Abstract

Mental health disorders in children and adolescents are highly prevalent yet undertreated. A detailed understanding of the reasons for not seeking or accessing help as perceived by young people is crucial to address this gap. We conducted a systematic review (PROSPERO 42018088591) of quantitative and qualitative studies reporting barriers and facilitators to children and adolescents seeking and accessing professional help for mental health problems. We identified 53 eligible studies; 22 provided quantitative data, 30 provided qualitative data, and one provided both. Four main barrier/facilitator themes were identified. Almost all studies (96%) reported barriers related to young people’s individual factors, such as limited mental health knowledge and broader perceptions of help-seeking. The second most commonly (92%) reported theme related to social factors, for example, perceived social stigma and embarrassment. The third theme captured young people’s perceptions of the therapeutic relationship with professionals (68%) including perceived confidentiality and the ability to trust an unknown person. The fourth theme related to systemic and structural barriers and facilitators (58%), such as financial costs associated with mental health services, logistical barriers, and the availability of professional help. The findings highlight the complex array of internal and external factors that determine whether young people seek and access help for mental health difficulties. In addition to making effective support more available, targeted evidence-based interventions are required to reduce perceived public stigma and improve young people’s knowledge of mental health problems and available support, including what to expect from professionals and services.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00787-019-01469-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Children, Adolescents, Mental health, Barriers, Facilitators, Professional help

Introduction

Almost one in seven young people meet diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder [1]. Untreated mental health disorders in children and adolescents are related to adverse health, academic and social outcomes, higher levels of drug abuse, self-harm and suicidal behaviour [2–4] and often persist into adulthood [5]. Indeed, half of the lifetime mental health problems start by the age of 15 and nearly three quarters by the age of 18 [6], creating a substantial global socioeconomic burden [7]. These short and longer term negative outcomes associated with youth mental health problems emphasise the importance of early detection and prompt access to professional treatment.

Effective, evidence-based treatments for mental health disorders in young people exist [8]. However, less than two-thirds of young people with mental health problems and their families access any professional help [9]. In general, young people are more likely to get professional help if they are older (i.e. adolescents more likely than children), Caucasian, experiencing more than one mental health problem and suffering from behavioural rather than emotional disorders [10, 11]. Besides from factors associated with treatment utilisation (e.g. gender and race), a detailed understanding of the reasons that young people (rather than parents or professionals) do not seek and access professional help is crucial to address the gap between the high prevalence of mental health disorders in young people and low treatment utilisation. A recent systematic review of parent-reported barriers to accessing professional help for their child’s mental health problems identified barriers related to systemic/structural obstacles (e.g. costs, waiting times), attitudes towards the service providers and psychological treatment (e.g. trust and confidence in professionals, the perceived effectiveness of treatment), knowledge and understanding of mental health problems and the help-seeking process (e.g. recognition of the problem, knowing where to get help) and family circumstances (e.g. other responsibilities and family’s support network) [12]. Amongst general practitioners (GPs), who often act as ‘gatekeepers’ between families and specialist services, commonly perceived barriers include difficulties identifying and managing mental health problems (e.g. confidence, time, lack of specific mental health knowledge) and making successful referrals for treatment (e.g. lack of providers and resources) [13].

As young people can take an active role in help-seeking, particularly as they get older, it is important to ascertain their own views on the barriers to seeking and accessing help for their mental health problems. A previous systematic review that focused on young people’s views found that young people most commonly fail to seek help because of stigma, embarrassment, difficulties with recognising problems and a desire to deal with difficulties themselves [14]. However, this review only considered help-seeking for anxiety, depression and general ‘mental distress’ and, therefore, does not capture barriers in the context of other mental health disorders, or more recent literature published since 2009. Furthermore, the review included samples of young adults (e.g. university students), making it hard to know the degree to which the reported barriers/facilitators are relevant for children and adolescents specifically.

It is now widely recognised that high demands on specialist services, limited available provision and long waiting lists present key barriers to accessing child and adolescent mental services [15]. This has prompted a range of recent initiatives designed to increase the availability and accessibility of specialist services (e.g. Children and Young People’s Improving Access to Psychological Treatment (CYP-IAPT) Programme in the UK, KidsMatter in Australia), support within schools [16, 17], and public resources (e.g. YoungMinds, ReachOut). However, it is critical that efforts to improve access to support and services consider young people’s views on help-seeking, and by doing so address the barriers that are pertinent to them.

This study provides an up-to-date systematic review of all studies where children and adolescents were asked about barriers and facilitators to help-seeking and accessing professional support in relation to a wide range of mental health difficulties, to inform ongoing and future interventions designed to improve treatment access. To fully address the complexity of the process of seeking and accessing professional help in young people, results from quantitative and qualitative studies were analysed and combined. By focusing on children and adolescents with a mean age of 18 years or younger (and excluding any studies which only included young adults over 21 years) findings will be especially relevant to the school context, and youth services for under 19s.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines [18] and was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO), number 42018088591, on 13/02/2018. A PRISMA checklist is provided in Online Resource 1.

Literature search

The initial search strategy and preliminary inclusion/exclusion criteria followed a recent review of parent-perceived barriers and facilitators to help-seeking and accessing treatment for their children [12]. The search terms captured four major concepts: (1) barriers/facilitators, (2) help-seeking/accessing, (3) mental health, and (4) children/adolescents and parents (see Online Resource 2 for details of the search strategy). The original search was launched in October 2014 [12] and replicated using the same strategy in October 2016 and in February 2018. We used the NHS Evidence Healthcare database, combining Medline, PsycINFO and Embase, and the Web of Science Core Collection separately. Additionally, we used hand-search methods to check the reference list of articles included in the full text screening stage, and performed backward and forward reference searching of key papers to identify further studies of interest.

Eligibility criteria

A study was included if child and/or adolescent (mean sample age up to 18) participants reported barriers and/or facilitators to seeking and accessing professional help for mental health problems. Studies reporting only parental/caregiver’s perceived barriers and facilitators, and studies including only young adults (e.g. university students) were excluded. Similarly, studies that only reported factors associated with treatment utilisation and studies reporting barriers/facilitators related to ongoing treatment engagement (not initial access to treatment) were excluded. The full list of inclusion/exclusion criteria is available in Online Resource 3.

Study selection

We selected the studies for the current review through an initial search in October 2014 conducted within the Reardon et al. [12] review, and two updated searches using the same search terms (October 2014–October 2016; and October 2016–February 2018). In total, 3682 studies published since October 2014 were identified from database searches and hand searching. After duplicates were removed, two independent reviewers from the team (JR, CT, GEB, and PL) screened 2582 abstracts, and 385 full texts. In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted (TR) to reach a final decision. In total, 53 studies were included in the current review. Thirty studies provided qualitative data, 22 provided quantitative data and one study provided both. For two included studies, relevant results were reported in two separate papers, which were all included in a current review [19–22].

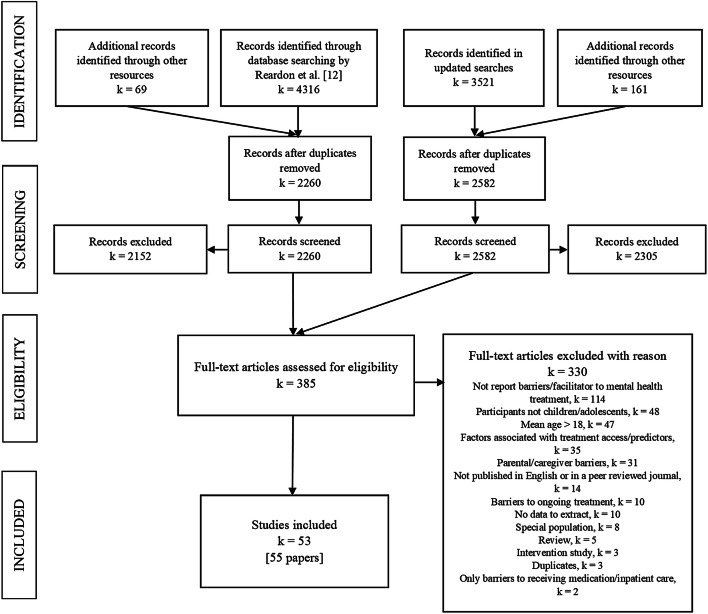

The full process of study selection is presented in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study selection process

Data extraction

We used the data extraction form developed by Reardon et al. [12], with minor amendments to reflect the fact that study participants were children/adolescents rather than parents. The form included the following information: (1) methodology used (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods), (2) country of study, (3) study setting (e.g. school, mental health clinic), (4) child/adolescent characteristics, including age range, gender, ethnicity, area of living (e.g. rural, urban), (5) type of mental health problem addressed/focus of the study and method of mental health assessment, (6) characteristics related to service use, and (7) key findings relating to perceived barriers and facilitators, supported by quantitative or qualitative evidence. Where applicable, details regarding barrier/facilitator measures were recorded for quantitative studies. For qualitative studies, we recorded details about the methods used (e.g. focus groups, interviews) and the areas of relevant questioning. Data extraction was undertaken by two independent reviewers (JR and GEB/PL/TR).

Quality rating

In line with the approach used by Reardon et al. [12], we used two adapted versions of quality rating checklists developed by Kmet et al. [23]. One checklist was used to evaluate the quality of quantitative studies and another to evaluate the quality of qualitative studies. Quality checklists addressed the research question, study design, sampling strategy and data analysis. The quantitative checklist also addressed the robustness of the barrier/facilitator measure, and the qualitative checklist addressed the credibility of the study’s conclusions (see Online Resource 4). The quality of the study that provided qualitative and quantitative data [24] was assessed using both scales. Two independent reviewers (JR and GEB/PL/TR) assessed the quality of each included study. Based on the total score, each study was classified as ‘low’ (0–12 for quantitative and 0–11 for qualitative studies), ‘moderate’ (13–16 for quantitative and 12–15 for qualitative studies) or ‘high’ (17–20 for quantitative and 16–18 for qualitative studies) quality. Discrepancies between the reviewers were discussed with a third reviewer (TR/CC). Each study was included in the review, regardless of its quality.

Data synthesis

We conducted a narrative synthesis following ESRC guidance [25], which outlines three main steps of analysis: (1) developing a preliminary synthesis, (2) exploring relationships between and within studies, and (3) assessing robustness of the synthesis. We chose this approach because of the high methodological variability across studies and the predominantly descriptive nature of the results. Consequently, statistical meta-analysis was not feasible.

A preliminary synthesis was done separately for quantitative and qualitative studies Each individual perceived barrier or facilitator reported in each quantitative study was assigned a code, and we reorganised the data according to these initial codes (e.g. ‘assured confidentiality’, ‘concerns around confidentiality’, ‘worrying that information about me will be shared with others’). We then used an iterative process to refine codes, to group codes into families of codes (e.g. ‘perceived confidentiality’), and finally to group families of codes into overarching barrier/facilitator themes (e.g. ‘relationship factors’). Extracted qualitative data were coded and organised following the same procedure. Next, we developed a single-coding framework capturing barriers and facilitators across quantitative and qualitative studies. Codes generated in the preliminary synthesis of qualitative and quantitative studies were combined and refined in this step, and organised into 22 subthemes and 4 themes. To address the heterogeneity of the quantitative studies and to facilitate comparison across studies, we ‘transformed’ the data [25]. In line with the ESRC guidance, we developed a ‘common rubric’ to summarise the quantitative data. After examining the percentages of participants who endorsed each specific barrier/facilitator across studies, we categorised each barrier/facilitator into one of three groups [‘low’ (endorsed by 0–10% of participants), ‘medium’ (endorsed by 10–30% of participants) and ‘high’ (endorsed by more than 30% of participants)]. These groups reflect the relative distribution of the percentage of respondents who endorsed each barrier/facilitator across studies. Where applicable, Likert-scale responses were converted into ‘percentage endorsed’ by summing positive responses (e.g. ‘agree’ and/or ‘strongly agree’) before categorisation. Three studies reported only means and standard deviations for each barrier/facilitator and no frequencies. In these cases, we applied data standardisation and categorised responses into the three corresponding categories using percentile and z scores. To minimise the impact of barriers/facilitators reported by only a small minority (< 10%) of participants, barriers/facilitators categorised as ‘low’ frequency were not included in subsequent analyses. As results from qualitative studies were descriptive (non-numerical), this kind of data transformation was not appropriate for qualitative studies.

We used graphical methods to present the percentage of included studies that reported each specific barrier/facilitator, and the corresponding percentage for qualitative and quantitative studies separately. Next, we explored the relationship between study characteristics (e.g. qualitative/quantitative methodology, country, use of a mental health assessment to identify participants) and sample characteristics (e.g. mental health status, gender, area of living), and barrier/facilitator themes and subthemes. Where we identified a pattern related to study/sample characteristics, details are reported below.

We performed a sensitivity analysis to establish the review’s robustness by examining the impact of ‘low’ quality studies on the findings. These studies were removed and results related to themes, subthemes and conclusions re-examined to determine whether they stayed the same or not.

All analyses were led by the primary author (JR), with regular discussions with other reviewers (TR/PW/CC) to agree with the interpretation of codes and themes.

Results

Study description

In total, 53 studies were included in the review, with 22 providing quantitative data, 30 providing qualitative data, and 1 study providing both [24]. Therefore, the total number of studies and corresponding percentages in the results refer to 54 included samples (23 quantitative and 31 qualitative). Study characteristics are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of quantitative studies

| References | Number of participants reporting barriers/facilitators | Age (range) | Country | Ethnicity | Females (%) | Area of living | Setting | Focus of the study | Mental health assessment | Source of professional help | Service use | Barrier/facilitator measure—details | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyd et al. [26] | 201 | 11–18 | Australia | No information | 63% | Rural | School | Anxiety and Depression |

CES-D SASa |

Any professional help | No information | Open-ended question about barriers to seeking professional help | 17 (high) |

| Chandra and Minkovitz [32] | 274 | 13–14 | USA | 46% white, 27.4% black, 9.5% Asian, 4.7% Hispanic and 9% multiracial | 50% | Suburban | School | Emotional concerns | Not assessed | Mental health services | 15.9% received psychological services or counselling (past year) | Ten barriers to help-seeking and ‘no barriers’ option | 17 (high) |

| Cigularov et al. [33] | 854 | 14–18 | USA | 78.3% Caucasian, 10.2% Hispanic, 2% Asian/Pacific, 1.7% Native American, 0.8% African American, 6.6% Other | 47% | No information | School | Depression and suicidality | Not assessed | Any professional help | No information | 26 barriers to help-seeking; 6-point Likert scale | 18 (high) |

| D’Amico et al. [29] | 2883 | 14–18 | USA | 69% Caucasian, 13% Hispanic, 5% Asian American/Pacific Islander, 2% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 1% African American, 10% ‘other’ | 50% | No information | School | Alcohol related problems and concerns | Adapted questionnaire to assess drinking habits (6.7% ‘heavy drinkers’ and 21% ‘problem drinkers’) | Alcohol related services | No information | 14 facilitative factors; 5-point Likert scale | 16 (moderate) |

| Freedenthal and Stiffman [27] | 101 (out of 356 screened for suicidal thoughts)b | 15–21 | USA | American Indians | 72% | 51.5% lived on the reservation, 48.5% in urban areas | Participant home | Suicidality | Questions about suicidality (100% ever thought of/attempted suicide; 59.4% suicidal thoughts, 24% multiple suicide attempts, 10% one suicide attempt, 6% number of attempts not given), YSR | Any professional help | 40.59% saw a MH professional; 12.87% consulted a school counsellor or teacher. | Open-ended question about barriers to seeking professional help with suicidal thoughts or behaviour. | 17 (high) |

| Gould et al. [34] | 519 | 13–19 | USA | 78% white, 3% African American, 13% Hispanic, 1% Asian, 4% other | 50% | Urban and rural | School | Feeling very upset, stressed or angry | BHS (10% above threshold) CIS (28% above threshold) | Any professional help including hotlines |

Hotline/substance programme/other health professional: 1.7–3.1 (last year), 2.1–3.3 (ever): School counsellor/ MH professional: 21.1–22-3(last year), 29.5–29.8 (ever) |

16 barriers to help-seeking | 17 (high) |

| Gould et al. [35] | 24 (out of 317 identified ‘at risk’ and who did not seek help after referral at baseline)b | 13–19 | USA | 58.3% white, 20.8% Hispanic, 12.5% Asian, 8.3% other | 54% | No information | School | Suicidality | SIQ-JR (33% serious suicidal ideation), seven questions about suicide attempt history (25% past suicidal attempts), BDI-IA (58.3% depression), DUSI, CIS (37.5%)c | Mental health services | None | HUQ | 17 (high) |

| Guo et al. [36] | 865 Latin American | M = 12.6, SD = 1.96 | USA | Latin American | 51% | No information | School | Internalising and externalising problems | SDQ (20.3% elevated symptoms) and CIS | SBMHS | 12.9% referred to SBMHS (past academic year) | Nine reasons for not seeking help | 15 (moderate) |

| 936 Asian American | Asian American | SDQ (13.9% elevated symptoms) CIS | 3.2% referred to SBMHS (past academic year). | ||||||||||

| Guterman et al. [37] | 858 Arab | 14–17 | Israel | 46.7% Arab and 53.3% Jewish | 57.9% | No information | School | Emotional distress—exposure to community violence | Adapted version of My ETV (87% witnessed ≥ 1 act of community violence (past year) | Any Professional Help | 11.5% sought help from MH professional, 10% from youth group or religious leader, 9.2% from teacher and 8.7% from medical professional | 16 reasons for not seeking help | 18 (high) |

| 977 Jewish | 14-17 | 54.5% | Adapted version of My ETV (92.5% witnessed ≥ 1 act of community violence (past year) | 4.1% sought help from MH professional, 3.5% from youth group or religious leader, 2.7% from teacher and 2.1% from medical professional | |||||||||

| Haavik et al. [38] | 1249 | M = 17.6, SD = 1.15 | Norway | No information | 56% | Rural and urban | School | MH in general | Not assessed | MH Services | School-based MH services: 11–29.8%, Specialist MH services: 9.7–10.5%, Youth health station/GP: 16.2–32.9% | Nine barriers to help-seeking; 5-point Likert scale | 18 (high) |

| Khairani et al. [39] | 21 (out of 215 screened for depression symptoms)b | 13–20 | Malaysia | 99.1% Malays, 0.9% Indians | 57% | Rural | Primary care clinic | Depression | Structured self-report questionnaire with ten questions on depressive symptoms based on the DSM-IV (100% met criteria for depression) | Medical professionals | 9.5% of those reporting significant depressive symptoms had sought medical help for these | No details about the barrier measure | 15 (moderate) |

| Kuhl et al. [40] | 280 | 14–17 | USA | 84% Caucasian, 9.8% Asian American, 4% Hispanic, 0.4% African American, 2.1% no ethnicity specified. | 50% | No information | School | MH in general | 50-item measure of physical and psychiatric symptoms developed by Dubowa | Any professional help | 30% of participants were currently or previously in therapy | BASH | 16 (moderate) |

| Lubman et al. [41] | 2456 | 14–15 | Australia | 84.2% born in Australia; 1.9% in New Zealand, 1.4% in the United Kingdom, 1.1% in India and 1.0% in China | 50% | Rural and urban | School | Depression and alcohol abuse; any professional help | Not assessed | Any professional help | 30% sought help for MH problems from teachers or health professionals | BASH-B | 20 (high) |

| Meredith et al. [24] |

184 depressedb 184 non-depressedb |

13–17 | USA | 14.2% White, 32.7% Black, 49.3% Hispanic, 3.8% Other | 78% | No information | Primary care clinic | Depression | DISC—depression module (100% of ‘depressed’ and 0% of ‘non depressed’ sample met the diagnostic criteria for depressive disorder in last 6 months) | Any professional help |

55% reported receiving depression counselling (6 months after depression was identified) No information |

Seven barriers; 5-point Likert scale | 20 (high) |

| Muthupalani-appen et al. [42] |

131 smokers 268 non-smokers |

13–17 | Malaysia | No information | No information | No information | School | Emotional and behavioural problems | YSRa | Primary care providers |

5.3% sought help No information |

16 reasons for not seeking help | 15 (moderate) |

| Samargia et al. [43] | 497 (those who reported having foregone mental health care from 878 screened) | 16 | USA | 86.9% White, 0.9% African American, 3.2% Native American, 6.1% multiracial, 1.7% Asian, 1.1% Hispanic | 65% | Rural and urban | School and community centres | Psychological or emotional problems | DHS and DHHSa | Mental health services | 100% | 11 reasons for not seeking help | 17 (high) |

| Sharma et al. [44] | 354 | 13–17 | India | No information | 48% | Urban | School | Depression | Not assessed | Any professional help | No information | No details about the barrier measure | 9 (low) |

| Sheffield et al. [45] | 254 | 15–17 | Australia | 89.7% Australian and 10.3% from other countries (mainly Asia, Europe, and the United Kingdom) | 51% | No information | School | MH in general | The DASS-21a | Any professional help | 9.1% sought help for a mental illness; 31.2% for a personal, emotional or behavioural problem (past 12 months) | Nine barriers to help-seeking | 17 (high) |

| Sylwestrzak et al. [46] | 10,123 | 13–18 | USA | 65.6% non-Hispanic whites, 15.1% non-His- panic blacks, and 14.4% Hispanics | 49% | Rural and urban | Household and school | Emotional and behavioural problems and coping with stress | As a part of NCS-A Study they were asked about MH symptomsa | Any professional help | > 63% reported seeking treatment to manage and cope with emotions; 11.6% to help with controlling problem behaviours and 6.9% to help cope with stress | 14 reasons for not seeking help | 14 (moderate) |

| Wilson and Deane [47] | 1037 | 13–21 | Australia | 95% Australian, remaining 5% European, Asian, North or South American, Middle Eastern, and ‘other’ | 59% | Urban | School and youth community groups | Psychological problems | Not assessed | MH Services | No information | BASH-B | 18 (high) |

| Wilson et al. [28] | 1184 | 11–17 | Australia | No information | 50% | Urban | School | Depression | CES-D (10.5% with moderate–severe depression symptoms) | MH Services | No information | Open-ended question about perceived barriers to seeking professional help | 16 (moderate) |

| Wilson et al. [30] | 173 (trial) | 14–16 | Australia | 88% Australian, 6% European, 2% Asian | 58% | No information | School | Psychological problems | Not assessed | Help-seeking with GPs | 6.9–8.1% had ≥ 1 consultation with GP about psychological health | BETS | 18 (high) |

| 118 (comparison group) | 86% Australian, 9% European, 2% Aboriginal | 60% | 1.7–4.2% had ≥ 1 consultation with GP about psychological health | ||||||||||

| Wu et al. [48] | 119 | 7–13 | USA | 82% White, 12% African American, 3% Asian, 3% other | 50% | No information | Community mental health centres | Paediatric anxiety | MASC, CAIS-C/P, CDI, PARS, ADIS-IV-C/P (66% GAD, 43% Social Phobia, 41% ADHD, 39% Separation Anxiety, 29% Specific Phobia) | MH Services | 100% | TAQ-CA | 20 (high) |

CAIS-C/P Child Anxiety Impact Scale-Child/Parent Report, CDI Children’s Depression Inventory, CES-D Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, CIS Columbia Impairment Scale, DASS-21 Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, DHS Minnesota Students Survey, DHSS Youth Risk Behaviour Survey, DISC Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, DUSI Drug Use Screening Inventory, HUQ Help-Seeking Utilization Questionnaire, MASC Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, MH mental health, My ETV My Exposure to Violence Scale, PARS Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale, SAS Self-rating Anxiety Scale, SBMHS school-based mental health services, SDQ Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, SIQ-JR Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire, TAQ-CA Treatment Ambivalence Questionnaire-Child (Anxiety) Version, YSR Youth Self-Report

aResults of MH assessment not reported. ADIS-IV-C/P Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child and Parent Versions, BASH Barriers to Adolescents Seeking Help, BASH-B the brief version of the Barriers to Adolescents Seeking Help scale

bMental health assessment used to identify participants. BETS Barriers to Engagement in Treatment Screen, BDI-IA Beck Depression Inventory, BHS Beck Hopelessness Scale

cThe same methods were used in baseline screening

Table 2.

Characteristics of qualitative studies

| References | Number of participants reporting barriers/facilitators | Age (range) | Country | Ethnicity | Females (%) | Area of living | Setting | Focus of the study | Mental health assessment | Source of professional help | Service use | Barrier/facilitator measure—details | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balle Tharaldsen et al. [49] | 8 | 17–18 | Norway | 88.5% Norwegian, 12.5% immigrant background. | 75% | No information | School | MH in general | No previous MH problemsb | Any professional help | 0% current, 25% previous contact with professional help. | Interviews | 17 (high) |

| Becker et al. [50] | 13 | 12–17 | USA | Majority Caucasian | 38% | No information | Community—outreach and support programmes for military families | MH in general | Not assessed | MH services | No information | Interviews and focus groups | 16 (high) |

| Breland-Noble et al. [51] | 29 | 11–17 | USA | African American | No information | Rural, urban and suburban | No information. | Depression | Not assessed | Any professional help | No information | Interviews and focus groups | 12 (moderate) |

| Bullock et al. [52] | 15 | 14–18 | Canada | 100% Canadian with heterogeneous ethnicities (i.e. mixed European, Aboriginal). One youth was a 2nd generation migrant. | 87% | No information | The Depressive Disorders (outpatient) Program of a psychiatric hospital | Suicidality | K-SADS-PL, SCID-II (53% depressive disorder, 33% cluster B personality disorder) questions about suicidality (60% lifetime suicide attempt, 40% multiple attempts) | Any professional help | 100% | Interviews | 12 (moderate) |

| Bussing et al. [31] | 148 | 14–19 | USA | No information | 59% | Rural and urban | School | ADHD | Screening questions with parents and CASA (74% ADHD high risk). | Psychiatric/medical and psychological help | 57% had a previous ADHD treatment | Open-ended survey questions | 14 (moderate) |

| Chandra and Minkovitz [53] | 57 | 13–14 | USA | 30% African American | 74% | Suburban | School | MH in general | Not assessed | MH services | 38.6% within and 10.5% outside the school | Interviews | 16 (high) |

| Clark et al. [54] | 29 | 12–18 | Australia | No information | 0% | Rural and urban | School and MH Clinic | Clinical anxiety | 28% history of anxiety diagnosisb | Any professional help | 28% had previously sought professional help | Interviews and focus groups | 17 (high) |

| De Anstiss and Ziaian [55] | 85 | 13–17 | Australia | 100% refugees of mixed ethnic backgrounds | 56% | No information | Community—refugee centres, programmes, schools | MH in general | Not assessed | MH services | Not clear | Focus groups | 15 (moderate) |

| Del Mauro and Jackson Williams [56] | 31 | 7–18 | USA | 87.1% Caucasian, 3.2% African American, 3.2% Asian, 3.2% Hispanic, 3.2% not reported | 71% | Rural and urban | Community | MH in general | Not assessed | Psychological help | 19.4% ≥ 1 therapy session | Focus groups | 15 (moderate) |

| Doyle et al. [57] | 35 | 16–17 | Ireland | No information | 66% | Urban | School | MH in general | Not assessed | Help-seeking in schools | No information | Focus groups | 12 (moderate) |

| Fleming, Dixon and Merry [58] | 39 | 13–16 | New Zealand | 49% Maori, 38% Pacific Islands, 10% New Zealand European | 26% | No information | School—alternative schooling programmes for students excluded or alienated from mainstream education | Depression | Not assessed | Health providers and computer-based help | No information | Focus groups | 16 (high) |

| Fornos et al. [59] | 65 | 13–18 | USA | 89% Mexican–American | No information | Urban | School | Depression | Not assessed | Any professional help | No information | Focus groups | 10 (low) |

| Fortune et al. [19, 20] | 2954 (out of 6020 screened)c | 15–16 | UK | 82% White, 12% Asian, 3% Black and 3% Other | 54% | No information | School | Self-harm and suicidality | Questions about self-harm (10% lifetime self-harm) and scales to measure depression, impulsivity, anxiety and self-esteema | Any professional help | No information | Open-ended survey questions | 13 (moderate) |

|

332 who did not seek help before self-harm (out of 593 with a lifetime history of self-harm)c 412 who did not seek help after self-harm (out of 593 with a lifetime history of self-harm)c |

15–16 | UK | 88% White | Around 75% | No information | School | Self-harm | Questions about self-harm (100% lifetime history of self-harm) and scales to measure depression, impulsivity, anxiety and self-esteema | Any professional help |

14% got help before the episode of self-harm 1.4% got help after the episode of self-harm |

Open-ended survey questions | 13 (moderate) | |

| Francis et al. [60] | 52 | 14–16 | Australia | No information | 71% | Rural | School | MH in general | Not assessed | Any professional help | No information | Focus groups | 16 (high) |

| Gonçalves et al. [61] | 16 | 12–17 | Portugal | 25% Portuguese (African descendent)25% Cape Verde, 18.8% Brasil, 18.8% Angola, 12.5% Other | 31% | No information | School | MH in general | Not assessed | Any professional help | 31.3% had previous psychologist visit | Focus groups | 14 (moderate) |

| Gronholm et al. [62] | 29c | 12.2–18.6 | UK | 65.5% White, 31% Black, 3.4% Asian | 65.50% | Urban | School | Inter-/externalising disorder and risk of developing psychotic disorder |

SDQ (100% borderline or clinical level of inter-/externalising disorder PLE (100% ≥ 1 ‘yes’ response to question regarding psychotic-like experiences) |

Any professional help | No information | Interviews | 18 (high) |

| Hassett and Isbister [63] | 8c | 16–18 | UK | No information | 0% | No information | Clinic—CAMHS | Self-harm and suicidality | ≥ 2 episodes of self-harm (past 12 months)b | MH services | 100% | Interviews | 17 (high) |

| Huggins et al. [64] | 6 | 18 | USA | No information | No information | Rural and urban | School | MH in general | Not assessed | School-based mental health services | No information | Interviews | 17 (high) |

| Kendal et al. [65] | 23 | 11–16 | UK | No information | 65% | Urban | School | Emotional difficulties | Not assessed | School-based pastoral support | 39% had used the MH service in school | Interviews | 15 (moderate) |

| Klineberg et al. [66] | 30 | 15–16 | UK | 40% Asian, 23% Black, 20% Mixed ethnicity, 13% White British and White Other | 80% | Urban | School | Self-harm | Adapted version of A-Cope (33% never self-harmed, 30% self-harmed once, 37% more than once) | Any professional help | No information | Interviews | 16 (high) |

| Leavey, Rothi and Paul [67] | 48 | 14–15 | UK | No information | 50% | Urban | School | Emotional and mental health problems | Not assessed | Primary care providers | No information | Focus groups | 11 (low) |

| Lindsey, et al. [68] | 16 | 11–14 | USA | 100% African American | 50% | Urban | School | MH in general | Not assessed | MH services | 44% received school-based counselling | Focus groups | 17 (high) |

| Lindsey et al. [21, 22] | 18c | 14–18 | USA | 100% African American | 0% | Urban | Community based mental health centres and after-school programs for youth | Depression | CES-D (100% elevated levels of depression symptoms) | MH services | 55% of them were in treatment | Interviews | 16 (high) |

| Mcandrew and Warne [69] | 7c | 13–17 | UK | 100% White British | 100% | No information | n/a | Self-harm and suicidality | 100% experienced self-harm and/or suicidal behaviourb | Any professional help | No information | Interviews | 13 (moderate) |

| Meredith et al. [24] | 16c | 13–17 | USA | No information | No information | No information | Primary care clinic | Depression | Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children—depression module (100% met criteria for depression) | Any professional help | Not clear | Interviews | 10 (low) |

| Mueller and Abrutyn [70] | 10 | No information | USA | Upper middle class community | No information | Suburban | Community | Suicidality | Not assessed | Any professional help | No information | Interviews and focus groups | 11 (low) |

| Pailler et al. [71] | 60 | 12–18 | USA | 65% African American, 27% White, 8% multiracial | 52% | Urban | Tertiary care children’s hospital | Depression | Not assessed | MH services | No information | Interviews | 18 (high) |

| Prior [72] | 8 | 13–17 | UK (Scotland) | No information | 75% | No information | School | MH in general | Not assessed | School counselling | 100% received school counselling | Interviews | 15 (moderate) |

| Timlin-Scalera et al. [73] | 26 | 14–18 | USA | 100% White | 15% | Suburban | School | MH in general | Not assessed | Any professional help | Not clear | Interviews | 17 (high) |

| Wilson and Deane [74] | 23 | 14–17 | Australia | 91% Australians of European descent, 4% Aboriginal, 4% Pakistani | 52% | Urban | School | MH in general | Not assessed | Any professional help | No information | Focus groups | 16 (high) |

| Wisdom et al. [75] | 22 | 14–19 | USA | 90% White (non-Hispanic), other people with African, Hispanic, and Asian heritage | 59% | No information | School and MH Clinic | Depression | Assessed by primary care providersa | Primary care providers | Not clear | Interviews and focus groups | 16 (high) |

CASA Child and Adolescent Services Assessment, CES-D Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, K-SADS-PL Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version, MH mental health, SCID-II Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II

aStudy does not provide results of MH assessment

bStudy does not provide information on how MH was assessed

cMental health assessment used to identify participants

Studies varied widely on sample size (from 6 to 10,123), participants’ age (from 7 to 21 years), country (with 48% of studies conducted in North America, 24% in Europe, 20% in Australia and 8% in Asia), demographic profiles (with 20% of studies focused on specific ethnic/gender groups and others with more varied samples), recruitment setting (with 72% of studies conducted in schools, 17% in (mental) health settings, and the others in varying community settings) and the type of mental health problem that was a focus of the study (with 30% of studies focused on mental health in general and the remaining studies focused on specific mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and ADHD). In half of the studies participants’ mental health was assessed (all of these studies assessed young people’s mental health using questionnaire measures, with the exception of four studies that used a standardised diagnostic assessment). Similarly, studies addressed various types of professional support, with some (9%) focused on school-based (mental health) services and the majority of remaining studies focused on any professional help (50%) or on support available in a specific (mental) health setting (40%). In 41% of studies, participants’ service use was not reported or assessed, and in others, some (2–57%) or all participants had received professional help for their mental health problems.

In quantitative studies, young people were most commonly asked to endorse the presence or absence of barriers from a list, or rate barriers using a 4–7 point Likert response scale. Three quantitative studies asked open questions about help-seeking [26–28]. Less than a third (30%) of quantitative studies reported facilitators to help-seeking, with two of those studies reporting facilitators only [29, 30].

The majority of qualitative studies used one-to-one interviews (45%), focus groups (32%), or both (16%) to collect data, with the exception of two studies where they applied a qualitative approach to analyse responses to open-ended survey questions [19, 20, 31]. Unlike quantitative studies, more than a half (58%) of qualitative studies reported facilitators to help-seeking, as well as barriers.

Quality ratings

Overall, the quality of the studies varied, ranging from ‘low’ to ‘high’, with 65% of quantitative and 52% of qualitative studies rated as ‘high’ quality, and 4% of quantitative and 13% of qualitative studies rated as ‘low’ quality. The weak aspects of qualitative studies tended to relate to methodological issues, such as clarity and appropriateness of sampling strategy (e.g. insufficient detail on how study participants were selected), data collection and analysis methods (e.g. only a very brief description of data analysis), whereas quantitative studies most commonly failed to describe the barrier/facilitator measure’s robustness (e.g. no details given about the measure’s psychometric characteristics).

Barrier/facilitator themes

Four barrier/facilitator themes were identified from both the qualitative and quantitative studies. The themes relate to (1) young people’s individual factors, (2) social factors, (3) factors related to the relationship between the young person and the professional and (4) systemic and structural factors. Barrier and facilitator themes and subthemes are summarised below. Barrier and facilitator themes and subthemes identified in each study are available in Online Resource 5.

Young people’s individual factors

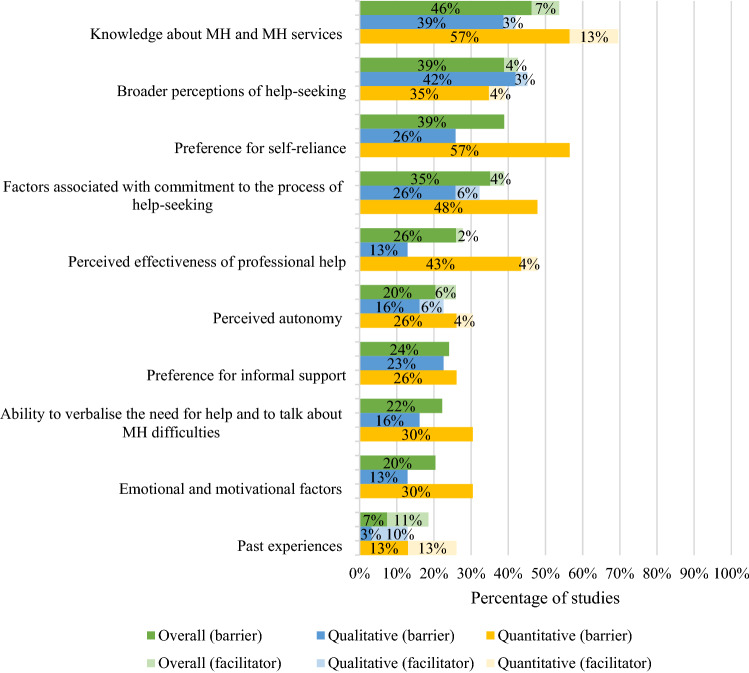

The majority (96%) of studies reported barriers and facilitators related to individual factors. Subthemes and their distribution across all studies, and across qualitative and quantitative studies separately are outlined in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of all (percentage of 54 included samples that reported barrier/facilitator), qualitative (percentage of 31 included qualitative samples that reported barrier/facilitator) and quantitative (percentage of 23 included quantitative samples where a ‘large’ (> 30) or ‘medium’ (10–30) percentage of participants endorsed the barrier/facilitator) studies reporting barriers and facilitators relating to young people’s individual factors

Barriers and facilitators related to knowledge about mental health and mental health services were reported in more than half (53%) of the studies, and with high endorsement rates (> 30% of participants). Young people reported not knowing where to find help and/or whom to talk to [20, 34, 37, 38, 42–46, 64, 65, 69, 73, 74] and failing to perceive a problem as either serious enough to require help [20, 63] or mental health related [32]. Young people’s broader perceptions of help-seeking were reported as barriers in 39% of studies, and as facilitators in 4%. This subtheme captured young people’s general attitudes towards mental health and help-seeking [31, 49, 53, 55, 59], help-seeking expectations [20, 27, 31, 33, 37, 38, 46, 48, 54, 59, 68, 75] and perceptions about how help-seeking reflects on their character, such as perceiving help-seeking as a sign of weakness [21, 49, 54, 60, 63, 73, 75]. The latter was reported in all studies that included male-only samples. Young people commonly (in 39% of the studies) endorsed the barrier of refusing to seek help because of a desire to cope with their problems on their own [20, 21, 24, 26–28, 33, 34, 37, 40–42, 45–47, 50, 54, 56, 61, 68, 73]. This subtheme was reported in nearly all studies that included young people with elevated levels of depression symptoms or experiences of self-harm, and mostly in quantitative studies with high rates of endorsement. In 35% of the studies, young people reported barriers related to uncertainty about whether problems were serious enough to require help [34, 35, 37, 40, 42, 62, 66, 73, 74] and expectations that the problems would improve on their own [33–35, 40, 42, 43, 46]. Young people also endorsed barriers which related to a reluctance to attend appointments and adhere to recommended treatments [24, 71]. Factors associated with commitment to the process of help-seeking were usually endorsed with a high frequency within quantitative studies. Around a quarter of studies reported the perceived effectiveness of professional help to be the reason for (not) seeking professional help, with most studies reporting that young people were doubtful about the effectiveness of professional help [31–35, 37, 40, 42, 44–46, 48, 50, 67, 72]. This reason was endorsed by young people with or without previous experience of professional help. Notably, perceived effectiveness was more commonly reported in quantitative studies than qualitative studies. The extent to which young people perceive help-seeking as their own decision was reported in a quarter of the studies. Young people reported that they were more likely to seek help if they perceived it to be their own choice [65, 72] and less likely to seek help if they perceived it as their parents’/teachers’ choice [48, 61, 67]. A preference for informal support was reported as a barrier to seeking professional help in 24% of studies; young people reported that they would prefer to discuss their mental health difficulties with family members and friends than professionals [22, 26, 34, 40, 42]. The subtheme of young people’s ability to verbalise the need for help and to talk about mental health difficulties was the next most common barrier to help-seeking, and endorsed by young people in 22% of studies overall, and more commonly reported in quantitative than qualitative studies. One-fifth of the studies reported emotional and motivational factors related to the nature of their problem, such as anxiety [39–41, 43, 47, 69] and depression symptoms [20, 27, 33, 40], and a lack of motivation [54, 58] as barriers to seeking professional help. Unsurprisingly, anxiety and depression symptoms were most frequently reported as posing barriers in the studies that included participants with elevated levels of psychological distress. This subtheme only captured barriers and was more frequently reported in the quantitative studies than qualitative studies. Young people also reported past experiences to be both facilitators [26, 40, 47, 53, 73, 74] and barriers [35, 40, 46, 53] to seeking professional help for their mental health problems. Past positive experience was the most commonly reported facilitator, reported in 15% of studies.

-

2.

Social factors

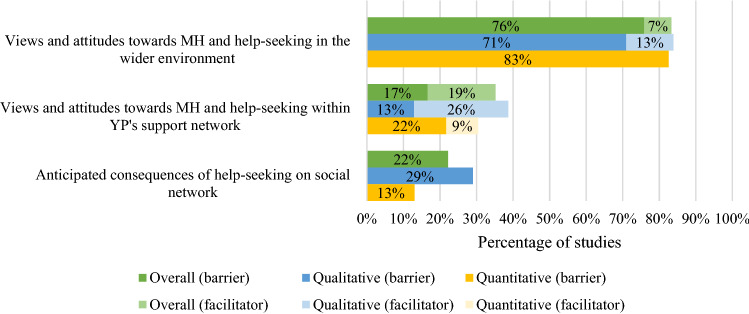

The second theme describes barriers and facilitators related to social factors and this theme was reported in 92% of studies. Subthemes in this category are outlined in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of overall (percentage of 54 included samples that reported barrier/facilitator), qualitative (percentage of 31 included qualitative samples that reported barrier/facilitator) and quantitative (percentage of 23 included quantitative samples where a ‘large’ (> 30) or ‘medium’ (10–30) percentage of participants endorsed the barrier/facilitator) studies reporting barriers and facilitators relating to social factors

The vast majority of studies reported barriers (76% of studies) related to perceived stigma [19–21, 26, 27, 31, 32, 49, 50, 54–62, 64, 68, 69, 72, 73] and young people’s experienced and/or anticipated embarrassment as a consequence of negative public attitudes [20, 22, 27, 28, 32, 33, 36, 37, 40–42, 44, 47–49, 58, 61, 64, 69], and these barriers were usually reported by a high percentage of young people within studies. Reduced public stigma and public normalisation of help-seeking were reported as related facilitators in four (13%) qualitative studies [57, 63, 72, 74]. Views and attitudes towards mental health and help-seeking within young people’s support networks, such as family, friends, teachers and GPs, were reported as barriers in 17% of studies, and as facilitators in 19% of studies. In most of these studies, these barriers/facilitators were reported by a high percentage of participants. Notably, positive views and encouragement from young people’s support networks were commonly reported facilitators (26% of qualitative and 9% of quantitative studies) [21, 32, 52, 59, 61, 63, 72, 73]. This subtheme was more frequently reported in studies including ethnically diverse samples, ethnic minorities or only male participants than studies with predominantly Caucasian, and mixed-gender samples. Anticipated consequences of help-seeking on young people’s social network included the fear of being taken away from their parents [59], fear of losing status in a peer group [49] and making their family angry or upset [48] and were reported as barriers in 29% of qualitative and 13% of quantitative studies.

-

3.

Relationship factors

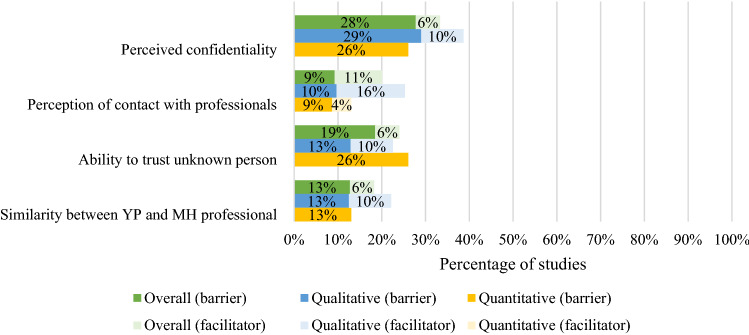

A large proportion of studies (68%) reported barriers and facilitators related to the relationship between the young person and a mental health professional. The distribution of subthemes across studies overall, and among qualitative and quantitative studies, is outlined in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of overall (percentage of 54 included samples that reported barrier/facilitator), qualitative (percentage of 31 included qualitative samples that reported barrier/facilitator) and quantitative (percentage of 23 included quantitative samples where a ‘large’ (> 30) or ‘medium’ (10–30) percentage of participants endorsed the barrier/facilitator) studies reporting barriers and facilitators relating to relationship factors

Issues related to perceived confidentiality were reported as barriers in 28% and facilitators in 6% of the studies [19, 29, 33, 36, 37, 39, 45, 47, 50, 56, 57, 59, 62, 64–66, 69, 73, 74]. Young people also reported concerns regarding disclosing personal information to a person they do not know well [22, 26, 28, 32, 33, 35, 42, 57, 58, 65, 68, 72, 74]. Barriers and facilitators related to young people’s perceptions of contact with professionals were reported in one-fifth of the studies (20%). Young people reported that they are more likely to seek help if they feel respected [63, 66], listened to [29, 30, 69] and not judged [69], and less likely if they feel they are being judged or not taken seriously [20, 37, 38, 56, 69]. Lastly, young people endorsed barriers and facilitators related to similarities/differences between them and professionals in 13% and 6% of studies, respectively. This subtheme was most frequently reported in qualitative studies that included ethnically diverse samples, ethnic minorities and only male participants, and included references to the gender [63], ethnicity/race [21] and age [40, 47] of professionals.

-

4.

Systemic and structural factors

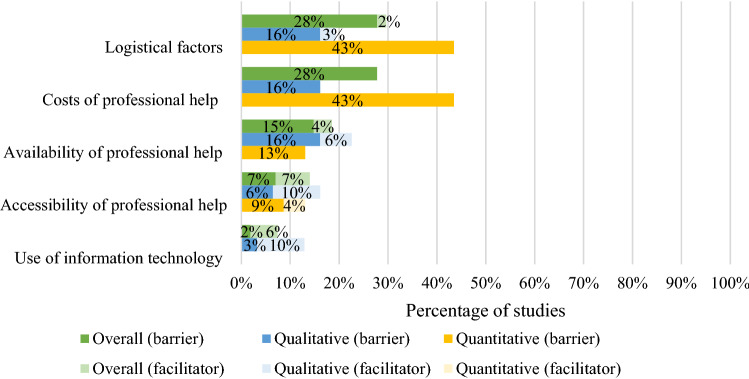

Barriers and facilitators related to systemic and structural factors were reported by 58% of studies overall. We identified six subthemes which are outlined in the Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Percentage of overall (percentage of 54 included samples that reported barrier/facilitator), qualitative (percentage of 31 included qualitative samples that reported barrier/facilitator) and quantitative (percentage of 23 included quantitative samples where a ‘large’ (> 30) or ‘medium’ (10–30) percentage of participants endorsed the barrier/facilitator) studies reporting barriers and facilitators relating to systemic and structural factors

Logistical factors, such as lack of time [24, 35, 40, 42], interference with other activities [24, 48], transportation difficulties [36, 42, 45] and costs associated with mental health services [24, 31, 35, 36, 38, 40–43, 45, 46, 50, 59, 61, 71] were reported in a large proportion of studies, and predominantly in quantitative studies. Two-thirds of studies reporting costs as a barrier to professional support were American and studies reporting transportation difficulties were more commonly conducted in rural areas than in cities. Young people also frequently reported barriers (15% of the studies) and facilitators (4% of the studies) related to the availability of professional help. Limited availability of professional services and excessive waiting times were the most commonly reported barriers within this subtheme [24, 26, 38, 54, 60, 68, 73]. Studies also reported barriers related to difficulties accessing or reaching support, for example, difficulties making an appointment or the attitude of staff towards them [19, 24, 33, 67]. The last subtheme captured young people’s perceptions of the role of information technology in help-seeking. In 10% of qualitative studies, young people identified opportunities to communicate distress and attend treatment via digital tools as facilitators to seeking/accessing treatment [54, 58, 63, 67]. All of these studies were conducted in the UK, Australia or New Zealand.

Robustness of data synthesis

Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding four ‘low quality’ studies (three qualitative and one quantitative) and re-examining the distribution of themes and subthemes among the remaining studies. There was minimal change in relation to the distribution of barrier/facilitator subthemes across qualitative and quantitative studies, and the overall results remained similar and conclusions unchanged.

Discussion

This review identified 53 studies addressing barriers and facilitators to seeking and accessing professional help for mental health problems as perceived by children and adolescents. We identified four themes across the studies. Barriers and facilitators related to young people’s individual factors and to social factors were identified in the vast majority of the studies. Young people also commonly reported barriers and facilitators related to the relationship between them and professionals and to systemic and structural factors.

Among barrier/facilitator subthemes, young people most frequently endorsed barriers and facilitators related to societal views and attitudes towards mental health and help-seeking, such as perceived public stigma and embarrassment associated with mental health problems. Young people also often perceived a lack of knowledge about mental health and the available help as a barrier to help-seeking. Young people with a prior experience of mental health difficulties reported that, during their difficulties, they had not recognised the need for professional help and had not perceived their problems as not serious enough to require help. Young people’s negative expectations and attitudes towards professionals, and perceiving help-seeking as a sign of one’s weakness, were commonly reported across studies as well. The latter subtheme was almost always reported in studies which included only male participants, highlighting potential gender differences in perceived barriers [54]. Adolescents also often endorsed a preference to rely on themselves when facing mental health difficulties rather than seeking professional help, which was again especially prominent in studies where participants had previous experience of mental health difficulties. Notably, this subtheme was far more commonly reported in quantitative than qualitative studies. Compared to qualitative studies, quantitative studies also more commonly reported barriers and facilitators related to a commitment to the process of help-seeking, such as not perceiving a problem as serious enough and waiting for the problem to improve on its own. Lastly, the extent to which young people believed information shared between them and professionals would be treated as confidential seemed to play a significant role in whether young people decide to seek help or not.

This review’s findings are broadly consistent with the previous review by Gulliver and colleagues that focused on young people’s help-seeking for anxiety, depression and distress [14]. Our review makes a significant further contribution to the existing literature by including young people’s perceived barriers for a wider range of mental health difficulties. In line with our findings, Gulliver et al. [14] identified that the most common barriers and facilitators related to public, perceived and self/stigmatising attitudes, mental health knowledge, young people’s preference for self-reliance and perceived confidentiality. However, Gulliver et al. [14] reported that structural factors (e.g. logistical factors and costs related to professional help), anxiety symptoms, and characteristics of mental health service providers were more common than we found in this review. Furthermore, while Gulliver et al. [14] found that past positive experiences of help-seeking was the most frequently reported facilitator across studies, we found that (1) positive attitudes and encouragement from young people’s support network and (2) positive perceptions of the contact between them and professionals were the most commonly reported facilitators. These observed differences are likely to reflect the larger number of studies included in the current review than the previous review, with nearly two-thirds of included studies published since the review by Gulliver et al. [14]. Furthermore, the current review excluded studies with only young adult participants (e.g. university students), who may well perceive different barriers and facilitators to seeking help than younger adolescents.

Implications

Our findings highlight many potential ways to improve access to treatment for young people experiencing mental health difficulties. First, the review highlights the ongoing need to minimise perceived mental health stigma among young people. There are a growing number of large-scale public health initiatives (e.g. Time to Change in the UK and Opening Minds in Canada) and school-based interventions [76] that are designed to reduce stigma and improve young people’s mental health and help-seeking literacy. Once the effectiveness of such programmes has been demonstrated, widespread dissemination is critical, making constructive conversations about mental health a part of the daily school routine. Our findings indicate that these interventions should focus on improving young people’s knowledge and understanding of mental health problems, [54], equipping young people with self-help skills and strategies [34], normalising mental health problems and the process of help-seeking [63, 74], ‘demystifying’ professional help [72], explaining which problems require help and which may not [20], and informing young people about where to find help and what to expect from it [30, 40], including explaining the therapeutic ‘ground rules’ (e.g. confidentiality). If we want to close the gap between high prevalence of mental health disorders and low treatment utilisation, sufficient service provision and professional support must be widely available for young people. Providing services within the school environment could address the systemic and structural barriers by minimising the effort required to access youth mental health services. Further, this could help reduce the barriers related to logistical factors, such as lack of time and transportation difficulties. Indeed, hundreds of schools in the UK already work collaboratively with local child and adolescent mental health services to offer specialist support and treatments to young people, teachers and parents at school [77]. With careful implementation, this may also be less stigmatising than a clinic environment [16], potentially helping greater numbers of young people to seek and access evidence-based treatments [78]. In addition, young people should be as equipped as possible to help themselves. Digital tools might be a means to increase access to support for mental health problems, and young people in studies in our review identified benefits of, for example, text messages [63, 67] to self-refer and to communicate with professionals directly Similarly, young people suggested using computerised psychological treatments [58], which might be especially appropriate for those who find it hard to talk about their feelings in person, and may help improve young people’s perceived independence. Equally, ensuring services are free at the point of use would minimise financial barriers to help-seeking/accessing. As young people’s support networks, especially families, seem to play the most important facilitative role in their process of help-seeking/accessing, professionals should be mindful about seeking appropriate family involvement, whilst balancing this against young people’s desire to make their own decisions about receiving help. It is clear that wherever interventions are provided, they must promise young people privacy [65] and promote their agency, control and self-determination [72].

Strengths and limitations

This review provides a comprehensive overview of the most common reasons given by young people about why they may or may not seek and access professional help when experiencing mental health difficulties. The inclusion of qualitative studies provided additional contextual information and more detailed insight into young people’s experiences than was commonly captured in quantitative studies. By including all recent studies focusing on a wide range of mental health difficulties, it provides an update to and extension of the previous review published nearly a decade ago. Although the eligibility criteria for this review were narrower (i.e. excluding the studies with only young adults), there were twice as many studies included in this review as in the previous one, highlighting the rapid development of this field and the need for an updated review. Finally, the review was conducted using rigorous and systematic methodology. Nevertheless, the review has some limitations. Due to the high variability of included studies it was not possible to carry out detailed group comparisons in relation to the type of mental health problem, source of professional help, study setting and participants’ treatment utilisation. Furthermore, only four studies used a standardised diagnostic assessment to assess participants’ mental health, and many studies did not report/assess participants’ mental health at all, making it hard to perform reliable comparisons of findings among adolescents with different mental health problems. Another limitation relates to the fact that the review only includes studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals and, therefore, findings from studies published in other languages and in alternative publications were not captured here. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the systematic search used to identify studies for inclusion in this review was conducted in February 2018 and, therefore, any relevant studies published since this date were not included in the review. Similar to previous research [12], our review identified that existing quantitative barrier/facilitator questionnaire measures are (1) more focused on barriers than facilitators and (2) tend to overlook some barriers/facilitators, especially those related to the role of young people’s support network and the characteristics of the relationship between young people and professionals. Results from the quantitative studies might, therefore, at least partly reflect the fact that young people were not asked about certain barriers and facilitators. These limitations of quantitative studies highlight the importance of including qualitative studies as well.

Conclusions and further research

The main reasons for (not) seeking and accessing professional help given by young people are those related to mental health stigma and embarrassment, a lack of mental health knowledge and negative perceptions of help-seeking. Young people also reported a preference for relying on themselves when facing difficulties, and issues with committing fully to the process of help-seeking/accessing. Widespread dissemination of evidence-based interventions delivered in schools targeting perceived public stigma and young people’s mental health knowledge is needed. Furthermore, the collaboration between schools and mental health services is essential to enable young people and their families to access evidence-based support within settings that minimise the logistical barriers. Mental health professionals should also offer young people different ways to access help on their own, including using digital tools, which have a potential to facilitate help-seeking behaviour and promote young people’s agency.

Our review identified a few possibilities for further research. The lack of established self-report quantitative measures of barriers and facilitators of seeking and accessing mental health support for young people highlights the need to develop and evaluate a new questionnaire. Findings from the qualitative studies should be considered when revising the content of the existing questionnaire items to ensure all relevant barriers/facilitators are captured, and their prevalence can be established. To inform mental health services for specific disorders in children and young people, studies examining barriers and facilitators to seeking and accessing professional help for children and adolescents experiencing specific mental health difficulties are required.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

JR is funded by the University of Reading through an Anniversary PhD Scholarship. CC, PJL and TR are funded by an NIHR Research Professorship awarded to CC (NIHR-RP-2014-04-018). PW is supported by an NIHR Post-Doctoral Fellowship (PDF-2016-09-092). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The authors thank Caitlin Thompson, BSc student of University of Reading, for help with abstract and full-text screening, and Dr Cyra Neave from the Anna Freud Centre for insight into practical aspects of school-based mental health interventions. The research materials can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, et al. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2015;56:345–365. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H, et al. Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pompili M, Serafini G, Innamorati M, et al. Substance abuse and suicide risk among adolescents. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262:469–485. doi: 10.1007/s00406-012-0292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riegler A, Völkl-Kernstock S, Lesch O, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse: an investigation in young Austrian males. J Affect Disord. 2017;217:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford T, Collishaw S, Meltzer H, Goodman R. A prospective study of childhood psychopathology: independent predictors of change over 3 years. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:953–961. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, et al. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007;370:859–877. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds S, Wilson C, Austin J, Hooper L. Effects of psychotherapy for anxiety in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadler K, Ti Vizard, Ford T, et al. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chavira DA, Garland A, Yeh M, et al. Child anxiety disorders in public systems of care: comorbidity and service utilization. J Behav Heal Serv Res. 2009;36:492–504. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9139-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chavira DA, Stein MB, Bailey K, Stein MT. Child anxiety in primary care: prevalent but untreated. Depress Anxiety. 2004;20:155–164. doi: 10.1002/da.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reardon T, Harvey K, Baranowska M, et al. What do parents perceive are the barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in children and adolescents? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26:623–647. doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0930-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien D, Harvey K, Howse J, et al. Barriers to managing child and adolescent mental health problems: a systematic review of primary care practitioners’ perceptions. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:e693–e707. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X687061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore A, Gammie J (2018) Revealed: hundreds of children wait more than a year for specialist help. Health Service J. https://www.hsj.co.uk/quality-and-performance/revealed-hundreds-of-children-wait-more-than-a-year-for-specialist-help/7023232.article. Accessed 15 Sept 2018

- 16.Department of Health, Department of Education (2017) Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: a green paper. Crown Copyright. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/664855/Transforming_children_and_young_people_s_mental_health_provision.pdf. Accessed 15 Sept 2018

- 17.Department of Health, Department of Education (2018) Government response to the consultation on transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: a green paper and next steps. Crown Copyright. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/728892/government-response-to-consultation-on-transforming-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health.pdf. Accessed 15 Sept 2018

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annu Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortune S, Sinclair J, Hawton K. Adolescents’ views on preventing self-harm. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:96–104. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fortune S, Sinclair J, Hawton K. Help-seeking before and after episodes of self-harm: a descriptive study in school pupils in England. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsey MA, Korr WS, Broitman M, et al. Help-seeking behaviors and depression among African–American adolescent boys. Soc Work. 2006;51:49–58. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindsey MA, Joe S, Nebbitt V. Family matters: the role of mental health stigma and social support on depressive symptoms and subsequent help seeking among African–American boys. J Black Psychol. 2010;36:458–482. doi: 10.1177/0095798409355796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS (2004) Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR), Edmonton

- 24.Meredith LS, Stein BD, Paddock SM, et al. Perceived barriers to treatment for adolescent depression. Med Care. 2009;47:677–685. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318190d46b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme. ESRC Methods Program. 2006 doi: 10.13140/2.1.1018.4643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyd CP, Hayes L, Nurse S, et al. Preferences and intention of rural adolescents toward seeking help for mental health problems. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freedenthal S, Stiffman AR. “They might think i was crazy”: young American Indians’ reasons for not seeking help when suicidal. J Adolesc Res. 2007;22:58–77. doi: 10.1177/0743558406295969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson CJ, Rickwood D, Deane FP. Depressive symptoms and help-seeking intentions in young people. Clin Psychol. 2007;11:98–107. doi: 10.1080/13284200701870954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Amico EJ, McCarthy DM, Metrik J, Brown SA. Alcohol-related services: prevention, secondary intervention, and treatment preferences of adolescents. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2004;14:61–80. doi: 10.1300/J029v14n02_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Marshall KL, Dalley A. Reducing adolescents’ perceived barriers to treatment and increasing help-seeking intentions: effects of classroom presentations by general practitioners. J Youth Adolesc. 2008;37:1257–1269. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9225-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bussing R, Koro-Ljungberg M, Nohuchi K, et al. Willingness to use ADHD treatments: a mixed methods study of perceptions by adolescents, parents, health professionals and teachers regina. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.009.Willingness. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandra A, Minkovitz CS. Stigma starts early: Gender differences in teen willingness to use mental health services. J Adolesc Heal. 2006;38:754.e1–754.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cigularov K, Chen PY, Thurber BW, Stallones L. What prevents adolescents from seeking help after a suicide education program? Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2008;38:74–86. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gould MS, Greenberg T, Munfakh JLH, et al. Teenagers’ attitudes about seeking help from telephone crisis services (hotlines) Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2006;36:601–613. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.6.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gould MS, Marrocco FA, Hoagwood K, et al. Service use by at-risk youths after school-based suicide screening. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:1193–1201. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181bef6d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo S, Kataoka SH, Bear L, Lau AS. Differences in school-based referrals for mental health care: understanding racial/ethnic disparities between Asian–American and Latino youth. School Ment Health. 2014;6:27–39. doi: 10.1007/s12310-013-9108-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guterman NB, Haj-Yahia MM, Vorhies V, et al. Help-seeking and internal obstacles to receiving support in the wake of community violence exposure: the case of Arab and Jewish Adolescents in Israel. J Child Fam Stud. 2010;19:687–696. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9355-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haavik L, Joa I, Hatloy K, et al. Help seeking for mental health problems in an adolescent population: the effect of gender. J Ment Heal. 2017 doi: 10.1080/09638237.2017.1340630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khairani O, Zaiton S, Faridah MN. Do adolescents attending Bandar Mas primary care clinic consult health professionals for their common health problems? Med J Malaysia. 2005;60:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuhl J, Jarkon-Horlick L, Morrissey RF. Measuring barriers to help-seeking behavior in adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 1997;26:637–650. doi: 10.1023/A:1022367807715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lubman DI, Cheetham A, Jorm AF, et al. Australian adolescents’ beliefs and help-seeking intentions towards peers experiencing symptoms of depression and alcohol misuse. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4655-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muthupalaniappen L, Omar J, Omar K, et al. Emotional and behavioral problems among adolescent smokers and their help-seeking behavior. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2012;43:1273–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samargia LA, Saewyc EM, Elliott BA. Foregone mental health care and self-reported access barriers among adolescents. J Sch Nurs. 2006;22:17–24. doi: 10.1177/10598405060220010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma M, Banerjee B, Garg S. Assessment of mental health literacy in school-going adolescents. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Heal. 2017;13:263–283. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2012.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheffield JK, Fiorenza E, Sofronoff K. Adolescents’ willingness to seek psychological help: promoting and preventing factors. J Youth Adolesc. 2004;33:495–507. doi: 10.1023/B:JOYO.0000048064.31128.c6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sylwestrzak A, Overholt CE, Ristau KI, Coker KL. Self-reported barriers to treatment engagement: adolescent perspectives from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Community Ment Health J. 2015;51:775–781. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson CJ, Deane FP. Brief report: Need for autonomy and other perceived barriers relating to adolescents’ intentions to seek professional mental health care. J Adolesc. 2012;35:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu MS, Salloum A, Lewin AB, et al. Treatment concerns and functional impairment in pediatric anxiety. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2016;47:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balle Tharaldsen K, Stallard P, Cuijpers P, et al. ‘It’s a bit taboo’: a qualitative study of Norwegian adolescents’ perceptions of mental healthcare services. Emot Behav Difficulties. 2017;22:111–126. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2016.1248692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becker SJ, Swenson RR, Esposito-Smythers C, et al. Barriers to seeking mental health services among adolescents in military families. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2014;45:504–513. doi: 10.1037/a0036120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Breland-Noble AM, Wong MJ, Childers T, et al. Spirituality and religious coping in African–American youth with depressive illness. Ment Heal Relig Cult. 2015;18:330–341. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2015.1056120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bullock M, Nadeau L, Renaud J. Spirituality and religion in youth suicide attempters’ trajectories of mental health service utilization: the year before a suicide attempt. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21:186–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chandra A, Minkovitz CS. Factors that influence mental health stigma among 8th grade adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2007;36:763–774. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9091-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clark LH, Hudson JL, Dunstan DA, Clark GI. Barriers and facilitating factors to help-seeking for symptoms of clinical anxiety in adolescent males. Aust J Psychol. 2018 doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]