Abstract

BACKGROUND

The presence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA in liver tissue or peripheral blood mononuclear cells with no identified virus genome in the serum has been reported worldwide among patients with either normal or elevated serum liver enzymes. The characterization of occult HCV infection (OCI) epidemiology in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean (M and E) countries, a region with the highest incidence and prevalence rates of HCV infection in the world, would be effective for more appropriate control of the infection.

AIM

To estimate the pooled prevalence of OCI in M and E countries using a systematic review and meta-analysis.

METHODS

A systematic literature search was performed using international, regional and local electronic databases. Some conference proceedings and references from bibliographies were also reviewed manually. The search was carried out during May and June 2020. Original observational surveys were considered if they assessed the prevalence of OCI among the population of M and E countries by examination of HCV nucleic acid in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in at least 30 cases selected by random or non-random sampling methods. The meta-analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software based on heterogeneity assessed by Cochran’s Q test and I-square statistics. Data were considered statistically significant at a P value < 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 116 non-duplicated citations were found in electronic sources and grey literature. A total of 51 non-overlapping original surveys were appraised, of which 37 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. Data were available from 5 of 26 countries including Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. The overall prevalence rate of OCI was estimated at 10.04% (95%CI: 7.66%-13.05%). The lowest OCI rate was observed among healthy subjects (4.79%, 95%CI: 2.86%-7.93%). The higher rates were estimated for patients suffering from chronic liver diseases (12.04%, 95%CI: 5.87%-23.10%), and multi-transfused patients (8.71%, 95%CI: 6.05%-12.39%). Subgroup analysis indicated that the OCI rates were probably not associated with the studied subpopulations, country, year of study, the detection method of HCV RNA, sample size, patients’ HCV serostatus, and sex (all P > 0.05). Meta-regression analyses showed no significant time trends in OCI rates among different groups.

CONCLUSION

This review estimated high rates of OCI prevalence in M and E countries, especially among multi-transfused patients as well as patients with chronic liver diseases.

Keywords: Occult hepatitis C, Prevalence, Review, Meta-analysis, Middle East, Eastern Mediterranean region

Core Tip: No comprehensive reported data are available in the literature regarding the estimated prevalence rate of occult hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean countries. This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to calculate occult HCV infection rate in this region. We estimated the overall rate as well as the rates among both healthy and high-risk populations such as those infected with human immunodeficiency virus, patients with end-stage renal diseases, cryptogenic liver diseases, cleared or treated HCV infection, lymphoproliferative disorders, and multi-transfused patients.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization set the global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis in 2015 and established some service coverage targets, including the diagnosis of 90% of persons with chronic hepatitis C and treatment of 80% of the diagnosed cases to eliminate hepatitis C as a public health concern by 2030[1]. Occult hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (OCI) was introduced as a new and challenging form of this infection in 2004[2]. OCI is characterized by the presence of HCV RNA in the liver samples of patients who were seronegative for the viral RNA[2]. Although liver biopsy is the most accurate way to diagnose OCI cases[3], a reliable and non-invasive alternative method is the examination of the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) for the presence of HCV genome[4,5].

Occult hepatitis C has been proposed to occur in two different clinical conditions. The first category has been described in people reactive to HCV antibodies (anti-HCV) but with normal serum levels of liver enzymes. The majority of these patients are those with HCV infection treated with antiviral drugs or cleared spontaneously. In the second type of OCI, called serologically silent, cryptogenic, or secondary OCI, both anti-HCV and serum HCV-RNA are consistently negative but an increase in liver enzymes is observed[6]. Cryptogenic OCI is found mostly in patients with cryptogenic liver disease; however, the incidence of this type of OCI was also reported among blood donors[7].

Occult hepatitis C might be a long-standing infection[8]. OCI appears to be milder than classic chronic HCV infection; however, it is likely related to the development of liver cirrhosis or even hepatic cancer[3,9,10]. Additionally, patients with OCI may benefit from antiviral therapies[11]. OCI is a common condition worldwide and all HCV genotypes can be involved in this form of infection[11]. This infection has been described in high-risk populations, such as patients with chronic liver disease, dialysis patients, those infected with HBV or HIV, the family members of patients with HCV infection, and even apparently healthy populations[3].

The Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean (M and E) region has been reported to have the highest rates of HCV infection in the world, with an incidence of 62.5 per 100000 person-years and prevalence of 2.3% among the general population (GP). In 2015, it was estimated that approximately one-fourth of 1.75 million newly HCV-infected persons and one-fifth of 71 million chronically infected individuals in the world resided in M and E countries[12]. The median of the anti-HCV seropositivity rate in the GP of this region ranged broadly from 0.3% in Iran[13] to 13.0% in Egypt[10]. In addition, the rate of HCV viremia among anti-HCV positive individuals in M and E countries varies widely from 9% to 100% with a median of 68.8%; the overall pooled rate was averagely estimated as 67.6% (95%CI: 64.9 ± 70.3%)[14].

The prevalence rate of OCI ranged from zero to 60% among the different studied populations in various M and E countries[15-17]. To our knowledge, no review has yet been performed to provide a pooled estimate for the OCI prevalence rate in this region. In the current systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to determine OCI epidemiology among both healthy and risk populations in this region by (1) providing pooled mean estimates for the OCI rate through systematically reviewing and analyzing existing data in various subpopulations; (2) assessing the possible factors contributing to between-study heterogeneity; and (3) evaluating the change in OCI prevalence in different studied populations over time. The results of the present review would help professionals to make appropriate decisions for the detection and management of OCI, particularly in at-risk patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

We performed this review and meta-analysis following the PRISMA 2009 statement[18]. The main object was the presence of HCV RNA in PBMCs detected by a reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) technique in the blood samples of healthy individuals or different patient categories from M and E countries. The search strategy included “Occult Hepatitis C” or “Occult HCV” along with “Middle East”, “Eastern Mediterranean”, or the names of M and E countries. In this study, the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean region consisted of 26 countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Cyprus, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. The considered terms were searched in the title, abstract, and keywords using Web of Science and SCOPUS and in the text using PubMed, ScienceDirect, and ProQuest databases. Likewise, some regional and local databases were searched as “Occult Hepatitis C” or “Occult HCV” to find the articles published in the English language. These databases included the Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region, Scientific Information Database, Iranian Database of publication (Magiran), and Iranian Databank of Medical Literature. In addition, some appropriate available abstract booklets and conference proceedings were manually reviewed. The search was performed from 21 May to 08 June 2020 and then expanded by manual cross-checking all references found from bibliographies of retrieved citations.

Study selection and data extraction

The two authors screened the titles and abstracts of the documents identified in the electronic and grey literature. Duplicate and overlapping surveys (the same studied population, methods, and findings) were excluded. Regarding articles, which reported the OCI prevalence in the region, various methodological aspects of the studies were assessed using a 10-items checklist, specifically developed to evaluate both internal and external validity of the prevalence studies[19]. These aspects encompassed the representativeness of the target population, sampling methods, sample size, data collection methods and instruments, response rate, and statistical analysis. The main inclusion criteria were detection of the HCV genome in PBMCs of at least 30 healthy or high-risk subjects selected by probable or non-probable sampling methods in an original observational survey. Review articles, case reports, editorials, or letters were removed. Surveys that evaluated OCI in hepatocytes or other samples except PBMCs were not included. In addition, studies were not entered into the meta-analysis if they did not use an acceptable case definition and/or not apply an appropriate numerator and denominator for calculating the event rates.

The full texts, tables, and figures of all relevant articles were reviewed for data extraction by the two authors. The following variables were listed for each study: First author, year of publication, years of data collection, study type, study location, studied population, sampling method, the number of cases with anti-HCV and HCV RNA seropositivity, methods used to assess HCV genome, and the number and demographic features of cases with detectable HCV RNA in their PBMCs samples. Since the surveys in this field were restricted, no specific exclusion criteria were set for the studied population, year of data collection, and patients’ age and sex.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software 2.2.064 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, United States). With inverse variance weighting, a random-effect model was applied using the DerSimonian and Laird method if heterogeneity between studies was observed based on Cochran’s Q test (P < 0.05) and I-square statistics (I2, values of > 50%). Forest plots were applied to demonstrate the point prevalence rates and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were implemented to identify the possible factors related to heterogeneity between surveys. HCV serostatus was classified as seronegative (negative results for both anti-HCV and serum HCV RNA) and seropositive (tested positive for anti-HCV but negative for serum HCV genome). All statistical data were considered significant at a P value < 0.05.

RESULTS

Study selection

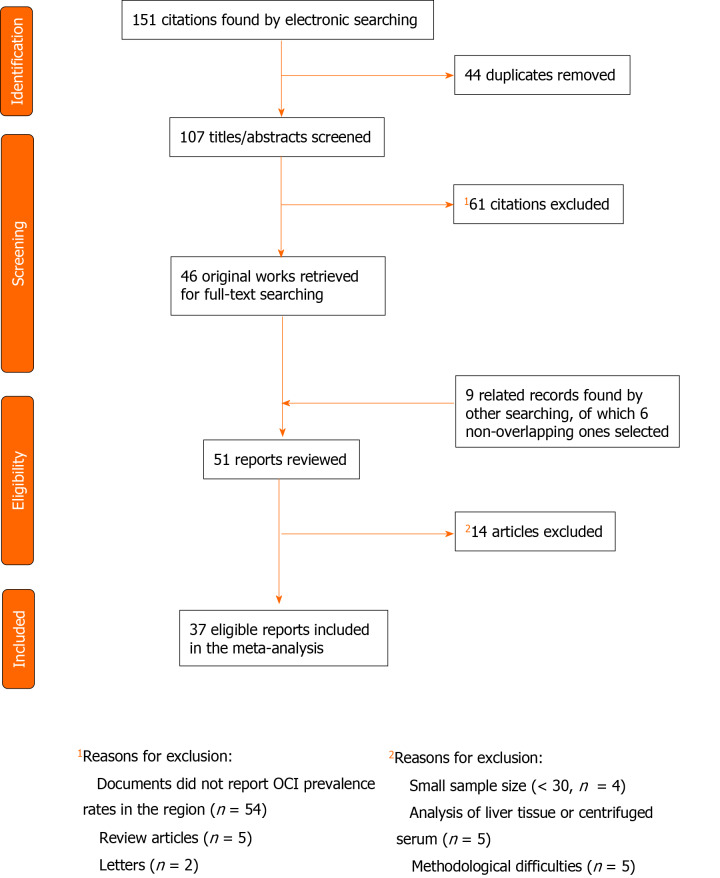

Among 151 citations retrieved from electronic sources, 107 non-duplicated items were selected to review the titles and abstracts (Figure 1). Fifty-two surveys discussed the prevalence of OCI in M and E countries[15-17,20-68], of which 5 review articles and 2 letters were excluded[62-68]. In addition, 4 pertinent documents were identified following a review of abstracts[69-72], and 5 documents were found by a manual screening of bibliographies[73-77]. After removing 3 overlapping surveys[71,72,75], 51 original articles were chosen for a thorough review of the full-text[15-17,20-61,69,70,73,74,76,77]. Most of the surveys had used a non-probable method to select studied samples and none of them had discussed non-response bias. Fourteen articles were not included owing to methodological difficulties, small sample size, and/or analysis of liver tissue or centrifuged serum[20,24,28,30,32,34,37,40,52,56,61,70,73,77].

Figure 1.

Study selection for the systematic review and meta-analysis of occult hepatitis C prevalence across the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean countries. OCI: Occult hepatitis C virus infection.

Finally, 37 non-duplicate and non-overlapping articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis[15-17,21-23,25-27,29,31,33,35,36,38,39,41-51,53-55,57,58,59,60,69,74,76]. All studies were cross-sectional investigations and almost all of them were based on consecutive samples selected by a non-random convenience sampling method. The mean sample size was 141 (range: 30-1280); less than 100 cases in 23 studies, 100-200 cases in 11 surveys, and more than 200 cases in three studies.

The overall prevalence of occult hepatitis C in M and E countries

Of the 26 included countries, data were available only from five countries. Egypt (n = 17) and Iran (n = 17) were the countries with the largest number of studies reporting OCI prevalence but Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey contributed to only one data point. These five countries had surveyed OCI prevalence among a total of 5200 individuals between 2009 and 2019 (Table 1). The studied population included blood donors, patients for whom HCV infection was resolved following antiviral treatment or spontaneously, patients with cryptogenic chronic liver diseases (LDs), autoimmune hepatitis, thalassemia, hemophilia, lymphoproliferative disorders, or anemia, patients undergoing hemodialysis (HD), HIV positive individuals, and injecting drug users (IDUs). Five surveys had collected data from mixed populations, mainly healthy volunteers as well as those suffering from chronic diseases.

Table 1.

Selected studies for systematic review and meta-analysis of occult hepatitis C virus infection prevalence in the Middle Eastern countries and Eastern Mediterranean Region

| Ref. | Years of data collection | Country | Population | Serostatus | HCV RNA detection method | Sample size |

OCI

|

|

|

Number

|

Percent

|

|||||||

| Makvandi et al[21], 2014 | 2011-2012 | Iran | Patients with unexplained abnormal ALT | Seronegative | Is-nested PCR | 53 | 17 | 32.08 |

| Zaghloul et al[22], 2010 | 2010 | Egypt | (1) Patients with unexplained abnormal ALT and AST; (2) Patients with chronic hepatitis C who achieved SVR | Seronegative/seropositive | rRT-PCR | 102 | 11 | 10.78 |

| El Shazly et al[23], 2015 | 2014 | Egypt | Healthy sexual partners of patients with HCV infection | Seronegative | rRT-PCR | 50 | 2 | 4.00 |

| Bozkurt et al[74], 2014 | ? | Turkey | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative | rRT-PCR | 84 | 3 | 3.57 |

| Mohamed et al[25], 2017 | 2017 | Egypt | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative | RT-PCR | 60 | 2 | 3.33 |

| Donyavi et al[26], 2019 | 2015-2018 | Iran | HIV positive injecting drug users | Seronegative/seropositive | RT-nested PCR | 77 | 14 | 18.18 |

| Ayadi et al[27], 2019 | 2017-2018 | Iran | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 515 | 95 | 18.45 |

| El-Rehewy et al[29], 2015 | 2012-2014 | Egypt | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative | rRT-PCR | 75 | 8 | 10.67 |

| Sheikh et al[31], 2019 | 2017-2018 | Iran | Injecting drug users(negative for HIV) | Seronegative/seropositive | RT-nested PCR | 115 | 11 | 9.57 |

| Jamshidi et al[33], 2020 | 2015-2019 | Iran | HIV positive patients | Seronegative/seropositive | RT-nested PCR | 143 | 14 | 9.79 |

| Abd Alla et al[35], 2017 | 2015-2017 | Egypt | (1) Patients with chronic hepatitis C; (2) Healthy individuals | Seronegative/seropositive | RT-nested PCR | 174 | 41 | 23.56 |

| Ramezani et al[16], 2014 | 2014 | Iran | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative/seropositive | RT-nested PCR | 30 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Muazzam et al[17], 2011 | 2007-2009 | Pakistan | Patients with chronic hepatitis C who achieved SVR | Seronegative | rRT-PCR | 104 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Naghdi et al[36], 2017 | 2017 | Iran | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 198 | 6 | 3.03 |

| Abdelrahim et al[38], 2016 | 2013-2014 | Egypt | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative | rRT-PCR | 81 | 3 | 3.70 |

| Ali et al[39], 2018 | 2014 | Egypt | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative | rRT-PCR | 39 | 9 | 23.08 |

| Keyvani et al[41], 2013 | 2007-2013 | Iran | Patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 45 | 4 | 8.89 |

| Serwah et al[42], 2014 | 2013-2014 | Saudi Arabia | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative | rRT-PCR | 84 | 12 | 14.29 |

| El-shishtawy et al[43], 2015 | 2015 | Egypt | (1) Hemodialysis patients; (2) Healthy volunteers | Seronegative | Strand-specific RT-PCR | 63 | 8 | 12.70 |

| Nafari et al[44], 2020 | 2017-2018 | Iran | Hemophilia patients | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 450 | 46 | 10.22 |

| Eslamifar et al[71], 2015 | 2013 | Iran | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 70 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Bokharaei-Salim et al[46], 2011 | 2007-2010 | Iran | Patients with cryptogenic liver disease | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 69 | 7 | 10.14 |

| Rezaee Zavareh et al[47], 2014 | 2012-2013 | Iran | Patients with autoimmune hepatitis | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 35 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Ayadi et al[48], 2019 | 2017-2018 | Iran | Thalassemia patients | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 181 | 6 | 3.31 |

| Mekky et al[50], 2019 | 2017 | Egypt | Patients with chronic hepatitis C who achieved SVR | Seropositive | rRT-PCR | 1280 | 50 | 3.91 |

| El-Moselhy et al[51], 2015 | 2014-2015 | Egypt | Hemodialysis patients | Unknown | RT-PCR/RT-nested PCR | 66 | 18 | 27.27 |

| Anber et al[76], 2016 | 2015 | Egypt | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative/seropositive | rRT-PCR | 63 | 9 | 14.29 |

| Abdelmoemen et al[53], 2018 | 2016 | Egypt | Hemodialysis patients | Seronegative | rRT-PCR | 62 | 3 | 4.84 |

| Eldaly et al[54], 2016 | ? | Egypt | Blood donors | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 138 | 8 | 5.80 |

| Youssef et al[55], 2012 | 2010-2011 | Egypt | (1) Patients with lymphoproliferative disorders; (2) Healthy volunteers | Seronegative | RT-PCR/RT-nested PCR | 87 | 12 | 13.79 |

| Bastani et al[57], 2016 | 2015 | Iran | Thalassemia patients | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 106 | 6 | 5.66 |

| Farahani et al[58], 2013 | 2010-2011 | Iran | Patients with lymphoproliferative disorders | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 104 | 2 | 1.92 |

| Yousif et al[59], 2018 | 2017 | Egypt | Patients with chronic hepatitis C who achieved SVR | Seropositive | rRT-PCR | 150 | 17 | 11.33 |

| Bokharaei-Salim et al[60], 2016 | 2014-2015 | Iran | HIV positive patients | Seronegative/seropositive | RT-nested PCR | 82 | 10 | 12.20 |

| Helaly et al[15], 2017 | 2014-2015 | Egypt | (1) Patients with hematologic disorders; (2) Healthy subjects | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 50 | 18 | 36.00 |

| Alavian et al[69], 2013 | ? | Iran | Patients with chronic hepatitis C who achieved SVR | Seropositive | RT-PCR | 70 | 9 | 12.86 |

| Askar et al[49], 2010 | ? | Egypt | Patients with unexplained persistently abnormal liver function tests | Seronegative | RT-nested PCR | 45 | 20 | 44.44 |

ALT: Alanine transaminase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; Is-PCR: In situ-PCR; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; RT-PCR: Reverse transcription PCR; rRT-PCR: Real time RT-PCR; SVR: Sustained virologic response.

The studied subjects were aged 4 to 89 years and their mean age was between 26 ± 9.31 and 58.9 ± 14.7 years. In 23 studies, 53.2%-98.4% of the participants were males, in 10 surveys, 50.0%-58.1% of them were females, and sex distribution of the samples was not stated in four documents.

As shown in Table 2, the rate of OCI prevalence in this region ranged widely from 0.0% to 44.44%, with a median of 10.14%. The overall mean prevalence was estimated to be 10.04% (95%CI: 7.66%-13.05%). Across subpopulations, the pooled average OCI rate was highest at 21.70% (95%CI: 11.26%-37.72%) among patients with cryptogenic liver disease, followed closely by 18.18% (95%CI: 11.07%-28.39%) among HIV positive IDUs and 18.15% (95%CI: 10.20-30.20%) in the mixed population. The rate of OCI in Egypt (12.34%; 95%CI: 8.32-17.92%) was higher than in Iran (8.48%; 95%CI: 5.51%-12.84%); however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.157). Subgroup analysis showed that the rate of OCI was probably not related to the disease subpopulations (P = 0.066), year of data collection (P = 0.786), the detection method of HCV RNA (P = 0.507), sample size (P = 0.057), patients’ HCV serostatus (P = 0.178) and sex (P = 0.953). Furthermore, meta-regression analysis showed no significant (P = 0.580) time trend in the OCI rate among the total population of this region.

Table 2.

Subgroup-specific pooled estimates of occult hepatitis C virus infection prevalence across the Middle Eastern and Eastern Mediterranean countries

| Prevalence by | Number of studies | Sample sizes |

OCI prevalence across studies

|

Pooled OCI prevalence

|

Heterogeneity

|

|||

|

Range (%)

|

Median

|

Mean (%)

|

95%CI

|

Cochran’s Q

|

I-squared (%)

|

|||

| Studied population | ||||||||

| Blood donors | 1 | 138 | - | - | 5.80 | 2.93-11.16 | - | - |

| Hemodialysis patients | 13 | 1427 | 0-27.27 | 4.84 | 9.06 | 5.83-13.80 | 64.0a | 81.2 |

| Healthy sexual partners of patients with chronic hepatitis C | 1 | 50 | - | - | 4.00 | 1.00-14.63 | - | - |

| Patients with chronic hepatitis C who achieved SVR | 4 | 1604 | 0-12.86 | 7.62 | 6.70 | 3.08-13.99 | 25.4a | 88.2 |

| Patients with cryptogenic liver disease | 4 | 212 | 8.89-44.44 | 21.11 | 21.70 | 11.26-37.72 | 22.6a | 86.7 |

| Patients with autoimmune hepatitis | 1 | 35 | - | - | 1.39 | 0.09-18.67 | - | - |

| Patients with lymphoproliferative disorders | 1 | 104 | - | - | 1.92 | 0.48-7.36 | - | - |

| Hemophilia patients | 1 | 450 | - | - | 10.22 | 7.74-13.38 | - | - |

| Thalassemia patients | 2 | 287 | 3.31-5.66 | 4.49 | 4.32 | 2.47-7.46 | 0.9 | 0.00 |

| HIV positive individuals | 2 | 225 | 9.79-12.20 | 10.99 | 10.72 | 7.29-15.50 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| HIV positive injecting drug users | 1 | 77 | - | - | 18.18 | 11.07-28.39 | - | - |

| Injecting drug users | 1 | 115 | - | - | 9.57 | 5.38-16.45 | - | - |

| Mixed population1 | 5 | 476 | 10.78-36 | 13.79 | 18.15 | 10.20-30.20 | 18.2b | 78.1 |

| Countries | ||||||||

| Egypt | 17 | 2585 | 3.33-44.44 | 11.33 | 12.34 | 8.32-17.92 | 186.2a | 91.4 |

| Iran | 17 | 2343 | 0-32.08 | 9.57 | 8.48 | 5.51-12.84 | 86.5a | 81.5 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 104 | - | - | 0.48 | 0.03-7.15 | - | - |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 84 | - | - | 14.29 | 8.30-23.49 | - | - |

| Turkey | 1 | 84 | - | - | 3.57 | 1.16-10.49 | - | - |

| Temporal duration2 | ||||||||

| Before 2015 | 18 | 1227 | 0-44.44 | 9.52 | 9.58 | 6.26-14.40 | 88.5a | 80.8 |

| 2015 and thereafter | 19 | 3973 | 3.03-36 | 10.22 | 10.33 | 7.21-14.61 | 192.07a | 90.6 |

| Method of HCV RNA detection | ||||||||

| RT-nested PCR | 22 | 2833 | 0-44.44 | 9.97 | 11.75 | 8.52-15.99 | 159.3a | 86.8 |

| Real time RT-PCR | 12 | 2174 | 0-23.08 | 7.75 | 7.88 | 4.96-12.30 | 58.4a | 81.2 |

| RT-PCR | 2 | 130 | 145.71-173.33 | 159.52 | 7.75 | 2.34-22.75 | 3.3 | 69.5 |

| Strand-specific PCR | 1 | 63 | - | - | 12.70 | 6.48-23.39 | - | - |

| Patients’ HCV serostatus | ||||||||

| Seronegative | 25 | 2774 | 0-44.44 | 5.80 | 9.32 | 6.76-12.73 | 164.0a | 85.4 |

| Seropositive | 4 | 1604 | 6.20-66.50 | 37.62 | 6.64 | 2.94-14.30 | 25.4a | 88.2 |

| Seronegative/ Seropositive | 7 | 756 | 27.27-109.09 | 73.53 | 13.58 | 8.01-22.11 | 17.8b | 66.3 |

| Undetermined | 1 | 66 | - | - | 27.27 | 17.91-39.19 | - | - |

| Sample size | ||||||||

| Less than 100 | 23 | 1440 | 0-44.44 | 12.20 | 12.43 | 8.87-17.15 | 102.4a | 78.5 |

| 100 and above | 14 | 3760 | 0-23.56 | 7.69 | 7.43 | 4.86-11.19 | 153.0a | 91.5 |

| Patients’ sex | ||||||||

| Female | 11 | 602 | 0-35.29 | 8.62 | 9.92 | 5.39-17.55 | 32.4a | 69.2 |

| Male | 11 | 1785 | 0-30.56 | 9.09 | 10.17 | 5.85-17.10 | 70.8a | 85.9 |

| All studies | 37 | 5200 | 0-44.44 | 10.14 | 10.04 | 7.66-13.05 | 284.1a | 87.3 |

P < 0.001.

P < 0.01.

Four studies investigated occult hepatitis C virus infection among healthy volunteers along with hemodialysis patients, patients with chronic hepatitis C, or patients with hematologic and lymphoproliferative disorders. Also one study investigated both the patients with chronic hepatitis C and patients with cryptogenic liver disease.

Based on the last year reported for the data collection. If the collection date was not clear, publication year was considered instead. CI: Confidence interval; Min: Minimum; Max: Maximum; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; RT-PCR: Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; OCI: Occult hepatitis C virus infection.

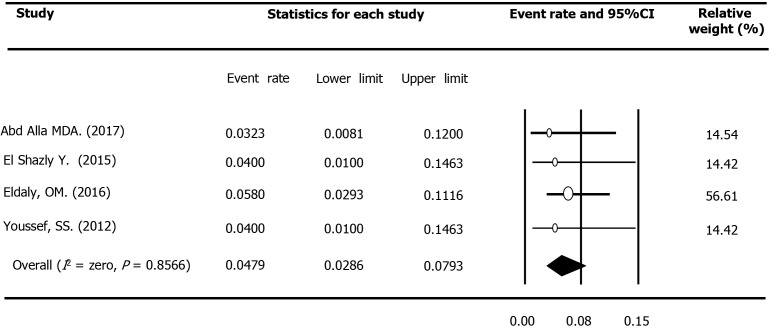

Occult hepatitis C prevalence among healthy populations

Four studies conducted in the M and E area reported OCI prevalence among 300 apparently healthy subjects, such as healthy volunteers, blood donors, and healthy sexual partners of patients with chronic HCV infection. All four studies had been performed among Egyptian HCV-seronegative cases, of which three had studied less than 100 cases, and three had been conducted after 2014. Assessment of HCV RNA in PBMCs had been carried out using RT-nested PCR in three surveys and real-time RT-PCR in another research. Based on the fixed-effect model (Q = 0.77, P = 0.857, I2 = Zero), the pooled estimation of OCI prevalence among healthy populations was 4.79% (95%CI: 2.86%-7.93%, Figure 2). No evidence was found for a significant trend in the OCI rate in this population over time (P = 0.802).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis forest plot of occult hepatitis C among healthy populations across the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean countries.

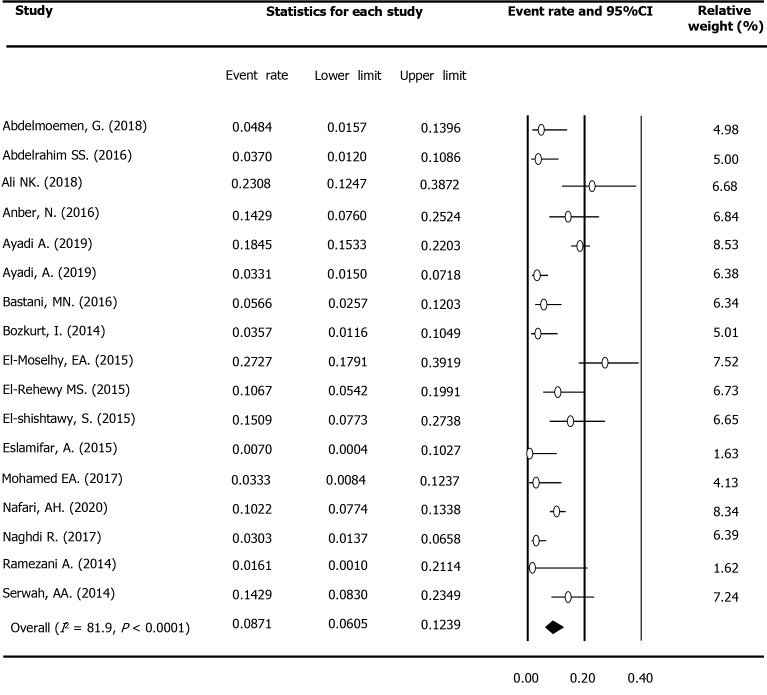

Occult hepatitis C prevalence among multi-transfused patients

Seventeen studies reported the OCI rate among 2217 multi-transfused patients (MTPs), including 1480 HD patients, 450 hemophilia patients, and 287 thalassemia patients in the region. Fifteen surveys evaluated the presence of viral genome among HCV seronegative samples. As shown in Table 3, the prevalence rate was estimated to be 8.71% (95%CI: 6.05%-12.39%) among this population (Figure 3). Based on 14 surveys, the estimated OCI rate among HD patients was 9.52% (95%CI: 6.30%-14.12%).

Table 3.

Subgroup-specific pooled estimates of occult hepatitis C virus infection prevalence among multi-transfused patients across the Middle Eastern and Eastern Mediterranean countries

| Prevalence by | Number of studies | Sample sizes |

OCI prevalenceacross studies

|

Pooled OCI prevalence (%)

|

Heterogeneity

|

|||

|

Range (%)

|

Median

|

Mean (%)

|

95%CI

|

Cochran’s Q

|

I-squared (%)

|

|||

| Studied population | ||||||||

| Hemodialysis patients | 14 | 1480 | 0-27.27 | 7.75 | 9.52 | 6.30-14.12 | 64.0a | 79.7 |

| Thalassemia patients | 2 | 287 | 3.31-5.66 | 4.49 | 4.32 | 2.47-7.46 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Hemophilia patients | 1 | 450 | - | - | 10.22 | 7.74-13.38 | - | - |

| Countries | ||||||||

| Egypt | 8 | 499 | 3.33-27.27 | 12.48 | 11.43 | 6.55-19.17 | 26.8a | 73.8 |

| Iran | 7 | 1550 | 0-18.45 | 3.31 | 5.93 | 3.09-11.09 | 54.8a | 89.0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 84 | - | - | 14.29 | 8.30-23.49 | - | - |

| Turkey | 1 | 84 | - | - | 3.57 | 1.16-10.49 | - | - |

| Temporal duration1 | ||||||||

| Before 2015 | 7 | 463 | 0-23.08 | 3.70 | 7.89 | 4.10-14.65 | 20.6b | 70.8 |

| 2015 and thereafter | 10 | 1754 | 3.03-27.27 | 7.94 | 9.04 | 5.69-14.09 | 66.5a | 86.5 |

| Method of HCV RNA detection | ||||||||

| RT-nested PCR | 8 | 1616 | 0-27.27 | 4.49 | 7.79 | 4.38-13.47 | 65.6a | 89.3 |

| Real time RT-PCR | 7 | 488 | 3.57-23.08 | 10.67 | 9.52 | 5.26-16.61 | 17.4b | 65.4 |

| RT-PCR | 1 | 60 | - | - | 3.33 | 0.84-12.37 | - | - |

| Strand-specific PCR | 1 | 53 | - | - | 15.09 | 7.73-27.38 | - | - |

| Sample size | ||||||||

| Less than 100 | 12 | 767 | 0-27.27 | 7.75 | 9.49 | 5.85-15.04 | 40.6a | 72.9 |

| 100 and above | 5 | 1450 | 3.03-18.45 | 5.66 | 7.05 | 3.61-13.33 | 47.9a | 91.6 |

| Participants’ sex | ||||||||

| Female | 6 | 322 | 3.7-33.33 | 8.86 | 11.56 | 6.47-19.81 | 12.7c | 60.8 |

| Male | 6 | 506 | 0-16 | 6.45 | 10.74 | 5.91-18.75 | 13.5c | 63.1 |

| All studies | 17 | 2217 | 0-27.27 | 5.66 | 8.71 | 6.05-12.39 | 88.56a | 81.93 |

P < 0.001.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

Based on the last year reported for the data collection. If the collection date was not clear, publication year was considered instead. CI: Confidence interval; Min: Minimum; Max: Maximum; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; RT-PCR: Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; OCI: Occult hepatitis C virus infection.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis forest plot of occult hepatitis C among multi-transfused patients across the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean countries.

Subgroup analysis revealed that the rate of OCI in Egypt (11.43%; 95%CI: 6.55%-19.17%) was higher than in Iran (5.93%; 95%CI: 3.09%-11.09%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.125). The rate of OCI frequency was not associated with year of study (P = 0.732), the detection technique of HCV RNA (P = 0.618), sample size (P = 0.470), and patients’ sex (P = 0.859). Moreover, meta-regression analysis showed no significant (P = 0.520) changes in the OCI rate among MTPs patients over years.

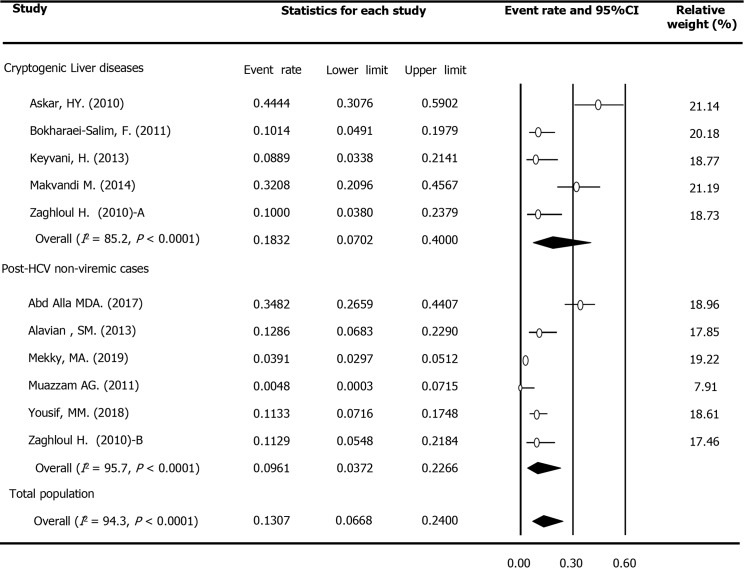

Occult hepatitis C prevalence among patients with chronic liver diseases

In total, 11 surveys reported the OCI prevalence among 2065 patients with chronic LDs in M and E countries. These patients included 1778 with chronic hepatitis C, including those who achieved sustained virologic response after treatment with antiviral drugs, 252 patients with cryptogenic LDs (persistently abnormal liver tests and/or liver cirrhosis with unknown etiology), as well as 35 patients with autoimmune hepatitis. The rate of OCI prevalence among these patients was estimated to be 12.04% (95%CI: 5.87%-23.10%, Table 4). The rate in the subgroup of cryptogenic patients (20.81%; 95%CI: 6.87%-48.35%) was double the value calculated for post-HCV non-viremic cases (9.14%; 95%CI: 3.02%-24.53%, P = 0.276). Figure 4 displays the forest plot of OCI among patients with chronic LDs based on the type of the disease. In addition, the rate of OCI among cases detected by RT-nested PCR (21.38%; 95%CI: 11.73%-35.75%) was considerably higher than cases identified using real-time RT-PCR (6.29%; 95%CI: 2.73%-13.84%, P = 0.052). Furthermore, there was no difference in the OCI frequency based on the year of data collection (P = 0.962), study location (P = 0.178), sample size (P = 0.416), patients’ HCV serostatus (P = 0.750) and sex (P = 0.749). According to meta-regression analysis, no significant (P = 0.943) link was detected between the OCI rate among this population and data collection time. Figure 4 displays the forest plot of OCI among patients with chronic LDs based on type of the disease.

Table 4.

Subgroup-specific pooled estimates of occult hepatitis C virus infection prevalence among patients with chronic liver diseases across the Middle Eastern and Eastern Mediterranean countries

| Variables | Number of studies | Sample sizes |

OCI prevalence across studies

|

Pooled OCI prevalence (%)

|

Heterogeneity

|

|||

|

Range (%)

|

Median

|

Mean (%)

|

95%CI

|

Cochran’s Q

|

I-squared (%)

|

|||

| Countries | ||||||||

| Egypt | 5 | 1689 | 3.91-44.44 | 11.33 | 16.08 | 5.81-37.35 | 152.4a | 97.4 |

| Iran | 5 | 272 | 0-32.08 | 10.14 | 11.46 | 3.64-30.73 | 16.6b | 76.0 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 104 | - | - | 0.48 | 00.03-7.15 | - | - |

| Temporal duration1 | ||||||||

| Before 2015 | 8 | 523 | 0-44.44 | 10.46 | 11.83 | 4.84-26.14 | 46.0a | 84.8 |

| 2015 and thereafter | 3 | 1542 | 3.91-34.82 | 11.33 | 12.28 | 3.23-36.99 | 111.1a | 98.2 |

| Method of HCV RNA detection | ||||||||

| RT-nested PCR | 6 | 359 | 0-44.44 | 21.11 | 21.38 | 11.73-35.75 | 30.5a | 83.6 |

| Real time RT-PCR | 4 | 1636 | 0-11.33 | 7.35 | 6.29 | 2.73-13.84 | 23.9a | 87.4 |

| RT-PCR | 1 | 70 | - | - | 12.86 | 6.83-22.90 | - | - |

| Patients’ subpopulation | ||||||||

| Post-HCV non-viremic cases2 | 5 | 1716 | 0-34.82 | 11.33 | 9.14 | 3.02-24.53 | 116.8a | 96.6 |

| Cryptogenic liver diseases3 | 4 | 212 | 8.89-44.44 | 21.11 | 20.81 | 6.87-48.35 | 22.6a | 86.7 |

| Chronic HCV infection and Cryptogenic liver diseases2,3 | 1 | 102 | - | - | 10.78 | 6.07-18.43 | - | - |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 1 | 35 | - | - | 1.39 | 0.09-18.67 | - | - |

| Patients’ HCV serostatus | ||||||||

| Seronegative | 5 | 247 | 0-44.44 | 10.14 | 16.13 | 5.41-39.28 | 27.7a | 85.6 |

| Seropositive | 5 | 1716 | 0-34.82 | 11.33 | 9.11 | 2.97-24.69 | 116.8a | 96.6 |

| Seronegative/seropositive | 1 | 102 | - | - | 10.78 | 6.07-18.43 | - | - |

| Sample size | ||||||||

| Less than 100 | 6 | 317 | 0-44.44 | 11.50 | 15.63 | 6.08-34.67 | 32.2a | 84.5 |

| 100 and above | 5 | 1748 | 0-34.82 | 10.78 | 8.88 | 3.04-23.26 | 116.0a | 96.5 |

| All studies | 11 | 2065 | 0-44.44 | 10.78 | 12.04 | 5.87-23.10 | 179.3a | 94.4 |

P < 0.001.

P < 0.01.

Based on the last year reported for the data collection. If the collection date was not clear, publication year was considered instead.

Including those patients who achieved sustained virologic response after treatment with anti-virals.

Including unexplained persistently abnormal liver enzymes and cryptogenic cirrhosis. CI: Confidence interval; Min: Minimum, Max: Maximum; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; RT-PCR: Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; OCI: Occult hepatitis C virus infection.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis forest plot of occult hepatitis C among patients with chronic liver diseases across the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean countries based on type of disease. (Note: Zaghloul’s study was considered two surveys, one among patients with cryptogenic liver diseases and one among hepatitis C virus-seropositive patients. Rezaee Zavareh’s study among patients with autoimmune hepatitis was not included in this figure).

Occult hepatitis C prevalence among other high-risk categories

Regarding OCI prevalence among HIV-positive subjects in the M and E region, three surveys reported the rate among 417 HCV-seronegative and seropositive samples. All studies had been conducted in Iran after 2014 and evaluated HCV RNA in PBMCs using the RT-nested PCR method. Using the fixed-effect model (Q = 3.1, P = 0.208, I2 = 36.3%), the pooled mean prevalence of OCI was estimated at 12.95% (95%CI: 9.56%-17.32%) among this population.

Concerning occult hepatitis C among IDUs, one study recently identified HCV RNA in PBMCs in 18.18% of 77 Iranian HIV-positive IDUs. Moreover, another study from Iran reported an OCI rate of 9.57% among 115 HBV- and HIV-negative IDUs. Both surveys detected HCV genome among both HCV seronegative and seropositive samples by the RT-nested PCR method.

A total of three surveys, including two studies from Egypt and one survey from Iran, focused on OCI among patients with hematologic disorders, such as lymphoma, leukemia, and anemia. All OCI cases were detected by the RT-nested PCR technique among 171 HCV seronegative samples. Using the random-effect model (Q = 29.9, P < 0.001, I2 = 93.3%), the pooled estimate of OCI among this population was estimated at 19.57% (95%CI: 3.22%-63.99%).

DISCUSSION

Through a comprehensive description and detailed analysis of occult hepatitis C epidemiology among the various populations in M and E countries, we found a considerably high rate of overall OCI prevalence across the region (10.04%; 95%CI: 7.66%-13.05%). The lowest rate (4.79%) was estimated among apparently healthy volunteers and blood donors. On the other hand, the higher rates were estimated for MTPs (8.71%), patients with chronic LDs (12.04%), HIV-positive subjects (12.95%), and those with lymphoproliferative and hematologic disorders (19.57%). Although the rate varied significantly across the studies, the pooled mean rate of OCI was not dissimilar regardless of subpopulation, location and year of study, the detection method of HCV RNA, patients’ HCV serostatus or sex. Lastly, meta-regression analysis could not ascertain a declining or rising trend for OCI prevalence as a whole or among the different subpopulations of the region.

The incidence of OCI in each area is affected by various factors, mainly the prevalence and risk factors of HCV infection in the community as well as in the studied population. Some investigators believed that there is a geographical pattern for OCI that is probably related to HCV endemicity distribution[3]. The majority of all chronically HCV infected people in the M and E region reside in the two countries most affected by the infection, i.e. Egypt and Pakistan[78]. In the current review, we noted that the Egyptian population had the highest rates (12.34%; 95%CI: 8.32%-17.92%) of OCI in this region. Likewise, based on four studies from Egypt, we calculated the pooled OCI rate among healthy populations to be 4.79 (95%CI: 2.86%-7.93%). Egypt is one of the countries highly affected by HCV and with high anti-HCV prevalence in almost all population groups[10]. Based on the Egypt Demographic and Health Surveys, anti-HCV prevalence among the adult Egyptian population was 10.0% in 2015[10]. Similarly, a recent systematic review estimated a pooled mean rate of 11.9% (95%CI: 11.1%-12.6%) for anti-HCV prevalence among the general Egyptian population[10]. Another systematic review estimated an average pooled HCV viremic rate of 67.0% (95%CI: 63.1%-70.8%) among anti-HCV positive individuals in this country[14]. In other words, the prevalence of chronic hepatitis C in Egypt is around 8%, which is close to the rate (6.3%) reported previously in 2015[79]. Moreover, four-fifths of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients in this country are infected with HCV— which ranks first in the world[80]. On the other hand, Iran has one of the lowest rates of HCV infection worldwide, particularly in the M and E region[81]. In this country, where HCV spread is dominated by transmission through injecting drug use[81], the pooled rates of anti-HCV positivity and viremic HCV among the GP have been estimated as low as 0.2%-0.3% and 0.4%-0.6%, respectively[13,79,81,82]. Correspondingly, we identified a lower overall rate of OCI among the Iranian population (8.48%) in comparison with the Egyptian population (12.34%).

Occult hepatitis C is primarily identified among populations at higher risk of health-care-related exposure, such as people who received repetitive transfusions particularly HD patients[66]. Our analysis estimated an average pooled OCI rate among MTPs of 8.7% (95%CI: 6.0%-12.4%); a higher level was calculated for HD patients (9.5%, 95%CI: 6.3%-14.1%) than for thalassemia patients (4.3%, 95%CI: 2.5%-7.5%). The rates of OCI prevalence among HD patients ranged from zero to 45% in different studies across the world[66]. In a survey by Barril et al[83], 45% of 109 Spanish HD patients with abnormal serum levels of liver enzymes had detectable HCV-RNA in their PBMCs. The patients with OCI had significantly higher mean levels of serum alanine aminotransferase. In addition, a significantly higher percentage of OCI patients died during the follow-up period compared with patients without OCI (39% vs 20%; P = 0.031). It is expected that HD patients are at higher risk of HCV infection owing to shared dialysis machines[84]. Some researchers suggested that the duration of dialysis is associated with the increased probability of HCV infection among HD patients[83,85]. In the M and E region, Harfouche et al[86] showed that about one-fifth of HD patients are chronic HCV carriers and can potentially spread the infection through the dialysis machine. They suggested that their findings may reflect the higher HCV incidence in the communities along with poor standards of dialysis in this area. Despite the decrease in the prevalence of HCV infection in HD patients, OCI could be the culprit for the constant distribution of HCV among this population[3].

Furthermore, our review estimated a two-fold higher rate of OCI among Egyptian MTPs patients (11.4%, 95%CI: 6.5%-19.2%) than Iranian patients (5.9%, 95%CI: 3.1%-11.1%). These findings were consistent with the reported rates for anti-HCV prevalence among this population in both countries. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from 10 countries in the Middle East, the pooled HCV prevalence among HD patients was estimated to be 25.3% (95%CI: 20.2%-30.5%); a much higher rate was reported from Egypt (50%, 95%CI: 46%-55%) in comparison with Iran (12%, 95%CI: 10%-15%)[87]. Indeed, medical care appears to be the main route of both past and new HCV transmission in Egypt[10]. On the other hand, in another recent review, the overall anti-HCV prevalence was estimated at a considerably lower rate (20.0%, 95%CI: 16.4%-23.9%) across Iranian populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures, such as HD, hemophilia, and thalassemia patients[13].

The rate of occult hepatitis C is considerably higher among populations with liver involvement who were seronegative for HCV RNA[2,61,64]. In a recent survey in Egypt, the rate of OCI among 112 post-HCV non-viremic cases, including 55 non-cirrhotic and 57 cirrhotic patients (34.8%) was significantly higher than 62 healthy control individuals (3.23%)[35]. Likewise, our review indicated a high frequency of OCI among patients with LDs, including individuals with unexplained elevated liver enzymes and cryptogenic hepatitis as well as those with a history of exposure to HCV in the past (12.04%, 95%CI: 5.87%-23.10%); the highest rate was observed in patients with cryptogenic LDs (20.81%; 95%CI: 6.87%-48.35%). High rates of OCI among LD patients have been reported from countries with both low and high HCV endemicity in the community[21,22,41,48]. Consistently, our analysis revealed that the rate of OCI among LD patients in Egypt (16.08%; 95%CI: 5.81%-37.35%) did not significantly (P = 0.178) differ from Iranian patients (11.46%; 95%CI: 3.64%-30.73%). Regarding active HCV infection among populations with LDs, high rates have also been reported from both countries. A detailed analysis of HCV epidemiology in the Middle East found a pooled mean prevalence of 35.5% (95%CI: 31.7%-39.5%) in all patients with LDs; the highest rates were estimated for HCC (56.9%; 95%CI: 50.2%-63.5%) and hepatic cirrhosis (50.4%; 95%CI: 40.8%-60.0%). The pooled rate was 58.8% (95%CI: 51.5%-66.0%) in Egypt, 55.8% (95%CI: 49.1%-62.4%) in Pakistan, and 15.6% (95%CI: 12.4%-19.0%) in other countries[88]. The rate of HCV infection in each LD population of each country was strongly correlated with HCV prevalence among their GP. The authors concluded that their findings highlight how the role of this infection in liver diseases is a reflection of its background level in the GP[88]. Moreover, in countries like Egypt and Pakistan, high rates of infections among various populations with LDs may support the contribution of HCV to the occurrence of liver disease[9,10]. On the other hand, a significantly lower HCV rate has been reported for Iranian patients with liver-related conditions (7.5%, 95%CI: 4.3%-11.4%)[13]. Another systematic review underlined the different etiology of HCC in countries of the Eastern Mediterranean region; Four-fifths of HCC patients in Egypt and half of the patients in Pakistan were infected with HCV; however, this value was as low as 8.5% for Iranian patients[80].

Our study had several limitations. Almost all of OCI reports (34 of 37) were from Iran and Egypt, and we did not find any data from 21 countries in the M and E region. Our study is also limited by the number of available documents for both healthy subjects and specific at-risk populations, such as IDUs, HIV-positive persons, and thalassemia or hemophilia patients. Other limitations of our review were the quality of retrieved evidence as well as the representativeness of the target populations. The findings of the majority of studies were based on examination of less than 100 consecutive samples selected by a non-random convenience sampling method. There was a wide heterogeneity in OCI rates even within specific subpopulations; nonetheless, there was no evidence that study location, data collection date, the detection technique of HCV RNA, patients’ HCV serostatus, and sex-group representation in the sample affected the prevalence rates. Despite these shortcomings, we found a large amount of data in two countries, which contributed to the lowest and highest rate of chronic HCV infections in the region (namely, Iran and Egypt, respectively) that allowed us to conduct an analysis among different population categories and settings.

CONCLUSION

Our systematic review and meta-analysis quantified high levels of OCI prevalence, especially across risk populations in M and E countries. Recommendations include more appropriate OCI screening programs to target individuals who are at high risk for HCV infection, especially the patients undergoing dialysis and those with cryptogenic liver diseases. Besides, further investigations are needed regarding OCI among other risk populations, such as HIV- and HBV-infected subjects, IDUs, and thalassemia and hemophilia patients.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Occult hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (OCI) is defined as the presence of HCV genome in the liver samples or peripheral blood mononuclear cells despite a negative test for serum viral RNA. OCI, a common condition worldwide, might be associated with significant morbidities such as liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. No review has yet been performed to provide a pooled estimate for the OCI prevalence rate in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean (M and E) countries, a region with the highest rates of HCV infection in the world.

Research motivation

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we tried to characterize a clear feature of OCI epidemiology in 26 countries of the M and E region based on documents found by searching international and regional electronic sources as well as some local grey literature. We hope our findings help researchers to perform more investigations on diagnosis, management, and control of OCI, particularly in high-risk populations such as patients with chronic liver disease, multi-transfused patients, those infected with HIV, injecting drug users, etc.

Research objectives

The main objective of this review is to provide pooled mean estimates of the OCI rate and assess the contribution of potential variables on the between-study heterogeneity in the M and E region. The results would help professionals, investigators and policy makers to organize suitable activities regarding OCI, particularly in high-risk patients.

Research methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed following PRISMA guidelines. A comprehensive search of electronic databases was conducted up to June 2020 in the Web of Science, PubMed, SCOPUS, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, the Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region, Scientific Information Database, Iranian Database of publication (Magiran), and Iranian Databank of Medical Literature. Also some conference abstracts and all references from bibliographies of retrieved articles were manually reviewed. Forest plots were applied to demonstrate the point prevalence rates and the 95% confidence intervals, and subgroup and meta-regression analyses were applied to identify the factors contributing to heterogeneity between surveys.

Research results

Thirty-seven studies involving 5200 participants from Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey were analyzed. The overall pooled prevalence rate of OCI was 10.04%. The pooled rate among healthy populations was 4.79%, but the rate was much higher among patients with hematologic disorders (19.57%), HIV-positive subjects (12.95%), patients with chronic liver diseases (12.04%), and multi-transfused patients (8.71%). The rate of OCI was not significantly related to the country, disease subpopulations, year of study, the method of HCV RNA detection, sample size, patients’ HCV serostatus and sex, and no significant change was detected in the OCI rate over time (P > 0.05).

Research conclusions

This review and meta-analysis demonstrates high rates of OCI prevalence, especially across risk populations in the M and E region. Some appropriate OCI screening programs are recommended to target individuals who are at risk of HCV infection.

Research perspectives

According to this systematic review and meta-analysis, further investigations are required in order to collect more data on the OCI frequency in M and E countries other than Egypt and Iran, two nations with the highest and lowest rates of chronic HCV infection in the region, respectively. Moreover, large scale studies are needed to evaluate OCI prevalence among less studied populations such as injecting drug users, HBV-infected patients, and thalassemia and hemophilia patients.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors deny any conflict of interest.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: October 5, 2020

First decision: November 16, 2020

Article in press: December 8, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Iran

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Elshaarawy O S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Mohammad Reza Hedayati-Moghaddam, Blood Borne Infections Research Center, Academic Center for Education, Culture and Research (ACECR), Razavi Khorasan Branch, Mashhad 91779-49367, Iran. drhedayati@acecr.ac.ir.

Hossein Soltanian, Blood Borne Infections Research Center, Academic Center for Education, Culture and Research (ACECR), Razavi Khorasan Branch, Mashhad 91779-49367, Iran.

Sanaz Ahmadi-Ghezeldasht, Blood Borne Infections Research Center, Academic Center for Education, Culture and Research (ACECR), Razavi Khorasan Branch, Mashhad 91779-49367, Iran.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, 2016–2021. Towards ending viral hepatitis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/hepatitis/strategy2016-2021/ghss-hep/en .

- 2.Castillo I, Pardo M, Bartolomé J, Ortiz-Movilla N, Rodríguez-Iñigo E, de Lucas S, Salas C, Jiménez-Heffernan JA, Pérez-Mota A, Graus J, López-Alcorocho JM, Carreño V. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in patients in whom the etiology of persistently abnormal results of liver-function tests is unknown. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:7–14. doi: 10.1086/380202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austria A, Wu GY. Occult Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2018;6:155–160. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2017.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartolomé J, López-Alcorocho JM, Castillo I, Rodríguez-Iñigo E, Quiroga JA, Palacios R, Carreño V. Ultracentrifugation of serum samples allows detection of hepatitis C virus RNA in patients with occult hepatitis C. J Virol. 2007;81:7710–7715. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02750-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daef EA, Makhlouf NA, Ahmed EH, Mohamed AI, Abd El Aziz MH, El-Mokhtar MA. Serological and Molecular Diagnosis of Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Hepatitis C Chronic Liver Diseases. Egypt J Immunol. 2017;24:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carreño V, Bartolomé J, Castillo I, Quiroga JA. Occult hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections. Rev Med Virol. 2008;18:139–157. doi: 10.1002/rmv.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin H, Chen X, Zhu S, Mao P, Zhu S, Liu Y, Huang C, Sun J, Zhu J. Prevalence of occult hepatitis C virus infection among blood donors in Jiangsu, China. Intervirology. 2016;59:204–210. doi: 10.1159/000455854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castillo I, Bartolomé J, Quiroga JA, Barril G, Carreño V. Long-term virological follow up of patients with occult hepatitis C virus infection. Liver Int. 2011;31:1519–1524. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Kanaani Z, Mahmud S, Kouyoumjian SP, Abu-Raddad LJ. The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Pakistan: systematic review and meta-analyses. R Soc Open Sci. 2018;5:180257. doi: 10.1098/rsos.180257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kouyoumjian SP, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ. Characterizing hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Egypt: systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1661. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17936-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carreño V, Bartolomé J, Castillo I, Quiroga JA. New perspectives in occult hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2887–2894. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i23.2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO) Global hepatitis report, 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en .

- 13.Mahmud S, Akbarzadeh V, Abu-Raddad LJ. The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Iran: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Sci Rep. 2018;8:150. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18296-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harfouche M, Chemaitelly H, Kouyoumjian SP, Mahmud S, Chaabna K, Al-Kanaani Z, Abu-Raddad LJ. Hepatitis C virus viremic rate in the Middle East and North Africa: Systematic synthesis, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0187177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helaly GF, Elsheredy AG, El Basset Mousa AA, Ahmed HKF, Oluyemi AES. Seronegative and occult hepatitis C virus infections in patients with hematological disorders. Arch Virol. 2017;162:63–69. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramezani A, Eslamifar A, Banifazl M, Keyvani H, Razeghi E, Ahmadi FL, Amini M, Gachkar L, Bavand A, Aghakhani A. Occult HCV Infection in Hemodialysis Patients with Elevated Liver Enzymes. J Arak Uni Med Sci. 2014;16:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muazzam AG, Qureshi S, Mansoor A, Ali L, Iqbal M, Siddiqi S, Khan KM, Mazhar K. Occult HCV or delayed viral clearance from lymphocytes of Chronic HCV genotype 3 patients after interferon therapy. Genet Vaccines Ther. 2011;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1479-0556-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, Baker P, Smith E, Buchbinder R. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahyesh-Esfandiary R, Sadigh ZA, Esghaei M, Bastani MN, Donyavi T, Najafi A, Fakhim A, Bokharaei-Salim F. Detection of HCV genome in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of Iranian seropositive and HCV RNA negative in plasma of patients with beta-thalassemia major: Occult HCV infection. J Med Virol. 2019;91:107–114. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makvandi M, Khalafkhany D, Rasti M, Neisi N, Omidvarinia A, Mirghaed AT, Masjedizadeh A, Shyesteh AA. Detection of Hepatitis C virus RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with abnormal alanine transaminase in Ahvaz. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2014;32:251–255. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.136553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaghloul H, El-Sherbiny W. Detection of occult hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus infections from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Immunol Invest. 2010;39:284–291. doi: 10.3109/08820131003605820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Shazly Y, Hemida K, Rafik M, Al Swaff R, Ali-Eldin ZA, GadAllah S. Detection of occult hepatitis C virus among healthy spouses of patients with HCV infection. J Med Virol. 2015;87:424–427. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gad YZ, Mouas N, Abdel-Aziz A, Abousmra N, Elhadidy M. Distinct immunoregulatory cytokine pattern in Egyptian patients with occult Hepatitis C infection and unexplained persistently elevated liver transaminases. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2012;6:24–28. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.95046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohamed EA, Elballat MAE, El-Awdy MMK, Ali AA-E. Hepatitis C Virus in Peripheral Mononuclear Cells in Patients on Regular Hemodialysis. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2017;67:547. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donyavi T, Bokharaei-Salim F, Khanaliha K, Sheikh M, Bastani MN, Moradi N, Babaei R, Habib Z, Fakhim A, Esghaei M. High prevalence of occult hepatitis C virus infection in injection drug users with HIV infection. Arch Virol. 2019;164:2493–2504. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayadi A, Nafari AH, Sakhaee F, Rajabi K, Ghaderi Y, Rahimi Jamnani F, Vaziri F, Siadat SD, Fateh A. Host genetic factors and clinical parameters influencing the occult hepatitis C virus infection in patients on chronic hemodialysis: Is it still a controversial infection? Hepatol Res. 2019;49:605–616. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdelsalam M, Tawfik M, Reda EM, Eldeeb AA, Abdelwahab A, Zaki ME, Abdelkader Sobh M. Insulin Resistance and Hepatitis C Virus-Associated Subclinical Inflammation Are Hidden Causes of Pruritus in Egyptian Hemodialysis Patients: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Study. Nephron. 2019;143:120–127. doi: 10.1159/000501409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Rehewy MS, Hamed HB, Tony EA, Amin MM, Yassin AS. Interleukin-10 Level in Occult Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Hemodialysis Patient. Egypt J Med Microbiol. 2015;38:1. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozlem ZG, Alper S. Investigation of occult Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C in hemodialysis patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents . 2017;50:S37. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheikh M, Bokharaei-Salim F, Monavari SH, Ataei-Pirkooh A, Esghaei M, Moradi N, Babaei R, Fakhim A, Keyvani H. Molecular diagnosis of occult hepatitis C virus infection in Iranian injection drug users. Arch Virol. 2019;164:349–357. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-4066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashrafi Hafez A, Baharlou R, Mousavi Nasab SD, Ahmadi Vasmehjani A, Shayestehpour M, Joharinia N, Ahmadi NA. Molecular epidemiology of different hepatitis C genotypes in serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in jahrom city of iran. Hepat Mon. 2014;14:e16391. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.16391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jamshidi S, Bokharaei-Salim F, Esghaei M, Bastani MN, Garshasbi S, Chavoshpour S, Dehghani-Dehej F, Fakhim S, Khanaliha K. Occult HCV and occult HBV coinfection in Iranian human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. J Med Virol. 2020;92:3354–3364. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amin MA, Abdel-Wahab KS, MoAmerica AA. Occult HCV in Egyptian volunteer blood donors. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2018;50:103. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abd Alla MDA, Elibiary SA, Wu GY, El-Awady MK. Occult HCV Infection (OCI) Diagnosis in Cirrhotic and Non-cirrhotic Naïve Patients by Intra-PBMC Nested Viral RNA PCR. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2017;5:319–326. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2017.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naghdi R, Ranjbar M, Bokharaei-Salim F, Keyvani H, Savaj S, Ossareh S, Shirali A, Mohammad-Alizadeh AH. Occult Hepatitis C Infection Among Hemodialysis Patients: A Prevalence Study. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16:510–513. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.M. Occult hepatitis C virus infection among chronic liver disease patients in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e225. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abdelrahim SS, Khairy R, Esmail MA, Ragab M, Abdel-Hamid M, Abdelwahab SF. Occult hepatitis C virus infection among Egyptian hemodialysis patients. J Med Virol. 2016;88:1388–1393. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ali NK, Mohamed RR, Saleh BE, Alkady MM, Farag ES. Occult hepatitis C virus infection among haemodialysis patients. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2018;19:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Idrees M, Lal A, Malik FA, Hussain A, Rehman Iu, Akbar H, Butt S, Ali M, Ali L, Malik FA. Occult hepatitis C virus infection and associated predictive factors: the Pakistan experience. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:442–445. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keyvani H, Bokharaei-Salim F, Monavari SH, Esghaei M, Nassiri Toosi M, Fakhim S, Sadigh ZA, Alavian SM. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in candidates for liver transplant with cryptogenic cirrhosis. Hepat Mon. 2013;13:e11290. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.11290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serwah AHA, Mohamed WS, Serwah M, Edreis A, El Zaydi A. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in haemodialysis unit: a single-center experience. Egypt J Hosp Med 2014; 56: 280-288. [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Shishtawy S, Sherif N, Abdallh E, Kamel L, Shemis M, Saleem AA, Abdalla H, El Din HG. Occult Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Hemodialysis Patients; Single Center Study. Electron Physician. 2015;7:1619–1625. doi: 10.19082/1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nafari AH, Ayadi A, Noormohamadi Z, Sakhaee F, Vaziri F, Siadat SD, Fateh A. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in hemophilia patients and its correlation with interferon lambda 3 and 4 polymorphisms. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;79:104144. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.104144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eslamifar A, Ramezani A, Ehteram H, Razeghi E, Ahmadi F, Amini M, Banifazl M, Etemadi G, Keyvani H, Bavand A, Aghakhani A. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in Iranian hemodialysis patients. J Nephropathol. 2015;4:116–120. doi: 10.12860/jnp.2015.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bokharaei-Salim F, Keyvani H, Monavari SH, Alavian SM, Madjd Z, Toosi MN, Mohammad Alizadeh AH. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in Iranian patients with cryptogenic liver disease. J Med Virol. 2011;83:989–995. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rezaee Zavareh MS, Alavian SM, Karimisari H, Shafiei M, Saiedi Hosseini SY. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Hepat Mon. 2014;14:e16089. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.16089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ayadi A, Nafari AH, Irani S, Mohebbi E, Mohebbi F, Sakhaee F, Vaziri F, Siadat SD, Fateh A. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in patients with beta-thalassemia major: Is it a neglected and unexplained phenomenon? J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:11908–11914. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Askar HY, Elhadidy MB, Mesbah MR, Nasser H. MoAmerica, Marei KF, El-Karef A. Occult Hepatitis C virus Infection vs Chronic Hepatitis C among Egyptian Patients with Persistently Abnormal Liver- Function Tests of Unknown Etiology. Egypt J Med Microbiol . 2010;19:53. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mekky MA, Sayed HI, Abdelmalek MO, Saleh MA, Osman OA, Osman HA, Morsy KH, Hetta HF. Prevalence and predictors of occult hepatitis C virus infection among Egyptian patients who achieved sustained virologic response to sofosbuvir/daclatasvir therapy: a multi-center study. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:273–279. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S181638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El-Moselhy EA, Abd El-Aziz A, Atlam SA, Mnsour RH, Amin HH, Kabil TH, El-Khateeb AS. Prevalence and risk factors of overt-and occult hepatitis C virus infection among chronic kidney disease patients under regular hemodialysis in Egypt. Egypt J Hosp Med . 2015;61:653–669. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yakaryilmaz F, Gurbuz OA, Guliter S, Mert A, Songur Y, Karakan T, Keles H. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections in Turkish hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2006;28:729–735. doi: 10.1080/08860220600925602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdelmoemen G, Khodeir SA, Abou-Saif S, Kobtan A, Abd-Elsalam S. Prevalence of occult hepatitis C virus among hemodialysis patients in Tanta university hospitals: a single-center study. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018;25:5459–5464. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0897-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eldaly OM, Elbehedy EM, Fakhr AE, Lotfy A. Prevalence of Occult Hepatitis C Virus in Blood Donors in Zagazig City Blood Banks. Egypt J Med Microbiol . 2016;25:1. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Youssef SS, Nasr AS, El Zanaty T, El Rawi RS, Mattar MM. Prevalence of occult hepatitis C virus in egyptian patients with chronic lymphoproliferative disorders. Hepat Res Treat. 2012;2012:429784. doi: 10.1155/2012/429784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aboalam HA, Rashed H-AG, Mekky MA, Nafeh HM, Osman OA. Prevalence of occult hepatitis C virus in patients with HCV-antibody positivity and serum HCV RNA negativity. Journal of Current Medical Research and Practice. 2016;1:12. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bastani MN, Bokharaei-Salim F, Keyvani H, Esghaei M, Monavari SH, Ebrahimi M, Garshasebi S, Fakhim S. Prevalence of occult hepatitis C virus infection in Iranian patients with beta thalassemia major. Arch Virol. 2016;161:1899–1906. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2862-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farahani M, Bokharaei-Salim F, Ghane M, Basi A, Meysami P, Keyvani H. Prevalence of occult hepatitis C virus infection in Iranian patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. J Med Virol. 2013;85:235–240. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yousif MM, Elsadek Fakhr A, Morad EA, Kelani H, Hamed EF, Elsadek HM, Zahran MH, Fahmy Afify A, Ismail WA, Elagrody AI, Ibrahim NF, Amer FA, Zaki AM, Sadek AMEM, Shendi AM, Emad G, Farrag HA. Prevalence of occult hepatitis C virus infection in patients who achieved sustained virologic response to direct-acting antiviral agents. Infez Med. 2018;26:237–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bokharaei-Salim F, Keyvani H, Esghaei M, Zare-Karizi S, Dermenaki-Farahani SS, Hesami-Zadeh K, Fakhim S. Prevalence of occult hepatitis C virus infection in the Iranian patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Med Virol. 2016;88:1960–1966. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yaghobi R, Kazemi MJ, Geramizadeh B, Malek Hosseini SA, Moayedi J. Significance of Occult Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Liver Transplant Patients With Cryptogenic Cirrhosis. Exp Clin Transplant. 2020;18:206–209. doi: 10.6002/ect.2017.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taherkhani R, Farshadpour F. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Iran. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10790–10810. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i38.10790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rezaee-Zavareh MS, Hadi R, Karimi-Sari H, Hossein Khosravi M, Ajudani R, Dolatimehr F, Ramezani-Binabaj M, Miri SM, Alavian SM. Occult HCV Infection: The Current State of Knowledge. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17:e34181. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.34181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pham TN, Michalak TI. Occult hepatitis C virus infection and its relevance in clinical practice. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2011;1:185–189. doi: 10.1016/S0973-6883(11)60130-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rezaee-Zavareh MS, Ramezani-Binabaj M, Einollahi B. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in dialysis patients: does it need special attention? Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2015;26:368–369. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.152523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dolatimehr F, Khosravi MH, Rezaee-Zavareh MS, Alavian SM. Prevalence of occult HCV infection in hemodialysis and kidney-transplanted patients: a systematic review. Future Virol . 2017:12: 315. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carreño V. Seronegative occult hepatitis C virus infection: clinical implications. J Clin Virol. 2014;61:315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rezaee-Zavareh MS, Einollahi B. Treatment of occult hepatitis C virus infection: does it need special attention? Hepat Mon. 2014;14:e16665. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.16665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alavian SM, Behnava B, Keshvari M, Salimi S, Mehrnoush L, Pouryasin A, Sharafi H, Gholami Fesharaki M. The effect of interleukin 28-b alleles on the prevalence of occult HCV infection in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with sustained virologic response. The 5th Tehran Hepatitis Conference 2013 May 15-17; Tehran, Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Makhlough A, Haghshenas M, Ahangarkani F, MoAmericavi T, Davoodi L. Occult HCV infection in hemodialysis patients. Viral Hepatitis Congress 2017 Dec 14-15; Sari, Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eslamifar A, Ramezani A, Ossar S, Banifazl M, Keyvani H, Aghakhani A. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in Candidates of renal transplantion. The 23rd Iranian Congress on Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine 2015 Jan 12-16; Tehran, Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rezaee Zavareh MS, Alavian SM, Shafiei M, Saiedi Hosseini SY. Occult hepatitis C virus infection in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. The 5th Tehran Hepatitis Conference; 2013 May 15-17; Tehran, Iran. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mollaei HR, Ghasroldashti Z, Arabzadeh SA. Evaluation frequency of occult hepatitis C virus infection in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection, Kerman; Iran. Int J Res Pathol Microbiol . 2017;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bozkurt I, Aygen B, Gokahmetoglu S, Yildiz O. Hepatitis C and occult hepatitis C infection among hemodialysis patients from central Anatolia. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2014;8:435. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gad YZ, Ahmad NA, MoAmerica N, Farag RE, Abdel-Aziz AA, Abousmra NM, Elhadidy MA. Occult hepatitis C infection: the prevalence and profile of its immunoregulatory cytokines. Egypt Liver J. 2012;2:108–112. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Anber N, Abd El Salam M, Abd El Wahab AM, Zaki MS. Prevalence of Occult Hepatitis C in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients in Mansoura University Hospital, Egypt. Int J Adv Pharm, Biol Chem. 2016;5:73. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saad Y, Zakaria S, Ramzy I, El Raziky M, Shaker O, elakel W, Said M, Noseir M, El-Daly M, Abdel Hamid M, Esmat G. Prevalence of occult hepatitis C in egyptian patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Open J Intern Med. 2011;1:33. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chaabna K, Cheema S, Abraham A, Alrouh H, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Mamtani R. Systematic overview of hepatitis C infection in the Middle East and North Africa. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3038–3054. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i27.3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Blach S, Sanai FM. HCV Burden and Barriers to Elimination in the Middle East. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2019;14:224–227. doi: 10.1002/cld.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alavian SM, Haghbin H. Relative Importance of Hepatitis B and C Viruses in Hepatocellular Carcinoma in EMRO Countries and the Middle East: A Systematic Review. Hepat Mon. 2016;16:e35106. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.35106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chemaitelly H, Mahmud S, Kouyoumjian SP, Al-Kanaani Z, Hermez JG, Abu-Raddad LJ. Who to Test for Hepatitis C Virus in the Middle East and North Africa? Hepatol Commun. 2019;3:325–339. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mirminachi B, Mohammadi Z, Merat S, Neishabouri A, Sharifi AH, Alavian SH, Poustchi H, Malekzadeh R. Update on the Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection Among Iranian General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hepat Mon. 2017;17:e42291. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barril G, Castillo I, Arenas MD, Espinosa M, Garcia-Valdecasas J, Garcia-Fernández N, González-Parra E, Alcazar JM, Sánchez C, Diez-Baylón JC, Martinez P, Bartolomé J, Carreño V. Occult hepatitis C virus infection among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2288–2292. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Su Y, Norris JL, Zang C, Peng Z, Wang N. Incidence of hepatitis C virus infection in patients on hemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hemodial Int. 2013;17:532–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2012.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun J, Yu R, Zhu B, Wu J, Larsen S, Zhao W. Hepatitis C infection and related factors in hemodialysis patients in china: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2009;31:610–620. doi: 10.1080/08860220903003446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harfouche M, Chemaitelly H, Mahmud S, Chaabna K, Kouyoumjian SP, Al Kanaani Z, Abu-Raddad LJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus among hemodialysis patients in the Middle East and North Africa: systematic syntheses, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145:3243–3263. doi: 10.1017/S0950268817002242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ashkani-Esfahani S, Alavian SM, Salehi-Marzijarani M. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among hemodialysis patients in the Middle-East: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:151–166. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mahmud S, Chemaitelly H, Al Kanaani Z, Kouyoumjian SP, Abu-Raddad LJ. Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Populations With Liver-Related Diseases in the Middle East and North Africa. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4:577–587. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]