Abstract

Background

The chloroacetamide herbicides pretilachlor is an emerging pollutant. Due to the large amount of use, its presence in the environment threatens human health. However, the molecular mechanism of pretilachlor degradation remains unknown.

Results

Now, Rhodococcus sp. B2 was isolated from rice field and shown to degrade pretilachlor. The maximum pretilachlor degradation efficiency (86.1%) was observed at a culture time of 5 d, an initial substrate concentration 50 mg/L, pH 6.98, and 30.1 °C. One novel metabolite N-hydroxyethyl-2-chloro-N-(2, 6-diethyl-phenyl)-acetamide was identified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Draft genome comparison demonstrated that a 32,147-bp DNA fragment, harboring gene cluster (EthRABCDB2), was absent from the mutant strain TB2 which could not degrade pretilachlor. The Eth gene cluster, encodes an AraC/XylS family transcriptional regulator (EthRB2), a ferredoxin reductase (EthAB2), a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (EthBB2), a ferredoxin (EthCB2) and a 10-kDa protein of unknown function (EthDB2). Complementation with EthABCDB2 and EthABDB2, but not EthABCB2 in strain TB2 restored its ability to degrade chloroacetamide herbicides. Subsequently, codon optimization of EthABCDB2 was performed, after which the optimized components were separately expressed in Escherichia coli, and purified using Ni-affinity chromatography. A mixture of EthABCDB2 or EthABDB2 but not EthABCB2 catalyzed the N-dealkoxymethylation of alachlor, acetochlor, butachlor, and propisochlor and O-dealkylation of pretilachlor, revealing that EthDB2 acted as a ferredoxin in strain B2. EthABDB2 displayed maximal activity at 30 °C and pH 7.5.

Conclusions

This is the first report of a P450 family oxygenase catalyzing the O-dealkylation and N-dealkoxymethylation of pretilachlor and propisochlor, respectively. And the results of the present study provide a microbial resource for the remediation of chloroacetamide herbicides-contaminated sites.

Keywords: Chloroacetanilide herbicides, O-Dealkylation, N-Dealkoxymethylation, Rhodococcus, P450 family oxygenase

Introduction

Chloroacetamide herbicides are preemergence herbicides utilized to control broadleaf weeds and annual grasses in the cultivation of soybeans, corn, rice and many other crops [1, 2]. The primary representative chloroacetamide herbicides, including acetochlor, alachlor, propisochlor, metolachlor, butachlor and pretilachlor are N-alkoxyalkyl-N-chloroacetyl-substituted aniline derivatives based on their structures. Due to their excessive application and chemical stability, chloroacetamide herbicides have been detected in the surface water, groundwater and drinking water in many countries [3–6]. Chloroacetamide herbicides have been reported to be highly deleterious to many aquatic organisms and are known to be carcinogenic to humans [7, 8].

Pretilachlor is a pre-planting or post-emergence herbicide used to eliminate broad-leaved weeds, grasses and sedges in rice fields [9]. Pretilachlor residue in soil can damage rice leaves and toxic to cyanobacteria [10, 11]. Pretilachlor exposure was shown to lead to apoptosis, immunotoxicity, endocrine disruption and oxidative stress in gestating zebrafish [12] and hepatic P4502B subfamily-dependent enzyme activity in rat liver [13]. Therefore, great concerns have been raised about elucidating the degradation mechanism of chloroacetamide herbicides.

Microbial metabolism is considered to be an important method for the removal of chloroacetanilide herbicides in ecosystems [14, 15]. At present, many chloroacetamide herbicides-degrading microorganisms have been reported, the initial metabolic steps of which primarily involves two pathways: glutathione mediation reaction [16, 17] and N-dealkylation [18, 19]. N-Dealkylation is primarily performed by enzymes in the Rieske non-heme iron oxygenase (RHO) and cytochrome P450 families in living organisms [20, 21]. Chen et al. reported an RHO system, CndABC, that can execute the N-dealkylation toward acetochlor, alachlor and butachlor, but not toward propisochlor, pretilachlor or metolachlor, in Sphingomonad strains DC-2 and DC-6 [18]. Wang et al. showed that Escherichia coli expressing EthBADT3-1 (from Rhodococcus sp. T3-1) acquired N-deethoxymethylase activity toward acetochlor resulting in the conversion of acetochlor to CMEPA, whereas this activity was not observed toward metolachlor or pretilachlor [19, 22]. Currently, the molecular mechanism for the dealkylation of propisochlor, metolachlor and pretilachlor by microorganisms remains unknown.

The strain Rhodococcus sp. B2 was isolated from a rice field in which pretilachlor had been applied for many years. Strain B2 can degrade pretilachlor via an initial reaction of O-dealkylation. In the present study, the components of gene cluster EthRABCDB2 were cloned and their function were verified in Rhodococcus sp. TB2, Codon optimization of the EthABCDB2 gene cluster was performed, and the genes were individually expressed in Escherichia coli, and purified using Ni-affinity chromatography. A mixture of EthABCDB2 or EthABDB2 but not EthABCB2 displayed N-dealkoxymethylation activity toward alachlor, acetochlor, butachlor and propisochlor and O-dealkylation activity to pretilachlor, revealing a new mechanism for the initial degradation of chloroacetamide herbicide.

Materials and methods

Chemical reagents, medium, isolation and characterization of pretilachlor-degrading bacteria

Butachlor, alachlor, acetochlor, metolachlor, propisochlor, pretilachlor, 2-chloro-N-(2,6-diethyl phenyl) acetamide (CDEPA) and 2-Chloro-N-(2-methyl-6-ethylphenyl) acetamide (CMEPA) was purchased from Alfa-Aesar (Shanghai, China). Acetonitrile (HPLC grade) was from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China). Other reagents used in the present study were the AR grade. The composition of mineral salts medium (MSM), Luria–Bertani medium (LB), as well as the method of isolation, characterization and identification of pretilachlor degradation strain were previously described by Liu et al. [23, 24]. Briefly, 2 g of soil, collected from the rice field (Jiangsu, China), was added to 100 mL MSM containing 50 mg/L pretilachlor and shaken at 180 rpm, 30 °C. Then, after 5 days, 5 mL culture was transferred into fresh MSM and cultured under the same conditions. The concentration of pretilachlor was determined by HPLC, and a culture capable of degrading pretilachlor was selected to dilute and bacterial pure culture which can produce transparent circle in the plate containing 100 mg/L pretilachlor was picked.

Strain B2 was identified in line with Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology [25] and by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain B2 was aligned with sequence in EzTaxon-e server database (https://www.ezbiocloud.net/). A phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA (version 7.0) [26] using the neighbor-joining method.

Optimization of pretilachlor-degrading conditions

The effects of cultivation conditions on pretilachlor degradation were assessed using the response surface methodology with a central composite design (CCD) procedure. Where the experiment was designed and performed with Design Expert (version 12.0.3; StatEase, Inc. Minneapolis, USA). Three factors, pH, temperature and inoculum size, were considered independent variables (Table 1), while the degradation rate of 50 mg/L of pretilachlor by strain B2 after 5 days served as the response variable. 20 runs with three replicates were performed. And an uninoculated culture served as a control. Then the experimental data were used in an empirical model analysis (quadratic polynomial equation):

| 1 |

Y: predicted response; Xi and Xj: variables; B: constant; bi: linear coefficient; bij: interaction coefficient; bii: quadratic coefficient.

Table 1.

The design table of central composite design (CCD)

| Symbols | Factors | Levels of variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − Alpha | Low (− 1) | Medium (0) | High (1) | + Alpha | ||

| A | pH | 5.3 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8.7 |

| B | Temperature (℃) | 21.6 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 38.4 |

| C | Inoculation (g/L) | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.37 |

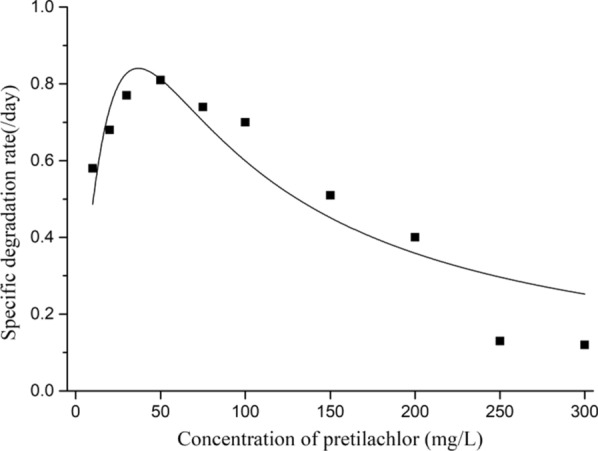

Kinetics of pretilachlor-degradation by strain B2

Batch experiments were performed to analyze the effects of the initial concentration of pretilachlor on the degradation efficiency. Degradation ability was detected at different pretilachlor concentrations (10, 20, 30, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 200, 250, 300 mg/L) under the optimum conditions. The pretilachlor degradation efficiency was detected by HPLC as described below. The data were fitted to the Andrews model of substrate inhibition kinetics [27]:

| 2 |

| 3 |

S: concentration of pretilachlor; Ki: inhibition constant; Ks: half- saturation constant; and qmax: maximum degradation efficiency of pretilachlor; Sm: the critical inhibitor concentration of pretilachlor.

Plasmids, strains and culture conditions

The plasmids and strains used in the present study are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. The primers are presented in Additional file 1: Table S2. E. coli was cultivated at 37 °C with antibiotics added if necessary. Strain B2 was grown in LB medium supplemented with 100 mg/L pretilachlor at 30 °C. The strain B2 derivatives and other strains were all cultivated at 30 °C in LB medium.

Genome sequencing, annotation, and genome analysis

DNA extraction was in line with the method of Sambrook et al. [28]. Genome sequencing of strains B2 and TB2 was performed using the Illumina MiSeq system by GENEWIZ Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China). The BLAST search against the databases of Nr protein, KEGG, COG and Swiss-Prot databases were used for annotation. To determine the absent DNA fragment in strain TB2, a genome comparison of strain B2 and TB2 was carried out using the Mauve1.2.3 [29]. Chromosome walking was performed with SEFA-PCR [30]. Protein sequences were aligned with the ClustalX program [31], after which MEGA 7.0 [26] was used to build phylogenetic tree.

Functional complement in strains TB2 and R-XP

In order to avoid the codon usage bias in Rhodococcus, the original promoter of the Eth cluster from Rhodococcus sp.B2 was used to express in the following fragments. A 4964-bp fragment EthRABCDB2, a 4597-bp fragment EthRABCB2 and a 3785-bp fragment EthABCDB2, were cloned from the genome of strain B2. A 3388-bp fragment EthABDB2 was amplified from the plasmid pQEth3. The fragments EthRABCDB2 and EthRABCB2, were ligated into the HindIII-SpeI sites of the Rhodococcus-Escherichia coli shuttle vector pRESQ [32], yielding pQEth1 and pQEth2, respectively. The fragments EthABCDB2 and EthABDB2, were cloned into the shuttle vector pRESQ using a Gibson Seamless Assembly Kit (HaiGene Co., Ltd). The constructed vectors were first transformed to E. coli DH5α and then introduced into strains TB2 or R-XP by electrotransformation [33]. All the recombinant plasmids were confirmed by sequencing. The abilities of the recombinant plasmid-harboring E. coli DH5α and TB2 strains to degrade pretilachlor were detected by whole-cell biotransformation experiments according to the method of Liu et al. with some modifications [34]. Briefly, the post-log phase transformants were collected by centrifugation, washed with MSM two times, and then resuspended in 20 mL MSM to a final OD600nm value of approximately 1.0. Each cell suspension was incubated with substrate at a final concentration of 100 mg/L and cultivated at 160 rpm and 30 °C. Samples were harvested at appropriate intervals, and the degradation metabolites were monitored by HPLC as described below.

Expression of EthABCD and purification of the recombinant proteins

To express EthABCD and EthABC under T7 promoter, a 3234-bp and a 2867-bp fragment without original promoter were PCR amplified from strain B2 with the primer pairs pET-EthF1/pET-EthR, pET-EthF2/pET-EthR, respectively. The PCR products were cloned into plasmid pET-29a(+) to construct the recombinant plasmids pET-EthABCD and pET-EthABC. E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pET-EthABCD or pET-EthABC was grown at 37 °C until OD600 value of 0.6, and then incubated at 16 °C for 12 h after adding 0.5 mM IPTG. Subsequently, the degradation function was verified by whole-cell transformation with the centrifugal collection cells according to the above description.

Fragments of the gene cluster EthABCD, synthesized by GenScript company depending on E. coli codon usage form, were amplified with the primers shown in Table 2. The products were ligated into the corresponding site of expression plasmid pET29a(+) and transformed as recombiant plasmids into E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS. Each recombinant plasmid was verified by sequencing. And gene expression and recombinant proteins purification were performed as the description of Hussain et al. [35]. SDS-PAGE was used to determine the protein molecular weight, and the protein concentrations were calculated by the Bradford method [36].

Table 2.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the response surface quadratic model

| Source | Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean square | F-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 1489.53 | 9 | 165.5 | 21.17 | < 0.0001 | Significant |

| A-pH | 54.42 | 1 | 54.42 | 6.96 | 0.0248 | |

| B-T | 5.29 | 1 | 5.29 | 0.6762 | 0.4301 | |

| C-I | 89.97 | 1 | 89.97 | 11.51 | 0.0069 | |

| AB | 87.12 | 1 | 87.12 | 11.14 | 0.0075 | |

| AC | 45.51 | 1 | 45.51 | 5.82 | 0.0365 | |

| BC | 4.62 | 1 | 4.62 | 0.591 | 0.4598 | |

| A2 | 1118.5 | 1 | 1118.5 | 143.06 | < 0.0001 | |

| B2 | 152.73 | 1 | 152.73 | 19.53 | 0.0013 | |

| C2 | 8.27 | 1 | 8.27 | 1.06 | 0.3279 | |

| Residual | 78.19 | 10 | 7.82 | |||

| Lack of fit | 60.88 | 5 | 12.18 | 3.52 | 0.0969 | Not significant |

| Pure error | 17.31 | 5 | 3.46 | |||

| Cor total | 1567.72 | 19 |

Enzyme activity assays

The enzymatic degradation of several chloroacetanilide herbicides activity was assessed at 30 ℃ for 1 h in a 1 mL mixture comprising (20 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.5, 0.15 μg EthBB2, 0.58 μg EthAB2, 0.17 μg EthCB2, 0.12 μg EthDB2, 1 mM NADH, 0.1 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM Fe2+, and 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). The reaction was started after adding the substrates at a final concentration of 0.5 mM, The assays were stopped by the addition of 2 mL of dichloromethane, and the disappearance of the substrates was monitored by HPLC. Metabolites were determined by GC–MS analysis as described below. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to generate of 1 nmol of product per minute.

The optimal pH for the reaction mixtures at 30 °C was determined in four different buffers: 20 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.8–5.8); 20 mM Na2HPO4-citric acid (pH 6.0–8.0); 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer(pH 7.5–9); and 20 mM glycine–NaOH buffer (pH 8.5–10.0). The optimal reaction temperature was evaluated at the optimal conditions and different temperatures (10–70 °C). The effects of potential inhibitors or activators on the enzymatic activity were determined by adding various metal ions and chemical agents to the reaction systems and incubating the sample at 30 °C for 60 min. Enzyme activity in the absence of any additive compounds was defined as 100%.

Chemical analysis

Samples were extracted as previously description [23]. HPLC (LC-20AD; Shimadzu, Japan) analyses were performed with a Kromasil 100-5C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm × 5 μm) using an injection volume of 20 μL. Acetonitrile/water (80:20, v/v, 0.8 mL/min) was used as the mobile phase, and the absorbance at 215 nm was measured with a SPD-20A wavelength absorbance detector. Metabolites were identified via GC–MS (Shimadzu QP2010 Plus) with a RTX-5MS column (15 m length × 0.25 mm id × 0.25 µm internal diameter) in split mode (1:20). The temperature program was as follows: 100 °C for 1.5 min, ramp at 50 °C/min to 260 °C (7 min hold), ramp at 50 °C/min to 300 °C (1 min hold). The detected mass range was from 70 m/z to 350 m/z. Helium (1.0 ml/min) was the carrier gas. For HPLC–MS/MS analysis, the samples were detected by an Triple-quadrupole LC–MS/MS system (Agilent 1260/6460, USA), which is equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) and operated in the positive polarity mode. Firstly, MS2-SCAN mode was used to detect the compounds in the peaks. Secondly, Product ion Scan mode was used to detect target compound with a scan range from 50 to 500 m/z. The mobile phase consisted of solvents A (ultrapure water, 20%) and B (acetonitrile, 80%) with a flow rate was 0.3 mL/min. The injection volume was 5 μL.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The GenBank accession numbers of the Rhodococcus sp. B2 16S rRNA gene, sequence of the gene cluster EthRABCDB2 and scaffold 51 are KM875453, KJ946935 and MW378985.

Results

Isolation, and identification of the pretilachlor-degrading strain B2

A pure bacterial culture with gram-positive and nonmotile cells was isolated and named B2. B2 Colonies were convex, opaque and red on LB agar after two days of cultivation. In addition, strain B2 tested positive for urease and catalase but negative for nitrate reduction, oxidase and starch hydrolysis. The 16S rRNA gene sequence showed that strain B2 had 100% similarity with strain R. erythropolis DSM43066T and 99.93% similarity with R. erythropolis NBRC100887T, forming a subclade with these two strains (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Therefore, strain B2 was preliminarily identified as Rhodococcus sp. basing on its characteristics.

Optimization of the cultivation conditions for pretilachlor-degradation

Three factors (pH, temperature, and inoculum size) with significant effects on microbial degradation were selected as the cultivation conditions to optimize using the CCD model. The data in Additional file 1: Table S3 were used in multiple regression analysis, and response variable Y can be obtained using the following quadratic polynomial model equation:

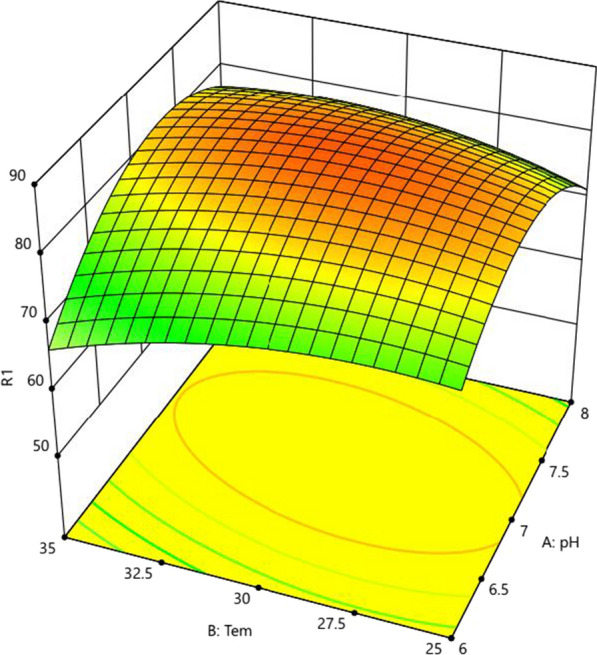

| 4 |

The ANOVA results for the quadratic response surface model are shown in Table 2. The regression model for pretilachlor degradation was statistically significant (P < 0.05) with R2 = 0.9501, and the results showed that A, C, AB, AC, A2, B2 significantly affected the pretilachlor degradation by strain B2. Thus, pH, inoculum size had significant effects on the degradation rate. Based on the P values of AB and AC (0.0075 and 0.037), the pH-temperature and inoculum size-pH interaction effects on the pretilachlor degradation were highly significant. Therefore, a response surface analysis was conducted to determine the impacts of the interaction between pH and temperature on pretilachlor-degradation by strain B2 (Fig. 1). These results revealed the maximum rate of pretilachlor degradation by strain B2 was 86.1% under the optimal conditions of pH 6.98, 30.1 °C, and inoculum size of 0.3 g/L.

Fig. 1.

Response surface plot for the interaction effect of pH and temperature on the biodegradation activity of strain B2

Kinetics of pretilachlor degradation by strain B2

The effect of the initial pretilachlor concentration on the degradation of pretilachlor was calculated via nonlinear least squares regression analysis using Origin 9.0pro and the results are shown in Fig. 2. The kinetic parameters were as follows: qmax = 3.28 days−1, KS = 53.51 mg/L, and Ki = 25.38 mg/L. The Sm was 36.84 mg/L, indicating that the theoretical efficiency of pretilachlor degradation was highest at this concentration, when the concentration of pretilachlor was more than 36.84 mg/L, the inhibition of strain B2 by the pretilachlor was obvious. This result may be attributed to the toxicity of pretilachlor to the assayed strain. The Andrews model was as follows:

Fig. 2.

Relationship between initial pretilachlor concentration and specific degradation rate by strain B2

Statistical regression results revealed the parameters of pretilachlor degradation kinetics (Additional file 1: Table S4). The resulting correlation coefficient R2 = 0.8285, indicates that the model was an excellent fit to the experimental data. The ability of strain B2 to degrade pretilachlor degradation increased at low pretilachlor concentrations, but decreases at higher pretilachlor concentrations. And this kinetic model is helpful for predicting the microbial bioremediation of pretilachlor by strain B2.

Identification of the metabolites resulting from pretilachlor degradation by strain B2

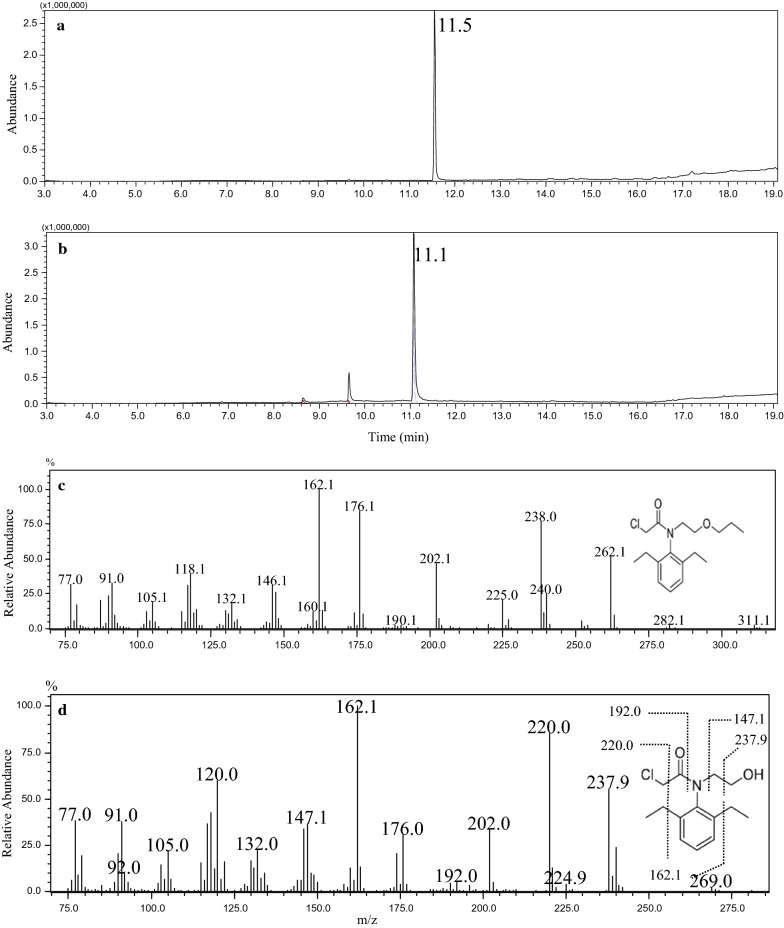

The products of pretilachlor degradation by strain B2 were detected by GC–MS. A compound from the control sample had the same RT as the pretilachlor standard (RT = 11.5 min, Fig. 3a). The molecular ion (M+) of peak (RT = 11.5 min) was 311 m/z with characteristic fragment ions mass spectral data showing a 96% match with pretilachlor in the NIST library (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

GC–MS profile of the metabolite produced during pretilachlor degradation by strain B2. a, b the GC spectra of the pretilachlor extract obtained from control sample and whole cell transformation of strain B2, respectively; c mass spectra for the peak at 11.5 min. d Mass spectra for the peak at 11.1 min

In addition, a new metabolite appeared at a retention time of 11.1 min (Fig. 3b). As we could not obtain the standard for the metabolite, and it was identified using GC–MS analyses. The M+ peak of this product was 269 m/z, and the characteristic fragment ions were 237.9 m/z (M+ − CH2OH), 220.0 m/z (M+ − CH2Cl), 202.0 m/z (M+ − CH3ClOH), 192.0 m/z (M+ − CH2COCl), 176.0 m/z (M+ − (CH2CH3)2Cl), 162.1 m/z (M+ − (CH2CH3)2CH2Cl), 147.1 m/z (M+ − CH2COCl(CH2)2OH) and 132.0 m/z (M+ − CH2COCl(CH2)2OHCH3), (Fig. 3d), These mass spectral data of the metabolite correspond to N-hydroxyethyl-2-chloro-N-(2,6-diethyl-phenyl)-acetamide which has not previously been reported during pretilachlor degradation, indicating it to be a novel product. In addition, LC–MS/MS analysis demonstrated the presence of pretilachlor and the metabolite N-hydroxyethyl-2-chloro-N-(2,6-diethyl-phenyl)-acetamide, results that are consistent with the corresponding GC–MS analysis (Additional file 1: Figure S9). However, the metabolite could not be further metabolized by strain B2. Therefore, pretilachlor degradation process by strain B2 involves O-dealkylation, representing a new mechanism of initial chloroacetamide herbicide degradation.

Screening of a mutant, TB2, defective in pretilachlor degradation

When grown on LB agar containing 100 mg/L pretilachlor, the colonies of strain B2 could produce a visible transparent halo, and N-hydroxyethyl-2-chloro-N-(2,6-diethyl-phenyl)-acetamide, which is more water-soluble than pretilachlor, was formed. In our present study, we observed that a few cells of strain B2 did not generate a transparent halo after continuous streaking on fresh LB agar plates, and one such isolate was named TB2. Resting cell transformation experiments revealed that TB2 could not metabolize pretilachlor (Additional file 1: Fig. S2), suggesting that the related gene responsible for O-dealkylation in pretilachlor degradation was deleted in the mutant TB2.

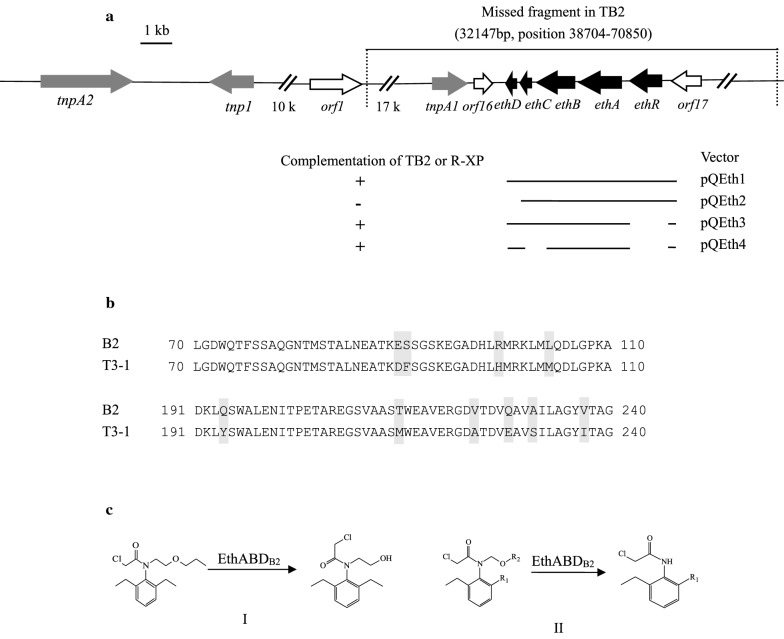

Genome comparison between strains B2 and TB2

The draft genomes of strains B2 and TB2 were sequenced with the Illumina MiSeq system and were shown to be 6,873,325 bp and 6,728,834 bp in length, respectively. Furthermore, a comparison of the genomes of strain B2 and TB2, resulted in the identification of a fragment from scaffold 51 of strain B2 that was absent in the genome of mutant TB2. The absence of this fragment was then verified by PCR. After which the flanking regions of scaffold 51 were confirmed by SEFA-PCR. Finally, a 115,851-bp fragment was acquired. And sequence comparison combined with PCR demonstrated that a 32,147-bp region of this fragment was absent in mutant TB2 (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Physical map of the putative transposable element containing EthRABCDB2 gene cluster in Rhodococcus sp. B2 and degradation pathway of chloroacetanilide herbicides. a Arrows indicate the sizes, locations, and directions of transcription of the ORFs. Complementation of the EthRABCDB2-disrupted mutants with different regions is illustrated below the physical map. b The difference of the amino acid sequences of EthB from strain B2 and T3-1. Highlighted characters represent the different residues. c Proposed degradation pathway of pretilachlor, alachlor, acetochlor, propisochlor and butachlor by EthABDB2. I, pretilachlor. II, Alachlor, R1 = CH3CH2-, R2 = CH3-; Acetochlor, R1 = CH3-, R2 = CH3CH2-; Butachlor, R1 = CH3CH2-, R2 = CH3CH2CH2CH2-: Propisochlor, R1 = CH3-,R2 = (CH3)2CH-.Strain B2 cannot further metabolize three metabolites

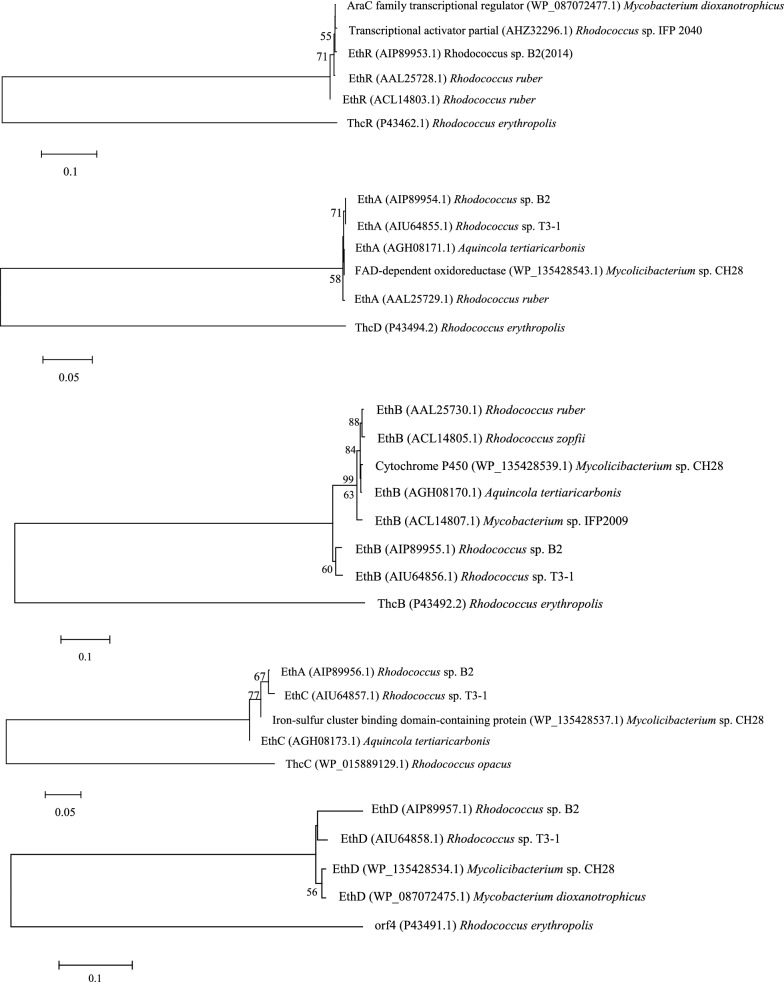

ORF analysis of the fragment absent in strain TB2

A gene cluster consisting of five genes, EthRB2, EthAB2, EthBB2, EthCB2 and EthDB2, was identified by an analysis of all ORFs, and the encoded amino acid sequence of the genes in the missing fragment were identified in NCBI (Additional file 1: Table S6). EthRB2, encoding the AraC/XylS family regulator (37 kDa), shares the highest similarity with the EthR from Rhodococcus sp. T3-1 (100%). EthAB2, encoding a ferredoxin reductase (43 kDa), shares the highest similarity with EthA from Rhodococcus sp. T3-1 (100%). EthBB2, encoding a cytochrome P450 oxidase (44 kDa), shares the highest similarity with EthB from Rhodococcus sp. T3-1 (97.5%). EthCB2, encoding a 2Fe-2S ferredoxin (11 kDa), shares the highest similarity with EthC from Mycobacterium sp. CH28 (99.06%). EthDB2, encoding a protein of unknown function (10 kDa), shares the highest similarity with EthD from Mycobacterium sp. CH28 (90.29%) (Fig. 5). The gene EthB was termed EthBB2 (EthB from strain B2), and its inferred amino acid sequence was aligned to that of EthBT3-1 from Rhodococcus sp. strain T3-1, as shown in Fig. 4b. Ten amino acid differences were observed between the two proteins, which may confer different physical properties to EthBB2. The high similarity of the two proteins indicated the occurrence of horizontal gene transfer event (Fig. 4a). The upstream eth gene cluster contains two gene fragments (tnpA1, and tnpA2) encoding the proteins displaying > 99% sequence identity with the Tn3 family transposase (TnpA) and one fragment (tnp1) belonging to the IS30 family transposase (Additional file 1: Table S6). However, a transposase was not identified downstream of the eth gene cluster. In contrast, two transposons, IS3-type class II, flanked the EthRABCD gene cluster of R. ruber IFP 2001 [37].

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree of EthRABCDB2 and related proteins constructed by the neighbor-joining method. The branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 50% of bootstrap replicates are collapsed. Name of the strains, proteins and their GenBank numbers are displayed in the phylogenetic tree. Thc gene cluster was used as an out-group The scale bar indicates amino acid residue substitutions per amino acid

Functionally complementation of the Eth gene cluster in strain TB2

To determine the function of the gene cluster EthRABCDB2, the recombinant plasmid pQeth1 containing EthRABCDB2 was introduced into strain E. coli DH5α and strain TB2. The recombinant strain TB2 (pQeth1) acquired the ability to degrade pretilachlor and generate a visible transparent halo in LB agar supplemented with 100 mg/L pretilachlor, which was similar to that observed for strain B2. HPLC results showed that TB2 (pQeth1) could degrade pretilachlor, and exhibited the O-dealkylation activity (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). A similar phenomenon was found in strain Rhodococcus sp. R-XP(pQeth1). However, E. coli DH5α(pQeth1 or pQeth2) and strain TB2(pQeth2) failed to degrade pretilachlor, indicating that EthRABCDB2 was expressed at a low level or the original promoter could not promote transcription of the cluster in E. coli, and EthDB2 was essential for degradation. In order to verify the above hypothesis, the EthABCDB2 and EthABCB2 fragments under the control of the T7 promoter in vector pET-29a(+) were introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3). Whole-cell transformation assay results showed that the IPTG-induced suspension of E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring EthABCD (but not EthABC) was able to degrade pretilachlor, although with low activity (data not shown), These results indicated that EthRB2, EthCB2 gene are not essential and that the original promoter is important for the Eth gene cluster. Therefore, EthABCDB2 and EthABDB2 were reconstituted with original promoters to analyze the degradation of chloroacetanilide herbicides. The HPLC results showed that strain TB2 (pQeth3, and pQeth4) could convert pretilachlor, butachlor, alachlor, acetochlor and propisochlor to the corresponding metabolites, indicating that EthDB2 was likely a ferredoxin gene.

Expression of the gene cluster EthABCDB2 and reconstitution of the chloroacetanilide herbicide degradation enzyme in vitro

The components EthAB2, EthBB2, EthCB2 and EthDB2 were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS separately, and each recombinant protein was purified using Ni-affinity chromatography. The Mw value of the four proteins were consistent with the theoretically calculated values (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). Purified EthCB2-His6 and EthDB2-His6, were mixed with EthAB2-His6 and EthBB2-His6 in vitro. The results showed that the EthABDB2-His6 and EthABCDB2-His6 (not EthABCB2-His6) mixture showed pretilachlor-degrading activity indicating that EthDB2 is a ferredoxin. The catalytic activity of EthABDB2 toward pretilachlor was 3.41 ± 0.4 μmol/min/mg. EthABDB2 performed N-dealkoxymethylation to acetochlor, alachlor, propisochlor and butachlor, O-dealkylation to pretilachlor, but it was unable to degrade metolachlor. The GC–MS results showed that strain EthABDB2 could convert butachlor, alachlor, acetochlor and propisochlor to the corresponding metabolites CDEPA (for butachlor and alachlor) or CMEPA (for propisochlor and acetochlor) (Additional file 1: Fig. S4–S7). These metabolites are generated from C–N bond cleavage by N-dealkoxymethylation, and based on the comparison of the chemical structures of chloroacetanilide herbicides, the number of C-atoms between the N and O in the side chain affects the degradation. According to these results, the mechanism of pretilachlor degradation (O-dealkylation) was different from that of the other four chloroacetanilide herbicides (N-dealkylation), and the degradation pathway of chloroacetanilide herbicides by EthABDB2 was proposed (Fig. 4c). The recombinant strain TB2 (pQeth4) could not degrade metolachlor, suggesting that steric hindrance blocks enzyme–substrate interactions. EthBB2, a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase of the multicomponent system, plays a key role in chloroacetanilide herbicide degradation, and EthABDB2 from strain B2 has a broader substrate spectrum than that of the corresponding enzymes from strain T3-1. Thus, EthABDB2 is a better enzyme for practical bioremediation of chloroacetanilide herbicides.

Characteristics of EthABDB2

The effects of different environmental factors on the enzymatic activity of EthABDB2 were determined (Additional file 1: Fig. S8). The enzyme activity was assessed at 10–65 °C, and was shown to function optimally at 30 °C (Additional file 1: Fig. S8B). In addition, EthABDB2 showed the enzyme showed high activity at pH 7.0–8.5, with an optimum pH of 7.5 in Tris–HCl buffer (Additional file 1: Fig. S8A), and decreased activity was lost observed at pH values below 4.0 or above 10.0. Metal ions play an important role in the enzyme activity. As shown in Additional file 1: Table S5, Fe2+ and Mg2+ could strongly enhance EthABDB2 activity, while Ca2+ could also slightly increase enzyme activity. However, the divalent cations Ba2+, Co2+ and Zn2+ slightly decreased enzyme activity, while Ag+, Cu2+, Hg2+, Ni2+ Cr2+ and Mn2+ significantly inhibited its enzyme activity. Chemical agents EDTA severely inhibited the enzyme activity, indicating that metal ions are required for its enzymatic reaction.

Discussion

Glutathione S-transferase and cytochrome P450 play an important function in the detoxification of chloroacetanilide herbicides in plants and mammals [38, 39]. In microorganisms, CndABC, a monooxygenase system belonging to RHO family of N-dealkylase capable of catalyzing the N-dealkylation of butachlor, acetochlor and alachlor, was cloned from strains DC-2 and DC-6 [18]. EthBADT3-1 from Rhodococcus sp. T3-1, expressed in E. coli, was previously shown to exhibit N-deethoxymethylase activity against acetochlor, but not pretilachlor and metolachlor [19, 22]. At present, we identified and characterized the function of the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system EthABDB2 which was cloned from strain B2. EthABDB2, which exhibit a ten amino acids difference with the EthBADT3-1 system, demonstrated the ability to catalyze the O-dealkylation or N-dealkoxymethylation of the chloroacetanilide herbicides pretilachlor, propisochlor, alachlor, acetochlor and butachlor. The different functions of the two proteins indicate that the key amino acid mutant broadens the substrate spectrum of this enzyme, indicting that the mutants of this protein could be attempted to degrade metolachlor in further research.

EthRABCD was first identified in the fuel oxygenate-degrading strain R. ruber IFP 2001 and exhibit O-dealkylation activity toward tert-amyl methyl ether (TAME), ethyl tert-butyl ether(ETBE) and methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) [37]. The Eth system, which is also present in gram-negative strain Aquincola tertiaricarbonis L108, with the exception of EthR, enables the efficient metabolization of MTBE, diethyl ether, TAME, ETBE, diisopropyl ether and tert-amyl ethyl ether(TAEE). However, this Eth monooxygenase system can not catalyze the degradtion of the synthetic ethers, including phenetole, and isopropoxybenzene, inferring that the nonreacting side chain link with the ether molecules may not exceed the size of the tert-amyl group [40]. In the present study, we enriched the function of Eth system in dealkylating O atom or dealkoxymethylating of N atom in synthetic compounds with larger residues, including pretilachlor, acetochlor, propisochlor, and butachlor.

The cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system EthRABCDB2 of Rhodococcus sp. B2 suffers from transposon-mediated recombination, resulting in eth loss mutants, e.g., Rhodococcus sp. TB2, which are unable to degrade pretilachlor. The deletion mechanism was shown to be similar to that observed in R. ruber IFP 2001 (IS3-type transposon element) but different from that from A. tertiaricarbonis L108 (rolling-circle IS91 type). The sequence similarity of the gene cluster EthRABCDB2 in the reported bacterial strains was > 90%, indicating that the Eth gene cluster EthRABCDB2 was horizontally transferred and that the transposons were likely the reason for its high mobility. Transposons in strains are rapidly adapted toward environmental transitions, such as substrate changes. This phenomenon is also true of enzymes required for the degradation of man-made xenobiotics, such as chloroacetanilide herbicides which have been applied globally for less than one hundred years [41]. The Eth gene cluster has been discovered in gram-positive strains, such as R. ruber IFP 2001 and Rhodococcus sp. T3-1 as well as gram-negative strains, such as A. tertiaricarbonis L108, suggesting that this gene cluster is highly conserved and has a complex transfer history.

EthABCD and EthABD, but not EthABC, showed activity against chloroacetanilide herbicides. A similar phenomenon was found in Rhodococcus sp. T3-1, indicating that EthD is a ferredoxin. EthC was predicted to be a ferredoxin, and we inferred that the EthABC system could potentially degrade other compounds. Interestingly, neither chloroacetanilide herbicides nor fuel oxygenates could be shown to serve as the natural inducers of the Eth system. The natural substrates should harbor O-alkyl or N-alkyl groups and be consistently present in the environment. The identification of this novel function of the Eth gene cluster can be exploited for the biodegradation of soil contaminated by gasoline ethers and chloroacetanilide herbicides.

Conclusions

In the present study, a strain named Rhodococcus sp. B2 was isolated from a herbicide-contaminated field, and the optimum conditions (culture time, 5 days; initial substrate concentration, 50 mg/L; pH, 6.98; temperature, 30.1 °C) for efficient pretilachlor degradation (86.1%) were determined via response surface methodology. A novel product was detected during the pretilachlor biodegradation and identified. An DNA fragment absent from the mutant strain TB2 containing the functional gene cluster (called EthRABCDB2, first reported to be responsible for the O-dealkylation of the fuel oxygenate chemicals) was identified by genome comparison to strain B2. The recombinant enzyme EthABDB2 could degrade chloroacetanilide herbicides and catalyze the N-dealkoxymethylation of alachlor, acetochlor, butachlor and propisochlor and the O-dealkylation of pretilachlor. The broad substrate spectrum of EthABDB2 indicate the potential for bioremediation of environments contaminated by gasoline ethers and chloroacetanilide herbicides.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Table S1 Strains and plasmids used in this study; Table S2 PCR primers used in this study. Table S3 Data of central composite design; Table S4 The statistical regression results of pretilachlor degradation kinetics; Table S5. Effect of metal ions and EDTA on EthABDB2 enzyme activity; Table S6 Deduced function of each ORF of scaffold 51 sequence containing the missing fragment; Fig. S1 Phylogenetic tree constructed by the neighbour-joining method based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences; Fig. S2 HPLC analysis of pretilachlor degradation by strain TB2 and TB2(pQEth1); Fig. S3 SDS-PAGE(12%) analysis of the purified His6-tagged EthA, EthB, EthC and EthD; Fig. S4 GC/MS analysis of the transformation of alachlor by the EthABDB2; Fig. S5. GC/MS analysis of the transformation of acetochlor by the EthABDB2; Fig. S6 GC/MS analysis of the transformation of propisochlor by the EthABDB2; Fig. S7 GC/MS analysis of the transformation of butachlor by EthABDB2; Fig. S8 effects of pH (A) and temperature (B) on EthABDB2 activity; Fig. S9 HPLC-MS/MS analysis of the pretilachlor and the intermediate metabolites catalyzed by the strain B2.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31700097, 31800109), the Key Laboratory of Biomedicine in Gene Diseases and Health of Anhui Higher Education Institutes, Foundation for Distinguished Young Talents in Higher Education of Anhui, Provincial Key Laboratory of Biotic Environment and Ecological Safety in Anhui.

Authors' contributions

HL and LS conceived and designed the experiments. HL, ML, AL, LS and LR performed the experiments and analyzed the data. HL and GZ wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All materials described within this manuscript, and engineered strains are available on request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our manuscript does not report data collected from humans or animals.

Consent for publication

Our manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data in any form.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guo-ping Zhu, Email: gpz1996@yahoo.com.

Li-na Sun, Email: slna@163.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12934-021-01544-z.

References

- 1.Cai X, Sheng G, Liu W. Degradation and detoxification of acetochlor in soils treated by organic and thiosulfate amendments. Chemosphere. 2007;66:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun Y, Zhao L, Li X, Hao Y, Xu H, Weng L, Li Y. Stimulation of earthworms (Eisenia fetida) on soil microbial communities to promote metolachlor degradation. Environ Pollut. 2019;248:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiang H-C, Duh J-R, Wang Y-S. Butachlor, thiobencarb, and chlomethoxyfen movement in subtropical soils. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2001;66:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s001280000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coupe RH, Blomquist JD. Water-soluble pesticides in finished water of community water supplies. J Am Water Works Assoc. 2004;96:56–68. doi: 10.1002/j.1551-8833.2004.tb10723.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rebich R, Coupe R, Thurman E. Herbicide concentrations in the Mississippi River Basin—the importance of chloroacetanilide herbicide degradates. Sci Total Environ. 2004;321:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Squillace PJ, Scott JC, Moran MJ, Nolan B, Kolpin DW. VOCs, pesticides, nitrate, and their mixtures in groundwater used for drinking water in the United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36:1923–1930. doi: 10.1021/es015591n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerry D, Nancy M, Alberto P. A survey of EPA/OPP and open literature on selected pesticide chemicals: II Mutagenicity and carcinogenicity of selected chloroacetanilides and related compounds. Mutat Res Genetic Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 1999;5:8. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao N, Jing B, Ge F, Liu X. The fate of herbicide acetochlor and its toxicity to Eisenia fetida under laboratory conditions. Chemosphere. 2006;62:1366–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei J, Feng Y, Sun X, Liu J, Zhu L. Effectiveness and pathways of electrochemical degradation of pretilachlor herbicides. J Hazard Mater. 2011;189:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamogami S, Kodama O, Hirose K, Akatsuka T. Pretilachlor [2-chloro-N-(2, 6-diethylphenyl)-N-(2-propoxyethyl) acetamide]-and butachlor [N-(butoxymethyl)-2-chloro-N-(2, 6-diethylphenyl) acetamide]-induced accumulation of phytoalexin in rice (Oryza sativa) plants. J Agric Food Chem. 1995;43:1695–1697. doi: 10.1021/jf00054a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh DP, Khattar JS, Alka GK, Singh Y. Toxicological effect of pretilachlor on some physiological processes of cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PUPCCC 64. J Appl Biol Biotechnol. 2016;4:012–019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang J, Chen Y, Yu R, Zhao X, Wang Q, Cai L. Pretilachlor has the potential to induce endocrine disruption, oxidative stress, apoptosis and immunotoxicity during zebrafish embryo development. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;42:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hisato MI. Effects of the agrochemicals butachlor, pretilachlor and isoprothiolane on rat liver xenobioticmetabolizing enzymes. Xenobiotica. 1998;28:1029–1039. doi: 10.1080/004982598238921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pal R, Das P, Chakrabarti K, Chakraborty A, Chowdhury A. Butachlor degradation in tropical soils: Effect of application rate, biotic-abiotic interactions and soil conditions. J Environ Sci Health B. 2006;41:1103–1113. doi: 10.1080/03601230600851141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y-S, Liu J-C, Chen W-C, Yen J-H. Characterization of acetanilide herbicides degrading bacteria isolated from tea garden soil. Microb Ecol. 2008;55:435–443. doi: 10.1007/s00248-007-9289-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng P, Wilson A, McClanahan R, Patanella J, Wratten S. Metabolism of alachlor by rat and mouse liver and nasal turbinate tissues. Drug Metab Dispos. 1990;18:373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Field JA, Thurman E. Glutathione conjugation and contaminant transformation. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:1413–1418. doi: 10.1021/es950287d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Q, Wang C-H, Deng S-K, Wu Y-D, Li Y, Yao L, Jiang J-D, Yan X, He J, Li S-P. A novel three-component Rieske non-heme iron oxygenase (RHO) system catalyzing the N-dealkylation of chloroacetanilide herbicides in sphingomonads DC-6 and DC-2. Appl Environ Microbioy. 2014 doi: 10.1128/AEM.00659-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang F, Zhou J, Li Z, Dong W, Hou Y, Huang Y, Cui Z. Cytochrome P450 System EthBAD involved in the N-deethoxymethylation of Acetochlor by Rhodococcus sp T3–1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;8:03764–3714. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03764-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barry SM, Challis GL. Mechanism and Catalytic Diversity of Rieske Non-Heme Iron-Dependent Oxygenases. ACS catalysis. 2013;3:2362–2370. doi: 10.1021/cs400087p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denisov IG, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Schlichting I. Structure and chemistry of cytochrome P450. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2253–2278. doi: 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hou Y, Dong W, Wang F, Li J, Shen W, Li Y, Cui Z. Degradation of acetochlor by a bacterial consortium of Rhodococcus sp T3–1, Delftia sp. T3–6 and Sphingobium sp. MEA 3–1. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2014;59:35–42. doi: 10.1111/lam.12242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu H-M, Cao L, Lu P, Ni H, Li Y-X, Yan X, Hong Q, Li S-P. Biodegradation of butachlor by Rhodococcus sp strain B1 and purification of its hydrolase (ChlH) responsible for N-dealkylation of chloroacetamide herbicides. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:12238–12244. doi: 10.1021/jf303936j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Hu Q, Liu B, Li F, Jiang J-D. Characterization of a Linuron-Specific Amidohydrolase from the Newly Isolated Bacterium Sphingobium sp Strain SMB. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;2:8. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c00597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieg NR, Sneath P, Staley JT, Williams ST. Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;15:408. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sudhir K, Glen S, Koichiro T. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 70 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;7:6. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acuña-Argüelles M, Olguin-Lora P, Razo-Flores E. Toxicity and kinetic parameters of the aerobic biodegradation of the phenol and alkylphenols by a mixed culture. Biotech Lett. 2003;25:559–564. doi: 10.1023/A:1022898321664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Russell D, Russell D. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Cold Spring Harbor; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, He J, Cui Z, Li S. Self-formed adaptor PCR: a simple and efficient method for chromosome walking. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5048–5051. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02973-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown N, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van der Geize R, Hessels G, Van Gerwen R, Van der Meijden P, Dijkhuizen L. Molecular and functional characterization of kshA and kshB, encoding two components of 3-ketosteroid 9alpha-hydroxylase, a class IA monooxygenase, in Rhodococcus erythropolis strain SQ1. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1007–1018. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van der Geize R, Hessels G, Van Gerwen R, Vrijbloed J, van Der Meijden P, Dijkhuizen L. Targeted Disruption of the kstD Gene Encoding a 3-Ketosteroid Δ1-Dehydrogenase Isoenzyme of Rhodococcus erythropolis Strain SQ1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2029–2036. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.5.2029-2036.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu H, Wang S-J, Zhang J-J, Dai H, Tang H, Zhou N-Y. Patchwork assembly of nag-like nitroarene dioxygenase genes and the 3-chlorocatechol degradation cluster for evolution of the 2-chloronitrobenzene catabolism pathway in Pseudomonas stutzeri ZWLR2-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:4547–4552. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02543-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hussain HA, Ward JM. Enhanced heterologous expression of two Streptomyces griseolus cytochrome P450s and Streptomyces coelicolor ferredoxin reductase as potentially efficient hydroxylation catalysts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:373–382. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.373-382.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chauvaux S, Chevalier F, Le Dantec C, Fayolle F, Miras I, Kunst F, Beguin P. Cloning of a genetically unstable cytochrome P-450 gene cluster involved in degradation of the pollutant ethyltert-butyl ether by Rhodococcus ruber. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6551–6557. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6551-6557.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siminszky B. Plant cytochrome P450-mediated herbicide metabolism. Phytochem Rev. 2006;5:445–458. doi: 10.1007/s11101-006-9011-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coleman S, Linderman R, Hodgson E, Rose RL. Comparative metabolism of chloroacetamide herbicides and selected metabolites in human and rat liver microsomes. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:1151. doi: 10.1289/ehp.001081151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuster J, Purswani J, Breuer U, Pozo C, Harms H, Mï RH, Rohwerder T. Constitutive expression of the cytochrome P450 EthABCD monooxygenase system enables degradation of synthetic dialkyl ethers in Aquincola tertiaricarbonis L108. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:2321–2327. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03348-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Springael D, Top EM. Horizontal gene transfer and microbial adaptation to xenobiotics: new types of mobile genetic elements and lessons from ecological studies. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Table S1 Strains and plasmids used in this study; Table S2 PCR primers used in this study. Table S3 Data of central composite design; Table S4 The statistical regression results of pretilachlor degradation kinetics; Table S5. Effect of metal ions and EDTA on EthABDB2 enzyme activity; Table S6 Deduced function of each ORF of scaffold 51 sequence containing the missing fragment; Fig. S1 Phylogenetic tree constructed by the neighbour-joining method based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences; Fig. S2 HPLC analysis of pretilachlor degradation by strain TB2 and TB2(pQEth1); Fig. S3 SDS-PAGE(12%) analysis of the purified His6-tagged EthA, EthB, EthC and EthD; Fig. S4 GC/MS analysis of the transformation of alachlor by the EthABDB2; Fig. S5. GC/MS analysis of the transformation of acetochlor by the EthABDB2; Fig. S6 GC/MS analysis of the transformation of propisochlor by the EthABDB2; Fig. S7 GC/MS analysis of the transformation of butachlor by EthABDB2; Fig. S8 effects of pH (A) and temperature (B) on EthABDB2 activity; Fig. S9 HPLC-MS/MS analysis of the pretilachlor and the intermediate metabolites catalyzed by the strain B2.

Data Availability Statement

All materials described within this manuscript, and engineered strains are available on request.