Summary

Quantitative comparison of microbial composition from different populations is a fundamental task in various microbiome studies. We consider two-sample testing for microbial compositional data by leveraging phylogenetic information. Motivated by existing phylogenetic distances, we take a minimum-cost flow perspective to study such testing problems. We first show that multivariate analysis of variance with permutation using phylogenetic distances, one of the most commonly used methods in practice, is essentially a sum-of-squares type of test and has better power for dense alternatives. However, empirical evidence from real datasets suggests that the phylogenetic microbial composition difference between two populations is usually sparse. Motivated by this observation, we propose a new maximum type test, detector of active flow on a tree, and investigate its properties. We show that the proposed method is particularly powerful against sparse phylogenetic composition difference and enjoys certain optimality. The practical merit of the proposed method is demonstrated by simulation studies and an application to a human intestinal biopsy microbiome dataset on patients with ulcerative colitis.

Keywords: Microbiome, Metagenomics, Phylogenetic tree, Sparse alternative, Wasserstein distance

1. Introduction

High-throughput sequencing technologies make it possible to survey the microbiome communities from multiple samples, resulting in a need for statistical methods to quantitatively compare samples from different populations/experiments. Testing whether two groups of samples have the same microbiome composition is a key step in deciphering the quantitative difference between populations and identifying the dysbiotic components. In this paper we consider two-sample testing for the means of relative abundance from two populations. Although the problem is mainly motivated by microbiome and metagenomic data analysis, as a general problem it also arises in other high-throughput sequencing data, e.g., single-cell RNA sequencing data.

The microbial community from one sample is usually represented by discrete distributions with the relative abundance of microbe species organized in taxonomy, or operational taxonomic units in some applications. To assess the quantitative difference between groups of samples, various methods have been proposed for the taxonomic compositional data, including global two-sample tests (Zhao et al., 2015; Cao et al., 2017) and differential abundance tests (Robinson et al., 2010; Wagner et al., 2011; Love et al., 2014; Mandal et al., 2015). These methods, however, neglect the degree of similarity between microbe species, due to the fact that the analysis units in these methods, microbe species, are implicitly assumed to be equally distinct (Fukuyama, 2017). Furthermore, the classification of microbes by contemporary microbial taxonomy is coarse, which results in loss of power to detect subtle difference in a higher resolution (Washburne et al., 2018). To alleviate these issues, the phylogeny of the bacterial species is usually incorporated into the analyses of microbiome data (Fukuyama, 2017; Washburne et al., 2018).

In order to capture the phylogenetic compositional difference of the microbes between populations, one of the most widely used two-sample testing methods is multivariate analysis of variance with permutation, permanova, equipped with phylogenetic distance (McArdle & Anderson, 2001; Anderson, 2014; Xia & Sun, 2017). In microbiome data analysis, the popular choices of phylogenetic distances include the unweighted or weighted UniFrac distances (Lozupone & Knight, 2005; Lozupone et al., 2007) and their  Zolotarev-type generalized variants (Evans & Matsen, 2012). Through studying these phylogenetic composition distances, we show that they are closely related to a minimum-cost flow problem for the underlying phylogenetic tree, and the phylogenetic composition difference between samples can be fully characterized by the optimal flow at each edge. Motivated by this observation, we consider the optimal flow at each edge as the analysis unit, instead of each microbe species. The main goal of the present paper is to study the problem of two-sample testing on a phylogenetic tree from this minimum-cost flow perspective.

Zolotarev-type generalized variants (Evans & Matsen, 2012). Through studying these phylogenetic composition distances, we show that they are closely related to a minimum-cost flow problem for the underlying phylogenetic tree, and the phylogenetic composition difference between samples can be fully characterized by the optimal flow at each edge. Motivated by this observation, we consider the optimal flow at each edge as the analysis unit, instead of each microbe species. The main goal of the present paper is to study the problem of two-sample testing on a phylogenetic tree from this minimum-cost flow perspective.

We first investigate permanova equipped with  Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance. Due to its flexibility and ease of computation, permanova using phylogenetic distance has been applied in a wide range of microbiome studies (Smith et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016), but it still lacks theoretical justification. Following the minimum-cost flow perspective, we show that permanova is essentially a sum-of-squares type of test, which has been widely used to test the difference between the means of two populations in high-dimensional problems (Bai & Saranadasa, 1996; Srivastava & Du, 2008; Chen & Qin, 2010). We establish its asymptotic normality under the null hypothesis, and show that its power is indeed determined by the phylogenetic distance between the group means. It is known that sum-of-squares type tests are effective in detecting the dense alternatives, but not powerful against sparse alternatives (Cai et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2019). However, in most microbiome studies, only a small fraction of taxa may have different mean abundances (Cao et al., 2017), resulting in optimal flows on a small number of edges that are active, i.e., nonzero. Moreover, permanova, as a global method, is not able to identify the specific locations of the significant differences even when the null hypothesis is rejected. Therefore, there is a need for a more powerful and interpretable test to detect sparse phylogenetic composition difference between two populations.

Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance. Due to its flexibility and ease of computation, permanova using phylogenetic distance has been applied in a wide range of microbiome studies (Smith et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016), but it still lacks theoretical justification. Following the minimum-cost flow perspective, we show that permanova is essentially a sum-of-squares type of test, which has been widely used to test the difference between the means of two populations in high-dimensional problems (Bai & Saranadasa, 1996; Srivastava & Du, 2008; Chen & Qin, 2010). We establish its asymptotic normality under the null hypothesis, and show that its power is indeed determined by the phylogenetic distance between the group means. It is known that sum-of-squares type tests are effective in detecting the dense alternatives, but not powerful against sparse alternatives (Cai et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2019). However, in most microbiome studies, only a small fraction of taxa may have different mean abundances (Cao et al., 2017), resulting in optimal flows on a small number of edges that are active, i.e., nonzero. Moreover, permanova, as a global method, is not able to identify the specific locations of the significant differences even when the null hypothesis is rejected. Therefore, there is a need for a more powerful and interpretable test to detect sparse phylogenetic composition difference between two populations.

To fill this need we introduce a new test, detector of active flow on the tree, dafot, to detect the sparse phylogenetic composition difference between two populations. To detect sparse signals, the maximum type statistics are usually adopted in various settings because of their simplicity, effectiveness and optimality (see, e.g., Dümbgen & Spokoiny, 2001; Arias-Castro et al., 2005; Jeng et al., 2010; Arias-Castro et al., 2011; Cai et al., 2014, and references therein). Motivated by this, we construct dafot as the maximum of the standardized statistics for optimal flow at each edge. When the null hypothesis is rejected by dafot, it is also able to identify the edges that the active optimal flows lie on. Thus, different from permanova, dafot can not only detect the difference, it is also able to identify the branches of the phylogenetic tree that show difference in relative abundance between the populations. It is shown that dafot is the minimax optimal test against sparse alternatives, and the optimal detection boundary of phylogenetic composition difference relies on both the structure of phylogenetic tree and heteroskedastic variance of microbe species. The practical merits of dafot are further demonstrated through a real data example. The method is implemented in the R package DAFOT available from CRAN (R Development Core Team, 2021).

Transformation of compositional data is often employed in order to account for the compositional nature of the data. For example, the centred log-ratio transformation is one of the commonly used transformation methods for analysis of compositional data (Aitchison, 1982). To account for possible data transformation, we introduce  -generalized optimal flow for any given strictly increasing transformation function

-generalized optimal flow for any given strictly increasing transformation function  defined on

defined on  . The original form of optimal flow corresponds to the special case with

. The original form of optimal flow corresponds to the special case with  . Another special case of

. Another special case of  -generalized optimal flow is the difference of balance between populations (Egozcue & Pawlowsky-Glahn, 2016; Rivera-Pinto et al., 2018), when

-generalized optimal flow is the difference of balance between populations (Egozcue & Pawlowsky-Glahn, 2016; Rivera-Pinto et al., 2018), when  , equivalent to adopting centred log-ratio transformation. After introducing this new concept, we show that all the methodology and theory discussed previously can be generalized accordingly.

, equivalent to adopting centred log-ratio transformation. After introducing this new concept, we show that all the methodology and theory discussed previously can be generalized accordingly.

2. A hierarchical model for microbiome count data and phylogenetic distance

The human microbiome can be quantified using 16S rRNA sequencing or shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Such 16S rRNA gene sequences of the bacterial genomes or the sequencing of evolutionarily conserved universal marker genes can be used to construct the phylogenetic tree of the bacterial species. The microbe species and their ancestors are usually organized in such a phylogenetic tree based on their evolutionary relationships. Let  be the phylogenetic tree of microbe species. Here,

be the phylogenetic tree of microbe species. Here,  is the collection of microbe species and their ancestors, and

is the collection of microbe species and their ancestors, and  represents the collection of edges of the phylogenetic tree

represents the collection of edges of the phylogenetic tree  . For any

. For any  ,

,  is the corresponding branch length. We assume the phylogenetic tree is rooted at

is the corresponding branch length. We assume the phylogenetic tree is rooted at  , which can be seen as the common ancestor of all microbe species. For any pair of nodes

, which can be seen as the common ancestor of all microbe species. For any pair of nodes  , the unique shortest path between them is denoted by

, the unique shortest path between them is denoted by  and the corresponding distance between them is defined as

and the corresponding distance between them is defined as

|

(1) |

The dissimilarity between two microbe species  and

and  can thus be quantified by

can thus be quantified by  . The height of the tree is then defined as the maximum of the distances between the root and the other nodes of the tree,

. The height of the tree is then defined as the maximum of the distances between the root and the other nodes of the tree,  .

.

The relative abundance of a microbial community can be represented by a discrete distribution on the nodes of the tree  . More specifically, write all possible discrete distributions on

. More specifically, write all possible discrete distributions on  as

as

|

Here,  is the relative abundance of microbial species

is the relative abundance of microbial species  and

and  is a simplex of

is a simplex of  dimension, where

dimension, where  is the number of elements. Suppose there are two populations of interest on

is the number of elements. Suppose there are two populations of interest on  , e.g., treated and control groups. These two populations can be represented by two probability distributions on

, e.g., treated and control groups. These two populations can be represented by two probability distributions on  ,

,  and

and  , respectively. We are interested in comparing the mean of the relative abundance between these two populations,

, respectively. We are interested in comparing the mean of the relative abundance between these two populations,

|

(2) |

where  is the mean of

is the mean of  ,

,

|

The covariance matrix of  is defined similarly:

is defined similarly:

|

To test the mean equality hypothesis,  and

and  samples are drawn from each of the two populations,

samples are drawn from each of the two populations,

|

However, the true relative abundance of each sample,  ,

,  ,

,  , is unknown in practice. Sequencing of the microbial DNAs is used to assess the relative abundance of the microbes in the sample. In microbiome studies, the sequencing read data can be modelled by a Poisson distribution. To be specific, the number of sequencing reads

, is unknown in practice. Sequencing of the microbial DNAs is used to assess the relative abundance of the microbes in the sample. In microbiome studies, the sequencing read data can be modelled by a Poisson distribution. To be specific, the number of sequencing reads  that can be assigned to species

that can be assigned to species  from the

from the  th sample of the

th sample of the  th group is assumed to follow a Poisson distribution,

th group is assumed to follow a Poisson distribution,

|

where  is the total number of reads in the

is the total number of reads in the  th sample of the

th sample of the  th group and

th group and  is the relative abundance of microbe species

is the relative abundance of microbe species  in sample

in sample  . Thus, the reads count is assumed to be drawn from the hierarchical model

. Thus, the reads count is assumed to be drawn from the hierarchical model

|

for any  ,

,  ,

,  . The goal of this paper is to test the hypothesis in (2) based on the count data

. The goal of this paper is to test the hypothesis in (2) based on the count data  .

.

Following this hierarchical model, the empirical distribution of each  is written as

is written as  . Due to the hierarchical structure of the model, the covariance matrix of empirical distribution

. Due to the hierarchical structure of the model, the covariance matrix of empirical distribution  is

is

|

Here,  represents the diagonal matrix of a vector. It is clear that the covariance matrix of the empirical distribution depends on both the mean and covariance matrix of

represents the diagonal matrix of a vector. It is clear that the covariance matrix of the empirical distribution depends on both the mean and covariance matrix of  , and the variance of the empirical distribution is inflated because of the sequencing steps. The difference between

, and the variance of the empirical distribution is inflated because of the sequencing steps. The difference between  and

and  vanishes when

vanishes when  goes to infinity. For simplicity of analysis, in the rest of the paper we always assume the total number of reads in each sample to be equal, i.e.,

goes to infinity. For simplicity of analysis, in the rest of the paper we always assume the total number of reads in each sample to be equal, i.e.,  for any

for any  ,

,  . For brevity, we write

. For brevity, we write  when

when  and

and  . We also assume that there exists

. We also assume that there exists  such that

such that

|

(3) |

This assumption implies that the proportion of the samples from either population does not vanish. We write  .

.

In microbiome studies, a phylogenetic distance that reflects the evolution relationships among microbe species is often used in defining the distance between two microbial communities. Examples include unweighted and weighted UniFrac distance (Lozupone & Knight, 2005; Lozupone et al., 2007). As shown in Evans & Matsen (2012), the weighted UniFrac distance is a plugin estimator of the Wasserstein distance of probability masses on the tree, which can be generalized to  Zolotarev-type variants; for brevity, we call them

Zolotarev-type variants; for brevity, we call them  Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance. In the present paper we focus on the

Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance. In the present paper we focus on the  Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance

Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance

|

(4) |

where  is the total probability of all descendants of edge

is the total probability of all descendants of edge  ,

,

|

where  and

and  is a subtree below edge

is a subtree below edge  :

:  . We also use the following notation:

. We also use the following notation:

|

3. A minimum-cost flow perspective for two-sample testing

The phylogenetic distance between two discrete distributions is closely related to optimal transport theory (Evans & Matsen, 2012). To be specific, the weighted UniFrac/Wasserstein distance between  and

and  is equal to the solution of the following optimal transport problem:

is equal to the solution of the following optimal transport problem:

|

(5) |

Here, the objective function is the total cost of transport  , and

, and  is the cost per unit transported from

is the cost per unit transported from  to

to  .

.

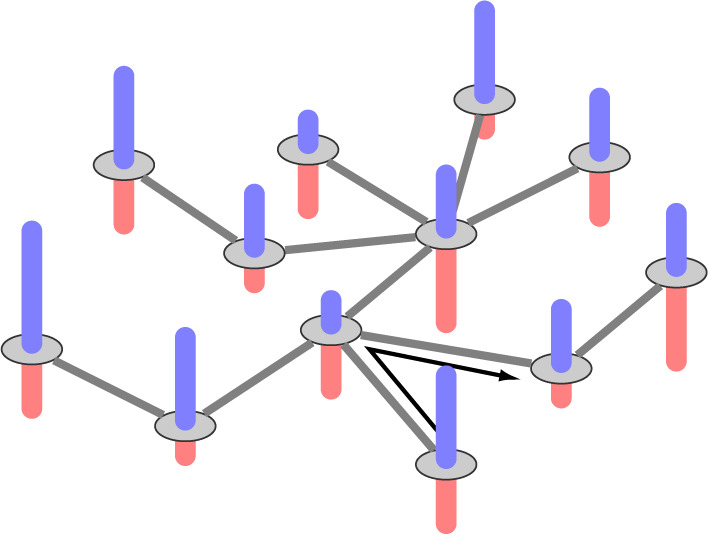

Different from the general optimal transport problem, the distance  in (1) is defined as the geodesic distance along the path

in (1) is defined as the geodesic distance along the path  on tree

on tree  . Therefore, this optimal transport problem can be naturally cast as a minimum-cost flow problem on a network, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The tree

. Therefore, this optimal transport problem can be naturally cast as a minimum-cost flow problem on a network, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The tree  can be seen as a special network, and there is a source with capacity

can be seen as a special network, and there is a source with capacity  and a sink with capacity

and a sink with capacity  at each node

at each node  . Then, the optimization problem in (5) aims to find a way with the minimum cost of sending an amount of flow from sources to sinks through the network

. Then, the optimization problem in (5) aims to find a way with the minimum cost of sending an amount of flow from sources to sinks through the network  . In particular, for any given transport

. In particular, for any given transport  , define the flows on each edge as

, define the flows on each edge as

|

Figure 1.

An illustration of the minimum-cost flow problem on the tree. The blue bars are the source and the red bars are the sink.

Here,  is the flow through edge

is the flow through edge  towards the root

towards the root  , and

, and  is the flow through edge

is the flow through edge  in the opposite direction. Then, the optimization problem in (5) can be reformulated as

in the opposite direction. Then, the optimization problem in (5) can be reformulated as

|

(6) |

Although the optimal transport  in (5) might not be unique, the optimal flow in (6) is unique and has the closed-form solution

in (5) might not be unique, the optimal flow in (6) is unique and has the closed-form solution

|

The optimal net flow on each edge is then defined as  . The weighted UniFrac distance and corresponding

. The weighted UniFrac distance and corresponding  Zolotarev-type variants can thus be seen as the weighted

Zolotarev-type variants can thus be seen as the weighted  norm of optimal flows. It is clear from the above discussion that the phylogenetic composition difference between

norm of optimal flows. It is clear from the above discussion that the phylogenetic composition difference between  and

and  can be fully characterized by the optimal flow

can be fully characterized by the optimal flow  . If we write

. If we write  , the hypothesis in (2) can be rewritten in the equivalent form

, the hypothesis in (2) can be rewritten in the equivalent form

|

This suggests that the basic unit to quantify phylogenetic composition difference shall be the optimal flow at each edge  . The

. The  Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance

Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance  can be seen as the

can be seen as the  norm of these optimal flows.

norm of these optimal flows.

4. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance

4.1. Introduction

To incorporate phylogenetic tree information in comparing two populations, one of the most commonly used two-sample tests is permanova equipped with some phylo-genetic distance (McArdle & Anderson, 2001; Anderson, 2014). Specifically, let  be the phylogenetic distance defined in (4). The average empirical distances within and between groups are defined as

be the phylogenetic distance defined in (4). The average empirical distances within and between groups are defined as

|

and

|

Similar to analysis of variance, permanova defines the total sum-of-squares as

|

and the within-group sum-of-squares and between-group sum-of-squares as

|

The pseudo  -statistic for two-sample testing is then defined as the normalized ratio of

-statistic for two-sample testing is then defined as the normalized ratio of  to

to  ,

,

|

To evaluate the significance of the  -statistic, its

-statistic, its  -value is calculated by permutations. To be more specific, the

-value is calculated by permutations. To be more specific, the  samples are permuted randomly

samples are permuted randomly  times and the

times and the  -statistic calculated on each of these permuted data, denoted

-statistic calculated on each of these permuted data, denoted  . Then, the estimated

. Then, the estimated  -value is

-value is

|

One implicit assumption of a valid permutation test is the exchangeability of samples under the null hypothesis. Thus, the hypothesis required by a valid permutation test is

|

Compared with the mean equality hypothesis in (2), this is a more restrictive hypothesis. In the next section we present another way to estimate the  -value of permanova based on the asymptotic results.

-value of permanova based on the asymptotic results.

4.2. Properties

We investigate the properties of the pseudo  -statistic under the

-statistic under the  Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance

Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance  . A simple calculation decomposes

. A simple calculation decomposes  into two parts:

into two parts:

|

In particular, the second term is asymptotically equal to  ,

,

|

This shows that  is a scaled version of the difference between the average within-group distance and the across-group distance. In other words, in terms of two-sample testing,

is a scaled version of the difference between the average within-group distance and the across-group distance. In other words, in terms of two-sample testing,  is asymptotically equivalent to the following energy distance statistic (Székely & Rizzo, 2005; Sejdinovic et al., 2013):

is asymptotically equivalent to the following energy distance statistic (Székely & Rizzo, 2005; Sejdinovic et al., 2013):

|

Due to the fact that the distance in (4) is a negative type, the energy distance statistic can also be written as a kernel-based test statistic (Sejdinovic et al., 2013),

|

where the kernel of  and

and  is defined as

is defined as  . The kernel form of permanova suggests

. The kernel form of permanova suggests

|

Therefore, the  statistic in permanova is a reasonable statistic for testing the phylogenetic composition difference in hypothesis (2), as the mean of

statistic in permanova is a reasonable statistic for testing the phylogenetic composition difference in hypothesis (2), as the mean of  only depends on

only depends on  and

and  .

.

Clearly, the behaviour of  depends on both the covariance matrix of

depends on both the covariance matrix of  and the tree structure

and the tree structure  . The structure of the tree

. The structure of the tree  can be expressed as a transformation matrix

can be expressed as a transformation matrix  , where

, where  if

if  and

and  if

if  . We assume

. We assume

|

(7) |

where  or

or  . Such a moment assumption is a common condition in high-dimension statistics, e.g., condition (3.6) in Chen & Qin (2010). Condition (7) is true when the eigenvalues of both

. Such a moment assumption is a common condition in high-dimension statistics, e.g., condition (3.6) in Chen & Qin (2010). Condition (7) is true when the eigenvalues of both  and

and  are bounded. Besides the assumption of the moment, another assumption we make is

are bounded. Besides the assumption of the moment, another assumption we make is

|

(8) |

where  and

and  are empirical distributions drawn from the first or second population, and

are empirical distributions drawn from the first or second population, and  is a sequence of numbers such that

is a sequence of numbers such that  . This is a fairly weak condition. For example, it is a trivial assumption when the tree is not too high, i.e.,

. This is a fairly weak condition. For example, it is a trivial assumption when the tree is not too high, i.e.,  , because

, because  .

.

The following theorem shows the asymptomatic behaviour of the permanova statistic  .

.

Theorem 1.

Under the null hypothesis, i.e.,

, and assumptions (3), (7) and (8),

where

can be written as

Furthermore, if

and assumptions (3), (7) and (8) hold, the test is consistent when

(9)

This theorem suggests that permanova is a consistent test if the phylogenetic distance between the means of two populations is large enough. As  can be written explicitly as

can be written explicitly as

|

the power of permanova depends on both the number of samples  and the number of reads per sample

and the number of reads per sample  . The power becomes larger if we increase either

. The power becomes larger if we increase either  or

or  . However, (9) also suggests that a larger number of samples is a more efficient way to increase power than a larger number of reads per sample. This theorem also suggests that the

. However, (9) also suggests that a larger number of samples is a more efficient way to increase power than a larger number of reads per sample. This theorem also suggests that the  -value can be calculated based on asymptomatic distribution instead of conducting permutations. For instance,

-value can be calculated based on asymptomatic distribution instead of conducting permutations. For instance,  can be estimated based on a similar

can be estimated based on a similar  -statistic,

-statistic,  in Chen & Qin (2010). Then, the

in Chen & Qin (2010). Then, the  -value can be calculated by

-value can be calculated by  . This way of calculating the

. This way of calculating the  -value does not require

-value does not require  under the null hypothesis. In practice, we recommend the permutation test when

under the null hypothesis. In practice, we recommend the permutation test when  is not large and the asymptotic critical value of

is not large and the asymptotic critical value of  is large.

is large.

4.3. Sparse setting

As we have seen in previous sections, permanova is a sum-of-squares type statistic. However, the interesting setting in practice, e.g., in microbiome studies, is a sparse case where only a small number of microbe species may have different relative mean abundance (Cao et al., 2017). This suggests that only a small fraction of optimal flow  is active, i.e.,

is active, i.e.,  . To investigate the performance of permanova under this sparse setting, we consider a simple case where there is active optimal flow on one edge, denoted by

. To investigate the performance of permanova under this sparse setting, we consider a simple case where there is active optimal flow on one edge, denoted by  . As suggested by Theorem 1, the condition for a consistent permanova test is

. As suggested by Theorem 1, the condition for a consistent permanova test is

|

On the other hand, we consider an oracle test that has knowledge of the active flow location  . Since the location of

. Since the location of  is known, we consider a two-sample

is known, we consider a two-sample  -test for

-test for  ,

,

|

(10) |

where

|

With the central limit theorem, we know that  is a consistent test if

is a consistent test if

|

A comparison of the two detection boundaries indicates that the oracle test is able to detect a much smaller difference between two groups of samples than permanova. This naturally leads to the question of whether it is possible to develop a more powerful test under the sparse flow setting.

5. Active optimal flow detection

5.1. Detector of active flow on the tree

As shown in § 4, the two-sample  -test could improve the power to detect the difference between two populations when the location of the active optimal flow is known. In practice, the location information is usually unknown. To address this issue we consider the maximum of the two-sample

-test could improve the power to detect the difference between two populations when the location of the active optimal flow is known. In practice, the location information is usually unknown. To address this issue we consider the maximum of the two-sample  -tests at each edge,

-tests at each edge,

|

where  is defined in the same way as (10). The use of this maximum type statistic for detecting sparse signals is very common in a wide range of applications, leading to the construction of rate-optimal tests for many problems (Dümbgen & Spokoiny, 2001; Arias-Castro et al., 2005; Arias-Castro et al., 2011; Jeng et al., 2010; Cai et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021).

is defined in the same way as (10). The use of this maximum type statistic for detecting sparse signals is very common in a wide range of applications, leading to the construction of rate-optimal tests for many problems (Dümbgen & Spokoiny, 2001; Arias-Castro et al., 2005; Arias-Castro et al., 2011; Jeng et al., 2010; Cai et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021).

To evaluate the statistical significance of  , one still needs to choose an appropriate critical value for

, one still needs to choose an appropriate critical value for  . However, it is difficult to derive the asymptotic distribution of

. However, it is difficult to derive the asymptotic distribution of  due to the complex dependency structure among the

due to the complex dependency structure among the  . To overcome this problem, one adopts a resampling method to assign an appropriate critical value for

. To overcome this problem, one adopts a resampling method to assign an appropriate critical value for  . In particular, a common resampling method to choose a critical value is the permutation test as in permanova (Good, 2013; Anderson, 2014). Although the permutation test requires

. In particular, a common resampling method to choose a critical value is the permutation test as in permanova (Good, 2013; Anderson, 2014). Although the permutation test requires  under the null hypothesis as we discussed before, its performance is robust when the sample size is small.

under the null hypothesis as we discussed before, its performance is robust when the sample size is small.

We propose another resampling method, the bootstrap, to choose the critical value for  in order to avoid the condition

in order to avoid the condition  . Let

. Let  for

for  ,

,  , where

, where  is the mean of

is the mean of  within each group and

within each group and  is the mean of the combined samples. We randomly draw

is the mean of the combined samples. We randomly draw  samples with replacement from each group and then calculate

samples with replacement from each group and then calculate  with shifted data

with shifted data  . This procedure is repeated

. This procedure is repeated  times and the corresponding statistics are denoted by

times and the corresponding statistics are denoted by  . Finally, the approximated

. Finally, the approximated  is chosen as a

is chosen as a  quantile of the empirical distribution of

quantile of the empirical distribution of  , or the

, or the  -value is calculated as

-value is calculated as

|

We then make a decision under the null hypothesis based on the critical value or the  -value.

-value.

When the null hypothesis is rejected,  also provides a natural way to identify the set of edges with their optimal flow not being zero,

also provides a natural way to identify the set of edges with their optimal flow not being zero,  . To be specific, we consider the set of edges

. To be specific, we consider the set of edges  as the active edges identified. Due to the construction of

as the active edges identified. Due to the construction of  , the familywise error rate of active edge identification is naturally controlled at the

, the familywise error rate of active edge identification is naturally controlled at the  level. The identified edge indicates that all microbe species below this edge, as a whole object, are differentially abundant between the two populations. In this way, the active edges are identified as a microbial signature associated with the difference of the two populations.

level. The identified edge indicates that all microbe species below this edge, as a whole object, are differentially abundant between the two populations. In this way, the active edges are identified as a microbial signature associated with the difference of the two populations.

5.2. Asymptotic behaviour and optimality of

We now investigate the behaviour of  under the null and alternative hypothesis. The main difficulty in studying the behaviour of

under the null and alternative hypothesis. The main difficulty in studying the behaviour of  is the strong and complex dependence among different

is the strong and complex dependence among different  . This complexity of the dependency structure mainly comes from two sources: the high overlapping structure of the subtree

. This complexity of the dependency structure mainly comes from two sources: the high overlapping structure of the subtree  and the unknown heteroskedastic variance/covariance structure among the different microbe species. Our investigation shows that the complexity of the the dependence structure among the

and the unknown heteroskedastic variance/covariance structure among the different microbe species. Our investigation shows that the complexity of the the dependence structure among the  can be characterized by a single quantity that depends on both the tree structure and the heteroskedastic variance.

can be characterized by a single quantity that depends on both the tree structure and the heteroskedastic variance.

Since each  is defined on a subtree below edge

is defined on a subtree below edge  , the asymptotic behaviour of

, the asymptotic behaviour of  clearly depends on the effective number of subtrees. We still assume that each group of samples has no vanishing proportion, i.e., (3). Let

clearly depends on the effective number of subtrees. We still assume that each group of samples has no vanishing proportion, i.e., (3). Let  be the element of the

be the element of the  th row and

th row and  th column of

th column of  . To decouple the complex dependence structure among the

. To decouple the complex dependence structure among the  , we provide the following proposition.

, we provide the following proposition.

Proposition 1.

For any given

, let

be a subset of edges of the tree such that

. Then,

can be decomposed into a collection of disjoint paths

where

and

are nodes of the tree and

is the number of disjoint paths. In addition, any two edges from different paths in the above decomposition do not share any descendants.

Intuitively, for any  and

and  from the same path defined above, the subtrees

from the same path defined above, the subtrees  and

and  are highly overlapped, and thus the

are highly overlapped, and thus the  defined on them are expected to behave similarly. On the other hand, for edges from different paths, the corresponding subtrees are distinct in that they do not share any descendants. In general, the number of disjoint paths in the above proposition characterizes an effective number of subtrees. Motivated by this observation, we define

defined on them are expected to behave similarly. On the other hand, for edges from different paths, the corresponding subtrees are distinct in that they do not share any descendants. In general, the number of disjoint paths in the above proposition characterizes an effective number of subtrees. Motivated by this observation, we define  as the number of different paths in

as the number of different paths in  for

for  , and

, and  as the sum of the

as the sum of the  ,

,

|

Clearly,  is an integer between

is an integer between  and

and  , and depends on the structure of the tree

, and depends on the structure of the tree  and the distributions

and the distributions  and

and  . For example, when the tree

. For example, when the tree  is a fully balanced binary tree, and

is a fully balanced binary tree, and  and

and  are Dirichlet distributions with equal parameters for the leaves,

are Dirichlet distributions with equal parameters for the leaves,  . If

. If  and

and  are Dirichlet distributions with equal parameters for all nodes of a chain tree

are Dirichlet distributions with equal parameters for all nodes of a chain tree  , i.e., a one-dimensional lattice, then

, i.e., a one-dimensional lattice, then  . More specific examples can be found in the Supplementary Material. We later show that the asymptotic behaviour of

. More specific examples can be found in the Supplementary Material. We later show that the asymptotic behaviour of  can be fully characterized by this quantity

can be fully characterized by this quantity  .

.

When two subtrees highly overlap, we expect the correlation between the  on them to be very strong. We shall assume there exist constants

on them to be very strong. We shall assume there exist constants  and

and  such that

such that

|

(11) |

where  ,

,  and

and  are a pair of edges such that

are a pair of edges such that  . Here,

. Here,  represents the correlation between two random variables. This is not a strong condition. For instance, (11) is satisfied when the relative abundance of different microbe species

represents the correlation between two random variables. This is not a strong condition. For instance, (11) is satisfied when the relative abundance of different microbe species  in

in  are mutually independent or drawn from a Dirichlet distribution. Furthermore, we also assume that

are mutually independent or drawn from a Dirichlet distribution. Furthermore, we also assume that  is a sub-Gaussian distribution, i.e., there exist constants

is a sub-Gaussian distribution, i.e., there exist constants  and

and  such that

such that

|

(12) |

where  is the variance of

is the variance of  , the element of the

, the element of the  th row and the

th row and the  th column of

th column of  . The following theorem shows the asymptotic behaviour of

. The following theorem shows the asymptotic behaviour of  under the null hypothesis.

under the null hypothesis.

Theorem 2.

Suppose

. Under the null hypothesis and assumptions (3), (11) and (12), we have

(13)

Theorem 2 suggests that the amplitude of  is

is  when the null hypothesis is true, where

when the null hypothesis is true, where  plays the same role as the number of variables when all the components are almost independent (Cai et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2017). In other words, although

plays the same role as the number of variables when all the components are almost independent (Cai et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2017). In other words, although  is constructed from

is constructed from  different subtrees, it is equivalent to taking a maximum of roughly

different subtrees, it is equivalent to taking a maximum of roughly  independent variables because of the high dependency among the statistics

independent variables because of the high dependency among the statistics  . For the one active flow example discussed in the previous section, Theorem 2 suggests that

. For the one active flow example discussed in the previous section, Theorem 2 suggests that  is a consistent test when

is a consistent test when

|

A comparison between the above and the oracle test’s detection boundary suggests that the price we pay for the unknown location of  is

is  . With the same argument as for permanova, we know that either a larger number of samples

. With the same argument as for permanova, we know that either a larger number of samples  or a larger number of reads per sample

or a larger number of reads per sample  can increase the power of dafot. More detailed discussions are given in § 6.

can increase the power of dafot. More detailed discussions are given in § 6.

We next turn to the power analysis of the test based on  from a minimax point of view (Ingster 1993a, b,c; Ingster & Suslina, 2012). The parameter space of the null hypothesis is

from a minimax point of view (Ingster 1993a, b,c; Ingster & Suslina, 2012). The parameter space of the null hypothesis is

|

and the parameter space of the alternative hypothesis is

|

The worst-case risk of any given test  is then defined as

is then defined as

|

We say a test  is consistent for separating

is consistent for separating  and

and  if

if  , and

, and  and

and  are separable if there exists a consistent test

are separable if there exists a consistent test  for them. On the other hand, a test

for them. On the other hand, a test  is powerless for separating

is powerless for separating  and

and  if

if  , and

, and  and

and  are inseparable if

are inseparable if  . Here,

. Here,  is a parameter to control the distance between

is a parameter to control the distance between  and

and  . Clearly, if

. Clearly, if  is smaller,

is smaller,  and

and  are more difficult to separate. Let

are more difficult to separate. Let  be the test that rejects the null hypothesis if and only if

be the test that rejects the null hypothesis if and only if  for some

for some  . The following theorem characterizes the power of

. The following theorem characterizes the power of  and the separability of

and the separability of  and

and  .

.

Theorem 3.

Consider testing

and

by

. Suppose

, and (3), (11) and (12) hold. Then there exist constants

and

such that

This theorem shows that the optimal rate of detection boundary between  and

and  is

is

|

This optimal rate suggests that the difficulty of this problem is mainly determined by the single quantity  , which relies on both the tree structure and the heteroskedastic variance structure. This theorem also suggests that

, which relies on both the tree structure and the heteroskedastic variance structure. This theorem also suggests that  is minimax rate optimal.

is minimax rate optimal.

6. Numerical experiments

6.1. Simulation studies

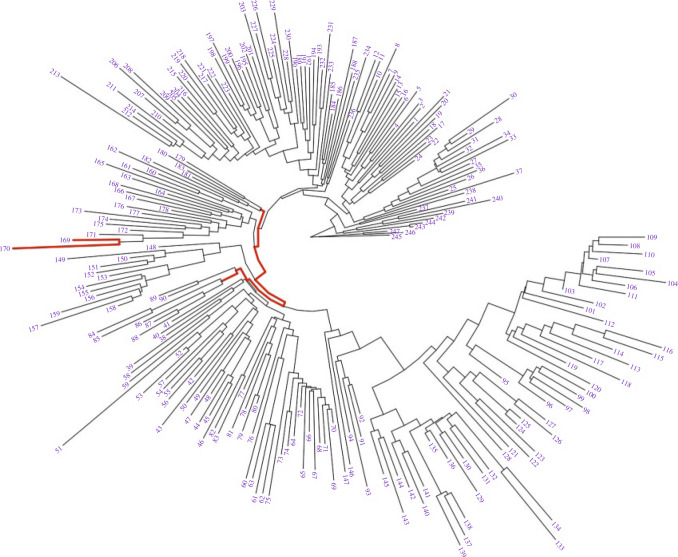

We investigate the properties of permanova and dafot using simulated datasets. We choose a phylogenetic tree of bacteria species within the class Gammaproteobacteria as the underlying tree  . This tree

. This tree  is extracted from the reference tree of the Greengenes 16S rRNA database version 13.8 clustered at 85% similarity by the R package metagenomeFeatures (DeSantis et al., 2006), and has a total of 247 leaves, denoted by

is extracted from the reference tree of the Greengenes 16S rRNA database version 13.8 clustered at 85% similarity by the R package metagenomeFeatures (DeSantis et al., 2006), and has a total of 247 leaves, denoted by  , and 246 internal nodes, denoted by

, and 246 internal nodes, denoted by  . Figure 2 shows the structure of the tree, with each leaf labelled with a number.

. Figure 2 shows the structure of the tree, with each leaf labelled with a number.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of bacteria within the class Gammaproteobacteria used in the simulation studies, with each leaf node labelled with a number. The edges with active optimal flow in the numerical examples are shown in red.

To simulate the numbers of reads on this tree  , we adopt the Dirichlet-multinomial distribution. More specifically, the true relative abundance

, we adopt the Dirichlet-multinomial distribution. More specifically, the true relative abundance  , where

, where  and

and  , is drawn from some Dirichlet distribution, i.e.,

, is drawn from some Dirichlet distribution, i.e.,  follows a Dirichlet distribution indexed by

follows a Dirichlet distribution indexed by  ,

,

|

For each sample, the reads are then drawn from a multinomial distribution with respect to the true relative abundance. Under this model, the mean of the relative abundance for the  th group can be written as

th group can be written as

|

Thus, under the null hypothesis, we assume  if

if  and

and  if

if  . Under the alternative hypothesis, we perturb

. Under the alternative hypothesis, we perturb  and consider two different scenarios: (A) the difference is at nodes

and consider two different scenarios: (A) the difference is at nodes  and

and  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  and

and  ; (B) the difference is at clades

; (B) the difference is at clades  and

and  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  if

if  and

and  if

if  . The parameter

. The parameter  is specified later. In particular, the edges with active optimal flow under scenarios (A) and (B) are shown in red in Fig. 2.

is specified later. In particular, the edges with active optimal flow under scenarios (A) and (B) are shown in red in Fig. 2.

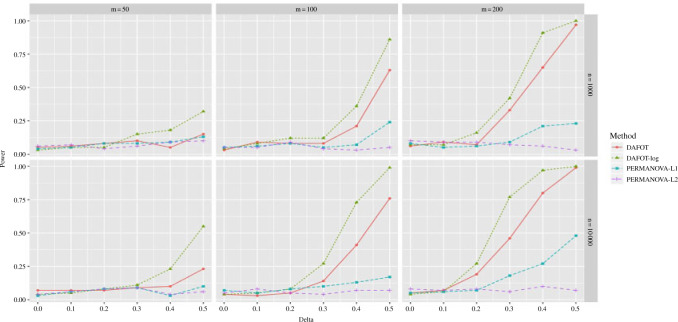

The first set of simulation experiments are designed to compare the performance of dafot and permanova under scenario (A). To be specific, we compare four different methods: dafot; dafot after centre log-ratio transformation (dafot-log); permanova equipped with the weighted UniFrac distance (permanova-L1); and permanova equipped with the  Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance (permanova-L2). To make the comparisons fair, the critical values for all tests are chosen by permutations at a significance level of

Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance (permanova-L2). To make the comparisons fair, the critical values for all tests are chosen by permutations at a significance level of  . To investigate the effect of the sample size

. To investigate the effect of the sample size  , the sequence depth

, the sequence depth  and the signal strength

and the signal strength  , we chose

, we chose  ,

,  and

and  ,

,  and

and  , and

, and  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  in the simulation experiments. The experiment is repeated 100 times for each combination of the

in the simulation experiments. The experiment is repeated 100 times for each combination of the  ,

,  and

and  . The performance of the tests is evaluated by the power of the test, i.e., the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis, which can be estimated by the proportion of null hypothesis rejections among the 100 simulation experiments.

. The performance of the tests is evaluated by the power of the test, i.e., the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis, which can be estimated by the proportion of null hypothesis rejections among the 100 simulation experiments.

The results are summarized in Fig. 3. These results show that the Type I error is under control when the null hypothesis is true,  , and the power of dafot is larger than permanova when the alternative hypothesis is true (

, and the power of dafot is larger than permanova when the alternative hypothesis is true ( ). Figure 3 implies that the observed effects of

). Figure 3 implies that the observed effects of  ,

,  and

and  on the power of the tests are consistent with the theoretical results. We observe a similar improved power of dafot over permanova for scenario (B) when the active flows connect two clades; see the Supplementary Material for details.

on the power of the tests are consistent with the theoretical results. We observe a similar improved power of dafot over permanova for scenario (B) when the active flows connect two clades; see the Supplementary Material for details.

Figure 3.

Power comparisons between dafot and permanova under scenario (A), where the difference is at nodes  and

and  . dafot, the proposed method based on proportions; dafot-log, the proposed method based on log-proportions permanova-L1, permanova with the

. dafot, the proposed method based on proportions; dafot-log, the proposed method based on log-proportions permanova-L1, permanova with the  Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance; permanova-L2, permanova with the

Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance; permanova-L2, permanova with the  Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance.

Zolotarev-type phylogenetic distance.

The sequence count data in real microbiome studies are usually very sparse, i.e., there are a lot of zero values. The next set of simulation experiments are designed to assess the performance of dafot and permanova when there are a lot of zero values. More concretely, we set  for

for  under scenario (A) and for

under scenario (A) and for  under scenario (B). In other words, the probability on nearly

under scenario (B). In other words, the probability on nearly  of the nodes is zero in scenario (A), and the probability on nearly

of the nodes is zero in scenario (A), and the probability on nearly  of the nodes is zero in scenario (B). In order to avoid undefined values of

of the nodes is zero in scenario (B). In order to avoid undefined values of  , zero counts are replaced by

, zero counts are replaced by  in dafot-log (Aitchison, 2003; Lin et al., 2014). The sequence depth of each sample is drawn uniformly between

in dafot-log (Aitchison, 2003; Lin et al., 2014). The sequence depth of each sample is drawn uniformly between  and

and  instead of being fixed as in previous experiments. The sample size

instead of being fixed as in previous experiments. The sample size  and the difference between populations

and the difference between populations  are varied in the same way as in the previous simulation experiments. We present the results based on 100 runs for each combination of

are varied in the same way as in the previous simulation experiments. We present the results based on 100 runs for each combination of  and

and  in the Supplementary Material. A comparison suggests that dafot, permanova-L1 and permanova-L2 are relatively robust against a lot of zero values; however, the power of dafot-log is affected by these zero values.

in the Supplementary Material. A comparison suggests that dafot, permanova-L1 and permanova-L2 are relatively robust against a lot of zero values; however, the power of dafot-log is affected by these zero values.

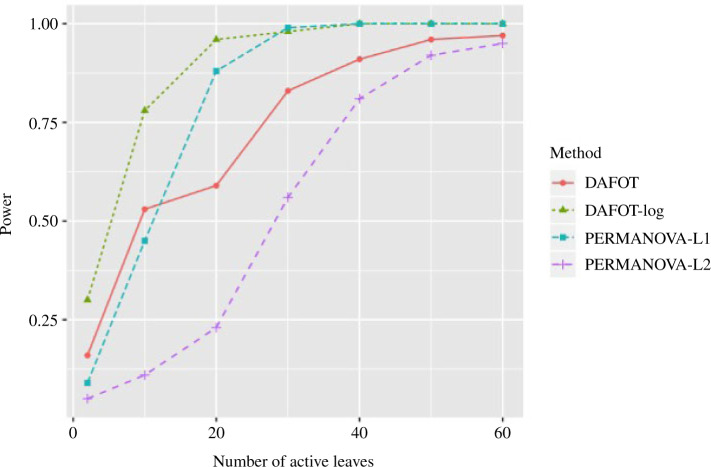

We further compare the performance of dafot and permanova under a wide range of sparseness. Specifically, we adopt a similar setting to scenario (A) and choose  ,

,  and

and  . To assess the effect of sparsity, we randomly choose

. To assess the effect of sparsity, we randomly choose  leaves at each simulation experiment and set

leaves at each simulation experiment and set  for the first

for the first  leaves and

leaves and  for the last

for the last  leaves;

leaves;  is chosen to be

is chosen to be  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  . The results based on 100 simulation experiments are summarized in Fig. 4. These results show that dafot outperforms permanova when fewer leaves are perturbed. When the signal becomes denser, permanova-L1 can gain more power than dafot.

. The results based on 100 simulation experiments are summarized in Fig. 4. These results show that dafot outperforms permanova when fewer leaves are perturbed. When the signal becomes denser, permanova-L1 can gain more power than dafot.

Figure 4.

Power comparisons between dafot and permanova for different sparsity levels.

The final set of simulation experiments aims to evaluate the performance of edge identification by dafot and dafot-log. In particular, we consider scenario (A) with  and vary

and vary  and

and  as in the previous simulation experiments. For each combination of

as in the previous simulation experiments. For each combination of  and

and  , we repeat the experiment 100 times and the active edges detected by the two methods are recorded. The results of the average number of false positive edges, the probability of making at least one Type I error, and the true positive edges are summarized in Table 1, showing that the familywise error rate is under control regardless of signal strength, and that the two active edges can be identified successfully when the signal is strong enough. In Fig. 3 and Table 1, dafot-log performs better than dafot, as the log transformation is suitable for nonzero data.

, we repeat the experiment 100 times and the active edges detected by the two methods are recorded. The results of the average number of false positive edges, the probability of making at least one Type I error, and the true positive edges are summarized in Table 1, showing that the familywise error rate is under control regardless of signal strength, and that the two active edges can be identified successfully when the signal is strong enough. In Fig. 3 and Table 1, dafot-log performs better than dafot, as the log transformation is suitable for nonzero data.

Table 1.

The edge identification performance of dafot and dafot-log

|

|

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| dafot | afp | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.08 | |||

| fwer | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.06 | ||||

| atp | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.56 | 0.78 | 1.49 | 1.66 | ||||

| dafot-log | afp | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.36 | |||

| fwer | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.21 | ||||

| atp | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.90 | 1.35 | 1.81 | 1.94 | ||||

afp, the average number of false positive edges; fwer, the probability of making at least one Type I error; atp, the number of true positive edges.

6.2. Analysis of ulcerative colitis disease microbiome data

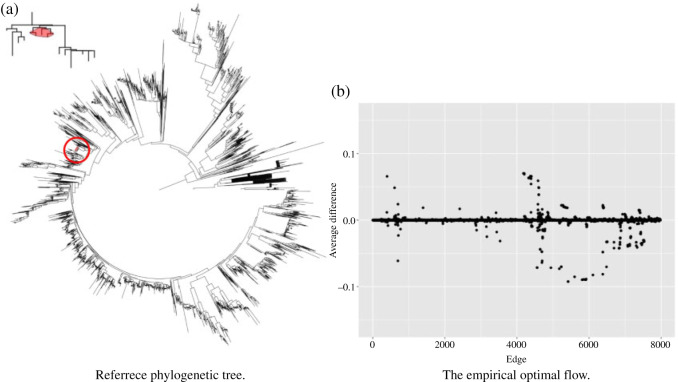

To further demonstrate the performance of dafot, we apply the method to a 16S rRNA dataset of 47 human intestinal biopsy samples collected at the University of Pennsylvania. These samples are divided into three groups: A, 18 control samples (control); B, 14 samples with ulcerative colitis who did not receive treatment (unexposed); C, 15 samples with ulcerative colitis who received treatment (exposed). To compare the microbiome communities of these groups, the raw sequence reads of each sample are placed into a reference phylogenic tree from Greengenes 16S rRNA database version 13.8 with a 99% similarity by using sepp (Mirarab et al., 2012; Janssen et al., 2018). The reference phylogenetic tree is then trimmed by keeping all nodes related to the operational taxonomic units observed in the samples. The trimmed phylogenetic tree is shown in Fig. 5(a), including 7980 edges. Figure 5(b) shows the empirical optimal flow between groups A and B on each edge, i.e., the difference of probability on subtrees indexed by edges,  . The order of the edges is ranked automatically by the R class phylo. It is clear from Fig. 5(b) that most of the empirical active flows are small, indicating that sparse flow on the tree is a reasonable assumption. In addition, we estimate the effective number of subtrees

. The order of the edges is ranked automatically by the R class phylo. It is clear from Fig. 5(b) that most of the empirical active flows are small, indicating that sparse flow on the tree is a reasonable assumption. In addition, we estimate the effective number of subtrees  for pairwise comparison:

for pairwise comparison:  for groups A and B;

for groups A and B;  for groups A and C;

for groups A and C;  for groups B and C. The estimation of

for groups B and C. The estimation of  is based on the reference phylogenetic tree structure and estimated variance

is based on the reference phylogenetic tree structure and estimated variance  at each node

at each node  .

.

Figure 5.

(a) The reference phylogenetic tree used in analysis of intestinal biopsy samples. The branches in red are those identified as an active edge and the zoomed-in subtree below the active edge. (b) The empirical optimal flow between group A and group B on each edge.

To test the phylogenetic composition difference between the groups, we apply the same four two-sample testing methods as in the first simulation experiment. The resulting  -values estimated by a permutation test with 1000 permutations are summarized in Table 2. No methods identify any significant phylogenetic composition difference between groups C and A or groups C and B,

-values estimated by a permutation test with 1000 permutations are summarized in Table 2. No methods identify any significant phylogenetic composition difference between groups C and A or groups C and B,  . However, only dafot indicates an overall difference in intestinal biopsy microbiome composition between groups A and B with

. However, only dafot indicates an overall difference in intestinal biopsy microbiome composition between groups A and B with  , while the other methods do not detect such a difference.

, while the other methods do not detect such a difference.

Table 2.

The  -values for comparing different groups using dafot and permanova based on 1000 permutations

-values for comparing different groups using dafot and permanova based on 1000 permutations

| dafot | dafot-log | permanova-L1 | permanova-L2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A vs B | 0.007 | 0.256 | 0.378 | 0.460 |

| Group A vs C | 0.147 | 0.495 | 0.305 | 0.270 |

| Group B vs C | 0.648 | 0.832 | 0.639 | 0.677 |

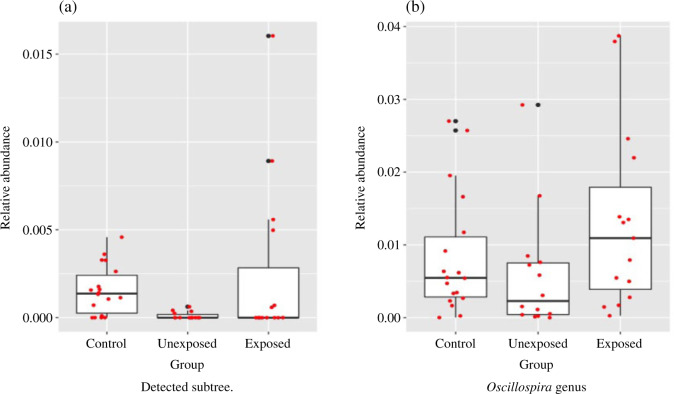

Besides the overall difference in microbiome compositions between groups A and B, dafot also identifies that the overall difference is due to the active flow on one edge. The subtree indexed by this edge is shown in Fig. 5(a), coloured red in the original phylogenetic tree and zoomed-in in a side figure. There are a total of 31 operational taxonomic units placed on this subtree, 18 of which are annotated as the Ruminococcaceae family and Oscillospira genus, and 13 of which are annotated as the Ruminococcaceae family and unknown genus. Figure 6(a) shows a boxplot of the combined relative abundance on these 31 operational taxonomic units, indicating that the relative abundance on this subtree decreased in ulcerative colitis patients, but is increased partially after receiving treatment. This is consistent with the previous findings on the proportion of Oscillospira genus and the Ruminococcaceae family in gut microbiota deceases in inflammatory bowel disease patients (Morgan et al., 2012; Konikoff & Gophna, 2016; Santoru et al., 2017). For comparison, a boxplot of the combined relative abundance of all operational taxonomic units assigned to the Oscillospira genus is shown in Fig. 6(b), showing that the pattern of relative abundance found in Fig. 6(a) is not that clear any more. This suggests that the finer species classification by microbial phylogeny can provide more power to detect the subtle difference between populations than standard taxonomic classification (Washburne et al., 2018).

Figure 6.

Boxplots of relative abundance on operational taxonomic units placed on the detected subtree in Fig. 5(a) and on all operational taxonomic units assigned to the Oscillospira genus. The red dots show the raw relative abundance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Shulei Wang, Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, U.S.A.

T Tony Cai, Department of Statistics, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, U.S.A.

Hongzhe Li, Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, U.S.A.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available at Biometrika online includes proofs of all theorems, additional simulation results and information on generalized optimal flow. The software package dafot is available at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/DAFOT/index.html.

References

- Aitchison, J. (1982). The statistical analysis of compositional data. J. R. Statist. Soc. B 44, 139–60. [Google Scholar]

- Aitchison, J. (2003). The Statistical Analysis of Compositional Data. Caldwell, NJ: Blackburn Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M. J. (2014). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). Wiley Statsref, doi: 10.1002/9781118445112.stat07841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Castro, E., Candes, E. J. & Durand, A. (2011). Detection of an anomalous cluster in a network. Ann. Statist. 39, 278–304. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Castro, E., Donoho, D. L. & Huo, X. (2005). Near-optimal detection of geometric objects by fast multiscale methods. IEEE Trans. Info. Theory 51, 2402–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Z. & Saranadasa, H. (1996). Effect of high dimension: By an example of a two-sample problem. Statist. Sinica 6, 311–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, T. T., Liu, W. & Xia, Y. (2014). Two-sample test of high-dimensional means under dependence. J. R. Statist. Soc. B 76, 349–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y., Lin, W. & Li, H. (2017). Two-sample tests of high-dimensional means for compositional data. Biometrika 105, 115–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Ryu, E., Hathcock, M., Ballman, K., Chia, N., Olson, J. E. & Nelson, H. (2016). Impact of demographics on human gut microbial diversity in a US midwest population. PeerJ 4, e1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., Li, J. & Zhong, P. (2019). Two-sample and ANOVA tests for high-dimensional means. Ann. Statist. 47, 1443–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. & Qin, Y. (2010). A two-sample test for high-dimensional data with applications to gene-set testing. Ann. Statist. 38, 808–35. [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis, T. Z., Hugenholtz, P., Larsen, N., Rojas, M., Brodie, E. L., Keller, K., Huber, T., Dalevi, D., Hu, P. & Andersen, G. L. (2006). Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5069–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dümbgen, L. & Spokoiny, V. G. (2001). Multiscale testing of qualitative hypotheses. Ann. Statist. 29, 124–52. [Google Scholar]

- Egozcue, J. J. & Pawlowsky-Glahn, V. (2016). Changing the reference measure in the simplex and its weighting effects. Austrian J. Statist. 45, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S. & Matsen, F. (2012). The phylogenetic Kantorovich–Rubinstein metric for environmental sequence samples. J. R. Statist. Soc. B 74, 569–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, J. (2017). Adaptive gPCA: A method for structured dimensionality reduction. arXiv: 1702.00501. [Google Scholar]

- Good, P. (2013). Permutation Tests: A Practical Guide to Resampling Methods for Testing Hypotheses. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Ingster, Y. I. (1993a). Asymptotically minimax hypothesis testing for nonparametric alternatives I. Math. Meth. Statist. 2, 85–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ingster, Y. I. (1993b). Asymptotically minimax hypothesis testing for nonparametric alternatives II. Math. Meth. Statist. 2, 171–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ingster, Y. I. (1993c). Asymptotically minimax hypothesis testing for nonparametric alternatives III. Math. Meth. Statist. 2, 249–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ingster, Y. I. & Suslina, I. A. (2012). Nonparametric Goodness-of-Fit Testing under Gaussian Models, New York: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, S., McDonald, D., Gonzalez, A., Navas-Molina, J. A., Jiang, L., Xu, Z., Winker, K., Kado, D. M., Orwoll, E., Manary, M. et al. (2018). Phylogenetic placement of exact amplicon sequences improves associations with clinical information. MSystems 3, e00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng, X. J., Cai, T. T. & Li, H. (2010). Optimal sparse segment identification with application in copy number variation analysis. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 105, 1156–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konikoff, T. & Gophna, U. (2016). Oscillospira: A central, enigmatic component of the human gut microbiota. Trends Microbiol. 24, 523–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W., Shi, P., Feng, R. & Li, H. (2014). Variable selection in regression with compositional covariates. Biometrika 101, 785–97. [Google Scholar]

- Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

Lozupone, C., Hamady, M., Kelley, S. & Knight, R. (2007). Quantitative and qualitative

diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl. Envir. Microbiol. 73, 1576–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl. Envir. Microbiol. 73, 1576–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. (2005). UniFrac: A new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Envir. Microbiol. 71, 8228–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, S., Van Treuren, W., White, R. A., Eggesbø, M., Knight, R. & Peddada, S. D. (2015). Analysis of composition of microbiomes: A novel method for studying microbial composition. Microbial Ecol. Health Dis. 26, 27663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle, B. H. & Anderson, M. J. (2001). Fitting multivariate models to community data: A comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology 82, 290–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mirarab, S., Nguyen, N. & Warnow, T. (2012). SEPP: SATé-enabled phylogenetic placement. In Pac. Symp. Biocomput., 247–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, X. C., Tickle, T. L., Sokol, H., Gevers, D., Devaney, K. L., Ward, D. V., Reyes, J. A., Shah, S. A., Leleiko, N., Snapper, S. B. et al. (2012). Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment (article) author. Genome Biol. 13, R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2021). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Pinto, J., Egozcue, J., Pawlowsky-Glahn, V., Paredes, R., Noguera-Julian, M. & Calle, M. (2018). Balances: A new perspective for microbiome analysis. MSystems 3, e00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. (2010). EdgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoru, M. L., Piras, C., Murgia, A., Palmas, V., Camboni, T., Liggi, S., Ibba, I., ai, M. A., Orrù, S., Blois, S. et al. (2017). Cross-sectional evaluation of the gut-microbiome metabolome axis in an Italian cohort of IBD patients. Scientific Rep. 7, 9523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sejdinovic, D., Sriperumbudur, B., Gretton, A. & Fukumizu, K. (2013). Equivalence of distance-based and RKHS-based statistics in hypothesis testing. Ann. Statist. 41, 2263–91. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. C., Snowberg, L. K., Caporaso, J. G., Knight, R. & Bolnick, D. I. (2015). Dietary input of microbes and host genetic variation shape among-population differences in stickleback gut microbiota. ISME J. 9, 2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, M. S. & Du, M. (2008). A test for the mean vector with fewer observations than the dimension. J. Multi. Anal. 99, 386–402. [Google Scholar]

- Székely, G. J. & Rizzo, M. L. (2005). A new test for multivariate normality. J. Multi. Anal. 93, 58–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, B. D., Robertson, C. E. & Harris, J. K. (2011). Application of two-part statistics for comparison of sequence variant counts. PLOS One 6, e20296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Fan, J., Pocock, G., Arena, E. T., Eliceiri, K. W. & Yuan, M. (2021). Structured correlation detection with application to colocalization analysis in dual-channel fluorescence microscopic imaging. Statist. Sinica 31, 333–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburne, A. D., Morton, J. T., Sanders, J., McDonald, D., Zhu, Q., Oliverio, A. M. & Knight, R. (2018). Methods for phylogenetic analysis of microbiome data. Nature Microbiol. 3, 652–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G. D., et al. (2016). Comparative metabolomics in vegans and omnivores reveal constraints on diet-dependent gut microbiota metabolite production. Gut 65, 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y. & Sun, J. (2017). Hypothesis testing and statistical analysis of microbiome. Genes Dis. 4, 138–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N., Chen, J., Carroll, I. M., Ringel-Kulka, T., Epstein, M. P., Zhou, H., Zhou, J. J., Ringel, Y. Li, H. & Wu, M. C. (2015). Testing in microbiome-profiling studies with MiRKAT, the microbiome regression-based kernel association test. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 96, 797–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.