Abstract

Background

Cardiac involvement in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is known, manifested by troponin elevation. Studies in the initial phase of the pandemic demonstrated that these patients tended to have a worse prognosis than patients without myocardial injury. We sought to evaluate the clinical impact of significant troponin elevation in COVID-19-positive patients, along with predictors of poor outcomes, over the span of the pandemic to date.

Methods

We analyzed COVID-19-positive patients who presented to the MedStar Health system (11 hospitals in Washington, DC, and Maryland) during the pandemic (March 1–June 30, 2020). We compared clinical course and outcomes based on the presence of troponin elevation and identified predictors of mortality.

Results

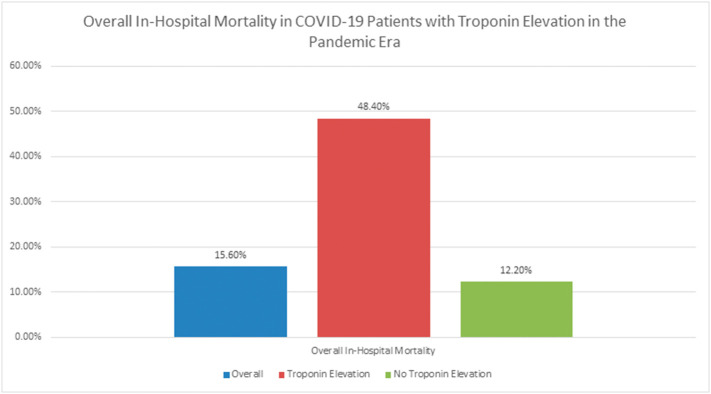

The cohort included 2716 COVID-19-positive admitted patients for whom troponin was drawn. Of these patients, 250 had troponin elevation (≥1.0 ng/mL). In the troponin-elevation arm, the minimum troponin level was 1.9 ± 8.82 ng/mL; maximum elevation was 10.23 ± 31.07 ng/mL. The cohort's mean age was 68.0 ± 15.0 years; 52.8% were men. Most (68.5%) COVID-19-positive patients with troponin elevation were African American. Patients with troponin elevation tended to be older, with more co-morbidities, and most required mechanical ventilation. In-hospital mortality was significantly higher (48.4%) in COVID-19-positive patients with concomitant troponin elevation than without troponin elevation (12.2%; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

COVID-19 patients with troponin elevation are at higher risk for mechanical ventilation and mortality. Efforts should focus on early recognition, evaluation, and intensifying care of these patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, Myocardial injury, Troponin elevation, Acute coronary syndrome

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and was first identified in Wuhan, China [1]. Patients infected with the virus develop cardiac damage due to multiple different mechanisms. The virus can directly injure myocardial cells, induce a cytokine surge, or result in myocardial oxygen supply/demand mismatch as part of the systemic inflammatory response to the virus [2]. Furthermore, this systemic inflammatory response can result in increased plaque vulnerability and precipitate plaque rupture, resulting in acute coronary syndrome [3].

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted healthcare systems throughout the world. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends deferral of elective procedures, including coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for stable coronary disease [4], to maximize hospital capacity for COVID-19 patients. Despite these recommendations, the American guidelines reinforce primary PCI as the standard of care for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients during the pandemic at PCI-capable centers [5,6]. Furthermore, the guidelines recommend treatment of non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) in patients with high-risk features and a low probability (or negative test) for COVID-19. Cardiac involvement in COVID-19 patients is common, as evidenced by troponin and natriuretic peptide elevation. Studies during the initial part of the pandemic indicate that about 30% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 have an elevated troponin, and these patients have a worse prognosis than patients without myocardial injury [[7], [8], [9]].

We sought to describe our healthcare system's experience of COVID-19 during the pandemic and the clinical impact of troponin elevation. We wanted to determine whether the overall peak troponin results in a worst prognosis for these patients. We also sought to identify predictors of mortality.

2. Methods

We analyzed COVID-19-positive patients who presented to the MedStar Health system (11 hospitals in Washington, DC, and Maryland) during the pandemic era. The “pandemic era” (our study time period) was identified as March 1, 2020, through June 30, 2020, as this was the period when US social life and medical procedures within our region were most significantly affected by COVID-19. The positive test for the infection was based on polymerase chain reaction testing.

The troponin-I value recorded is the peak value during the hospitalization. Investigators defined significant presence of troponin as an elevation over 1 ng/mL. Baseline characteristics (age, sex, gender, race) and co-morbidities (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hemodialysis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and history of pulmonary embolism) were collected. The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality. The secondary endpoints include intensive care unit (ICU) admission, ICU length of stay, and use of ventilation. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by our institutional review board.

2.1. Statistical methods

Categorical variables were presented in terms of sample frequencies and proportions and continuous variables in terms of sample means and standard deviations. To compare the baseline characteristics and endpoints between the troponin-elevation and non-troponin-elevation groups, Student's t-test was used for continuous variables and χ 2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Half of the cohort was randomly selected for model selection. Stepwise selection was applied to choose among a pool of covariates including troponin elevation as a binary variable, age, African American ethnicity, admission to ICU, need for mechanical ventilation, NSTEMI, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular accident, chronic heart failure, and atrial fibrillation, to enter or drop in the model with the significance level for entry being 0.1 and the significance level to stay being 0.05. The selected model was chosen to yield the minimum AIC statistic. All analysis was conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

3. Results

In our medical system, 2716 COVID-19-positive admitted patients from March 1, 2020, through June 30, 2020, had troponin drawn. Of these patients, 250 had troponin elevation (9.2%). Baseline characteristics can be found in Table 1 . The majority of patients were men (51.5%), with a mean age of 62.0 ± 16.4 years. Patients with troponin elevation tended to be older than those without. There was evidence of racial disparity in our analysis. The majority of COVID-19-positive patients with troponin elevation were African American (61.8%). Co-morbidities, including hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hemodialysis, asthma, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, and atrial fibrillation, were more frequently seen in patients with COVID-19 and concomitant troponin elevation. In the troponin-elevation arm, the minimum troponin was 1.9 ± 8.82 ng/mL, and the maximum elevation was 10.23 ± 31.07 ng/mL (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

Baseline characteristics of all COVID-19-positive patients during the pandemic era overall and based on troponin elevation.

| Overall n = 2716 |

Troponin elevation % n = 250 |

No troponin elevation % n = 2646 |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) ± SD | 62.0 ± 16.4 | 68.0 ± 15.0 | 61.4 ± 16.4 | <0.001 |

| Male | 51.5% | 52.8% | 51.3% | 0.660 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 14.8% | 18.5% | 14.4% | 0.078 |

| African American | 61.8% | 68.5% | 61.1% | 0.021 |

| Asian | 1.1% | 0.4% | 1.1% | 0.291 |

| Native American | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.537 |

| Other | 22.1% | 12.2% | 23.2% | <0.001 |

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 49.5% | 48.8% | 49.6% | 0.820 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 38.8% | 52.4% | 37.4% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 43.1% | 54.0% | 42.0% | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 24.6% | 43.6% | 22.7% | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 8.1% | 18.0% | 7.1% | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 9.4% | 10.8% | 9.2% | 0.409 |

| Asthma | 9.3% | 4.0% | 9.8% | 0.003 |

| Coronary artery disease | 13.0% | 26.4% | 11.7% | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 9.3% | 18.4% | 8.4% | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 15.7% | 33.2% | 13.9% | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 9.5% | 17.6% | 8.7% | <0.001 |

| Prior pulmonary embolism | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.652 |

Table 2.

Laboratory values.

Laboratory values and intensive care unit admission of COVID-19-positive patients during the pandemic era overall and based on troponin elevation.

| Overall n = 2716 |

Troponin elevation n = 250 |

No troponin elevation n = 2646 |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Troponin max (ng/mL) | 0.94 ± 9.86 | 10.23 ± 31.07 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Troponin min (ng/mL) | 0.18 ± 2.73 | 1.9 ± 8.82 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 36.2% | 74.0% | 32.4% | <0.001 |

| Ventilator requirement | 22.9% | 58.0% | 19.3% | <0.001 |

| Length of stay in intensive care unit (days) | 9.82 ± 10.83 | 9.02 ± 10.03 | 10.01 ± 11.00 | 0.267 |

With regard to our primary endpoint, in-hospital mortality was significantly higher (48.4%) in COVID-19-positive patients with concomitant troponin elevation than in COVID-19-positive patients without troponin elevation (12.2%; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1 and Table 3 ). Secondary analysis of the COVID-19-positive patients with troponin elevation demonstrated that a majority of patients were admitted to the ICU, and over half required mechanical ventilation. Finally, the average length of stay in the ICU was 9.02 ± 10.03 days.

Fig. 1.

Overall in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients with troponin elevation in the pandemic era.

Table 3.

Overall in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients based on the presence of troponin elevation.

| Overall |

Troponin elevation % |

No troponin elevation % |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2716 | n = 250 | n = 2646 | ||

| Overall in-hospital mortality | 15.6% | 48.4% | 12.2% | <0.001 |

Stepwise selection yielded a logistic prediction model with troponin elevation, age, admission to ICU, on ventilation, NSTEMI, and CKD as covariates. The odds-ratio estimates and their 95% confidence intervals are summarized in Table 4 . All variables appeared to be significant except for NSTEMI. Among the binary predictors, admission to ICU, need for mechanical ventilation, and troponin elevation had the most impact on mortality.

Table 4.

Predictors of in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Troponin elevation | 2.88 | 1.73–4.82 |

| Age | 1.05 | 1.03–1.06 |

| ICU admission | 2.83 | 1.64–4.89 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 8.70 | 5.18–14.61 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.89 | 1.27–2.83 |

| Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 0.50 | 0.16–1.54 |

4. Discussion

The primary findings of our analysis suggest that COVID-19-positive patients with concomitant troponin elevation have a significantly increased risk of mortality as compared to COVID-19-positive patients without troponin elevation. There are racial and age disparities, as patients with troponin elevation tend to be African American and older, with multiple co-morbidities. Additionally, two-thirds of COVID-19-positive patients with troponin elevation are admitted to the ICU, and more than half of these patients require mechanical ventilation.

Underlying co-morbidities, including hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hemodialysis, asthma, known coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, and atrial fibrillation, were more frequently seen in COVID-19-positive patients with troponin elevation. These findings reinforce previous studies that demonstrated an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the presence of pre-existing co-morbidities [10,11]. Furthermore, our center demonstrated a racial disparity. White COVID-19-positive patients were less likely to have troponin elevation than African American COVID-19-positive patients. This racial disparity finding is consistent with previous studies [12,13].

It is known that patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 have elevated inflammatory markers (white blood cell count, ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase, C-reactive protein, etc.) [14]. Our analysis demonstrates that troponin should be checked along with the above laboratory data, irrespective of classic cardiac symptoms. If a provider is concerned about a COVID-19-positive patient, it is imperative that inflammatory markers, including troponin, be checked, as this can be an indication of both infection and overall severity of the illness with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality [15]. The increased rate of in-hospital mortality for patients who have troponin elevation likely reflects that these patients tend to be older, with more co-morbidities. In addition, these patients tend to be admitted to the ICU more frequently and require intubation.

The severe form of COVID-19 occurs in about 15% of patients requiring hospitalization, with 5% of patients requiring intensive care. The current mortality rate is estimated to be between 2% and 5% of all patients with COVID-19. The major cause of death in COVID-19 is acute respiratory distress [16]. However, other organ involvement is common, including cardiac involvement [17]. Previous studies have demonstrated that having cardiac co-morbidities places a patient at increased risk of developing the disease and, furthermore, the severe form [14]. In addition, our analysis demonstrates that cardiovascular involvement greatly increases a patient's likelihood of death. Patients who develop acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during COVID-19 have a much higher mortality risk than COVID-19 patients who do not develop AMI. Healthcare providers need to be aware of the deadly combination of COVID-19 and AMI.

Another interesting finding to note in our study is that approximately 90% of the patients who had troponin drawn during the study period did not have troponin elevation. This rate differs from prior publications in the initial stages of the pandemic, in which about 70% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 had elevated troponin. Despite changes in the actual rate, in both our study and prior ones, COVID-19 patients with troponin elevation were found to have a worse prognosis than patients without myocardial injury. The difference between our findings and earlier studies in the initial phases of the pandemic is unclear. It is possible that patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 were identified earlier in our study, as compared to findings earlier in the pandemic, and are seeking treatment sooner. One could also argue that clinical knowledge of the virus, along with treatment and management options, has improved as compared to when earlier studies were conducted in the initial phases of the pandemic. However, direct causality cannot be confirmed from our analysis.

Finally, in many patients with acute coronary syndrome and COVID-19, coronary angiography is deferred because of concerns of spreading the infection to other patients or hospital staff. In addition, the deferral of an invasive treatment strategy for these STEMI and NSTEMI patients reflects a sicker cohort, with more co-morbidities and a higher percentage in the ICU. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that up to 60% of STEMI patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection had true culprit-lesion-vessel disease, while the others had STEMI as their initial presentation but were found to have a mimicking disease, such as myocarditis or stress-induced cardiomyopathy [18]. The impact of primary PCI on time to reperfusion and outcomes during the pandemic remains to be determined. Every effort needs to be made to make an early diagnosis and begin treatment to prevent potential complications in acute coronary syndrome patients. Guidelines of primary PCI for STEMI and NSTEMI need to be followed, even during a pandemic, to help treat these critically ill patients.

4.1. Limitations

There are limitations to our study. First, the analysis is retrospective and relies on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes to identify the patient population. Our analysis does not distinguish between Type I and Type II NSTEMI. In addition, we did not capture patients who underwent coronary angiography or subsequent PCI, which would have allowed us to identify those patients who had a true plaque rupture as the etiology of their AMI versus another etiology, such as myocarditis or stress-induced cardiomyopathy [19]. We also did not capture how these patients were treated (pharmacology, mechanical support, etc.). Finally, our data captured patients in the Mid-Atlantic region of the US, where the pandemic was most impactful in March and April 2020. Our findings may not represent the broader US.

5. Conclusions

Patients with COVID-19 and troponin elevation tended to be older, with more co-morbidities, as compared to patients with COVID-19 without troponin elevation. This led to a substantially higher rate of in-hospital mortality in this cohort. Efforts should be focused on early recognition, evaluation, and treatment of patients with both COVID-19 and troponin elevation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Toby Rogers – Proctor and Consultant: Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences; Advisory Board: Medtronic; Equity interest: Transmural Systems.

Ron Waksman – Advisory Board: Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Boston Scientific, Cardioset, Cardiovascular Systems Inc., Medtronic, Philips, Pi-Cardia Ltd.; Consultant: Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardioset, Cardiovascular Systems Inc., Medtronic, Philips, Pi-Cardia Ltd., Transmural Systems; Grant Support: AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Chiesi; Speakers Bureau: AstraZeneca, Chiesi; Investor: MedAlliance; Transmural Systems.

All other authors – None.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

Special acknowledgment to Jason Wermers for assistance in preparing this report.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;23:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong T.Y., Redwood S., Prendergast B., Chen M. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1798–1800. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoenhagen P., Tuzcu E.M., Ellis S.G. Plaque vulnerability, plaque rupture, and acute coronary syndromes: (multi)-focal manifestation of a systemic disease process. Circulation. 2002;106:760–762. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025708.36290.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia S., Albaghdadi M.S., Meraj P.M., Schmidt C., Garberich R., Jaffer F.A., et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2871–2872. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Gara P.T., Kushner F.G., Ascheim D.D., Casey D.E., Jr., Chung M.K., de Lemos J.A., et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82:E1–27. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welt F.G.P., Shah P.B., Aronow H.D., Bortnick A.E., Henry T.D., Sherwood M.W., et al. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: from the ACC’s Interventional Council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2372–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo T., Fan Y., Chen M., Wu X., Zhang L., He T., et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:811–818. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruan Q., Yang K., Wang W., Jiang L., Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:846–848. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi S., Qin M., Shen B., Cai Y., Liu T., Yang F., et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao M., Zhang D., Wang Y., Lu Y., Zhu X., Li Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in Shanghai, China. medRxiv. Mar 6 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.04.20030395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldstein L.R., Rose E.B., Horwitz S.M., Collins J.P., Newhams M.M., Son M.B.F., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnan L., Ogunwole S.M., Cooper L.A. Historical insights on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the 1918 influenza pandemic, and racial disparities: illuminating a path forward. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:474–481. doi: 10.7326/M20-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wadhera R.K., Wadhera P., Gaba P., Figueroa J.F., Joynt Maddox K.E., Yeh R.W., et al. Variation in COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths across New York City boroughs. JAMA. 2020;323:2192–2195. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng F., Huang Y., Guo Y., Yin M., Chen X., Xiao L., et al. Association of inflammatory markers with the severity of COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velavan T.P., Meyer C.G. Mild versus severe COVID-19: laboratory markers. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:304–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., Zhang J., Huang L., Zhang C., et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng Y.Y., Ma Y.T., Zhang J.Y., Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stefanini G.G., Montorfano M., Trabattoni D., Andreini D., Ferrante G., Ancona M., et al. ST-elevation myocardial infarction in patients with COVID-19: clinical and angiographic outcomes. Circulation. 2020;141:2113–2116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalid N., Chen Y., Case B.C., Shlofmitz E., Wermers J.P., Rogers T., et al. COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) and the heart - an ominous association. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:946–949. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]