Abstract

Clinical outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is associated with cytogenetic and molecular factors and patient demographics (e.g., age and race). We compared survival of 25,523 Non-Hispanic Black and White adults with AML using Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program data, and performed mutational profiling of 1,339 AML patients treated on frontline Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology (Alliance) protocols. Black patients had shorter survival than White patients, both in SEER and in the setting of Alliance clinical trials. The disparity was especially pronounced in Black patients <60 years, after adjustment for socioeconomic (SEER) and molecular (Alliance) factors. Black race was an independent prognosticator of poor survival. Gene mutation profiles showed fewer NPM1 and more IDH2 mutations in younger Black patients. Overall survival of younger Black patients was adversely affected by IDH2 mutations and FLT3-ITD, but, in contrast to White patients, was not improved by NPM1 mutations.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, Black race, clinical outcome, survival disparity, gene mutations

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 20,000 adults in the United States are diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) each year, rendering it the most common acute leukemia in adults [Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 9 Regs Research Data, Nov 2018 Sub (1975–2016) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969–2017 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released April 2019, based on the November 2018 submission; ref. 1]. AML is a clonal disorder of hematopoiesis characterized by genetic and epigenetic alterations leading to a block in differentiation of myeloid progenitors and accumulation of leukemic blasts in the bone marrow (BM) and blood (2,3). Overall survival for AML patients remains poor as approximately 20% to 30% of patients never achieve complete remission (CR) following intensive frontline treatment and 50% of patients relapse following achievement of CR, typically within 2 or 3 years after diagnosis (3,4). A number of pretreatment factors, both disease- and patient-specific, affect prognosis. The former include cytogenetic findings at diagnosis (5–8) and select gene mutations (9–16). Among the patient-specific characteristics, older age at diagnosis, typically defined as ≥60 years, is a well-recognized independent predictor of worse survival (17), and several studies have demonstrated Black race to be associated with worse survival (18–21). This is in line with cancer outcomes in other malignancies, where Black patients consistently fare worse than White patients (22–26).

The roles of socioeconomic factors (27–29) and cytogenetic findings (using standard karyotyping; ref. 21) in creating survival disparities between the Black and White patients with AML have been examined previously. However, to our knowledge, neither the mutational landscape of Black AML patients nor the impact of gene mutations on their outcomes have been rigorously studied.

In this study, we first conducted a population based analysis of AML patients using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute to determine the influence of age and other socioeconomic factors on survival disparities between Non-Hispanic Black and Non-Hispanic White (hereafter referred to as Black and White, respectively) adults with AML. Moreover, given the importance of genetic features (6–16), we have also assessed the impact of pretreatment cytogenetic and molecular features on outcomes of AML patients treated on Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB)/Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology (Alliance) protocols with respect to self-reported race.

RESULTS

Survival of Black and White AML Patients Included in SEER Registries and the Impact of Socioeconomic Features

The collection of SEER registries contained 9,430 patients younger than 60 years and 16,093 patients aged ≥60 years diagnosed with AML. Because younger patients typically receive more intensive chemotherapy than older patients, we performed all outcome analyses separately for each age group.

The cohort of younger patients was comprised of 1,356 Black and 8,074 White patients. Their demographic and socioeconomic features are shown in Table 1. Black patients were younger at diagnosis than Whites (median age, 45 vs. 48 years; P<0.001). A higher percentage of Black patients resided in metropolitan areas (94% vs. 88%, P<0.001) and their family income was below the poverty level more often than White patients (13% vs. 8%, P<0.001).

Table 1.

Pretreatment characteristics of younger (<60 years) and older (≥60 years) non-Hispanic Black and White patients diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) included in SEER registries in 1986–2015

| Characteristic | Younger patients | Older patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black n=1,356 |

White n=8,074 |

Pa | Black n=1,258 |

White n=14,835 |

Pa | |

| Age, years | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Median | 45 | 48 | 72 | 73 | ||

| Range | 18–59 | 18–59 | 60–85 | 60–85 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | 0.09 | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 700 (52) | 4,368 (54) | 609 (48) | 8,394 (57) | ||

| Female | 656 (48) | 3,706 (46) | 649 (52) | 6,441 (43) | ||

| Metro, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 1,272 (94) | 7,124 (88) | 1,170 (93) | 12,849 (87) | ||

| No | 84 (6) | 950 (12) | 88 (7) | 1986 (13) | ||

| Insurance, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Insured | 375 (28) | 2,604 (32) | 466 (37) | 5,596 (38) | ||

| Any Medicaid | 218 (16) | 527 (7) | 104 (8) | 340 (2) | ||

| Uninsured | 58 (4) | 130 (2) | 13 (1) | 67 (0.5) | ||

| Insurance status unknown | 705 (52) | 4,813 (60) | 675 (54) | 8,832 (59.5) | ||

| Percent of families below poverty level | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Median | 13% | 8% | 13% | 9% | ||

| Range | 3%−42% | 2%−37% | 2%−31% | 2%−42% | ||

| Year of diagnosis, n (%) | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||||

| 1986–1995 | 160 (12) | 1,365 (17) | 164 (13) | 2,335 (16) | ||

| 1996–2005 | 480 (35) | 2,994 (37) | 439 (35) | 5,478 (37) | ||

| 2006–2015 | 716 (53) | 3,715 (46) | 655 (52) | 7,022 (47) | ||

P-values for categorical variables are from Fisher’s exact test, P-values for continuous variables are from the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

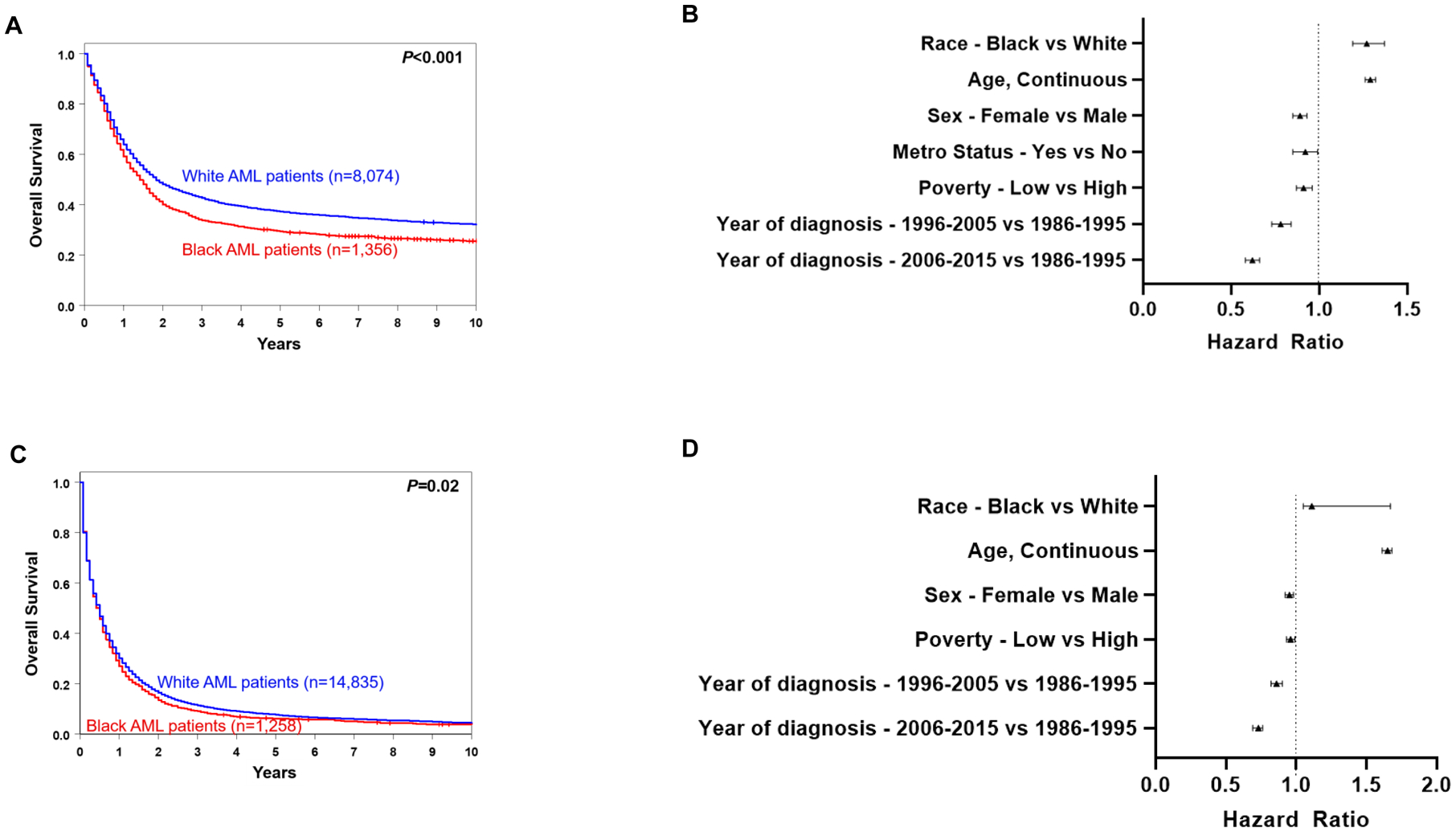

Compared with younger White AML patients, Black patients had a significantly shorter overall survival (OS; 3-year rates, 34% vs. 43%, P<0.001; Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 1A). In multivariable analyses for OS of younger AML patients, Black patients were found to have a 27% higher risk of death compared with White patients (P<0.001; Supplementary Table 2) after adjustment for age, sex, metropolitan area residential status, measure of poverty and decade of diagnosis (Fig. 1B). Survival of younger AML patients generally improved over time (Supplementary Fig. 1A). However, although the OS of Black and White patients was not significantly different among patients diagnosed between 1986 and 1995 (P=0.19; Supplementary Fig. 1B), in the two decades since then the OS of Black patients became significantly shorter compared with OS of White patients (Supplementary Fig. 1C and 1D).

Figure 1.

Treatment outcome of non-Hispanic Black and White patients with AML in SEER registries. A, overall survival of patients aged <60 years. B, forest plot illustrating multivariable analyses of survival of patients aged <60 years. C, overall survival of patients aged ≥60 years. D, forest plot illustrating multivariable analyses of survival of patients aged ≥60 years.

The cohort of older patients included 1,258 Black and 14,835 White patients (Table 1). Survival of older Black AML patients was also worse compared to older White patients, with 3-year OS rates of 9% and 11%, respectively (P=0.02; Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 1C). While this finding is consistent with the generally poor survival of older AML patients, the difference in outcome was less pronounced than in younger patients. Multivariable analyses revealed a higher risk of death for Black patients than White patients (HR 1.11, P<0.001) once adjusted for age, sex, measure of poverty and decade of diagnosis (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Table 3). Similar to younger patients, the outcomes of older patients also improved over time (Supplementary Fig. 2A to 2D).

Clinical and Molecular Characteristics of AML Patients Treated on CALGB/Alliance Protocols with Respect to Self-Reported Race

Clinically, there were only few differences in pretreatment features, with Black AML patients under the age of 60 tending to be younger than White patients (median age, 41 vs. 46 years, P=0.06, Table 2). Among patients aged 60 years and older, Black patients had higher percentages of BM blasts (79% vs. 66%, P=0.03) and did not present with extramedullary involvement (0% vs. 23%, P=0.01).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of younger (<60 years) and older (≥60 years) Black and White patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated on the CALGB/Alliance study protocols

| Characteristic | Younger patients | Older patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black n=72 |

White n=777 |

Pa | Black n=23 |

White n=467 |

Pa | |

| Age, years | 0.06 | 0.54 | ||||

| Median | 41 | 46 | 69 | 70 | ||

| Range | 20–59 | 17–59 | 62–92 | 60–89 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | 0.81 | 0.40 | ||||

| Male | 38 (53) | 424 (55) | 11 (48) | 267 (57) | ||

| Female | 34 (47) | 353 (45) | 12 (52) | 200 (43) | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 0.09 | 0.19 | ||||

| Median | 8.6 | 9.2 | 9.1 | 9.3 | ||

| Range | 2.3–13.2 | 3.1–25.1 | 6.3–11.9 | 3.0–15.0 | ||

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 0.24 | 0.19 | ||||

| Median | 56 | 52 | 42 | 60 | ||

| Range | 16–279 | 4–648 | 5–426 | 4–989 | ||

| WBC count, ×109/L | 0.66 | 0.75 | ||||

| Median | 25.1 | 24.6 | 16.8 | 24.0 | ||

| Range | 0.4–308.8 | 0.6–560.0 | 1.4–155.9 | 0.4–450.0 | ||

| Blood blasts, % | 0.25 | 0.35 | ||||

| Median | 47 | 56 | 61 | 44 | ||

| Range | 0–98 | 0–99 | 4–91 | 0–99 | ||

| Bone marrow blasts, % | 0.95 | 0.03 | ||||

| Median | 64 | 65 | 79 | 66 | ||

| Range | 21–96 | 2–99 | 17–99 | 0–99 | ||

| Extramedullary involvement, n (%) | 17 (26) | 200 (27) | 1.00 | 0 (0) | 101 (23) | 0.01 |

| 2017 ELN risk group, n % | 0.27 | 0.13 | ||||

| Favorable | 29 (40) | 381 (49) | 5 (22) | 143 (31) | ||

| Intermediate | 16 (22) | 169 (22) | 3 (13) | 121 (26) | ||

| Adverse | 27 (38) | 227 (29) | 15 (65) | 203 (43) | ||

| Year of diagnosis | 0.60 | 0.84 | ||||

| 1986–1995 | 12 (17) | 103 (13) | 2 (9) | 60 (13) | ||

| 1996–2005 | 32 (44) | 382 (49) | 18 (78) | 324 (69) | ||

| 2005–2015 | 28 (39) | 292 (38) | 3 (13) | 83 (18) | ||

| Cytogenetic group, n (%) | 0.23 | 0.57 | ||||

| Normal karyotype | 27 (38) | 401 (52) | 9 (39) | 235 (50) | ||

| Complex karyotype | 8 (11) | 57 (7) | 6 (26) | 75 (16) | ||

| Typical | 4 | 40 | 2 | 58 | ||

| Atypical | 4 | 17 | 4 | 17 | ||

| CBF-AML | 13 (18) | 108 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| inv(16)(p13.1q22) | 7 | 71 | 0 | 0 | ||

| t(8;21)(q22;q22) | 6 | 37 | 0 | 0 | ||

| t(v;11)(v;q23) | 6 (8) | 44 (6) | 1 (4) | 15 (3) | ||

| Other balanced rearrangements | 6 (8) | 61 (8) | 1 (4) | 24 (5) | ||

| Unbalanced abnormalities in a | 12 (17) | 106 (14) | 6 (26) | 118 (25) | ||

| non-complex karyotype | ||||||

Abbreviations: ELN, European LeukemiaNet; n, number; WBC, white blood cell.

P-values for categorical variables are from Fisher’s exact test, P-values for continuous variables are from the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

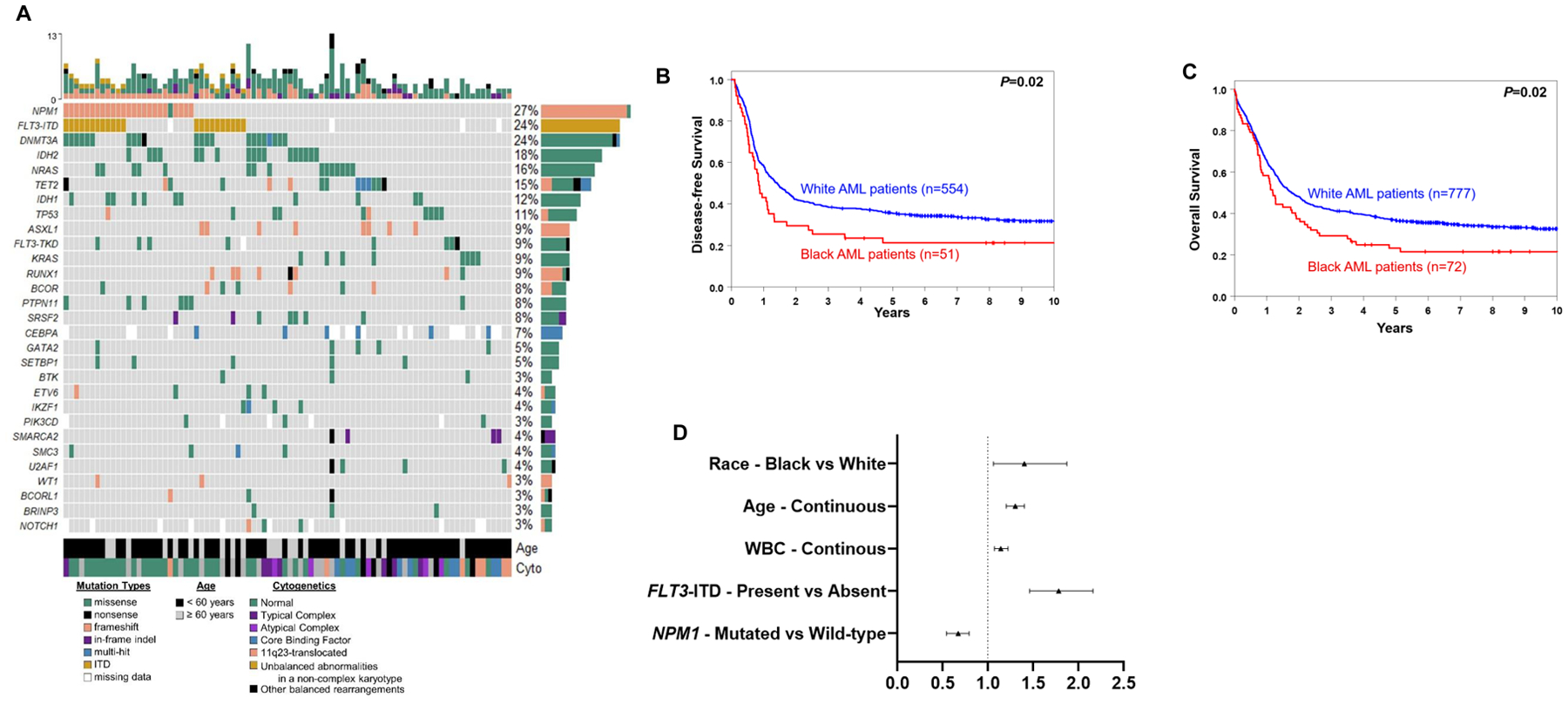

Mutational analysis demonstrated several molecular differences between Black and White patients in the younger age group, but not among older patients (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table 4). Among younger patients, NPM1 and WT1 mutations were less frequently detected in Black patients than in White patients (NPM1, 25% vs. 38%, P=0.04; WT1, 3% vs. 10%, P=0.05). In contrast, mutations in IDH2 (17% vs. 8%, P=0.03), and PIK3CD (4% vs. 1%, P=0.04) were more frequently detected in Black AML patients. Assignment to favorable, intermediate or adverse genetic-risk groups based on cytogenetic findings and selected gene mutation status, as defined by the 2017 European LeukemiaNet guidelines (2), did not differ significantly between races in either younger or older patients with AML (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Mutational landscape and clinical outcome of Black and White patients with AML aged <60 years who were treated on the CALGB/Alliance study protocols. A, oncoprint of gene mutations detected in Black patients. B, disease-free and C overall survival of younger Black and White patients. D, forest plot illustrating multivariable analyses of overall survival of patients aged <60 years.

Outcome of Younger Black and White AML Patients Treated on CALGB/Alliance Protocols

Patients aged <60 years enrolled onto CALGB/Alliance study protocols all received comparable, anthracycline-based induction therapy and no allogeneic stem-cell transplantation (allo-SCT) in first CR per protocol, allowing us to assess whether access to uniform treatment in the setting of clinical trials might abrogate the survival outcome differences. The CR rate for both Black and White patients was 71%, indicating identical response to intensive induction therapy. Additionally, death within the first 30 days of induction was also similar (10% vs. 6%, P=0.20; Table 3). However, survival of younger Black patients was worse, with 25% of Black AML patients disease-free and 29% alive 3 years after diagnosis, compared with, respectively, 38% and 42% of White patients [disease-free survival (DFS), P=0.02, Fig. 2B; OS, P=0.02, Fig. 2C). Relapse rates were also slightly higher in Black AML patients compared to White patients (71% vs. 59%, P=0.14). Of note, there was no significant difference in the number of consolidation cycles between Black and White AML patients (P=0.09).

Table 3.

Outcomes of younger (aged <60 years) Black and White acute myeloid leukemia patients treated on the CALGB/Alliance study protocols

| Outcome | Black patients n=72 |

White patients n=777 |

Pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early death | 7 (10) | 46 (6) | .20 |

| Complete remission | 51 (71) | 554 (71) | 1.00 |

| Relapse rate, n (%) | 36 (71) | 328 (59) | 0.14 |

| Disease-free survival | 0.02 | ||

| Median, years | 0.8 | 1.4 | |

| Disease-free at 3 years, % (95% CI) | 25 (15–38) | 38 (34–42) | |

| Overall survival | 0.02 | ||

| Median, years | 1.2 | 1.8 | |

| Alive at 3 years, % (95% CI) | 29 (19–40) | 42 (38–45) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

Note. The median number of cycles of consolidation chemotherapy was 2 (range, 1–4) for Black and 1 (range, 1–4) for White patients (P=0.09).

P-values for early death and complete remission are from Fisher’s exact test, P-values for the time to event variables are from the log-rank test and compare the two groups: black and white AML patients.

Next, we evaluated whether Black race impacted patient survival independent of other established risk factors. Indeed, in multivariable analyses of OS, Black race was associated with worse OS compared with White race, with Black patients having a 40% higher likelihood of death compared with White patients (P=0.02), after adjustment for white blood cell count, age, internal tandem duplication of the FLT3 gene (FLT3-ITD) and NPM1 mutation status (Fig. 2D, Supplementary Table 5). In multivariable analyses for CR achievement and DFS, race did not remain in the models.

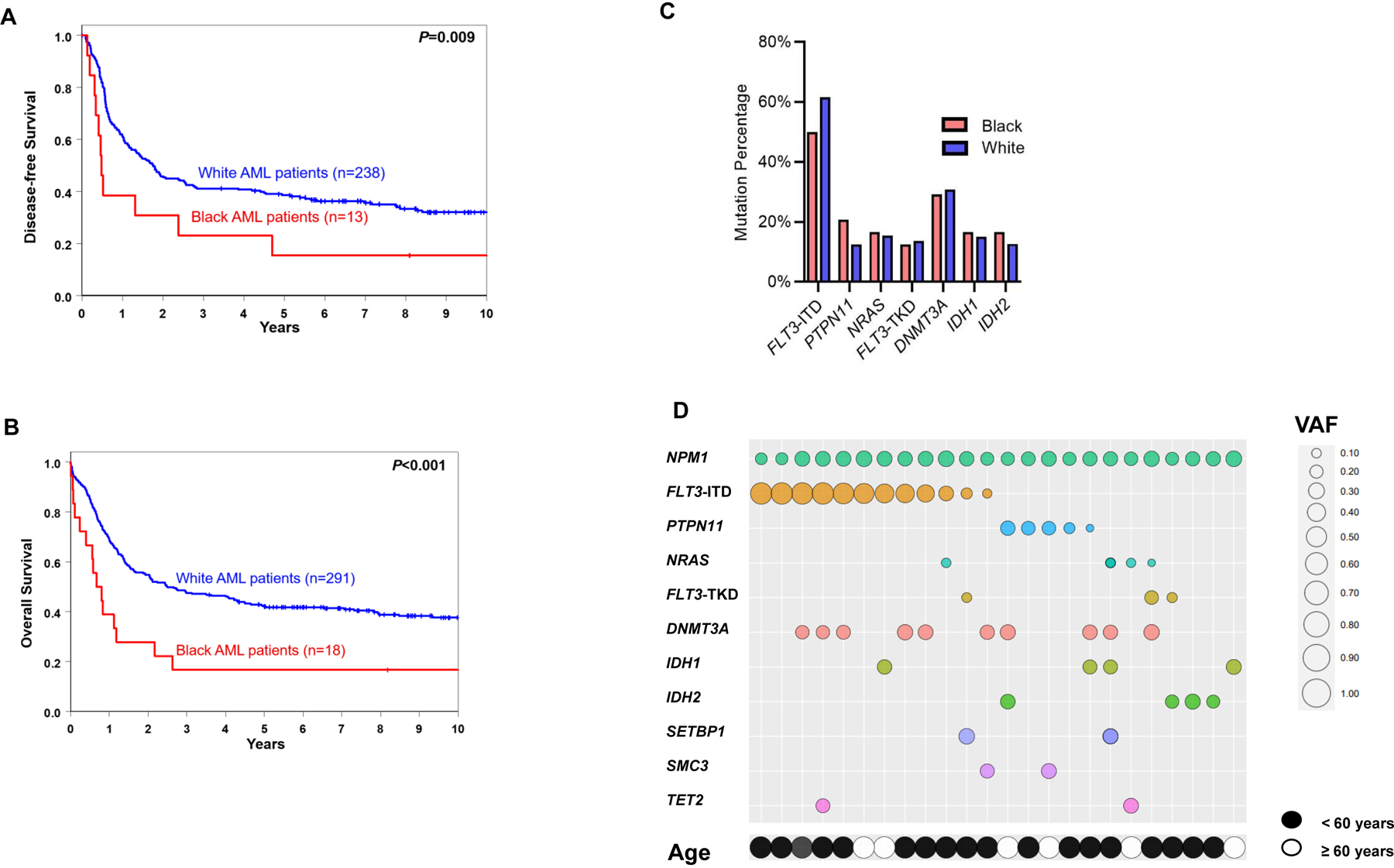

Outcome of Younger Black and White AML Patients Treated on CALGB/Alliance Protocols in the NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITDlow/no Molecular Low-Risk Group

Notably, the survival disparity of Black AML patients was especially pronounced in patients harboring NPM1 mutations, the presence of which, without a concurrent FLT3-ITD with high allelic ratio, confers a good prognosis in AML patients. Whereas the 3-year DFS and OS rates of NPM1-mutated White AML patients were 41% and 47%, respectively, they were only 23% (P=0.009) and 17% (P<0.001) in Black AML patients (Fig. 3A and B). As co-existing mutations are known to modify the impact of NPM1 mutations on patient survival (14), we assessed the frequencies of co-occurring mutations in Black and White NPM1-mutated patients (Fig. 3C) as well as the mutations’ variant allele fractions in Black AML patients (Fig. 3D). Assessment of NPM1-co-occurring mutations did not reveal any noticeable differences in the frequencies between Black and White patients, at least with respect to known recurrent AML-associated variants.

Figure 3.

Treatment outcome of Black and White patients with AML aged <60 years who were treated on the CALGB/Alliance study protocols. A, disease-free and B, overall survival within NPM1-mutated of Black and White patients. C, bar graph depicting frequencies of mutations co-existing with NPM1 mutation in Black and White patients with AML. D, a bubble plot with co-occurring mutations and associated variant allele frequencies (VAF) observed in NPM1-mutated Black AML patients treated on CALGB/Alliance studies. Increased bubble sizes indicate higher VAFs/allelic ratio (for FLT3-ITD). Each column refers to one individual patient.

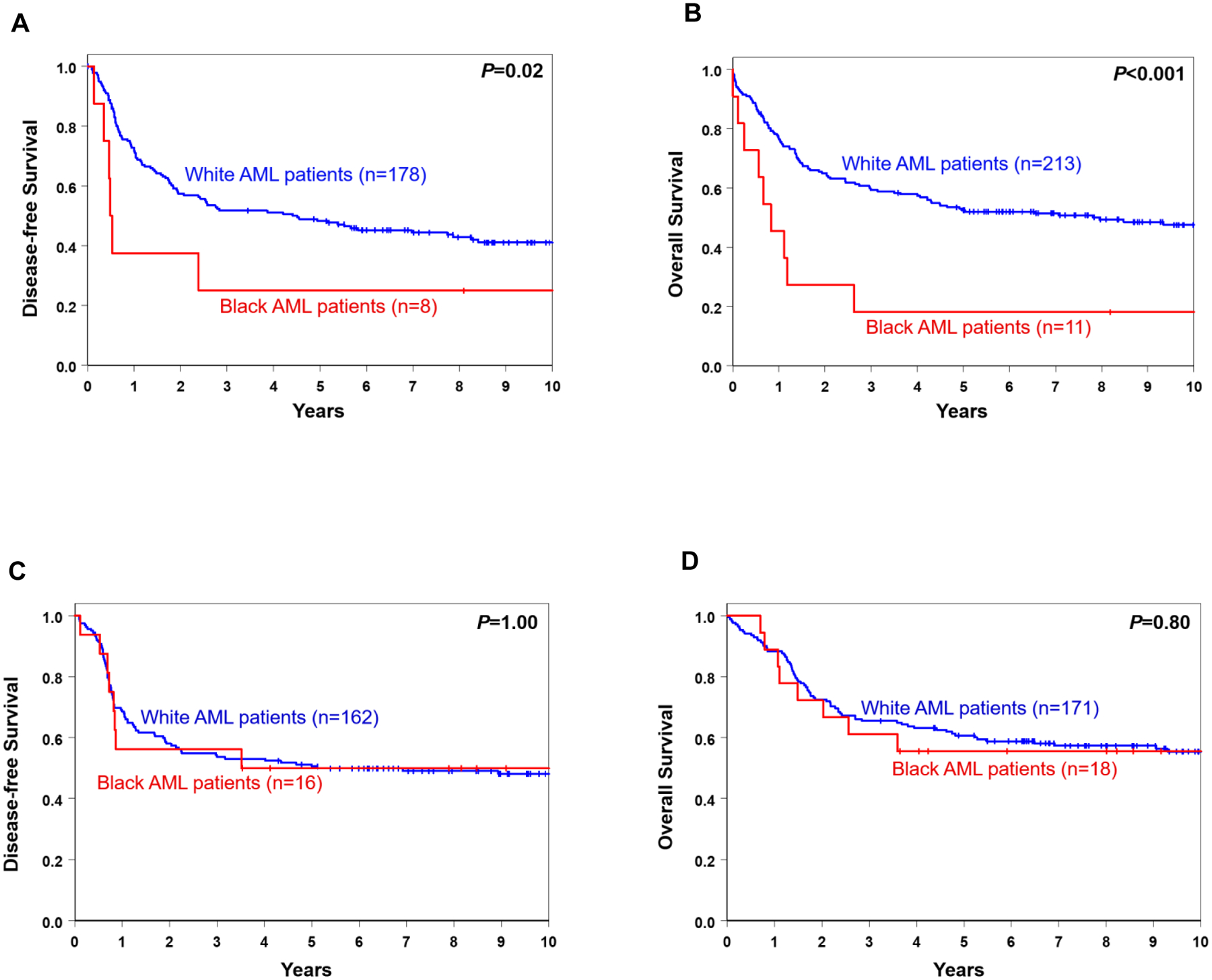

Because the presence or absence of a high allelic ratio of FLT3-ITD alters the favorable prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations, we compared the survival of Black and White patients with NPM1 mutations and no or low allelic ratio FLT3-ITD (FLT3-ITDlow/no), who comprise the majority of favorable-risk AML patients (64%). Although sample sizes were small, Black NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITDlow/no patients had substantially poorer survival compared to White NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITDlow/no patients (Fig. 4A and 4B). Given the poor survival of Black NPM1-mutated AML patients included in the 2017 European LeukemiaNet (ELN; ref. 1) favorable-risk group, we next analyzed the outcomes of the non-NPM1-mutated patients classified as 2017 ELN favorable-risk [i.e., patients with biallelic CEBPA mutations and those with inv(16)(p13.1q22) or t(8;21)(q22;q22)]. We found no significant difference in the survival between Black and White patients in this non-NPM1-mutated 2017 ELN favorable-risk subset, suggesting that the disparity between Black and White patients is specific to the NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITDlow/no patients (Fig. 4C and 4D). Similarly, there were no significant differences in the survival of Black and White AML patients belonging to the 2017 ELN intermediate- or adverse-risk groups (Supplementary Figs. 3A–D).

Figure 4.

Survival of Black and White AML patients aged ≤60 years who were treated on Alliance protocols and classified into the 2017 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) favorable genetic-risk group. A, disease-free and B, overall survival of NPM1-mutated patients. C, disease-free and D, overall survival of non-NPM1-mutated patients [i.e., patients with biallelic CEBPA mutations or those harboring inv(16)(p13.1q22) or t(8;21)(q22;q22)].

Impact of Molecular Features on the Outcome of Younger Black AML Patients

To identify clinical and molecular features that impact the outcome of Black AML patients, we performed univariable and multivariable outcome analyses in the CALGB/Alliance cohort of younger Black patients. These analyses did not identify any molecular features associated with achievement of CR or DFS. However, Black patients harboring FLT3-ITD or IDH2 mutations had a higher risk of death than Black patients without these mutations in multivariable analysis (FLT3-ITD, HR=1.95, P=0.03; IDH2, HR=2.17, P=0.008; Supplementary Table 6). There were no significant differences in DFS or OS between Black NPM1-mutated and NPM1 wild-type patients (Supplementary Fig. 4A and 4B). In fact, Black patients with NPM1 mutations tended to have a shorter OS than those with wild-type NPM1 alleles (P=0.08).

DISCUSSION

Over the past two decades, the biologic underpinnings of AML have become better defined with the discovery of recurrent molecular abnormalities. The subsequent use of next-generation sequencing to better stratify patients according to their genetic risk based on pretreatment cytogenetic and molecular characteristics can aid in treatment selection. Recently, remission rates and survival have improved, especially for younger AML patients. However, these advances have not helped to address survival disparities between Black and White AML patients. Socioeconomic disparities and structural racism have been previously identified as major contributors to poor outcomes of Black patients diagnosed with AML and for Black patients suffering from other malignancies (19,29–31). Although differences in mutation patterns between Black and White patients with other malignancies have been reported (22–26,32), our study is, to our knowledge, the largest to comprehensively evaluate the mutational landscapes of Black and White patients with AML, with respect to both frequencies of specific mutations and their impact on patient survival. This suggests that molecular features may constitute a, thus far, underappreciated factor potentially influencing survival disparities between Black and White AML patients.

The SEER registry data we present herein show that overall survival of both younger and older Black patients is significantly shorter than survival of White patients, and, for younger patients only, the outcome disparity, which was observed during 1996–2005 was more accentuated during the most recent 2006–2015 timeframe. This indicates that Black AML patients have not benefitted from recent advances to the same degree as White patients. Younger Black patients under the age of 60 years had a 27% higher risk of dying compared with White patients, which is even higher than previous studies (20). Given a greater proportion of Black families with income below poverty levels and a higher percentage of Black patients having Medicaid health insurance, which could affect access to and compliance with medical care, these results support the contribution of demographic and socioeconomic factors to the survival disparity. As SEER data do not provide information about treatment received by the patients, including the availability of salvage therapies or supportive care. Consequently, the reasons for the recent survival improvement in White AML patients (and the lack thereof in Black AML patients) cannot be fully elucidated by the SEER analyses.

Our analyses of the Alliance data, however, which depict the survival outcomes of AML patients enrolled in clinical trials of CALGB/Alliance over the past three decades, demonstrate inferior survival of Black patients even in the setting of clinical trials and provide further clues about contributing factors to the observed, persistent survival disparities. Despite similar consolidation therapies, the reduced DFS and OS suggest a contribution of differences in disease biology to further impact on the poor outcomes, in addition to differences in socioeconomic factors.

Indeed, our data show that Black patients harbored NPM1 mutations less frequently than White patients and NPM1-mutated Black patients had significantly worse OS than NPM1-mutated White patients. Because younger NPM1-mutated patients (in the absence of FLT3-ITD) who achieve clearance of the NPM1 mutation during remission are usually not considered for more intensive treatment such as allo-SCT (33), these risk discrepancies have additional implications for Black AML patients. Notably, we found no significant differences in the survival of Black and White AML patients belonging to the non-NPM1-mutated 2017 ELN favorable-risk group, nor did we find significant survival differences between Black and White AML patients classified in the intermediate- or adverse-risk groups. Thus, the poorer outcomes of Black AML patients may be driven, at least in part, by the poor survival of the NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITDlow/no patients. Although, given the relatively small patient numbers, follow-up studies are necessary to validate these findings, our data may indicate the need for additional or different consolidation treatment in this specific patient cohort.

The lower frequency of mutations in NPM1 and WT1, and the higher frequency of mutations in clonal hematopoiesis-associated genes such as IDH2 in Black AML patients suggest differences in the genetic basis of the disease. Additionally, the higher frequency of IDH2 mutations observed in Black patients is especially relevant given the recent approval of targeted IDH2 inhibitor therapy for relapsed/refractory IDH2-mutated AML (34), and ongoing studies demonstrating potential of IDH2 inhibitors to improve response rates in the frontline setting as well (35).

A few studies that examined racial disparities by assessing differences in treatment approaches, found that Black patients were less likely to receive intensive chemotherapy or allo-SCT compared with White patients (19,36). However, because the patients included in the CALGB/Alliance studies received similar treatment and did not, per protocol, undergo allo-SCT in first complete remission, differences in treatment and consolidation intensities cannot fully explain the disparity found in our study. This is further supported by the poor outcomes of Black as compared with White patients in the group of NPM1-mutated/ FLT3-ITDlow/no patients, who are not routinely offered allo-SCT in first complete remission. Other potential reasons for the outcome disparity that merit further evaluation include patient-associated factors such as co-morbidities and pre-treatment performance status, and additional disease-specific features such as potential influence of novel mutations in genes not included in the gene-panel used in this study. Possible differences in follow-up care between Black and White patients that were not assessed in this study should also be considered for future disparities work.

In summary, our study shows that survival disparities for Black AML patients persist even in the era of improved understanding of the disease and refined genomic classification of AML. This is particularly noticeable for younger patients, who, in general, have a higher chance of cure. Given the observed differences in gene mutation profiles and the associations between specific gene mutations and outcome, it is imperative that both socioeconomic factors and differences in disease biology are taken into account in order to more appropriately tailor the care of Black AML patients and, ultimately, resolve this survival disparity.

METHODS

Patients and Treatment

We used the SEER Program of the National Cancer Institute to identify 25,523 adults aged ≥18 years diagnosed with AML (excluding acute promyelocytic leukemia) between 1986 and 2015 and included in one of nine SEER registries (www.seer.cancer.gov). We removed all duplicate patients and subset on patients with AML as their only or first primary disease. All patients with possible treatment-related AML or AML associated with Down syndrome were also excluded. Demographic (e.g., age, sex, self-reported race) and clinical (e.g., survival, year of diagnosis) information and insurance status were obtained from SEER, as was metropolitan/non-metropolitan county residence and a county-level variable indicating poverty level (see Supplementary Data for further details).

We also analyzed 1,339 adult AML patients (including 95 self-reported Black and 1,244 White) who were treated on frontline CALGB/Alliance protocols. Almost all of these patients received intensive cytarabine and daunorubicin or idarubicin-based induction treatment on CALGB/Alliance trials between 1986 and 2015. Details regarding these trials are provided in the Supplementary Data. No patient received allo-SCT in first CR on study protocols, and off-study patients who received an allo-SCT in first CR were excluded from the outcome analyses due to missing follow up data.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval of all CALGB/Alliance protocols, and IRB exemption for SEER data analyses, were obtained before any research was performed. Patients provided study-specific written informed consent to participate in treatment studies (Supplementary Data), and companion studies CALGB 8461 (cytogenetic studies; Trial Registration Number: NCT00048958), CALGB 9665 (leukemia tissue bank; NCT00899223) and CALGB 20202 (molecular studies; NCT00900224), which involved collection of pretreatment BM aspirates and blood samples.

Mutational Profiling

Viable cryopreserved BM or blood cells of patients enrolled onto the CALGB 9665 tissue bank protocol were stored for future analyses prior to starting treatment. Mononuclear cells were enriched through Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation and cryopreserved until use. Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The mutational status of 80 protein-coding genes was determined centrally at The Ohio State University by targeted amplicon sequencing using the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA; ref. 37). Furthermore, testing for CEBPA mutations was performed with the Sanger sequencing method (38), thus adding up to a total of 81 genes analyzed in our study. All experimental details are provided in the Supplementary Data.

Clinical Endpoints and Statistical Analysis

Definitions of clinical endpoints, i.e., CR, DFS and OS, are provided in the Supplementary Data. Demographic and clinical features of Black and White patients were compared using the Fisher’s exact for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables.

Estimated probabilities of DFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test evaluated differences between survival distributions (18,39). A limited backward selection technique was used to build the final multivariable models for achievement of CR, DFS and OS. We used logistic regression for modeling CR and Cox proportional hazard regression for modeling DFS and OS for univariable and multivariable outcome analyses and adjusted P-values to control for per family error rate. All analyses were performed by the Alliance Statistics and Data Center on a database locked on June 9, 2020 using SAS 9.4 and TIBCO Spotfire S+ 8.2.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

We show that Young Black patients have not benefited as much as White patients from recent progress in AML treatment in the United States. Our data suggest that both socioeconomic factors and differences in disease biology contribute to the survival disparity and need to be urgently addressed.

Acknowledgements

Celebrating the life and accomplishments of Dr. Clara D. Bloomfield (1942-2020), who died unexpectedly on March 1, 2020.

The authors are grateful to the patients who consented to participate in these clinical trials and the families who supported them; to Christopher Manring and the CALGB/Alliance Leukemia Tissue Bank at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH, for sample processing and storage services; and to Lisa J. Sterling for data management. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers U10CA180821, U10CA180882, and U24CA196171 (to the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology), UG1CA283338, UG1CA189824, UG1CA233338, U10CA140158, UG1CA233331, U10CA180867, R35CA197734, UG1CA189850, and 5P30CA016058; the Coleman Leukemia Research Foundation; ASH Junior Faculty Scholar Award (A-KE); the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Foundation Young Investigator Award (JSB); the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Scholar Award (JSB); The D Warren Brown Foundation; the Pelotonia Fellowship Program (A-KE), and by an allocation of computing resources from The Ohio Supercomputer Center and Shared Resources (Leukemia Tissue Bank). Support to Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology and Alliance Foundation Trials programs is listed at https://acknowledgments.alliancefound.org.

Footnotes

A potential conflict of interest disclosure: B. Bhatnagar has received advisory board honoraria from Novartis, Kite Pharma, Celgene, Astellas and Cell Therapeutics Inc. C.J. Walker is a consultant for Vigeo Therapeutics and employed at Karyopharm Therapeutics; and has ownership interest in Karyopharm Therapeutics and Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. J.S. Blachly is a consultant/advisory board member for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, INNATE, KITE. B.L. Powell received honoraria from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Pfizer. J.E. Kolitz has received honoraria from Gilead, Magellan, and Novartis; consulting fees from Gilead, Magellan, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, and Seattle Genetics; institutional research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Cantex, Erytech, and Millennium; and travel support from Gilead, Novartis, and Seattle Genetics. R.M. Stone has served on independent data safety monitoring committees for trials supported by Celgene, Takeda, and Argenix; has consulted for AbbVie, Actinium, Agios, Amgen, Arog, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Biolinerx, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Fujifilm, Janssen, Juno, Macrogenics, Novartis, Ono, Orsenix, Pfizer, Roche, Stemline, Sumitomo, Takeda, and Trovagene; and has received research support (to the institution) for clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Agios, Arog, and Novartis. E.D. Paskett has received grants from Merck Foundation and Pfizer. J.C. Byrd has a consultancy/advisory role with Syndax, Novartis, Vincera; research funding from Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company, Genentech, Janssen, Acerta; ownership for Vincera. A.-K. Eisfeld has received a research grant from Novartis and has ownership interest in Karyopharm Therapeutics. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood 2017;129:424–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Döhner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1136–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasu S, Kohlschmidt J, Mrózek K, Eisfeld AK, Nicolet D, Sterling LJ, et al. Ten-year outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia not treated with allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission. Blood Adv 2018;2:1645–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrd JC, Mrózek K, Dodge RK, Carroll AJ, Edwards CG, Arthur DC, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461). Blood 2002;100:4325–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimwade D, Hills RK, Moorman AV, Walker H, Chatters S, Goldstone AH, et al. Refinement of cytogenetic classification in acute myeloid leukemia: determination of prognostic significance of rare recurring chromosomal abnormalities among 5876 younger adult patients treated in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials. Blood 2010;116:354–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimwade D, Mrózek K. Diagnostic and prognostic value of cytogenetics in acute myeloid leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2011;25:1135–61, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mrózek K, Heerema NA, Bloomfield CD. Cytogenetics in acute leukemia. Blood Rev 2004;18:115–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendler JH, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Mrózek K, Becker H, Metzeler KH, et al. RUNX1 mutations are associated with poor outcome in younger and older patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and with distinct gene and microRNA expression signatures. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3109–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metzeler KH, Becker H, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Kohlschmidt J, Mrózek K, et al. ASXL1 mutations identify a high-risk subgroup of older patients with primary cytogenetically normal AML within the ELN Favorable genetic category. Blood 2011;118:6920–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rücker FG, Schlenk RF, Bullinger L, Kayser S, Teleanu V, Kett H, et al. TP53 alterations in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotype correlate with specific copy number alterations, monosomal karyotype, and dismal outcome. Blood 2012;119:2114–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlenk RF, Döhner K, Krauter J, Fröhling S, Corbacioglu A, Bullinger L, et al. Mutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1909–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitman SP, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Becker H, Mrózek K, Margeson D, et al. FLT3 internal tandem duplication associates with adverse outcome and gene- and microRNA-expression signatures in patients 60 years of age or older with primary cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Blood 2010;116:3622–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisfeld A-K, Kohlschmidt J, Mims A, Nicolet D, Walker CJ, Blachly JS, et al. Additional gene mutations may refine the 2017 European LeukemiaNet classification in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia aged <60 years. Leukemia 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0872-3. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcucci G, Haferlach T, Döhner H. Molecular genetics of adult acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic and therapeutic implications. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:475–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mrózek K, Marcucci G, Paschka P, Whitman SP, Bloomfield CD. Clinical relevance of mutations and gene-expression changes in adult acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics: are we ready for a prognostically prioritized molecular classification? Blood 2007;109:431–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Appelbaum FR, Gundacker H, Head DR, Slovak ML, Willman CL, Godwin JE, et al. Age and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2006;107:3481–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MI, Ma Y, Mitchell BS, Rhoads KF. Understanding disparities in leukemia: a national study. Cancer Causes Control 2012;23:1831–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel MI, Ma Y, Mitchell B, Rhoads KF. How do differences in treatment impact racial and ethnic disparities in acute myeloid leukemia? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24:344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel MI, Ma Y, Mitchell BS, Rhoads KF. Age and genetics: how do prognostic factors at diagnosis explain disparities in acute myeloid leukemia? Am J Clin Oncol 2015;38:159–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekeres MA, Peterson B, Dodge RK, Mayer RJ, Moore JO, Lee EJ, et al. Differences in prognostic factors and outcomes in African Americans and Whites with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2004;103:4036–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell JD, Lathan C, Sholl L, Ducar M, Vega M, Sunkavalli A, et al. Comparison of prevalence and types of mutations in lung cancers among Black and White populations. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:801–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heath EI, Lynce F, Xiu J, Ellerbrock A, Reddy SK, Obeid E, et al. Racial disparities in the molecular landscape of cancer. Anticancer Res 2018;38:2235–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahal BA, Alshalalfa M, Kensler KH, Chowdhury-Paulino I, Kantoff P, Mucci LA, et al. Racial differences in genomic profiling of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1083–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ademuyiwa FO, Tao Y, Luo J, Weilbaecher K, Ma CX. Differences in the mutational landscape of triple-negative breast cancer in African Americans and Caucasians. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;161:491–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keenan T, Moy B, Mroz EA, Ross K, Niemierko A, Rocco JW, et al. Comparison of the genomic landscape between primary breast cancer in African American versus white women and the association of racial differences with tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3621–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger E, Delpierre C, Despas F, Bertoli S, Bérard E, Bombarde O, et al. Are social inequalities in acute myeloid leukemia survival explained by differences in treatment utilization? Results from a French longitudinal observational study among older patients. BMC Cancer 2019;19:883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byrne MM, Halman LJ, Koniaris LG, Cassileth PA, Rosenblatt JD, Cheung MC. Effects of poverty and race on outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Clin Oncol 2011;34:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirtane K, Lee SJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in hematologic malignancies. Blood 2017;130:1699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson B How structural racism can kill cancer patients: Black patients with breast cancer and other malignancies face historical inequities that are ingrained but not inevitable. Cancer Cytopathol 2020;128:83–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pallok K, De Maio F, Ansell DA. Structural racism - a 60-tear-old Black woman with breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1489–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nazha A, Al-Issa K, Przychodzen B, Abuhadra N, Hirsch C, Maciejewski JP, et al. Differences in genomic patterns and clinical outcomes between African-American and White patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood Cancer J 2017;7:e602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balsat M, Renneville A, Thomas X, de Botton S, Caillot D, Marceau A, et al. Postinduction minimal residual disease predicts outcome and benefit from allogeneic stem cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation: a study by the Acute Leukemia French Association Group. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Pollyea DA, Fathi AT, Roboz GJ, Altman JK, et al. Enasidenib in mutant IDH2 relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2017;130:722–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Fathi AT, Mims AS, Pratz KW, Savona MR, et al. Ivosidenib or enasidenib combined with intensive chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed AML: a phase 1 study. Blood 2020. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007233. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bierenbaum J, Davidoff AJ, Ning Y, Tidwell ML, Gojo I, Baer MR. Racial differences in presentation, referral and treatment patterns and survival in adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a single-institution experience. Leuk Res 2012;36:140–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eisfeld AK, Mrózek K, Kohlschmidt J, Nicolet D, Orwick S, Walker CJ, et al. The mutational oncoprint of recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2017;31:2211–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcucci G, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Mrózek K, Vukosavljevic T, Paschka P, et al. Prognostic significance of, and gene and microRNA expression signatures associated with, CEBPA mutations in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia with high-risk molecular features: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5078–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, McCulloch CE. Regression methods in biostatistics: linear, logistic, survival and repeated measure models. New York, NY USA: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.