Abstract

Objectives:

This study examined the association of ED use in the first year of diagnosis and patient experiences in care among older adults with hematologic malignancies.

Materials and Methods:

Cross-sectional design using SEER-CAHPS® data from 2002-2015 to study Medicare fee-for-service enrollees with a primary diagnosis of leukemia or lymphoma. We linked the CAHPS survey data (patient-reported experiences with health services) to patients’ cancer registry information and Medicare outpatient claims from the SEER-CAHPS resource. We estimated associations of ED use and clinical characteristics with two CAHPS outcomes – “getting care quickly” (timeliness) and “getting needed care” (access) – with bivariate and multivariate analyses.

Results:

The analytic sample included 751 patients, 125 of whom had an ED claim in the first year of cancer diagnosis. The most frequent ED diagnosis clusters were fever and infection (n=17, 13.6%), orthopedic and injury (16, 12.8%) and pain (16, 12.8%). Significantly more enrollees with an ED claim were diagnosed with lymphoma (p < 0.01), lived in rural areas (p < 0.01), and lived in areas with many families living in poverty (p < 0.01). In adjusted models, enrollees with an ED claim reported significantly worse access to care (β −4.83; 95%CI −9.29,−.38; p = 0.03).

Conclusion:

The management of urgent care concerns for adults with hematologic malignancies remains an important clinical and quality improvement imperative. Further study is warranted to enhance the management of emergent complications in older adults receiving care for hematologic malignancies, with efforts that enhance coordination of ambulatory oncology care.

Keywords: hematologic diseases, Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS), patient experience, patient-centeredness

Introduction

For the last two decades, emergency department (ED) care for community-dwelling adults diagnosed with cancer was a controversial aspect of cancer care delivery.1,2 Although some patients require emergency services for acute health issues unrelated to cancer, evidence shows patients frequently sought ED services because of unaddressed symptom management during routine care.3 A recent systematic review of literature suggests that the burden of severe symptoms is a significant predictor of ED use in patients with cancer.4 Few studies examined these phenomena in patients with hematologic malignancies, principally relevant among older adults.5 Treatments with high-dose, systemic therapies frequently induce myelotoxicity and subsequently febrile neutropenia.6 Clinicians often recommend seeking emergency services to patients in the event of febrile neutropenia and other acute treatment-related toxicities.7 Although the evidence is low, the ED poses as a potential exposure to pathogens8 and may cause significant psychological distress for patients and caregivers.7 Additionally, the ED could become a negative experience due to multiple non-clinical reasons, including (but not limited to) disruptions to usual routines, transportation difficulties, iatrogenesis, and poorly coordinated follow-up with their medical oncologist.

There are few data sources to study ED use from a patient-centered perspective. However, the salience of patient experience data in overall health care quality increased with the introduction of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010. With the introduction of new payment models, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) linked a percentage of hospital reimbursement contingent with favorable patient experience survey outcomes.9 In 2015, the National Cancer Institute announced the publicly available Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) linked Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) resource for patient-centered cancer care quality research.10

Given that patients with hematologic malignancies are an understudied group in quality of care research, the purpose of this study was to examine ED use in this population and examine its association with health care experiences. We hypothesized that ED use in the first year of their diagnosis would be associated with less favorable experiences with timely access and receiving fully needed care. With these findings, we aimed to clarify the quality pitfalls that patients with hematologic malignancies experience to inform the development of interventions aimed at empirically improving patient experiences of care.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

We retrieved data available between the years 2002 and 2015 from the SEER-CAHPS resource, a linkage of de-identified resources at the National Cancer Institute. The SEER-CAHPS resource contained data from older adults who reside in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End-Results (SEER) registry catchment areas and were also enrolled in in Medicare. The resource was able to link Medicare CAHPS patient experience surveys and Medicare Part B Outpatient (i.e., ‘OUTPAT’) files to study the delivery and quality of cancer care with a nationally representative sample. We used a retrospective, cross-sectional design to analytically compare health care experiences and ED use during the first year of a hematologic malignancy diagnosis.

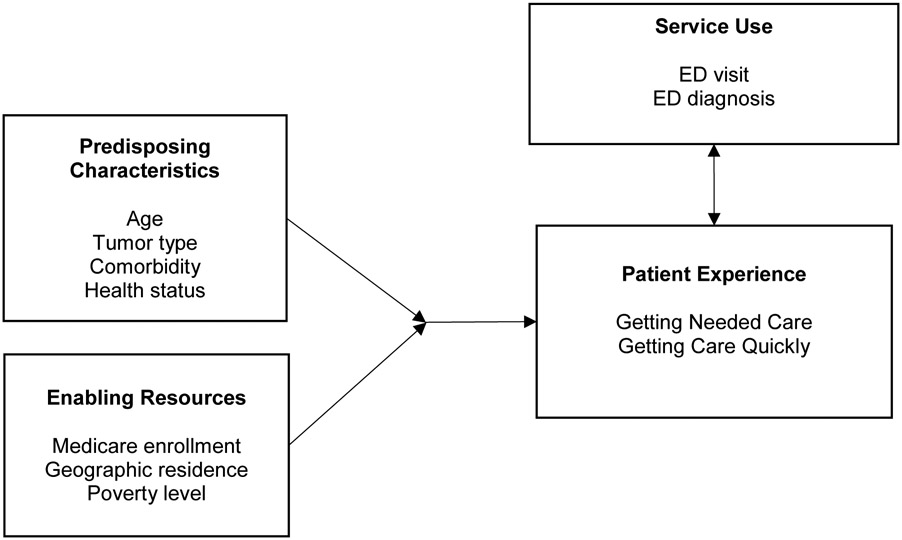

The behavioral model of health care utilization provided a conceptual framework to inform the study design and data analyses.11 Briefly, our synthesized framework posited that the use of health care services are influenced by predisposing characteristics and enabling resources that led to unresolved, acute health events, see Figure 1. Therefore, patient experiences of care represented the patient’s recollection of behaviors of health care providers and the interactions with health care systems following an acute health event.

Figure 1.

Synthesized conceptual framework, behavioral model of health care utilization.

This Institutional Review Board of the author’s university deemed this study exempt from human subjects review. The principal investigators signed a data use agreement with the National Cancer Institute before obtaining study data and complied with all terms of the agreement.

Participants

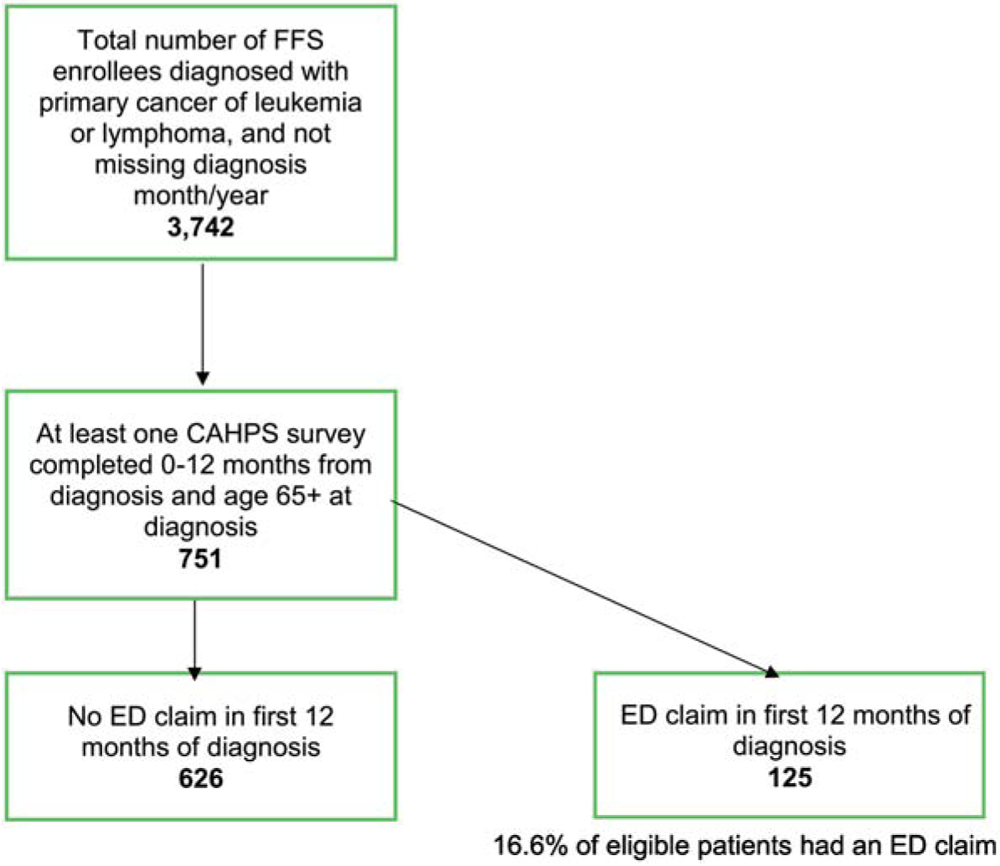

Eligible participants were Medicare fee-for-service enrollees captured by the SEER-CAHPS resource diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma, as claims from managed care enrollees were unavailable. Inclusion criteria required that the age at diagnosis was at least 65, month and year of the Medicare Fee-for-Service CAHPS survey completion was within 12 months of cancer diagnosis (n = 751). See Figure 2 for the eligibility flow diagram of the study. We included patients with an ED claim only if the claim date was within 12 months of the malignancy diagnosis. However, we did not require that the CAHPS survey be completed following an ED claim to increase the sample size of analyses. Therefore, we conceptualized ED use to demonstrate a correlational relationship with an array of processes that influence the patient experience with timeliness and access to health services instead of a causal relationship. We excluded cases from the final study cohort if leukemia or lymphoma were not the primary cancer and if the cancer diagnosis month and year were missing.

Figure 2.

Eligibility flow diagram.

Measurement

ED Use and Diagnosis.

We used a previously validated approach to identify ED claims in Medicare outpatient claim files with the following revenue center codes: ‘0450’-‘0459’, or ‘0981’.12 Medicare outpatient claims were structured with twenty-nine diagnosis codes in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) format. We examined the first claim diagnosis code for analysis, and then relied on the second diagnosis code if the first was missing, and so forth. While diagnosis codes were formatted with the ICD-10 format beginning October 1, 2015, this change did not affect any cases in the sample. ICD-9 codes were classified with twelve previously validated13 cancer-related diagnostic clusters: bleeding; cardiovascular; cytopenia; fatigue and neurological; respiratory; fever and infection; gastrointestinal; renal and urinary; malignancy; orthopedic and injury (e.g., closed fractures, contusions), pain, skin, and an additional cluster for miscellaneous diagnoses and imaging codes.

Patient experiences with care.

To assess timelines and access of health care, we used two CAHPS survey scales, “getting care quickly” (3 items) and “getting needed care” (4 items) reported in composite scores.14 The “getting care quickly” scale asked enrollees how often they received care when they were sick or injured, and received appointments when needed. The “getting needed care” scale asked enrollees the degree it was easy to obtain the tests or treatments they needed through their health plan. Enrollees completed the items with a four-point Likert scale (1=”never”, 4=”always”). The scales used a continuous scale and a linear mean transformation of the items.15 The outcome scores fell between “0” and “100”, which “0” represented the worst possible rating and “100” the best possible rating.

The original CAHPS developers constructed the scales after field studies, cognitive interviews, and testing with consumers.

Baseline characteristics.

We included the following variables from the various data files: gender; race; tumor histology,16 race/ethnicity, month and year of diagnosis, and urban/rural status, SEER geographic region at diagnosis (Northeast, Midwest, South, West); Charlson comorbidity score (none, 1, 2, or 3+);17 a measure of the percentage of households in poverty in the enrollee’s census tract; rural (vs. urban). We also included variables in the CAHPS case-mix adjustment:18 age, education level, general health status, mental health status [Likert scale, excellent to poor], received help responding, proxy answered survey questions, Medicaid dual eligibility (yes/no), low income subsidy, and Chinese language To improve risk adjustment, we developed a specific variable to reflect the severity of the diagnosed malignancy. Higher-risk diagnoses were acute leukemias, T-cell lymphoma, and natural killer cell lymphoma morphologies.

Analysis

We first examined each of the datasets - the Medicare outpatient claims, SEER registry data, and CAHPS survey - separately to assess missing data and identify unique observations. Next, we merged Medicare outpatient claims, SEER registry data, and CAHPS survey data at the enrollee-level. We calculated descriptive statistics (counts, percentages, and chi-squared tests) for ED diagnosis clusters and baseline characteristics. For the CAHPS survey measures, we estimated CAHPS case-mix adjusted scale means and performed multiple ordinary least squares linear regression to examine adjusted associations of baseline factors and use of the ED on “getting care quickly” and “getting needed care”. Models were fully adjusted with CAHPS case-mix adjustment, and sex, race/ethnicity, education, tumor type (leukemia v. lymphoma), and tumor severity.

We accounted for missing values of baseline factors and the CAHPS outcomes considered missing completely at random with multiple imputations procedures. Participants had missing data on 17.6% on the “getting care quickly” scale and 18% on the “getting needed care” scale. Multiple imputation with resampling was performed to reduce the standard errors of estimates and reduce potential bias with predicted distributions from the original sample.19 Two hundred imputations were performed, while simultaneously assessing for multicollinearity in the models. The analytic software omitted the following cases and variables during the imputation procedures due to collinearity: Hispanic ethnicity, those who lived alone and if a proxy answered the survey. As a sensitivity analysis, we examined the linear models with complete case data to assess the reliability of the imputations. We examined the model fit with the average relative increase in variance (RVI) for imputed regressions and the adjusted r2 estimate for complete case models.

We performed all analyses in Stata version 15 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). We used SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) macros to create the Charlson Comorbidity score and prepare the claims data for merging. The alpha rate of 0.05 was used for all significance tests.

Results

Sample

The final sample (n=751) included 125 patients with an ED claim in the first year of their cancer diagnosis (16.6%). We describe the characteristics of the sample in Table 1. Patients with ED claims were more likely to also report residence in urban and metropolitan areas (p < 0.001), and resided in areas with many families living in poverty (p = 0.004). The proportion of patients with lymphoma diagnoses was significantly higher in the cohort with an ED claim (p = 0.01). Among the 125 patients with an ED claim, 43 (34.4%) were octogenarians at the time of the claim. Additionally, thirty patients (24%) also had an outpatient chemotherapy claim within the first year of diagnosis. Other demographic characteristics were comparable between the cohorts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants diagnosed with leukemia and lymphoma during the first 12 months of diagnosis (N=751).

| Eligible Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No ED claim (n=626) |

ED claim (n=125) |

P-valuea | |

| Characteristic | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Diagnosis | 0.01 | ||

| Leukemia | 260 (41.5) | 37 (29.6) | |

| Lymphoma | 366 (58.5) | 88 (70.4) | |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.41 | ||

| 65-69 | 112 (17.9) | 23 (18.4) | |

| 70-74 | 157 (25.0) | 24 (19.2) | |

| 75-79 | 136 (21.8) | 35 (28.0) | |

| 80-85 | 128 (20.4) | 22 (17.6) | |

| 85+ | 93 (14.9) | 21 (16.8) | |

| Gender | 0.39 | ||

| Male | 327 (52.2) | 59 (47.2) | |

| Female | 299 (47.8) | 66 (52.8) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.39 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 568 (90.7) | 110 (88.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Pacific Islander | 58 (9.3) (3.7) | 15 (12.0) | |

| Education | 0.77 | ||

| 8th grade to high school | 146 (23.4) | 28 (22.4) | |

| High school graduate or GED | 176 (28.1) | 37 (29.6) | |

| Some college or higher or unknown | 304 (48.5) | 60 (48.0) | |

| SEER region at diagnosis | 0.03 | ||

| Northeast | 125 (20.0) | 16 (12.8) | |

| Midwest | 48 (7.7) | 17 (13.6) | |

| South | 123 (19.6) | 32 (25.6) | |

| West | 330 (52.7) | 60 (48.0) | |

| Modified Charlson | 0.96 | ||

| Comorbidity Score | |||

| 0 | 144 (23.0) | 58 (46.4) | |

| 1 | 47 (7.5) | 17 (13.6) | |

| ≥ 2 | 41 (6.6) | 19 (15.2) | |

| Unknown | 394 (62.9) | 31 (24.8) | |

| General health status | 0.04 | ||

| Excellent, very good, good | 435 (69.5) | 74 (59.2) | |

| Fair/poor or unknown | 191 (27.5) | 51 (40.8) | |

| Urban/rural residency at diagnosis | <0.001 | ||

| Big Metro, Metro, Urban | 593 (94.7) | 101 (80.8) | |

| Rural, less-urban | 33 (5.3) | 24 (19.2) | |

| Did a proxy help complete survey | 0.26 | ||

| No | 462 (73.8) | 78 (62.4) | |

| Yes | 82 (13.1) | 19 (15.2) | |

| Unknown | 82 (13.1) | 28 (22.4) | |

| Tumor severity indicator | 0.01 | ||

| Less severe | 502 (80.2) | 112 (89.6) | |

| More severe | 124 (19.8) | 13 (10.4) | |

| Live alone | 0.65 | ||

| No | 92 (14.7) | 29 (23.2) | |

| Yes | 29 (4.6) | 11 (8.8) | |

| Unknown | 505 (80.7) | 85 (68.0) | |

| Percentage of census tract in poverty | 0.004 | ||

| 0-<5% poverty | 186 (29.7) | 21 (16.8) | |

| 5-<10% poverty | 173 (27.6) | 35 (28.0) | |

| 10-<20% poverty | 195 (31.2) | 44 (35.2) | |

| 20-100% poverty | 69 (11.0) | 25 (20.0) | |

Abbreviations: FFS, fee-for-service; GED, general education development; SEER, surveillance epidemiology end-results registry.

Pearson chi-square test.

Emergency department diagnoses

Fever was the most frequent primary ED diagnosis cluster, occurring in 17 (13.6%) of the 125 cases of ED claims (see Table 2). Other frequent primary claim clusters were orthopedic and injury (n= 16, 12.8%), pain (n= 16, 12.8%), renal and urinary (n=13, 10.4%), cardiovascular (n= 12, 9.6%), and bleeding (n= 8, 6.4%). The most frequent and specific first ICD-9 claim diagnosis code was epistaxis (i.e., nosebleed) and occurred in < 11 claims.

Table 2.

Primary ED diagnosis cluster (n=125)

| Diagnosis Cluster | No. | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Fever, Infection | 17 | 13.6 |

| Orthopedic, Injury | 16 | 12.8 |

| Pain | 16 | 12.8 |

| Renal, Urinary | 13 | 10.4 |

| Cardiovascular | 12 | 9.6 |

| Bleeding | ** | ** |

| Gastrointestinal | ** | ** |

| Respiratory | ** | ** |

| Fatigue, Neurological | ** | ** |

| Cytopenia | ** | ** |

| Malignancy | ** | ** |

| Skin | ** | ** |

| Other, Imaging | ** | ** |

Abbreviation: ED, emergency department.

Cell sizes suppressed for confidentiality (n < 11).

Getting care quickly and getting needed care

We found no significant differences between the case-mix adjusted means of getting needed care between the groups (88.8 [84.2, 93.4] no ED visit vs. ED 88.2 [80.4, 96.1] with an ED visit, p = 0.10). However, we observed a significant association in fully adjusted linear models after adjusting for additional clinical and social factors, as shown in Table 3. An ED visit was associated with a 4.83 unit decrease in the getting needed care scale (β −4.83; 95%CI −9.29, −.38; p = 0.03). There were no significant differences in the “getting care quickly” and “getting needed care” scales by tumor type, rural/urban status and percentage of census tract living in poverty. We acknowledge relatively low internal consistency values in our analytic dataset (Cronbach alpha, 0.61 “getting care quickly” and 0.53 “getting needed care”), although CMS found favorable reliabilities (> .80) for these scales at the plan-level.20 In our sensitivity analysis of complete cases only, we observed identical magnitudes and directions of regression coefficients.

Table 3.

Fully adjusted linear regression models of CAHPS scales.

| Variable | Composite/Scale Domainsa Beta (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Get Care Quickly | Get Needed Care | |

| ED claim (v no claim) | ||

| ED claim | −2.35 (−7.95, 3.25) | −4.83 (−9.29, −0.38)* |

| Age at survey (v 65-69) | ||

| 70-74 | −4.70 (−10.9, 1.53) | −3.13 (−8.07, 1.80) |

| 75-79 | −2.10 (−8.44, 4.24 | 3.15 (−1.81, 8.11) |

| 80-84 | −1.07 (−7.73, 5.57) | 4.00 (−1.25, 9.25) |

| 85+ | −0.27 (−7.56, 7.02) | 3.39 (−2.28, 9.07) |

| Percentage of census tract in poverty (v 0-<5% poverty) | ||

| 5-<10% poverty | −2.98 (−8.42, 2.47) | .93 (−3.36, 5.23) |

| 10-<20% poverty | −7.02 (−12.5, −1.52)* | −.32 (−4.72, 4.08) |

| 20-100% poverty | −6.18 (−13.7, 1.33) | .71 (−5.35, 6.77) |

| Urban-Rural status | ||

| Rural, less-urban (v Big Metro, Metro, Urban) | 3.98 (−4.29, 12.3) | −1.98 (−8.88, 4.92) |

| SEER region (v Northeast) | ||

| Midwest | 2.54 (−6.41, 11.5) | 2.42 (−4.28, 9.12) |

| South | −1.12 (−8.00, 5.75) | 1.52 (−4.00, 7.05) |

| West | −1.61 (−7.19, 3.97) | −2.90 (−7.36, 1.55) |

| Modified Charlson comorbidity score (v 0) | ||

| 1 | 3.68 (−3.90, 11.3) | 0.49 (−5.20, 6.18) |

| 2 | 7.81 (−2.62, 18.2) | 0.41 (−8.12, 8.94) |

| 3+ | −0.98 (−11.7, 9.70) | 4.86 (−3.77, 13.5) |

Additionally adjusted for CAHPS case mix adjustment procedures, gender, race/ethnicity, tumor type and tumor severity.

p<0.05.

Discussion

This study of older adults diagnosed with leukemia and lymphoma examined patterns of ED use and patient experiences during the first year of their cancer diagnosis. We found that 16.6% of older adults used the ED in the first year of diagnosis, and the most frequent primary ED diagnoses were fever, orthopedic ailments and injuries, and pain issues. Among those who used the ED in the first year, we found significantly poorer scores on timeliness and access to care measures than those who did not visit the ED. Additionally, we found the participants with an ED claim in the first year of cancer diagnosis were significantly less likely to report residence in rural and less-urban geographic areas. However, we did not detect this effect in adjusted linear models. We found more ED claims among patients diagnosed with lymphoma than leukemia (70.4% vs. 29.6%). Previous research observed higher ED visit rates in patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma compared to other common hematologic malignancies.21 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to examine a national cohort of older adults with hematologic malignancies and assess the relationship between ED use and experiences of care.

When considering other studies, we observed similar clusters of cancer-related clusters. In a population-based study with the North Carolina Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool (NC-DETECT), Mayer and colleagues (2011) observed that 7.7% of cancer survivors in North Carolina visited the ED in one year, primarily for pain, respiratory and gastrointestinal issues.13 In another study in adults with leukemia, Bryant and colleagues (2015) observed 80 patients diagnosed with acute myeloid and lymphocytic leukemias one year following induction therapy. In their study, the patients primarily accessed ED services to manage fever and infection (55%), bleeding (12%) and GI issues (11%).22 Considering that our study population included older adults diagnosed with leukemia and lymphoma, we expected to observe higher incidences of myelotoxicity symptoms compared to the general population of adults diagnosed with cancer.

In the case of febrile neutropenia, our highest observed diagnosis cluster, ED management for patients with hematologic malignancies is complex but necessary. Previous research has reported the incidence of febrile neutropenia (temperature ≥ 38.3°C and absolute neutrophil count <1,000/mm3) in adult patients with hematologic malignancies treated with chemotherapy to exceed 40%.23 Febrile neutropenia was estimated to represent approximately 25% of cancer-related ED visits.8 The majority of ED admissions for febrile neutropenia are high-risk (Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer [MASCC] score < 21 and American Society of Clinical Oncology [ASCO] criteria met).7,24 The oncology nurse’s role in advocating for appropriate urgent interventions for patients is vital because they are primarily responsible for the oncology practice’s phone triage and risk assessment.25

Previous research studies have documented significant differences in the timeliness and access to care measures across various cohorts of adults with cancer. For example, Mollica and colleagues (2018) found that urban adults with solid tumors were more likely to report lower on the access to care measures in the first 12 months of their diagnosis.26 In another study, Halpern and colleagues (2017) studied CAHPS outcomes in adults with solid tumors in their last year of life. Overall, they found traditional Medicare patients were significantly more likely to report the highest possible rating (i.e., 100) on the getting needed scale than patients enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans.27 Our findings present a novel contribution to the literature: ED use in the first year of cancer diagnosis was associated with a significant, negative association on timeliness of care. In the context of future hypothesis-testing research, we would hope to see patient experiences measured with focused, patient-reported instruments such as the Emergency Department Patient Experiences with Care (EDPEC) Survey.28 Prospective studies to measure patient experiences in care following ED visits might lead to increased internal validity and causal inference. Additionally, our findings suggest the exploration into objective measures related to timeliness and access of cancer care services to mitigate current limitations of existing measures.

Several study limitations that should be considered. All data obtained from the SEER-CAHPS resource were originally compiled for purposes other than this study. Therefore, our capacity to address unknown data errors and issues related to survey measurement were limited. Although the internal consistency statistics were not ideal for both the timeliness and access to care measures, the CAHPS survey provided a feasible approach to address patient-centeredness in adults with hematologic malignancies. The cross-sectional nature of the study design limits the inference of the factors to associations, instead of predictors. CMS used ICD-9 codes for administrative (i.e., billing) purposes and, potentially, may not be identical to clinical data found in the patients’ electronic health record. We did not exclude participants without continuous Parts A and B enrollment in Medicare, although all eligible patients were 65 years of age or older. Data on ED visits leading to inpatient admissions were not obtained design due to feasibility issues. Finally, one should compare CAHPS outcomes in any clinical context cautiously; health care experiences are a patient-centered, individual, and nuanced assessment that is subject to social desirability and self-report biases.29

In conclusion, we found that the timeliness and access of health care were salient issues in older patients diagnosed with leukemia and lymphoma. Our findings provide future directions to inform research opportunities aimed at improving health system strategies relating to the access of care for high-risk older patients. We suggest a priority area of research be focused on the delivery of services for febrile neutropenia, and to apply the lessons learned from experiences of patients’ to inform subsequent practice and policy changes.

Acknowledgments

This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the American Cancer Society and United States Department of Health and Human Services. We are grateful for programming assistance from Ling Li and guidance from the SEER-CAHPS program at the National Cancer Institute.

Funding

Supported in part by the American Cancer Society (33507-DCSN-19-048-01-SCN) and the National Cancer Institute (P30-CA-046592).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest:

None.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Published online 2001. doi: 10.1037/e317382004-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. National Academies Press; 1999:6467. doi: 10.17226/6467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. (Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA, eds.). National Academies Press; 2013. doi: 10.17226/18359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lash RS, Bell JF, Reed SC, et al. A Systematic Review of Emergency Department Use Among Cancer Patients: Cancer Nurs. 2017;40(2):135–144. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. Facts and Statistics. Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. Published 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.lls.org/http:/llsorg.prod.acquia-sites.com/facts-and-statistics/facts-and-statistics-overview/facts-and-statistics [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almeida AM, Ramos F. Acute myeloid leukemia in the older adults. Leuk Res Rep. 2016;6:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lrr.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baugh CW, Wang TJ, Caterino JM, et al. Emergency Department Management of Patients With Febrile Neutropenia: Guideline Concordant or Overly Aggressive? Mark Courtney D, ed. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(1):83–91. doi: 10.1111/acem.13079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baugh CW, Faridi MK, Mueller EL, Camargo CA, Pallin DJ. Near-universal hospitalization of US emergency department patients with cancer and febrile neutropenia. Ammann RA, ed. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(5):e0216835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal AK, Hahn L, Merchant RM, Rosin R. Handcrafting the Patient Experience. NEJM Catal. 2019;5(5). doi: 10.1056/CAT.19.0618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chawla N, Urato M, Ambs A, et al. Unveiling SEER-CAHPS®: A New Data Resource for Quality of Care Research. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):641–650. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3162-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen RM. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does it Matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1. doi: 10.2307/2137284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venkatesh AK, Mei H, Kocher KE, et al. Identification of Emergency Department Visits in Medicare Administrative Claims: Approaches and Implications. Meisel ZF, ed. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(4):422–431. doi: 10.1111/acem.13140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer DK, Travers D, Wyss A, Leak A, Waller A. Why Do Patients With Cancer Visit Emergency Departments? Results of a 2008 Population Study in North Carolina. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(19):2683–2688. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The CAHPS Program. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Published October 2018. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/cahps-program/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 15.CAHPS Surveys and Guidance. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Published October 2018. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Institute. Site Recode ICD-O-3. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Published 2019. Accessed February 25, 2019. https://seer.cancer.gov/siterecode/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00256-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute. Case-Mix Adjustment Guidance for SEER-CAHPS Analyses. Published 2020. Accessed January 20, 2020. https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seer-cahps/researchers/adjustment_guidance.html

- 19.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338(June29 January ):b2393–b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Survey Instruments and Specifications. Medicare Advantage and Prescription Drug Plan CAHPS Survey. Published 2020. Accessed April 22, 2020. https://ma-pdpcahps.org/en/survey-instruments-and-specifications/

- 21.Wong TH, Lau ZY, Ong WS, et al. Cancer patients as frequent attenders in emergency departments: A national cohort study. Cancer Med. 2018;7(9):4434–4446. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryant AL, Deal AM, Walton A, Wood WA, Muss H, Mayer DK. Use of ED and hospital services for patients with acute leukemia after induction therapy: One year follow-up. Leuk Res. 2015;39(4):406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flowers CR, Seidenfeld J, Bow EJ, et al. Antimicrobial Prophylaxis and Outpatient Management of Fever and Neutropenia in Adults Treated for Malignancy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31 (6):794–810. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.8661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, et al. The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer Risk Index: A Multinational Scoring System for Identifying Low-Risk Febrile Neutropenic Cancer Patients. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(16):3038–3051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.16.3038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oncology Nursing Society. How Oncology Nurses Provide Quality Care Through Telephone Triage. ONS Voice. Published 2018. Accessed March 17, 2020. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/how-oncology-nurses-provide-quality-care-through-telephone-triage [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mollica MA, Weaver KE, McNeel TS, Kent EE. Examining urban and rural differences in perceived timeliness of care among cancer patients: A SEER-CAHPS study: Patient Experiences: Urban vs Rural. Cancer. 2018;124(15):3257–3265. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halpern MT, Urato MP, Kent EE. The health care experience of patients with cancer during the last year of life: Analysis of the SEER-CAHPS data set: Health Care Ratings in Last Year of Life. Cancer. 2017;123(2):336–344. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Emergency Department Patient Experiences with Care (EDPEC) Survey. Published 2020. Accessed March 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/CAHPS/ED

- 29.Melnyk B, Morrison-Beedy D, eds. Intervention Research: Designing, Conducting, Analyzing, and Funding. Springer; Pub; 2012. [Google Scholar]