Abstract

Objective:

To describe our modification of Behavioral Activation to address social isolation and loneliness: Brief Behavioral Activation for Improving Social Connectedness. Our recent randomized clinical trial demonstrated the effectiveness of the intervention, compared to friendly visit, in alleviating loneliness, reducing depressive symptoms, and increasing social connectedness with lonely homebound older adults receiving home-delivered meals.

Methods:

We modified the Brief Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression to address social isolation and loneliness by addressing each of its key elements: Psychoeducation; intervention rationale; exploration of life areas, values and activities; and activity monitoring and planning. The intervention consisted of 6 weekly sessions, up to 1 hour each. Interventionists were bachelor’s-level individuals without formal clinical training who participated in an initial one-day training as well as ongoing supervision by psychologists and social workers trained in BA throughout the study delivery period.

Results:

We provide three case examples of participants enrolled in our study and describe how the intervention was applied to each of them.

Conclusions:

Our preliminary research suggests that Behavioral Activation modified to address social connectedness in homebound older adults improves both social isolation and loneliness. This intervention has potential for scalability in programs that already serve homebound older adults. Further research is needed to solidify the clinical evidence base, replicate training and supervision procedures, and demonstrate the sustainability of Brief Behavioral Activation for Improving Social Connectedness for homebound and other older adults.

Keywords: Social isolation, Loneliness, Behavioral activation, Tele-delivery, Lay-coach facilitation

INTRODUCTION

Social isolation and loneliness, objective and subjective indicators of lack of social support and interaction, are pervasive among US older adults,1,2 and their detrimental health effects have been well documented.3–9 Social distancing requirements of the COVID-19 pandemic have exacerbated these problems. The prevalence and deleterious health effects of social isolation and loneliness are especially notable among homebound older adults given their limited social engagement and activities due to their health conditions and mobility impairment.10,11 For low-income homebound older adults, lack of financial resources and transportation also pose significant barriers to maintaining social connectedness.12

Our recent randomized clinical trial demonstrated the effectiveness of Brief Behavioral Activation for Improving Social Connectedness (BBAISC) in alleviating loneliness, increasing social connectedness, and reducing depressive symptoms with lonely homebound older adults. BBAISC was delivered using tele-conferencing by lay counselors and compared to tele-conferenced friendly visits. Study participants were recruited from home-delivered meals programs of aging services agencies in Central Texas (urban) and New Hampshire (rural)13.

In this report, we provide more information about BBAISC, including how we modified traditional Behavioral Activation (BA) to tackle social isolation and loneliness. Our decision to target social connectedness was prompted by directors of several aging services agencies who identified loneliness as a predominate problem for their home-delivered meal clients. Research indicating the lack of effective interventions for social isolation9 prompted our development of BBAISC. Our approach took into account potential scalability, including the use in home-delivered meals (HDM) programs, also known as “Meals on Wheels.” HDM programs are the most widely available community-based services to meet the nutritional needs of 2.4 million homebound adults aged 60+.14 Although a large proportion of 5,000+ HDM programs focus on meal delivery, increasing numbers of these programs have begun to incorporate other services to meet homebound older adults’ independent living needs.

Example of HDM Participant Experiencing Social Isolation and Loneliness

Ms. N. is an 80-year-old, divorced, White woman living alone in rural New Hampshire (NH). Her medical conditions include arthritis, emphysema, and Ileostomy as well as a history of cancer. She started receiving HDM after her mobility was restricted due to medical events. Ms. N recently moved from an urban neighborhood to this rural and isolated location to be near her daughter and granddaughter. She has occasional contact with her daughter, but not as much as she would like. Prior to moving, Ms. N. had access to an array of enjoyable activities just outside her doorstep and frequently interacted with the people in her neighborhood. Now, living in a rural area, she says there is “nothing to do” and will go days without seeing another person. She says she is lonely and longs to spend time with other people. She wants to establish friendships but she feels overwhelmed and reports feeling anxious in social situations.

Homebound Status, Social Isolation, and Behavior

As exemplified by Mrs. N, HDM recipients are characterized by mobility limitations and other functional impairments that present challenges to continued engagement in rewarding activities related to important life areas and associated values. Disrupted engagement in important life areas and associated values often corresponds to an overall reduction in social contact, which may result in objective social isolation and/or feelings of loneliness. Some HDM recipients are unable to engage in activities that they once enjoyed due to functional limitations, for example, being unable to walk the dog following surgery. Others may stop engaging in rewarding activities when they are unable to do the activity the same way it had always been done, for example, ceasing to read to a grandchild when s/he moves away. Regardless of the reason the activity stops, the result is the same, decreased contact with the important values the activities represent. While many HDM recipients are able to adapt to their changing life context to find ways to stay connected and engaged, others experience more difficulty and may benefit from a structured, yet personalized, approach to increasing time for values-based activities. Changing behavior to align with values (with respect to important life areas) may involve identifying new activities, modifying familiar activities, and/or potentially stopping or reducing certain behaviors or activities that are values-inconsistent.

Behavioral Activation for Depression

Behavioral Activation (BA) is an empirically supported, structured, typically 18–24 sessions long, psychotherapy for depression that aims to activate participants in specific ways that will increase engagement in rewarding activities.15,16 One version of BA, Brief Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression (BATD-R), involves a shorter course of treatment, typically 8–15 sessions, and focuses specifically on fortifying participants’ problem-solving skills and providing structure and support to help participants define their values, that is, identify what matters the most to them with respect to important life areas, and increase engagement with values-based activities.17

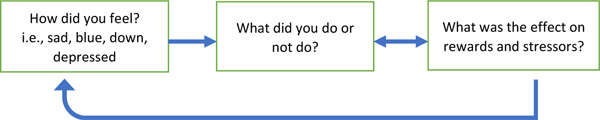

A key behavioral feature of depression is the tendency to disengage from routines and activities and generally withdraw from one’s environment (i.e., “life context”) – this feature is termed “behavioral avoidance.” In the short-term, avoidance may act as a temporary mood improvement strategy by helping one to “escape” negative feeling states associated with certain routines, activities, or obligations. However, depressed mood may be exacerbated overtime due to the effects of avoidance on decreasing rewards and/or increasing stressors in one’s life context.15 Specifically, by disengaging from daily routines and withdrawing from one’s environment one simply has fewer opportunities to come in contact with pleasurable, masterful and/or values-aligned experiences (rewards) as part of daily living. Further, consequences incurred from neglected responsibilities or lack of participation in important life areas (social, occupational, financial, health, etc.) may cause more problems (stressors) in one’s life context. These effects on rewards and stressors may in turn cause individuals to feel more alienated, ashamed, discouraged, hopeless, burdensome, and disconnected from valued-life areas. Feeling worse typically then promotes more avoidance – this is referred to in BA as the “downward spiral of depression,” see Figure 1.15–17

Figure 1.

Downward spiral of depression adapted based on the BA conceptual model presented by Martell et al., (2013).

BA participants are encouraged to schedule and organize their day based on what is important or necessary (values-driven behaviors), rather than their current mood or feeling state.16 Overall, BA has three primary goals, which are informed by the behavioral conceptualization of depression detailed above18: 1) Increase engagement in mood-enhancing behaviors (i.e., “rewarding,” values-aligned and/or pleasurable activities), 2) Decrease engagement in activities that maintain or increase depression, and 3) Solve problems that limit access to mood-enhancing behaviors, maintain or increase avoidance behaviors, or exacerbate stressors.15

BA interventionists are expected to follow guidelines (as described in intervention manuals16,17 ) to maintain session structure and uphold a particular “coach-like” counseling style. BA is an inherently patient-centered approach, and it is critical that the interventionist work collaboratively with participants to ensure that intervention is carefully tailored to address rewards and stressors within each individual life’s context, selecting activities based on their likelihood of having meaningful impacts on rewards and stressors for the individual.16 Further, BA interventionists help participants examine their own behavior and its short and long-term impacts on mood through the use of therapeutic techniques such as “functional analysis” during sessions and activity planning and monitoring for homework between sessions.

Modifying Brief Behavioral Activation to Address Social Isolation and Loneliness

We modified BATD-R17 to address social isolation and loneliness by addressing each of the intervention’s key elements:

Psychoeducation: Our primary modifications were made in the first session, which emphasizes psychoeducation and overview of intervention rationale. We replaced psychoeducation regarding the context of depression and behavior with psychoeducation regarding the context of homebound status, social isolation/loneliness, and associated changes in behavior.

BA intervention rationale: In BA for depression, the intervention rationale builds the concept that changing behavior (i.e., increasing values-based activities) changes the balance of rewards and stressors in one’s life context, which has resultant impacts on mood (i.e., decrease in depressive symptoms). For our study, we modified the intervention rationale to frame how changing behavior (i.e., increasing values-based activities) can positively impact social connectedness (i.e., improve social connectedness and reduce loneliness). However, the description of how the intervention works was not changed (i.e., increases in values-based activities increase opportunities for rewards, and decrease the amount and/or impact of stressors in one’s life context).

Exploration of life areas, personally-identified values and activities: This element was not changed but followed naturally from the revised intervention rationale.

Activity monitoring and planning: We used simplified participant monitoring forms based on our previous experience delivering brief behavioral interventions to homebound older adults via tele-approaches19,20.

Brief Behavioral Activation for Improving Social Connectedness Intervention Structure

Brief Behavioral Activation for Improving Social Connectedness (BBAISC) consisted of 6 weekly sessions, up to 1 hour each, consistent with our previous experience delivering brief, evidence-based tele-interventions for HDM recipients20. Each session had homework assignments focused on activity monitoring and scheduling (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Modified BA Intervention to Reduce Social Isolation and Loneliness among Older Adults

| Session | Format | Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1* | In-person | • Psychoeducation on homebound status, isolation, and behavior |

| • Intervention rationale | ||

| • Introduce activity monitoring | ||

| 2 | Tele | • Review activity monitoring |

| • Exploration of life areas, values, and activities | ||

| • Introduce activity planning | ||

| 3 | Tele | • Review activity monitoring |

| • Activity planning | ||

| 4 | Tele | • Review activity monitoring |

| • Activity planning | ||

| 5 | Tele | • Review activity monitoring |

| • Activity planning | ||

| 6 | Tele | • Review activity monitoring |

| • Relapse Prevention | ||

Note.

Session 1 occurred in-person and was completed with study baseline assessment during our trial. At this time participants were provided a workbook that contains all intervention assignment forms and handouts.

Training and Supervision

BBAISC interventionists were Bachelor’s Degree-level individuals without formal clinical training, but most had experience working in aging services (or with older adults). In preparation for delivering the intervention, they participated in a one-day training led by psychologists and social workers. The training that focused on the delivery of BBAISC and the context of social isolation and loneliness among older adults who receive HDM. The initial training had three main components: 1) Background on the context of HDM; 2) Background and conceptual framework for BA; and 3) Instruction and practice in BBAISC delivery. Instruction and practice in BBAISC delivery included discussion of the intervention rationale, specific instructions regarding how to conduct each session, review of key tasks for maintaining fidelity, guidance regarding how to introduce and interpret participants’ homework, suggestions for how to address common problems that may arise during intervention delivery (e.g., homework noncompletion), and role playing.

Interventionists also participated in weekly supervision by psychologists or social workers for the duration of the intervention phase of the study. Supervision focused on reviewing recorded sessions, providing feedback to optimize fidelity, introducing/reinforcing counseling techniques, and problem-solving barriers to intervention delivery. All sessions were recorded and at least 25% were reviewed by the interventionist who conducted the session as well as a supervisor. Additionally, interventionists completed notes for each session documenting highlighted life areas/values, the activity tracking a participant reported in session and his or her activity planning for next session. As relevant, barriers and contextual factors that appeared to interfere with activity planning in-session and/or activity completion between sessions (homework) were documented in the note for reference. All of these actions allowed the team to monitor fidelity and reinforce essential skills in the delivery of BA while monitoring participant safety.

Toolkit/Participant Folders

Interventionists were provided a BBAISC training PowerPoint slide deck, a BBAISC fidelity checklist for each session, and a session note template to complete for each session. All participants were given a BBAISC Participant Folder which included handouts explaining key concepts, activity monitoring and planning forms, and all other homework assignments.

Applying Brief Behavioral Activation for Improving Social Connectedness: Three Case Examples

We will now describe several cases of participants enrolled in our study and how the intervention was applied to each of them. These cases were selected because they exemplify loneliness risk exacerbated by circumstances often associated with late life and allow us to demonstrate how BBAISC was applied.

Ms. N

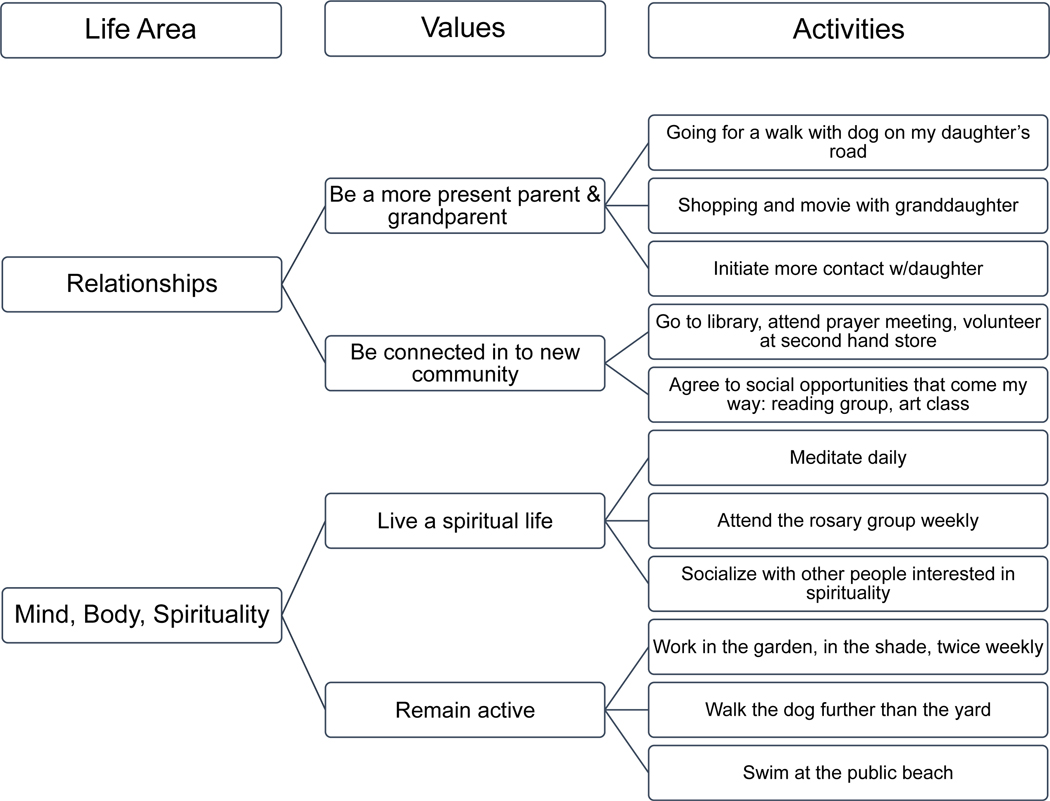

“Ms. N” , described above, was referred to our study by her HDM case worker when she screened positive for loneliness on the 3-item UCLA Loneliness Scale1 (people with scores of 6 or higher were eligible for our study) during her HDM eligibility assessment. Figure 2 illustrates how the BBAISC Interventionist worked with Ms. N to articulate her own values with respect to each important life area and to identify specific activities that align with each corresponding value and important life area. In general terms, Ms. N. wanted to meet new friends and become connected within her new community of people even though she felt anxious in social situations. She was aware of how she would like her life to be different and the types of activities she would like to do, but she was unsure about how to achieve her goals.

Figure 2.

Ms. N’s life areas, values, and corresponding activities generated while participating in Brief Behavioral Activation for Improving Social Connectedness

Ms. N identified relationships, spirituality, and health (i.e., remain active) as important life areas to focus on during the intervention. For example, she identified the value “to become connected in my new community,” which was related to the broader life area of “relationships.” To increase her contact with this value, the BBAISC Interventionist helped Ms. N to define goals and specify plans to start going to the library, attend prayer meetings, and volunteer at a local secondhand store. Throughout the intervention, Ms. N struggled with fatigue and exhaustion, particularly when engaging in new and socially interactive activities. Additionally, Ms. N contracted an infection that contributed to increased fatigue and limited participation in certain activities. In response to these difficulties, the BBAISC Interventionist reinforced the BA rationale for acting according to planned activities, rather than a temporary feeling or mood state. When our team checked back with Ms. N at the 12 months follow-up assessment, she described her experience with BBAISC as learning “stepping stones” to help her get from one smaller goal to the next, somewhat larger goal. She was continuing to participate in many of the activities she had initiated during the intervention (e.g., volunteering, spending time with family, and walking). Compared to her baseline state, she reported significant improvement in feelings of loneliness and increased social connectedness, which was consistent with her performance on our primary outcome measures of social isolation and loneliness: the Duke Social Support Index21 and the 8-item PROMIS 22 Social Isolation Scale22.

Mrs. R

“Mrs. R” was a 78-year-old married, Hispanic woman, residing in a large city in TX. She was the sole caregiver for her husband who had mid-stage dementia and was homebound. Mrs. R used to be very social, but more recently spent most of her time engaged in caregiving activities that were extensive. Although she was herself mobile, Mrs. R was unable to leave the house because her husband required fulltime supervision. All their children and grandchildren were working or going to school full-time during weekdays, and Mrs. R did not want to burden them by asking help.

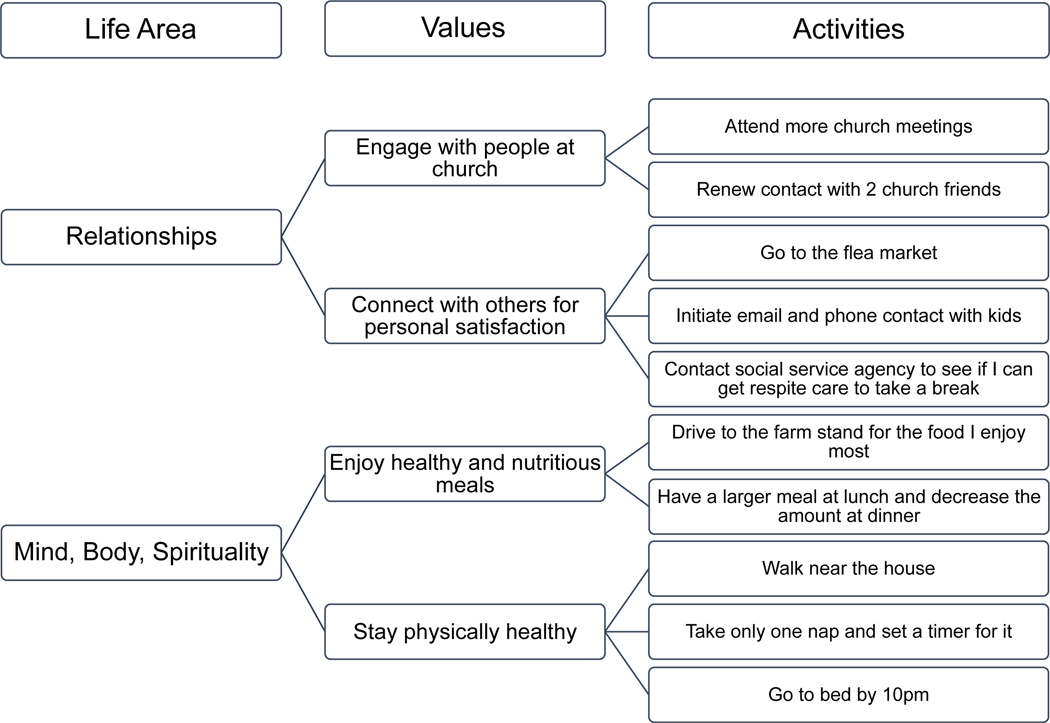

Figure 3 illustrates of how the BBAISC Interventionist worked with Mrs. R. She had spent much of her life devoted to taking care of her children and husband and was quick to deflect conversations about herself to others in her life (e.g., husband). Her BBAISC Interventionist emphasized the importance of identifying personal values connected to important life areas and worked with Mrs. R to clarify what was important to her at this phase of her life. While Mrs. R was busy and much of her time was scheduled, she failed to engage in activities related to important values other than “being a supportive wife.” Once Mrs. R clarified her values and identified activities that were closely related with her values, she was successful in scheduling and actually completing these activities. During the intervention she increased her walking, church meeting attendance, and rekindled relationships with two church friends. Further, she explored aging service supports that would be able to help care for her husband so she could engage in other, non-caregiving activities.

Figure 3.

Mrs. R’s life areas, values, and corresponding activities generated while participating in Brief Behavioral Activation for Improving Social Connectedness

Mrs. R’s overall trajectory of success started slowly but increased steadily. Along the way, Mrs. R struggled with many brief intrusions related to her husband’s needs or with ruminating over long-term, complex goals. Upon 12 months follow up, Mrs. R reported she had maintained gains. Notably, Mrs. R even organized a trip with her daughters and arranged for someone else to care for her husband while she was away, something she had not done in years.

Mr. C

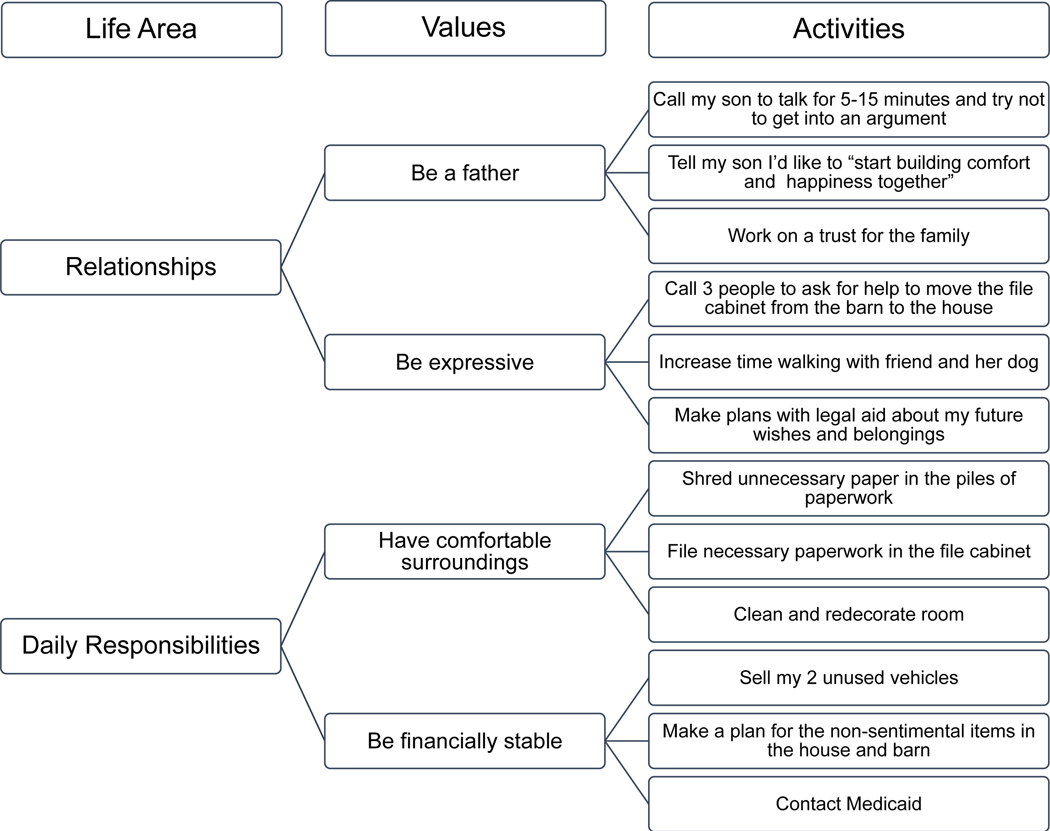

“Mr. C” was a 74-year-old widowed, White man, and residing in a small NH town. While he denied clinically significant depressive symptoms on the PHQ-923, he reported feelings of hopelessness and felt he was a burden to his family and others. He appeared unkept. Mr. C lived in a large old house but was occupying only one cluttered room. Due to financial constraints, this was the only room he heated through the winter. Mr. C had little to no contact with others, either face to face or through computer/phone aside from one friend. At intervention outset, Mr. C was lonely and pained by his conflictual relationship with his son; however, he was resigned to his current situation. He explained that there were too many barriers to building relationships with his family due to his strained relationship with his son. He felt discouraged about building relationships outside his family because “who would want to spend time with me?” Mr. C also expressed a need to get more organized with his paperwork because of his healthcare needs and requests for documents.

Although Mr. C predicted that he would not be able to successfully increase his values aligned activities, throughout the intervention he consistently accomplished more than the tasks he scheduled. Figure 4 illustrates of how the BBAISC Interventionist worked with Mr. C. His interventionist utilized the BA framework to help him learn to set small, feasible goals (i.e., graded tasks) that were highly related to his values. He was able to accomplish numerous tasks that served to increase rewards, such as spending time with friends, and decrease stressors in his daily context, such as living in clutter. By the final intervention week, Mr. C’s room was redecorated, his papers were in order, he had declared a truce with his son, and he had a draft of a trust written up for his grandchildren. Upon 12 months follow up, Mr. C reported he had negotiated with his son to assist him in paying back taxes on his house; while he was still living in only one room of the house, it remained well kept, tidy, and free from clutter and paperwork.

Figure 4.

Mr. C’s life areas, values, and corresponding activities generated while participating in Brief Behavioral Activation for Improving Social Connectedness

Conclusions

In this report, we described how we modified Behavioral Activation to work with older adults experiencing loneliness and social isolation. Previously in this journal, we demonstrated the effectiveness of Brief Behavioral Activation for Improving Social Connectedness, alleviating loneliness and increasing social connectedness with homebound older adults identified through home delivered meals services13. Being homebound may exacerbate the challenges of improving social connectedness. The intervention may also be useful in working with older adults who have greater mobility and functioning, but report loneliness or social isolation.

While social isolation and loneliness are not considered psychiatric conditions, numerous studies have documented their negative impact on quality of life, mental health, physical wellbeing and mortality. Thus, interventions that target social connectedness in older adults are relevant to both mental health practice and research. The public health significance of such interventions is further underscored by the Covid-19 pandemic and associated “social distancing” requirements that have increased both the prevalence of and public attention to the problems of social isolation in older adults. Social distancing requirements further exacerbate the challenges of delivering an activity scheduling intervention to older adults with functional impairment, limited mobility/transportation, and financial constraints.

Interventions that target social connectedness are relevant to depression prevention. People may become socially isolated for reasons unrelated to depression or behavioral avoidance patterns. However, the context of social isolation may increase vulnerability to depression through effects on rewards and stressors. For example, individuals who are socially isolated may have consequently fewer opportunities for socially-related rewards or less access to resources for managing current life stressors. Thus, BBAISC may function as a depression prevention intervention for socially isolated individuals or as a depression reduction intervention for socially isolated individuals who are also depressed.

Challenges

The use of lay providers offers opportunities for scalability, however, there may be challenges associated with this approach. While we found it was relatively easy to train these interventionists in the intervention components and fidelity requirements within a one-day training, they lacked the basic counseling skills (e.g., validation, redirection) one would obtain in a clinical degree program. Thus, it is essential that ongoing supervision focuses on introducing and reinforcing basic counseling skills. In terms of lay providers, the initial investment of training and supervision may be significant, however, after the first year they are likely to become more independent and require less frequent/intense supervision.

It can be challenging to deliver an activity scheduling intervention to older adults with functional impairment, limited mobility/transportation, and/or financial constraints. There is a balance between scheduling new activities, developing adaptations for familiar activities, and managing multiple, medical, functional, financial, and social limitations. Interventionists coach participants to discover values-aligned activities that are feasible for participants, even in situations where they experience disability, such as being wheelchair bound. In some cases, participants report they have “given up” and are reluctant to try new activities or try new ways of doing familiar activities. This underscores the important role of supervision or consultation, depending on the experience of the interventionist, to ensure that interventionists are supported to deliver the intervention effectively with fidelity and to manage their potential experiences of burn-out and/or frustration.

Future Scalability

Given the widespread problem of social isolation among older adults, factors that increase the potential scalability of our intervention are noteworthy. The BBAISC intervention: 1) Builds on a well-established, evidence-based, and widespread behavioral intervention, and 2) can be delivered by lay providers. Interventionists qualified to deliver BA for depression should easily pick up BA modified to target social connectedness. Lay providers can deliver the intervention with adequate training and ongoing support. In addition, based on our own experience, 3) The intervention screening, delivery and/or referral can be embedded successfully into routine services such as home delivered meal programs that serve at-risk older adults. Thus, BBAISC offers a scalable strategy for effectively enhancing social connectedness in isolated and lonely older adults.

Acknowledgments

Authors express their gratitude toward two community partners, the New Hampshire Coalition of Aging and Meals on Wheels Central Texas, their case managers, study interventionists, and all participants in the study. We appreciate the support of the AARP Foundation, which has identified social connectedness as a research priority.

Funding

This study received multi-year funding from the AARP Foundation (PI: M. Bruce). Additional support came from T32 MH073553 (PI: M. Bruce).

Footnotes

Approvals

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of University of Texas at Austin and Dartmouth College; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04131790

Conflict of Interest

No disclosures to report for any author.

References

- 1.Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys: Results From Two Population-Based Studies. Res Aging. 2004;26(6):655–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AARP Foundation. A national survey of adults 45 and older: Loneliness and social connections. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and aging. 2010;25(2):453–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of health and social behavior. 2009;50(1):31–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health & social care in the community. 2017;25(3):799–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donovan NJ, Wu Q, Rentz DM, Sperling RA, Marshall GA, Glymour MM. Loneliness, depression and cognitive function in older U.S. adults. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2017;32(5):564–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar A, McMunn A, Demakakos P, Hamer M, Steptoe A. Social isolation and loneliness: Prospective associations with functional status in older adults. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2017;36(2):179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(15):5797–5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosso AL, Taylor JA, Tabb LP, Michael YL. Mobility, disability, and social engagement in older adults. Journal of aging and health. 2013;25(4):617–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meek KP, Bergeron CD, Towne SD, Ahn S, Ory MG, Smith ML. Restricted Social Engagement among Adults Living with Chronic Conditions. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2018;15(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szanton SL, Roberts L, Leff B, et al. Home but still engaged: participation in social activities among the homebound. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2016;25(8):1913–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi NG, Pepin R, Marti CN, Stevens CJ, Bruce ML. Improving Social Connectedness for Homebound Older Adults: Randomized Controlled Trial of Tele-Delivered Behavioral Activation Versus Tele-Delivered Friendly Visits. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2020;28(7):698–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meals on Wheels America. About Meals on Wheels clients. 2019; https://www.mealsonwheelsamerica.org/americaletsdolunch/faqs#the-clients.

- 15.Dimidjian S, Barrera M Jr., Martell C, Muñoz RF, Lewinsohn PM. The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2011;7:1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martell CR, Dimidjian S, & Herman-Dunn R. Behavioral activation for depression: A clinician’s guide. Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lejuez CW, Hopko DR, Acierno R, Daughters SB, Pagoto SL. Ten year revision of the brief behavioral activation treatment for depression: revised treatment manual. Behavior modification. 2011;35(2):111–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewinsohn PM. A behavioral approach to depression. In: RJ Friedman MK, ed. The Psychology of Depression: Contemporary Theory and Research. New York: Wiley; 1974:157–185. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi NG, Caamano J, Vences K, Marti CN, Kunik ME. Acceptability and effects of tele-delivered behavioral activation for depression in low-income homebound older adults: in their own words. Aging Ment Health. 2020:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi NG, Wilson NL, Sirrianni L, Marinucci ML, Hegel MT. Acceptance of home-based telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults: qualitative interviews with the participants and aging-service case managers. The Gerontologist. 2014;54(4):704–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ALSWH Data Dictionary Supplement Section 2 Core Survey Dataset. 2.7 Psychosocial Variables Duke Social Support Index (DSSI). 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. Social isolation: A brief guide to the PROMIS Social Isolation instruments. 2015; http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Social_Isolation_Scoring_Manual.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2017.

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]