Abstract

Metabolites produced in the human gut are known modulators of host immunity. However, large-scale identification of metabolite–host receptor interactions remains a daunting challenge. Here, we employed computational approaches to identify 983 potential metabolite–target interactions using the Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) cohort dataset of the Human Microbiome Project 2 (HMP2). Using a consensus of multiple machine learning methods, we ranked metabolites based on importance to IBD, followed by virtual ligand-based screening to identify possible human targets and adding evidence from compound assay, differential gene expression, pathway enrichment, and genome-wide association studies. We confirmed known metabolite–target pairs such as nicotinic acid–GPR109a or linoleoyl ethanolamide–GPR119 and inferred interactions of interest including oleanolic acid–GABRG2 and alpha-CEHC–THRB. Eleven metabolites were tested for bioactivity in vitro using human primary cell-types. By expanding the universe of possible microbial metabolite–host protein interactions, we provide multiple drug targets for potential immune-therapies.

Subject terms: Drug development, Cellular signalling networks

Using computational approaches, Nuzzo et al. identify 983 potential metabolite–human target interactions from the Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) cohort dataset of the Human Microbiome Project 2 (HMP2) and public databases. These predicted interactions can further the understanding of host–microbiome interactions and assist in drug discovery for IBD and other diseases.

Introduction

Endogenous metabolites produced in the gastro-intestinal tract (GIT) by microbial and human metabolic processes have a significant role in modulating host immune responses1. Therefore, targeting the interspecies cross-talk between microbial metabolites and human host receptors holds a recognized therapeutic potential2. Disentangling these interactions in order to retrieve meaningful information remains highly challenging3. Observational studies of microbial metabolite abundances in human disease-related cohorts can suggest general associations with disease etiology but lack the granularity to identify specific metabolite–host receptor pairings4 or causal relationships5. Conversely, mechanistic studies that have either focused on a few selected metabolites screened against specific receptors6, or adopted system biology modeling7 are limited by our current knowledge of metabolic pathways and are difficult to scale to identify hundreds or thousands of interactions with druggable potential.

Growing in vitro receptor–ligand assay databases have greatly increased the hypothesis space for drug discovery8 while giving meaningful mechanistic information regarding metabolite–protein interactions. Here we present the results of a large-scale computational analyses, using bioinformatic and chemoinformatic approaches, to identify multiple and specific interactions between endogenous metabolites and human host proteins. We utilized a multi-omics dataset from an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) cohort9 published by the Human Microbiome Project 2 consortium (HMP2)10. IBD includes Ulcerative Colitis (UC) and Crohn’s Disease (CD), whose etiology heavily depends on the interplay between the GIT microbiome and immune system11. We then used virtual ligand-based screening to predict the activity of the original query metabolites on multiple targets12 based upon historical assay databases containing interaction data between similar molecules and specific targets. We believe that these predicted interactions will further our understanding of host–microbiome interactions as well as assist in drug discovery for IBD and other diseases.

Results

Ranking metabolites for relative importance in disease states

The HMP2 consortium IBD cohort sub-study9 involved intensive multi-omics characterization of patients with CD or UC and non-IBD control subjects. We focused on the metabolomics data collected from stool over the course of one year (specifically, the pre-processed metabolomics abundance tables) and bulk transcriptomics data obtained from biopsies of different sections of the gut at the beginning of the study (specifically, the pre-processed transcriptomic count tables) (see Methods). Patients with less than 3 samples per datatype or with only one sampling point were excluded, to the final sample size described in Table 1. Each sample included data on 548 metabolites (matched against the Human Metabolome Database [HMDB]), and 43870 transcripts (aligned to Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 [GRCh37]).

Table 1.

Overview of the samples and patient dataset used in this study (after filtering from the original study by Lloyd-price et al9.).

| Participants by sampling | Total samples over time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Metabolomics | Host transcriptomics | Metabolomics | Host transcriptomics |

| CD | 43 | 50 | 127 | 265 |

| UC | 25 | 30 | 74 | 146 |

| nonIBD | 22 | 26 | 51 | 135 |

| Total | 90 | 106 | 252 | 546 |

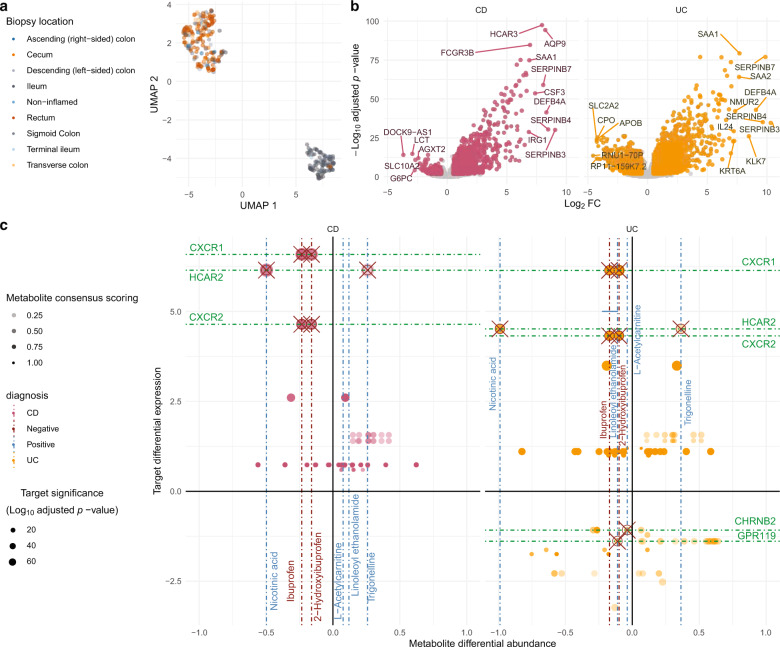

Metabolomic samples did not cluster effectively by disease state in embedded projections (Fig. 1a). To better define metabolite relevance for CD or UC etiology we utilized an ensemble method that combined results from multiple analytical methods (specifically, power estimation and both feature importance and SHAP values, each from two selected machine learning methods) combined into a single consensus score, normalized between 0 and 1, where 1 represents the most significant metabolite across all methods (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2; Supplementary Data 1). Using power estimation alone, approximately 73% of the 548 metabolites were differentially abundant (log-fold change with q value ≤ 0.05) between non-IBD controls and either CD or UC patients (Fig. 1b). Metabolites in the top quartile of the consensus scoring, 29% of which overlapped with significantly differentially abundant metabolites detected in the original HMP2-IBD study9, were considered for downstream analysis (n = 192) (Fig. 1c). We also annotated the selected 192 metabolites from HMDB, but no statistical difference was found in the consensus scoring across metabolite ontology (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 1. Metabolomics results and comparisons to the original HMP2 IBD study9 (HMP2).

a UMAP analysis of the metabolomics sample distribution by Crohn’s disease (CD) and Ulcerative Colitis (UC) patients and controls (nonIBD). b Volcano plot showing the differential abundance of each metabolite per disease state against the consensus scoring of each state. c Number of metabolites considered relevant in HMP2 and current study per disease state, subdivided into overlapping and non-overlapping subsets. d Total number of metabolites selected relevant in each study. e Intersection matrix between metabolites selected each study. f Correlation plot between the bootstrapped power estimation method used to determine metabolite differential abundance between CD and UC patients results. g Correlation between the consensus scoring used in this study and HMP2 FDR-adjusted p values for each metabolite (refer to Table 1 for samples composition).

In agreement with previous studies, CD and UC patients had a significant (i.e., q value < 0.05) depletion of short chain fatty acids like butyrate (log10fc = −0.15[CD]; −0.06[UC]) and valerate/isovalerate (log10fc = −0.29[CD]; −0.48[UC]). Significant enrichments included several acylcarnitines, arachidonate (log10fc = 0.59[CD]; 0.60[UC]), taurocholate (log10fc = 0.16[CD]; 0.04[UC]), with a correspondent depletion of lithocolate (log10fc = −0.30[CD]; −0.58[UC]) and deoxycholate (log10fc = −0.53[CD]; −0.53[UC]). Among the highest-ranking metabolites in CD and UC, we also detected a substantial and significant enrichment in nicotinuric acid, (log10fc = 0.43[CD]; 1.16[UC]), C18:1 carnitine (log10fc = 0.54[CD]; 0.30[UC]) and several triacylglycerols, while porphobilinogen (log10fc = −0.26[CD]; −0.70[UC]), tetradecanedioic acid (log10fc = −0.76[CD]; −0.86[UC]) and nicotinic acid (log10fc = −0.49[CD]; −0.99[UC]) were notably depleted.

Connecting metabolites as ligands to specific human proteins

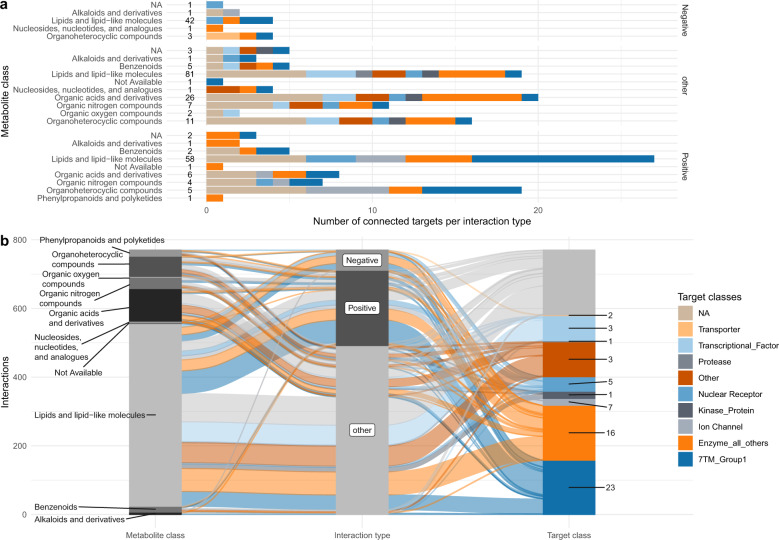

To connect metabolites with perspective receptors, we used their chemical structure as query to find structurally similar natural or synthetic compounds with functional assay data in the ChEMBL database. The original metabolites were mapped to ChEMBL compounds by similarity searches using canonical chemical fingerprints which reduced the total space of metabolites and perspective targets to 13,082 unique pairs. We further filtered for compounds having high similarity scores with the top-ranking metabolites (i.e., Tanimoto similarity ≥ 0.85 or Tverskyα=0.05 similarity ≥ 0.95) and, for those, only binding proteins with perspective high affinity (i.e., either pIC50 or pEC50 values, hereafter referred to as pxC50 ≥ 5.5) were retained. Highly pleiotropic metabolites (i.e., metabolites with ≥ predicted 20 targets), or pleiotropic targets (i.e., targets with predicted associations to ≥ 20 metabolites) were removed to further refine the hypothesis space.

A total of 135 metabolites were provisionally connected to 80 different perspective targets (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Data 2). Those metabolites fell mostly into the lipid-like and organic acid macro-categories with expected modulatory activity against 9 macro-categories of drug targets (Fig. 2b). For example, 7-methylguanine, is structurally similar (Tverskyα=0.05 similarity = 0.96) to 8-aminoguanine (CHEMBL8040) which is an inhibitor (pxC50 = 5.8–6.2) of purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP). Among the lipid-like metabolites, heptanoic acid was connected through azelaic acid (CHEMBL1238, Tverskyα=0.05 similarity = 0.955) to the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha (PPARA) with high inhibitory activity (pxC50 = 6.0 and 8.6). Hydrocinnamic acid, depleted in both UC and CD patients was connected to cytochrome P450 p1a2 (CYP1A2) (Tanimoto similarity = 0.89) via a strong analog inhibitor (pxC50 = 8.3). Nicotinic acid (underrepresented in CD and UC patients) was connected to its known receptor, the hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (HCAR2 or GPR109a), whereas the product of its degradation, nicotinuric acid, was overrepresented and connected to Lamin A/C protein (LMNA) through a binder analog (Tverskyα=0.05 similarity = 0.97, pxC50=7.65) with unknown directionality. Alpha-carboxyethyl hydroxychroman (alpha-CEHC) was also connected to LMNA but also to the thyroid hormone receptor beta (THRB). However, since the modulatory action of the analog compound is unknown and alpha-CEHC is depleted in UC but enriched in CD, we were unable to infer directionality of the interaction. Oleanolic acid was connected through other plant terpenoids (urolic and moronic acid) and bacterial-specific sphingolipids (i.e., CHEMBL1334750) to several targets of interest for pharmaceutical purposes such as GPBAR1 (G Protein-Coupled Bile Acid Receptor 1) and PTPN7 (Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 7).

Fig. 2. Overview of the connected metabolites with highest ranking scores and the perspective targets.

a Distribution of target drug classes per each metabolite class (numbers represent unique metabolites per metabolite class). b Alluvial plot describing the distribution of connections between metabolite classes, modulation type and drug target classes (numbers represent unique targets per drug target class).

Connecting gene expression and metabolite abundance

We then considered differential expressed genes (DEGs) comparing non-IBD against CD and UC states respectively, accounting for the heavy impact of the biopsy location variable (Fig. 3a). A total of 2170 DEGs occurred overall, of which 820 DEGs were shared by both CD and UC (Fig. 3b). Pathway enrichment analysis determined a high representation of immune inflammation-related pathways (i.e., Cytokine Signaling, NRF2 non−canonical NF − kB pathway, Interleukin 3, 14 and 17 signaling) (Supplementary Fig. 4; Supplementary Data 3).

Fig. 3. Overview of the transcriptomics analysis results.

a UMAP analysis of the transcriptomic samples by biopsy location. b Volcano plots representing target differential expressions in Crohn’s disease (CD) and Ulcerative Colitis (UC) states by FDR-adjusted p value. c Cross-plot showing possible interactions of interest between targets with expression on the vertical axis and perspective modulator metabolite differential abundances on the horizontal axis, per each disease type (refer to Table 1 for samples composition).

Starting from DEGs, we proceeded to parse connections with differentially abundant metabolites using the ChEMBL database, by inverting the workflow described above. After parsing all possible modulators among for DEGs, top-ranking metabolites were considered modulators if having any similar analog with functional activity against the candidate gene represented by the transcript, resulting in a total of 45 prospectively druggable targets.

Several metabolites underrepresented in IBD were classified as tentative negative modulators of upregulated targets. For example, receptors of the CXC ligand 8 (CXCL8 or IL8) chemokine family, CXCR1 and CXCR2, were overexpressed while their known negative modulator compounds, ibuprofen (pxC50 = 7.0) and its HMP-2 derivative, 2-hydroxibuprofen, (Supplementary Data 3), were under-represented in IBD patients although below the consensus scoring threshold (Supplementary Data 1).

Another example is HCAR2 (GPR109a) which was upregulated in CD and UC patient biopsies (log2fc = 6.15 [CD] and 4.51 [UC]) while its competing modulators, nicotinic acid and trigonelline were depleted and enriched, respectively, in IBD patients’ stool (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Data 2).

We also built connections based on co-directionality between metabolite depletion and corresponding downregulation of perspective targets. For example, GPR119 was downregulated in the UC cohort (log2fc = −1.39) and its known activator, linoleoyl ethanolamide (pxC50 = 5.66) was significantly depleted in UC patients (Supplementary Data 1). Neuronal acetylcholine receptor subunit beta-2 (CHRNB2) was downregulated in UC patients (log2fc = −1.08) where L-acetylcarnitine and cotinine were depleted, both analog to acetylcholine (Tverskyα=0.05 similarity =0.95 and 0.99), a strong inhibitor of CHRNB2 (pxC50 = 8.8). Nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2), upregulated in IBD patients (log2fc = 2.60[CD]; 3.49[UC]), was connected to the depletion of negative modulators such as L-arginine (pxC50 = 6.52, log10fc = −0.31[CD]; −0.19[UC]).

Assigning candidate metabolites to targets with genetic evidence

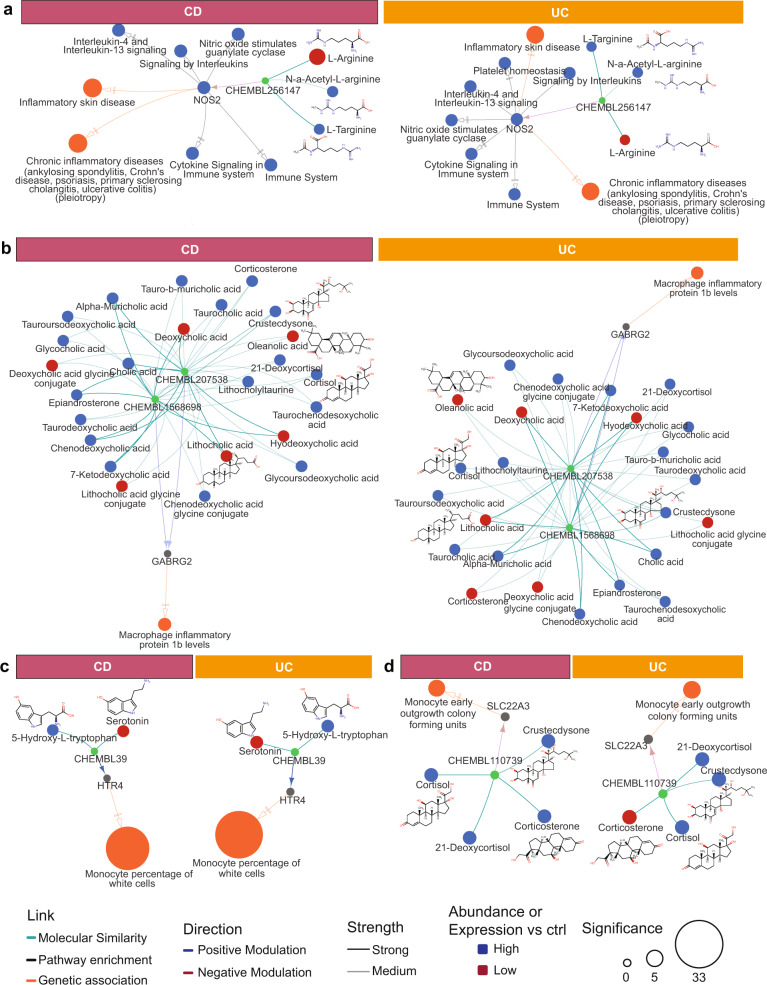

We retrieved 808 genes with genetic association to IBD from the GWAS catalog13 and an extensive published review of IBD pathways14. These genes were intersected with target-compound assay and HMP2 datasets which resulted in 464 potential unique pairings of candidate genetic targets with metabolite modulators (Supplementary Data 4), 13 of which have metabolites with known modulation mechanisms (Fig. 4a–d; Supplementary Data 5).

Fig. 4. Overview of identified for putative target proteins.

Metabolites were connected through similar ChEMBL compounds where similarity is classified as medium (0.8 < Tanimoto score < 0.9) or strong (Tanimoto score > 0.9) for (a) CXCR1/2 and NOS2, (b) HTR4, (c) GABRG2 and (d) SLC22A3. Direction and affinity of analog binding to target was parsed from ChEMBL assay databases and represented as medium (5.5 < pxC50 < 7.0) and strong (pxC50 > 7.0). Direction (i.e., up- or down-) of differential expression for targets or differential abundance for metabolites are represented by colors. Target significance (log q value) is based on differential expression of the gene or GWAS association. Complete results for targets with genetic evidence are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

CXCR1 and CXCR2 were mapped to a regulatory variant (rs11676348-T) statistically associated with an increase risk to UC15 (Supplementary Fig. 5), and in our study were mapped to an inhibitor, ibuprofen. An intronic variant statistically associated to inflammatory skin disease (rs4795067)16 is mapped to NOS2, which is also part of enriched nitric oxide and microbe-sensing pathways, both involved in IBD phenotypes (Fig. 4a); we connected NOS2 with the scarcity of arginine, an inhibitor. Other metabolite–target pairings, although not differentially expressed in the HMP2 dataset, had interesting genetic and metabolomics associations. For instance, an intergenic variant (rs79243092-C) mapped to gamma-aminobutyrate receptor subunit 2 (GABRG2) is linked to an increase in macrophage inflammatory protein 1b in Europeans17. In our study we linked GABRG2 to several conjugated bile acids and corticosteroids depleted in IBD, including oleanolic acid, through ganaxolone (CHEMBL1568698) and allopregnanolone (CHEMBL207538), two activator compounds (Fig. 4b). Finally, variant rs56330463-C mapped to the serotonin receptor (HTR4) is associated with increase in monocytes, an inflammatory phenotype18. Notably, serotonin was depleted in UC an CD patients while its precursor, H-hydroxy-L-tryptophan (5-HTP) was enriched (Fig. 4c). Finally, intronic variant rs402219-G, inside the solute carrier family 22 member 3 gene (SLC22A3) is genetically associated to another monocyte-related inflammatory marker;19,20 SLC22A3 is antagonized by corticosterone (CHEBL110739) and several corticosterone-similar metabolites were enriched in disease states (Fig. 4d). In summary, our collective analyses identified thousands of unique of metabolite–targets pairs, 983 of which having known direction of modulation (Supplementary Data 6, unfiltered results in Supplementary Data 7).

Biological effects of specific metabolites from complex in vitro cellular assays

To evaluate the biological activity of predicted receptor–metabolites pairings, we profiled eleven candidate metabolites across a standardized panel of disease-relevant human primary cell-based phenotypic cellular assays, the BioMAP® Diversity PLUS panel21. The profiled metabolites were 13-cis-retinoic acid, acetylcholine, adenosine, alpha-CEHC, butyrate, histamine, ibuprofen, lithocholic acid, nicotinic acid, oleanolic acid and serotonin (assay results and plots are shown in Supplementary Data 8 and Supplementary Fig. 6, respectively). Different concentrations were tested for each metabolite due to cytotoxicity constraints, but keeping highest concentrations above reported average concentrations measured in human blood (as from the HMDB). None of the compounds showed cytotoxicity effects. However, quantitative differences in the responses of specific cellular systems could be related to the metabolite concentrations which were determined by compound solubility and avoidance of cytotoxicity.

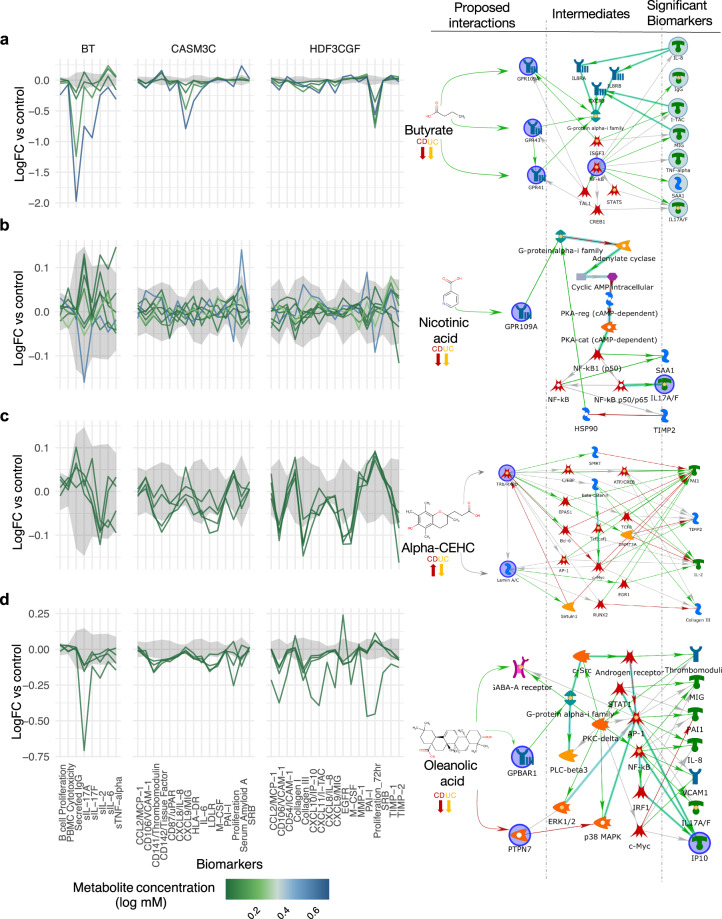

In Fig. 5, we show examples of four metabolites where knowledge-based canonical pathway analyses were used to identify explanatory links between the perspective modulated targets for each metabolite and their respective in vitro assay readouts. Butyrate is a known immunomodulator of GPR41, GPR43 and HCAR2 so we performed in vitro assays for benchmarking purposes. Butyrate showed anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory related activity (i.e., decreased levels of IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-alpha) across multiple cellular assays representing T cell dependent B cell activation (BT), fibroblasts (HDF3CGF) and coronary artery smooth muscle cells (CASM3C) (Fig. 5a), but also had antiproliferative effects on lymphocytes in the BT system.

Fig. 5. Examples of biomarker readouts from in vitro cell assays for four of eleven tested metabolites.

a Butyrate, b Nicotinic acid, c Alpha-CEHC and d Oleanolic acid. Metabolites were administered at different concentrations, here ranked from higher to lower (concentrations in Supplementary Data 8). Readouts graph show the differential abundance vs baseline for the B and T cell system (BT), arterial smooth muscle cells (CASM3C) and wound healing (HDF3CGF) (full results for all 11 metabolites are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6). Knowledge-based graphs on the right represent possible pathway connections between the proposed targets for each metabolite and the most significant biomarker readouts. Interactions are color-coded for positive (green), negative (red) and unknown (gray) modulation.

Nicotinic acid (vitamin B3) is an anti-inflammatory activator of HCAR2. Nicotinic acid was largely inactive at tested concentrations with minor lowering of soluble IL-17A in the BT system (Fig. 5b). Alpha-CEHC was a highly scoring metabolite in our analysis with unclear directionality to disease mechanisms. Alpha-CEHC also had low activity with slight suppression of several inflammatory markers in the HDF3CGF system of dermal fibroblast cells modeling wound healing and fibrosis (Fig. 5c). Finally, we show oleanolic acid which has known anti-inflammatory properties and, based on our analysis, potentially interacts with GABRG2 as its target. Oleanolic acid showed strong anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activity across multiple systems including the above-mentioned BT, CASM3C and HDF3CGF systems as well as KF3CT which models Th1 cutaneous inflammation. Interestingly, oleanolic acid was not antiproliferative to lymphocytes in the BT assay, contrary to butyrate. We also mapped oleanolic acid to PTPN7 which can modulate VCAM1 (suppressed in HDF3CGF fibroblast assay) through effects on p38 MAP-kinase (Fig. 5d).

Discussion

We greatly expand the number of potential protein–metabolite interactions based on a well-characterized IBD multi-omics dataset from HMP29 by going beyond conventional associative studies. Machine learning algorithms evaluated the relative importance of each metabolite in the context of the whole metabolomics profile while adoption of a consensus scoring minimized biases across the different methods (Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2). Compared to the HMP2 IBD study, our consensus scoring retrieved more relevant metabolites without recurring to a dysbiosis score, an index derived from the beta-diversity analyses of the metagenomic specimens, which poses issues for reproducibility across cohorts and translatability to treatment purposes22. Patterns of enrichments and depletion expected for UC and CD from the literature or the HMP2 study, were confirmed by our method, such as the depletion of short chain fatty acids like butyrate and valerate in CD and UC23. Thus, we believe that consensus scoring for each metabolite across the whole metabolomic signature of the disease state better defines the hypothesis space for metabolite–target interactions. Additionally, while consensus scores had significantly different distributions between CD and UC patients, it was not particularly impacted by the metabolite ontology (Supplementary Fig. 3) which reflects the strong relationship occurring between diet and microbial metabolism.

Our study detected several metabolites known to have important roles in the disease state then built connections with host metabolism and disease states. For example, nicotinic acid was connected to its known receptor, GPR109 (HCAR2), an interaction known to reduce inflammation in IBD24. This finding was in accordance with experimental evidence showing anti-inflammatory effects of niacin in a HCAR2-dependent manner25. Counterintuitively, we found HCAR2 to be significantly overexpressed in CD and UC patients. HCAR2 is often involved in lipid metabolism26 and colonic inflammation24. We also found that trigonelline, another activator of HCAR2, was overrepresented. Trigonelline has protective effects in IBD DSS mice models27, but is also involved in lipid metabolism, suggesting its role in the HCAR2 upregulation28.

Nicotinuric acid, degradation product of nicotinic acid, was instead connected to LMNA, whose knock-out promotes inflammatory responses in IBD mice models, through increase in CD4+ T-cells29. A potency assay built this connection, so the directionality of this interaction with respect to disease is unclear, but might help to explain nicotinuric acid effects on lymphocytes30. Histamine was enriched in both UC and CD patients and its cognitive receptor HRH4 was over-expressed. Histamine also induced a pro-inflammatory in vitro profile. Collectively, these findings are well-aligned with the proposed contribution of an activated histamine-HRH4 axis in other inflammatory disorders such as Meniere disease31.

Long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (i.e., arachidonic acid, docosapentanoic acid and 8,11,14-eicosatrienoic acid) in IBD are known pro-inflammatory metabolites32 and we detected their significant enrichment in HMP2 study patients. Other metabolites with high consensus score but yet unknown disease implications belong to compound classes associated with either anti-inflammatory (phenylpropanoids33) or pro-inflammatory (cholesteryl esters34) activities.

A deeper understanding of the mechanistic interaction in this disease space is still necessary for the development of IBD therapeutics35. By leveraging a virtual screening approach, we connected metabolites to compounds with measured modulation properties recorded in ChEMBL using 2d-similarity screening via molecular fingerprints. We limited our searches to functional assays in order to have immediate and confident direction of modulation between the compound and the target protein. Purposely, we did not extend computational screening to QSAR models to avoid known pitfalls of predictive associations36 and only defined “positive” modulation (which includes agonist, activators, cofactors, etc.), “negative modulation” (including inhibitors, antagonists, etc.) or “other” for all uncharacterized or unclear interactions. Additionally, we used a target classification based on mechanism of action for drug and treatment37 and found that the most connected proteins were well-known drug targets such as GPCRs, transcriptional factors and various enzymes.

Several host–metabolite pairings emerge from our analyses which have yet to be explored for drug purposes to the best of our knowledge. Hydrocinnamic acid (or phenylpropanoid acid), which is ingested through seeds and metabolized by Clostridia species, has known anti-inflammatory properties33 and was depleted in both UC and CD patients. Hydrocinnamic acid has a mild inhibition effect on toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) which is an activator of innate immunity NF-κB expressing cells38, thus might be useful to dampen the inflammatory response.

Oleanolic acid is a plant triterpenoids with anti-inflammatory properties39. We connected oleanolic acid (and its analog ursanolic acid) to PTPN7 which interacts with MAP-kinases to lower expression of downstream NF-κB40. Oleanolic acid was also connected to GPBAR1, which has anti-inflammatory activity41, as well as GABRG2, which is genetically associated with an increase in macrophage inflammatory protein 1b. The directionality between the GABRG2 genetic variant and the inflammatory phenotype needs further confirmation. In vitro assays performed in this study, provide further confirmation of the immune-modulatory and anti-inflammatory properties of oleanolic acid and lends support to further determination of mechanism of action, perhaps starting with GPBAR1 and PTPN7 mediated responses.

GABRG2 was also connected to several bile acids conjugates. Imbalances between conjugated bile acids operated by the microbial metabolism, such as the detected increase in glycocholate and taurocholate severely impacts the inflammation mechanism through modulation of the farnesoid receptor (FXR)42.

GPR119 is an orphan GPCR (i.e., its endogenous ligand has not been yet identified), which was downregulated in the UC cohort. GPR119 has also been previously linked to endocannabinoid metabolites43 and shows similar mechanistic anti-inflammatory properties in colitis, through release of the glucagon-like peptide GLP-144. Using in vitro assay data, we connected GPR119 with a strong activator underrepresented in IBD patients, linoleoyl ethanolamide, which has been shown to lower LPS-induced macrophage inflammation in dermatitis45. We also made another putative connection between L-acetylcarnitine and CHRNB2, both of which were associated separately in neuronal diseases46.

Retrospective studies suggest that drugs targeting human genes with genetic associations to disease mechanisms might have a higher probability of success in the clinic47,48. Therefore, we sought to align target-metabolite pairings with genetic association to IBD- or inflammation-related phenotypes. The genes NOS2, CXCR1 and CXCR2, which have robust genetic associations with such phenotypes, were also connected to CD or UC disease states through metabolomics and transcriptomics. For example, the connection built between depletion in L-arginine and enrichment in NOS2 confirms the antioxidant effects of L-Arg49. Serotonin receptor HTR4 is another target involved in both the gut-brain axis and inflammation. We found serotonin depletion to the advantage of 5-HTP, its precursor. 5-HTP enrichment has been previously reported for IBD50 and gut microbiota have a key role in modulating serotonin synthesis and regulating 5-HTP production51. We have also confirmed anti-inflammatory effects of serotonin in vitro cell assay (Supplementary Fig. 6).

CXCR1 and CXCR2 were overexpressed in IBD patients while ibuprofen, a negative modulator, was under-represented. Ibuprofen, a well-known nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), was derived from a natural metabolite, propionic acid52. NSAIDs possibly promote exacerbation events in IBD patients, however, a recent meta-analysis of published data failed to find a statistically significant association between NSAID usage and colitis occurrence53. It is unclear whether this cohort of IBD patients was prevented to assume ibuprofen by medical prescription, but the causal determination of such interactions is beyond the scope of this study.

Interestingly, the connections we built included potential biomarkers of disease severity. For example, 7-methylguanine, a biomarker of colorectal cancer54, was connected through 8-aminoguanine with purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP). PNP deficiency is responsible for T-cell lymphopenia55. The anti-directional evidence might suggest that, in the HMP2 cohort, increase in 7-methylguanine does not modulate the immune system, but is rather a consequence of the ongoing dysbiosis in these patients, possibly due to the detected overabundance of E.coli9.

In conclusion, we identified 983 high quality hypothetical connections between gut microbial metabolites and human proteins with potential relevance to IBD and other immune-related diseases. These proposed connections require further experimental validation in order to establish their direct role in disease causality or progression, rather than a consequence of disease dysfunction. Nonetheless, our study highlights the relationship importance of diet and human-hosted microbiota in modulating the immune system responses and provides perspective metabolite–target connections for drug design purposes.

Methods

Statistics reproducibility

Metabolomics and host transcriptomics data were downloaded from the public repository of the HMP2 project, the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Multi-omics Data Base (https://ibdmdb.org/). Samples description, collection, replicates, and preprocessing analyses are described in Lloyd-Price et al.9. Of the original 132 participants only those with metabolomics or transcriptomics samples were included in this analysis, resulting in the sample size and distributions described in Table 1.

Metabolomics data analysis

Peak areas for each metabolite were normalized for each LC/MS method using total sum scaling and isometric log-transformation. The values were then averaged across methods to result in a table of metabolite by samples. PCA was used to filter outlier samples (only two outlier samples were filtered out).

Bootstrap-coupled estimates56 were performed on each metabolite singularly (5000 iterations) using multi-control grouped design (i.e., UC vs nonIBD and CD vs nonIBD) and significance was assessed via Mann–Withey U test (p values were FDR-corrected with Benjamini & Hochberg method)57.

Machine learning analysis was performed as follows: six machine learning classifier methods from Python packages Scikit-learn 0.21.358 (logistic regression, k-nearest neighbors, random forest, 3-layers dense neural net, gaussian naïve Bayes, linear kernel one-vs-rest), XGBoost 0.9059 and a novel generalized version of mixed effects random forest model (with the XGBoost kernel)60 were tested with default parameters to predict diagnosis labels from the transformed metabolomics data matrix. Recruitment site, use of antibiotics and patient age metadata were included in the training matrix as additional features. A 10-fold stratified cross validation was used to avoid overfitting. All methods performances were assessed with the weighted F1-score of the predictions on the holdout test set (15% of the dataset) and the best method was selected for the highest score (XGBoost).

XGBoost was also trained separately with additional hyperparameter tuning using GridSearch 5-fold cross-validation. Then, a generalized mixed effects machine learning model with an XGBoost core, based on the generalized mixed effects random forest60, was trained using participant ID as cluster, hospital site as random effect and sex, age and antibiotics as fixed effect. Explanatory metabolite weight per disease state prediction was assessed for XGBoost and mixed effect XGBoost using feature importance, gain and SHAP values59.

Finally, the following features were scaled in the interval [0,1] and combined to generate the consensus score: (i) FDR-adjusted p value from the Mann–Whitney U test on the bootstrap-coupled estimation; (ii) feature gain per metabolite in the XGBoost model; (iii) feature importance per metabolite in the XGBoost model; (iv) SHAP value per metabolite per disease state in the XGBoost model; (v) feature importance per metabolite in the generalized mixed effects XGBoost model; (vi) SHAP value per metabolite per disease state in the generalized mixed effects XGBoost model. Consensus score was computed by averaging the selected scaled predictors scaling the average between [0,1] and square-root-normalization. Definition of metabolite classes and origin were parsed from The Human Metabolome Database 4.0 (HMDB)61 and summary visualizations were built using Upset visualizations62.

Host transcriptomics data analysis

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP)63 visualizations were built using R package uwot v0.1.8. Count data from biopsies were normalized using R package DESeq2 1.22.264. Due to the important effect of biopsy location on expression data, samples were assigned to a dummy variable representing either ileum or non-ileum biopsies. Differential gene expression per each disease state was analyzed using a formula with DESeq2. Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using protein interaction networks in R package pathfindR 1.3.065 on the Reactome database66. Definition of the target classes of interest for drug design purposes were assigned using a pre-defined target map67.

Similarity searches and ligand-based virtual screening

All metabolites originally present from the metabolomics dataset were used as queries for similarity searches (i.e., before any filtering step). HMDB was used to parse SMILES strings for each metabolite (with additional manual curation to fix mismapping/missing HMDB codes from the original HMP2 study). SMILES strings were converted into 2D chemical fingerprint using Python package RDKit. Similarity searches were performed using Tanimoto and Tverskyα=0.05 similarity scores against compounds in the ChEMBL database v25 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl)68 internally ingested, using ChemAxon MadFast Similarity Search software with default parameters. The full hypothesis space included 2,721,397 unique compound–target pairs from the ChEMBL database. Assays data were then parsed for each compound using their unique ChEMBL ID numbers.

Target selection from genome-wide association studies

Genetic association to IBD, CD and UC an inflammatory conditions was parsed from the GWAS catalog69 (release 2020-07-14) and looking for disease traits containing the keywords “inflammatory”, “Crohn”, “colitis”, “monocyte”, or “lymphocyte”. Mendelian evidence was parsed manually from The Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database (OMIM)70 from reference #266600 which includes Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Additional candidate targets were added manually from a recent comprehensive reviews of IBD-related pathways14. Networks representations are optimized manually via RCy3 and Cytoscape 3.828.

In vitro validation assays

In vitro assays were performed using the Discovery PLUS platform of the BioMAP panel21 at Eurofins Panlabs, Inc. (St Charles, MO, USA). BioMAP systems are constructed with one or more primary cell types from healthy human donors, with stimuli (such as cytokines or growth factors) added to capture relevant signaling networks that naturally occur in human tissue or pathological conditions. Conditions tested are as follows: vascular biology model for inflammatory environment Th1-specific (3C) and a Th2-specific (4H); Th1 inflammatory state specific to arterial smooth muscle cells (CASM3C); monocyte-driven Th1 inflammation (LPS); T cell stimulation (SAg); chronic Th1 inflammation driven by macrophage activation (lMphg); T cell-dependent activation of B cells that occurs in germinal centers (BT); Th1-specific (BE3C) and Th2-specific (BF4T) airway inflammation of the lung; myofibroblast-lung tissue remodeling (MyoF); skin biology (KF3CT) and wound healing (HDF3CGF). Protein biomarker readouts are selected for predictiveness of their mechanism of action. Compounds concentrations were selected based on compound solubility and minimizing cytotoxicity (Table 1). After analysis the most important readouts are assigned to the perspective targets through selected shortest paths on the canonical pathway analysis performed via MetaCore (GeneGo) v20.1 (Thomson Reuters, https://portal.genego.com/).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The study was funded through GSK Consumer Health through a postdoctoral fellowship. The authors would like to David Cooper, Valeriia Sherina, Hoang Tran, Pat Brady, Dinesh Manahdar and Qing Xie at GSK Pharma R&D for their support and technical advice. We would like to also acknowledge the HMP2 study authors for making their data and computer code publicly available.

Author contributions

A.N., J.T. and J.R.B. conceived the study. A.N. analyzed the data. J.T. E.B., S.S. and C.J. performed initial pilot studies and BioMAP profiling. A.N. and J.R.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised subsequent manuscript drafts.

Data availability

All data from the IBD cohort are available at the IBDMDB website (https://ibdmdb.org), including cohort description and sample handling and preprocessing. All pertinent database are publicly available: HMDB61, ChEMBL68, OMIM70 and GWAS catalog13. All other data are provided in Supplementary Data files. Any remaining information is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Scripts to reproduce the analyses are available as downloadable repository71 under Creative Commons 4.0 open license; including instructions to build a Docker image for reproducibility (10.5281/zenodo.4439416).

Competing interests

A.N., S.S., C.J., J.T and J.R.B. were all employees of GlaxoSmithKline at the time of this study. E.B. is an employee of Eurofins.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Andrea Nuzzo, Email: andrea.8.nuzzo@gsk.com.

James R. Brown, Email: jim.brown@kaleido.com

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-021-01822-x.

References

- 1.Blacher E, Levy M, Tatirovsky E, Elinav E. Microbiome-Modulated Metabolites at the Interface of Host Immunity. J. Immunol. 2017;198:572–580. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldridge BB, Rhee KY. Microbial metabolomics: innovation, application, insight. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014;19:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magnúsdóttir S, Thiele I. Modeling metabolism of the human gut microbiome. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018;51:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awany D, et al. Host and microbiome genome-wide association studies: Current state and challenges. Front. Genet. 2019;10:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischbach MA. Microbiome: focus on Causation and Mechanism. Cell. 2018;174:785–790. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colosimo DA, et al. Mapping interactions of microbial metabolites with human G-protein-coupled receptors. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:273–282.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witherden EA, Moyes DL, Bruce KD, Ehrlich SD, Shoaie S. Using systems biology approaches to elucidate cause and effect in host-microbiome interactions. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2017;3:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.coisb.2017.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, Kogej T, Engkvist O. Cheminformatics in drug discovery, an industrial perspective. Mol. Inform. 2018;37:1–7. doi: 10.1002/minf.201800041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd-Price J, et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature. 2019;569:655–662. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proctor LM, et al. The integrative human microbiome project. Nature. 2019;569:641–648. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-01654-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vich Vila A, et al. Gut microbiota composition and functional changes in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018;10:eaap8914. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aap8914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lima AN, et al. Use of machine learning approaches for novel drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2016;11:225–239. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2016.1146250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buniello A, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47:1005–1012. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham DB, Xavier RJ. Pathway paradigms revealed from the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2020;578:527–539. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2025-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson CA, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 29 additional ulcerative colitis risk loci, increasing the number of confirmed associations to 47. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:246–252. doi: 10.1038/ng.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baurecht H, et al. Genome-wide comparative analysis of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis gives insight into opposing genetic mechanisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;96:104–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Almeida A, et al. A new genomic blueprint of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2019;568:499–504. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Astle WJ, et al. The allelic landscape of human blood cell trait variation and links to common complex disease. Cell. 2016;167:1415–1429.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw SY, et al. Genetic and clinical correlates of early-outgrowth colony-forming units. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2011;4:296–304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gren ST, Grip O. Role of monocytes and intestinal macrophages in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1992–1998. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berg EL, Kunkel EJ, Hytopoulos E, Plavec I. Characterization of compound mechanisms and secondary activities by BioMAP analysis. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2006;53:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brüssow H. Problems with the concept of gut microbiota dysbiosis. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020;13:423–434. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venegas DP, et al. Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:277. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhatt B, et al. Gpr109a limits microbiota-induced IL-23 production to constrain ILC3-mediated colonic inflammation. J. Immunol. 2018;200:2905–2914. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salem HA, Wadie W. Effect of niacin on inflammation and angiogenesis in a murine model of ulcerative colitis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-016-0028-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masuda Y, Kurikawa N, Nishizawa T. Overexpressing human GPR109A leads to pronounced reduction in plasma triglyceride levels in BAC transgenic rats. Atherosclerosis. 2018;272:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omidi-Ardali H, Lorigooini Z, Soltani A, Balali-Dehkordi S, Amini-Khoei H. Inflammatory responses bridge comorbid cardiac disorder in experimental model of IBD induced by DSS: protective effect of the trigonelline. Inflammopharmacology. 2019;27:1265–1273. doi: 10.1007/s10787-019-00581-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ilavenil S, et al. Trigonelline attenuates the adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:758–765. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toribio‐Fernández R, et al. Lamin A/C deficiency in CD4 + T‐cells enhances regulatory T‐cells and prevents inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pathol. 2019;249:509–522. doi: 10.1002/path.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montserrat-de la Paz S, et al. Niacin and its metabolites as master regulators of macrophage activation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017;39:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin D, Zhang H, Wang J, Hong Z. Histamine H4 receptor gene polymorphisms: a potential contributor to Meniere disease. BMC Med. Genomics. 2019;12:71. doi: 10.1186/s12920-019-0533-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ananthakrishnan AN, et al. Long-term intake of dietary fat and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2014;63:776–784. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin D, et al. An overview of plant phenolic compounds and their importance in human nutrition and management of type 2 diabetes. Molecules. 2016;21:1374. doi: 10.3390/molecules21101374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi S-H, Sviridov D, Miller YI. Oxidized cholesteryl esters and inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2017;1862:393–397. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plichta DR, Graham DB, Subramanian S, Xavier RJ. Therapeutic opportunities in inflammatory bowel disease: mechanistic dissection of host-microbiome relationships. Cell. 2019;178:1041–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roy K, Das RN, Ambure P, Aher RB. Be aware of error measures. Further studies on validation of predictive QSAR models. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2016;152:18–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chemolab.2016.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santos R, et al. A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017;16:19–34. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eng H-L, Hsu Y-Y, Lin T-M. Differences in TLR7/8 activation between monocytes and macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;497:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.M. Schmidt F, C. Kirkby K, Lichtblau N. Inflammation and immune regulation as potential drug targets in antidepressant treatment. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016;14:674–687. doi: 10.2174/1570159X14666160115130414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim HJ, et al. Oleanolic acid acetate exerts anti-inflammatory activity via IKKα/β suppression in TLR3-mediated NF-κB activation. Molecules. 2019;24:4002. doi: 10.3390/molecules24214002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biagioli M, et al. The bile acid receptor GPBAR1 modulates CCL2/CCR2 signaling at the liver sinusoidal/macrophage interface and reverses acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity. J. Immunol. 2020;204:2535–2551. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wahlström A, Sayin SI, Marschall HU, Bäckhed F. Intestinal crosstalk between bile acids and microbiota and its impact on host metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;24:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grill M, et al. Members of the endocannabinoid system are distinctly regulated in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38865-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee Y-S, Jun H-S. Anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1-based therapies beyond glucose control. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2016/3094642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishida T, et al. Linoleoyl ethanolamide reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in macrophages and ameliorates 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene-induced contact dermatitis in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013;699:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maldonado C, Vázquez M, Fagiolino P. Potential therapeutic role of carnitine and acetylcarnitine in neurological disorders. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020;26:1277–1285. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666200212114038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.King EA, Wade Davis J, Degner JF. Are drug targets with genetic support twice as likely to be approved? Revised estimates of the impact of genetic support for drug mechanisms on the probability of drug approval. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson MR, et al. The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:856–860. doi: 10.1038/ng.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang M, et al. l-Arginine induces antioxidant response to prevent oxidative stress via stimulation of glutathione synthesis and activation of Nrf2 pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018;115:315–328. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kolho, K.-L., Pessia, A., Jaakkola, T., de Vos, W. M. & Velagapudi, V. Faecal and serum metabolomics in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw158 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Yano JM, et al. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell. 2015;161:264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halford GM, Lordkipanidzé M, Watson SP. 50th anniversary of the discovery of ibuprofen: an interview with Dr Stewart Adams. Platelets. 2012;23:415–422. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2011.632032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moninuola OO, Milligan W, Lochhead P, Khalili H. Systematic review with meta-analysis: association between acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis exacerbation. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018;47:1428–1439. doi: 10.1111/apt.14606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sinha R, et al. Fecal microbiota, fecal metabolome, and colorectal cancer interrelations. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Somech R, et al. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency presenting as severe combined immune deficiency. Immunol. Res. 2013;56:150–154. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ho J, Tumkaya T, Aryal S, Choi H, Claridge-Chang A. Moving beyond P values: data analysis with estimation graphics. Nat. Methods. 2019;16:565–566. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple. Test. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pedregosa F, et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011;12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. Proc. ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min. 2016;13-17-Augu:785–794. doi: 10.1145/2939672.2939785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hajjem A, Bellavance F, Larocque D. Mixed-effects random forest for clustered data. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2014;84:1313–1328. doi: 10.1080/00949655.2012.741599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wishart DS, et al. HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D608–D617. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Conway JR, Lex A, Gehlenborg N. UpSetR: an R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2938–2940. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. J. Open Source Softw.10.21105/joss.00861 (2018).

- 64.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ulgen, E., Ozisik, O. & Sezerman, O. U. pathfindR: an R package for comprehensive identification of enriched pathways in omics data through active subnetworks. Front. Genet. 10, 858 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Croft D, et al. The Reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D472–D477. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Santos, R. et al. A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat. Publ. Gr. 10.1038/nrd.2016.230 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Bento AP, et al. The ChEMBL bioactivity database: an update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D1083–D1090. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Buniello A, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D1005–D1012. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hamosh A. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;33:D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nuzzo, A. Drug discovery from metabolites in an IBD cohort. Zenodo 10.5281/zenodo.4439416 (2021).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All data from the IBD cohort are available at the IBDMDB website (https://ibdmdb.org), including cohort description and sample handling and preprocessing. All pertinent database are publicly available: HMDB61, ChEMBL68, OMIM70 and GWAS catalog13. All other data are provided in Supplementary Data files. Any remaining information is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Scripts to reproduce the analyses are available as downloadable repository71 under Creative Commons 4.0 open license; including instructions to build a Docker image for reproducibility (10.5281/zenodo.4439416).