Abstract

Background:

Short bowel syndrome resulting from small bowel resection (SBR) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Many adverse sequelae including steatohepatitis and bacterial overgrowth are thought to be related to increased bacterial translocation, suggesting alterations in gut permeability. We hypothesized that after intestinal resection, the intestinal barrier is altered via toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling at the intestinal level.

Methods:

B6 and intestinal-specific TLR4 knockout (iTLR4 KO) mice underwent 50% SBR or sham operation. Transcellular permeability was evaluated by measuring goblet cell associated antigen passages via two-photon microscopy. Fluorimetry and electron microscopy evaluation of tight junctions (TJ) were used to assess paracellular permeability. In parallel experiments, single-cell RNA sequencing measured expression of intestinal integral TJ proteins. Western blot and immunohistochemistry confirmed the results of the single-cell RNA sequencing.

Results:

There were similar number of goblet cell associated antigen passages after both SBR and sham operation (4.5 versus 5.0, P > 0.05). Fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran uptake into the serum after massive SBR was significantly increased compared with sham mice (2.13 ± 0.39 ng/μL versus 1.62 ± 0.23 ng/μL, P < 0.001). SBR mice demonstrated obscured TJ complexes on electron microscopy. Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed a decrease in TJ protein occludin (21%) after SBR (P < 0.05), confirmed with immunostaining and western blot analysis. The KO of iTLR4 mitigated the alterations in permeability after SBR.

Conclusions:

Permeability after SBR is increased via changes at the paracellular level. However, these alterations were prevented in iTLR4 mice. These findings suggest potential Intestinal barrier protein targets for restoring the intestinal barrier and obviating the adverse sequelae of short bowel syndrome.

Keywords: Short gut, TLR4, Gut permeability, Tight junction, Intestinal resection, Mice, Intestinal barrier

Introduction

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) typically occurs after extensive bowel resection for postnatal conditions such as necrotizing enterocolitis. Adverse sequelae of SBS include cholestasis and liver injury with 40%–60% of patients experiencing intestinal failure-associated liver disease (IFALD)1,2 Although a major component of IFALD involves parenteral nutrition, liver injury may also occur due to increased permeability and intestinal dysbiosis that develops after extensive intestinal resection.3–5 Current therapy for preventing dysbiosis and decreasing infections is limited to prophylactic antibiotics.6 To provide superior therapy to these patients, a better understanding of intestinal barrier function after resection is needed.

Barrier dysfunction leading to increased permeability occurs via two primary pathways—paracellular and trans-cellular. Paracellular permeability is regulated by intercellular complexes, namely, desmosomes, adherens junctions, and tight junctions (TJs).7 In transcellular permeability, molecules are transported through the intestinal epithelial cells by endocytosis, passive diffusion, or binding to specific membrane transporters.8

Animal models of SBS after massive small bowel resection (SBR) have demonstrated perturbed barrier function as evidenced by translocation of luminal bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs), blood, and peripheral organs such as liver and spleen.9–11 This translocation of bacteria is thought to contribute to bacterial overgrowth and sepsis that is observed in patients with SBS. Lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) found on the outer membrane of bacteria are thought to mediate this inflammatory process through the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signal transduction axis. In addition, TLR4 has been implicated in the development of steatosis in disease processes such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis in mice and humans.4–7

Our laboratory has previously demonstrated significant liver steatosis after SBR compared with unoperated mice with similar food intake and body weight.9 This liver injury was mitigated by globally knocking out TLR4.12 This suggested a potential intimate relationship between TLR4 and intestinal permeability in producing the subsequent hepatic injury. Therefore, we hypothesized that permeability is significantly altered after SBR and that intestine-specific TLR4 plays a role in mediating this barrier dysfunction.

Methods

Mice

All protocols and experiments were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee (Protocol #20170258) and followed National Institutes of Health animal care guidelines. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Transgenic mice bearing a tamoxifen-dependent Cre recombinase (vil-Cre-ERT2) expressed under the control of the villin promoter were bred in the house. Tamoxifen was administered for three consecutive days to induce recombination thereby preventing expression of TLR4 only in intestinal epithelial cells. Mice were kept in an animal holding area with a 12-h light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. SBR animals and sham animals were provided the same amount of food.

Operations

All operated mice underwent a 50% proximal SBR or sham operation as we have previously described.13 Briefly, through a midline laparotomy, the bowel was exteriorized and then transected 12 cm from the terminal ileum and 2–3 cm from the pylorus. The intervening mesentery was ligated with silk sutures, and an end-to-end anastomosis was performed with interrupted 9-0 nylon sutures. For sham operations, the proximal bowel was transected 12 cm from the terminal ileum and a reanastomosis was performed (no resection). Animals were fasted for the first 24 h postoperatively and then returned to standard liquid diet (LD; PMI Micro-Stabilized Rodent Liquid Diet LD 101; TestDiet, St. Louis MO).

Animals were sacrificed 10 wk after operation. At the time of death, a midline laparotomy was performed, and the entire small intestine was flushed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing protease inhibitors (0.2 nmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mg/mL aprotinin, 1 mmol/L benzamidine, 1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, and 2 mmol/L cantharidin). A 2-cm segment of bowel distal to the anastomosis was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for histology. The remainder of the distal segment was used to isolate the crypt and villus. Protein extracted from the isolated crypt or villus was used for western blot assay, and RNA was used for real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays.

Paracellular permeability

Mice were orally gavaged with 200 μL 4kD fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran, and serum was subsequently collected 60 min after injection and uptake was quantified via fluorimetry. In subsequent experiments, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and laparotomy was performed. A clip was applied 10 cm proximal to the cecum and 200 μL 4kD FITC-dextran was injected intraluminally and then a subsequent clip was placed at the ileocecal junction. Mouse serum was collected 30, 45, and 60 min after injection to identify the peak time of maximum absorption, and dextran content was quantified via fluorimetry.

Electron microscopy

Small intestine was fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and 0.2% tannic acid in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). After washing with buffered 10% sucrose, the blocks were fixed with 1% OsCU in the same buffer on ice for 2 hr and then stained en bloc with 0.5% aqueous uranyl acetate at room temperature for 2 h. After dehydration with a graded series of ethanol and embedding in Poly-Bed 812 (Polyscience, Inc.), thin sections were cut, stained doubly with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and then examined under a Hitachi H-800 electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 100 kV.

RNA sequencing

RNA isolation was performed as per manufacturer instructions using the Total RNA Purification Kit with on-column DNA removal (37500 and 25710, Norgen Biotek Corp). RNA sequencing was performed and analyzed at the Washington University Genome Technology Access Center. Global transcriptomic changes in known KEGG terms were elucidated using the R/Bioconductor packages GAGE and Pathview.

Immunohistochemistry

For occludin immunofluorescence, intestinal sections were deparaffinized and incubated overnight at 37°C with a rabbit anti-occludin primary antibody (1:100). Primary antibodies were detected by incubating for 1.5 h at 25°C with an anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa 488 fluorescent dye (Molecular Probes, http://www.invitrogen.com).

Real-time quantitative PCR

Isolated crypts and villi were homogenized in lysis buffer, and RNA was extracted in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (RNAqueous kit; Ambion, Austin TX). The total RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (ND-1000; NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Occludin (OCLD), claudin-3 (CLD3), and zona-occludin 1 (ZO-1) primers were obtained from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Beta-actin was used as the endogenous control (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system was used to obtain relative RNA expression. All reverse-transcription PCR results are normalized to the b-actin endogenous control.

Western blotting

A total of 20 mg of each sample and 15-mL Novex Sharp Pre-stained Protein Standard (57318; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was loaded onto an 8% polyacrylamide gel. Western blotting was performed on a nitrocellulose membrane (IB301001; Invitrogen) after a dry transfer using the iBLOT Gel Transfer Device (IB1001; Invitrogen). The membrane was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin in 1X Phosphate-Buffered Saline,0.1% Tween (PBST) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation in primary antibody at 4°C. The membrane was washed in PBST three times in 10-min increments, incubated for 1 h in the secondary antibody at room temperature, washed in PBST, and developed using GE Healthcare Amersham ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents (6883S; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad) was used to detect and quantify proteins.

Bacterial culture

MLNs were removed aseptically, weighed, and homogenized with a handheld tissue homogenizer in phosphate-buffered saline. Homogenized samples were cultured on tryptic soy sheep blood agar plates and incubated under aerobic and anaerobic conditions for 24 to 48 h. Colonization was expressed as the average number of colony forming units on aerobic and anaerobic plates per milligram of tissue.

Goblet cell associated antigen passages (GAPs)

Small intestine GAPs were enumerated on fixed tissue sections as previously described.14,15 Briefly, tetramethylrhodamine-labeled 10 kD dextran was administered in the jejunum and proximal colon of anesthetized mice. After 1 h, mice were sacrificed and tissues were thoroughly washed with cold PBS before fixing in 10% formalin buffered solution. Tissues were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA); 7-μm sections were prepared, stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Sigma-Aldrich) and imaged using an Axioskop 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY). GAPs were identified as dextran-filled columns measuring approximately 20 μm (height) × 5 μm (diameter) traversing the epithelium and containing a nucleus and were enumerated as GAPs per villus cross section. Fixed small intestine tissue sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (Sigma-Aldrich) in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions, and images were acquired on the Axioskop 2.

Statistical analysis

All values are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test to compare the two experimental groups. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Analysis of variance analyses were used for comparisons of three or more groups. Shapiro-Wilk’s W test was used to confirm normality of the data.

Results

Transcellular permeability

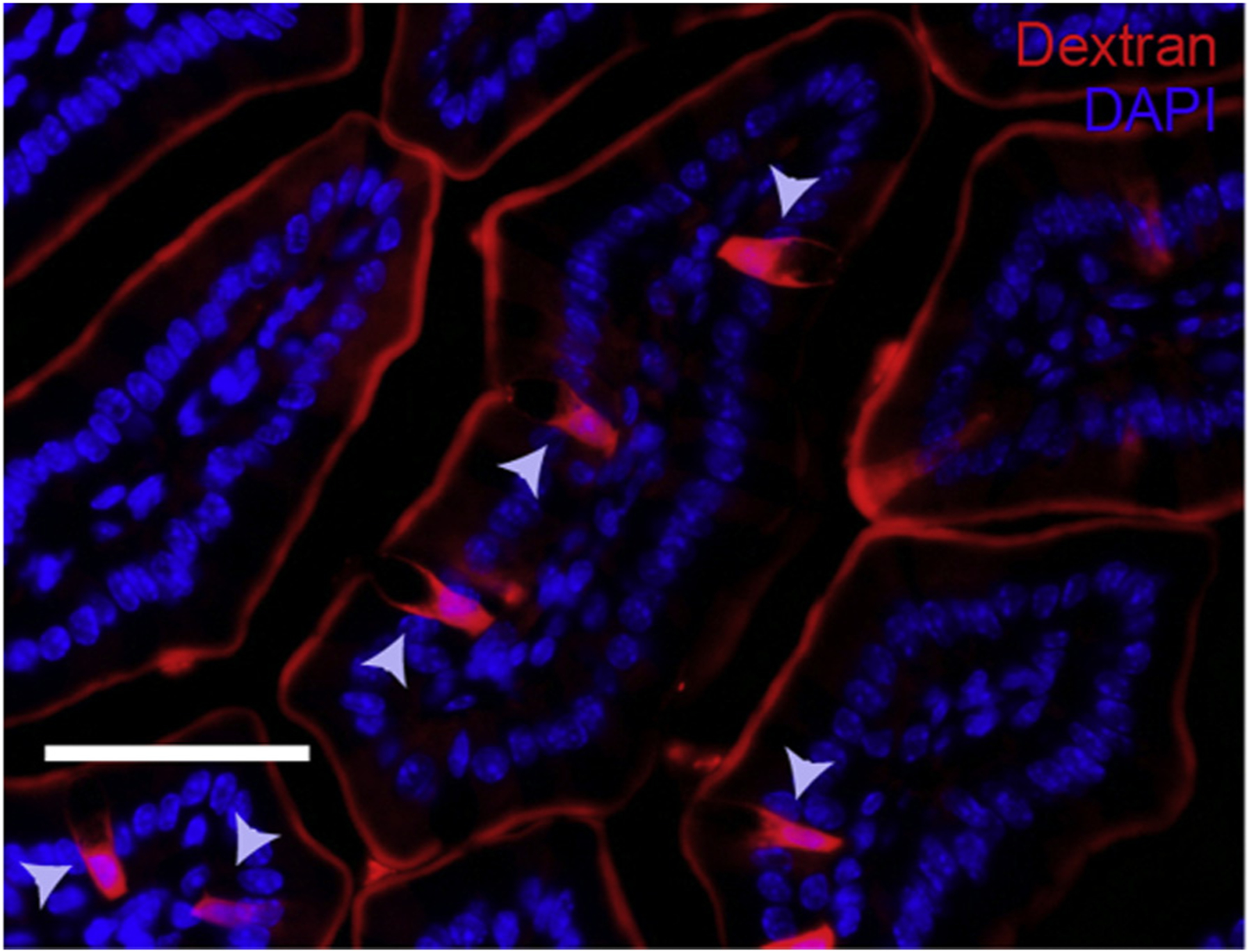

GAPs represent a steady-state pathway that delivers luminal antigens to lamina propria dendritic cells for presentation. GAPs were therefore used as a surrogate for transcellular permeability through the intestinal epithelial cell. The number of GAPs per villi was not statistically different between the two groups (4.5 versus 5.0, P > 0.05, n = 5 per group) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 –

Fluorescent images of SI villus cross section of C57BL/six mice given luminal 10 kD dextran (red) and DAPI (blue), 1h after receiving luminal PBS; the gray arrow depicts GAP.

Paracellular permeability

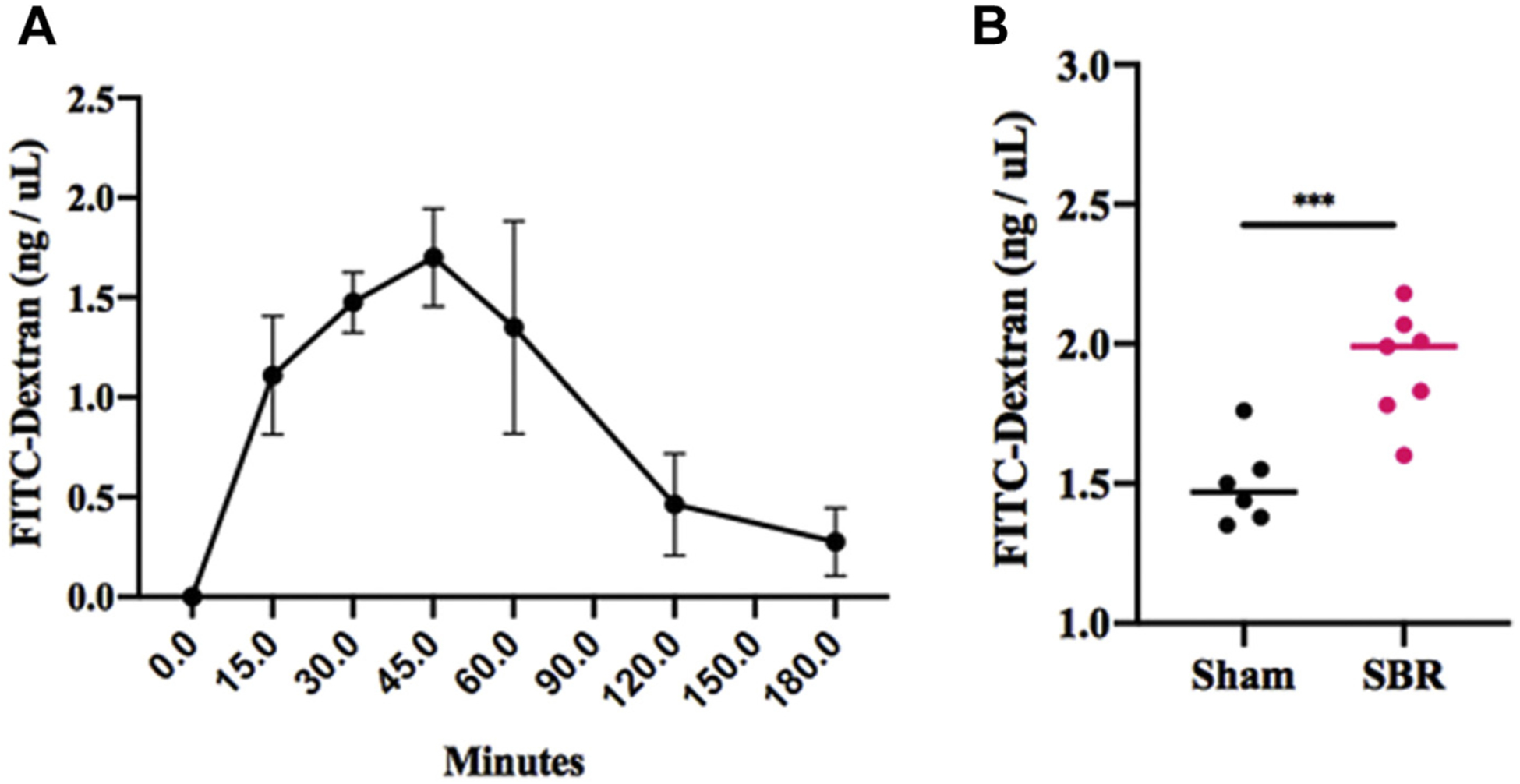

FITC-dextran is used as a marker of paracellular transport and mucosal barrier dysfunction. Oral gavage of FITC-dextran showed no significant difference in serum uptake between sham and SBR after 45 min (1.51 ± 0.54 ng/μL versus 1.83 ± 0.64 ng/μL, P = 0.32, n = 4 per group). Intestinal isolation with clips and subsequent intraluminal FITC-dextran was then performed to control for the different intestinal lengths between sham and SBR groups. FITC-dextran uptake was measured at 30, 45, and 60 min after injection and confirmed maximum uptake into the serum occurred after 45 min (Fig. 2A). We then measured fluorescent uptake in mice after SBR and sham operations. FITC-dextran uptake into the serum after massive SBR was significantly increased compared with sham mice (2.13 ± 0.39 ng/μL versus 1.62 ± 0.23 ng/μL, P < 0.001, n = 8 per group) (Fig. 2B). These findings suggest that that there were significant alterations in permeability at the paracellular level.

Fig. 2 –

(A) Serum uptake after intraluminal injection of 4kD FITC-dextran and serial measurements over time. (B) Uptake of FITC-D 45 min after intraluminal injection in mice at 10 wk after either sham operation or 50% proximal SBR. n = 6–7 per group, *** denotes P < 0.001.

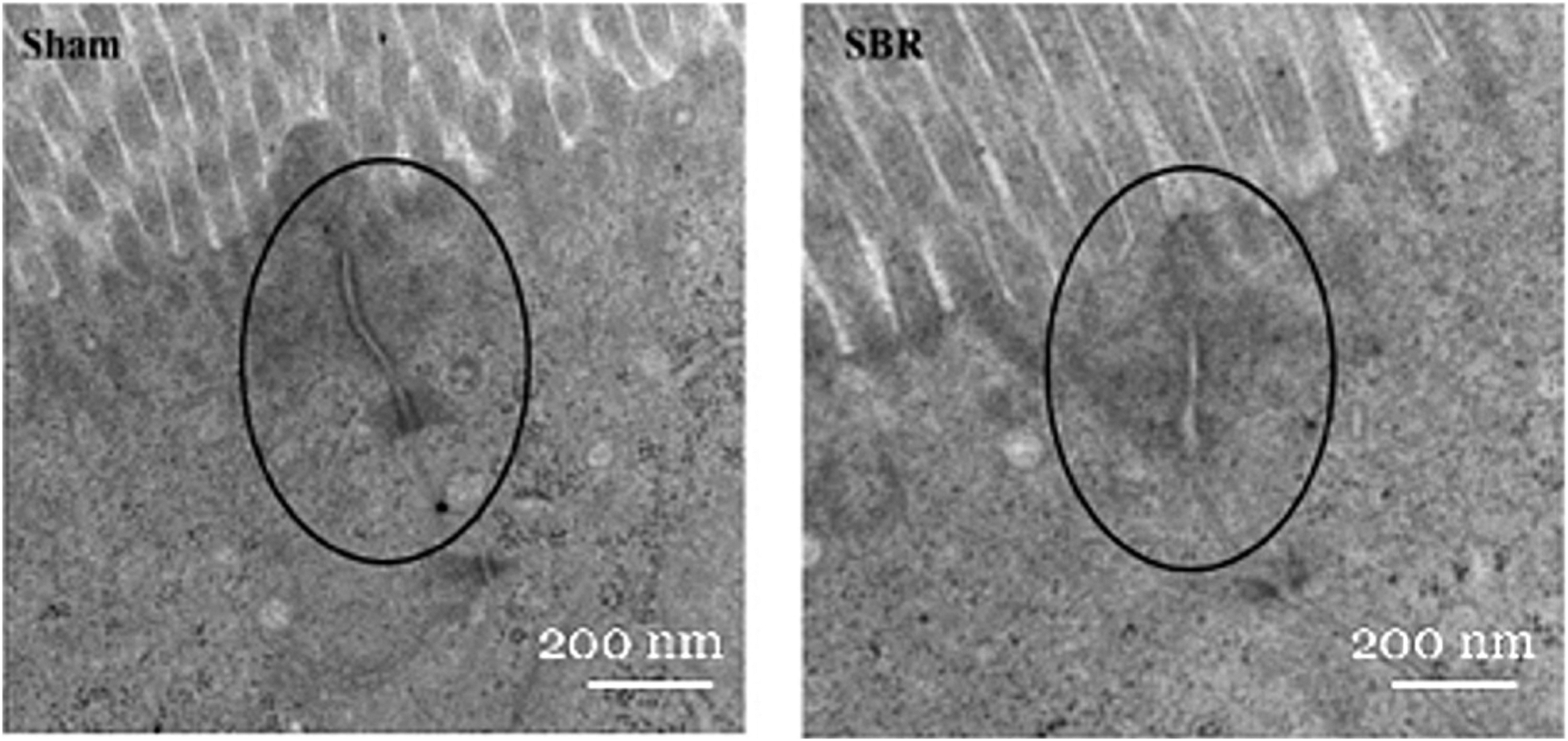

Electron microscopy

We then sought to examine the mainstay of paracellular permeability, the TJ complex. Electron microscopy (EM) imaging demonstrated that mice subjected to SBR had obscured TJ complexes along the apical epithelium with irregular arrangements (Fig. 3A). Sham-operated mice demonstrated intact TJ structures with no apparent blunting (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3 –

EM of TJ complexes (black circles) in sham (left) and SBR (right). Overall magnification: 8000×; Scale bars: 200 nm.

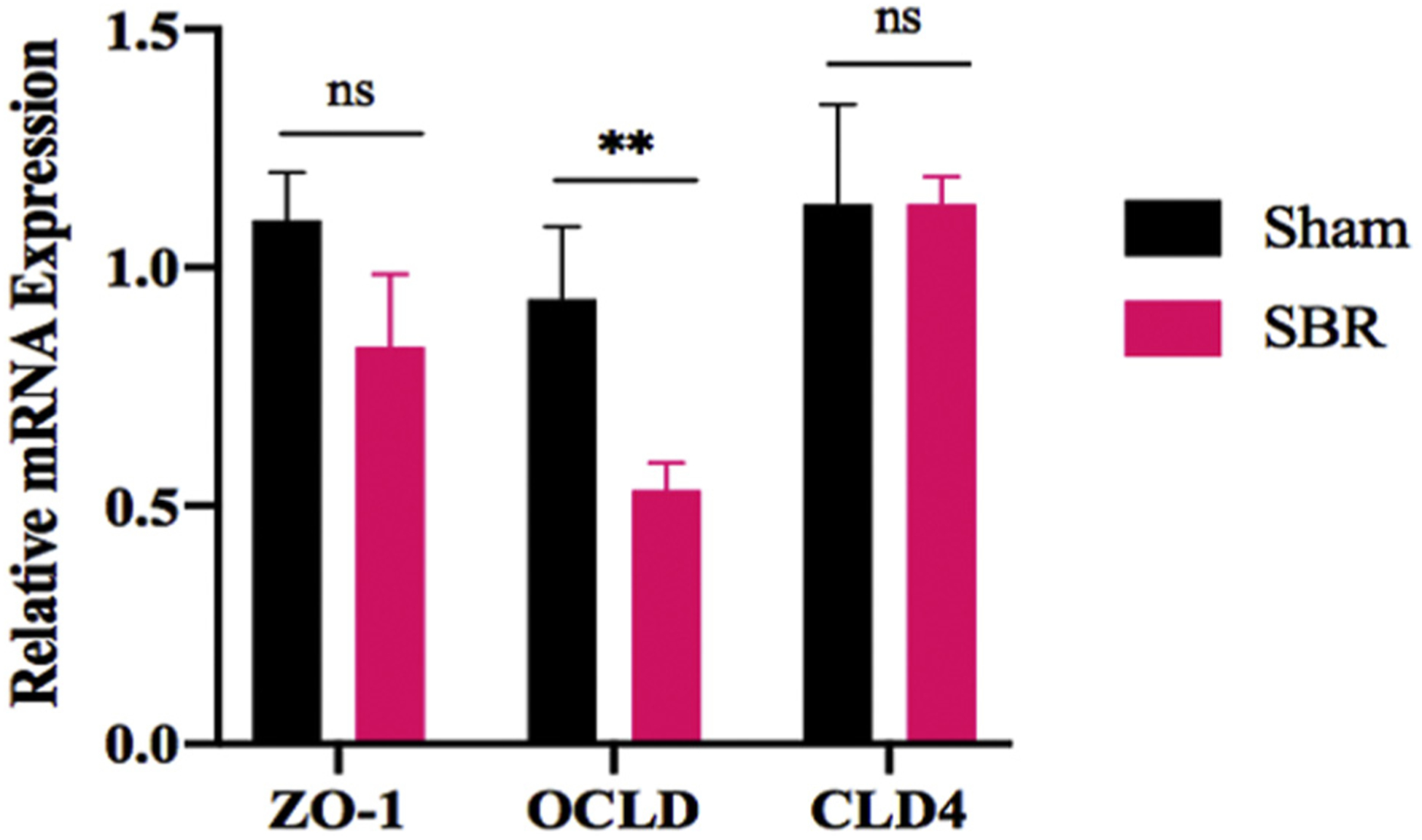

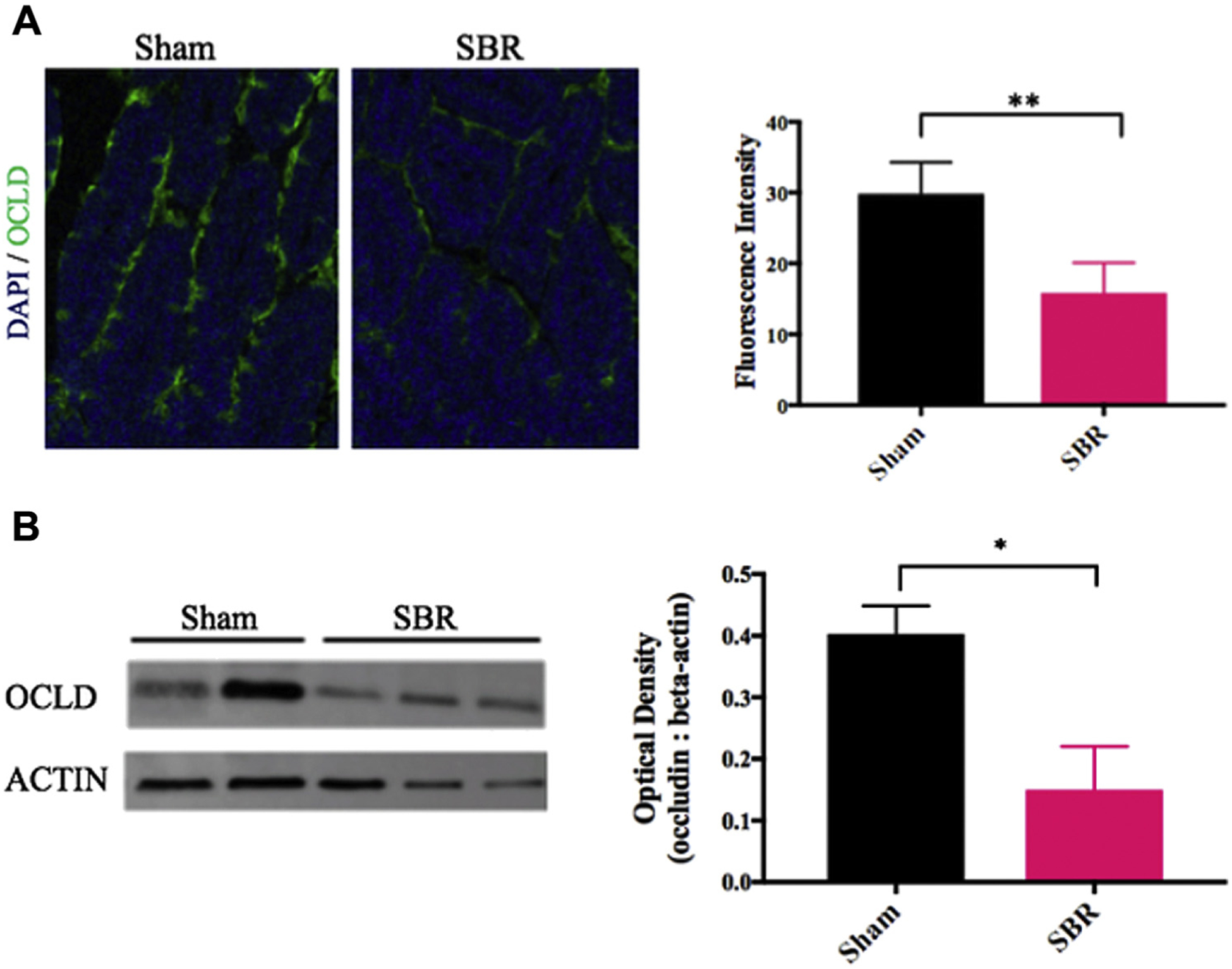

Tight junction expression

Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed a 21% decrease in the integral TJ protein OCLD after SBR (P < 0.05). In addition, CLDN 3 and 4 were at least 20% decreased in mature SBR enterocytes compared with sham. To further investigate these findings, we performed quantitative PCR for selected integral TJ proteins and transcripts, including OCLD, ZO-1, and CLDN 3, which demonstrated a decrease in expression of OCLD (Fig. 4). Representative immunohistochemistry images of OCLD confirmed qualitative changes in these proteins consistent with our scRNA-seq analysis (Fig. 5A). Quantification of this immunostaining panel using immunofluorescence demonstrated a significant decrease in OCLD (1.4 average log2-fold AU, P < 0.001) in SBR relative to sham. Confirmatory western blotting and quantification of OCLD showed a 1.86-fold decrease in SBR compared with sham (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4 –

Relative mRNA expression of TJ integral proteins ZO-1, OCLD, and CLD3 in the ileum of mice at 10 wk after either sham operation or 50% proximal SBR. n = 7 per group, ** denotes P < 0.01.

Fig. 5 –

(A) Immunohistochemistry staining of OCLD in intestinal villi in mice at 10 wk after either sham operation or 50% proximal SBR. Blue: dapi, green: occludin. Scale bars = 150 μm. Quantification on the right. ** indicates P < 0.01.(B) Western blot of OCLD protein expression in mice at 10 wk after either sham operation or 50% proximal SBR. Optical density measurement on the right. * indicates P < 0.05.

Intestinal-specific TLR-4 KO

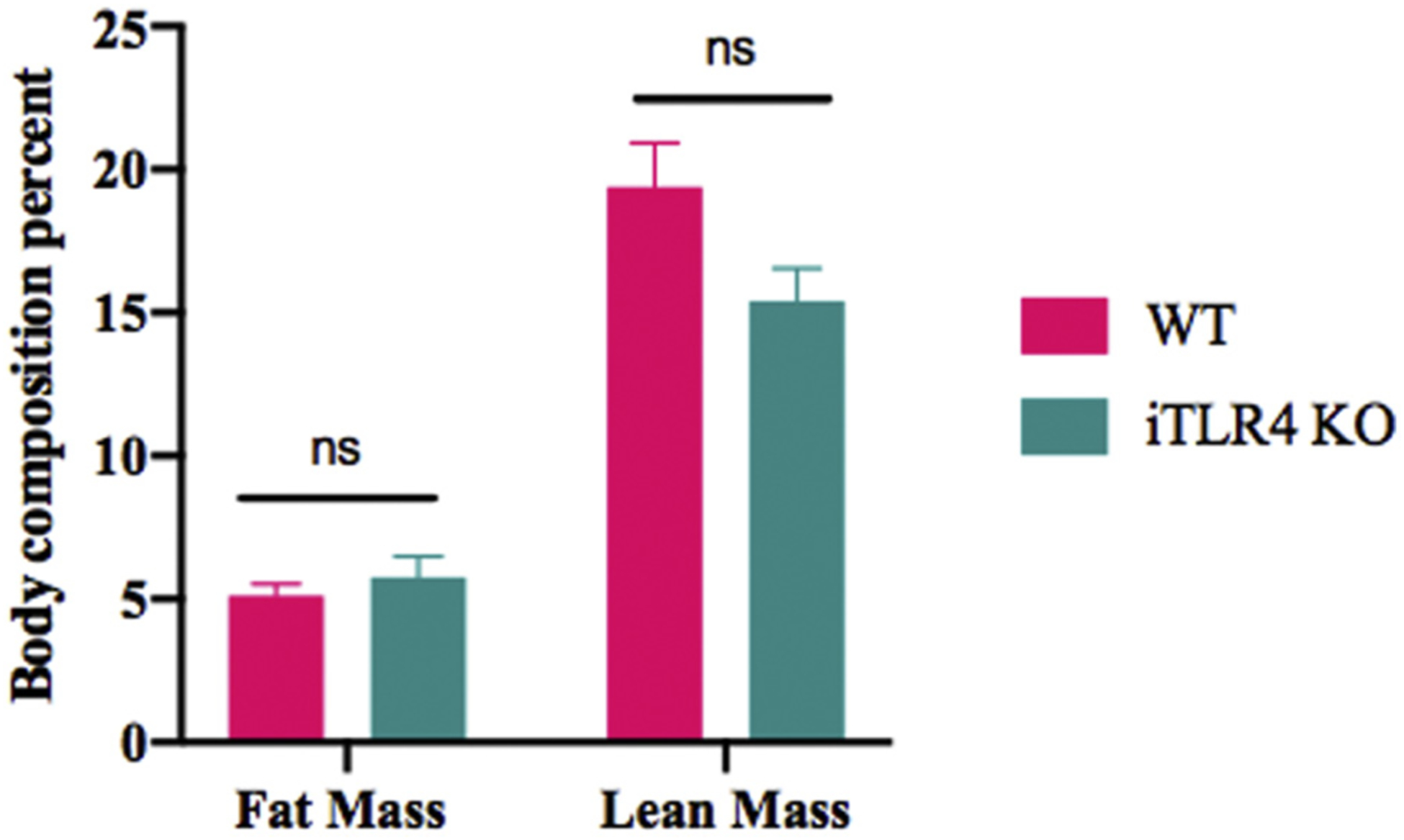

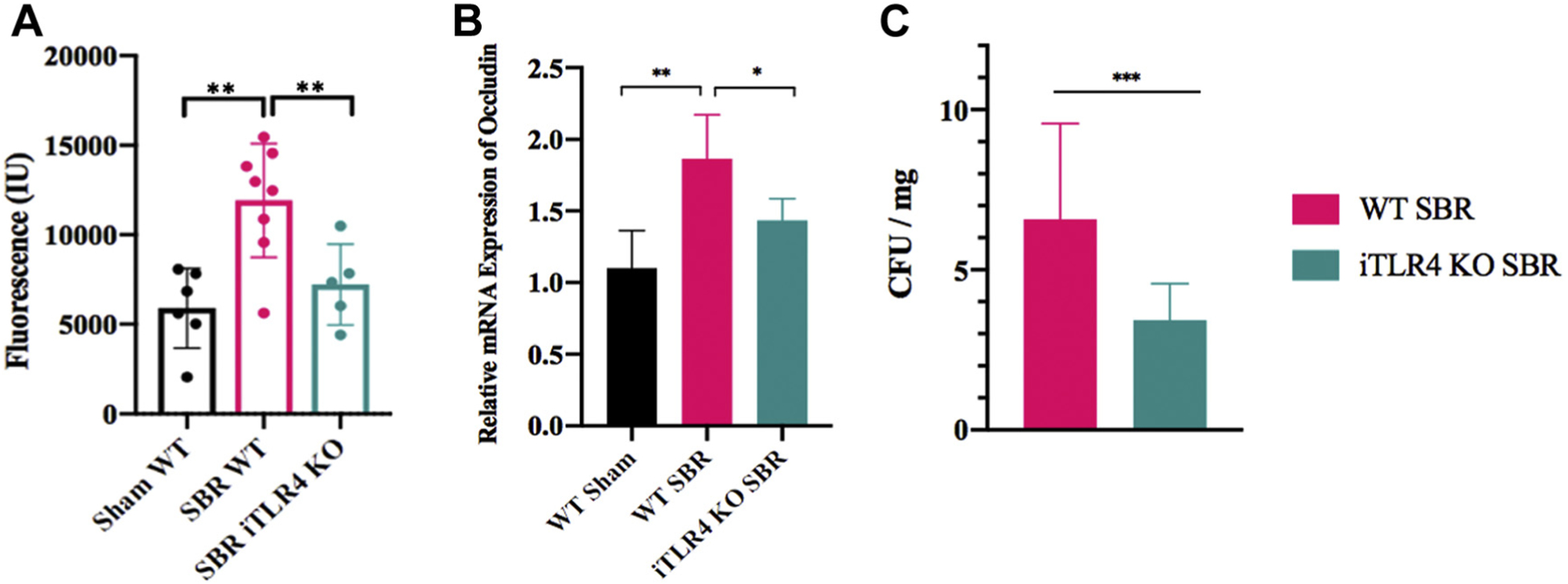

First, we confirmed that TLR-4 was indeed knocked out in the intestinal epithelium (Fig. 6). Then we reviewed baseline characteristics of intestinal-specific TLR4 knockout (iTLR4 KO) mice compared with their wild type (WT) control. There was no significant difference in preoperative weight or mean distribution of lean: fat body mass composition (Fig. 7). FITC-dextran uptake was decreased in the iTLR4 KO group compared with WT control SBRs (analysis of variance comparison: WT sham 5902 ± 910.5 ng/μL, WT SBR 11921 ± 1124 ng/μL, iTLR4 KO SBR 7220 ± 1010 ng/μL, P = 0.0017, n = 6–8 per group)(Fig. 8A). On EM, TJ complexes appeared intact and less distorted. RNA expression of OCLD was increased in iTLR4 KO SBR mice compared with WT controls, whereas there was no statistical difference in expression of ZO-1 or CLD3 between groups (Fig. 8B). In addition, bacterial culture of MLN in iTLR4 KO mice had significantly decreased colony forming units per milligram of tissue (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 6 –

PCR confirmation of the intestinal-specific TLR4 KO. *** indicates P < 0.001; n = 8–10 per group.

Fig. 7 –

(A) Baseline characteristics of villin cre TLR4 KO (iTLR4) mice compared with WT controls. (B) Weight gain as percent of original weight over 10 wk after SBR. n = 7–9 per group, ns denotes not significant.

Fig. 8 –

(A) Serum FITC-dextran uptake in iTLR4KO SBR mice compared with WT control mice at 10 wk after either sham operation or 50% proximal SBR. n = 5–8 per group, (B) Relative mRNA expression of occludin in iTLR4 KO mice compared with WT control mice after SBR, n = 5–7 per group, (C) Mesenteric lymph node bacterial quantification is decreased in iTLR KO mice compared with WT control mice after SBR, n = 7 per group; ** denotes P < 0.01, * denotes P < 0.05.

Discussion

The integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier is crucial to protect the body against stress stimuli related to inflammation and infection. It is known that bacterial translocation is increased after SBR and that overexpression of TLR4 results in increased intestinal permeability and is associated with increased translocation.11,16 Global knockout of TLR4 prevents many of the adverse sequelae seen after SBR thought to be related to increased translocation including hepatic steatosis.12 We therefore wished to understand at what level intestinal permeability may be altered after SBR and the role of epithelial-specific TLR4 expression on barrier function.

Our results demonstrated increased paracellular permeability after massive intestinal resection. Initially, after oral gavage of FITC-dextran, there was no significant difference between the two groups. However, key to our methodology was isolating the same length of bowel in the sham and SBR groups as the resected groups inherently have less overall intestinal length for absorption. This technique revealed a significant increase in FITC-dextran uptake in SBR mice compared with sham.

We then identified the TJ complex as the likely source of impaired barrier function based on the grossly distorted and blunted complexes on EM. The TJ complex is composed of numerous integral proteins including OCLD, CLDN, and ZO-1. Single-cell sequencing as well as confirmatory immunostaining, PCR, and western blot analysis revealed a decrease in expression of OCLD after SBR. Interestingly, in the iTLR4 KO SBR group, these alterations in permeability were not seen and there was preservation of the TJ complexes on EM with increased OCLD expression.

Our results suggest that the increased permeability after SBR is mediated by TLR4. Our laboratory has previously shown a significant increase in intestinal TLR4 expression at day 7 after SBR.12 Consistent with these findings, increased epithelial TLR4 signaling is associated with an impaired epithelial barrier.17,18 In transgenic mice that overexpress TLR4 in the intestinal epithelium, there is increased density of mucosa-associated bacteria and bacterial translocation.19 Much of the research on TLR4 connection to barrier function is centered on its role in the inflammatory response. LPS-induced inflammation and mucosal damage are mediated by activation of the TLR4/FAK/MyD88 signal transduction axis.20 Although not to the same degree as conditions such as necrotizing colitis or inflammatory bowel disease, massive intestinal resection similarly induces an initial proinflammatory milieu within the intestine. This has been demonstrated across species in rat and zebrafish models of SGS, as well as human studies, which show that acute phase response signaling and proinflammatory cytokines are significantly increased, which play a role in the increased permeability of the intestinal barrier.21–26 Along these lines, there is a marked increase in LPS-producing bacteria in the intestine of humans with IFALD related to massive intestinal resection.27

The involvement of TLR4 may also explain why OCLD as opposed to other TJ integral proteins was specifically affected in our model. OCLD is highly expressed at cell-cell contact sites and is thought to be important in the assembly and stability of the TJ.28 Wang et al. found that upregulation of fibroblast growth factor-inducible molecule 14 augments LPS-induced inflammation and downregulates OCLD expression in small intestine epithelial cells via activation of TLR4-associated pathways.29 Similarly, overexpression models of intestinal TLR4 have shown reduced OCLD gene expression on western blot analysis in the small intestine epithelial cells.19 Therefore, it is not surprising that our iTLR KO mice demonstrated increased OCLD mRNA expression after SBR.

The role of intraluminal and mucosal bacteria should also be considered as significant dysbiosis is known to occur after massive SBR.30–32 LPS is a component of the outer walls of gram-negative bacteria and is known to alter TJ protein assembly. Human patients with SGS have elevated levels of LPS-binding protein, and intestinal bacterial overgrowth seen in SGS is also associated with high intraluminal levels of LPS.33,34 Therefore, the increased activation of TLR4 resulting in increased permeability may be a consequence of the dysbiotic environment after SBR.

It was specifically relevant to also quantify changes in both body mass and weight gain as our laboratory has previously found that after intestinal resection, there is an inappropriate replenishment of fat stores over lean mass.35 This has been further validated clinically in both adult and pediatric patients where SBS is associated with increased percent body fat and reduced fat-free mass.36 Metabolic conditions have also been associated with TLR4 and a defective intestinal TJ barrier. Using a different mouse line, Hackam et al. demonstrated that specifically knocking out TLR4 in the intestine resulted in a metabolic syndrome.18 Hyperglycemia and liver disease seen in metabolic syndrome are known to drive intestinal barrier permeability through transcriptional reprogramming of intestinal epithelial cells and alterations of TJs.37,38 We did not identify differences in metabolic parameters measured by body composition between iTLR4 KO and WT control mice. This could be due to the effect of intestinal resection and less remaining bowel surface area and/or due to many known changes in gut hormones and peptides associated with massive SBR.

Finally, intestinal anatomic considerations after SBR should also be considered regarding TLR4 and intestinal permeability. It is known that there is a lower expression of TJ complexes in the jejunum than in the ileum.21,39 Conversely, there is a higher abundance of TLR4 in the proximal jejunal Peyer’s patches than in the distal ileum.40 Our laboratory has recently identified a “proximalization” effect after SBR whereby the distal intestine takes on the transcriptional signature of the more proximal small intestine.41 Therefore, perhaps the increase in permeability is secondary to cell reprogramming resulting in increased TLR4 and a decrease in TJ proteins in the distal ileum, which is supported by our single-cell sequencing results.

There are some limitations to note in this study. First, the starting microbiome of both groups was not quantified. In prior studies, we have analyzed the starting microbiome and found no significant differences among the various mice cohorts.42 Furthermore, all mice in the TLR4 cohorts were bred and weaned in the same facility and shams and SBRs were cohoused therefore minimizing any possible differences in starting microbiomes. Another drawback in our study is that we did not specifically measure portal vein cytokine levels. This information would be revealing to our overall hypothesis that the disturbance in the gut barrier travels along the enterohepatic axis to promote inflammation and liver injury. Finally, it is known that TLR4 expression increases along the length of the bowel and is greatest in the distal intestine and colon which we did not resect. The resulting changes in the TLR4 in the colon may also be potentially playing a role in the subsequent changes that we observed and requires further investigation.

Conclusion

Permeability after intestinal resection is increased at the paracellular level. Intestine TLR4 signaling is required for the alterations in permeability and development of resection-associated liver injury. Strategies to reduce TLR4-mediated inflammation after massive resection may offer novel therapeutic approaches to enhancing barrier function and reducing intestine-associated liver disease.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jun Guo from the Warner laboratory for his assistance in planning the methodology for paracellular permeability, Karen Green at the electron microscopy core for her assistance in providing fixative and embedding the specimens, Keely McDonald from the Newberry laboratory for providing the protocol and quantification of goblet cell associated antigen passages, and the Washington University developmental biology core and digestive diseases research core for the processing and staining of histological samples.

Funding sources

C.M.C. received funding from Children’s Hope Foundation-Marion and Van Black Research Scholar. E.J.O, A.E.S., and A.M.S. received funding from NIH 5T32DK077653. K.M.S received funding from NIH 5T32HD043010. M.E.T received funding from NIH T32DK007120. R.D.N. received funding from NIH 5R01AI136515. B.W.W. received funding from NIH 5R01DK119147, Children’s Surgical Sciences Research Institute of the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation, Marion, and Van Black Research Scholarship.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept in this article. This work was presented at the Academic Surgical Congress 2020 in Orlando, Florida.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duggan CP, Jaksic T. Pediatric intestinal failure. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauriti G, Zani A, Aufieri R, et al. Incidence, prevention, and treatment of parenteral nutrition-associated cholestasis and intestinal failure-associated liver disease in infants and children: a systematic review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38:70–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sears CL. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions V. assault of the tight junction by enteric pathogens. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G1129–G1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saffouri GB, Shields-Cutler RR, Chen J, et al. Small intestinal microbial dysbiosis underlies symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alaish SM, Smith AD, Timmons J, et al. Gut microbiota, tight junction protein expression, intestinal resistance, bacterial translocation and mortality following cholestasis depend on the genetic background of the host. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:292–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik BA, Xie YY, Wine E. Huynh HQ Diagnosis and pharmacological management of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in children with intestinal failure. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:41–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson JM, Van Itallie CM. Physiology and function of the tight junction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groschwitz KR. Hogan SP Intestinal barrier function: molecular regulation and disease pathogenesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:3–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asensio AB, Garcia-Urkia N, Aldazabal P, et al. [Incidence of bacterial translocation in four different models of experimental short bowel syndrome]. Cir Pediatr. 2003;16:20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eizaguirre I, Aldazabal P, Garcia N, et al. [Bacterial translocation associated with short bowel: role of ileocecal valve and cecum]. Cir Pediatr. 2001;14:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien DP, Nelson LA, Kemp CJ, et al. Intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation are uncoupled after small bowel resection. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:390–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barron LK, Bao JW, Aladegbami BG, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 is critical for the development of resection-associated hepatic steatosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52:1014–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helmrath MA, VanderKolk WE, Can G, Erwin CR. Warner BW Intestinal adaptation following massive small bowel resection in the mouse. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDole JR, Wheeler LW, McDonald KG, et al. Goblet cells deliver luminal antigen to CD103+ dendritic cells in the small intestine. Nature. 2012;483:345–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knoop KA, McDonald KG, McCrate S, McDole JR. Newberry RD Microbial sensing by goblet cells controls immune surveillance of luminal antigens in the colon. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:198–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Wang C, Nie J, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 increases intestinal permeability through up-regulation of membrane PKC activity in alcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcohol. 2013;47:459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukata M, Michelsen KS, Eri R, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 is required for intestinal response to epithelial injury and limiting bacterial translocation in a murine model of acute colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1055–G1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hackam DJ, Good M, Sodhi CP. Mechanisms of gut barrier failure in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis: toll-like receptors throw the switch. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2013;22:76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dheer R, Santaolalla R, Davies JM, et al. Intestinal epithelial toll-like receptor 4 signaling affects epithelial function and colonic microbiota and promotes a risk for transmissible colitis. Infect Immun. 2016;84:798–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo S, Nighot M, Al-Sadi R, et al. Lipopolysaccharide regulation of intestinal tight junction permeability is mediated by TLR4 signal transduction pathway activation of FAK and MyD88. J Immunol. 2015;195:4999–5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee B, Moon KM, Kim CY. Tight junction in the intestinal epithelium: its association with diseases and regulation by phytochemicals. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:2645465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li GZ, Wang ZH, Cui W, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha increases intestinal permeability in mice with fulminant hepatic failure. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5042–5050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruewer M, Utech M, Ivanov AI, et al. Interferon-gamma induces internalization of epithelial tight junction proteins via a macropinocytosis-like process. FASEB J. 2005;19:923–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aprahamian CJ, Chen M, Yang Y, Lorenz RG. Harmon CM Two-hit rat model of short bowel syndrome and sepsis: independent of total parenteral nutrition, short bowel syndrome is proinflammatory and injurious to the liver. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:992–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schall KA, Thornton ME, Isani M, et al. Short bowel syndrome results in increased gene expression associated with proliferation, inflammation, bile acid synthesis and immune system activation: RNA sequencing a zebrafish SBS model. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ralls MW, Demehri FR, Feng Y, Woods Ignatoski KM. Teitelbaum DH Enteral nutrient deprivation in patients leads to a loss of intestinal epithelial barrier function. Surgery. 2015;157:732–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korpela K, Mutanen A, Salonen A, et al. Intestinal microbiota signatures associated with histological liver steatosis in pediatric-onset intestinal failure. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2017;41:238–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saitou M, Furuse M, Sasaki H, et al. Complex phenotype of mice lacking occludin, a component of tight junction strands. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:4131–4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qi X, Qin L, Du R, et al. Lipopolysaccharide upregulated intestinal epithelial cell expression of Fn14 and activation of Fn14 signaling amplify intestinal TLR4-mediated inflammation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engelstad HJ, Barron L, Moen J, et al. Remnant small bowel length in pediatric short bowel syndrome and the correlation with intestinal dysbiosis and linear growth. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227:439–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engstrand Lilja H, Wefer H, Nystrom N, Finkel Y, Engstrand L. Intestinal dysbiosis in children with short bowel syndrome is associated with impaired outcome. Microbiome. 2015;3:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeichner SL, Mongodin EF, Hittle L, Huang SH, Torres C. The bacterial communities of the small intestine and stool in children with short bowel syndrome. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0215351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cinkajzlova A, Lacinova Z, Klouckova J, et al. Increased intestinal permeability in patients with short bowel syndrome is not affected by parenteral nutrition. Physiol Res. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouhnik Y, Alain S, Attar A, et al. Bacterial populations contaminating the upper gut in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1327–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tantemsapya N, Meinzner-Derr J, Erwin CR. Warner BW Body composition and metabolic changes associated with massive intestinal resection in mice. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiplunker AJ, Chen L, Levin MS, et al. Increased adiposity and reduced lean body mass in patients with short bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thaiss CA, Levy M, Grosheva I, et al. Hyperglycemia drives intestinal barrier dysfunction and risk for enteric infection. Science. 2018;359:1376–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vajro P, Paolella G. Fasano A Microbiota and gut-liver axis: their influences on obesity and obesity-related liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collins FL, Rios-Arce ND, Atkinson S, et al. Temporal and regional intestinal changes in permeability, tight junction, and cytokine gene expression following ovariectomy-induced estrogen deficiency. Physiol Rep. 2017;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gourbeyre P, Berri M, Lippi Y, et al. Pattern recognition receptors in the gut: analysis of their expression along the intestinal tract and the crypt/villus axis. Physiol Rep. 2015;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seiler KM, Waye SE, Kong W, et al. Single-cell analysis reveals regional reprogramming during adaptation to massive small bowel resection in mice. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sommovilla J, Zhou Y, Sun RC, et al. Small bowel resection induces long-term changes in the enteric microbiota of mice. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:56–64 [discussion 64]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]