Abstract

Objective

In patients with partial meniscus defect, the implantation of polyurethane meniscal scaffold has become a common method for the treatment of meniscus vascular entry and tissue regeneration. However, it is unclear whether polyurethane meniscal scaffold will yield better clinical and MRI results after surgery. This meta-analysis compared the clinical and MRI results of polyurethane meniscal scaffold in some patients with meniscus defects.

Methods

By searching PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library, a systematic review of studies evaluating the clinical outcomes of patients with polyurethane meniscal scaffold implantation. The search terms used are: “meniscus”, “meniscal”, “scaffold”, “Actifit” “polyurethane” and “implant”. The study was evaluated based on the patient's reported outcome score, accompanying surgery, and radiology results. Genovese scale was used to evaluate morphology and signal intensity, and Yulish score was used to evaluate the imaging performance of articular cartilage.

Results

There were 16 studies that met the inclusion criteria, a total of 613 patients, and the overall average follow-up time was 41 months. The clinical scores at the final follow-up, such as VAS, IKDC, Tegner, and KOOS, were significantly improved compared with preoperatively. The MS, SI, and IIRMC scores evaluated in MRI showed no significant difference between preoperative and final follow-up. However, for AC (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.11–1.00; P = 0.05) and AME (OR 0.08, 95% CI 0.03–0.22; P < 0.01), the final follow-up results were worse than preoperatively.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis found that compared with preoperative, the clinical effect of the final follow-up was significantly improved. However, MS, SI, and IIRMC in MRI parameters did not change significantly. In addition, the final follow-up results of AC and AME showed a deteriorating trend. Therefore, for patients with partial meniscus defects, polyurethane meniscal scaffold seem to be a viable option, and further research is needed to determine whether the deterioration of AC and AME is clinically relevant.

Keywords: Meniscus, Scaffold, Polyurethane, Meta-analysis

Highlights

-

•

There are few clinical studies on polyurethane meniscal scaffold.

-

•

A total of 16 studies met inclusion criteria, including 613 patients.

-

•

The follow-up time was longer, 41 months on average.

-

•

MRI was used to evaluate the clinical effect.

1. Introduction

Meniscus injury1 is one of the most common injuries of the knee joint. It is more common in young adults and more men than women. In recent years, due to people's extensive participation in sports, the number of meniscus injuries has also increased significantly. Minor injuries or injuries that occur in the red area of the meniscus can be intervened by non-surgical therapies. These measures include immobilization of the long legs with plaster for 4–8 weeks and simultaneous isometric training of the quadriceps. After the plaster is removed, knee rehabilitation training is required immediately. If the non-surgical treatment fails, individualized surgical plans including meniscus suture and meniscus resection should be adopted for the type of meniscus injury.

As one of the most common orthopedic surgeries, meniscus resection2 is mainly used for severe and irreparable meniscus injuries. The purpose is to help patients relieve pain, improve knee joint function and slow down cartilage lesions. With the in-depth understanding of the function of the meniscus, more and more researchers believe that meniscus resection will cause stress concentration and load conduction disorders in the knee joint, which can develop into osteoarthritis and aggravate pain and disease.3

Therefore, in order to prevent further degeneration of the joints, the function of the meniscus should be preserved as much as possible. One method is to use a synthetic meniscal scaffold to replace the original meniscus function after meniscectomy. Moreover, when the stent is attached to the blood vessel part on the edge of the meniscus, it also provides a matrix for cell attachment and blood vessel growth.4 Currently, collagen fiber scaffolds and polyurethane (PU) meniscal scaffolds are commonly used in clinic.5 Collagen fiber is one of the most important components of the organic matter contained in the natural meniscus. After the meniscus is removed, implantation can generate new tissue without toxic side effects, and can effectively improve the clinical symptoms and clinical scores of the knee joint. However, because its mechanical properties cannot meet the requirements for maintaining the normal function of the knee joint, the scaffold is only suitable for cases where the peripheral edge of the meniscus is still intact.6 Because PU has good blood compatibility, degradation and durable mechanical strength, it has already received extensive attention in the treatment of meniscus injuries.7

Currently, there are three popular types of PU meniscal scaffold. The most widely used is Atifit® polyurethane scaffold (Orteq Ltd., UK),8 which has a pore size of 150–335 μm and a porosity of 80%. Due to the short application time of PU meniscal scaffold in the meniscus, although there have been many related clinical studies on the application of PU meniscal scaffold, there is no unified understanding of the clinical conclusions of long-term follow-up after operation. Therefore, the objectives of this meta-analysis are: Review the medium and long-term follow-up results after applying PU stent.

2. Materials and methods

Following PRISMA guidelines, a review was conducted in May 2020 using the Web of Science database. From 1949 to 2020, these searches were conducted on PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, and Web of Science databases. This study of the query words to (“ meniscus ", “meniscal”, “scaffold”, “Actifit” “polyurethane” and “implant” for any word, conjunction “and”) used in our search.

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Study type: observational case study or prospective comparative study; (2) Subjects: patients diagnosed with severe meniscus tear; (3) Intervention measures: Meniscus resection and PU stent implantation, with or without parallel operation.

Exclusion criteria: (1) PU scaffold coupled with other biological materials; (2) The follow-up time was less than 24 months and the number of cases was less than 10; (3) Letters, edited material, unpublished abstracts and manuscripts published in open access journals; (4) Repeated publications (as in the initial and final papers of a clinical trial).

2.2. Literature quality evaluation

According to the Cochrane risk assessment criteria 9, 2 researchers read the literature titles and abstracts from the retrieval strategy, and independently extracted the literature according to the pre-set inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final inclusion literature was determined by three researchers.

2.3. Data extraction and analysis

Variables recorded included variables associated with surgical outcomes, such as pain VAS, Lysholm score, IKDC score, Tegner score, KOOS, and a composite of MRI observed articular cartilage (AC) and absolute meniscus extrusion (AME). Sample size and mean and standard deviation of surgical results were recorded for each group. If there were multiple treatment groups in the study, a group with better effect was selected for quantitative analysis. Methods of data extraction, transformation and analysis are referred to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.8 If these variables are not included in the article, the study author will E-mail for further information.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Meta analysis was carried out with Review Manager 5.3 software provided by Cochrane Collaboration, and calculation and mapping were carried out with Graphpad Prism 5.1 software. Sensitivity analysis was performed by removing a study and funnel plots were made to assess publication bias. P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. General conditions of the included studies

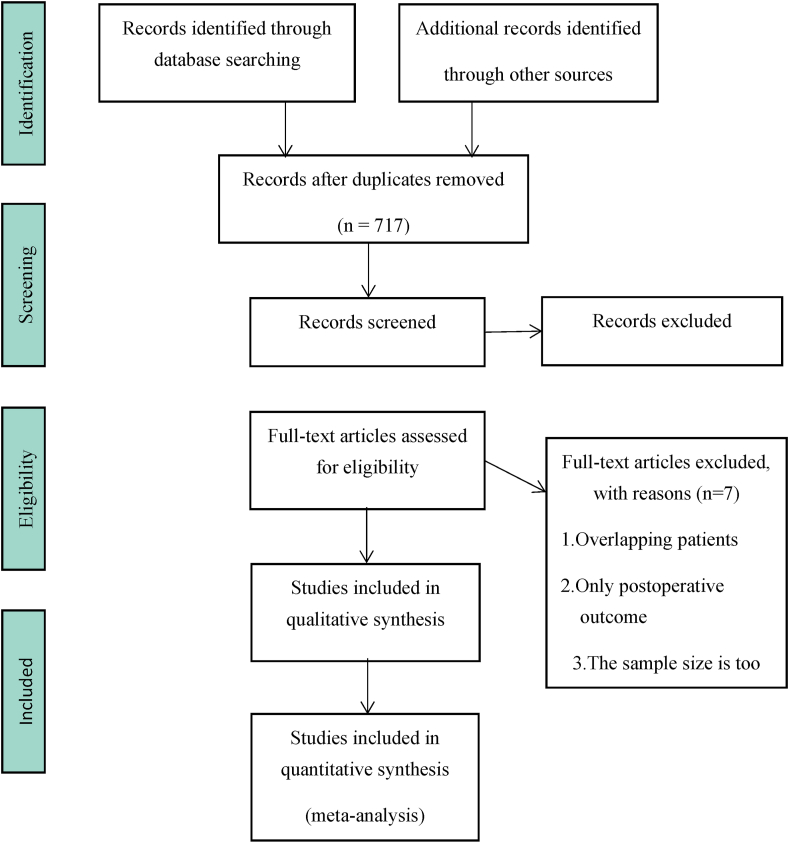

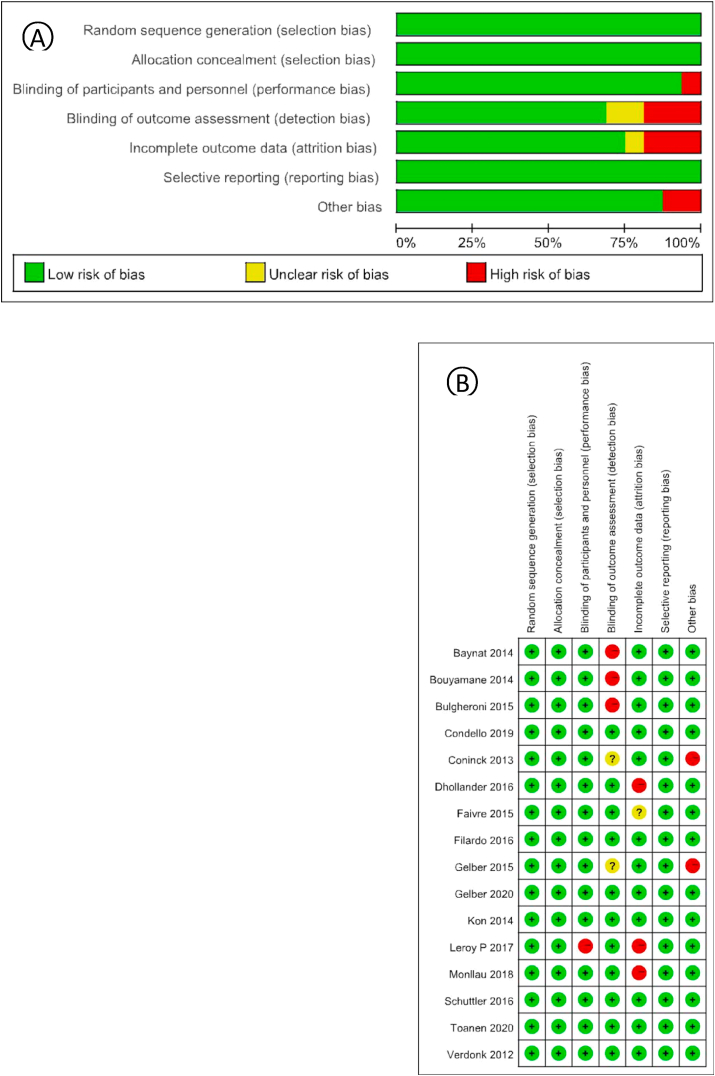

Through English database and manual retrieval, a total of 1210 literatures were obtained (Fig. 1). After screening, 16 studies were finally included for qualitative and quantitative analysis. General information of the included studies was shown in Table 1. A total of 613 patients were included, and the follow-up time ranged from 24 months to 70 months after treatment, with an average follow-up time of 40.1 months. According to the modified Jadad score, 13 of the 16 studies received scores ranging from 4 to 7, indicating high quality. The three scores ranged from 2 to 3 and were of low quality. According to the Cochrane risk assessment criteria, there were 11 cases of low bias, 3 cases of moderate bias, and 2 cases of high bias (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

General research on 16 RCTs.

| Author | Meniscus scaffold, n |

Defect size | Follow-up, mo | Patient Age, Mean 6 SD, y | Male, % | Concomitant procedures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | Lateral | ||||||

| Baynat (2014)22 | 13 | 5 | NR | 24 | 33 ± 9 | 72.2 | ACLR:6, HTO:10 |

| Bouyamane (2014)23 | 0 | 54 | 43 (32–60) | 24 | 28 ± 8 | 68.5 | DFO:4, CP:2, LBR:1 |

| Bulgheroni (2015)24 | 25 | 0 | 42.3 | 24 | 34.4 ± 11.4 | 80.0 | ACLR:9, HTO:11, CP:3 |

| Condello (2019)15,25 | 54 | 13 | NR | 36 | 40.8 ± 10.6 | 71.6 | ACLR:23, HTO:14, CP:3, PCLR:1 |

| Coninck (2013)25 | 18 | 8 | 43.2 (31.2–55.2) | 24 | 35 ± 9 | 50 | ACLR:6, HTO:1, DFO:1, ACI:1, MAT:1 |

| Dhollander (2016)14 | 29 | 15 | 45.51 (29–70) | 60 | 32.13 ± 8.48 | 54.5 | ACLR:4,HTO:4 |

| Faivre (2015)26 | 8 | 12 | NR | 24 | 28.7 ± 7.6 | / | ACLR:4, CP:3 |

| Filardo (2016)16,26 | 12 | 4 | NR | 72 | 45 ± 13 | 56.2 | ACLR:3, HTO:4, CP:7, LBR:1, LL:1 |

| Gelber (2015)27 | 40 | 14 | 42.7 (25–55) | 39 | 40.2 ± 11.4 | 77.8 | ACLR:20, PCRL:1, HTO:14, CP:17 |

| Gelber (2020)28 | NR | 45 | 41.3 ± 10.8 | 74.2 | HTO:4 | ||

| Kon (2014)29 | 13 | 5 | NR | 24 | 45.0 ± 12.9 | 61.1 | ACLR:3, HTO:4, CP:7, LBR:1, LL:2 |

| Leroy P (2017)8 | 6 | 9 | NR | 60 | 30 ± 8 | 53.3 | ACLR:5, CP:1 |

| Monllau (2018)17 | 21 | 11 | NR | 70 | 41.3 ± 11.1 | 75.7 | ACLR:8, HTO:12, PCLR:1 |

| Schuttler (2016)30 | 16 | 0 | 44.5 (35–62) | 48 | 32.5 ± 9.7 | / | None |

| Toanen (2020)31 | 101 | 54 | 39.4 ± 10.5 | 60 | 33.7 ± 10.4 | 70.3 | ACLR:29, HTO:43, CP:6 |

| Verdonk (2012)32 | 34 | 18 | NR | 24 | 30.8 ± 9.4 | 75.0 | ACLR:2 |

Med medial, Lat lateral, Mo month, Y year, ACRL anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, HTO high tibial osteotomy, DFO distal femoral osteotomy, CP cartilage procedure, LBR loose body removal, LL lateral release, ACI autologous chondrocyte implantation, MAT meniscus allograft transplantation, PCLR posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, NR not reported.

Fig. 2.

(A) Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. (B) Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.2. Operation method

All patients underwent arthroscopic partial meniscus resection and freshened some vascularized areas of meniscus injury. A meniscus ruler provided by the bracket was used to measure the gap along the peripheral edge. The stent was cut open with blunt forceps and the knee was inserted through anterolateral or anterolateral approaches and sutured to the original position of the meniscus. According to the different suture locations and the experience and preferences of the surgeon, three different suture methods, internal, external, and external, were used to fix the meniscal scaffold.

3.3. Characteristics of patients and lesions

613 patients were treated. The average follow-up time in the included study was 45 months and the average age of the patients was 36 years. Only two studies did not report gender; the rest included 398 men and 178 women who received treatment, 60% of whom were men. Five studies reported body mass index (BMI), with an average of 25 (Table 1).

3.4. Report the results

The most commonly reported outcomes are the pain visual simulation score (VAS), Lysholm score, Tegner activity score, subjective International Knee Literature Committee (IKDC) score, and knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS).

Sixteen studies performed concurrent surgery (Table 1). The most common concurrent procedure is anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). The second most common concomitant surgery is high tibial osteotomy (HTO), followed by microfracture surgery.

Clinical results (Lysholm Score, IKDC Score, VAS for Pain, Tegner Score, and KOOS).

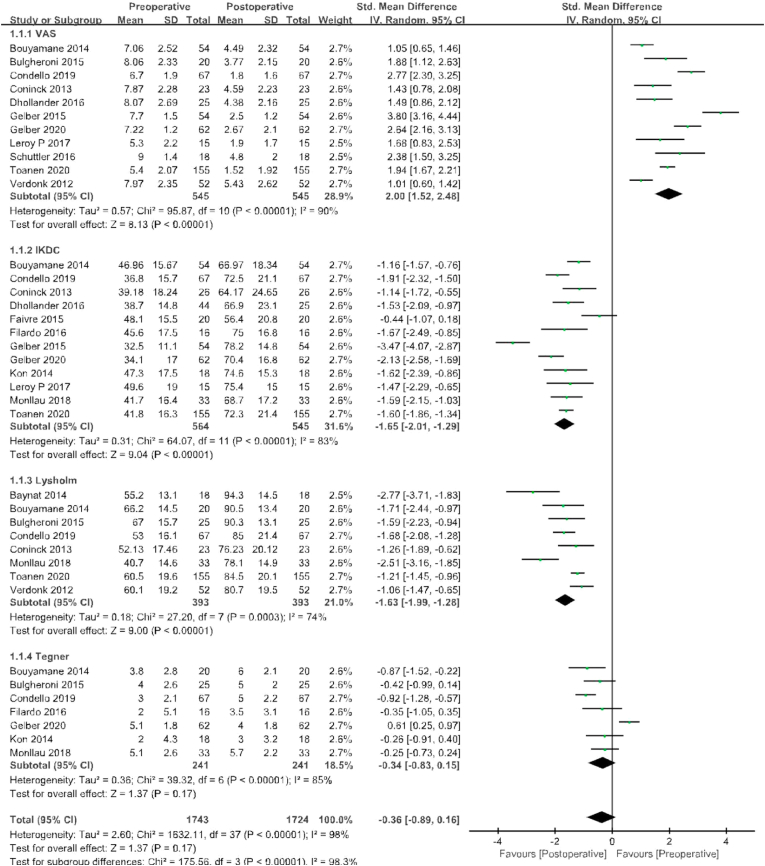

VAS pain scores were reported in 11 of the 16 studies, with 545 patients before surgery and at the last follow-up. The standard mean value at the final follow-up was 2.00 points lower than that before surgery, with significant differences between groups (95% CI 1.52 to 2.48 points; P < 0.00001; I2 = 90%, Fig. 3); Lysholm scores were compared in eight studies with 393 patients before surgery and at the last follow-up. The standard mean value at the final follow-up was 1.63 points higher than that before surgery, with significant differences between groups (95% CI −1.99 to −1.28 points; P < 0.00001; I2 = 74%, Fig. 3); The IKDC score was compared in 12 studies that included 564 patients before surgery and a total of 545 patients at final follow-up. The standard mean value at the final follow-up was 1.65 points higher than that before surgery, with significant differences between groups (95% CI −2.01 to −1.29 points; P < 0.00001; I2 = 83%, Fig. 3); Seven studies compared the Tegner score between the two groups, with 241 patients before surgery and at the last follow-up. The standard mean value at the final follow-up was 0.34 points higher than that before surgery, with significant differences between groups (95% CI −0.83 to 0.15 points; P < 0.00001; I2 = 85%, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Results of aggregate analysis for comparison of Lysholm score, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, visual analogue scale (VAS) score, and Tegner score between at baseline and at final follow-up.

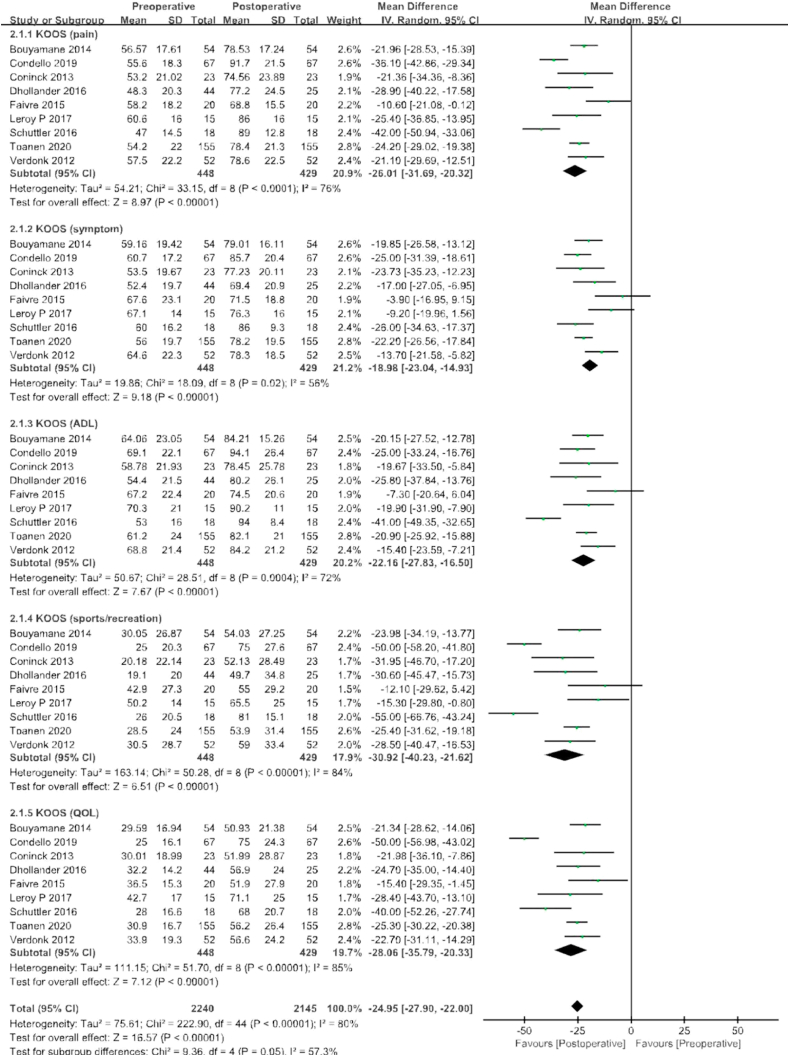

KOOS scores were included in a total of nine studies, including 448 patients before surgery and 429 patients with final follow-up after surgery. These studies incorporated subgroup analyses of pain, symptoms, ADL, sports/Recreation, and quality of life for KOOS scores, respectively, with a combined mean difference that was 24.95 points higher at final follow-up than before surgery (95% CI −27.9 to 22.0 points; P < 0.00001; I2 = 80%, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Results of aggregate analysis for comparison of Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcomes Score (KOOS) between at baseline and at final follow-up, including subgroup analysis by pain, symptoms, activities of daily living (ADL), sport/recreation.

3.5. MRI outcomes (AC status, AME, MS, SI, and IIRMC)

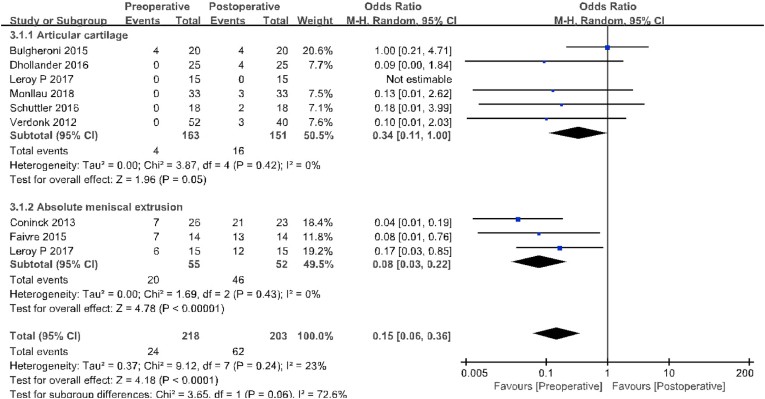

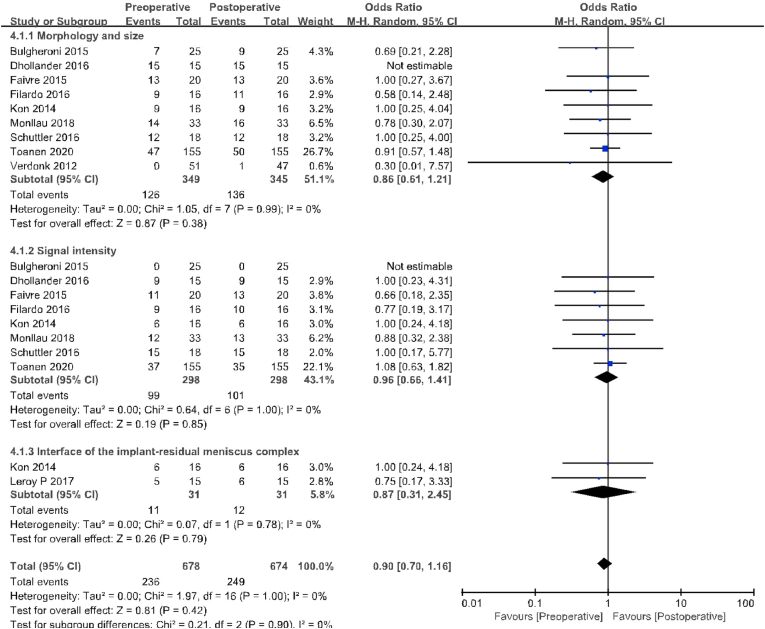

Of the 16 included studies, a total of six compared AC status, including 163 patients preoperatively and 151 patients at final follow-up for MRI evaluation. At the final follow-up, the ratio of patients at Yulish or ICRS 3 appeared cases (16/151) were significantly higher than those before surgery (4/163; OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.11–1.00; P = 0.05; I2 = 0%, Fig. 5). AME was reported in three studies with 55 patients preoperatively and 52 with MRI evaluation at final follow-up. At the final follow-up (46/52), the proportion of patients with 3 mm or greater compression in coronal MRI was significantly higher than at baseline (20/55;OR 0.08,95%CI 0.03–0.22; P < 0.01; I2 = 0%, Fig. 5). In addition, nine studies compared MS, including 349 patients before surgery and 345 patients at final follow-up. The proportion of patients with Genovese level 1 or 2B is similar between the two groups (Preoperative, 126/349; fnal follow-up, 136/345; OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.61–0.21; P = 0.38; I2 = 0%, Fig. 6). Eight studies (including 298 patients who underwent preoperative and final follow-up MRI evaluation) reported SI. The proportion of patients with Genovese level 1 is similar between the two groups (Preoperative, 99/298; fnal follow-up, 101/298; OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.66–1.41; P = 0.85; I2 = 0%, Fig. 6). Both studies reported IIRMC with 31 patients before and during final follow-up. Preoperative patients with gaps between the two groups are similar (Preoperative, 11/31; fnal follow-up, 12/31; OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.31–2.45; P = 0.42; I2 = 0%, Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Results of aggregate analysis for comparison of articular cartilage (AC) and absolute meniscal extrusion (AME) between at baseline and at fnal follow-up.

Fig. 6.

Results of aggregate analysis for comparison of morphology and size (MS), signal intensity (SI) of meniscal implant, and interface of the implant–residual meniscus complex (IIRMC) between at baseline and at final follow-up.

4. Discussion

This article mainly analyzes the mid-term clinical effects of PU meniscal scaffold in meniscus resection. The analysis methods include clinical outcome scores and MRI parameters. Compared with preoperative, the clinical effect of final follow-up was significantly improved. However, MS, SI, and IIRMC in MRI parameters did not change significantly. In addition, the final follow-up results of AC and AME showed a deteriorating trend.

The meniscus is very important to the biomechanical function of the knee joint, and the loss of meniscus tissue will lead to a decline in clinical function and activity levels.10 Although meniscus transplantation11 can improve the clinical efficacy of patients, complications such as immune response and infection lead to a higher reoperation rate and failure rate. Therefore, the meniscus stent can be used as an alternative to meniscus replacement by reducing the risk of inflammation and immune response. The PU meniscal scaffold is designed to provide mechanical support for the knee joint and slowly degrade as the stent is replaced by regenerated tissue within 5 years.8

After the patient received the PU meniscal scaffold implantation, the biggest change was the relief of the knee joint pain caused by the meniscus tear.12 This is especially evident in the VAS score. The pain was significantly relieved within 6 months after the operation. Although the VAS score gradually increased from 2 years after the operation, the standard average value at the last follow-up was still 2.00 points lower than before the operation. In addition, Tegner and IKDC subjective scores and KOOS subscales have also been continuously improved. Since the current study has not provided follow-up for more than 5 years, there is currently no long-term data on this PU meniscal scaffold.

There are obvious differences in anatomy and function between the medial and lateral meniscus.13 Different authors have tried to evaluate whether this may be reflected in the different results of meniscus tears. Dhollander's14 study found that the PU meniscal scaffold has a 62.2% overall implant survival rate, and the medial meniscus is higher than the lateral meniscus. This may be due to the higher stress of the lateral meniscus than the medial meniscus. In addition, this study found that a large number of patients undergoing meniscus stent implantation are accompanied by other operations, such as HTO, ACLR, etc. This may explain the poor clinical results of PU meniscal scaffold implantation. As reported by Condello,15 patients who underwent ACL reconstruction and implanted scaffold during follow-up had more bone marrow edema and lower Lysholm score. Filardo16 believes that when simultaneous surgery is required, recovery is slower in the short term. However, in the case of longer follow-up time, whether it is an isolated or more complicated part of the meniscus, similar good results were finally obtained.

In the studies included in this systematic review, some researchers evaluated the shape and strength of the stent based on MRI. As a result, the signal strength of the observed stent is still increased compared with the normal meniscus, and the size is slightly reduced. Monllau17 also observed that the stent was even completely absorbed in 3 patients at the last follow-up. However, the clinical results after PU meniscal scaffold implantation are not always proportional to meniscus extrusion, and are often better than MRI prompts. However, Leroy8 found that there is a correlation between the amount of squeezing before and after the operation. When there is more squeezing before surgery, there are more squeezing after surgery. Therefore, it can be considered that the presence of preoperative compression may be considered as a contraindication for the implantation of a PU meniscal scaffold.

Another expected advantage of the meniscus stent is the potential chondroprotective effect.18,19 There is no general consensus in the current literature on the protective effect of the meniscus stent on cartilage. Two groups of factors may be related to the progress of the articular cartilage state after the PU meniscal scaffold transplantation20: one group is the difference in surgical skills, while the other group is inevitable and has nothing to do with the surgical technique. These previous factors are related to the condition of the articular cartilage before surgery and have a negative impact on the results of PU meniscal scaffold implantation, suggesting that the level 2 defined by the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) should be a contraindication for PU meniscal scaffold implantation.5 The results of this meta-analysis did not support the previous results, and the baseline state of articular cartilage deteriorated significantly at the final follow-up. Based on the current meta-analysis, ICRS grade 3 articular cartilage baseline status, meniscus defect size of 4.5 cm, and accurate measurement of PU meniscal scaffold (including the recommended 10% oversize) may relieve pain in patients receiving PU meniscal scaffold implants And improve the function effectively.

One development direction of the meniscal scaffold is to introduce cells and biologically active molecules into the implant,21 so that extracellular matrix is generated in the scaffold, and finally the meniscus tissue is formed. Once this goal is achieved, we can fully and effectively replace the original meniscus with implants.

There are several limitations to this study. All the studies included in this meta-analysis are observational studies, prone to systematic and random errors, and there is a certain inherent heterogeneity. In addition, the heterogeneity of the included studies can be explained by subtle differences in other factors that affect the clinical outcome, including the use of multiple surgical techniques, differences in postoperative MRI function and pain scores, and differences in time points.

5. Conclusion

This meta-analysis found that compared with preoperative, the clinical effect of the final follow-up was significantly improved. However, MS, SI, and IIRMC in MRI parameters did not change significantly. In addition, the final follow-up results of AC and AME showed a deteriorating trend. Therefore, for patients with partial meniscus defects, PU meniscal scaffold seem to be a viable option, and further research is needed to determine whether the deterioration of AC and AME is clinically relevant.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Source of funding

No funding was provided when conducting the review.

Author contribution

The research concept or design is mainly completed by Denghui Xie, Chun Zeng and Jianshan Guo, the data collection and data analysis or interpretation are mainly completed by Jianying Pan, Jintao Li and Li Wei. They are made the equal contribution.

Guarantor

Dr Denghui Xie.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgement

No preregistration exists for the reported studies reported in this article.

Contributor Information

Jinshan Guo, Email: jsguo4127@smu.edu.cn.

Chun Zeng, Email: zengdavid@126.com.

Denghui Xie, Email: xiedenghui221122@smu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Gee S.M., Tennent D.J., Cameron K.L., Posner M.A. The burden of meniscus injury in young and physically active populations. Clin Sport Med. 2020;39:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goebel L., Reinhard J., Madry H. [Meniscal lesion. A pre-osteoarthritic condition of the knee joint] Orthopä. 2017;46:822–830. doi: 10.1007/s00132-017-3462-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faucett S.C., Geisler B.P., Chahla J. Meniscus root Repair vs meniscectomy or nonoperative management to prevent knee osteoarthritis after medial meniscus root tears: clinical and economic effectiveness. Am J Sports Med. 2018;47:762–769. doi: 10.1177/0363546518755754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruprecht J.C., Waanders T.D., Rowland C.R. Meniscus-derived matrix scaffolds promote the integrative Repair of meniscal defects. Sci Rep (UK) 2019;9:8713–8719. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44855-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houck D.A., Kraeutler M.J., Belk J.W., McCarty E.C., Bravman J.T. Similar clinical outcomes following collagen or polyurethane meniscal scaffold implantation: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26:2259–2269. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-4838-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lubowitz J.H. Editorial commentary: collagen meniscal scaffolds. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2015;31:942–943. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Achatz F.P., Kujat R., Pfeifer C.G. Vitro testing of scaffolds for mesenchymal stem cell-based meniscus tissue engineering-introducing a new biocompatibility scoring system. Materials. 2016;9 doi: 10.3390/ma9040276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.P AL . 2017. Actifit® Polyurethane Meniscal Scaffold: MRI and Functional Outcomes after a Minimum Follow-Up of 5 Years. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.JPT Higgins, J Thomas, J Chandler. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0. 2019. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melrose J. The importance of the knee joint meniscal fibrocartilages as stabilizing weight bearing structures providing global protection to human knee-joint tissues. Cells. 2019;8:324. doi: 10.3390/cells8040324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figueroa F., Figueroa D., Calvo R., Vaisman A., Espregueira-Mendes J. Meniscus allograft transplantation: indications, techniques and outcomes. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4:115–120. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vedicherla S., Romanazzo S., Kelly D.J., Buckley C.T., Moran C.J. Chondrocyte-based intraoperative processing strategies for the biological augmentation of a polyurethane meniscus replacement. Connect Tissue Res. 2018;59:381–392. doi: 10.1080/03008207.2017.1402892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Culvenor A.G., Oiestad B.E., Hart H.F., Stefanik J.J., Guermazi A., Crossley K.M. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis features on magnetic resonance imaging in asymptomatic uninjured adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:1268–1278. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhollander A.A., Verdonk P., Verdonk R.E. Treatment of painful irreparable partial meniscal defects with a polyurethane scaffold: mid-term clinical outcome and survival analysis. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2016;33:e39–e40. doi: 10.1177/0363546516652601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Condello V., Dei Giudici L., Perdisa F. Polyurethane scaffold implants for partial meniscus lesions: delayed intervention leads to an inferior outcome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05760-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filardo G., Filardo G., Kon E. Polyurethane-based cell-free scaffold for the treatment of painful partial meniscus loss. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:459–467. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monllau J.C., Poggioli F., Erquicia J. Magnetic resonance imaging and functional outcomes after a polyurethane meniscal scaffold implantation: minimum 5-year follow-up. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2018;34:1621–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein S., Hose S., Warnecke D. Meniscal replacement with a silk fibroin scaffold reduces contact stresses in the human knee. J Orthop Res. 2019;37:2583–2592. doi: 10.1002/jor.24437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong C.C., Kuo T.F., Yang T.L. Platelet-rich fibrin facilitates rabbit meniscal Repair by promoting meniscocytes proliferation, migration, and extracellular matrix synthesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18081722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin Y., Lee H., Sim H., Kim H., Lee D. Polyurethane meniscal scaffolds lead to better clinical outcomes but worse articular cartilage status and greater absolute meniscal extrusion. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26:2227–2238. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4650-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pereira H., Fatih C.I., Gomes S. Meniscal allograft transplants and new scaffolding techniques. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4:279–295. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baynat C., Andro C., Vincent J.P. Actifit® synthetic meniscal substitute: experience with 18 patients in Brest, France. J Orthop Traumatol: Surg Res. 2014;100:S385–S389. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouyarmane H., Beaufils P., Pujol N. Polyurethane scaffold in lateral meniscus segmental defects: clinical outcomes at 24 months follow-up. J Orthop Traumatol: Surg Res. 2014;100:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bulgheroni E., Grassi A., Campagnolo M., Bulgheroni P., Mudhigere A., Gobbi A. Comparative study of collagen versus synthetic-based meniscal scaffolds in treating meniscal deficiency in young active population. Cartilage. 2015;7:29–38. doi: 10.1177/1947603515600219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Coninck T. Two-year follow-up study on clinical and radiological outcomes of polyurethane meniscal scaffolds. Wild Environ Med. 2012;26:434–435. doi: 10.1177/0363546512463344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faivre B., Bouyarmane H., Lonjon G., Boisrenoult P., Pujol N., Beaufils P. Actifit® scaffold implantation: influence of preoperative meniscal extrusion on morphological and clinical outcomes. J Orthop Traumatol: Surg Res. 2015;101:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelber P.E., Petrica A.M., Isart A., Mari-Molina R., Monllau J.C. The magnetic resonance aspect of a polyurethane meniscal scaffold is worse in advanced cartilage defects without deterioration of clinical outcomes after a minimum two-year follow-up. Knee. 2015;22:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelber P.E., Torres-Claramunt R., Poggioli F., Perez-Prieto D., Monllau J.C. Polyurethane meniscal scaffold: does preoperative remnant meniscal extrusion have an influence on postoperative extrusion and knee function? J Knee Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kon E., Filardo G., Zaffagnini S. Biodegradable polyurethane meniscal scaffold for isolated partial lesions or as combined procedure for knees with multiple comorbidities: clinical results at 2 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22:128–134. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2328-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schüttler K.F., Haberhauer F., Gesslein M. Midterm follow-up after implantation of a polyurethane meniscal scaffold for segmental medial meniscus loss: maintenance of good clinical and MRI outcome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:1478–1484. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toanen C., Dhollander A., Bulgheroni P. Polyurethane meniscal scaffold for the treatment of partial meniscal deficiency: 5-year follow-up outcomes: a European multicentric study. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48:1347–1355. doi: 10.1177/0363546520913528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verdonk P. Successful treatment of painful irreparable partial meniscal defects with a polyurethane scaffold two-year safety and clinical outcomes. Wild Environ Med. 2012;26:434–435. doi: 10.1177/0363546511433032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]