Abstract

Background

This paper offers an understanding of the lifeworld of a person with Parkinson’s Disease derived from interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA).

Aims

The paper has two main aims: firstly, to demonstrate how a focus on individual experience chimes with and can inform current ideas of a more personalised humanised form of healthcare for people living with Parkinson’s disease; and secondly, to demonstrate how an IPA study can illuminate particularity whilst being able to make, albeit cautiously, more general knowledge claims that can inform wider caring practices.

Methods

It achieves these aims through the detailed description and interpretation of one person’s experience of living with Parkinson's disease using the IPA approach.

Results

Three analytic themes point to how the various constituents of the lifeworld, such as embodiment, selfhood, temporality and relationality are made manifest. These enable the IPA researcher to make well-judged inferences, which can have value beyond the individual case.

Conclusions

A key feature of IPA is its commitment to an idiographic approach that recognises the value of understanding a situated experience from the perspective of a particular person or persons.

Keywords: case study, chronic illness, compassionate care, lifeworld, older people, phenomenology, qualitative

Introduction

We set the scene for our interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) by situating it within contemporary demands for people- or patient-centred approaches within health and social care (Epstein et al., 2010; Williams and Grant, 1998), which have humanising values at their core. Humanisation invokes a form of care that is rooted “in an ontology of human beings as relational, experiential, valuable, respect-worthy, meaning-oriented, flawed, imperfect, vulnerable, fragile, complex, and capable of health and healing even if not capable of being cured” (Willis et al., 2008: 34). This ontology reflects the principles that inform IPA practice and points to how a humanising framework and IPA research might be used to guide and inform each other in mutually beneficial ways. Moreover, it has particular pertinence for people living with chronic neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, which has a life expectancy only slightly below that of the general population. Thus, the demands of the disease can be lived with for many years.

Humanising value frameworks mesh with current thinking and policies on how forms of care should be people-centred. What people-centred care might look like in practice includes the expert patient model, which promotes self-management to social ecological systems that emphasise the person-in-context and as part of a collaborative team with health and social care providers (Greenhalgh, 2009). It is the latter systemic approaches that chime most strongly with IPA’s view of the person and its idiographic stance to which we now turn.

Being idiographic

Phenomenological research such as IPA means taking a first-person perspective seriously because it recognises that our experiences have a quality of for-me-ness. When a person bites into a ripe peach and tastes its sweetness, they know it is themselves and not someone else who is having this experience and that, for someone else, eating the peach will be experienced differently. We have “direct acquaintance” with our experiences, albeit not infallible (Zahavi, 2008), and IPA believes that understanding this first-person givenness means doing so from the perspective of the person for whom the experience is given.

For IPA, idiography is the necessary and inevitable starting point for research because “all human knowledge is inevitably idiographic – all that is is experienced once” (Salvatore and Valsiner, 2010: 3, original emphasis) and it forms the ground for generalisation. It is through an understanding of how this event is experienced by this person at this particular time that we can make generalising moves. IPA aims to understand how a particular lived situation is experienced by a particular person at a particular time whilst recognising that this experience is indivisibly woven into the person’s lifeworld. By lifeworld we mean the world that we experience, that is replete with meaning for us and in which people, events, and so on matter to us. IPA research that reflects on individual’s lifeworlds, attempting to grasp what it is that matters, can make a valuable contribution to developing forms of people-centered care. (See Eatough, 2017; Eatough & Smith, 2017, for further development of IPA and idiography.)

Moving beyond the idiographic to the general

Heidegger draws attention to how our worlds are both distinctive yet shared: “The surrounding world is different in a certain way for each of us, and notwithstanding that we move in a common world” (Heidegger, 1982: 164).

Each of us inhabits a subjective situated world that shares “ever-present characteristics” (Ashworth, 2006: 215) with the situated worlds of others. These characteristics are universal features of the lifeworld and include the many projects we commit to and care for, our embodied, temporal and relational natures, and how we are always attuned to the world in specific ways.

This means that although the singular experienced situation is the starting point for IPA (say, a person living with chronic pancreatitis), typically, this is followed by an examination of several experiences to see what they share and what they might tell us about the make-up of the experience more generally (such as how life-limiting changes such as diet have an impact upon family and social relationships) before ending with a more philosophical or theoretical reflection, which might ask what these experiences say about the nature of human being (we are relational beings) and for the possibilities of change to exist (Halling, 2008). This move from the particular to the general is a cautious and considered undertaking and, at all times, IPA seeks to retain the rich and personal detail of the particular whilst pointing to ways in which the particular illuminates (and is illuminated by) characteristics of the lifeworld that are common to us all. These lifeworld features provide a useful lens through which to examine the concrete particulars of an individual situation and say something about its more universal features.

Epistemological stance and methodological process

In this section, rather than discussing the principles of IPA and how they are typically employed (although see Eatough & Smith, 2016 for a general account of how to do IPA and Eatough & Shaw, 2017 for a specific example) we have chosen to give a flavour of our methodological stance and process. The principles and steps of IPA are well documented and accessible; what is sometimes missing is how they are put into action and realised in the research.

Using IPA involves approaching the research process with a purposeful phenomenological and hermeneutic orientation; this involves thinking, making decisions and executing them in a way that fits with such a stance. IPA’s central concern is with lived experience, which we understand as a form of “concernful involvement” (Yancher, 2015: 109) by people for whom the world and the events, objects and people within it matter to them and show up as things to be reflected on and made sense of. Here, it is Barbara’s (pseudonym) experience of living with Parkinson’s disease that we are interested in.

One way we aimed to be phenomenological towards Barbara’s lived experience was to think carefully about the language we used to think about various aspects of the research process. For example, rather than “interviewing” our participant, we saw it as a conversation between two people, both bringing something to the encounter but with different roles: Barbara as the experiential authority on the situation to be talked about and one of us (First author) as enabling Barbara to describe her experience and focus on what was important to her. We deliberately cultivated a sense of language as practical engagement both in the conversation and throughout our collaborative process of understanding Barbara’s experience of living with Parkinson’s disease.

Rather than thinking we were doing “data analysis” in some formal sense. We reminded ourselves of how the prescribed steps in IPA are asking us to reflect on what people tell us through a turning away from facts to meanings; from what Barbara is living through to how she is living through it. We maintained this focus by asking ourselves how it came to be this “what” for Barbara, out of all the possible “whats” (Churchill, 2012); for example, how she described feeling frustrated when someone else might have described feeling resentful. From Barbara’s descriptions, we reflected on how she experienced this frustration by attending to all the other things she told us about – her past history, her present and future concerns, her relationships, and so on.

The key guiding tenet that underpins this process is the view that IPA researchers are existential world-disclosers (Yancher, 2015) who hold the view that when we examine and scrutinise lived situations and experiences, phenomena are disclosed (or concealed) through language that has the “power to make things manifest” (Taylor, 1985: 238).

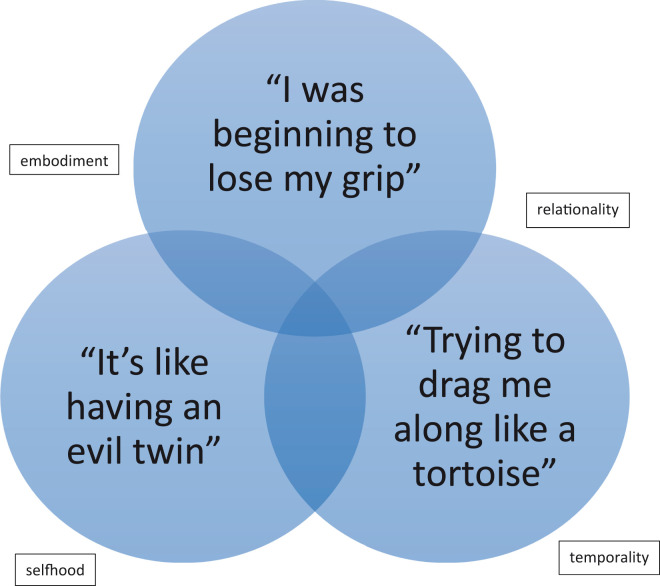

More formally, we worked through the IPA stages, at first working independently having agreed that we would each spend time immersing ourselves in Barbara’s story. We each made detailed notes and comments aiming to capture what mattered to Barbara as well as documenting our early sense-making. At this stage, we aimed to be open to many possible meanings, keeping our themes provisional and emergent. This was followed by discussions where we reflected on these meanings, moving between them and the transcript itself to ensure that we did not lose sight of Barbara and her lifeworld. These collaborative reflections and the formal analysis led to a structure comprising three experiential themes: “I was beginning to lose my grip,” “It’s like having an evil twin” and “Trying to drag me along like a tortoise.” Using a lifeworld lens, these themes speak to embodiment, selfhood, relationality and temporality. These lifeworld aspects do not exist discretely; rather, they connect strongly with each other so that we can speak of an embodied temporality, a relational temporality and an embodied self, which we hope to demonstrate in the next section. Figure 1 presents this thematic structure.

Figure 1.

Analytic thematic structure.

Our interpretative phenomenological narrative

At the time of the interview, Barbara was 61 years old and had been living with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease for four years. Barbara’s personal and unique stance towards having Parkinson’s disease, which we elaborate on with the second theme, is that Parkinson’s disease is a worthy adversary. She is both realistic about what is to come in terms of the limitations the disease will impose on her but she is determined to meet them head on and develop strategies to cope with them. For example, she has bought a child’s toothbrush because

it’s fatter to hold, it’s an electric one so that makes it easier to clean. I’m trying to think ahead whenever I meet a problem, how am I going to deal with a problem, how am I going to sort it out before it actually gives me grief.

It is these sorts of actions that help Barbara regain some sense of the unthinking practical engagement of daily life.

Included in this narrative are some brief reflections drawn from another case study conducted by the first author (Eatough, 2017). They are included to illustrate some of the ways in which IPA might move from the particular towards the general both empirically (the slow accruing of individual cases) and theoretically (through the application of relevant lifeworld characteristics).

“I was beginning to lose my grip”

Barbara uses the word “grip” multiple times to convey how, in a very tangible sense, she experiences her body as recalcitrant; she has difficulty signing the consent form, saying, “The hands aren’t very good today, unfortunately the grip’s not there today.” She describes how this weakening grip made her feel when she was still working: “I was getting slower and slower with my hands and I realised I wasn’t packing properly, I couldn’t grip things properly and carry a tray properly, I felt vulnerable.” Parkinson’s disease limits Barbara’s ability to carry out everyday taken-for-granted activities, literally loosening her grip on them. Prior to diagnosis, she felt that she was not only losing her physical grip on things but also psychologically because she did not understand what was happening to her although she “knew there was something wrong”:

I was glad to have a name on [sic] it. I thought I was going nuts, I really did think I was beginning to lose my grip because I was crying. Well, I wasn’t crying, I would get up in the morning and go make a cup of tea and my eyes would start to cry. I didn’t feel unhappy, sad or upset in any way but my face would cry…I’d just be standing there having a cup of tea and start to cry and I thought this is mad, I’m losing my grip.

Barbara’s crying is probably an ocular abnormality and a non-motor symptom of the Parkinson’s; what is of interest here is Barbara’s palpable sense that she was going mad, not only losing her physical grip but also her grip on reality, which disappeared on diagnosis:

I: So, you said it was almost a relief?

B: Oh yes, to know there was something wrong with me, that I wasn’t going loopy, you know that I was losing my grip.

The different ways that “grip” is used conveys both (a) a strong sense of how Barbara’s embodied unreflective “ready-to-hand” relationship with significant objects that matter in a practical sense is disrupted and (b) how not knowing what is wrong is an unnerving experience that shakes one’s reality. A diagnosis of Parkinson’s allows Barbara to find a place for the disease in her life.

Barbara no longer has a harmonious relationship with her body; rather, daily tasks assume a disproportionate significance:

Trying to get washed in the morning it’s a Herculean task, trying to get washed, trying to brush my teeth…you’re trying to have a wash and what you do you smack yourself, I can’t actually do it…it’s very very hard…it’s a bit hit and miss.

Elsewhere, as previously mentioned, one of us has drawn attention to how Parkinson’s renders one’s body conspicuous. Like Barbara, (Elsa) experienced her body as meddlesome and unable to enjoy the unreflective movement of the “absent” body we take for granted when we are well (Leder, 1990) Svenaeus’s idea of “unhomelikeness” was drawn on to highlight how the disease altered (Elsa’s) embodied self so that her world felt unfamiliar because she had lost her sense of unreflective engagement with daily tasks. This thinking can be extended to Barbara. We suggest that, for both women, these experiences emphasise the need for a caring-for-living approach and not just a caring-for-disease one. For example, helping people with Parkinson’s disease to develop ways in which, at least part of the time, they can experience their bodies as familiar and unobtrusive.

“It’s like having an evil twin”

As previously mentioned, there are many ways a person with Parkinson’s disease might come to terms with its presence in their lives and develop strategies to cope with it. Barbara treats Parkinson’s as an opponent to battle with:

I seem to be battling all the time, battling with Parkinson’s, fighting it, fighting it all the time…. I’ve always met things head on, I’d rather know and deal with it, that kind of thing, [I] don’t sweep things under the carpet I’ll face it and sort it no matter how horrible it is.

Here, Barbara gives us an insight into her way of perceiving and living in the world: adversity is to be faced and challenges met. This coping style is not for everyone and is a reminder that one of the challenges for person-centred care is how to develop personalised forms of care that make use of personal knowledge, personal history and past personal experience and value their contribution. At several points throughout the interview Barbara described how she has always been “the Boss” and how she does not “like to feel useless because I’ve always been very capable.” Understanding the importance of this sense of self for Barbara should be relevant for how she is cared for – not only by healthcare professionals but by family and friends also. Her particular approach needs to be acknowledged for how it might help (and hinder) how she lives with the demands of Parkinson’s.

Barbara invokes an intriguing metaphor to describe her relationship with the disease:

It’s like having an evil twin. I go to bed at night and I think tomorrow morning, I’m going to get up and I’m going to hoover the floor and I’m going to do some washing. I get up in the morning and I go and get the hoover out and I can’t do it. I just stand there, I know what to do, I know exactly how to hoover but my hands won’t do it…it’s things like that, I feel like I’ve got this evil twin that won’t let me do what I want to do, it stops me when it finds out what I’m trying to do.

Likening Parkinson’s to having an evil twin suggests that an intimate relationship exists between Barbara and the disease; one that is both Barbara and not-Barbara. This evil twin or alter-ego stands in opposition to Barbara in a relationship of radical alterity because of the complex relationship between her changing unruly body and how these changes affect and erode her sense of self as capable, responsive and “a strong character.” We wonder if this vivid metaphor serves an explicit purpose for Barbara in that it acts as a spur for her to be resourceful in the face of Parkinson’s: to acknowledge the limitations it brings, yet at the same time to envisage new possibilities of being. Thus, the evil twin might be a motivating force for Barbara, an interpretation which appears to resonate with Barbara’s personal take on the disease as a worthy adversary.

Barbara believes it is her responsibility to be proactive, saying “that it is my responsibility to do the best for me that I can.” To this end, she does things which help to alleviate this sense of an evil twin as part of her embodied self. She has found that both music and dance can give her a sense of release from her restrictive and over-thinking body so that she regains a sense of what Sartre called the body as “passed-over-in-silence” (Sartre, 1956) and her Parkinson’s fades out of awareness. For example, at times when Barbara loses control of her movement, especially when walking on the flat, she sings a Bee Gees song out loud, which works even if only for a short time:

I tend to trip on my toes so I have to think in my head, you’ve seen how I walk, I’m quite shaky, a bit unsteady but if I start singing Night Fever in my head then I can walk fine. It’s really crazy, you’ve seen how stiff and awkward I am and I can’t get my balance and stuff. I just think in my head Night Fever you know, it’s amazing and then I stop, I’m back to where I was I can only keep up for a little while, it’s crazy.

Similarly, Barbara describes attending a dance class organised by her Parkinson’s support group:

He [the instructor] got people up to dance who were very stiff and awkward and that was very good. I’d love to see something over here [where she lives], part of the physio help, a dance class for Parkinson’s to go to because it makes you feel the relief when it happens, the relief it’s not in your head, it’s the restrictions are lifted from your body, you can do it in the way you used to do it.

In these circumstances, Barbara’s body is present as her body, rather than the alien body of the evil twin she perceives it to be when Parkinsonian symptoms dominate.

“Trying to drag me along like a tortoise”

This theme exemplifies our earlier claim of how it is possible to speak of deep interconnections between the various lifeworld characteristics, in this case temporality and relationality. Lived time is a consequence of the relationship between the embodied subject described previously and the world; it is a “situational sensing of experienced time” (Wyllie, 2005: 174). For instance, a tedious and long car journey seems “to last for ever” in contrast to a snatched romantic lunch that “flies by.” This sense of experienced time is captured in Barbara’s description of herself as a tortoise, which conjures up a sense not only of her movement as slow and laborious but also her body as cumbersome.

Time is foregrounded in how Barbara has to structure it in the face of her Parkinson’s. She is slow when she first gets up and as the morning progresses, she improves, but by the late afternoon she describes herself as “wearing down again.” Consequently, she needs a routine that enables her to get things done when she can; spontaneity is a thing of the past and she has no choice but to allow time for activities that were once completed without a thought:

It takes me quite a while in the morning, it takes me quite a while to get dressed. I can’t move because I am very stiff and it does take me 10 minutes to get dressed, or if I do it in stages, it can take half an hour.

Barbara’s descriptions illuminate the complex connectivity between a self which is always embodied, temporal and relational. Several times she contrasts a former self who “was always dashing here and there all the time” with the person who now finds that activities such as going to the shops take “longer and longer.” Not only is this slowing down frustrating for Barbara, she is acutely aware of its effect on other people:

The frustration is bad enough for me, it must be horrendous for Peter (her son) because he’s much quicker and on the ball than I ever was and he has to kind of drag me along, trying to drag me along like a tortoise is a bit galling.

We suggest that there are at least two meanings for Barbara’s use of the word drag. First, Barbara experiences her slow body as something to be dragged along, making mundane tasks arduous and time-consuming. Second, she is a drag in that she feels like a drag for her family and friends, and this interpretation receives support when she talks of how she limits going out with friends:

I was always out with my friends, you know all those kinds of things, visiting garden shows, garden centres…and all those things have been very much curtailed because I’ll slow them down and although they’re quite happy for me to go with them, I know that I’m going to be a drag on them.

There is a strong sense that being a drag means being a burden and Barbara makes this connection explicitly when talking of how she has started to defer responsibility to her children:

I think there comes a time when you need to do that anyway, you need to let the children, well they’re not children anymore, you need to step back, it’s their turn to take on some of their responsibilities and that kind of thing so I don’t feel bad about it, I just hope that I’m not becoming a burden, you know I’m not becoming somebody who’s becoming a drag.

Similarly, Elsa described feeling a burden on her family and friends. Etymologically, a burden is a weight or duty to be borne and speaks to how living with Parkinson’s can distort one’s roles and relationships, giving rise to feelings of a one-sided dependency and a desire to avoid or withdraw from people, leading to social isolation. For both women, these relational vulnerabilities need to be recognised by those caring for them and support given to help them regain some sense of relational reciprocity.

Concluding comments

The idiographic work presented here chimes with a growing demand for caring practices that are tailored to the needs of the individual person. What these needs might be come to light through qualitative approaches such as IPA. This might mean, for example, recognising that although people with Parkinson’s want treatment that diminishes or even removes their motor symptoms, they also want practical support to help them with the often arduous task of daily living. For these concerns to be heard and valued means that a more reciprocal and human relationship between the individual person and those that care for them is required. People are always more than their symptoms, their disease and “the quality of the journey is just as important as the destination” (Todres et al., 2009: 75). When the lifeworlds of people like Barbara are diminished and their well-being possibilities reduced, then the challenge becomes how we can ensure a form of care that enables them to flourish and maintain a sense of existential legitimacy (Craig, 2013).

Humanising care involves moving beyond expert patient programmes (Fox et al., 2005; Franek, 2013) that emphasise patient self-management and “buddy” support systems (Epping-Jordan et al., 2004) – as important as these might be for a more multifaceted form of care – and towards humanising forms of care that bring “our ways of knowing into closer harmony with our ways of being in the world” (Buttimer, 1976: 278). Barbara utilises her personal life skills and is resourceful in order to enhance her own self-care and giving her a sense of control and purpose. The conflict with her evil twin, which she uses as a spur, exemplifies this. This store of personal knowledge is invaluable and central to a truly tailored and person-centred care; a reciprocal relationship between those providing care and those receiving it, which emphasises not what has been lost for the person but what they have got and can become.

Living longer lives with chronic conditions such as Parkinson’s disease puts increasing strain on health and social care systems worldwide and some might say that a humanising care framework based on utilising reciprocal knowledge is impossible. However, we agree with Todres et al. (2009) that this is a luxury that we can and must afford.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

IPA research can be part of the endeavour to transform healthcare culture into a humanising practice, which emphasises peoples’ lifeworlds and the power of interpretative understanding.

Collaborative approaches that utilise reciprocal knowledge and decision-making may require the dropping of “a professional front,” acknowledging a tension between the voice of medicine and health sciences and that of the lifeworld (Barry et al., 2001). However, achieving a deeper understanding and appreciation of peoples’ unique personal knowledge, skills and experience may be valuable in achieving mutually agreed healthcare practices with better adherence and outcomes.

Nurses are trained to listen and communicate with empathy – complex skills that can be lost in a pressurised task-oriented environment with little time or energy for emotional investment. A recognition of the importance of these skills not only serves to strengthen the relationship between practitioners and those involved in their care, but can also enhance job satisfaction for health professionals.

Biography

Virginia Eatough’s research interests focus on understanding emotional experience from a phenomenological psychology perspective. She uses a range of phenomenological approaches and has particular expertise with interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA). Current projects include happiness, work engagement and women with breast cancer and neurophenomenology.

Karen Shaw is a research nurse specialist in movement disorders as well as being the liaison person for brain donors and their families at the Queen Square Brain Bank for Neurological Disorders.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics

Ethical approval was given by Birkbeck, University of London, UK.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ashworth P. (2006) Seeing oneself as a carer in the activity of caring: Attending to the lifeworld of a person with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being 1: 212–225. [Google Scholar]

- Barry CA, Stevenson FA, Britten N, et al. (2001) Giving voice to the lifeworld. More humane, more effective medical care? A qualitative study of doctor-patient communication in general practice. Social Science & Medicine 53(4): 487–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttimer A. (1976) Grasping the dynamism of the lifeworld. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 66(2): 277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill SD. (2012) Teaching phenomenology by way of “second-person perspectivity” (from my thirty years at the University of Dallas). The Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 12(3): 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Craig E. (2013) One-ing and letting-be. The Humanistic Psychologist 41(3): 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Epping-Jordan JE, Pruitt SD, Bengoa R, et al. (2004) Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. BMJ Quality & Safety 13(4): 299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eatough V (2017) What can’t be cured must be endured: Living with Parkinson’s disease. In: KT Galvin (Ed.) Routledge Handbook of Well-being. London: Routledge, pp. 173–181.

- Eatough V and Smith JA (2017) Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: C Willig and W Stainton Rogers (Eds), Handbook of Qualitative Psychology 2nd Edition. London: SAGE, pp. 193–211.

- Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, et al. (2010) Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Affairs 29(8): 1489–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA and Eatough V (2016). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In A Coyle and E Lyons (eds), Analysing Qualitative Data in Psychology: A Practical & Comparative Guide 2nd Edition. London: SAGE, pp. 50–67.

- Eatough V and Shaw K (2017) ‘I’m worried about getting water in the holes in my head’: a phenomenological psychology case study of the experience of undergoing deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease. British Journal of Health Psychology 22(1): 94–109. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fox NJ, Ward KJ, O’Rourke AJ. (2005) The ‘expert patient’: Empowerment or medical dominance? The case of weight loss, pharmaceutical drugs and the Internet. Social Science & Medicine 60(6): 1299–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franek J. (2013) Self-management support interventions for people with chronic disease: An evidence-based analysis. Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series 13(9): 1–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T. (2009) Chronic illness: Beyond the expert patient. British Medical Journal 338(7695): 629–631. [Google Scholar]

- Halling S. (2008) Intimacy, Transcendence, and Psychology. Closeness and Openness in Everyday Life, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger M. (1982) The Basic Problems of Phenomenology, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leder D. (1990) The Absent Body, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore S, Valsiner J. (2010) Between the general and the unique. Overcoming the nomothetic versus idiographic opposition. Theory & Psychology 20(6): 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre JP. (1956) Being and Nothingness, New York: Philosophical Library. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. (1985) Human Agency and Language: Philosophical Papers I, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Todres L, Galvin K, Holloway I. (2009) The humanization of healthcare: A value framework for qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being 4(2): 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Grant G. (1998) Defining ‘people-centredness’: Making the implicit explicit. Health and Social Care in the Community 6(2): 84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis DG, Grace PJ, Roy C. (2008) A central unifying focus for the discipline. Facilitating humanization, meaning, choice, quality of life, and healing in living and dying. Advances in Nursing Science 31(1): 28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie M. (2005) Lived time and psychopathology. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology 12(3): 173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Yancher SC. (2015) Truth and disclosure in qualitative research: Implications of hermeneutic realism. Qualitative Research in Psychology 12(2): 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi D. (2008) Subjectivity and Selfhood. Investigating the First-Person Perspective, London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]