Certain E. coli found in the human gut have tumorigenic properties and appear to cause colorectal cancer in humans1. Li et al. recently suggested the isolate precolibactin-969 (1) and its deacylation product, colibactin-645 (2), underlie this genotoxic phenotype2 (Fig. 1). This author is concerned that the structures of 1 and 2, and their mechanism of action, are not in agreement with a model that has been developed in the literature and do not account for several significant findings. Given the importance of colibactin biochemistry to the problem of colorectal cancer, and to our nascent understanding of how the microbiome contributes to health and disease more broadly, it is crucial to quickly address possible misconceptions in this field, which this letter aims to do in detail below.

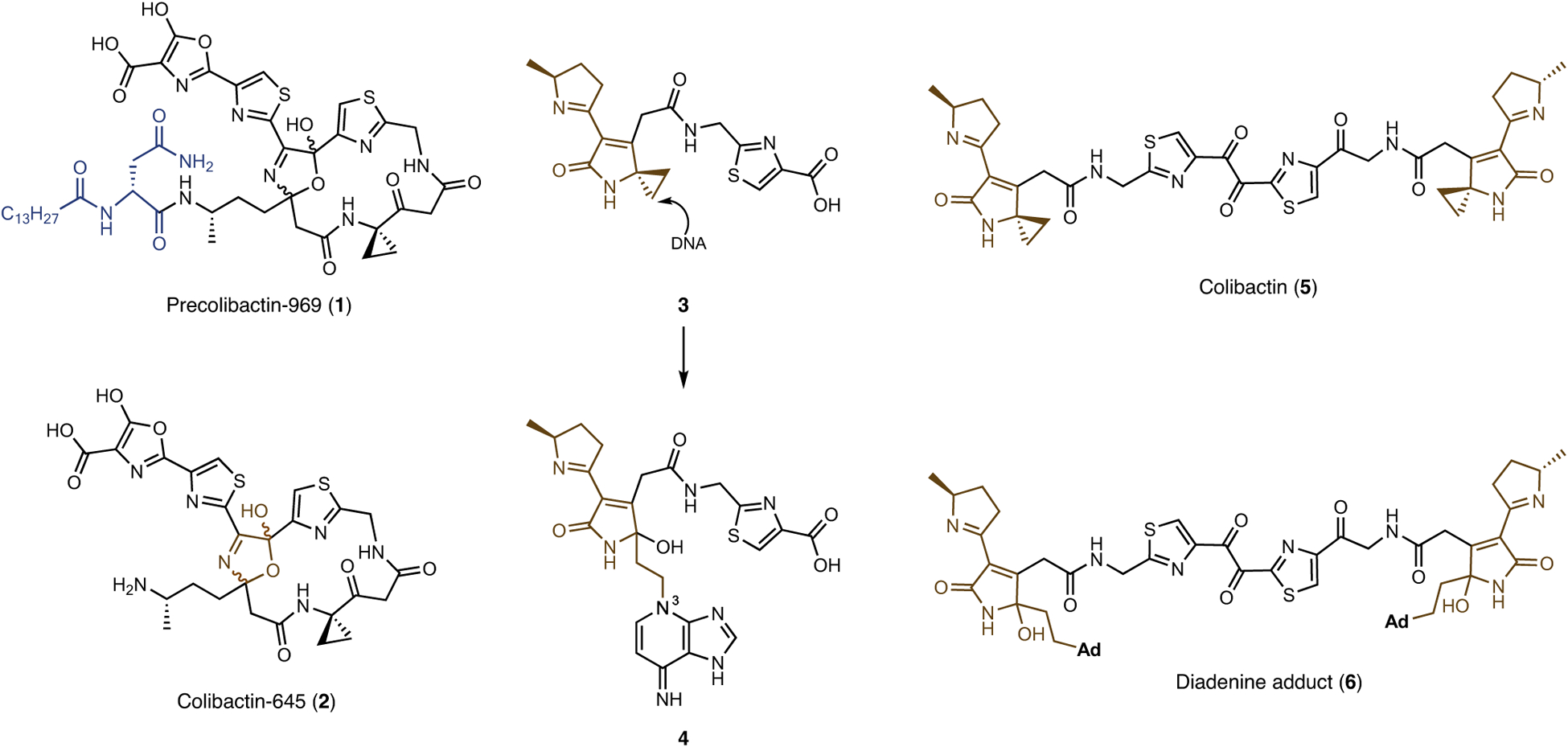

Fig. 1 |. Structures of precolibactin-969 (1), colibactin-645 (2) and other structures discussed in this manuscript.

The adenine adduct 4 was identified in the digestion mixture of DNA treated with clb+ E. coli and in colonic epithelial cells of mice colonized by the bacteria. The adduct 4 forms by nucleotide addition to the electrophilic cyclopropane 3 and/or clb products of greater complexity. Alternative structure 5 advanced for colibactin. The diadenine adduct 6 was identified in linearized pUC19 DNA and cellular genomic DNA that had been exposed to clb+ E. coli.

The carcinogenic mechanism of the bacteria is likely related to their ability to produce a molecule — colibactin — that induces DNA double-strand breaks3 and interstrand crosslinks4 in eukaryotic genomic DNA. The biosynthesis of colibactin is encoded in the clb (or pks) biosynthetic gene cluster3. Studies indicate all 16 biosynthetic enzymes in the gene cluster are required to produce the colibactin genotoxin linked to the disease3. Using well-established assays5 Li et al. showed that in the presence of a copper(ii) co-factor, both precolibactin-969 (1) and colibactin-645 (2) induce DNA single-strand breaks and double-strand breaks in DNA. DNA double-strand break repair was activated in HeLa cells treated with colibactin-645 (2), but not precolibactin-969 (1). Li et al. write ‘Precolibactin-969… requires all the components of the… assembly line for its biosynthesis’, suggesting they have identified the complete product of the clb biosynthetic gene cluster, namely, colibactin. However, this conclusion is called into question by the literature outlined below.

First, Li et al. claim that colibactin-645 (2) requires all of the biosynthetic enzymes in the clb biosynthetic gene cluster. This claim is incorrect. Precolibactin-969 (1) was isolated from a triple mutant lacking ClbQ, a thioesterase demonstrated in two separate studies to be required for genotoxic effects3,4.

Second, Li et al. do not address a study that established clb+ E. coli induce DNA interstrand crosslinks in linearized plasmid DNA and in cellular genomic DNA4. This mode of DNA damage is dependent on ClbQ and was shown to correlate with activation of the DNA damage response4.

Third, the study by Li et al. is not in agreement with the prevailing model for colibactin genotoxicity, which involves DNA alkylation by nucleotide addition to an electrophilic cyclopropane6–9 (for example, 3→4). The resistance enzyme ClbS (ref.10), which is encoded in the clb biosynthetic gene cluster, catalyses hydrolytic opening of the cyclopropane in substrates such as 3 (ref.11). Li et al. speculate that the genotoxic effects of the bacteria may arise from mixtures of metabolites with different modes of action. However, the addition of ClbS to cultures of eukaryotic cells infected with clb+ E. coli rescues the DNA damage phenotype12. It stands to reason that if double-strand break formation by colibactin-645 (2) were significant, DNA damage would still be observed in the presence of added ClbS.

Fourth, earlier publications described the characterization of the adenine adduct 4 in DNA that had been exposed to clb+ E. coli13,14 and in colonic epithelial cells of mice that had been colonized by the bacteria14. The structure 4 is thought to derive from nucleotide addition to 3 or clb products of greater complexity. NMR characterization of 4 established N3 as the site of adenine alkylation.14

Fifth, the structure 5 was recently advanced as that of colibactin7. To the best of this authors’ knowledge, this structure accounts for all of the data in the field. For example, 5 contains two DNA-reactive cyclopropane rings, which can logically give rise to the bacterial interstrand crosslink phenotype4. In addition, the biosynthesis of 5 requires every gene in the biosynthetic cluster, including clbQ (ref.7). Moreover, the diadenine adduct 6, expected based on the data outlined above, was detected in linearized plasmid DNA or genomic DNA derived from HeLa cells treated with clb+ E. coli or synthetic 5 (ref.7). This structure was supported by isotope labelling, tandem MS, and chemical synthesis7. A separate study supported the same proposal8.

The pursuit of a metabolite that directly induces DNA double-strand breaks may have been motivated by the disclosure that eukaryotic cells accumulate DNA double-strand breaks following exposure to colibactin-producing bacteria3. However, the interstrand crosslink phenotype subsequently reported4 and supported by the data outlined above is entirely consistent with this observation. Interstrand crosslinks are resolved by the Fanconi anaemia pathway during S phase15. Fanconi anaemia repair is initiated by stalling of two replication forks on either side of the interstrand crosslink. This is followed by displacement of the replisome assembly, fork reversal, and excision of the interstrand crosslink from one strand. This excision step creates a DNA double-strand break and activates the homologous recombination repair pathway. Homologous recombination repair factors, including phospho-SER139-H2AX, are recruited to the site of the Fanconi anaemia-induced double-strand break. Thus, because Fanconi anaemia is coupled to homologous recombination repair, the detection of phospho-SER139-H2AX is expected following initiation of Fanconi anaemia repair. Additionally, the generation of these interstrand crosslink-dependent double-strand breaks leads to DNA fragments with increased mobility in a neutral comet assay. Further supporting this, eukaryotic cells infected with clb+ E. coli lagged in S phase3 (the point in the cell cycle at which Fanconi anaemia repair is operative) and displayed co-localization of Fanconi anaemia protein D2 and phospho-SER139-H2AX (ref.4). Moreover, any interstrand crosslinks not repaired in S phase will be cleaved by nucleases, leading to double-strand break formation. Furthermore, N3 adenine adducts such as the one giving rise to 4 readily undergo depurination. Elimination of the 3′ phosphate, or hydrolysis by human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1, may also contribute to DNA cleavage.

Because natural colibactin has, to date, eluded isolation, researchers must build a model to describe its structure and mechanism of action. The scientific method dictates that this model is tested against all known observations in the literature. In aggregate, while Li et al.’s finding that colibactin-635 (2) directly induces double-strand breaks is interesting, the work fails to account for most of the key observations in this field. Thus, the conclusion that the DNA-damaging abilities of 1 or 2 are relevant to the cellular genotoxic effects of clb+ E. coli is not fully substantiated.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (R01CA215553) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-020-00551-8.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- 1.Arthur JC et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 338, 120–123 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Z-R et al. Macrocyclic colibactin induces DNA double-strand breaks via copper-mediated oxidative cleavage. Nat. Chem 11, 880–889 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nougayrède J-P et al. Escherichia coli induces DNA double-strand breaks in eukaryotic cells. Science 313, 848–851 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bossuet-Greif N et al. The colibactin genotoxin generates DNA interstrand crosslinks in infected cells. MBio 9, e02393–02317 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colis LC et al. The cytotoxicity of (–)-lomaiviticin A arises from induction of double-strand breaks in DNA. Nat. Chem 6, 504–510 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healy AR, Nikolayevskiy H, Patel JR, Crawford JM & Herzon SB A mechanistic model for colibactin-induced genotoxicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 15563–15570 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xue M et al. Structure elucidation of colibactin. Preprint at 10.1101/574053 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Jiang Y et al. The reactivity of an unusual amidase may explain colibactin’s DNA crosslinking activity. Preprint at 10.1101/567248 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Vizcaino MI & Crawford JM The colibactin warhead crosslinks DNA. Nat. Chem 7, 411–417 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bossuet-Greif N et al. Escherichia coli ClbS is a colibactin resistance protein. Mol. Microbiol 99, 897–908 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripathi P et al. ClbS is a cyclopropane hydrolase that confers colibactin resistance. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 17719–17722 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shine EE et al. Model colibactins exhibit human cell genotoxicity in the absence of host bacteria. ACS Chem. Biol 13, 3286–3293 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue M, Shine E, Wang W, Crawford JM & Herzon SB Characterization of natural colibactin–nucleobase adducts by tandem mass spectrometry and isotopic labeling. Support for DNA alkylation by cyclopropane ring opening. Biochemistry 57, 6391–6394 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson MR et al. The human gut bacterial genotoxin colibactin alkylates DNA. Science 363, eaar7785 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clauson C, Schärer OD & Niedernhofer L Advances in understanding the complex mechanisms of DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol 5, a012732 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]