Abstract

Background

Therapeutic horticulture is a nature-based method that includes a range of green activities, such as gardening, to promote wellbeing. It is believed that therapeutic horticulture provides a person-centred approach that can reduce social isolation for people with mental health problems.

Aims

The aim of the project was to evaluate the impact of a mental health recovery programme that used therapeutic horticulture as an intervention to reduce social inclusion and improve engagement for people with mental health problems.

Methods

A mixed-methods approach was used and data from four semi-structured focus group interviews, 11 exit interviews and 20 ‘recovery star' datasets were collected from September 2015 to October 2017. Qualitative data from the interviews were thematically analysed, and quantitative data based on a recovery star outcomes tool were analysed using descriptive statistics to demonstrate trends and progression. The findings were then triangulated to provide a rich picture of the impact of the mental health recovery programme.

Results

The recovery star data indicated that participants were working towards self-reliance. Qualitative data from the exit interview and semi-structured focus groups found similar results. The triangulated findings highlight that the mental health recovery programme enabled participant integration into the community through providing a space to grow and build self-confidence while re-engaging with society. The results suggest that using therapeutic horticulture as an intervention within the mental health recovery programme can support people with mental health problems to re-engage socially. Nature-based activities could be used within the ‘social prescribing’ movement to encourage partnership working between the NHS and voluntary sector organisations which can complement existing mental health services.

Conclusion

The use of therapeutic horticulture as an intervention within a mental health recovery programme can support people with mental health problems to re-engage with the community and is integral to the rehabilitation process. The mental health recovery programme should be promoted within the social prescribing movement as an evidence-based opportunity to support people in the community.

Keywords: mental health, nature, therapeutic horticulture

Introduction

It is acknowledged that mental health problems will result in significant challenges to health services by 2020 (World Health Organization, 2001). Moreover, the association between mental illness and social deprivation is recognised as significant, and it is conceded that poverty in particular can negatively influence poor mental health (Murali and Oyebode, 2004). A number of public health strategies have been implemented to help promote health and wellbeing by targeting urbanised communities, particularly in socially deprived areas. Moreover, the use of non-medical interventions within a ‘social prescribing’ movement to promote person-centred approaches for people with social or psychosocial needs is recognised as a method that can actively target individuals and communities within socially deprived areas (University of Westminster, 2017). Social prescribing can include nature-based activities such as ‘ecotherapy’, ‘therapeutic horticulture’ (TH) or ‘green care’ to support an individual’s recovery through community asset-based approaches (Howarth et al., 2016). Social prescribing options are available to healthcare professionals when a person has needs that are related to their psychosocial wellbeing and socioeconomic situation. Social prescribing has been identified within the general practice forward review (NHS England, 2016) as an important ‘high impact action’ (University of Westminster, 2017).

Social prescribing is primarily indicated for people with long-term conditions and is a person-centred, community-based approach harnessing assets within the voluntary and community sectors to improve and encourage self-care and facilitate health-creating communities (University of Westminster, 2017). Hence social prescribing is considered to be an alternative approach that promotes partnership and interagency working (South et al., 2008). In 2007, the UK national charity Mind (2013) set out a ‘green agenda’ for mental health using ‘ecotherapy’ as a framework, and asserted that nature-based services should be a clinically valid treatment for mental health distress. The use of nature-based interventions within a social prescribing movement has gained in popularity, and there has been an increase in the number of funders willing to support the development of nature-based programmes that support people with mental health problems.

Using evidence from an evaluation of the use of TH within a mental health recovery programme (MHRP), this paper discusses the impact of TH on social inclusion and engagement for people with mental health problems within a social prescribing framework.

Literature review

It is understood that social isolation can be a common challenge for people with mental health problems (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). The stigma associated with mental health, coupled with the individual’s fear of socialising, can result in isolation and loneliness. Steptoe et al. (2012: 5797) defined social isolation as ‘an objective and quantifiable reflection of reduced social network size and paucity of social contact …’. Significantly, it is acknowledged that social networks and relationships are integral to an individual’s wellbeing, and that isolation can cause depression and increase biophysical ailments and mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). Hence, policy makers and commissioners recognise the impact that poor social relations, exclusion and loneliness have on mental and physical wellbeing. Significantly, there is an increased recognition of the utility of green therapies and ‘ecotherapy’ for people with mental health problems in the community setting. In addition, there is an emerging body of evidence detailing the effectiveness of TH. For example, it is reported by Van den Berg et al. (2010) and Mayer et al. (2009) that exposure to nature has a positive effect on a person’s mental wellbeing. Moreover, Gonzalez et al.'s (2010) study of people attending a TH programme found that it can be a beneficial supplementary intervention in clinical depression.

The relationship between nature and positive benefits for humans has grown over the past 20 years and it is reported that there is a range of activities that constitute ‘green therapy’; the most common understanding is that it can be used to promote health and wellbeing for people who may be vulnerable or who are socially excluded (Berget et al., 2012; Gullone, 2000). Subsequently, there has been a steady growth in research that has measured the benefits of nature on health while, in addition, TH is acknowledged to have a social benefit as, for example, it has a positive influence on an individual’s social engagement (Gonzalez et al., 2010; Grinde and Patil, 2009). This is notable, particularly as it is now recognised that green spaces and access to vegetation have made major contributions to the quality of health and wellbeing in inner city and suburban areas (Morris, 2003). However, there have been few longitudinal studies to demonstrate impact and it has been recommended by Public Health England (2014) that further experimental research is required to measure key clinical health outcomes.

Open-air recreation has demonstrated positive wellbeing effects because it provides scope for activity, relaxation and the formation of social relationships, and as such is thought to play a significant role in recovery (Mayer et al., 2009; Van den Berg et al., 2010). Recovery benefits from the individual being in control of their life, and an asset-based approach dovetailed within a recovery framework enables a sense of control as professionals are ‘on tap, not on top’ (Shepherd et al., 2008). Specifically, contact with nature is understood to impact not only on mental health, wellbeing and social connectedness, but also in terms of volunteering, physical activity and changing people’s relationship with nature and food growing, achieving many public health objectives within one space. Moreover, the way in which people have contact with nature through therapeutic horticulture can instil confidence to work with others and reconnect with society. A number of studies have suggested that contact with nature is essential in helping people re-establish a sense of overall wellbeing (Fieldhouse, 2003).

Against this backdrop, a social enterprise based in the north of England developed an MHRP using TH to support people with mental health problems in the recovery process. The MHRP provides a simple guide to growing and enables volunteers to participate in sowing, growing and harvesting of products, and the project builds on the existing work undertaken by the social enterprise. The MHRP utilises the ‘recovery star’ (MacKeith and Burns, 2010), a validated data collection tool that captures the recovery progression of individuals numerically to monitor each volunteer’s mental health and the social and health impact of their participation in the MHRP. However, as Hunt et al. (2000) suggest, measuring the impact of the environment and green spaces on health is challenging because of the complexities associated with the holistic nature of wellbeing. Hence, the research reported used a mixed-methods approach to capture the complexities involved, while evaluating the impact and use of TH within the MHRP.

Project aim and objectives

The aim of the project was to evaluate the impact and use of TH within the MHRP on social inclusion and engagement for people with mental health problems (the ‘volunteers’).

There were three key objectives:

to quantitatively measure the impact of TH as an intervention within an MHRP on individuals using retrospective and prospective data from the validated recovery star data collection tool;

to qualitatively explore participant perceptions and experiences of TH as part of the MHRP using data from exit interviews and semi-structured focus groups;

to triangulate qualitative and quantitative data to provide a holistic perspective of using TH within the MHRP.

Methodology

Mental Health and the influences on health are complex in nature, and an insider or ‘emic’ perspective is often used to construct meaning (Howarth, 2012). Hence, a grounded theory approach based on the framework of Corbin and Strauss (2008) was used to understand the participants’ experiences of using TH within the MHRP. Grounded theory enables researchers to work with participants using a range of data collection tools to understand experience and capture meaning. To enhance depth, a mixed-methods design using action research was used to ensure that the organisation and participants influenced the research process (Huxam and Vangen, 2003).

Data collection

A total of three separate data collection methods were used and the findings were triangulated to generate meaning about the impact of the MHRP. It is acknowledged that methodological triangulation uses two or more methods to study the same context (Mitchell, 1986) and can provide a rich perspective of the study data (Parahoo, 2006). Triangulation can enhance the robustness of analysis by countering the variance in the times, the people, and the settings in which the data were collected (Begley, 1996). Quantitative data were collected from participants' ‘mental health recovery stars’ and semi-structured focus groups were undertaken with participants currently on the MHRP. Finally, semi-structured exit interviews were used to capture the perspectives from those participants who had completed the MHRP.

Quantitative data collection

The recovery star tool is recommended by the Department of Health (2009) for use in a range of services, including mental health. It uses interval data to help staff and individuals plot their progress. One of the key features of the recovery star is that all versions are based on an explicit model of the steps that service users take on their journey towards independence.

Qualitative data collection

Semi-structured focus groups and exit interviews were used to capture qualitative data about volunteers’ experiences of the MHRP. The focus groups and exit interviews were digitally recorded and were transcribed and analysed. The exit interview questions were structured to develop an awareness of the MHRP key outcomes, whereas the focus group questions were semi-structured and designed to allow the research team to probe participants in order to gain a more in-depth understanding of their experience (see Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Focus group questions.

| 1. How did you find out about the MHRP? |

| 2. Why did you join the MHRP? |

| 3. What do you feel are the benefits of the MHRP? |

| a. Managing mental health |

| b. Physical health and self-care |

| c. Living skills |

| d. Social networks |

| e. Work |

| f. Relationships |

| g. Additive behaviour |

| h. Responsibilities |

| i. Identity and self-esteem |

| j. Trust and hope |

| 4. How important is the horticulture as part of the programme? |

| 5. What advice would you give to others who are considering joining the MHRP? |

| 6. Employability? |

MHRP: mental health recovery programme.

Table 2.

Exit interview questions.

| 1. How likely are you to recommend [the MRHP] to others? |

| 2. What worked best for you in [the MHRP]? |

| 3. What did not work as well? |

| 4. What additional services did you access through [the MRHP]? |

| 5. Have you made friends while at [the MHRP]? |

| 6. Have you learned new skills while at [the MRHP]? |

| 7. Would you be willing to share your experiences with others? |

| 8. What makes this service different from others? |

| 9. If you were to change anything about [the MRHP], what would it be? |

| 10. What is it about gardening that you like? |

| 11. To what extent has being a volunteer at [the MHRP] prepared you for employment/re-entry into employment? |

MHRP: mental health recovery programme.

Sample

A purposive sampling approach was used and a total of 20 datasets were collected from the recovery star. The focus groups included 16 people in 4 separate sessions, and 11 people participated in the exit interviews. This provided a total study population of 47 with an age range from 35 to 68 years, with an average age of 53.2 years.

Data analysis

The recovery star typically collected interval data to illustrate progression; hence, descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data. A total of three datasets for each participant were collected over a 2-year period. Data from the focus groups and exit interviews were thematically analysed using grounded theory approaches. The results from all three data sources were later triangulated to demonstrate a complete picture of the phenomena.

Results

The combined data demonstrated that the MHRP, and the use of TH more specifically, helped to reduce social isolation by improving confidence, skill-building and providing the space and opportunity to establish relationships with others through a common purpose.

Recovery star results

Three themes are presented here as each is important in terms of an analysis of the reduction in social isolation. These are: managing mental health, social networks and relationships.

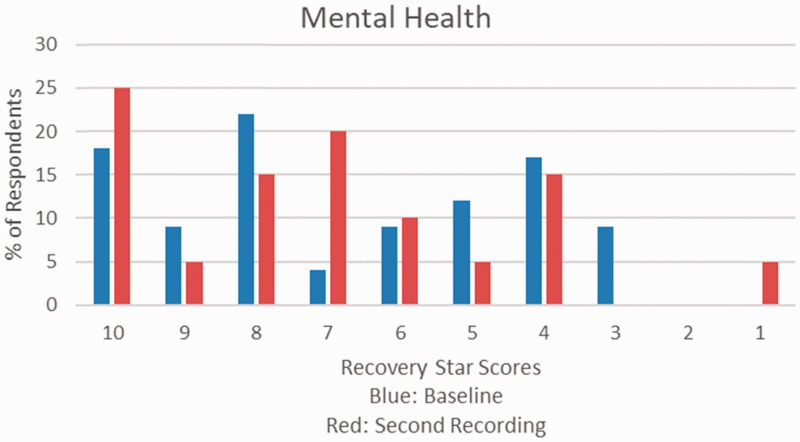

Managing mental health

The recovery star data indicated whether the participants were able to manage their mental health. The baseline score revealed that 27% of participants had recorded that they were managing their mental health, and 26% reported that they were learning how to manage their mental health. However, just under half (47%) indicated that they were actively seeking help to manage their mental health. The data suggest that the MHRP attracted people with a range of mental health problems who were at different stages of managing their mental health (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Managing mental health.

The second recovery star score highlighted that there was some improvement in the mental health scores for 35% of the participants and 45% recorded similar scores to the baseline. Overall, the recovery star data suggest that the MHRP had enabled participants to move from seeking help to learning to manage their mental health.

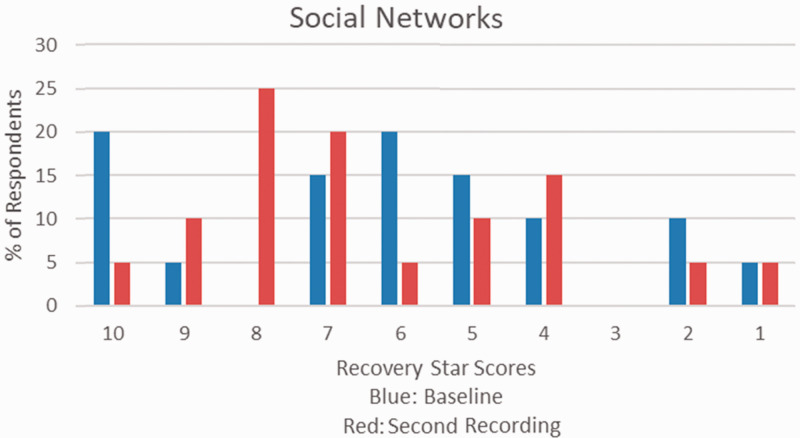

Social networks

The recovery star baseline scores highlighted that 31% of participants identified as accepting that they needed help. The baseline data also suggested that 43% of the participants were ‘stuck’ and had accepted that they needed help (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Social networks.

The qualitative data support these findings, and being connected and integrating with others was viewed as a positive outcome for participants who were interviewed. The repeated recovery star scores indicated a positive trend in the social networks, and an overall improvement of 45% was recorded.

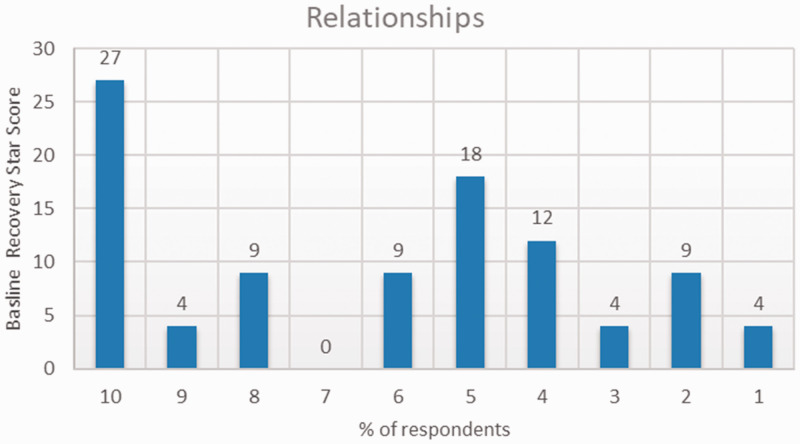

Relationships

The recovery star baseline scores indicated that about a third of participants (31%) felt that they were self-reliant and were able to manage relationships without support. A smaller number reported that they were struggling with relationships; however, some expressed difficulties engaging with others – which was reflected in the qualitative data. The second recovery star dataset indicated that participants recorded an improved score with their relationships. This is a significant indicator for social network development as reducing social isolation will positively influence relationships, and vice versa (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Relationships.

Collectively, the recovery star data indicated an improvement in mental health social networks and relationships. Arguably, these three indicators provide an insight into the participants’ ability to re-connect with others and highlight the potential impact that the MHRP had on social inclusion. However, qualitative data can often provide depth and meaning to a phenomenon; hence, the recovery star data were further explicated within the focus groups and exit interviews.

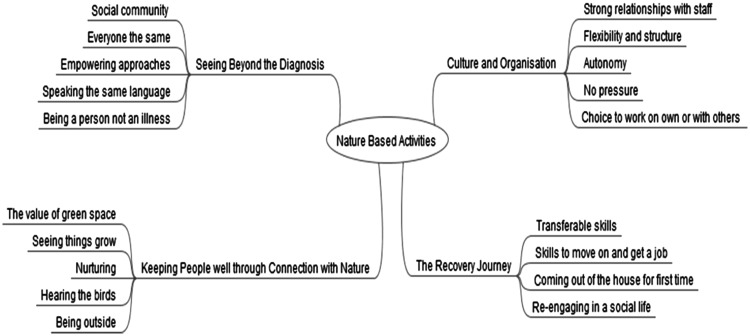

Qualitative data

A total of 11 exit interviews and 4 focus groups were conducted with participants who had completed the MHRP. The focus groups and exit interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and analysed thematically based on the principles of the grounded theory approach of Corbin and Strauss (2008). Four key themes emerged: ‘the recovery journey’, ‘seeing beyond the diagnosis’, ‘keeping people well through connection with nature’ and ‘culture and organisation’. Figure 4 illustrates the triangulated themes.

Figure 4.

Mind map of the key concepts.

The recovery journey

The recovery journey was influenced by the volunteers’ ability to re-engage in social activity, which is often difficult for people with mental health difficulties. Attending the MHRP and using TH approaches that involved shared activities helped individuals to reconnect:

What worked for me? Getting involved really. Helping others out. I seem to know a bit myself, like what I could show other people how they run it. (Exit interviewee 6)

Participation in TH also enhanced the development of new skills as a result of engaging with nature-based activities such as building raised beds, sowing seeds and creating planters for sale. These activities enabled participants to re-engage in a social life, in its broadest sense, and the qualitative data highlighted that participants felt they were developing skills that would assist them in gaining employability. There was also a sense of gaining confidence, which is summed up by one of the participants:

My confidence is ecstatic. The more I work, the more my confidence grows. (Exit interviewee 2)

Some of the participants were retired due to medical reasons, yet there were four participants who had gained meaningful employment as a result of attending the MHRP. As such, re-engaging with others indicated a growth in confidence which enabled participants to re-engage outside of the MHRP context.

Seeing beyond the diagnosis

In addition to skill-building and greater employability, participants articulated a social benefit in attending the MHRP. Volunteers felt that the ability to meet people with similar histories and experiences helped them to connect with others more easily as there was a shared understanding, rather than a focus on their mental health diagnosis. Through TH, they were able to work on a common nature-based activity that provided opportunities to communicate:

I think when you share that level of pain with other people, you do have a connection. (Exit interviewee 6)

I think people who come here, it’s confidential why they come here but I think we all, we’re like peas in a pod. We can just be open and frank, can’t we? (Focus group 4, respondent 1)

The use of nature-based activities promoted both an individual and collective improvement to social skills as participants felt comfortable in working with others; the MHRP brought people together.

Keeping people well through connection with nature

The use of TH as a method to support people to re-engage was influenced by being outside and within green space. Significantly, the qualitative data indicated that working outdoors with nature provided a common goal, which helped to forge relationships and facilitate social connection with others:

I think [gardening] just, it puts you in a state where it’s just enough to stop you from having thoughts about this, that and the other, and you’re focused and what you’re focused on isn’t that important, that you’re going to get really nervous about it. So yeah, I really enjoyed it. (Focus group respondent 5)

… but I definitely connected with people … And once you start going out, even though you know it’s not good you keep doing it. And so after so long having that, you could come in and have a chat and a laugh, it was good. It was really good. (Exit interviewee 9)

Dual processes influenced the participants: on one level, they were happy to be outside to reconnect with nature; in addition, the work with nature such as gardening, using hands and getting dirty appeared to influence the participants’ state of wellbeing.

Culture and organisation

There was a real sense that the organisational culture and staff lent themselves towards a feeling of safety and security that reassured people when attending garden needs:

I think this place … well, I know that this … that [the MHRP] saved my life … because anybody that comes through that front door of this place is made welcome, dealt with in a sympathetic manner, made to feel human again. (Focus group respondent 3)

The informality of the service was mentioned on a number of occasions in terms of how this then facilitated an environment that was found to be welcoming and non-judgemental:

it was very easy going … I’ve volunteered at other places for mental health which were more office based … and I think in an office based environment, even for a charity, it can be more formal. (Exit interviewee 7)

Staff and volunteers instinctively allowed people to select their own path in terms of workload and level of involvement. Volunteers encountered a real sense of allowing people to ‘just be’, rather than pushing them into involvement.

Discussion

According to the Social Fund (2015) report, people who are socially isolated are 1.8 times more likely to visit their GP and 1.6 times more likely to visit A&E. Utilising alternative approaches such as nature-based activities could help reduce social isolation and potentially prevent presentations to primary care and hospital. Similarly, it is realistic to assert that using nature-based approaches such as the MHRP could help to reduce social isolation and ultimately influence longer-term effects and impact on services. Hence, social prescribing can help improve support for communities and individuals to improve health and wellbeing (Bickerdike et al., 2017). Moreover, as noted earlier in this paper, the MHRP is located within a social prescribing framework and there is evidence to suggest that social prescribing can influence a reduction in A&E attendances, outpatient appointments and inpatient admission by 20–21%. According to Dayson et al. (2016), this equates to potential cost savings of £1.98 for every £1 invested. The findings from our study indicate that TH for people with mental health problems provided person-centred approaches that build on individual assets, helping support individual resilience and a move towards recovery. As such, using TH within a MHRP is congruent with the philosophy of social prescribing, and could be used as an intervention for health and social care professions to refer people with mental health problems to a range of nature-based and TH opportunities. In addition, the MHRP provided participants with transferable skills, and in some cases empowered participants to seek employment. Again, the impact of this benefit (that is, skill development and greater employability) is recognised as having the potential to enable individuals to re-engage with their community and effectively reduces social isolation.

It is not only the economic and structural benefits that projects such as the MHRP demonstrate. On a more local or individual level, the findings described in this paper suggest that person-centred approaches, such as those adopted by TH within the MHRP, build on and help develop the strengths of individuals. Moreover, the qualitative data demonstrated the psychological and social value gained from volunteering for the MHRP. Specifically, in terms of the TH interventions offered through the MHRP (gardening, construction, team work, cooking), it was evident that these were particularly critical in helping volunteers to develop and increase their social capital, both collectively and individually. Each TH intervention acted as a mechanism to enable people to re-engage with others in the process of sharing skills and knowledge, building confidence, enhancing resilience, and ultimately enabling people to feel empowered. Fundamentally, this reduced social isolation. As such, the way in which the MHRP was structured, using TH, and delivered incorporates many of the tenets of an asset-based approach from which participants reported to benefit in numerous ways (Improvement and Development Agency (IDeA), 2010).

Asset-based approaches involve mobilising the skills, strengths and knowledge of individuals, and also the connections and resources within communities and organisations, rather than focusing on difficulties and shortcomings (NHS Health Scotland, 2011). The design and delivery of the MHRP using TH clearly instilled the principles of an asset-based model, helping volunteers to engage in mutual support, enhancing coping, and resulting in health and wellbeing improvement (IDeA, 2010). The principles of an asset-based model were evident as volunteers had a choice in their activities, either working alone or within a group, but always towards a shared goal.

An asset-based approach aims to empower individuals, enabling them to be more independent and rely less on public services (again, offering a social and economic cost saving). This was an explicit finding of this evaluation as some individuals reported to have used the skills, knowledge and confidence gained from TH within the MHRP to move to other volunteering opportunities or paid employment. Fundamentally, participants expressed how being a volunteer gave them a purpose and structure to their daily life. As such, the use of TH as part of the MHRP helped them to re-engage with life, meet new people and communities, sometimes developing friendships, but most certainly resulting in a reduction in social exclusion and isolation.

Conclusion

The findings from this project indicate that using TH within an MHRP supports the recovery of volunteers, enabling them to reconnect with others through nature. The combination of TH with the social aspects of being with like-minded people provided an environment in which volunteers flourished. The flexible, yet structured, TH approach also helps individuals to regain structure in their lives, which is particularly useful for those who have been out of employment or for whom their mental health condition has meant that they have lived an isolated life. Significantly, people who attended the MHRP were treated as ‘volunteers’, not ‘service users’, and this was reflected in the ways in which people felt that they contributed to a community and project; people felt valued for what they could do and for their contribution, rather than being defined by their diagnosis and what they could not do.

The MHRP used TH to provide a nature-based intervention that effectively reduced isolation and empowered individuals’ recovery. Offering hope, empowerment and a person-centred approach, the project aligns itself with the recovery approach to mental health and wellbeing (National Institute for Mental Health in England, 2005). The findings indicated that the use of TH within the MHRP facilitated recovering a life that has meaning and is meaningful to the people who use the service (Shepherd et al., 2008). This offered hope and a sense of connectedness both to nature and other people.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

Nature-based approaches can aid recovery for people with low to medium mental health problems.

Community-based therapeutic horticulture is an effective mode of social prescribing.

Social prescribing, using therapeutic horticulture, helps people with low to medium mental health problems to re-engage with communities.

Community-based therapeutic horticulture is an effective intervention in terms of reducing social isolation for people with low to medium mental health problems.

Biography

Michelle Howarth is a Senior Lecturer in nursing in the School of Health and Society at the University of Salford, and joint lead for the pan-university ‘creative wellbeing’ research group. She is an experienced healthcare practitioner and is best known for her significant experience and expertise in engagement with community groups; for example, in leading research evaluations of the impact of therapeutic horticulture. She also has significant knowledge of applied ethics. Michelle was awarded the university’s Harold Riley award for community engagement in 2016 for her work with service users and carers, and is currently working with local community groups to help develop and establish a natural health service green network. The main focus of Michelle’s research is on the development of methodologies that can evaluate the impact of green space on the health and wellbeing of individuals and communities.

Michaela Rogers is a Lecturer in social work in the School of Heath and Society, University of Salford. She is a registered social worker with practice, teaching and research experience in a range of areas, including interpersonal violence, domestic abuse and ‘seldom heard’ groups. Michaela has published widely on issues around trans and gender diversity, as well in relation to other marginalised groups and the barriers to/enablers of social care provision. Michaela is the lead author of Developing Skills for Social Work Practice (2016) and co-edited the book Working with Marginalised Groups (2016).

Neil Withnell is Associate Dean for academic quality assurance at the University of Salford. He is a qualified mental health nurse with over 30 years of experience, and has a keen interest in all strategies to improve mental health and to the equality of mental health with physical health. Neil is the author of Family Interventions in Mental Health.

Cath McQuarrrie is a Senior Lecturer in mental health nursing at the University of Huddersfield. She is currently involved in the delivery of pre-registration nurse training and has a special interest in promoting mental health and wellbeing, recovery and developing inclusive practice. She has previously been involved in the development and delivery of a training programme to support the implementation of a health and wellbeing service within Salford, which developed coaches to work with the public on a number of health-related issues.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics

The project was approved by the University of Salford ethical approval committee, reference HSCR15-76. All participants were provided with information leaflets and informed consent was gained from all. Participants had the right to withdraw. All data were anonymised.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The project was funded by the Big Lottery Reaching Communities Fund.

References

- Begley CM. (1996) Using triangulation in nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 24(1): 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berget B, Lidfors L, Palsdottir A, et al. (2012) Green Care in the Nordic Countries – A Research Field in Progress. Report from the Nordic Research Workshop on Green Care in Trondheim. MA, USA: Health UMB, Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

- Bickerdike L, Booth A, Wilson PM, et al. (2017) Social prescribing: Less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open 7(4): 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. (2008) Basics of Qualitative Research,3rd edn, London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Dayson C, Bashir N, Bennett E, et al. (2016) The Rotherham Social Prescribing Service for People with Long-term Health Conditions, Annual Evaluation Report. Available at: https://www.varotherham.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Evaluating-Social-Prescribing-Plus-in-Rotherham.pdf (accessed 3 April 2018)).

- Department of Health (2009) New Horizons: A Shared Vision for Mental Health, London: HM Government. [Google Scholar]

- Fieldhouse J. (2003) The impact of an allotment group on mental health clients’ health, wellbeing and social networking. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 66(7): 286–296. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez MT, Hartig T, Patil G, et al. (2010) Therapeutic horticulture in clinical depression: A prospective study. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice 23: 312–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinde B, Patil G. (2009) Biophilia: Does visual contact with nature impact on health and well-being? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 6: 2332–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullone E. (2000) The biophilia hypothesis and life in the 21st century: Increasing mental health or increasing pathology? Journal of Happiness Studies 1: 293–321. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. (2010) Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 7(7): 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth ML (2012) Being Believed and Believing. In: The Impact of Delgitimization on Person Centred Care for People with Chronic Back Pain. PhD Thesis. University of Salford.

- Howarth M, Withnell N, McQuarrie C. (2016) The Influence of therapeutic horticulture on social integration. Journal of Public Mental Health 15(3): 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt R, Falce C, Crombie H, et al. (2000) Health Update – Environment and Health: Air Pollution, London: Health Education Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham C, Vangen S. (2003) Researching organisational practice through action research: Case studies and design choices. Organizational Research Methods 6: 383. [Google Scholar]

- Improvement and Development Agency (IDeA) (2010) A Glass Half-full: How an Asset Approach can Improve Community Health and Well-being, London: Improvement and Development Agency. [Google Scholar]

- MacKeith J, Burns S. (2010) The Recovery Star: Organisation Guide, 2nd edn. London, UK: Mental Health Providers Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer FS, Frantz CM, Bruehlman-Senecal E, et al. (2009) Why is nature beneficial? The role of connectedness to nature. Environment and Behaviour 41(5): 607–643. [Google Scholar]

- Mind (2013) Ecotherapy Works. Available at: www.Mind.Org.Uk/About-Us/Our-Policy-Work/Ecotherapy/ (accessed 22 August 2017).

- Mitchell ES. (1986) Multiple triangulation: A methodology for nursing science. Advances in Nursing Science 8(3): 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris N. (2003) Health, well-being and open space: Literature review. OPENspace: The research centre for inclusive access to outdoor environments, Edinburgh College of Art and Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Murali V, Oyebode F. (2004) Poverty, social inequality and mental health. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 10: 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Mental Health in England (2005) NIMHE Guiding Statement in Recovery. London: Department of Health.

- NHS England (2016) General Practice Forward View, London: Royal College of General Practitioners. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Health Scotland (2011) Asset-based approaches to health improvement. Available at: www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/17101-assetBasedApproachestoHealthImprovementBriefing.pdf (accessed 21 October 2017).

- Parahoo K. (2006) Nursing Research: Principles, Process and Issues, 2nd edn. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England (2014) Local Action on Health Inequalities: Improving Access to Green Spaces, London: UCL, Institute of Health Equity. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd S, Boardman J, Slade M. (2008) Making Recovery a Reality, London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Social Fund (2015) Investing to Tackle Loneliness: A Discussion Paper. Social Impact Bonds. London, UK: Cabinet Office. Nesta.

- South J, Higgin TJ, Woodall J, et al. (2008) Can social prescribing provide the missing link? Primary Health Care Research and Development 9: 310–318. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, et al. (2012) Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110(5): 5797–2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Westminster (2017) Making Sense of Social Prescribing, London: University of Westminster. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg A, Maas J, Verhei J. (2010) Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Social Science Medicine 70(8): 1203–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2001) World Health Report, Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]