Abstract

Purpose

The aim of our work is to evaluate the correlation of two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) radiomics and metabolic features of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with tumour diameter, staging, and metabolic tumour volume (MTV).

Material and methods

Thirty-three patients with HCC were studied using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography with computed tomography (18F [FDG] PET/CT). The tumours were segmented from the PET images after CT correction. Metabolic parameters and 35 radiomics features were compared using 2D and 3D modes. The metabolic parameters and tumour morphology were compared using 2 different types of software. Tumour heterogeneity was studied in both metabolic parameters and radiomics features. Finally, the correlation between the metabolic and radiomics features in 3D mode, as well as tumour morphology and staging according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging were studied.

Results

Most of the metabolic parameters and radiomics features are statically stable through the 2D and 3D modes. Most of the 3D mode features show a correlation with metabolic parameters; the total lesion glycolysis (TLG) shows the highest correlation, with a Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) of 0.9776. Also, the grey level run length matrix/run length non-uniformity (GLRLM_RLNU) from radiomics features exhibits a correlation with a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.9733. Maximum tumour diameter is correlated with TLG and GLRLM_RLNU, with rs equal to 0.7461 and 0.7143, respectively. Regarding AJCC staging, some features show a medium but prognostic correlation. In the case of 2D-mode features, all metabolic and radiomics features show no significant correlation with MTV, AJCC staging, and tumour maximum diameter.

Conclusions

Most of the normal metabolic parameters and radiomics features are statistically stable through the 3D and 2D modes. 3D radiomics features are significantly correlated with tumour volume, maximum diameter, and staging. Conversely, 2D features have negligible correlation with the same parameters. Therefore, 3D mode features are preferable and can accurately evaluate tumour heterogeneity.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, FDG-PET-CT, heterogeneity, radiomics

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver malignancy and a leading cause of cancer-related death [1]. HCC is an extremely heterogeneous disease, and intratumour heterogeneity is a recognised fact within each specific tumour. Heterogeneity could involve molecular, morphological, and immunohistochemical characteristics.

The pathologic classification of HCC is based on the degree of cellular difference. The cancer tissue of two different histological grades may be present in the same tumour. Intratumor heterogeneity of HCC has a prognostic value [2].

It is hard to survey intra-tumoural heterogeneity with conventional testing or biopsy because it is difficult to cover the full degree of phenotypic or hereditary variety inside a tumour. Imaging modalities such as X-ray, ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) show a good and non-intrusive technique for evaluating the heterogeneity inside a tumour. A limitation that applies to all imaging modalities is that the image interpretation is based on a visual process. However, there are features within each image that may not be appreciated readily by the naked eye [3].

Recently, there has been extensive effort in the medical imaging community to obtain correlations between imaging features and tumour heterogeneity; an approximation for this concern is radiomics, which is a new technique that depends on the extraction of more data from biomedical images that cannot be investigated by the naked eye. This term was used for first time by Lambin et al., who investigated quantitative image analysis such as texture analysis to assess tumour heterogeneity [4]. Several studies demonstrated a promising role for radiomics in cancer diagnosis, staging, and treatment assessment [5,6].

No standardisation has yet been developed for radiomics. Radiomics features are variable through many factors such as scanners, test-retest, observers, segmentation methods, and image reconstruction [7-9]. In addition, the mode of imaging may have an influence on radiomics. Texture analysis was performed in 2D mode. However, the advancements in 3D information acquisition and the high spatial resolution allow better capture of tissue properties [10]. Few studies have looked at the differences between radiomics or textural features in 3D and 2D modes utilising MRI or CT [11,12]. Ortiz-Ramón et al. introduced a radiomics approach on MRI of cancer lesions including lung cancer and melanoma [13].

The aim of our work was to evaluate the correlation of 2D and 3D radiomics and metabolic features of hepatocellular carcinoma with tumour diameter, staging, and metabolic tumour volume.

Material and methods

Patients

This retrospective study included 33 consecutive patients with HCC proven by histopathology (29 males and 4 females) between November 2016 and April 2018. Patients were referred to our department primarily to investigate the extra-hepatic disease before starting an appropriate management plan. The average age was 57.7 years (range 39-77). Disease stage was assigned by a tumour board committee and based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer staging manual 2017 [14]. The primary HCC was diagnosed by histopathology, the nodal and metastatic disease was established with reference to dedicated imaging, histopathology/histocytology of suspicious lesions when indicated to change line of management as well as the clinical assessment and follow-up. After staging, patients were referred to a multidisciplinary HCC panel including an oncologist, surgeon, hepatologist, and interventional radiologist. The management plan was implemented based on the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system and its updates, which incorporates tumour morphology, liver function, and health performance status along with treatment-dependent variables [15,16].

The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB), and informed consent was waved.

Imaging techniques

The study was performed using a PET/CT scanner (Siemens Biograph 128-mCT). The patients were positioned in the PET/CT scanner approximately after injection of FDG intravenously the patients injected according to their weight by 0.1 mCi or 3.7 MBq for each kg. A non-contrast CT scan was acquired from the base of the skull to the upper high region and used for attenuation correction. Images size was 200 × 200 pixels; slice thickness = 1 mm.

Image processing and analysis

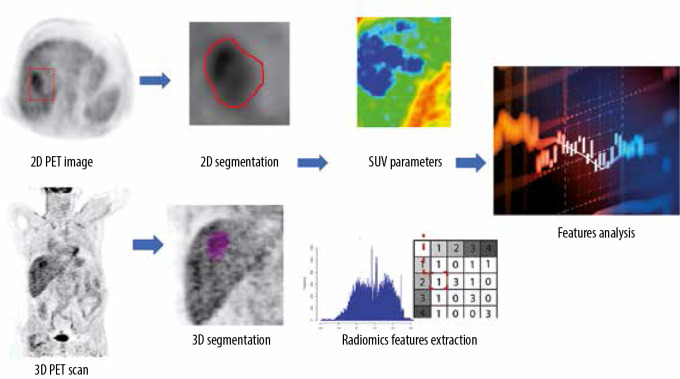

Imaging interpretation and analysis were performed and revised by a qualified radiologist with 15 years’ experience in reading PET/CT. The tumours were segmented from the PET images after CT correction, using a semiautomatic method by ITK-snap software version 3.6.0 in 2D mode. In 3D mode the Pet scan segmented directly using a semiautomatic method in LIFEx package version 4.0.0 (https://www.lifexsoft.org/) [17]. The metabolic parameters and texture features were extracted using the LIFEx package. Figure 1 shows a diagram of the workflow of radiomics extraction, and Figure 2 shows a PET scan before and after delineation in the LIFEx package.

Figure 1.

The workflow of standardised uptake value (SUV) parameters and radiomics features extraction

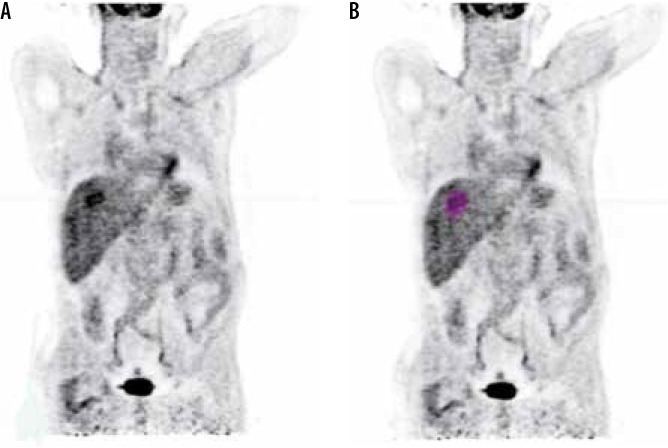

Figure 2.

Coronal positron-emission tomography (PET) images of a 59-year-old male with hepatocellular carcinoma before (A) and after (B) delineation of the liver lesion using LIFEx package

Metabolic parameters

The standardised uptake value (SUV) is defined as the tissue concentration of tracer, as measured by a PET scanner, divided by the activity injected divided by body weight [18]. There are many parameters related to SUV that can be useful for cancer diagnosis and staging.

SUVmax: The maximum SUV value at the region of interest, which is the commonly used SUV clinically; however, some works show that another SUV factor can give a global view for tumours, such as metabolic tumour volume (MTV) and TLG.

SUVmean: The average SUV value at the region of in-terest.

SUVmin: The minimum SUV value at the region of interest.

Metabolic tumour volume (MTV): Measures the active volume in ml.

Total lesion glycolysis (TLG): Is defined as the product of SUVmean and MTV [19].

Intra-tumour heterogeneity

The 18F-FDG uptake heterogeneity was estimated using the coefficient of variation (COV), defined as the ratio between the standard deviation of SUV values and the mean SUV value within the delineated MTV [20].

SUV parameters are referred to as usual metabolic parameters; MTV and TLG are referred to as global metabolic parameters [21].

Texture features

Thirty-five radiomics features are studied. Histogram indices derived after determination of bin width; the grey level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) takes into consideration the arrangements of pairs of voxels to calculate textural indices, and the neighbourhood grey-level different matrix (NGLDM) corresponds to the distinction of grey-level between one voxel and its 26 neighbours in 3 dimensions. The grey-level run length matrix (GLRLM) provides the scale of consistent runs for every grey-level. The grey-level zone length matrix (GLZLM) provides data on the scale of consistent zones for every grey-level in 3 dimensions.

Table 1 summarises all of the different features included in this study. More details about the radiomics features used in this study can be found at: https://lifexsoft.org/index.php/resources/19-texture/radiomicfeatures?filter_tag[0]=.

Table 1.

Summary of the features included in this study

| Feature name | Feature index | Feature type |

|---|---|---|

| The minimum SUV | SUVmin (SUV) | SUV/normal metabolic parameters |

| The average SUV | SUVmean (SUV) | SUV/normal metabolic parameters |

| The standard deviation of SUV | SUVstd (SUV) | SUV/normal metabolic parameters |

| The maximum SUV | SUVmax (SUV) | SUV/normal metabolic parameters |

| The coefficient of variation | SUV(std/mean) | SUV/normal metabolic parameters |

| Total lesion glycolysis | TLG (ml) | Global metabolic parameters |

| Metabolic tumour volume | (MTV) Volume (ml) | Global metabolic parameters |

| Skewness | HISTO_Skewness | Histogram indices |

| Kurtosis | HISTO_Kurtosis | Histogram indices |

| Entropy | HISTO_Entropy_log10 | Histogram indices |

| Entropy | HISTO_Entropy_log2 | Histogram indices |

| Energy | HISTO_Energy | Histogram indices |

| Homogeneity | GLCM_Homogeneity | The grey level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) |

| Energy | GLCM_Energy | GLCM |

| Contrast | GLCM_Contrast | GLCM |

| Correlation | GLCM_Correlation | GLCM |

| Entropy | GLCM_Entropy_log10 | GLCM |

| Entropy | GLCM_Entropy_log2 | GLCM |

| Dissimilarity | GLCM_Dissimilarity | GLCM |

| Short-run emphasis | GLRLM_SRE | The grey-level run length matrix (GLRLM) |

| Long-run emphasis | GLRLM_LRE | GLRLM |

| Low grey-level run emphasis | GLRLM_LGRE | GLRLM |

| High grey-level run emphasis | GLRLM_HGRE | GLRLM |

| Short-run low grey-level emphasis | GLRLM_SRLGE | GLRLM |

| Short-run high grey-level emphasis | GLRLM_SRHGE | GLRLM |

| Long-run low grey-level emphasis | GLRLM_LRLGE | GLRLM |

| Long-run high grey-level emphasis | GLRLM_LRHGE | GLRLM |

| Grey-level non-uniformity for run | GLRLM_GLNU | GLRLM |

| Run length non-uniformity | GLRLM_RLNU | GLRLM |

| Run percentage | GLRLM_RP | GLRLM |

| Coarseness | NGLDM_Coarseness | The neighbourhood grey-level different matrix (NGLDM) |

| Contrast | NGLDM_Contrast | NGLDM |

| Busyness | NGLDM_Busyness | NGLDM |

| Short-zone emphasis | GLZLM_SZE | The grey-level zone length matrix (GLZLM) |

| Long-zone emphasis | GLZLM_LZE | GLZLM |

| Low grey-level zone emphasis | GLZLM_LGZE | GLZLM |

| High grey-level zone emphasis | GLZLM_HGZE | GLZLM |

| Short-zone low grey-level emphasis | GLZLM_SZLGE | GLZLM |

| Short-zone high grey-level emphasis | GLZLM_SZHGE | GLZLM |

| Long-zone low grey-level emphasis | GLZLM_LZLGE | GLZLM |

| Long-zone high grey-level emphasis | GLZLM_LZHGE | GLZLM |

| Grey-level non-uniformity for zone | GLZLM_GLNU | GLZLM |

| Zone length non-uniformity | GLZLM_ZLNU | GLZLM |

| Zone percentage | GLZLM_ZP | GLZLM |

Statistical analysis

A paired t-test was used to obtain the differences between the metabolic and radiomics features in 3D and 2D mode, and then the Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated to study the relationship between metabolic and radiomics features and the tumour staging, diameter, and metabolic volume. All statistical tests were calculated using Origin lab software version 6 and IBM-SPSS version 19.

Results

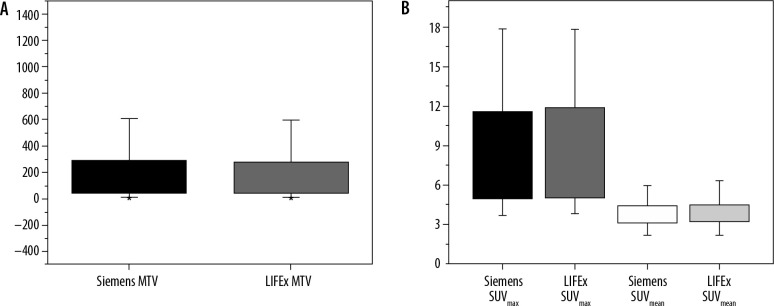

SUV values (SUVmax, SUVmean, and MTV) were compared between the LIFEx package and an approved software: Siemens Syngo trueD. An independent t-test for the values in both software calculated to measure the differences between the values. SUVmean was the most stable feature between the two software packages, with a significance level (ρ) = 0.91, where MTV and SUVmax gave (ρ) = 0.87 and 0.61, respectively. There was no significant difference between the two software packages, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Show a box plot of metabolic parameters in Siemens vs. LIFEx software. A) Metabolic tumour volume (MTV) in both software. B) A SUVmax and SUVmean in each software

The variations between SUV parameters, except SUVmin, and 20 radiomics features were statistically stable in 3D and 2D modes, as shown in Table 2. Most features had ρ-values higher than 0.05; the most stable in the SUV feature was SUVmean, with ρ = 0.588, while in radiomics features the most stable were GLCM_Contrast and GLZLM_LGZE, with ρ = 0.89 and 0.82, respectively. Around 15 features were significantly different between the 2 modes; the most significant was GLZLM_ZP, with ρ ≤ 0.001.

Table 2.

The results of paired t-test for metabolic and radiomics features in both 2D and 3D modes; the cells signed with (*) show the significant difference in features between 3D and 2D

| Features | t | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| SUV(std/mean) | 1.377 | 0.1782 |

| SUVmin (SUV) | –5.557 | < 0.0001* |

| SUVmean (SUV) | –0.546 | 0.588 |

| SUVstd (SUV) | 0.767 | 0.4484 |

| SUVmax (SUV) | 1.278 | 0.2104 |

| HISTO_Skewness | 0.550 | 0.5858 |

| HISTO_Kurtosis | 0.697 | 0.4908 |

| HISTO_Entropy_log10 | 1.491 | 0.1458 |

| HISTO_Entropy_log2 | 1.491 | 0.1458 |

| HISTO_Energy | 1.955 | 0.0594 |

| GLCM_Homogeneity | 0.754 | 0.4562 |

| GLCM_Energy | –1.536 | 0.1345 |

| GLCM_Contrast | –0.144 | 0.8861 |

| GLCM_Correlation | 3.594 | 0.0011* |

| GLCM_Entropy_log10 | 2.489 | 0.0182* |

| GLCM_Entropy_log2 | 2.489 | 0.0182* |

| GLCM_Dissimilarity | –0.277 | 0.7833 |

| GLRLM_SRE | –1.099 | 0.2800 |

| GLRLM_LRE | 0.475 | 0.6377 |

| GLRLM_LGRE | –0.742 | 0.4633 |

| GLRLM_HGRE | –0.28 | 0.7816 |

| GLRLM_SRLGE | –0.575 | 0.5691 |

| GLRLM_SRHGE | –0.338 | 0.7372 |

| GLRLM_LRLGE | –0.952 | 0.3485 |

| GLRLM_LRHGE | 0.586 | 0.5620 |

| GLRLM_GLNU | 5.845 | < 0.0001* |

| GLRLM_RLNU | 4.837 | < 0.0001* |

| GLRLM_RP | –0.681 | 0.5007 |

| NGLDM_Coarseness | –10.763 | < 0.001 |

| NGLDM_Contrast | –2.763 | 0.0094* |

| NGLDM_Busyness | 4.705 | < 0.0001* |

| GLZLM_SZE | –11.597 | < 0.0001* |

| GLZLM_LZE | 3.020 | 0.0049* |

| GLZLM_LGZE | –0.225 | 0.8234 |

| GLZLM_HGZE | 0.401 | 0.6908 |

| GLZLM_SZLGE | –1.928 | 0.0628 |

| GLZLM_SZHGE | –1.526 | 0.0628 |

| GLZLM_LZLGE | 2.243 | 0.0319* |

| GLZLM_LZHGE | 3.089 | 0.0041* |

| GLZLM_GLNU | 4.430 | 0.0001* |

| GLZLM_ZLNU | 2.586 | 0.0145* |

| GLZLM_ZP | –12.754 | < 0.0001* |

Spearman correlation coefficients for both 3D and 2D features with tumour maximum diameter, tumour staging, and tumour metabolic volume are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Most of 3D mode features showed high correlation with metabolic tumour volume, as shown in Table 3; the strongest correlation of metabolic parameters was found with TLG, with rs = 0.98, and from radiomics features it was GLRLM_RLNU, with rs = 0.97. Considering the 2D mode features, there was no significant correlation between the SUV as well as radiomics features and MTV, AJCC staging, or tumour maximum diameter, where all spearman correlation coefficients were less than 0.3, as shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Spearman correlation coefficient rs and ρ-values for metabolic and radiomics features in 3D mode with tumour metabolic volume, tumour staging, and maximum diameter; cells signed with (*) are medium correlation where cells signed with (**) are high correlation

| 3D features | Diameter (rs) | Diameter (ρ) | AJCC staging (rs) | AJCC staging (ρ) | MTV (rs) | MTV (ρ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUVmean/std | 0.5019 | 0.0029** | 0.3242 | 0.0657* | 0.6090 | 0.0002** |

| SUVmin (SUV) | –0.5439 | 0.0011** | –0.2844 | 0.1087 | –0.5505 | 0.0009** |

| SUVmean (SUV) | 0.3246 | 0.0654* | 0.4177 | 0.0156* | 0.5114 | 0.0024** |

| _SUVstd (SUV) | 0.4400 | 0.0104* | 0.3509 | 0.0453* | 0.6123 | 0.0002** |

| SUVmax (SUV) | 0.4882 | 0.0040* | 0.4108 | 0.0176* | 0.6928 | < 0.0001** |

| SUVpeak 1 ml | 0.4903 | 0.0038 | 0.3799 | 0.0292* | 0.6801 | < 0.0001** |

| TLG (ml) | 0.7461 | < 0.0001** | 0.4556 | 0.0077* | 0.9776 | < 0.0001** |

| HISTO_Skewness | 0.3281 | 0.0623* | 0.1334 | 0.4592 | 0.4679 | 0.006* |

| HISTO_Kurtosis | 0.2966 | 0.0937 | –0.0407 | 0.8222 | 0.3382 | 0.0542* |

| HISTO_Entropy_log10 | 0.4500 | 0.0086* | 0.3554 | 0.0424* | 0.6230 | 0.0001** |

| HISTO_Energy | –0.4323 | 0.0120* | –0.3452 | 0.0491* | –0.5946 | 0.0003** |

| Sphericity (only for 3D ROI) | –0.2573 | 0.1483 | –0.4117 | 0.0173* | –0.5003 | 0.0030** |

| SHAPE_Compacity ROI (nZ > 1) | 0.7363 | < 0.0001** | 0.3128 | 0.0764* | 0.9542 | < 0.0001** |

| GLCM_Homogeneity | –0.2991 | 0.0908 | –0.3118 | 0.0773* | –0.4602 | 0.007* |

| GLCM_Energy | –0.4090 | 0.0181* | –0.3576 | 0.041* | –0.5872 | 0.0003** |

| GLCM_Contrast | 0.3269 | 0.0633* | 0.3358 | 0.0561* | 0.4773 | 0.0050* |

| GLCM_Correlation | 0.6277 | < 0.0001** | 0.2483 | 0.1635 | 0.7614 | < 0.0001** |

| GLCM_Entropy_log10 | 0.4323 | 0.0120* | 0.3805 | 0.0289* | 0.6096 | 0.0002** |

| GLCM_Dissimilarity | 0.3145 | 0.0746* | 0.3340 | 0.0575* | 0.4766 | 0.0050* |

| GLRLM_SRE | 0.1169 | 0.5190 | 0.2701 | 0.1285 | 0.2012 | 0.2615 |

| GLRLM_LRE | –0.0875 | 0.6283 | –0.2556 | 0.1511 | –0.1310 | 0.4674 |

| GLRLM_LGRE | –0.1273 | 0.4802 | –0.2668 | 0.1333 | –0.2707 | 0.1276 |

| GLRLM_HGRE | 0.3460 | 0.0486* | 0.4115 | 0.0174* | 0.5394 | 0.0012** |

| GLRLM_SRLGE | –0.1521 | 0.3982 | –0.324 | 0.0658* | –0.3185 | 0.0708* |

| GLRLM_SRHGE | 0.3314 | 0.0596* | 0.4218 | 0.0145* | 0.5124 | 0.0023** |

| GLRLM_LRLGE | –0.0087 | 0.9617 | –0.1133 | 0.5303 | –0.0745 | 0.6802 |

| GLRLM_LRHGE | 0.3883 | 0.0256* | 0.4538 | 0.0080* | 0.6380 | < 0.0001** |

| GLRLM_GLNU | 0.6943 | < 0.0001** | 0.2672 | 0.1328 | 0.8930 | < 0.0001** |

| GLRLM_RLNU | 0.7143 | < 0.0001** | 0.4324 | 0.0120* | 0.9733 | < 0.0001** |

| GLRLM_RP | 0.1074 | 0.5519 | 0.2334 | 0.1911 | 0.1852 | 0.3023 |

| NGLDM_Coarseness | –0.711 | < 0.0001** | –0.3993 | 0.0213* | –0.9652 | < 0.0001** |

| NGLDM_Contrast | –0.0054 | 0.9764 | 0.181 | 0.3135 | 0.0896 | 0.6201 |

| NGLDM_Busyness | 0.3197 | 0.0697* | 0.0937 | 0.6041 | 0.4676 | 0.0061* |

| GLZLM_SZE | 0.3018 | 0.0878* | 0.46 | 0.0071* | 0.3061 | 0.0831* |

| GLZLM_LZE | 0.1057 | 0.5581 | –0.1296 | 0.4722 | 0.1407 | 0.4348 |

| GLZLM_LGZE | –0.311 | 0.0781* | –0.4422 | 0.0100* | –0.5043 | 0.0028** |

| GLZLM_HGZE | 0.4122 | 0.0171* | 0.4149 | 0.0163* | 0.6243 | 0.0001** |

| GLZLM_SZLGE | –0.3756 | 0.0312* | –0.3683 | 0.0350* | –0.6233 | 0.0001** |

| GLZLM_SZHGE | 0.4042 | 0.0197* | 0.4110 | 0.0175* | 0.5929 | 0.0003** |

| GLZLM_LZLGE | 0.1910 | 0.2869 | –0.0546 | 0.7627 | 0.2176 | 0.2239 |

| GLZLM_LZHGE | 0.1793 | 0.3180 | –0.1036 | 0.5660 | 0.2654 | 0.1355 |

| GLZLM_GLNU | 0.6590 | < 0.0001** | 0.4915 | 0.0037* | 0.9181 | < 0.0001** |

| GLZLM_ZLNU | 0.6412 | < 0.0001** | 0.4607 | 0.0070* | 0.8590 | < 0.0001** |

| GLZLM_ZP | 0.1273 | 0.4802 | 0.2988 | 0.0912 | 0.1888 | 0.2926 |

Table 4.

Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) and p-values for metabolic and radiomics features in 2D mode with tumour metabolic volume, tumour staging, and maximum diameter

| 2D features | Diameter (rs) | Diameter (p) | AJCC staging (rs) | AJCC satging (p) | MTV (rs) | MTV (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUVmean/std | –0.0368 | 0.8389 | 0.0310 | 0.8638 | –0.0842 | 0.6412 |

| SUVmin (SUV) | 0.1086 | 0.5475 | –0.0033 | 0.9856 | 0.1889 | 0.2925 |

| SUVmean (SUV) | 0.0746 | 0.6798 | 0.0969 | 0.5915 | 0.1300 | 0.4708 |

| _SUVstd (SUV) | –0.0666 | 0.7127 | 0.0209 | 0.9082 | –0.0154 | 0.9323 |

| SUVmax (SUV) | 0.0698 | 0.6996 | 0.0830 | 0.6400 | 0.1183 | 0.5119 |

| HISTO_Skewness | 0.0740 | 0.6825 | 0.0924 | 0.6090 | 0.0568 | 0.7535 |

| HISTO_Kurtosis | 0.1302 | 0.4703 | –0.1278 | 0.4785 | 0.0739 | 0.6829 |

| HISTO_Entropy_log10 | –0.0746 | 0.6798 | 0.0162 | 0.9289 | –0.0294 | 0.8709 |

| HISTO_Energy | 0.0289 | 0.8730 | –0.0172 | 0.9241 | 0.0137 | 0.9397 |

| GLCM_Homogeneity | 0.0612 | 0.7350 | –0.0419 | 0.8168 | 0.0160 | 0.9294 |

| GLCM_Energy | 0.0256 | 0.8876 | –0.0064 | 0.9720 | 0.0160 | 0.9294 |

| GLCM_Contrast | –0.1024 | 0.5707 | 0.0592 | 0.7436 | –0.0475 | 0.7931 |

| GLCM_Correlation | 0.0492 | 0.7857 | –0.0007 | 0.9968 | 0.0150 | 0.9338 |

| GLCM_Entropy_log10 | –0.0385 | 0.8316 | –0.0167 | 0.9265 | –0.0053 | 0.9764 |

| GLCM_Dissimilarity | –0.0920 | 0.6105 | 0.0494 | 0.7849 | –0.0331 | 0.8549 |

| GLRLM_SRE | –0.0669 | 0.7114 | –0.0719 | 0.6910 | –0.0104 | 0.9544 |

| GLRLM_LRE | 0.1066 | 0.5550 | –0.0719 | 0.6910 | 0.0468 | 0.7959 |

| GLRLM_LGRE | –0.1384 | 0.4425 | –0.077 | 0.6703 | –0.1842 | 0.3049 |

| GLRLM_HGRE | 0.0815 | 0.6522 | 0.0782 | 0.6650 | 0.1257 | 0.4859 |

| GLRLM_SRLGE | –0.1663 | 0.3550 | –0.0824 | 0.6484 | –0.2276 | 0.2027 |

| GLRLM_SRHGE | 0.0882 | 0.6256 | 0.0868 | 0.6311 | 0.1270 | 0.4812 |

| GLRLM_LRLGE | –0.0728 | 0.6873 | –0.0866 | 0.6320 | –0.1217 | 0.5000 |

| GLRLM_LRHGE | 0.1755 | 0.3286 | 0.0902 | 0.6180 | 0.2704 | 0.1280 |

| GLRLM_GLNU | 0.1494 | 0.4066 | –0.2200 | 0.2180 | 0.0956 | 0.5967 |

| GLRLM_RLNU | 0.1389 | 0.4409 | –0.0381 | 0.8330 | 0.0929 | 0.6070 |

| GLRLM_RP | –0.0793 | 0.6609 | 0.0713 | 0.6932 | –0.0237 | 0.8957 |

| NGLDM_Coarseness | –0.2543 | 0.1532 | –0.0378 | 0.8347 | –0.2129 | 0.2342 |

| NGLDM_Contrast | –0.1594 | 0.3754 | 0.0084 | 0.9632 | –0.1080 | 0.5498 |

| NGLDM_Busyness | 0.1300 | 0.4709 | 0.0336 | 0.8528 | 0.1003 | 0.5787 |

| GLZLM_SZE | –0.0612 | 0.7350 | 0.0080 | 0.9640 | –0.0642 | 0.7227 |

| GLZLM_LZE | 0.0766 | 0.6717 | –0.0944 | 0.6013 | 0.0254 | 0.8884 |

| GLZLM_LGZE | –0.1466 | 0.4157 | –0.0920 | 0.6105 | –0.1999 | 0.2647 |

| GLZLM_HGZE | 0.0863 | 0.6329 | 0.1106 | 0.5402 | 0.1337 | 0.4582 |

| GLZLM_SZLGE | –0.1464 | 0.4163 | –0.0871 | 0.6290 | –0.2086 | 0.2441 |

| GLZLM_SZHGE | 0.0447 | 0.8050 | 0.0986 | 0.5852 | 0.0889 | 0.6230 |

| GLZLM_LZLGE | 0 | 1 | –0.0958 | 0.5957 | –0.0428 | 0.8131 |

| GLZLM_LZHGE | 0.2553 | 0.1516 | 0.0425 | 0.8144 | 0.2707 | 0.1275 |

| GLZLM_GLNU | 0.1516 | 0.3525 | –0.1690 | 0.3471 | 0.0789 | 0.6626 |

| GLZLM_ZLNU | 0.0617 | 0.7329 | –0.0134 | 0.9409 | 0.0328 | 0.8564 |

| GLZLM_ZP | –0.0795 | 0.6602 | 0.0801 | 0.6579 | –0.0428 | 0.8131 |

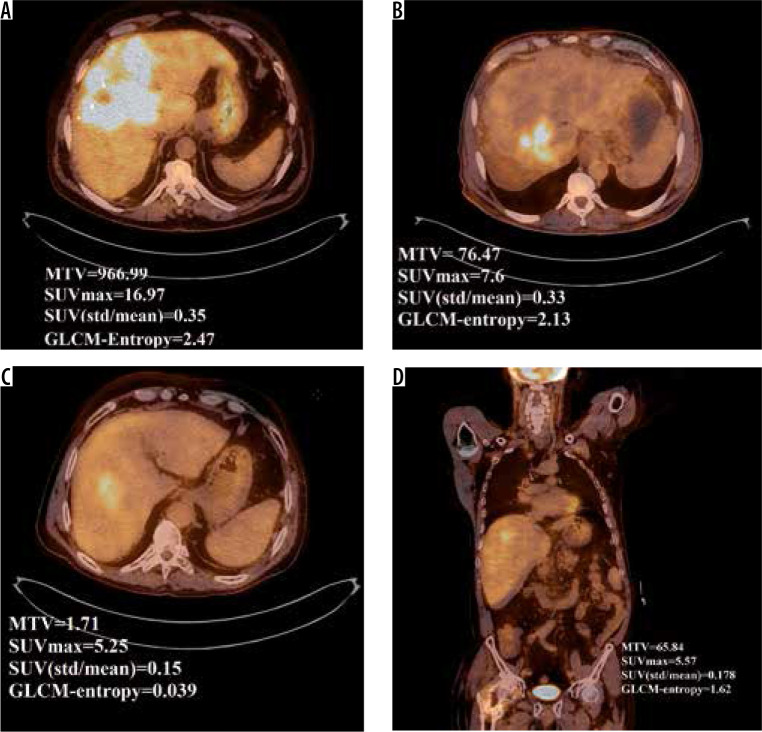

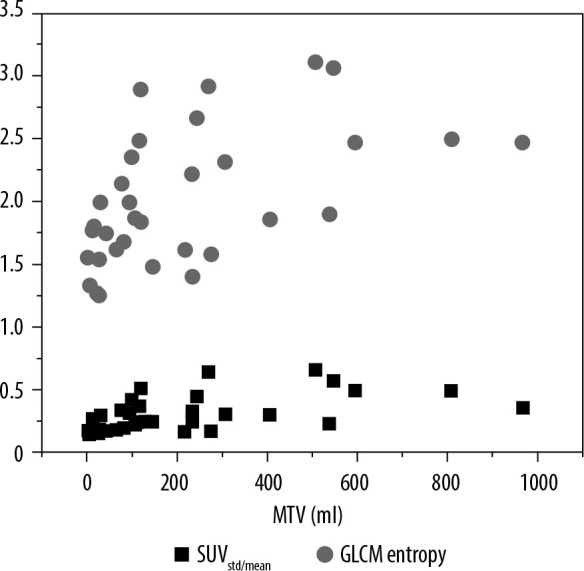

To compare HCC tumour heterogeneity through uptake heterogeneity and radiomics features, the relationship between SUV(std/mean) and GLCM entropy with metabolic tumour volume is shown in Figure 4. The18F-FDG uptake heterogeneity coefficient SUV(std/mean) mean value = 0.304 ± 0.14, and GLCM-entropy radiomics feature mean = 2.016 ± 0.523.

Figure 4.

The correlation of SUVstd/mean and GLCM entropy with metabolic tumour volume (MTV)

Discussion

Several studies have demonstrated agreement on the usefulness of 18F[FDG]-PET/CT in defining HCC, staging, and treatment assessment; furthermore, some authors reported a high correlation with histopathology results [22-25]. Our study showed that the addition of radiomics features to PET images can provide more information about cancer structure and intratumour heterogeneity.

Comparing the SUV parameters generated by LIFEx, which is an open-source software, with Siemens Syngovia TrueD (commercial software), there was no significant difference between the two software programs. Arian et al. reported differences in SUV parameters through four platforms [26]. On the other hand, Kenny et al. compared SUV parameters through 14 software programs using three phantoms calibrated on 3 PET/CT scanners, and agreement found in some software included Siemens TrueD [27].

In the current work we found that SUVmean and SUV(std/mean) were smaller in 3D than in 2D mode, whereas, SUVmax was little higher in 2D mode than in 3D mode. Kocabaş et al. reported that SUVmax was variable between 3D and 2D modes and the values were smaller in 3D mode [28]. In the current work we found that SUVmean and SUV(std/mean) were smaller in 3D than in 2D mode, whereas SUVmax was a little larger in 2D mode than in 3D mode.

Our study showed a strong correlation of 3D mode features, especially TLG and GLRLM_RLNU with MTV. This strong correlation could be explained by the fact that TLG and GLRLM_RLNU voxel values are not absolute SUV values and depend on the lesion volume. Therefore, it showed a strong correlation with MTV. The lowest correlation of MTV was found with GLRLM_LRLGE. A similar correlation between the same feature and MTV was found by Vicente et al. in the case of breast cancer dual time acquisition PET [29]. GLRLM_LRLGE measures the roughness of the images, which increases when the texture is dominated by long runs that have low grey levels; hence, it may not correlate with volume.

In this study, TLG from metabolic parameters and GLRLM_RLNU from radiomics features demonstrated a strong correlation with maximum diameter of the lesion, with rs = 0.75 and 0.71, respectively. Hatt et al. reported that MTV has a close correlation with tumour diameter in lung cancer [20]. So, the same correlation can be found in the case of TLG because it depends on MTV, and as we mentioned before: RLNU is correlated to MTV and to the diameter. Regarding AJCC staging, some features showed a medium correlation with metabolic and radiomics features; the strongest was GLZLM_GLNU, with rs = 0.4915. Van Go et al. reported a similar correlation between some radiomics features of [18F] (FDG-PET) images and AJCC staging for non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) [21].

Considering the 2D mode features, there was no significant correlation between the SUV as well as radiomics features and MTV, AJCC staging, or tumour maximum diameter. This may be because the spatial resolution of PET images is low, which does not give strong texture information in small areas [18].

It has been shown that tumour heterogeneity increases with larger tumour volume, as reported by Hatt et al. and Brooks and Grigsby [20,30]. In our cohort we found that some HCC tumours may be more heterogeneous in both uptake and radiomics value without being large in volume, as shown in Figure 5. SUVmax is the commonest parameter used for follow-up; however, it suffers from the fact that it is not correlated to tumour volume and tumour heterogeneity. Figure 5 demonstrates a tumour with high SUVmax, but its textural analysis is less heterogeneous than another tumour with lower SUVmax value. Hatt et al. suggested that GLCM entropy with MTV is lower in the volume range less than 50 cm3 [31]; this finding is in agreement with our study.

Figure 5.

Comparison between two hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tumour parameters. (A) and (B) compare uptake heterogeneity coefficient and GLCM- entropy of two HCC tumours. Although (B) have a higher metabolic tumour volume, it is more homogenous than tumour (A). (C) and (D) compare the parameters for the same patient in 2D and 3D, respectively

Limitations of our study include the relatively small sample size, restricted number of radiomics features, and lack of comparison of the findings with other clinical information such histopathology results. The clinical course of the disease and liver functions have not been compared with radiomics. However, the main focus of this investigation was to improve the performance of FDG-PET/CT in the diagnosis and characterisation of HCC, which will be extended in our future works to incorporate radiomics in clinical practice. Furthermore, there was medical value to our finding: we discovered the best mode for HCC radiomics for use in our future studies.

Conclusions

The metabolic parameters and radiomics features are variable between 3D and 2D modes. Some SUV parameters and radiomics features are statically stable through 3D and 2D modes. Image analysis in 3D radiomics features is significantly correlated with tumour volume, maximum diameter, and staging, whereas all features in 2D exhibit no correlation. Therefore, in comprehensive studies of intra-tumoral structure, 3D mode features can accurately evaluate tumour heterogeneity.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Balogh J, Iii Dv, Asham Eh, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma : a review. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2016; 3: 41-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammoud GM, Ibdah JA. Are we getting closer to understanding intratumor heterogeneity in hepatocellular carcinoma? Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2016; 5: 188-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davnall F, Yip CSP, Ljungqvist G, et al. Assessment of tumor heterogeneity: an emerging imaging tool for clinical practice? Insights Imaging 2012; 3: 573-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambin P, Rios-velazquez E, Leijenaar R. Radiomics: extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48: 441-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aerts HJWL, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RTH, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coroller TP, Sc M, Grossmann P, et al. CT-based radiomic signature predicts distant metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma. Radiother Oncol 2016; 114: 345-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackin D, Fave X, Zhang L, et al. Measuring CT scanner variability of radiomics features. Invest Radiol 2015; 50: 757-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parmar C, Leijenaar RTH, Grossmann P, et al. Radiomic feature clusters and prognostic signatures specific for lung and head and neck cancer. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altazi BA, Zhang GG, Fernandez DC, et al. Reproducibility of F18-FDG PET radiomic features for different cervical tumor segmentation methods, gray-level discretization, and reconstruction algorithms. J Appl Clin Med Phys 2017; 18: 32-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Depeursinge A, Foncubierta-Rodriguez A, Van De Ville D, Müller H. Three-dimensional solid texture analysis in biomedical imaging: review and opportunities. Medical Image Analysis 2014; 18: 176-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahmoud-Ghoneim D, Toussaint G, Constans JM, De Certaines JD. Three dimensional texture analysis in MRI: A preliminary evaluation in gliomas. Magn Reson Imaging 2003; 21: 983-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lubner MG, Stabo N, Lubner SJ, et al. CT textural analysis of hepatic metastatic colorectal cancer: pre-treatment tumor heterogeneity correlates with pathology and clinical outcomes. Abdom Imaging 2015; 40: 2331-2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz-Ramon R, Larroza A, Arana E, Moratal D. A radiomics evaluation of 2D and 3D MRI texture features to classify brain metastases from lung cancer and melanoma. Proc Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2017; 2017: 493-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amin M, Edge S, Greene F, et al. (eds.). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer International Publishing; 2017; 287-293. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2018; 391: 1301-1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis 1999; 19: 329-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nioche C, Orlhac F, Boughdad S, et al. Lifex: a freeware for radiomic feature calculation in multimodality imaging to accelerate advances in the characterization of tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Res 2018; 78: 4786-4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keyes JW. SUV: standard uptake or silly useless value? J Nucl Med 1995; 36: 1836-1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larson SM, Erdi Y, Akhurst T, et al. Tumor treatment response based on visual and quantitative changes in global tumor glycolysis using PET-FDG imaging. The visual response score and the change in total lesion glycolysis. Clin Positron Imaging 1999; 2: 159-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatt M, Cheze-le Rest C, van Baardwijk A, et al. Impact of tumor size and tracer uptake heterogeneity in 18F-FDG PET and CT non-small cell lung cancer tumor delineation. J Nucl Med 2011; 52: 1690-1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Gómez López O, García Vicente AM, Honguero Martínez AF, et al. Heterogeneity in [18 F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography of non–small cell lung carcinoma and its relationship to metabolic parameters and pathologic staging. Mol Imaging 2014; 13; doi: 10.2310/7290.2014.00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torizuka T, Tamaki N, Inokuma T, et al. In vivo assessment of glucose metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma with FDG-PET. J Nucl Med 1995; 36: 1811-1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolfort RM, Papillion PW, Turnage RH, et al. Role of FDG-PET in the evaluation and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma with comparison of tumor size, AFP level, and histologic grade. Int Surg 2010; 95: 67-75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitamura K, Hatano E, Higashi T, et al. Preoperative FDG-PET predicts recurrence patterns in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 156-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong A, Yu H, Wang Y, et al. FDG PET/CT and enhanced CT imaging of tumor heterogeneity in hepatocellular carcinoma: imaging-pathologic correlation. Clin Nucl Med 2014; 39: 808-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arain Z, Lodge M, Wahl R. A comparison of SUV parameters across four commercial software platforms. J Nucl Med 2015; 56 (Suppl 3): 580.25698781 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenny B. SUV reproducibility on different reporting platforms What is SUV? BNMS spring meeting, Birmingham: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kocabas B, Yapar AF, Reyhan M, et al. Comparison of standardized uptake values obtained from 18F fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging performed with 2d and 3D modes in oncological cases. Diagnostic Interv Radiol 2012; 126-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Vicente AM, Molina D, Pérez-Beteta J, et al. Textural features and SUV-based variables assessed by dual time point 18F-FDG PET/CT in locally advanced breast cancer. Ann Nucl Med 2017; 31: 726-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brooks FJ, Grigsby PW. The effect of small tumor volumes on studies of intratumoral heterogeneity of tracer uptake. J Nucl Med 2013; 55: 37-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatt M, Majdoub M, Vallières M, et al. 18F-FDG PET uptake characterization through texture analysis: investigating the complementary nature of heterogeneity and functional tumor volume in a multi-cancer site patient cohort. J Nucl Med 2015; 56: 38-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]