Abstract

Background:

A parental history of major depressive disorder (MDD) is an established risk factor for youth MDD and clarifying the mechanisms related to familial risk transmission is critical. Aberrant reward processing is a promising biomarker of MDD risk; accordingly, the aim of the current study was to test behavioral measures of reward responsiveness and underlying frontostriatal resting activity in healthy adolescents, both with (high-risk) and without (low-risk) a maternal history of MDD.

Methods:

Low-risk and high-risk 12–14-year-old adolescents completed a probabilistic reward task (n = 74 low-risk, n = 27 high-risk) and a resting state MRI scan (n = 61 low-risk, n = 25 high-risk). Group differences in response bias toward reward and resting ventral striatal (VS) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (fALFF) were examined. Computational modeling was applied to dissociate reward sensitivity versus learning rate.

Results:

High-risk adolescents showed a blunted response bias compared to low-risk adolescents. Computational modeling analyses revealed that, relative to low-risk adolescents, high-risk adolescents exhibited reduced reward sensitivity but similar learning rate. Although there were no group differences in VS and mPFC fALFF, groups differed in relationships between mPFC fALFF and response bias. Specifically, among high-risk adolescents, higher mPFC fALFF correlated with a blunted response bias, whereas there was no fALFF-response bias relationship among low-risk youth.

Conclusion:

High-risk adolescents exhibit reward functioning impairments, which is associated with mPFC fALFF. The blunted response bias-mPFC fALFF association may reflect an excessive mPFC-mediated suppression of reward-driven behavior, which may potentiate MDD risk.

Keywords: depression, reward, adolescence, fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuation, familial risk, frontostriatal

Introduction

A parental history of major depressive disorder (MDD) is a robust risk factor for MDD development (1). Thus, clarifying the mechanisms that may facilitate this familial transmission of risk is an important area of research. Reward processing deficits have emerged as a promising mechanism in this area (2). Early adolescence, particularly the ages spanning 12–14, is an important developmental window for studying reward functioning (2), as it is a period of peak sensitivity of reward-related neural regions (3–6) and increased MDD occurrence (7).

Although impaired reward responsiveness characterizes adolescents exhibiting depressive episodes (8,9), behavioral evidence for reward functioning deficits in youth at familial high risk has been mixed. Studies conducted in young children found that high-risk children displayed less positive affect on laboratory tasks relative to low-risk children (10,11). Moreover, a sample of high-risk late adolescents and young adults showed reduced reward seeking compared to low-risk individuals (12). However, others have failed to find blunted reward responsiveness amongst high-risk offspring, or only among those already exhibiting depressive symptoms, making it difficult to tease apart familial risk versus symptom contributions to reward-related deficits (8,13,14) Furthermore, considering developmental differences in neural responsivity to rewards (3–6) some research falls outside early adolescence or spans wide age ranges, which may preclude identifying premorbid reward processing deficits (8,10–14) Additionally, no studies have applied computational modeling analyses to better determine which specific reward processes are impaired in high-risk adolescents, which may help clarify inconsistent findings.

Neuroimaging studies examining ventral striatum (VS) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) correlates of reward functioning as well as electrophysiological studies probing reward-related reward positivity/feedback negativity event-related potentials have yielded more consistent findings among youth at familial risk for MDD. Specifically, mirroring activation patterns seen in adolescents with depression (15–19) relative to low-risk youth, high-risk children and adolescents exhibit reduced VS activation and feedback negativity following rewarding stimuli (16,20–26). With regard to the mPFC, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated evidence for increased mPFC activation during reward processing tasks in MDD (27). However, a study in high-risk young adults reported blunted mPFC activation in response to rewards compared to the low-risk group, suggesting potential differences in those with current MDD vs those at familial risk for depression (28). The mixed findings may also reflect differences in reward task designs.

Examining VS and mPFC activity at rest allows for assessment of neural functioning without the confounds of task design differences. Aberrant VS and mPFC functional activity persist even at rest among those with and at high familial risk for MDD (29,30). Highlighting the importance of these resting neural abnormalities to MDD pathophysiology, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that brain functional alterations at rest may be a more robust biomarker of MDD than task-based neural deficits (31). Intrinsic neural activation at rest can be examined by computing the amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (ALFF) or fractional ALFF (fALFF), a relative measure of ALFF, derived from dividing the resting amplitude within a given power spectra (e.g., 0.008–0.09 Hz) by the total power spectrum (32,33). The fALFF measure is less susceptible to physiological noise and has a higher sensitivity and specificity than ALFF (32,33). Whereas traditional resting state functional connectivity approaches examine co-activation patterns between brain regions, ALFF/fALFF provides an index of the strength of resting activity within a single brain region. Directly pertinent to the current study, several studies have linked ALFF/fALFF to aberrant cognitive functioning in MDD along with illness severity, suggesting relevance for MDD pathophysiology (34–38). Relative to healthy controls, adults with MDD show greater ALFF/fALFF in mPFC and striatal regions (29,30,34,35,37,39,40,41). However, among depressed adolescents there is evidence of less striatal fALFF (42). With respect to at-risk samples, one study found that healthy adult siblings of individuals with MDD showed greater mPFC fALFF compared to those without a sibling with MDD (30). However, to date no study has examined fALFF alterations in high-risk adolescents with a parental history of MDD. Additionally, no one has examined whether VS and mPFC fALFF may track premorbid reward processing impairments in high-risk samples. Notably, studies conducted in healthy individuals have demonstrated that VS and mPFC resting activity and co-activation are linked to individual differences in behavioral responses to rewards (43–45) suggesting that VS and mPFC resting fALFF may serve as promising neural markers underlying reward deficits in high-risk youth.

With the goal of determining whether there are premorbid behavioral and neural alterations impacting reward processes, the current study compared 12–14-year-old healthy adolescents at low- and high-risk for MDD, with risk operationalized as having a maternal MDD history. Group differences in reward responsiveness and reward learning were tested. We expected that high-risk adolescents would exhibit a reduced bias toward a more frequently rewarded stimulus on a probabilistic reward task (PRT, 46) compared to low-risk adolescents. Computational modeling analyses were also conducted on the PRT data, to evaluate whether familial risk for MDD is associated with abnormalities in reward sensitivity (an index of consummatory pleasure in response to rewarding stimuli) and/or learning rate (a measure of the ability to learn from rewarding feedback). Although yet to be conducted in healthy at-risk samples, studies using computational modeling to study reward processes have linked MDD to reward sensitivity (but not learning rate) abnormalities (47,48). Thus, we predicted that, compared to low-risk adolescents, high-risk adolescents would show impaired reward sensitivity, but intact learning rate.

Moreover, given growing evidence supporting the relevance of VS and mPFC fALFF to MDD pathophysiology and reward processing deficits, exploratory analyses examining group differences in fALFF within these regions were conducted. Additionally, relationships between VS and mPFC fALFF with behavioral measures of reward responsiveness and how these associations may differ as a function of MDD risk status were tested. Although resting state MRI studies traditionally focus on one common frequency band (e.g., 0.008–0.09 Hz), evidence points to several independent frequency bands, each with their own unique properties and functions (33,34,49,50). Consequently, different frequency bands have uncovered distinct fALFF abnormalities in psychiatric disorders supporting the importance of assessing multiple frequency bands (34,49,51,52). Pertinent to the current study, low frequency oscillations in the VS are best characterized by a “slow-4”, 0.027–0.073 Hz band (33,49,50). Supporting the functional relevance of different frequency bands, preclinical studies have shown that “slow-4” VS oscillations were selectively modulated by dopaminergic drugs (53–55). Conversely, low frequency fluctuations in the mPFC are maximal in a 0.01–0.027 Hz, “slow-5” band (33,49,50). Thus, we tested VS and mPFC in their respective maximal frequency bands in addition to supplemental analyses within a 0.008–0.09 Hz band. We predicted that high-risk adolescents would show increased VS and mPFC fALFF compared to low-risk adolescents, and that higher fALFF within these regions would be associated with more impaired reward responsiveness.

Methods and Materials

Participants

A total of 95 mothers with no lifetime depressive disorders (low-risk) and current mental health disorders and 32 mothers with a lifetime unipolar depressive diagnosis (high-risk) along with their respective 12–14-year-old adolescent offspring were enrolled (for statistical power considerations, see Supplementary Methods). To allow for unambiguous interpretations, exclusion criteria for all adolescents included lifetime mental disorders, current psychotropic medication use, presence of any medical or neurological illnesses, and any MRI contraindications. Two low-risk participants were excluded given a personal history of non-suicidal self-injury and a current maternal posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis. A high-risk participant was excluded because of a past MDD episode. An additional 19 low-risk and 4 high-risk adolescents failed to pass quality control (QC) criteria for the PRT (see Supplemental Methods). Thus, the final sample included 74 low-risk mother-adolescent (N = 47 female, N = 27 male) dyads and 27 high-risk mother-adolescent (N = 17 female, N = 10 male) dyads. Demographic information and maternal clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1 (see Supplemental Methods for more information about maternal inclusion/exclusion criteria).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Healthy Adolescents at High and Low Familial Risk for Major Depressive Disorder

| Low Risk (N = 74) | High Risk (N = 27) | t/χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% female) | 63.5 | 63.0 | .003 | .959 |

| Age (years, SD) | 12.95 (.86) | 13.19 (.79) | −1.267 | .208 |

| Tanner Scale M (SD) | 3.10 (.59) | 3.10 (.66) | −.002 | .998 |

| Ethnicity (% white) | 86.5 | 85.2 | .028 | .867 |

| Family Income | ≤ $100 K = 24.3% | ≤ $100 K = 29.6% | .053 | .818 |

| > 100 K = 64.9% | > 100 K = 70.4% | |||

| Unreported = 10.8% | Unreported = 0.0% | |||

| Depression Symptoms | 5.78 (6.73) | 8.30 (8.11) | −1.755 | .082 |

| Anhedonia Symptoms | 20.60 (4.72) | 21.37 (4.26) | −.746 | .458 |

| Anxiety Symptoms | 34.12 (11.51) | 42.05 (12.82) | −2.970 | .004 |

| Lifetime Maternal MDD (%) | 0 | 96.3 | ||

| Maternal Depressive NOS (%) | 0 | 3.7 | ||

| Current Depressive Episode | 0 | 7.4 | ||

| Maternal Single Episode (%) | 0 | 48.1 | ||

| Maternal Recurrent Episode (%) | 0 | 51.9 | ||

| Current Panic Disorder (%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Past Panic Disorder (%) | 0 | 3.7 | ||

| Current Social Phobia (%) | 0 | 7.4 | ||

| Past Social Phobia (%) | 1.4 | 18.5 | ||

| Current Specific Phobia (%) | 0 | 7.4 | ||

| Past Specific Phobia (%) | 1.4 | 7.4 | ||

| GAD (%) | 0 | 18.5 | ||

| Current PTSD (%) | 0 | 3.7 | ||

| Past PTSD (%) | 0 | 11.1 | ||

| Current Alcohol/Substance (%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Past Alcohol/Substance (%) | 6.8 | 22.2 |

Note: Depressive symptoms were measured with the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ). Anhedonia symptoms were measured with the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS). Anxiety symptoms were measured with the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC). MDD = Major Depressive Disorder, Maternal Depressive NOS = Maternal Depressive Disorder Not Otherwise Specified, GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Current Alcohol/Substance = Current Alcohol/Substance Use Abuse or Dependence, Past Alcohol/Substance = Past Alcohol/Substance Use Abuse or Dependence

Procedures

The study was approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board. Adolescents assented and their mothers provided written consent. During the first visit, mothers completed a clinical diagnostic interview regarding personal lifetime mental disorders. Adolescents were administered a diagnostic interview about lifetime mental disorders, completed self-report symptom questionnaires, and performed the PRT. Adolescents were invited for a second session involving structural (56), resting state fMRI, and task-based fMRI scans (57,58). Adolescents received $80 and their parents received $20 for their participation.

Clinical Instruments

Diagnostic Interviews

Adolescents were administered the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS-PL, 59), a semi-structured interview that assesses adolescent DSM-IV lifetime mental disorders. Mothers were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (SCID, 60), which assessed lifetime mental disorders. Recorded interviews were randomly selected (KSADS = 10, SCID = 10, evenly split between high-risk and low-risk dyads), for inter-rater reliability analyses. Reliability was excellent (K-SADS mean κ = 1.00, SCID mean κ = .918).

Adolescent Self-Reported Measures

Adolescents completed the Tanner Scale (61), a measure of pubertal status, along with the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ, 62), the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS, 63), and the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC, 64) to assess for depression, anhedonia, and anxiety symptoms, respectively (for more information about clinical measures, see Supplemental Materials). The internal consistency for all clinical symptom measures ranged from good to excellent (MFQ α = .915; SHAPS α =.844; MASC α = .829).

Probabilistic Reward Task

Participants completed a 15-minute computer-based version of the social reward PRT (46). The PRT utilizes signal detection theory to assess a person’s propensity to modify behavior based on reinforcement history. The PRT task consisted of two blocks of 100 trials each. Each trial began with a 500 ms fixation cross followed by a 500 ms face without a mouth. Next, a short mouth (10 mm) or a long mouth (11 mm) was presented briefly on the face for 100 ms. Participants were then asked to determine whether a short mouth or a long mouth was presented with a key press. In each block, social praise feedback was provided for 40 correctly responded trials (“Correct! You are doing well on this task.” along with an image of a medal with “Good Job” written on it). Participants were told to respond as fast and accurate as possible, and that not all correct responses would be followed by feedback. Long and short mouths were presented at equal frequency. However, without the participant’s knowledge, one of the mouth’s length was rewarded three times more frequently (the “rich stimulus”) than the other mouth length (the “lean stimulus”).

Behavioral Data Processing

For detailed information about PRT QC procedures, see the Supplemental Methods. After the QC procedures, response bias and discriminability were computed using the following equations:

To allow computations for instances in which there was zero in the formula, 0.5 was added to every cell in the matrix (46). Mean accuracy and reaction time (RT) also were computed.

Computational Modeling

Consistent with prior work (47,48,65), a series of reinforcement learning models were fitted to the PRT choice data in order to separate the influence of reward sensitivity and learning rate on performance (see Supplemental Methods).

fMRI Acquisition and Pre-processing

Imaging acquisition and fMRI preprocessing details can be found in the Supplemental Methods. Structural and 5-minute resting state fMRI scans were collected on a Siemens Tim Trio 3 Tesla MR scanner. Participants viewed a black screen and were instructed to keep their eyes open. Participants with >20% of their volumes marked as motion-related outliers were removed from fMRI analyses, resulting in 14 adolescents from the low-risk group and 2 adolescents in the high-risk group being excluded from all fMRI analyses. Thus, the final sample for fMRI analyses included 61 low-risk adolescents and 25 high-risk adolescents.

Fractional Amplitude of Low Frequency Fluctuation (fALFF) Analysis

The CONN toolbox (66) was used to conduct the fALFF analysis. Data were passed through both slow-4 (0.027–0.073 Hz) and slow-5 (0.01–0.027 Hz) frequency band filters, along with a third, more typical resting state band pass filter (0.008–0.09 Hz) to test whether putative findings would generalize to a broader filter (findings reported in the Supplement). For each voxel, the filtered time series was transformed to the frequency domain using a Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT). A voxelwise fALFF analysis was conducted by calculating the average square root of power within each of the three frequency bands of interest separately for each voxel and dividing by the total power spectra. All fALFF maps were standardized into subject-level Z-score maps. Mean fALFF measures within pre-defined bilateral VS and mPFC ROI masks were extracted using the function spm_summarise. The VS fALFF measure was extracted from the slow-4 Z-score normalized fALFF map and the mPFC fALFF measure was extracted from the slow-5 Z-score normalized fALFF map. The bilateral VS mask was derived from the Oxford-GSK Imanova structural anatomical striatal atlas (67) and the mPFC mask was derived from a prior resting state fMRI meta-analysis of MDD (68).

Group-Level Statistics

Group differences in age, number of motion outliers, pubertal status, depression, anhedonia, and anxiety symptoms were examined with independent-sample t tests. Group differences in sex, ethnicity, and family income were examined via chi-square tests. A set of Pearson correlations were conducted to characterize relationships between symptom measures.

To examine group differences in response bias and discriminability, we conducted two separate Group (High, Low) x Block (1, 2) mixed model ANCOVAs. Given that there were significant group differences in anxiety symptoms, which may influence reward processing (69), anxiety symptoms were included as a covariate in all statistical models. The two ANOVA tests conducted on traditional PRT metrics (response bias, discriminability) were Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons (p < 0.025).

Two separate ANCOVAs were conducted to examine group differences in reward sensitivity and learning rate parameters. These two tests were Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons (p < 0.025). Finally, two secondary Group x Block x Stimulus (Rich, Lean) mixed model ANCOVAs were conducted to assess group differences in accuracy rates and RT, respectively.

To characterize relationships between response bias, group status, and fALFF measures, we conducted two exploratory multiple linear regressions, with slow-4 VS fALFF and slow-5 mPFC fALFF each serving as the dependent variable, and Group, Response Bias, and Group x Response Bias being predictors as well as covarying for anxiety symptoms. Complementary multiple linear regressions were re-run within the 0.008–0.09 Hz frequency band for both VS and mPFC regions. Another set of secondary multiple linear regressions were conducted to examine possible associations between slow-4 VS and slow-5 mPFC fALFF with the computational modeling derived reward sensitivity and learning rate parameters. Given that fALFF analyses were exploratory, all results are displayed uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Participants Characteristics and Individual Differences Characteristics

Descriptive statistics are summarized in Table 1. High- and low-risk adolescents did not significantly differ in sex, age, pubertal development, ethnicity, or family income. Additionally, high- and low-risk adolescents did not significantly differ in depression (MFQ) and anhedonia (SHAPS) symptoms, however, the high-risk group reported greater anxiety symptom (MASC) levels than the low-risk group, albeit in a range that was not clinically impairing. There were no significant group differences in motion-related fMRI outliers (see Supplemental Results). For correlations between symptom measures, see Supplemental Results.

Probabilistic Reward Task

Response Bias.

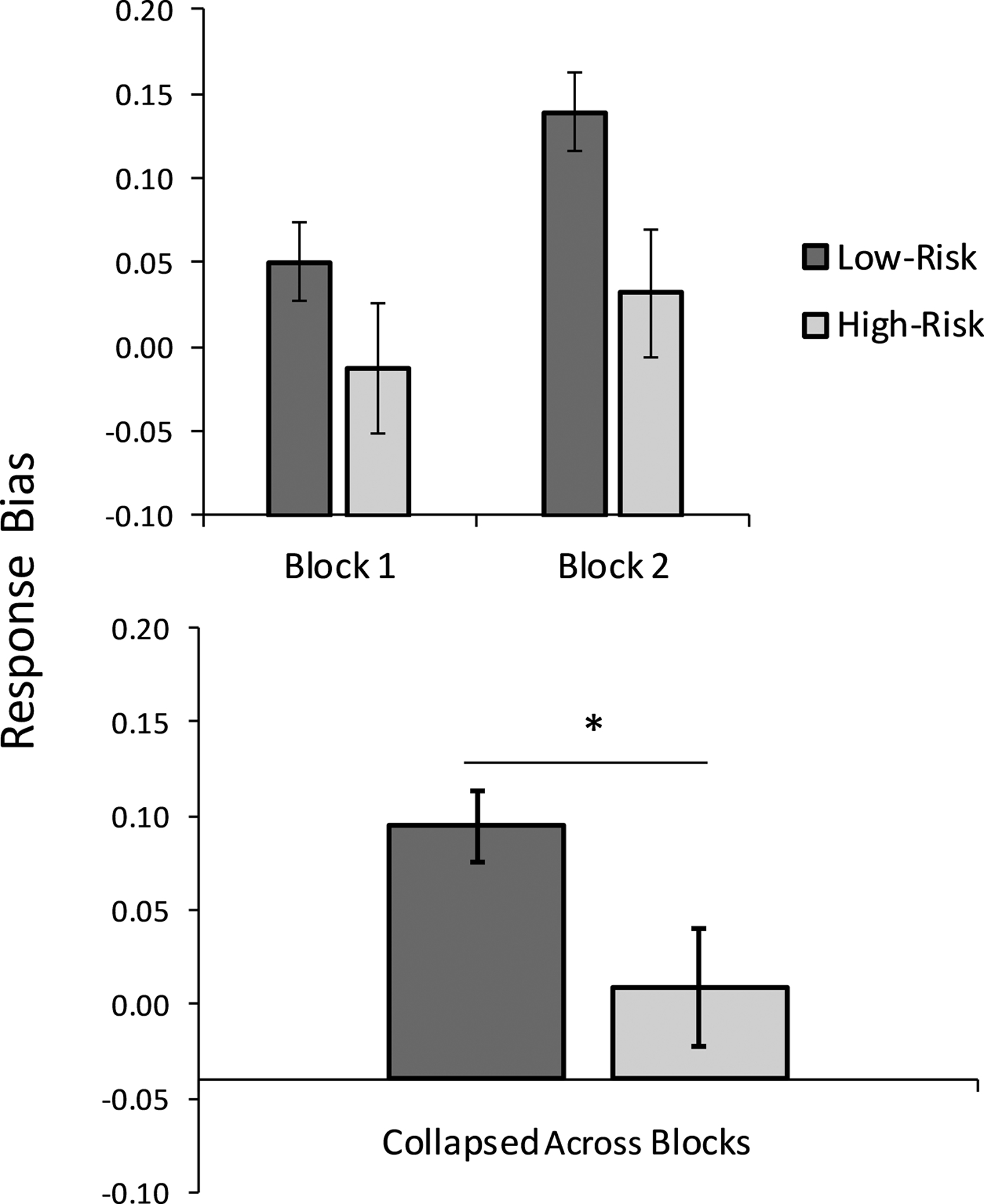

There was a significant main effect of Group, with high-risk adolescents showing a lower overall response bias compared to low-risk adolescents, F(1,98) = 5.302, p = .023, ηp2 = .051 (Figure 1). There also was a main effect of anxiety that did not survive correction for multiple comparisons, with higher anxiety levels being associated with a greater response bias, F(1,98) = 5.053, p = .027, ηp2 = .049. There was no significant main effect of Block or Group x Block interaction, all Fs < 1.000, ps > .300.

Figure 1.

The high-risk adolescent group (n=27) showed an overall significantly reduced response bias toward a more frequently rewarded stimulus relative to the low-risk group (n=74). * p < .05

Discriminability.

The main effect of Group, F(1,98) = .063, p = .803, ηp2 = .001, and Block, F (1,98) = .510, p = .477, ηp2 = .005, and the Group x Block interaction, F(1,98) = .002, p = .964, ηp2 < .001, were not significant. There were no significant main effects or interactions with anxiety, Fs < 2.000, ps >.100.

See Supplementary Results and Figure S1 for results from secondary accuracy and RT variables.

Computational Modeling of Probabilistic Reward Task

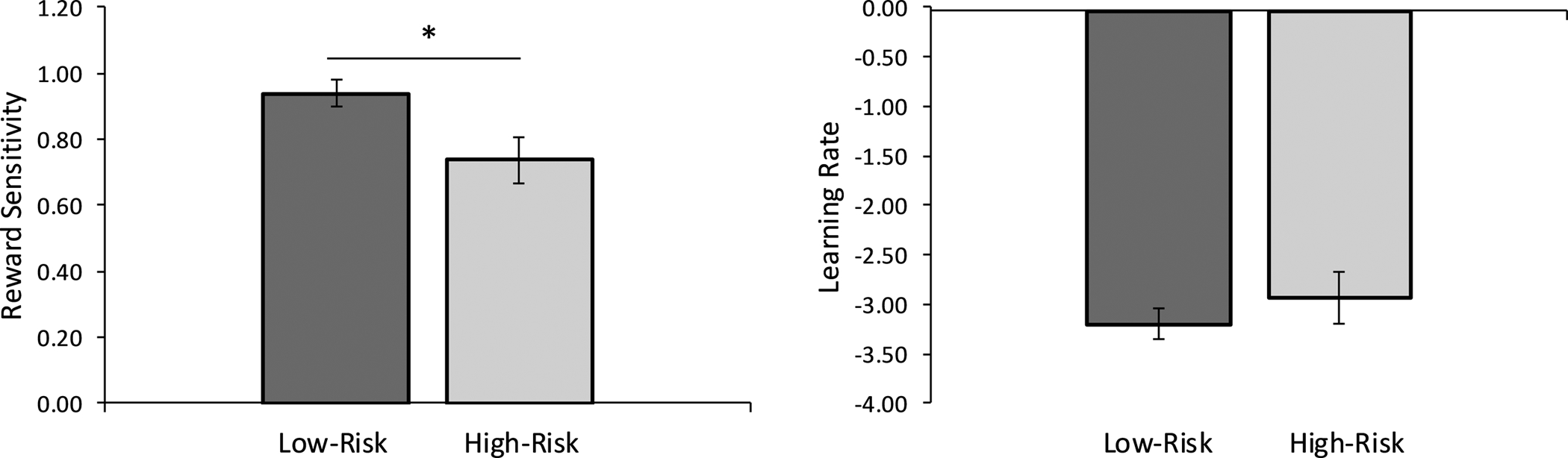

The ANCOVA revealed a significant main effect of Group on the reward sensitivity parameter, F(1,98) = 5.891, p = .017, ηp2 = .057, due to lower reward sensitivity in the high-risk compared to the low-risk group (Figure 2). There was no significant main effect of anxiety, F(1,98) = 1.991, p = .161. Groups did not differ in learning rate, F (1,98) = .429, p = .514, ηp2 = .004 and there was no significant effect of anxiety, F(1,98) = .969, p = .327.

Figure 2.

Computational modeling analyses revealed that the high-risk adolescent group (n=27) exhibited a reduction in reward sensitivity (i.e., consummatory pleasure), but not learning rate (i.e., learning from rewarding feedback) compared to the low-risk adolescent group (n=74). Note that parameters were analyzed in the transformed space to avoid issues with non-Gaussianity; larger magnitude indicates better ability. * p < .05

Exploratory fALFF Results

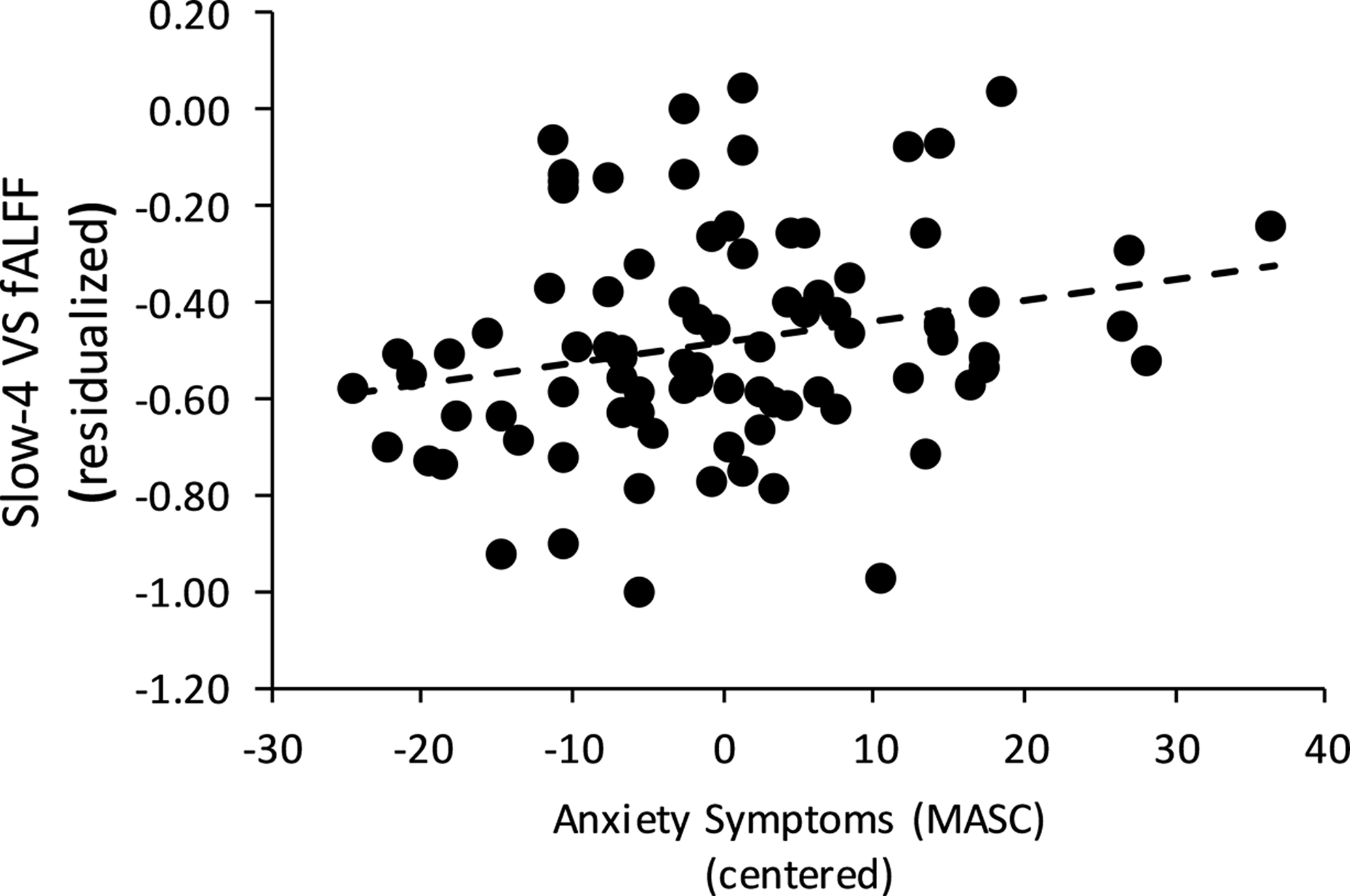

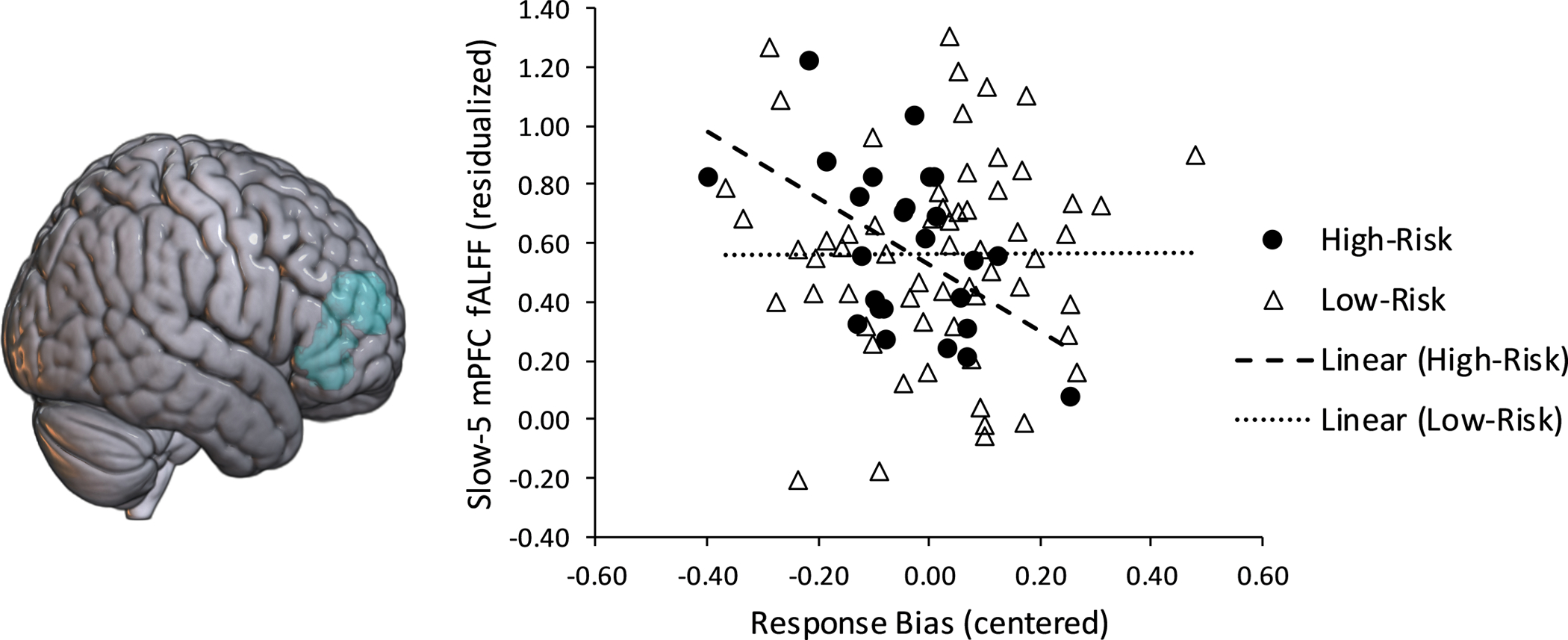

There were no group differences in slow-4 frequency band VS fALFF, β = −.040, B = −.020, t = −.346, p = .730, f2 =0.001. Additionally, there were no significant associations between VS fALFF and response bias, and there were no group differences in slow-4 VS-response bias associations, ps > .300. However, there was a significant main effect of anxiety, with higher levels of anxiety being associated with greater slow-4 VS fALFF, β = .235, B = .004, t = 2.022, partial r = .219, p = .046, f2 = .050 (see Figure 3). With respect to slow-5 mPFC fALFF, there were no significant group differences, β = −.060, B = −.043, t = −.512, p = .610, f2 = .003. There was a trend for a Group x Response Bias interaction on slow-5 frequency band mPFC fALFF, β = −.237, B = −1.100, t = −1.902, p = .061, f2 = 0.04. Follow-up multiple regressions examining each group separately demonstrated that among the high-risk adolescents, a lower response bias was associated with higher mPFC fALFF, β = −.510, B = −1.244, t = − 2.777, partial r = −.509, p = .011 (Figure 4), but a non-significant association amongst low-risk adolescents, β = −.017, B = −.033, t = −.121, partial r = −.016, p = .904. There was no significant main effect of response bias or anxiety symptoms on slow-5 mPFC fALFF, ps > .500. This same pattern of results was found when examining VS and mPFC with the traditional 0.008–0.09 Hz band (see Supplementary Results).

Figure 3.

Higher levels of anxiety on the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) was associated with greater ventral striatum (VS) fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (fALFF).

Figure 4.

Amongst high-risk adolescents (n=25), a lower response bias to the more frequently rewarded stimulus was significantly associated with higher slow-5 frequency band resting medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (fALFF). There were no significant fALFF-response bias associations in the low-risk group (n=61).

Secondary multiple regressions with computational modeling parameters did not show associations between reward sensitivity or learning rate parameters with mPFC or VS fALFF, all ps > .150 Additionally, there were no group differences in associations between the computational modeling derived parameters and mPFC or VS fALFF, all ps > .100.

Supplemental Tables 1–10 contain the full model results for all PRT and imaging analyses.

Follow-up Sensitivity Analyses

All of the above analyses were re-run including Gender as a factor/predictor and controlling for depression and anhedonia symptoms. Additionally, we re-ran the analyses without low-risk participants that had a parent with a past psychiatric diagnosis. The results remained intact under both sets of follow-up analyses (see Supplemental Tables 11–20).

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to test reward system functioning in healthy adolescents at low- and high-risk for MDD owing to a maternal history of depression. Consistent with our hypotheses, compared to the low-risk adolescents, high-risk adolescents showed reward functioning impairments as manifested in reduced response bias toward a more frequently rewarded stimulus. Importantly, these group differences survived when controlling for clinical symptoms, and thus were not unduly influenced by symptomatic differences.

To further understand the mechanisms that may be driving group differences in reward functioning, we conducted computational modeling analyses based on a reinforcement learning model. We tested two possible mechanisms–reward sensitivity (a measure of consummatory pleasure) and learning rate (an index of the ability to learn from rewarding feedback). Results indicated that high-risk adolescents were characterized by lower reward sensitivity, but an intact learning rate compared to low-risk adolescents. This suggests that although high- and low-risk adolescents showed comparable learning rates, high-risk adolescents may find the rewarding information to be less salient, pleasurable, and motivating, which is consistent with prior research implicating reward sensitivity, but not learning rate, in MDD pathophysiology and treatment response (47,48,65). Together, this suggests that reward processing impairments may be a premorbid vulnerability marker for MDD especially prominent during early adolescence. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to test reward sensitivity vs. learning rate impairments among individuals at risk for MDD, and the computational modeling clarified that reduced pleasure in response to rewarding feedback may be the more salient reward-related risk marker present prior to illness onset.

Alterations in resting VS and mPFC fALFF, potentially underlying reward responsiveness impairments in high-risk offspring, were also probed. Contrary to our hypotheses, we did not find group differences in VS and mPFC fALFF. Only one study has examined resting fALFF in a high-risk sample, with results demonstrating that high-risk adults show greater mPFC fALFF compared to low-risk adults (30). Given the sparse work in high-risk samples, it is possible that our findings indicate that VS and mPFC fALFF disruptions emerge after MDD onset. It is also possible that aberrant frontostriatal fALFF is not evident during adolescence yet, or is unique to sibling-risk transmission, as the prior positive finding was exhibited in siblings of adults with MDD. Future work is needed to address these possibilities. However, higher anxiety levels were linked to VS fALFF, which is consistent with prior work linking anxiety pathology to resting striatal dysfunction (70,71). Additionally, there were group differences in how mPFC fALFF related to reward response bias. Specifically, among the high-risk adolescents, higher mPFC fALFF was linked to a lower response bias. Conversely, there were no significant fALFF and response bias associations among low-risk adolescents.

Preclinical work has established that mPFC hyperactivation can suppress adaptive responses to rewarding stimuli (72,73). Consistent with this work, a study conducted in healthy adults showed that higher mPFC fALFF was linked to lower positive affect and psychological resilience (74). Thus, it is possible that the negative association between mPFC fALFF and response bias among high-risk adolescents may reflect an excessive mPFC-mediated top-down regulation of reward-driven behavior. The mPFC is also a core hub of the default mode network (DMN), a network shown to be especially active during rest and is linked to self-referential processes (75). Prior work has consistently reported that the DMN is hyperconnected in MDD (68), and this hyperconnectivity has been linked to rumination (75). Thus, among high-risk adolescents, heightened resting state mPFC activity also may be a marker of maladaptive self-focus that is serving to drive attention away from externally rewarding stimuli in the environment.

While the association between response bias and mPFC fALFF amongst high-risk adolescents is preliminary, our results suggest that adolescents with a maternal risk for MDD paired with a reduced reward response bias and hyperactive mPFC resting activity may be especially vulnerable to the development of future depressive episodes. Consistent with this assertion, longitudinal studies found that high-risk adolescents who engaged in less reward-seeking or exhibited blunted reward positivity were more likely to experience depressive symptoms at a follow-up assessment (9,76). Given that this is the first study to link fALFF with reward processes, future work will be needed to corroborate the findings.

Our study has several strengths, including a focus on an early adolescent developmental period marked by enhanced reward neural system sensitivity (3–6). Additionally, all adolescents were free of psychopathology and psychotropic medication, which allowed for testing whether dysfunctional reward functioning might serve as a premorbid risk factor. However, there were limitations, including the relatively small sample of high-risk adolescents compared to the larger sample of low-risk adolescents. Moreover, although focusing on healthy high-risk adolescents strengthened the ability to test aberrant reward processes prior to illness onset, it may also dampen generalizability of the findings. Despite these limitations, our study provides critical evidence of reward processing impairments in a sample of healthy adolescents at high-risk for MDD. This work supports research establishing reward dysfunction as a premorbid vulnerability marker for MDD and lays the foundation for future longitudinal work to determine whether premorbid reward processing abnormalities amongst high-risk adolescents predict later depressive episode emergence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Tommy Fuss Fund (RPA, DAP), Dana Foundation (DAP, RPA) and Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation (RPA). DAP (R37MH068376, 5R01MH108602) and RPA (R01MH119771, U01MH108168) were partially supported by funds from the National Institute of Mental Health. ELB was partially supported by a Kaplen Postdoctoral Fellowship (Harvard Medical School), an Adam J. Corneel Young Investigator Award (McLean Hospital), the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation, and the National Institute of Mental Health (1K23MH122668). YA was supported by a Kaplen Postdoctoral Fellowship from Harvard Medical School and a National Science Scholarship from the Agency of Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

Over the past 3 years, Dr. Pizzagalli has received consulting fees from Akili Interactive Labs, BlackThorn Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Compass Pathway, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals; one honorarium from Alkermes, and research funding from NIMH, Dana Foundation, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Millennium Pharmaceuticals. In addition, he has received stock options from BlackThorn Therapeutics. Dr. Pizzagalli has a financial interest in BlackThorn Therapeutics, which has licensed the copyright to the Probabilistic Reward Task through Harvard University. Dr. Pizzagalli’s interests were reviewed and are managed by McLean Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. No funding from these entities was used to support the current work, and all views expressed are solely those of the authors. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H (2006): Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. Am J Psychiatry 163: 1001–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luking KR, Pagliaccio D, Luby J, Barch DM (2016): Reward processing and risk for depression across development. Trends Cogn Sci 20: 456–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg L, Graham S, O’Brien L, Woolard J, Cauffman E, Banich M, (2009): Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Dev 80 (1): 28–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Leijenhorst L, Moor BG, Op de Macks ZA,Rombouts SARB, Westernberg PM, Crone EA (2010):Adolescent risky decision-making: neurocognitive development of reward and control regions. NeuroImage 51: 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cauffman E, Shulman EP, Claus E, Banich MT, Steinberg L, Graham S (2010): Age differences in affective decision making as indexed by performance on the Iowa gambling task. Dev Psychol 46 (1): 193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spear LP (2011): Rewards, aversions and affect in adolescence: Emerging convergences across laboratory animal and human data. Dev Cogn Neurosci 1: 390–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beesdo K, Hofler M, Leibenluft E, Lieb R, Bauer M, Pfenning A (2009): Mood episodes and mood disorders: patterns of incidence and conversion in the first three decades of life. Bipolar Disord 11: 637–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris BH, Blysma LM, Yaroslavsky I, Kovacs M, Rottenberg J (2015): Reward learning in pediatric depression and anxiety: Preliminary findings in a high-risk sample. Depress Anxiety 32: 373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rawal A, Collishaw S, Thapar A, Rice F (2013): ‘The risks of playing it safe’: A prospective longitudinal study of response to reward in the adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Psychol Med 43: 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durbin CE, Klein DN, Hayden EP, Buckley ME, Moerk KC (2005): Temperamental emotionality in preschoolers and parental mood disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 114: 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olino TM, Lopez-Duran N, Kovacs M, George CJ, Gentzler AL, Shaw DS (2011): Developmental trajectories of positive and negative affect in children at high and low familial risk for depressive disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52: 792–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannie ZN, Williams C, Browning M, Cowen PJ (2015): Decision making in young people at familial risk for depression. Psychol Med 45: 375–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W-H, Roiser JP, Wang L-Z, Zhu Yu-hua, Huang J, Neumann DL et al. (2016): Anhedonia is associated with blunted reward sensitivity in first-degree relatives of patients with major depression. J Affect Disord 190: 640–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luking KR, Pagliaccio D, Luby J, Barch DM (2015): Child gain approach and loss avoidance behavior: Relationships with depression risk, negative mood, and anhedonia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54: 643–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forbes EE, Hariri AR, Martin SL, Silk JS, Moyles DL, Fisher PM, et al. (2009): Altered striatal activation predicting real-world positive affect in adolescent major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 166: 64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharp C, Kim S, Herman L, Pane H, Reuter T, Strathearn L (2014): Major depression in mothers predicts reduced ventral striatum activation in adolescent female offspring with and without depression. J Abnorm Psychol 123: 298–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bress JN, Foti D, Kotov R, Klein DN, Hajcak G (2013): Blunted neural response to rewards prospectively predicts depression in adolescent girls. Psychophysiology, 50(1): 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson BD, Perlman G, Klein DN, Kotov R, Hajcak G (2016): Blunted neural response to rewards as a prospective predictor of the development of depression in adolescent girls. Am J Psychiatry 173(12): 1223–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson BD, Infantolino ZP, Klein DN, Perlman G, Kotov R, Hajcak G (2018): Time-frequency reward-related delta prospectively predicts the development of adolescent-onset depression. Biol Psychiatry: Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 3(1): 41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monk CS, Klein RG, Telzer EH, Schroth EA, Mannuzza S, Moulton JL, et al. (2008): Amygdala and nucleus accumbens activation to emotional facial expressions in children and adolescents at risk for major depression. Am J Psychiatry 165:90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olino TM, McMakin DL, Morgan JK, Silk JS, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, et al. (2014): Reduced reward anticipation in youth at high-risk for unipolar depression: a preliminary study. Dev Cogn Neurosci 8: 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olino TM, Silk JS, Osterritter C (2015): Forbes EE Social reward in youth at risk for depression: a preliminary investigation of subjective and neural differences. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol 25: 711–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerestes R, Segreti AM, Pan LA, Phillips ML, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Ladouceur CD (2016): Altered neural function to happy faces in adolescents with and at risk for depression. J Affect Disord 192: 143–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luking KR, Pagliaccio D, Luby JL, Barch DM (2016): Depression risk predicts blunted responses to candy gains and enhanced responses to candy losses in healthy children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychol 55: 328–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kujawa A, Proudfit GH, Klein DN (2014): Neural reactivity to rewards and losses in offspring of mothers and fathers with histories of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 123(2): 287–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kujawa A, Burkhouse KL (2017): Vulnerability to depression in youth: Advances from affective neuroscience. Biol Psychiatry: Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2(1): 28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng TH, Alloy LB, Smith DV (2019): Meta-analysis of reward processing in major depressive disorder reveals distinct abnormalities within the reward circuit. Trans Psychiatry 9(293): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCabe C, Woffindale C, Harmer CJ, Cowen PJ (2012): Neural processing of reward and punishment in young people at increased familial risk of depression. Biol Psychiatry 72: 588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li W, Chen Z, Wu M, Zhu H, Gu L, Zhao Y, et al. (2017): Characterization of brain blood flow and the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in major depressive disorder: A multimodal meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 210: 303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu C-H, Ma X, Wu X, Fan T-T, Zhang Y, Zhou F-C, et al. (2013) : Resting-state brain activity in major depressive disorder patients and their siblings. J Affect Disord 149: 209–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kambietz J, Cabral C, Sacchet MD, Gotlib IH, Zahn R, Serpa MH, et al. (2017) : Detecting neuroimaging biomarkers for depression : A meta-analysis of multivariate pattern recognition studies. Biol Psychiatry 82: 330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou QH, Zhu CZ, Yang Y, Zuo X-N, Long X-Y, Cao Q-J, et al. (2008): An improved approach to detection of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) for resting-state fMRI: fractional ALFF. J Neurosci Methods 172: 137–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuo X-N, Di Martino A, Kelly C, Shehzad ZE, Gee DG, Klein DF, et al. (2010): The oscillating brain: Complex and reliable. Neuroimage 49: 1432–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tadayonnejad R, Yang S, Kumar A, Ajilore O (2015): Clinical, cognitive, and functional connectivity correlations of resting-state intrinsic brain activity alterations in unmedicated depression. J Affect Disord 172: 241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang M, Lu S, Yu L, Li L, Zhang P, Hu J, et al. (2017): Altered fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuation associated with cognitive dysfunction in first-episode drug-naïve major depressive disorder patients. BMC Psychiatry 17: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider I, Schmitgen MM, Bach C, Listunova L, Kienzle J, Sambataro F (2019): Cognitive remediation therapy modulates intrinsic neural activity in patients with major depression. Psychol Med 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jing B, Liu C-H, Ma X, Yan H-G, Zhuo Z-Z, Zhang Y, et al. (2013): Difference in the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation between currently depressed and remitted females with major depressive disorder. Brain Res 1540: 74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chun-Hong L, Li-Rong T, Yue G, Guang-Zhong Z, Bin L, Meng L, et al. (2019): Resting-state mapping of neural signatures of vulnerability to depression relapse. J Affect Disord 250:371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang X, Dai X, Edmiston E, Zhou Q, Ku K, Zhou Y, et al. (2017): Alteration of cortico-limbic-striatal neural system in major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 221: 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhong X, Pu W, Yao S (2016): Functional alterations of fronto-limbic circuit and default mode network systems in first-episode, drug-naïve patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of resting state data. J Affect Disord 206: 280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schu Y, Kuang L, Huang Q, He L (2020): Fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (fALFF) alterations in young depressed patients with suicide attempts after cognitive behavioral therapy and antidepressant medication cotherapy: A resting-state fMRI study. J Affect Disord 276: 822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiao Q, Ding J, Guanming L, Su L, Zhang Z, Wang Z, et al. (2011): Increased activity imbalance in fronto-subcortical circuits in adolescents with major depression. PLoS ONE 6(9): e25159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Massar SAA, Kenemans JL, Schutter DLG (2014): Resting-state EEG theta activity and risk learning: sensitivity to reward or punishment? Int J Psychophysiol 91: 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Duijvenvoorde ACK, Achterberg M, Braams BR, Peters S, Crone EA (2016): Testing a dual-systems model of adolescent brain development using resting-state connectivity analyses. Neuroimage 124: 409–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaiser RH, Treadway MT, Wooten DW, Kumar P, Goer F, Murray L, et al. (2018): Frontostriatal and dopamine markers of individual differences in reinforcement learning: A multi-modal investigation. Cereb Cortex 28: 4281–4290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pizzagalli DA, Iosifescu D, Hallett LA, Ratner KG, Fava M (2008): Reduced hedonic capacity in major depressive disorder: Evidence from a probabilistic reward task. J Psychiatr Res 43: 76–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huys QJ, Pizzagalli DA, Bogdan R, Dayan P (2013): Mapping anhedonia onto reinforcement learning: a behavioural meta-analysis. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord 3: 12–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ang Y-S, Kaiser R, Deckersbach T, Almeida J, Phillips ML, Chase HW, et al. (in press): Pretreatment reward sensitivity and frontostriatal resting-state functional connectivity are associated with response to bupropion after sertraline non-response. Biol Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu R, Chien Y-L, Wang H-LS, Liu C-M, Liu CC, Hwang T-J, et al. , (2014): Frequency-specific alternations in the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in schizophrenia. Hum Brain Mapp 35: 627–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xue S-W, Li D, Weng X-C, Northoff G, Li D-W (2014): Different neural manifestations of two slow frequency bands in resting functional magnetic resonance imaging: A systematic survey at regional, interregional, and network levels. Brain Connect 4: 242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yue Y, Jia X, Hou Z, Zang Y, Yuan Y (2015): Frequency-dependent amplitude alterations of resting state spontaneous fluctuations in late-onset depression. Biomed Res Int Article ID 505479: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gimenez M, Guinea-Izquierdo A, Villalta-Gil V, Martinez-Zalacain I, Segalas C, Subira M (2017): Brain alterations in low-frequency fluctuations across multiple bands in obsessive compulsive disorder. Brain Imaging Behav 11: 1690–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruskin DN, Bergstrom DA, Kaneoke Y, Patel BN, Twery MJ, Walters JR. (1999): Multisecond oscillations in firing rate in the basal ganglia: robust modulation by dopamine receptor activation and anesthesia. J Neurophysiol 81:2046–2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruskin DN, Bergstrom DA, Mastropietro CW, Twery MJ, Walters JR (1999): Dopamine agonist-mediated rotation in rats with unilateral nigrostriatal lesions is not dependent on net inhibitions of rate in basal ganglia output nuclei. Neuroscience 91:935–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruskin DN, Bergstrom DA, Shenker A, Freeman LE, Baek D, Walters JR (2001): Drugs used in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder affect postsynaptic firing rate and oscillation without preferential dopamine autoreceptor action. Biol Psychiatry 49:340–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Auerbach RP, Pisoni A, Bondy E, Kumar P, Stewart JG, Yendiki A, Pizzagalli DA (2017): Neuroanatomical prediction of anhedonia in adolescents. Neuropsychopharmacology 42: 2087–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumar P, Pisoni A, Bondy E, Kremens R, Singleton P, Pizzagalli DA, Auerbach RP (2019): Delineating the social valuation network in adolescents. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 14: 1159–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lincoln SH, Pisoni A, Bondy E, Kumar P, Singleton P, Hajcak G, et al. (2019): Altered reward processing following an acute social stressor in adolescents. PLoS ONE 14(1): e0209361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci D, et al. (1997): Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36: 980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.First MB., Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (2002): Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tanner JM, Davies PS (1985): Clinical longitudinal standards for height and height velocity for North American children. J Pediatr 107: 317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daviss WB, Birmaher B, Melhem NA, Axelson DA, Michaels SM, Brent DA (2006): Criterion validity of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire for depressive episodes in clinic and non-clinic subjects. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47: 927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Snaith RP, Hamilton M, Morley A, Humayan D, Hargraeves D, Trigwell P (1995): A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone: The Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale. Br J Psychiatry 165: 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK (1997): The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. JAm Acad Child Psy 36: 554–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitton AE, Reinen JM, Slifstein M, Ang Y-S, McGrath PJ, Iosifescu DV, et al. (2020): Baseline reward processing and ventrostriatal dopamine function are associated with pramipexole response in depression. Brain 143: 701–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Nieto-Castanon A (2012): Conn: A functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect 2: 125–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tziortzi AC, Searle GE, Tzimopoulo S, Salinas C, Beaver JD, Jenkinson M, et al. (2011): Imaging dopamine receptors in humans with [11C]-(+)-PHNO: dissection of D3 signal and anatomy. Neuroimage 54: 264–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kaiser RH, Andrews-Hanna JR, Wager TD, Pizzagalli DA (2015): Large – scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA Psychiatry 72: 603–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Silk JS, Davis S, McMakin DL, Dahl RE, Forbes EE (2012): Do anxious children become depressed teenagers?: The role of social evaluative threat and reward processing. Psychol Med 42: 2095–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cui Q, Sheng W, Chen Y, Pang Y, Lu Fengmei, Tang Q et al. (2020): Dynamic changes of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Hum Brain Mapp 41:1667–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lai C-H, Wu Y-T (2012): Patterns of fractional amplitude of low-frequency oscillations in occipito-striato-thalamic regions of first-episode drug-naïve panic disorder. J Affect Disord 142: 180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ferenczi EA, Zalocusky KA, Liston C, Grosenick L, Warden MR, Amatya D, et al. (2016): Prefrontal cortical regulation of brainwide circuit dynamics and reward-related behavior. Science 351: aac9698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laith A, Gaskin PLR, Sawiak SJ, Fryer TD, Hong YT, Cockcroft GJ, et al. (2019) : Fractionating blunted reward processing characteristic of anhedonia by over-activating primate subgenual anterior cingulate cortex. Neuron 101: 307–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kong F, Ma X, You X, Xiang Y (2018): The resilient brain: Psychological resilience mediates the effect of low-frequency fluctuations in orbitofrontal cortex on subjective well-being in young healthy adults. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 13: 755–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marchetti I, Koster EHW, Sonuga-Barke EJ, De Raedt R (2012): The default mode network and recurrent depression: A neurobiological model of cognitive risk factors. Neuropsychol Rev 22: 229–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kujawa A, Hajcak G, Klein DN (2019): Reduced reward responsiveness moderates the effect of maternal depression on depressive symptoms in offspring: evidence across levels of analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 60: 82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.