuals living with a dementia which are relevant, accessible and usable. Nadine also develops health education and health promotion plans which can be implemented across services acknowledging the interconnectedness of healthcare disciplines and services.

Keryn Johnson is lecturer and a physiotherapist with over 35 years of experience. Keryn works in aged care and her focus is on enabling older people living in retirement villages and care homes to adopt healthy lifestyles. Keryn adopts health behaviour change theory to develop effective strategies to improve the lives of older people. Keryn’s passion is translating evidence-based practice in policy and practice.

Jessica Hazelton has a background in psychology, with a keen interest in neuropsychology. In particular, Jessica’s passion is in investigating the impact of frontotemporal dementia on social cognition, and the effect these changes have on those affected and their families. Jessica is a regular Blog contributor to raise awareness about new ways of thinking about the impact of dementia on individuals.

Shiva Gopalan is a physiotherapist with 10 years of experience specialising in aged care. Shiva is the manager of the wellness and lifestyle services for a regional aged care provider. Shiva’s focus is on developing services which promote healthy lifestyles for the clients who live in the retirement villages and care homes. What drives Shiva is designing innovative ways to deliver age care services. He especially emphases how to enable individuals living with a dementia from culturally and linguistically diverse communities to fully participate in the communities within which they live.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the University of Wollongong and Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District Health and Medical Ethics Committee.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the University of Wollongong and Warrigal.

References

- Algase DL, Beattie ER, Song JA, et al. (2004) Validation of the Algase Wandering Scale (Version 2) in a cross-cultural sample. Aging and Mental Health 8: 133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algase D, Moore H, Vandeweerd C, et al. (2007) Mapping the maze of terms and definitions in dementia-related wandering. Aging & Mental Health 11: 686–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2012) Dementia in Australia, Canberra: AIHW. [Google Scholar]

- Barber SE, Forster A, Birch KM. (2015) Levels and patterns of daily physical activity and sedentary behavior measured objectively in older care home residents in the United Kingdom. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity 23: 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerens HC, Zwakhalen SMG, Verbeek H, et al. (2013) Factors associated with quality of life of people with dementia in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 50: 1259–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankevoort CG, Van Heuvelen MJ, Boersma F, et al. (2010) Review of effects of physical activity on strength, balance, mobility and ADL performance in elderly subjects with dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 30(5): 392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botsford J, Clarke CL, Gibb CE. (2011) Research and dementia, caring and ethnicity: a review of the literature. Journal of Research in Nursing 16(5): 437–449. [Google Scholar]

- Brett L, Traynor V, Stapley P. (2015) Effects of physical exercise on health and well-being of individuals living with a dementia in nursing homes: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 17(2): 104–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett L, Traynor V, Stapley P, et al. (2017) Effects and feasibility of an exercise intervention for individuals living with dementia in nursing homes: study protocol. International Psychogeriatrics. 29(9): 1565–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Draper B, Low F-L. (2003) Nursing home staff attitudes towards residents with dementia: strain and satisfaction with work. Journal of Advanced Nursing 44: 583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Draper B, Saab D, et al. (2001) Psychosis, depression and behavioural disturbances in Sydney nursing home residents: prevalence and predictors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 16: 504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth L, King MT, Jeon YH, et al. (2009) Caring for Aged Dementia Care Resident Study (CADRES) of person-centred care, dementia-care mapping, and usual care in dementia: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Neurology 8(4): 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre (2016) Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia. Available at: http://sydney.edu.au/medicine/cdpc/documents/resources/CDPC-Dementia-Guidelines_WEB.pdf (accessed 10 June 2017).

- Cohen-Mansfield J (1991) Instruction manual for the Cohen-Mansfield agitation inventory (CMAI). Rockville: The Research Institute of the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington. Available at: https://www.pdx.edu/ioa/sites/www.pdx.edu.ioa/files/CMAI_Manual%20%281%29.pdf (accessed 10 June 2017).

- Cohen‐Mansfield J, Billig N. (1986) Agitated behaviors in the elderly. I. A conceptual review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 34(10): 711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Collaborative Research Centres (2016) Dementia Outcomes Suite. Available at: http://dementiakt.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CMAI_Scale.pdf (accessed 10 June 2017).

- DeVries L, Traynor V. (2012) Evaluating the impact of environmental design features on physical activity levels of individuals with dementia living in residential accommodation. In: Innes A, Kelly F, McCabe L. (eds) Key Issues in Evolving Dementia Care: International Theory-based Policy and Practice, London: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Dewing J. (2007) Participatory research: a method for process consent with persons who have dementia. Dementia 6: 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Forbes SC, Blake CM, et al. (2015) Exercise programs for people with dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD006489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen C-P, Claben K, Wahl H-W, et al. (2015) Effects of interventions on physical activity in nurse home residents. European Journal of Ageing 12: 261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2007) Dementia: The NICE-SCIE Guideline on Supporting People with Dementia and their Carers in Health and Social Care. National Clinical Practice Guideline No. 42. London: British Psychological Society. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. (2003) Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: a meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontology 58B: 112–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, Gillespie BM. (2009) The use of intention-to-treat principle in nursing clinical trials. Nursing Research 58: 391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, et al. (2013) The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Dementia 9: 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supporting Health care workers in understanding New approaches in Evidence based Training (SHINE) in Dementia (2017) Revised Algase Wandering Scale: Long-term Care Version. Available at: https://shine-dementia.wikispaces.com/file/view/Revised+Algase+Wandering+Scale+(RAWS).pdf (accessed 10 June 2017).

- Yost J, Ganann R, Thompson D, et al. (2015) The effectiveness of knowledge translation interventions for promoting evidence-informed decision-making among nurses in tertiary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implementation Science 10(1): 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner P, Cohen-Mansfield J, Koroknay V, et al. (1994) The impact of a restraint-reduction program on nursing home residents: physical restraints may be successfully removed with no adverse effects, so long as less restrictive and more dignified care is provided. Geriatric Nursing 15(3): 142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]