Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic changed expectations for information dissemination and use around the globe, challenging accepted models of communications, leadership, and social systems. We explore how social media discourse about COVID-19 in Italy was affected by the rapid spread of the virus, and how themes in postings changed with the adoption of social distancing measures and non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI). We used topic modeling and social network analysis to highlight critical dimensions of conversations around COVID-19: 1) topics in social media postings about the Coronavirus; 2) the scope and reach of social networks; and 3) changes in social media content as the nation moved from partial to full social distancing. Twitter messages sent in Italy between February 11th and March 10th, 2020. 74,306 Tweets sent by institutions, news sources, elected officials, scientists and social media influencers. Messages were retweeted more than 1.2 million times globally. Non-parametric chi-square statistic with residual analysis to identify categories, chi-square test for linear trend, and Social Network Graphing. The first phase of the pandemic was dominated by social media influencers, followed by a focus on the economic consequences of the virus and placing blame on immigrants. As the crisis deepened, science-based themes began to predominate, with a focus on reducing the spread of the virus through physical distancing and business closures Our findings highlight the importance of messaging in social media in gaining the public’s trust and engagement during a pandemic. This requires credible scientific voices to garner public support for effective mitigation. Fighting the spread of an infectious disease goes hand in hand with stemming the dissemination of lies, bad science, and misdirection.

Keywords: Covid-19, Twitter, Non-pharmacological interventions, Social media, Communication

Introduction

Since it emerged as a global threat in early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected health, human functioning and society on an unprecedented scale. The global spread of the virus in the absence of vaccines and effective treatments demonstrates the importance of effectively using non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) such as social distancing to reduce transmission of the virus, limit mortality and avoid overwhelming local healthcare systems [1]. Two strategies were used in most nations: quarantine of infected persons and social distancing to mitigate the spread of the virus [2–5]. Effective implementation of containment and social distancing strategies requires social trust, given the threat of massive disruption to society and the economy [6].

In response to the rapid spread of COVID-19, many nations mandated all but essential businesses to be shuttered and for individuals to “shelter in place” to reduce the risk of transmission of the highly contagious virus. In Italy, as one of the first countries to be severely hit by the wave, the “#I-stay-home” campaign obliged citizens to avoid leaving their homes. This effort and similar programs in other nations require trust and public consensus, to engage a nation’s citizens as active co-participants in their own and their fellow citizen’s health and well-being [7].

At the time of submission, almost 3 million cases of infection and nearly 100,000 COVID-19 related deaths had occurred in Italy. The effectiveness of measures such as social distancing to reduce the spread of the virus depends on the level of social trust and collection societal action that is supported by integration among the key groups such as citizens, institutions, information providers and elected officials [8]. Artificial dichotomies between the need to contain the spread of the virus and the need to maintain the health of the economy, conflicting themes in public and social media, and lack of a unified message can undermine the citizen buy-in, social trust, public compliance, and the speed and effectiveness of implementation.

Social trust and precise messaging are key in the current efforts to address an unprecedented challenge to the healthcare systems of nations. They are needed to inform public perceptions and contribute to a developing regional or national consensus that helps leaders and policymakers to coordinate transparent and consensus-based efforts to adopt of country-wide social distancing measures such as closing schools, banning mass gatherings, and isolating individuals with the virus and their contacts. These efforts were shown to be effective in containing the spread of the Spanish Flu in 1918 [9].

In this paper, we explore the content and messages in social media communications during the early stages of the spread of the COVID-19 virus in Italy, which numbers are reported in Appendix 1 (Table 4). The aim is to better understand how social media dialogue can affect and be used strategically in the adoption of large-scale regional and national social distancing measures to prevent the spread of the virus.

Table 4.

Daily progression of the disease in Italy

| Date | Country | Hospitalization (not in ICU) | ICU occupation | Total Hospitalized | Self-isolated | People Tested Positive (total) | People Tested Positive (per day) | People recovered | Number of deaths | Total cases | People tested (total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2/24/2020 | ITA | 101 | 26 | 127 | 94 | 221 | 221 | 1 | 7 | 229 | 4324 |

| 2/25/2020 | ITA | 114 | 35 | 150 | 162 | 311 | 90 | 1 | 10 | 322 | 8623 |

| 2/26/2020 | ITA | 128 | 36 | 164 | 221 | 385 | 74 | 3 | 12 | 400 | 9587 |

| 2/27/2020 | ITA | 248 | 56 | 304 | 284 | 588 | 203 | 45 | 17 | 650 | 12,014 |

| 2/28/2020 | ITA | 345 | 64 | 409 | 412 | 821 | 233 | 46 | 21 | 888 | 15,695 |

| 2/29/2020 | ITA | 401 | 105 | 506 | 543 | 1049 | 228 | 50 | 29 | 1128 | 18,661 |

| 3/1/2020 | ITA | 639 | 140 | 779 | 798 | 1577 | 528 | 83 | 34 | 1694 | 21,127 |

| 3/2/2020 | ITA | 742 | 166 | 908 | 927 | 1835 | 258 | 149 | 52 | 2036 | 23,345 |

| 3/3/2020 | ITA | 1034 | 229 | 1263 | 1000 | 2263 | 428 | 160 | 79 | 2502 | 25,856 |

| 3/4/2020 | ITA | 1346 | 295 | 1641 | 1065 | 2706 | 443 | 276 | 107 | 3089 | 29,837 |

| 3/5/2020 | ITA | 1790 | 351 | 2141 | 1155 | 3296 | 590 | 414 | 148 | 3858 | 32,362 |

| 3/6/2020 | ITA | 2394 | 462 | 2856 | 1060 | 3916 | 620 | 523 | 197 | 4636 | 36,359 |

| 3/7/2020 | ITA | 2651 | 567 | 3218 | 1843 | 5061 | 1145 | 589 | 233 | 5883 | 42,062 |

| 3/8/2020 | ITA | 3557 | 650 | 4207 | 2180 | 6387 | 1326 | 622 | 366 | 7375 | 49,937 |

| 3/9/2020 | ITA | 4316 | 733 | 5049 | 2936 | 7985 | 1598 | 724 | 463 | 9172 | 53,826 |

| 3/10/2020 | ITA | 5038 | 877 | 5915 | 2599 | 8514 | 529 | 1004 | 631 | 10,149 | 60,761 |

| 3/11/2020 | ITA | 5838 | 1028 | 6866 | 3724 | 10,590 | 2076 | 1045 | 827 | 12,462 | 73,154 |

| 3/12/2020 | ITA | 6650 | 1153 | 7803 | 5036 | 12,839 | 2249 | 1258 | 1016 | 15,113 | 86,011 |

| 3/13/2020 | ITA | 7426 | 1328 | 8754 | 6201 | 14,955 | 2116 | 1439 | 1266 | 17,660 | 97,488 |

| 3/14/2020 | ITA | 8372 | 1518 | 9890 | 7860 | 17,750 | 2795 | 1966 | 1441 | 21,157 | 109,170 |

Literature review

NPI

The World Health Organization Influenza Pandemic Plan of 1999 puts considerable attention on the role of non-pharmaceutical public health interventions to contain or delay the spread of a new influenza virus [10]. NPI include early case isolation, social distancing using face masks, closing of schools and businesses shot-down [10]. The application of NPI proved to reduce the spread of the COVID-19 virus in several areas inside China [11–14]. However, to be effective, NPI requires authorities to agree in advance on a range of containment strategies, the population be informed and willing to adopt the necessary measures [10].

Analyzing the NPI applied during the influenza pandemic of 1918 Whitelaw [15] wrote: “To sum up, it is evident, that no public health law, which has not the endorsation and support of the public generally, can ever be reasonably well enforced.” More recently, the WHO [16] wrote: “Some of the lessons learned from the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic can be applied to influenza, including the success of public campaigns to encourage self-recognition of illness, telephone hotlines providing medical advice, and early isolation when potential patients seek health care.” Several variables have proved necessary to get public endorsement for the application of NPI such as the perceived risk, severity of the consequences as well as response efficacy of the adopted measures [17, 18]. Therefore, while NPI has proved to be effective in limiting the spread of a pandemic, there must be a public endorsement of their employability. Giving people the right information is essential to empower them to evaluate their risks and the importance of curtailing their freedoms in terms of virus spread limitation.

Emergency management and social media communication

The development of social media has changed the communication both in terms of information availability and flow. Collaborative generation and dissemination activities of several types of content are some of the most critical distinct features of social media. According to Brynielsson et al. [19] “Within the field of crisis communication, social media possibilities such as online sharing and social networking have had an impact on the way crisis information is disseminated and updated.” Among the many social media, Twitter has been widely used in emergency management literature due to its specific features. For example, Twitter allows to post comments visible to all audience but also directly targeting a specific audience due to the mention and reply function [20]. The hashtag feature might help support the rapid building of an issue around specific community problems or geographical areas [21].

Research on emergency management shows that Twitter has been used to improve situational awareness among communities [22]. It can inform local communities given emergency alerts [19], and can act as a tool to facilitate social and political trends for change during emergencies when emotions embolden people [23]. Despite its great potentiality, due to the unchecked and socially constructed nature, messages shared on Twitter might lead to disinformation contributing to the infodemic problem [24]. For example, Panagiotopoulos et al. [25] discuss the social amplification or reduction of risks that on the one hand might be caused due to the Twitter flow and that on the other hand could be monitored by those responsible for risk management. Similarly, Surian et al. [26] used Twitter discussions about human papillomavirus vaccines for clustering opinions and detecting risks for public health.

The COVID-19 emergency and the Infodemic

The COVID-19 is a global emergency “which started in Wuhan in China in early December 2019, brought into the notice of the authorities in late December, early January 2020, and, after investigation, was declared as an emergency in the third week of January 2020” [27]. At the time we are writing the COVID-19 has killed almost 2.5 million people worldwide. However, just a few months earlier, the nature and danger of the virus were hotly contested. The US Surgeon General, Jerome Adams tweeted on February 1st, 2020 “Roses are red, violets are blue, risk is low for #coronarvirus, but high for the #flu” [28]. On March 9th, 2020 the US President Donald Trump tweeted: “Last year 37,000 Americans died from the common Flu. Nothing is shut down, life and the economy go on... Think about that” [28]. When it became clear that the situation was much worse, and commenting on his previous statements on Twitter he later said: “circumstances change but it was a true statement at the time it was made” [28]. Therefore, the COVID-19 emergency differs from other emergencies as knowledge of the real risks was mainly unknown or at least debated at the early stages of development of the pandemic.

The development of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates the spread of fake news, false information based on non-checked facts [29]. In March 2020, a pool developed by YouGov and the Economist revealed that 13% of Americans believed the COVID-19 crisis a hoax, while even world leaders’ social media posts had to be deleted for spreading misinformation about the Coronavirus [29, 30]. The development of false and unchecked information, recently named infodemic [24] during the COVID-19 emergency is peculiar compared to other crisis. The limited scientific knowledge available and the lack of developing consensus among the population increased the initial spread of the virus due to the specific nature of the NPI required.

Twitter has proved to be “the dominant social reporting tool to spread information on social crises” [31]. Previous studies employing crisis and emergency risk communication models are based on the monitoring of the risks and the communication of warnings [32] to avoid social amplification of the risks [33]. However, the COVID-19 emergency represents a new context, where little knowledge was available at the beginning of the crisis on the real dangers. Understanding how communications flow on Twitter, shaping the community understanding of the risks in a situation where there is little or debatable knowledge on the dangers appears, therefore, central.

Methods

Our analysis included three steps. First, we explored the main topics in messages by five groups with regular twitter communication and sizable numbers of followers: institutions, news sources, elected officials, scientists and social media influencers using topic modelling methods. Second, we used social network analysis to assess the size and reach of social networks and identify boundary spanning opportunities (sources and messages that span social networks) [34]. Third, we conducted a chi-square trend analysis that analyzed the impact of the mounting crisis on the themes in social media message.

Data collection

We downloaded tweets posted on the topic of COVID-19 infection in Italy from February 11th to March 10th, 2020. A tweet is an online posting created by a Twitter user limited to 280 characters or less. Once published, the tweet will appear on the Twitter home pages of all users who follow the induvial who released the message. Users might retweet messages, amplifying selected and extending the spread of certain discussions. Twitter is the most heavily used micro-blogging platform in the world and provides access to its data. Although Twitter represents only a part of available social media, a number of studies have used Twitter data, with studies showing it is a reasonable proxy and representation of political, social and scientific opinions [35, 36].

We selected tweets based on their contents using both keywords and the hashtags: virus, Coronavirus, and COVID-19. Other keywords, such as, for example, SARS-CoV-2, were excluded since the tweets mentioning those words were few and also reporting the word “virus”. We received messages tweeted in Italian from the Twitter company and focused on the top retweeted messages, using an inclusion criterion that included more than 50% of total retweeted messages and ignored messages that did not attract attention from users. We only used the number of retweets as a metrics of virality because, since our interest was about examining the infodemic phenomenon, we were interested in the diffusion of the messages, instead of considering the users’ reactions (e.g., likes, feelings, comments and replies).

Data analysis

We analyzed the content in the data using Python (Python Software Foundation) and its topic modelling function to detect the main topics discussed in the messages using a computer-aided content analysis [37]. Content analysis provides a useful and multifaceted, methodological framework for Twitter analysis and supports the structuring of textual data by enabling categorizing and coding [38]. Within content analysis, topic modelling is a type of statistical modelling for discovering abstract “topics” that occur in a collection of documents or as in our case tweets. Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) approach was used to classify and code text into particular topics [39].

The original list obtained from the statistical analysis was then manually coded by the authors (MM, PT, and MLT). The emerging codes were circulated among the researchers, and the list of codes was included in a codebook. Several conference calls/meetings were held to fine-tune the codebook and to group codes that related to the same phenomena. We further analyzed the data until conceptual saturation was reached and no new codes or categories were generated or merged together [40]. In addition, we manually coded the most retweeted messages by senders using the description provided by the users themselves in the presentation of their account using open coding [41]. In some cases, when the account’s presentation was not enough to define a sender, we searched his/her profession or role using the web. This coding approach means that we created new codes according to the senders’ descriptions of their accounts, so creating categories reflecting the concepts about the types of actors. We iterated the aggregation and creation of codes until reaching a conceptual saturation with significant categories of actors. Therefore, we aggregated senders of tweets into five distinct categories: Institutions (e.g., messages from the government or the Italian NHI), News sources(e.g., messages from TV channels or journalists), Politicians (e.g., messages from personal accounts of politicians or political parties), Science Sources (e.g., messages from scientists), and Influencers (i.e. all the other influencing users, including V.I.P.’s, celebrities, and private users who accounted for a large number of retweets, using a cut-off point of 1400 retweets).

We employed a chi-square test of independence with standardized residuals to search for similarities and differences in topics discussed by source (e.g. topics mainly discussed by institutions, politicians, etc.) using R software [42].

As a second step, we analyzed the development of discussions and messages over time. We chose three periods: a) before February 24th; from Feb 25th to March 1st, when the number of infected individuals exceeded 200, and few regions of the country had implemented social distancing; and c) between March 1st and March 10th when the entire country was in lock-down. The numbers related to the daily spread of the disease are reported in Appendix 1 (Table 4). The social network map using the ForceAtlas2 algorithm [43] was produced using the software Gephi, open-source software for graph and network analysis that measures the relationships and flows between people, groups, or organizations [44, 45]. The layout provided by the software supported the grouping and alignment of nodes connected together and helped to determine the current community state of social networks and to identify boundary spanning opportunities.

As a third step, a chi-square trend analysis was employed to search for linear trends between the COVID-19 crisis and the number of retweets from each source (i.e., influencers, institutions, news, politicians, scientific sources) for each topic and the total number of retweets were analyzed and compared to available COVID-19 morbidity and mortality data.

Results

Topic analysis

Our data encompassed 74,306 messages that were retweeted more than 1.2 million times from a total number of 2.3 million assessed retweets. The data analysis revealed 14 major themes that were intensely discussed by the five groups. Table 1 reports the main topics discussed, with examples of each type of message, the number of retweets and the keywords used in the classification process. The chi-square analysis revealed significant differences between the topics discussed by each group (χ2=8437.5, df = 52, p < 0.001). We produced a double-entry table (topics of rows and actors on columns) and compared the actual results with expected results from the chi-square analysis. The differences between the expected versus the actual results were then divided by the square root of the variance function/expected value to obtain the Pearson’s residuals.

Table 1.

Themes, Categories, Codes, and Quotes from Most Retweeted Messages

| Topic Label | Keywords | Examples (Highest retweets) |

|---|---|---|

| Fear of foreigners’ reaction | Africa, Italy, Italian, migrants, quarantine, ports, government, illegal immigrants, NGOs, Chinese people, fear, to close, after, case, first | I have never been a defeatist, but it is difficult not to become one. There are too many ignorant, arrogant and selfish people in our country. The vaccine issue had suggested it, coronavirus confirms it dramatically. |

| China, Chinese people, [politician X], Tuscany, quarantine, state, governor, [politician W], [politician Z], [politician Y], declaration, president, to be, risk | “Are you worried about Coronavirus?” People from Veneto region: “we have the alcohol that protects us” People from Tuscany: “I don’t give a damn” People from Bari: “I have not taken anything, neither masks nor anything, I want to die” I have tears in my eyes. | |

| Infection risk and epidemic information | Italy, what, to be, can, contagion, only, WHO, epidemic, China, covid19italy, diffusion, people, days, situation, need | “You make unprotected sex and you are afraid of Coronavirus contagion” |

| Sacco [hospital], Milan, hospital, director, today, first, vaccine, emergency, Italian, [virologist 1], epidemic, service, interview, I follow the news, work | She swapped an infection just more serious than flu for a lethal pandemic. It is not so. | |

| Closing schools and universities and sports competitions | schools, closed, March, Milan, closing, Universities, Italy, all, Lombardy, Rome, region, government, closed, closes, Veneto | “Coronavirus, schools and universities closed forever.” |

| Serie A League, no public, football, Italy, Minister, Sports, Health, postponed, hope, update, stop, emergency, games, championship, first | #coronavirusitalia, soccer matches with closed doors for 12 Serie A teams: Juventus, Turin, Inter, Milan, Atalanta, Brescia, Verona, Udinese, Bologna, Parma, Sassuolo and Spal. Volleyball and rugby also stop | |

| Regional restrictions to mobility | Lombardy region, government, Italy, decree, quarantine, red zone/lockdown zone, [politician C], Veneto, measures, [politician Y], checks, regions, Milan, all | “Venice: free aperitif in St. Mark’s Square to start over again.” But did you understand that people must stay at home otherwise what starts again is the virus? |

| home, Milan, I stay at home, fear, Italy red zone, Rome, supermarkets, mayor, what, networking, appeal, state, rules, quarantine, people | #Istayathome Leave the virus out the door. Stay home and go out only for essential needs. | |

| Early cases of infection and risk of infection | cases, positive, two, patients, hospital, Lombardy, test, intensive care, region, people, Veneto, Spallanzani [hospital], hospitalized, emergency, Rome | While everyone was looking at poor immigrants arriving by boat and waiters at Chinese restaurants, the virus travelled comfortably in first class with a manager from Lombardy #coronavirus |

| case, first, positive, years, hospital, patient, infected, woman, state, man, hospitalized, Lombardy, Italy, test | My mom works in the ER of #codogno where this gentleman was [Patient 1]. You don’t know how much it hurts to know that she and all her colleagues will be quarantined for 15 days. Those who do this work should be thanked every day for what they do | |

| China, quarantine, Italy, Italian, WHO, Wuhan, passengers, people, ship, Chinese, Diamond_Princess, Italians, epidemic, dead | ER of Rimini. 81 years old. Cough, Coronavirus-positive There is no place for him because he is over 80.If he heals, it will be because he did it alone.You pay taxes for a lifetime, and that’s what comes back.Now tell me .... What would you do if you were one of his children or grandchildren and he died? | |

| Economic crisis and economic support to people and business | Italy, economy, crisis, EU, billions, emergency, China, tourism, GDP, recession, Milan, today, stock market, decline, Europe | Paranoia coronavirus, there are those who launch SOS to central banks: Fed and ECB intervene with concerted action to save the economy (or the markets?) Worst week since 2008, global stock burns $ 5 trillion. Record for fear index |

| measures, emergency, government, decree, count, Italy, businesses, economy, work, all, health, billions, new, minister, companies | Today meeting a pharmacist. Me: “How do you see the situation?” He: “if we had sold the equivalent of today’s masks in condoms 40–50-60 years ago, today we would have had fewer assholes on social media that talk about viruses as experts.” | |

| Updates infections and trends in Italy | cases, Italy, dead, update, contagions, infected, Lombardy, covid19italy, China, updates, deaths, new, hours, number, coronarvirusitaly | “However guys, we have all the countries with the highest number of coronaviruses in the world: Korea, China and Italy” |

| Risk of death for vulnerable people | flu, years, only, dead, elderly, first, people, dies, dead, die, sick, pathologies, Italy, say, what | I meet my nieghbour over eighty years old. I ask her if she is worried, answer “here you all think about the virus, but there are 18 degrees at the end of February when there should be 2, you all seem stupid”.Ok. |

| Propaganda, conspiracy and polemic | only, then, Italy, what, made, people, world, to be, fear, first, country, problem, Italians, say, government | A tyrant has turned our lives upside down, and it’s called coronavirus. We will resist and fight everywhere, in our homes, in the workplace. Helping the weakest and sacrificing ourselves for a better tomorrow. And then we’ll do it again. Coronavirus, you won’t win. We hunted worse. |

| Criticism of government’s action | [politician C], government, [politician Z], emergency, Italy, made, country, only, league, premier, [blogger], [politician V], [Institution A], Italians, | In my opinion, Cosimo de ‘Medici [historical character] managed the plague in Florence much better than how we are managing the coronavirus these days. |

| Information on coronavirus around the world | Italy, Germany, France, cases, USA, Europe, masks, first state, emergency, EU, China, countries, outbreak, country | #China is the only country that supports Italy: it donated 1000 lung ventilators, 50,000 # coronavirus swabs, 20,000 protective suits, 100,000 high-tech masks and 2 million ordinary medical masks. |

| Information and instructions for people behaviour | video, contagion, pizza, news, information, tv, photo, social, covid19italY, fake_news, rai [broadcaster], rules, Italy, only, Ansa [news] | For exceptional moments we need exceptional behaviour. Stay home and follow the directions of the Ministry of Health. |

| European Union’s role and action for COVID emergency | Italy, Eu, Europe, ESM, migrants, government, money, emergency, health, state, country, years, only, billions, Greece | “Anyway, the EU has not yet taken any significant initiative against the coronavirus epidemy, except for authorizing us to spend money coming from our debts. So, it did only one thing: wasting our time asking for the authorization.” |

| Hospitals emergency | emergency, doctors, hospitals, masks, Italy, Lombardy, first, healthcare, [Institution A], president, medical doctors and nurses, country, millions, great, moment | #coronavirus: statement by the President #Mattarella |

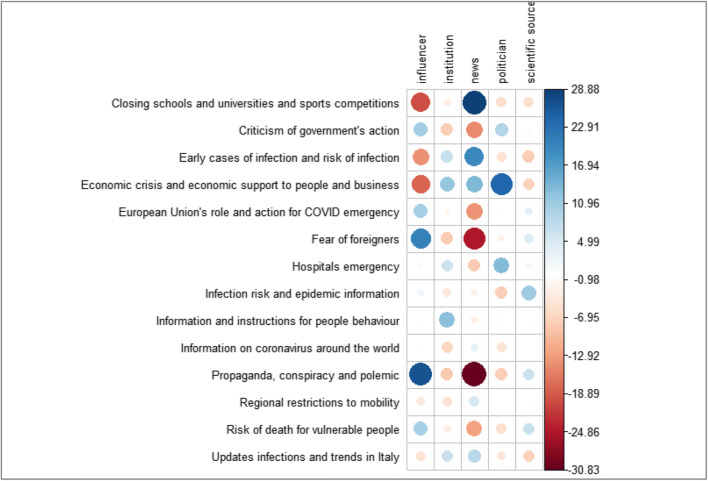

The topic analysis was developed using the function chisq in R. The results are shown in Fig. 1. Positive residuals are coloured in blue, defining an attraction between the corresponding rows (topics) and the column (actors). Negative residuals are coloured in red showing repulsion (negative association) between the corresponding row and column variables. The results show that influencers had higher standardized residuals, suggesting a higher than expected number of messages for the specific actor for messages that spoke to fear of foreigners and blamed immigrants in Italy for starting the COVID-19 outbreak. Politicians had higher residuals (suggesting higher than expected numbers of messages) for messages connected with managing the economic fallout, and to support citizens and businesses and hospital during the crisis. Not surprisingly, infection risks and rates and epidemiological information commonly originated from Scientific sources. In contrast, News sources were mainly concerned with the closing of entertainment, restaurants, schools and universities, identifying early cases of infections and highlighting the slowdown in the economy. The Institutional sources had a higher propensity for information and guidance for directing the behaviour of citizen.

Fig. 1.

Topic Analysis by Actor Type

Actor type relevance

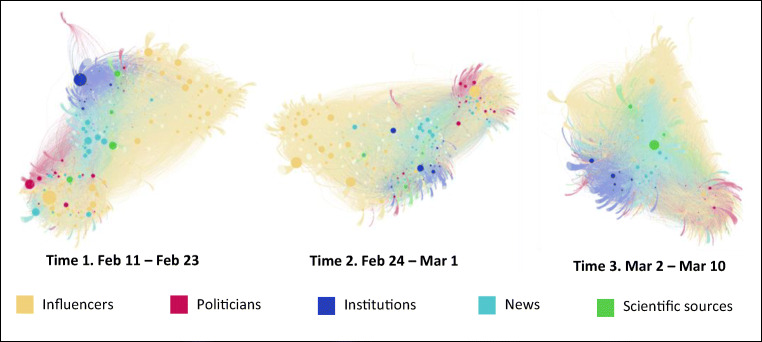

The findings for the Social Network Analysis suggested a prevalence of specific messages during the three periods. (Fig. 2) During the first time-period, messaging was dominated by influencers with several prominent actors that attracted and guided the national discourse. The results demonstrated, however, that during the most critical days, February 19th and 20th, when the first Italians tested positive for COVID-19 [46], the average percentage of retweets for influencers fell from 55% to 25% of the daily total, with scientific sources rising from an average of 8% to 42–48% of total tweets. The second time-period shows that the news channels and broadcasters were receiving more attention, but influencers were still relevant and often undermined the scientific messaging. During the third time-period, scientific sources began to dominate the discussion, building public confidence with messaging flow that was topically congruent and connected to news sources with both emphasizing key messages for dealing with the pandemic.

Fig. 2.

A Social Network Graph Based on Tweets

Topic and actor type relevance during the crisis development

The chi-square trend analyses follow the three main periods previously discussed (Tables 2 and 3). During the three time-periods, the infection rates were increasing with the total number of cases moving from three cases on Feb 11th to 1694 cases on March 1st, and to 10,142 cases on March 10th. The results showed that some topics dropped dramatically in their trending as the crisis intensified. This includes tweets promoting anti-immigrant propaganda and fearmongering against foreigners. Other topics, particularly science-based and practical information, grew in their relative importance and urgency. The reduced messaging by influencers made room for a range of sources to contribute solutions and build confidence. This included scientific sources, politicians and institution, who collectively contributed to messaging that sought to build social trust and community activation.

Table 2.

Chi Square Trend Analysis of the Key Topics in the Three Time Periods

| Topic | Feb 11 – Feb 23 | % | Feb 24 – Mar 1 | % | Mar 2 – Mar 10 | % | χ2 Trend | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closing schools and universities and sports competitions | 15,961 | 5.4% | 24,511 | 7.1% | 46,060 | 8.0% | ↑ | 2028.10 | <0.001 |

| Criticism of government’s actions | 23,169 | 7.8% | 31,132 | 9.0% | 30,936 | 5.4% | ↓ | 2576.70 | <0.001 |

| Early cases of infection and risk of infection | 66,651 | 22.4% | 46,173 | 13.3% | 54,190 | 9.4% | ↓ | 26,666.0 | <0.001 |

| Economic crisis and economic support to people and business | 11,838 | 4.0% | 26,327 | 7.6% | 46,260 | 8.1% | ↑ | 4434.10 | <0.001 |

| European Union’s role and action for COVID emergency | 4972 | 1.7% | 8044 | 2.3% | 25,682 | 4.5% | ↑ | 5698.40 | <0.001 |

| Fear of foreigners | 40,587 | 13.7% | 40,163 | 11.6% | 27,264 | 4.7% | ↓ | 22,020.0 | <0.001 |

| Hospitals emergency | 5610 | 1.9% | 13,550 | 3.9% | 50,103 | 8.7% | ↑ | 19,044.0 | <0.001 |

| Infection risk and epidemic information | 41,526 | 14.0% | 32,952 | 9.5% | 57,651 | 10.0% | ↓ | 2493.40 | <0.001 |

| Information and instructions for people behaviour | 10,095 | 3.4% | 18,302 | 5.3% | 23,418 | 4.1% | – | 70.79 | <0.001 |

| Information on coronavirus around the world | 7805 | 2.6% | 17,907 | 5.2% | 33,962 | 5.9% | ↑ | 4198.70 | <0.001 |

| Propaganda | 30,961 | 10.4% | 30,338 | 8.7% | 49,117 | 8.6% | ↓ | 732.18 | <0.001 |

| Regional restrictions to mobility | 17,663 | 5.9% | 19,352 | 5.6% | 88,029 | 15.3% | ↑ | 23,588.0 | <0.001 |

| Risk of death for vulnerable people | 7697 | 2.6% | 20,138 | 5.8% | 19,926 | 3.5% | – | 60.35 | <0.001 |

| Updates on infections and trends in Italy | 12,396 | 4.2% | 18,371 | 5.3% | 21,763 | 3.8% | – | 201.63 | <0.001 |

| Total | 296,931 | 100.0% | 347,260 | 100.0% | 574,361 | 100.0% | |||

Table 3.

Chi Square Trend Analysis of the Key Actors in the Three Time Periods

| Actors | Feb 11 – Feb 23 | % | Feb 24 – Mar 1 | % | Mar 2 – Mar 10 | % | χ2 Trend | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influencer | 173,829 | 58.5% | 191,853 | 55.2% | 269,989 | 47.0% | ↓ | 11,696.0 | <0.001 |

| Institution | 13,616 | 4.6% | 19,368 | 5.6% | 46,727 | 8.1% | ↑ | 4531.80 | <0.001 |

| News | 64,147 | 21.6% | 80,663 | 23.2% | 155,994 | 27.2% | ↑ | 3632.70 | <0.001 |

| Politician | 27,650 | 9.3% | 40,907 | 11.8% | 49,330 | 8.6% | – | 376.97 | <0.001 |

| Scientific source | 17,689 | 6.0% | 14,469 | 4.2% | 52,321 | 9.1% | ↑ | 4547.50 | <0.001 |

| Total | 296,931 | 100.0% | 347,260 | 100.0% | 574,361 | 100.0% | |||

Discussion

This paper contributes to the significant body of literature examining the COVID-19 pandemic. Our results show the importance of social media in supporting a community-wide and ultimately nationally-coordinated effort to build public awareness and engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Analysis of social media themes highlights useful and damaging messages, including false claims that blamed COVID-19 on foreigners. Interestingly, several actors without a scientific background encouraged discussions about how best to prepare for COVID-19. In contrast, contentious and dissenting voices might slow the process to reach a fact-driven consensus, and even promote counterproductive actions such as downplaying the danger of public crowding.

Twitter and other social and digital means of communication have become essential channels for physicians and scientists to spreading health and public health information [47, 48]. Twitter proved to be a powerful knowledge translation tool to translate and transfer meaningful knowledge from healthcare authorities to the population, about what should be done or avoided [49, 50]. Twitter feed ultimately benefitted the global community during the pandemic by serving as a readily accessible and trusted source for reliable and science-based information [48]. COVID-19 also highlighted the danger of a serious infodemic [51], with an over-abundance of information with uncertain accuracy, making it difficult for individuals to select the sources for actionable information and guidance.

Political actions and actors impacted the coronavirus spread, by denying the COVID-19 realities, and promoted social interactions under the motto “let’s keep our habits, we can’t stop Milan and Italy.” These public actions effectively helped spread the virus, only to back-track days later as the number of affected COVID-19 people dramatically increased and the pandemic mortality emerged [52]. Some tweets contained messages promoting fear and falsely blaming foreigners’ for the illness and created a false promotion that underestimated the severe impact of COVID-19. These actions undermined social trust and preparedness, exacerbating a general sense of fear and panic across Italy as the pandemic was fast becoming a debilitating national emergency.

There are many lessons to be learned for other nations about the experience of social media messages in Italy. Paramount is the importance of clear, convincing, fact-based and actionable messaging, to overcome misinformation and to garner the trust of the public during a challenging time. A handful of countries, including Singapore, Taiwan, Germany, Iceland, have managed to stay on top of their outbreaks by adhering to radical transparency, promoting community activism, while aggressively testing to find cases, quarantining contacts, and keeping viral transmission from going into an exponential growth phase [53]. Taiwan’s early recognition of the crisis, daily briefings to the public, and simple health messaging allowed the government to reassure the public by delivering timely, accurate, and transparent information regarding the evolving epidemic [54]. Additionally, the lessons from China and Singapore show that when the NPI reached the target of limiting the Covid-19 spread, new emerging cases can require the reintroduction of containment measures. Timeliness in accurate public messaging using both smart technology and traditional press conferences by trusted leaders was crucial.

Our study has inherent limitations. While Twitter has become an essential platform for textual communication and information sharing, the tweets represent only a sample of people’s communication and human interactions. However, there are many studies using Twitter data that consider it a reasonable proxy of the user’s mental models [42, 55]. We realize that the tweets also exhibit specific characteristics of brevity, fluidity, and meaning embedded in a broader context. This can pose challenges for the researcher engaged in content analyses. Third, the systematic limitation to analyze twitter methods “statistically” may be appropriate but as of yet un-validated for analyzing twitter, key messages, key actors, and evolution over time. Fourth, the COVID-19 pandemic and its rapidity evolving social, psychological, economic, or geographically attributes mean that the analysis is accurate only in the context of the limited time frame being studied. The co-variates may undoubtedly alter the findings and statistical results to where they are applied. Further development of statistical procedures which can be validated and replicated is needed with this type of data. Fifth, our analysis focused only on tweets posted in Italy. The different spread of social networks among generations or genders in different cultures and countries might affect our results. Finally, we focused on a limited period of time. Extending our analyses likely could have led to different findings.

Conclusions

Societies need to respond quickly to pandemics to protect the health and well-being of their citizens. In this exploratory work, we developed a systematic method to analyze Twitter messages, understand key messages, key actors and their evolution over time. We showed that social media could be used effectively to respond to the pandemic through transparent and convincing messages, rooted in scientific knowledge, to help build confidence and improve the implementation effectiveness of policies, ending up as an effective knowledge translation tool to facilitate the communication with the population. Despite the infodemic, the threats from fake news, trolls and bots that automatically produce and share contents on social media, the scientific voice and other institutional sources of information were able to dominate and be spread among people over the acute phase of the outbreak, so gaining their trust and public engagement in facing the pandemic. Countries that are transparent on the state of their country and provide truthful health information for their citizens will likely gain public trust and more rapid NPI uptake and compliance. Finally, we believe that an area for future research entails examining how social media and other readily collected public data could be leveraged to improve methods for public messaging, assessing the spread of the virus and support appropriate public health actions. Twitter can be leveraged to improve population health preparedness, better and early public response and support public policy actions [56].

Appendix 1

Author’s contributions

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. MM, PT, MLT, FDM and LC conceived the ideas for the study. MM, PT, MLT: data collection and analysis. MM: methodology and writing the original draft. FDM,PB, RT, and LC editing and review of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Pavia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

LC and PB share last authorship

MM, PT, and MLT share first authorship

This article is part of the Topical collection on Mobile; Wireless Health

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferguson, N.M., Laydon, D., Nedjati-gilani, G., et al. Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions ( NPIs ) to Reduce COVID- 19 Mortality and Healthcare Demand.; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Parodi SM, Liu VX. From Containment to Mitigation of COVID-19 in the US. Jama. 2020;323(15):1441–1442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cobianchi L, Pugliese L, Peloso A, Dal Mas F, Angelos P. To a New Normal: Surgery and COVID-19 during the Transition Phase. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e49–e51. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobianchi L, Dal Mas F, Peloso A, et al. Planning the Full Recovery Phase: An Antifragile Perspective on Surgery after COVID-19. Ann Surg. 2020;272(6):e296–e299. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romani, G., Dal Mas, F., Massaro, M., et al. Population Health Strategies to Support Hospital and Intensive Care Unit Resiliency During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Italian Experience. Popul Health Manag. 2020;In press. doi:0.1089/pop.2020.0255 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ioannidis, J.P.A. A fiasco in the making? As the coronavirus pandemic takes hold, we are making decisions without reliable data. STAT+. Published 2020. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.statnews.com/2020/03/17/a-fiasco-in-the-making-as-the-coronavirus-pandemic-takes-hold-we-are-making-decisions-without-reliable-data/

- 7.Glimmerveen L, Nies H, Ybema S. Citizens as Active Participants in Integrated Care : Challenging the Field ’ s Dominant Paradigms. Int J Integr Care. 2019;19(1):1–12. doi: 10.5334/ijic.4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madhav, N., Oppenheim, B., Gallivan, M., Mulembakani, P., Rubin, E., Wolfe N. Pandemics : Risks, Impacts, and Mitigation. In: Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, et al., eds. Disease Control Priorities (Third Edition): Volume 9, Disease Control Prioritie. World Bank; 2017:315-345. [PubMed]

- 9.Hatchett RJ, Meecher CE, Lipsitch M. Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(18):7582–7587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610941104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. WHO Global Influenza Preparedness Plan. The Role of WHO and Recommendations for National Measures before and during Pandemics.; 2005.

- 11.Ji, T., Chen, H-L, Xu, J., et al. Lockdown contained the spread of 2019 novel coronavirus disease in Huangshi city, China: Early epidemiological findings. Clin Infect Dis. Published online 2020. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Leung K, Wu JT, Liu D, Leung GM. First-wave COVID-19 transmissibility and severity in China outside Hubei after control measures, and second-wave scenario planning: a modelling impact assessment. Lancet. 2020;395(10233):1382–1393. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30746-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong Q, Jin H, Sun Z, Kao Q, Chen J. Non-pharmaceutical intervention strategies for outbreak of COVID-19 in Hangzhou China. Public Health. 2020;182:185–186. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowling BJ, Ali ST, Ng TWY, et al. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet Public Heal. 2020;5(5):e279–e288. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitelaw BYTH. Practical Aspects of Quarantine for Influenza. Can Med. 1919;9(12):1070–1074. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4770(08)60759-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Writing Group Nonpharmaceutical Interventions for Pandemic Influenza, National and Community Measures. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(1):88–94. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.051371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams L, Rasmussen S, Kleczkowski A, Maharaj S, Cairns N. Protection motivation theory and social distancing behaviour in response to a simulated infectious disease epidemic. Psychol Heal Med. 2015;20(7):832–837. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2015.1028946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teasdale E, Yardley L, Schlotz W, Michie S. The importance of coping appraisal in behavioural responses to pandemic flu. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17(1):44–59. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brynielsson J, Granåsen M, Lindquist S, Narganes Quijano M, Nilsson S, Trnka J. Informing crisis alerts using social media: Best practices and proof of concept. J Contingencies Cris Manag. 2018;26(1):28–40. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu W, Lai CH, Xu W. (Wayne). Tweeting about emergency: A semantic network analysis of government organizations’ social media messaging during Hurricane Harvey. Public Relat Rev. 2018;44(5):807–819. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho SE, Jung K, Park HW. Social media use during Japa n’s 2011 earthquake: How Twitter transforms the locus of crisis communication. Media Int Aust. 2013;149:28–40. doi: 10.1177/1329878x1314900105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neu D, Saxton G, Everett J, Shiraz AR. Speaking Truth to Power: Twitter Reactions to the Panama Papers. J Bus Ethics. 2020;162(2):473–485. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-3997-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Saggaf Y, Simmons P. Social media in Saudi Arabia: Exploring its use during two natural disasters. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2015;95:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2014.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Munich Security Conference Speech. 15Th Febr 2020. 2020;(February):1-5.

- 25.Panagiotopoulos P, Barnett J, Bigdeli AZ, Sams S. Social media in emergency management: Twitter as a tool for communicating risks to the public. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2016;111:86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2016.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surian D, Nguyen DQ, Kennedy G, Johnson M, Coiera E, Dunn AG. Characterizing twitter discussions about HPV vaccines using topic modeling and community detection. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(8). doi:10.2196/jmir.6045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Hua J, Shaw R. Corona virus (Covid-19) “infodemic” and emerging issues through a data lens: The case of china. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7). doi:10.3390/IJERPH17072309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Woodward, A. Coronavirus : US Surgeon General admits he shouldn ’ t have compared virus to the flu. Idipendent. April 2020:1-10.

- 29.Robson, D. Why smart people believe coronavirus myths. BBC Future. April 2020:1-13.

- 30.BBC. Coronavirus : World leaders ’ posts deleted over fake news. BBC News. March 2020.

- 31.Oh O, Agrawal M, Rao HR. Community intelligence and social media services: A rumor theoretic analysis of tweets during social crises. MIS Q Manag Inf Syst. 2013;37(2):407–426. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.2.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds B, Seeger MW. Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. J Health Commun. 2005;10(1):43–55. doi: 10.1080/10810730590904571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pidgeon N, Kasperson RE, Slovic P. The Social Amplification of Risk. Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511550461

- 34.Massaro M, Dumay J, Bagnoli C. When the investors speak. Intellectual capital disclosure and the web 2.0. Manag Decis. 2017;55(9):1888–1904. doi: 10.1108/MD-10-2016-0699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bright, J., Hale, S., Ganesh, B., Bulovsky, A., Margetts, H., Howard, P. Does Campaigning on Social Media Make a Difference? Evidence From Candidate Use of Twitter During the 2015 and 2017 U.K. Elections. Communic Res. 2019;in press.

- 36.Huang L, Clarke A, Heldsinger N, Tian W. The communication role of social media in social marketing: a study of the community sustainability knowledge dissemination on LinkedIn and Twitter. J Mark Anal. 2019;7(2):64–75. doi: 10.1057/s41270-019-00053-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis. An Introduction to Its Methodology. Sage Publications; 2013.

- 38.Bruns A, Liang YE. Tools and methods for capturing Twitter data during natural disasters. First Monday. 2012;17(4). doi:10.5210/fm.v17i4.3937

- 39.Blei DM, Ng AY, Jordan MI. Latent Dirichlet allocation. J Mach Learn Res. 2003;3:993–1022. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-411519-4.00006-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria. Qual Sociol. 1990;13(1):3–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00988593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M., Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd Ed. Sage Publications; 2013.

- 42.Bowen M, Lovell A. Stigma: the representation of mental health in UK newspaper Twitter feeds. J Ment Heal. 2019;0(0):1-7. doi:10.1080/09638237.2019.1608937 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Jacomy M, Venturini T, Heymann S, Bastian M. ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fortunato S. Community detection in graphs. Phys Rep. 2010;486(3-5):75–174. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2009.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dill, J., Earnshaw, R., Kasik, D., Vince, J., Wong, P.C. Expanding the Frontiers of Visual Analytics and Visualization. Springer

- 46.Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical Care Utilization for the COVID-19 Outbreak in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1545–1546. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chretien KC, Azar J, Kind T. Physicians on Twitter. JAMA. 2011;305(6):366–368. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merchant, R.M., Lurie, N. Social Media and Emergency Preparedness in Response to Novel Coronavirus. JAMA. Published online 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4469 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Dal Mas F, Garcia-Perez A, Sousa MJ, Lopes da Costa R, Cobianchi L. Knowledge Translation in the Healthcare Sector. A Structured Literature Review. Electron J Knowl Manag. 2020;18(3):198–211. doi: 10.34190/EJKM.18.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dal Mas, F., Cobianchi, L., Piccolo, D., Barach, P. Knowledge Translation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In: Lepeley MT, Morales O, Essens P, Beutell NJ, Majluf N, eds. Human Centered Organizational Culture Global Dimensions. Routledge; 2021:139-150. doi:10.4324/9781003092025-11-14

- 51.Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Besser, L. Italy ’ s coronavirus disaster : At first , officials urged people to go out for an aperitif . Now , doctors must choose who dies. ABC news. 2020:1-10.

- 53.Dewan, A., Pettersson, H., Croker, N. As governments fumbled their coronavirus response, these four got it right. Here’s how. CNN Website. Published 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/16/world/coronavirus-response-lessons-learned-intl/index.html

- 54.Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big Data Analytics, New Technology, and Proactive Testing. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1341–1342. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ji X, Chun SA, Wei Z, Geller J. Twitter sentiment classification for measuring public health concerns. Soc Netw Anal Min. 2015;5(1):1–25. doi: 10.1007/s13278-015-0253-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hadgu, A.T., Jäschke, R. Identifying and analyzing researchers on twitter. In: WebSci 2014 - Proceedings of the 2014 ACM Web Science Conference. ; 2014. doi:10.1145/2615569.2615676