Abstract

Objective:

Social support is associated with improved psychological distress in cancer patients. This study investigates the impact of social support on Chinese lung cancer patients' psychological distress and further clarifies the mediating role of perceived stress and coping style.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey study examined social support and psychological distress in 441 patients diagnosed with lung cancer from seven hospitals in Chongqing, China, between September 2018 and August 2019. Coping style and perceived stress were considered to be potential mediators of adjustment outcomes.

Results:

We found a detection rate of 17.7% for psychological distress among Chinese lung cancer patients. Social support was in significantly negative association with psychological distress, which was partially mediated by confrontation coping and perceived stress.

Conclusions:

Social support appears to contribute to ameliorate psychological distress by enhancing confrontation coping with cancer and enhancing perceived stress. There is a need for the development and evaluation of psychological intervention program to enhance the buffering effects of social support in lung cancer patients.

Keywords: Lung cancer, psychological distress, social support, perceived stress, coping style, structural equation model

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors.[1] It is estimated to have 2,100,000 new cases and 1,800,000 deaths of lung cancer in 2018 worldwide.[2] In China, lung cancer is also the leading cause of cancer-related death.[3] Cancer patients will suffer from several negative outcomes such as adverse symptoms and interruption of treatment, which will then cause psychological distress.[4] It is reported that lung cancer patients experience the highest prevalence of psychological distress[5] due to negative impact from several aspects such as poor 5-year survival rate of<40%.[6] One study reported that more than one-third of lung cancer patients experienced elevated depression before initiation of the treatment.[7] Lynch et al. found that 44.12% of 34 lung cancer patients reported psychological distress among.[8] Moreover, Chambers' study suggested that 51.0% of 151 participants reported elevated distress.[9] In China, the reported incidence of psychological distress among lung cancer patients was varied from 30.00% to 73.00%.[10]

Psychological distress has persistent negative impact on psychological health, compliance with treatment, and quality of life (QoL) among cancer patients,[11] and thus it has been defined as a risk factor of psychosomatic symptoms.[12,13,14] Social support has a buffering or protective effects on psychosocial adjustment.[15] Several studies have also determined the protective effects of social support on psychological distress.[16,17,18] Burnette and colleagues found a negative association between social support and psychological distress among 377 cancer caregivers.[16] Min et al. also demonstrated that social support was negatively associated with psychological distress.[19]

Coping is an individual's characteristic behavior for responding to stress, which can be categorized into three aspects including confrontation coping, accommodation coping, and avoidance coping.[20] Studies demonstrated that confrontation coping and accommodation coping benefits psychological adjustment as a positive coping style.[20,21] Whereas, patients who tend to adopt avoidance coping will experience more negative outcomes because they will not positively seek additional support sources to deal with difficulties.[21] Evidence suggested that psychological distress is closely associated with psychological adjustment as a strong predictor.[22] Coping style is, therefore, considered to be potentially related to psychological distress, and the association between coping style and psychological distress has been demonstrated.[23,24]

Stress is regarded as a state in which individual's regulatory capacity cannot meet the threshold of processing the environmental demands or mental strain.[25] Individual will conduct a subjective assessment for individual's degree of stress and ability of processing stress when experienced stress,[26] which is defined as perceived stress. Studies have demonstrated that perceived stress will influence individual psychological adjustment.[26,27] Individual will positively conduct psychological adjustment to ameliorate psychological distress when they perceived the threat from the higher stress, which has been demonstrated by published study.[27]

Based on the previous findings, we concluded that social support, coping style, and perceived stress is obviously the three major variables affecting psychological distress. In addition, more importantly, some studies have revealed that social support can directly influence the coping style[20,21,28,29] and perceived stress[30,31,32,33] among cancer patients. However, published studies only simply investigated the associative relationship between two variables, and the potential association of these three variables with psychological distress in lung cancer patients is not yet clear, which considerably limits practitioners to develop interventions for targeting social support. Hence, we performed this study to investigate the impact of social support on Chinese lung cancer patients' psychological distress and further clarify the role of perceived stress and coping style as mediators of effects.

Methods

The present study was conducted based on a descriptive and correlational design. The ethics commission of the Chongqing University Cancer Hospital reviewed and approved the study protocol (Approval No. CUCH_P20180225). Investigators informed all candidates the aims and procedures of the study in detail before starting the formal survey. All oral informed consents were obtained from patients before participating in the study. We reported all data in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for reporting observational studies.[34]

Sample and setting

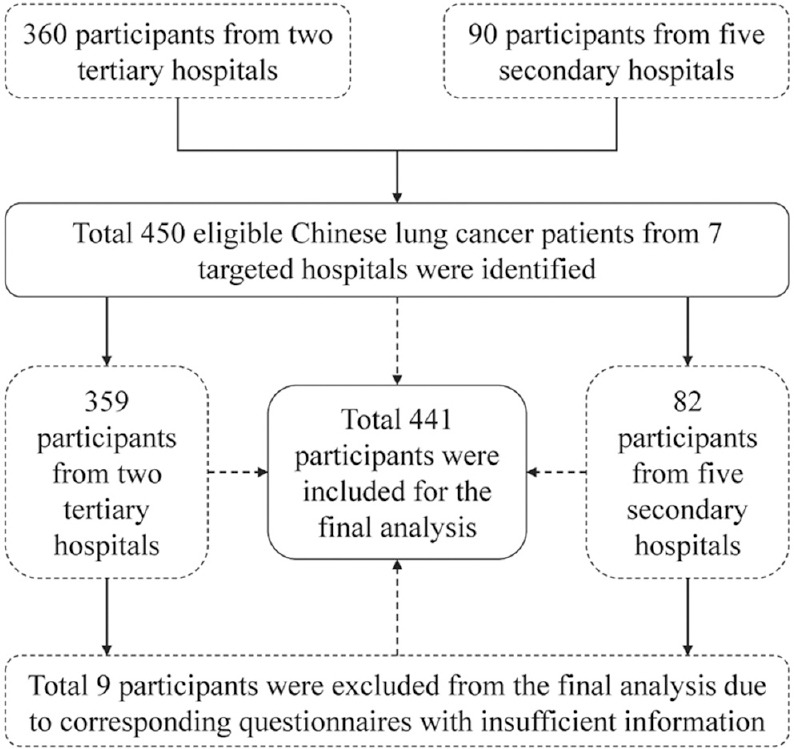

Eligible lung cancer patients were enrolled from seven hospitals including two tertiary hospitals and five secondary hospitals in Chongqing, China. After a pilot study tested the feasibility of the questionnaire survey, we conducted the formal survey. All questionnaires were independently completed by patients between September 2018 and August 2019. We calculated sample size according to the principle of minimum numbers needed to perform structural equation modeling (SEM).[35] Patients were enrolled if the following inclusion criteria were met: (1) lung cancer was established pathologically; (2) adults patients (18 years or older) who have independent ability of reading, understanding, and writing information; and (3) did not participate in other surveys which has similar study aims. We excluded patients with serious physical diseases, mental disorder, and consciousness disorder from this study. Finally, a total of 450 lung cancer patients were recruited in the investigation and 441 questionnaires were considered to meet the criteria of analysis, with an effective response rate of 98.0%. The process of participants' selection is delineated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The flow diagram of participants' selection

Instruments

Demographic information sheet

The demographic information sheet was developed by the leading investigator (X. T.). Potential demographic variables which may have impact on psychological distress were identified from published literature. We designed 12 demographic variables in this study finally, including age, gender, educational level, work status, marital status, residence, home income, family history (yes or no), smoking history (yes or no), drinking history (yes or no), surgery history (yes or no), pain, and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage.

Psychological distress

In this study, we used a distress thermometer (DT) to measure psychological distress. The DT is a single item with an 11-point scale (0 and 10 represents no distress and extreme distress, respectively) in a thermometer format.[13] Several studies have tested the psychometric properties of DT and confirmed the value of measuring psychological distress.[36,37,38] According to the criteria, patients will be defined to have clinically significant distress if a score of 4 or above was reported.[39,40] In China, an empirical study demonstrated that the optimal cutoff point of DT was also 4, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.885.[37]

Social support

In the preset study, we used the 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) to measure the level of social support from three aspects including family, friends, and significant others.[41] Eligible lung cancer patients were requested to rate each item on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree). The total score of the perceived social support ranges from 12 to 84 points. A previous study has tested the psychological properties of MSPSS and reported that the coefficient alpha values of subscales were ranging from 0.81 to 0.98.[42] The Chinese version of MSPSS has been validated[43] and thus was used to measure the level of perceived social support in our study. Reliability Cronbach's alpha was 0.90 in this study.

Coping style

We used a 20-item Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire (MCMQ), which rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 to 3,[44] in this study. The coping style questionnaire was divided into three subscales including confrontation coping (active coping), avoidance coping, and giving up coping (accommodation). Finally, the score of each subscale was calculated, and the higher score indicated that individual is more likely to adopt the corresponding coping style. The MCMQ has been validated in China scenario and then formed Chinese version of MCMQ.[45] Cronbach's alpha for each of the three subscales were higher than 0.65, except for avoidance coping (0.60). In the current study, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were 0.67, 0.68, and 0.74 for confrontation coping, avoidance coping, and giving up coping, respectively.

Perceived stress

In this study, we used the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), which was developed by Cohen et al.[46,47] to measure stress, which was evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 to 4. The total possible score was ranging from 0 to 40 points, and a higher score indicated a greater stress level. Cronbach's alpha was 0.84 at the instrument development stage. The Chinese version of PSS has been validated, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.619.[48] In our study, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.73.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were completed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Chicago, Illinois, USA) and IBM AMOS 21.0 (Chicago, Illinois, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patients' characteristics and their average score for psychological distress, social support, coping style, and perceived stress. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that the scores of psychological distress, social support, coping style, and perceived stress did not follow the normal distribution, so Spearman's rank correlation analyses were calculated to test the relationships among psychological distress, social support, coping style, and perceived stress. Bootstrap test was conducted to test a mediating effect of coping style or perceived stress in the relation of social support and psychological distress. We evaluated the overall model using the criteria of fit index. According to Schreiber,[49] the Chi-square (χ2) test value should not be statistically significant (P > 0.05), 1< χ2/degrees of freedom (df)<3, goodness of fit index (GFI) >0.90, adjusted GFI (AGFI) >0.90, comparative fit index (CFI) ≥0.90, incremental fit index (IFI) >0.90, normed fit index (NFI) >0.90, and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA)<0.05 (with 90% confidence interval [CI]). A P value of 0.05 was considered to represent statistical significance (two-tailed).

Results

Demographic characteristics and descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of 441 patients. A total of 315 (71.4%) patients were male. The age of majority of patients was more than 50 years (372 patients, 84.4%). A total of 127 (27.2%) patients graduated from primary school, 180 (40.8%) had junior middle school education, 84 (19.1%) had senior high school education, and 57 (12.9%) held a college degree or higher degree. Most patients did not attend work (198 patients, 44.9%) or retired from work (189 patients, 42.9%). 438 patients (99.3%) were married and 3 (0.7%) were divorced or widowed. 306 patients (69.4%) reside in the urban area. For the household income, 39 (8.8%) patients reported under ¥20,000; 123 (27.9%) made between ¥20,000 and ¥50,000; 192 (43.5%) made between ¥50,000 and ¥100,000; and 87 (19.8%) made more than ¥100,000. 54 (12.2%), 282 (63.9%), and 204 patients (46.3%) have family history, smoking history, and drinking history, respectively. 168 (38.1%) patients underwent surgery. Most patients experienced mild-to-severe pain (258 patients, 58.5%), and most patients were diagnosed at advanced stage (378 patients, 85.7%), which were defined as III and IV stage.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants (n=441)

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) | Z or χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 315 (71.4) | −0.479 | 0.632 |

| Female | 126 (28.6) | ||

| Age (year) | |||

| 18-39 | 12 (2.7) | 8.005 | 0.046 |

| 40-49 | 57 (12.9) | ||

| 50-59 | 141 (32.0) | ||

| ≥60 | 231 (52.4) | ||

| Educational level | |||

| Primary | 120 (27.2) | 8.891 | 0.031 |

| Junior high | 180 (40.8) | ||

| Senior high | 84 (19.1) | ||

| University | 57 (12.9) | ||

| Work status | |||

| Not working | 198 (44.9) | 6.560 | 0.038 |

| Working | 54 (12.2) | ||

| Retired | 189 (42.9) | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 438 (99.3) | 3.798 | 0.051 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 3 (0.7) | ||

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 306 (69.4) | −1.240 | 0.214 |

| Rural | 135 (30.6) | ||

| Household income (¥) | |||

| <20,000 | 39 (8.8) | 22.224 | <0.001 |

| 20,000-50,000 | 123 (27.9) | ||

| 50,000-100,000 | 192 (43.5) | ||

| >100,000 | 87 (19.8) | ||

| Family history | |||

| No | 387 (87.8) | −2.177 | 0.029 |

| Yes | 54 (12.2) | ||

| Smoking history | |||

| No | 159 (36.1) | −0.459 | 0.646 |

| Yes | 282 (63.9) | ||

| Drinking history | |||

| No | 237 (53.7) | −2.157 | 0.031 |

| Yes | 204 (46.3) | ||

| Surgery | |||

| No | 273 (61.9) | −1.102 | 0.270 |

| Yes | 168 (38.1) | ||

| Pain | |||

| No pain | 183 (41.5) | 7.323 | 0.062 |

| Mild | 174 (39.5) | ||

| Moderate | 81 (18.4) | ||

| Severe | 3 (0.06) | ||

| TNM stage | |||

| I | 42 (9.5) | 62.803 | <0.001 |

| II | 21 (4.8) | ||

| III | 48 (10.9) | ||

| IV | 330 (74.8) |

TNM: tumor-node-metastasis

Overall, the median score of psychological distress was 2 with an interquartile range of from 2 to 3. The medium score of social support, coping style, and perceived stress was 66 (61–70), 50 (48–52), and 20 (17–22), respectively. Among 441 lung cancer patients, 78 were detected to have a DT score of 4 or above, with a detection rate of 17.7%.

Relationships between psychological distress, social support, coping style, and perceived stress

Table 2 documents the results of correlation analyses of psychological distress, social support, coping style including confrontation coping, avoidance coping and giving up coping, and perceived stress. The results of the Spearman's rank correlation analyses showed that most variables are significantly correlated with one another other than the correlation between coping style and perceived stress. Moreover, avoidance coping and giving up coping were all not significantly correlated with psychological distress.

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlation coefficient of study variables (n=441)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological distress | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Perceived stress | 0.131** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Social support | −0.444** | 0.110* | 1 | ||||

| 4. Coping style | 0.113* | 0.067 | 0.096* | 1 | |||

| 5. Confrontation coping | 0.134** | 0.026 | 0.152** | 0.661** | 1 | ||

| 6. Avoidance coping | 0.026 | −0.012 | 0.093* | 0.624** | 0.121* | 1 | |

| 7. Giving up coping | −0.002 | 0.082 | −0.118* | 0.390** | −0.132** | 0.104* | 1 |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01

The mediating effect of coping style and perceived stress on the relationship between social support and psychological distress

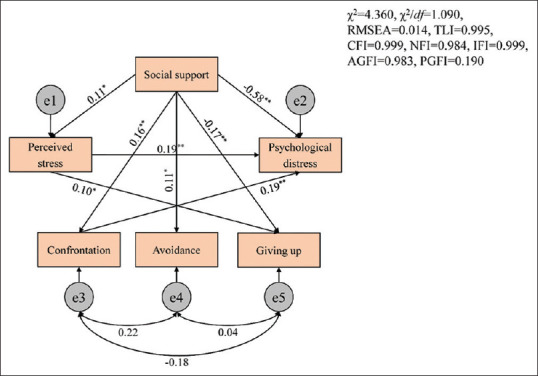

SEM with maximum likelihood was used to analyze the path correlations, which are presented in Table 3 and Figure 2. The results showed a better fitness between construct model and the data (χ2/df = 1.090, GFI = 0.997, AGFI = 0.983, CFI = 0.999, IFI = 0.999, NFI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.014 [90% CI, 0.000–0.075]).

Table 3.

Decomposition of standardized effects from the path model

| Variable of effect | Social support | Perceived | Confrontation coping | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confrontation coping | Avoidance coping | Giving up coping | Perceived stress | Psychological distress | Giving up coping | Psychological distress | Psychological distress | |

| Total effects | 0.155 | 0.113 | −0.164 | 0.110 | −0.524 | 0.096 | 0.192 | 0.191 |

| Direct effects | 0.155 | 0.113 | −0.175 | 0.110 | −0.575 | 0.096 | 0.192 | 0.191 |

| Indirect effects | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.051 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Figure 2.

A path diagram of direct and indirect influences of social support, perceived stress and coping style on psychological distress among Chinese lung cancer patients (n = 441). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

As illustrated, social support had significant direct effects on psychological distress (β = −0.58, P < 0.001), confrontation coping (β = 0.16, P < 0.001), avoidance coping (β = 0.11, P = 0.02), giving up coping (β = −0.17, P < 0.001), and perceived stress (β = 0.11, P = 0.02) among lung cancer patients. The direct pathways from perceived stress to giving up coping (β = 0.10, P = 0.04) and psychological distress (β = 0.19, P < 0.001) were all statistically significant. Meanwhile, the direct pathway from confrontation coping to psychological distress (β = 0.19, P < 0.001) was also statistically significant. The results of bias-corrected bootstrap method indicated that the indirect pathways between social support and psychological distress through confrontation coping or perceived stress were significant, respectively. The results from bootstrap test for significance of indirect pathways are summarized in Table 4. The results suggested that perceived stress or confrontation coping plays a mediating role in the relationship between social support and psychological distress.

Table 4.

Bias-corrected bootstrap test for all indirect pathways

| Pathway | Estimate | Bootstrap confidence | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological distress ← social support | −0.575 | −0.629-−0.523 | 0.001 |

| Confrontation copings ← social support | 0.155 | 0.071-0.240 | 0.005 |

| Perceived stress ← social support | 0.046 | 0.014-0.080 | 0.021 |

| Psychological distress ← confrontation coping | 0.191 | 0.123-0.262 | 0.001 |

| Psychological distress ← perceived stress | 0.192 | 0.134-0.258 | 0.001 |

Discussion

Main findings

The aim of the present study is to examine the impact of social support on psychological distress among Chinese lung cancer patients and determine whether coping style and perceived stress mediating the association between social support and psychological distress. The current study stemmed from a fact that the mechanism by which social support influences psychosocial distress among lung cancer patients remains unclear. In our study, only 17.7% of the analyzed patients reported clinically significant psychological distress, which was greatly lower than some previous findings.[10,37] However, there also are some studies found a relatively lower detection rate of psychological distress in Chinese lung cancer patients,[50,51] which were all consistent with our result. After checking the demographic information of all analyzed patients, we found that the vast majority of patients were at advanced stage and thus have greatly low expectation for treatment effectiveness and prognosis, which may be the major reason of causing relatively low detection rate of psychological distress.[37] Certainly, usage of DT for the measurement of psychological distress may be also a potentially important reason because this instrument is not just for cancer patients as a nonspecific type of tool.[37] More important is that most of the enrolled participants received psychological interventions when they were initially hospitalized to ward.[52] Moreover, patients will experience serious stigma when who were diagnosed with advanced lung cancer,[53] and therefore, patients tend to deliberately conceal their psychological distress.[50]

Social support has been identified as a buffering or protective source on distress and psychosocial adjustment.[15] A great deal of studies has established the importance of involving social support sources such as caregivers, spouses, or partners in educational and psychosocial intervention regimes.[54] In the current study, we found a directly negative correlation between social support and psychological distress among Chinese lung cancer patients, which was consistent with findings from previous studies.[16,55] Studies which were performed to investigate the influencing factors on psychological distress also consistently indicated that social support is one of the most important factors of reducing the severity of psychological distress.[56,57] One study focusing on breast cancer patients also suggested that higher level of social support was in association with higher benefit when a critical threshold of social support was reached.[58] Therefore, professional and nonprofessional social supports should be provided for lung cancer patients for the purpose of buffering the adverse consequences resulted from psychological distress and then improve the QoL.

The coping style is an important person's characteristic strategies to maintain or achieve healthy psychological status through improving environmental adaptability when patients experienced difficulties.[59] Different coping styles including confrontation coping, accommodation coping, and avoidance coping have impact on individual's emotional and mental health status.[23] Evidence indicated that patients with high level of positive attitude may have more expectation and confidence in addressing adverse challenge and vice versa.[60] In the present study, confrontation coping was defined to cope with the stressor positively.[29] We found confrontation coping mediating the relationship between social support and psychological distress, and confrontation coping was also in positive association with psychological distress. Evidence suggested that patients characterized by confrontation coping style were most likely to communicate with their physician for seeking disease- and treatment-related information[20] and then reduce the level of psychological distress. However, a previous systematic review concluded no significant association between engagement coping strategies and psychological distress.[24] These inconsistent results may be resulted from the different structure of psychological distress and coping style measurements, heterogeneity of the sample, or variation in statistical methods. Moreover, the association between negative coping style including avoidance coping and giving up coping (accommodation coping) and psychological distress was not statistically significant, which was also inconsistent with previous findings.[23,24] Thus, further investigation on the relationship between coping style and psychological distress in lung cancer patients should be conducted.

In addition, in this study, we also found that perceived stress partially mediated the relationship between social support and psychological distress, with a positive correlation between perceived stress and psychological distress, which was consistent with previous results.[27,61] Perceived stress will influence the person's psychological adjustment as a positive source of coping diseases, and we therefore assumed that perceived stress will influence psychological distress because psychological distress is a strong predictor of psychological adjustment.[22] Interestingly, a study investigating the relationship among perceived stress, coping style, and psychological distress in Chinese physicians demonstrated our hypothesis.[62] Moreover, Segrin et al. also found that stress can predict psychological distress in breast cancer survivors and their family caregivers.[63] Hence, it is critical to emphasize the role of enhancing the level of perceived stress when interpreting the buffering effects of social support on psychological distress. Moreover, psychological intervention programs for involving elements of buffering perceived stress should be developed to enhance the protective effects of social support on psychological distress.

Limitations

Although several valuable findings were identified in the present study, we must acknowledge some limitations which may have adverse impact on the conclusions. First and foremost is that the nature of cross-sectional survey design limits the ability of establishing causality between the proposed variables. And thus, further study with longitudinal design will be necessary to prospectively clear the mechanism of social support in buffering the adverse results from psychological distress. Second, we used convenience sampling method to enroll potentially eligible patients, and thus the sample is not representative. Further investigation with random sampling method should be designed. Third, we assessed psychological distress, social support, coping style, and perceived stress using self-reported questionnaires in the present study. Hence, the results may be inflated due to subjective bias from participants and investigators. Additional studies considering physiological assessment and ecological momentary assessment should be performed.

Conclusions

The minority of Chinese lung cancer patients experienced psychological distress at a clinically significant level. Perceived stress and confrontation coping mediated the protective effects of social support on psychological distress.

Implications for practice

This study enhanced our understanding on the association among social support, coping style, perceived stress, and psychological distress in lung cancer patients. From our current findings, practitioners can enhance the benefits of social support programs through strengthening confrontation coping and perceived stress and then reduce the adverse consequences resulted from psychological distress.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was granted by the Chongqing Science and Technology Commission Project, China (Grant Nos. cstc2018jscx-msybX0030, cstc2018jcyjAX0737s).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors also gratefully acknowledge the supervisors of the hospitals and the 441 lung cancer patients who volunteered to participate in the study, as well as the experts and members of the group for their help and advice.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu S, Chen Q, Guo L, Cao X, Sun X, Chen W, et al. Incidence and mortality of lung cancer in China, 2008-2012. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018;30:580–7. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2018.06.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroenke K, Johns SA, Theobald D, Wu J, Tu W. Somatic symptoms in cancer patients trajectory over 12 months and impact on functional status and disability. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:765–73. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1578-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WE, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: Proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (Eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4488–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch J, Goodhart F, Saunders Y, O'Connor SJ. Screening for psychological distress in patients with lung cancer: Results of a clinical audit evaluating the use of the patient Distress Thermometer. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0799-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambers SK, Baade P, Youl P, Aitken J, Occhipinti S, Vinod S, et al. Psychological distress and quality of life in lung cancer: The role of health-related stigma, illness appraisals and social constraints. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1569–77. doi: 10.1002/pon.3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pi YP, Tian X, Tang L, Shi B, Chen WQ. Research status of mindfulness-based stress reduction for psychological distress in cancer patients. J Clin Pathol Res. 2020;40:480–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akizuki N, Akechi T, Nakanishi T, Yoshikawa E, Okamura M, Nakano T, et al. Development of a brief screening interview for adjustment disorders and major depression in patients with cancer. Cancer. 2003;97:2605–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gundelach A, Henry B. Cancer-related psychological distress: A concept analysis. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:630–4. doi: 10.1188/16.CJON.630-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riba MB, Donovan KA, Andersen B, Braun I, Breitbart WS, Brewer BW, et al. Distress management, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:1229–49. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rana M, Kanatas A, Herzberg PY, Khoschdell M, Kokemueller H, Gellrich NC, et al. Prospective study of the influence of psychological and medical factors on quality of life and severity of symptoms among patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;53:364–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz U, Schwarzer R. Long-term effects of spousal support on coping with cancer after surgery. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2004;23:716–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnette D, Duci V, Dhembo E. Psychological distress, social support, and quality of life among cancer caregivers in Albania. Psychooncology. 2017;26:779–86. doi: 10.1002/pon.4081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teixeira RJ, Pereira MG. Psychological morbidity, burden, and the mediating effect of social support in adult children caregivers of oncological patients undergoing chemotherapy. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1587–93. doi: 10.1002/pon.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demirtepe-Saygili D, Bozo O. Perceived social support as a moderator of the relationship between caregiver well-being indicators and psychological symptoms. J Health Psychol. 2011;16:1091–100. doi: 10.1177/1359105311399486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Min JA, Yoon S, Lee CU, Chae JH, Lee C, Song KY, et al. Psychological resilience contributes to low emotional distress in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:2469–76. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1807-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geng Z, Ogbolu Y, Wang J, Hinds PS, Qian H, Yuan C. Gauging the effects of self-efficacy, social support, and coping style on self-management behaviors in Chinese cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41:E1–10. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo RZ, Zhang S, Liu YH. Short report: Relationships among resilience, social support, coping style and posttraumatic growth in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation caregivers. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25:389–95. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2019.1659985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groarke A, Curtis R, Kerin M. Global stress predicts both positive and negative emotional adjustment at diagnosis and post-surgery in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:177–85. doi: 10.1002/pon.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Cao C. The relationship between family history of cancer, coping style and psychological distress. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30:507–10. doi: 10.12669/pjms.303.4634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris N, Moghaddam N, Tickle A, Biswas S. The relationship between coping style and psychological distress in people with head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2018;27:734–47. doi: 10.1002/pon.4509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Yang Y, Zhang R, Yao K, Liu Z. The mediating role of mental adjustment in the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms in hematological cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J, Jang M. Stress, social support, and sexual adjustment in married female patients with breast cancer in Korea. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2020;7:28–35. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_31_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Segrin C, Badger TA, Sikorskii A, Pasvogel A, Weihs K, Lopez AM, et al. Longitudinal dyadic interdependence in psychological distress among Latinas with breast cancer and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:2735–43. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han Y, Hu D, Liu Y, Caihong Lu, Luo Z, Zhao J, et al. Coping styles and social support among depressed Chinese family caregivers of patients with esophageal cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:571–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomita M, Takahashi M, Tagaya N, Kakuta M, Kai I, Muto T. Structural equation modeling of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and psychosocial factors in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2017;26:1198–204. doi: 10.1002/pon.4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costa AL, Heitkemper MM, Alencar GP, Damiani LP, Silva RM, Jarrett ME. social support is a predictor of lower stress and higher quality of life and resilience in Brazilian patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40:352–60. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haugland T, Wahl AK, Hofoss D, DeVon HA. Association between general self-efficacy, social support, cancer-related stress and physical health-related quality of life: A path model study in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:11. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0413-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeung NC, Lu Q. Perceived stress as a mediator between social support and posttraumatic growth among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41:53–61. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou ES, Penedo FJ, Lewis JE, Rasheed M, Traeger L, Lechner S, et al. Perceived stress mediates the effects of social support on health-related quality of life among men treated for localized prostate cancer. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69:587–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg (London, England) 2014;12:1495–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tinsley HE, Tinsley DJ. Uses of factor analysis in counseling psychology research. J Couns Psychol. 1987;34:414–24. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bui QU, Ostir GV, Kuo YF, Freeman J, Goodwin JS. Relationship of depression to patient satisfaction: Findings from the barriers to breast cancer study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;89:23–8. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-1005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong J, Wei Z, Wang W. Preoperative psychological distress, coping and quality of life in Chinese patients with newly diagnosed gastric cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:2439–47. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kornblith AB, Herndon JE, 2nd, Zuckerman E, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, Cooper MR, et al. Social support as a buffer to the psychological impact of stressful life events in women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2001;91:443–54. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010115)91:2<443::aid-cncr1020>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donovan KA, Grassi L, McGinty HL, Jacobsen PB. Validation of the distress thermometer worldwide: State of the science. Psychooncology. 2014;23:241–50. doi: 10.1002/pon.3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang LL, Zhang YN, Pang Y, Zhang HW, Song LL. Validation and reliability of distress thermometer in chinese cancer patients. Chin J Cancer Res. 2011;23:54–8. doi: 10.1007/s11670-011-0054-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Personal Asses. 1988;52:30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55:610–7. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang J, Li S, Zheng Y. Predictors of depression in Chinese community-dwelling people with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:1295–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feifel H, Strack S. Coping with conflict situations: Middle-aged and elderly men. Psychol Aging. 1989;4:26–33. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen XH, Jiang JQ. Report on application of Chinese version of MCMQ in 701 patients. Chin J Behav Med Sci. 2000;9:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Mosher SW. The perceived stress scale: Factor structure and relation to depression symptoms in a psychiatric sample. J Psychopathol Behav Asses. 1992;14:247–57. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuan LX, Lin N. Research on factor structure of perceived stress scale in Chinese college students (in Chinese) J Guangdong Educ Institute. 2009;29:45–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schreiber JB. Update to core reporting practices in structural equation modeling. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13:634–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang M, Xie SP, Yang X. Study of psychological distress and relative influencing factors analysis of lung cancer patients before receiving radiotherapy. Chin J General Practice. 2018;16:488–91. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang HY, Wu L, Liu Y. Adverse psychological status and corresponding influencing factors in lung cancer patients. Chin J Public Health Eng. 2019;18:713–5. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang ZL, Chen YM, Tang L, Yang RM, Yuan WX, Jiang YQ. The clinical practice of dynamic monitoring and individualized intervention of mental suffering cancer patients (in Chinese) J Kunming Med Univ. 2015;36:109–11. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maguire R, Lewis L, Kotronoulas G, McPhelim J, Milroy R, Cataldo J. Lung cancer stigma: A concept with consequences for patients. Cancer Rep (Hoboken) 2019;2:e1201. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Sutton L, Dalton J, Baucom D, Pope MS, et al. Partner-guided cancer pain management at the end of life: A preliminary study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matzka M, Mayer H, Köck-Hódi S, Moses-Passini C, Dubey C, Jahn P, et al. Relationship between resilience, psychological distress and physical activity in cancer patients: A cross-sectional observation study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen Y, Zhang J, Bu QY, Liu CX. A longitudinal study of psychological distress and its related factors in patients with breast cancer. Chin Nurs Manag. 2018;18:617–22. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang C, Nie LT, Guo M, Yin XM, Zhang N, Wang GC. Relationship between hope and quality of life in lung cancer patients-the mediating effect of social support. J Nurs Training. 2018;33:2038–42. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mallinckrodt B, Armer JM, Heppner PP. A threshold model of social support, adjustment, and distress after breast cancer treatment. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59:150–60. doi: 10.1037/a0026549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Danhauer SC, Case LD, Tedeschi R, Russell G, Vishnevsky T, Triplett K, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic growth in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2676–83. doi: 10.1002/pon.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He F, Cao R, Feng Z, Guan H, Peng J. The impacts of dispositional optimism and psychological resilience on the subjective well-being of burn patients: A structural equation modelling analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wan SY. The mediating effects of perceived stress on the relation between mindfulness and psychological distress among breast cancer patients. Guide China Med. 2020;18:107–8. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Y, Wang P. Perceived stress and psychological distress among chinese physicians: The mediating role of coping style. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e15950. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Segrin C, Badger TA, Sikorskii A, Crane TE, Pace TW. A dyadic analysis of stress processes in Latinas with breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychooncology. 2018;27:838–46. doi: 10.1002/pon.4580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]