Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitor and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies are associated with a unique spectrum of complications termed immune-related adverse events (irAEs). The abdomen is the most frequent site of severe irAEs that require hospitalization with life-threatening consequences. Most abdominal irAEs such as enterocolitis, hepatitis, cholangiopathy, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, adrenalitis, and sarcoid-like reaction are initially detected on imaging such as ultrasonography (US), CT, MRI and fusion 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)-CT during routine surveillance of cancer therapy. Early recognition and diagnosis of irAEs and immediate management with cessation of immune modulator cancer therapy and institution of immunosuppressive therapy are necessary to avert morbidity and mortality. Diagnosis of irAEs is confirmed by tissue sampling or by follow-up imaging demonstrating resolution. Abdominal radiologists reviewing imaging on patients being treated with anti-cancer immunomodulators should be familiar with the imaging manifestations of irAEs.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) and chimeric antigen inhibitor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies have shown success as first- and second-line treatments against multiple cancers. These agents, first approved in 2011 by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of melanoma, now have rapidly expanded in indications to include treatment of small cell and non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric and colonic adenocarcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, uterine cervical carcinoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, lymphoma, and leukemia (Table 1). 1–4

Table 1.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Clinical Use

| Agent | Cellular Target | Indication |

|---|---|---|

| Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 inhibitor | Melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma (as combination therapy with nivolumab) |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 inhibitor | Melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, uterine cervical carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma |

| Nivolumab | PD-1 inhibitor | Melanoma, small cell lung cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| Cemiplimab | PD-1 inhibitor | Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma |

| Atezolizumab | PD-L1 inhibitor | Non-small-cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma |

| Durvalumab | PD-L1 inhibitor | Non-small-cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma |

| Avelumab | PD-L1 inhibitor | Merkel cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma |

Targeted activation of immune system cells for therapeutic destruction of tumor cells based on their surface antigens is also responsible for the spectrum of adverse reactions termed immune-related adverse events (irAEs) seen in patients treated with these agents. Patients treated with cancer immunotherapy undergo routine surveillance imaging with CT, MRI, or positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT), where clinically unsuspected irAEs are first detected. Imaging has been shown to detect 74% of irAEs. 5

While irAEs have been reported in almost every organ system, the abdomen is the most frequent site of severe irAEs that require hospitalization and have life-threatening consequences. 5–12 High-grade irAEs usually result in discontinuation of the immune modulator cancer therapy and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy (e.g. corticosteroids). Thus, these are clinically meaningful adverse events that should be recognized by abdominal radiologists. 1,13,14

In this article, we describe mechanisms of action of ICI and CAR-T therapies, the agents currently in clinical use, and presentation of irAEs in abdominopelvic imaging. Case examples illustrate irAEs in multiple modalities and describe accompanying clinical scenarios. Finally, imaging mimics of irAEs are presented to demonstrate that a high index of clinical suspicion is required to not confuse irAEs with other more familiar diagnoses.

Mechanism of cancer immunotherapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

ICIs are monoclonal antibodies that target cytotoxic T-cell receptors and tumor surface ligands including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1). One mechanism that tumor cells use to avoid destruction is to bind these surface antigens and competitively inhibit costimulatory binding by other immune cells that would otherwise facilitate T-cell-mediated activity against the tumor cells. ICIs suppress this inhibition, thus activating T-cell mediated tumor cell destruction. 15

CTLA-4 and PD1 are inhibitory immune checkpoint receptors that regulate T-cell activation by separate mechanisms. CTLA-4 counteracts T-cell activation by concurrent CD28 co-stimulatory receptor and T-cell receptor to antigen binding. 15–17 CTLA-4 functions in regulating autoimmunity by downregulating helper CD4 + T cells and enhancing immunosuppressive CD4 + regulatory T-cells. Whereas CTLA-4 mostly functions in T-cell activation, PD1 inhibitory receptor functions in limiting effector T-cells in tumors and non-tumor tissues where there are inflammatory responses to infection or autoimmune activity. PD1 is also present on other lymphocytes including B-cells and natural killer (NK) cells where its activity limits their ability to lyse target cells. Given that both CTLA-4 and PD1 regulate immune system activation that is not tumor-specific, their general inhibition for cancer treatment may be accompanied by increased autoimmune adverse events. 15

Imaging response patterns of tumors treated with ICIs can be different than those seen in patients on conventional chemotherapeutic regimens. For patients undergoing traditional cytotoxic systemic chemotherapy, success is defined as a decrease in size or disappearance of lesions over time and failure as an increase in size or appearance of new lesions. 18 In contrast, in patients treated with ICIs, successful treatment may manifest in a unique pattern known as pseudoprogression. 9,19 Here, transient enlargement of lesions or appearance of new lesions is initially observed followed by a decrease in lesion size on subsequent imaging. Differentiation of progressive disease from pseudoprogression requires repeat imaging 4–8 weeks after imaging evaluation of initial response to ICIs. However, in most patients, tumor enlargement does turn out to represent progressive disease rather than pseudoprogression, the latter of which has reported incidence of 10% or less. 20 The pathogenesis of pseudoprogression is not well understood but may relate to transient T-cell infiltration into sites of tumor. 20

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy

CAR-T therapy is used to treat B-cell malignancies such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and in B-cell lymphomas and represents another approach to inducing immune-mediated cancer therapy. 21 Treatment involves infusion of a patient’s own T-cells that have been engineered to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) targeting malignant cell surface antigens, such as CD19 on B-cell malignancies. A patient’s native T-lymphocytes are harvested using leukapheresis, artificially activated with antibodies, reprogrammed by virus-mediated genetic transduction of the CAR, expanded in number ex vivo, and then infused after the patient receives a preparatory chemotherapeutic induced depletion of in vivo lymphocytes (Figure 1a). 21 The CAR is made up by both tumor moiety recognition and T-cell signaling sites resulting in a host immune response against the tumor cells. 22 Aside from B-cell malignancies, ongoing trials are evaluating CAR-T cell therapy for solid organ malignancies and different types of lymphoma. 22

Figure 1.

(a) Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. In patients with B cell leukemias or lymphoma, the patient’s own T-cells are engineered ex vivo to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) targeting CD19 expressed on the surface of most malignant B cells. When infused back into the patient, the stimulation of cytotoxic immune response from the reprogrammed T cells kills the B cell tumors. (b) Immune response adverse events (irAEs). irAEs associated with cancer immunotherapy have been reported in almost every major organ and can present as acute or chronic inflammation.

Immune-related adverse events from immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy

irAEs are often clinically unsuspected. Severity can vary from mild to lethal. Symptoms depend on the involved organ and severity and, in the context of patients undergoing systemic therapy for metastatic cancer, are usually non-specific. A comparison of patients who developed radiographically evident irAEs versus those who did not found no difference in the performance status. 6 Consequently, concern for irAE is often first raised by the radiologist on surveillance imaging that the patient is undergoing to assess tumor status on therapy.

Clinical course and management

irAEs have been noted throughout the body (Figure 1b). The most common reported sites are bowel, liver, lungs, endocrine organs, musculoskeletal system, and skin but nearly every organ system can be affected including nervous and cardiovascular systems. 23 Frequency varies by molecular target of the agent in use, with irAEs of any grade reported in up to 82% of patients on PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitor therapy, 14,24–28 up to 86% of patients on CTLA-4 inhibitor therapy, 14 and up to 93% of patients on combination CTLA-4 and PD-1 inhibition. 14,29 Pathophysiological mechanisms of irAEs are not precisely defined, but hypotheses include T-cell activity against antigens on non-tumor cells, potentiation of the effect of pre-existing autoantibodies, increased inflammatory cytokine levels, and complement-mediated inflammation. 30

Time course of irAEs is variable ranging from transient to chronic. Symptoms most commonly occur within 12 weeks of beginning ICI therapy, but have been reported to occur up to 2 years after initiation and may even occur after cessation of treatment. 1,26,31,32 Endocrinopathies tend to occur later and persist longer than gastrointestinal and hepatic irAEs. 31 Median time to resolution of irAEs is 6–8 weeks, but some may persist and require treatment for years. 33 For radiologically evident abdominal irAEs, the median time to complete imaging resolution is 2.4 months. 6

Management of irAEs depends on grading of severity, which according to the United States National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 5.0), includes asymptomatic-mild (Grade 1), moderate (Grade 2), severe but not life-threatening (Grade 3), life-threatening (Grade 4), and death (Grade 5). 12,26,34,35 Management strategies include temporary withdrawal of the ICI and immunosuppressive therapies such systemic corticosteroids, anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies and mycophenolate mofetil. Supportive care options include hydration, analgesics, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, antihistamines, or hormone replacement therapy. Patients with severe symptoms will require hospitalization and subspecialty consultation such as gastroenterology, hepatology, or endocrinology. 34,36–39

Resumption of ICI therapy after irAE is associated with recurrent symptoms in a subgroup of patients. A cohort study of more than 24,000 patients demonstrated a recurrence of the same symptoms in 29% of patients following re-challenge with the same ICI. Colitis, hepatitis, and pneumonitis recurred significantly more often compared to other irAEs, whereas adrenal events recurred less commonly. 23 Patients may also experience a different irAE after discontinuation of ICI for irAE, rather than a recurrence of the same irAE. 10

Bowel irAEs

Colitis and enterocolitis have been reported in 5–25% of patients treated with ICIs, more commonly with CTLA-4 inhibitors than PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. 13,26,27,40 Studies of radiographically evident irAE enterocolitis have demonstrated similar incidence of 12–19%. 5–8 Mortality from toxic megacolon and bowel perforation in the setting of irAE colitis have been reported. 8,13,26,41

Imaging features of irAE colitis are usually detected on CT or MRI and include wall thickening, mural hyperenhancement, pericolonic fat stranding, mesenteric hyperemia, and fluid-filled bowel. On FDG PET-CT, tracer avidity of the affected bowel is seen. Distribution most commonly reported is pancolitis (Figure 2), but patterns of segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis and isolated rectosigmoid colitis in absence of diverticulosis have also been described. 5–8,20,32,42–44

Figure 2.

(a–c) Pancolitis. 76-year-old female undergoing pembrolizumab therapy for metastatic lung cancer presents with new onset diarrhea and elevated white blood cell count. Abdomen CT with contrast axial (a) and coronal reconstruction (b) images show long segment thickening throughout the colon. Coronal reconstruction image from a followup CT 8 months after cessation of immunotherapy. (c) shows a normal-appearing colon (solid arrows) but enlarging hepatic metastases (dashed arrows).

Colitis and diarrhea are the most commonly reported Grade 3–4 irAEs to lead to ICI discontinuation, occurring in up to 9% of patients for each. 14 Clinical presentation is most often watery diarrhea with abdominal discomfort. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding occurs in 20% of patients with colitis and may require colectomy. 13,42 Unrecognized enterocolitis and delayed treatment can lead to dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, and perforation and has been found to be associated with more severe disease. 33 Although less well documented, cases of enteritis without colitis, gastritis, and esophagitis attributed to ICI-related irAE also occur. 13,41,45–47

Persistent or severe symptoms warrant endoscopic evaluation for histological diagnosis. 45 Grossly, the affected bowel may appear friable with ulcers, exudates, granularity, and loss of vascular pattern, but may also in some cases appear normal. Histopathological findings of irAE enterocolitis are variable, but most commonly include intraepithelial neutrophilic infiltrate with increased crypt apoptosis and atrophy. A leukocytic infiltrate in the lamina propria may be seen but granulomas and findings of chronicity are absent. 31,43,48,49

Hepatic irAEs

Hepatitis is reported in 1–11% of patients on single-agent ICI therapy, more commonly with CTLA-4 than PD-1 and PD-L1 blockade, and in up to 13% of patients on combination CTLA-4 and PD-1 inhibitor therapy. 28,29,40,41,46,50 Hepatotoxicity is among the most commonly reported Grade 3–4 irAEs to lead to ICI discontinuation, occurring in up to 8% of patients. 14 Liver-failure related mortalities due to irAE hepatotoxicity have been reported. 1,41

Imaging findings in ICI hepatotoxicity include new hepatomegaly. On US, hypoechogenicity with periportal hyperechogenicity and thickening (“starry sky pattern”) has been seen with gallbladder wall thickening (Figure 3a). On CT or MRI, heterogeneous parenchymal enhancement with areas of geographical hypoenhancement, periportal and perihepatic edema, and portal lymphadenopathy have been reported (Figure 3b). 5–7,51,52 Edema is seen as diffuse parenchymal hypoattenuation on CT or T2 hyperintensity on MRI. While these features are non-specific and can be seen with any etiology of hepatic inflammation, irAE should be suspected in patients undergoing ICI therapy. 53

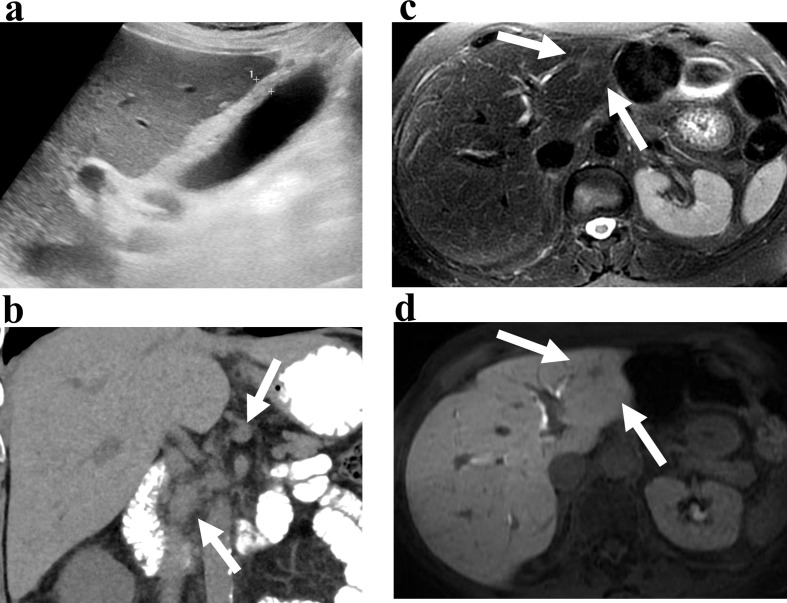

Figure 3.

(a, b) Hepatitis. 54-year-old male with metastatic lung cancer being treated with pembrolizumab presents with transaminitis. Ultrasound (a) shows a thickened gallbladder wall (calipers). Coronal reconstruction CT image (b) shows enlarged lymph nodes in the porta hepatis (arrows) and fat stranding suggesting inflammation. Non-focal liver biopsy showed checkpoint-inhibitor induced hepatitis. (c, d) Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor. 74-year-old female with metastatic lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Axial T2-weighed (c) and delayed phase image after gadoxetate disodium (d) shows a nodule in segments 2 and 3 (arrows) with hepatobiliary uptake of contrast. Focal biopsy showed inflammatory pseudotumor consistent with irAE.

Patients may be asymptomatic and present with hepatocellular or cholestatic laboratory abnormalities including transaminitis, hyperbilirubinemia, and elevated alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase. They may show symptoms of liver dysfunction such as jaundice, fatigue, abdominal pain, and nausea. 43,45 Biopsy most commonly shows non-specific panlobular active hepatitis with sinusoidal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and central vein endothelialitis, similar in some cases to acute autoimmune hepatitis and viral hepatitis. Periportal mononuclear cell infiltrate and centrilobular hepatitis patterns have also been reported but seem less common. 31,43,50,52,54

Pseudotumor, presenting as a focal hepatic lesion, can be seen in asymptomatic patients on long-term ICI therapy. On MRI, the lesion is ill-defined, mildly T2 hyperintense and most visible on hepatobiliary phase post-contrast imaging as hypoenhancing (Figure 3c and d). They resolve on follow-up imaging. Pathological analysis from a biopsy shows infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells consistent with an inflammatory pseudotumor.

Biliary irAEs

Bile duct irAEs are relatively uncommon but have been reported in up to 3% of patients on ICI therapy. 55–58 Imaging diagnosis of cholecystitis or cholangitis may precede the clinical presentation. 57 Clinical features include asymptomatic cholestatic lab abnormalities and symptomatic biliary obstruction or cholangitis including jaundice, right upper quadrant pain, fever, nausea, emesis, and fatigue. 55

Imaging findings on US, CT, or MRI may be that of cholecystitis including gallbladder distension, wall thickening, and pericholecystic inflammation. Increased FDG uptake in the wall may be noted on PET. Cholangitis is seen as bile duct wall thickening and hyperenhancement, biliary dilation, and multifocal biliary narrowing, best seen on MRCP or ERCP (Figure 4). 6,56–59 Imaging also plays the important role of excluding another source of biliary obstruction such as stone, stenosis, or metastatic disease of the liver. If there is suspicion for irAE-related cholangiopathy, MRI with MRCP would be the optimal imaging modality for detection.

Figure 4.

(a–c) Sclerosing cholangitis. 63-year-old female with lung adenocarcinoma being treated with nivolumab presents with abnormal liver function tests. Coronal MRI post contrast (a), MRCP (b), and ERCP (c) images show multifocal strictures and dilatation of the intra-hepatic bile ducts (solid arrows) and hyper enhancement of the bile duct wall (dashed arrows).

Liver biopsy may be necessary to differentiate from other causes of cholangiopathy. 56 Pathology shows evidence of cholestasis with periductal fibrosis and inflammatory infiltration, and variable ductopenia including a vanishing bile duct syndrome pattern. 52,54,55 Biliary duct wall biopsy by ERCP has shown neutrophilic infiltration. 57

Unlike hepatoxic irAE, biliary irAE responds less robustly and sometimes poorly to steroid therapy. 55,58 Endoscopic biliary stenting can lead to improvement in clinical and laboratory abnormalities in some patients. 57,58

Pancreatic irAEs

Pancreatitis is reported to occur in 1–13% of patients on ICI, more commonly when on combination rather than single agent therapy. 28,29,31,41,46 Most patients present with symptoms typical of pancreatitis such as abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, fatigue, and fever, but some have asymptomatic elevation in amylase or lipase. While most cases resolve with appropriate treatment, long-term pancreatic insufficiency and need for chronic enzyme replacement therapy has been reported. Diabetes mellitus necessitating insulin replacement therapy has been seen in <1% of patients, due to ICI-induced β cell dysfunction. 46,60

CT or MRI during the active phase of pancreatitis shows focal or diffuse acute parenchymal edema and enlargement with peripancreatic inflammation (Figure 5). Increased tracer uptake is seen on FDG-PET. Of note, pancreatic necrosis and peripancreatic collections have not been reported to date. Subsequent imaging after resolution of symptoms shows parenchymal atrophy and loss of normal lobulations Figure 6(Figure 5), an appearance similar to that seen after IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis. 5,6,46,61–63 Tissue sampling of the pancreas shows T-cell infiltrates. 31

Figure 5.

(a, b) Pancreatitis. 53-year-old male with Hurthle cell thyroid carcinoma being treated with pembrolizumab presents with abdominal pain and elevated serum amylase and lipase. CT with contrast (a) shows a diffusely enlarged, edematous-appearing pancreas with adjacent fat stranding (arrows). Immune modulator therapy was discontinued. CT 4 months later (b) shows resolution of inflammation and a shrunken pancreas with loss of normal lobulations (arrows) indicating fibrosis.

Figure 6.

(a, b) Adrenalitis. 69-year-old male with melanoma treated with ipilimumab. Coronal reconstruction CT (a) and coronal T 2-weighted MRI (b) image shows diffuse bilateral adrenal thickening (arrows). Fine needle aspiration diagnosed chronic inflammation consisted with irAE.

Endocrine irAEs

Adrenalitis and primary adrenal insufficiency is relatively uncommon but has been reported in <1–3% of patients as a manifestation of irAE. Clinically, adrenalitis can be life-threatening because of electrolyte abnormalities, dehydration, and shock with hypotension and altered mental status. 5,6,46,60,64–67 Less acute presentations of adrenal insufficiency may include fatigue, weakness, nausea, anorexia, and weight loss. 65 Adrenal insufficiency due to irAE may be permanent and require chronic steroid replacement therapy. 60

Imaging findings of acute adrenalitis from irAE are typically bilateral diffuse gland enlargement (Figure 6)Figure 7. 6,60,62,66,68,69 On CT or MRI, heterogeneity in the parenchyma and enhancement is seen. Glands also demonstrate increased tracer uptake on FDG-PET. In the chronic phase, bilateral gland atrophy is noted.

Figure 7.

Splenic sarcoid-like granulomas. 78 year-old malewithlung cancer being treated with pembrolizumab presents for surveillance imaging.CT with contrast coronal reconstruction image shows multiple hypoenhancinglesions (arrows) which were non FDG-avid (not shown).

Aside from the adrenal glands, irAE can involve any endocrine organ, including the pituitary and the thyroid. Hypophysitis leading to secondary gland dysfunction is more common than primary gland dysfunction and can be differentiated with a brain MRI and the appropriate serum testing. 60,62 Adrenal crisis induced death in the setting of irAE hypopituitarism has been reported. 70

Hypothyroidism has been reported in 2–22% of patients on ICI, more commonly with combination therapy and PD-1 inhibitors than CTLA-4 or PD-L1 inhibitors. 26,27,40,62 Hyperthyroidism is less common (2–7%) and typically only a temporary state followed by hypothyroidism. 27,46,71 Imaging findings are non-specific but may show new gland enlargement and heterogeneity of parenchymal enhancement on CT, heterogeneously hypoechoic echotexture and hyperemia on US, and new tracer uptake on FDG-PET. 5,7,63

Splenic and nodal sarcoid-like reaction irAEs

Focal splenic lesions, splenomegaly, mediastinal and abdominal lymphadenopathy, lung nodules, and skin lesions, which are pathologically composed of non-caseating epithelioid granulomata, have been seen in patients on ICI and characterized as a sarcoid-like reaction irAE. 5,7,72–76 The clinical presentation, organs involved, and histopathological findings are indistinguishable from sarcoidosis. The overall incidence of ICI associated sarcoid-like reaction ranges from <1–7%, with splenic involvement in 17% of these patients. 7,8,74

Imaging findings in the abdomen and pelvis include new splenomegaly and increased tracer uptake on FDG-PET-CT, which resolves after discontinuation of ICI. Multifocal, subcentimeter hypoattenuating splenic lesions in the absence of splenomegaly is also seen (Figure 7)Figure 5. 72,76 Because sole splenic involvement in sarcoid is rare, these lesions have been pathologically confirmed to represent sarcoid-like irAE and are self-limited, resolving without therapy. 72 Enlargement of abdominal lymph nodes without findings of infection and in the setting of tumor response elsewhere may also indicate sarcoid-like irAE, reported in <1%. 6,7,73,77

Splenic and lymph node sarcoid-like irAE is important to recognize as a possibility since mistaking it for disease progression can have a profound impact on cancer treatment decisions. 8 Clinically, patients with splenic and abdominal nodal involvement are often asymptomatic. 8 Thus, the radiologist raising the possibility of a sarcoid-like irAE will direct investigation toward serum angiotensin converting enzyme testing or biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Temporal relationship to ICI therapy and resolution with discontinuation are used for differentiation, although this can be difficult given the reported wide range of time-to-onset of irAE sarcoid-like reaction after ICI initiation.

Renal irAEs

Acute renal injury secondary to ICI therapy varies widely in reported incidence, from <1 to 29% of patients, more common with dual rather than single agent treatment. 41,46,78–83 Presentation may be an asymptomatic rise in serum creatinine or oliguria, pyuria, hematuria, proteinuria, and new or worsening hypertension. 78,80,81,83 Renal failure may require transient hemodialysis 78 and renal transplant rejection has also been seen. 83 Definite imaging correlates have not been reported although a case of new renal failure and bilateral renal enlargement on CT in a patient with irAE with rapid resolution after steroid therapy has been reported. 84

Immune-related adverse events from chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy

The most common irAE with CAR-T-cell therapy is cytokine release syndrome, a cytokine-mediated systemic inflammatory response reported in 57–93% of patients, typically occurring in the first 1–2 weeks following infusion. 4,22,85 Clinical presentation is fever, hypotension, tachycardia, and hypoxia, that can lead to multiorgan failure and death. In addition, a range of associated neurological toxicities, termed CAR-T cell related encephalopathy syndrome (CRES) or immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), have been reported in 39–64% of patients and may present with delirium, seizures, cognitive changes, ataxia, dysphagia, somnolence, or obtundation. 4,22 Consequently, for radiologists, irAEs associated with CAR-T therapy are most commonly detected on CT or MR neuroimaging as diffuse cerebral edema, foci of ischemic stroke, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. 22,85

In the abdomen, irAEs from CAR-T-cell therapy are usually asymptomatic and detected initially on imaging. Solid organ inflammation, including splenic inflammatory pseudotumor (Figure 8a and b) and pancreatitis (Figure 8c and d), have been observed and appear as FDG-avid lesions on PET. When presenting as a mass-like lesion, differentiation from tumor progression or recurrence is essential. Thus, radiologists should be aware that irAEs from CAR-T therapy can mimic tumor progression and guide further workup toward biopsy and appropriate hematological testing.

Figure 8.

(a, b) Splenic inflammatory pseudotumor. 33-year-old male with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma on treatment with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells. Axial contrast-enhanced CT (a) and fusion PET/CT (b) images shows a new solid heterogeneously enhancing FDG avid splenic lesion (arrow) shown to be a granuloma on biopsy. (c, d) Pancreatitis. 64-year-old male with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma after 2 doses of CAR T-cells. Contrast enhanced CT (c) shows enlarged pancreas with adjacent fat stranding (arrow) and ascites. FDG PET/CT fusion (b) image shows avid and diffuse pancreatic tracer uptake. Diagnosis of pancreatitis was confirmed with serum amylase and lipase and follow-up to resolution after cessation of CAR T therapy.

Mimics of irAEs on imaging

Abdominal irAEs often appear non-specific on imaging and can be confused with other inflammatory etiologies including infectious, autoimmune, and idiopathic. In patients undergoing cancer immunotherapy, irAE should be the first diagnostic consideration. Patient history, laboratory, microbiological, and histopathologic investigation are sometimes needed to differentiate irAE from other etiologies and diagnostic confirmation is based on clinical response to cessation of immunomodulator cancer therapy and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy.

IrAE colitis (Figure 2) may have a similar appearance to that from Clostridium difficile. Both most commonly present with pancolitis, seen as diffuse colonic wall thickening, hyperenhancement, and pericolonic fat stranding (Figure 9). Other more focal enterocolitides can resemble irAE including infectious enterocolitis, graft-versus-host-disease, or inflammatory bowel disease. 86 Differentiation from infectious enterocolitis is aided by stool testing for pathogens including Clostridium difficile toxins and viral DNA as well as lactoferrin, and calprotectin. 26,49 On occasion, if the clinical presentation and non-invasive testing cannot differentiate among the various etiologies, endoscopy may be indicated.

Figure 9.

(a, b) Clostridium difficile pancolitis. 63-year-old female with diarrhea and abdominal pain following antibiotic treatment for urinary tract infection. Abdomen CT with contrast axial (a) and coronal reconstruction (b) images show long segment thickening throughout the colon (solid arrows). Stool Clostridium difficile toxin was positive.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (Figure 10) can mimic the imaging appearance of irAE sclerosing cholangiopathy (Figure 4), with multifocal biliary structuring and intervening segmental dilation. Causes of secondary sclerosing cholangitis such as IgG-related cholangiopathy, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, and sequelae of ischemic cholangiopathy may also have a similar appearance. 87 Serum IgG4, autoantibody marker and viral hepatitis markers may be helpful to differentiate from other causes of cholangiopathy.

Figure 10.

(a, b) Primary sclerosing cholangitis. 35-year-old male undergoing surveillance imaging for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Coronal MRCP (a) and ERCP (b) images show multifocal strictures and dilatation of the intra-hepatic bile ducts (arrows).

Pancreatic inflammation from either type I or diffuse IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis (Figure 11) or interstitial edematous pancreatitis from gallstones or alcohol can mimic irAE pancreatitis Figure 6(Figure 5) on imaging. 88 Serum markers of pancreatitis are typically abnormal for all causes. IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis may be particularly difficult to differentiate from irAE as both respond to corticosteroid therapy.

Figure 11.

(a, b) IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis. 76-year-old male with right abdominal pain and elevated lipase. CT with contrast axial (a) and coronal reconstruction (b) images show a diffusely enlarged, edematous appearing pancreas with adjacent fat stranding and circumferential rind of peripancreatic soft tissue attenuation (arrows). Tissue sampling revealed storiform fibrosis and chronic inflammation with IgG4 staining.

Conventional sarcoid and irAE sarcoid-like reaction resemble each other clinically and on pathology, both presenting as non-caseating granulomas. Both can be self-limited or may require corticosteroid therapy for systemic symptoms. Multifocal hypoattenuating focal lesions representing granulomas in the spleen of a sarcoid patient (Figure 12) resemble that in a cancer patient undergoing an irAE (Figure 7) Figure 5. 89,90 The diagnostic dilemma is a concern for metastatic disease progression and, on occasion, will require biopsy to differentiate.

Figure 12.

(a, b) Splenic sarcoid granulomas. 66-year-old male with incidentally detected splenic lesions. CT with contrast axial (a) and coronal reconstruction (b) images shows multiple hypoenhancing lesions (arrows). Biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation consistent with sarcoidosis.

Conclusion

As cancer immunotherapy becomes more widely used across multiple malignancies, radiologists will encounter irAEs more often. Radiologically evident irAEs, especially in the abdominal and pelvic organs, can be life-threatening and may mimic disease progression. As most irAEs are detected first on routine cancer surveillance imaging, abdominal radiologists should be familiar with the spectrum of imaging manifestations in order to facilitate prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Sue Loomis for original graphic illustration.

Contributor Information

Mark A Anderson, Email: mark.anderson@mgh.harvard.edu.

Vikram Kurra, Email: vkurra@partners.org.

William Bradley, Email: william.bradley@mgh.harvard.edu.

Aoife Kilcoyne, Email: akilcoyne1@mgh.harvard.edu.

Amirkasra Mojtahed, Email: amojtahed@mgh.harvard.edu.

Susanna I Lee, Email: slee0@partners.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2010; 363: 711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kalisz KR, Ramaiya NH, Laukamp KR, Gupta A. Immune checkpoint inhibitor Therapy–related pneumonitis: patterns and management. RadioGraphics 2019; 39: 1923–37. doi: 10.1148/rg.2019190036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neelapu SS. Managing the toxicities of car T-cell therapy. Hematol Oncol 2019; 37 Suppl 1: 48–52. doi: 10.1002/hon.2595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tran E, Longo DL, Urba WJ. A milestone for CAR T cells. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 2593–6. 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1714680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mekki A, Dercle L, Lichtenstein P, Marabelle A, Michot J-M, Lambotte O, et al. Detection of immune-related adverse events by medical imaging in patients treated with anti-programmed cell death 1. Eur J Cancer 2018; 96: 91–104. 1990. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alessandrino F, Sahu S, Nishino M, Adeni AE, Tirumani SH, Shinagare AB, et al. Frequency and imaging features of abdominal immune-related adverse events in metastatic lung cancer patients treated with PD-1 inhibitor. Abdom Radiol 2019; 44: 1917–27. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-01935-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tirumani SH, Ramaiya NH, Keraliya A, Bailey ND, Ott PA, Hodi FS, et al. Radiographic profiling of immune-related adverse events in advanced melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol Res 2015; 3: 1185–92. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bronstein Y, Ng CS, Hwu P, Hwu W-J. Radiologic manifestations of immune-related adverse events in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing anti-CTLA-4 antibody therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 197: W992–1000. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kwak JJ, Tirumani SH, Van den Abbeele AD, Koo PJ, Jacene HA. Cancer immunotherapy: imaging assessment of novel treatment response patterns and immune-related adverse events. RadioGraphics 2015; 35: 424–37. doi: 10.1148/rg.352140121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas R, Sebastian B, George T, Majeed NF, Akinola T, Laferriere SL, et al. A review of the imaging manifestations of immune check point inhibitor toxicities. Clin Imaging 2020; 64: 70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Braschi-Amirfarzan M, Tirumani SH, Hodi FS, Nishino M. Immune-Checkpoint inhibitors in the era of precision medicine: what radiologists should know. Korean J Radiol 2017; 18: 42–53. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2017.18.1.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. www.cancer.gov .Bethesda, Maryland: Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 5.0; 2017. Nov 27 [cited 2020 Jun 1]. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beck KE, Blansfield JA, Tran KQ, Feldman AL, Hughes MS, Royal RE, et al. Enterocolitis in patients with cancer after antibody blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 2283–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12: 252–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riley JL. Pd-1 signaling in primary T cells. Immunol Rev 2009; 229: 114–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00767.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parry RV, Chemnitz JM, Frauwirth KA, Lanfranco AR, Braunstein I, Kobayashi SV, et al. Ctla-4 and PD-1 receptors inhibit T-cell activation by distinct mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25: 9543–53. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9543-9553.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 228–47. 1990. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang GX, Kurra V, Gainor JF, Sullivan RJ, Flaherty KT, Lee SI, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor cancer therapy: spectrum of imaging findings. RadioGraphics 2017; 37: 2132–44. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017170085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nishino M, Hatabu H, Hodi FS. Imaging of cancer immunotherapy: current approaches and future directions. Radiology 2019; 290: 9–22. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018181349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maus MV, Levine BL. Chimeric antigen receptor T‐Cell therapy for the community oncologist. Oncologist 2016; 21: 608–17. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN. Recent advances in car T-cell toxicity: mechanisms, manifestations and management. Blood Rev 2019; 34: 45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dolladille C, Ederhy S, Sassier M, Cautela J, Thuny F, Cohen AA, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge after immune-related adverse events in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6: 865–71. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Horvat TZ, Adel NG, Dang T-O, Momtaz P, Postow MA, Callahan MK, et al. Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at Memorial Sloan Kettering cancer center. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 3193–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of Anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boutros C, Tarhini A, Routier E, Lambotte O, Ladurie FL, Carbonnel F, et al. Safety profiles of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies alone and in combination. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016; 13: 473–86. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Robert C, Ribas A, Schachter J, Arance A, Grob J-J, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-006): post-hoc 5-year results from an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2019; 20: 1239–51. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30388-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robert C, Ribas A, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, Hamid O, Kefford R, et al. Anti-programmed-death-receptor-1 treatment with pembrolizumab in ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma: a randomised dose-comparison cohort of a phase 1 trial. The Lancet 2014; 384: 1109–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60958-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 122–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-Related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 158–68. 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 2691–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wolchok JD, Neyns B, Linette G, Negrier S, Lutzky J, Thomas L, et al. Ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2, dose-ranging study. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 155–64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70334-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weber JS, Dummer R, de Pril V, Lebbé C, Hodi FS. Patterns of onset and resolution of immune-related adverse events of special interest with ipilimumab: detailed safety analysis from a phase 3 trial in patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer 2013; 119: 1675–82. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, Atkins MB, Brassil KJ, Caterino JM, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018; 36: 1714–68. 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, Bingham CO, Brogdon C, Dadu R, et al. Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for immunotherapy of cancer (SITC) toxicity management working group. J Immunother Cancer 2017; 5. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0300-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, Collins M, Carbonnel F, Postel-Vinay S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer 2016; 54: 139–48. 1990. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Myers G. Immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a brief review. Curr. Oncol. 2018; 25: 342–7. doi: 10.3747/co.25.4235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stucci S, Palmirotta R, Passarelli A, Silvestris E, Argentiero A, Lanotte L, et al. Immune-related adverse events during anticancer immunotherapy: pathogenesis and management. Oncol Lett 2017; 14: 5671–80. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Topalian SL, Sznol M, McDermott DF, Kluger HM, Carvajal RD, Sharfman WH, et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 1020–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Johnson DB, Chandra S, Sosman JA. Immune checkpoint inhibitor toxicity in 2018. JAMA 2018; 320: 1702–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Voskens CJ, Goldinger SM, Loquai C, Robert C, Kaehler KC, Berking C, et al. The price of tumor control: an analysis of rare side effects of anti-CTLA-4 therapy in metastatic melanoma from the ipilimumab network. PLoS One 2013; 8: e53745. cited 2020 Apr 23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Barina AR, Bashir MR, Howard BA, Hanks BA, Salama AK, Jaffe TA. Isolated recto-sigmoid colitis: a new imaging pattern of ipilimumab-associated colitis. Abdom Radiol 2016; 41: 207–14. doi: 10.1007/s00261-015-0560-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Karamchandani DM, Chetty R. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced gastrointestinal and hepatic injury: pathologists’ perspective. J Clin Pathol 2018; 71: 665–71. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim KW, Ramaiya NH, Krajewski KM, Shinagare AB, Howard SA, Jagannathan JP, et al. Ipilimumab-associated colitis: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 200: W468–74. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cramer P, Bresalier RS. Gastrointestinal and hepatic complications of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2017; 19: 3. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0540-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hofmann L, Forschner A, Loquai C, Goldinger SM, Zimmer L, Ugurel S, et al. Cutaneous, gastrointestinal, hepatic, endocrine, and renal side-effects of anti-PD-1 therapy. Eur J Cancer 2016; 60: 190–209. 1990. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Messmer M, Upreti S, Tarabishy Y, Mazumder N, Chowdhury R, Yarchoan M, et al. Ipilimumab-Induced enteritis without colitis: a new challenge. Case Rep Oncol 2016; 9: 705–13. doi: 10.1159/000452403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eigentler TK, Hassel JC, Berking C, Aberle J, Bachmann O, Grünwald V, et al. Diagnosis, monitoring and management of immune-related adverse drug reactions of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2016; 45: 7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reddy HG, Schneider BJ, Tai AW. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis and hepatitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2018; 9: 180. 19. doi: 10.1038/s41424-018-0049-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suzman DL, Pelosof L, Rosenberg A, Avigan MI. Hepatotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: an evolving picture of risk associated with a vital class of immunotherapy agents. Liver International 2018; 38: 976–87. doi: 10.1111/liv.13746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alessandrino F, Tirumani SH, Krajewski KM, Shinagare AB, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya NH, et al. Imaging of hepatic toxicity of systemic therapy in a tertiary cancer centre: chemotherapy, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, molecular targeted therapies, and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin Radiol 2017; 72: 521–33. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim KW, Ramaiya NH, Krajewski KM, Jagannathan JP, Tirumani SH, Srivastava A, et al. Ipilimumab associated hepatitis: imaging and clinicopathologic findings. Invest New Drugs 2013; 31: 1071–7. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-9939-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sharma A, Houshyar R, Bhosale P, Choi J-I, Gulati R, Lall C. Chemotherapy induced liver abnormalities: an imaging perspective. Clin Mol Hepatol 2014; 20: 317–26. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2014.20.3.317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Johncilla M, Misdraji J, Pratt DS, Agoston AT, Lauwers GY, Srivastava A, et al. Ipilimumab-associated hepatitis: clinicopathologic characterization in a series of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2015; 39: 1075–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Doherty GJ, Duckworth AM, Davies SE, Mells GF, Brais R, Harden SV, et al. Severe steroid-resistant anti-PD1 T-cell checkpoint inhibitor-induced hepatotoxicity driven by biliary injury. ESMO Open 2017; 2: e000268. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gelsomino F, Vitale G, Ardizzoni A. A case of nivolumab-related cholangitis and literature review: how to look for the right tools for a correct diagnosis of this rare immune-related adverse event. Invest New Drugs 2018; 36: 144–6. doi: 10.1007/s10637-017-0484-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kashima J, Okuma Y, Shimizuguchi R, Chiba K. Bile duct obstruction in a patient treated with nivolumab as second-line chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a case report. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2018; 67: 61–5. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2062-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kawakami H, Tanizaki J, Tanaka K, Haratani K, Hayashi H, Takeda M, et al. Imaging and clinicopathological features of nivolumab-related cholangitis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Invest New Drugs 2017; 35: 529–36. doi: 10.1007/s10637-017-0453-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pourvaziri A, Parakh A, Biondetti P, Sahani D, Kambadakone A. Abdominal CT manifestations of adverse events to immunotherapy: a primer for radiologists. Abdom Radiol 2020; 45: 2624–36. doi: 10.1007/s00261-020-02531-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Byun DJ, Wolchok JD, Rosenberg LM, Girotra M. Cancer immunotherapy — immune checkpoint blockade and associated endocrinopathies. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2017; 13: 195–207. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hoadley A, Sandanayake N, Long GV. Atrophic exocrine pancreatic insufficiency associated with anti-PD1 therapy. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: 434–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ryder M, Callahan M, Postow MA, Wolchok J, Fagin JA. Endocrine-related adverse events following ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma: a comprehensive retrospective review from a single institution. Endocr Relat Cancer 2014; 21: 371–81. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wachsmann JW, Ganti R, Peng F. Immune-mediated disease in ipilimumab immunotherapy of melanoma with FDG PET-CT. Acad Radiol 2017; 24: 111–5. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Corsello SM, Barnabei A, Marchetti P, De Vecchis L, Salvatori R, Torino F. Endocrine side effects induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98: 1361–75. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Iqbal I, Khan MAA, Ullah W, Nabwani D. Nivolumab-induced adrenalitis. BMJ Case Rep 2019; 12: e231829. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-231829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Trainer H, Hulse P, Higham CE, Trainer P, Lorigan P. Hyponatraemia secondary to nivolumab-induced primary adrenal failure. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 2016; 2016. doi: 10.1530/EDM-16-0108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hanna RM, Selamet U, Bui P, Sun S-F, Shenouda O, Nobakht N, et al. Acute kidney injury after Pembrolizumab-Induced Adrenalitis and adrenal insufficiency. Case Rep Nephrol Dial 2018; 8: 171–7. doi: 10.1159/000491631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bacanovic S, Burger IA, Stolzmann P, Hafner J, Huellner MW. Ipilimumab-Induced Adrenalitis: a possible pitfall in 18F-FDG-PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med 2015; 40: e518–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Min L, Hodi FS. Anti-Pd1 following ipilimumab for mucosal melanoma: durable tumor response associated with severe hypothyroidism and rhabdomyolysis. Cancer Immunology Research 2014; 2: 15–18. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, Robert C, Grossmann K, McDermott D, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2006–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Osorio JC, Ni A, Chaft JE, Pollina R, Kasler MK, Stephens D, et al. Antibody-mediated thyroid dysfunction during T-cell checkpoint blockade in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Annals of Oncology 2017; 28: 583–9. 01. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Andersen R, Nørgaard P, Al-Jailawi MKM, Svane IM. Late development of splenic sarcoidosis-like lesions in a patient with metastatic melanoma and long-lasting clinical response to ipilimumab. Oncoimmunology 2014; 3: e954506. doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.954506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Cheshire SC, Board RE, Lewis AR, Gudur LD, Dobson MJ. Pembrolizumab-induced Sarcoid-like reactions during treatment of metastatic melanoma. Radiology 2018; 289: 564–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gkiozos I, Kopitopoulou A, Kalkanis A, Vamvakaris IN, Judson MA, Syrigos KN. Sarcoidosis-Like reactions induced by checkpoint inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol 2018; 13: 1076–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rambhia PH, Reichert B, Scott JF, Feneran AN, Kazakov JA, Honda K, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced sarcoidosis-like granulomas. Int J Clin Oncol 2019; 24: 1171–81. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01490-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wilgenhof S, Morlion V, Seghers AC, Du Four S, Vanderlinden E, Hanon S, et al. Sarcoidosis in a patient with metastatic melanoma sequentially treated with anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody and selective BRAF inhibitor. Anticancer Res 2012; 32: 1355–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Reuss JE, Kunk PR, Stowman AM, Gru AA, Slingluff CL, Gaughan EM. Sarcoidosis in the setting of combination ipilimumab and nivolumab immunotherapy: a case report & review of the literature. J Immunother Cancer 2016; 4: 94. doi: 10.1186/s40425-016-0199-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Cortazar FB, Marrone KA, Troxell ML, Ralto KM, Hoenig MP, Brahmer JR, et al. Clinicopathological features of acute kidney injury associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Kidney Int 2016; 90: 638–47. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Fadel F, Karoui KE, Knebelmann B. Anti-CTLA4 antibody-induced lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 211–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0904283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mamlouk O, Selamet U, Machado S, Abdelrahim M, Glass WF, Tchakarov A, et al. Nephrotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors beyond tubulointerstitial nephritis: single-center experience. J Immunother Cancer 2019; 7: 2. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0478-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Murakami N, Motwani S, Riella LV. Renal complications of immune checkpoint blockade. Curr Probl Cancer 2017; 41: 100–10. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Shirali AC, Perazella MA, Gettinger S. Association of acute interstitial nephritis with programmed cell death 1 inhibitor therapy in lung cancer patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 68: 287–91. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wanchoo R, Karam S, Uppal NN, Barta VS, Deray G, Devoe C, et al. Adverse renal effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a narrative review. Am J Nephrol 2017; 45: 160–9. doi: 10.1159/000455014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Forde PM, Rock K, Wilson G, O'Byrne KJ. Ipilimumab-induced immune-related renal failure – a case report. Anticancer Res 2012; 32: 4607–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Rubin DB, Danish HH, Ali AB, Li K, LaRose S, Monk AD, et al. Neurological toxicities associated with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Brain 2019; 142: 1334–48. 01. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Horton KM, Corl FM, Fishman EK. CT evaluation of the colon: inflammatory disease. RadioGraphics 2000; 20: 399–418. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.2.g00mc15399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Vitellas KM, Keogan MT, Freed KS, Enns RA, Spritzer CE, Baillie JM, et al. Radiologic manifestations of sclerosing cholangitis with emphasis on Mr cholangiopancreatography. RadioGraphics 2000; 20: 959–75. quiz 1108–9, 1112. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl04959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Vlachou PA, Khalili K, Jang H-J, Fischer S, Hirschfield GM, Kim TK. IgG4-Related sclerosing disease: autoimmune pancreatitis and extrapancreatic manifestations. RadioGraphics 2011; 31: 1379–402. doi: 10.1148/rg.315105735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Warshauer DM. Splenic sarcoidosis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2007; 28: 21–7. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Warshauer DM, Dumbleton SA, Molina PL, Yankaskas BC, Parker LA, Woosley JT. Abdominal CT findings in sarcoidosis: radiologic and clinical correlation. Radiology 1994; 192: 93–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.192.1.8208972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]