Abstract

Limited information is available concerning the specificity of the forms and functions of aggressive behavior exhibited by boys with fragile X syndrome (FXS). To investigate these relationships, we conducted indirect functional assessments of aggressive behavior exhibited by 41 adolescent boys with FXS and 59 age and symptom-matched controls with intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) and compared the data between groups. Results showed that boys with FXS were more likely to exhibit specific forms of aggressive behavior (i.e., scratching others and biting others) compared to controls, but the sources of reinforcement identified for aggression were similar across groups. Boys with FXS who were prescribed psychotropic medications were more likely to be older and to exhibit more forms of aggression. The implications for the treatment of aggressive behavior during this critical developmental period in FXS are discussed.

Keywords: fragile X syndrome, aggression, indirect functional assessment, behavioral phenotypes

People with fragile X syndrome (FXS), the most common known inherited form of intellectual and developmental disability (IDD), are at increased risk for exhibiting problem behaviors such as aggression and destructive behaviors (Bailey et al., 2012; Moss et al., 2008). A recent systematic review of the literature indicated that between 13–61% of people with FXS display aggressive behavior, a significantly higher prevalence rate compared to those with idiopathic IDD (Hardiman & McGill, 2018). In addition to the high prevalence of aggression, particularly among boys with FXS, these behaviors cause significant distress to families and can have negative downstream health, psychiatric, educational, social, and financial consequences (Allen, 2000; Duncan et al., 1999; Hall et al., 2016; Jacobson, 1992). For example, Hall and colleagues (2016) reported that approximately one-third of boys with FXS aged 11 to 18 years engaged in aggression that resulted in minor injury to others, and just under one-fifth engaged in aggression that posed a significant threat to health or safety (Hall et al., 2016). Given the high prevalence and severe impact of aggression exhibited by males with FXS, this syndrome can be regarded as an important model for investigating the link between genes, environment and behavior.

FXS is caused by mutations to the FMR1 gene at location Xq27.3 on the long arm of the X chromosome (Verkerk et al., 1991) resulting in transcriptional silencing and consequent reduction or absence of Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP), the protein product of the gene (Devys et al., 1993). Individuals with the full mutation exhibit low levels of FMRP, which appears to cause or at least exacerbate the symptoms of FXS (Reiss et al., 1995; Tassone et al., 1999) including impairments in cognitive functioning, social-emotional processing and autistic-like behaviors (Hall et al., 2008; Newman et al., 2015; Reiss et al., 1995). There is also some evidence to suggest that specific downstream genetic factors may be associated with aggressive behavior in males with FXS (Hessl et al., 2008).

Forms of Aggressive Behavior

Data from prevalence studies have also suggested that people with FXS may exhibit specific forms of aggression behavior at higher rates than would be expected. In one such study, Hessl et al. (2008) used the Behavior Problems Inventory (BPI; Rojahn, Matson, Lott, Esbensen, & Smalls, 2001) to examine aggressive behavior in 38 males with FXS and found the most common forms of aggression were hitting others (49% of the sample) and kicking others (30% of the sample). Similarly, in a large sample of males and females with FXS, Wheeler and colleagues (2015) reported that the most common forms of aggressive behaviors were hitting, pushing or kicking others, occurring in 54% of male individuals aged 3 to 67 years.

Social-Environmental Factors

Although data concerning the prevalence, severity, and forms of aggressive behavior are important for describing the extent of the problem in FXS, fewer research studies have focused on examining the circumstances under which these behaviors might occur. Such information is critical for understanding the interactions between genes, environment, and behavior in this syndrome, as well as for designing interventions to treat aggressive behaviors in FXS (Hall, 2009). For example, studies have shown that aggression in people with IDD may be maintained by social-environmental factors in the form of the individual gaining access to attention/tangible items (i.e., social-positive reinforcement) and/or escaping from tasks or activities (i.e., social-negative reinforcement; Beavers et al., 2013; Hanley et al., 2003). It is also possible that in some cases, aggressive behaviors may be maintained by increased sensory stimulation (i.e., automatic-positive reinforcement) and/or removing painful stimulation (i.e., automatic-negative reinforcement; Iwata et al., 2013).

To investigate whether aggressive and destructive behaviors in FXS may be influenced by environmental factors, several small-scale studies have conducted experimental functional analyses of these behaviors in FXS (Hall et al., 2018; Kurtz et al., 2015; Langthorne & McGill, 2011; Machalicek et al., 2014). In an experimental functional analysis (FA), common antecedents and consequences for problem behavior are systematically manipulated under controlled conditions, thereby allowing the function(s) of the behaviors to be identified (Iwata et al., 1994). The outcome of these studies indicated that in the majority of cases, aggressive and destructive behaviors were maintained primarily by social-positive and/or social-negative reinforcement, with relatively few individuals displaying problem behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement (Kurtz et al., 2015). Some researchers have suggested that aggression in FXS may be reinforced by social-environmental factors at rates similar to those diagnosed with idiopathic IDD (Langthorne et al., 2011; Newcomb & Hagopian, 2018). However, to determine whether this may be the case, studies are needed to directly compare the outcomes of functional assessments between people with FXS and age and symptom-matched controls.

Although experimental FA is a reliable and valid approach to obtain information concerning behavior-environment relations, it also poses a number of limitations. First, experimental functional analyses require considerable resources and expertise to implement successfully (Carr, 1994). Second, given that experimental functional analyses are conducted in contrived settings, as opposed to naturalistic settings, the ecological validity of the data may be compromised (Carr, 1994). Furthermore, exposing the individual to antecedent and consequent events that directly evoke the problem behavior may pose significant risk to the individual concerned (Beavers et al., 2013). It may therefore be impractical to conduct functional analyses on a large sample of individuals, particularly those with rare genetic conditions who are spread out across the country. Indirect methods of assessment (e.g., questionnaires, interviews, and rating scales) may therefore be an alternative solution to obtain relevant information on a large sample of individuals with FXS, particularly those who display severe forms of problem behavior.

Studies employing indirect functional assessment methods can provide a rich source of information concerning environmental factors that might be associated with problem behavior, albeit with the potential for bias or recall errors from caregivers supplying this information (Dufrene et al., 2017; O’Neill, 1990). Furthermore, in some cases, results from indirect methods of assessment have been found to be concordant with direct methods of assessment (i.e., FA) (Hall, 2005; Hustyi et al., 2013). To date, however, few studies have conducted indirect functional assessments of problem behaviors in FXS. In one such study, Langthorne & McGill (2011) examined the sources of reinforcement for aggression exhibited by boys with FXS aged 5 to 21 years using the Questions About Behavioral Function (QABF) scale (Matson & Vollmer, 1995), a 25-item scale with 5 subscales: attention, escape, non-social, physical, and tangible. In that study, the primary sources of reinforcement identified were tangible (i.e., gaining access to preferred items) and escape (i.e., escaping from tasks/activities), whereas attention was rarely identified as a source of reinforcement for aggression. Given the low rate of attention-maintained aggressive behavior, these authors suggested that attention might function as an aversive stimulus for people with FXS or be a less effective type of reinforcement. This explanation is consistent with studies showing that social escape behaviors commonly occur during social interactions with others, particularly for males with FXS (Hall et al., 2005).

Association With Psychotropic Medications

Although decisions regarding the appropriate course of treatment for individuals who display aggression appear to vary widely, many people with FXS are prescribed psychotropic medications to manage these behaviors (Heyvaert et al., 2010). Data reported by FXS clinics nationally suggest that between 40–90% of people diagnosed with FXS are prescribed one or more psychotropic medications in their lifetime (Berry-Kravis & Potanos, 2004; Laxman et al., 2018). Despite the high rate of medication use in FXS, information concerning the association between psychotropic medications and the forms and functions of aggression is limited. A recent study conducted by Laxman et al. (2018) found that people with FXS who exhibited more severe problem behaviors were likely to continue taking psychotropic medications three years after they were prescribed the medication. However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined the extent to which the forms and potential sources of reinforcement identified for aggression in FXS may be associated with medication usage.

When examining research on people with IDD in general, research suggests that individuals who exhibit maladaptive behaviors are likely to be prescribed psychotropic medications (Bowring et al., 2017; Laxman et al., 2018). In one such study, findings suggested that people with IDD who exhibited physical aggression were more likely to be prescribed psychotropic medications compared to those who displayed other forms of maladaptive behaviors (Tsakanikos et al., 2006).

The current study aims to refine and extend previous research in several ways. First, we used a relatively new assessment tool, the Functional Analysis Screening Tool (Iwata et al., 2013), to identify the sources of reinforcement for aggressive behavior. Because this questionnaire includes items specifically designed to identify potential antecedents and consequences for problem behaviors, it is a relatively quick and affordable method to obtain preliminary information concerning the potential sources of reinforcement maintaining problem behaviors. Second, given the wide age range of participants included in previous studies, we restricted the age range of participants included in the present study to include adolescent males (ages 11 to 18 years) given that aggression can be particularly difficult for families to manage during this critical developmental period. Third, we included a control group of age-matched boys with IDD who exhibited similar levels of aggression in order to determine whether the forms and sources of reinforcement for aggression were specific to FXS. Finally, given that a significant proportion of individuals had been prescribed psychotropic medications as a treatment for aggressive behavior, we examined potential associations between psychotropic medication use and the forms and functions of aggression. We had the following research questions:

What are the primary forms and sources of reinforcement for aggression exhibited by adolescent boys with FXS?

To what extent are the forms and sources of reinforcement for aggressive behavior specific to FXS?

To what extent are the forms and sources of reinforcement for aggression in FXS associated with psychotropic medication use?

Methods

Participants

All participants had taken part in a previous study investigating the relative prevalence, frequency, and severity of problem behaviors exhibited by adolescent boys with FXS compared to boys with mixed-etiology IDD (Hall et al., 2016). In our previous study, participants were contacted via advertisements to parent support groups for people with FXS and IDD. Children in the IDD group were reported to have a diagnosis of IDD but not to have FXS. For the present study, caregivers in each group were re-contacted by email if they indicated that their child exhibited aggressive behavior on at least a weekly basis. The email contained a link to an online survey with the following message: “Thank you for participating in our study of problem behavior. You indicated that your child engages in aggression on at least a weekly basis. To better our understanding of the forms and context in which your child’s behavior occurs, please take this brief follow-up survey.” All respondents were primary caregivers. Completed responses were obtained on 41 boys with FXS and 59 boys with IDD aged 11 to 18 years. The mean age of boys with FXS was 13.7 years (SD = 2.3 years) and the mean age of the controls was 13.3 years (SD = 2.04 years), a non-significant difference between the groups (t(98) = 1.02, p = .31). Seven boys with FXS had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), three boys had a diagnosis of ADHD and one boy with FXS also had Klinefelter syndrome. In the control group, 17 boys had a diagnosis of ASD, five boys had a diagnosis of ADHD, one boy had Tourette syndrome, one boy had Prader-Willi syndrome, one boy had Dubowitz syndrome and one boy had cerebral palsy.

Measures

An online survey was used to collect data in two parts. In Part 1, demographic data were obtained on the child’s current age, diagnosis, frequency of aggressive behavior (hourly, daily, weekly, less than weekly), severity of aggressive behavior (not a problem, mild, moderate, severe) and any current treatments the child was receiving for aggressive behavior. Mild aggressive behavior was defined as “disruptive but little risk to property or health”, moderate aggressive behavior was defined as “property damage or minor injury occurred” and severe aggressive behavior was defined as “results in significant threat to health and safety”. Caregivers indicated the forms of problem behavior that their child displayed by selecting from a list of 11 forms of aggression. In Part 2, caregivers completed the Functional Analysis Screening Tool (FAST; Iwata et al. 2013), a 16-item informant-based questionnaire designed to identify potential sources of reinforcement for problem behaviors. The FAST contains four subscales (i.e., social attention/preferred items, social escape from tasks/activities, automatic sensory stimulation and automatic pain attenuation) with each subscale containing four items. Items in the social attention/preferred items subscale include an antecedent question related to attention (“Does the problem behavior occur when the person is not receiving attention or when caregivers are paying attention to someone else?)”, an antecedent question related to tangible items (“Does the problem behavior occur when the person’s requests for preferred items or activities are denied or when these are taken away?”), and a consequence question related to attention/tangibles (“When the problem behavior occurs, do caregivers usually try to calm the person down or involve the person in preferred activities?”). This subscale is designed to determine whether the behavior is maintained by social-positive reinforcement (S+). Items in the social escape from tasks/activities subscale include an antecedent question (“Does the problem behavior occur when the person is asked to perform a task or to participate in activities”?), and a consequence question (“If the problem behavior occurs while tasks are being presented, is the person usually given a “break” from tasks?”). This subscale is designed to determine whether the behavior is maintained by social-negative reinforcement (S−). Items in the automatic sensory stimulation subscale include an antecedent question (“Does the problem behavior occur even when no one is nearby or watching?”), and a consequence question (“Does the problem behavior appear to be a form of “self-stimulation”?). This subscale is designed to determine whether the behavior is maintained by automatic-positive reinforcement (A+). Finally, items in the automatic pain attenuation subscale include an antecedent question (“Is the problem behavior more likely to occur when the person is ill?”) and a consequence question (“If the person is experiencing physical problems and these are treated, does the problem behavior usually go away?”). This subscale is designed to determine whether the behavior is maintained by automatic-negative reinforcement (A−). Items are answered either “yes”, “no”, or “N/A” and scores for each subscale are determined by summing the number of items endorsed (total possible score for each subscale = 4). Mean item-by-item agreement of the FAST has been reported to be 71.5%, equivalent to other informant-based measures of behavioral function commonly employed by clinicians and researchers (Iwata et al., 2013). This research was independently reviewed and approved by the Internal Review Board at Stanford University and all caregivers consented to take part in the study.

Data Analysis

All survey data were checked for completeness and downloaded from the survey into SPSS Version 20 (IBM Corp). We first examined whether the groups were similar in terms of the frequency and severity of aggressive behavior using chi-square tests. We then computed the frequencies of the forms of aggression reported and compared the prevalence between groups by conducting odds ratio (OR) analyses with a 99% confidence interval. Data from the FAST were analyzed in two ways. First, we examined the data on an item-by-item basis to identify any specific antecedents and consequences associated with aggression in each group. We then examined the data on a categorical basis by determining whether or not a source of reinforcement (i.e., social attention/tangible items, social escape from tasks/activities, automatic sensory stimulation and/or automatic pain attenuation) had been identified. As recommended by the authors of the FAST (Iwata et al., 2013), the subscale(s) with the highest score was identified as a source of reinforcement for aggression, with the caveat that at least three items had to have been endorsed for any subscale. If two or more subscales met these criteria, more than one source of reinforcement was identified (see Iwata et al., 2013). If none of the subscales met these criteria, the outcome was determined to be inconclusive. Finally, we examined the extent to which medication use was associated with the number of forms and number sources of reinforcement identified in each group. We used Mann-Whitney U tests to examine differences between those who were taking medications and those who were not taking medications. To avoid potential Type I errors, we set the alpha level at 0.01.

Results

Table 1 shows the frequency and severity of aggressive behavior reported for each group. Chi-square analyses indicated that there were no differences between the groups in terms of the frequency and severity of aggressive behavior reported. Approximately one half of participants in each group exhibited aggression on at least a daily basis and just under one quarter of caregivers in each group reported that their child exhibited aggression that resulted in a significant threat to health and safety.

Table 1.

Frequency and Severity of Aggression Reported for Each Group

| FXS (N = 41) | Controls (N = 59) | X2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of aggression | ||||

| Hourly | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1.44 | ns |

| Daily | 18 (43.9%) | 30 (50.8%) | ||

| Weekly | 12 (29.3%) | 19 (32.2%) | ||

| Less than weekly | 10 (24.4%) | 9 (15.3%) | ||

| Severity of aggression | ||||

| Severe | 10 (24.4%) | 14 (23.7%) | 3.57 | ns |

| Moderate | 17 (41.5%) | 34 (57.6%) | ||

| Mild | 14 (34.1%) | 11 (18.6%) |

Note. Severe: results in significant threat to health and safety; Moderate: property damage or minor injury occurred, Mild: disruptive but little risk to property or health. ns = not significant; FXS = Fragile X Syndrome.

Forms of Aggression

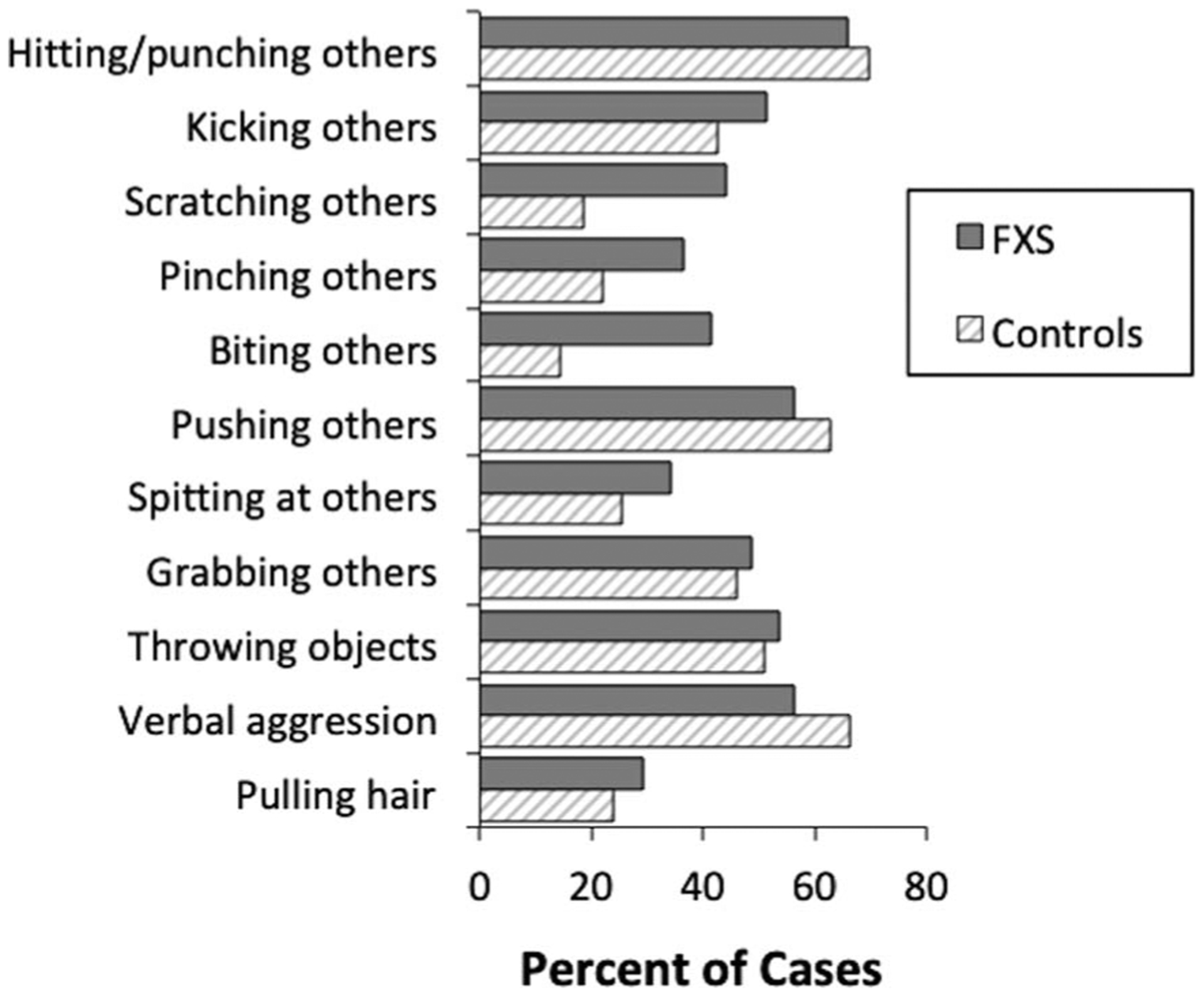

Figure 1 shows the percentage of participants reported to exhibit each form of aggression in each group.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of forms of aggression reported in each group. FXS=Fragile X Syndrome.

For boys with FXS, the most prevalent forms of aggression reported were hitting/punching others (65.9% of cases), verbal aggression (56.1% of cases), and pushing others (56.1% of cases). The most prevalent forms of aggression reported for controls were similarly hitting/punching others (69.5% of cases), verbal aggression (66.1% of cases), and pushing others (62.7% of cases). Statistical analyses conducted between groups indicated that boys with FXS were significantly more likely to engaging in scratching others (OR = 3.42, CI99% = 1.05, 11.14), and biting others (OR = 3.94, CI99% = 1.14, 13.59) compared to controls. The mean number of forms of aggression endorsed was 5.4 (SD = 2.9) for boys with FXS and 4.8 (SD = 2.4) for controls, a non-significant difference between the groups.

Item-by-Item Analysis

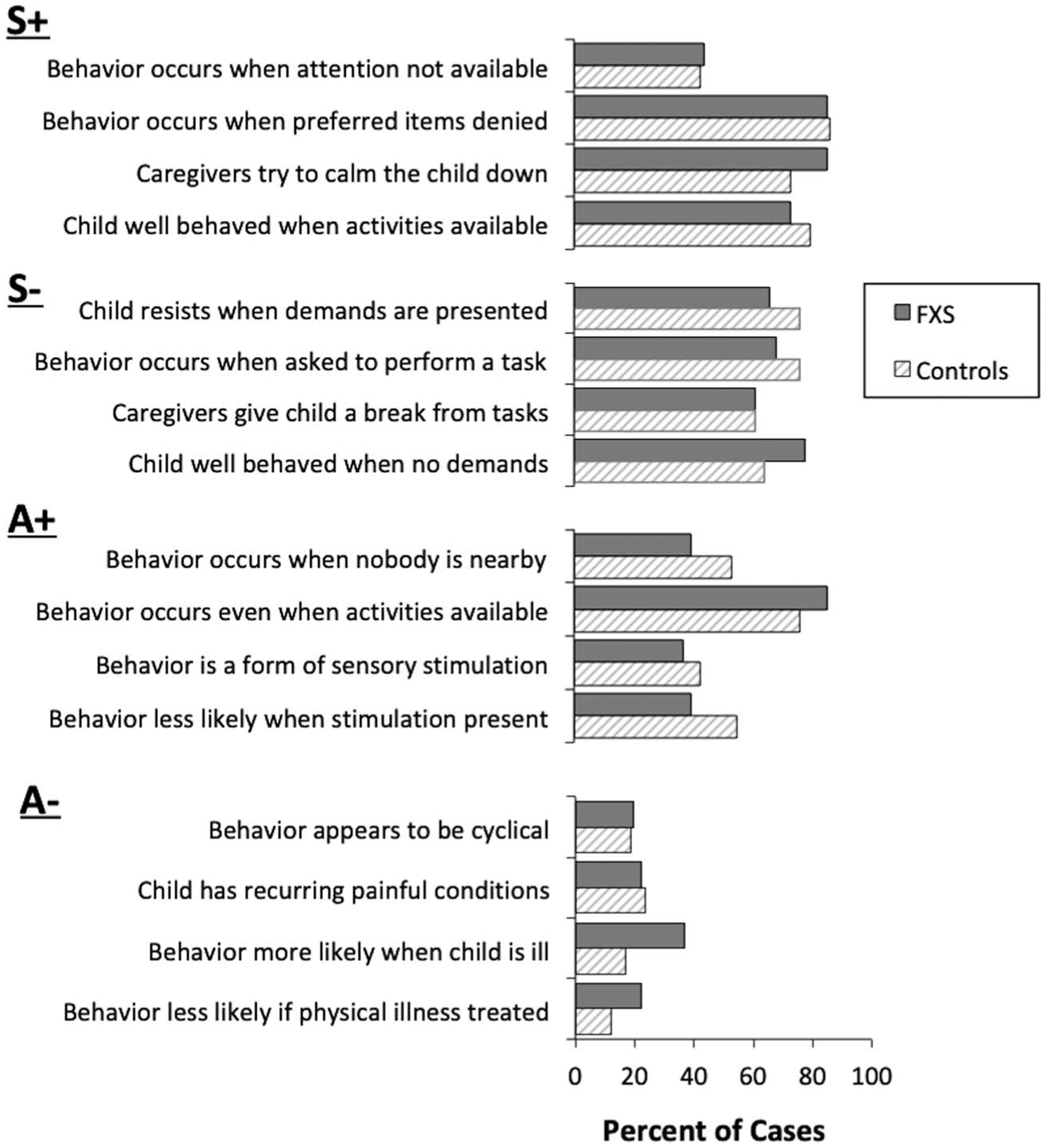

Figure 2 shows the results of the item-by-item analyses conducted on the FAST for each group. In this display, the prevalence of each item endorsed on the FAST is shown by subscale for each group.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of items endorsed for aggression on the FAST in each group. S+ = social-positive reinforcement; S− = social-negative reinforcement; A+ = automatic-positive reinforcement; A− = automatic-negative reinforcement; FXS = Fragile X Syndrome.

The data show that for both groups, the most prevalent items endorsed on the FAST were typically related to social-positive reinforcement (S+) and/or social-negative reinforcement (S−). For example, 85.4% of boys with FXS and 86.4% of controls were reported to display aggression when requests for preferred items or activities were denied or taken away (the antecedent related to tangible reinforcement) and 85.4% of boys with FXS and 72.9% of controls were reported to be usually calmed down or involved in preferred activities when aggression occurred (the consequence related to attention/tangible reinforcement). Caregivers reported that for 73.2% of boys with FXS and 79.7% of controls, the child was well behaved when he received lots of attention or when preferred items were freely available. Less than half of caregivers in each group (i.e., 43.9% and 42.4% respectively) reported that their child’s aggression occurred when they were not paying attention to their child or when caregivers are paying attention to someone else (the antecedent related to attention).

In terms of items related to social-negative reinforcement, 68.3% of boys with FXS and 76.3% of controls were reported to display aggression when asked to perform a task or to participate in activities and 61.0% of boys with FXS and 61.0% of controls were reported to usually give their child a break from tasks when aggression occurred. Caregivers reported that for 78.0% of boys with FXS and 64.4% of controls, their child was usually well behaved when he was not required to do anything.

There was less evidence to suggest that aggression may be maintained by automatic-positive reinforcement (A+) or automatic-negative reinforcement in either group. For example, caregivers reported that aggression appeared to be a form of self-stimulation for only 29.3% of boys with FXS and 33.9% of controls. Caregivers also reported that problem behavior was more likely to occur when their child was ill for 36.6% of boys with FXS and 16.9% of controls. Odds ratio analyses indicated that there were no statistical differences between the groups on any of the items.

Sources of Reinforcement

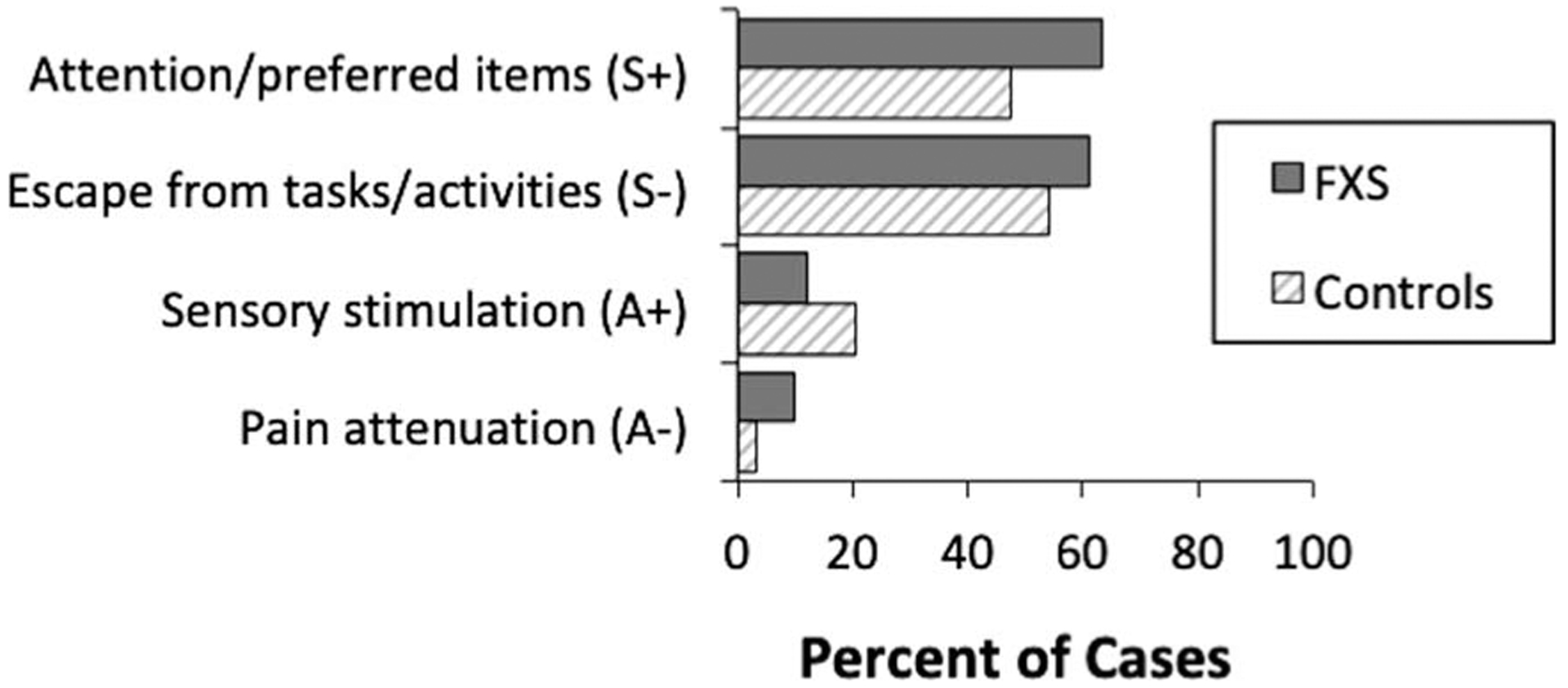

Figure 3 shows the prevalence of the sources of reinforcement identified for aggression on the FAST in each group.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of sources of reinforcement identified for aggression on the FAST in each group. S+ = social-positive reinforcement; S− = social-negative reinforcement; A+ = automatic-positive reinforcement; A− = automatic-negative reinforcement; FXS = Fragile X Syndrome.

For boys with FXS, the most prevalent sources of reinforcement identified for aggression were social attention/preferred items (63.4% of cases), followed by social escape from tasks/activities (61.0% of cases). For controls, the most prevalent sources of reinforcement identified were social escape from tasks/activities (54.2% of cases), followed by social attention/preferred items (47.5% of cases). Relatively few individuals in each group displayed aggression that was potentially maintained by sensory stimulation and/or pain attenuation. Odds ratio analyses indicated that there were no differences in terms of the sources of reinforcement identified between the groups.

Number of Sources of Reinforcement

For boys with FXS, a single source of reinforcement was identified for 39% of participants, whereas multiple sources of reinforcement were identified for 48.8% of participants. For controls, a single source of reinforcement was identified for 52.5% of participants, whereas multiple sources of reinforcement were identified for 35.6% of participants. There was no difference between the groups in terms of the number of sources of reinforcement identified.

Association With Psychotropic Medication Use in FXS

Caregivers reported that psychotropic medications had been prescribed as the primary treatment for aggression for 20 (48.8%) boys with FXS and 19 (32.2%) controls, a non-significant difference between the groups. Commonly reported psychotropic medications included antipsychotics, sedatives/anxiolytics, antidepressants, stimulants, medical cannabis, as well as several medications previously evaluated in clinical trials for FXS (e.g., STX209, minocycline, metformin, and arbaclofen). Approximately one third of caregivers reported that their child was taking two or more medications. Within-group analyses indicated that boys with FXS who were taking medications were significantly more likely to engage in kicking others (OR = 7.5, CI99% = 1.21, 46.35), and pulling others’ hair (OR = 9.5, CI99% = 1.02, 88.76). For controls, there were no associations between medication status and the forms of aggression reported.

Table 2 shows a breakdown of medication status by age, number of forms of problem behavior and number of sources of reinforcement identified for each group.

Table 2.

Mean Number of Forms and Sources of Reinforcement Identified for Aggression in Each Group Stratified by Medications Use

| Psychotropic Medications | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Mann-Whitney U | P | |

| FXS, N | 20 | 21 | ||

| Age (years) | 15.0 (2.3) | 12.6 (1.5) | 85.0 | .001 |

| Number of forms | 7.0 (2.9) | 4.0 (2.2) | 91.5 | .002 |

| Number of sources of reinforcement | 1.8 (.83) | 1.7 (.97) | 193.5 | ns |

| Controls, N | 19 | 40 | ||

| Age (years) | 13.1 (2.4) | 13.4 (1.9) | 339.5 | ns |

| Number of forms | 5.4 (2.2) | 4.5 (2.4) | 284.0 | ns |

| Number of sources of reinforcement | 1.9 (.81) | 1.5 (.81) | 273.0 | ns |

Note. Psychotropic medications included antipsychotics, sedatives/anxiolytics, antidepressants and/or stimulants. ns = not significant; FXS = Fragile X Syndrome.

These data show that boys with FXS who were taking medications for aggression were significantly older (M = 15.0, SD = 2.3 years) compared to boys who were not taking medications (M = 12.6, SD = 1.5 years) (U = 85, p = .001). Boys with FXS who were taking medications also exhibited a significantly greater number of forms of aggression (M = 7.0, SD = 2.9) compared to boys who were not taking medications (M = 4.0, SD = 2.3) (U = 91.5, p =.002). These associations were not found in controls.

Discussion

Increasing evidence suggests that social-environmental variables play an important role in the development and maintenance of problem behaviors exhibited by people with FXS. The primary aim of the present study was to generate hypotheses concerning the environmental determinants of aggression displayed by adolescent boys with FXS and to examine the specificity of the forms and functions of aggression in FXS. To accomplish this goal, we collected data on a relatively large sample of boys with FXS aged 11 to 18 years who exhibited aggression on at least a weekly basis and compared the outcomes of indirect functional assessments conducted on people with IDD who exhibited aggressive behaviors at similar levels.

We found that the primary sources of reinforcement identified for aggression in both groups were to gain access to attention/preferred items and escape from tasks/activities. These data support previous findings from smaller-scale experimental functional analyses of problem behaviors in FXS indicating that aggression and destructive behaviors in FXS may be maintained primarily by social-environmental factors (Hall et al., 2018). An item-by-item analysis of the data also indicated that the most common items endorsed by caregivers of both groups were associated with social reinforcement. Interestingly, less than half of boys in each group were reported to exhibit aggression when the caregiver was not paying attention to the child (the antecedent item on the FAST that was specific to attention) suggesting that attention may not function as reinforcement for aggression.

In the current study, we were able to identify a potential source of reinforcement for problem behavior on the FAST in approximately 90% of cases whereas in the study conducted by Langthorne & McGill (2011) using the QABF, a potential source of reinforcement was identified in only two-thirds of cases. This may have been due to the relatively conservative scoring algorithm employed for the QABF in the study by Langthorne & McGill (2011). In the present study, the subscale(s) with the highest score on the FAST were identified as a source of reinforcement, as recommended by the authors of the FAST (Iwata et al., 2013). We included an exception whereby a subscale with only two items endorsed would not be considered as a source of reinforcement even if it had received the highest score. This was done to limit the number of potential false-positive outcomes. Future studies will be needed to determine whether the scoring algorithm employed for the FAST will need to be further refined.

Just under half of boys with FXS and just under one third of controls were taking psychotropic medications for aggression. Of particular interest was the finding that children with FXS who were prescribed medications for aggression were more likely to exhibit specific forms of aggression (e.g., pulling hair, kicking others), as well as a greater number of forms of aggressive behavior compared to those who were not taking medications. This association was not found in controls. It is possible that multiple forms of aggression, particularly severely disruptive forms, were more likely to be addressed by physicians and caregivers. Unfortunately, we did not collect information about the length of time that the participants had been receiving medication for aggression or the perceived efficacy of the medication at reducing the aggression. It is possible that some people with FXS had been prescribed the medications only recently and that the medications had not yet shown an effect or that the medications were not effective at reducing aggressive behaviors. Alternatively, it is possible that the aggressive behaviors had previously been more frequent and that the medications had reduced the behaviors to a lower level. Longitudinal studies would be needed to examine the role of these potential factors.

Taken together, these data extend previous findings in the literature in several ways. First, our findings indicate that some aggressive behaviors such as scratching and biting others are more likely to occur in FXS, suggesting that there may be an underlying genetic component to these specific forms of behavior in FXS or that they are more likely to be reinforced in FXS. Additionally, we found that in the majority of cases, more than one source of reinforcement was identified. This finding supports previous reports that problem behavior in people with FXS may be reinforced by multiple sources of social reinforcement (e.g., access to tangibles, demand escape) (Hardiman & McGill, 2017). The fact that similar outcomes were obtained across groups indicates that the sources of reinforcement identified for aggression in FXS may not be syndrome-specific. Thus, function-based behavioral treatments such as Functional Communication Training that have been effectively used to treat behavioral symptoms of other disorders such as ASD may also be appropriate for use in FXS (Monlux et al., 2019). Lastly, research has found that identifying the function(s) of aberrant behavior prior to implementing interventions can increase the likelihood that treatments will be successful (Newcomb & Hagopian, 2018). This is because the treatment can be matched to the function of the behavior, increasing the likelihood that the treatment or behavioral intervention will be successful. Our findings build upon this body of work, and suggest a need for continued exploration about how form and function relates to treatment outcomes.

To our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to utilize the FAST to examine the forms and sources of reinforcement for aggression in FXS. Indirect assessment methods have increased in popularity given their accessibility, affordability, and ease of use (Alter et al., 2008). While an experimental functional analysis provides a more rigorous, reliable and valid methodology for determining the function of a particular behavior, it is costly, time intensive, and may put the examiner and individual being assessed at risk of injury. Furthermore, examiners conducting FAs require specific and time intensive training (Beavers et al., 2013; Carr, 1994). For these reasons, in conjunction with the increased availability of indirect assessment tools, professionals in the field have increasingly employed indirect methods as an alternative (Dufrene et al., 2017). However, little research to date has examined whether indirect functional assessments can provide useful information to generate hypotheses about the functions of aggressive behavior.

There are several strengths of this study. First, the data were obtained from a community sample as opposed to a single clinic, therefore the findings may be more representative of the broader FXS male population than other studies. Second, we listed a wide range of forms of aggression on the survey to ensure that we sampled as many forms of aggression as possible. This provided us with greater detail that often is overlooked in studies examining aggression. Finally, we asked caregivers to list any current treatments their child may be receiving for aggression, rather than treatments that may have been prescribed for other behaviors or co-morbid conditions.

Several potential limitations of this study include the reliance upon parental report as opposed to observational or experimental methods. Data were collected using an online survey tool as opposed to being obtained via an in-person interview or postal survey, limiting the opportunity for follow-up questions or clarification about the behavior characteristics, diagnosis, etc. Although parent report is employed in the majority of studies examining psychotropic medication use in people with developmental disabilities (Coury et al., 2012; Mire et al., 2013), it would be important to check the reliability of these reports. Additionally, because the study design is cross-sectional, inferences cannot be drawn about directionality of these effects. Lastly, because we relied on parent report, cognitive level and comorbid autism status scores were not obtained for either the FXS or IDD group. This limits our ability to be certain that the groups were well matched.

Future research should continue to examine the relationship between age, severity, form, and function of aggressive behavior and treatment in efforts to explore these effects in greater detail. Furthermore, future studies should seek to combine the use of parent report with more rigorous behavioral outcome data (e.g. FA data) to better understand the relationship between problem behaviors and psychotropic medication use in FXS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the families for participating in the study and Rebecca Barnett for her assistance with the survey.

References

- Allen D (2000). Recent research on physical aggression in persons with intellectual disability: An overview. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 25(1), 41–57. 10.1080/132697800112776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alter PJ, Conroy MA, Mancil GR, & Haydon T (2008). A comparison of functional behavior assessment methodologies with young children: Descriptive methods and functional analysis. Journal of Behavioral Education, 17(2), 200–219. 10.1007/s10864-008-9064-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Raspa M, Bishop E, Mitra D, Martin S, Wheeler A, & Sacco P (2012). Health and economic consequences of Fragile X syndrome for caregivers. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 33(9), 705–712. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318272dcbc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beavers GA, Iwata BA, & Lerman DC (2013). Thirty years of research on the functional analysis of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(1), 1–21. 10.1002/jaba.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry-Kravis E, & Potanos K (2004). Psycho-pharmacology in fragile X syndrome: Present and future. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 10(1), 42–48. 10.1002/mrdd.20007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowring DL, Totsika V, Hastings RP, Toogood S, & McMahon M (2017). Prevalence of psychotropic medication use and association with challenging behaviour in adults with an intellectual disability. A total population study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 61(6), 604–617. 10.1111/jir.12359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr EG (1994). Emerging themes in the functional analysis of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(2), 393–399. 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coury DL, Anagnostou E, Manning-Courtney P, Reynolds A, Cole L, McCoy R, Whitaker A, & Perrin JM (2012). Use of psychotropic medication in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 130(Supplement 2). 10.1542/peds.2012-0900D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devys D, Lutz Y, Rouyer N, Bellocq J, & Mandel J (1993). The FMR–1 protein is cytoplasmic, most abundant in neurons and appears normal in carriers of a fragile X premutation. Nature Genetics, 4(4), 335–340. 10.1038/ng0893-335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufrene BA, Kazmerski JS, & Labrot Z (2017). The current status of indirect functional assessment instruments. Psychology in the Schools, 54(4), 331–350. 10.1002/pits.22006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan D, Matson JL, Bamburg JW, Cherry KE, & Buckley T (1999). The relationship of self-injurious behavior and aggression to social skills in persons with severe and profound learning disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 20(6), 441–448. 10.1016/S0891-4222(99)00024-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SS (2005). Comparing descriptive, experimental and informant-based assessments of problem behaviors. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 26(6), 514–526. 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SS (2009). Treatments for Fragile X syndrome: A closer look at the data. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 15(4), 353–360. 10.1002/ddrr.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SS, Barnett RP, & Hustyi KM (2016). Problem behavior in adolescent boys with fragile X syndrome: Relative prevalence, frequency and severity. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 60(12), 1189–1199. 10.1111/jir.12341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SS, Hustyi KM, & Barnett RP (2018). Examining the influence of social-environmental variables on self-injurious behaviour in adolescent boys with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62(12), 1072–1085. 10.1111/jir.12489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SS, Lightbody AA, & Reiss AL (2008). Compulsive, self-injurious, and autistic behavior in children and adolescents with fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 113(1), 44–53. 10.1352/0895-8017(2008)113[44:CSAABI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Iwata BA, & McCord BE (2003). Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(2), 147–185. 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardiman RL, & McGill P (2017). The topographies and operant functions of challenging behaviours in fragile X syndrome: A systematic review and analysis of existing data. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 42(2), 190–203. 10.3109/13668250.2016.1225952 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardiman RL, & McGill P (2018). How common are challenging behaviours amongst individuals with fragile X syndrome? A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 76, 99–109. 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessl D, Tassone F, Cordeiro L, Koldewyn K, McCormick C, Green C, Wegelin J, Yuhas J, Hagerman RJ (2008). Brief report: Aggression and stereotypic behavior in males with fragile X syndrome-moderating secondary genes in a “single gene” disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(1), 184–9. 10.1007/s10803-007-0365-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyvaert M, Maes B, & Onghena P (2010). A meta-analysis of intervention effects on challenging behaviour among persons with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(7), 634–649. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01291.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustyi KM, Hammond JL, Rezvani AB, & Hall SS (2013). An analysis of the topography, severity, potential sources of reinforcement, and treatments utilized for skin picking in Prader-Willi syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(9), 2890–2899. 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2011). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata BA, Deleon IG, & Roscoe EM (2013). Reliability and validity of the Functional Analysis Screening Tool. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(1), 271–284. 10.1002/jaba.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata BA, Dorsey MF, Slifer KJ, Bauman KE, & Richman GS (1994). Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(2), 197–209. 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JW (1992). Who is treated using restrictive behavioral procedures? Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 4(2), 99–113. 10.1007/BF01046393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz PF, Chin MD, Robinson AN, O’Connor JT, & Hagopian LP (2015). Functional analysis and treatment of problem behavior exhibited by children with fragile X syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabili ties, 43–44, 150–166. 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langthorne P, & McGill P (2011). An indirect examination of the function of problem behavior associated with fragile X syndrome and Smith-Magenis syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(2), 201–209. 10.1007/s10803-011-1229-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langthorne P, McGill P, Oreilly MF, Lang R, Machalicek W, Chan JM, & Rispoli M (2011). Examining the function of problem behavior in fragile X syndrome: Preliminary experimental analysis. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 116(1), 65–80. 10.1352/1944-7558-116.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxman DJ, Greenberg JS, Dawalt LS, Hong J, Aman MG, & Mailick M (2018). Medication use by adolescents and adults with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62(2), 94–105. 10.1111/jir.12433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machalicek W, McDuffie A, Oakes A, Ma M, Thurman AJ, Rispoli MJ, & Abbeduto L (2014). Examining the operant function of challenging behavior in young males with fragile X syndrome: A summary of 12 cases. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(7), 1694–1704. 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, & Vollmer TR (1995). User’s guide: Questions about behavioral function (QABF). Scientific Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mire SS, Nowell KP, Kubiszyn T, & Goin-Kochel RP (2013). Psychotropic medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders within the Simons Simplex Collection: Are core features of autism spectrum disorder related? Autism, 18(8), 933–942. 10.1177/1362361313498518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monlux KD, Pollard JS, Bujanda Rodriguez AY, & Hall SS (2019). Telehealth delivery of function-based behavioral treatment for problem behaviors exhibited by boys with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(6), 2461–2475. 10.1007/s10803-019-03963-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss J, Oliver C, Arron K, Burbidge C, & Berg K (2008). The prevalence and phenomenology of repetitive behavior in genetic syndromes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(4), 572–588. 10.1007/s10803-008-0655-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ET, & Hagopian LP (2018). Treatment of severe problem behaviour in children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disabilities. International Review of Psychiatry, 30(1), 96–109. 10.1080/09540261.2018.1435513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman I, Leader G, Chen JL, & Mannion A (2015). An analysis of challenging behavior, comorbid psychopathology, and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Fragile X Syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 7–17. 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill RE (1990). Functional analysis of problem behavior: A practical assessment guide. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss AL, Freund LS, Baumgardner TL, Abrams MT, & Denckla MB (1995). Contribution of the FMR1 gene mutation to human intellectual dysfunction. Nature Genetics, 11(3), 331–334. 10.1038/ng1195-331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojahn J, Matson JL, Lott D, Esbensen AJ, & Smalls Y (2001). The Behavior Problems Inventory: An instrument for the assessment of self-injury, stereotyped behavior, and aggression/destruction in individuals with developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(6), 577–588. 10.1023/A:1013299028321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Iklé DN, Dyer PN, Lampe M, Willemsen R, Oostra B, & Taylor AK (1999). FMRP expression as a potential prognostic indicator in fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 84(3), 250–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakanikos E, Costello H, Holt G, Sturmey P, & Bouras N (2006). Behaviour management problems as predictors of psychotropic medication and use of psychiatric services in adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(6), 1080–1085. 10.1007/s10803-006-0248-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk AJMH, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Fu Y-H, Kuhl DPA, Pizzuti A, Reiner O, Richards S, Victoria MF, Zhang F, Eussen BE, van Ommen G-JB, Blonden LAJ, Riggins GJ, Chastain JL, Kunst KB, Galijaard H, Caskey CT, Nelson DA, … Warren ST (1991). Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell, 65(5), 905–914. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90397-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AC, Raspa M, Bishop E, & Bailey DB (2015). Aggression in fragile X syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 60(2), 113–125. 10.1111/jir.12238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]