Abstract

Background

Patient participation in clinical trials is vital for knowledge advancement and outcomes improvement. Few adult cancer patients participate in trials. Although patient decision-making about trial participation has been frequently examined, the participation rate for patients actually offered a trial is unknown.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis using 3 major search engines was undertaken. We identified studies from January 1, 2000, to January 1, 2020, that examined clinical trial participation in the United States. Studies must have specified the numbers of patients offered a trial and the number enrolled. A random effects model of proportions was used. All statistical tests were 2-sided.

Results

We identified 35 studies (30 about treatment trials and 5 about cancer control trials) among which 9759 patients were offered trial participation. Overall, 55.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 49.4% to 60.5%) of patients agreed to enroll. Participation rates did not differ between treatment (55.0%, 95% CI = 48.9% to 60.9%) and cancer control trials (55.3%, 95% CI = 38.9% to 71.1%; P = .98). Black patients participated at similar rates (58.4%, 95% CI = 46.8% to 69.7%) compared with White patients (55.1%, 95% CI = 44.3% to 65.6%; P = .88). The main reasons for nonparticipation were treatment choice or lack of interest.

Conclusions

More than half of all cancer patients offered a clinical trial do participate. These findings upend several conventional beliefs about cancer clinical trial participation, including that Black patients are less likely to agree to participate and that patient decision-making is the primary barrier to participation. Policies and interventions to improve clinical trial participation should focus more on modifiable systemic structural and clinical barriers, such as improving access to available trials and broadening eligibility criteria.

The participation of cancer patients in clinical trials is fundamental to their successful conduct and, thus, to the advancement of new treatments that improve outcomes for all patients. Yet, the vast majority of adult cancer patients do not participate in trials, with rates of trial participation over several decades ranging from 2% to (more recently) 8% (1–5). Given this, extensive research has focused on the reasons patients choose not to participate in clinical trials, implicitly suggesting that the burden of decision-making—and consequently inadequate participation rates—is largely on the patients themselves.

Recent literature has highlighted how the treatment decision-making process for cancer patients is long and beset with potential barriers that can deny patients the opportunity to even consider trial participation (5). Institutional conduct of clinical trials requires an investment of resources and time that can be prohibitive, especially for nonacademic institutions (6). Without ready access to trials, many patients need to travel long distances to participate in an available trial. This structural barrier precludes trial participation for more than half of all cancer patients (5). Among remaining patients, nearly half are clinically ineligible for a trial. The reduction of clinical barriers has been a major focus of research and advocacy organizations (7). Yet, even if patients are eligible for an available trial, physicians may not offer the trial to patients out of concerns about the physician–patient relationship, preferences for a specific treatment, or practical considerations about reimbursement, time, and clinic resources (8–10). Importantly, these patterns may also differ by demographic and socioeconomic variables (11). Indeed, a key concern has been the low rate of minority enrollment to clinical trials—especially pharmaceutical company–sponsored trials—which may weaken confidence in the applicability of trial findings and demonstrates reduced access to potentially breakthrough treatments (11–13).

Given the layers of structural, clinical, and physician barriers to patient participation in clinical trials, most patients have very limited opportunity to even consider trial participation as an option for their cancer care. In this context, a key question is, what is the rate of trial participation among patients who are actually offered an opportunity to participate? The answer to this question is important for guiding the research and resources aimed at improving participation in clinical trials. To address this, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizing studies about patient participation in cancer trials published over the past 20 years.

Methods

Study-Level Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We identified studies that evaluated the participation of cancer patients in clinical trials. Studies focused on participation to either treatment trials or cancer control trials were included. Studies must have documented the number of patients offered trial participation and the number who enrolled (the denominator and numerator, respectively, for calculating study-specific rates). Studies were required to have been conducted in the United States.

Studies examining individuals at risk of cancer (ie, screening studies) were excluded, as such individuals—in the absence of an actual cancer diagnosis—may have a qualitatively different attitude about study participation. Studies of patient-level interventions to improve the rate at which patients agree to participate in trials were excluded, based on the concern that agreement rates from these studies may not truly represent those commonly observed in trial recruitment. Studies utilizing patient navigators to facilitate enrollment to trials were similarly excluded, as were studies examining the intention to participate, rather than actual participation.

Patient-Level Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Each included study provided a base case assessment of the number of patients offered a trial and the number enrolled. However, some modifications were made to emphasize the agency of patients in determining trial participation and to ensure consistency across the panel of included studies. Patients who were offered a trial but died before enrollment were excluded, because they were not at risk of trial participation. Similarly, patients offered a trial who did not participate because of physician decision or physician barriers were also excluded from the denominator. In contrast, patients reported as not enrolling because of receipt of supportive or palliative care were included if they were initially deemed eligible for trial participation. Further, patients reported as having been offered a trial but not enrolling because they did not return to the site, patients who were lost to follow-up, or patients who were considered to have been seeking a second opinion were included, based on the (conservative) assumption that these reasons are associated with passive refusal to participate in a trial. All other patients offered a trial who did not enroll were included in study-specific calculations.

Literature Search

We conducted a computerized literature search using the PubMed, Web of Science, and Ovid Medline databases under Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines for articles published between January 1, 2000, and January 1, 2020 (20 years in total) (14). We used the search terms “clinical trial accrual,” “clinical trial enrollment,” “enrollment in clinical trials,” “clinical trial enrollment barriers,” “patient participation in clinical trials,” “patient decision making,” or “participation factors” in combination with the term “cancer” (Supplementary Table 1, available online). The search was conducted in January 2020.

Study Selection, Quality Assessment, and Data Extraction

Titles, abstracts, and full studies were independently screened by 3 reviewers (RV, CT, and JMU). This reduced the opportunity for subjective interpretation of study-level results and better ensured consistent data collection. Differences between reviewers about the appropriateness of including particular studies were resolved by consensus. To limit the potential for publication bias, both published abstracts and full articles meeting inclusion criteria were included. Web of Science and Ovid Medline search results included published abstracts and posters in addition to full articles, whereas PubMed only included full articles.

Variable Definitions

Treatment trials were those for which cancer patients received any kind of systemic (hormonal, cytotoxic, immunologic, targeted), radiation, or surgical cancer treatment. Cancer control studies included survivorship and symptom management studies. Studies were also described according to whether patients were treated at academic or community sites. Studies that were about participation in both treatment and cancer control trials, or included both academic and community sites, were grouped according to the category comprising more than 75% of patients; otherwise, the study was categorized as mixed.

Studies were also described according to multiple design characteristics as follows: 1) requirement for patients to provide consent to study their trial participation decision-making vs not; 2) reliance on patient report of trial participation vs physician report or abstraction from the medical record; and 3) prospective vs retrospective data collection.

Race and ethnicity groups included the mutually exclusive categories White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian.

Statistical Analysis

We used meta-analysis for single proportions using the R-package “metaphor” (15,16).

Forest plots were used to summarize individual study effects. Both fixed and random effects approaches were considered for deriving summary rates. The use of fixed effects is predicated on the idea that effect size differences are assumed to vary because of sampling error only; in this case, summary measures are simply weighted by study sample size (17,18). We tested this assumption using the Q statistic (to assess between-study heterogeneity) and the I2 statistic (to assess the proportion of total variation in study estimates due to study heterogeneity) (19–21). A statistically significant Q statistic or an I2 statistic greater than 50% suggests that a random effects approach, which accounts for both within- and between-study variation, is preferable (17,18,21,22). A restricted maximum-likelihood estimator of the between-study variance was used (23,24).

We used meta-analysis for single proportions to derive the rate of trial participation among all studies. We also used meta-regression techniques for moderator analyses to compare the rates of trial participation between patients in treatment vs cancer control studies. The absence of statistically significant evidence of a difference in rates between treatment and cancer control studies provided the rationale to aggregate across all included studies when deriving an overall rate of patient participation, as well as rates by cancer care setting and by race and ethnicity. Analyses were also conducted separately within studies about treatment and cancer control, because patients in the treatment vs the survivorship or symptom management phase of a cancer diagnosis may have qualitatively different expectations about the value of participating in a study.

Patients who consent to participate in a secondary study about trial decision-making may be more likely to ultimately agree to participate in a clinical trial. To address this, we compared estimates of trial participation between studies requiring vs not requiring consent using meta-regression techniques for moderator analyses (25). If a statistically significant difference was evident, analyses were conducted separately within groups defined by this variable; otherwise, results were aggregated across all studies.

Moderator analyses were also used to assess whether rates differed by community vs academic study setting, given the different commitment to trial research that is prevalent between these care settings and because many more patients (generally estimated at 80% or higher) are treated at community sites (26–28). Additionally, we examined whether the results differed by prospective vs retrospective design and by the source of report of trial participation (patient vs physician).

Rates of trial participation among race and ethnicity groups were also calculated using meta-analysis for single proportions (15,16). Additionally, we tested whether rates of participation for Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients differed from rates for White patients among studies that provided data on participation rates for both the minority race or ethnicity group and White patients. The odds ratio of trial participation (minority group vs White) was estimated and tested whether it was different from 1.0 (15).

All statistical tests were 2-sided. P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Additional Analyses

We examined whether the findings were sensitive to the influence of individual studies by iteratively excluding each study and recalculating the overall estimates (a “leave one out” analysis). To assess whether patterns of agreement to participate changed over calendar time, we conducted a simple linear regression of the study-specific estimates, indexed by the median year of the specified time period of study conduct, and tested whether the slope of the regression coefficient differed from zero. For studies that did not specify the year(s) of conduct, mean imputation was used, using the mean of the difference between study publication year and specified years of conduct among studies with known data. We also used the Begg rank correlation test to identify any evidence of publication bias using the ranktest function in R (15,29).

Although the goal was to derive a representative estimate of trial participation rates among those offered a trial, the rate depends in part on analysis assumptions. In sensitivity analysis, we examined the potential lower and upper bounds on the estimate of the trial participation rate by ignoring all anticonservative and conservative assumptions about patient-level exclusions or inclusions, respectively. To estimate the potential lower bound, we included all patients in study-specific denominators who were explicitly indicated in the study publications as having been offered a trial, even if the patients did not meet our definition of being at risk of trial participation. These included patients who died, had no trial available, were ineligible, or did not participate because of physician decision. Conversely, to establish the potential upper bound on the trial participation estimate, we excluded from the study-specific denominators all patients who did not return or were lost to follow-up, because these patients may have participated in a trial elsewhere. Further, we retained the exclusion of patients who died, but also excluded from the denominator patients in supportive or hospice care based on the idea that such patients are at minimal risk of trial participation.

Reasons for nonparticipation among patients who did not enroll in clinical trials were described. To enable calculations across studies, category totals for studies that allowed more than 1 reason to be reported for nonenrollment were prorated so that the total number of reasons equaled the number of patients not enrolled.

Results

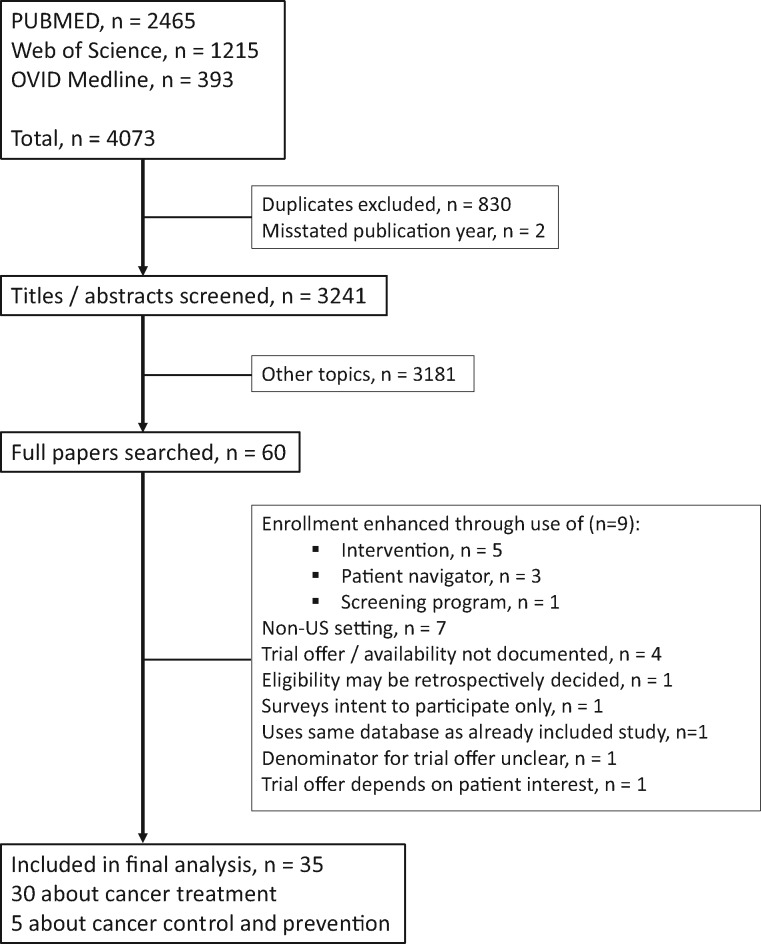

Overall, 4073 studies were flagged by the 3 search engines. Of the studies, 830 studies were duplicates, and 2 studies had mischaracterized publication years that fell outside the prespecified time interval for study inclusion; these records were excluded, leaving 3241 unique studies (Figure 1). Title and abstract review of the 3241 studies yielded 60 potentially relating to participation decision-making for cancer clinical trials. Full articles for these 60 studies were reviewed. Twenty-five were excluded, primarily because the studies included interventions to increase clinical trial accrual or were conducted in a non-US setting (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 2, available online). Thirty-five studies comprised of 9759 patients met our inclusion criteria (Figure 2) (8,9,30–62). Most studies (n = 30, 85.7%) focused on treatment for cancer (Table 1) (8,9,30–32,34,35,37,39,40,42–55,57–62). Among the 5 cancer control studies, 4 focused on enrollment to cancer survivorship studies and 1 to a symptom management study (Table 2) (33,36,38,41,56). Twenty-five studies (71.4%) were conducted in academic care settings, 8 (22.9%) in community care settings, and 2 (5.7%) in both academic and community care settings. A plurality of studies (15 of 35, 42.9%) included patients with all types of cancers; the remaining focused on breast only (8, 22.9%), 1 or more gynecologic cancers (3, 8.6%), lung (3, 8.6%), and others (6, 17.1%). Most studies (33, 94.3%) included all stages of disease. Most studies had a waiver of patient consent (22 of 35, 62.9%). The trial decision outcome was reported by patients for 4 studies (11.4%). Approximately half the studies were prospective (17 of 35, 48.6) and the remaining retrospective. The known recruitment period across the 35 studies spanned 25 years (1993-2017, inclusive).

Figure 1.

Selection of studies included in the analysis

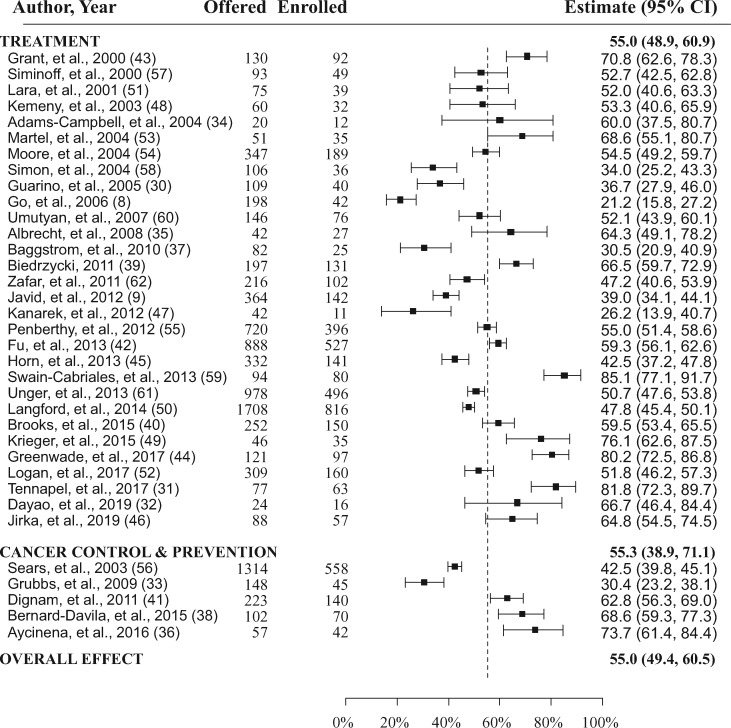

Figure 2.

Forest plots of the study-level and summary estimates for each domain. The boxes show the study-level estimate and the 95% confidence intervals. The overall effect is a summary measure for all trials combined. This is indicated by the dashed vertical line. CI = confidence interval.

Table 1.

Included study characteristics for treatment trials

| Lead author, year Academic vs community setting |

Study design/patient report vs physician report or MR reviewa | Patient consent required? | Cancer type | Other restrictions | Recruitment period, y | Site description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grant et al., 2000 (43) Academic |

Retrospective/Patient | Yesb | All types | Patients considered to have “serious” disease | Not reported | Regional cancer hospital with academic affiliation |

|

Siminoff et al., 2000 (57) Community |

Retrospective/Physician | No | Breast | None listed | 1993-1995 | Physicians in a metropolitan region of Pennsylvania |

|

Lara et al., 2001 (51) Academic |

Prospective/Physician | No | All types | None listed | 1997-2000 | UC Davis Cancer Center |

|

Kemeny et al., 2003 (48) Academic |

Retrospective/MR Review | Yes | Breast | Treated within 2 years of start of this study | Not reported | 10 CALGB sites |

|

Adams-Campbell et al., 2004 (34) Community |

Prospective/Physician | No | All types | African American patients only | 2001-2002 | Howard University Hospital and Cancer Center |

| Prospective/Physician | No | All types | New patients | 2002-2002 | UC Davis Cancer Center | |

|

Moore et al., 2004 (54) Academic |

Prospective/MR Review | Yes | Gynecologic | Primary, previously untreated epithelial ovarian cancer | 1993-1996 | GOG Member Institutions |

|

Simon et al., 2004 (58) Academic |

Prospective/Physician | No | Breast | Newly evaluated | 1996-1997 | Karmanos Cancer Institute |

|

Guarino et al., 2005 (30) Community |

Prospective/Physician | No | All types | None listed | 2004-2004 | Physician practice |

| Prospective/Physician | No | All types | New cancer | 2003-2004 | Gundersen Lutheran Cancer Center | |

| Prospective/Physician | No | All types | None listed | 2004 | UC Davis Cancer Center | |

| Prospective/Physician | Yes | All types | Age 18 years or older; able to speak and read English; visiting participating physician | 2002-2006 | Two NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers | |

|

Baggstrom et al., 2011 (37) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | Lung | None listed | 2006 | Alvin J Siteman Cancer Center |

|

Biedrzycki, 2011 (39) Academic |

Retrospective/Patient | Yes | Gastrointestinalh | Age 18 years or older; able to read English | Not reported | Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center |

|

Zafar et al., 2011 (62) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | All types | Age 65 or older; patient presented to phase I clinical trials service | 1995-2005 | Karmanos Cancer Institute |

|

Javid et al., 2012 (9) Both |

Prospective/Physician | Yes | Breast | New patients or new diagnosis; age older than 18 years; able to read and write English | 2004-2008 | 8 SWOG sites |

|

Kanarek et al., 2012 (47) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | Prostate | Patients seen for first visit | 2010 | Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center |

|

Penberthy et al., 2012 (55) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | All types | Age 21 years or older; African American or White patients only | 2006-2010 | VCU Massey Cancer Center |

|

Fu et al., 2013 (42) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | All types | Referred to phase I clinical trials program | 2011-2012 | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

|

Horn et al., 2013 (45) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | Lung | New patients | 2005-2008 | Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center |

|

Swain-Cabriales et al., 2013 (59) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | Breast | Histologically confirmed breast cancer | 2009 | City of Hope Medical Center |

|

Unger et al., 2013 (61) Community |

Retrospective/Patient | Yes | Breast, lung, prostate, colorectal | Age 18 years or older; living in the United States; first diagnosis | 2007-2011 | Internet-based survey (across United States) |

|

Langford et al., 2014 (50) Community |

Prospective/Physician | No | All types | None listed | 2009-2012 | Community cancer centers (NCCCP sites) |

|

Brooks et al., 2015 (40) Academic |

Prospective/Physician | Yes | Cervix, uterus | Newly diagnosed primary or recurrent | 2010-2012 | Multiple GOG institutions |

|

Krieger et al., 2015 (49) Both |

Retrospective/Patient | Yesg | All types | Living or treated in 1 of 32 rural Appalachian counties | Not reported | Multiple |

|

Greenwade et al., 2017 (44) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | Ovarianh | Patients presenting with epithelial ovarian cancer | 2009-2013 | University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center |

|

Logan et al., 2017 (52) Academic |

Prospective/Physician | No | Lung, esophageal | Eligible for radiation-therapy based RCTs | 2011-2015 | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

|

Tennapel et al., 2017 (31) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | All types | Patients presenting for radiation therapy | 2016 | University of Kansas School of Medicine |

|

Dayao et al., 2019 (32) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | Breast | All breast cancer patients | 2014 | University of New Mexico |

|

Jirka et al., 2019 (46) Academic |

Retrospective/MR review | No | Glioma | Age 18 years or older; have decision-making capacity | 2010-2017 | University of Nebraska Medical Center |

Based on who reported the determination of trial participation. The “physician” category also includes clinic staff. CALGB = Cancer and Leukemia Group B; GOG = Gynecologic Oncology Group; MR = medical record; NCCCP = National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program; NCI = National Cancer Institute; NSCLC = non–small cell lung cancer; UC = University of California

The manuscript indicates that potential respondents were telephoned by the principal investigator; no explicit indication of trial offer.

The study evaluated the impact of the state-level policy change requiring insurance coverage of cancer clinical trial costs in California, but no patient-level intervention was included.

Pilot intervention of a clinical trial reminder tool for physicians but no patient-level trial participation intervention.

Tested the impact of a mass marketing campaign, which had no effect and was not patient specific.

Prospective study of patient–physician communication. No intervention aimed at increasing enrollment to trials.

Defined as “agreed to participate.”

Stages II-IV only.

Table 2.

Included study characteristics for nontreatment trials

| Lead author, year Academic vs community |

Type of nontreatment study | Study design | Patient consent? | Cancer type | Other restrictions | Recruitment period | Site description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sears et al., 2003 (56) Academic |

Survivorship | Prospectivea/Physician | Yes | Breast | Early stage breast cancer, psychoeducational survivorship intervention | 1999-2001 | UCLA, University of Kansas, Georgetown University |

|

Grubbs et al., 2009 (33) Community |

Cancer control | Retrospective/MR review | No | Leukemia | Patients with CLL | 2008 | Multiple NCCCP sites |

|

Dignan et al., 2011 (41) Community |

Survivorship | Prospective/Physician | Yes | All types | Cancer survivors of any hematologic or solid tumor | 2007-2009 | Large public hospital in Birmingham, AL |

|

Bernard-Davila et al., 2015 (38) Academic |

Survivorship | Prospective/Physician | Yes | Breast | Stage 0-III; Hispanic, urban, Spanish-speaking | 2012 | Columbia University |

|

Aycinena et al., 2017 (36) Academic |

Survivorship | Prospective/Physician | Yes | Breast | Stage 0-III; low-income, urban, Hispanic and AA survivors; overweight | 2007-2008 | Columbia University |

Includes survivorship intervention but observational (ie, no intervention) with respect to participating in a survivorship trial. AA = African American; MR = medical record; CLL = chronic lymphocytic leukemia; NCCCP = National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program; UCLA = University of California, Los Angeles.

From 3 studies, 47 patients were identified as not enrolling because of death; these patients were excluded from the study-specific denominators (Figure 2) (41,42,51). Additional exclusions from the study-specified base case denominators of patients offered trial participation included 87 patients from 2 studies who did not participate because of physician barriers (8,55); 39 patients from 3 studies because of ineligibility (39,42,44); 14 from 1 study because of lack of trial availability (44); and 4 patients from 2 studies because of missing enrollment data (39,48). One study excluded 7 patients who were offered a trial but could not be recontacted; these patients were considered passive refusers and were added to the study-specific denominator for purposes of this analysis (35).

Overall Rate of Agreement to Participate

Study-specific estimates are shown in their entirety in Figure 2. Both the estimated Q (512.4, P < .001) and the I2 (96.4%) statistics indicated a high degree of heterogeneity across the studies, justifying the use of a random effects model. The overall rate of participation in either treatment or cancer control trials among patients offered participation was 55.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 49.4% to 60.5%; Figure 2).

There were no statistically significant differences in trial participation rates between studies about trial participation that required patient consent (59.9%, 95% CI = 51.0% to 68.5%) compared with studies not requiring patient consent (52.0%, 95% CI = 45.0% to 59.0%; P = .17). Thus, analyses were not reported separately by this variable.

Trial participation rates were statistically significantly higher at academic centers (58.4%, 95% CI = 52.2% to 64.5%) vs community centers (45.0%, 95% CI = 34.5% to 55.7%; P = .04). In contrast, there were no differences in trial participation rates between studies with prospective (51.7%, 95% CI = 43.8% to 59.6%) vs retrospective (58.1%, 95% CI = 50.4% to 65.6%; P = .26) designs or between studies based on patient report (65.7%, 95% CI = 49.8% to 80.0%) vs physician or staff report (53.6%, 95% CI = 47.7% to 59.4%; P = .16) of trial participation status.

Rates of Agreement to Participate in Treatment Trials

Among the 30 studies about patient participation in treatment trials (comprised of n = 7915 patients), the rate at which patients participated if a trial was offered was 55.0% (95% CI = 48.9% to 60.9%). The rate of trial participation was marginally statistically significantly higher in patients receiving care at academic centers (58.1%, 95% CI = 51.5% to 64.6%) compared with community centers (44.5%, 95% CI = 32.4% to 56.8%; P = .06).

Rates of Agreement to Participate in Cancer Control Studies

Among the 5 studies about patient participation in cancer control studies (comprised of n = 1844 patients), the overall rate was 55.3% (95% CI = 38.9% to 71.1%). The rate of trial participation trended higher in patients participating in cancer control studies at academic centers (61.3%, 95% CI = 39.0% to 81.4%) compared with community centers (46.5%, 95% CI = 21.1% to 72.9%), although this difference was not statistically significant (P = .41).

The participation rates for treatment trials and cancer control studies were not statistically significantly different (P = .98).

Rates of Agreement to Participate in Trials by Race and Ethnicity

In the 15 studies that provided data to estimate rates among Black patients offered trial participation (Table 3), Black patients agreed to participate 60.4% of the time (95% CI = 49.5% to 70.8%; Table 4). In the 13 studies that contained data on agreement to participate for both Black and White patients, Black patient participation was slightly higher (58.4%, 95% CI = 46.8% to 69.7%) than White patient participation (55.1%, 95% CI = 44.3% to 65.6%), although the odds of trial participation did not statistically significantly differ between Black vs White patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.90 to 1.13; P = .88). Results were similar in studies about treatment trial participation only (Table 4).

Table 3.

Study enrollment data, overall and by race and ethnicity, and known reasons for not enrolling in a trial

| Lead author, year | Overall data |

Data by race and ethnicity |

Known reasons for not enrolling in trial |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offered | Enrolled | Not enrolled | Enrolled |

Not enrolled |

No. | Intervention-related reasonsa | Travel | Financial/ insurance |

Fear of experiment or randomization |

Fear of toxicity | Family reasons | Burden | Trust | LTFUb | Supportive care or hospice | Not interested |

Other | |||||||||

| W | B | H | A | O | W | B | H | A | O | |||||||||||||||||

| Studies about treatment trial participation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grant et al., 2000 (43) | 130 | 92 | 38 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Siminoff et al., 2000 (57) | 93 | 49 | 44 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Lara et al., 2001 (51)c | 75 | 39 | 36 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 32 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Kemeny et al., 2003 (48)d | 60 | 32 | 28 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 28 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adams-Campbell et al., 2004 (34) | 20 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Martel et al., 2004 (53)d | 51 | 35 | 16 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 15 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Moore et al., 2004 (54)e | 347 | 189 | 158 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Simon et al., 2004 (58) | 106 | 36 | 70 | 27 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 49 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 56 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Guarino et al., 2005 (30) | 109 | 40 | 69 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Go et al., 2006 (8)f | 198 | 42 | 156 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 156 | 56 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 26 | 2 |

| Umutyan et al., 2008 (60)d,g | 146 | 76 | 70 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 24 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

| Albrecht et al., 2008 (35)h | 42 | 27 | 15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Baggstrom et al., 2011 (37) | 82 | 25 | 57 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 39 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 57 | 0 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 16 | 14 |

| Biedrzycki, 2011 (39) | 197 | 131 | 66 | 115 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Zafar et al., 2011 (62) | 216 | 102 | 114 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Javid et al., 2012 (9)d | 364 | 142 | 222 | 125 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 203 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 159 | 24 | 16 | 11 | 30 | 24 | 15 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

| Kanarek et al., 2012 (47) | 42 | 11 | 31 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 31 | 4 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Penberthy et al., 2012 (55)i | 720 | 396 | 324 | 288 | 108 | — | — | — | 200 | 124 | — | — | — | 282 | 77 | 0 | 61 | 26 | 30 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 59 | 0 |

| Fu et al., 2013 (42)j,k | 888 | 527 | 361 | 387 | 61 | 56 | 0 | 23 | 286 | 24 | 36 | 0 | 15 | 361 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 155 | 47 | 26 | 111 |

| Horn et al., 2013 (45)l | 332 | 141 | 191 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Swain-Cabriales et al., 2013 (59)k,m | 94 | 80 | 14 | 37 | 6 | 25 | 12 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Unger et al., 2013 (61)d,n | 978 | 496 | 482 | 465 | 15 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 452 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 482 | 78 | 32 | 32 | 98 | 76 | 36 | 45 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 72 |

| Brooks et al., 2015 (40) | 252 | 150 | 102 | 107 | 24 | 0 | 11 | 8 | 94 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Langford et al., 2014 (50)d,o | 1708 | 816 | 892 | 663 | 94 | 35 | 17 | 7 | 713 | 112 | 32 | 23 | 12 | 892 | 330 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 73 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 33 | 366 | 38 |

| Krieger et al., 2015 (49) | 46 | 35 | 11 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Greenwade et al., 2017 (44)k,p | 121 | 97 | 24 | 88 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 5 |

| Logan et al., 2017 (52) | 309 | 160 | 149 | 139 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 130 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tennapel et al., 2017 (31) | 77 | 63 | 14 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Dayao et al., 2019 (32) | 24 | 16 | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Jirka et al., 2019 (46) | 88 | 57 | 31 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 31 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 5 |

| Studies about cancer control study participation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sears et al., 2003 (56) | 1314 | 558 | 756 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 756 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 65 | 0 | 426 | 16 | 108 | 61 |

| Grubbs et al., 2009 (33) | 148 | 45 | 103 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 92 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 72 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dignan et al., 2011 (41) | 223 | 140 | 83 | 29q | 111 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| Bernard-Davila et al., 2015 (38)r | 102 | 70 | 32 | 28 | 18 | 22 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| Aycinena et al., 2017 (36) | 57 | 42 | 15 | 0 | 9 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Treatment-related reasons variously framed as desire for other treatment, wish to choose own treatment, desire to avoid protocol treatment, fear of protocol treatment, and preference for standard therapy. “—” indicates data not provided. A = Asian; B = Black; H = Hispanic; LTFU = lost to follow-up; O = other/unknown; W = White.

Also includes “did not return” and “second opinions.”

One patient who was offered a trial did not participate because of death. This patient was excluded from the study denominator.

Reasons for nonenrollment were provided for a subset (n = 159) of patients. Because patients may have indicated >1 reason, category counts were prorated relative to the denominator of number of responses.

801 analyzable patients; 189 enrolled on the Gyncologic Oncology Group study; among remaining 612 patients (Table 4), exclude investigator decision (121), no available GOG protocol (170), and ineligible (163), leaving 158 nonenrolled patients.

Excluded from the denominator of patients offered a trial are those who did not enroll because of physician decision (Figure 1).

Included data from both the premass marketing campaign and the postmass marketing campaign groups. Data on reasons for nonparticipation only available for the postmass marketing group (n = 33).

tConsistent with other studies, we included in the denominator the 7 patients reported as lost to follow-up, as these were considered passive refusers.

Excludes 22 patients who indicated they did not participate because of physician barrier.

Excludes 26 patients who did not enroll because of ineligibility, and 43 patients who did not enroll because of death.

Proportion by race recalculated to be proportional to adjusted rate of patients not enrolled. Cell counts may not sum to the number not enrolled because of rounding.

Reasons for nonenrollment were provided, but category levels were very broad and could not be reconciled with existing category descriptions.

Among the 58 patients who did not enroll, 44 were excluded because their physician did not offer trial participation.

Counts by race obtained by the study team (Unger, JM; personnel communication).

Reasons for nonenrolled derived from St Germaine, 2014.

In total, 47 were not enrolled, but those with trial unavailable (14), ineligible (8), and unable to enroll because of paclitaxel shortage (1) were excluded because these were not patient choice factors, leaving n = 24 not enrolled.

Categorized as “White/other.”

Race reported separately from ethnicity. All patients were Hispanic ethnicity.

Table 4.

Rates of agreement to participate if offered a trial by race and ethnicity

| Comparison group | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | ||||

| No. of studies | 16 | 15 | 8 | 6 |

| Rate, % (95% CI) | 56.0 (47.3 to 64.5) | 60.4 (49.5 to 70.8) | 67.1 (57.4 to 76.2) | 63.6% (39.2 to 85.3) |

| By study setting | ||||

| Treatment, % (95% CI) | 53.4 (44.8 to 61.9) | 57.6 (45.1 to 69.6) | 64.9 (52.9 to 76.1) | 61.7 (34.7 to 85.9) |

| Cancer control, % (95% CI) | 75.9 (52.5 to 93.2) | 70.4 (47.1 to 89.6) | 72.5 (54.4 to 87.8) | 79.8 (7.7 to 100) |

| P | .08 | .33 | .48 | .65 |

| By care setting | ||||

| Academic, % (95% CI) | 56.1 (45.7 to 66.2) | 63.8 (49.9 to 76.8) | 72.1 (62.6 to 80.8) | 86.8 (70.3 to 98.1) |

| Community, % (95% CI) | 55.9 (36.1 to 74.7) | 54.2 (35.2 to 72.7) | 53.8 (38.9 to 68.4) | 37.4 (23.3 to 52.4) |

| P | .98 | .43 | .04 | <.001 |

| Compared to White patientsa | ||||

| All studies | ||||

| No. of studies | — | 13 | 7 | 6 |

| Rate, % (95% CI) | — | 58.4 (46.8 to 69.7) | 66.7 (55.1 to 77.4) | 63.6 (39.2 to 85.3) |

| Rate in White patients, % (95% CI) | — | 55.1 (44.3 to 65.6) | 61.2 (47.8 to 73.8) | 56.9 (43.4 to 70.0) |

| OR (95% CI) | — | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.13) | 1.05 (0.92 to 1.20) | 1.06 (0.84 to 1.34) |

| P | — | .88 | .48 | .62 |

| By study setting | ||||

| Treatment trials only | ||||

| No. of studies | — | 11 | 6 | 5 |

| Rate, % (95% CI) | — | 57.6 (43.2 to 71.5) | 65.4 (51.9 to 77.9) | 61.1 (35.6 to 84.1) |

| Rate in White patients, % (95% CI) | — | 51.5 (40.4 to 62.6) | 59.7 (44.6 to 73.9) | 54.4 (39.6 to 68.7) |

| OR (95% CI) | — | 1.04 (0.91 to 1.19) | 1.05 (0.92 to 1.20) | 1.06 (0.84 to 1.34) |

| P | — | .56 | .48 | .62 |

Estimated among studies with data on participation rates for both White patients and minority group of interest. “—” indicates no analysis conducted, because the comparison group is White patients. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Similar patterns of higher, but non-statistically significant, rates of participation were evident for Hispanic patients and Asian patients compared with White patients (Table 4). For each of Black, Hispanic, and Asian patient groups, rates of participation trended higher at academic compared with community centers; differences were statistically significant among Hispanic patients (P = .04) and especially among Asian patients (P < .001).

Reasons for Nonenrollment

Half (15 of 30) of the studies about treatment trial participation—comprising 2626 patients—provided reasons for nonenrollment (Table 3). Treatment-related concerns were most commonly indicated as reasons for nonenrollment, variously described as desire for other treatment, desire to choose own treatment or to avoid protocol treatment, or preference for standard treatment (24.4%). A large portion of patients indicated they were not interested in trial participation (19.9%). Passive refusal to participate—expressed through not returning to the clinic or being lost to follow-up—was the reason 8.3% of patients did not enroll. Other common reasons included fear of side effects (7.9%), financial concerns or insurance denial (6.7%), and a dislike of participating in an experiment, including dislike of having treatment determined by random assignment (6.6%).

All 5 cancer studies about participation in cancer control trials provided known reasons for nonparticipation on 959 patients (Table 3). Not returning to the clinic or being lost to follow-up was the reason nearly half (49.4%) of patients did not participate. Other common reasons for nonenrollment included a dislike of participating in an experiment (12.6%) and lack of interest (11.9%). Travel distance was indicated as a reason for nonenrollment for 4.2% of patients considering a treatment trial and 5.4% of patients considering a cancer control trial.

Additional Analyses

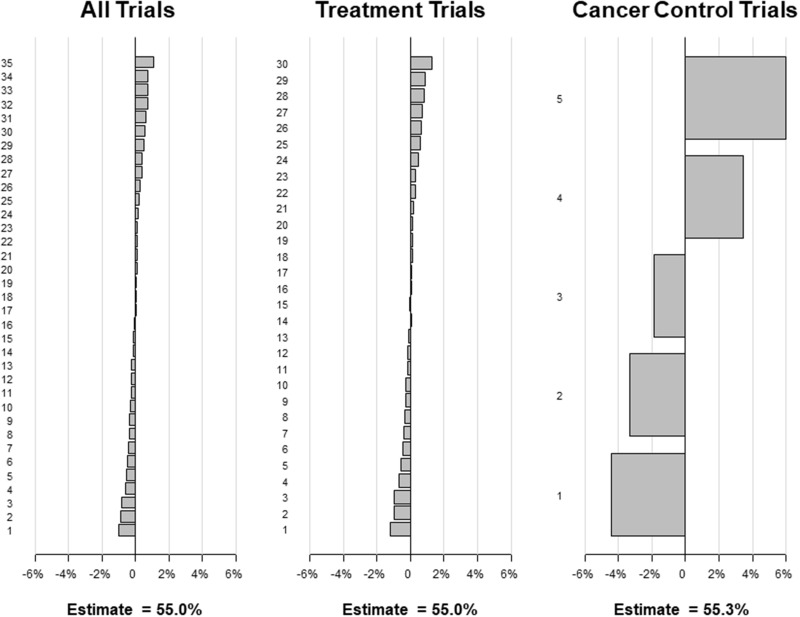

When individual studies were iteratively excluded, in no case did the percentage estimate change by more than 1.2% for all studies combined (primary estimate, 55.0%; range = 54.0%-56.1%) and for the treatment studies (primary estimate, 55.0%; range = 53.8%-56.2%; Figure 3). Given fewer available studies, the exclusion of individual cancer control studies resulted in percentage estimate change of up to 6.0% for the overall cancer control estimate (primary estimate, 55.3%; range = 50.9%-61.3%). This analysis indicates that the estimates for all studies combined, treatment trials, and cancer control studies are internally robust.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis results for the “leave one out” method. Under this approach, each of the individual studies is left out of the calculation of the meta-analytic rate one at a time, and the rate is recalculated using the random-effects approach. Each panel shows the absolute percentage increase or decrease in the overall estimated rate for all trials, for treatment trials, and for cancer control trials, respectively. The primary estimates are also shown. The results are ordered in descending order from largest absolute positive percentage change to largest absolute negative percentage change.

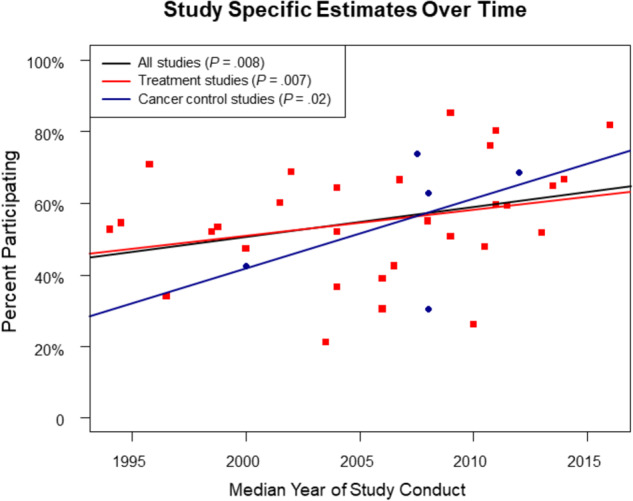

An examination of study-specific estimates suggests that rates of agreement to participate in trials have trended higher in more recent years (Figure 4) for all studies combined (P = .008), treatment trials (P = .007), and cancer control studies (P = .02). The rate of participation was greater among studies with median enrollment year after 2010 (65.5%, 95% CI = 56.0% to 74.4%) vs 2010 or before (50.7%, 95% CI = 44.5% to 56.8%; P = .01).

Figure 4.

Study specific estimates over time

In a sensitivity analysis examining the potential impact of study assumptions, the potential lower bound on the estimated rate of trial participation was 53.4% (95% CI = 48.2% to 58.7%), and the potential upper bound was 57.8% (95% CI = 52.1% to 63.3%). We found no evidence of publication bias using the rank correlation test (P = .24).

Discussion

We found that at least half of patients offered participation in a cancer clinical trial did participate. The findings did not differ between treatment and cancer control trials. Importantly, Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients participated in trials at rates at least as high as White patients. Moreover, the rate of trial participation among those offered a trial may have increased over time. These findings dramatically underscore the willingness of cancer patients to participate in a trial if one is offered. The findings also stand in stark contrast to the commonly cited statistic that only 5% of adult cancer patients participate in trials, a statistic that fails to reflect the many structural and clinical hurdles that stand in the way of trial participation for most patients.

Because patients ultimately decide whether to participate in a trial, it is critical to understand why they choose to participate or not. In the studies included in this analysis, the most common reason for not enrolling in a treatment trial was the desire among patients to control their treatment choice, including by avoiding protocol treatment side effects and by avoiding participation in an experiment where treatment may be randomly assigned. Many patients also explicitly (to researchers) or implicitly (through passive refusal, eg, by not following up) expressed a lack of interest in trial participation. Together, these reasons underlay the decision for nearly 7 out of every 10 (69.0%) patients who chose not to participate in either treatment or cancer control studies.

An important consideration for researchers and policy makers is understanding the extent to which reasons for nonparticipation in trials are modifiable, as such reasons may be amenable to interventions or policy changes. A patient’s desire to control his or her treatment choice or a lack of interest in study participation are unlikely to be easily modifiable; moreover, attempting to do so may tread on the patient protections against undue influence articulated in the US Common Rule for the Protection of Human Subjects. In contrast, other (although less frequent) reasons expressed by patients for nonparticipation may in fact be explicitly addressable through policy. For instance, some patients indicated concerns about finances or insurance. Medicare covers the routine care costs of clinical trial participation, as do many private insurance carriers. State Medicaid programs, in contrast, do not uniformly provide coverage for clinical trials, and coverage provisions in general are highly variable (63,64). To address this, legislation currently before Congress would mandate that all state Medicaid programs cover the routine care costs of cancer clinical trials (65). Patients also cited the burden of travel as a barrier. Travel distance may be especially problematic for socioeconomically and geographically disadvantaged populations lacking more proximal access to academic cancer centers where trial conduct is more common (66–68). Health-care models that virtually link local providers with oncology specialists could help alleviate the need for cancer patients to travel great distances for care (69). The recently accelerated adoption of telemedicine approaches (including remote consent and virtual visits) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic can ease the burden of trial participation for cancer patients and, if made permanent, may improve access to trials for patients over the long term (70–72). More broadly, external advisory groups, especially that include patient advocates, could help researchers design trials that more readily incorporate elements to make trial participation more attractive to patients (73,74).

These concrete steps to improve access to trials for those offered participation are necessary. But only a small portion of patients are offered trial participation, so even very successful strategies will have only limited impact on overall trial participation rates. A much greater impact may be achieved by addressing the numerous and sizeable hurdles to trial participation that occur prior to the physician–patient interaction. Structural barriers to the conduct of trials are endemic in the United States (5). Clinical trial conduct is a major undertaking for institutions, requiring a commitment of resources that are often poorly reimbursed, especially for nonpharmaceutical company–sponsored trials (6). Thus, for the majority of patients, no protocol is locally available (5). In response, government-sponsored trial mechanisms, such as the National Cancer Institute’s Community Oncology Research Program, were designed specifically to enable the conduct of trials outside major academic centers, with notable success in extending the reach and inclusivity of trials (13,75,76). Clinical trial matching services provide clinicians and patients the opportunity to identify clinical trials for which they are potentially eligible. These services have struggled to provide complete and reliable targets, although efforts to standardize and improve these services are ongoing (77).

Even when a trial is available, patients are frequently ineligible. The recognition that trial eligibility criteria are overly restrictive, with limited safety or research benefit, motivated an extensive effort by the American Society for Clinical Oncology, Friends of Cancer Research, and the US Food and Drug Administration to modernize eligibility criteria (7,78). One recent study estimated that adoption of these changes to eligibility could generate more than 6000 new registrations to cancer clinical treatment trials annually (79). Another study estimated that the expanded criteria would double the number of non–small cell lung cancer patients eligible for trial participation (80). Together, these structural and clinical barriers exclude 3 out of every 4 patients. Because many aspects of these barrier domains are potentially modifiable, mitigating these barriers represents an enormous opportunity to increase trial participation rates.

We also found that Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients enrolled at rates that were very comparable to rates for White patients. This observation seems surprising given the repeated observations that minority patients are underrepresented in clinical cancer research (2,12). Yet, the finding is consistent with other studies showing similarity by race in the willingness to participate in trials if asked (81–83). It also strongly suggests that observed racial and ethnic disparities in trial participation manifest earlier in the treatment decision-making process, perhaps because of differential likelihood of meeting restrictive eligibility criteria (55), differential access to cancer centers where clinical research is conducted (84,85), and differential access to physicians who offer clinical trials (58). Indeed, this finding indicates that perhaps the best way to improve enrollment of minority patients to cancer trials is simply to ensure that minority patients are invited to participate. The recognition of this may inform efforts to alleviate potential bias in the provision of health-care resources by race or ethnicity, including trial offers for eligible patients (58,86,87).

One concern about conducting secondary studies about patient agreement to participate in clinical trials is that the process of seeking consent for the secondary study is more likely to bias the samples in favor of patients willing to participate in research more generally, including in clinical trials, which could generate an inflated estimate of the rate of clinical trial participation. Recognizing this, many studies about clinical trial decision-making sought waivers of consent. Regardless, we found no statistically significant difference in trial participation rates between studies that did vs did not require consent. Also, the review was limited by the fact that not all studies provided data on enrollment by race and ethnicity. Additionally, estimates of agreement to participate may be biased high if the number of individuals offered a trial was undercounted, although the limited evidence available to examine this suggested a tendency to overestimate the number of individuals at risk of trial participation by including patients who did not participate because of physician or eligibility barriers or lack of trial availability. Further, there is a possibility that publication bias or missed studies could influence the results. Our anticipation is that the influence of one or more missed studies would likely be nominal given the comprehensive search procedures that included abstracts as well as full articles; the fact that 35 studies were included, such that the inclusion of any single study in a random effects model is unlikely to substantially alter the results; and the existing lack of evidence of publication bias based on the Begg rank correlation test. The evaluation of reasons for nonparticipation was a secondary endpoint and was based on the included studies only, rather than on a comprehensive review of the literature about reasons for nonparticipation. Thus, the estimates derived from this component of the analysis may not have been representative and may also have missed some known reasons for nonparticipation that have been previously identified, such as concerns about the consent process or time and effort to participate in a trial (11,61,88). Finally, only 5 studies examined participation in cancer control studies, limiting confidence in the conclusions that can be drawn about participation patterns in this research setting.

The findings of this review indicate that patients choose to participate in clinical trials more than half the time when offered the opportunity, irrespective of race and ethnicity. This suggests that the root cause of low trial participation rates in adults with cancer is a clinical trial system beset with structural and clinical barriers, rather than patient disinterest. Research, interventions, and policies to improve trial participation should focus more on these systemic structural and clinical barriers.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Hope Foundation for Cancer Research (Unger).

Notes

Role of funder: The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures: The authors report the following relationships or conflicts of interest: Hershman, DL: Consulting or advisory role (AIM Specialty Health). Till, C (an immediate family member): Patents, royalties, other intellectual property (Roche/Genentech; MustangBio). Osarogiagbon, RU: Consulting or advisory role (Association of Community Cancer Centers; AstraZeneca; American Cancer Society); patents, royalties, other intellectual property (2 US and 1 China patents for lymph node specimen collection kit and method of pathologic evaluation); stock and other ownership interests (Lilly; Pfizer; Gilead Sciences); other relationship (Oncobox). Fleury ME: Research Funding (IQvia; Merck; Genentech). No other relationship were reported.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the study sponsor.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Unger, Fleury, Vaidya. Methodology: Unger, Vaidya. Formal Analysis: Unger, Till. Investigation: Unger, Hershman, Till, Minasian, Osarogiagbon, Fleury, Vaidya. Resources: Unger, Hershman. Data Curation: Unger, Till, Vaidya. Writing - Original Draft: Unger. Writing - Review and Editing: Unger, Hershman, Till, Minasian, Osarogiagbon, Fleury, Vaidya. Visualization: Unger, Vaidya. Supervision: Unger, Hershman, Vaidya. Funding acquisition: Unger.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Transforming Clinical Research in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP.. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2720–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, et al. How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(8):2109–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tejeda HA, Green SB, Trimble EL, et al. Representation of African-Americans, Hispanics, and whites in National Cancer Institute cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(12):812–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Unger JM, Vaidya R, Hershman DL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the magnitude of structural, clinical, and physician and patient barriers to cancer clinical trial participation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(3):245–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Minasian LM, Unger JM.. What keeps patients out of clinical trials? J Clin Oncol Pract. 2020;16(3):125–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim ES, Bruinooge SS, Roberts S, et al. Broadening eligibility criteria to make clinical trials more representative: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research Joint Research Statement. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(33):3737–3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Go RS, Frisby KA, Lee JA, et al. Clinical trial accrual among new cancer patients at a community-based cancer center. Cancer. 2006;106(2):426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Javid SH, Unger JM, Gralow JR, et al. A prospective analysis of the influence of older age on physician and patient decision-making when considering enrollment in breast cancer clinical trials (SWOG S0316). Oncologist. 2012;17(9):1180–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. St Germain D, Denicoff AM, Dimond EP, et al. Use of the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program screening and accrual log to address cancer clinical trial accrual. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(2):e73–e80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112(2):228–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Loree JM, Anand S, Dasari A, et al. Disparity of race reporting and representation in clinical trials leading to cancer drug approvals from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(10):e191870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Unger JM, Hershman DL, Osarogiagbon RU, et al. Representativeness of black patients in cancer clinical trials sponsored by the National Cancer Institute compared to pharmaceutical companies. JNCI Cancer Spectrum. 2020;4(4):pkaa034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metaphor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang N. How to conduct a meta-analysis of proportions in r: a comprehensive tutorial. 2018; doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.27199.00161. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, et al. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Method. 2010;1(2):97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brockwell SE, Gordon IR.. A comparison of statistical methods for meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2001;20(6):825–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10(1):101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T.. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(11):974–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. DerSimonian R, Laird N.. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Higgins JP, Thompson SG.. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Langan D, Higgins JPT, Jackson D, et al. A comparison of heterogeneity variance estimators in simulated random-effects meta-analyses. Res Syn Meth. 2019;10(1):83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Viechtbauer W. Bias and efficiency of meta-analytic variance estimators in the random-effects model. J Educ Behav Stat. 2005;30(3):261–293. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR.. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Copur MS, Ramaekers R, Gönen M, et al. Impact of the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program on clinical trial and related activities at a community cancer center in rural Nebraska. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(67-8):e44-e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Petrelli NJ. A community cancer center program: getting to the next level. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(3):261–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pfister DG, Rubin DM, Elkin EB, et al. Risk adjusting survival outcomes in hospitals that treat patients with cancer without information on cancer stage. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(9):1303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Begg CB, Mazumdar M.. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guarino MJ, Masters GA, Schneider CJ, et al. Barriers exist to patient participation in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(suppl 16):6015–6015. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tennapel MJ, Chen AM, Shen X.. Clinical trial accrual patterns for radiation oncology patients at an academically based tertiary care medical center. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;99(2):e418. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dayao Z, Nemunaitis J. Abstract P5-13-06: Analysis of barriers to clinical trial accrual in an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center: Results of identifying clinical trial gaps. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium Proceedings. 2019. ;79(suppl 4):P5-13-06. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grubbs SS, Gonzalez M, Krasna M, et al. Tracking clinical trial accrual strategies and barriers via a Web-based screening tool. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(suppl 15):6586. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adams-Campbell LL, Ahaghotu C, Gaskins M, et al. Enrollment of African Americans onto clinical treatment trials: study design barriers. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(4):730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Albrecht TL, Eggly SS, Gleason ME, et al. Influence of clinical communication on patients’ decision making on participation in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2666–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aycinena AC, Valdovinos C, Crew KD, et al. Barriers to recruitment and adherence in a randomized controlled diet and exercise weight loss intervention among minority breast cancer survivors. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2017;19(1):120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baggstrom MQ, Waqar SN, Sezhiyan AK, et al. Barriers to enrollment in non-small cell lung cancer therapeutic clinical trials. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(1):98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bernard-Davila B, Aycinena AC, Richardson J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to recruitment to a culturally-based dietary intervention among urban Hispanic breast cancer survivors. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(2):244–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Biedrzycki BA. Factors and outcomes of decision making for cancer clinical trial participation. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(5):542–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brooks SE, Carter RL, Plaxe SC, et al. Patient and physician factors associated with participation in cervical and uterine cancer trials: an NRG/GOG247 study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138(1):101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dignan M, Evans M, Kratt P, et al. Recruitment of low income, predominantly minority cancer survivors to a randomized trial of the I Can Cope cancer education program. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(3):912–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fu S, McQuinn L, Naing A, et al. Barriers to study enrollment in patients with advanced cancer referred to a phase I clinical trials unit. Oncologist. 2013;18(12):1315–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grant CH 3rd, Cissna KN, Rosenfeld LB.. Patients’ perceptions of physicians communication and outcomes of the accrual to trial process. Health Commun. 2000;12(1):23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Greenwade MM, Moore KN, Gillen JM, et al. Factors influencing clinical trial enrollment among ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(3):465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Horn L, Keedy VL, Campbell N, et al. Identifying barriers associated with enrollment of patients with lung cancer into clinical trials. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14(1):14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jirka GW, Bisselou KSM, Smith LM, et al. Evaluating the decisions of glioma patients regarding clinical trial participation: a retrospective single provider review. Med Oncol. 2019;36(4):34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kanarek NF, Kanarek MS, Olatoye D, et al. Removing barriers to participation in clinical trials, a conceptual framework and retrospective chart review study. Trials. 2012;13(1):237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kemeny MM, Peterson BL, Kornblith AB, et al. Barriers to clinical trial participation by older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(12):2268–2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krieger JL, Palmer-Wackerly A, Dailey PM, et al. Comprehension of randomization and uncertainty in cancer clinical trials decision making among rural, Appalachian patients. J Canc Educ. 2015;30(4):743–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Langford AT, Resnicow K, Dimond EP, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in clinical trial enrollment, refusal rates, ineligibility, and reasons for decline among patients at sites in the National Cancer Institute’s Community Cancer Centers Program. Cancer. 2014;120(6):877–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lara PN Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(6):1728–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Logan JK, Tang C, Liao Z, et al. Analysis of factors affecting successful clinical trial enrollment in the context of three prospective, randomized, controlled trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97(4):770–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Martel CL, Li Y, Beckett L, et al. An evaluation of barriers to accrual in the era of legislation requiring insurance coverage of cancer clinical trial costs in California. Cancer J. 2004;10(5):294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moore DH, Kauderer JT, Bell J, et al. An assessment of age and other factors influencing protocol versus alternative treatments for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer referred to member institutions: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94(2):368–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Penberthy L, Brown R, Wilson-Genderson M, et al. Barriers to therapeutic clinical trials enrollment: differences between African-American and white cancer patients identified at the time of eligibility assessment. Clin Trials. 2012;9(6):788–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sears SR, Stanton AL, Kwan L, et al. Recruitment and retention challenges in breast cancer survivorship research: results from a multisite, randomized intervention trial in women with early stage breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(10):1087–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Siminoff LA, Zhang A, Colabianchi N, et al. Factors that predict the referral of breast cancer patients onto clinical trials by their surgeons and medical oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(6):1203–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Simon MS, Du W, Flaherty L, et al. Factors associated with breast cancer clinical trials participation and enrollment at a large academic medical center. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(11):2046–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Swain-Cabriales S, Bourdeanu L, Niland J, et al. Enrollment onto breast cancer therapeutic clinical trials: a tertiary cancer center experience. Appl Nurs Res. 2013;26(3):133–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Umutyan A, Chiechi C, Beckett LA, et al. Overcoming barriers to cancer clinical trial accrual: impact of a mass media campaign. Cancer. 2008;112(1):212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Unger JM, Hershman DL, Albain KS, et al. Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(5):536–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zafar SF, Heilbrun LK, Vishnu P, et al. Participation and survival of geriatric patients in phase I clinical trials: the Karmanos Cancer Institute (KCI) experience. J Geriatr Oncol. 2011;2(1):18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Public Citizen Health Research Group. Unsettling scores: a ranking of state Medicaid programs. 2007. https://www.citizen.org/article/unsettling-scores/. Accessed June 6, 2020.

- 64.American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Medicaid: Ensuring Access to affordable health care coverage for lower income cancer patients and survivors. 2020. https://www.fightcancer.org/policy-resources/medicaid-ensuring-access-affordable-health-care-coverage-lower-income-cancer. Accessed June 6, 2020.

- 65.Library of Congress. HR 6836—Clinical Treatment Act. 115th Congress (2017-2018). Congress.gov. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/6836/text. Accessed June 6, 2020.

- 66. Borno HT, Zhang L, Siegel A, et al. At what cost to clinical trial enrollment? A retrospective study of patient travel burden in cancer clinical trials. Oncologist. 2018;23(10):1242–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bristow RE, Chang J, Ziogas A, et al. Spatial analysis of adherence to treatment guidelines for advanced-stage ovarian cancer and the impact of race and socioeconomic status. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134(1):60–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Henley SJ, Anderson RN, Thomas CC, et al. Invasive cancer incidence, 2004-2013, and deaths, 2006-2015, in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties—United States. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(14):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Cassidy J, et al. Systematic review of cancer treatment programmes in remote and rural areas. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(8):1275–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Guidance on conduct of clinical trials of medical products during COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/fda-guidance-conduct-clinical-trials-medical-products-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 71.National Cancer Institute. Coronavirus guidance. 2020. https://ctep.cancer.gov/investigatorResources/corona_virus_guidance.htm. Accessed June 6, 2020.

- 72. Schrag D, Hershman DL, Basch E.. Oncology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A.. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(2):133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ramsey SD, Barlow WE, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Integrating comparative effectiveness design elements and endpoints into a phase III, randomized clinical trial (SWOG S1007) evaluating oncotypeDX-guided management for women with breast cancer involving lymph nodes. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Unger JM, Moseley A, Symington B, et al. Geographic distribution and survival outcomes for rural patients with cancer treated in clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.National Cancer Institute. Community Oncology Research Program. https://ncorp.cancer.gov/about/. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- 77.American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Letter to Dr. Normal E. Sharpless, Director, National Cancer Institute. Re: NCI Request for Information, Strategies for Matching Patients to Clinical Trials (NOT-CA-18-063). 2018. https://www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/ACS%20CAN%20Comments%20on%20NCI%20RFI%20%20NOT-CA-18-063%2006.15.2018%20-%20FINAL_0.pdf. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- 78.American Society of Clinical Oncology. ASCO in Action: initiative to modernize eligibility criteria for clinical trials launched. 2016. https://www.asco.org/practice-policy/policy-issues-statements/asco-in-action/initiative-modernize-eligibility-criteria. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- 79. Unger JM, Hershman DL, Fleury ME, et al. Association of patient comorbid conditions with cancer clinical trial participation. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(3):326–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Harvey RD, Rubinstein WS, Ison G, et al. Impact of broadening clinical trial eligibility criteria for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients: real-world analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(suppl 18). https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.18_suppl.LBA108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Byrne MM, Tannenbaum SL, Glück S, et al. Participation in cancer clinical trials: why are patients not participating? Med Decis Making. 2014;34(1):116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Gross CP, Filardo G, Mayne ST, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status and race on trial participation for older women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2005;103(3):483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2005;3(2):e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kanarek NF, Tsai HL, Metzger-Gaud S, et al. Geographic proximity and racial disparities in cancer clinical trial participation. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(12):1343–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Shavers VL, Brown ML.. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(5):334–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hamel LM, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, et al. Barriers to clinical trial enrollment in racial and ethnic minority patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2016;23(4):327–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Gotay CC. Accrual to cancer clinical trials: directions from the research literature. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(5):569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online Supplementary Material.