Abstract

Objective:

Racial and ethnic disparities are well documented in psychiatry, yet suboptimal understanding of underlying mechanisms of these disparities undermines diversity, inclusion, and education efforts. Prior research suggests that implicit associations can affect human behavior, which may ultimately influence healthcare disparities. This study investigated whether racial implicit associations exist among medical students and psychiatric physicians and whether race/ethnicity, training level, age, and gender predicted racial implicit associations.

Methods:

Participants completed online demographic questions and 3 race Implicit Association Tests (IATs) related to psychiatric diagnosis (psychosis vs. mood disorders), patient compliance (compliance vs. non-compliance), and psychiatric medications (antipsychotics vs. antidepressants). Linear and logistic regression models were used to identify demographic predictors of racial implicit associations.

Results:

The authors analyzed data from 294 medical students and psychiatric physicians. Participants were more likely to pair faces of Black individuals with words related to psychotic disorders (as opposed to mood disorders), non-compliance (as opposed to compliance), and antipsychotic medications (as opposed to antidepressant medications). Among participants, self-reported White race and higher level of training were the strongest predictors of associating faces of Black individuals with psychotic disorders, even after adjusting for participant age.

Conclusions:

Racial implicit associations were measurable among medical students and psychiatric physicians. Future research should examine (1) the relationship between implicit associations and clinician behavior and (2) the ability of interventions to reduce racial implicit associations in mental healthcare.

Keywords: racial discrimination, psychosis, mood disorder, treatment adherence, race implicit bias, health disparities

Racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare are widely documented (1–4). For instance, Black or African American patients are more likely than White patients to receive suboptimal pain management, less likely to be referred for coronary artery bypass grafting when clinically indicated, and more likely to receive lower quality care (5–8). Racial disparities in healthcare are also prevalent in the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric patients (9, 10). However, these disparities remain inadequately studied in psychiatry. One of the most recognized racial disparity in psychiatry is the misdiagnosis of Black individuals with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Despite epidemiological studies suggesting a similar prevalence of schizophrenia across races, Black patients are over-diagnosed with schizophrenia and under-diagnosed with mood disorders (11, 12). Prior research suggests that African Americans are 3 to 5 times more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia compared to White patients (13). Analyses adjusting for patients’ sex, age, education and prior hospital admissions, indicate that race is the strongest predictor of schizophrenia diagnosis (13, 14).

Psychiatric misdiagnosis of Black individuals has been hypothesized to result from: 1) differences in the expression of psychiatric symptomatology resulting in diagnostic errors perhaps due to providers’ lack of cultural awareness, and/or 2) similar psychiatric symptomatology among races but measurable diagnostic errors due to stereotyping of patients by clinicians (15). Both hypotheses postulate, at their core, a process of systematic misclassification (i.e. bias) in the diagnosis of psychiatric illness that may be due to implicit (unconscious) or explicit (conscious) thoughts and feelings that become automatically activated (i.e. implicit associations) and which could involuntarily influence human behavior (misdiagnosis) (16). Although prior research has established that there are disparities in psychiatric diagnosis of Black individuals, few studies examine the underlying mechanisms driving the misdiagnosis (17–19).

Implicit associations or attitudes are appraisals that are made automatically, unconsciously, unintentionally, or without conscious and deliberative processing and may contribute to healthcare disparities (20, 21). Prior work has also conceptualized these implicit attitudes as a form of indirect racism (i.e. “practices that maintain or exacerbate unfair inequalities in power, resources or opportunities across racial, ethnic, cultural or religious groups”)(22). Studies indicate that medical providers’ race and gender affect their racial implicit associations. Specifically, Black physicians show weaker racial implicit associations than White physicians, female physicians show weaker racial implicit associations than male physicians, and older physicians may have stronger racial implicit associations than younger physicians (23–26). To our knowledge, studies have not evaluated the effects of training level (e.g. resident vs. attending) on racial implicit association strength in physicians. Furthermore, despite advances in racial implicit association research in other medical specialties, studies evaluating racial implicit associations in psychiatry are lacking.

Psychiatric diagnosis and treatment involve a complex array of clinical decisions that rely on physicians’ objective and subjective assessments of individuals. Diagnostic criteria (i.e. the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM] or the International Classification of Diseases [ICD]) and treatment algorithms attempt to reduce subjectivity by providing standardized criteria for diagnosis and treatment. However, due to comorbidity, overlapping criteria, and large variability in psychiatric phenomenology, these criteria and algorithms are still subject to interpretation by clinicians which can result in diagnosis and treatment differences, which makes racial implicit association research is particularly important in psychiatry.

Depending on training level, setting or resources, diagnosis can occur in high stress, fast-paced scenarios that may heighten biases and influence a cascade of long-lasting psychiatric ramifications, including inappropriate diagnosis resulting in unindicated or inappropriate treatment and its associated risks. A greater understanding of the role of implicit associations in diagnostic and treatment disparities may allow for targeted interventions to decrease disparities in mental health.

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether racial implicit associations were present among medical students and psychiatric physicians with regards to (1) psychiatric diagnosis (psychosis vs. mood disorders), (2) patient compliance (vs. non-compliance), and (3) psychiatric medication (antipsychotics vs. antidepressants) using Implicit Association Tests (IATs). This study also analyzed the role of the providers’ age, gender, race, and level of training on racial implicit associations.

Methods

This study used an internet-based cross-sectional survey design of medical students and psychiatric physicians in the United States. Recruitment was conducted from May 19 through December 4, 2017 via e-mail requests to medical schools, departments of psychiatry, minority group organizations and through social media (Facebook). Furthermore, recruitment was conducted at various conferences, including the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Annual Meeting, the American Psychiatric Association Components Meeting and the PsychSIGN Medical Student Conference. Recruitment materials stated that the study was about racial implicit associations in healthcare.

Potential participants were provided a secure and encrypted web-based survey that could be accessed via a computer or smartphone. Written informed consent was obtained electronically prior to participation. Participants completed two screening questions to determine whether they were indeed students or professionals in healthcare, answered demographic questions and completed 3 separate race IAT tasks (psychiatric diagnosis IAT, patient compliance IAT, and psychiatric medication IAT). Screening questions were: 1) Are you a student or a professional in the healthcare field? Answers: Yes or no, 2) Which of the following is NOT an antidepressant? Possible Answers: bupropion, citalopram, fluoxetine, risperidone, venlafaxine. Individuals were not compensated for their participation but were provided with their implicit association results and educational information on implicit associations. The current study was deemed exempt by the Yale University Institutional Review Board.

Implicit Associations Tests (IATs)

The IAT is frequently used to measure the strength of automatic associations as an index of implicit attitudes or unconscious biases (20, 27–29). The test is based on the assumption that concepts that are more easily associated cognitively will be sorted more quickly than concepts that not as easily associated. In the race IAT, participants are asked to quickly categorize standardized facial images (e.g. Black vs. White faces) and word stimuli (e.g. good vs. bad) into their respective categories using the left and right keys on their keyboard or handheld device. The IAT procedure has been validated in several populations, including populations of undergraduate students, and individuals taking the IAT through the Project Implicit website (20, 27–29). The IAT procedure has satisfactory psychometrics including internal consistency (ranging from 0.7 to 0.9)(30, 31) and test-retest reliability (median of 0.5)(32, 33). Additionally, studies demonstrate that the IAT is less susceptible to intentional deception than questionnaires (34, 35).

In this study, the IAT was adapted to include word stimuli related to psychiatric diagnosis (psychotic disorder vs. mood disorder), patient compliance (non-compliance vs. compliance), and psychiatric medications (antipsychotics vs. antidepressants). Task 1 (mood vs. psychosis IAT) included the following stimuli words: Hallucination, Delusion, Paranoia, Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective, Psychosis, Psychotic (category: psychotic disorders) vs. Bipolar, Manic, Depressed, Cyclothymia, Dysthymia, Depression, Hypomania (category: mood disorders). Task 2 (compliance vs. non-compliance IAT) included the following stimuli words: Non-Compliant, Reluctant, Resistant, Irresponsible, Difficult (category: non-compliance) vs. Compliant, Willing, Cooperative, Reliable, Amenable (category: compliance). Task 3 (antidepressant vs. antipsychotic IAT) included the following stimuli words: Risperidone, Quetiapine, Haloperidol, Olanzapine, Perphenazine, Aripiprazole, Clozapine (category: antipsychotics) vs. Sertraline, Fluoxetine, Paroxetine, Citalopram, Escitalopram, Venlafaxine, Duloxetine (category: antidepressants). The adaptation of the IAT was developed with support of Project Implicit, a non-profit organization founded by the developers of the IAT, after considering several factors including number of stimuli words, comparability of stimuli word length in contrasting categories, and randomization of the order of contrasting categories (20, 27–29).

Participants were asked to complete 3 IAT tasks and each task consisted of 7 blocks including practice blocks for each IAT task. Specific to this study, in half of the trials, the categories “Black” and “psychotic disorders/non-compliance/antipsychotic” shared a response key, and “White” and “mood disorders/compliance/antidepressants” shared another response key. In the other trials, the category pairing was reversed (i.e. categories “Black” and “mood disorders/compliance/antidepressants words” shared a response key). Participants were randomly assigned to see one of the two combinations first (i.e., African American with mood disorders/compliance/antidepressants and European American with psychotic disorders/non-compliance/antipsychotic, or the reverse). Task order (i.e Task 1, 2 and 3) was fixed for all participants. Images of adult male and female faces were counterbalanced on all tests. For more information about the IAT please visit www.implicit.harvard.edu.

IAT D-Scores

The differential response times (D-scores) are the calculated outputs of each IAT task. The underlying assumption is that concepts that are strongly implicitly associated are sorted faster and with fewer errors than concepts that are less strongly associated. The D-score is equivalent to the difference in average response time on the trials divided by the pooled standard deviation, after taking into account the practice-block data, use of error penalties, and individual-respondent standard deviation. For a full description of the IAT D-score calculation algorithm please refer to the paper by Greenwald, Nosek, and Banaji (27).

In this study, D-scores >0 imply faster pairing of Black faces with psychotic disorders/non-compliance/antipsychotics (or alternatively, White faces with mood disorders/compliance/antidepressants). D-scores <0 imply interpretations opposite to those given above. D-scores are interpreted as weak from 0.16 to 0.34, moderate from 0.35 to 0.64, and strong >0.65 (27). All D-score calculations were performed by Project Implicit.

Data management and statistical analysis

Data management and statistical analysis were performed using STATA/SE v16 (StataCorp). Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) and median (Interquartile Range or IQR). Categorical variables are presented as the number (proportion or %) of participants. P-values for continuous variables correspond to ANOVAs (for comparison of means between groups) and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for two-group comparisons and Kruskal–Wallis tests for comparisons of >2 groups (for comparison of medians between groups). P-values for categorical variables correspond to Pearson’s χ2 tests.

Three models for multivariable linear regressions and three models for multivariable logistic regression were estimated using the following list of predictors: participant race/ethnicity, age, gender, and level of training. We also estimated unadjusted bivariate associations and odds ratios between each of the predictors and each of the three outcomes (i.e. three IAT tasks). Only adjusted estimates are shown.

Linear regression was used to estimate multivariable changes in D-scores and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). For logistic regression, D-scores were dichotomized as scores ≥0.35 (moderate-to-strong associations) versus <0.35 (weak associations). Two types of multivariable logistic regression models were estimated. First, for multivariable logistic regression models in which the outcome was D ≥ 0.35 (i.e. the positive tail of the D-score distribution) the occurrence of the outcome implies moderate-to-strong pairing of Black faces with psychotic disorders (or White faces with mood disorders) in task 1, Black faces with non-compliance (or White faces with compliance) in task 2, and Black faces with antipsychotics (or White faces with antidepressants) in task 3.

Second, for multivariable logistic regression models where the outcome was D ≤ −0.35 (i.e. the negative tail of the D-score distribution) the occurrence of the outcome implied moderate-to-strong associations pairing White faces with psychotic disorders (or Black faces with mood disorders) in task 1, White faces with non-compliance (or Black faces with compliance) in task 2, and White faces with antipsychotics (or Black faces with antidepressants) in task 3.

Race Variable

Since the IAT asks participants to sort facial images by “Black” and “White” categories, participant’s race/ethnicity is also described as “White” and “Black” (instead of “European-American” and “African-American”) for consistency. Participants in the “Black” category self-identified in the survey as “Black or of African origin.” Those in the “White” category self-identified as “White or of European origin.” The “Hispanic” category includes individuals who self-identified as Hispanic or Latino regardless of race. There were insufficient numbers of other racial/ethnic minority participants for statistical analysis, so we grouped individuals who self-identified as Asian or Pacific-Islander as “Asian/Pacific Islander,”; we also grouped individuals who self-identified as Native American, mixed or selected the “Other” category in the questionnaire as “Native American, Mixed or other.”

Results

Study Sample

A total of 686 potential participants accessed the online survey, 126 were excluded because they answered screening questions incorrectly, 163 were excluded because they did not participate in any of the 3 IAT tasks, 103 were excluded because they were not medical students or psychiatric physicians (e.g. these providers were physicians outside of psychiatry, social workers, doctor of philosophy (Ph.D.), psychologist (Ph.D., or Psy.D.), psychology trainees, APRN, NP, PA). The final sample size for analysis was N=294.

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of included participants. Mean provider age (±SD) in the combined sample was 33.50 years (±10.46 years) and 63% were female. In terms of self-reported race-ethnicity, 51% identified as White, 16% as Black or African American, 13% as Hispanic, 12% as Asian or Pacific Islanders, and 8% as Native American, Mixed, or other. The provider sample included: 42% medical students, 21% psychiatry residents, 25% psychiatry fellows, and 12% board-certified psychiatrists.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and IAT D Scores by race/ethnicity

| Total Sample | White | African American or Black | Hispanic ethnicity, any race | Asian or Pacific Islander | Native American, Mixed or other | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=294 | n=151 | n=47 | n=37 | n=35 | n=23 | ||

| Demographics (predictor variables) | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Median (IQR) | 30.00 (26.00, 37.00) | 29.00 (26.00, 37.00) | 27.00 (25.00, 30.00) | 38.00 (33.00, 54.00) | 30.00 (27.00, 34.00) | 28.50 (25.00, 32.00) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 33.50 (10.46) | 33.01 (9.71) | 28.46 (6.37) | 42.65 (13.97) | 30.84 (5.75) | 30.14 (6.59) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male (%) | 105 (35.7%) | 57 (37.7%) | 11 (31.4%) | 14 (29.8%) | 16 (43.2%) | 7 (30.4%) | 0.70 |

| Female (%) | 185 (62.9%) | 93 (61.6%) | 24 (68.6%) | 32 (68.1%) | 21 (56.8%) | 15 (65.2%) | |

| Level of training | |||||||

| Medical Students (%) | 122 (41.5%) | 69 (45.7%) | 21 (60.0%) | 7 (14.9%) | 14 (37.8%) | 11 (47.8%) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatry residents (%) | 62 (21.1%) | 33 (21.9%) | 9 (25.7%) | 4 (8.5%) | 11 (29.7%) | 5 (21.7%) | |

| Psychiatry Fellows (%) | 73 (24.8%) | 35 (23.2%) | 3 (8.6%) | 18 (38.3%) | 11 (29.7%) | 5 (21.7%) | |

| Board-Cert Psychiatrist (%) | 36 (12.2%) | 14 (9.3%) | 2 (5.7%) | 17 (36.2%) | 1 (2.7%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| Outcome Variables | |||||||

| Task 1 (Diagnosis) | |||||||

| D score mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.34 (0.38) | 0.20 (0.36) | 0.07 (0.38) | 0.32 (0.32) | 0.01 (0.33) | <0.001 |

| D score median (IQR) | 0.2 (−0.0, 0.5) | 0.33 (0.08, 0.60) | 0.19 (0.02, 0.45) | 0.03 (−0.20, 0.33) | 0.25 (0.09, 0.52) | 0.05 (−0.24, 0.28) | <0.001 |

| D score ≥ 0.35 (%) | 115 (39.1%) | 71 (47.0%) | 12 (34.3%) | 11 (23.4%) | 17 (45.9%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.006 |

| D score ≤ −0.35 (%) | 17 (5.8%) | 5 (3.3%) | 7 (14.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.7%) | 3 (13.0%) | 0.010 |

| Task 2 (Compliance) | |||||||

| D score mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.32 (0.39) | 0.20 (0.29) | 0.01 (0.39) | 0.19 (0.31) | 0.04 (0.44) | <0.001 |

| D score median (IQR) | 0.3 (−0.1, 0.5) | 0.34 (0.10, 0.55) | 0.23 (−0.09, 0.36) | 0.05 (−0.27, 0.25) | 0.22 (−0.05, 0.41) | 0.10 (−0.14, 0.35) | <0.001 |

| D score ≥ 0.35 (%) | 95 (32.3%) | 60 (39.7%) | 9 (19.1%) | 11 (29.7%) | 10 (28.6%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.012 |

| D score ≤ −0.35 (%) | 21 (7.1%) | 8 (5.3%) | 7 (14.9%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.006 |

| Task 3 (Medications) | |||||||

| D score mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.34 (0.32) | 0.18 (0.33) | 0.14 (0.26) | 0.36 (0.33) | 0.09 (0.39) | <0.001 |

| D score, median (IQR) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) | 0.30 (0.14, 0.56) | 0.21 (−0.03, 0.38) | 0.16 (−0.08, 0.30) | 0.40 (0.14, 0.52) | 0.09 (−0.28, 0.30) | <0.001 |

| D score ≥ 0.35 (%) | 91 (31.0%) | 56 (37.1%) | 6 (12.8%) | 17 (45.9%) | 8 (22.9%) | 4 (17.4%) | <0.001 |

| D score ≤ −0.35 (%) | 7 (2.4%) | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (2.1%) | 1 (2.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0.34 |

Racial Implicit Associations in Mental Health Providers

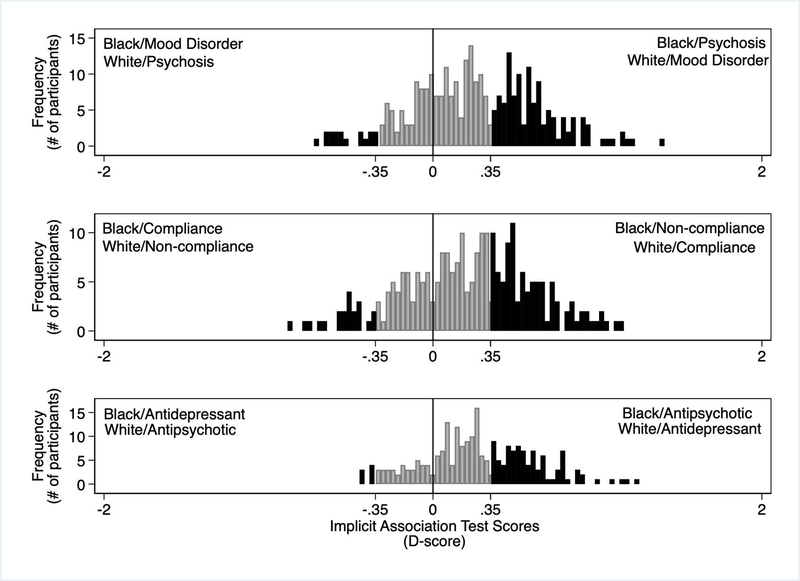

Figure 1 shows the distributions of D-scores by task. The mean D-score for the mood/psychosis IAT was 0.25 (SD= 0.38), the compliance/non-compliance IAT was 0.21 (SD= 0.39), and the antidepressant/antipsychotic IAT was 0.27 (SD= 0.33). A large proportion of the D-scores was observed to fall on the positive tail of the distribution (D-Scores ≥ .35) which denotes moderate-to-strong implicit associations pairing faces of Black individuals with psychosis, non-compliance, and antipsychotic words. Specifically, 39.12% (95% CI; 33.50–44.95%) of participants had moderate-to-strong implicit associations between Black faces and psychotic disorder words, 37.70% (95% CI; 31.69–44.00%) had moderate-to-strong implicit associations between Black faces and non-compliance words, and 38.72% (95% CI; 32.46–45.27%) had moderate-to-strong implicit associations between Black faces and antipsychotic medications. On the other hand, a small proportion of the D-scores was observed to fall on the negative tail of the distribution (D-Scores ≤ −0.35) which denotes moderate-to-strong pairing White faces with psychosis, non-compliance, and antipsychotic words. Specifically, 5.78% (95% CI ; 3.40–9.10%) of participants had moderate-to-strong implicit associations between White faces and psychotic disorder words, 8.33% (95% CI; 5.23–12.46%) had implicit associations between White faces and non-compliance words, and 2.98% (95% CI; 1.21–6.04%) had moderate-to-strong implicit associations between White faces and antipsychotic medications. Scores on the 3 tasks were positively and significantly correlated with each other, but the degree of correlation varied. Task 1 (Diagnosis) & Task 2 (Compliance) had a correlation of r=0.27 with a p-value <0.01. Task 1 (Diagnosis) & Task 3 (Medications) had a correlation of r=0.41 with a p-value <0.01. Lastly, Task 2 (Compliance) & Task 3 (Medications) had a correlation of r=0.32 with a p-value <0.01.

Figure 1:

Distributions of D-scores by Task. Positive and negative tails shown in black color. Range of low implicit association shown in gray.

Demographic Predictors of Implicit Association Scores

Figure 2 shows the demographic predictors of continuous implicit association scores (D-scores) using linear regression. Compared to White participants, Black participants had significantly lower D-scores in all tasks (i.e. scores showing weaker pairing of Black faces with psychosis/non-compliance/antipsychotics). Specifically, Black participants had significantly weaker associations pairing Black faces with psychotic disorders (βΔD = −0.32, p < 0.001), non-compliance (βΔD = −0.28, p < 0.001), and antipsychotic medications (βΔD = −0.17, p < 0.01) compared to White participants (reference group). Furthermore, “Native American, Mixed or other” participants had significantly weaker associations pairing Black faces with psychotic disorders (βΔD = −0.29, p < 0.001), non-compliance βΔD = −0.31, p < 0.001) and antipsychotics (βΔD = −0.26, p < 0.001) compared to White participants. Results for Hispanic and Asian participants varied across tasks and are described in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Demographic predictors of Implicit Association Test Scores (IAT D-Scores) using multivariable linear regression analyses. In this coefficient plot, the closed circles represent the point estimate (β coefficient) and the whiskers represent the 95% confidence interval.

In terms of level of training, compared to medical students (reference group), psychiatric physicians with higher levels of training had significantly stronger associations pairing Black faces with psychotic disorders or conversely White faces with mood disorders (psychiatric resident βΔD = 0.20, p < 0.001, psychiatric fellow βΔD = 0.23, p < 0.01, board-certified psychiatrist βΔD = 0.21, p < 0.05). These results were replicated in the antidepressant/antipsychotic IAT with the exception of board-certified psychiatrists (psychiatric resident βΔD = 0.16, p < 0.01, psychiatric fellow βΔD = 0.19, p < 0.01, board-certified psychiatrist βΔD = 0.04, p = NS). In the compliance/non-compliance IAT, associations with training level were smaller in magnitude and were not statistically significant (psychiatric resident βΔD = 0.07, p = NS, psychiatric fellow βΔD = 0.06, p = NS, board-certified psychiatrist βΔD = 0.01, p = NS).

In terms of providers’ self-reported gender, compared to male participants, female participants had significantly lower implicit associations of Black faces with antipsychotics (βΔD = −0.12, p < 0.01). There were no statistically significant differences between male and female participants in the diagnosis task (βΔD = −0.07, p = NS) or in the compliance task (βΔD = −0.09, p = NS). Age was not a significant predictor of implicit associations scores in any of the IATs.

Predictors and Odds of Moderate-to-Strong Implicit Association Scores

Table 2 shows multivariable logistic regressions results—the outcome for this analysis was the odds of participants having moderate-to-strong associations pairing Black faces with psychotic disorders/non-compliance/antipsychotics (positive tail of the distribution; D-score ≥0.35). Given the low number of participants with D-scores with moderate-to-strong associations pairing White faces with psychosis/non-compliance/antipsychotics (negative tail of the distribution; D-score ≤ −0.35) multivariable logistic regression could not be estimated. For the positive D-score tail (i.e. providers pairing Black faces with psychosis/non-compliance/antipsychotics), compared to White participants, Black participants had significantly lower odds of having moderate-to-strong associations (mood/psychosis IAT: OR = 0.23 p < 0.01, compliance/non-compliance IAT: OR = 0.30 p < 0.01, antidepressant/antipsychotic IAT: OR = 0.20, p < 0.01). Furthermore, compared to White participants, those in the race/ethnicity category “Native American, Mixed or other” also had significantly lower odds of having moderate-to-strong associations pairing Black faces with psychotic disorders/non-compliance/antipsychotic words (mood/psychosis IAT: OR = 0.23, p = 0.05, compliance/non-compliance IAT: OR = 0.26, p < 0.05, antidepressant/antipsychotic IAT: OR = 0.21, p < 0.05). For Hispanic and Asian participants, the odds for moderate-to-strong associations were not significantly different to those of White participants across tasks.

Table 2.

Demographic predictors of moderate-to-strong implicit association pairing Black faces with psychosis/non-compliance/antipsychotics (i.e. D scores ≥0.35, positive tail) using multivariable logistic regression

| Task 1: Mood vs. Psychosis IAT | Task 2: Compliance vs. Non-compliance IAT | Task 3: Antidepressant vs. Antipsychotic IAT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=289 | n=247 | n=231 | ||||

| VARIABLES | OR§ | 95% CI | OR§ | 95% CI | OR§ | 95% CI |

| 10-year age increase | 0.89 | 0.61, 1.30 | 0.81 | 0.52, 1.25 | 0.7 | 0.44, 1.13 |

| Sex (Female vs. Male) | 0.83 | 0.49, 1.41 | 0.93 | 0.52, 1.66 | 0.60 | 0.32, 1.09 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Asian | 0.69 | 0.31, 1.58 | 0.53 | 0.23, 1.25 | 0.46 | 0.18, 1.18 |

| Black/AA | 0.23*** | 0.10, 0.53 | 0.30*** | 0.12, 0.73 | 0.20*** | 0.07, 0.55 |

| Hispanic | 0.87 | 0.40, 1.87 | 0.48 | 0.21, 1.09 | 1.05 | 0.46, 2.41 |

| Native American, Mixed or other | 0.23** | 0.07, 0.76 | 0.26** | 0.08, 0.82 | 0.21** | 0.06, 0.80 |

| Level of training | ||||||

| Medical Student (ref) | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Psychiatry Residents | 3.41*** | 1.72, 6.80 | 1.46 | 0.70, 3.07 | 2.98*** | 1.37, 6.52 |

| Psychiatry Fellows | 4.43*** | 1.84, 10.66 | 1.45 | 0.57, 3.70 | 3.72** | 1.35, 10.27 |

| Board Certified Psychiatrist | 5.90*** | 1.90, 18.29 | 1.1 | 0.31, 3.86 | 2.93 | 0.77, 11.12 |

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

Odds Ratio >1 imply higher odds of moderate-to-strong association (i.e. D ≥ 0.35) pairing Black faces with Psychosis/Non-compliance/Antipsychotic words or White faces with Mood/Non-compliance/Antidepressant words. Odds Ratio <1 imply lower odds of such moderate-to-strong associations.

In the terms of level of training, compared to medical students, psychiatric residents, psychiatry fellows, and board-certified psychiatrists had higher odds of moderate-to-strong pairing of Black faces with psychotic disorders/antipsychotic words (mood/psychosis IAT OR for psychiatric residents = 3.41 p < 0.001, for psychiatric fellows OR = 4.43 p < 0.001, and for board-certified psychiatrists OR = 5.90, p < 0.01; antidepressant/antipsychotic IAT: the OR for psychiatric residents = 2.98 p < 0.01, for psychiatric fellows OR = 3.72 p < 0.05, and for board-certified psychiatrists OR = 2.93, p = NS). For the compliance/non-compliance IAT, the odds of moderate-to-strong association of Black faces with non-compliance were not statistically different among training levels.

With regards to participants’ reported gender, female participants had lower odds of moderate-to-strong pairing Black faces with psychosis/non-compliance/antipsychotics compared to male participants, but these differences were not statistically significant. Age was not significantly associated with higher odds of moderate-to-strong associations in any of the tasks.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess implicit associations with regards to mental health diagnosis, compliance, and treatment in medical students and psychiatric physicians. Results indicate that the majority of medical students and psychiatric physicians in our sample had IAT scores with moderate racial implicit associations regarding mental health diagnosis, patient compliance, and treatment. Specifically, a large proportion of participants had moderate associations of Black faces with psychosis, non-compliance, and antipsychotic words (or White faces with mood disorders, compliance, and antidepressants). Furthermore, this study demonstrates that a prescriber’s race/ethnicity and training level were significant predictors of racial implicit associations. Participants who self-reported a race/ethnicity other than White, tended to demonstrate lower implicit association of Black faces with psychosis, non-compliance, and antipsychotics. Additionally, higher level of training was associated with increased odds of moderate-to-strong pairing of Black faces with psychosis and antipsychotic medication words but not compliance words.

Overall, the study demonstrates the presence of measurable racial implicit associations with psychiatric diagnosis, compliance and medications. These results are consistent with studies in other medical specialties like pediatrics, surgery, and internal medicine, in which providers associated Black faces with non-compliance and other negative valence words using the race IAT (16, 26, 36–38). Other studies have also demonstrated that Black providers have lower implicit association scores than White providers (26, 38). In contrast, the effect of providers’ gender on racial implicit associations varied by task in this study. Given the variable findings related provider gender and IAT scores in previous studies (26, 38), it is unsurprising that we found the tendency of female providers to have reduced racial implicit associations was less robust than the effect of provider self-reported race. Further studies are needed to understand what factors drive stronger implicit associations in providers, particularly those who identify as White compared to other providers. Additionally, given that implicit association scores were predicted by participants’ self-reported race, particularly White race, these results suggest that a diverse mental health workforce may help mitigate implicit racial bias in psychiatry (39, 40).

Higher level of medical training was also associated with increased racial implicit associations involving psychiatric diagnosis and treatment but not compliance in this study. The results suggest that some racial implicit associations among medical students and psychiatric physicians may be learned or developed during training. Specifically, racial implicit associations that strengthened with psychiatric training were those related to psychiatry (i.e. psychiatric diagnosis and treatment words) and not those less specific to psychiatry (i.e. compliance and non-compliance words). Additionally, it is notable that psychotic disorder diagnoses and antipsychotic medications are not inherently negative compared to mood disorder diagnoses and antidepressants, respectively. Therefore, these results needs to be considered in the context of historical factors and structures that may have driven the development of these associations specifically in the US psychiatric workforce. These include targeted medication advertisement (e.g. Haldol advertisement for “assaultive and belligerent behavior” in the 1970s using images of a Black man with clenched fists and showing his teeth) and the publication of articles such as “The ‘Protest’ Psychosis, A Special Type of Reactive Psychosis” by Bromberg and Simon in 1968 in the Archives of General Psychiatry, which describes a psychotic syndrome in which “Negroes” have “antiwhite aggressive feelings” and “delusions [that] are clearly paranoid projections of racial antagonism of the Negroes to the Caucasian group” (41).

Relatedly, medical students were the reference group for this study’s training level analyses. However, medical students likely have less familiarity with psychiatric diagnosis and treatment compared to psychiatric physicians which may have biased the results towards the null and may be an alternative explanation of our findings related to training level. Therefore, future studies should consider having as a reference group of medical students with a strong interest in psychiatry (e.g. 4th year medical students who are actively applying to psychiatry residencies) given that medical students who choose to pursue a career in psychiatry may be more familiar with psychiatric terms, or alternatively assess more directly familiarity with words and control this in the analyses. Additional studies should also examine implicit racial associations longitudinally throughout medical training to understand how these biases develop. Overall, the results of this study suggest that that psychiatric training may specifically influence racial implicit associations related to psychiatric diagnosis and treatment but not all racial implicit associations, and that racial implicit associations may be pliable during and after psychiatric training.

Other researchers also suggests that implicit associations are malleable and can be changed or buffered with deliberate effort (42). There is an increasing interest and a number of curricula that attempt to address health disparities and cultural competence in medical school, psychiatric training, and continuing education for board-certified clinicians using the IAT (43, 44). For example, a 12-week intervention, using a multi-faceted prejudice habit-breaking intervention in undergraduate students demonstrated a reduction in racial implicit bias using the IAT (45). However, few curricula have been rigorously studied using systematic assessment of implicit associations, and evidence-based interventions are urgently needed in the medical field across levels of training and specialties, including psychiatry. Besides using the IAT to measure the success of an educational activity, medical educators have also used the IAT as a tool to promote self-awareness, discussion, and reflection in individuals (46). Understanding the mechanisms and factors associated with racial implicit associations may aid in developing and implementing successful programs to reduce healthcare disparities in psychiatry (47–49).

There are several limitations to this study. First, this study did not examine the effect of implicit racial associations on actual provider behavior in terms of diagnosis, treatment and medication prescription. Therefore, future studies should examine whether these measurable implicit racial associations are associated with the actual care provided by mental health practitioners. Literature in other specialties suggests that IAT scores are related to physician behavior, and these studies are appraised by two recent systematic reviews (16, 26). For example, IAT scores have been associated with patient ratings of real-life provider-patient interactions (16, 26), outcomes in spinal cord patients (50), simulated provider-patient encounters (51), and treatment decisions in vignette studies (37, 52). Importantly, not all vignette studies have shown effects of IAT on medical decision making (16, 26). Although more studies are needed to understand how the IAT relates to physician behavior, there is growing evidence that IAT scores are associated with differential interactions, treatment decisions, patient treatment adherence, and patient health outcomes using vignette studies, standardized patients, and actual patient encounters.

Additionally, although we have a modest sample size with a diverse ethnic-racial background, most participants were trainees, and we had a limited number of board-certified psychiatrists. Our sample was skewed towards younger individuals. This may have contributed to not finding a significant relationship between age and racial implicit associations scores, which has been observed in other specialties. Alternatively, it remains quite possible that the relationship between age and racial implicit associations is non-linear and that the effects of changes in training and society may have fairly discrete effects at specific times.

Furthermore, this is a convenience sample recruited primarily at academic meetings and by contacting academic training institutions, with recruitment materials that included the purpose of the study. Thus, our sample may have been biased towards individuals who are interested in healthcare disparities and/or curious about their implicit associations. Our sample is, therefore, not be representative of all mental health practitioners in the US, and future studies should consider investigating other practitioner subgroups in the US and abroad.

From the methodological perspective, we utilized the IAT D-score as our primary outcome in this study. The IAT has certain advantages including systematically assessing for implicit associations based on latency of responses and response errors. However, some researchers have questioned whether IAT scores are truly representative of bias and whether IAT scores necessarily indicate discriminatory behavior (53, 54). However, many studies support the test-retest reliability, construct validity, and criterion validity of the IAT procedure(55–58). Specific to this study, this is the first time the IAT has been modified to include psychiatric diagnosis and medication words, and thus our psychiatric IAT requires psychometric assessment. Finally, we conducted three IAT tasks and investigated multiple hypothesized demographic predictors within IAT tasks without correcting for multiple comparisons; therefore, our findings require replication. Despite these shortcomings, our study is a step towards improved understanding of racial implicit associations in psychiatry. Overall, implicit bias is a difficult concept to evaluate, and unfortunately, the field currently has limited ways to assess for bias at this time, be this implicit or explicit.

In conclusion, the implicit associations observed in this study (pairing Black faces with psychosis, antipsychotics, and noncompliance) are consistent with the known healthcare disparities in psychiatric diagnosis and treatment of Black individuals in the United States. Our results suggest that racial implicit associations may be a contributing factor in mental healthcare disparities. However, implicit associations provide only one possible avenue to address healthcare disparities and should be taken in the context of other contributors to disparities including systemic and structural racism in healthcare. Both implicit associations and systemic and structural racism appear to work synergistically to increase disparities and both must be addressed to decrease inequities in psychiatry. Future research should examine (1) the role of racial implicit associations in a more generalizable sample, (2) the relationship between race IATs and provider diagnostic, treatment and prescribing behaviors, and (3) whether there are interventions that may reduce provider racial implicit associations or the impact of provider implicit associations on clinical behavior among mental health providers.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the following faculty and trainees who reviewed the pilots for this project: Dr. Robert Rohrbaugh, Dr. Kali Cyrus, Dr. Esperanza Diaz, and Dr. Laine Taylor. We would also like to thank Dr. Nix Zelin, Caroline Scott, and Dr. Roberto Montenegro for their support in recruitment.

Funding

Financial support for this project was provided by the American Psychiatric Association Minority Fellowship Program sponsored by SAMHSA that was awarded to A.L.T and J.H.T. Racial Implicit Associations in Psychiatric Diagnosis, Treatment, and Compliance Expectations

Disclosure

A.LT. is supported by NIMH (5T32MH018268-34), the Ariella Ritvo grant. M.H.B. receives research support from Therapix Biosciences, Neurocrine Biosciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, but received no support from these sources for the current manuscript. M.H.B. gratefully acknowledges additional research support from NIH. J.H.T is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the NIH (KL2TR001879) and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. Mr. Johnson is supported by the Yale School of Medicine Medical Student Research Fellowship. Dr. Flores receives financial support for his research from NIH training grant T32MH018268. Dr. Landeros-Wisenberger, Dr. Avila-Quintero, Mr. Johnson and Mr. Aboiralor report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Lin M-Y; Kressin NR. Race/ethnicity and Americans’ experiences with treatment decision making. Patient education and counseling. 2015;98(12):1636–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elster A; Jarosik J; VanGeest J; Fleming M. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care for adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2003;157(9):867–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saha S; Freeman M; Toure J; Tippens KM; Weeks C; Ibrahim S. Racial and ethnic disparities in the VA health care system: a systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(5):654–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson A Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2002;94(8):666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meghani SH; Byun E; Gallagher RM. Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Medicine. 2012;13(2):150–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Ryn M; Burgess D; Malat J; Griffin J. Physicians’ perceptions of patients’ social and behavioral characteristics and race disparities in treatment recommendations for men with coronary artery disease. American journal of public health. 2006;96(2):351–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sequist TD; Fitzmaurice GM; Marshall R; Shaykevich S; Safran DG; Ayanian JZ. Physician performance and racial disparities in diabetes mellitus care. Archives of internal medicine. 2008;168(11):1145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein AM; Ayanian JZ; Keogh JH; Noonan SJ; Armistead N; Cleary PD, et al. Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation—clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343(21):1537–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco C; Patel SR; Liu L; Jiang H; Lewis-Fernández R; Schmidt AB, et al. National trends in ethnic disparities in mental health care. Medical care. 2007;45(11):1012–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kristofco RE; Stewart AJ; Vega W. Perspectives on disparities in depression care. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2007;27(S1):18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services. Rockville, MD. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chien PL; Bell CC. Racial differences in schizophrenia. Directions in Psychiatry. 2008;28(4):297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz RC; Blankenship DM. Racial disparities in psychotic disorder diagnosis: A review of empirical literature. World journal of Psychiatry. 2014;4(4):133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnes A. Race and hospital diagnoses of schizophrenia and mood disorders. Social Work. 2008;53(1):77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neighbors HW; Jackson JS; Campbell L; Williams D. The influence of racial factors on psychiatric diagnosis: A review and suggestions for research. Community Mental Health Journal. 1989;25(4):301–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall WJ; Chapman MV; Lee KM; Merino YM; Thomas TW; Payne BK, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. American journal of public health. 2015;105(12):e60–e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eack SM; Bahorik AL; Newhill CE; Neighbors HW; Davis LE. Interviewer-perceived honesty as a mediator of racial disparities in the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(9):875–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neighbors HW; Trierweiler SJ; Munday C; Thompson EE; Jackson JS; Binion VJ, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis of African Americans: diagnostic divergence in clinician-structured and semistructured interviewing conditions. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1999;91(11):601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neighbors HW; Trierweiler SJ; Ford BC; Muroff JR. Racial differences in DSM diagnosis using a semi-structured instrument: The importance of clinical judgment in the diagnosis of African Americans. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003:237–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nosek BA; Smyth FL. A multitrait-multimethod validation of the implicit association test. Experimental psychology. 2007;54(1):14–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gawronski B; De Houwer J. Implicit measures in social and personality psychology. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paradies Y; Truong M; Priest N. A systematic review of the extent and measurement of healthcare provider racism. Journal of general internal medicine. 2014;29(2):364–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabin J; Nosek BA; Greenwald A; Rivara FP. Physicians’ implicit and explicit attitudes about race by MD race, ethnicity, and gender. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):896–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haider AH; Sexton J; Sriram N; Cooper LA; Efron DT; Swoboda S, et al. Association of unconscious race and social class bias with vignette-based clinical assessments by medical students. Jama. 2011;306(9):942–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haider AH; Schneider EB; Sriram N; Dossick DS; Scott VK; Swoboda SM, et al. Unconscious race and class bias: its association with decision making by trauma and acute care surgeons. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2014;77(3):409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maina IW; Belton TD; Ginzberg S; Singh A; Johnson TJ. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Social Science & Medicine. 2018;199:219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenwald AG; Nosek BA; Banaji MR. Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2003;85(2):197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nosek BA; Greenwald AG; Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: II. Method variables and construct validity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31(2):166–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenwald AG; Poehlman TA; Uhlmann EL; Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2009;97(1):17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmukle SC; Egloff B. Does the Implicit Association Test for assessing anxiety measure trait and state variance? European Journal of Personality. 2004;18(6):483–94. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenwald AG; Nosek BA. Health of the Implicit Association Test at age 3. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nosek BA; Greenwald AG; Banaji MR. The Implicit Association Test at age 7: A methodological and conceptual review. Automatic processes in social thinking and behavior. 2007;4:265–92. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lane KA; Banaji MR; Nosek BA; Greenwald AG. Understanding and using the implicit association test: IV. Implicit measures of attitudes. 2007:59–102. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiedler K; Bluemke M. Faking the IAT: Aided and unaided response control on the Implicit Association Tests. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2005;27(4):307–16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim D-Y. Voluntary controllability of the implicit association test (IAT). Social Psychology Quarterly. 2003:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper LA; Roter DL; Carson KA; Beach MC; Sabin JA; Greenwald AG, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. American journal of public health. 2012;102(5):979–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabin JA; Greenwald AG. The influence of implicit bias on treatment recommendations for 4 common pediatric conditions: pain, urinary tract infection, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and asthma. American journal of public health. 2012;102(5):988–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sabin DJA; Nosek DBA; Greenwald DAG; Rivara DFP. Physicians’ implicit and explicit attitudes about race by MD race, ethnicity, and gender. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2009;20(3):896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen BJ; Garg K. Diversity matters in academic radiology: acknowledging and addressing unconscious bias. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2016;13(12):1426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lokko HN; Chen JA; Parekh RI; Stern TA. Racial and ethnic diversity in the US psychiatric workforce: a perspective and recommendations. Academic Psychiatry. 2016;40(6):898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Metzl JM. The protest psychosis: How schizophrenia became a black disease: Beacon Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blair IV. The malleability of automatic stereotypes and prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6(3):242–61. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aggarwal NK; Lam P; Castillo EG; Weiss; Diaz E; Alarcón RD, et al. How do clinicians prefer cultural competence training? Findings from the DSM-5 cultural formulation interview field trial. Academic Psychiatry. 2016;40(4):584–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mian AI; Al-Mateen CS; Cerda G. Training child and adolescent psychiatrists to be culturally competent. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics. 2010;19(4):815–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Devine PG; Forscher PS; Austin AJ; Cox WT. Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of experimental social psychology. 2012;48(6):1267–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sukhera J; Wodzinski M; Rehman M; Gonzalez CM. The Implicit Association Test in health professions education: A meta-narrative review. Perspectives on medical education. 2019:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amodio DM. The neuroscience of prejudice and stereotyping. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2014;15(10):670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bromberg W; Simon F. The protest psychosis: a special type of reactive psychosis. Archives of general psychiatry. 1968;19(2):155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Metzl J Controllin the Planet: a brief history of schizophrenia. Transition. 2014;115(1):23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hausmann LR; Myaskovsky L; Niyonkuru C; Oyster ML; Switzer GE; Burkitt KH, et al. Examining implicit bias of physicians who care for individuals with spinal cord injury: A pilot study and future directions. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2015;38(1):102–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schaa KL; Roter DL; Biesecker BB; Cooper LA; Erby LH. Genetic counselors’ implicit racial attitudes and their relationship to communication. Health Psychology. 2015;34(2):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green AR; Carney DR; Pallin DJ; Ngo LH; Raymond KL; Iezzoni LI, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. Journal of general internal medicine. 2007;22(9):1231–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arkes HR; Tetlock PE. Attributions of implicit prejudice, or” would Jesse Jackson’fail’the Implicit Association Test?”. Psychological inquiry. 2004;15(4):257–78. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Landy FJ. Stereotypes, bias, and personnel decisions: Strange and stranger. Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2008;1(4):379–92. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rezaei AR. Validity and reliability of the IAT: Measuring gender and ethnic stereotypes. Computers in human behavior. 2011;27(5):1937–41. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blanton H; Jaccard J. Arbitrary metrics in psychology. American Psychologist. 2006;61(1):27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oswald FL; Mitchell G; Blanton H; Jaccard J; Tetlock PE. Predicting ethnic and racial discrimination: a meta-analysis of IAT criterion studies. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2013;105(2):171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blanton H; Jaccard J; Klick J; Mellers B; Mitchell G; Tetlock PE. Strong claims and weak evidence: Reassessing the predictive validity of the IAT. Journal of applied Psychology. 2009;94(3):567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]