Key Points

Question

What is the effect of ivermectin on duration of symptoms in adults with mild COVID-19?

Findings

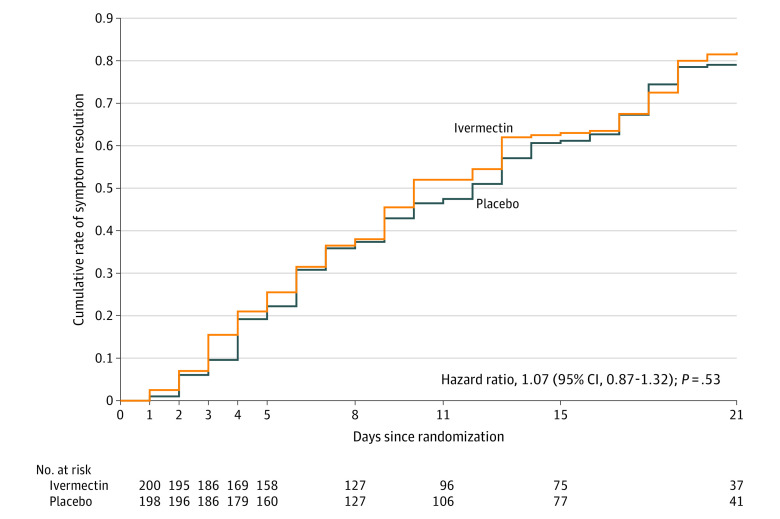

In this randomized clinical trial that included 476 patients, the duration of symptoms was not significantly different for patients who received a 5-day course of ivermectin compared with placebo (median time to resolution of symptoms, 10 vs 12 days; hazard ratio for resolution of symptoms, 1.07).

Meaning

The findings do not support the use of ivermectin for treatment of mild COVID-19, although larger trials may be needed to understand effects on other clinically relevant outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Ivermectin is widely prescribed as a potential treatment for COVID-19 despite uncertainty about its clinical benefit.

Objective

To determine whether ivermectin is an efficacious treatment for mild COVID-19.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Double-blind, randomized trial conducted at a single site in Cali, Colombia. Potential study participants were identified by simple random sampling from the state’s health department electronic database of patients with symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 during the study period. A total of 476 adult patients with mild disease and symptoms for 7 days or fewer (at home or hospitalized) were enrolled between July 15 and November 30, 2020, and followed up through December 21, 2020.

Intervention

Patients were randomized to receive ivermectin, 300 μg/kg of body weight per day for 5 days (n = 200) or placebo (n = 200).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome was time to resolution of symptoms within a 21-day follow-up period. Solicited adverse events and serious adverse events were also collected.

Results

Among 400 patients who were randomized in the primary analysis population (median age, 37 years [interquartile range {IQR}, 29-48]; 231 women [58%]), 398 (99.5%) completed the trial. The median time to resolution of symptoms was 10 days (IQR, 9-13) in the ivermectin group compared with 12 days (IQR, 9-13) in the placebo group (hazard ratio for resolution of symptoms, 1.07 [95% CI, 0.87 to 1.32]; P = .53 by log-rank test). By day 21, 82% in the ivermectin group and 79% in the placebo group had resolved symptoms. The most common solicited adverse event was headache, reported by 104 patients (52%) given ivermectin and 111 (56%) who received placebo. The most common serious adverse event was multiorgan failure, occurring in 4 patients (2 in each group).

Conclusion and Relevance

Among adults with mild COVID-19, a 5-day course of ivermectin, compared with placebo, did not significantly improve the time to resolution of symptoms. The findings do not support the use of ivermectin for treatment of mild COVID-19, although larger trials may be needed to understand the effects of ivermectin on other clinically relevant outcomes.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04405843

This randomized trial compares the effects of ivermectin vs placebo on time to symptom resolution within 21 days among patients with mild COVID-19.

Introduction

Therapeutic approaches are needed to improve outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Ivermectin, a widely used drug with a favorable safety profile,1 is thought to act at different protein-binding sites to reduce viral replication.2,3,4,5 Because of evidence of activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro6 and in animal models,7,8 ivermectin has attracted interest in the global scientific community9 and among policy makers.10 Several countries have included ivermectin in their treatment guidelines,11,12,13 leading to a surge in the demand for the medication by the general population and even alleged distribution of veterinary formulations.14 However, clinical trials are needed to determine the effects of ivermectin on COVID-19 in the clinical setting.

Viral replication may be particularly active early in the course of COVID-1915 and experimental studies have shown antiviral activity of ivermectin in early stages of other infections.4 The hypothesis of this randomized trial (EPIC trial [Estudio Para Evaluar la Ivermectina en COVID-19]) was that ivermectin would accelerate recovery in patients with COVID-19 when administered during the first days of infection.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

This study was approved by the Colombian Regulatory Agency (INVIMA No. PI-CEP-1390), the independent ethics committees of Corporación Científica Pediátrica, and collaborating hospitals in Cali, Colombia, and conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Full details of the trial can be found in the protocol (Supplement 1).

This double-blind, randomized trial of ivermectin vs placebo was conducted from July 15 to December 21, 2020, by Centro de Estudios en Infectología Pediátrica in Cali. Study candidates were identified from the state’s health department electronic database of all patients with a positive result from a SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction or antigen test performed in any of the Colombian National Institute of Health–authorized laboratories in the city of Cali.

Potential study participants were identified and selected by simple random sampling from the state’s database. Adult men and non–pregnant or breast-feeding women were eligible if their symptoms began within the previous 7 days and they had mild disease, defined as being at home or hospitalized but not receiving high-flow nasal oxygen or mechanical ventilation (invasive or noninvasive). Patients were excluded if they were asymptomatic, had severe pneumonia, had received ivermectin within the previous 5 days, or had hepatic dysfunction or liver function test results more than 1.5 times the normal level. Details of selection criteria can be found in the protocol (Supplement 1). Health disparities by race/ethnicity have been reported in COVID-19 infections.16,17 Hence, information on this variable was collected by study personnel based on fixed categories as selected by the study participants.

Randomization

Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either oral ivermectin or placebo in solution for 5 days. Patients were randomized in permuted blocks of 4 in a randomization sequence prepared by the unblinded pharmacist in Microsoft Excel version 19.0 who provided masked ivermectin or placebo to a field nurse for home or hospital patient visits. Allocation assignment was concealed from investigators and patients.

Interventions

Study patients received 300 μg/kg of body weight per day of oral ivermectin in solution or the same volume of placebo for 5 days. Ivermectin was provided by Tecnoquímicas SA in bottles of 0.6% solution for oral administration. Patients were asked to take the investigational product on an empty stomach, except on the first study day, when it was administered after screening and randomization procedures took place.

Up to August 26, 2020, the placebo was a mixture of 5% dextrose in saline and 5% dextrose in distilled water, after which placebo was a solution with similar organoleptic properties to ivermectin provided by the manufacturer. Because blinding could be jeopardized due to the different taste and smell of ivermectin and the saline/dextrose placebo, only 1 patient per household was included in the study until the manufacturer’s placebo was available. Bottles of ivermectin and placebo were identical throughout the study period to guarantee double-blinding.

Procedures

A study physician contacted potential study participants by telephone to verify selection criteria for eligibility and obtain informed consent. Patients were then visited at home or in hospital by a study nurse who drew blood for liver enzyme evaluations and performed a urine pregnancy test. Eligible patients were revisited by a study nurse for enrollment, documentation of baseline demographic and clinical information, and dispensing of the investigational product. Investigational product was left with the patient for self-administration on days 2 through 5. Subsequently, patients were contacted by telephone by study staff on days 2 through 5, 8, 11, 15, and 21 for a structured interview. A study physician reviewed medical records of hospitalized patients to obtain the information required by the protocol. After study end (day 21), unused or empty investigational product bottles were collected to certify adherence. Data were entered into an electronic database and validated by the site’s quality management department.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was the time from randomization to complete resolution of symptoms within the 21-day follow-up period. The 8-category ordinal scale used in this trial has been used in different COVID-19 therapeutic trials18,19,20 and is recommended by the World Health Organization’s R&D Blueprint.21 It consists of the following categories: 0 = no clinical evidence of infection; 1 = not hospitalized and no limitation of activities; 2 = not hospitalized, with limitation of activities, home oxygen requirement, or both; 3 = hospitalized, not requiring supplemental oxygen; 4 = hospitalized, requiring supplemental oxygen; 5 = hospitalized, requiring nasal high-flow oxygen, noninvasive mechanical ventilation, or both; 6 = hospitalized, requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or both; and 7 = death. Time to recovery was defined as the first day during the 21 days of follow-up in which the patient reported a score of 0.

Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients with clinical deterioration, defined as those with worsening by 2 points (from the baseline score on the 8-category ordinal scale) since randomization. Additional secondary outcomes were the clinical conditions as assessed by the 8-category ordinal scale on days 2, 5, 8, 11, 15, and 21; however, data for days 2 and 15 are not reported here. The proportion of patients who developed fever and the duration of fever since randomization and the proportion of patients who died were also reported. Proportions of patients with new-onset hospitalization in the general ward or intensive care unit or new-onset supplementary oxygen requirement for more than 24 hours were combined into a single outcome called escalation of care. Frequency of incident cases of escalation of care, as well as the duration in both treatment groups, was reported. Evaluation of adverse events (AEs) included solicited AEs, AEs leading to treatment discontinuation, and serious AEs. AEs were classified according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0.22

Post Hoc Analysis

Given that some patients’ need for escalation of care was imminent when randomized, the frequency of incident cases of escalation of care occurring 12 or more hours after randomization and the duration up to day 21 in both treatment groups were reported. A comparison of the proportions of patients who required emergency department (ED) or telemedicine consultation was also performed.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was originally defined as the time from randomization until worsening by 2 points on the 8-category ordinal scale. According to the literature, approximately 18% of patients were expected to have such an outcome.23 However, before the interim analysis, it became apparent that the pooled event rate of worsening by 2 points was substantially lower than the initial 18% expectation, requiring an unattainable sample size. Therefore, on August 31, 2020, the principal investigator proposed to the data and safety monitoring board to modify the primary end point to time from randomization to complete resolution of symptoms within the 21-day follow-up period. This was approved on September 2, 2020. The original sample size of 400 based on the log-rank test for the new primary end point was kept, using an ivermectin to placebo assignment ratio of 1:1. This would allow the detection of 290 events of interest (symptom resolution), assuming that 75% of patients would have the outcome of interest at 21 days,24 with a 2% dropout rate. This would provide an 80% power under a 2-sided type I error of 5% if the hazard ratio (HR) comparing ivermectin vs placebo is 1.4, corresponding to a 3-day faster resolution of symptoms in patients receiving ivermectin, assuming that time to resolution of symptoms is 12 days with placebo.24 With an HR of 1.4, 75% and 85% of patients in the placebo and ivermectin groups, respectively, would experience the outcome of interest at 21 days.

On October 20, 2020, the lead pharmacist observed that a labeling error had occurred between September 29 and October 15, 2020, resulting in all patients receiving ivermectin and none receiving placebo during this time frame. The study blind was not unmasked due to this error. The data and safety monitoring board recommended excluding these patients from the primary analysis but retaining them for sensitivity analysis. The protocol was amended to replace these patients to retain the originally calculated study power. The primary analysis population included patients who were analyzed according to their randomization group, but excluded patients recruited between September 29 and October 15, 2020, as well as patients who were randomized but later found to be in violation of selection criteria. Patients were analyzed according to the treatment they received in the as-treated population (sensitivity analysis).

The primary end point of time from randomization to complete resolution of symptoms with ivermectin vs placebo was assessed by a Kaplan-Meier plot and compared with a log-rank test. The HRs and 95% CIs for the cumulative incidence of symptom resolution in both treatment groups were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model. The proportional hazards assumption was tested graphically using a log-log plot and the test of the nonzero slope. There was no evidence to reject the proportionality assumption.

The time to complete resolution of symptoms was assessed after all patients reached day 21. Data for patients who died or lacked symptom resolution before day 21 were right-censored at death or day 21, respectively. Evaluation of the effect of the treatment in each study visit using the 8-point ordinal scale was estimated using the proportional odds ratio (OR) with its respective 95% CI with an ordinal logistic regression. The proportional odds assumption was met according to the Brant test. The 8-point ordinal scale was inverted in its score, where 0 corresponded to death and 7 to a patient without symptoms.

For sensitivity analysis, primary and secondary end points were compared in the as-treated population.

Clustered standard errors were estimated to adjust for the correlation between multiple patients from the same household. Statistical significance was set at P < .05, and all tests were 2-tailed. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. Statistical analyses were done with Stata version 16.0 (StataCorp). Bootstrapping 95% CIs for differences of medians were calculated with R statistical package version 3.6.3 (The R Foundation).

Results

Patients

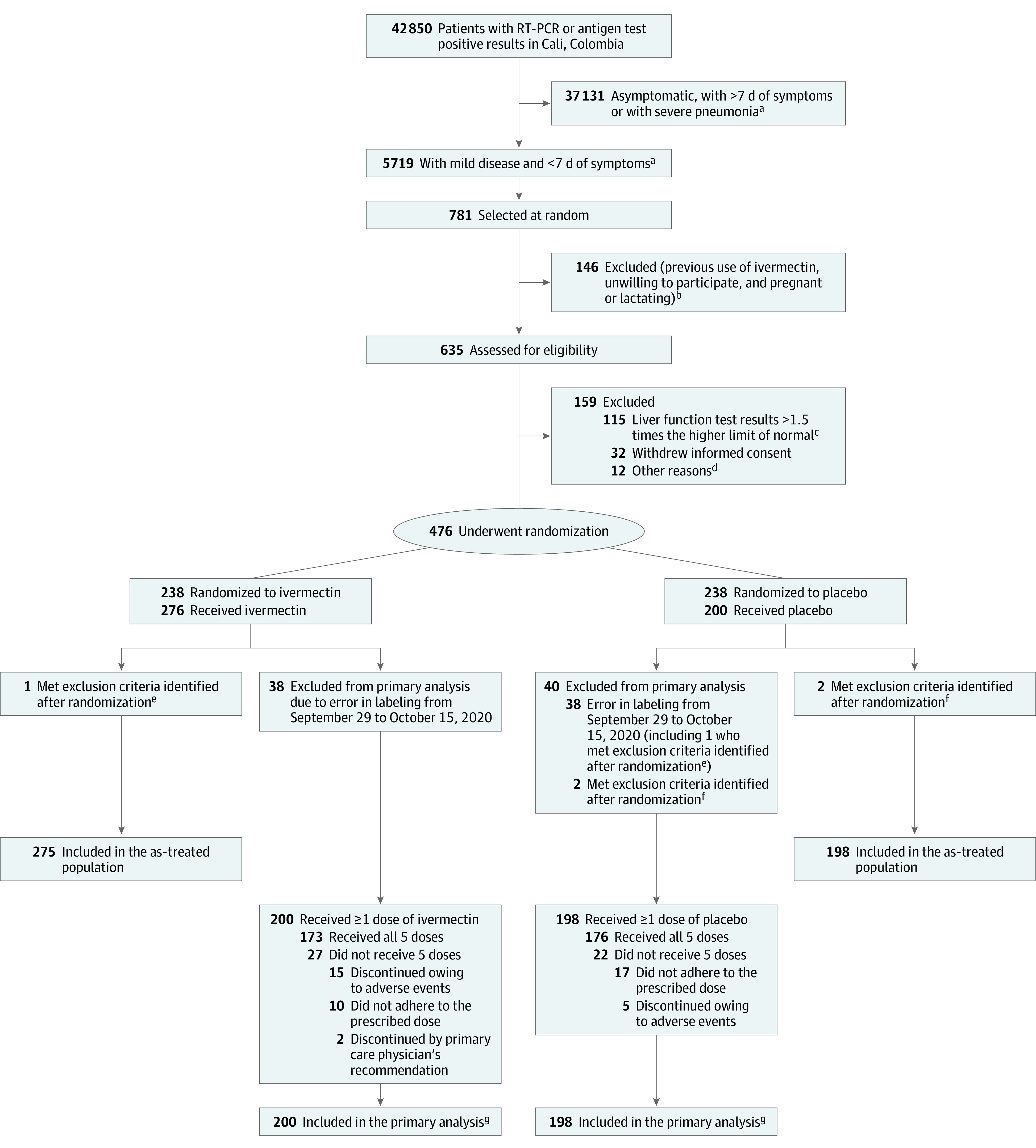

Of the 476 patients who underwent randomization, 238 were assigned to receive ivermectin and 238 to receive placebo (Figure 1). Seventy-five patients were randomized between September 29 and October 15, 2020, and were excluded from the primary analysis population but remained in the as-treated population. Three patients were excluded from all analyses because they were identified as ineligible after randomization (1 asymptomatic patient and 2 who received ivermectin within 5 days prior to enrollment). The primary analysis population included 398 patients (200 allocated to ivermectin and 198 to placebo).

Figure 1. Enrollment, Randomization, and Treatment Assignment.

RT-PCR indicates reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction.

aPatients with mild disease were at home or hospitalized but not receiving high-flow nasal oxygen or mechanical ventilation (invasive or noninvasive). Patients with severe pneumonia were receiving high-flow nasal oxygen, mechanical ventilation (invasive or noninvasive), or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

bThe numbers of patients with these exclusion criteria were not collected.

cAspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase.

dEight patients used ivermectin within 5 days prior to randomization, 1 had a positive pregnancy test, 1 was asymptomatic, 1 lived in an inaccessible area, and 1 had onset of symptoms 8 days prior to randomization.

ePatient was asymptomatic and was randomized to receive placebo but received ivermectin.

fUse of ivermectin before randomization.

gIncludes deaths and recoveries.

Patients in both groups were balanced in demographic and disease characteristics at baseline (Table 1; eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The median age of patients in the primary analysis population was 37 years (interquartile range [IQR], 29-48), 231 (58%) were women, and 316 (79%) did not have any known comorbidities at baseline. At randomization, the median National Early Warning Score 2 was 3 (IQR, 2-4) and most patients (n = 232, 58.3%) were at home and able to perform their routine activities. The most common symptoms were myalgia (310 patients, 77.9%) and headache (305 patients, 76.6%), followed by smell and taste disturbances (223 [56%] and 199 [50%], respectively) and cough (211 patients, 53%), which was most commonly dry (181 patients, 45.5%) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline and Medications Initiated Since Symptom Onset in the Primary Analysis Population.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ivermectin (n = 200) | Placebo (n = 198) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 37 (29-47.7) | 37 (28.7-49.2) |

| Age groups, y | ||

| <40 | 119 (59.5) | 112 (56.6) |

| 40-64 | 73 (36.5) | 70 (35.3) |

| ≥65 | 8 (4.0) | 16 (8.1) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 78 (39) | 89 (44.9) |

| Female | 122 (61) | 109 (55) |

| Race or ethnic groupa | ||

| Mixed race | 178 (89) | 179 (90.4) |

| Black or African American | 16 (8.0) | 16 (8.1) |

| Colombian native | 6 (3.0) | 3 (1.5) |

| Health insurance | ||

| Private/semiprivate | 177 (88.5) | 174 (87.9) |

| Government subsidized | 20 (10.0) | 23 (11.6) |

| Uninsured | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| No. of persons in the same household, median (IQR) | 4 (3-5) | 3 (3-4) |

| Current smoker | 3 (1.5) | 8 (4.0) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 26.1 (23.1-28.8) | 26.4 (22.7-29.0) |

| History of BCG vaccination, No./No. with available information (%) | 183/199 (92.0) | 184/195 (90.4) |

| Coexisting conditionsb | ||

| Obesity (BMI ≥30), No./No. with available information (%) | 37/200 (18.5) | 38/196 (19.4) |

| Hypertension | 28 (14.0) | 25 (12.6) |

| Diabetes | 10 (5.0) | 12 (6.1) |

| Thyroid disease | 7 (3.5) | 8 (4.0) |

| Respiratory disease | 6 (3.0) | 6 (3.0) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 4 (2.0) | 3 (1.5) |

| Any coexisting condition | 44 (22.0) | 38 (19.2) |

| Median time (IQR) from symptom onset to randomization, d | 5 (4-6) | 5 (4-6) |

| NEWS2 score at randomization, median (IQR)c | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) |

| Score on ordinal scale at randomization | ||

| 1: Not hospitalized and no limitation of activities | 123 (61.5) | 109 (55.0) |

| 2: Not hospitalized, with limitation of activities, home oxygen requirement, or both | 75 (37.5) | 87 (43.9) |

| 3: Hospitalized, not requiring supplemental oxygen | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| 4: Hospitalized, requiring supplemental oxygend | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Medications initiated since symptom onset | ||

| NSAIDs | 57 (28.5) | 61 (30.8) |

| Othere | 41 (20.5) | 38 (19.2) |

| Macrolides | 27 (13.5) | 22 (11.1) |

| Other antipyretics | 26 (13.0) | 23 (11.6) |

| Nonmacrolide antibiotics | 13 (6.5) | 11 (5.6) |

| Glucocorticoids | 6 (3.0) | 12 (6.1) |

| Other immunomodulating agentsf | 4 (2.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Anticoagulants | 1 (0.5) | 7 (3.5) |

Abbreviations: BCG, Bacille Calmette-Guérin; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); IQR, interquartile range; NEWS2, National Early Warning Score 2; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Race/ethnic group was collected by study personnel based on fixed categories as selected by the study participants. “Mixed race” refers to an individual of mixed European/Colombian native heritage.

Coexisting conditions were determined by self-report.

NEWS2 includes 6 physiological measures; total scores range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating greater clinical risk. Score of 3 indicates low clinical risk.

Not high-flow nasal oxygen nor mechanical ventilation.

Acyclovir, antidiarrheals, antiemetics, antihistamines, antiparasitics, antispasmodics, antitussives, natural or homeopathic medications, proton pump inhibitors, and salbutamol.

Oral interferon and colchicine.

Baseline characteristics of the 75 patients who received ivermectin but were excluded from the primary analysis were not significantly different from the 398 remaining patients in the cohort (eTables 1 and 3 in Supplement 2).

Primary Outcome

Time to resolution of symptoms in patients assigned to ivermectin vs placebo was not significantly different (median, 10 days vs 12 days; difference, −2 days [IQR, −4 to 2]; HR for resolution of symptoms, 1.07 [95% CI, 0.87 to 1.32]; P = .53) (Figure 2 and Table 2). In the ivermectin and placebo groups, symptoms resolved in 82% and 79% of patients, respectively, by day 21 (Table 2).

Figure 2. Time to Resolution of Symptoms in the Primary Analysis Population.

The cumulative rate of symptom resolution is the percentage of patients who experienced their first day free of symptoms. All patients were followed up for 21 days.

Table 2. Outcomes in the Primary Analysis Population.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Absolute difference (95% CI) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ivermectin (n = 200) | Placebo (n = 198) | ||||

| Primary outcome: resolution of symptomsa | |||||

| Time to resolution of symptoms, median No. of days (IQR) | 10 (9-13) | 12 (9-13) | −2 (−4 to 2)b | 1.07 (0.87 to 1.32)c | .53 |

| Symptoms resolved at 21 d | 164 (82.0) | 156 (79.0) | 3.21 (−4.58 to 11.01)d | 1.23 (0.75 to 2.01)e | |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Deterioration by ≥2 points in an ordinal 8-point scalef | 4 (2.0) | 7 (3.5) | −1.53 (−4.75 to 1.69)d | 0.56 (0.16 to 1.93)e | |

| Fever since randomizationg | 16 (8.0) | 21 (10.6) | −2.61 (−8.31 to 3.09)d | 0.73 (0.37 to 1.45)e | |

| Duration of febrile episode, median (IQR), d | 1.5 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | −0.5 (−1.0 to 2.0)b | ||

| Escalation of care since randomizationh | 4 (2.0) | 10 (5.0) | −3.05 (−6.67 to 0.56)d | 0.38 (0.12 to 1.24)e | |

| Duration, median (IQR) di | 13 (3.5-21) | 6 (3.7-10.7) | 7 (−5 to 16.5)b | ||

| Deaths | 0 | 1 (0.5) | |||

| Post hoc outcomes | |||||

| Escalation of care occurring ≥12 h since randomizationh | 4 (2.0) | 6 (3.0) | −1.0 (−4.11 to 2.05)d | 0.65 (0.18 to 2.36)e | |

| Duration, median (IQR), di | 13 (3.5-21) | 8 (4.2-13.2) | 5 (−8.5 to 16)b | ||

| Emergency department visits or telemedicine consultations, No. of patients | 16 (8.0) | 13 (6.6) | 1.43 (−3.67 to 6.54)d | 1.24 (0.56 to 2.74)e | |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Resolution of symptoms was defined as the first day free of symptoms.

Absolute difference is the median difference with 95% CIs estimated by bootstrap sampling.

Hazard ratio for resolution of symptoms was estimated by the Cox proportional-hazard model. The P value for this ratio was calculated with the log-rank test.

Absolute difference is the difference in proportions.

Effect estimate is odds ratio (2-sided 95% CI) from a logistic model.

Ordinal scale: 0 = no clinical evidence of infection; 1 = not hospitalized and no limitation of activities; 2 = not hospitalized, with limitation of activities, home oxygen requirement, or both; 3 = hospitalized, not requiring supplemental oxygen; 4 = hospitalized, requiring supplemental oxygen; 5 = hospitalized, requiring nasal high-flow oxygen, noninvasive mechanical ventilation, or both; 6 = hospitalized, requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or both; and 7 = death.

Fever defined as an axillary temperature ≥38 °C. Patients took their own temperatures while at home.

Escalation of care defined as new-onset hospitalization in the general ward or intensive care unit or new-onset supplementary oxygen requirement for more than 24 hours.

Number of days that patients required hospitalization or supplementary oxygen. If both were required, the longer duration was recorded.

The type of placebo that patients received did not affect the results (HR for ivermectin vs dextrose in saline: 1.14 [95% CI, 0.83-1.55]; HR for ivermectin vs manufacturer’s placebo: 1.07 [95% CI, 0.85 to 1.34] (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2).

Similar results were observed in the as-treated population (eFigure 2 and eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Secondary Outcomes

Few patients had clinical deterioration of 2 or more points in the ordinal 8-point scale, and there was no significant difference between the 2 treatment groups (2% in the ivermectin group and 3.5% in the placebo group; absolute difference, −1.53 [95% CI, −4.75 to 1.69]). The OR for deterioration in ivermectin vs placebo groups was 0.56 (95% CI, 0.16 to 1.93) (Table 2).

The odds of improving the score in the ordinal scale were not significantly different between both treatment groups, as determined by proportional odds models (eFigure 3 and eTable 5 in Supplement 2).

There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients who required escalation of care in the 2 treatment groups (2% with ivermectin, 5% with placebo; absolute difference, −3.05 [95% CI, −6.67 to 0.56]; OR, 0.38 [95% CI, 0.12 to 1.24]). The length of time during which patients required escalation of care in the ivermectin vs placebo groups was not significantly different (median difference, 7 days [IQR, −5.0 to 16.5]). The proportions of patients who developed fever during the study period were not significantly different between the 2 treatment groups (absolute difference of ivermectin vs placebo, −2.61 [95% CI, −8.31 to 3.09]; OR, 0.73 [95% CI, 0.37 to 1.45]), nor was the duration of fever (absolute difference of ivermectin vs placebo, −0.5 days [95% CI, −1.0 to 2.0]) (Table 2). One patient in the placebo group died during the study period. No data were missing for the primary or secondary outcomes. See eTables 4 and 6 in Supplement 2 for the results in the as-treated population.

Post Hoc End Points and Analyses

After excluding 4 patients who required hospitalization within 12 hours after randomization (median, 3.25 hours [IQR, 2-6]), there were 4 patients (2%) in the ivermectin group and 6 (3%) in the placebo group who required escalation of care (absolute difference, −1.0 [95% CI, −4.11 to 2.05]; OR, 0.65 [95% CI, 0.18 to 2.36]) (Table 2).

The proportions of patients who sought medical care (ED or telemedicine consultation) were not significantly different between the 2 treatment groups (8.0% in the ivermectin group and 6.6% in the placebo group; absolute difference, 1.43 [95% CI, −3.67 to 6.54]; OR, 1.24 [95% CI, 0.56 to 2.74]) (Table 2). See eTable 4 in Supplement 2 for the results in the as-treated population.

Adverse Events

A total of 154 patients (77%) in the ivermectin group and 161 (81.3%) in the placebo group reported AEs between randomization and day 21. Fifteen patients (7.5%) in the ivermectin group vs 5 patients (2.5%) in the placebo group discontinued treatment due to an AE. Serious AEs developed in 4 patients, 2 in each group, but none were considered by the investigators to be related to the trial medication (Table 3; eTable 7 in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Summary of Adverse Events During the 21-Day Follow-up Period in the Primary Analysis Population.

| Event | Any grade, No. (%)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Ivermectin (n = 200) | Placebo (n = 198) | |

| Solicited adverse eventsb | ||

| Headache | 104 (52.0) | 111 (56.1) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 2 (1-5) | 2 (1-5) |

| Dizziness | 68 (34.0) | 68 (34.3) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 1.5 (1-3) | 2 (1-3.7) |

| Diarrhea | 52 (26.0) | 65 (32.8) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) |

| Nausea | 46 (23) | 47 (23.7) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 1 (1-3.5) | 2 (1-4) |

| Abdominal pain | 36 (18.0) | 49 (24.7) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) |

| Disturbances of vision | 33 (16.5) | 28 (14.4) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-4.7) |

| Photophobia | 7 (3.5) | 4 (2.0) |

| Blurry vision | 23 (11.5) | 23 (11.6) |

| Reduction in visual acuity | 4 (2.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Tremor | 13 (6.5) | 6 (3.0) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 1 (1-6.5) | 3.5 (1-6.5) |

| Skin discoloration | 13 (6.5) | 4 (2.0) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 3 (1.2-5.2) | 4 (2.5-13) |

| Skin rash | 12 (6.0) | 19 (9.6) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 4.5 (3-7) | 4 (1-8) |

| Swelling | 4 (2.0) | 3 (1.5) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 3 (1.2-4.7) | 1 (1-1) |

| Vomiting | 3 (1.5) | 6 (3.0) |

| Duration, median (IQR), d | 1 (1-3) | 1 (1-1.5) |

| No. of patients with ≥1 solicited adverse events | 154 (77.0) | 161 (81.3) |

| Adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation | 15 (7.5) | 5 (2.5) |

| Serious adverse eventsc | ||

| Respiratory failure | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Acute kidney injury | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Multiorgan failure | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 2 (1.0) | 0 |

| Sepsis | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| No. of patients with ≥1 serious adverse events | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Grade refers to the severity of the adverse event, determined according to the following: Grade 1, mild: asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated. Grade 2, moderate: minimal, local, or noninvasive intervention indicated; limiting age-appropriate instrumental activities of daily living (ADL). Grade 3, severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening: hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization indicated; disabling; limiting self-care ADL. Grade 4, life-threatening consequences: urgent intervention indicated. Grade 5, death related to adverse events. Grade 3 solicited adverse events: headache, n = 1 in the placebo group, duration of 6 days; dizziness, n = 1 in the ivermectin group, duration of 6 days and n = 3 in the placebo group (median duration of 2 days [IQR, 1-8]); and skin rash, n = 2 in the ivermectin group (median duration of 8 days [IQR, 7-9]). No grade 4 events occurred.

Adverse events were solicited by telephone at each follow-up call.

Serious adverse events were severe, medically significant, or life-threatening conditions occurring in study patients documented from revision of patients’ electronic medical records. All were grade 3 or 4, except 1 patient in the placebo group who had grade 5 respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, multiorgan failure, and sepsis.

Discussion

In this double-blind, randomized trial of symptomatic adults with mild COVID-19, a 5-day course of ivermectin vs placebo initiated in the first 7 days after evidence of infection failed to significantly improve the time to resolution of symptoms.

Interest in ivermectin in COVID-19 therapy began from an in vitro study that found that bathing SARS-CoV-2–infected Vero-hSLAM cells with 5-μM ivermectin led to an approximately 5000-fold reduction in viral RNA.8 However, pharmacokinetic models indicated that the concentrations used in the in vitro study are difficult to achieve in human lungs or plasma,25 and inhibitory concentrations of ivermectin are unlikely to be achieved in humans at clinically safe doses.26 Despite this, a retrospective study using logistic regression and propensity score matching found an association between 200 μg/kg of ivermectin in a single dose (8% of patients received a second dose) and improved survival for patients admitted with severe COVID-19.27 The contrast with the findings in this trial may be related to differences in patient characteristics, exposures and outcomes that were measured, or unmeasured confounders in the observational study. To our knowledge, preliminary reports of other randomized trials of ivermectin as treatment for COVID-19 with positive results have not yet been published in peer-reviewed journals.28,29,30,31

Daily doses were used in this trial because pharmacokinetic models have shown higher lung concentrations with daily rather than intermittent dosing,32 and have proven to be well tolerated.33,34 In addition, the US Food and Drug Administration–approved dose for the treatment of helminthic diseases (200 μg/kg) showed clinical benefit in an observational study,27 supporting a hypothesis that higher doses could be clinically relevant.

This study did not find any significant effect of ivermectin on other evaluated measures of clinical benefit for the treatment of COVID-19. Although a numerically smaller proportion of ivermectin-treated patients required escalation of care (2.0% with ivermectin vs 5.0% with placebo), the difference was not statistically significant and was further attenuated in a post hoc analysis after excluding 4 patients who were hospitalized at a median time of 3.25 hours after randomization. In addition, ivermectin did not reduce ED or telephone consultations, further supporting the lack of efficacy for these outcomes. However, the relatively young and healthy study population rarely developed complications, rendering the study underpowered to detect such effects. Therefore, the ability of ivermectin to prevent the progression of mild COVID-19 to more severe stages would need to be assessed in larger trials.

The study was sufficiently powered to detect faster resolution of symptoms in patients soon after they became apparent, and no significant difference was identified. However, the study population was relatively young, with few comorbidities and with liver enzyme levels less than 1.5 times the normal level, so the findings may be generalizable only to such populations.

Cumulatively, the findings suggest that ivermectin does not significantly affect the course of early COVID-19, consistent with pharmacokinetic models showing that plasma total and unbound ivermectin levels do not reach the concentration resulting in 50% of viral inhibition even for a dose level 10-times higher than the approved dose.32

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the study was not conducted or completed according to the original design, and the original primary outcome to detect the ability of ivermectin to prevent clinical deterioration was changed 6 weeks into the trial. In the study population, the incidence of clinical deterioration was below 3%, making the original planned analysis futile. Ultimately, findings for primary and secondary end points were not significantly different between the ivermectin and placebo groups.

Second, the study was well-powered to detect an HR for resolution of symptoms of 1.4 in the ivermectin vs placebo groups, but may have been underpowered to detect a smaller but still clinically meaningful reduction in the primary end point.

Third, virological assessments were not included, but the clinical characteristics that were measured indirectly reflect viral activity and are of interest during the pandemic.

Fourth, the placebo used in the first 65 patients differed in taste and smell from ivermectin. However, patients from the same household were not included until the placebo with the same organoleptic properties was available, and the lack of effect of ivermectin on the primary outcome was similar when compared with either formulation of placebo.

Fifth, 2 secondary outcomes used an 8-category ordinal scale that in initial stages requires patient self-reporting and thus allows subjectivity to be introduced. Sixth, data on the ivermectin plasma levels were not collected. Seventh, as already noted, the study population was relatively young and results may differ in an older population.

Conclusions

Among adults with mild COVID-19, a 5-day course of ivermectin, compared with placebo, did not significantly improve the time to resolution of symptoms. The findings do not support the use of ivermectin for treatment of mild COVID-19, although larger trials may be needed to understand the effects of ivermectin on other clinically relevant outcomes.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics – As-Treated Population

eTable 2. Clinical Manifestations of Patients at Baseline – Primary Analysis Population

eTable 3.Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Between the 75 Patients Receiving Ivermectin Who Were Excluded From Primary Analysis due to Error During Product Labeling and the Rest of the Cohort

eTable 4. Outcomes – As-Treated Population

eTable 5. Ordinal Scale Measure by Treatment Group and Study Visit – Primary Analysis Population

eTable 6. Ordinal Scale Measure by Treatment Group and Study Visit – As-Treated Population

eTable 7. Summary of Adverse Events – As-Treated Population

eFigure 1. Time to Resolution of Symptoms – As-Treated Population According to the Type of Placebo

eFigure 2. Time to Resolution of Symptoms – As-Treated Population

eFigure 3. Clinical Status on an 8-Point Ordinal Scale on Study Days 5, 8, 11 and 21 by Treatment Group – Primary Analysis Population

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Omura S. Ivermectin: 25 years and still going strong. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31(2):91-98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang SNY, Atkinson SC, Wang C, et al. The broad spectrum antiviral ivermectin targets the host nuclear transport importin α/β1 heterodimer. Antiviral Res. 2020;177:104760. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagstaff KM, Sivakumaran H, Heaton SM, Harrich D, Jans DA. Ivermectin is a specific inhibitor of importin α/β-mediated nuclear import able to inhibit replication of HIV-1 and dengue virus. Biochem J. 2012;443(3):851-856. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mastrangelo E, Pezzullo M, De Burghgraeve T, et al. Ivermectin is a potent inhibitor of flavivirus replication specifically targeting NS3 helicase activity: new prospects for an old drug. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(8):1884-1894. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tay MY, Fraser JE, Chan WK, et al. Nuclear localization of dengue virus (DENV) 1-4 non-structural protein 5: protection against all 4 DENV serotypes by the inhibitor Ivermectin. Antiviral Res. 2013;99(3):301-306. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frontline Covid-19 Critical Care Alliance. Accessed December 19, 2020. https://covid19criticalcare.com/

- 7.US Senate Committee on Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs . Early outpatient treatment: an essential part of a COVID-19 solution, part II. Accessed December 19, 2020. https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/early-outpatient-treatment-an-essential-part-of-a-covid-19-solution-part-ii

- 8.Caly L, Druce JD, Catton MG, Jans DA, Wagstaff KM. The FDA-approved drug ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2020;178:104787. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Melo GD, Lazarini F, Larrous F, et al. Anti-COVID-19 efficacy of ivermectin in the golden hamster. bioRxiv. Preprint posted November 22, 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.11.21.392639 [DOI]

- 10.Arévalo A, Pagotto R, Pórfido J, et al. Ivermectin reduces coronavirus infection in vivo: a mouse experimental model. bioRxiv. Preprint posted November 2, 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.11.02.363242 [DOI]

- 11.Ministerio de Salud, República del Perú . Resolución ministerial No. 270-2020-MINSA. Accessed December 19, 2020. https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/694719/RM_270-2020-MINSA.PDF

- 12.Rodriguez Mega E. Latin America’s embrace of an unproven COVID treatment is hindering drug trials. Nature. Accessed December 19, 2020. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02958-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno del Estado de Bolivia . Resolución ministerial No. 0259. Accessed December 19, 2020. https://www.minsalud.gob.bo/component/jdownloads/?task=download.send&id=425&catid=27&m=0&Itemid=646

- 14.Molento MB. COVID-19 and the rush for self-medication and self-dosing with ivermectin: a word of caution. One Health. 2020;10:100148. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siddiqi HK, Mehra MR. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical-therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(5):405-407. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahajan UV, Larkins-Pettigrew M. Racial demographics and COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths: a correlational analysis of 2886 US counties. J Public Health (Oxf). 2020;42(3):445-447. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karaca-Mandic P, Georgiou A, Sen S. Assessment of COVID-19 hospitalizations by race/ethnicity in 12 states. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(1):131-134. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1787-1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. ; ACTT-1 Study Group Members . Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19: final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1813-1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spinner CD, Gottlieb RL, Criner GJ, et al. ; GS-US-540-5774 Investigators . Effect of remdesivir vs standard care on clinical status at 11 days in patients with moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1048-1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization . WHO R&D blueprint: novel coronavirus: COVID-19 therapeutic trial synopsis. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/COVID-19_Treatment_Trial_Design_Master_Protocol_synopsis_Final_18022020.pdf

- 22.US Department of Health and Human Services . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Published November 27, 2017. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf

- 23.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitjà O, Corbacho-Monné M, Ubals M, et al. ; BCN PEP-CoV-2 RESEARCH GROUP . Hydroxychloroquine for early treatment of adults with mild COVID-19: a randomized-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bray M, Rayner C, Noël F, Jans D, Wagstaff K. Ivermectin and COVID-19: a report in antiviral research, widespread interest, an FDA warning, two letters to the editor and the authors’ responses. Antiviral Res. 2020;178:104805. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Momekov G, Momekova D. Ivermectin as a potential COVID-19 treatment from the pharmacokinetic point of view: antiviral levels are not likely attainable with known dosing regimens. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equipment. 2020;34:469-74. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2020.1775118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajter JC, Sherman MS, Fatteh N, Vogel F, Sacks J, Rajter JJ. Use of ivermectin is associated with lower mortality in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019: the ICON Study. Chest. Published online October 12, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmed E, Hany B, Abo Youssef S, et al. Efficacy and safety of ivermectin for treatment and prophylaxis of COVID-19 pandemic. Research Square. Preprint posted November 17, 2020. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-100956/v1 [DOI]

- 29.Hashim HA, Maulood MF, Rasheed AM, Fatak DF, Kabah KK, Abdulamir AS. Controlled randomized clinical trial on using ivermectin with doxycycline for treating COVID-19 patients in Baghdad, Iraq. medRxiv. Preprint posted October 27, 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.26.20219345 [DOI]

- 30.Niaee MS, Gheibi N, Namdar P, et al. Ivermectin as an adjunct treatment for hospitalized adult COVID-19 patients: a randomized multi-center clinical trial. Research Square. Preprint posted November 24, 2020. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-109670/v1 [DOI]

- 31.Clinical Trial of Ivermectin Plus Doxycycline for the Treatment of Confirmed Covid-19 Infection. Accessed December 21, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT04523831

- 32.Schmith VD, Zhou JJ, Lohmer LRL. The approved dose of ivermectin alone is not the ideal dose for the treatment of COVID-19. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108(4):762-765. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diazgranados-Sanchez JA, Mejia-Fernandez JL, Chan-Guevara LS, Valencia-Artunduaga MH, Costa JL. Ivermectin as an adjunct in the treatment of refractory epilepsy [article in Spanish]. Rev Neurol. 2017;65(7):303-310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smit MR, Ochomo EO, Aljayyoussi G, et al. Safety and mosquitocidal efficacy of high-dose ivermectin when co-administered with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine in Kenyan adults with uncomplicated malaria (IVERMAL): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(6):615-626. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30163-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics – As-Treated Population

eTable 2. Clinical Manifestations of Patients at Baseline – Primary Analysis Population

eTable 3.Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Between the 75 Patients Receiving Ivermectin Who Were Excluded From Primary Analysis due to Error During Product Labeling and the Rest of the Cohort

eTable 4. Outcomes – As-Treated Population

eTable 5. Ordinal Scale Measure by Treatment Group and Study Visit – Primary Analysis Population

eTable 6. Ordinal Scale Measure by Treatment Group and Study Visit – As-Treated Population

eTable 7. Summary of Adverse Events – As-Treated Population

eFigure 1. Time to Resolution of Symptoms – As-Treated Population According to the Type of Placebo

eFigure 2. Time to Resolution of Symptoms – As-Treated Population

eFigure 3. Clinical Status on an 8-Point Ordinal Scale on Study Days 5, 8, 11 and 21 by Treatment Group – Primary Analysis Population

Data Sharing Statement