Abstract

Purpose

Access to COVID-19 testing remained a salient issue during the early months of the pandemic, therefore this study aimed to identify 1) regional and 2) socioeconomic predictors of perceived ability to access Coronavirus testing.

Methods

An online survey using social media-based advertising was conducted among U.S. adults in April 2020. Participants were asked whether they thought they could acquire a COVID-19 test, along with basic demographic, socioeconomic and geographic information.

Results

A total of 6,378 participants provided data on perceived access to COVID-19 testing. In adjusted analyses, we found higher income and possession of health insurance to be associated with perceived ability to access Coronavirus testing. Geographically, perceived access was highest (68%) in East South Central division and lowest (39%) in West North Central. Disparities in health insurance coverage did not directly correspond to disparities in perceived access to COVID-19 testing.

Conclusions

Sex, geographic location, income, and insurance status were associated with perceived access to COVID-19 testing; interventions aimed at improving either access or awareness of measures taken to improve access are warranted. These findings from the pandemic's early months shed light on the importance of disaggregating perceived and true access to screening during such crises.

Keyword: COVID-19, coronavirus, Testing, geographic, Socio-economic, disparities

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has evolved into one of the most challenging public health crises in modern history. As of February 2021, the United States (U.S.) reported the highest number of confirmed cases and deaths worldwide [1]. The U.S. has made significant efforts to enhance testing capacity to promptly detect, treat, isolate cases, initiate contact tracing protocols to test contacts for infection, and track the spread of the virus and determine the scale of the pandemic [2,3]. As of February 7, 2021, over 305 million COVID-19 tests were performed in the U.S. (9% overall positive rate), with the states of Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Vermont having the highest number of daily tests per million nationwide [4,5]. Given socioeconomic disparities in the risk and outcome of COVID-19, particularly the disproportionate toll of the disease in communities of color in the U.S. [6,7], lack of equitable and universal access to COVID-19 testing has emerged as an area of concern for public health authorities and activists following the initial shortage of diagnostic tests [8].

Although several diagnostic and antibody tests have emerged throughout the pandemic, and faster and less costly diagnostic tests are continuously developed and deployed [9], resource-intensive RT-PCR molecular tests contributed to the delays in the early phase of the pandemic [10,11]. Likewise, during the early months of the pandemic there were significant quality assessment and control issues with new diagnostic tests as they were released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [12]. Efforts have since then been made to address these gaps in test availability [13]. The U.S. government and health insurance companies have attempted to expand access to COVID-19 testing through emergency measures such as making testing free-of-charge [14], and some state governments have enacted action plans to increase testing capacity [15,16]. The federal government also intervened in April 2020 by enacting the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to require that COVID-19 testing be covered by private health insurers [17]. However, concerns remain that testing may still impose a significant financial burden on uninsured populations or those with certain insurance plans because of gaps in protection [18]. A recent analysis of COVID-19 testing locations across the U.S. revealed access inequities among minorities, rural communities, and those with no insurance or low income [19]. Furthermore, geographic differences in the extent and timing of the spread of COVID-19 may have affected the populations’ awareness of the disease and played a role in local governments’ prioritization of efforts to enhance testing capacity and accessibility [1].

Past research suggests that those with low socioeconomic status, no or limited health insurance, and living in rural areas face greater access barriers to timely, comprehensive, and quality healthcare services [20]. To promote COVID-19 testing, interventions have been implemented to improve access (e.g., government policies to enhance testing capacity, specifically in low-resource communities) [15] and perceived access (e.g., insurer communication campaigns on new policies and protections regarding testing) [14]. Several factors may influence an individual's decision to get tested, including the perceived need for being tested, perceived safety of getting tested, perceived severity of COVID-19, and possible consequences of a positive test result. To that end, this study aims to assess individuals’ perceptions of their ability to access COVID-19 testing during the first peak of the pandemic in the U.S.

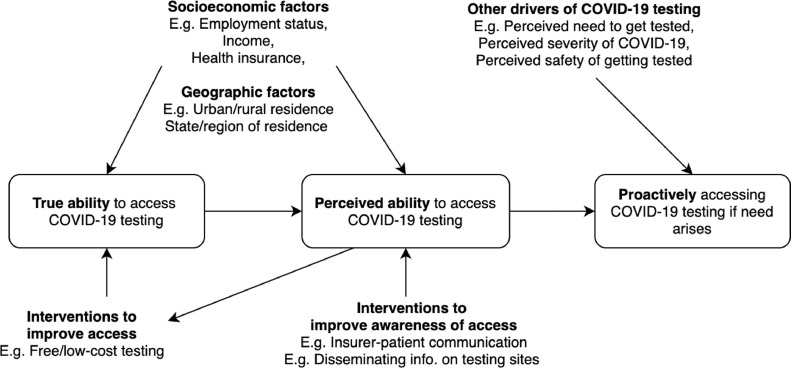

The importance of the perceived ability to access COVID-19 testing, which makes it distinct from the actual availability of testing infrastructure and opportunities, lies in the fact that socioeconomic circumstances and geographic location of individuals influence not only their actual capacity to access testing, but also their perceived ability to proactively seek testing services (Fig. 1 ) [21]. For example, while policies to improve access to testing for low-income or uninsured individuals are implemented (such as through free testing), gaps in awareness of these policies may result in the cost of testing to remain as a perceived barrier rather than an actual barrier in these target populations. Indeed, past research on HIV prevention has shown perceptions and awareness of testing services to be an area of concern in addressing disparities [22,23].

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework on relationship between true and perceived ability to access COVID-19 testing.

Using data from a nationwide survey of U.S. adults conducted in April 2020, we examine individual-level factors that may associate with perceived access to COVID-19 testing. While both perceived and actual ability to access COVID-19 testing have no doubt changed in more recent months, this data from the early months of the pandemic corresponds to a time period when various nationwide and state-level policies aimed at improving access to COVID-19 testing were being formulated and implemented [14], [15], [16], [17]. In doing so, this study sheds light on whether disparities in perceptions of access to testing services during an infectious disease pandemic were aligned with efforts seeking to improve accessibility of these services, while highlighting the importance of other supportive measures, such as those aimed at improving awareness of such policies or efforts.

Methods

Participant recruitment

The full study methodology and recruitment strategy have been described elsewhere [24]. Briefly, social media users (primarily Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger) aged ≥18 years and residing in the U.S. (eligibility conditions) were recruited using an advertisement campaign on the aforementioned social media platforms with a link to an online Qualtrics (Provo, UT) survey; eligibility was assessed through a set of screening questions at the start of the survey. Facebook (and affiliated platforms) was chosen due to its extensive past use in health research as a low cost and efficient recruitment tool (particularly in the context of data collection in rapidly evolving health crises, such as COVID-19) [24,25]. Although not a nationally representative sample, recruited participants were a demographically and regionally diverse national sample across multiple key indicators [24]. Recruitment occurred from April 16–21, 2020. The advertisement campaign was designed to target adults of any sex residing in the U.S. Eligibility was assessed using two screening questions. Those who were ineligible or completed the survey were provided a list of COVID-19 resources from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the CDC.

Measurement of variables

The development of the survey questions was informed by the WHO tool for behavioral insights on COVID-19 [26] and previous health belief model-based questionnaires on infectious disease outbreaks [27], [28], [29], [30]. Perceived access to COVID-19 testing was captured by a single binary (Yes or No) question: “Do you think you would be able to get a test for Coronavirus if you thought you needed one?” Health insurance status was ascertained using a single binary question, and those who reported having health insurance were asked to specify the primary source of their insurance [31] (including plans through an employer, spouse, or parent, Medicare, self-purchased or other, and Medicaid or state-Medicaid). Demographic and socioeconomic variables included sex, age, race, educational attainment, employment status, marital status, living with children <18 years of age, U.S. state of residence, urban/suburban/rural residence, and annual household income. Lost income status was assessed by a single question (Yes, No, or Not Applicable): “Have you lost income from a job or business because of the Coronavirus?” Geographical region and division of residence were based on the U.S. Census region (groups of states based on their geographic location, including the Northeast, South, Midwest, and West) and division (a smaller grouping of states within each region based on their disaggregated geographic locations, with each region having 2–3 divisions) definitions using U.S. state of residence information provided by participants. All variables were ascertained by self-report. The analysis was conducted by geographic division due to small sample sizes attained from individual states [32].

Statistical analysis

Participants who answered the question on perceived access to COVID-19 testing were included in the final sample; those who responded “prefer not to say” to any of the demographic questions were excluded from the analysis. Descriptive statistics of participant characteristics, stratified by perceived access to COVID-19 testing, were calculated. Initially, bivariate contingency tale analyses assessed socioeconomic and geographic variables that were statistically different between those who answered “yes” and “no” to the question on perceived access to COVID-19 testing. Second, multivariable logistic regression analysis estimated the odds of perceived access to COVID-19 testing, adjusted for significant socioeconomic and geographic variables identified in the bivariate analysis. Although the initial model focused on self-reported health insurance status, a separate multivariable logistic regression analysis was also conducted to further differentiate health insurance coverage and determine the odds of perceived access by source of primary health insurance, adjusted for significant socioeconomic and geographic variables. Selection of socioeconomic and geographic variables adjusted in multivariate model was informed by bivariate analyses and past literature [18,20]. Bivariate analyses of socio-demographic and regional differences by source of health insurance guided the selection of covariates in the more granular regression model. Participants with missing data for variables included in the models were excluded from the analysis. All analyses were conducted using R (version 4.0.0). Finally, the geographic differences in perceived access to COVID-19 testing and health insurance status across U.S. regional divisions [32] were displayed using Tableau (version 2020.2.0).

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 6676 responses were received, of which 6518 were eligible to complete the survey. Of those, 6378 (97.9%) provided data on perceived access to COVID-19 testing (final sample). Due to the small sample size of participants who identified as “Other” for sex (n = 14), this category was not included in the analysis. Respondent's race was re-categorized and converted into a binary variable (“White, Non-Hispanic”/“Non-White”) due to the small number of participants not identifying as White, Non-Hispanic, which were collectively 7.8% of the sample (including 167 (2.6%) Hispanic/Latinx; 50 (0.8%) Black, Non-Hispanic; 48 (0.8%) Asian/Pacific Islander; 44 (0.7%) Native American or American Indian; and 187 (2.9%) interracial, mixed race, or other race participants). Participants were mostly female (57.6%), Non-Hispanic white (92.2%), married or cohabiting (70.8%), employed (56.2%), lived in suburban residences (53.3%), were not living with children (74.5%), and held a bachelor's degree or higher (55.5%) (Supplemental File 1). Almost all participants (94.4%) reported having health insurance. Sociodemographic variables observed to be significant in the bivariate analysis by perceived ability to access COVID-19 testing included sex, age, employment status, marital status, income, health insurance status, and have lost wages due to COVID-19. Although past evidence has shown significant associations between race and ethnicity and COVID-19 testing [33], [34], [35], the lack of association observed in the binary race variable constructed in bivariate analyses (P = .075) and our subsequent inability to appropriately adjust for the variable in multivariate models was likely due to the small sample size of disaggregated racial and ethnic sub-populations (which constrained our ability to identify any disparities across this diverse group of Non-White participants). Although differences in both the U.S. census region and division were found to be significant in the bivariate analysis, the division was used for subsequent analyses since it provided more specific data on geographic location.

Socioeconomic differences in perceived access to COVID-19 testing

Slightly over half of the participants (51.7%) believed that they could have access to COVID-19 testing if they needed to. The proportion of those believing they could access COVID-19 testing varied across socioeconomic status and was notably low among those aged 18–39 years old (47.8%), students and unpaid workers (42.5%), those with an annual household income of less than $30,000 (39.8%), and those without health insurance (39.8%) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Socioeconomic predictors of perceived access to COVID-19 testing among U.S. adults, April 2020.

| Variable | Perceived access to COVID-19 testing | Adjusted* odds of perceived access to COVID-19 testing | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (total) | % | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 3637 | 48.0 | Ref | |

| Male | 2679 | 56.7 | 1.51 (1.32–1.73) | <.001 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–38 years old | 1056 | 47.8 | Ref | |

| 40–59 years old | 2747 | 51.9 | 0.99 (0.83–1.19) | .953 |

| 60+ years old | 2575 | 53.1 | 0.95 (0.77–1.19) | .677 |

| Division [Region] | ||||

| East South Central [South] | 244 | 68.0 | Ref | |

| South Atlantic [South] | 791 | 53.7 | 0.54 (0.38–0.78) | .001 |

| West South Central [South] | 344 | 64.0 | 0.73 (0.48–1.10) | .138 |

| Middle Atlantic [Northeast] | 1027 | 49.0 | 0.43 (0.30–0.60) | <.001 |

| New England [Northeast] | 352 | 52.8 | 0.57 (0.38–0.85) | .006 |

| East North Central [Midwest] | 918 | 45.0 | 0.37 (0.26–0.52) | <.001 |

| West North Central [Midwest] | 390 | 38.7 | 0.29 (0.19–0.43) | <.001 |

| Mountain [West] | 422 | 49.8 | 0.43 (0.29–0.64) | <.001 |

| Pacific [West] | 572 | 48.1 | 0.41 (0.28–0.59) | <.001 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 2845 | 50.9 | Ref | |

| Student/Unpaid work | 280 | 42.5 | 0.82 (0.59–1.14) | .225 |

| Not working/unemployed | 635 | 46.5 | 1.07 (0.87–1.33) | .521 |

| Retired | 1300 | 52.8 | 1.17 (0.95–1.44) | .136 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 3585 | 48.1 | Ref | |

| Single | 831 | 53.3 | 1.07 (0.88–1.30) | .480 |

| Divorced/separated | 430 | 54.9 | 0.98 (0.76–1.26) | .860 |

| Widowed | 214 | 49.5 | 1.12 (0.78–1.62) | .543 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| Less than $30,000 | 580 | 39.8 | Ref | |

| $30,000 to less than $50,000 | 671 | 46.9 | 1.53 (1.17–1.99) | .002 |

| $50,000 to less than $75,000 | 767 | 48.5 | 1.59 (1.22–2.07) | .001 |

| $75,000 to less than $100,000 | 900 | 51.8 | 1.81 (1.39–2.37) | <.001 |

| $100,000 or more | 1419 | 55.0 | 1.97 (1.52–2.56) | <.001 |

| Lost income due to Coronavirus | ||||

| No | 2995 | 52.4 | Ref | |

| Yes | 1995 | 48.9 | 0.94 (0.82–1.08) | .385 |

| Health insurance status | ||||

| No | 357 | 39.8 | Ref | |

| Yes | 6021 | 52.4 | 1.73 (1.29–2.35) | <.001 |

Adjusted for sex, age, division, employment status, marital status, annual household income, lost income due to Coronavirus, and health insurance.

The adjusted odds of perceived access to COVID-19 testing differed across multiple socioeconomic indicators (Table 1). Compared to females, males were more likely to perceive they could access COVID-19 testing (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.51, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.32–1.73). We observed an income gradient, with higher income being associated with higher odds of perceived access to COVID-19 testing.

Geographic differences in perceived access to COVID-19 testing

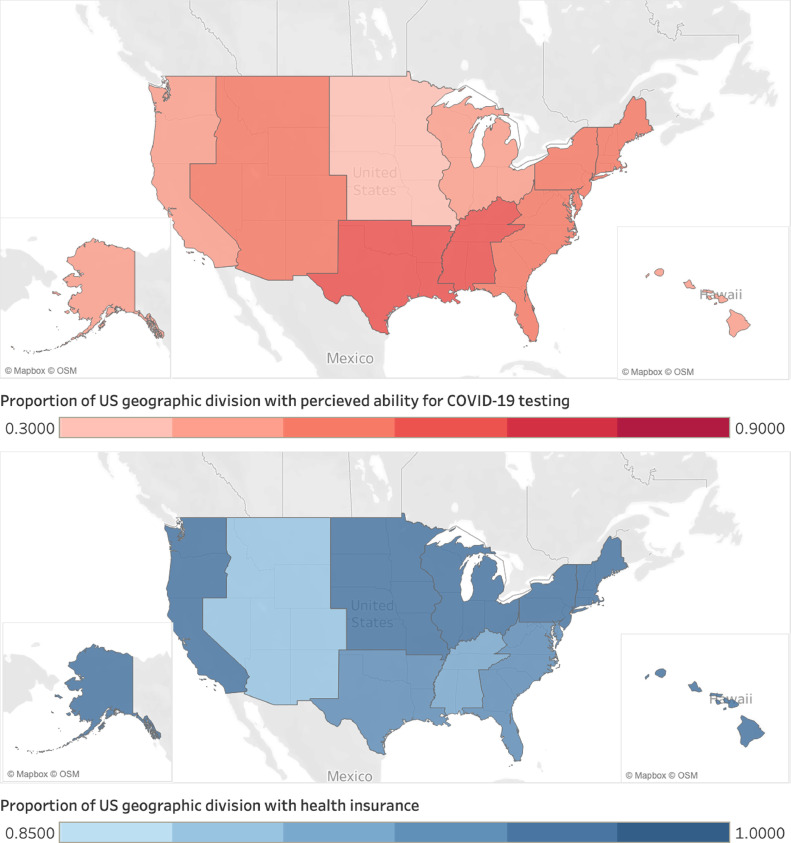

The median number of responses per state was 100 (interquartile range [IQR]: 32.2–121.3), with the greatest number of responses from New York (n = 495) and the lowest number from the District of Columbia (n = 3). Perceived access to COVID-19 testing varied markedly across U.S. census regions and divisions, with the highest perceived access to COVID-19 testing in the East South Central division (68.0%) and the lowest in the West North Central division (38.7%); adjusted odds of perceived access to COVID-19 testing were significantly lower across all divisions compared to East South Central, except for West South Central (Table 1). Figure 2 displays the geographic variation in perceived access to COVID-19 testing and health insurance status across U.S. census divisions (Supplemental Table 2 for tabulated data). Although health insurance coverage in the study population was relatively high, it varied by region, with the highest coverage in the Middle Atlantic division (97.2%) and the lowest in the Mountain division (89.7%). However, it must be noted that while geographic variation at the regional and divisional levels was observed for both perceived ability to access to COVID-19 testing and health insurance, notable state-by-state heterogeneity was also observed within each region (Supplemental Table 2), albeit based on much smaller sample sizes.

Fig. 2.

Geographic disparities in perceived access to COVID-19 testing and health insurance status in the study population, April 2020. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Health insurance and perceived access to COVID-19 testing

Overall, those with health insurance, relative to those with no health insurance, had higher odds of perceived access to COVID-19 testing (AOR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.29–2.35), when adjusted for covariates. Among insured participants the most common source of insurance was through an employer (41.9%), followed by Medicare (22.3%) and through a spouse's employer (18.0%). Table 2 presents the adjusted odds of perceived access by health insurance type. Except for Medicaid, respondents with any source of insurance had higher odds of perceived access to COVID-19 testing than those without insurance. Compared to those without insurance, adjusted odds of perceived access were the highest among those who have coverage through a parent's insurance plan (AOR: 1.68, 95%CI: 1.26–2.24).

Table 2.

Source of health insurance and perceived access to COVID-19 testing among respondents to an online nationwide survey in the United States, April 2020.

| Main source of health insurance | Adjusted* odds of perceived access to COVID-19 testing | P value |

|---|---|---|

| No insurance (n = 357) | Ref | |

| Plan through employer/spouse/parent (n = 3433) | 1.68 (1.26–2.24) | <.001 |

| Medicare (n = 1233) | 1.67 (1.22–2.31) | .002 |

| Self-purchased or other (n = 583) | 1.65 (1.19–2.30) | .003 |

| Medicaid/State-Medicaid (n = 289) | 1.18 (0.80–1.74) | .403 |

Adjusted for age, region, urban/rural status, employment status, marital status, annual household income.

Discussion

Overall, disparities were observed in perceived access to COVID-19 testing according to health insurance status (including different types of health insurance), income, and geographic region. Specifically, participants with any source of insurance, except for Medicaid, were more likely than uninsured participants to perceive that they would be able to access COVID-19 testing. Although insurance coverage was high in the study population, there were considerable geographic differences in perceived access to COVID-19 testing across U.S. geographic regions and divisions. These findings highlight that, even as efforts are ramped up to promote COVID-19 testing, there is a need to carefully consider and appropriately address both socioeconomic and geographic disparities in perceived access to testing.

Health insurance and COVID-19 testing

Despite efforts on the part of the federal government and health insurance providers to expand COVID-19 testing to both insured and uninsured individuals alike [14,17], the findings show that perceived access to COVID-19 testing was still determined by health insurance coverage. This suggests a need for stronger, population-wide communication of expanded coverage for COVID-19 testing, particularly targeting uninsured populations. Furthermore, people may still be concerned about incurring costs for some types of testing [36], may not be aware of where to get a test, may still be subject to appointment and insurance requirements, or may not be willing to wait in long lines to get tested due to safety concerns. This perceived inability to get a COVID-19 test may, in part, be explained by concerns about the existing protection gaps afforded by expansion efforts, or the emerging evidence of other sociodemographic and geographic barriers to COVID-19 testing [19]. Taken together, further research is needed to qualitatively assess the potential reasons behind why COVID-19 testing is perceived as inaccessible by many Americans.

A key finding was the lack of association observed between those with Medicaid, government-sponsored health insurance for low-income, vulnerable populations [37], and perceived access to COVID-19 testing. While this may suggest that Medicaid is not providing the same increase in perceived access as other forms of health insurance, it must be noted that the study sample was composed of largely high-income individuals, with those relying on Medicaid comprising only 4.5% of the study population (n = 289). While the percentage of the participants with any form of health insurance (94.4%) was slightly higher than the 2019 U.S. average of 92.0%, [38] this high health insurance coverage in the study sample precluded an analysis of socioeconomic disparities by insurance status. Therefore, further large-scale observational research among low-income or socio-economically vulnerable populations is needed to corroborate our overall findings, and the specific finding that Medicaid insurance is not associated with actual and perceived access to COVID-19 testing.

Socioeconomic factors and COVID-19 testing

The study did not find an association between employment status and perceived access to COVID-19 testing; however, the results indicated that income status was significantly associated with perceived access, corroborating reports of low-income neighborhoods experiencing greater perceived inability to access COVID-19 testing [39]. Indeed, these findings support efforts currently underway to improve access to testing in low-income and underserved communities, as access to health care services is one of the important drivers of health inequalities [40].

One unexpected finding was that men were significantly more likely than women to express a perceived ability to access COVID-19 testing, despite gender-based bivariate analyses showing men to also be significantly less likely to have health insurance, a disparity noted in previous studies [41]. However, what may explain these findings is that men had significantly (P < .001) higher income than women; 36.7% of men had an annual household income of more than $100,000, versus only 29.9% of women. Although income was controlled for in the analysis, given that a substantial proportion of income data was also missing (31.8%), further large-scale analyses among diverse populations may shed further light on whether these sex-disparities (or income disparities) in perceived access to COVID-19 are meaningful for public health policy considerations.

Geographic disparities and COVID-19 testing

Disparities in perceived access to COVID-19 testing were observed across the country. Importantly, disparities in health insurance coverage did not directly correspond to disparities in perceived access to COVID-19 testing. For instance, while the West North Central division had the lowest level of perceived access to COVID-19 testing among the nine U.S. divisions, it had the fourth-highest proportion of insured individuals in the study sample. Likewise, while the Mountain division had the lowest proportion of insured individuals, it had the fourth-highest level of perceived access to COVID-19 testing. These findings emphasize that regional disparities in health insurance coverage alone may not explain disparities in perceived access to COVID-19 testing and that factors related to regional- and division-level testing disparities, such as availability and accessibility of testing sites, and other socioeconomic or geographic disparities [19] should be considered in efforts to enhance access to testing. However, these preliminary findings at aggregate geographic levels of regions and divisions may inform large-scale and systematic surveillance initiatives to understand state-level disparities in COVID-19 testing (both during the early months of the pandemic as well as now) and provide guidance to state-level policy initiatives. Likewise, while populations living in rural areas have low access to health services in general [42], no significant differences in perceived access to COVID-19 testing was observed by urban/rural status. Future studies using nationally representative data are needed to provide more detailed insights into the relationship between type of residence and perceived access to COVID-19 testing.

Strengths and limitations

There were several strengths of this study, including 1) reaching a large, geographically diverse sample in a short frame time during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic through social-media advertisement-based recruitment methods; [24] 2) obtaining a large sample size among some sub-populations particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, such as older adults; and 3) obtaining a diverse sample of types of health insurance possessed by participants to allow for disaggregated analysis on the effect of insurance type on the outcome variable. However, the study was limited by the non-probability convenience sampling from Facebook and affiliated platform users. Although 70% of Americans use Facebook, certain demographic groups may be underrepresented (e.g., racial and ethnic minorities), which limits the generalizability of the findings [43]. While efforts were made to enhance the sampling of racial and ethnic minorities during recruitment [24] through supplemental social media advertisements specifically targeting African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans, the racial and ethnic diversity of the sample did not improve in both rounds of survey implementation. As a matter of fact, studies that have used Facebook and other social media platforms for recruitment have reported similar problems [25]. Given the significant structural barriers experienced by such minority populations in the U.S. in access to COVID-19 testing [33], [34], [35], there is a clear need for further in-depth research to build upon these preliminary findings and identify key modifiable drivers related to perceived access to COVID-19 to reduce disparities.

Moreover, although the association between geographic divisional differences and perceived access to COVID-19 testing and health insurance coverage were analyzed, in reality, any geographic differences in policy actions relevant to COVID-19 testing occur at a state level (rather than at a divisional level). We were unable to conduct a comprehensive state-based geographic analysis due to some small state-level sample sizes. Future scaled-up, nationally representative survey research is needed to build on these preliminary findings on geographic disparities. Finally, given that there have been continued efforts to enhance testing in the weeks and months since the survey data were collected in late April 2020 [15], changes in actual and perceived access to COVID-19 testing are likely to have occurred. To address this, the survey used in this study will be adapted and administered periodically throughout the COVID-19 crisis. Nonetheless, these findings have shed light on socioeconomic and geographic disparities in access to testing during the early phase of a major health crisis and can inform areas of early policy action for future public health crises.

Conclusions

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most significant health crises faced by the U.S. in modern history. The need to expand access to COVID-19 testing is key to assessing the extent and scale of the pandemic and develop interventions to contain and prevent onward spread. Although some efforts had been made to enhance access to tests during the early months of the pandemic, our findings highlight that many Americans perceived difficulty in accessing COVID-19 testing. Likewise, it is important to consider that the observed perceived inability may also be attributed to a lingering sense of test shortages that were observed during the early months of the pandemic in the U.S.; indeed, there may be a salient delay between actions taken to enhance COVID-19 testing access and the awareness or perception of enhanced access, as reflected in the linkages in Figure 1. These findings also highlight the need for mixed-method research approaches for a qualitative assessment of the reasons behind perceived inability to access COVID-19 testing as the pandemic has progressed and the specific concerns individuals may have regarding access to testing (e.g., awareness of testing locations, costs of tests, etc.). Although COVID-19 testing capacity and access have markedly improved since the early days of the pandemic, our data provide a snapshot of disparities in perceived access at a time of greater uncertainty as the virus was beginning to spread across the U.S. and highlight some of the key socioeconomic and geographic factors that may need to be considered concerning access in future infectious diseases crises.

Acknowledgments

This study was self-funded by study authors, and study authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2021.03.001.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez E. American Heart Association Web site; 2020. COVID-19 science: why testing is so important. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2020/04/02/covid-19-science-why-testing-is-so-important, Accessed June 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedford J., Enria D., Giesecke J., Heymann D.L., Ihekweazu C., Kobinger G., et al. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. The Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30673-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United states laboratory testing. https://www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/index.html. Published 2020. Accessed February 7, 2021.

- 5.Kaiser Family Foundation. COVID-19 testing. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/covid-19-testing/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Number%20of%20Tests%20with%20Results%20per%201,000%20Population%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D. Published 2020. Accessed February 7, 2021.

- 6.Raifman M.A., Raifman J.R. Disparities in the population at risk of severe illness from COVID-19 by race/ethnicity and income. Am J Prev Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.003. S0749-3797(0720)30155-30150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiriboga D., Garay J., Buss P., Madrigal R.S., Rispel L.C. Health inequity during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cry for ethical global leadership. The Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1690–1691. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31145-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd-Barrett C. Striving for equity in COVID-19 testing. California health care foundation web site. https://www.chcf.org/blog/striving-equity-covid-19-testing/. Published 2020. Accessed July 5, 2020.

- 9.OECD. Testing for COVID-19: a way to lift confinement restrictions. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/testing-for-covid-19-a-way-to-lift-confinement-restrictions-89756248/. Published 2020. Accessed July 5, 2020.

- 10.Pfeiffer S., Anderson M., Van Woerkom B. Despite early warnings, U.S. took months to expand swab production for COVID-19 test. NPR web site. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/12/853930147/despite-early-warnings-u-s-took-months-to-expand-swab-production-for-covid-19-te. Published 2020. Accessed July 5, 2020.

- 11.Canipe C., Hartman T., Suh J. The COVID-19 testing challenge. Reuters web site. https://graphics.reuters.com/HEALTH-CORONAVIRUS/TESTING/azgvomklmvd/. Published 2020. Accessed July 5, 2020.

- 12.Peter Whoriskey, Satija N. How U.S. coronavirus testing stalled: flawed tests, red tape and resistance to using the millions of tests produced by the WHO. The Washington Post web site. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/03/16/cdc-who-coronavirus-tests/. Published 2020. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 13.Herman C. University labs help states increase COVID-19 testing capacity. WFYI Indianapolis web site. https://www.wfyi.org/news/articles/university-labs-help-states-increase-covid-19-testing-capacity. Published 2020. Accessed July 5, 2020.

- 14.America's Health Insurance Plans. Health insurance providers respond to coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.ahip.org/health-insurance-providers-respond-to-coronavirus-covid-19/. Published 2020. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- 15.California Department of Public Health. Expanding access to testing: updated interim guidance on prioritization for COVID-19 laboratory testing. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-19/Expanding-Access-to-Testing-Updated-Interim-Guidance-on-Prioritization-for-COVID-19-Laboratory-Testing-0501.aspx. Published 2020. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- 16.New York Department of Health. Revised interim guidance: protocol for COVID-19 testing applicable to all health care providers and local health departments. https://coronavirus.health.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2020/07/doh_covid19_revisedtestingprotocol_070220.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed August 1, 2020.

- 17.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Trump administration announces expanded coverage for essential diagnostic services amid COVID-19 public health emergency. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-announces-expanded-coverage-essential-diagnostic-services-amid-covid-19-public. Published 2020. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- 18.Rodriguez C.H. COVID-19 tests that are supposed to be free can ring up surprising charges. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/04/29/847450671/covid-19-tests-that-are-supposed-to-be-free-can-ring-up-surprising-charges. Published 2020. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- 19.Rader B., Astley C.M., Sy K.T.L., Sewalk K., Hswen Y., Brownstein J.S., et al. Geographic access to United States SARS-CoV-2 testing sites highlights healthcare disparities and may bias transmission estimates. J Travel Med. 2020;27(7):taaa076. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kushel M.B., Gupta R., Gee L., Haas J.S. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson S., Eilperin J., Dennis B. 2020. As coronavirus testing expands, a new problem arises: not enough people to test. the Washington post web site. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/as-coronavirus-testing-expands-a-new-problem-arises-not-enough-people-to-test/2020/05/17/3f3297de-8bcd-11ea-8ac1-bfb250876b7a_story.html, Published Accessed June 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulin H.N., Blevins M., Koethe J.R., Hinton N., Vaz L.M., Vergara A.E., et al. HIV testing service awareness and service uptake among female heads of household in rural Mozambique: results from a province-wide survey. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Logie C.H., Okumu M., Mwima S.P., et al. Exploring associations between adolescent sexual and reproductive health stigma and HIV testing awareness and uptake among urban refugee and displaced youth in Kampala, Uganda. Sex Reprod Health Mat. 2019;27(3):86–106. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1695380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali S.H., Foreman J., Capasso A., Jones A.M., Tozan Y., DiClemente R.J. Social media as a recruitment platform for a nationwide online survey of COVID-19 knowledge, beliefs, and practices in the United States: methodology and feasibility analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01011-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitaker C., Stevelink S., Fear N. The use of Facebook in recruiting participants for health research purposes: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(8):e290. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. Survey tool and guidance: rapid, simple, flexible behavioural insights on COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasan F., Khan M.O., Ali M. Swine flu: knowledge, attitude, and practices survey of medical and dental students of Karachi. Cureus. 2018;10(1):e2048. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2048. -e2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Rabiaah A., Temsah M.-.H., Al-Eyadhy A.A., Hasan G.M., Al-Zamil F., Al-Subaie S., et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Corona Virus (MERS-CoV) associated stress among medical students at a university teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(5):687–691. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Painter J.E., DiClemente R.J., von Fricken M.E. Interest in an Ebola vaccine among a U.S. national sample during the height of the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Vaccine. 2017;35(4):508–512. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Painter J.E., von Fricken M.E., Viana de O.M.S., DiClemente R.J. Willingness to pay for an Ebola vaccine during the 2014-2016 ebola outbreak in West Africa: results from a U.S. National sample. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1665–1671. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1423928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaiser Family Foundation . 2020. KFF coronavirus poll – March 2020. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Topline-KFF-Coronavirus-Poll.pdf, Published Accessed June 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Census . 1984. Census regions and divisions of the United States. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf, Published Accessed April 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmitt-Grohé S., Teoh K., Uribe M. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. COVID-19: testing inequality in New York city; pp. 0898–2937. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lieberman-Cribbin W., Tuminello S., Flores R.M., Taioli E. Disparities in COVID-19 testing and positivity in New York City. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thakur N., Lovinsky-Desir S., Bime C., Wisnivesky J.P., Celedón J.C. The structural and social determinants of the racial/ethnic disparities in the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic. What's our role? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(7):943–949. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1523PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abrams A. COVID-19 testing is supposed to be free. Here's why you might still get billed. In. Time2020.

- 37.US Department of Health and Human Services . 2017. Who is eligible for Medicaid? https://www.hhs.gov/answers/medicare-and-medicaid/who-is-eligible-for-medicaid/index.html, Published Accessed Augusts 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keisler-Starkey Katherine, Bunch L.N. 2020. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2019. U.S. census bureau web site. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-271.html#:~:text=The%20percentage%20of%20people%20with,of%202019%20was%2092.0%20percent.&text=Private%20health%20insurance%20coverage%20was,point%20during%20the%20year%2C%20respectively, Published Accessed February 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dizikes C., Palomino J. Why testing for coronavirus in low-income neighborhoods lagged. San Francisco chronicle web site. https://www.govtech.com/em/safety/Why-Testing-for-Coronavirus-in-Low-Income-Neighborhoods-lagged.html. Published 2020. Accessed August 1, 2020.

- 40.Riley W.J. Health disparities: gaps in access, quality and affordability of medical care. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2012;123:167–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harvard men's health watch. Mars vs. Venus: the gender gap in health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/mars-vs-venus-the-gender-gap-in-health. Published 2019. Accessed August 1, 2020. [PubMed]

- 42.Douthit N.T., Kiv S., Dwolatzky T., Biswas S. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health. 2015;129(6):611–620. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perrin A., Anderson M. Share of US adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center Web site. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/. Published 2019. Accessed May 23, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.