Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) may cause immune-related adverse events that can affect any organ system, including the kidneys. Our study aimed to better characterize the incidence of and predictive factors for immune-related acute kidney injury (irAKI) as well as evaluate steroid responsiveness. An institutional database (Carolina Data Warehouse) was queried for patients who received ICIs and subsequently had substantial AKI, defined as a doubling of baseline creatinine. A retrospective chart review was performed to determine the cause of AKI. AKI events determined to be immune-related were further analyzed. 1766 patients received an ICI between April 2014 and December 2018. 123 (7%) patients had an AKI within one year of administration of the first ICI dose. 14 (0.8% of all patients who received ICIs) of the AKI events were immune-related. History of an autoimmune disease (N=2, 14%, p=0.04) or history of other immune-related adverse event (irAE) (N=8, 57%, p=0.01) were significant predictors of irAKI. Of 14 irAKI patients, nine received steroids with renal function improving to baseline in five patients, improving but not to baseline in two, and two without improvement in renal function, including one becoming dialysis-dependent. Age, sex, urinalysis findings, and primary tumor site were not associated with irAKI. irAKI is relatively uncommon but likely under recognized. Underlying autoimmune disease and history of non-renal ICI related irAEs are associated with irAKI. Early recognition and steroid administration are important for a positive outcome.

Keywords: immune-related adverse events, immune-related nephrotoxicity, interstitial nephritis, acute kidney injury

Introduction

Many cancers evade the host immune response by inhibition of T-cell activation through immune checkpoints including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1). (1-2) Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting CTLA-4, PD-1 and PD-L1 have revolutionized the treatment paradigm for many cancer types including melanoma, lung, bladder, and kidney cancers as well as others.

Unfortunately, the double-edged sword of ICIs is abrogation of self-tolerance, which can lead to immune-related adverse events (irAEs), defined as a heterogeneous array of inflammatory immune-mediated host toxicities that may warrant disruption or discontinuation of therapy and the administration of immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids. (3-4) Some potential irAEs include dermatitis, colitis, hepatitis, hypophysitis, thyroiditis, and pneumonitis (5); however, the frequency and type of irAE vary with the specific agent(s) (e.g. anti-CTLA-4 versus anti-PD-1/PD-L1) and duration of therapy. (6) With the increased use of ICIs to treat a myriad of cancers, ICI-related nephrotoxicity is likely an under recognized complication of treatment.

The mechanisms of immune-related acute kidney injury (irAKI) are incompletely understood but thought to be largely related to cell-mediated immunity. (7) A prevailing theory is that under inflammatory conditions, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II molecules are upregulated on proximal tubuloepithelial cells, allowing them to function as pseudo-antigen presenting cells; cytotoxic T-cells are activated and lead to self-destruction of these cells. Co-stimulatory molecules such as B7/CD28 and co-inhibitory molecules such as PD-1/PD-L1 guide the magnitude of T-cell response; when these inhibitory signals are blocked with ICIs, renal damage can occur. (8) Another theory involves ICI-specific T-cells that are formed after initial exposure to ICIs and with re-exposure become activated leading to host renal damage. (9) The vast majority of irAKI are due to acute interstitial nephritis, however, case reports also include lupus-like immune complex glomerulonephritis, pauci-immune glomerulonephritis, C3 glomerulopathy, thrombotic microangiopathy, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, minimal-change disease, membranous nephropathy, and IgA nephropathy. (7, 10-16)

A few studies have evaluated ICI-related AKI and in general have included a renal biopsy, which is often not feasible when an irAE is suspected. Similarly, most studies have evaluated irAKI in grade I AKI (creatinine up to 1.9x patient’s baseline per Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes [KDIGO] Criteria) (17), but based on the criteria, this degree of renal dysfunction may not be clinically significant. Additional factors may contribute to the development of ICI-related AKI with a recent report suggesting that proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use is associated with increased risk of irAKI. (18) In the current retrospective study, we sought to better characterize the incidence of clinically significant renal irAEs in patients receiving ICIs by restricting irAE events to KDIGO grade II AKI or greater (creatinine greater or equal to 2x baseline), to determine characteristics associated with renal irAEs, and to evaluate steroid responsiveness in patients who received corticosteroids to treat AKI.

Methods

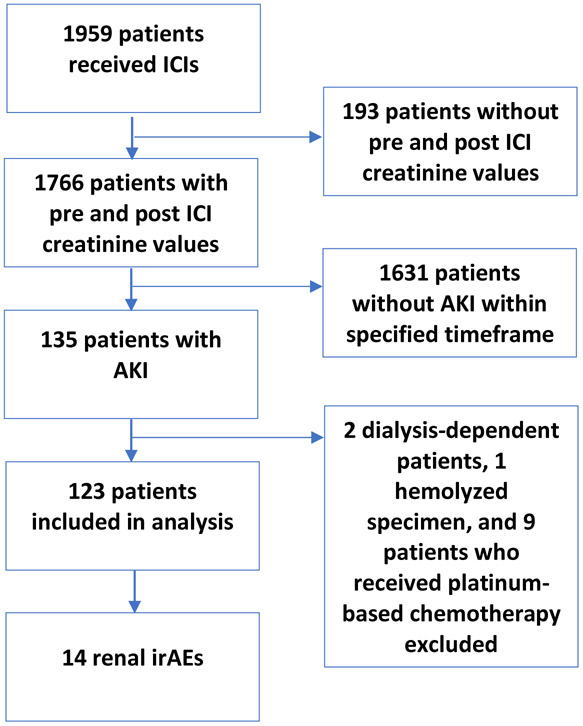

We performed a retrospective study by querying the electronic medical record through the Carolina Data Warehouse for Health, a division of the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute (NC TraCS), to compile all adult patients across UNC Health Care who had received an ICI between April 1, 2014 and December 31, 2018 for any malignancy at any stage. We identified the subset of patients who developed an AKI after ICI administration, defined as a doubling or more of their baseline creatinine (KDIGO grade II AKI or greater) from within a 12 month period following the administration of any ICI. For each patient with AKI, baseline creatinine was determined based on the calculated average of all of their documented creatinine values in the three months prior to the first ICI administration. Hemolyzed specimens, dialysis-dependent patients, and patients who received concurrently administered platinum-based chemotherapy were excluded (Figure 1). For every patient who had a doubling or more of their baseline calculated creatinine within a year after any ICI administration, a chart review was performed to identify the potential etiology of AKI as irAKI or non-immune related AKI (non-irAKI).

Figure 1:

Determination of patients receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors with immune-related acute kidney injury

Baseline individual patient data were collected including age, race, primary tumor type, prior autoimmune disease, and comorbid factors for kidney disease including coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes. Additional data collected included previous or concurrent non-renal irAE, specific ICI received, dates of AKI, time from first ICI administration to onset of AKI, urinalysis results, fractional excretion of sodium(FENa)/fractional excretion of urea (FEUrea) calculation, hydronephrosis (as determined by renal ultrasound or computerized tomography [CT] scan), use of potentially nephrotoxic drugs such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi)/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and antibiotics, nephrology consultations, whether the patient received corticosteroids, and whether or not the creatinine improved after corticosteroids. Partial improvement was defined as any decrease in creatinine value after administration of steroids and improvement to baseline was defined as returning to the baseline calculated creatinine.

All patients who were found to have AKI were included in the initial analysis other than those meeting the exclusion criteria as described above. In any case where irAKI was deemed possibly related to ICIs but not definite, chart review by two nephrologists (RR and VKD) was performed to determine attribution. In patients with irAKI, use of corticosteroids and steroid responsiveness (defined as any improvement in creatinine after administration) were determined. Data was collected and analyzed with chi-square for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum for continuous variables. All statistical tests were two-sided and a p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software: version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill.

Results

1959 patients received at least one dose of ICI, however, only 1766 patients had a creatinine value documented prior to and after administration of an ICI. Of those, 123 patients (7.6%) experienced AKI that met our inclusion criteria of doubling or more of creatinine from baseline (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the patients who had irAKI and non-irAKI are included in Table 1. Of 123 patients who experienced AKI, 59% were male, 74% were white with a median age of 67 years. The most common malignancy was non-small cell lung cancer (28%) followed by bladder cancer (16%). The majority of patients received either pembrolizumab (46%) or nivolumab (37%) monotherapy.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of patients who received ICI and developed AKI

| Patients with non-irAKI (N=109) |

Patients with irAKI (N=14) |

All Patients with AKI (N=123) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 63 (58%) | 8 (58%) | 72 (59%) | 0.91 |

| Race | 0.54 | |||

| White | 78 (71%) | 13 (93%) | 91 (74%) | |

| African American | 16 (15%) | 1 (7%) | 21 (17%) | |

| Other | 15 (14%) | 0 | 11 (9%) | |

| Median Age (years) | 67 | 66 | 67 | 0.69 |

| Range of Ages (years) | 31-90 | 48-90 | 31-90 | |

| Cancer Type | 0.25 | |||

| Non-Small Cell Lung | 28 (26%) | 6 (43%) | 34 (28%) | |

| Bladder | 20 (18%) | 0 | 20 (!6%) | |

| Melanoma | 13 (12%) | 3 (21%) | 16 (13%) | |

| Hepatocellular | 7 (6%) | 1 (7%) | 8 (7%) | |

| Renal Cell | 6 (6%) | 1 (7%) | 7 (6%) | |

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia | 5 (5%) | 2 (14%) | 7 (6%) | |

| Small Cell Lung Cancer | 7 (6%) | 0 | 7 (6%) | |

| Other | 23 (21%) | 1 (17%) | 24 (20%) | |

| Underlying Autoimmune Disease | 3 (3%) | 2 (14%) | 5 (4%) | 0.04 |

| Documented Other irAE | 11 (10%) | 9 (57%) | 19 (15%) | 0.01 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Coronary Artery Disease | 21 (19%) | 2 (14%) | 23 (19%) | 0.65 |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 29 (27%) | 4 (29%) | 33 (27%) | 0.88 |

| Hypertension | 46 (42%) | 8 (57%) | 54 (44%) | 0.29 |

| CKD3 or Greater | 27 (25%) | 6 (43%) | 33 (27%) | 0.15 |

| Urinalysis | ||||

| WBC on UA >5 (per HPF) | 41 (51%) | 7 (54%) | 48 (39%) | 0.86 |

| RBC on UA>5 (per HPF) | 34 (43%) | 4(31%) | 37 (30%) | 0.43 |

| Leukocyte Esterase on UA | 29 (36%) | 6 (46%) | 35 (28%) | 0.49 |

| Proteinuria >30 mg/dL | 46 (58%) | 7 (54%) | 53 (43%) | 0.81 |

| ICI Received | ||||

| Pembrolizumab | 49 (45%) | 8 (57%) | 57 (46%) | |

| Nivolumab | 42 (39%) | 4 (29%) | 46 (37%) | |

| Ipilimumab | 0 | 1 (7%) | 7 (6%) | |

| Atezolizumab | 7 (6%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | |

| Ipilimumab/Nivolumab | 11 (10%) | 1 (7%) | 12 (10%) | |

| Concurrent Chemotherapy | 10 (9%) | 2 (14%) | 12 (10%) | |

| Concurrent Targeted Therapy | 6 (6%) | 0 | 6 (5%) | |

| Median Baseline Cr (mg/dL) | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.71 |

| Interquartile Range Pre-Treatment Cr (mg/dL) | 0.35-3.21 | 0.58-2.11 | 0.40 | |

| Cause of AKI | ||||

| Acute Interstitial Nephritis | 0 | 14 | 14 (11%) | |

| Pre-Renal Azotemia | 77 (71%) | 0 | 77 (63%) | |

| Post-Renal Obstruction | 23 (21%) | 0 | 23 (19%) | |

| Acute Tubular Necrosis | 7 (6%) | 0 | 7 (6%) | |

| Drug-Induced | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | |

| Contrast-Induced Nephropathy | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) |

AKI = acute kidney injury; CKD = chronic kidney disease; Cr = creatinine; HPF = high power field; ICI = immune checkpoint inhibitor; ir = immune related; RBC = red blood cells; UA = urinalysis; WBC = white blood cells.

14 of the AKI events (0.8% overall incidence in patients receiving ICI) were determined to be renal irAEs based on chart review. Supplementary Table 1 outlines detailed characteristics for the patients with renal irAE. There was not a significant difference in the median time to AKI onset between irAKI versus non-irAKI. Notably, patients with irAKI were more likely to have pre-existing autoimmune disease (p=0.04) and more likely to have another documented irAE than patients with non-irAKI (p=0.01). Patients with irAKI had more severe AKI with a median change of 4-fold in the baseline creatinine in irAKI patients as compared to 2.6-fold baseline in non-irAKI patients (p=0.03). Patients with irAKI were more likely to have had a nephrology consultation in the peri-AKI period (23% of the patients with non-irAKI and 57% of the patients with irAKI, p=<0.01). Of the 14 patients in our study with confirmed irAKI, nine (65%) received corticosteroids: 7 of 9 received 1mg/kg of prednisone, one 0.5mg/kg, and one 2mg/kg - with five patients improving to their baseline creatinine, two patients with partial improvement in creatinine, one patient progressing to hemodialysis, and one patient dying soon after steroid administration from pneumonitis. The time period to improvement with corticosteroids for patients with irAKI was within one week for five patients and within one month for the other two patients. Of the other five patients with irAKI who did not receive steroids, three expired and two had an improvement in renal function to baseline. Of the patients who expired not having received steroids, one died from septic shock and acute liver failure, one died due to renal and acute liver failure, and one died from renal failure. Urinalysis findings (by laboratory analysis) and comorbidities were not associated with irAKI (Table 1). Finally, only one of 14 patients with renal irAEs was receiving a PPI so we could not evaluate a potential role of PPI use in irAKI in the current study.

Discussion

Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related AKI, of substantial degree, may be less common than other irAEs with an incidence in the current study of 0.8%, but it represents an important and likely under recognized toxicity of ICI therapy. There was no significant difference in the median time to AKI onset between the irAKI and non-irAKI, although irAKI was more likely to result in a greater increase in creatinine (4.0x versus 2.6x baseline creatinine) in spite of similar baseline renal function.

The most comprehensive meta-analysis to date evaluating AKI with ICIs included a total of 11,482 patients where the relative risk of AKI, defined as an increase in creatinine of 0.3mg/dL or greater from baseline, in patients who received nivolumab or pembrolizumab compared to non-nephrotoxic controls was 4.19 and the cumulative incidence of AKI was 2.2%, though this included all etiologies. (19) One study analyzed pooled data from 3695 patients enrolled in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials who received ICIs and estimated the incidence of renal irAE, again defined as an increase in creatinine of 0.3mg/dL or greater from baseline, to be 2.2% with events occurring more commonly with combination ICI therapy than with monotherapy. (20) Another experience cited an incidence as high as 13.9% with renal irAE being associated with the highest toxicity-related costs compared to other irAEs ($8854 per patient). (21-22) Finally, a recent retrospective study evaluating renal irAE estimated a prevalence of about 3%, defining AKI as creatinine 1.5-fold of baseline. This study also found a possible association between PPI use and sustained irAKI (18), which we could not corroborate due to only one patient using a PPI in our irAKI population.

Similar to other studies, laboratory urinalysis findings and FENa/FEurea were not predictive of the etiology of AKI nor were tumor type, race, sex, coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, or chronic kidney disease. Consistent with previous studies, in the current study, pre-existing autoimmune disease was a risk factor for the development of irAKI. (23) History of other irAE was also a risk factor for the development of irAKI, with hepatitis occurring in two patients and pneumonitis in two patients. Patients found to have irAKI were also more likely to have had a nephrology consultation in the peri-AKI period. Of the 14 irAKIs, none of the patients underwent renal biopsy, although one did have an autopsy confirming irAKI. These data emphasize the potential for early nephrology consultation to aid in confirmation of the diagnosis of irAKI and potential consideration of renal biopsy when appropriate to verify the histologic lesion.

With regard to the management of irAKI, the ASCO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of immune related adverse events state that grade two adverse events defined as creatinine 2–3x baseline should be managed with holding ICIs temporarily, consulting nephrology, and giving corticosteroids. (24) Of the patients who received steroids, only 5 of 9 had improvement of renal function to baseline with three of the other four progressing to dialysis-dependence or death. Of the five who did not receive steroids, two improved within one month and three died with two deaths attributed partially to renal failure. This highlights the potential severity of irAKI and need for prompt recognition, early involvement of nephrology, and treatment with corticosteroids if high suspicion exists.

Limitations of the current study include its retrospective design, the use of a more restrictive definition of AKI limiting sensitivity (2x baseline creatinine as compared to 1.5x baseline for most other studies), (18) a predominantly white patient population, lack of biopsy confirmation of irAKI, a small sample size limiting ability to perform multivariable modeling, and a single institution experience. The analysis is also limited by the exclusion of patients without documented pre and post ICI creatinine values as well as by patients with early death after treatment or those lost to follow up, which may lead to underestimation of the true irAKI incidence. The risk of irAKI must be balanced against the availability of alternative agents for the specific cancer type. Our more restrictive AKI definition is one that may have more clinical significance as it may prompt earlier interruption or discontinuation of therapy. Overall, our study suggests that clinically significant irAKI is a relatively uncommon entity among patients treated with ICIs, however, early recognition is critically important to prevent the possibility of irreversible renal damage. High clinical suspicion should exist in patients with pre-existing autoimmune disease and a history of other irAEs, and prompt initiation of corticosteroids should occur. Early involvement of nephrology in the care of patients with suspected irAKI is recommended including the need to consider a renal biopsy for diagnosis and to better understand the pathophysiology of the kidney injury. Future efforts should prospectively follow patients treated with ICIs to better define the incidence, risk factors, and natural history of irAKI.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1

AIN = acute interstitial nephritis; AKI = acute kidney injury; AML = acute myeloid leukemia; ATN = acute tubular necrosis; Cr = creatinine; F = female; HPF = high power field; ICI = immune checkpoint inhibitor; irAE = immune-related adverse event; Ipi = ipilimumab; LE = leukocyte esterase; M = male; Nivo = nivolumab; Pembro = pembrolizumab; T1DM = type 1 diabetes; RBC = red blood cells; WBC = white blood cells

Table 2:

Outcomes of patients who received ICI and developed AKI

| Patients with non-irAKI (N=109) |

Patients with irAKI (N=14) | All Patients with AKI (N=123) |

P Value Comparing non- irAKI to irAKI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Time to AKI (days) | 91 | 71.5 | 89 | 0.4 |

| Median Change in Cr from Baseline (mg/dL) | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 0.02 |

| Magnitude of Change in Cr (Post-Treatment/Pre-Treatment) | 2.6 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 0.02 |

| Median Maximum Cr (mg/dL) | 2.4 | 3.5 | 2.6 | <0.01 |

| Nephrology Consultation | 26 (24%) | 8 (57%) | 34 (28%) | <0.01 |

| CS Administered | 8 (7%) | 9 (64%) | 18 (15%) | <0.01 |

| Cr Improved with CS | ||||

| Yes, to baseline | 4 (50%) | 5 (56%) | 9 (7%) | |

| Yes, not to baseline | 0 | 2 (22%) | 3 (2%) | |

| No | 4 (50%) | 1 (11%) | 5 (4%) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (11%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Time Period to Improvement after CS | N=4 | N=7 | N=11 | |

| Within One Week | 4 (100%) | 5 (71%) | 9 (82%) | |

| Within One Month | 0 | 2 (29%) | 2 (18%) |

AKI: acute kidney injury; Cr = creatinine; CS = corticosteroids; ICI = immune checkpoint inhibitor; ir = immune-related;

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the editorial assistance of the NC Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute, which is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR002489.

Tracy Rose is supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (grant number 2015213) and receives research funding from National Cancer Institute grant 1K08CA248967–01.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This retrospective study was approved by the UNC-CH IRB (Reference: 19–2050). Consent not needed due to retrospective nature. All health information was de-identified. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

Data was housed on a secure, password protected drive. All charts and data extraction tables are available for review

Disclosures and Conflicts of Interest

Jonathan Sorah: none

Tracy Rose: receives funding from GeneCentric Therapeutics, Genentech/Hoffman-La Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck.

Roshni Radhakrishna: none

Vimal Derebail: serves in a consulting/advisory role to Novartis and Retrophin.

Matthew Milowsky: serves in a consulting/advisory role for BioClin Therapeutics and research funding to institution from Merck, Acerta Pharma, Roche/Genentech, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Seattle Genetics, Astellas Pharma, Clovis Oncology, Inovio Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, X4 Pharmaceuticals, Mirati Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Constellation Pharmaceuticals, Jounce Therapeutics, Syndax, Innocrin Pharma, MedImmune, and Cerulean Pharma.

References

- 1.Wang X, Teng F, Kong L, et al. PD-L1 expression in human cancers and its association with clinical outcomes. OncoTargets and therapy. 2016;9:5023–5039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchbinder E, Desai A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Pathways: Similarities, differences, and implications of their inhibition. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;39:98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang P, Chen Y, Song S, et al. Immune-Related adverse events associated with anti-PD-1/PD-L2 treatment for malignancies: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2017;8:730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar V, Chaudhary N, Garg M, et al. Current diagnosis and management of immune related adverse events (irAEs) induced by immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2017;8;49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fecher L, Agarwala S, Hodi F, et al. Ipilimumab and its toxicities: a multidisciplinary approach. The Oncologist. 2013;18:733–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber J, Yang J, Atkins M, et al. Toxicities of immunotherapy for the practitioner. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;18:2092–2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mamlouk O, Selamet U, Machado S, et al. Nephrotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors beyond tubulointerstitial nephritis: single-center experience. Journal of ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 2019;7(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waeckerle-Men Y, Starke A, Wuthrich R. PD-L1 partially protects renal tubular epithelial cells from the attack of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2007;22:1527–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perazella M Checkmate: kidney injury associated with targeted cancer immunotherapy. Kidney International. 2016;90:474–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izzedine H, Mateus C, Boutros C, et al. Renal effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2016;32:936–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fadel F, El Karoui K, Knebelmann B. Anti-CTLA4 antibody-induced lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:211–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Brom R, Abdulahad W, Rutgers A, et al. Rapid granulomatosis with polyangiitis induced by immune checkpoint inhibition. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:1143–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daanen R, Maas R, Koornstra R, et al. Nivolumab-associated nephrotic syndrome in a patient with renal cell carcinoma: a case report. J Immunother. 2017;40:345–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitchlu A, Fingrut W, Avila-Casado C, et al. Nephrotic syndrome with Cancer immunotherapies: a report of 2 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70:581–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kishi S, Minato M, Saijo A, et al. A case of IgA nephropathy after nivolumab therapy for postoperative recurrence of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Intern Med. 2018;57(9):1259–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung K, Zeng X, Bilusic M. Nivolumab-associated acute glomerulonephritis: a case report and literature review. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Journal of the International Society of Nephrology. 2012; 2(1). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seethapathy H, Zhao S, Chute D, et al. The incidence, causes, and risk factors of acute kidney injury in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019; ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manohar S, Kompotiatis P, Thongprayoon C, et al. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor treatment in associated with acute kidney injury and hypocalcemia: meta-analysis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2019;34:1:108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortazar F, Marrone K, Troxell M, et al. Clinicopathological features of acute kidney injury associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Kidney Int. 2016;90(3):638–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason N, Khushalani N, Weber J, et al. Modeling the cost of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related toxicities. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl):6627. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wanchoo R, Karam S, Uppal N, et al. Adverse renal effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a narrative review. Am J Nephrol. 2017; 45(2):10–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kartolo A, Sattar J, Sahai V, et al. Predictors of immunotherapy-induced immune-related adverse events. Curr Oncol. 2018;25(5):403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brahmer J, Lacchetti C, Schneider B, et al. Management of immune-related adverse vents in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1714–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1

AIN = acute interstitial nephritis; AKI = acute kidney injury; AML = acute myeloid leukemia; ATN = acute tubular necrosis; Cr = creatinine; F = female; HPF = high power field; ICI = immune checkpoint inhibitor; irAE = immune-related adverse event; Ipi = ipilimumab; LE = leukocyte esterase; M = male; Nivo = nivolumab; Pembro = pembrolizumab; T1DM = type 1 diabetes; RBC = red blood cells; WBC = white blood cells