Abstract

Background

Chronic respiratory diseases (CRD) are common among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Objectives

We sought to determine the association between CRD (including disease overlap) and the clinical outcomes of COVID-19.

Methods

Data of diagnoses, comorbidities, medications, laboratory results, and clinical outcomes were extracted from the national COVID-19 reporting system. CRD was diagnosed based on International Classification of Diseases-10 codes. The primary endpoint was the composite outcome of needing invasive ventilation, admission to intensive care unit, or death within 30 days after hospitalization. The secondary endpoint was death within 30 days after hospitalization.

Results

We included 39,420 laboratory-confirmed patients from the electronic medical records as of May 6, 2020. Any CRD and CRD overlap was present in 2.8% and 0.2% of patients, respectively. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was most common (56.6%), followed by bronchiectasis (27.9%) and asthma (21.7%). COPD-bronchiectasis overlap was the most common combination (50.7%), followed by COPD-asthma (36.2%) and asthma-bronchiectasis overlap (15.9%). After adjustment for age, sex, and other systemic comorbidities, patients with COPD (odds ratio [OR]: 1.71, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.44-2.03) and asthma (OR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.05-1.98), but not bronchiectasis, were more likely to reach to the composite endpoint compared with those without at day 30 after hospitalization. Patients with CRD were not associated with a greater likelihood of dying from COVID-19 compared with those without. Patients with CRD overlap did not have a greater risk of reaching the composite endpoint compared with those without.

Conclusion

CRD was associated with the risk of reaching the composite endpoint, but not death, of COVID-19.

Key words: Asthma, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Bronchiectasis, Death, Composite endpoint

Abbreviations used: CI, Confidence interval; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CRD, Chronic respiratory disease; EMR, Electronic medical records; OR, Odds ratio

What is already known on this topic? The impact of chronic respiratory diseases (CRD) on severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the risk of death remains controversial.

What does this article add to our knowledge? Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma were more likely to reach the composite endpoint (needing invasive ventilation, admission to intensive care unit, or death within 30 days after hospitalization) compared with those without, after adjusting for age, sex, and other systemic comorbidities. However, patients with CRD did not have an increased risk of death compared with those without.

How does this study impact current management guidelines? Both COPD and asthma are important risk factors of poor clinical outcomes but not death in patients with COVID-19.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a severe acute respiratory disease that occurs globally, resulting in more than 53,000,000 laboratory-confirmed cases and 1,300,000 deaths as of early November, according to the World Health Organization.1 COVID-19 is a highly heterogeneous disease that ranges from mild diseases that could be asymptomatic to a critical illness that might rapidly progress to death.2 , 3 Early identification of the risk factors that predispose to poor clinical outcomes of COVID-19 may help early triage of patients and improve the prognosis.4

An important predictor of the risk of progression to severe or critical illness has been the presence, category, and number of comorbidities.5, 6, 7, 8 Comorbidities were reportedly common among patients with COVID-19 and correlated significantly with the clinical outcomes.5, 6, 7, 8 According to a modeling study, approximately 20% of the world's population could have an increased risk of developing severe COVID-19, with the presence of at least 1 comorbidity being an important contributing factor.9 Although the impact of major cardiovascular and metabolic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes on the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 has been mostly consistent, the findings regarding respiratory comorbidities remain less clear. A recent study documented a contrasting impact of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on the risk of death in 961 hospitalized patients with COVID-19.6 A meta-analysis also documented a substantial variability of the prevalence of asthma among patients with COVID-19 and a lower risk of death in patients with asthma compared with those without.10 Furthermore, the studies reporting chronic respiratory diseases (CRD), including asthma, COPD, and bronchiectasis, in patients with COVID-19 have been limited by the small sample sizes and single disease entity.5 , 11 , 12

We hypothesized that CRD would confer an adverse impact on the clinical outcomes of COVID-19. On the basis of a nationwide database, we sought to explore the association between CRD and the clinical outcomes of COVID-19.

Study Design and Methods

Study patients

In this retrospective cohort study, data were derived from the national COVID-19 reporting system, a platform of in-patient electronic medical records (EMR) authorized by National Health Commission. Since the initial outbreak, submission of the EMR from individual hospitals designated for admitting patients with COVID-19 was requested by the National Health Commission. We extracted the data of the clinical diagnoses, comorbidities, medications, laboratory results, and clinical outcomes from the EMR. As of May 6, 2020 (the data cutoff date for our study), the database consisted of 42,218 in-patient EMR records, covering 558 designated hospitals. To be eligible for data inclusion in our analysis, all hospitalized patients had to have a diagnosis of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19. All patients had established CRD before admission. We excluded patients without any information on the comorbidities and the clinical outcomes (dead or alive, receipt of mechanical ventilation, and admission to intensive care unit). This study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Institutional Review Board: 202092). Written informed consent form was waived because of the anonymized data extraction of the EMR.

Study design and data extraction

This was a retrospective cohort study that was conducted between December 2019 and May 6, 2020. All hospitalized patients were prospectively followed up until 30 days after hospitalization. Within the EMR, each standardized in-patient discharge summary consisted of the following items: (1) demographics (ie, gender, date of birth, occupation, and geographic location); (2) the primary and secondary discharge description, coded based on the International Classification of Diseases-10; (3) the main treatment description and discharge records; (4) in-hospital outcomes (ie, death and length of hospital stay); and (5) discharge or death summary (ie, medications and discharge outcomes).

In this study, CRD consisted of asthma, COPD, and bronchiectasis. The physician diagnosis of COPD, asthma, and bronchiectasis (radiological with or without clinical bronchiectasis) at hospital admission or discharge from hospital was extracted with the computer software based on the International Classification of Disease-10 codes from the EMR. All diagnoses of CRD were made based on either the past history that was documented in the patient's clinical charts, or the clinical manifestations consistent with the global guidelines (such as the Global Initiatives for Obstructive Lung Disease and Global Initiatives for Asthma).

At the request of the National Health Commission, all medical records were stored centrally in the Tianhe-2 supercomputer, the data processing center in Guangzhou. A team of experienced computing scientists and bioinformatics data managers formulated the clinical data and electronically extracted the data with a customized operating system from the clinical charts and the portable document format files. Data were exported into a computerized database for further cross-check.

Study definitions

Chronic respiratory disease overlap denoted at least 2 coexisting CRD. At hospital admission, patients were stratified into having nonsevere (common type), or severe (respiratory rate ≥30/min, dyspnea, oxygenation index <300) or critical illness of COVID-19 (needing intensive care), based on the criteria established by The Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for COVID-19 (Trial Version 5).13 The primary endpoint, the composite outcome, was defined as needing invasive ventilation, admission to the intensive care unit, or death within 30 days after hospitalization.5 The secondary endpoint was death within 30 days after hospitalization.

Statistical analysis

In this study, we took a stepwise approach for examining the completeness of the core data sets. Specifically, we initially verified the completeness of data pertaining to the age and sex, followed by the discharge status, and the date of hospital admission. Continuous variables were presented as the medians and interquartile ranges or ranges as appropriate, and the categorical variables were displayed as the counts and percentages. Patients were categorized according to the presence or absence of any CRD. The risks of death or reaching to composite outcomes were analyzed using the Cox proportional hazards model, with the adjustment for the age, female sex, and the presence of any other systemic comorbidity. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated for the comparison of the difference in the survival risk. We have further adjusted for these potential confounding factors (including age, sex, and other systemic comorbidities) with the multivariate model to determine how they correlated with the study endpoints. No imputation was applied for missing data. Analyses were conducted with R software version 3.6.0 (packages: survival, survminer, dplyr, data.table). A P value of .05 or lower was deemed statistically significant for the regression analysis.

Results

Data inclusion

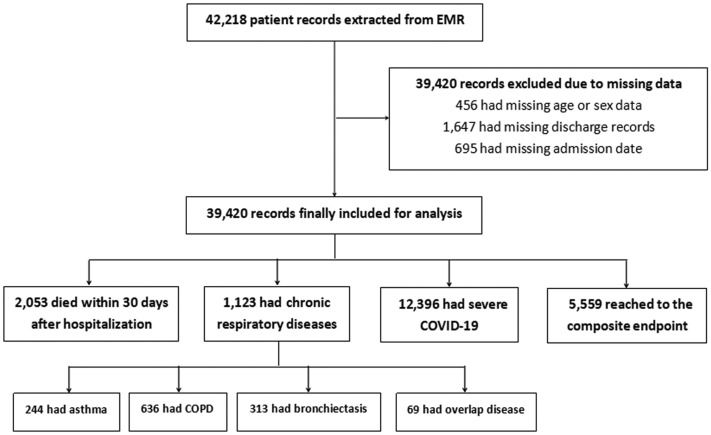

We included 39,420 laboratory-confirmed patients of 42,218 (93.4%) patients after excluding patients with missing data (age or sex [n = 456], discharge records [n = 1647], and admission date [n = 695]) (Figure 1 ). A total of 2053 (5.21%) deaths were recorded. Patients who were included in our analysis had comparable demographic characteristics compared with those who were not (Table I ).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; EMR, electronic medical records.

Table I.

Characteristics of the patients who were included in the final analysis and those excluded

| Variables | Included cases (n = 39,420) | Excluded cases (n = 2798) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (y) | 55.7 | 55.4 | .434 |

| Females, n (%) | 19,765 (50.1) | 1415 (50.6) | .659 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 2053 (5.2) | 139 (5.0) | .580 |

| Reaching the composite endpoint∗, n (%) | 5559 (14.1) | 225 (8.0) | <.001 |

Events that took place within 30 days after hospitalization.

Baseline characteristics

Any CRD and CRD overlap was present in 2.8% (n = 1123) and 0.2% (n = 69) of all patients, respectively. COPD was the most common CRD (n = 636, 56.6%), followed by bronchiectasis (n = 313, 27.9%) and asthma (n = 244, 21.7%). For CRD overlap, COPD-bronchiectasis overlap was the most common combination (n = 35, 50.7%), followed by COPD-asthma overlap (n = 25, 36.2%) and asthma-bronchiectasis overlap (n = 11, 15.9%).

The composite endpoint and systemic comorbidities

Of the 1123 patients who had at least 1 CRD, 564 (50.2%) had severe or critical illness at hospital admission and 305 (27.2%) reached the composite endpoint within 30 days after hospitalization. Of the 69 patients with CRD overlap, 37 (53.6%) had severe or critical illness at hospital admission and 16 (23.2%) reached the composite endpoint within 30 days after hospitalization. Patients with CRD accounted for 4.5% (564 of 12,396) of patients with severe or critical illness at hospital admission and 5.5% (305 of 5559) of patients reaching the composite endpoint. Patients with CRD more frequently had systemic comorbidities (except for hepatitis B) and progressed to death compared with cases without CRD (all P < .01, Table II ).

Table II.

Clinical characteristics of patients with COVID-19 on admission and clinical outcomes

| Clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes | Severe cases |

Reaching to composite endpoint |

Survived |

Died |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CRD (n = 11,832) | Having CRD (n = 564) | P value | No CRD (n = 5254) | Having CRD (n = 305) | P value | No CRD (n = 36,355) | Having CRD (n = 1012) | P value | No CRD (n = 1942) | Having CRD (n = 111) | P value | |

| Mean age (y) | 60.3 | 70.7 | <.001 | 62.6 | 71.6 | <.001 | 54.6 | 67.6 | <.001 | 70.5 | 75.6 | <.001 |

| Females, n (%) | 5587 (47.2) | 164 (29.1) | <.001 | 2378 (45.3) | 88 (28.9) | <.001 | 18,664 (51.3) | 342 (33.8) | <.001 | 729 (37.5) | 30 (27.0) | .026 |

| Respiratory symptoms, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Fever at any time | 9361 (79.1) | 427 (75.7) | .052 | 4097 (78.0) | 234 (76.7) | .607 | 24,642 (67.8) | 698 (69.0) | .424 | 1520 (78.3) | 89 (80.2) | .634 |

| Nasal congestion | 1265 (10.7) | 68 (12.1) | .306 | 621 (11.8) | 40 (13.1) | .497 | 2782 (7.7) | 86 (8.5) | .319 | 211 (10.9) | 11 (9.9) | .753 |

| Headache | 2403 (20.3) | 99 (17.6) | .111 | 924 (17.6) | 56 (18.4) | .730 | 5639 (15.5) | 158 (15.6) | .930 | 363 (18.7) | 22 (19.8) | .767 |

| Cough | 9896 (83.6) | 481 (85.3) | .301 | 4105 (78.1) | 244 (80.0) | .442 | 27,138 (74.6) | 818 (80.8) | <.001 | 1460 (75.2) | 86 (77.5) | .585 |

| Sore throat | 1223 (10.3) | 61 (10.8) | .715 | 466 (8.9) | 28 (9.2) | .853 | 3685 (10.1) | 95 (9.4) | .436 | 172 (8.9) | 10 (9.0) | .956 |

| Sputum production | 9897 (83.6) | 509 (90.2) | <.001 | 4306 (82.0) | 272 (89.2) | .001 | 25,584 (70.4) | 826 (81.6) | <.001 | 1575 (81.1) | 102 (91.9) | .004 |

| Fatigue | 6752 (57.1) | 326 (57.8) | .730 | 2681 (51.0) | 166 (54.4) | .248 | 17,482 (48.1) | 530 (52.4) | .007 | 973 (50.1) | 65 (58.6) | .083 |

| Shortness of breath | 6248 (52.8) | 384 (68.1) | <.001 | 2856 (54.4) | 205 (67.2) | <.001 | 12,600 (34.7) | 523 (51.7) | <.001 | 1291 (66.5) | 89 (80.2) | .003 |

| Other systemic comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Any | 6048 (51.1) | 409 (72.5) | <.001 | 2971 (56.5) | 238 (78.0) | <.001 | 13,127 (36.1) | 634 (62.6) | <.001 | 1343 (69.2) | 86 (77.5) | .064 |

| Diabetes | 2536 (21.4) | 140 (24.8) | .056 | 1355 (25.8) | 86 (28.2) | .351 | 4768 (13.1) | 193 (19.1) | <.001 | 566 (29.1) | 24 (21.6) | .088 |

| Hypertension | 4278 (36.2) | 278 (49.3) | <.001 | 2186 (41.6) | 169 (55.4) | <.001 | 8913 (24.5) | 419 (41.4) | <.001 | 997 (51.3) | 57 (51.4) | .998 |

| Coronary heart disease | 1159 (9.8) | 126 (22.3) | <.001 | 675 (12.8) | 80 (26.2) | <.001 | 1893 (5.2) | 165 (16.3) | <.001 | 338 (17.4) | 39 (35.1) | <.001 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 874 (7.4) | 95 (16.8) | <.001 | 549 (10.4) | 62 (20.3) | <.001 | 1318 (3.6) | 109 (10.8) | <.001 | 287 (14.8) | 26 (23.4) | .014 |

| Hepatitis B | 515 (4.4) | 19 (3.4) | .261 | 143 (2.7) | 9 (3.0) | .811 | 1407 (3.9) | 46 (4.5) | .273 | 46 (2.4) | 4 (3.6) | .412 |

| Malignancy | 543 (4.6) | 49 (8.7) | <.001 | 275 (5.2) | 25 (8.2) | .026 | 1087 (3.0) | 74 (7.3) | <.001 | 121 (6.2) | 7 (6.3) | .974 |

| Chronic renal diseases | 595 (5.0) | 124 (22.0) | <.001 | 368 (7.0) | 80 (26.2) | <.001 | 975 (2.7) | 175 (17.3) | <.001 | 204 (10.5) | 28 (25.2) | <.001 |

| Immunodeficiency | 203 (1.7) | 13 (2.3) | .296 | 85 (1.6) | 6 (2.0) | .640 | 395 (1.1) | 20 (2.0) | .008 | 45 (2.3) | 5 (4.5) | .146 |

| Complications during hospitalization, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Septic shock | 167 (1.4) | 19 (3.4) | <.001 | 160 (3.0) | 19 (6.2) | .002 | 36 (0.1) | 9 (0.9) | <.001 | 134 (6.9) | 11 (9.9) | .229 |

| Acute kidney injury | 103 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | .968 | 99 (1.9) | 4 (1.3) | .471 | 18 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) | .001 | 90 (4.6) | 2 (1.8) | .161 |

| Treatments received during hospitalization, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Intravenous antibiotics | 7484 (63.3) | 400 (70.9) | <.001 | 3433 (65.3) | 232 (76.1) | <.001 | 18,700 (51.4) | 592 (58.5) | <.001 | 1317 (67.8) | 81 (73.0) | .257 |

| Antiviral therapy | 7395 (62.5) | 341 (60.5) | .329 | 3187 (60.7) | 183 (60.0) | .819 | 21,819 (60.0) | 555 (54.8) | <.001 | 1121 (57.7) | 63 (56.8) | .841 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 1334 (11.3) | 152 (27.0) | <.001 | 834 (15.9) | 91 (29.8) | <.001 | 2049 (5.6) | 193 (19.1) | <.001 | 249 (12.8) | 19 (17.1) | .191 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 4532 (38.3) | 279 (49.5) | <.001 | 2301 (43.8) | 173 (56.7) | <.001 | 7394 (20.3) | 303 (29.9) | <.001 | 1051 (54.1) | 71 (64.0) | .043 |

| Invasive ventilation | 1400 (11.8) | 113 (20.0) | <.001 | 1400 (26.6) | 113 (37.0) | <.001 | 807 (2.2) | 70 (6.9) | <.001 | 593 (30.5) | 43 (38.7) | .069 |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 1979 (16.7) | 154 (27.3) | <.001 | 1477 (28.1) | 113 (37.0) | <.001 | 1257 (3.5) | 104 (10.3) | <.001 | 873 (45.0) | 54 (48.6) | .447 |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 149 (1.3) | 10 (1.8) | .289 | 135 (2.6) | 9 (3.0) | .684 | 116 (0.3) | 7 (0.7) | .041 | 69 (3.6) | 4 (3.6) | .978 |

| Median hospital stay (interquartile range) (d) | 17 (11, 24) | 17 (10, 27) | .004 | 14 (8, 23) | 16 (8, 28) | <.001 | 15 (10, 22) | 16 (11, 24) | <.001 | 10 (5, 16) | 10 (4, 18) | .978 |

| Intensive care unit admission∗, n (%) | 3332 (28.2) | 187 (33.2) | .010 | 3332 (63.4) | 187 (61.3) | .458 | 2732 (7.5) | 155 (15.3) | <.001 | 600 (30.9) | 32 (28.8) | .646 |

| Clinical outcomes∗, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Discharge from hospital | 10,096 (85.3) | 461 (81.7) | .019 | 3312 (63.0) | 194 (63.6) | .841 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Death | 1736 (14.7) | 103 (18.3) | .019 | 1942 (37.0) | 111 (36.4) | .841 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Bold values are statistical significance.

The denominators being lower than the total patient count suggested missing data.

Antiviral therapy consisted of lopinavir/ritonavir, remdesivir, chloroquine, hydrochloroquine, interferon-beta, arbidol, and favipinavir.

COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CRD, chronic respiratory disease.

Events that took place within 30 days after hospitalization.

Chronic respiratory diseases and the composite endpoint

Of the 12,396 patients with severe COVID-19, 564 patients had at least 1 CRD. Among the 5559 patients who reached the composite endpoint within day 30 after hospital admission, 305 patients had at least 1 CRD. Patients with CRD had an overall higher prevalence of other systemic comorbidities and more frequently required treatment for COVID-19 compared with those without CRD (Table II).

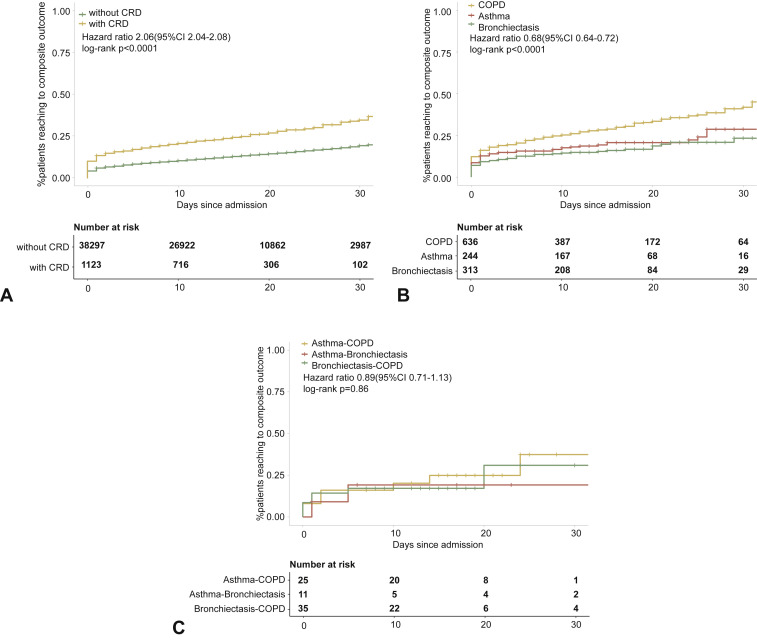

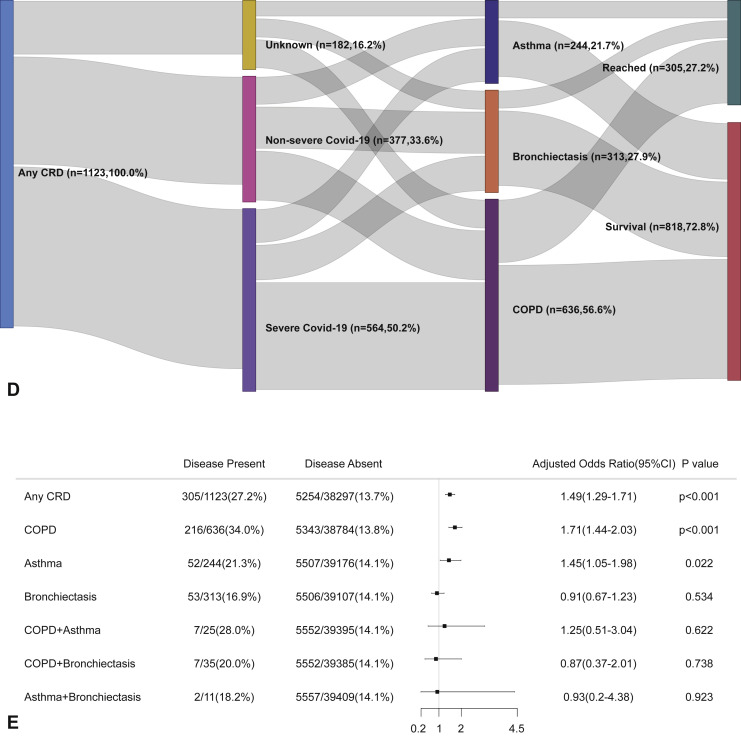

Within 30 days after hospitalization, patients with CRD had a markedly higher risk of reaching the composite endpoint compared with those without CRD (OR: 2.34, 95% CI: 2.05-2.68). Patients with COPD (OR: 3.22, 95% CI: 2.73-3.80) and asthma (OR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.22-2.26), but not bronchiectasis, had a greater likelihood of reaching the composite endpoint compared with those without in the unadjusted analysis. Patients with COPD-asthma overlap (OR: 2.37, 95% CI: 0.99-5.68), but not COPD-bronchiectasis overlap (OR: 1.52, 95% CI: 0.66-3.48) nor asthma-bronchiectasis overlap (OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 0.29-6.25), were more likely to reach the composite endpoint compared with those without CRD overlap (Figure E1, available in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

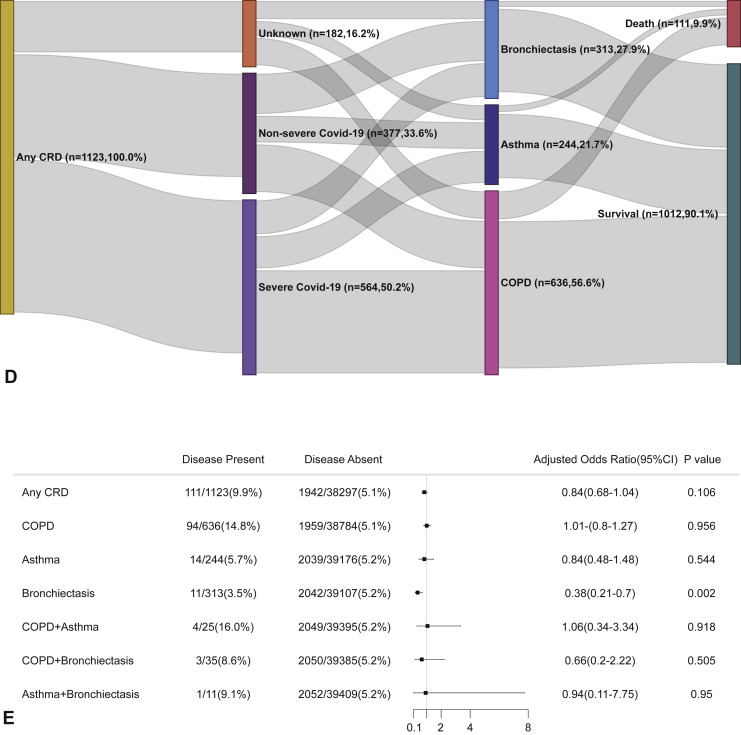

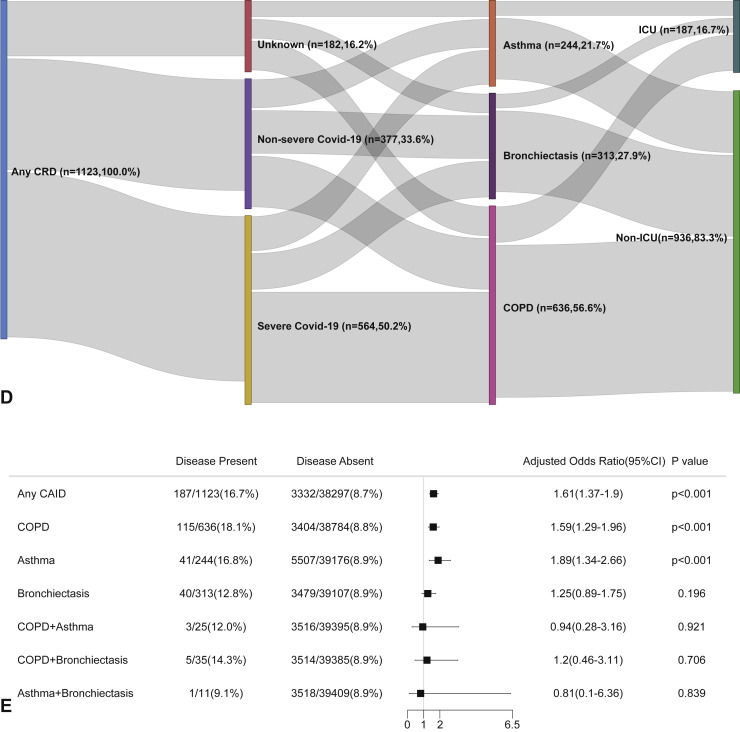

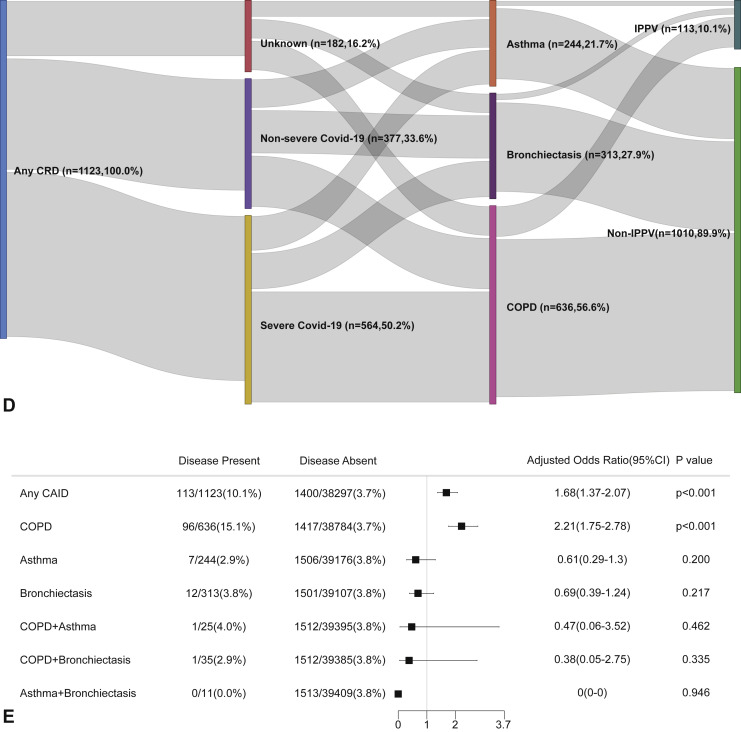

Figure E1.

CRD and the composite outcomes of COVID-19 in the unadjusted model. (A) The cumulative rate of reaching to the composite endpoints among patients with or without CRD based on the proportional hazards model. (B) The cumulative rate of reaching to the composite endpoints among patients with or without asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or bronchiectasis based on the proportional hazards model. (C) The cumulative rate of reaching to the composite endpoints among patients with asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-bronchiectasis overlap, and asthma-bronchiectasis overlap based on the proportional hazards model. (D) Association between the severity of COVID-19, CRD, and clinical outcomes. The vertical colored bars represented the patient cohort, which was further categorized into different subgroups. The association between the different subgroups was presented with the gray bars, with greater width representing a greater magnitude of overlap. (E) Risk factors predicting the composite endpoints in patients with COVID-19. Shown are the numbers and percentages of patients with each of the category of disease who had reached the composite endpoint during the study and of patients who had not reached the composite endpoint. CI, Confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRD, chronic respiratory disease; OR, odds ratio.

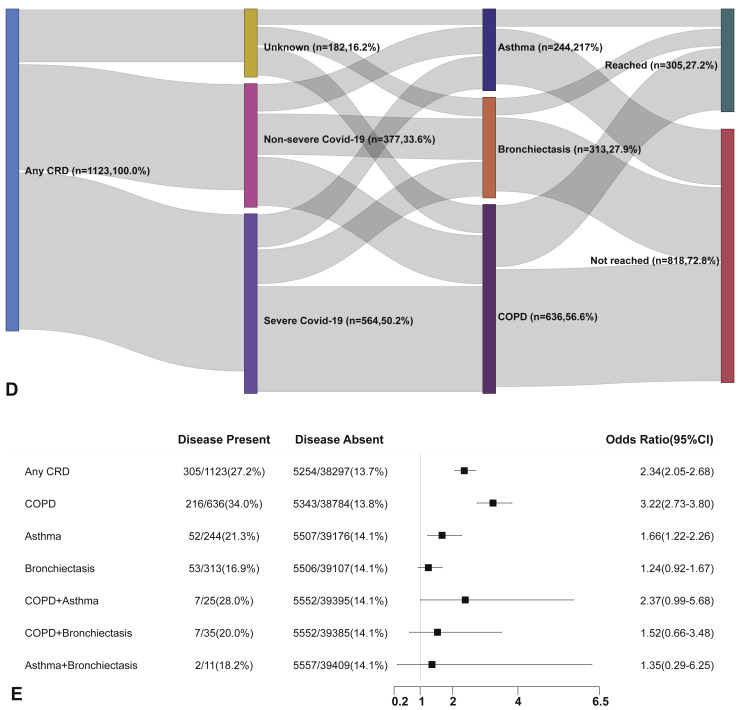

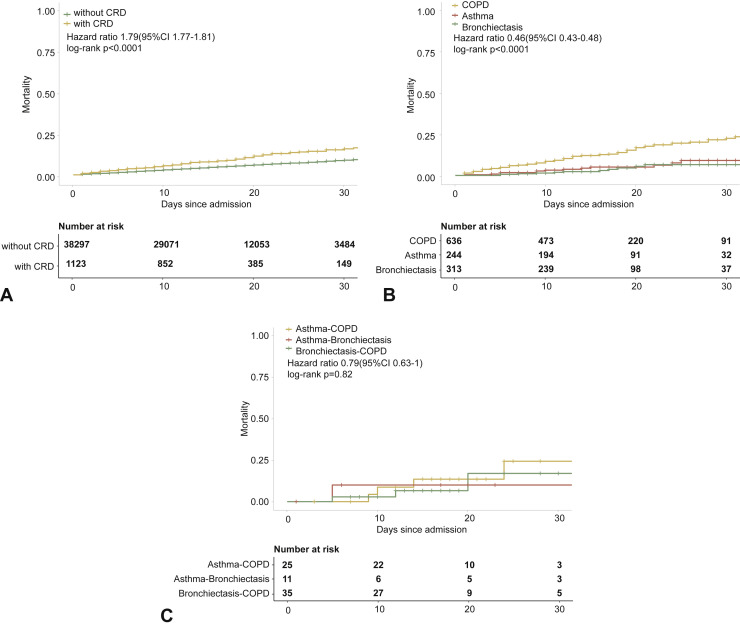

We have further adjusted the regression analysis with age, sex, and the presence of any other systemic comorbidities. Within 30 days after hospitalization, patients with CRD were associated with a significantly increased risk of reaching the composite endpoint compared with patients without CRD (OR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.29-1.71). The strength of association between the CRD and the outcomes of COVID-19 remained significant albeit being slightly tempered compared with the unadjusted analysis. Table III shows the impact of the potential confounding factors on our analysis. Age, sex, and the presence of other systemic comorbidities were associated significantly with the risk of reaching the composite endpoint in patients with any CRD, COPD, and asthma (all P < .05).

Table III.

Adjusted regression analysis of the risks of death and reaching to the composite endpoint within 30 days after hospitalization

| Composite endpoint | Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | ||||||

| Presence of chronic respiratory diseases∗ | 1.49 | 1.29, 1.71 | <.001 | 0.84 | 0.68, 1.04 | .106 |

| Any other systemic comorbidity† | 1.75 | 1.64, 1.86 | <.001 | 1.88 | 1.70, 2.08 | <.001 |

| Female sex‡ | 1.30 | 1.23, 1.38 | <.001 | 1.87 | 1.70, 2.05 | <.001 |

| Age§ | 1.03 | 1.02, 1.03 | <.001 | 1.07 | 1.07, 1.08 | <.001 |

| COPD | ||||||

| Presence of COPD∗ | 1.71 | 1.44, 2.03 | <.001 | 1.01 | 0.80, 1.27 | .956 |

| Any other systemic comorbidity† | 1.75 | 1.64, 1.86 | <.001 | 1.88 | 1.69, 2.08 | <.001 |

| Female sex‡ | 1.30 | 1.22, 1.38 | <.001 | 1.85 | 1.68, 2.04 | <.001 |

| Age§ | 1.03 | 1.02, 1.03 | <.001 | 1.07 | 1.07, 1.08 | <.001 |

| Asthma | ||||||

| Presence of asthma∗ | 1.45 | 1.05, 1.98 | .022 | 0.84 | 0.48, 1.48 | .544 |

| Any other systemic comorbidity† | 1.76 | 1.65, 1.87 | <.001 | 1.88 | 1.69, 2.08 | <.001 |

| Female sex‡ | 1.32 | 1.24, 1.40 | <.001 | 1.85 | 1.69, 2.04 | <.001 |

| Age§ | 1.03 | 1.02, 1.03 | <.001 | 1.07 | 1.07, 1.08 | <.001 |

| Bronchiectasis | ||||||

| Presence of bronchiectasis∗ | 0.91 | 0.67, 0.23 | .534 | 0.38 | 0.21, 0.70 | .002 |

| Any other systemic comorbidity† | 1.76 | 1.65, 1.87 | <.001 | 1.88 | 1.70, 2.08 | <.001 |

| Female sex‡ | 1.32 | 1.24, 1.40 | <.001 | 1.86 | 1.69, 2.04 | <.001 |

| Age§ | 1.03 | 1.02, 1.03 | <.001 | 1.07 | 1.07, 1.08 | <.001 |

CI, Confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted with the presence of any other systemic comorbidities, female sex, and age.

Adjusted with the presence of any chronic respiratory disease/COPD/asthma/bronchiectasis, female sex, and age.

Adjusted with any chronic respiratory disease/COPD/asthma/bronchiectasis, any other systemic comorbidities, and age.

Adjusted with any chronic respiratory disease/COPD/asthma/bronchiectasis, any other systemic comorbidities, and female sex.

Furthermore, patients with COPD (OR: 1.71, 95% CI: 1.44-2.03) and asthma (OR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.05-1.98), but not bronchiectasis, were more likely to reach the composite endpoint compared with those without. However, the adjusted analysis did not seem to suggest that patients with CRD overlap had a greater risk of reaching the composite endpoint compared with those without CRD overlap (Figure 2 ).

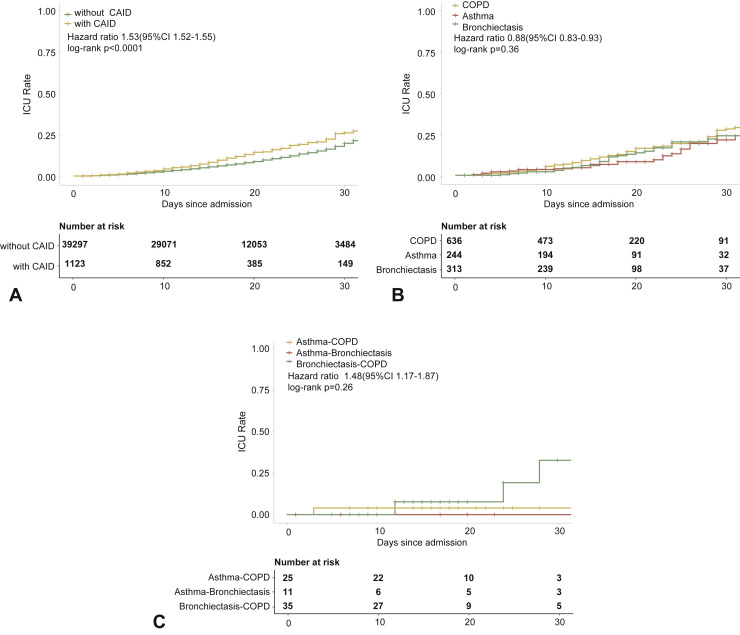

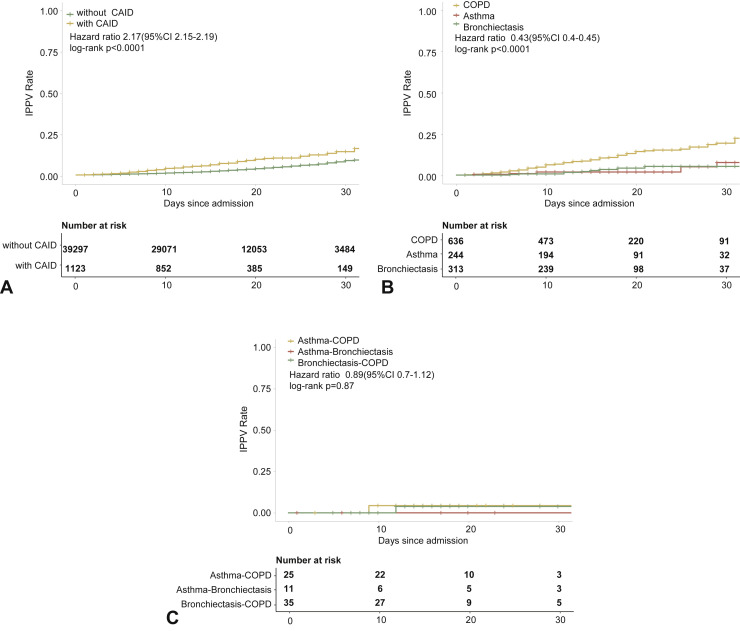

Figure 2.

CRD and the composite outcomes of COVID-19 in the adjusted model. (A) The cumulative rate of reaching to the composite endpoints among patients with or without CRD based on the Cox proportional hazards model. (B) The cumulative rate of reaching to the composite endpoints among patients with or without asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or bronchiectasis based on the Cox proportional hazards model. (C) The cumulative rate of reaching to the composite endpoints among patients with asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-bronchiectasis overlap, and asthma-bronchiectasis overlap based on the Cox proportional hazards model. (D) Association between the severity of COVID-19, CRD, and clinical outcomes. The vertical colored bars represented the patient cohort, which was further categorized into different subgroups. The association between the different subgroups was presented with the gray bars, with greater width representing a greater magnitude of overlap. E, Risk factors predicting the composite endpoints in patients with COVID-19. Shown are the numbers and percentages of patients with each of the category of disease who had reached to the composite endpoint during the study and of patients who had not reached to the composite endpoint. All models have been adjusted with female sex, age, and the presence of any other systemic comorbidities. CI, Confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRD, chronic respiratory disease; OR, odds ratio.

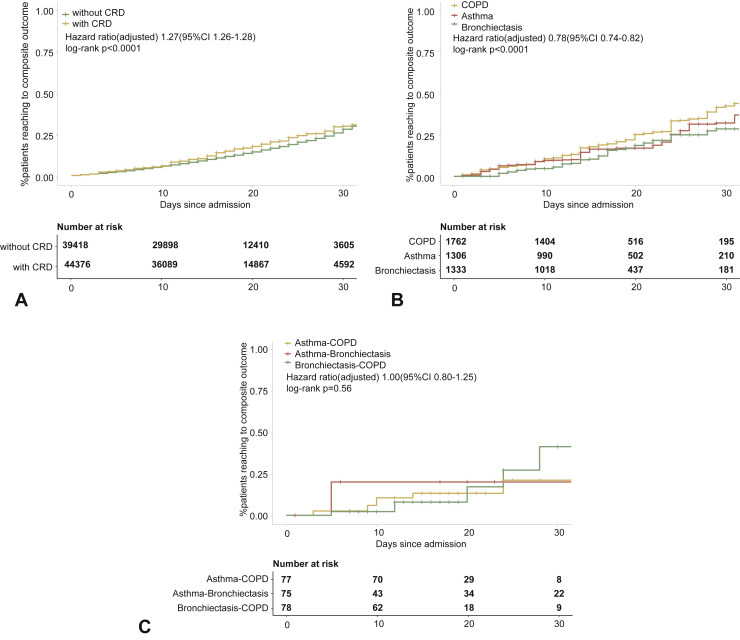

Chronic respiratory diseases and death associated with COVID-19

Within day 30 after hospital admission, 2053 patients died and 37,367 patients survived. Among the survivors at day 30, 1012 (2.7%) had at least 1 CRD. Among the survivors, patients with CRD had a significantly greater symptom burden, had higher rates of other systemic comorbidities, and required more treatments compared with those without (all P < .05). However, among the nonsurvivors, few differences in demographic characteristics, symptom burden, and treatments were identified (Table II).

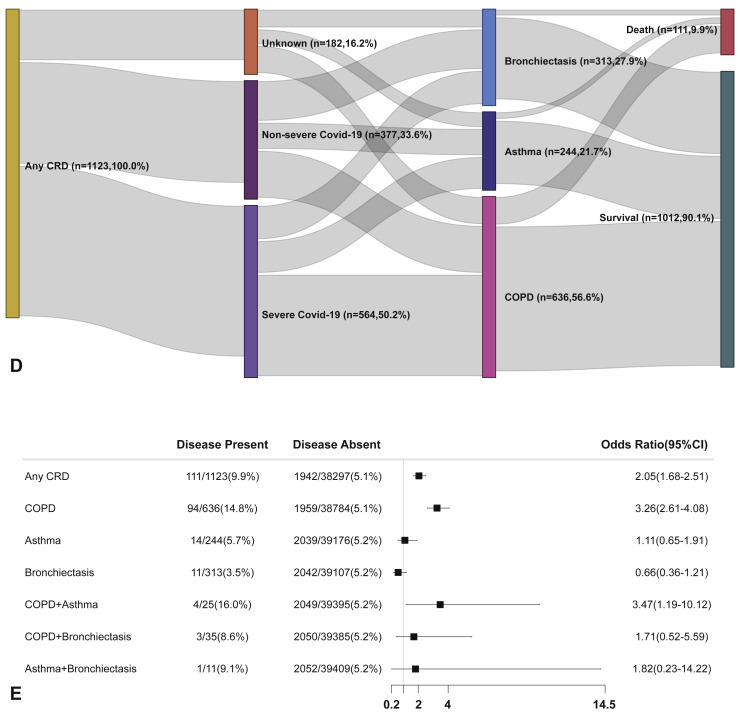

At day 30 after hospitalization, patients with CRD had an increased risk of dying from COVID-19 than those without CRD in the unadjusted analysis (OR: 2.05, 95% CI: 1.68-2.51). As shown in Table III, age, sex, and the presence of other systemic comorbidities were significantly associated with the risk of death in patients with any CRD, COPD, and asthma (all P < .05).

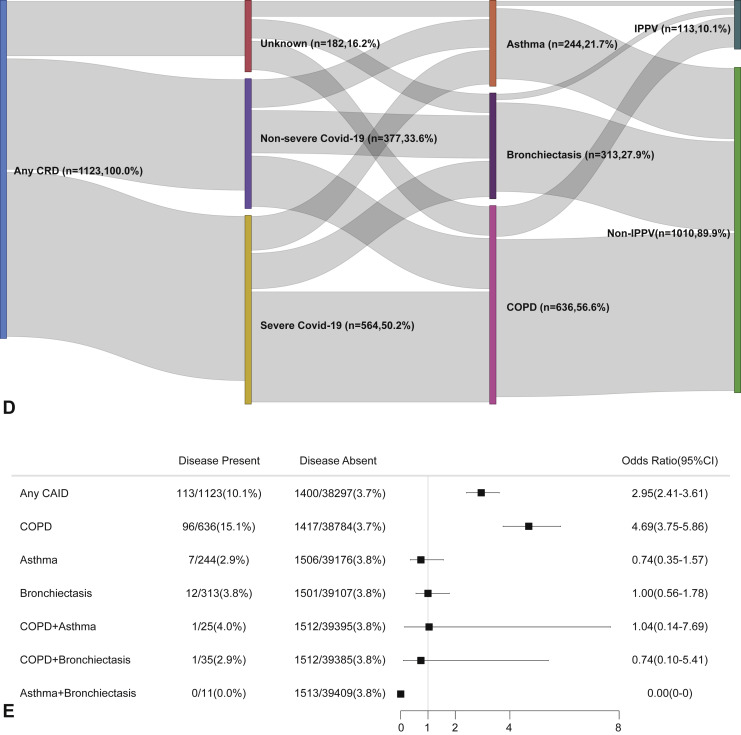

Moreover, patients with COPD (OR: 3.26, 95% CI: 2.61-4.08), but not asthma (OR: 1.11, 95% CI: 0.65-1.91) or bronchiectasis (OR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.36-1.21), had a greater unadjusted risk of dying from COVID-19 (Figure E2, available in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

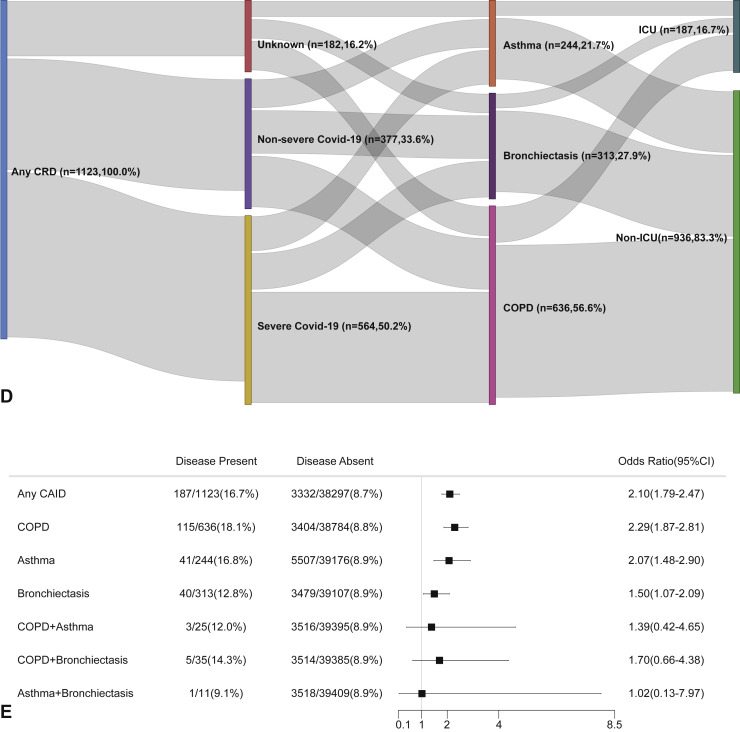

Figure E2.

CRD and the risk of death COVID-19 in the unadjusted model. (A) The cumulative rate of mortality among patients with or without CRD based on the proportional hazards model. (B) The cumulative rate of mortality among patients with or without asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or bronchiectasis based on the proportional hazards model. (C) The cumulative rate of mortality among patients with asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-bronchiectasis overlap, and asthma-bronchiectasis overlap based on the proportional hazards model. (D) Association between the severity of COVID-19, CRD, and mortality. The vertical colored bars represented the patient cohort, which was further categorized into different subgroups. The association between the different subgroups was presented with the gray bars, with greater width representing a greater magnitude of overlap. (E) Risk factors predicting mortality in patients with COVID-19. Shown are the numbers and percentages of patients with each of the category of disease who had reached the composite endpoint during the study and of patients who had not reached the composite endpoint. CI, Confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRD, chronic respiratory disease; OR, odds ratio.

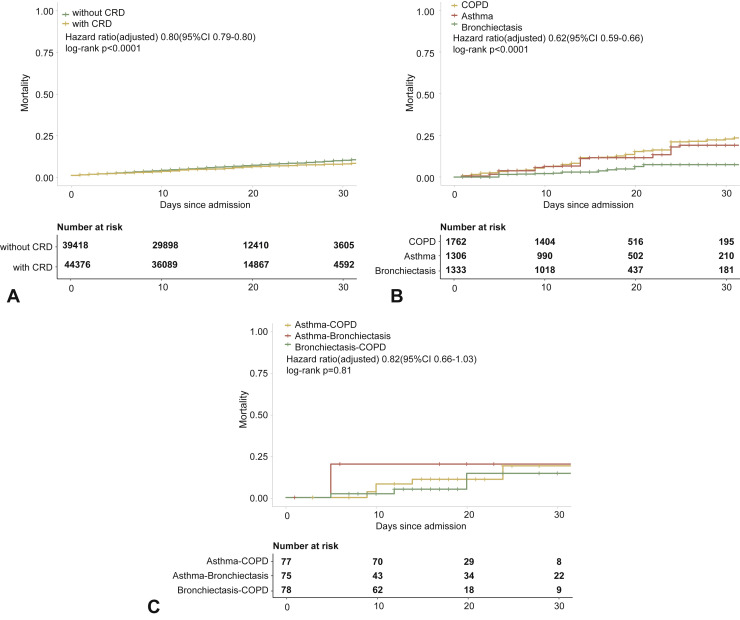

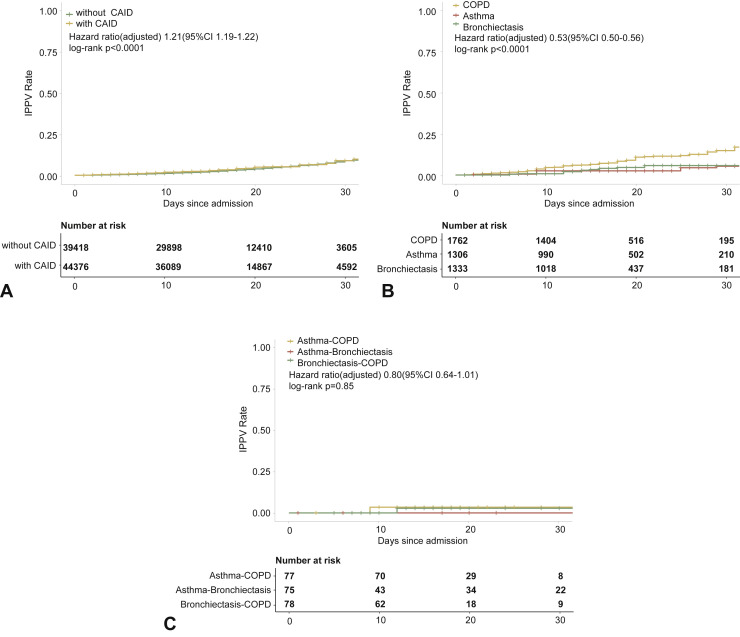

In the adjusted model, however, having CRD was not associated with a greater likelihood of dying from COVID-19 compared with those without CRD. Moreover, neither COPD nor asthma was significantly associated with the risk of death within 30 days after hospitalization. Bronchiectasis, however, seemed to confer a protective effect on the risk of death from COVID-19 in the adjusted analysis (OR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.21-0.70). Finally, CRD overlap did not confer a higher risk of mortality within 30 days after hospitalization when taking into account the age, sex, and the presence of other systemic comorbidities (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

CRD and the risk of death COVID-19 in the adjusted model. (A) The cumulative rate of mortality among patients with or without CRD based on the Cox proportional hazards model. (B) The cumulative rate of mortality among patients with or without asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or bronchiectasis based on the Cox proportional hazards model. (C) The cumulative rate of mortality among patients with asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-bronchiectasis overlap, and asthma-bronchiectasis overlap based on the Cox proportional hazards model. (D) Association between the severity of COVID-19, CRD, and mortality. The vertical colored bars represented the patient cohort, which was further categorized into different subgroups. The association between the different subgroups was presented with the gray bars, with greater width representing a greater magnitude of overlap. (E) Risk factors predicting mortality in patients with COVID-19. Shown are the numbers and percentages of patients with each of the category of disease who had reached to the composite endpoint during the study and of patients who had not reached to the composite endpoint. All models have been adjusted with female sex, age, and the presence of any other systemic comorbidities. CI, Confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRD, chronic respiratory disease; OR, odds ratio.

Chronic respiratory diseases and intensive care unit admission and invasive ventilation associated with COVID-19

Two other important metrics, the admission to the intensive care unit and the need to receive invasive mechanical ventilation within 30 days after hospitalization, have also been further evaluated. The baseline characteristics of patients when stratified by the status of intensive care unit admission and invasive mechanical ventilation are shown in Table E1, Table E2 (available in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org), respectively.

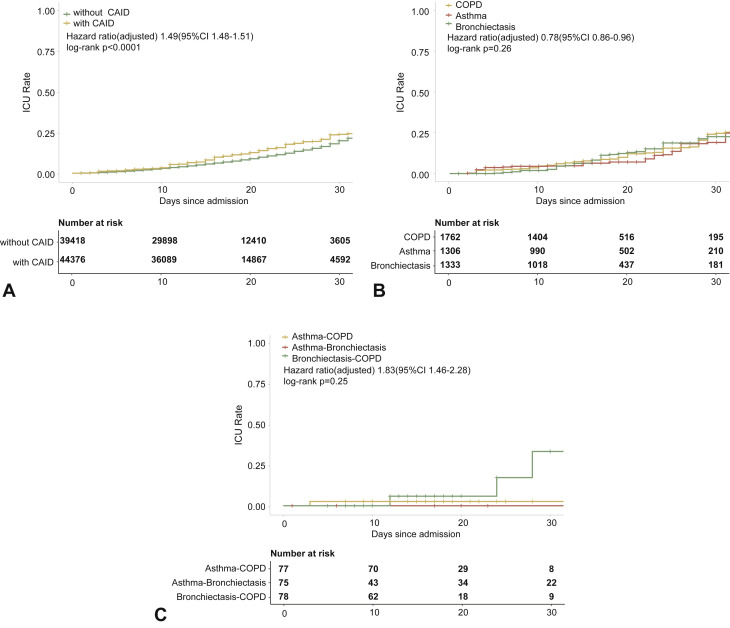

The risk of being admitted to the intensive care unit was higher in patients with CRD compared with those without CRD in both the unadjusted (Figure E3, available in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org) and adjusted analysis (Figure E4, available in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). Although in the unadjusted analysis patients with CRD had an increased risk of needing invasive mechanical ventilation compared with those without CRD (Figure E5, available in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org), this association no longer held after adjustment for age, sex, and other systemic comorbidities (Figure E6, available in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

Figure E3.

CRD and the risk of intensive care unit admission in the unadjusted model. (A) The cumulative rate of admission to the intensive care unit among patients with or without CRD based on the proportional hazards model. (B) The cumulative rate of admission to the intensive care unit among patients with or without asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or bronchiectasis based on the proportional hazards model. (C) The cumulative rate of admission to the intensive care unit among patients with asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-bronchiectasis overlap, and asthma-bronchiectasis overlap based on the proportional hazards model. (D) Association between the severity of COVID-19, CRD, and admission to the intensive care unit. The vertical colored bars represented the patient cohort, which was further categorized into different subgroups. The association between the different subgroups was presented with the gray bars, with greater width representing a greater magnitude of overlap. (E) Risk factors predicting the risk of admission to the intensive care unit in patients with COVID-19. Shown are the numbers and percentages of patients with each of the category of disease who had been admitted to the intensive care unit during the study and of patients who had not been admitted to the intensive care unit. CAID, chronic airway inflammatory diseases, which was equivalent to chronic respiratory diseases; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRD, chronic respiratory disease; OR, odds ratio.

Figure E4.

CRD and the risk of intensive care unit admission in the adjusted model. (A) The cumulative rate of admission to the intensive care unit among patients with or without CRD based on the proportional hazards model. (B) The cumulative rate of admission to the intensive care unit among patients with or without asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or bronchiectasis based on the proportional hazards model. (C) The cumulative rate of admission to the intensive care unit among patients with asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-bronchiectasis overlap, and asthma-bronchiectasis overlap based on the proportional hazards model. (D) Association between the severity of COVID-19, CRD, and admission to the intensive care unit. The vertical colored bars represented the patient cohort, which was further categorized into different subgroups. The association between the different subgroups was presented with the gray bars, with greater width representing a greater magnitude of overlap. (E) Risk factors predicting the risk of admission to the intensive care unit in patients with COVID-19. Shown are the numbers and percentages of patients with each of the category of disease who had been admitted to the intensive care unit during the study and of patients who had not been admitted to the intensive care unit. CAID, chronic airway inflammatory diseases, which was equivalent to chronic respiratory diseases; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRD, chronic respiratory disease; OR, odds ratio.

Figure E5.

CRD and the risk of needing invasive ventilation in the unadjusted model. (A) The cumulative rate of needing invasive mechanical ventilation among patients with or without CRD based on the proportional hazards model. (B) The cumulative rate of needing invasive mechanical ventilation among patients with or without asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or bronchiectasis based on the proportional hazards model. (C) The cumulative rate of needing invasive mechanical ventilation among patients with asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-bronchiectasis overlap, and asthma-bronchiectasis overlap based on the proportional hazards model. (D) Association between the severity of COVID-19, CRD, and the use of invasive mechanical ventilation. The vertical colored bars represented the patient cohort, which was further categorized into different subgroups. The association between the different subgroups was presented with the gray bars, with greater width representing a greater magnitude of overlap. (E) Risk factors predicting the risk of needing invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with COVID-19. Shown are the numbers and percentages of patients with each of the category of disease who needed invasive mechanical ventilation during the study and of patients who did not need invasive mechanical ventilation. CAID, chronic airway inflammatory diseases, which was equivalent to chronic respiratory diseases; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRD, chronic respiratory disease; OR, odds ratio.

Figure E6.

CRD and the risk of needing invasive ventilation in the adjusted model. (A) The cumulative rate of needing invasive mechanical ventilation among patients with or without CRD based on the proportional hazards model. (B) The cumulative rate of needing invasive mechanical ventilation among patients with or without asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or bronchiectasis based on the proportional hazards model. (C) The cumulative rate of needing invasive mechanical ventilation among patients with asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-bronchiectasis overlap, and asthma-bronchiectasis overlap based on the proportional hazards model. (D) Association between the severity of COVID-19, CRD, and the use of invasive mechanical ventilation. The vertical colored bars represented the patient cohort, which was further categorized into different subgroups. The association between the different subgroups was presented with the gray bars, with greater width representing a greater magnitude of overlap. (E) Risk factors predicting the risk of needing invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with COVID-19. Shown are the numbers and percentages of patients with each of the category of disease who needed invasive mechanical ventilation during the study and of patients who did not need invasive mechanical ventilation. CAID, chronic airway inflammatory diseases, which was equivalent to chronic respiratory diseases; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRD, chronic respiratory disease; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

By using the nationwide database that consisted of approximately 40,000 records, this study demonstrated a prevalence of 2.8% for any of the CRD among patients with COVID-19. The presence of any CRD correlated significantly with the risk of reaching the composite endpoint, but not death, of COVID-19 in both unadjusted and adjusted analysis. However, CRD were neither associated with the risk of reaching the composite endpoint nor death of COVID-19 after adjusting for the important confounding factors such as age, sex, and the presence of other systemic comorbidities.

Our findings pertaining to the mortality risk of COVID-19 were consistent with the observations by Lovinsky-Desir et al,14 who did not identify poorer clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 with asthma in a large cohort of patients without COPD. Moreover, García-Pachón et al15 did not identify an increased risk of being admitted to the hospital among asthmatic patients as compared with patients with COPD. By contrast, Zhu et al16 reported an elevated risk of developing severe COVID-19 among patients with asthma (mostly nonallergic) in a large cohort. COPD was associated with poorer outcomes in patients with COVID-19, which was consistent with our previous report despite the smaller sample size.5 A possible explanation for the difference in outcomes in asthma versus COPD was the difference in angiotensin-converting enzyme II expression (upregulated in COPD and downregulated in asthma).6 However, this point was not reaffirmed in another separate study that documented increased expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme II and transmembrane protease serines 2 in asthmatic patients,17 which has added complexity to the mechanisms. On the other hand, it has also been documented that inhaled corticosteroids attenuated angiotensin-converting enzyme II expression.18 Therefore, the more frequent use of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with asthma might help explain these findings. Nevertheless, the regular use of inhaled corticosteroids might have a negligible effect on the protection against COVID-19–related death among asthmatic patients and patients with COPD.19 Further mechanistic studies are warranted to decipher the link among CRD, use of inhaled corticosteroids, and the outcomes of COVID-19.

The findings related to the impact of comorbid bronchiectasis on the risk of death or reaching to the composite endpoint of COVID-19 were unexpected. No existing evidence pointing to the role of comorbid bronchiectasis on COVID-19 has been published. Although neutrophilic inflammation has been a dominant type of airway inflammatory response in both COPD and bronchiectasis, and patients with bronchiectasis might have elevated risks of developing viral-bacterial coinfection,20 bronchiectasis did not seem to confer adverse effects on the outcomes of COVID-19 in our study. We cannot conclude whether neutrophilic inflammation would predispose to a poorer outcome in patients with COVID-19 with bronchiectasis because of the lack of data pertaining to the airway inflammatory cell count in our study. It would be helpful to have lung function data that are currently lacking in our database.

Patients with CRD overlap did not seem to have poorer outcomes compared with those with individual CRD. However, the small number of patients with CRD overlap might have limited the statistical power to reach to a definitive conclusion. Hence, any conclusion on the impact of CRD overlap on the risk of reaching to the composite endpoint or death from COVID-19 might be premature. To this end, no further adjusted analysis was performed in our study and these exploratory findings should be interpreted with caution.

Age, sex, and the presence of other systemic comorbidities have also been associated with the clinical outcomes of COVID-19, which was consistent with the findings reported previously.5 , 7 , 9 Considering that these factors might have confounded our analysis, we have performed the regression analysis that mutually adjusted for these variables in our study. The models have reaffirmed the significant association of these variables with the clinical outcomes of COVID-19. Importantly, the strength of association for the risk of reaching the composite endpoint remained statistically significant after adjustment for these variables. Moreover, despite the lack of association between the risk of death and the CRD (except for bronchiectasis that might be a chance finding), each of these variables was significantly associated with the risk of death from COVID-19 in the multivariate regression model.

To our knowledge, this is the first nationwide study that explored the strength of association between CRD and their overlap and the clinical outcomes of COVID-19. A main strength of the study was the application of data analysis based on a nationwide database with a large sample size. Findings pertaining to bronchiectasis alone or in combination with asthma or COPD have not been reported previously. Our findings may have clinical implications to the triage and management of patients with COVID-19 who had underlying CRD.

However, our study has the major limitation of being a retrospective cohort study with other potential unmeasured confounding factors, despite the inclusion of age, sex, and the presence of other systemic comorbidities in the regression model. In conjunction with our earlier report1 and another study that specifically focused on the critically ill patients with COVID-19,11 the proportion of patients with CRD was relatively low compared with that in several other studies, probably due to the bias of self-report and a lack of documentation of CRD as the past history in the clinical charts, on which the extraction of medical records would depend in many regions of mainland China. In fact, an incomplete documentation of the comorbid diseases has been a notable challenge that constrains the acquisition of important medical history from the clinical charts in our real-world practice. Although we believe that the development of a nationwide electronic medical chart system would help alleviate the under-reporting of CRD, our findings were comparable with another separate study from mainland China.6 Because of the implementation of stringent nosocomial infection control measures, no lung function tests were performed provided that convalescence has not yet been achieved. The previous lung function records could not be traced because the current EMR was not linked to other existing databases. Several other important metrics reflecting the disease severity (ie, previous hospitalizations, medication prescription) also suffered from the incompleteness of documentation within the EMR. Therefore, we were unable to assess the association between the severity of CRD and the outcomes of COVID-19. The strength of association differed between the analysis on the composite endpoint and death, probably because of the limited number of death events as of data cutoff. Mechanistic investigations are needed to further decipher the association between CRD (especially COPD) and COVID-19. Furthermore, because of a high rate of incompleteness of information pertaining to the smoking status, we cannot comment whether the smoking status could have impacted on the study outcomes.

Conclusion

Our study has provided the evidence that CRD were significantly associated with the poor clinical outcomes of COVID-19 even after adjusting for the age, sex, and other systemic comorbidities. There was no additive effect of CRD overlap on the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 compared with the individual CRD, possibly because of the limited sample size for these subgroup analyses. Further exploration of the association between the severity of CRD and the outcomes of COVID-19 as well as the mechanistic underpinnings of these observations is needed.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the approval and support from the National Health Commission for the utilization of the national database of COVID-19. We are grateful to Professor Yu-tong Lu, Yue-dong Yang, and Zhi-guang Chen of the National Supercomputer Center in Guangzhou (Tianhe-2 Supercomputer) for the support on data collection and storage. We thank Drs Yan-zhen Wang, Zhi-ye Zhou, and Er-song Shang of the China Standard Medical Information Research Center for their work on the data collection and data analysis.

WJG, WHL, JXH, HBW, and NSZ contributed to concept and design. YS, LXG, and HBW acquired, analyzed, or interpreted the data. WJG, WHL, and JXH drafted the manuscript. WJG, WHL, JXH, and HBW critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. YS and LXG performed statistical analysis. JXH, HBW, and NSZ provided administrative, technical, or material support. JXH, HBW, and NSZ contributed to supervision. JXH and HBW are the guarantors of the study. They had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

This study is supported by National Health Commission (NSZ) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.: U1611261) (HBW). Guangzhou Institute for Respiratory Health Open Project (funded by China Evergrande Group) Project No. 2020GIRHHMS09 and 2020GIRHHMS19 (WJG). The sponsors had no role in the data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation and writing of the report.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Online Repository

Table E1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with COVID-19 on admission and clinical outcomes when stratified based on the status of intensive care unit admission

| Clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes | Not admitted to the ICU |

Admitted to the ICU |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No lower airway diseases (n = 34,965) | Having lower airway diseases (n = 936) | P value | No lower airway diseases (n = 3332) | Having lower airway diseases (n = 187) | P value | |

| Age (y) | 55.0 | 68.2 | <.001 | 59.5 | 69.5 | <.001 |

| Females, n (%) | 17,798 (50.9) | 313 (33.4) | <.001 | 1595 (47.9) | 59 (31.6) | <.001 |

| Respiratory symptoms, n (%) | ||||||

| Fever at any time | 23,558 (67.4) | 647 (69.1) | .260 | 2604 (78.2) | 140 (74.9) | .292 |

| Nasal congestion | 2605 (7.5) | 66 (7.1) | .646 | 388 (11.6) | 31 (16.6) | .043 |

| Headache | 5446 (15.6) | 149 (15.9) | .775 | 556 (16.7) | 31 (16.6) | .969 |

| Cough | 25,960 (74.2) | 755 (80.7) | <.001 | 2638 (79.2) | 149 (79.7) | .868 |

| Sore throat | 3608 (10.3) | 89 (9.5) | .421 | 249 (7.5) | 16 (8.6) | .585 |

| Sputum production | 24,383 (69.7) | 763 (81.5) | <.001 | 2776 (83.3) | 165 (88.2) | .077 |

| Fatigue | 16,764 (47.9) | 494 (52.8) | .004 | 1691 (50.8) | 101 (54.0) | .385 |

| Shortness of breath | 12,235 (35.0) | 497 (53.1) | <.001 | 1656 (49.7) | 115 (61.5) | .002 |

| Coexisting disorders, n (%) | ||||||

| Any | 12,718 (36.4) | 574 (61.3) | <.001 | 1752 (52.6) | 146 (78.1) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 4500 (12.9) | 158 (16.9) | <.001 | 834 (25.0) | 59 (31.6) | .046 |

| Hypertension | 8609 (24.6) | 371 (39.6) | <.001 | 1301 (39.0) | 105 (56.1) | <.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 1874 (5.4) | 159 (17.0) | <.001 | 357 (10.7) | 45 (24.1) | <.001 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 1316 (3.8) | 93 (9.9) | <.001 | 289 (8.7) | 42 (22.5) | <.001 |

| Hepatitis B | 1365 (3.9) | 43 (4.6) | .283 | 88 (2.6) | 7 (3.7) | .365 |

| Malignancy | 1076 (3.1) | 63 (6.7) | <.001 | 132 (4.0) | 18 (9.6) | <.001 |

| Chronic renal diseases | 979 (2.8) | 153 (16.3) | <.001 | 200 (6.0) | 50 (26.7) | <.001 |

| Immunodeficiency | 398 (1.1) | 25 (2.7) | <.001 | 42 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | .122 |

| Complications during hospitalization, n (%) | ||||||

| Septic shock | 80 (0.2) | 7 (0.7) | .001 | 90 (2.7) | 13 (7.0) | <.001 |

| Acute kidney injury | 52 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | .613 | 56 (1.7) | 3 (1.6) | .937 |

| Treatments received during hospitalization, n (%) | ||||||

| Intravenous antibiotics | 17,843 (51.0) | 529 (56.5) | <.001 | 2174 (65.2) | 144 (77.0) | <.001 |

| Antiviral therapy | 20,888 (59.7) | 497 (53.1) | <.001 | 2052 (61.6) | 121 (64.7) | .393 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 1608 (4.6) | 142 (15.2) | <.001 | 690 (20.7) | 70 (37.4) | <.001 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 7098 (20.3) | 277 (29.6) | <.001 | 1347 (40.4) | 97 (51.9) | .002 |

| Invasive ventilation | 839 (2.4) | 62 (6.6) | <.001 | 561 (16.8) | 51 (27.3) | <.001 |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 1366 (3.9) | 95 (10.1) | <.001 | 764 (22.9) | 63 (33.7) | <.001 |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 105 (0.3) | 7 (0.7) | .015 | 80 (2.4) | 4 (2.1) | .819 |

| Median hospital stay (interquartile range) (d) | 15 (10, 21) | 15 (9, 22) | .000 | 16 (9, 25) | 19 (11, 32) | <.001 |

| Clinical outcomes∗, n (%) | ||||||

| Discharge from hospital | 33,623 (96.2) | 857 (91.6) | <.001 | 2732 (82.0) | 155 (82.9) | .756 |

| Death | 1342 (3.8) | 79 (8.4) | <.001 | 600 (18.0) | 32 (17.1) | .756 |

COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; ICU, intensive care unit.

Outcomes that took place within 30 days after hospitalization.

Table E2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with COVID-19 on admission and clinical outcomes when stratified based on the need to receive invasive mechanical ventilation during hospitalization

| Clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes | Nonventilated cases |

Ventilated cases |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No lower airway diseases (n = 36,897) | Having lower airway diseases (n = 1010) | P value | No lower airway diseases (n = 1400) | Having lower airway diseases (n = 113) | P value | |

| Age (y) | 55.0 | 68.0 | <.001 | 64.9 | 72.4 | <.001 |

| Females, n (%) | 18,818 (51.0) | 350 (34.7) | <.001 | 575 (41.1) | 22 (19.5) | <.001 |

| Respiratory symptoms, n (%) | ||||||

| Fever at any time | 25,003 (67.8) | 696 (68.9) | .442 | 1159 (82.8) | 91 (80.5) | .543 |

| Nasal congestion | 2840 (7.7) | 79 (7.8) | .883 | 153 (10.9) | 18 (15.9) | .106 |

| Headache | 5701 (15.5) | 154 (15.2) | .860 | 301 (21.5) | 26 (23.0) | .708 |

| Cough | 27,414 (74.3) | 805 (79.7) | <.001 | 1184 (84.6) | 99 (87.6) | .387 |

| Sore throat | 3720 (10.1) | 96 (9.5) | .548 | 137 (9.8) | 9 (8.0) | .528 |

| Sputum production | 25,854 (70.1) | 818 (81.0) | <.001 | 1305 (93.2) | 110 (97.3) | .086 |

| Fatigue | 17,646 (47.8) | 530 (52.5) | .004 | 809 (57.8) | 65 (57.5) | .956 |

| Shortness of breath | 12,914 (35.0) | 522 (51.7) | <.001 | 977 (69.8) | 90 (79.6) | .027 |

| Coexisting disorders, n (%) | ||||||

| Any | 13,579 (36.8) | 635 (62.9) | <.001 | 891 (63.6) | 85 (75.2) | .013 |

| Diabetes | 4922 (13.3) | 189 (18.7) | <.001 | 412 (29.4) | 28 (24.8) | .295 |

| Hypertension | 9250 (25.1) | 416 (41.2) | <.001 | 660 (47.1) | 60 (53.1) | .223 |

| Coronary heart disease | 2012 (5.5) | 176 (17.4) | <.001 | 219 (15.6) | 28 (24.8) | .011 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 1418 (3.8) | 119 (11.8) | <.001 | 187 (13.4) | 16 (14.2) | .810 |

| Hepatitis B | 1412 (3.8) | 47 (4.7) | .178 | 41 (2.9) | 3 (2.7) | .868 |

| Malignancy | 1125 (3.0) | 72 (7.1) | <.001 | 83 (5.9) | 9 (8.0) | .384 |

| Chronic renal diseases | 1105 (3.0) | 174 (17.2) | <.001 | 74 (5.3) | 29 (25.7) | <.001 |

| Immunodeficiency | 415 (1.1) | 23 (2.3) | <.001 | 25 (1.8) | 2 (1.8) | .990 |

| Complications during hospitalization, n (%) | ||||||

| Septic shock | 71 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | .457 | 99 (7.1) | 17 (15.0) | .002 |

| Acute kidney injury | 50 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | .596 | 58 (4.1) | 3 (2.7) | .439 |

| Treatments received during hospitalization, n (%) | ||||||

| Intravenous antibiotics | 18,861 (51.1) | 566 (56.0) | .002 | 1156 (82.6) | 107 (94.7) | <.001 |

| Antiviral therapy | 21,839 (59.2) | 528 (52.3) | <.001 | 1101 (78.6) | 90 (79.6) | .802 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 1942 (5.3) | 167 (16.5) | <.001 | 356 (25.4) | 45 (39.8) | <.001 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 7495 (20.3) | 284 (28.1) | <.001 | 950 (67.9) | 90 (79.6) | .009 |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 1441 (3.9) | 85 (8.4) | <.001 | 689 (49.2) | 73 (64.6) | .002 |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 73 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | .999 | 112 (8.0) | 9 (8.0) | .989 |

| Median hospital stay (interquartile range) (d) | 15 (10, 21) | 16 (10, 23) | <.001 | 17 (10, 25) | 16 (9, 31) | .989 |

| Intensive care unit admission, n (%) | 2771 (7.5) | 136 (13.5) | <.001 | 561 (40.1) | 51 (45.1) | .292 |

| Clinical outcomes∗, n (%) | ||||||

| Discharge from hospital | 35,548 (96.3) | 942 (93.3) | .000 | 807 (57.6) | 70 (61.9) | .373 |

| Death | 1349 (3.7) | 68 (6.7) | <.001 | 593 (42.4) | 43 (38.1) | .373 |

COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019.

Outcomes that took place within 30 days after hospitalization.

References

- 1.World Health Organizaion Weekly operational update on COVID-19—13 November 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-operational-update-on-covid-19---13-november-2020 Available from:

- 2.Gandhi R.T., Lynch J.B., Del Rio C. Mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1757–1766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2009249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berlin D.A., Gulick R.M., Martinez F.J. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451–2460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2009575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang W., Yao J., Chen A., Lv Q., Zanin M., Liu J. Early triage of critically ill COVID-19 patients using deep learning. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3543. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan W.J., Liang W.H., Zhao Y., Liang H.R., Chen Z.S., Li Y.M. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:200054. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song J., Zeng M., Wang H., Qin C., Hou H.Y., Sun Z.Y. Distinct effects of asthma and COPD comorbidity on disease expression and outcome in patients with COVID-19. Allergy. 2021;76:483–496. doi: 10.1111/all.14517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen D.M., Strange J.E., Gislason G., Torp-Pedersen C., Gerds T., Fosbøl E. Charlson Comorbidity Index score and risk of severe outcome and death in Danish COVID-19 patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:2801–2803. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05991-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang B., Li R., Lu Z., Huang Y. Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with COVID-19: evidence from meta-analysis. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:6049–6057. doi: 10.18632/aging.103000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark A., Jit M., Warren-Gash C., Guthrie B., Wang H.H.X., MercerSW Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1003–e1017. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30264-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu S., Cao Y., Du T., Zhi Y. Prevalence of comorbid asthma and related outcomes in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avdeev S., Moiseev S., Brovko M., Yavorovskiy A., Umbetova K., Akulkina L. Low prevalence of bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive lung disease among intensive care unit patients with COVID-19. Allergy. 2020;75:2703–2704. doi: 10.1111/all.14420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L., Foer D., Bates D.W., Boyce J.A., Zhou L. Risk factors for hospitalization, intensive care and mortality among patients with asthma and COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:808–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Health Commission The diagnosis and treatment protocol for COVID-19 (Trial Version 5) http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202002/d4b895337e19445f8d728fcaf1e3e13a.shtml Available from:

- 14.Lovinsky-Desir S., Deshpande D.R., De A., Murray L., Stingone J.A., Chan A. Asthma among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and related outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:1027–1034.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-Pachón E., Zamora-Molina L., Soler-Sempere M.J., Baeza-Martínez C., Grau-Delgado J., Padilla-Navas I. Asthma and COPD in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:604–606. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu Z., Hasegawa K., Ma B., Fujiogi M., Camargo C.A., Jr., Liang L. Association of asthma and its genetic predisposition with the risk of severe COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:327–329.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radzikowska U., Ding M., Tan G., Zhakparov D., Peng Y., Wawrzyiak P. Distribution of ACE2, CD147, CD26, and other SARS-CoV-2 associated molecules in tissues and immune cells in health and in asthma, COPD, obesity, hypertension, and COVID-19 risk factors. Allergy. 2020;75:2829–2845. doi: 10.1111/all.14429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finney L.J., Glanville N., Farne H., Aniscenko J., Fenwick P., Kemp S.V. Inhaled corticosteroids downregulate the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in COPD through suppression of type I interferon. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:510–519.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schultze A., Walker A.J., MacKenna B., Morton C.E., Bhaskaran K., Brown J.P. Risk of COVID-19-related death among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma prescribed inhaled corticosteroids: an observational cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1106–1120. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30415-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen C.L., Huang Y., Yuan J.J., Li H.M., Han X.R., Martinez-Garcia M.A. The roles of bacteria and viruses in bronchiectasis exacerbation: a prospective study. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.arbr.2019.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]