Key Points

Question

Does overminus lens therapy improve distance control in children with intermittent exotropia?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial found that mean distance exotropia control was significantly better among 386 children aged 3 to 10 years treated with overminus spectacles vs nonoverminus spectacles for 12 months; however, after weaning off overminus spectacles, there was little or no difference in distance control between groups. Myopic shift was approximately one-third diopter greater in the overminus than in the nonoverminus group.

Meaning

Overminus lens therapy improved distance exotropia control in children 3 to 10 years of age but was associated with greater myopic shift, and the improved control did not persist after overminus treatment was discontinued.

Abstract

Importance

This is the first large-scale randomized clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness and safety of overminus spectacle therapy for treatment of intermittent exotropia (IXT).

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of overminus spectacles to improve distance IXT control.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial conducted at 56 clinical sites between January 2017 and January 2019 associated with the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group enrolled 386 children aged 3 to 10 years with IXT, a mean distance control score of 2 or worse, and a refractive error between 1.00 and −6.00 diopters (D). Data analysis was performed from February to December 2020.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to overminus spectacle therapy (−2.50 D for 12 months, then −1.25 D for 3 months, followed by nonoverminus spectacles for 3 months) or to nonoverminus spectacle use.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary and secondary outcomes were the mean distance IXT control scores of participants examined after 12 months of treatment (primary outcome) and at 18 months (3 months after treatment ended) assessed by an examiner masked to treatment group. Change in refractive error from baseline to 12 months was compared between groups. Analyses were performed using the intention-to-treat population.

Results

The mean (SD) age of 196 participants randomized to overminus therapy and 190 participants randomized to nonoverminus treatment was 6.3 (2.1) years, and 226 (59%) were female. Mean distance control at 12 months was better in participants treated with overminus spectacles than with nonoverminus spectacles (1.8 vs 2.8 points; adjusted difference, −0.8; 95% CI, −1.0 to −0.5; P < .001). At 18 months, there was little or no difference in mean distance control between overminus and nonoverminus groups (2.4 vs 2.7 points; adjusted difference, −0.2; 95% CI, −0.5 to 0.04; P = .09). Myopic shift from baseline to 12 months was greater in the overminus than the nonoverminus group (−0.42 D vs −0.04 D; adjusted difference, −0.37 D; 95% CI, −0.49 to −0.26 D; P < .001), with 33 of 189 children (17%) in the overminus group vs 2 of 169 (1%) in the nonoverminus group having a shift higher than 1.00 D.

Conclusions and Relevance

Children 3 to 10 years of age had improved distance exotropia control when assessed wearing overminus spectacles after 12 months of overminus treatment; however, this treatment was associated with increased myopic shift. The beneficial effect of overminus lens therapy on distance exotropia control was not maintained after treatment was tapered off for 3 months and children were examined 3 months later.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02807350

This randomized clinical trial evaluates whether wearing followed by weaning off overminus spectacles improves distance control in children 3 to 10 years of age with intermittent exotropia.

Introduction

Overminus lens therapy is a nonsurgical treatment option for childhood intermittent exotropia (IXT), in which an optical correction with more minus power than the cycloplegic refractive error is worn.1,2 Overminus lenses are typically used as a temporary treatment to improve control of IXT in young children before considering surgery3,4,5,6,7 or orthoptics.4,7 Some authors have reported success in maintaining good control and binocular function after gradually decreasing the strength of the overminus lenses over time and ultimately discontinuing the overminus lenses.5,6

Most previous studies of overminus spectacles are retrospective case series or small prospective studies without comparison groups.3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 However, a previous pilot randomized clinical trial found that, compared with observation, short-term (8-week) distance IXT control improved while wearing overminus spectacles of −2.50 diopters (D).11

The present randomized clinical trial of children 3 to 10 years of age evaluated the effectiveness of overminus lens therapy for improving distance IXT control while wearing overminus lenses, after 12 months of overminus treatment, and 3 months after the overminus lens treatment was tapered off. In addition, potential adverse effects on refractive error and symptoms associated with use of overminus spectacles were monitored.

Methods

The study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki12 by the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group at 56 academic- and community-based clinical sites. An independent data and safety monitoring committee provided oversight. The study was designed in 2016 and is listed on ClinicalTrials.gov.13 This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. The full trial protocol is available in Supplement 1. The protocol and informed consent forms, compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, were approved by institutional review boards for each site, and a parent or guardian (hereafter referred to as parent) of each study participant gave written informed consent. Study participants received $50 compensation per visit.

Enrollment

Eligible children were 3 to younger than 11 years of age with cycloplegic spherical equivalent (SE) refractive error between −6.00 D and 1.00 D inclusive, and IXT of moderate or poor control and meeting specified magnitude criteria (Box). Additional eligibility criteria are shown in the Box.

Box. Eligibility Criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Aged 3 to <11 y

-

Intermittent exotropia (manifest deviation) meeting all of the following criteria:

-

At distance: intermittent exotropia or constant exotropia

Mean distance control score of ≥2 points (mean of 3 assessments during the examination)

-

At near: intermittent exotropia, exophoria, or orthophoria

Individual cannot have a score of 5 points on all 3 near assessments of control

Exodeviation at least 15∆ at distance measured by the prism and alternate cover test

Near deviation does not exceed distance deviation by more than 10∆ by prism and alternate cover test (convergence insufficiency type intermittent exotropia excluded)

-

Distance visual acuity (any optotype method) in each eye of 0.4 logMAR (20/50) or better if aged 3 to <4 y and 0.3 logMAR (20/40) or better if ≥4 y

Interocular difference of distance visual acuity ≤0.2 logMAR (2 lines on a logMAR chart)

Refractive error between −6.00-D spherical equivalents (SEs) and 1.00-D SEs (inclusive) in the most myopic or least hyperopic eye based on a cycloplegic refraction performed within the last 2 mo or at the end of the enrollment examination

-

If refractive error (based on cycloplegic refraction performed within last 2 mo or at the end of the enrollment examination) meets any of the following criteria, then prestudy spectacles are required and must have been worn for at least 1 wk prior to enrollment:

SE anisometropia ≥1.00 D

Astigmatism ≥1.50 D in either eye

SE myopia ≥−1.00 D in either eye

-

Prestudy refractive correction, if worn, must meet the following criteria relative to the cycloplegic refraction performed within last 2 mo or at the end of the enrollment examination:

SE anisometropia must be corrected within <1.00 D of the SE anisometropic difference

Astigmatism must be corrected within <1.00 D of full magnitude; axis must be within 10°

SE of spectacles must not meet the definition of substantial overminus (see exclusion criteria)

Gestational age ≥32 wk

Birth weight >1500 g

Parent understands the protocol and is willing to accept randomization to overminus spectacles or nonoverminus spectacles

Parent has home telephone (or access to telephone) and is willing to be contacted by Jaeb Center for Health Research staff and investigator’s site staff

Relocation outside of area of an active Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group site within next 18 mo is not anticipated

Exclusion Criteria

Treatment of intermittent exotropia or amblyopia (other than refractive correction) within the last 4 wk, including vision therapy, patching, atropine, or other penalization

Current contact lens wear

Substantial deliberate overminus treatment within the last 6 mo, defined as spectacles with an overminus of >1.00-D SEs than the cycloplegic refractive error (within 2 mo or at the end of the enrollment examination)

Prior strabismus, intraocular, or refractive surgery (including botulinum toxin injection)

Abnormality of the cornea, lens, or central retina

Down syndrome or cerebral palsy

Severe developmental delay that would interfere with treatment or evaluation (in the opinion of the investigator). Children with mild speech delays or reading or learning disabilities are not excluded

Any disease known to affect accommodation, vergence, and ocular motility such as multiple sclerosis, Graves orbitopathy, dysautonomia, myasthenia gravis, or current use of atropine for amblyopia

Antiseizure medications (eg, carbamazepine [Tegretol, Carbatrol, Epitol, or Equetro], diazepam [Valium or Diastat], clobazam [Frisium or Onfi], clonazepam [Klonopin], lorazepam [Ativan], ethosuximide [Zarontin], felbamate [Felbatol], lacosamide [VIMPAT], gabapentin [Neurontin], oxcarbazepine [Oxtellar XR or Trileptal], phenobarbital, phenytoin [Dilantin or Phenytek], pregabalin [Lyrica], tiagabine [Gabitril], topiramate [Topamax], valproate [Depakote], zonisamide [Zonegran], or vigabatrin [Sabril])

Testing at enrollment was performed through the participant’s habitual correction. Control of the exodeviation was measured at distance (6 m) and near (0.3 m) using the IXT Office Control Score,14 which ranges from 0 (phoria) to 5 (constant exotropia) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Control levels 3 to 5 were assigned based on the duration of manifest exotropia during a 30-second period before any dissociation. If no exotropia was observed during this period, control levels 0 to 2 were assigned based on the longest time to reestablishing fusion following 3 consecutive 10-second periods of dissociation. Control was measured at the beginning, middle, and end (3 tests total) of a 20- to 40-minute office examination, and the mean level was used.15,16,17 The following tests were performed sequentially by the same study-certified examiner (pediatric optometrist, pediatric ophthalmologist, or certified orthoptist): first control assessment; stereoacuity using the Randot Preschool Stereoacuity test (Stereo Optical Co, Inc) at 40 cm; second control assessment; cover-uncover test; prism and alternate cover test (PACT) at distance and near; PACT retesting at distance with −2.00 D lenses over the habitual correction to assess the ratio of accommodative convergence to accommodation; and third control assessment. Distance visual acuity was assessed using an optotype method. Cycloplegic refraction was performed within 2 months prior to enrollment; cycloplegic autorefraction was also performed at clinical sites that had an autorefractor.

In addition, each child completed an IXT Symptom Survey18 to assess IXT-related symptoms, and the parent completed a 7-item Spectacles Symptom Survey to assess issues related to overminus spectacle wear (eg, headache, eyestrain, and looking over glasses). Health-related quality of life was assessed using the Intermittent Exotropia Questionnaire (IXTQ)19,20 for each child (separate version for 5- to 7-year-old children vs ≥8-year-old children) and parent. Participants were randomly assigned 1:1 using a permuted block design stratified by site and distance control (2 to <3, 3 to <4, 4 to 5 points), to either overminus or nonoverminus spectacles.

Treatment Regimens

Participants assigned to the overminus group were prescribed spectacles with −2.50 D added to the spherical power of the cycloplegic refraction to be worn for 12 months. Participants were then weaned by wearing −1.25 D overminus lenses for 3 months, before discontinuing overminus lenses and wearing nonoverminus spectacles until the 18-month visit.

Participants assigned to the nonoverminus group were prescribed spectacles that fully corrected astigmatism, anisometropia, and myopia based on the cycloplegic refraction to be worn for 18 months. For participants with SE hyperopia, the sphere power that resulted in a SE plano lens were prescribed for the less hyperopic eye, with symmetrical reduction in the fellow eye.

To keep participants masked, the spectacle prescription was sealed in an envelope, and spectacle lenses were changed in both treatment groups at 12 and 15 months. In both treatment groups, spectacles were worn full time. No other IXT treatments were allowed unless the participant met motor or stereo deterioration criteria (eTable 2 in Supplement 2), after which treatment was at investigator discretion.

Early Discontinuation of Overminus Lens Therapy

On observing greater myopic shift in the overminus group, the data and safety monitoring committee discontinued overminus lens treatment in November 2019. When implemented in December 2019, the study had completed 345 (89%) 12-month visits, 303 (78%) 15-month visits, and 250 (65%) 18-month visits.

Follow-up Visits

Follow-up visits occurred at 6, 12 (primary outcome), 15, and 18 months (secondary outcome) (±1 month) after randomization. Telephone calls were completed at 1, 3, 9, 13, and 16 months after randomization to verify receipt of new spectacles and to maintain rapport with the family.

At each follow-up visit, the spectacle prescription was verified, and adherence with spectacle wear was rated based on parental report of the percentage of wear time during waking hours: excellent (>75%), good (51%-75%), fair (26%-50%), or poor (≤25%). Participants and parents then completed the symptom and IXTQ surveys. With participants wearing their current (ie, study) spectacles, an examiner masked to treatment group measured near stereoacuity, performed 3 IXT control assessments (at the beginning, middle, and end of the masked examination) at distance and near, the cover-uncover test, and the PACT at distance and near, in the order described for enrollment. If near stereoacuity had worsened by 2 or more octaves from baseline or to nil, it was retested (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). If stereoacuity remained decreased, it was then retested on a subsequent day (within a month) to confirm or refute meeting stereo deterioration criteria. A cycloplegic refraction was performed by an unmasked examiner at 12-month visits; cycloplegic autorefraction was also performed when available at the clinical site.

Statistical Analysis

Assuming an SD of 1.8 points in the IXT control score based on a prior pilot study by members of our group,11 2-sided α = .05, a power of 90%, and up to 10% loss to follow-up, a sample size of 384 (192 per group) was needed to detect a difference in mean 12-month and mean 18-month distance control scores (overminus − nonoverminus), assuming the true mean difference was −0.65 points or larger.

The primary analysis was an intention-to-treat treatment group comparison of mean distance control score after 12 months of treatment using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusting for baseline values of distance control, age, refractive error, and distance (eAppendix in Supplement 2). Multiple imputation using the Markov chain Monte Carlo model21 with baseline adjustment factors (distance control, age, refractive error, and distance PACT) and follow-up control scores was performed to impute missing control scores for each treatment group separately in the primary analysis (eAppendix in Supplement 2). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the effects of missing data handling on study results (eAppendix in Supplement 2). The primary analysis was repeated within baseline subgroups in exploratory analyses.

Using the same ANCOVA model as the primary analysis, the mean 18-month distance control scores were compared between treatment groups. As a sensitivity analysis, the 18-month analysis was repeated, limited to 292 participants who completed the full treatment and weaning period (ie, had completed the 15-month visit) prior to early discontinuation of overminus by the data and safety monitoring committee.

Additional secondary outcomes related to the exodeviation (control and magnitude) and stereoacuity were compared between treatment groups using ANCOVA models adjusted for the baseline level of the outcome. The cumulative probabilities of deterioration by 12 and by 18 months were calculated by treatment group using Cox proportional hazards models.

As a safety outcome, mean 12-month SE cycloplegic refractive error was compared between treatment groups using ANCOVA adjusting for baseline refractive error and age. The risk ratio between treatment groups for the proportion of participants with an increase in SE myopia from baseline to 12 months of higher than 1.00 D was also calculated using the Farrington-Manning score method.22

Item responses for the IXT Child Symptom Survey18 and the Parent Spectacle/Symptom Survey and median scores for the child and parent IXTQ20 components were tabulated. The IXTQ domain scores were compared between treatment groups at 12 and 18 months using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

We adjusted P values to control the false discovery rate23 at 5% separately for IXTQ domain scores and for all other secondary outcomes (eAppendix in Supplement 2). All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Between January 2017 and January 2019, 386 children were enrolled at 56 sites, with 196 children assigned to overminus lens therapy and 190 children to nonoverminus lens treatment. Baseline demographic characteristics (age: mean [SD], 6.3 [2.1] years; range, 3.0-11.0 vs 3.0-10.7 years; sex: 226 [59%] female; 112 [57%] vs 114 [60%] girls) and clinical characteristics appeared similar in the treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Treatment Group.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Overminus | Nonoverminus | |

| Overall | 196 (100) | 190 (100) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 112 (57) | 114 (60) |

| Male | 84 (43) | 76 (40) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 6 (3) | 10 (5) |

| Black/African American | 34 (17) | 28 (15) |

| Hispanic | 31 (16) | 40 (21) |

| White | 113 (58) | 91 (48) |

| Other | 12 (6) | 21 (11) |

| Age at randomization, y | ||

| 3 to <7 | 123 (63) | 120 (63) |

| 7 to <11 | 73 (37) | 70 (37) |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 6.4 (2.0) [3.0 to 11.0] | 6.2 (2.2) [3.0 to 10.7] |

| Refractive error (spherical equivalent), Da | ||

| >0.50 | 58 (30)b | 59 (31)b |

| >−0.75 to 0.50 | 101 (52) | 96 (51) |

| −0.75 to >−3.00 | 29 (15) | 32 (17) |

| ≤−3.00 | 8 (4) | 3 (2) |

| Mean (SD) [range] | −0.02 (1.11) [−6.00 to 1.25] | 0.01 (0.94) [−3.75 to 1.00] |

| Prior nonsurgical treatment of IXT | ||

| None | 126 (64) | 137 (72) |

| Patching only | 53 (27) | 33 (17) |

| Vision therapy only | 10 (5) | 11 (6) |

| Patching plus other | 4 (2) | 6 (3) |

| Other | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Randot Preschool Sterioacuity test score at near, arcsecondsc | ||

| 40-100 | 120 (64) | 112 (61) |

| 200-800 | 52 (28) | 55 (30) |

| Nil | 16 (9) | 16 (9) |

| Median, log (arcseconds) | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Mean distance visual acuityd | ||

| 20/12 to 20/20 | 115 (59) | 112 (59) |

| 20/25 to 20/32 | 70 (36) | 69 (36) |

| 20/40 to 20/50 | 11 (6) | 9 (5) |

| IOD of distance visual acuity, lines (logMAR) | ||

| 0 | 130 (66) | 115 (61) |

| 0.1 | 57 (29) | 61 (32) |

| 0.2 | 9 (5) | 14 (7) |

| Spectacle wear | ||

| Does not wear spectacles | 140 (71) | 142 (75) |

| Wearing spectacles for at least 1 wk | 56 (29) | 48 (25) |

| Exotropiae | ||

| Control at distance | ||

| 0 to <1 | NA | NA |

| 1 to <2 | NA | NA |

| 2 to <3 | 84 (43) | 78 (41) |

| 3 to <4 | 56 (29) | 52 (27) |

| 4 to 5 | 56 (29) | 60 (32) |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 3.2 (1.0) [2 to 5] | 3.2 (1.0) [2 to 5] |

| Control at near | ||

| 0 to <1 | 37 (19) | 46 (24) |

| 1 to <2 | 80 (41) | 65 (34) |

| 2 to <3 | 39 (20) | 44 (23) |

| 3 to <4 | 31 (16) | 27 (14) |

| 4 to 5 | 9 (5) | 8 (4) |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 1.7 (1.1) [0 to 4.7] | 1.6 (1.1) [0 to 4.7] |

| PACT exodeviation, ∆f | ||

| At distance | ||

| No exodeviation (orthophoria) | NA | NA |

| 1-9 | NA | NA |

| 10-15 | 5 (3) | 6 (3) |

| 16-18 | 42 (21) | 22 (12) |

| 19-25 | 86 (44) | 91 (48) |

| 30-35 | 54 (28) | 50 (26) |

| 40-45 | 9 (5) | 19 (10) |

| ≥50 | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Esodeviation | NA | NA |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 25 (7) [15 to 45] | 27 (8) [15 to 50] |

| At nearf | ||

| No exodeviation (orthophoria) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) |

| 1-9 | 27 (14) | 24 (13) |

| 10-15 | 45 (23) | 45 (24) |

| 16-18 | 36 (18) | 29 (15) |

| 19-25 | 57 (29) | 59 (31) |

| 30-35 | 24 (12) | 21 (11) |

| 40-45 | 4 (2) | 8 (4) |

| ≥50 | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Esodeviation | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 18 (9) [0 to 50] | 19 (10) [−4 to 45] |

Abbreviations: D, diopters; IOD, interocular difference; IXT, intermittent exotropia; NA, not applicable; PACT, prism and alternate cover test; ∆, prism diopters.

Spherical equivalent refractive error in more myopic eye if myopic or in less hyperopic eye if hyperopic.

Two participants in the overminus group were not eligible owing to spherical equivalent refractive error in the least hyperopic eye >1.00 D, and 1 participant in the nonoverminus group was ineligible owing to prior strabismus surgery. These ineligible participants were included in the primary analysis.

Log (arcseconds) stereoacuity values range from 1.6 (40 arcseconds) to 3.2 (nil); thus, lower values are better. Eight participants in the overminus group (5%) and 7 in the nonoverminus group (7%) did not understand test instructions to complete the stereotest; therefore, their stereoacuity at baseline was missing.

Mean between 2 eyes.

Mean of 3 assessments performed throughout the examination. Mean distance exotropia control of 2 points or higher (worse) was required for eligibility. Mean near exotropia control of lower than 5 points (ie, could not be constant on all 3 of the measures) was required for eligibility.

PACT at distance was required to be at least 15∆ for eligibility. In addition, near deviation could not exceed distance deviation by more than 10∆ by PACT for eligibility (ie, convergence insufficiency type IXT was excluded). Negative values represent esodeviation.

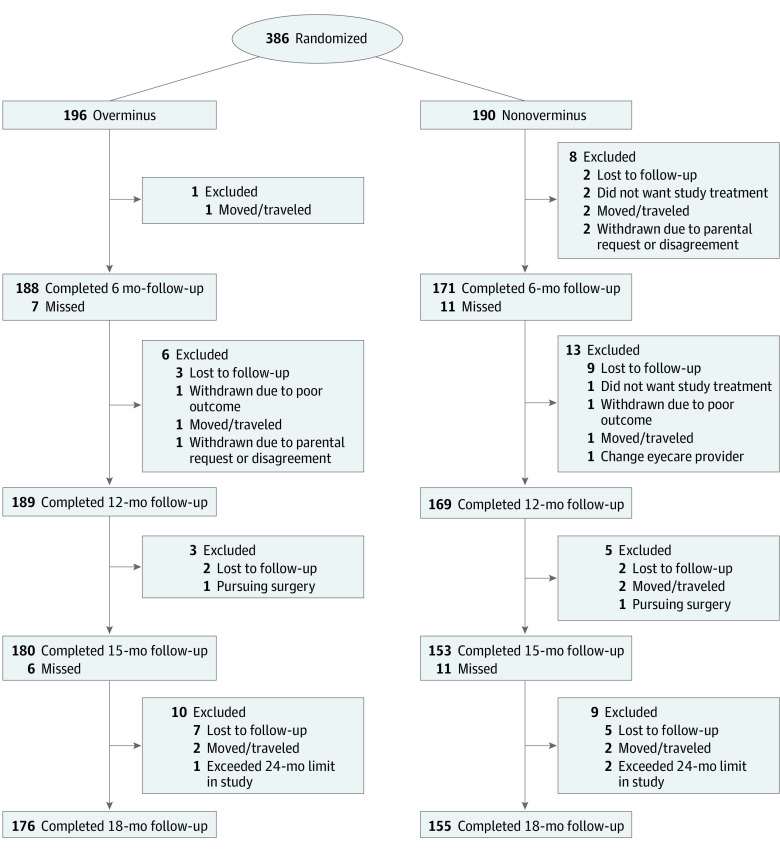

The overall completion rate was 93% for the 12-month follow-up and 86% for the 18-month follow-up. Twelve-month follow-up was incomplete for 7 of 196 participants (4%) in the overminus group and 21 of 190 participants (11%) in the nonoverminus group (Figure). Eighteen-month follow-up was incomplete for 20 of 196 participants (10%) in the overminus group and 35 of 190 participants (18%) in the nonoverminus group (Figure). Of 331 participants who completed the 18-month visit, only 292 (88%) completed the full treatment and weaning protocol. Clinical characteristics of those with incomplete vs complete 18-month follow-up are provided in eTable 3 in Supplement 2. All examiners assessing outcome measures were masked to the participants’ assigned treatment.

Figure. Flow of Participants Through Study.

Completed represents the number of randomized participants who completed the visit. One participant in each treatment group underwent strabismus surgery, with the overminus group participant also discontinuing overminus spectacles. One participant in the nonoverminus group had vision therapy, and 1 participant in the overminus wore a different pair of spectacles at school. Two participants in the nonoverminus group started overminus spectacles after meeting stereoacuity deterioration at the 6-month visit.

Treatment Adherence

Spectacle wear adherence was reported as excellent for 149 children in the overminus group and 144 children in the nonoverminus group, which was 76% of each treatment group, at 12 months (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Two participants in each treatment group received nonstudy IXT treatment before 12 months.

Twelve-Month Efficacy Analyses (Primary Outcome)

The overminus group, wearing their study spectacles, had better mean (SD) distance control after 12 months of treatment (1.8 [1.3] points) compared with the nonoverminus group (2.8 [1.5] points) (adjusted treatment group difference, −0.8 points; 95% CI, −1.0 to −0.5 points; P < .001) (Table 2; eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Mean distance control scores were imputed for 34 participants (10 in overminus and 24 in nonoverminus). Several sensitivity analyses that were completed (eAppendix in Supplement 2) yielded results similar to the primary analysis.

Table 2. Exotropia Control and Secondary Outcomes at Follow-up (Mean of 3 Measurements)a.

| Measure | No. (%) of participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-mo Visit (primary outcome) | 18-mo Visit (secondary outcome) | |||

| Overminus (n = 189) | Nonoverminus (n = 169) | Overminus (n = 176) | Nonoverminus (n = 155) | |

| Distance control score (points) | ||||

| 0 to <1 | 38 (20) | 8 (5) | 21 (12) | 16 (10) |

| 1 to <2 | 60 (32) | 42 (25) | 53 (30) | 38 (25) |

| 2 to <3 | 52 (28) | 47 (28) | 42 (24) | 35 (23) |

| 3 to <4 | 19 (10) | 21 (12) | 20 (11) | 15 (10) |

| 4 to 5 | 20 (11) | 51 (30) | 40 (23) | 51 (33) |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 1.8 (1.3) [0 to 5] | 2.8 (1.5) [0 to 5] | 2.4 (1.5) [0 to 5] | 2.7 (1.6) [0 to 5] |

| Difference, mean (2-sided 95% CI)b,c | −0.8 (−1.0 to −0.5) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.04) | ||

| P value for difference, mean | <.0001 | .09 | ||

| Change from baseline (points)d | ||||

| Mean (SD) [range] | 1.3 (1.4) [−2.3 to 5.0] | 0.5 (1.3) [−3.0 to 4.3] | 0.8 (1.5) [−3.0 to 4.7] | 0.5 (1.6) [−3.0 to 4.7] |

| Improved ≥1 pointc,e | 116 (61) | 71 (42) | 86 (49) | 68 (44) |

| Difference, % (2-sided 95% CI) | 19 (7 to 29) | 4 (−7 to 15) | ||

| P value for difference | .0009 | .61 | ||

| Improved ≥2 pointsc,e | 65 (34) | 24 (14) | 48 (27) | 30 (19) |

| Difference, % (2-sided 95% CI) | 20 (10 to 28) | 8 (−2 to 17) | ||

| P value for difference | .0003 | .18 | ||

| Near control score (points) | ||||

| 0 to <1 | 96 (51) | 64 (38) | 72 (41) | 59 (38) |

| 1 to <2 | 59 (31) | 55 (33) | 60 (34) | 46 (30) |

| 2 to <3 | 21 (11) | 13 (8) | 16 (9) | 18 (12) |

| 3 to <4 | 9 (5) | 17 (10) | 15 (9) | 16 (10) |

| 4 to 5 | 4 (2) | 20 (12) | 13 (7) | 16 (10) |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 1.0 (1.1) [0 to 5] | 1.5 (1.5) [0 to 5] | 1.3 (1.3) [0 to 5] | 1.5 (1.5) [0 to 5] |

| Difference, mean (2-sided 95% CI)b,c | −0.5 (−0.8 to −0.3) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) | ||

| P value for difference, mean | <.0001 | .19 | ||

| Change from baseline (points)d | ||||

| Mean (SD) [range] | 0.7 (1.3) [−3.3 to 3.7] | 0.1 (1.4) [−3.7 to 3.7] | 0.4 (1.4) [−3.7 to 3.7] | 0.1 (1.5) [−4.7 to 3.3] |

| No spontaneous tropia during control testing at distance and neare | 115 (61) | 62 (37) | 85 (48) | 60 (39) |

| Difference, % (2-sided 95% CI)c | 24 (13 to 34) | 9 (−2 to 19) | ||

| P value for difference | .0003 | .18 | ||

| Deterioration (motor or stereo) by specified timef | 5 (1) | 7 (4) | 6 (2) | 16 (7) |

| Randot Preschool Stereoacuity test score, arcsecondsg | ||||

| 40-60 | 101 (56) | 99 (61) | 114 (67) | 97 (65) |

| 100-400 | 66 (36) | 51 (31) | 44 (26) | 40 (27) |

| 800 or Nil | 14 (8) | 12 (7) | 12 (7) | 12 (8) |

| Median, log (arcseconds) | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Mean (SD), log (arcseconds)h | 2.0 (0.4) | 2.0 (0.4) | 1.9 (0.4) | 1.9 (0.4) |

| Range, log (arcseconds) | 1.6 to 3.2 | 1.6 to 3.2 | 1.6 to 3.2 | 1.6 to 3.2 |

| Difference, mean (95% CI)c,i | 0.03 (−0.04 to 0.10) | −0.01 (−0.09 to 0.06) | ||

| P value for difference | .47 | .82 | ||

| Change from baseline, log (arcseconds)j | ||||

| Mean (SD) [range], log (arcseconds) | −0.1 (0.4) [−1.4 to 0.9] | −0.2 (0.4) [−1.4 to 0.6] | −0.2 (0.4) [−1.6 to 1.4] | −0.2 (0.4) [−1.6 to 1.2] |

| PACT exodeviation, ∆ | ||||

| At distance | ||||

| No exodeviation (orthophoria) | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| 1-9 | 17 (9) | 3 (2) | 5 (3) | 3 (2) |

| 10-15 | 30 (16) | 9 (5) | 20 (11) | 10 (6) |

| 16-18 | 38 (20) | 22 (13) | 28 (16) | 23 (15) |

| 19-25 | 73 (39) | 73 (43) | 71 (40) | 64 (41) |

| 30-35 | 25 (13) | 52 (31) | 39 (22) | 40 (26) |

| 40-45 | 3 (2) | 8 (5) | 10 (6) | 11 (7) |

| ≥50 | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Esodeviation | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 3(2) |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 20.0 (9.0) [−2 to 45] | 25.0 (8.0) [0 to 55] | 23.0 (9.0) [−12 to 50] | 24.0 (11.0) [−30 to 80] |

| Difference, mean (95% CI)c,i | −4.2 (−5.7 to −2.6) | 0.2 (−1.8 to 2.2) | ||

| P value for difference | <.001 | .87 | ||

| Change from baseline (∆)j | ||||

| Mean (SD) [range] | −5.0 (7.0) [−33 to 10] | −2.0 (8.0) [−40 to 15] | −1.0 (8.0) [−35 to 20] | −2.0 (8.0) [−36 to 40] |

| At near | ||||

| No exodeviation (orthophoria) | 9 (5) | 3 (2) | 6 (3) | 6 (4) |

| 1-9 | 41 (22) | 31 (18) | 20 (11) | 20 (13) |

| 10-15 | 53 (28) | 27 (16) | 50 (28) | 32 (21) |

| 16-18 | 28 (15) | 30 (18) | 24 (14) | 26 (17) |

| 19-25 | 34 (18) | 50 (30) | 46 (26) | 42 (27) |

| 30-35 | 19 (10) | 18 (11) | 23 (13) | 22 (14) |

| 40-45 | 3 (2) | 7 (4) | 4 (2) | 4 (3) |

| ≥50 | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Esodeviation | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 15.0 (9.0) [−8 to 45] | 18.0 (10.0) [−5 to 55] | 18.0 (10.0) [−12 to 60] | 19.0 (11.0) [−30 to 55] |

| Difference, mean (95% CI)c,i | −3.8 (−5.5 to −2.1) | −0.7 (−2.7 to 1.4) | ||

| P value for difference | <.001 | .61 | ||

| Change from baseline (∆)j | ||||

| Mean (SD) [range] | −4.0 (8.0) [−33 to 16] | 0.0 (9.0) [−27 to 30] | 0.0 (10.0) [−27 to 40] | 1.0 (9.0) [−27 to 30] |

Abbreviations: PACT, prism and alternate cover test; ∆, prism diopters.

Study spectacles were used for outcome testing for 171 participants (90%) in the overminus group and 155 participants (92%) in the nonoverminus group at the 12-month visit and for 157 participants (89%) in the overminus group and 145 participants (94%) in the nonoverminus group at the 18-month visit. Trial frames were used for all other participants.

Difference in mean distance or near control (overminus − nonoverminus) and 95% CIs are from analysis of covariance model, adjusting for baseline distance or near control (respectively), age, spherical equivalent refractive error, and PACT at distance or near.

Three participants (1 in overminus and 2 in nonoverminus groups) at 12 months, and 3 participants (2 in overminus and 1 in nonoverminus groups) at 18 months were excluded from this analysis owing to visits outside the analysis window.

Change is calculated as baseline minus 12 months or minus 18 months; thus, a positive change represents improvement.

Treatment groups were compared using a 2-sided Barnard test.

Definition of deterioration available in eTable 2 in Supplement 2. Percentages shown in table are cumulative probabilities derived from Cox proportional hazards models. At 12 months, the cumulative probabilities were both less than 5%; thus, the groups were not statistically compared. At 18 months, P = .07 for the treatment group difference (derived from the z test).

Stereoacuity was missing for 8 participants (4%) in the overminus and 7 participants (4%) in the nonoverminus group at 12 months and for 6 participants (3%) in the overminus group and 6 participants (4%) in the nonoverminus group at 18 months because they did not understand the test.

The log (arcseconds) stereoacuity values range from 1.6 log (arcseconds) (40 arcseconds) to 3.2 (nil); thus, lower values are better.

Difference in means (overminus − nonoverminus), 95% CIs, and P values were from analysis of covariance models adjusted for the baseline value of the measure.

Change is calculated as the follow-up visit minus baseline; thus, a negative change represents improvement.

Treatment group differences in secondary outcomes favored the overminus group, except for little or no difference in stereoacuity (Table 2). In exploratory analyses, a 12-month treatment effect favoring the overminus group was observed across all baseline subgroups, including baseline distance control, baseline SE refractive error, age, accommodative convergence to accommodation ratio, sex, and race/ethnicity (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

Eighteen-Month Efficacy Analyses

At the 18-month visit (3 months after overminus spectacles were discontinued), the mean distance control was 2.4 points for 176 participants in the overminus group vs 2.7 points in 155 participants in the nonoverminus group (adjusted treatment group difference, −0.2; 95% CI, −0.5 to 0.04; P = .09) (Table 2). Mean distance control scores were imputed for 68 participants (29 in overminus and 39 in nonoverminus). There were little or no differences between treatment groups for secondary outcomes at 18 months (Table 2).

Safety

Based on cycloplegic retinoscopy, the overminus group showed a greater SE myopic change than the nonoverminus group (−0.42 vs −0.04 D; adjusted treatment group difference, −0.37 D; 95% CI, −0.49 to −0.26 D; P < .001). Of 189 children in the overminus group, 33 (17%) had higher than 1.00 D of myopic shift compared with 2 of 169 children (1%) in the nonoverminus group, with a risk ratio of 14.8 (95% CI, 4.0-182.6) (Table 3). The increased myopic shift in the overminus vs nonoverminus groups occurred particularly in children who already had myopia compared with children with emmetropia or hyperopia at baseline (Table 3). Cycloplegic autorefraction data were available in one-third of participants and yielded results similar to the cycloplegic retinoscopy findings (Table 3). The overminus and nonoverminus groups appeared similar in development of esotropia (4 of 189 [2%] vs 4 of 169 [2%]), 2 or more line decrease in visual acuity (12 of 189 [6%] vs 10 of 169 [6%]), and amblyopia treatment prescribed by 12 months (2 of 189 [1%] vs (1 of 169 [1%]).

Table 3. Refractive Error Change Between Baseline and 12 Months.

| Measure | Completing 12 mo, No. (%) | Change in spherical equivalent refractive error from baseline to 12 mo, mean (SD) Da,b | >1 D of spherical equivalent myopic change from baseline to 12 mo, No. (%) | >1 D of spherical equivalent myopic change from baseline to 12 mo in overminus vs nonoverminus groups, risk ratio (95% CI)c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overminus | Nonoverminus | Overminus | Nonoverminus | |||

| No. | 189 | 169 | 189 | 169 | ||

| Overall by cycloplegic refraction | 358 (100) | −0.42 (0.69) | −0.04 (0.46) | 33 (17) | 2 (1) | 14.8 (4.0 to 182.6) |

| Baseline spherical equivalent refractive errord | ||||||

| Myopia | ||||||

| No. | 43 | 44 | 43 | 44 | ||

| −0.50 to −6.00 D | 87 (100) | −1.07 (0.76) | −0.16 (0.57) | 22 (51) | 1 (2) | 22.5 (4.1 to 667.6) |

| Emmetropia | ||||||

| No. | 60 | 48 | 60 | 48 | ||

| −0.375 to 0.375 D | 108 (100) | −0.30 (0.64) | −0.01 (0.41) | 8 (13) | 1 (2) | 6.4 (1.0 to 164.9) |

| Hyperopia | ||||||

| No. | 84 | 77 | 84 | 77 | ||

| 0.50 to 1.00 D | 161 (100) | −0.18 (0.44) | 0.00 (0.41) | 3 (4) | 0 | NAe |

| Overall | ||||||

| No. | 65 | 61 | 65 | 61 | ||

| By cycloplegic autorefractionf | 126 (100) | −0.45 (0.69) | −0.05 (0.66) | 12 (18) | 3 (5) | 3.8 (1.1 to 28.3) |

Abbreviations: D, diopters; NA, not applicable.

Overall treatment group difference of 12-month refractive error (overminus − nonoverminus) equal to −0.37 D (95% CI, −0.49 to −0.26 D). The difference is obtained from an analysis of covariance model adjusted for baseline spherical equivalent refractive error in the most myopic eye and age. P < .001 for treatment group difference. Three children were excluded from analysis owing to visits out of the analysis window.

Refractive error in most myopic eye at baseline.

Exact risk ratio and CIs were obtained from a Farrington-Manning score test and reflect the relative probability of a participant in the overminus group having more than 1.00 D of myopic change at 12 months compared with a participant in the nonoverminus group.

Subgroups do not include 2 ineligible participants who had a refractive error greater than 1.00 D at baseline (1 with 1.125 D, and 1 with 1.25 D).

Among participants who were in the hyperopic group at baseline, 3 participants in the overminus group and 0 participants in the nonoverminus group had myopic shift of more than 1.00 D at 12 months. A risk ratio could not be calculated owing to the denominator of 0.

Overall treatment group difference of 12-month refractive error from cycloplegic autorefraction (overminus − nonoverminus) equal to −0.39 D (95% CI, −0.64 to −0.15 D). Difference obtained from an analysis of covariance model adjusted for baseline refractive error in the most myopic eye and age. P value not reported. One participant with autorefraction was excluded from analysis because the visit was outside the analysis window.

IXT Symptom and Spectacle Symptom Data

At 12 months, the frequency of most IXT symptoms appeared relatively similar between treatment groups, except more children in the overminus group (71 of 189 [38%]) reported that their eyes hurt sometimes or always compared with the nonoverminus group (37 of 169 [22%]) (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). Parent-reported symptom and spectacle data are given in eTable 6 in Supplement 2.

Health-Related Quality of Life Associated With IXT

At 12 months, health-related quality of life was scored as 78.8 (overminus) vs 71.5 (nonoverminus) on the psychosocial subscale, 75.1 (overminus) vs 70.6 (nonoverminus) on the function subscale, and 68.7 (overminus) vs 54.2 (nonoverminus) on the surgery subscale of the parent IXTQ; little or no difference was observed in the child IXTQ scores between treatment groups. At 18 months, there were no treatment group differences in the child or the parent IXTQ scores (eTable 7 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

This randomized clinical trial of 3- to 10-year-old children with IXT found that the overminus group had a better distance IXT control score while wearing overminus spectacles at 1 year after study treatment compared with the nonoverminus group, but this treatment effect did not persist after the participants were weaned off the overminus spectacles. In addition, the overminus group had a greater myopic shift at 12 months compared with the nonoverminus group, with the risk of higher than 1.00 D of myopic shift during this period being approximately 15 times that of the nonoverminus group.

Improved IXT control while wearing overminus spectables has been reported in a previous pilot randomized clinical trial,11 2 prospective observational studies without comparison groups,6,9 and retrospective case series reports.3,5 Aside from the pilot randomized clinical trial, the present trial differs from the previous studies in study design, strength of overminus power used, treatment duration, and outcome measures, making comparisons across studies difficult. The 0.8-point mean improvement in the distance IXT control score while wearing overminus spectacles at 12 months in the present study is nearly identical to the 0.75-point mean improvement found in the previous 8-week pilot randomized clinical trial that evaluated the same overminus lens power.11 Taken together, these 2 studies suggest that there is a relatively fast response to overminus spectacles after treatment initiation, which then appears to remain stable over time, given that IXT control was essentially the same at 8 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months. Exploratory analyses found a 12-month treatment benefit of overminus lens therapy across age, refractive error, distance IXT control, and the ratio of accommodative convergence to accommodation.

In the present study, the treatment benefit observed at 12 months did not persist after the participants were weaned off their overminus lenses. Two retrospective studies5,6 have reported differing success rates of improved control after discontinuation of overminus spectacle therapy; however, neither study had a control group. In the present study, a modest improvement in distance control occurred from baseline to 18 months in both treatment groups, indicating the importance of a control group to differentiate whether the improved control was due to overminus treatment or to other factors, such as spontaneous improvement unrelated to the overminus lens treatment or regression to the mean. In clinical practice, overminus lenses are typically weaned over an extended period, either by gradually reducing the overminus lens power5,6 (eg, 0.50-D steps)6 or wear time,24 given satisfactory control with the reduced overminus lens power in a clinical examination. In the present study, a 50% reduction in overminus lens power was prescribed for only 3 months, after which the lenses were discontinued regardless of exotropia control. In contrast to a more gradual and dynamic weaning procedure, the present study used a standardized, fixed overminus lens reduction of short duration that did not require numerous control assessments to improve feasibility for a multicenter clinical trial. A different weaning method may have facilitated retention of the treatment effect observed at 12 months.

Previous retrospective studies5,25,26,27 that evaluated refractive error changes with overminus spectacles concluded that overminus spectacle therapy was associated with no more myopic shift than what would normally be expected for the age group being treated. In the present study, we found a greater myopic shift associated with overminus lens treatment, particularly in children with myopia already present at baseline. The treatment group difference in myopic change found in the present study supports the suggestion that the overminus lens treatment was causative. The increased risk of myopic shift should be weighed against the potential benefits of overminus spectacles when discussing this treatment with parents.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Although the 12-month follow-up completion rate was 93%, 3 times as many participants were lost to follow-up in the nonoverminus (21 [11%]) vs the overminus group (7 [4%]). This differential loss to follow-up was accounted for in the primary analysis by imputing missing 12-month data separately for each treatment group. Only 292 of 331 participants (88%) with 18-month data had completed the full treatment and weaning protocol; however, a sensitivity analysis limited to these participants yielded similar results. Another limitation is that refractive error was assessed with cycloplegic retinoscopy by an unmasked examiner, and cycloplegic autorefraction data were available for only 33% of participants. At present, it is unknown whether the myopic shift is permanent or temporary. We are collecting data on change in refractive error and axial length at 24 and 36 months in the extension phase of the present study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, after 12 months of overminus lens wear, children 3 to 10 years of age showed improved distance IXT control when assessed with their overminus spectacles; however, the treatment was associated with an increased risk of myopic shift. Because the beneficial treatment effect did not persist after the participants were weaned off overminus spectacles for 3 months and examined 3 months later, the utility of using our overminus lens treatment protocol as a primary therapy for IXT may be limited. When considering overminus lenses as a potential treatment to temporarily improve IXT control, clinicians and parents should weigh the potential benefit of better eye alignment against the increased risk of myopic shift, particularly in children who already have myopia.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Exotropia Control Assessment Procedure

eTable 2. Definition of Deterioration by a Given Time Point

eTable 3. Clinical Characteristics According to Study Completion

eTable 4. Spectacle Adherence by Treatment Group

eTable 5. Child Assessment of IXT Symptoms Over Time

eTable 6. Parental Assessment of Spectacle Symptoms and Issues Over Time

eTable 7. IXT-Related Quality of Life at 12 and 18 Months

eFigure 1. Average Distance Exotropia Control by Visit

eFigure 2. Distance Exotropia Control According to Baseline Characteristic Subgroups

eAppendix. Statistical Analysis Plan

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

Footnotes

Abbreviations: D, diopters; ∆, prism diopters.

References

- 1.Hatt SR, Gnanaraj L. Interventions for intermittent exotropia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD003737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romano PE, Wilson MF. Survey of current management of intermittent exotropia in the USA and Canada. In: Campos EC, ed. Strabismus and Ocular Motility Disorders. Macmillan Press; 1990:391-396. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-11188-6_55 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donaldson PJ, Kemp EG. An initial study of the treatment of intermittent exotropia by minus overcorrection. Br Orthopt J. 1991;48:41-43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynolds JD, Wackerhagen M, Olitsky SE. Overminus lens therapy for intermittent exotropia. Am Orthopt J. 1994;44:86-91. doi: 10.1080/0065955X.1994.11982018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caltrider N, Jampolsky A. Overcorrecting minus lens therapy for treatment of intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 1983;90(10):1160-1165. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(83)34412-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowe FJ, Noonan CP, Freeman G, DeBell J. Intervention for intermittent distance exotropia with overcorrecting minus lenses. Eye (Lond). 2009;23(2):320-325. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6703057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodacre H. Minus overcorrection: conservative treatment of intermittent exotropia in the young child—a comparative study. Aust Orthopt J. 1985;22:9-17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy JR. The correction of divergent strabisums with concave lenses. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom. 1954;31(12):605-614. doi: 10.1097/00006324-195412000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watts P, Tippings E, Al-Madfai H. Intermittent exotropia, overcorrecting minus lenses, and the Newcastle scoring system. J AAPOS. 2005;9(5):460-464. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayramlar H, Gurturk AY, Sari U, Karadag R. Overcorrecting minus lens therapy in patients with intermittent exotropia: should it be the first therapeutic choice? Int Ophthalmol. 2017;37(2):385-390. doi: 10.1007/s10792-016-0273-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen AM, Holmes JM, Chandler DL, et al. ; Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group . A randomized trial evaluating short-term effectiveness of overminus lenses in children 3 to 6 years of age with intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(10):2127-2136. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.06.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A randomized clinical trial of overminus spectacle therapy for intermittent exotropia. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02807350. Updated December 10, 2020. Accessed September 11, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02807350

- 14.Mohney BG, Holmes JM. An office-based scale for assessing control in intermittent exotropia. Strabismus. 2006;14(3):147-150. doi: 10.1080/09273970600894716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatt SR, Liebermann L, Leske DA, Mohney BG, Holmes JM. Improved assessment of control in intermittent exotropia using multiple measures. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(5):872-876. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatt SR, Mohney BG, Leske DA, Holmes JM. Variability of control in intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2):371-376. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Liebermann L, Holmes JM. Quantifying variability in the measurement of control in intermittent exotropia. J AAPOS. 2015;19(1):33-37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2014.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Liebermann L, Holmes JM. Symptoms in children with intermittent exotropia and their impact on health-related quality of life. Strabismus. 2016;24(4):139-145. doi: 10.1080/09273972.2016.1242640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Yamada T, Bradley EA, Cole SR, Holmes JM. Development and initial validation of quality-of-life questionnaires for intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(1):163-168.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leske DA, Holmes JM, Melia BM; Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group . Evaluation of the Intermittent Exotropia Questionnaire using Rasch analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(4):461-465. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.5622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Little RJA, Rubin DB. The model-based approach to nonresponse: multiple imputation. In: Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. 1st ed. Wiley; 1987:255-259. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrington CP, Manning G. Test statistics and sample size formulae for comparative binomial trials with null hypothesis of non-zero risk difference or non-unity relative risk. Stat Med. 1990;9(12):1447-1454. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780091208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 1995;57(1):289-300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iacobucci IL, Martonyi EJ, Giles CL. Results of overminus lens therapy on postoperative exodeviations. J Ophthalmic Nurs Technol. 1987;6(1):19-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Paula JS, Ibrahim FM, Martins MC, Bicas HE, Velasco e Cruz AA. Refractive error changes in children with intermittent exotropia under overminus lens therapy. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2009;72(6):751-754. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27492009000600002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutstein RP, Marsh-Tootle W, London R. Changes in refractive error for exotropes treated with overminus lenses. Optom Vis Sci. 1989;66(8):487-491. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198908000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kushner BJ. Does overcorrecting minus lens therapy for intermittent exotropia cause myopia? Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(5):638-642. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.5.638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Exotropia Control Assessment Procedure

eTable 2. Definition of Deterioration by a Given Time Point

eTable 3. Clinical Characteristics According to Study Completion

eTable 4. Spectacle Adherence by Treatment Group

eTable 5. Child Assessment of IXT Symptoms Over Time

eTable 6. Parental Assessment of Spectacle Symptoms and Issues Over Time

eTable 7. IXT-Related Quality of Life at 12 and 18 Months

eFigure 1. Average Distance Exotropia Control by Visit

eFigure 2. Distance Exotropia Control According to Baseline Characteristic Subgroups

eAppendix. Statistical Analysis Plan

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement