Abstract

Diarrhoea is the passage of three or more loose or liquid stools per day or more frequent passage than is normal for an individual. Diarrhoea alters the microbiome, thus the immune system, and is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in young children. This study evaluated the association between the risk factors and diarrhoea prevalence among children under five years in Lagos and Ogun States, located in Southwest Nigeria. Participants included 280 women aged 15–49 years and children aged 0–59 months. The study used quantitative data, which were assessed by a structured questionnaire. Data obtained were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Software Version 25.0 and Microsoft Excel 2013. The relationships and/or association between variables were evaluated using Pearson's Chi Square and logistic regression tests. One hundred and eighteen (42%) of the children were male, and 162 (58%) were female. The majority of the children belonged to the age group 0–11 months (166). Age (p=0.113) and gender (p=0.366) showed no significant association with diarrhoea among the children. The majority of the mothers belonged to the age group 30–34. Multivariate analysis showed that the mother's level of education (95% CI for OR = 11.45; P=0.0001) and family income (95% CI for OR = 7.61, P=0.0001) were the most significant risk factors for diarrhoea among children. Mother's educational status, mother's employment, and family income were the factors significantly associated with diarrhoea in Southwest Nigeria. The study recommends that female education should be encouraged by the right government policy to enhance the achievement of the sustainable development goal three (SDG 3) for the possible reduction of neonates and infants' deaths in Nigeria.

1. Introduction

World Health Organisation defines diarrhoea as “the passage of three or more loose or liquid stools per day or more frequent passage than is normal for the individual” [1, 2]. Diarrhoeal disease is the second leading cause of death in children under five years old and is responsible for killing around 525 000 children every year [2]. Childhood diarrhoea affecting children five years old and below accounts for approximately 63% of diarrhoea burden [3, 4] and is the second significant cause of infant mortality in developing nations [2, 5–7], where poor sanitation and insufficient potable water are lacking [8, 9]. In Southwest Nigeria, diarrhoea is one of the three most prevalent water-related diseases, the others being typhoid fever and cholera [10, 11]. In Southwest Nigeria, most of the studies on childhood diarrhoea have focused on the molecular epidemiology of diarrhoeagenic agents [12–15]. Several other studies have reported the antimicrobial activities of indigenous medicinal plants on diarrhoea-causing agents [16–18]. However, there are insufficient reports on the associated risk factors of childhood diarrhoea in Southwest Nigeria [19, 20]. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the risk factors associated with diarrhoea prevalence among children under age 5 in Lagos and Ogun States, Nigeria.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

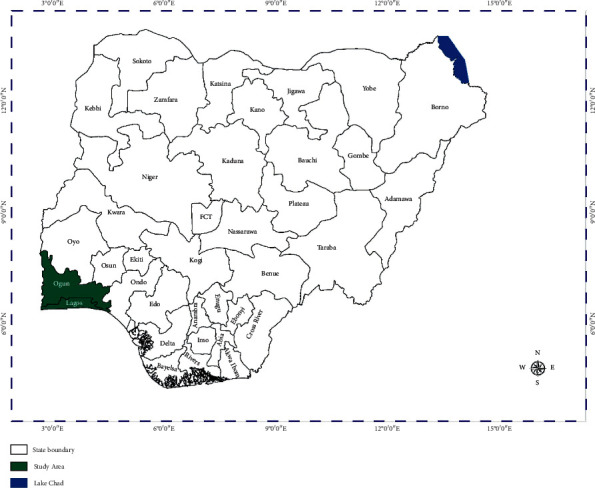

The study was carried out in Lagos state (6o52ʹ44ʺ N, 3.37ʹ92ʺ E) and Ogun state (6° 90ʹ 75ʺ N 3° 58ʹ 13ʺ E), located in Southwest Nigeria (Figure 1). In Southwest Nigeria, three tiers of health care services are practiced, which are the tertiary, secondary, and primary healthcare systems [21]. These hospitals provide subsidised health care services to the masses. Massey Street Children Hospital is a children's referral hospital owned by the Lagos State government [22]. Orile-Agege General Hospital has an excellent hospital-based record of paediatric cases and immunisation services. State Hospital Ota is proxy to the study centre. Federal Medical Centre Abeokuta is a federal government-owned hospital with high patronage and also serves as a referral hospital in Ogun state [23, 24].

Figure 1.

Map of Nigeria showing the study area.

The study was a cross-sectional case-control investigation involving four local government areas (LGAs) in Lagos and Ogun state, which were Lagos Island and Agege LGAs from Lagos state, Ado/Odo Ota, and Abeokuta South LGAs from Ogun state (Figure 1), respectively. Participants included a total of 280 children comprising 143 children with acute diarrhoea (cases) and 137 children who were not suffering from diarrhoea (controls) over 12 months. The diarrhoeic children were those that have been diagnosed by the medical personnel at the hospital for this study, and the control groups were children within the same age bracket that were not having diarrhoea and were attending the same healthcare facilities.

3. Eligibility Criteria for the Study Participants

3.1. Criteria for Nondiarrhoeic Group (Control)

3.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

Under five children

No acute diarrhoea

Not on any antimicrobial treatment

Informed written consent from the parents/guardians of children and assent from the subjects

3.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

Children whose parents did not consent

3.2. Criteria for Diarrhoeic Group (cases)

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Under five children

Acute diarrhoea (≥3 watery or loose stools with or without blood or mucus less than 14 days)

Informed written consent from the parents/guardians of children and assent from the subjects

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Children whose parents did not consent

3.3. Ethical Consideration

Participation was strictly voluntary. Parents/Caregivers received a thorough explanation of the aim, and objectives of the study were explained to the parents or caregivers. Each parent decided whether or not to participate or provide information about their children or wards. Participants were also enlightened about their freedom to withdraw in the course of the study without any consequences.

The ethical approval for this study was obtained from Covenant University Health Research Ethics Committee (CUHREC), Covenant University, Ota, Ogun State (CHREC/002/2018), Federal Medical Centre Research Ethics Committee (FMCREC), Idi-Aba, Abeokuta Ogun State (FMCA/243/HREC/03/2018/06), and Lagos State Health Service Commission (LSHSC/2222/VOL.1VB/232).

3.4. Questionnaire Survey

The authors developed a semistructured questionnaire. Mothers/caregivers responded through the assistance of hired research assistants. Communication was in English Language and local dialects where the respondents could not communicate effectively in the English Language. The questionnaires provided demographic, medical, nutritional, and environmental information about the children. Other information included the level of education and socioeconomic status of the mothers/caregivers.

3.5. Data Analysis

For quality control purposes, each completed questionnaire was proofed to avoid errors. The questionnaire data obtained were deposited in the SPSS Version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) program and Microsoft Excel 2013 for statistical analysis. Pearson's Chi square and t-test were used to determine the statistical significance in the relationships and or association between the dependent and independent variables. Comparisons were made between data derived from diarrhoeic and control subjects.

Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the association of each predictor variable with the outcome variable. Measures of the relationship were expressed as crude odds ratios (CORs) for disease with 95% confidence intervals for variables.

Multivariable analysis was performed using all the significant variables obtained from the bivariate analysis. This provided the Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) at 95% confidence interval.

4. Results

Risk factors of diarrhoeal disease among children under five years of age in the study area.

The risk factors of the occurrence of diarrhoea among children below the age of five were categorised into three, namely: age and gender of the child, demographic and socioeconomic status of the mother, and medical history and environment of the child (Tables 1–6 ).

Table 1.

Association between child's age group, gender, and diarrhoea.

| Characteristics | Diarrhoea status | COR (95% CI) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | ||||||

| Number (n) | Percentage (%) | Number (n) | Percentage (%) | ||||

| Age group (Months) | 0–11 | 64 | 44.76 | 102 | 74.45 | 0.359(0.101–1.274) | 0.113 |

| 12–23 | 51 | 35.66 | 20 | 14.60 | 1.457(0.384–5.525) | 0.580 | |

| 24–35 | 12 | 8.39 | 6 | 4.38 | 1.143(0.237–5.501) | 0.868 | |

| 36–47 | 9 | 6.29 | 5 | 3.65 | 1.029(0.199–5.326) | 0.973 | |

| 48–59 | 7 | 4.90 | 4 | 2.92 | 1.00 | ||

| Gender | Male | 64 | 44.76 | 54 | 39.42 | 1.245(0.774–2.003) | 0.366 |

| Female | 79 | 55.24 | 83 | 60.58 | 1.00 | ||

P < 0.05 is significant; COR: crude odds ratios; CI: confidence interval.

Table 2.

Association between demographic and socioeconomic variables of mothers/caregivers and diarrhoea.

| Characteristics | Diarrhoea status | COR (95% CI) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Cases | ||||||

| Number (n) | Percentage (%) | Number (n) | Percentage (%) | ||||

| Mother's age (years) | <30 | 47 | 34.30 | 45 | 31.70 | 0.888 (0.539–1.464) | 0.642 |

| >30 | 90 | 65.70 | 97 | 68.30 | |||

| Religion | Christianity | 116 | 85.29 | 74 | 51.75 | 0.185 (0.104–0.329) | <0.0001 |

| Islam | 20 | 14.71 | 69 | 48.25 | 1.00 | ||

| Educational status | Below tertiary | 27 | 20.00 | 106 | 74.13 | 11.459 (6.521–20.139) | <0.0001 |

| Tertiary | 108 | 80.00 | 37 | 25.87 | 1.00 | ||

| Employment | Unemployed | 17 | 12.59 | 33 | 23.08 | 2.082 (1.098–3.950) | 0.025 |

| Employed | 118 | 87.41 | 110 | 76.92 | 1.00 | ||

| Family income | <100,000 | 70 | 61.40 | 109 | 92.37 | 7.613 (3.499–16.563) | <0.0001 |

| >100,000 | 44 | 38.60 | 9 | 7.63 | 1.00 | ||

| Residence | Duplex | 5 | 3.68 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.043 (0.004–0.413) | 0.006 |

| 4-bedroom | 7 | 5.15 | 2 | 1.49 | 0.061 (0.011–0.345) | 0.002 | |

| 3-bedroom | 17 | 12.50 | 8 | 5.97 | 0.101 (0.033–0.305) | <0.0001 | |

| 2-bedroom | 65 | 47.79 | 19 | 14.18 | 0.063 (0.026–0.151) | <0.0001 | |

| Self-contained | 33 | 24.26 | 62 | 46.27 | 0.403 (0.175–0.928) | 0.033 | |

| Rooming house | 9 | 6.62 | 42 | 31.34 | 1.00 | ||

| Toilet facility | Pit latrine | 5 | 3.68 | 23 | 16.31 | 0.484 (0.084–2.783) | 0.416 |

| Water closet | 129 | 94.85 | 99 | 70.21 | 0.081 (0.018–0.355) | 0.001 | |

| None | 2 | 1.47 | 19 | 13.48 | 1.00 | ||

(P < 0.05 is significant); COR: crude odds ratios; CI: confidence interval.

Table 3.

The association between medical history and environmental variables and diarrhoea.

| Characteristics | Controls | Cases | COR (95% CI) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | Percentage (%) | Number (n) | Percentage (%) | ||||

| Where was your child born? | At home | 2 | 1.46 | 11 | 7.69 | 1.375 (0.213–8.858) | 0.738 |

| Hospital | 131 | 95.62 | 116 | 81.12 | 0.221 (0.072–0.681) | 0.009 | |

| Traditional maternity centre | 4 | 2.92 | 16 | 11.19 | 1.00 | ||

| How was your child born? | Caesarean section | 34 | 24.82 | 26 | 18.44 | 0.685 (0.385–1.218) | 0.198 |

| Natural birth | 103 | 75.18 | 115 | 81.56 | 1.00 | ||

| Did you receive antenatal care? | Yes | 135 | 98.54 | 107 | 76.98 | 0.050 (0.012–0.211) | <0.0001 |

| No | 2 | 1.46 | 32 | 23.02 | 1.00 | ||

| Was baby breastfed? | Yes | 137 | 100.00 | 142 | 99.30 | ||

| No | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.70 | |||

| Was baby placed on exclusive? | Yes | 105 | 77.21 | 65 | 46.10 | 0.253 (0.150–0.425) | <0.0001 |

| No | 31 | 22.79 | 76 | 53.90 | 1.00 | ||

| If no, how long was the baby breastfed? | <6 Months | 13 | 48.15 | 60 | 80.00 | 4.308 (1.677–11.065) | 0.002 |

| >6 months | 14 | 51.85 | 15 | 20.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Does baby attend a crèche? | Yes | 27 | 19.85 | 45 | 33.58 | 2.041 (1.174–3.549) | 0.011 |

| No | 109 | 80.15 | 89 | 66.42 | 1.00 | ||

| Do you have a babysitter at home? | Yes | 34 | 25.00 | 37 | 27.41 | 1.133 (0.659–1.947) | 0.652 |

| No | 102 | 75.00 | 98 | 72.59 | 1.00 | ||

| Tap water | No | 130 | 94.89 | 122 | 85.31 | 0.313 (0.128–0.762) | 0.011 |

| Yes | 7 | 5.11 | 21 | 14.69 | 1.00 | ||

| Borehole | No | 114 | 83.21 | 104 | 72.73 | 0.538 (0.301–0.961) | 0.036 |

| Yes | 23 | 16.79 | 39 | 27.27 | 1.00 | ||

| Well | No | 137 | 100.00 | 143 | 100.00 | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| Sachet water | No | 105 | 76.64 | 59 | 41.26 | 0.214 (0.128–0.359) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 32 | 23.36 | 84 | 58.74 | 1.00 | ||

| Bottled water | No | 86 | 62.77 | 116 | 81.12 | 2.548 (1.480–4.387) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 51 | 37.23 | 27 | 18.88 | 1.00 | ||

| Boiled water | No | 100 | 72.99 | 109 | 76.22 | 1.186 (0.692–2.033) | 0.535 |

| Yes | 37 | 27.01 | 34 | 23.78 | 1.00 | ||

| Rainwater | No | 137 | 100.00 | 134 | 93.71 | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0.00 | 9 | 6.29 | |||

| River or stream | No | 137 | 100.00 | 143 | 100.00 | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| Do you keep pets? | Yes | 15 | 11.03 | 21 | 15.00 | 1.424 (0.700–2.893) | 0.329 |

| No | 121 | 88.97 | 119 | 85.00 | |||

P < 0.05 is significant; COR: crude odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis of mothers/caregivers' sociodemographic status.

| Characteristics | Diarrhoea status | AOR (95% CI) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (%) | Cases (%) | ||||

| Mother's age | <30 | 34.31 | 31.69 | 0.435 (0.179 – 1.056) | 0.066 |

| >30 | 65.69 | 68.31 | 1.00 | ||

| Religion | Christianity | 85.29 | 51.75 | 0.200 (0.070 – 0.569) | 0.003 |

| Islam | 14.71 | 48.25 | 1.00 | ||

| Educational status | Below tertiary | 20.00 | 74.13 | 10.908 (40.62 – 29.291) | <0.0001 |

| Tertiary | 80.00 | 25.87 | 1.00 | ||

| Employment | Unemployed | 12.59 | 23.08 | 4.374 (1.453 – 13.165) | 0.009 |

| Employed | 87.41 | 76.92 | 1.00 | ||

| Income | <100,000 | 61.40 | 92.37 | 4.342 (1.364 – 13.821) | 0.013 |

| >100,000 | 38.60 | 7.63 | 1.00 | ||

| Residence | Duplex | 3.68 | 0.75 | 0.000 | |

| 4 – bedroom | 5.15 | 1.49 | 1.55 (0.10 – 2.398) | 0.182 | |

| 3 – bedroom | 12.50 | 5.97 | 1.540 (0.241 – 9.861) | 0.648 | |

| 2 – bedroom | 47.79 | 14.18 | 1.773 (0.320 – 9.832) | 0.512 | |

| Self-contained | 24.26 | 46.27 | 2.157 (0.467 – 9.957) | 0.325 | |

| Rooming house | 6.62 | 31.34 | 1.00 | ||

| Toilet facility | Pit latrine | 3.68 | 16.31 | NC | |

| Water closet | 94.85 | 70.21 | 0.153 (0.022 – 1.045) | 0.055 | |

| None | 1.47 | 13.48 | 1.00 | ||

(AOR: p < 0.005 is significant). AOR: adjusted odds ratios; CI: confidence interval.

Table 5.

Multivariate Analysis of medical history and the environment as risk factors or diarrhoea in the study.

| Characteristics | AOR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Where was the baby born? | At home | 5.381 (0.45963.063) | 0.180 |

| Hospital | 0.815 (0.185–3.603) | 0.788 | |

| Traditional maternity centre | 1.00 | ||

| How was your child born? | Caesarean section | 1.644 (0.730–3.699) | 0.230 |

| Natural birth | 1.00 | ||

| Did you receive antenatal care? | Yes | 0.131 (0.026–0.659) | 0.014 |

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Was the baby placed on exclusive breastfeeding? | Yes | 0.314 (0.154–0.641) | 0.001 |

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Does the baby attend crèche? | Yes | 1.244 (0.599–2.583) | 0.557 |

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Is there a baby sitter or nanny at home? | Yes | 0.746 (0.350–1.589) | 0.447 |

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Tap water | No | 0.784 (0.238–2.584) | 0.690 |

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| Borehole | No | 0.252 (0.105–0.606) | 0.002 |

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| Sachet water | No | 0.130 (0.063–0.267) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| Bottled water | No | 2.658 (1.226–5.762) | 0.013 |

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| Boiled water | No | 1.128 (0.537–2.367) | 0.751 |

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| Do you keep pets | Yes | 0.971 (0.385–2.446) | 0.950 |

| No | 1.00 | ||

(AOR: p < 0.005 is significant). AOR: adjusted odds ratios.

Table 6.

Summary of Multivariate analysis of selected variables.

| Characteristics | AOR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religion | Christianity | 0.159 (0.055–0.462) | 0.001 |

| Islam | 1.00 | ||

| Education | Below tertiary | 10.282 (4.369–24.198) | <0.0001 |

| Tertiary | 1.00 | ||

| Income | <100,000 | 6.908 (2.266–21.055) | 0.001 |

| >100,000 | 1.00 | ||

| Where was your baby born? | At home | 5.280 (0.150–185.695) | 0.360 |

| Hospital | 0.893 (0.091–8.781) | 0.923 | |

| Traditional | 1.00 | ||

| Maternity centre | |||

| Did you receive antenatal care during pregnancy? | Yes | 0.418 (0.069–2.550) | 0.344 |

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Do you keep your baby in crèche? | Yes | 2.418 (0.974–6.002) | 0.057 |

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Tap water | No | 0.249 (0.046–1.343) | 0.106 |

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| Sachet | No | 0.213 (0.091–0.498) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| Bottled water | No | 1.400 (0.568–3.451) | 0.465 |

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

(AOR: p < 0.005 is significant); AOR: adjusted odds ratios.

Table 1 shows the relationship between the age group and gender of the children and diarrhoea occurrence in the study area. These two variables were similar in both case and control groups, and there was no significant relationship between the age (COR = 0.359, CI = 0.101 – 1.274, p=0.113) and gender (COR = 1.245, CI = 0.774 – 2.003, p=0.366) of the children with diarrhoea occurrence in the study area.

Table 2 depicts the sociodemographic characteristics of caregivers or mothers for the case and control groups. All variables were significantly different between the case and control except for the age of the mothers. Results showed that there were significant relationships between diarrhoea occurrence and: mother's religion (OR = 0.185, p=0.0001), mother's educational status (OR = 11.459, p=0.0001), mother's employment status (OR = 2.082, p=0.025), and family income (OR = 7.613, p=0.0001).

Table 3 presents the medical history and environmental variables as risk factors for diarrhoea. There were significant relationships between where the child was born (OR = 0.221. p=0.009), mother's antenatal attendance (OR = 0.05, p=0.0001), exclusive breastfeeding (OR = 0.25, p=0.0001), reduced breastfeeding (OR = 4.3, p=0.002), and crèche attendance (OR = 2.04, p=0.011) and the occurrence of diarrhoea in this study. Children not exposed to drinking tap water (OR = 0.313, p=0.011), borehole (OR = 0.538, p=0.036), and sachets (OR = 0.214, p=0.0001) were less likely to have diarrhoea, whereas those that drank bottled water (OR = 2.548, p=0.001) were two times less likely to have diarrhoea (Table 3).

Tables 4 and 5 showed the values of the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of the variables. Some of the variables shown to be statistically significant using crude odds ratios were also significant after being adjusted. Thus, the results revealed that the mother's level of education (AOR = 10.282, p=0.0001) and family income (AOR = 6.908, p=0.001) have a significant relationship with diarrhoea occurrence in children under five years of age (Table 6).

5. Discussion

This study identified three significant risk factors that could predispose children under age five to diarrhoea occurrence. These factors are: mother's educational status (OR = 11.46, P=0.0001), mother's employment status (OR = 2.08, P=0.025), and family income (OR = 7.61, P=0.0001). Other factors are the mother's antenatal attendance, duration of breastfeeding, child's crèche attendance, and source of drinking water.

The observation that children born by mothers with at most primary education is more likely to have diarrhoea than a child of a more educated mother supports other studies conducted in Lagos (Akinyemi, 2019), Osun, and Oyo States [25]. Literacy has been earmarked consistently as a major determinant of health in any population, especially with regard to female education. Educated women have a better understanding of personal hygiene, nutrition and are more knowledgeable about accessing the healthcare system. [26], concluded in one of their studies that maternal education is the most important risk factor to diarrhoea prevalence among children under five years of age in Nigeria.

Family income is a major risk factor of diarrhoea prevalence among children. This study revealed that a child from a family with reduced income is more likely to have diarrhoea than a child from a financially comfortable home. This study agrees with the findings of [19], in which low monthly household income had a significant association with childhood diarrhoea in Southwest Nigeria. Reference [25] concluded that low socioeconomic status impedes the health of children under age five in Southwest Nigeria. Global reports highlight the impact of poverty on the burden of diarrhoea disease prevalence among children [27, 28]. Reduced income subjects a family to poor living conditions such as lack of access to potable drinking water, improper sewage disposal, poor drainage system, and toilet facilities which have been identified as risk factors of childhood diarrhoea [29, 30]. The observation that children of unemployed mothers are twice likely to have diarrhoea than children of employed mothers (Table 2) is similar to findings of [31], which further corroborates the impact of poverty on childhood diarrhoea incidence. This implies that mothers generate more income for the family, thereby providing basic household sanitary materials that ensure hygienic living conditions for the children.

Bivariate logistics regression identified the mother's antenatal attendance, breastfeeding, and source of drinking water as protective factors of diarrhoea prevalence in children. Lack of access to potable water is a key player in the transmission of diarrhoeal diseases because unclean water harbours diarrhoeagenic pathogens. Studies from Southwest Nigeria have implicated faecal contamination of the water used for domestic purposes [32–35]. The level of microbial contamination of the water used for domestic purposes is higher in Lagos State than Ogun state because of the high population, thus leading to poor management of wastes, which could lead to pollution of water aquifers [32, 36]. This may be the reason for the high prevalence rate of diarrhoea in Lagos state (13.4%) than Ogun State (2%). Some of the drinking water (sachets) consumed in Lagos State are from unprotected sources [37, 38].

Exclusive breastfeeding confers immunity against diarrhoea in children below the age of five. This study revealed that children placed on exclusive breastfeeding were less likely to suffer from diarrhoeal diseases, while those fed with breastmilk for less than six months were more likely to have diarrhoea [39–41]. WHO and UNICEF recommend exclusive breastfeeding of infants for up to the first six months of life because of the nutritional and immunological value it provides to the child. Besides, breastfeeding helps to improve the cognitive and sensory development in infants. Besides, breastfeeding can protect a child against chronic and infectious diseases such as diarrhoea and pneumonia in children younger than five years of age. Breastfeeding has a huge impact on the health status of children. A significant correlation exists between breastfeeding and diarrhoea episodes [42, 43]. Suboptimal breastfeeding increases the risk of developing diarrhoea because breast milk can confer the proper functioning of the gut immune system in infants, both for a short- and long-term duration [44, 45]. Besides, breast milk contains antibodies, immunoglobulin A (IgA), which confer protection against pathogenic bacteria and harmonise the activity of white blood cells [46, 47].

6. Conclusion

This study strongly supports the fact that socioeconomic factors are significant determinants of childhood diarrhoea. Female education should be encouraged by the right government policy to achieve child favourable health outcomes in the future. Thus, the achievement of the sustainable development goal (SDG) 3 for a possible reduction of neonates and infants' deaths in Nigeria.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of Massey Street Children Hospital Lagos Island, Orile-Agege General Hospital Agege, State Hospital Ota, and Federal Medical Centre Abeokuta, for their support. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the study participants for their cooperation and participation during the data collection. Their deep gratitude also goes to Covenant University, Ota for defraying the cost of this publication.

Data Availability

The data supporting the results of this study are included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

All authors participated in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The Treatment of Diarrhoea: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2005. pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. 2017. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease.

- 3.Walker C. L. F., Perin J., Aryee M. J., Boschi-Pinto C., Black R. E. Diarrhea incidence in low-and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang S. X., Zhou Y. M., Xu W., Tian L. G., Chen J. X., Chen S. H. Impact of co-infections with enteric pathogens on children suffering from acute diarrhea in southwest China. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2016;5(1):p. 64. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0157-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Platts-Mills J. A., Babji S., Bodhidatta L., et al. Pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhoea in developing countries: a multisite birth cohort study (MAL-ED) The Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(9):e564–e575. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(15)00151-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotloff K. L. The burden and etiology of diarrheal illness in developing countries. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2017;64(4):799–814. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ugboko H. U., Nwinyi O. C., Oranusi S. U., Oyewale J. O. Childhood diarrhoeal diseases in developing countries. Heliyon. 2020;6(4) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04040.e03690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakravarty I., Bhattacharya A., Das S. Water, sanitation and hygiene: the unfinished agenda in the world health organization south-east asia region. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health. 2017;6(2):p. 22. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.213787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Squire S. A., Ryan U. Cryptosporidium and Giardia in Africa: current and future challenges. Parasites and Vectors. 2017;10(1):p. 195. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2111-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omole D. O., Emenike C. P., Tenebe I. T., Akinde A. O., Badejo A. A. An assessment of water related diseases in a Nigerian community. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology. 2015;10(7):776–781. doi: 10.19026/rjaset.10.2430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olayinka A. A., Oginni I. O. Temporary removal: association of atypical Enteric pathogens in childhood diarrhoea in Ile-Ife, southwestern Nigeria. New Microbes and New Infections. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2019.100647.100647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okeke I. N., Lamikanra A., Steinrück H., Kaper J. B. Characterisation of Escherichia coli strains from cases of childhood diarrhea in provincial southwestern Nigeria. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2000;38(1):7–12. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.7-12.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Efuntoye M. O., Adenuga A. Shigella Serotypes among nursery and primary school children with diarrhea in Ago-Iwoye and Ijebu-Igbo, Southwestern Nigeria. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2011;2:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akingbade O. A., Akinjinmi A. A., Ezechukwu U. S., Okerentugba P. O., Okonko I. O. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among children with diarrhea in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. Researcher. 2013;5(9):66–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odetoyin B. W., Hofmann J., Aboderin A. O., Okeke I. N. Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli in mother-child pairs in ile-ife, South western Nigeria. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015;16(1):p. 28. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1365-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adebolu T. T., Oladimeji S. A. Antimicrobial activity of leaf extracts of Ocimum gratissimum on selected diarrhea causing bacteria in southwestern Nigeria. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2005;4(7):682–684. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agu G. C., Thomas B. T., Agu N. C., Agbolade O. M. Prevalence of diarrhoea agents and the in-vitro effects of three plant extracts on the growth of the isolates. American Journal of Research Communication. 1(12):429–444. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shosan L. O., Fawibe O. O., Ajiboye A. A., Abeegunrin T. A., Agboola D. A. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in curing some diseases in infants in Abeokuta South Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria. American Journal of Plant Sciences. 2014;05(21):p. 3258. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2014.521340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oloruntoba E. O., Folarin T. B., Ayede A. I. Hygiene and sanitation risk factors of diarrhoeal disease among under-five children in Ibadan, Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 2014;14(4):1001–1011. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i4.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akinyemi Y. C. Spatial pattern and determinants of diarrhoea morbidity among under-five-aged children in Lagos State, Nigeria. Cities & Health. 2019:1–12. doi: 10.1080/23748834.2019.1615162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koce F., Randhawa G., Ochieng B. Understanding healthcare self-referral in Nigeria from the service users’ perspective: a qualitative study of Niger state. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19:p. 209. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4046-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. http://ciuci.us/massey-street-childrens-hospital/

- 23. https://servicom.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Federal-Ministry-of-Health-General-out-Patient-Department-of-Federal-Medical-Centre-Abeokuta.pdf.

- 24. https://fmcabeokuta.net/

- 25.Mesagan P. E., Adeniji-Ilori O. M. Household environmental factors and childhood morbidity in South-western Nigeria. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences. 2018;11(3):411–425. doi: 10.1007/s40647-017-0204-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desmennu A. T., Oluwasanu M. M., John-Akinola Y. O., Oladunni O., Adebowale S. A. Maternal education and diarrhea among children aged 0-24 months in Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2017;21(3):27–36. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotloff K. L., Platts-Mills J. A., Nasrin D., Roose A., Blackwelder W. C., Levine M. M. Global burden of diarrheal diseases among children in developing countries: incidence, etiology, and insights from new molecular diagnostic techniques. Vaccine. 2017;35(49):6783–6789. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He Z., Bishwajit G., Yaya S., Cheng Z., Zou D., Zhou Y. Prevalence of low birth weight and its association with maternal body weight status in selected countries in Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020410.e020410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mihrete T. S., Alemie G. A., Teferra A. S. Determinants of childhood diarrhea among under-five children in Benishangul Gumuz regional state, North West Ethiopia. BMC Pediatrics. 2014;14(1):p. 102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yaya S., Hudani A., Udenigwe O., Shah V., Ekholuenetale M., Bishwajit G. Improving water, sanitation and hygiene practices, and housing quality to prevent diarrhea among under-five children in Nigeria. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2018;3(2):p. 41. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed3020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akinyemi A. I., Fagbamigbe A. F., Omoluabi E., Agunbiade O. M., Adebayo S. O. Diarrhoea management practices and child health outcomes in Nigeria: sub-national analysis. Advances in Integrative Medicine. 2018;5(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.aimed.2017.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Omezuruike O. I., Damilola A. O., Adeola O. T., Fajobi E. A., Shittu O. B. Microbiological and physicochemical analysis of different water samples used for domestic purposes in Abeokuta and Ojota, Lagos State, Nigeria. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2008;7(5):617–621. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chinedu S., Nwinyi O., Oluwadamisi A. Y., Eze V. N. Assessment of water quality in Canaanland, Ota, southwest Nigeria. Agriculture and Biology Journal of North America. 2011;2(4):577–583. doi: 10.5251/abjna.2011.2.4.577.583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owolabi A. A. Domestic water use, sanitation, and diarrhea incidence among various communities of Ikare Akoko, Southwestern, Nigeria. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2012;6(14):3465–3479. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sogbanmu T. O., Aitsegame S. O., Otubanjo O. A., Odiyo J. O. Drinking water quality and human health risk evaluations in rural and urban areas of Ibeju-Lekki and Epe local government areas, Lagos, Nigeria. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal. 2020;26(4):1062–1075. doi: 10.1080/10807039.2018.1554428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohwo O. The impact of pipe distribution network on the quality of tap water in Ojota, Lagos State, Nigeria. American Journal of Water Resources. 2014;2(5):110–117. doi: 10.12691/ajwr-2-5-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olajuyigbe A. E., Rotowa O. O., Adewumi I. J. Water vending in Nigeria-A case study of FESTAC town, Lagos, Nigeria. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 2012;3(1):229–239. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogunware A. E., Adedigba P. A., Oyende Y. E., Adekoya A. A., Daramola A. R. Physicochemical, bacteriological and biochemical assessment of water samples from unprotected wells in Lagos state metropolis. Asian Journal of Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2020:24–36. doi: 10.9734/ajbgmb/2020/v3i430092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bbaale E. Determinants of diarrhoea and acute respiratory infection among under-fives in Uganda. Australasian Medical Journal. 2011;4(7):p. 400. doi: 10.4066/amj.2011.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yilgwan C., Okolo S. Prevalence of diarrhea disease and risk factors in jos university teaching hospital, Nigeria. Annals of African Medicine. 2012;11(4):p. 217. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.102852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frimpong M. A. Exclusive Breastfeeding Practice Among Formally and Informally Employed Nursing Mothers Attending Child Welfare Clinic at Mamprobi Polyclinic. Accra, Ghana: Doctoral dissertation, University of Ghana; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Godana W., Mengistie B. Determinants of acute diarrhea among children under five years of age in Derashe District, Southern Ethiopia. Rural & Remote Health. 2013;13(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siregar A. Y., Pitriyan P., Walters D. The annual cost of not breastfeeding in Indonesia: the economic burden of treating diarrhea and respiratory disease among children (< 24mo) due to not breastfeeding according to the recommendation. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2018;13(1):p. 10. doi: 10.1186/s13006-018-0152-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartick M. C., Jegier B. J., Green B. D., Schwarz E. B., Reinhold A. G., Stuebe A. M. Disparities in breastfeeding: impact on maternal and child health outcomes and costs. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2017;181:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogbo F. A., Nguyen H., Naz S., Agho K. E., Page A. The association between infant and young child feeding practices and diarrhea in Tanzanian children. Tropical Medicine and Health. 2018;46(1):p. 2. doi: 10.1186/s41182-018-0084-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willey J., Sherwood L., Wolverton C. Prescott’s Microbiology. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill; 2013. pp. 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hennet T., Borsig L. Breastfed at tiffany’s. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2016;41(6):508–518. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baqui A. H., Black R. E., Yunus M., Hoque A. R. A., Chowdhury H. R., Sack R. B. Methodological issues in diarrhoeal diseases epidemiology: definition of diarrhoeal episodes. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1991;20(4):1057–1063. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.4.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study are included in the manuscript.