Introduction

Of the many study designs used in nutrition science, the randomized clinical trial (RCT) is largely held in highest regard for its clinical relevance and ability to address cause and effect relationships. Researchers utilize RCTs to provide scientific evidence addressing controversial topics about what to eat or avoid. However, RCTs have their own challenges, particularly when it comes to comparing 2 diet types or patterns - e.g. Diet A vs. Diet B.1 A better understanding and appreciation of these challenges and limitations can help show how seemingly conflicting, confusing and controversial findings are often more aligned and consistent than it may seem.

Definition

Over the last decade, many health professionals and organizations have shifted the focus of nutrition recommendations from isolated nutrients and foods to overall dietary patterns in an effort to move away from reductionism and toward greater generalizability. Within RCTs, this trend has brought its own challenges. While dietary patterns may have the benefit of being more generalizable than nutrients and foods, they are also inherently more vague. Most dietary patterns lack scientific consensus on their specific definition. This can result in studies using divergent definitions for what might appear to be the same diet pattern, which then leads to divergent findings.

Examples

One classic debate of the last decade has been “Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb.” But how low is “Low”? A review of published studies designed to compare these 2 approaches reveals a wide variety of definitions under the same name: Low-Fat diets tend to be defined in the range of 10% to 30% of daily energy intake, and Low-Carb diets from 5% to 40% (Table 1). The lowest end of the range in both cases dips to an extreme so low (10% fat or 5% carbohydrate) that many individuals find such a diet difficult to achieve and maintain, while the higher end (30% fat or 40% carbohydrate) is close to current average consumption levels in the US.

Table 1.

Differing Definitions of Low-Carb and Low-Fat Diets in Selected Studies and Reports.

| Publication | Definition of low-carb diet | Definition of low-fat diet |

|---|---|---|

| Bazzano et al. (2014)2 | ≤ 40 g of carbs/day | ≤ 30% fat |

| Gardner et al. (2007)3 | ≤ 40% carb (Zone diet) ≤ 20 g of carbs/day for 1st 2 months and then ≤ 50 g of carbs/day for remainder (Atkins diet) |

≤ 10% fat (Ornish diet) |

| Sacks et al. (2009)4 | Lowest amount of carb among 4 study diets was ≤ 35% carb | Lowest amount of fat among 4 study diets was ≤ 20% fat |

| Shai et al. (2008)5 | ≤ 20 g of carbs/day for 1st 2 months and then ≤ 120 g of carbs/day for remainder | ≤ 30% fat |

| Kirkland et al. (2019)6 | ≤ 5%–10% carb |

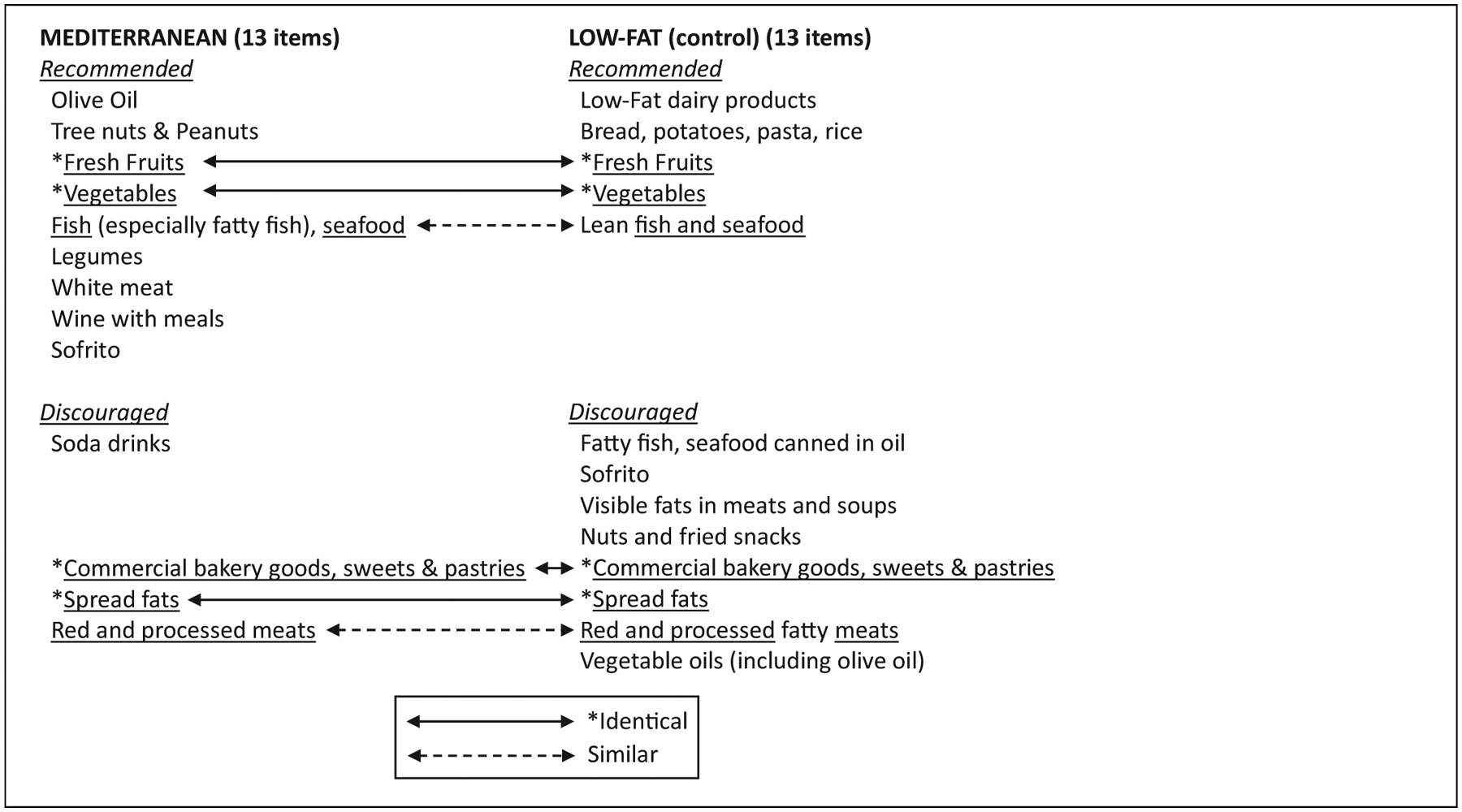

Another example is the Mediterranean diet. Many published studies have tested the potential benefits of a Mediterranean diet, and yet the specific characteristics of this diet defined by various investigators differs substantially.7–9 In the landmark PREDIMED study, there were 13 specific descriptors of what to include vs. avoid. In that study the Mediterranean diet was being contrasted to a Low-Fat diet, which also had 13 specific descriptors.7,10 Interestingly, 4 of the 13 descriptors were identical for both diets, and 2 were similar (Table 2). In their weight loss study comparing the Mediterranean diet to Low-Fat and Low-Carb, Shai et al defined Mediterranean as: “Rich in vegetables and low in red meat, with poultry and fish replacing beef and lamb, with a goal of no more than 35% of calories from fat; the main sources of added fat were 30 to 45 g of olive oil and a handful of nuts (five to seven nuts, <20 g) per day.”5 A commonly used Mediterranean diet score involves 9 categories that are similar, but not identical, to PREDIMED (include vegetables, fruits and nuts, legumes, cereals, and fish; avoid meat, poultry and dairy; include some but not too much alcohol).11

Table 2.

Defining factors used for the Mediterranean and Low-Fat diets.

|

Therefore, one potential reason for different findings from different studies that have used Low-Fat, Low-Carb, or Mediterranean diet patterns in their comparisons, is that they started with different definitions.

Recommendations

It should not be assumed that all diet patterns under the same name are equal or comparable. When interpreting and comparing study results to each other, it is important to review the methods sections for the complete definitions of the intended diet types or patterns. Investigators could also clearly qualify their definitions as extreme, moderate, or ho-hum/meh categories to provide greater transparency into studies.

Adherence

Another important factor to consider when interpreting study results is how well the participants adhered to the original definition of their assigned diet (Table 3). If study participants were assigned to eat more of this and less of that and they didn’t, then it becomes difficult to draw meaningful conclusions about that particular diet type’s effects.

Table 3.

Comparison of Intended/Designed vs. Actual Dietary Adherence for Selected Diet Groups of Selected Studies (in grams or percent energy intake/day).

| Study | Diet as defined | Actual dietary adherence at the end of the intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Gardner et al. (2007)3 | Atkins diet: ≤ 50 g of carbs/day Ornish diet: ≤ 10% fat |

Atkins diet: ~140 g of carbs/day Ornish diet: ~30% fat |

| Sacks et al. (2009)4 | 2 High-protein groups: ~25% protein 2 Average-protein groups: ~15% protein |

High-protein groups: ~20.8% and 21.2% Average-protein groups: ~19.6% protein (both groups) |

| Bazzano et al. (2014)2 | Low-carb diet: ≤ 40 g of carbs/day | Low-carb diet: ~120 g of carbs/day |

| Estruch et al. (2018)7 | Low-fat diet: Recommended to include ≥3 servings/day low-fat dairy products, ≥3 servings/day of fresh fruits and vegetables, and ≥3 servings/week of lean fish. Recommended to avoid red meat, fatty fish, vegetable oils, nuts and fried snacks, and sweets and pastries | Low-fat diet: ~37% fat |

Examples

In one of our own previous studies, the A to Z Study,3 we randomly assigned 311 women to follow either an Atkins, Zone, LEARN, or Ornish diet for a year. Each participant was given a book describing the diet (i.e., the books published by the original creators of the diet plans). For 8 weeks, the participants attended weekly group classes led by a dietitian who reviewed the contents of their assigned diet. Then they were left on their own to do their best following the diets for another 10 months. Adherence varied among women within each diet type, but average adherence was worst for the 2 extreme diets - the low-carbohydrate Atkins diet, and the low-fat Ornish diet. The prescribed upper limit of carbohydrate intake for the Atkins diet was 50 grams, but at the 12-month time point the average reported carbohydrate intake was 140 grams/day. The prescribed fat intake for the Ornish diet was 10% of calories, but at the 12-month time point the average reported fat intake was 30% of calories. Rather than reporting our results in terms of what happened when the women “followed” the 4 diets, we were careful to indicate that our results reflected what happened to women who were “assigned” to the 4 diets.

In the PREDIMED study,7 the comparison diet was described, by design, as a “Low-Fat” diet. However, based on the diet assessment data that were collected, the comparison group was consuming 37% of their calories from fat - a level that wouldn’t be classified as “Low-Fat” by any health professional.

The landmark POUNDS LOST study4 involved approximately 800 participants randomly assigned to 1 of 4 groups for 2 years with 4 different combinations of fats, protein and carbohydrate. The investigators chose 2 levels of fat (20% vs. 40%), 2 levels of protein (15% vs. 25%) and to make all the totals add up to 100%, this meant 4 levels of carbohydrate (35%, 45%, 55% and 65%). The proportions of the 4 diet assignments were as follows:

A: 20:15:65 – Low fat, low protein, high carb

B: 20:25:55 – Low fat, high protein, moderate carb

C: 40:15:45 – High fat, low protein, moderate carb

D: 40:25:35 – High fat, high protein, low carb

This is truly an elegant design in representing low vs. high levels of, fat, protein and carbohydrate, all in one study. But it was also very challenging in terms of adherence. Those specific percentages proved hard to achieve on a daily basis over the study’s 2-year duration. With regard to protein in particular, the average protein level at 2 years across all 4 diet groups ranged from a low of 19.6% to a high of 21.2%, a far cry from the designed difference of 15% vs. 25%. The study did achieve meaningful differences in fat and carbohydrate between the groups, but the magnitude of the differences was much more modest than the design proposed.

Recommendations

Checking for adherence levels in a study is dependent on having conducted dietary assessments. We note that not all studies do this. The types of dietary assessment can vary, but the most meaningful and accurate types of assessments can be expensive and involve substantial participant burden; we still highly recommend this. When these are not done, evaluating diet adherence is impossible, making it difficult to include this factor when trying to determine what might explain different findings from 2 studies testing diet patterns that have the same name.12 Look closely at any available adherence data to determine the extent to which study participants were or were not following the diets as intended. Also, keep in mind that lack of adherence isn’t necessarily an indicator of weak scientific conduct - it may reflect important behavioral or biological factors that should be taken into consideration.

Design

When designing a study to compare the health effects of Diet A vs. Diet B, a truly meaningful and informative comparison requires giving each diet an equal opportunity to succeed. Ideally, both diets would be designed to be exemplary such that if external proponents of Diet A and Diet B were to review study design and implementation, they would concur that their preferred diet was given a fair chance to succeed. The opposite of this would be to set up one diet type as a “straw man” to knock over, meaning one of the 2 diets is designed to meet the technical definition of a specific diet type, but be a low-quality version. This would increase the likelihood of that diet faring poorly relative to a higher quality comparison diet.

Examples

A variation on this theme is to design a comparison of 2 diet patterns that involve unequal demands of the participants. An example of this would be a 2014 comparison of Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb that defined “Low-Fat” as <30% of energy from fat, and “Low-Carb” as <40 g carbohydrate/day.2 The pre-study diets of the participants were defined as being ~35% fat, and ~240 g carbohydrate. For the Low-Fat group, shifting from 35% to 30% of calories represented a relatively modest shift. In fact, that 35% pre-study level was simply an average, and the average included some participants whose diets were already <30% fat, and therefore they were already “adherent” to that study’s definition of Low-Fat without making any dietary changes. In contrast, for the Low-Carb group, shifting from 240 to 40 g represented a goal of eliminating ~85% of pre-study carbohydrate intake - a daunting dietary modification. Trying to meet the Low-Carb guideline required substantially more participant attention to their daily food choices. The need to pay closer attention to making dietary changes in Low-Carb vs. Low-Fat is a differentiating factor that should be taken into consideration when interpreting the conclusion in this study that the Low-Carb diet was more effective for weight loss relative to Low-Fat.

Additional considerations for interpreting the conclusions from the same 2014 study can be made based on the reported dietary assessments.2 To their credit, these investigators conducted assessments and provided diet data for the end of the 12 month study. For the Low-Fat group, the average reported % Fat was on target at 29.8%, although as noted above, this was a relatively modest change from the pre-study 35% fat. In contrast, the Low-Carb group reported an average 127 grams of carb at 12 months, which represented a decrease of ~50% of their pre-study carbohydrate intake, but a level that was >3-fold higher than the study’s defined level of <40 g.

Another interesting finding from the table of nutrient data was the total fiber level for the 2 groups at 12 months: virtually identical at 15.6 and 15.2 g fiber/day for Low-Fat and Low-Carb, respectively. This is of interest because recommendations for an exemplary Low-Fat diet would include high fiber sources from vegetables, legumes, fruits and whole grains. In order for the Low-Carb group to try to achieve an intake of <40 g carbohydrate/day, participants would have been instructed to restrict many of those high fiber sources that are the primary contributors to carbohydrates. In other words, a difference in fiber intake favoring a higher intake for the Low-Fat group would be expected. This suggests that the relatively low fiber intake on a Low-Fat diet was achieved by allowing for added sugars and refined grains, which technically meet the definition of “Low-Fat,” but would not be considered part of an exemplary Low-Fat diet. It appears that by design, the Low-Fat diet may have been set up to be a “straw man” comparator for the more intensive Low-Carb diet.

Recommendations

In order to provide fair and objective comparisons, investigators should design their studies of diet types to include exemplary diets that are comparable in their demands of participants. Readers should determine if the diet types, as designed and implemented, were fair comparisons of exemplary diets, or if any of the study diets appear to be designed with some degree of bias, such as a straw man diet comparison.

Recommendations for Better Nutrition Science and Being More Effectively Critical

It can be challenging to distinguish reliable food and nutrition research from weak studies and sensational headlines, particularly when those studies fall into the category of comparing one diet pattern to another. Being effectively critical means going beyond the title and main conclusion of a study. This perspective provided examples of 3 challenges of RCTs comparing diet types or patterns as well as recommendations to address these limitations. These recommendations are aspects of study design and conduct that our research group had in mind for 2 of our recently completed studies, DIETFITS and SWAP-MEAT. The research group led by Dr. Kevin Hall has also published recent studies that we believe are examples of this type of strong study design and conduct.13–15 We believe much of the current confusion arising from head to head comparisons of different diet types could be resolved if future studies addressed these issues more effectively and transparently. In the meantime, we hope these tips will help critical readers to realize that many times what appear to be conflicting conclusions from similar studies are actually logically different conclusions from studies that are not as similar in design and conduct as titles and headlines would suggest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Clinical & Translational Core of the Stanford Diabetes Research Center (P30DK116074). Drs. Crimarco, Landry and Fielding-Singh were supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute NIH T32HL007034.

References

- 1.Hébert JR, Frongillo EA, Adams SA, et al. Perspective: randomized controlled trials are not a panacea for diet-related research. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(3):423–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazzano LA, Hu T, Reynolds K, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 161(5):309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner CD, Kiazand A, Alhassan S, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: the A TO Z Weight Loss Study: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007; 297(9):969–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(9):859–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359(3):229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkpatrick CF, Bolick JP, Kris-Etherton PM, et al. Review of current evidence and clinical recommendations on the effects of low-carbohydrate and very-low-carbohydrate (including ketogenic) diets for the management of body weight and other cardiometabolic risk factors: a scientific statement from the National Lipid Association Nutrition and Lifestyle Task Force. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13(5):689–711. e681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25): e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinu M, Pagliai G, Casini A, Sofi F. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72(1):30–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis C, Bryan J, Hodgson J, Murphy K. Definition of the Mediterranean diet; a literature review. Nutrients. 2015;7(11): 9139–9153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2599–2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(3): 147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crimarco A, Springfield S, Petlura C, et al. A randomized crossover trial on the effect of plant-based compared with animal-based meat on trimethylamine-N-oxide and cardiovascular disease risk factors in generally healthy adults: Study With Appetizing Plantfood—Meat Eating Alternative Trial (SWAP-MEAT) [published online August 11, 2020]. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardner CD, Trepanowski JF, Del Gobbo LC, et al. Effect of low-fat vs low-carbohydrate diet on 12-month weight loss in overweight adults and the association with genotype pattern or insulin secretion: the DIETFITS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018; 319(7):667–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019; 30(1):67–77. e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]