Abstract

T cell receptor (TCR)-engineered T cell therapy is a promising cancer treatment approach. Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) is overexpressed in the majority of tumors and a potential target for adoptive cell therapy. We isolated a novel hTERT-specific TCR sequence, named Radium-4, from a clinically responding pancreatic cancer patient vaccinated with a long hTERT peptide. Radium-4 TCR-redirected primary CD4+ and CD8+ T cells demonstrated in vitro efficacy, producing inflammatory cytokines and killing hTERT+ melanoma cells in both 2D and 3D settings, as well as malignant, patient-derived ascites cells. Importantly, T cells expressing Radium-4 TCR displayed no toxicity against bone marrow stem cells or mature hematopoietic cells. Notably, Radium-4 TCR+ T cells also significantly reduced tumor growth and improved survival in a xenograft mouse model. Since hTERT is a universal cancer antigen, and the very frequently expressed HLA class II molecules presenting the hTERT peptide to this TCR provide a very high (>75%) population coverage, this TCR represents an attractive candidate for immunotherapy of solid tumors.

Keywords: T cell receptor, MHC class II, in vivo model, solid tumor, immunotherapy, telomerase, CD4 T cell

Graphical Abstract

CD4 T cells are major players in the antitumor response. Dillard et al. target a universal cancer antigen, telomerase, with a TCR recognizing its presentation on a frequently expressed HLA class II allele. Such TCR-redirected T cells provide both helper and direct cytotoxic functions and destroy telomerase-expressing tumors in vitro and in vivo, thus offering an alternative solution for solid tumor treatment.

Introduction

Adoptive Cellular Therapy (ACT) using genetically modified T cells has rapidly gained credit as an approach to cancer treatment. T cell-based ACT relies on guiding effector cells to the cancer through the introduction of specific receptors, either a T cell receptor (TCR) or a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). Currently, the most advanced therapeutic receptors target the B cell antigen marker cluster of differentiation (CD)19 and have been used successfully in the treatment of B cell malignancies.1,2 Although effective, CAR recognition is restricted to surface molecules, which represent a limitation of cancer-specific targets and increase the risk of recognition of healthy tissues. On the other hand, TCRs recognize peptides in complex with the major histocompatibility complex (MHC or human leukocyte antigen [HLA]) and can potentially detect any peptides generated in a cell, since all proteins are degraded and presented on the MHC. This substantially expands the number of targets and allows for optimal matching of the TCR specificity to tumor antigens.3 Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) is an attractive tumor-associated antigen (TAA), since it is constitutively overexpressed in the majority of human cancers. Reactivation of telomerase in cancer cells allows for unlimited cellular proliferation and immortality by preventing chromosome attrition.4 hTERT expression has been demonstrated in >90% of cancer cells5, 6, 7, 8 and is critical for epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis.9 Additionally, hTERT reactivation is considered to be essential for cancer stem cells, which are thought to be pivotal for cancer relapse and treatment resistance.10,11 Importantly, transfer of therapeutic TCRs to T cells of MHC-compatible patients with a solid tumor has demonstrated clinical responses in recent trials.12,13

A major issue in the development of a therapeutic TCR is the origin of the molecule. High-affinity TCRs have been generated by directed evolution or using transgenic mice,14,15 but clinical studies have shown that when enhanced TCRs are used in patients, they can lead to fatal outcomes, mainly due to their unpredicted recognition of additional targets.15,16 The focus of our group and other labs has been on tumor-specific T cell populations identified in patients responding to cancer vaccinations.17, 18, 19 We consider these TCRs to be safer, since they have not been modified and have already passed selection in a thymus.

Here, we report the isolation and preclinical efficacy and safety validation of a T helper cell type 1 (Th1) cell-derived TCR, Radium-4. This TCR recognizes the central, enzymatic component of telomerase hTERT in the context of HLA-DP04 and HLA-DP03, frequent MHC class II alleles expressed in about 76% of the white population20 and important worldwide.21,22 Notably, we selected the Radium-4 TCR because the original T cell clone also had demonstrated reactivity against autologous ascites cells and thus, a strong sensitivity to endogenous antigen levels,23 in contrast to the previously reported enhanced hTERT-specific TCRs.24,25 This direct recognition suggests that the hTERT epitope is processed and loaded onto MHC, which is infrequent for MHC class II peptides but attractive in terms of targeting as many solid tumors that also express MHC class II.26,27 We demonstrated here how Radium-4 TCR was efficiently expressed in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and functional upon specific stimulation, suggesting that although not enhanced, this TCR showed natural high affinity. The high affinity was confirmed by recognition of endogenous hTERT levels by Radium-4 TCR and lysis of melanoma cell lines grown as 2D cultures and as spheroids. We then engrafted non-obese diabetic (NOD).Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice with tumor cells and found that treatment with Radium-4 TCR could both significantly reduce their growth and enhance survival. This is encouraging given that this model is unable to capture the full functional capacity of Th1 cells due to lack of relevant antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and a full human T cell repertoire. In summary, we demonstrated the effectiveness of this MHC class II-restricted TCR in ACT. Furthermore, Radium-4 TCR, targeting a widely expressed tumor antigen and with a broad population coverage, is a strong candidate for clinical use and further validates our strategy of isolating TCRs from clinically responding patients in cancer vaccine trials for the development of TCR-based cancer immunotherapy.28

Results

Isolation and Expression of Radium-4 TCR

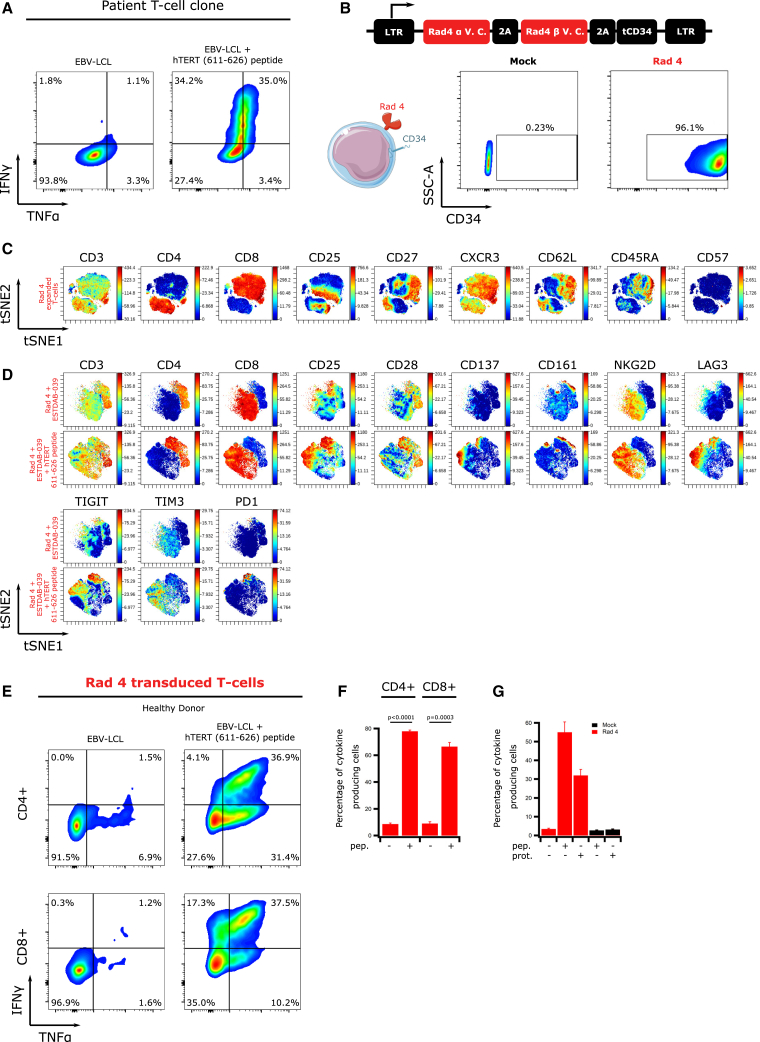

Radium-4 TCR was identified from the peripheral blood of a pancreatic cancer patient showing a strong vaccine response and long-term survival following therapy.23 Previously isolated CD4+ T cell clones with high reactivity against the hTERT peptide 611–626 produced inflammatory cytokines after coincubation with peptide-loaded HLA-DP04+ cells (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Radium-4 TCR Is Efficiently Expressed, Functional, and Specific

(A) Intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α production in the CD4+ patient T cell clone cocultured with HLA-DP04+ EBV-LCL, loaded or not with hTERT 611–626 peptide. Representative flow diagram from two independent experiments. (B) Schematic representation of the retroviral construct used for the transduction of Radium-4 TCR in primary T cells. Expression of Radium-4 TCR in primary T cells after retroviral transduction (leftpanels: mock transduced; right panels: TCR transduced) detected by flow cytometry using an anti-CD34 antibody. Data shown are representative flow diagrams from three independent experiments. (C) viSNE representation of phenotypic markers of expanded and transduced Radium-4 TCR T cells. (D) viSNE representation of the expression of extracellular activation markers and immune-checkpoint molecules of Radium-4 TCR T cells upon coincubation with ESTDAB-039 cells, preloaded or not with hTERT 611–626 peptide. (E) Intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α production in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells retrovirally transduced with Radium-4 TCR and cocultured with EBV-LCL, loaded or not with hTERT 611–626 peptide. Representative flow diagram from three independent experiments. (F) Summary of intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α production shown in (C). Bars represent mean ± SD. Statistical validation was realized between conditions in THE presence and absence of peptide. (G) Percentage of cytokine-producing Radium-4 TCR mRNA-electroporated T cells upon coculture with nonloaded APCs or loaded with hTERT 611–626 peptide or hTERT protein. Bars represent mean ± SD of quadruplicates.

We designed a Radium-4 construct where TCR alpha and beta chains were connected with a 2A ribosome-skipping sequence, as previously reported (Figure S1A, top)29 and first confirmed the TCR expression upon mRNA electroporation of the TCR-negative cell line, J76 (Figure S1A, bottom). To facilitate the detection of Radium-4 TCR in primary T cells, we included a CD34 tag via a second 2A sequence at the end of the TCR coding sequence30 and confirmed the expression of the molecules in J76 (Figure 1B, top). Then, primary healthy donor T cells were transduced and shown to express high levels of the construct (Figures 1B and S1B). Importantly, we attempted to generate a peptide-MHC (pMHC) multimer in order to detect the TCR in primary T cells; however, only a weak, unstable signal could be detected upon TCR expression in primary T cells (data not shown). This has also been reported for other TCRs that are still fully functional and is especially challenging for MHC class II-restricted TCRs.31 These data showed that Radium-4 TCR could be efficiently produced using different expression systems.

Phenotypic Description of Radium-4 TCR T Cells

To assess the phenotype and homogeneity of the retrovirally transduced T cells after expansion, we performed CyTOF experiments and subsequent analysis and visualization of high-dimensional single-cell data using the viSNE algorithm. These revealed that expanded Radium-4 TCR T cells were composed of 20% naive cells (CD45RA+, CD62L+, CD27+, CD57−), 20% effector memory cells (CD45RA−, CD62L+, CD27+, CD28+, CD57−), and 60% effector cells (CD62L−, CD45RA−, CD57−) (Figures 1C and S2A). Similar T cell phenotypes were already described after expansion with CD3/CD28 Dynabeads.32 Furthermore, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations were reproducibly transduced with both Radium-4 TCR and a control TCR, Radium-6 (see below; Figure S4).

Recognition of Processed Cognate Peptide by Radium-4 TCR Triggers Cytokine Secretion

We next tested the activity of Radium-4 TCR in primary T cells by assessing changes in the expression of activation markers upon coincubation with the HLA-DP04+ melanoma cell line ESTDAB-039, preloaded or not with the hTERT 611–626 peptide. As revealed by CyTOF analysis, upon encounter with a cognate target, Radium-4 TCR T cells upregulated activation markers (CD25, CD137, CD161, and NKG2D) and immune checkpoint markers (LAG3 [lymphocyte-activation gene 3], TIGIT [T cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domains], TIM3 [T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3], and PD1 [programmed cell death protein 1]) (Figures 1D, top, and S2B). Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) production of redirected T cells were assessed upon incubation with target cells; HLA-DP04+ Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (EBV-LCLs), previously loaded or not with hTERT 611–626 peptide. Intracellular cytokine staining showed that Radium-4 TCR T cells exhibited a Th1/Tc1 profile. As shown, both redirected CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were able to recognize the cognate antigen and secrete cytokines (Figures 1E and 1F), suggesting that Radium-4 TCR could operate in a coreceptor-independent manner. We confirmed these results in a transient system where TCR mRNA was electroporated into T cells (Figure S3A). Additionally, we observed that Radium-4 TCR was highly sensitive to low peptide concentration, as shown by a saturation model fitting for the percentage of cytokine-producing cells with a half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of 0.1 μM peptide (Figure S3B).33,34 Since Radium-4 is a CD4+ T cell-derived TCR, we needed to evaluate that the cognate peptide was naturally processed and presented by MHC class II-positive cells upon exogenous loading. We therefore tested Radium-4 mRNA-electroporated T cell activation against either peptide- or protein-loaded target cells (Figure 1G). These experiments were repeated side by side with the original T cell clone,23 which demonstrated similar dynamics (Figure S3C). From these data, we concluded that Radium-4 TCR was not only potent in redirected T cells in two expression formats but was also sensitive to the naturally processed hTERT epitope.

Radium-4 TCR Promotes Antigen-Specific Tumor Cell Killing

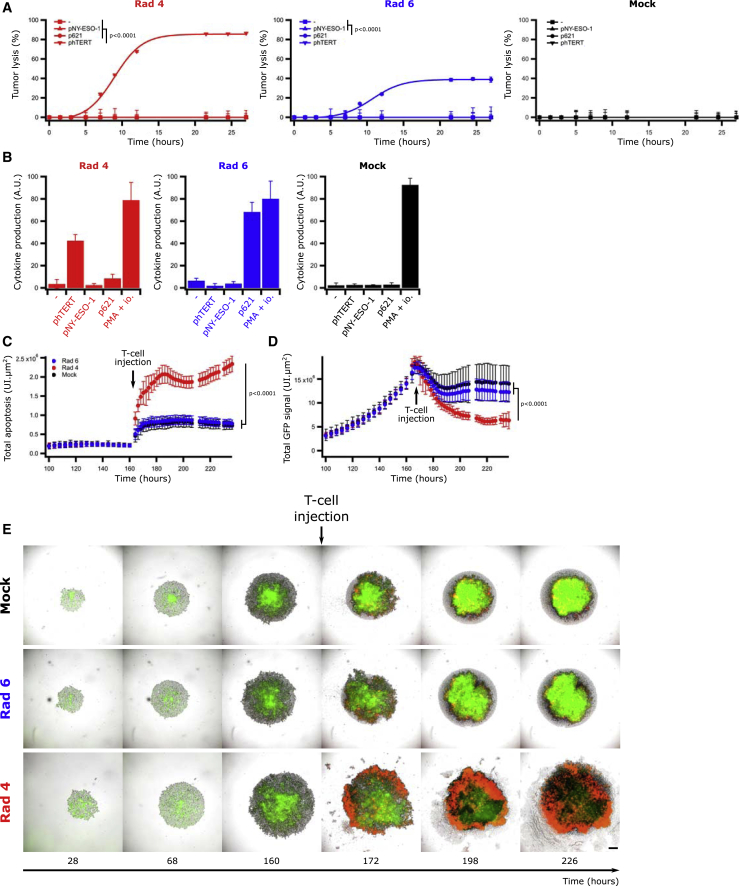

The cytotoxic capacity of CD4+ T cells has previously been demonstrated, both against viral antigens and in cancer.35,36 We therefore tested if Radium-4 TCR expression could confer cytotoxic capacity to transduced T cells upon coculture with EBV-LCLs carrying the particular HLA molecules presenting the target (Figure 2A). In this experiment, we included an alternative MHC class II-restricted TCR (Radium-6), specific for the transforming growth factor-β receptor II (TGF-βRII) frameshift mutated 127–145 peptide (p621) presented on HLA-DR04 T cells as a control TCR37 (Figure S4). T cells modified to express Radium-4 and Radium-6 TCRs were confirmed to kill (Figures 2A and S5A) and produce (Figures 2B and S5B–S5D) cytokines in a pMHC-specific manner. This was further supported by the use of a negative control, where the two TCRs were tested against their cognate peptides and a long peptide derived from NY-ESO-1 157–170, shown to bind the HLA-DP04 allele as a negative control.38

Figure 2.

Radium-4 TCR Promotes Specific Tumor Lysis

(A) Lysis kinetics obtained by BLI assay of effector T cells transduced with Radium-4 TCR (red), Radium-6 (Rad6) TCR (blue), or mock-transduced T cells (black) cocultured with a HLA-DP04+ HLA-DR04+ EBV-LCL cell line, loaded or not with hTERT 611–626 peptide (phTERT), TGF-βRII frameshift mutated 127–145 peptide (p621), or NY-ESO-1 157–170 peptide (pNY-ESO-1). Representative graphs of two experiments. Data represent mean ± SD of triplicates. Statistics were calculated on the 22-h time point. (B) Corresponding intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α production of the same effector T cells (CD4+ cells) cocultured in a similar fashion as described in (A). Bars represent mean ± SD of triplicates. (C) Measurements of the Annexin V signal restricted to phase/GFP+ detected objects of ESTDAB-1000 spheroids in the presence of Rad-4 TCR, Rad-6 TCR, or mock-transduced T cells. Data represent mean ± SD of 36-plicates. Pooled metrics of two independent experiments are shown. (D) Measurements of GFP signal of ESTDAB-1000 spheroids in the presence of Rad-4 TCR, Rad-6 TCR, or mock-transduced T cells. Data represent mean ± SD of 36-plicates. Pooled metrics of two experiments are shown. (E) Representative micrographs of ESTDAB-1000 spheroids in the presence of Radium-4 or Radium-6 TCR-transduced cells or mock T cells. Green and red signals come from ESTDAB-1000 GFP+ cells and Annexin V, respectively. Scale bar represents 250 μm.

Since MHC class II molecules are normally not loaded with proteasome-derived peptides,39 we created a cell line to further study the impact of Radium-4 TCR-dependent cytotoxicity. To this end, we designed an invariant (Ii) chain construct, where the CLIP (class-II-associated invariant chain peptide) region was replaced by the target hTERT peptide, as we recently reported with other class II peptides.37 Although ESTDAB-039 expressed low levels of endogenous hTERT, we stably transduced this HLA-DP04+ melanoma cell line (which became ESTDAB-1000) to create a target cell line constitutively expressing the hTERT 611–626 epitope. We then validated the cytokine production capacity of Radium-4 TCR-redirected T cells against ESTDAB-1000 (Figures S6A and S6B) before we compared it with the parental ESTDAB-039 loaded with the hTERT peptide, demonstrating that ESTDAB-1000 cells were suitable targets. We further evaluated Radium-4 T cell potency against ESTDAB-1000 spheroids by measuring Annexin V (red) and GFP (green) signals of target cells in live-cell imaging. Similar to data from 2D cultures, Radium-4 TCR-redirected T cells demonstrated efficacy and specificity in killing of these complex structures compared to control T cells (Figures 2C–2E). These results were confirmed both in Annexin V and a bioluminescence (BLI)-based cytotoxicity assay against multiple cell lines (ESTDAB-039, EBV-LCL, and Granta-519) expressing the Ii chain construct or loaded or not with hTERT peptide for the original patient T cell clones, Radium-4 TCR-transduced and mRNA-electroporated T cells (Figures S7A–S7D). In addition, Radium-4 TCR-electroporated T cells demonstrated the same efficiency in terms of kinetics, efficacy, and specificity. We then demonstrated the cytolytic capacity of the Radium-4 TCR CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subset separately or combined at various effector-to-target (E:T) ratios against ESTDAB-039 preloaded with hTERT peptide (Figure S8A) or ESTDAB-1000 (Figure S8B). At high E:T ratios and high antigen concentrations, CD8+ T cells or the combined population showed slightly faster kinetics, but these differences were not significant. This confirmed both the coreceptor independency of Radium-4 TCR and the cytolytic capacity of both CD8 and CD4 T cell subsets. Taken together, these data support that melanoma cells expressing a modified Ii chain construct, ESTDAB-1000, could be used as a model target for CD4 TCR-dependent T cell cytotoxicity.

Radium-4 TCR T Cells Recognize and Kill HLA-DP04+ and HLA-DP03+ Tumor Cells

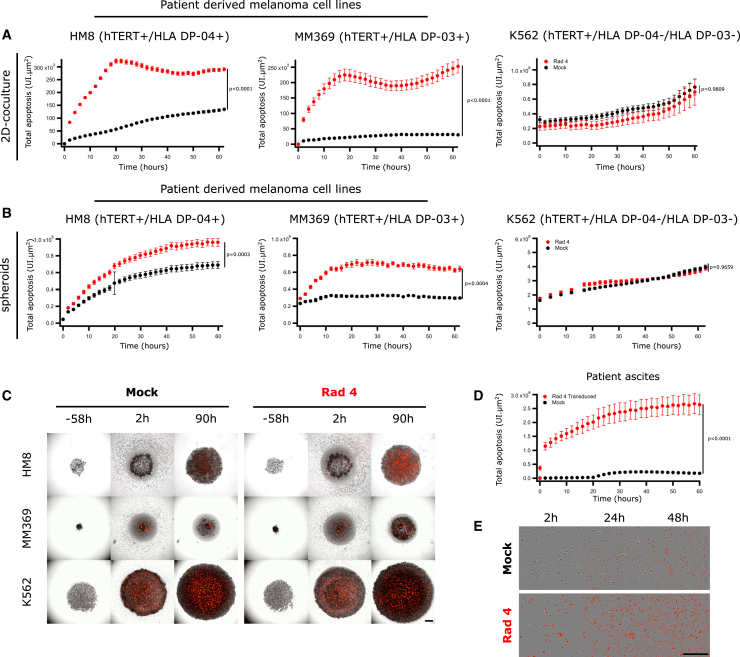

To assess if Radium-4 TCR-redirected T cells could also recognize endogenous levels of hTERT presented on HLA-DP04+, we tested their cytotoxicity against patient-derived melanoma cell lines in Annexin V assays (Figures 3A–3C and S9). Radium-4 TCR T cells demonstrated higher killing capacity against melanoma cell lines HM8, MM369, and ESTDAB-039 (Figure S9A) than the HLA-DP04− control cell lines K562 and MM382 (Figure S9B), both in 2D and 3D cultures. Surprisingly, the Radium-4 TCR T cells specifically killed the MM369 cell line, which was tissue typed to be homozygous for the HLA-DP∗03:01 allele. We confirmed the presentation of the hTERT 611–626 epitope on HLA-DP03 and its recognition by the Radium-4 TCR by demonstrating that peptide-loaded HLA-DP03+ EBV-LCLs were also specifically recognized by Radium-4 TCR T cells (Figure S10).

Figure 3.

Radium-4 TCR Recognizes Endogenous Antigen

(A) Lysis kinetics obtained by measuring the Annexin V signal of effector T cells transduced with Radium-4 TCR cocultured with patient-derived melanoma cell lines (hTERT+/HLA-DP04+ or HLA-DP03+) or the K562 cell line (hTERT+/HLA-DP04−). Pooled graphs of two experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM of dodecaplicates. (B) Lysis kinetics obtained by measuring the Annexin V signal of effector T cells transduced with Radium-4 TCR cocultured with spheroids of patient-derived melanoma cell lines (hTERT+/HLA-DP04+ or HLA-DP03+) or the K562 cell line (hTERT+/HLA-DP04−). Pooled graphs of two experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM of hexaplicates. (C) Representative micrographs of HM8, MM369, and K562 spheroids in the presence of Radium-4 or mock T cells. Red signals come from Annexin V. Scale bar, 250 μm. (D) Annexin V signal after coculture of effector T cell patient ascites cells measured by live-cell imaging. Data represent mean ± SD of octoplicates. Statistics were calculated on the 10-h time point. (E) Representative micrographs of T cells and patient ascites coculture. Red signals come from Annexin V. Scale bar, 250 μm.

Importantly, the killing capacity of Radium-4 TCR T cells was tested against ascites cells from the pancreatic cancer patient from which the Radium-4 TCR originated. The T cell clone was previously shown to proliferate against ascites cells.23 Here, we demonstrated significant killing of the ascites cells by Radium-4 TCR-transduced cells (Figures 3D and 3E) and confirmed that this was also the case for TCR mRNA-electroporated T cells and the patient T cell clone compared to mock T cells (Figure S9E).

In summary, these results demonstrate that a CD4 TCR can induce target killing and that the specificity and potency of Radium-4 TCR-redirected T cells against tumor cells are independent of their spatial organization (2D or 3D).

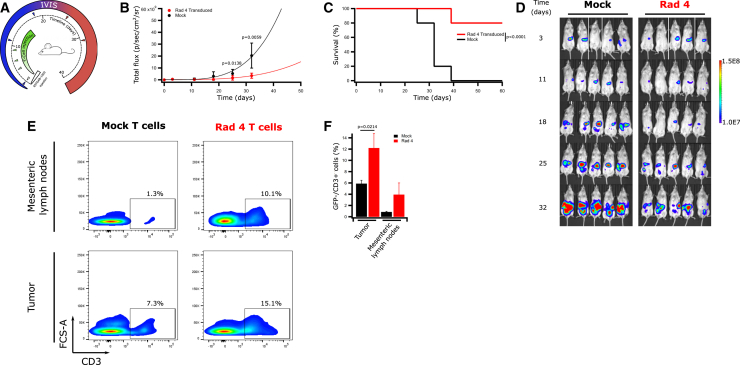

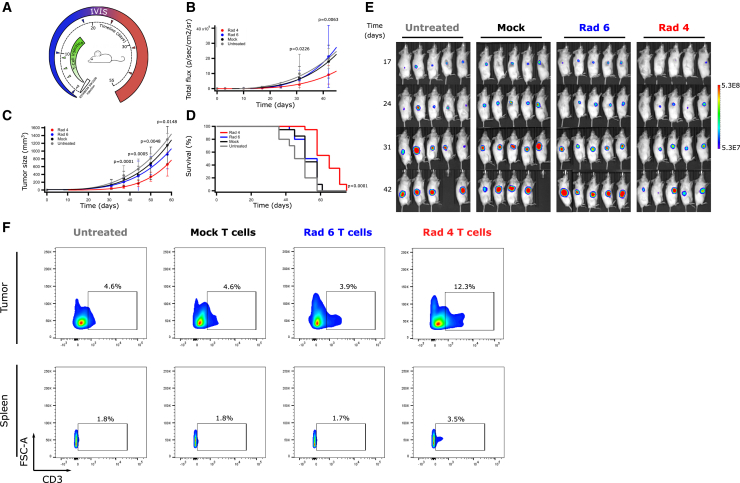

Transduced Radium-4 T Cells Improve Survival of Melanoma-Carrying Mice

To test whether lymphocytes transduced with Radium-4 TCR could mediate anti-tumor responses in vivo, NSG mice were engrafted with ESTDAB-1000. Mice received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections with either Radium-4 TCR or mock-transduced T cells (Figure 4A). Tumor load was measured on the day of the first treatment (d0) and every 3–7 days after until tumor burden was too large for accurate measurements or mice had to be euthanized. Tumor load and survival were plotted to compare between the groups (Figures 4B–4D). The treatment with Radium-4 TCR T cells significantly reduced the tumor load compared to mock T cells and greatly enhanced survival of the treated mice. Upon reaching humane endpoint criteria, mice were sacrificed, and both tumor and mesenteric lymph nodes were analyzed for the presence of lymphocytes. Mice treated with Radium-4 TCR T cells demonstrated increased infiltration of T cells in both tissue types in comparison with the mock condition (Figures 4E and 4F). The potency of Radium-4 TCR-transduced T cells was then tested in a more physiologically relevant setting by subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of melanoma ESTDAB-1000 cells and intravenous (i.v.) transfer of Radium-4, Radium-6 TCR, or mock-transduced T cells (Figure 5A). Again, Radium-4 T cells reduced the tumor load and size compared to Radium-6 or mock conditions (Figures 5B, 5C, and 5E) and significantly improved overall survival of the mice (Figure 5D). Radium-4 T cells demonstrated enhanced in vivo persistence in tumor tissue and spleen compared to Radium-6 and mock T cells >50 days after the last injection (Figure 5F). Overall, Radium-4 TCR-transduced T cells could control the tumor growth, probably due to the improved kinetics of a stable system. These data support Radium-4 T cell efficacy in vivo.

Figure 4.

Transduced Radium-4 T Cells Control Tumor Load In Vivo upon Intraperitoneal (i.p.) Administration

(A) NSG mice were engrafted with GFP/Luc+ ESTDAB-1000 tumors i.p., and 3 days after tumor inoculation, mice were randomized and received i.p. injections of mock or Radium-4 TCR-transduced T cells (n = 10 for each group) for a total of 4 injections. (B) ESTDAB-1000 tumor growth curves after mock or Radium-4 TCR-transduced T cell transfer. Data represent means ± SD of two independent experiments pooled. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice shown in (D). Survival curves were analyzed with a Mantel-Cox (log-rank) test. (D) Micrographs obtained from In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) of mice inoculated with ESTDAB-1000 and treated with mock or Radium-4 TCR-transduced T cells. (E) Percentage of GFP−/CD3+ cells in single-cell suspensions made from tumor or mesenteric lymph node tissues extracted from mice treated with transduced Radium-4 or mock-transduced T cells. Representative flow diagrams from three independent animals. (F) Summary of the proportion of GFP−/CD3+ cells shown in €. Bars represent mean ± SD. Statistical validation was realized between Radium-4 and mock conditions.

Figure 5.

Transduced Radium-4 T Cells Control Tumor Load In Vivo upon Intravenous (i.v.) Administration

(A) NSG mice were engrafted with GFP/Luc+ ESTDAB-1000 tumors subcutaneously, and 3 days after tumor inoculation, mice were randomized and received i.v. injections of mock-transduced, Radium-4 TCR-transduced, or Radium-6 TCR-transduced T cells or no treatment (n = 10 for each group; 5 for the untreated condition) with a total of 4 injections. (B and C) ESTDAB-1000 tumor growth curves after no treatment or mock, Radium-4 TCR, or Radium-6 TCR T cell transfer. Tumor load was measured by IVIS (B) or caliper (C). Data represent means ± SD of two independent experiments pooled. (D) Corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Survival curves were analyzed with a Mantel-Cox (log-rank) test. (E) Micrographs obtained from IVIS of mice inoculated with ESTDAB-1000 and left untreated or treated with mock-transduced T cells, Radium-6 TCR-transduced T cells, or Radium-4 TCR-transduced T cells. (F) Percentage of GFP−/CD3+ cells in single-cell suspensions made from tumor or spleen tissues. Representative flow diagrams from three independent animals.

We previously showed that mRNA-redirected T cells, with either CAR40 or an MHC class I-restricted TCR,41 could limit tumor progression in NSG mouse xenograft models. We thus injected NSG mice i.p. with the melanoma cell line ESTDAB-1000. After 3 days, mice were randomized and injected i.p. every other day with Radium-4 mRNA or mock-transfected T cells or with medium (Figure S11A). However, there was no difference seen in tumor burden or overall survival of the mice (Figures S11B and S11C) after treatment with mRNA-electroporated Radium-4 T cells compared with mock T cells in this tumor model.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that in vivo anti-tumor efficacy of Radium-4 TCR-transduced T cells reduced tumor growth and enhanced survival of tumor-challenged mice.

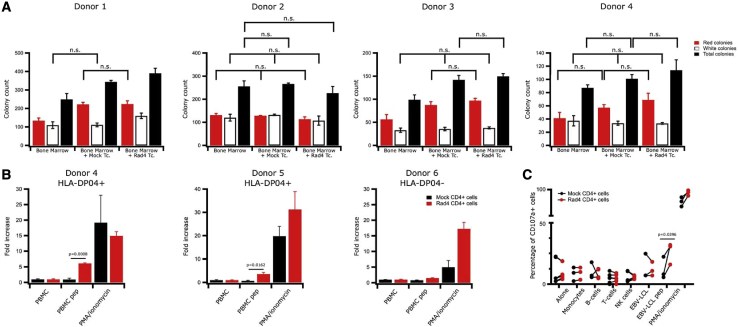

Radium-4 T Cells Do Not Recognize Hematopoietic Cells

Potential crossreactivity of T cells against hematological stem cells was addressed, as such cells have been reported to express telomerase.42,43 We studied the impact of Radium-4 TCR-expressing T cells on the colony-forming ability of bone marrow progenitor cells. We used a colony-forming unit (CFU) assay to demonstrate that myeloid and erythroid colony formation in bone marrow samples was not affected. To this end, we cocultured HLA-DP04+ bone marrow cells from four different donors with autologous Radium-4 TCR-expressing T cells at an E:T ratio of 10:1. As shown, we did not observe any change compared to the mock T cells (Figure 6A). These observations demonstrated that Radium-4 T cells were not cytotoxic against autologous stem cells from bone marrow, suggesting that its clinical use would be safe. These results were confirmed by several coculture assays of Radium-4 and mock T cells from healthy donors with their respective peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in bulk or separated. Our results show that Radium-4 T cells reacted only against PBMCs from HLA-DP04+ donors loaded with peptide (Figure 6B). The hTERT-specific, redirected T cells did not show any signs of crossreactivity against the various purified subsets of hematopoietic cells (Figure 6C) and did not secrete more inflammatory cytokines in the absence of the cognate peptide or HLA allele than their mock T cell counterparts (Figure S12). Again, in the presence of cognate target, multiplex cytokine assays revealed specific production of TNF-α and IFN-γ that are specific of Th1/Tc1 cells, thus confirming intracellular flow cytometry analysis. Overall, our findings demonstrate that Radium-4 TCR-redirected T cells are potent and safe.

Figure 6.

Redirected Radium-4 T Cells Do Not Recognize Hematopoietic Cells

(A) Healthy donor bone marrow progenitor cells were cocultured with autologous T cells, either transfected with Radium-4 TCR mRNA or mock-transfected T cells for 6 h at an E:T ratio of 10:1. The cells were then plated in semisolid methylcellulose progenitor culture for 14 days and scored for the presence of colony-forming unit (CFU)-erythrocyte (E), red; CFU-granulocyte macrophages (GMs), white colonies; and in gray the total number of colonies. Data represent mean ± SD of triplicates. (B) Fold increase in cytokine production (IFN-γ, TNF-α) measured by flow cytometry upon coculture of stably transduced Radium-4 TCR T cells or mock-transduced T cells from three donors (two HLA-DP04+ and one HLA-D04−) with their respective PBMCs. Data represent mean ± SD of triplicates. (C) Percentage of CD107a+-transduced T cells from three donors, as described in (B) cocultured with purified subpopulations of PBMC. PMA-ionomycin and hTERT 611–626 peptide-loaded HLA-DP04+ EBV-LCL stimulations were used as a positive control.

Discussion

There is a dire need for new treatment options in solid cancer. Despite ACT being one of the most promising new treatment approaches in hematological cancer, it has not yet proven very successful in the treatment of solid tumors. Although no TCRs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), TCR therapy may have a clear advantage over CARs in solid tumors. First, TCR targets are numerous and include any proteins (intra- or extracellular) presented on the cell surface by MHCs. Second, TCRs require very low antigen density, and only one pMHC complex can be sufficient for TCR-mediated T cell activation.44 Third, in this, setting the risk of TCR crossreactivity with normal tissues is low.

We report on a TCR recognizing one of the most universally expressed cancer antigens, hTERT. This TCR is restricted to a very common HLA allele, HLA-DP04, making it applicable for a large group of cancer patients. The recognition by the original T cell clone of both autologous ascites cells and processed hTERT protein supports its clinical efficacy.23 The clinical potential of our TCR is further supported by its high affinity for hTERT and its partial CD4 coreceptor independence. The recognition by redirected Radium-4 T cells of their antigen following digestion and presentation on APCs suggests recognition of the cognate antigen in vivo. Furthermore, the reduction of patient-derived melanoma cells in a 3D spheroid model, which is more representative of tumor tissue, speaks to the potential efficacy of our TCR in the clinical treatment of solid tumors. This is important information to gather on potential immunotherapy treatments, since many CARs and TCRs studied have displayed quite different effects in cell-line models than in patients.45

We also demonstrated that the Radium-4 TCR recognized an additional HLA-DP allele, HLA-DP03 (12.5% worldwide).22 It is not uncommon for peptides to be presented by several HLA-DP molecules,22,46 and this can therefore further broaden the application of our TCR.

Testing of both transiently and stably redirected T cells is instrumental to enable safe first-in-man clinical studies, as well as long-term stability and efficacy in cancer treatment. Transient TCR expression following mRNA electroporation allows for rapid termination of T cell activation by cessation of T cell infusions, which is critical to reduce the impact of any potential crossreactivity or other toxicity.

Retrovirally transduced T cells expressing Radium-4 TCR were superior to mRNA-transfected cells in most assays, including our mouse model. This is expected, since following electroporation, TCR expression is maximal 18–22 h and decreases when the T cell recognizes its target and divides, reaching undetectable levels after 4 days.41 Thus, transduced T cells are likely superior for clinical cancer eradication once severe toxicity is ruled out using transiently transfected cells.

Available methods to evaluate crossreactivity of MHC class II-restricted TCRs are limited, but we consider this risk low for Radium-4 TCR, given the MHC context; first, because the construct was not modified or enhanced and has already been thymically selected. Second, the on-target and off-tumor crossreactivity for hTERT peptides would be predicted to most likely affect hematopoietic and/or germ cells since the protein is not normally expressed in other tissues.43,47 However, our assays did not detect any toxicity against hematopoietic stem cells. Third, there were no reported adverse events in the patient from whom the TCR was isolated.23 Although in theory, there is a potential risk of mispairing between introduced and endogenous TCR chains creating new specificities, this has not been observed in clinical studies.48 Others have reported on hTERT TCRs in the context of MHC class I.49,50 Although these TCR studies did not demonstrate toxicity against CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors in vitro, the granulocytic compartment of the bone marrow was affected in vivo.50 This further emphasizes the benefit of using mRNA transfection as a safety measure in first-in-man clinical testing, and this has already been proven feasible for CAR T cell therapy in several solid tumors.51, 52, 53 We are currently running clinical testing of mRNA transfection in TCR therapy in microsatellite instable colon cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03431311; S.M.M., unpublished data). All clinical studies of TCR therapy published to date, except one,54 have used MHC class I-restricted TCRs (recently reviewed in Wolf et al.55).

One tumor-escape mechanism is to downregulate MHC class I in order to prevent recognition by the immune system.56 MHC class II-restricted CD4+ T cells could bypass this and induce a more robust and diverse anti-tumor immune response and improve outcomes in cancer immunotherapy. They are capable of directly recognizing MHC class II-expressing tumor cells and can inhibit tumor growth upon adoptive transfer either alone or in combination with CD8+ T cells.57,58 Their main mechanism of action is through indirect recognition of tumor-derived antigens on APCs, thereby providing help for cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and orchestrating a broader immune response leading to epitope spreading.59 Approaches using CD4+ T cells in TCR therapy could therefore lead to more durable therapeutic effects. However, in vivo assays in mice, as presented here, only demonstrate direct killing of the target, whereas the helper function of Radium-4 TCR-expressing T cells is indiscernible due to the lack of a human immune system. This may underestimate the capacity of transiently redirected T cells to engage other players in the immune system, as observed for mRNA-engineered CAR T cells inducing epitope spreading in patients.51 Consequently, although stable Radium-4 TCR expression was superior in controlling tumor growth in our mouse model, it should not preclude the use of mRNA for a first-in-man clinical protocol, since it is safer, and the clinical benefit is likely underestimated by this tumor model.

In conclusion, we show here that Radium-4 TCR, a CD4 T cell-derived TCR, has the potential to be effective in immunotherapy treatment of solid cancer. The unique universality of the target, hTERT; its importance for EMT, cancer stem cells, and metastasis; as well as the commonality of the HLA allele used for its presentation support further clinical development of this TCR.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines, Media, and Reagents

EBV-LCLs used as target cells were generated by immortalization of B cells from PBMCs of patients and donors using EBV supernatant from the marmoset cell line B95.8, as previously described.60 Additionally, we used EBV-LCLs 9018, 9040, and 9082 from the 9th and 10th International Histocompatibility Workshops.61 Patient-derived melanoma cells lines HM8, MM369, and MM382 were established in-house from melanoma lymph node or brain metastases (REK S-06151, 2012/2309, 2015/2434). Melanoma cell line ESTDAB-039 was obtained from the European Searchable Tumor Line Database (Tübingen, Germany), K562 purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Hek-Phoenix (Hek-P) and Granta-519 were from our collection.62 All cell lines were passaged for fewer than 6 months after their purchase. Cell lines were tested for mycoplasma contamination using a PCR-based detection kit (VenorGeM; Minerva Biolabs, Berlin, Germany). Cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with gentamicin and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and Hek-P were grown in DMEM (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), supplemented with 10% HyClone FCS (GE Healthcare) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (penicillin/streptomycin [p/s]; GE Healthcare).

All T cells were grown in X-Vivo 15 (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland), supplemented with 5% CTS serum replacement (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 100 U/mL interleukin (IL)-2 (Proleukin; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), denoted complete medium hereafter, unless otherwise stated.

In Vitro mRNA Transcription of TCR Targeting hTERT

A hTERT-specific, HLA-DP04-restricted TCR was identified in a CD4+ T cell clone from a vaccinated pancreatic cancer patient and named Radium-4.23 The in vitro mRNA synthesis was performed, essentially as previously described.63 Anti-Reverse Cap Analog (Trilink Biotechnologies, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to cap the RNA. The mRNA was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Retroviral Particle Production

Viral particles were produced, as described in Wälchli et al.,29 and used to transduce T cells. In brief, 1.2 × 106 Hek-P cells were plated. Transfection was performed using Extreme-gene 9 (Roche) with a mix of DNA, including the retroviral packaging vectors and the expression vector, to an equimolar ratio. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with 1% HyClone FCS containing DMEM, and the cells were transferred to a 32°C incubator. Supernatants were harvested after 24 h and 48 h of incubation.

In Vitro Expansion of Human T Cells

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics (Oslo, Norway) ( Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics [REC] approval number: 2013/624, 2016/2247). T cells from healthy donors were expanded using a protocol adapted for good manufacturing practice (GMP) production of T cells employing CD3/CD28 Dynabeads, essentially as previously described.32 In brief, PBMCs were isolated from buffy coats by density gradient centrifugation and cultured with Dynabeads (CTS Dynabeads CD3/CD28, provided by Gibco; Life Technologies AS, Oslo, Norway) at a 3:1 ratio in complete X-Vivo 15 medium with 100 U/mL IL-2 for 10 days. After 10 days expansion, CD3/CD28 Dynabeads were removed, and T cells were electroporated with TCR mRNA, either frozen or used directly.

Electroporation of Expanded T Cells

Expanded T cells were washed twice and resuspended in X-Vivo 15 medium (Lonza) at 70 × 106 cells/mL. The mRNA or water (mock) was mixed with the cell suspension at 100 μg/mL and electroporated in a 4-mm gap cuvette at 500 V and 2 ms using a BTX 830 Square Wave Electroporator (BTX Technologies, Hawthorne, NY, USA). Immediately after transfection, T cells were rested overnight in complete medium before being frozen. For use in the in vivo model, the T cells were thawed on the day of treatment and rested in complete medium for 2 h before injection.

CD4+ and CD8+ T Cell Isolation

CD8+ T cells were isolated using the Dynabeads CD8 Positive Isolation Kit (Invitrogen by Life Technologies AS, Norway), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The negative fraction was used as CD4+ T cells. Purity of both populations was assessed by flow cytometry and found to be above 97%. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were then electroporated separately.

Transduction of Expanded T Cells

PBMCs were incubated for 2 days in a 24-well plates coated with CD3 and CD28 at 106 cells/mL. A 24-well plate was coated with 50 μg/mL of retronectin during 3 h at room temperature (RT) before being washed with PBS and blocked with a solution of 1 mg/mL of fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 30 min. 1 mL of virus solution was deposited in each well and topped with 500 μL of activated T cells at a concentration of 0.3 × 105 cells/mL. The plate was then incubated for 30 min at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 30 min, sealed, and then spun down at 750 g, 32°C, during 60 min before being placed back in the incubator. The same spinoculation step was repeated the following day before the cells being collected, spun down, washed, and resuspended in complete X-Vivo 15 medium for 2 days before the expression of the TCR was checked and the cells expanded using the procedure described above.

In Vitro Functional Assay, Antibodies, and Flow Cytometry

All antibodies were purchased from eBioscience (Thermo Fisher Scientific), except where noted. TCR expression was determined as follows: T cells were washed in 500 μL of FCS and spun down. The supernatant was discarded, and the cells were incubated with 5 μL of anti-CD3-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and/or anti-CD34APC. The hTERT peptide, EARPALLTSRLRFIPK (amino acid [aa] sequence 611–626) (sequence hTERT; GenBank: AB085628), was synthesized by ProImmune (Oxford, UK). The 173-aa recombinant hTERT protein fragment (563–735) was obtained from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA). For cytokine production assays, T cells were stimulated for 16 h with APCs and loaded or not with 1 or 10 μM (as indicated) hTERT 611–626 peptide, NY-ESO-1 157–170 peptide, or TGF-βRII frameshift peptide p621, 127–145,64 at an E:T ratio of 1:2 and in the presence of BD GolgiPlug and BD GolgiStop at recommended concentrations. For CD107a degranulation assays, PerCP-Cy5.5-labeled anti-CD107a antibody (BD Biosciences, San José, CA, USA) was added from the start of the coincubation and assessed after 6 h. For intracellular staining, cells were stained using the PerFix-nc Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The following antibodies were used: CD4-BV421 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA); CD8-phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy7, IFN-γ-FITC, and TNF-α-PE (BD Biosciences). For toxicity assays of Radium-4 TCR and mock-transfected T cells against autologous PBMCs, the PBMCs were loaded with CellTrace Violet (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) to distinguish targets by gating, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The following antibodies were used to assess reactivity: CD4-APC, CD8-PE-Cy7, CD3-BV605 (BD Biosciences); IFN-γ-FITC and TNF-α-PE (BD Biosciences). Cells were acquired on a BD FACSCanto flow cytometer and the data analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). To better exemplify cytokine production and correct for T cell fitness variability, cytokine production (U.A.) was calculated using the following formula: f(x) = (((x-min(x)) × 100)/(max(x) − min(x))), where x represents the percentage of cytokine-producing cells. In this case, max corresponds to the maximum value obtained through the experiments (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate [PMA]-ionomycin), and the minimum (min) was the lowest value measured (mock T cells against target without peptide loading).

For analysis of toxicity against purified hematopoietic cell lineages, T cells were plated in duplicates with autologous CD19+ B cells, CD3+ T, CD56+ natural killer (NK) cells, and CD14+ monocytes from three healthy donor PBMCs, sorted with positive or negative isolation kits (Dynabeads, Thermo Fisher Scientific), at E:T ratios of 1:2, and then, CD107a expression by effector T cells was analyzed.

Mock or Radium-4 TCR-redirected T cells from two donors were cocultured for 24 h with their respective PBMCs, loaded or not with the hTERT 611–626 peptide at an E:T ratio of 1:2. Culture supernatant was harvested, and the cytokine release was measured using the BioplexPro Human Cytokine 17-plex Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The analysis was performed on the Bio-Plex 200 system instrument from Bio-Rad.

T Cell Phenotyping by CyTOF

Six million Radium-4 TCR T cells were cocultured or not with ESTDAB-039 cells, loaded or not with hTERT peptide, at a 1:2 E:T ratio for 24 h prior to the CyTOF experiment. Briefly, cells were resuspended in Maxpar Cell Staining Buffer (Fluidigm, San Francisco, CA, USA) in the presence of 1× cisplatin (Fluidigm) and incubated for 5 min at RT. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with Fc receptor-blocking solution (aggregated gamma-globulin) for 10 min and then incubated with the antibody mix CD3, CD4, CD8, CCR5, CXCR3, CD62L, CD27, CD44, LAG3, TIGIT, CD28, CD57, CD25, CD161, NKG2D, CD137, HLA-DR, CTLA4, TIM3, PD1, and CD45 (Fluidigm) for 30 min at RT. Samples were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 4% of paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with methanol for 1 h. After two washes in PBS, cells were resuspended in PBS containing 1× intercalator (Ir) (Fluidigm) and incubated for 20 min at RT. Following one wash in PBS, cells were pelleted until ready to run in CyTOF. Prior to sample acquisition, cells were resuspended in water with 10% of calibration beads and filtered before being injected into the CyTOF 2 machine (Fluidigm). Analysis was performed using Cytobank- (https://www.cytobank.org/). Typical gating strategy was applied as follows: (1) EQ-140 versus EQ-120 to exclude calibration beads; (2) event length versus Ir-191 to gate singlets; (3) cisplatin versus CD45 to gate live T cells. Gated events were then run using the viSNE algorithm with the following parameters: 1,000 iterations, 70 perplexity, 0.5 theta.

Annexin V-Based Cytotoxicity Assay

104 tumor cells (EBV-LCL, ESTDAB-1000, patient ascites cells) or 2 × 103 tumor cells (HM8, MM369, MM382, and K562; preloaded or not with hTERT 611–626 peptide) were incubated in a 96-well, flat-bottomed plate (previously coated with Cell-Tak [Corning, New York, NY, USA] for patient ascites cells and K562 cells) in 200 μL of complete RPMI-1640 medium for 24 to 48 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. The plate was then centrifuged at 100 × g for 1 min, and 100 μL of the supernatant was discarded. 50 μL of a 1:200 solution of Annexin V red (Essen Biosciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), diluted in complete RPMI 1640, was added in each well, and the plate was consecutively incubated at 37°C, 5%CO2, during 15 min. Effector cells (Radium-4 transduced or transfected in primary T cells, patient T cell clone, or mock T cells), previously washed and resuspended in complete RPMI-1640 medium, were introduced in each well at a final concentration of 5 × 104 cells/mL (100 μL/well). The plate was then put into an Incucyte S3 (Essen Bioscience, Newark, UK) with the following settings: 12 images/day, 4 images/well, 2 channels (phase and red). Analysis of cytotoxicity was performed using Incucyte software. Metrics were then extracted and corrected using Igor Pro 8.1 (Wavemetrics, Portland, OR, USA).

BLI-Based Cytotoxicity Assay

Luciferase-expressing tumor cells were counted and resuspended at a concentration of 3 × 105 cells/mL. Cells were given D-luciferin (75 μg/mL; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and were placed in 96-well, white round-bottomed plates as 100 μL cells/well in triplicates. Effector T cells were added at a 20:1 E:T ratio unless stated otherwise. In order to determine spontaneous and maximal killing, wells with target cells only or with target cells in 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were seeded. Cells were left at 37°C, and the BLI was measured with a luminometer (VICTOR Multilabel Plate Reader; PerkinElmer) as relative light units (RLUs) at indicated time points. Target cells incubated without any effector cells were used to determine baseline spontaneous death RLU at each time point. Triplicate wells were averaged, and lysis percentage was calculated using the following equation: % specific lysis = 100 × (spontaneous cell death RLU – sample RLU)/(spontaneous death RLU – maximal killing RLU). Metrics were then corrected using Igor Pro 8.1 (Wavemetrics, USA). Sigmoid curves (no Hill equation) were fitted for every set of points (using Igor Pro 8.1) as a guide for the eye with standard deviation as weighting factor.

Multicellular Tumor Spheroid (MCTS) Formation

Wells of a 96-well plate were coated with 50 μL of a 1.5% solution of agarose (Corning, New York, NY, USA) in PBS and left to polymerize during 60 min at RT. 1 × 103 HM8, MM369, MM382, ESTDAB-1000, or K562 cells in 200 μL of complete RPMI 1640 was then added per well. Plates were spun down for 15 min at 1,000 × g and incubated for 4 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. 50 μL of a 1:200 solution of Annexin V Red (Essen Bioscience), diluted in complete RPMI 1640, was added per well, and the plate was consecutively incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2, for 15 min. Mock, Radium-6 TCR, or Radium-4 TCR-transduced T cells previously washed and resuspended in complete RPMI-1640 medium were introduced in each well at a final concentration of 4 × 104 cells/mL (100 μL/well). The plate was then put into an Incucyte S3 instrument with the same settings as described above.

Mouse Xenograft Studies

All mouse experiments were approved by the Norwegian Food Safety Authority (approval ID8740). NSG mice were bred in-house under an approved institutional animal care protocol. 6- to 8-week-old mice were injected i.p. or s.c. with 106 ESTDAB-1000 tumor cells (n = 10) per condition, except medium condition, where n = 5. Tumor growth was monitored by BLI imaging using the Xenogen Spectrum system and Living Image version (v.)3.2 software (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). Anesthetized mice were injected i.p. with 150 mg/kg body weight of D-luciferin (PerkinElmer). Animals were imaged 10 min after luciferin injection. For the transiently redirected T cell experiment, tumor-bearing mice were randomized and injected i.p. 7 times (at days 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 14, and 16) with 107 mock cells or 107 Radium-4 TCR mRNA-transfected T cells or with medium.

For the transduced T cell i.p. experiment, tumor-bearing mice were randomized and injected 4 times (at days 3, 5, 7, and 9) with 107 mock cells or 107 Radium-4 TCR-transduced T cells. For the transduced T cell experiment, i.v. tumor-bearing mice were randomized and injected 4 times (at days 3, 7, 9, and 10) with 107 mock cells, 107 Radium-6 TCR, or 107 Radium-4 TCR-transduced T cells. Upon reaching humane endpoints, mice were sacrificed, and tumor, mesenteric lymph nodes, and spleen tissues were harvested. Single-cell suspension from isolated tissues was washed repeatedly, blocked with 1 mg/mL of gamma-globulin (made in-house) at RT for 10 min, and marked with anti-human CD3-PE-Cy7 (BD Biosciences). Cells were acquired on a BD FACSCanto flow cytometer.

CFU Assay

Bone marrow progenitor cells were preincubated with autologous T cells for 6 h before the cells were plated in semisolid methylcellulose medium, MethoCult (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada), and left for 14 days at 37°C, 5% CO2, and >95% humidity. With the use of a high-quality microscope, individual clusters of cells (colonies) were easily identified. A 60-mm scoring grid was at the bottom of each dish, and all colonies were counted and divided into two groups: (1) CFU-erythroid (CFU-E) with erythroblasts and/or burst-forming erythroid units, red colonies, and (2) CFU-granulocyte macrophages (GM), white colonies. Cell clusters were not counted as colonies unless the number of visible cells was >40.

Statistical Analysis

Statistics were made with multivariated bidirectional Student’s t test (single comparison), 1-way ANOVA (multiple comparison), or 2-way ANOVA (multiple comparison with time progression), all with Tukey correction. Mantel-Haenszel test was used as a log-rank estimator for survival curves. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA, USA).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our colleagues from the Department of Cellular Therapy; in particular, Ms. Hedvig Vidarsdotter Juul for expert technical assistance and Dr. Stein Sæbøe-Larssen for providing the pCIp102 expression vector. We thank Dr. Rainer Löw (EUFETS AG, Germany) for providing the luciferase-reporter vector and Gibco and Life Technologies AS for supplying CTS Dynabeads CD3/CD28. The J76 cells were a kind gift from Dr. Miriam Hemskeerk (Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands) and the ESTDAB-039 cell line generously provided by Dr. Graham Pawelec (University of Tübingen, Germany). We would like to thank the Department of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Oslo University Hospital-Rikshospitalet, Oslo, Norway, for its kind help with HLA typing. We also thank the Flow Cytometry Core Facility of OUS for providing technical assistance. This study was supported by The Research Council of Norway (grant numbers 244388 and 254817) and the Norwegian Health Region South East (grant numbers 2017075 and 2016006).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W. and E.M.I.; Methodology, P.D., G.M.M., V.A.F., G.K., G.G., S.W., and E.M.I.; Investigation, P.D., H.K., S.M.M., A.W.-M., S.P., M.M., and M.R.M.; Resources, G.M.M., V.A.F., G.K., G.G., S.W., and E.M.I.; Writing − Original Draft, P.D., S.M.M., S.W., and E.M.I.; Writing − Review & Editing, all authors; Visualization, P.D., S.M.M., M.R.M., S.W., and E.M.I.; Supervision, S.W. and E.M.I.; Project Administration, E.M.I.; Funding Acquisition, G.K., G.G., S.W., and E.M.I.

Declaration of Interests

G.G., G.K., S.W., and E.M.I. are inventors on the patent WO2019166463. G.G. and G.K. are shareholders in Zelluna Immunotherapy AS. S.P. is currently employed by Zelluna Immunotherapy AS. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.11.019.

Contributor Information

Sébastien Wälchli, Email: sebastw@rr-research.no.

Else Marit Inderberg, Email: elsin@rr-research.no.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Maude S.L., Frey N., Shaw P.A., Aplenc R., Barrett D.M., Bunin N.J., Chew A., Gonzalez V.E., Zheng Z., Lacey S.F. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee D.W., Kochenderfer J.N., Stetler-Stevenson M., Cui Y.K., Delbrook C., Feldman S.A., Fry T.J., Orentas R., Sabatino M., Shah N.N. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2015;385:517–528. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinrichs C.S., Restifo N.P. Reassessing target antigens for adoptive T-cell therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:999–1008. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zanetti M. A second chance for telomerase reverse transcriptase in anticancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017;14:115–128. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harley C.B., Kim N.W., Prowse K.R., Weinrich S.L., Hirsch K.S., West M.D., Bacchetti S., Hirte H.W., Counter C.M., Greider C.W. Telomerase, cell immortality, and cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1994;59:307–315. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim N.W., Piatyszek M.A., Prowse K.R., Harley C.B., West M.D., Ho P.L., Coviello G.M., Wright W.E., Weinrich S.L., Shay J.W. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shay J.W. Telomerase in human development and cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 1997;173:266–270. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199711)173:2<266::AID-JCP33>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez-Garcia I., Ortiz-de-Solorzano C., Montuenga L.M. Telomeres and telomerase in lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2008;3:1085–1088. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181886713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagunas A.M., Wu J., Crowe D.L. Telomere DNA damage signaling regulates cancer stem cell evolution, epithelial mesenchymal transition, and metastasis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:80139–80155. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flores I., Canela A., Vera E., Tejera A., Cotsarelis G., Blasco M.A. The longest telomeres: a general signature of adult stem cell compartments. Genes Dev. 2008;22:654–667. doi: 10.1101/gad.451008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flores I., Blasco M.A. The role of telomeres and telomerase in stem cell aging. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3826–3830. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rapoport A.P., Stadtmauer E.A., Binder-Scholl G.K., Goloubeva O., Vogl D.T., Lacey S.F., Badros A.Z., Garfall A., Weiss B., Finklestein J. NY-ESO-1-specific TCR-engineered T cells mediate sustained antigen-specific antitumor effects in myeloma. Nat. Med. 2015;21:914–921. doi: 10.1038/nm.3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramachandran I., Lowther D.E., Dryer-Minnerly R., Wang R., Fayngerts S., Nunez D., Betts G., Bath N., Tipping A.J., Melchiori L. Systemic and local immunity following adoptive transfer of NY-ESO-1 SPEAR T cells in synovial sarcoma. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2019;7:276. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0762-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson L.A., Morgan R.A., Dudley M.E., Cassard L., Yang J.C., Hughes M.S., Kammula U.S., Royal R.E., Sherry R.M., Wunderlich J.R. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood. 2009;114:535–546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan R.A., Chinnasamy N., Abate-Daga D., Gros A., Robbins P.F., Zheng Z., Dudley M.E., Feldman S.A., Yang J.C., Sherry R.M. Cancer regression and neurological toxicity following anti-MAGE-A3 TCR gene therapy. J. Immunother. 2013;36:133–151. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182829903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linette G.P., Stadtmauer E.A., Maus M.V., Rapoport A.P., Levine B.L., Emery L., Litzky L., Bagg A., Carreno B.M., Cimino P.J. Cardiovascular toxicity and titin cross-reactivity of affinity-enhanced T cells in myeloma and melanoma. Blood. 2013;122:863–871. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunsvig P.F., Aamdal S., Gjertsen M.K., Kvalheim G., Markowski-Grimsrud C.J., Sve I., Dyrhaug M., Trachsel S., Møller M., Eriksen J.A., Gaudernack G. Telomerase peptide vaccination: a phase I/II study in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2006;55:1553–1564. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0145-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inderberg-Suso E.M., Trachsel S., Lislerud K., Rasmussen A.M., Gaudernack G. Widespread CD4+ T-cell reactivity to novel hTERT epitopes following vaccination of cancer patients with a single hTERT peptide GV1001. OncoImmunology. 2012;1:670–686. doi: 10.4161/onci.20426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller S., Agnihotri S., Shoger K.E., Myers M.I., Smith N., Chaparala S., Villanueva C.R., Chattopadhyay A., Lee A.V., Butterfield L.H. Peptide vaccine immunotherapy biomarkers and response patterns in pediatric gliomas. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e98791. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.98791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castelli F.A., Buhot C., Sanson A., Zarour H., Pouvelle-Moratille S., Nonn C., Gahery-Ségard H., Guillet J.G., Ménez A., Georges B., Maillère B. HLA-DP4, the most frequent HLA II molecule, defines a new supertype of peptide-binding specificity. J. Immunol. 2002;169:6928–6934. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(1996). 12th International Histocompatibility Conference. Genetic diversity of HLA: functional and medical implications. Paris, France, June 9-12, 1996. Abstracts. Hum. Immunol. 47, 1–184. [PubMed]

- 22.Sidney J., Steen A., Moore C., Ngo S., Chung J., Peters B., Sette A. Five HLA-DP molecules frequently expressed in the worldwide human population share a common HLA supertypic binding specificity. J. Immunol. 2010;184:2492–2503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernhardt S.L., Gjertsen M.K., Trachsel S., Møller M., Eriksen J.A., Meo M., Buanes T., Gaudernack G. Telomerase peptide vaccination of patients with non-resectable pancreatic cancer: A dose escalating phase I/II study. Br. J. Cancer. 2006;95:1474–1482. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyte J.A., Gaudernack G., Faane A., Lislerud K., Inderberg E.M., Brunsvig P., Aamdal S., Kvalheim G., Wälchli S., Pule M. T-helper cell receptors from long-term survivors after telomerase cancer vaccination for use in adoptive cell therapy. OncoImmunology. 2016;5:e1249090. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1249090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kyte J.A., Fåne A., Pule M., Gaudernack G. Transient redirection of T cells for adoptive cell therapy with telomerase-specific T helper cell receptors isolated from long term survivors after cancer vaccination. OncoImmunology. 2019;8:e1565236. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1565236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vánky F., Stuber G., Willems J., Sjöwall K., Larsson B., Böök K., Ivert T., Péterffy A., Klein E. Importance of MHC antigen expression on solid tumors in the in vitro interaction with autologous blood lymphocytes. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 1988;27:213–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00205442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robila V., Ostankovitch M., Altrich-Vanlith M.L., Theos A.C., Drover S., Marks M.S., Restifo N., Engelhard V.H. MHC class II presentation of gp100 epitopes in melanoma cells requires the function of conventional endosomes and is influenced by melanosomes. J. Immunol. 2008;181:7843–7852. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inderberg E.M., Wälchli S. Long-term surviving cancer patients as a source of therapeutic TCR. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020;69:859–865. doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wälchli S., Løset G.Å., Kumari S., Johansen J.N., Yang W., Sandlie I., Olweus J. A practical approach to T-cell receptor cloning and expression. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norell H., Zhang Y., McCracken J., Martins da Palma T., Lesher A., Liu Y., Roszkowski J.J., Temple A., Callender G.G., Clay T. CD34-based enrichment of genetically engineered human T cells for clinical use results in dramatically enhanced tumor targeting. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2010;59:851–862. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0810-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rius C., Attaf M., Tungatt K., Bianchi V., Legut M., Bovay A., Donia M., Thor Straten P., Peakman M., Svane I.M. Peptide-MHC Class I Tetramers Can Fail To Detect Relevant Functional T Cell Clonotypes and Underestimate Antigen-Reactive T Cell Populations. J. Immunol. 2018;200:2263–2279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almåsbak H., Rian E., Hoel H.J., Pulè M., Wälchli S., Kvalheim G., Gaudernack G., Rasmussen A.M. Transiently redirected T cells for adoptive transfer. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:629–640. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.542461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stärck L., Popp K., Pircher H., Uckert W. Immunotherapy with TCR-redirected T cells: comparison of TCR-transduced and TCR-engineered hematopoietic stem cell-derived T cells. J. Immunol. 2014;192:206–213. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuball J., Dossett M.L., Wolfl M., Ho W.Y., Voss R.H., Fowler C., Greenberg P.D. Facilitating matched pairing and expression of TCR chains introduced into human T cells. Blood. 2007;109:2331–2338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Appay V., Zaunders J.J., Papagno L., Sutton J., Jaramillo A., Waters A., Easterbrook P., Grey P., Smith D., McMichael A.J. Characterization of CD4(+) CTLs ex vivo. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5954–5958. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oh D.Y., Kwek S.S., Raju S.S., Li T., McCarthy E., Chow E., Aran D., Ilano A., Pai C.S., Rancan C. Intratumoral CD4+ T Cells Mediate Anti-tumor Cytotoxicity in Human Bladder Cancer. Cell. 2020;181:1612–1625.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mensali N., Grenov A., Pati N.B., Dillard P., Myhre M.R., Gaudernack G., Kvalheim G., Inderberg E.M., Bakke O., Wälchli S. Antigen-delivery through invariant chain (CD74) boosts CD8 and CD4 T cell immunity. OncoImmunology. 2019;8:1558663. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1558663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeng G., Li Y., El-Gamil M., Sidney J., Sette A., Wang R.F., Rosenberg S.A., Robbins P.F. Generation of NY-ESO-1-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by a single peptide with dual MHC class I and class II specificities: a new strategy for vaccine design. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3630–3635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bénaroch P., Yilla M., Raposo G., Ito K., Miwa K., Geuze H.J., Ploegh H.L. How MHC class II molecules reach the endocytic pathway. EMBO J. 1995;14:37–49. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb06973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Köksal H., Dillard P., Josefsson S.E., Maggadottir S.M., Pollmann S., Fåne A., Blaker Y.N., Beiske K., Huse K., Kolstad A. Preclinical development of CD37CAR T-cell therapy for treatment of B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2019;3:1230–1243. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018029678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mensali N., Myhre M.R., Dillard P., Pollmann S., Gaudernack G., Kvalheim G., Wälchli S., Inderberg E.M. Preclinical assessment of transiently TCR redirected T cells for solid tumour immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2019;68:1235–1243. doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02356-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Broccoli D., Young J.W., de Lange T. Telomerase activity in normal and malignant hematopoietic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9082–9086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hiyama K., Hirai Y., Kyoizumi S., Akiyama M., Hiyama E., Piatyszek M.A., Shay J.W., Ishioka S., Yamakido M. Activation of telomerase in human lymphocytes and hematopoietic progenitor cells. J. Immunol. 1995;155:3711–3715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang J., Brameshuber M., Zeng X., Xie J., Li Q.J., Chien Y.H., Valitutti S., Davis M.M. A single peptide-major histocompatibility complex ligand triggers digital cytokine secretion in CD4(+) T cells. Immunity. 2013;39:846–857. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kohler M.E., Yang Y., Sepulveda G., Fry T.J. A Direct Comparison of the In Vivo Efficacy and in Vitro Signaling of Chimeric Antigen Receptors and Endogenous T Cell Receptors. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):4451. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andreatta M., Nielsen M. Characterizing the binding motifs of 11 common human HLA-DP and HLA-DQ molecules using NNAlign. Immunology. 2012;136:306–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wright W.E., Piatyszek M.A., Rainey W.E., Byrd W., Shay J.W. Telomerase activity in human germline and embryonic tissues and cells. Dev. Genet. 1996;18:173–179. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)18:2<173::AID-DVG10>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bendle G.M., Linnemann C., Hooijkaas A.I., Bies L., de Witte M.A., Jorritsma A., Kaiser A.D., Pouw N., Debets R., Kieback E. Lethal graft-versus-host disease in mouse models of T cell receptor gene therapy. Nat. Med. 2010;16:565–570, 1p, 570. doi: 10.1038/nm.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyazaki Y., Fujiwara H., Asai H., Ochi F., Ochi T., Azuma T., Ishida T., Okamoto S., Mineno J., Kuzushima K. Development of a novel redirected T-cell-based adoptive immunotherapy targeting human telomerase reverse transcriptase for adult T-cell leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:4894–4901. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-465971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandri S., Bobisse S., Moxley K., Lamolinara A., De Sanctis F., Boschi F., Sbarbati A., Fracasso G., Ferrarini G., Hendriks R.W. Feasibility of Telomerase-Specific Adoptive T-cell Therapy for B-cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Solid Malignancies. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2540–2551. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beatty G.L., Haas A.R., Maus M.V., Torigian D.A., Soulen M.C., Plesa G., Chew A., Zhao Y., Levine B.L., Albelda S.M. Mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor mRNA-engineered T cells induce anti-tumor activity in solid malignancies. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014;2:112–120. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tchou J., Zhao Y., Levine B.L., Zhang P.J., Davis M.M., Melenhorst J.J., Kulikovskaya I., Brennan A.L., Liu X., Lacey S.F. Safety and Efficacy of Intratumoral Injections of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cells in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017;5:1152–1161. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beatty G.L., O’Hara M.H., Lacey S.F., Torigian D.A., Nazimuddin F., Chen F., Kulikovskaya I.M., Soulen M.C., McGarvey M., Nelson A.M. Activity of Mesothelin-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Against Pancreatic Carcinoma Metastases in a Phase 1 Trial. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:29–32. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu Y.C., Parker L.L., Lu T., Zheng Z., Toomey M.A., White D.E., Yao X., Li Y.F., Robbins P.F., Feldman S.A. Treatment of Patients With Metastatic Cancer Using a Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II-Restricted T-Cell Receptor Targeting the Cancer Germline Antigen MAGE-A3. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:3322–3329. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolf B., Zimmermann S., Arber C., Irving M., Trueb L., Coukos G. Safety and Tolerability of Adoptive Cell Therapy in Cancer. Drug Saf. 2019;42:315–334. doi: 10.1007/s40264-018-0779-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garrido F., Cabrera T., Concha A., Glew S., Ruiz-Cabello F., Stern P.L. Natural history of HLA expression during tumour development. Immunol. Today. 1993;14:491–499. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90264-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matsuzaki J., Tsuji T., Luescher I.F., Shiku H., Mineno J., Okamoto S., Old L.J., Shrikant P., Gnjatic S., Odunsi K. Direct tumor recognition by a human CD4(+) T-cell subset potently mediates tumor growth inhibition and orchestrates anti-tumor immune responses. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14896. doi: 10.1038/srep14896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li K., Donaldson B., Young V., Ward V., Jackson C., Baird M., Young S. Adoptive cell therapy with CD4+ T helper 1 cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells enhances complete rejection of an established tumour, leading to generation of endogenous memory responses to non-targeted tumour epitopes. Clin. Transl. Immunology. 2017;6:e160. doi: 10.1038/cti.2017.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shklovskaya E., Terry A.M., Guy T.V., Buckley A., Bolton H.A., Zhu E., Holst J., Fazekas de St. Groth B. Tumour-specific CD4 T cells eradicate melanoma via indirect recognition of tumour-derived antigen. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2016;94:593–603. doi: 10.1038/icb.2016.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tateishi M., Saito I., Yamamoto K., Miyasaka N. Spontaneous production of Epstein-Barr virus by B lymphoblastoid cell lines obtained from patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Possible involvement of a novel strain of Epstein-Barr virus in disease pathogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:827–835. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kimura A., Dong R.P., Harada H., Sasazuki T. DNA typing of HLA class II genes in B-lymphoblastoid cell lines homozygous for HLA. Tissue Antigens. 1992;40:5–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1992.tb01951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walseng E., Köksal H., Sektioglu I.M., Fåne A., Skorstad G., Kvalheim G., Gaudernack G., Inderberg E.M., Wälchli S. A TCR-based Chimeric Antigen Receptor. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:10713. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11126-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Almåsbak H., Walseng E., Kristian A., Myhre M.R., Suso E.M., Munthe L.A., Andersen J.T., Wang M.Y., Kvalheim G., Gaudernack G., Kyte J.A. Inclusion of an IgG1-Fc spacer abrogates efficacy of CD19 CAR T cells in a xenograft mouse model. Gene Ther. 2015;22:391–403. doi: 10.1038/gt.2015.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inderberg E.M., Wälchli S., Myhre M.R., Trachsel S., Almåsbak H., Kvalheim G., Gaudernack G. T cell therapy targeting a public neoantigen in microsatellite instable colon cancer reduces in vivo tumor growth. OncoImmunology. 2017;6:e1302631. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1302631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.