Abstract

Background:

Kidney transplantation (KT), a treatment option for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), is associated with longer survival and improved quality of life compared with dialysis. Inequities in access to KT, and specifically, living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT), have been documented in Canada along various demographic dimensions. In this article, we review existing evidence about inequitable access and barriers to KT and LDKT for patients from Indigenous communities in Canada.

Objective:

To characterize the current state of literature on access to KT and LDKT among Indigenous communities in Canada and to answer the research question, “what factors may influence inequitable access to KT among Indigenous communities in Canada.”

Eligibility criteria:

Databases and gray literature were searched in June and November 2020 for full-text original research articles or gray literature resources addressing KT access or barriers in Indigenous communities in Canada. A total of 26 articles were analyzed thematically.

Sources of evidence:

Gray literature and CINAHL, OVID Medline, OVID Embase, and Cochrane databases.

Charting methods:

Literature characteristics were recorded and findings which described rates of and factors that influence access to KT were summarized in a narrative account. Key themes were subsequently identified and synthesized thematically in the review.

Results:

Indigenous communities in Canada experience various barriers in accessing culturally safe medical information and care, resulting in inequitable access to KT. Barriers include insufficient incorporation of Indigenous ways of knowing and being in information dissemination and care for ESKD and KT, spiritual concerns, health beliefs, logistical hurdles to accessing care, and systemic mistrust resulting from colonialism and systemic racism.

Limitations:

This review included studies that used various methodologies and did not assess study quality. Data on Indigenous status were not reported or defined in a standardized manner. Indigenous communities are not homogeneous and views on organ donation and KT vary by individual.

Conclusions:

Our scoping review has identified potential barriers that Indigenous communities may face in accessing KT and LDKT. Further research is urgently needed to better understand barriers and support needs and to develop strategies to improve equitable access to KT and LDKT for Indigenous populations in Canada.

Keywords: living donor kidney transplantation, end-stage kidney disease, kidney transplantation, deceased donor kidney transplantation, healthy equity, access to care, social determinants of health, Indigenous peoples

Abrégé

Contexte:

La transplantation rénale (TR), une des options de traitement de l’insuffisance rénale terminale (IRT), est associée à une meilleure qualité de vie et à une prolongation de la survie comparativement à la dialyse. Au Canada, les inégalités dans l’accès à la transplantation et plus particulièrement à la transplantation d’un rein provenant d’un donneur vivant (TRDV) ont été documentées selon diverses dimensions démographiques. Cet article fait état des données existantes sur les inégalités d’accès à la TR et à la TRDV des patients canadiens d’origine autochtone.

Objectifs:

Caractériser les données publiées sur les taux de TR et de TRDV chez les Canadiens d’origine autochtone et répondre à la question de recherche « Quels facteurs pourraient mener à un accès inéquitable à la TR pour les autochtones du Canada? ».

Critères d’admissibilité:

Les bases de données et la littérature grise ont été passées en revue en juin et novembre 2020 à la recherche d’articles de recherche originaux (texte intégral) ou de ressources de la littérature grise traitant de l’accès à la TR ou des obstacles rencontrés par les autochtones au Canada. En tout, 26 articles ont été analysés de façon thématique.

Sources:

La littérature grise et les bases de données CINAHL, OVID Medline, OVID Embase et Cochrane.

Méthodologie:

Les caractéristiques tirées de la littérature ont été consignées et les conclusions décrivant les taux de TR et les facteurs influençant l’accès ont été résumées sous forme de compte rendu. Les principaux thèmes ont été dégagés puis synthétisés thématiquement.

Résultats:

Les communautés autochtones du Canada rencontrent divers obstacles dans l’accès à des informations et des soins médicaux adaptés à leur culture, ce qui entraîne un accès inéquitable à la TR. Parmi ces obstacles, on note l’intégration insuffisante des façons d’être et de faire autochtones dans la prestation de soins et dans la diffusion d’informations sur l’IRT et la TR, des préoccupations d’ordre spirituel, des croyances en matière de santé, des obstacles logistiques dans l’accès aux soins, et une méfiance bien intégrée résultant du colonialisme et du racisme systémique.

Limitations:

Cette revue inclut de la documentation dont la méthodologie varie, et la qualité des études retenues n’a pas été évaluée. Les données sur le statut d’Autochtone n’étaient pas consignées ou définies de façon normalisée. Les communautés autochtones ne sont pas homogènes, les avis individuels sur le don d’organes et la TR pourraient varier.

Conclusions:

Cet examen de la portée a permis de cerner les obstacles dans l’accès à la TR et à la TRDV rencontrés par les patients autochtones du Canada. Il est urgent de poursuivre la recherche afin de mieux comprendre les obstacles et les besoins de soutien, et pour élaborer des stratégies visant un meilleur accès à la TRDV pour les autochtones du Canada.

Introduction

Patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) need dialysis or transplantation to survive.1,2 In 2018, more than 40 000 Canadians were living with ESKD, and 2045 patients were active on the kidney transplantation (KT) waitlist.3 Kidney transplantation provides longer life expectancy, improves quality of life, and is less expensive compared with dialysis.4-10 Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) is associated with shorter waiting times and longer graft and patient survival compared with deceased donor kidney transplantation (DDKT); therefore, from a medical and societal perspective, LDKT is the treatment of choice for many patients with ESKD.4 However, KT and LDKT are underused in Canada.1 Furthermore, groups marginalized by race and ethnicity experience substantial inequities in accessing LDKT that have not been fully characterized.11,12

Canada prides itself as one of the most culturally diverse countries in the Western world. According to the 2016 national census, Canada has a foreign-born population of 7 540 830 (21.9% of the total population) and 4.9% of the population identifies as Indigenous.13,14 Canada’s Indigenous population includes First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people and represents one of the largest populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in the country.13,14 Indigenous peoples are the original inhabitants of present-day Canada and called its landmass home long before European settlers colonized the continent in the 15th century. This colonization led to the cultural genocide of Indigenous communities.15,16 Indigenous peoples were disenfranchised, forced to give up their resource-rich land and relocate to confined reserves, stripped of their culture and identity through the residential schooling system, and ultimately had their treaty and human rights violated.16 These events continue to reverberate through present-day experiences and have profound impacts on the lives of the more than 1.6 million Indigenous peoples living across Canada today.16

Although this article focuses on Indigenous communities, we refer to multiple communities in this set of reviews using the terminology of “populations marginalized by race and ethnicity” to demonstrate the complexity of racial and ethnic identities and the ways in which personal identities and the socially constructed identities which are conferred upon individuals impact their interactions in society in a hierarchical manner.17 This terminology recognizes that non-white-presenting individuals are often marginalized by both race—which is a social construct that differentially categorizes people mainly based on physical features18—and ethnicity—which encapsulates cultural traditions, practices, and beliefs.19 These concepts and terminology are evolving, and their usage reflects our current understanding and approach.

The World Health Organization defines health as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being.”20 Individuals belonging to populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada—and specifically Indigenous communities—are known to inequitably experience poorer health than white and non-Indigenous populations, partly stemming from inequitable access to health care.21,22 In this review, access to health care refers to the opportunity that individuals have to use health care services that are appropriate to and fulfill their needs.23 Access is determined by multiple factors including the approachability, acceptability, availability, affordability, and appropriateness of health care services and the ability of individuals to perceive, seek, reach, pay for, and engage with health care services.23 This review characterizes any shortcomings in the aforementioned dimensions related to organ donation and KT as “barriers,” whereas measures such as “willingness to donate” can be considered an aspect of the acceptability of organ donation and KT.23

Only a few studies have assessed inequitable access to kidney care among Indigenous communities in Canada. The incidence and prevalence of ESKD are almost 3 times higher in Indigenous populations than in non-Indigenous populations in Canada.24 Indigenous patients are more likely to have an earlier onset of chronic kidney disease (CKD), to have diabetes either as a comorbid condition or as the cause of their CKD, and to travel further to receive kidney care compared with non-Indigenous patients.24-27 There is also a higher prevalence of severe CKD among Indigenous patients compared with non-Indigenous patients in Canada.25-27 While it has been noted that Indigenous peoples have substantially reduced access to KT and LDKT,12,24 the specific factors leading to this inequitable access have not been fully characterized or understood. Furthermore, there have been few targeted efforts to improve equitable access to KT and LDKT for Indigenous communities in Canada.

The aim of this scoping review is to characterize the current state of literature on access to KT and LDKT among Indigenous communities in Canada and to answer the research question, “what factors may influence inequitable access to KT among Indigenous communities in Canada.” While the review explores the broader topic of KT, there is a focus on LDKT due to the larger disparity in access to LDKT compared with DDKT among populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada. A scoping review summarizing data on other communities marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada is presented in a separate publication to allow for an exploration of evidence without the word limit constraints of a single publication.

A scoping review was conducted to identify and map out the available evidence and knowledge gaps on rates of KT and LDKT and the key factors that result in inequitable access to KT among populations marginalized by race and ethnicity. By exploring the potential structural and psychosocial barriers to accessing KT that patients face, we wish to inform focused research in this area and the development of culturally safe health care practices —those which recognize and address the roles of colonialism, racism, personal biases, and power dynamics in disadvantaging the health of populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada.28 Although we focused on Indigenous peoples in Canada, some of the findings may be relevant to Indigenous peoples or communities marginalized by race and ethnicity in other jurisdictions.

Methods

A comprehensive literature review on access to KT among populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada—including Indigenous, East Asian, South Asian, and African, Caribbean, and Black communities—was conducted. The scoping review was conducted in adherence to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for scoping reviews.29 A comprehensive search strategy was initially developed for Ovid MEDLINE using a combination of database-specific subject headings and text words for the 3 concepts of organ donation/transplant and ethnic minorities and Canada. No limits were applied. The search strategy was then customized for each database. Searches were executed in the following databases on June 22, 2020: Ovid MEDLINE ALL, Ovid Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Ovid), and CINAHL with Full Text (EBSCO). Additional search methods included searching the reference lists of the included studies. See Supplement for database search strategies.

An additional search of the gray literature was conducted in November 2020. Gray literature is defined as literature “which is produced on all levels of government, academics, business and industry in print and electronic formats, but which is not controlled by commercial publishers”30 and thus encompasses a wide range of formats including but not limited to institutional reports, conference abstracts, newsletters, theses, and presentations.31 Relevant national, provincial, and local authorities and institutions related to organ donation and KT were identified and their websites were comprehensively searched for gray literature related to the research topic. A manual search through relevant sections of each website was conducted, and the search bar was also used to identify additional resources that may not have been located in the manual search. Conference abstracts were identified from the database search conducted in June 2020. Searches were also conducted using Advanced Google Search and in the following databases: New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report, Theses Canada, Health Canada, and Publications Canada. Additional resources were identified in consultation with authors I.M. and M.S. See Supplement for gray literature search strategies.

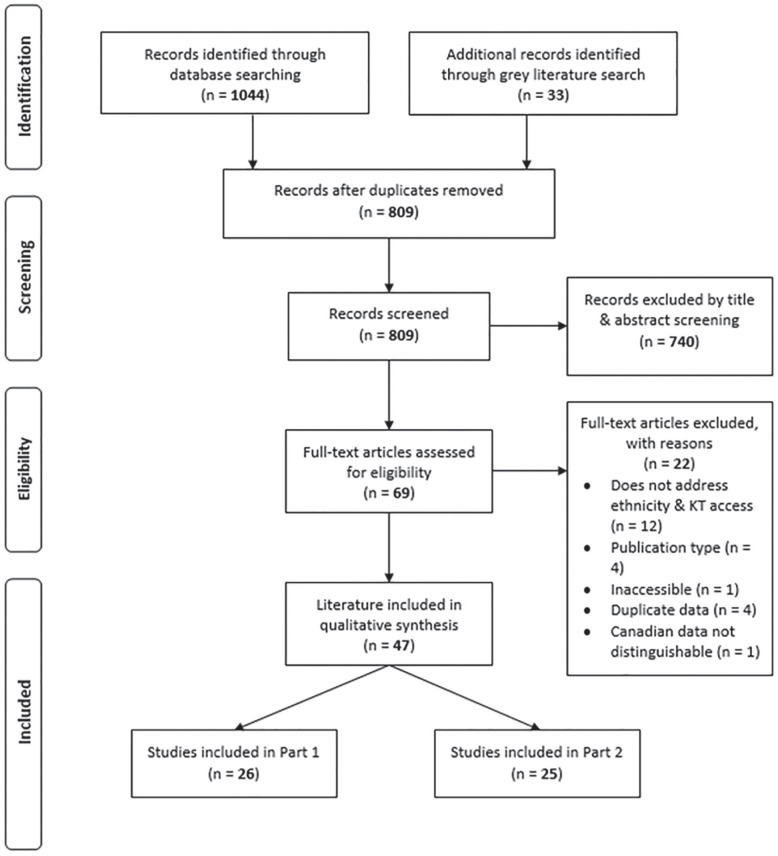

The search retrieved 809 unique titles, including 33 additional gray literature resources related to the research question. Titles, abstracts, and full text were screened by N.E-D. for inclusion criteria. Studies were included if they were full-text original research articles or gray literature resources, if they included at least one of the Canadian populations of interest, and if they were related to the topics of KT or organ donation, ethnicity, and transplant access, barriers or inequities. As the purpose of the scoping review is to map out existing evidence and identify knowledge gaps on the research topic, the quality of data in the included literature was not assessed. The review protocol for this article is not registered.

Characteristics of the included literature were entered into a spreadsheet, including author, year of publication, publication source, study objective and design, literature type, data source, and population. The KT and LDKT rates and key findings which described factors that influence access to KT reported in the included literature were summarized in this review for Indigenous communities in Canada. Findings of each included study were initially summarized in a narrative account. Key findings related to rates of KT and LDKT and themes related to factors that influence access to KT for Indigenous communities were subsequently identified. Findings were then synthesized thematically and grouped accordingly in the review.

Results

The full text of the 26 literature resources that fit the inclusion criteria for the scoping review and included Indigenous populations in Canada was reviewed in detail (Figure 1). Of the included literature, 85% were published in the last 20 years of this review (2000-2020), whereas 19% were published in the last 5 years. Much of the included literature reported national data (42%) with others reporting data from Alberta (12%), British Columbia (12%), Manitoba (12%), Saskatchewan (12%), and Ontario (8%). Approximately 69% of the peer-reviewed studies employed a retrospective study design, whereas 25% used qualitative methodology and 6% used mixed methods. Most of the gray literature resources were in the form of data reports (33%), theses (17%), and conference presentations (17%). While the focus of the review is on KT and LDKT, 15% of the included literature explored the broader question of access to organ donation and transplantation. Key findings in the included literature were summarized (Table 1); rates of KT and LDKT are presented followed by a description of the following themes which represent the main barriers identified: (1) knowledge about KT and kidney disease; (2) religion and spirituality; (3) social, cultural, and family considerations; and (4) concerns related to systemic factors.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study screening and inclusion.

Note. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1.

Summary of Findings of Included Studies.

| Study | Population of interest | Study design | Literature type | Data source | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al32 | Indigenous patients with ESKD | Qualitative | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Nephrology health care professionals across Canada | Remote living location poses difficulties in providing and accessing care. Low socioeconomic status and inadequate health system resourcing further disadvantages Indigenous patients in accessing KT. |

| Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation33 | Indigenous peoples in Canada | Cross-sectional | Data Report | Sample of Canadian residents | Indigenous participants were less likely than non-Indigenous participants to reject the statement “the organ and tissue donation process could exploit people of colour, First Nations people or other minority groups” |

| Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation33 | Indigenous community | Qualitative | Data Report | Indigenous communities in Winnipeg and Saskatoon | Common knowledge of organ donation, support of prevention vs transplant. Power of educating each other through sharing personal experiences in transplant. Importance of ceremony, elder support, and storytelling in decision-making. Giving and receiving as part of the freedom of life. Conflict between traditional beliefs and benefits of donation (eg, passing on culture). Importance of knowing about the donor/recipient in feeling comfort about the organ donated/received may stem from experiences of racism. Attitudes and beliefs about organ donation are sacred, personal decisions often formed within families and communities, especially with elders. Resistance to Western medicine due to colonialism. |

| Canadian Institute for Health Information1 | Indigenous patients with ESKD | Retrospective | Data Report | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | Between 2002 and 2011, Indigenous peoples in Canada were 3 times as likely to be new patients receiving treatment for ESKD or to be receiving treatment than non-Indigenous peoples. Indigenous patients were less likely than non-Indigenous patients to receive KT (27% vs 42%, respectively). |

| Can-SOLVE CKD Network34 | Indigenous community | N/A | Project Summary | Unspecified | In Saskatchewan, Indigenous patients represent 16% of the province’s population but make up half of the patients on dialysis. It is understood that the lack of cultural adaptation and translation of existing educational tools on ESKD treatment options may prevent patients from being able to make informed decisions about ESKD treatment options. |

| Davison and Jhangri35 | Indigenous community | Mixed-Methods | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Indigenous communities in Alberta | Less than half of participants reported willingness to donate organs or those of loved ones after death. Reasons not to donate included belief that dead should be left in peace and need to enter spiritual world with an intact body. Support for organ donation prioritized value of life and needs of community. Traditional beliefs seen as supportive of organ donation, with living donation able to benefit community directly. |

| Dyck and Tan36 | Indigenous patients with ESKD | Retrospective | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | In Saskatchewan, nondiabetic Indigenous patients with ESKD were almost as likely as their non-Indigenous counterparts to receive KT. Diabetic Indigenous patients with ESKD were half as likely as their non-Indigenous counterparts to receive KT. |

| Gill37 | Communities marginalized by ethnicity | N/A | Conference Presentation | Unspecified | Cultural or religious objections to donation, mistrust, and a lack of understanding of the donation process may result in disparate access to KT for communities marginalized by ethnicity. |

| Government of Alberta38 | Indigenous organ transplant recipients | Retrospective | Data Report | Alberta First Nations Information Governance Center | In Alberta between 2006 and 2017, out of the average of 307 transplants conducted in the province per year, 12 were on Indigenous patients. Approximately 60% of transplants received by Indigenous patients were kidney transplants in comparison to 45% for non-Indigenous patients. |

| Matsuda-Abedini et al39 | Indigenous pediatric KT recipients | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | BC Children’s Hospital | Lower rates of preemptive KT in Indigenous pediatric patients. |

| Mollins40 | Indigenous KT recipients | Qualitative | Thesis | KT recipients in Manitoba | Reluctance to accept living donation because of a concern that the donor’s remaining kidney would become diseased and they would eventually develop CKD. Challenges in obtaining transportation to urban and local health care centers for treatment. Fearing kidney graft rejection interfered with patients’ freedom to return home (due to lack of specialized medical support in remote northern communities), find employment, and make a life for their family posttransplant. The need to be under constant medical supervision posttransplant noted as a disadvantage of the process, but a “small price to pay.” |

| Molzahn et al41 | Indigenous community | Qualitative | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Coast Salish community in British Columbia | General lack of knowledge of organ donation system in BC, not commonly discussed in community. Fatalistic beliefs and need for intact body to continue spiritual journey against transplant intervention, and organ donation seen to interfere with death rituals. Organ donation thought to potentially cause transfer of spirit to recipient. Greater comfort in donating to known recipient. Generational differences in attitudes toward donation. Context of frustration with administration of health care services to Indigenous communities, experiences of racism in health care, distrust in health care system leads to unease/fear about going through organ donation. |

| Ontario Renal Network (2020) | Indigenous patients with CKD | N/A | Webpage | Unspecified | Experiences of poverty, significant travel times to receive treatment, and limited access to health care services are challenges for Indigenous patients with CKD in Ontario in accessing appropriate treatment. |

| Promislow et al42 | Indigenous KT recipients | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | Likelihood of KT for Indigenous patients age 18-40 was half that of whites. Likelihood of KT for Indigenous patients age 51-60 was 35% less than whites, and no significant difference for patients >60. Likelihood of LDKT in Indigenous patients age 18-40 was 68% less than whites, Indigenous patients age 41-50 was 70% less than whites; Indigenous patients age 51-60 was 56% less, and same for patients >60. |

| Samuel et al43 | Indigenous pediatric patients with ESKD | Observational Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Pediatric ESRD Database | Indigenous pediatric patients experience longer time from start of RRT to first KT than white pediatric patients. Indigenous patient were 64% less likely to receive LDKT and 38% less likely to receive DDKT than white patients with the same time elapsed since start of dialysis. Patients living more than 150 km from pediatric renal care center were less likely than those living closer to receive KT. |

| Schaubel et al44 | ACB, East Asian, South Asian, and Indigenous KT recipients | Retrospective | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | Sex disparities in KT access in Canada more pronounced for black, South Asian, and Indigenous patients and less pronounced for white and East Asian patients. White and East Asian men are 18 and 23% more likely to receive KT than women, and black, South Asian, and Indigenous men are 66%, 67%, and 42% more likely to receive KT than women. |

| Schulz45 | Indigenous caregivers of children with ESKD | Qualitative | Thesis | Indigenous caregivers | Challenges in receiving KT included adapting to a new community and being uprooted from familiar surroundings and support networks upon relocation to an urban center to receive KT and financial challenges of living off-reserve. |

| Smith46 | Indigenous living kidney donor | Autoethnography | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | N/A | Experience as health care provider helped in navigating transplant system. Smudges and healing circles used to relieve stress, gain sense of community support, and prepare donor for transplant. Familial experience with ESKD as disincentive to pursuing dialysis. Feeling of dread associated with sterile, cold, medicalized environment. Remote living made journey to dialysis center difficult, but relocation posed challenges in work and being away from community. Financial strain created by difficulties in obtaining reimbursement for expenses of appointments and convalescence posttransplant through FNHIB. |

| Tonelli et al47 | Indigenous patients with ESKD | Cross-sectional | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Patients on hemodialysis in Alberta | Adjusted likelihood of referral for KT assessment did not differ between Indigenous and non-Indigenous patients on dialysis, no difference in time on dialysis to referral, rate of preemptive referral, or transplant eligibility. Indigenous patients referred for transplant less likely to be active on waitlist than non-Indigenous patients, with longer times from dialysis start to waitlisting. Indigenous patients half as likely as non-Indigenous patients to be waitlisted. |

| Tonelli et al48 | Indigenous patients with ESKD | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | Adjusted likelihood of DDKT and LDKT lower amongst Indigenous patients than white patients. Adjustment for residence location did not significantly influence likelihood of DDKT or LDKT for Indigenous patients. |

| Tonelli et al49 | Indigenous patients with ESKD | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | Indigenous race associated with lower likelihood of KT compared with white patients. |

| Vescera50 | Indigenous patients with ESKD | N/A | News Article | Informal audit | In Saskatchewan, Indigenous patients comprise 16% of the provincial population but make up 50% of the patients with kidney disease and only 15% of those who receive KT. Beliefs among traditional knowledge people around the need to have a whole body to enter the spirit world may hamper interest in organ donation among Indigenous peoples. |

| Wardmann51 | Indigenous patients with ESKD | N/A | Conference Presentation | Unspecified | Indigenous patients have rates of ESKD that are 3.5 times higher than non-Indigenous patients. Indigenous patients with ESKD are less likely to be placed on the KT waiting list, more likely to wait longer for KT, and less likely to receive KT than non-Indigenous patients. |

| Yeates et al52 | Indigenous KT recipients | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | Indigenous patients had lower crude KT rates than white patients, although the proportion of LDKT was slightly higher for Indigenous than white recipients in Canada. Lower adjusted DDKT and LDKT rates in Indigenous patients. Longer DDKT and LDKT wait time for Indigenous than white patients. |

| Yeates et al12 | ACB, East Asian, South Asian, and Indigenous patients with ESKD | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | Indigenous patients had lower adjusted LDKT rates compared with white patients, with disparity worsening over time. |

| Yoshida et al53 | ACB, East Asian, South Asian, and Indigenous KT recipients | Retrospective | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | BC Transplant Database | Caucasians represented 65% of total KT recipients and Indigenous patients represented 4.1% of total KT recipients in the province. KT recipients exhibited the most racial heterogeneity compared with other organ transplant groups. |

Note. ESKD = end-stage kidney disease; ESRD = end-stage renal disease; KT = kidney transplantation; CKD = chronic kidney disease; LDKT = living donor kidney transplantation; DDKT = deceased donor kidney transplantation; ACB = African, Caribbean, and Black; RRT = renal replacement therapy; FNHIB = First Nations and Inuit Health Branch.

The included articles indicate that Indigenous communities generally have a lower likelihood of receiving KT and LDKT compared with non-Indigenous patients. A variety of factors related to knowledge, religion, spirituality, culture, family, and systems influence and sometimes pose barriers to Indigenous patients and communities in accessing organ donation, KT, and LDKT.

Rates of KT and LDKT

Indigenous peoples in Canada receive disproportionately fewer KTs than non-Indigenous individuals; however, the reasons for this disparity are complex and poorly understood.12,49,51 Between 2002 and 2011, Indigenous patients across Canada were 3 times more likely to be incident or prevalent patients receiving treatment for ESKD than non-Indigenous patients, but were less likely than non-Indigenous patients to receive KT.51,54 At a provincial level, it is estimated that while Indigenous people represent 16% of the population of Saskatchewan, they comprise 50% of the patients on dialysis and only 15% of those who receive KT.34,50 Indigenous patients represented only 4.1% of all KT recipients in British Columbia between 1992 and 1997,53 and were more than 50% less likely to receive a KT12,49 and 49% to 64% less likely to receive LDKT compared with white patients in Canada.12,43,48 In Alberta, an average of 12 out of the 307 yearly transplants conducted between 2006 and 2017 were performed on Indigenous patients; 60% of those were KTs, whereas KTs represented 45% of the transplants performed on non-Indigenous patients.55 Diabetic Indigenous patients with ESKD in Saskatchewan were half as likely as diabetic non-Indigenous patients to receive KT,36 and in British Columbia, Indigenous pediatric patients with ESKD had lower preemptive KT rates compared with their non-Indigenous counterparts.39 One multinational study52 found that in Canada, the United States, New Zealand, and Australia, Indigenous patients had significantly lower KT rates and longer wait times compared with white patients. Furthermore, a Canadian study42 found that the likelihood of DDKT and LDKT was 30% to 70% lower in Indigenous patients than in white patients.

Studies exploring transplant referral among Indigenous adults and children in Canada suggest that Indigenous patients may experience greater delays in pretransplantation workup compared with non-Indigenous patients.43,47 Indigenous patients with ESKD are also less likely to be placed on the waitlist and more likely to wait longer for transplant than non-Indigenous patients.51 While an analysis by Tonelli et al47 showed that Indigenous patients in Alberta were as likely as white patients to be referred for KT, they were significantly less likely to be activated to the transplant waitlist than non-Indigenous patients. Similar findings were reported for Canadian pediatric patients with ESKD.43

Knowledge About KT and Kidney Disease

One mixed-methods study by Davison and Jhangri35 found that although 83% of Indigenous participants from Alberta were in favor of transplantation, willingness to donate in Indigenous communities was lower than in the general public. Results from this study also indicated that higher education levels were associated with greater willingness to consent to donate the organs of a loved one after death and willingness to donate a kidney to family or friends while alive, but no association with willingness to donate a kidney to a stranger.35 Focus group consultations with Indigenous communities in Manitoba and Saskatchewan revealed a need for education on the topic of organ donation in Indigenous communities, especially regarding donor eligibility criteria and what happens to removed organs.33 Participants noted the power of educating one another through sharing personal experiences of donation and transplant with community members.33 An example of this storytelling was documented in an autoethnography by Smith,46 in which she emphasized a general willingness to donate in the community and additionally described how her experience as a health care professional provided her with an advantage in navigating the health care system during her kidney donation to her son. Focus group participants also remarked that the lack of knowledge about organ donation and transplantation in Indigenous communities is exacerbated by mixed feelings and beliefs about discussing the topic in their communities.33 A project led by the Can-SOLVE CKD Network noted that the lack of cultural adaptation and translations in Indigenous languages of existing educational tools on ESKD treatment options may also hinder patients’ ability to make informed decisions about their treatment.34

Religion and Spirituality

Although Indigenous spiritual beliefs regarding organ donation differ from community to community, they vary within communities as well. A study in Alberta35 reported that the reasons participants cited for not donating organs after death included beliefs that the dead should be left in peace and that it is important to enter the spiritual world with an intact body. However, only a small percentage of participants reported that their religious or cultural beliefs influenced their views on organ donation and transplantation. Other traditional beliefs were thought to support the notion of organ donation, as donation and transplant were seen as an effective use of the knowledge that the Creator provided.35 Similar concerns were noted in qualitative interviews with Coast Salish peoples living in British Columbia in relation to body wholeness as well as the transfer of the spirit during the course of a transplant.41 Vescera expanded on these concerns when describing how beliefs held by traditional knowledge people around the need to have a whole body to enter the spirit world may hamper interest in organ donation among Indigenous communities in Saskatchewan.50 In addition, values related to death and dying, including an acceptance of fate, were important considerations that shaped attitudes toward organ donation among Indigenous communities.41

In focus groups, those who held traditional Indigenous values viewed life as sacred and as a gift from the Creator that should be respected and honored.33 Ceremony and ritual were identified as important aspects of traditional Indigenous beliefs; decisions on organ donation and transplantation were considered sacred and would require guidance from the spirit world through prayer and ceremony and from elders through stories told in Indigenous languages.33 From the perspective of Smith,46 smudges and healing circles were considered important practices for relieving stress and supporting and preparing the donor for transplant. Giving and receiving were also considered part of the freedom of having life, and both practices, in the context of organ donation, had the potential to honor life if performed with respect.33 It was noted that the unique nature, history, and spirit of the donor organ needed to be recognized more respectfully than current Western medical practices are perceived to do, which may also imply not interfering with the body after death.33

Social, Cultural, and Family Considerations

A qualitative study41 found that family and community were key potential influences in decision-making around organ donation. Accordingly, participants felt that family members should be consulted on all significant decisions. Although some participants regarded organ donation as a personal decision, they emphasized discussing such issues with family as an important cultural practice.41 Similar findings were reported from focus groups held with Indigenous peoples in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, where participants remarked that donation and transplantation choices were considered sacred, personal decisions typically made within a family.33 Regardless of personal beliefs, Indigenous participants emphasized respect for individual decisions while also expressing support for those who made decisions about donation or transplantation that were different from their own.33

Reluctance to accept or donate organs without knowing anything about the donor or recipient is a factor various studies have noted.33,41 The desire to know more about the potential transplant recipient may be related to experiences of racism and colonialism, as evidenced by one participant who noted, “I do not want to look through a white person’s eyes.”33 However, it was also evident that the Indigenous cultures represented in these studies placed great value on helping others, especially family or community members. In this context, organ donation was noted to provide the transplant recipient with an opportunity to raise their grandchildren and pass on their Indigenous culture.33,41 However, Indigenous KT recipients in Manitoba also noted a reluctance to pursue LDKT out of concern that the donor would eventually develop CKD and subsequently experience the same negative health outcomes as them.40

Related to the notion that cultural and spiritual objections to donation may result in disparate access to KT,37 Indigenous patients with ESKD have indicated that the lack of acceptance of transplantation by older Indigenous people was a factor that influenced their decisions regarding KT.32 These findings are corroborated by qualitative data,41 where participants commented that young adults were likely to feel positively about organ donation but older generations would have more difficulty supporting it. In addition to age-related considerations, sex disparities in access to KT persist across communities in Canada, including Indigenous communities, whereby men were more likely to receive KT than women, although reasons for these disparities remain unclear.44 Many participants believe that donation and transplantation should be discussed in communities, but have noted that few opportunities or processes are in place for respectful discussions with families and community members.33,41 In the mixed-methods study by Davison and Jhangri35 several participants acknowledged the importance of self-relevance as a motivation to donate, in line with the previously noted Indigenous values of helping others. In the case of Smith,46 self-relevance came in the form of a family history of ESKD, which gave her a deeper understanding of the anguish and suffering associated with the disease and with dialysis, and a greater incentive to pursuing transplant for her son.

Concerns Related to Systemic Factors

Qualitative studies revealed a lack of trust in the health care system among Indigenous populations in Canada, characterized by resistance to hospitals and to the Western medical establishment, as these are viewed as another form of colonialism that has harmed the health of Indigenous communities.33,41 This mistrust may be a significant contributing factor to the lack of support for organ donation in Indigenous communities.37,41 A national survey of a sample of Canadians found that Indigenous participants were less likely than others to reject the statement “the organ and tissue donation process could exploit people of color, First Nations people or other minority groups,” indicating a strong level of mistrust in how the organ donation system values Indigenous communities.56 Smith outlines some personal experiences of medical mistrust, including feeling dread as a result of being in a cold and sterile medical environment where she did not feel understood, which made it difficult to interact with the health care system comfortably.46 An additional aspect of mistrust may be related to the sentiment of animosity expressed by Indigenous KT recipients in Manitoba around having to be under constant medical supervision posttransplant, although participants understood this as a “small price to pay” for the benefits that KT offered over dialysis.40

In addition to barriers within the health care system, systemic inequities and logistical barriers associated with the social determinants of health, including poverty, limited access to health care services in remote communities, and geographical distance to transplant centers experienced by many Indigenous communities create further challenges in accessing transplantation.57 Indigenous patients with ESKD are twice as likely to live in lower income neighborhoods than non-Indigenous patients and 40% of Indigenous patients live in remote areas in comparison with only 6% of non-Indigenous patients in Canada.54 Indigenous KT recipients described the lack of specialized medical support in remote northern communities as a barrier to returning home after receiving their KT.40 Additional social and economic barriers to accessing KT are exemplified by the inefficacies of the federal First Nations and Inuit Health Branch Non-Insured Health Benefits program which were found to impose additional financial strain on Indigenous patients in accessing transplantation by complicating reimbursement processes and causing great frustration.41,46 While Smith noted that living on a remote island posed a great challenge to receiving dialysis treatment, relocating to the mainland so that her son could receive his transplant also meant that they were away from the “cultural heart” of their community.46 Schulz expanded on the challenges of relocation when describing the experiences of Indigenous caregivers of children with ESKD in having to relocate to an urban center for their child to receive KT and being uprooted from familiar surroundings and their support networks.45 Caregivers faced additional financial challenges when relocating, as they were no longer able to receive financial forms of support that were limited in policy to individuals living on-reserve.45 Geographic challenges faced by Indigenous patients were further described by Samuel et al43 who showed that Indigenous children across Canada living far (>150 km) from the nearest pediatric kidney care center were less likely to receive KT than those living closer. An analysis of national data additionally showed that 20% of Indigenous patients were required to travel more than 250 km to receive treatment for ESKD versus 5% of non-Indigenous patients, and Indigenous patients generally had to travel distances 4 times greater to receive treatment for ESKD.54 Tonelli et al48 also confirmed that the likelihood of living in a remote residence location was significantly higher among Indigenous patients on dialysis compared with white patients in Canada. Transportation challenges further complicate remote living, as Indigenous KT recipients from Manitoba expressed difficulty in obtaining transportation to urban and local health care centers to receive treatment.40 However, residence location did not explain the lower rates of KT for Indigenous patients with ESKD in all studies.48 In contrast, a qualitative study on Indigenous peoples in Canada32 found that remote living made it more difficult for health care practitioners to provide adequate care and education to patients with ESKD and also created logistical problems and social concerns for patients who must relocate to receive treatment and/or undergo transplant evaluation. Physical distance alone does not necessarily capture the remoteness of Indigenous patients, as participants in this study32 noted that low socioeconomic status and mobility issues exacerbated the challenges of living in a remote community.

Discussion

This scoping review highlights the peer-reviewed and gray evidence base which characterizes the inequitable access to KT and LDKT experienced by patients who belong to Indigenous communities in Canada. Research across the country has shown that patients from Indigenous communities are, on average, substantially less likely to receive KT or LDKT than non-Indigenous patients12,34,42,43,47-54; however, provincial analyses have shown that some Indigenous communities experience higher KT rates than non-Indigenous communities.38

Canadian research has shown several factors which uniquely influence attitudes, opinions, and behaviors regarding the acceptability of organ donation and KT in specific Indigenous communities, as well as beliefs and concerns which are shared across communities. While personal and anecdotal experience with KT nevertheless provides individuals and communities with a greater understanding of the concept, gaps in knowledge about the organ donation process and donor eligibility and safety remain.33 However, there is a specific need to increase and enhance the delivery of culturally appropriate education using Indigenous ways of knowing, such as through storytelling from elders and community members. It is crucial to acknowledge that Indigenous ways of knowing and being are conducive to health. The Can-SOLVE CKD Network project on “Improving Indigenous patient knowledge about treatment options” is one example of an initiative that engages Indigenous communities and patient partners in the co-development of educational materials on ESKD treatment options.58 By incorporating, addressing, and respecting the needs and perspectives of Indigenous peoples, communities can work together to ensure the delivery of culturally appropriate and safe education.

Part of the provision of effective, culturally appropriate education starts with understanding specific concerns and views regarding the acceptability of organ donation in the community. Religious and spiritual views both in support of and against organ donation exist both within and across different Indigenous communities, and these views may change over time and through personal experiences. The importance of ceremony, ritual, and consultation with elders was a unique consideration for some Indigenous community members. Participants emphasized that organ donation decisions which came about through such processes must be respected.33 Some concerns, including the importance of maintaining an intact body after death or worries that organ donation constitutes an interference with or disrespect of the body, spirit, and Creator, were voiced by multiple communities.35,41,50 Ultimately, spiritual and cultural beliefs of charity, generosity, honor, and the ability to enable others to pass on their Indigenous culture by donating an organ were critical supporting values for encouraging organ donation and KT.33 However, the history of colonialism in Canada and the consequent intergenerational trauma experienced by Indigenous peoples were noted to influence the level of comfort that communities had in discussing or accepting organ donation. Negative medical experiences and resistance to Western medical establishments were identified as contributing to a sentiment of medical mistrust, impacting views regarding the appropriateness of health care and organ donation across generations.33,41,46,56 Understanding the historic, lived, and social contextual roots of beliefs related to organ donation and health care in Indigenous communities is a key step in addressing systemic concerns and enabling the provision of culturally safe, equitable care to historically disenfranchised Indigenous communities. Programs such as the BRIDGE to Transplantation Initiative incorporate such understanding. This program works in partnership with Indigenous communities to build community capacity for providing culturally appropriate education and support in navigating the transplant process. Such collaborative efforts are crucial to improve equitable access to LDKT for Indigenous communities across Canada.

Limitations

In this review, we summarized existing literature on access to KT and LDKT in Indigenous communities in Canada; however, its limitations need to be considered. The quality of the included literature has not been systematically evaluated. The reviewed literature employed a wide range of methodologies with their own inherent limitations. Data on Indigenous status were not collected or reported in a standardized manner, nor did all studies state whether Indigenous status was self-identified. We also acknowledge that the Indigenous groups included in this review are very diverse in and of themselves, so attitudes and opinions on organ donation may differ significantly from person to person and are not limited to those documented in the literature.

Conclusions

From the literature reviewed, it is evident that patients with ESKD who belong to Indigenous communities are less likely to receive KT or LDKT than non-Indigenous patients. We saw that various factors may influence inequitable access to KT among Indigenous communities in Canada. While some communities expressed certain unique beliefs and concerns around the acceptability and appropriateness of organ donation and KT, there were also striking similarities in both negative and positive sentiments toward organ donation and KT across Indigenous communities. There is a need to address gaps in knowledge around kidney disease and KT using culturally appropriate methods and Indigenous ways of knowing. While values such as generosity and enabling others to pass on their Indigenous culture were important factors that facilitated acceptance of organ donation and KT, mistrust in the Western medical system and systemic barriers to health care were noteworthy barriers to accessing organ donation, KT, and LDKT for Indigenous communities in Canada. In addition, ongoing research to understand barriers to KT and LDKT experienced by Indigenous communities and determine solutions for addressing these barriers are needed. Going forward, it will be crucial to partner and build meaningful relationships with Indigenous communities to identify how to address concerns around the acceptability, appropriateness, availability, and affordability of organ donation and KT which are rooted in the history of colonialism in Canada. We must work collaboratively to build culturally appropriate and safe strategies which respect and incorporate traditional values, recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, and principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to improve equitable access to KT and LDKT, and overall well-being, for all communities.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cjk-10.1177_2054358121996835 for Barriers to Accessing Kidney Transplantation Among Populations Marginalized by Race and Ethnicity in Canada: A Scoping Review Part 1—Indigenous Communities in Canada by Noor El-Dassouki, Dorothy Wong, Deanna M. Toews, Jagbir Gill, Beth Edwards, Ani Orchanian-Cheff, Mary Smith, Paula Neves, Lydia-Joi Marshall and Istvan Mucsi in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Ethics approval and consent were not obtained as secondary data were used for this scoping review.

Consent for Publication: All co-authors reviewed this final manuscript and consented to its publication.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and materials that support the findings of this scoping review are available from the corresponding author I.M. upon reasonable request.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Ani Orchanian-Cheff  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9943-2692

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9943-2692

Istvan Mucsi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4781-4699

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4781-4699

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Annual Statistics on Organ Replacement in Canada: Dialysis, Transplantation and Donation, 2008 to 2017. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joshi SJJ, J Gaynor J, Ciancio G. Review of ethnic disparities in access to renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2012;26(4):E337-E343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Annual Statistics on Organ Replacement in Canada: Dialysis, Transplantation and Donation, 2009 to 2018. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Groot IB, Veen JI, van der Boog PJ, et al. Difference in quality of life, fatigue and societal participation between living and deceased donor kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2013;27(4):E415-E423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Evans RW, Manninen DL, Garrison LP. The quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. New Engl J Med. 1985;312:553-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Molnar MZ, Novak M, Mucsi I. Sleep disorders and quality of life in renal transplant recipients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41(2):373-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neipp M, Karavul B, Jackobs S. Quality of life in adult transplant recipients more than 15 years after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2006;81:1640-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ortiz F, Aronen P, Koskinen PK. Health-related quality of life after kidney transplantation: who benefits the most. Transpl Int. 2014;27(11):1143-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pinson CW, Feurer ID, Payne JL. Health-related quality of life after different types of solid organ transplantation. Ann Surg. 2000;232(4):597-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Network KSC. Alberta annual kidney care report: prevalence of severe kidney disease and use of dialysis and transplantation across Alberta from 2004–2013. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Health Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mucsi I, Bansal A, Famure O, et al. Ethnic background is a potential barrier to living donor kidney transplantation in Canada: a single-center retrospective cohort study. Transplantation. 2017;101(4):e142-e151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yeates KE, Schaubel DE, Cass A, Sequist TD, Ayanian JZ. Access to renal transplantation for minority patients with ESRD in Canada. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(6):1083-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Statistics Canada. Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity: Key Results From the 2016 Census. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025b-info-eng.htm. Published 2017. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 14. Aboriginal peoples in Canada: key results from the 2016 census. Statistics Canada. Published October 25, 2017. Accessed February 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15. First Nations in Canada. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada; 2017. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1307460755710/1536862806124. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 16. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. https://bettercarenetwork.org/library/social-welfare-systems/child-care-and-protection-policies/honouring-the-truth-reconciling-for-the-future-summary-of-the-final-report-of-the-truth-and. Published 2015. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 17. Nestel S. Colour Coded Health Care: The Impact of Race and Racism on Canadian’s Health. Toronto, ON, Canada: Wellesley Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Let’s talk: racism and health equity [Rev. ed]. Antigonish, NS, Canada: National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, St. Francis Xavier University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. CRRF Glossary of Terms. https://www.crrf-fcrr.ca/en/resources/glossary-a-terms-en-gb-1?letter=e&cc=p. Published 2019. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 20. Constitution of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2005. https://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levy J, Ansara D, Stover A. Racialization and Health Inequities in Toronto. Toronto, ON, Canada: Toronto Public Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Initiative P-CHIR. Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levesque J, Harris M, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: concpetualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2013;12:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Canadian Institute for Health Information. End-Stage Renal Disease Among Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: Treatment and Outcomes. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomas DA, Huang A, McCarron MCE, et al. A retrospective study of chronic kidney disease burden in Saskatchewan’s First Nations people. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nash DM, Dirk JS, McArthur E, et al. Kidney disease and care among First Nations people with diabetes in Ontario: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2019;7(4):E706-E712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gao S, Manns BJ, Culleton BF, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and survival among aboriginal people. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(11):2953-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for English-Speaking People of Caribbean Origin: A Manual for Enhancing the Effectiveness of CBT for English-Speaking People of Caribbean Origin in Canada. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addictions and Mental Health; 2011. https://www.porticonetwork.ca/documents/43843/277768/CBT-Anglophone_English.pdf/ba2f1c1c-5a55-40a9-95f5-000e48abff09. Accessed February 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Commission of the European Communities. Directorate-General Telecommunications IM, and Exploitation of Research. Perspectives on the design and transfer of scientific and technical information: third International Conference on Grey Literature, Jean Monnet Building: GL’97 proceedings. Paper presented at: International Conference on Grey Literature 1997; November 13-14, 1997; Luxembourg. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Document Types in Grey Literature. http://www.greynet.org/greysourceindex/documenttypes.html. Published 2020. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 32. Anderson K, Yeates K, Cunningham J, Devitt J, Cass A. They really want to go back home, they hate it here: the importance of place in Canadian health professionals’ views on the barriers facing Aboriginal patients accessing kidney transplants. Health Place. 2009;15(1):390-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation. Consultation to Explore Peoples’ Views on Organ and Tissue Donation: Discussions with Indigenous Peoples—Summary Report to Participants. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Research team builds relationships to improve Indigenous patients’ knowledge of kidney disease treatment options. Can-SOLVE CKD Network; 2018. https://www.cansolveckd.ca/news/research-team-builds-relationships-to-improve-indigenous-patients-knowledge-of-kidney-disease-treatment-options/. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 35. Davison SN, Jhangri GS. Knowledge and attitudes of Canadian First Nations people toward organ donation and transplantation: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(5):781-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dyck RF, Tan L. Rates and outcomes of diabetic end-stage renal disease among registered native people in Saskatchewan. CMAJ. 1994;150(2):203-208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gill J. Addressing disparities in kidney transplantation. Paper presented at: BC Kidney Days, Vancouver, BC; October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38. First Nations—Health Trends Alberta. Edmonton, AB: Government of Alberta; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Matsuda-Abedini M, Al-AlSheikh K, Hurley RM, et al. Outcome of kidney transplantation in Canadian Aboriginal children in the province of British Columbia. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13(7):856-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mollins C. The impact of urban relocation on native kidney transplant patients and their families: a retrospective study. Winnipeg, MB, Canada: Department of Anthropology, University of Manitoba; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Molzahn AE, Starzomski R, McDonald M, O’Loughlin C. Aboriginal beliefs about organ donation: some Coast Salish viewpoints. Can J Nurs Res. 2004;36(4):110-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Promislow S, Hemmelgarn B, Rigatto C, et al. Young aboriginals are less likely to receive a renal transplant: a Canadian national study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14(1):11-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Samuel SM, Foster BJ, Tonelli MA, et al. Dialysis and transplantation among Aboriginal children with kidney failure. CMAJ. 2011;183(10):E665-E672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schaubel DE, Stewart DE, Morrison HI, et al. Sex inequality in kidney transplantation rates. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(15):2349-2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schulz N. The meaning of caring for a child who has renal failure: a phenomenological study of urban aboriginal caregivers. Winnipeg, MB, Canada: Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Manitoba; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Smith M. Nagweyaab Geebawug: a retrospective autoethnography of the lived experience of kidney donation. CANNT J. 2015;25(4):13-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tonelli M, Chou S, Gourishankar S, et al. Wait-listing for kidney transplantation among Aboriginal hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(6):1117-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Kim AK, et al. Association between residence location and likelihood of kidney transplantation in Aboriginal patients treated with dialysis in Canada. Kidney Int. 2006;70(5):924-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Manns B, et al. Death and renal transplantation among Aboriginal people undergoing dialysis. CMAJ. 2004;171(6):577-582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vescera Z. Doctors and elders unite to pursue equity in organ donations. Saskatoon Starpheonix. June 16. 2020. https://thestarphoenix.com/news/local-news/sask-network-pushes-for-equity-in-organ-donations. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 51. Wardmann D. Chronic kidney disease and aboriginal people: disabling or enabling? Paper presented at BC Nephrology Days, Vancouver, BC; October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yeates KE, Cass A, Sequist TD, et al. Indigenous people in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States are less likely to receive renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2009;76(6):659-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yoshida EM, Partovi N, Ross PL, Landsberg DN, Shapiro RJ, Chung SW. Racial differences between solid organ transplant donors and recipients in British Columbia: a five-year retrospective analysis. Transplantation. 1999;67(10):1324-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. End-Stage Renal Disease among Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: Treatment and Outcomes. Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/en/canadian-organ-replacement-register-corr#_Reports_and_Analyses. Published February, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Alberta Go. First Nations—Health Trends Alberta. Alberta Health, Health Standards, Quality & Performance, Analytics and Performance Reporting Branch; September 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation. Public Awareness and Attitudes on Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Including Donation After Cardiac Death. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ontario Renal Network. First Nations, Inuit & Métis Kidney Care. Published 2020. https://www.ontariorenalnetwork.ca/en/about/our-work/first-nationsinuit-metis. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 58. Can-SOLVE CKD Network. Improving Indigenous Patient Knowledge About Treatment Options. https://www.cansolveckd.ca/research/theme-3/treatment-options. Published 2020. Accessed April 9, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cjk-10.1177_2054358121996835 for Barriers to Accessing Kidney Transplantation Among Populations Marginalized by Race and Ethnicity in Canada: A Scoping Review Part 1—Indigenous Communities in Canada by Noor El-Dassouki, Dorothy Wong, Deanna M. Toews, Jagbir Gill, Beth Edwards, Ani Orchanian-Cheff, Mary Smith, Paula Neves, Lydia-Joi Marshall and Istvan Mucsi in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease