Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a viral pneumonia that can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Until the commercialization of a vaccine, pharmacological treatment still represents an important strategy to fight against the ongoing pandemic. Glucocorticoids (GC) were widely used in the past coronavirus pandemics and have been used against the coronavirus 2 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2). This article aimed to review the studies that described the treatment with GC in COVID-19 patients. Randomized or nonrandomized clinical trials and retrospective or prospective-controlled longitudinal studies were screened for this systematic review. Studies in English, Portuguese, and Spanish published since 2019, with participants of any clinical status, geographic location, age, and sex were included. The most significant interest was related to the length of stay, radiological profile changes, viremia, and mortality. The research was done electronically on the Pubmed database using the following terms: "corticosteroids", "glucocorticoids", "dexamethasone", "methylprednisolone", "COVID-19", "SARS- CoV-2", "ADRS". We identified 6332 publications, and at the end, 14 retrospective observational studies that met all the inclusion criteria were selected. These studies included only patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 confirmed by RT-PCR, involving 2,713 participants. The results showed great heterogeneity in their designs and results, which precludes a reliable conclusion on the use of GCs in the treatment of COVID-19.

Keyword: Glucocorticoids, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, ARDS, Treatment

Introduction

Since December 2019, the world began to watch a new outbreak of pneumonia. The disease had an initial unknown cause and started in Wuhan, China. Subsequent investigations discovered that the agent was a new type of coronavirus (n-cov) [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) cataloged this virus as 2019-nCOV, and on March 11th, 2020, the disease has declared an epidemic.

2019-nCov is a ß-coronavirus that belongs to the family of coronavidae, being one of the seven types of coronavirus which can affect humans. This virus has a simple positive-sense RNA genome (+ ssRNA) and the lower respiratory system is the initial site of 2019-nCov infection and replication [2].

Nowadays, it is known that acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is the leading cause of death inherent in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The overexpression of inflammatory cytokines in the cytoplasm of infected cells may indicate that the immune mechanism is responsible for this syndrome. This overexpression has been named cytokine storm and is caused by the serum increase of interleukin 1B (IL-1B), interferon-gamma (IFN-y), monocyte chemoattracting protein 1 (MCP-1), and interleukin-6 (IL-6). IL-6 has been used as a marker of the disease severity due to the fact of critically ill patients in intensive care units since have presented higher levels of IL-6, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) (ICU) [3].

Several interventions have been tested throughout more than 1500 types of randomized clinical trials, such as the use of antimalarials, plasmaphereses, antivirals, anticoagulants, immunobiologics, and glucocorticoids (GCs) [4–8]. This kind of treatment aims to prevent the progress of the disease and improve the prognosis of patients.

GCs were widely used as immunomodulators during the 2002–2004 SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) outbreak because once used in the early stages of the disease, they improve the pulmonary oxygenation, decrease the fever, and consequently, the hospital stay and mortality [3]. Altogether, this evidence led to the study of using this class of drugs in the epidemic of SARS-CoV-2.

The use of these steroids is suggested to be useful for patients who have a high inflammatory response and an increased risk of developing ARDS, or who are in the early stage of the cytokine storm [3, 9–11].

GCs act by modulating gene transcription, preventing negative regulation of the inducible nitric oxide synthase genes, and promoting the decrease of cytokine production and inhibition of the phospholipase A2 enzyme. This set of alterations lead to a consequent reduction in the synthesis of prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and platelet-activating factor, essential substances in the inflammatory process. A possible interaction between the GC and the NF-κb transcription factor has been also investigated, unveiling a possible alternative pathway for the regulation of the expression of several components of immune system, leading to anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects [9, 11].

Nevertheless, the use of GC must be judicious despite its benefits. The administration of GCs in large doses may delay the clearance of the respiratory tract virus and increase the risk of secondary infections in addition to inducing high complication rates [10]. In this sense, this article aimed to systematically review the studies that described the use of GC in patients with COVID-19 and to provide a safer analysis of the effectiveness and recommendations for GC use.

Materials and methods

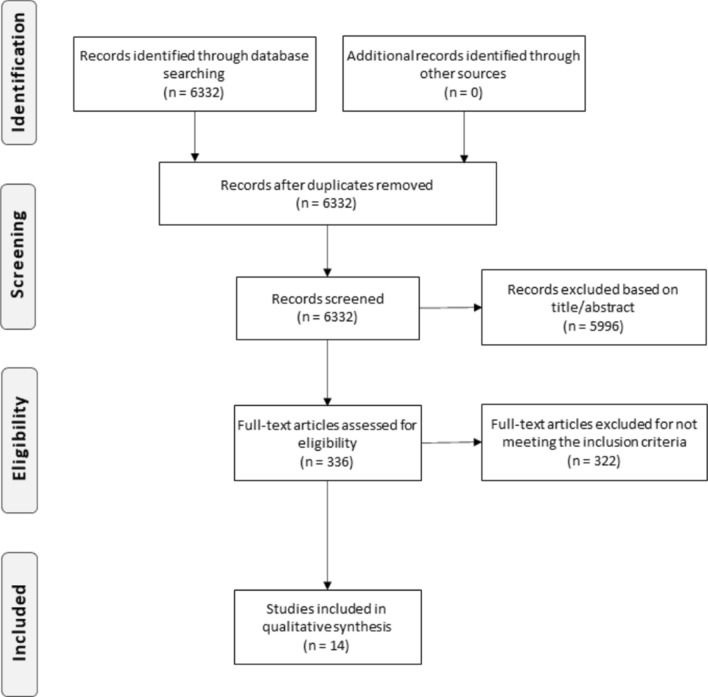

A systematic review was carried out on the use of GC in cases of COVID-19, for which the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) were used [12]. The New Castle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used for the analysis and methodology of longitudinal studies. For the randomized clinical trials, the Jadad scale was chosen.

Randomized or nonrandomized clinical trials and retrospective or prospective-controlled longitudinal studies were screened for this systematic review. Studies in English, Portuguese, and Spanish published since 2019, with participants of any clinical status, geographic location, age, and sex were included. Case–control studies, case reports, reviews, and texts in different languages than those cited as inclusion factors and not yet published were not included.

The review focused the discussion on several aspects considered more significant such as the length of stay, changes in the radiological profile, viremia, serum cytokine levels, clinical status, and mortality. The choices took into account the emergency of this review due to the current pandemic and the commitment to presenting reliable data to the reader.

The research was performed electronically accessing the Pubmed database. A daily alert was created on Pubmed for the search of the following terms: "corticosteroids," "glucocorticoids," "dexamethasone," "methylprednisolone," "COVID-19", "SARS-CoV-2", "ADRS." The result of the research can be consulted in Fig. 1. The date of the first survey was 31/05/2020, and the last one was made on 21/07/2020.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

The primary analysis of the articles was carried out independently by two authors (L and E) by reading the titles and abstracts. The studies that met the inclusion criteria were read in full by the authors (L and E), and those that did not present any new evidence to justify their withdrawal were used in this review. Any questions about the inclusion of these articles were discussed between the authors (L and E) and a third author (D) in search of a consensus.

Results

We identified 6332 publications, and at the end, 14 retrospective observational studies that met all the inclusion criteria were selected (Tables 1 and 2). Twelve studies were performed in China [13–26], 1 in Spain [25], and 1 in the United States [26]. The articles included only patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 confirmed by RT-PCR, involving 2713 participants. There was variation in the severity of the disease presented by the participants in the different studies regarding the protocol, record, and type of GC used. The score obtained on the NOS scale for the analysis of possible bias in observational studies was ranging from 4 to 8. The short follow-up time was the main limiting factor observed.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the studies included

| Study ID | Design | Country | Site | NOS/Jaded score | Age (I vs. C) | N (used GC vs. didn't use GC) | Gender Male/Total (I vs. C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guan | Cohort | China | Multi- center | 5 |

Severe: 52.0 (40.0–65.0) Nonsevere: 45.0 (34.0–57.0) |

204; 895 | Severe: 100/173 Nonsevere: 537/923 |

| Yang | Cohort | China | Single center | 6 |

Survivors: 51·9 (12·9) Nonsurvivors: 64·6 (11·2) |

30; 22 | Survivors: 14/20 Nonsurvivors: 21/32 |

| Zhou | Cohort | China | Two centers | 6 |

Survivors: 52·0 (45·0–58·0) Nonsurvivors: 69·0 (63·0–76·0) |

57; 134 | Survivors: 81/137 Nonsurvivors: 38/54 |

| Cao | Cohort | China | Single center | 6 |

Survivors: 53 (47-66) Nonsurvivors: 72 (63-81) |

51; 51 | Survivors: 40/85 Nonsurvivors: 13/17 |

| Salacup | Cohort | USA | Single center | 6 |

Survivors: 64.08±15.07 Nonsurvivors: 73.15±11.01 |

55; 187 | Survivors: 96/190 Nonsurvivors: 27/52 |

| Li | Cohort | China | Single center | 6 |

Survivors: 62 (53-70) Nonsurvivors: 71 (69-77) |

70; 4 | Survivors: 33/60 Nonsurvivors: 11/14 |

| Zha | Cohort | China | Two centers | 8 |

Corticosteroid: 53 (36–57) Noncorticosteroid: 37 (27–52) |

11; 20 |

Corticosteroid: 8/11 Noncorticosteroid: 12/20 |

| Wang | Cohort | China | Single center | 8 |

Corticosteroid: 54(48,63) Noncorticosteroid: 53(48,63) |

26; 20 |

Corticosteroid: 16/26 Noncorticosteroid: 10/20 |

| Gong | Cohort | China | Single center | 4 |

Corticosteroid: 38.22 ± 8.95 Noncorticosteroid: 33.75 ± 7.80 |

18; 16 |

Corticosteroid: 11/18 Noncorticosteroid: 11/16 |

| Cruz | Cohort | Spain | Single center | 7 |

Corticosteroid: 65.4 (12.9) Noncorticosteroid: 68.1 (15.7) |

396; 67 | Corticosteroid: 276/396 Noncorticosteroid: 41/67 |

| Fang | Cohort | China | Single center | 7 |

Corticosteroid: General group − 40.2±12.6. Severe group − 60.6±13.6 Noncorticosteroid: General group -− 39.9±15.5. Severe group − 54.3±15.4 |

25; 53 |

Corticosteroid: General group—5/9. Severe group—12/16 Noncorticosteroid: General group—22/46. Severe group—5/7 |

| Wu | Cohort | China | Single center | 6 |

Without ARDS: 48.0 (40.0–54.0) With ARDS: 58.5 (50.0–69.0) |

62; 139 |

Without ARDS: 68/117 With ARDS: 60/84 |

| Shang | Cohort | China | Multi- center | 6 |

Survivors: Common − 46·0(33·0–56·0). Severe – 50.0(38·0–60.0) Death: 67.0(61.0–77.0) |

196; 220 |

Survivors: Common—89/226. Severe - 77/139 Death: 31/51 |

| Xu | Cohort | China | Two centers | 6 |

< 15 days to viral clearance: 48 (34, 61) 15 days to viral clearance: 54.5 (45, 63) |

64/49 | < 15 days to viral clearance: 15/37 > 15 days to viral clearance: 51/76 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Cohort studying the efficacy of corticosteroids in patients with COVID-19

| Study ID | Severity of disease | Type, dose, and duration | Outcome | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guan | Severe/ Nonsevere | Systemic glucocorticoids | Admission to an (ICU), the use of mechanical ventilation, or death | The higher percentage among those without the outcome |

| Yang | Critically ill | Glucocorticoids | 28-day mortality after ICU admission | The higher percentage among those without the outcome |

| Zhou | All | Corticosteroids | Mortality | The higher percentage among those with the outcome with statistical difference |

| Cao | All | Methylprednisolone Sodium Succ | Mortality | The higher percentage among those with the outcome but no statistical difference |

| Salacup | All | Steroids | Mortality | The higher percentage among those with the outcome with statistical difference |

| Li | Severe and critical | Corticosteroids | Mortality | The higher percentage among those without outcome but no statistical difference |

| Zha | Mild | 40 mg methylprednisolone once or twice per day within 24 h of admission for a median of 5 days | Time to virus clearance | No statistically significant differences in virologic or clinical outcomes between patients who received and those who did not receive corticosteroid |

| Wang | Severe | Methylprednisolone treatment with the dosage of 12 mg/kg/d for 5–7 days | Clinical, laboratory, and radiological improvement | Better statistically significant improvement among those who received methylprednisolone in the duration of fever, Sp02, and absorption degree of the focus in chest CT |

| Gong | All | Methylprednisolone as 1–2 mg/kg/d inthe initial dose and gradually halved every 3 days, total treating course range from 5 to 10 days | Viral genomic nucleicacid negative conversion and CT imaging lesion absorption | No statistical difference in the CT imaging lesionabsorption in both 2 groups but the shorter time needed to viral genomic nucleic acid negative conversion in the methylprednisolone group |

| Cruz | COVID-19 patients complicated with ARDS and/or a hyperinflammatory syndrome | 1 mg/kg/day methylprednisolone or equivalent, and steroid pulse | In-hospital mortality | In-hospital mortality was lower in patients treated with steroids than in controls |

| Fang | General and severe | Oral methylprednisolone, 237.5 mg/day for a median duration of 7 days in the general group. Intravenous methylprednisolone, 250.0 mg/day for a median duration of 4.5 days in the severe group | Time to virus clearance | No significant difference identified in both patients in the general group and patients in the severe group |

| Wu | All | Methylprednisolone | Development of ARDS and death among those with ARDS | Patients who developed ARDS were more likely to be treated with methylprednisolone, and the administration of methylprednisolone appears to have reduced the risk of death in patients with ARDS |

| Shang | All | Methylprednisolone, prednisone acetate, and dexamethasone | Hospitalization time and clinical and laboratory changing | Survivors who received corticosteroid therapy had a longer duration of hospitalization and there was a significant recovery of lymphocyte counts after corticosteroid therapy for the survivors but not for the patients who died |

| Xu | All | Corticosteroids | Time to virus clearance | The higher percentage among the > 15 days to virus clearance group with statistical difference |

The evaluated outcomes showed considerable heterogeneity, such as changes in clinical, radiological, or laboratory status, duration of hospital stay, time for viral clearance, and mortality. The interpretation of the results obtained in some studies was limited by the absence or insufficiency of statistical data. Due to the significant variability and limitations, the results obtained regarding the consequences of using GCs were eventually inconclusive or diverging, as further discussed.

Discussion

Although the use of GC has been widely discussed during the epidemics of SARS and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), the safety and efficacy of this pharmacological class are still controversial for the treatment of several diseases. Evidence found in systematic reviews suggests that GCs administration in patients with SARS is associated with increased plasma viral load and slower viral clearance, contributing to immunosuppression states [27–30]. In patients with MERS, no association was found between the use of GCs and increased mortality. However, a delay in the clearance of MERS-CoV RNA was reported [27, 29, 30]. Overall, studies indicate that the use of GCs, did not have an impact on reducing the number of deaths; the service led to a prolonged hospital stay, ICU admission rates, or the use of mechanical ventilation, as well as the appearance of acute adverse effects [30].

A cohort found that all patients had a significant increase in the viral load of SARS-CoV in the body; however, there was a considerable reduction in IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 in patients with 7–10 days of treatment with GCs, coinciding with the improvement of the clinical and radiological situation [31]. Another cohort identified a higher mortality rate in patients treated with GCs with no lung damage, indicating that this pharmacological class's early use would significantly increase the viral load [32].

In a clinical trial in which two groups of patients with MERS were compared, corticosteroid therapy was administered in only one of the groups. It was observed that the group treated with GCs was more likely to need the use of mechanical ventilation, administration of nitric oxide, the administration of neuromuscular blockers, vasopressors, blood transfusion, and renal replacement therapy, in addition to having delayed viral clearance [33]. Loutfy et al. observed that among 13 patients diagnosed with SARS treated with single corticosteroid therapy, five were transferred to the ICU, three were intubated and underwent mechanical ventilation, and one patient died [34]. Lee et al. observed the early administration (< 7 days since the fever onset) of hydrocortisone in 9 patients with SARS and concluded that the expression of SARS-CoV RNA was significantly higher in the hydrocortisone group compared with the placebo group [35].

Our analysis of studies using GC in the treatment of COVID-19 patients must be interpreted with great caution. Due to the emergency of immediate responses that can guide medical conduct, we collected as much data as possible on this subject, which leads to a grouping of studies with significant differences regarding the status of the selected patients, GC dosage, the period of use, outcome and analyzes used to the data obtained. Another important fact is that all studies obtained are observational and retrospective, preventing the careful choice of who will or will not receive the medication. As GC tends to be used for more severe patients, the interpretation of such outcomes may be subject to selection bias. For this reason, it is not possible to ensure that the criteria for administration of GC were pre-established or based on a worsening of the clinical status, admission to the ICU, changes in the laboratory, or radiological data.

By stratifying the interpretation of results according to the type of outcome, we can draw more secure conclusions associated with a careful individual analysis of the articles. Among the eight articles that evaluated mortality as an outcome [13, 16, 18, 19, 22, 24–26]; two did not present statistical analysis and, therefore, were not included in the discussion [18, 24]. Despite expressing the p value attached to the table, two cohorts did not show significance between the variables, thereby not inserted as well [13, 19]. Regarding the remaining four studies, two of them included patients in any disease state and found results against the use of GC [16, 26]. Cruz et al. included only critically ill patients. They used GC administration as exposure, bringing a more robust conclusion and having the highest note in the NOS score among those included [25]. In this study, mortality was lower in the group that used CG. Wu et al. observed the development of ARDS and mortality among those with ARDS in hospitalized patients. They concluded that the use of methylprednisolone was more significant in the group that developed ARDS. Nevertheless, the use of this GC among the ARDS group appears to have reduced the risk of death. Still, this latter result did not obtain statistical significance [22].

Four articles analyzed the time to viral clearance [14, 15, 17, 23]. Of these, only one obtained a significant result [23]. The cohort included patients in any condition and concluded that GCs were more often used in the group that took longer to certify a viral clearance. Finally, two articles analyzed clinical changes [20, 21]. Wang et al. included only critically ill patients and observed results in favour of the use of methylprednisolone. Shang et al. included patients in any condition and used three different GC and observed, among the survivors, more extended hospital stay in the group that received GC and a significant recovery in the lymphocyte count among those who received the medication and survived.

Recently, the multinational guideline Surviving Sepsis for COVID-19 recommended using steroids in patients with severe conditions and on mechanical ventilation, the purpose of which is to reduce the destructive risk, based on immunological evidence [36]. The most discerning evidence to date, the RECOVERY study, brings in primary analyzes a reduction in mortality and length of hospital stay using dexamethasone [37].

The use of GC has shown a direct relationship with the development of hypercortisolism, especially in patients with individual hypersensitivity or hypoadrenalism after discontinuation of the drug. Moreover, it is known that most patients are treated with antiretroviral drugs, such as ritonavir, which acts as an inhibitor of cytochrome P4503A enzymes. By increasing the concentrations of a drug metabolized by the same route, such as GCs, this enzyme inhibitor can promote a hypercortisolemic condition [38, 39]. Still, the chronic use of high-dose GC followed by abrupt interruption can trigger tertiary adrenal insufficiency. Thus, the therapeutic use of these drugs must be done with care [40].

Finally, it is essential to remember the hyperglycemic potential of GC, which can be crucial in the care of diabetic patients with COVID-19. The prospective RECOVERY study found no evidence that GCs induce hyperglycemia more than standard therapy [37].

Limitations

This systematic review has significant limitations. Due to the emergency of the study, only articles with notable differences in terms of their base populations, the clinical status of the participants, analyzed outcome, and corticotherapy were used. The lack of more careful studies such as prospective cohorts or randomized controlled trials also limits the data gathered in our research.

Conclusion

Given the studies analyzed in this review, we came up with some observations that can assist us in the therapeutic conduct with GC in patients with COVID-19. The understanding of the pathophysiological basis of COVID- 19 is crucial for good clinical reasoning and the consequent prescription of GCs since studies have shown that more severe patients on ventilatory support seem to have a more significant benefit from GC therapy. The main observation is the reduction of the characteristic inflammatory markers in the most severe phase of the disease, resulting in pulmonary complications leading to a disorganization of the alveolar microvasculature. However, since the studies are not strong enough to lead us to a reliable conclusion, we emphasize that the use of GCs must be carried out with discretion and caution for a better prognosis.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- GC

Glucocorticoids

- WHO

WORLD Health Organization

- G-CSF

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

- ICU

Intensive care units

- IFN-y

Interferon-gamma

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- IL-1B

Interleukin 1B

- MERS

Middle East respiratory syndrome

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemoattracting protein 1

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- TNF-a

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

Author contributions

Conceived the idea: LPC, EONNL, DJMML. Wrote the manuscript: LPC, EONNL, FGON, DJMML. Reviewed critically for content: LPC, EONNL. Carefully reviewed the final manuscript: DMS. All authors approved the final manuscript and submission.

Funding

None.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chen Y, Liu Q, Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):418–423. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoeman D, Fielding BC. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol J. 2019;16(1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the ‘Cytokine Storm’ in COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;80(6):607–13. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Search of: glucocorticoids | Covid-19 - List Results - ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 2]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Covid-19&term=glucocorticoids&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search. Accessed 2 June 2020.

- 5.Search of: remdesivir | Covid-19 - List Results - ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 2]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Covid-19&term=remdesivir&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search. Accessed 2 June 2020.

- 6.Search of: plasmaphereses | Covid-19 - List Results - ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 2]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=plasmaphereses&cond=Covid-19. Accessed 2 June 2020.

- 7.Search of: anticoagulant | Covid-19—List Results—ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 2]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Covid-19&term=anticoagulant&cntry=&state=&city=&dist. Accessed 2 June 2020.

- 8.Search of: chloroquine | Covid-19—List Results—ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 2]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=chloroquine&cond=Covid-19. Accessed 2 June 2020.

- 9.Vandewalle J, Luypaert A, De Bosscher K, Libert C. therapeutic mechanisms of glucocorticoids. Trends EndocrinolMetab [Internet]. 2018;29(1):42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic Treatments for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2019;2020:2019. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knowmann BC. Goodman & Gillman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Cao J, Tu WJ, Cheng W, Yu L, Liu YK, Hu X, Liu Q. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 102 patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):748–55. 10.1093/cid/ciaa243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Fang X, Mei Q, Yang T, Li L, Wang Y, Tong F, et al. Low-dosecorticosteroid therapy does not delay viral clearance in patients with COVID-19. J Infect [Internet]. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zha L, Li S, Pan L, Tefsen B, Li Y, French N, et al. Corticosteroid treatment of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Med J Aust. 2020;212(9):416–420. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet [Internet]. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong Y, Guan L, Jin Z, Chen S, Xiang G, Gao B. Effects ofmethylprednisolone use on viral genomic nucleic acid negative conversion and CT imaging lesion absorption in COVID-19 patients under 50 years old. J Med Virol. 2020;92(11):2551–2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Xu G, Yu H, Peng X, Luo Y, Cao C. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of 74 patients with severe or critical COVID-19. Am J Med Sci. 2020;360(3):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Shang J, Du R, Lu Q, Wu J, Xu S, Ke Z, et al. The Treatment and outcomes of patients with COVID-19 in Hubei, China: a multi-centered, retrospective, observational study. SSRN Electron J. 2020.

- 21.Wang Y, Jiang W, He Q, Wang C, Wang B, Zhou P, et al. Early, low-dose and short-term application of corticosteroid treatment in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia: single-center experience from Wuhan, China. medRxiv [Internet]. 2020;2020.03.06.20032342. http://medrxiv.org/content/early/2020/03/12/2020.03.06.20032342.abstrac. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- 22.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with CoronavirusDisease2019pneumoniainWuhan,China. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;2020:1–10. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu K, Chen Y, Yuan J, et al. Factors associated with prolonged viral RNA shedding in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):799–806. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinicalcourseandoutcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med [Internet]. 2020;8(5):475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernández-Cruz A, Ruiz-Antorán B, Muñoz-Gómez A, Sancho-López A, Mills-Sánchez P, Centeno-Soto GA, et al. A retrospective controlled cohort study of the impact of Glucocorticoid treatment in SARS-CoV-2 infection mortality. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64(9):e01168–20. Available from: http://aac.asm.org/content/64/9/e01168-20.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Salacup G, Lo KB, Gul F, Peterson E, De Joy R, Bhargav R, Pelayo J, Albano J, Azmaiparashvili Z, Benzaquen S, Patarroyo-Aponte G, Rangaswami J. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients in an underserved-inner city population: A single tertiary center cohort. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.26252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Arabi YM, Fowler R, Hayden FG. Critical care management of adults with community-acquired severe respiratory viral infection. Intensive Care Med [Internet]. 2020;46(2):315–328. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05943-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabaan AA, Alahmed SH, Bazzi AM, Alhani HM. A review of candidate therapies for middle east respiratory syndrome from a molecular perspective. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66(9):1261–1274. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mo Y, Fisher D. A review of treatment modalities for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. J AntimicrobChemother. 2016;71(12):3340–3350. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Chen C, Hu F, Wang J, Zhao Q, Gale RP, et al. Impact of corticosteroid therapy on outcomes of persons with SARS-CoV-2, SARS- CoV, or MERS-CoV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leukemia [Internet]. 2020;34(6):1503–1511. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0848-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ng PC, Lam CWK, Li AM, Wong CK, Cheng FWT, Leung TF, et al. Inflammatory cytokine profile in children with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1):7–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Lau ACW, So LKY, Miu FPL, Yung RWH, Poon E, Cheung TMT, et al. outcome of coronavirus-associated severe acute respiratory syndrome using a standard treatment protocol. Respirology. 2004;9(2):173–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arabi YM, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, Sindi AA, Almekhlafi GA, Hussein MA, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with middle east respiratory syndrome. Am J RespirCrit Care Med. 2018;197(6):757–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loutfy MR, Blatt LM, Siminovitch KA, Ward S, Wolff B, Lho H, et al. Interferon alfacon-1 plus corticosteroids in severe acute respiratory syndrome: a preliminary study. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290(24):3222–3228. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.24.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee N, Allen Chan KC, Hui DS, Ng EKO, Wu A, Chiu RWK, et al. Effects of early corticosteroid treatment on plasma SARS-associated Coronavirus RNA concentrations in adult patients. J ClinVirol. 2004;31(4):304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Internet]. In: Vol. 46, Intensive Care Medicine. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2020; p. 854–887 p. 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson J, Mafham M, Bell J, Landary MJ, et al. Effect of dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19—preliminary report. MedRvix. 2020 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3928540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berton AM, Prencipe N, Giordano R, Ghigo E, Grottoli S. Systemicsteroids in patients with COVID-19: pros and contras, an endocrinological point of view. J Endocrinol Invest [Internet]. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01325-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scaroni C, Armigliato M, Cannavò S. COVID-19 outbreak and steroids administration: are patients treated for Sars-Cov-2 at risk of adrenal insufficiency? J Endocrinol Invest [Internet]. 2020;43(7):1035–1036. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01253-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almeida MQ, Mendonca BB. Adrenal insufficiency and glucocorticoid use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2020;75:e2022. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2020/e2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]