Abstract

Combined precursor isotopic labeling and isobaric tagging (cPILOT) is an enhanced multiplexing strategy currently capable of analyzing up to 24 samples simultaneously. This capability is especially helpful when studying multiple tissues and biological replicates in models of disease, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Here, cPILOT was used to study proteomes from heart, liver, and brain tissues in a late-stage amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 (APP/PS-1) human transgenic double-knock-in mouse model of AD. The original global cPILOT assay developed on an Orbitrap Velos instrument was transitioned to an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos instrument. The advantages of faster scan rates, lower limits of detection, and synchronous precursor selection on the Fusion Lumos afford greater numbers of isobarically tagged peptides to be quantified in comparison to the Orbitrap Velos. Parameters such as LC gradient, m/z isolation window, dynamic exclusion, targeted mass analyses, and synchronous precursor scan were optimized leading to >600 000 PSMs, corresponding to 6074 proteins. Overall, these studies inform of system-wide changes in brain, heart, and liver proteins from a mouse model of AD.

Graphical Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is both a neurodegenerative and metabolic disease, most commonly characterized by the deposition of amyloid beta (Aβ) senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau. While AD affects the brain, it also has implications in peripheral organs. For example, cardiovascular disease1–4 is a major risk factor for AD, as well as type-2 diabetes,5–7 hypertension,8–10 obesity,11,12 and high cholesterol.13 These comorbidities suggest that peripheral organs (e.g., heart and liver) may contribute to disease pathogenesis and that a comparative analysis of these tissues to the brain may give insight into their contributions in AD.

In our laboratory, studies in peripheral tissues, such as the liver,2 have been performed with 14-month-old amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 (APP/PS-1) mice. APP/PS-1 (hereafter referred to as AD) mice are a double-transgenic strain with mutant APPswe and PS1de9 genes.14 Proteins related to fatty-acid and pyruvate metabolism were elevated in liver from AD mice (compared to WT), suggesting development of ketone bodies.15–17 This is supported by metabolomics analyses.17 In addition, elevated levels of glucose synthesis proteins were observed,15 consistent with glucose storage. High throughput strategies that allow multiple tissues or alternatively multiple time points, especially for advancing AD understanding, are desirable.

Our laboratory18–20 and others21–24 have pushed the limits of sample multiplexing by employing enhanced labeling strategies.25 Combined precursor isotopic labeling and isobaric tagging (cPILOT) uses amine-based chemistry to chemically label primary amines of N-termini and lysine residues.18 In order to maximize the number of quantified peptides and broaden the types of analyses that can be studied, different sample preparation strategies and data acquisition methods (e.g., gas-phase fractionation, two-tiered data-dependent acquisition (DDA), and MS3 fragmentation26–30) were developed on Orbitrap instruments. However, there are some limitations of conducting a cPILOT analysis on an Orbitrap Velos that limit the detection of dimethylated peptide pairs and detection of signal for all reporter ion channels used.

The goal here was to evaluate and optimize MS acquisition parameters for cPILOT on a Fusion Lumos and compare them to those on the Orbitrap Velos. The resulting method was applied to an AD mouse model to study disease pathogenesis across the brain and periphery (i.e., liver and heart). These studies provide insight into the benefits and challenges of using different Orbitrap instruments for cPILOT analysis and lay the foundation for using enhanced multiplexing to understand changes in the peripheral and brain proteomes in AD.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

APP/PS-1 male mice (B6.Cg-Tg(APPswe, PSEN 1dE9)-85Dbo/Mmjax, stock no. 005864, genetic background: C57BL/6J) and heterozygous controls were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and housed in the Division of Laboratory Animal Resources at the University of Pittsburgh. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh. Mice were fed standard Purina rodent laboratory chow ad libitum and kept in a 12 h light/dark cycle. Brain, heart, and liver tissues were harvested from 14-month-old APP/PS-1 [referred to as AD] (N = 6) and WT (N = 6) mice and stored at −80 °C. Brain, heart, and liver tissues (i.e., 60–80 mg) were homogenized (1× PBS w/PBS w/8 M urea) with a mechanical homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, LLC) to generate tissue lysates. Protein extraction, concentration, and digestion were executed as previously described.31 Peptides were then labeled by cPILOT as previously described.15 Labeled peptides were pooled to have one sample (per batch) and prepared for either SCX fractionation (analyses 2 and 3) or dissolved in 0.1% FA and directly subjected (analysis 1) to instrument analysis (Figure 1). Three independent 12-plex cPILOT batches were performed to cover all 36 samples. Peptides labeled by cPILOT (samples 2 and 3) were fractionated according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Protea Biosciences). Fractionated peptides were dried down by centrifugal evaporation and dissolved in 0.1% FA. Peptides were analyzed using three methods (analyses methods 1–3) on either an Orbitrap Velos or Orbitrap Fusion Lumos (Supplemental Methods). Specifically, analyses 1 and 2 were performed on the Orbitrap Fusion Lumos, while analysis 3 was performed on the Orbitrap Velos. Raw files were analyzed with Proteome Discoverer v. 2.1 and 2.2. (Supplemental Methods). Reporter ion values were normalized using internal reference scaling,32 and a one-way ANOVA was performed (p < 0.05). Multiple hypothesis testing such as Bonferroni correction is rather conservative and may not be ideal for this and other proteomics data sets;33,34 thus, it was not employed. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [1] partner repository with the data set identifier PXD012133. Lastly, brain, heart, and liver tissues from AD and WT mice were used for verification by Western blot (Supplemental Methods).

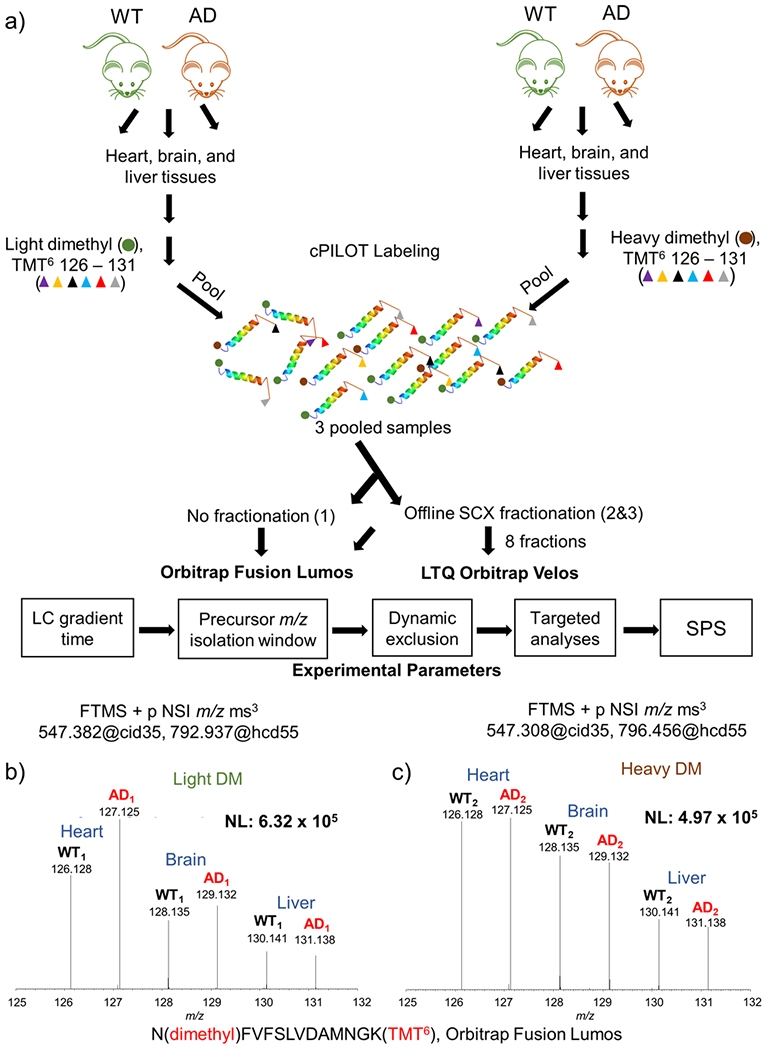

Figure 1.

Experimental workflow and sample data. (a) Protein (100 μg) was extracted from brain, heart, and liver tissues from 14-month-old APP/PS-1 (N = 6) and wild-type controls (N = 6). Peptides generated from protein digestion were labeled via cPILOT, pooled, and separated by off-line SCX fractionation and reversed-phase HPLC. Fractions were analyzed on either an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos or LTQ Orbitrap Velos MS. Experimental parameters such as LC, precursor m/z isolation window, dynamic exclusion, targeted analyses, and SPS were evaluated and optimized on the Fusion Lumos. Reporter ions (i.e., 126–131) corresponding to N(dimethyl)-FVFSLVDAMNGK(TMT6) were detected on the Orbitrap Fusion Lumos. (b) Light and (c) heavy dimethylated peptides were detected in both phenotypes, and all tissue types and correspond to malate dehydrogenase.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Below, we describe systematic testing of the performance of the Fusion Lumos to study system-wide changes in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model using a global cPILOT approach (Figure 1a, see Experimental and Supplemental Methods for details).

An initial demonstration that cPILOT successfully worked in this application is shown in Figure 1b,c. Two peptides that belong to malate dehydrogenase were dimethylated at the N-terminus and tagged by TMT6-plex at lysine residues. The MS3 spectra for N(dimethyl) FVFSLVDAMNGK(TMT6) for light (Figure 1b) and heavy (Figure 1c) dimethylated pairs have reporter ions detected in channels m/z 126–131. Among all proteins quantified in both the Fusion Lumos and the Orbitrap Velos (Supplemental Figure S1), it is apparent that reporter ion signals are ~2 orders of magnitude higher in the Fusion Lumos data compared to those from the Orbitrap Velos.

Evaluation of LC Gradients and Precursor Isolation Windows.

Upon increasing the gradient time from 105 to 150 min, the number of protein identifications and PSMs increased ~1.3× (Supplemental Figure S2a,b), and the average numbers of quantified spectra increased by 1.5× (Supplemental Figure S2c). In order to optimize numbers of spectra, peptides, and proteins detected, a 150 min gradient time was used.

For cPILOT analyses, it is most critical that both peaks in a light and heavy dimethylated pair are isolated at the precursor stage for MS/MS and subsequent MS3 fragmentation. The considerations for changing the isolation window are that interfering species can be coisolated from the precursor MS spectra if the window is too large, whereas lower signal intensities for precursors are carried forward into MS/MS if the isolation window is too small.23 Most peptides for this data set have charge states of 2 (48%) or 3 (43%). Thus, isolation windows of m/z 2.5 or less are most appropriate for peptides with a charge state of 2 and will need to be even less to accommodate peptides with a charge state of 3.

The isolation window in these experiments is also impacted by the fact that heavy dimethylated peptides have a peak that appears 7 Da away from the light dimethylated peak and is often isolated as the precursor peak in the heavy cluster. In addition, the discrepancy between the number of protein and peptide identifications between light and heavy dimethylated samples is due to the instrument selection of light-labeled peaks more frequently than heavy-labeled peaks due to intensity differences, ultimately resulting in higher numbers of protein IDs from light-dimethylated peptides.31 Increasing the isolation window allows more of the isotopic cluster to be isolated, thus increasing the signal for MS/MS spectra and subsequent MS3 reporter ion signal. Additionally, this isolation window ensures that we increase the likelihood of isolating the heavy dimethylated peptides (+7 and +8 Da) resulting in the full multiplexing capabilities of cPILOT. When this was widened from m/z 0.7 to 2.0, a decrease of 1212 and 804 proteins to 1054 and 690 proteins from light and heavy dimethylated peptides occurred, respectively (Supplemental Figure S2a,b). On the other hand, the number of quantified spectra increased from 57 337 to 59 517 (Supplemental Figure S2c), which is likely a result of wider windows leading to more ion signal. In addition, this change was found to be statistically significant. Thus, an isolation window of m/z 2.0 was used to balance the trade-off in identifications vs quantifiable information.

Evaluation of Dynamic Exclusion.

Next, the effects of dynamic exclusion on the number of peptides and proteins identified (Supplemental Figure S3) was tested. The precursor isolation width was set to m/z 2.0, and the dynamic exclusion ranged from 0 to 10 and 20 s. The quality of identified proteins was categorized by a low (FDR > 5%), medium (FDR < 5%), or high (FDR < 1%) confidence parameter from Proteome Discoverer. A one-way ANOVA analysis showed that protein identifications from these time points changed significantly. As the dynamic exclusion was reduced from 20 to 10 and 0 s, a larger percentage (36 vs 69%) of low confidence proteins were identified, while lower percentages (53 vs 22%) of high confidence proteins were identified from light dimethylated peptides. The same trend was also observed for proteins identified from heavy dimethylated peptides. Thus, a dynamic exclusion time of 20 s was selected.

Evaluation of Targeted Mass Analysis Nodes.

Previously, we demonstrated that the overall number of protein identifications with trypsin compared to Lys-C is higher.27 However, a limitation of using trypsin is that it leads to R-terminated peptides that do not yield quantitative information for cPILOT.27 In order to maximize the number of proteins with reporter ion signals in all channels, more instrument time should be spent acquiring spectra from K-terminated peptides. Targeted inclusion/exclusion nodes were evaluated on their ability to increase the number of dimethylated peptide pairs, especially those that are K-terminated. The following targeted mass nodes (Figure 2, Supplemental Table S2, Supplemental Methods) were tested: targeted mass trigger, targeted mass difference, targeted isotopic ratio, and targeted mass (exclusion and inclusion).

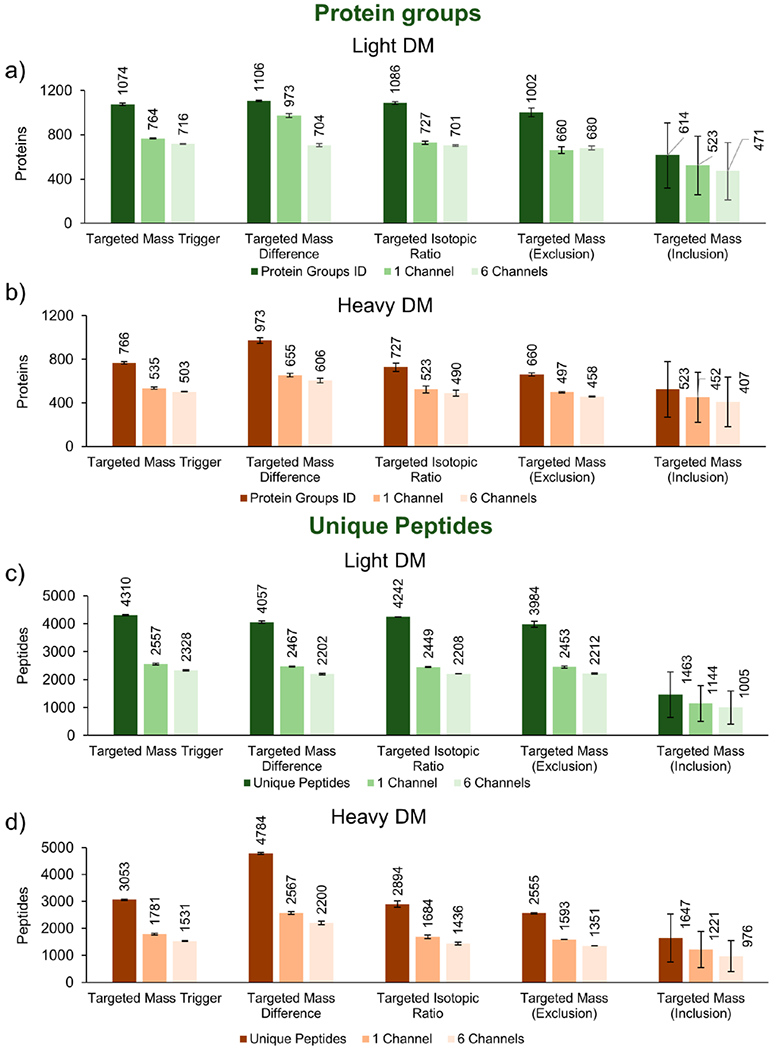

Figure 2.

Protein and peptide identifications of light and heavy dimethylated peptides (targeted mass analyses nodes). Targeted mass analyses nodes were employed to assess the numbers of (a,c) light and (b,d) heavy proteins and peptides identified, with specific emphasis on lysine-terminated peptides, which carry TMT6-plex reporter ion information. A further comparison displays proteins quantified in at least one reporter ion channel or in all six channels. Thus, the best method for conducting targeted cPILOT experiments is the targeted mass difference node.

Light dimethylated peptides had similar protein and peptide identifications (Figure 2a,c) across targeted mass trigger, targeted mass difference, targeted isotopic ratio, and targeted mass exclusion tests. In the targeted mass inclusion run, however, there was a substantial decrease in protein groups and peptides identified. Among heavy dimethylated samples (Figures 2b,d), the targeted mass difference method identified ~2–4× more PSMs, peptides, and protein groups than the other nodes (Supplemental Table S2) (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). In addition, the number of peptides and proteins quantified in at least one or in all six channels was consistent with proteins identified across the nodes, although with lower numbers quantified than identified (Figure 2).

The number of proteins quantified in at least a single reporter ion channel or in all six reporter ion channels was used as a measure of quantification performance. Across all of the targeted mass nodes, the number of proteins quantified in all six channels was lower than that in a single channel for each node (Supplemental Table S3). The targeted mass difference node did indeed have the greatest number of proteins that were quantified in all six channels (Supplemental Table S3) and that came from K-terminated light and heavy peptides combined (Supplemental Table S2).

Targeted mass exclusion reduced the number of R-terminated peptides compared to targeted mass trigger, mass difference, and isotopic ratio nodes; however, it did not remove all R-terminated peptides. Targeted mass inclusion dramatically removed R-terminated peptides and selected a high percentage (94–97.2%) of K-terminated peptides. On the other hand, only 37% (light) and 58% (heavy) peptide m/z values on the inclusion list were selected (data not shown). In addition, K-terminated peptides not on the inclusion list were not eligible for selection, further decreasing the potential number of peptide identifications. For these reasons, this node led to the lowest number of proteins quantified, and thus, it is not suitable for global cPILOT analyses.

Evaluation of the Synchronous Precursor Selection Node.

SPS-MS3 allows 2–20 fragment ions to be selected for further fragmentation, thus increasing reporter ion signal substantially in comparison to single-notch MS3. A range of 4–10 SPS ions were tested in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of SPS Parameters on Number of Proteins Identified

| protein groups |

proteinsb: one channel (%) |

proteinsc: six channels (%) |

MS/MS spectra |

quan. spectra |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPS-Na | light | heavy | light | heavy | light | heavy | light/heavy | light/heavy |

| 4 | 1051 ± 29 | 748 ± 43 | 725 ± 12 (69) | 540 ± 18 (72) | 682 ± 7 (65) | 501 ± 18 (67) | 116 113 | 59 713 |

| 6 | 1042 ± 1 | 722 ± 1 | 729 ± 6 (70) | 517 ± 2 (72) | 707 ± 8 (68) | 492 ± 6 (68) | 116 017 | 59 528 |

| 8 | 1077 ± 12 | 735 ± 13 | 760 ± 8 (71) | 532 ± 8 (72) | 733 ± 13 (68) | 513 ± 3 (70) | 113 097 | 57 995 |

| 10 | 1056 ± 25 | 702 ± 35 | 770 ± 28 (73) | 514 ± 29 (73) | 756 ± 25 (72) | 509 ± 28 (73) | 113 266 | 58 131 |

The number of fragment ions used for synchrous precursor selection (SPS).

The number and percentage of proteins quantified in at least one reporter ion channel.

The number and percentage of proteins quantified in all reporter (i.e., 126–131) ion channels.

Proteins were quantified if the S/N ≥ 10 for a given reporter ion channel and the minimal signal was above the set isolation threshold of 50%. Results from a one-way ANOVA showed that changes in the number of identified proteins were similar; therefore, this parameter was assessed on the percentage of quantified proteins. Increasing the number of SPS ions from 4 to 10 increased the percentage of quantified proteins across all channels from 65 to 72%. SPS-4 generated the largest number of MS/MS (116113) and, more importantly, quantified spectra (59 713) compared to SPS-10. SPS-10, however, had the greatest number of proteins with data in six channels and was thus selected for further experiments.

Recommended Parameters for cPILOT.

Overall, the targeted mass difference node and SPS-N parameters were most critical to improving the effectiveness of cPILOT analysis on the Fusion Lumos. The targeted mass difference node increased the percentage of light and heavy dimethylated peptide pairs to ~70–80%, thus increasing the amount of quantitative information gained about the respective samples. In addition, the use of SPS-MS3 increased the percentage of proteins quantified in all channels by ~20% in comparison to single-notch MS3 and improved the quantification of lower abundant proteins. It also helps to use a longer gradient (e.g., 120–150 min), a wider precursor isolation width (i.e., 2 m/z) to scan both +7 and +8 Da heavy dimethylation peaks, and a longer dynamic exclusion time (i.e., 20 s). These parameters especially increased the probability of selecting and quantifying pairs of dimethylated peptides.

Comparisons of Orbitrap Velos and Fusion Lumos Analyses.

Across three cPILOT 12-plex batches and three different instrument analyses methods, >600 000 PSMs (Table 2) corresponding to >22 000 peptides (Supplemental Table S4) and 6074 protein groups (Figure 3) were identified (Supplemental Table S5).

Table 2.

Number of Proteins and PSMs Identified across Different Experimental Data Sets

| SPS-Na | protein groupsb | proteins (%)c | PSMS ID | R (%)d | K (%)e | TMT-K (%)f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orbitrap Velos, SCX | 1 | 2199 | 142 (14) | 374951 | 133 759 (35.7) | 236 177 (63.0) | 234 114 (99.1) |

| Fusion Lumos, No SCX | 10 | 1848 | 334 (26) | 44620 | 17 851 (40.0) | 25 959 (58.2) | 25 498 (98.2) |

| Fusion Lumos, SCX | 10 | 4968 | 1012 (28) | 223286 | 87 840 (39.3) | 129 797 (58.0) | 127 791 (98.0) |

The number of fragment ions used for synchrous precursor selection (SPS).

The number of proteins identified with >1 PSM.

The number and percentage of proteins quantified in all reporter (i.e., 126–131) ion channels across all experimental groups.

The number and percentage of peptides ending with arginine.

The number and percentage of peptides ending with lysine.

The number and percentage of lysine ending peptides labeled with TMT6-plex.

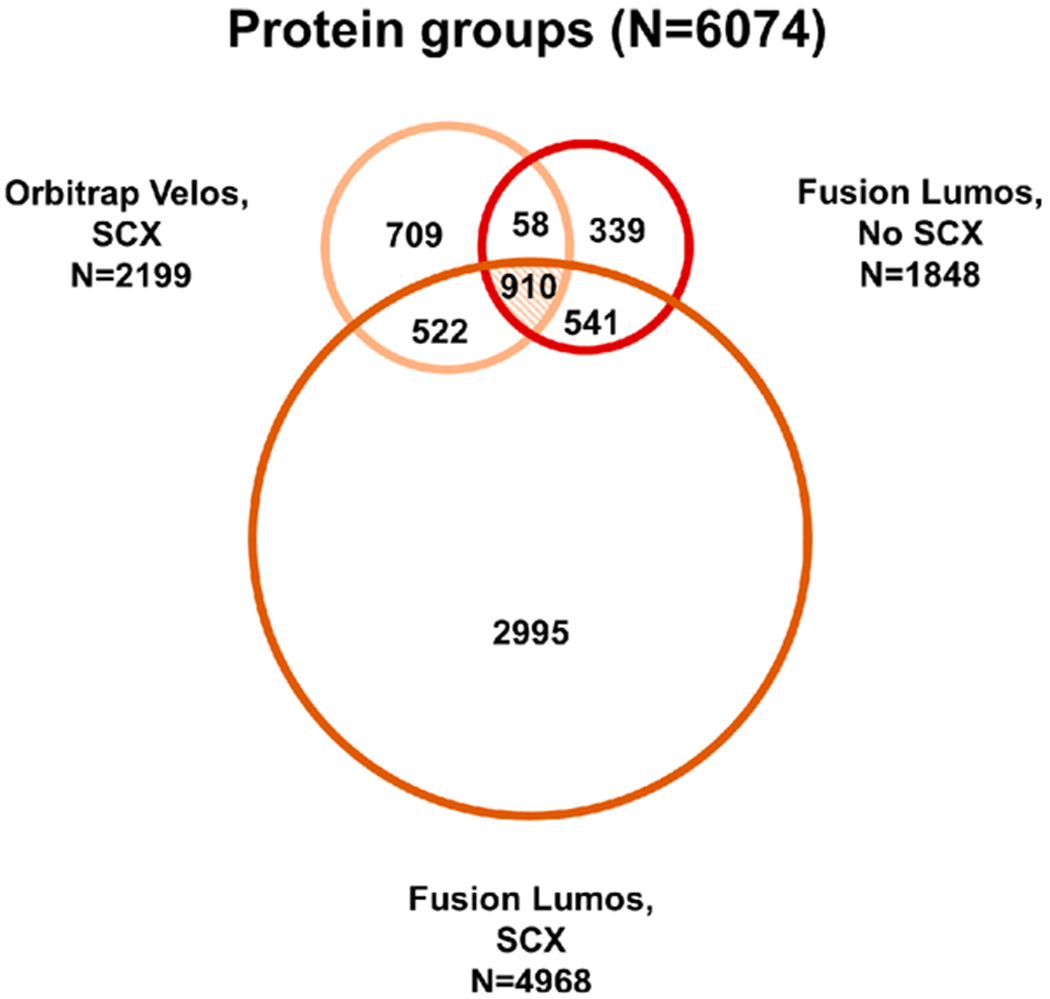

Figure 3.

Protein groups identified across three MS experiments. Proteins identified from SCX fractions acquired on the Velos (N = 2199) were compared to proteins identified from SCX fractions acquired on the Fusion Lumos (N = 4968) and nonfractionated on the Fusion Lumos (N = 1848). Across all three experiments, 6074 proteins were identified, with 910 proteins (~15%) being present in all groups.

Sample fractionation increased the number of peptides and proteins identified on the Orbitrap Velos and Fusion Lumos by ~3×, compared to unfractionated samples on the Fusion Lumos (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table S6). Differences in parameters used for separation (i.e., column length and particle size) and MS acquisition (i.e., Top-N vs Top-Speed DDA) contributed to the differences in peptide populations identified and quantified from the Orbitrap Velos and Fusion Lumos. Overall, 910 protein groups were shared across all analysis methods. Among the 6074 proteins identified, 70% were identified with >2 PSMs (Supplemental Figure S4). The most abundant protein in this experiment was myosin-6 (28 412 PSMs).

Examining AD Pathogenesis from Brain, Heart, and Liver Tissues.

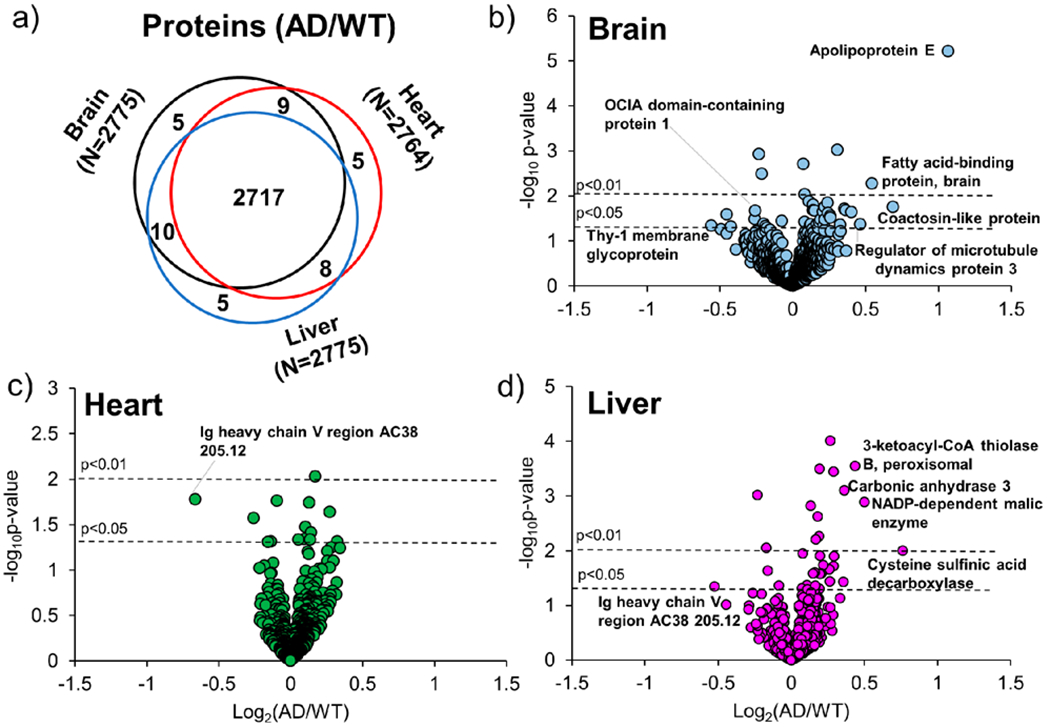

Quantified proteins (Figure 4a and Supplemental Tables S7a–c) in both WT and AD were mostly present in all tissues with intensities ranging between 1 × 104 and 1 × 109 (Supplemental Figure S1b. Few proteins were quantified in either a single or two tissue types; among this group, six proteins (Supplemental Table S8) were expressed at high levels in heart, brain, or liver according to the Bgee database. System-wide changes in AD were evaluated in brain, heart, and liver proteins from WT and AD mice (Figure 4b–d) to determine proteomic changes in the periphery in late-stage AD. A total of 85 (N = 39 brain, N = 14 heart, and N = 32 liver) proteins had significant changes between AD and WT samples (p < 0.05, Supplemental Table S9). Proteins in the brain with highly significant (p < 0.001) changes included apolipoprotein E (p = 6.14 × 10−6) and cathepsin D (p = 9.72 × 10−4). Proteins in the liver included proteolytic protein MCG15081 (p = 9.67 × 10−5), carbonic anhydrase 3 (p = 7.80 × 10−4), A-kinase anchor protein 1, mitochondrial a (p = 3.59 × 10−4), and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase B, peroxisomal (p = 2.80 × 10−4).

Figure 4.

(a) Comparison of quantified proteins and (b–d) volcano plots of brain, heart, and liver tissues in the Fusion Lumos (SCX Fractions) data set. (a) Venn diagram showing proteins quantified (AD/WT) in brain (black), heart (red), or liver (blue) tissues. (b–d) Normalized and filtered proteins were compared using a one-way ANOVA. Proteins from peptides with a p < 0.05 are present above the horizontal line (black) and correspond to (b) brain, (c) heart, or (d) liver tissues.

Canonical pathways identified (Supplemental Figures S5 and S6), including clathrin-mediated endocytosis signaling and unfolded protein response, are known to change in the AD brain.35,36 Differentially expressed proteins apolipoprotein E and clusterin, proteins also implicated in AD brain pathogenesis,37,38 were higher in expression in the brain in AD compared to WT mice in this study. In the liver, mostly metabolic proteins, including aldehyde dehydrogenase, 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase-B, peroxisomal, and NADP-dependent malic enzyme, were higher in AD compared to WT mice (Supplemental Table S9). These proteins are involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and the Krebs cycle and may contribute to dysregulated metabolism in AD.39,40 In the heart, 28S ribosomal protein S5, mitochondrial, and 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 11, which are related to protein synthesis and folding, were higher in AD mice. Immunoglobulin protein, Ig heavy chain V region AC38 205.12, was lower in AD mice in both heart and liver tissues and may be involved in peripheral immune response.41 Proteins related to electron transport and metabolism were mostly at higher levels in the heart and likely contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, a known pathological hallmark of AD. In addition, proteins related to metabolism, protein folding, peptide synthesis, and oxidative stress were higher in the brain and liver of AD mice compared to WT. Other studies using APP/PS-1 mice have shown similar metabolic changes occurring during AD progression, especially in relation to glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, lipid metabolism, and ketogenic metabolism.16,17,42 In those analyses, peripheral tissues, including the thymus, spleen, liver, heart, and kidney were studied.16,17,42 Metabolic changes mostly occurred at 5 or 6 months and were also related to amino-acid, nucleic-acid, cholesterol, phospholipid, or fatty-acid metabolism.17

This study confirms that metabolic changes are more pronounced in this AD mouse model at advanced-disease stages (i.e., 14 months). Interestingly, there was minimal overlap in the number of differentially expressed proteins across tissues (Supplemental Table S9), suggesting the brain and periphery have specific pathogenetic changes in AD. Western analysis of example proteins β-actin and PSMD11 are provided in Supplemental Figure S6.

CONCLUSIONS

cPILOT is an enhanced multiplexing technique that, as demonstrated herein, can provide system-wide information about disease in a single comprehensive proteomics experiment. The most biological information is gained from these experiments when quantitative information is obtained from all samples. This study has provided insight into (1) cPILOT performance on two Orbitrap instruments and (2) changes in the peripheral proteome of AD. Successful cPILOT analysis on the Fusion Lumos relied heavily on changing instrument settings. The Orbitrap Velos or Elite platforms can still be used for cPILOT; however, in all cases, we encourage careful evaluation of experimental parameters prior to data collection. This is critical as the nature of the samples, tagging reagents, sample preparation, chromatography, and instrument type impact quantitative results. Optimization of these parameters greatly helps improve the quality of the data acquired and impacts the proteome depth for this multiplexing analysis. Interestingly, this is the first demonstration using quantitative proteomics to compare brain, heart, and liver tissues from an AD mouse model. An increase of metabolic processes, including lipid, carbohydrate, and peptide metabolism, occurs across peripheral tissues in AD. Future studies that can translate the relevance of these findings to human AD patients and that evaluate early disease stages are warranted.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the University of Pittsburgh and Vanderbilt University Start-up funds and NIH, NIGMS R01 GM117191-01 to R.A.S.R The authors also acknowledge the S-STEM Fellowship (University of Pittsburgh) and a postdoctoral training fellowship T32-AG058524 (Vanderbilt University, Vanderbilt Memory & Alzheimer’s Center) to C.D.K. The authors acknowledge the University of Pittsburgh Division of Animal Resources for assistance with animal husbandry.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Supplemental Table S1. Strategy of cPILOT analysis across tissues. Supplemental Table S2. Effects of targeted analyses tests on the number of PSMs quantified. Supplemental Table S3. Effects of targeted analyses tests on the number of proteins quantified. Supplemental Table S6. Proteins identified and quantified across batches in each experiment. Supplemental Tables S7a–c. Proteins identified and quantified across tissue/disease state. Supplemental Table S8. Proteins quantified in one or two tissue types. Supplemental Table S9. Differentially expressed proteins in the brain, heart, and/or liver as a function of disease. (PDF)Supplemental Table S4. Peptides identified from brain, heart, and/or liver tissues (batches 1–3, combined experiments). Supplemental Table S5. Protein groups identified from brain, heart, and/or liver tissues (batches 1–3, combined experiments). (XLSX)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Christina D. King, Department of Chemistry, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee 37235, United States

Renã A. S. Robinson, Department of Chemistry, Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology, and Vanderbilt Brain Institute, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee 37235, United States; Department of Neurology and Vanderbilt Memory & Alzheimer’s Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee 37232, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Valenti R; Pantoni L; Markus HS BMC Med. 2014, 12 (1), 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).de Bruijn RF; Ikram MA BMC Med. 2014, 12 (1), 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Attems J; Jellinger KA BMC Med. 2014, 12 (1), 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Stampfer MJ J. Intern. Med 2006, 260 (3), 211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Ott A; Stolk RP; van Harskamp F; Pols HAP; Hofman A; Breteler MMB Neurology 1999, 53 (9), 1937–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ohara T; Doi Y; Ninomiya T; Hirakawa Y; Hata J; Iwaki T; Kanba S; Kiyohara Y Neurology 2011, 77 (12), 1126–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Huang C-C; Chung C-M; Leu H-B; Lin L-Y; Chiu C-C; Hsu C-Y; Chiang C-H; Huang P-H; Chen T-J; Lin S-J; Chen J-W; Chan W-L PLoS One 2014, 9 (1), No. e87095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kannel WB Am. J. Hypertens 2000, 13 (1, Supplement 1), S3–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Skoog I; Gustafson D Neurol. Res 2003, 25 (6), 675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Moonga I; Niccolini F; Wilson H; Pagano G; Politis M European Journal of Neurology 2017, 24 (9), 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Gustafson D; Rothenberg E; Blennow K; Steen B; Skoog I Arch. Intern. Med 2003, 163 (13), 1524–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kivipelto M; Ngandu T; Fratiglioni L; Viitanen M; Kareholt I; Winblad B; Helkala E-L; Tuomilehto J; Soininen H; Nissinen A Arch. Neurol 2005, 62 (10), 1556–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Anstey KJ; Ashby-Mitchell K; Peters R J. Alzheimer’s Dis 2017. 56 (1), 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Savonenko A; Xu GM; Melnikova T; Morton JL; Gonzales V; Wong MPF; Price DL; Tang F; Markowska AL; Borchelt DR Neurobiol. Dis 2005, 18 (3), 602–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Evans AR; Gu L; Guerrero R; Robinson RAS Proteomics: Clin. Appl 2015, 9 (9–10), 872–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Gonzalez-Dominguez R; Garcia-Barrera T; Vitorica J; Gomez-Ariza JL Electrophoresis 2015, 36 (18), 2237–2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zheng H; Cai A; Shu Q; Niu Y; Xu P; Li C; Lin L; Gao H J. Proteome Res 2019, 18 (3), 1218–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Robinson RAS; Evans AR Anal. Chem 2012, 84 (11), 4677–4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Gu L; Evans AR; Robinson RAS J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2015, 26 (4), 615–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gu L; Robinson RAS Analyst 2016, 141 (12), 3904–3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Merrill AE; Hebert AS; MacGilvray ME; Rose CM; Bailey DJ; Bradley JC; Wood WW; El Masri M; Westphall MS; Gasch AP; Coon JJ Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13 (9), 2503–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Dephoure N; Gygi SP Sci. Signaling 2012, 5 (217), No. rs2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Frost DC; Rust CJ; Robinson RAS; Li L Anal. Chem 2017, 90 (18), 10664–10669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Everley RA; Kunz RC; McAllister FE; Gygi SP Anal. Chem 2013, 85 (11), 5340–5346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Arul AB; Robinson RAS Anal. Chem 2019, 91 (1), 178–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ting L; Rad R; Gygi SP; Haas W Nat. Methods 2011, 8 (11), 937–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Evans AR; Robinson RAS Proteomics 2013, 13 (22), 3267–3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Senko MW; Remes PM; Canterbury JD; Mathur R; Song Q; Eliuk SM; Mullen C; Earley L; Hardman M; Blethrow JD; Bui H; Specht A; Lange O; Denisov E; Makarov A; Horning S; Zabrouskov V Anal. Chem 2013, 85 (24), 11710–11714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Eliuk S; Makarov A Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem 2015, 8 (1), 61–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).McAlister GC; Nusinow DP; Jedrychowski MP; Wuhr M ; Huttlin EL; Erickson BK; Rad R; Haas W; Gygi SP Anal. Chem 2014, 86 (14), 7150–7158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).King CD; Dudenhoeffer JD; Gu L; Evans AR; Robinson RAS J. Visualized Exp 2017, No. 123, e55406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Plubell DL; Wilmarth PA; Zhao Y; Fenton AM; Minnier J; Reddy AP; Klimek J; Yang X; David LL; Pamir N Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2017, 16 (5), 873–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Pascovici D; Handler DC; Wu JX; Haynes PA Proteomics 2016, 16 (18), 2448–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Wang W; Sue AC; Goh WWB Drug Discovery Today 2017, 22 (6), 912–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Koss DJ; Platt B Behav. Pharmacol 2017, 28, 161–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Nakaya T; Yamamoto T; Suzuki T; Araki Y J. Biochem 2006, 139 (6), 949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Mahley RW J. Mol. Med 2016, 94 (7), 739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Poirier J; Bertrand P; Poirier J; Kogan S; Gauthier S; Poirier J; Gauthier S; Davignon J; Bouthillier D; Davignon J Lancet 1993, 342 (8873), 697–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Kamino K; Nagasaka K; Imagawa M; Yamamoto H; Yoneda H; Ueki A; Kitamura S; Namekata K; Miki T; Ohta S Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2000, 273 (1), 192–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Grünblatt E; Riederer P Journal of Neural Transmission 2016, 123 (2), 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Taguchi H; Planque S; Sapparapu G; Boivin S; Hara M; Nishiyama Y; Paul S J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283 (52), 36724–36733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Gonzalez-Dominguez R; Garcia-Barrera T; Vitorica J; Gomez-Ariza JL Electrophoresis 2015, 36 (4), 577–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.